Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Motivation

- The attributes of datasets are separated into explicit identifier attributes, quasi-identifier attributes, and sensitive attribute(s).

- All values in every explicit identifier attribute must be removed.

- The re-identifiable quasi-identifier values are suppressed or generalized by their less specific values to be indistinguishable.

- In addition, some privacy preservation models (e.g., l-Diversity and t-Closeness) further consider the characteristics of sensitive values in their privacy preservation constraints.

3. Model and Notation

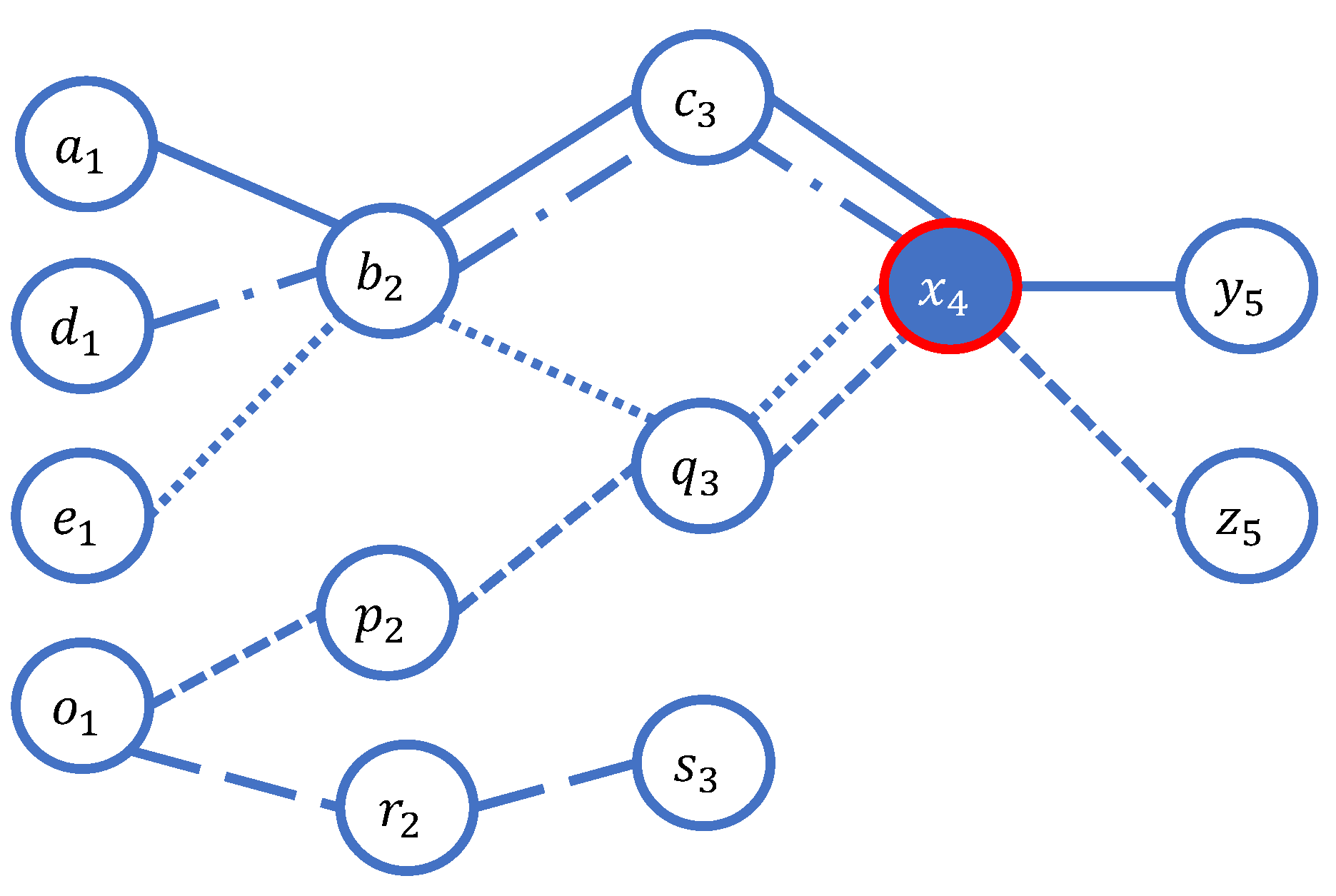

3.1. The Graph of Users’ Visited Sequence Locations

- Let the vertex connects to the vertex .

- Moreover, let the vertex connects to the vertex .

- Therefore, the timestamp of the vertices , . must be according to the property as .

3.2. The Type of Vertices

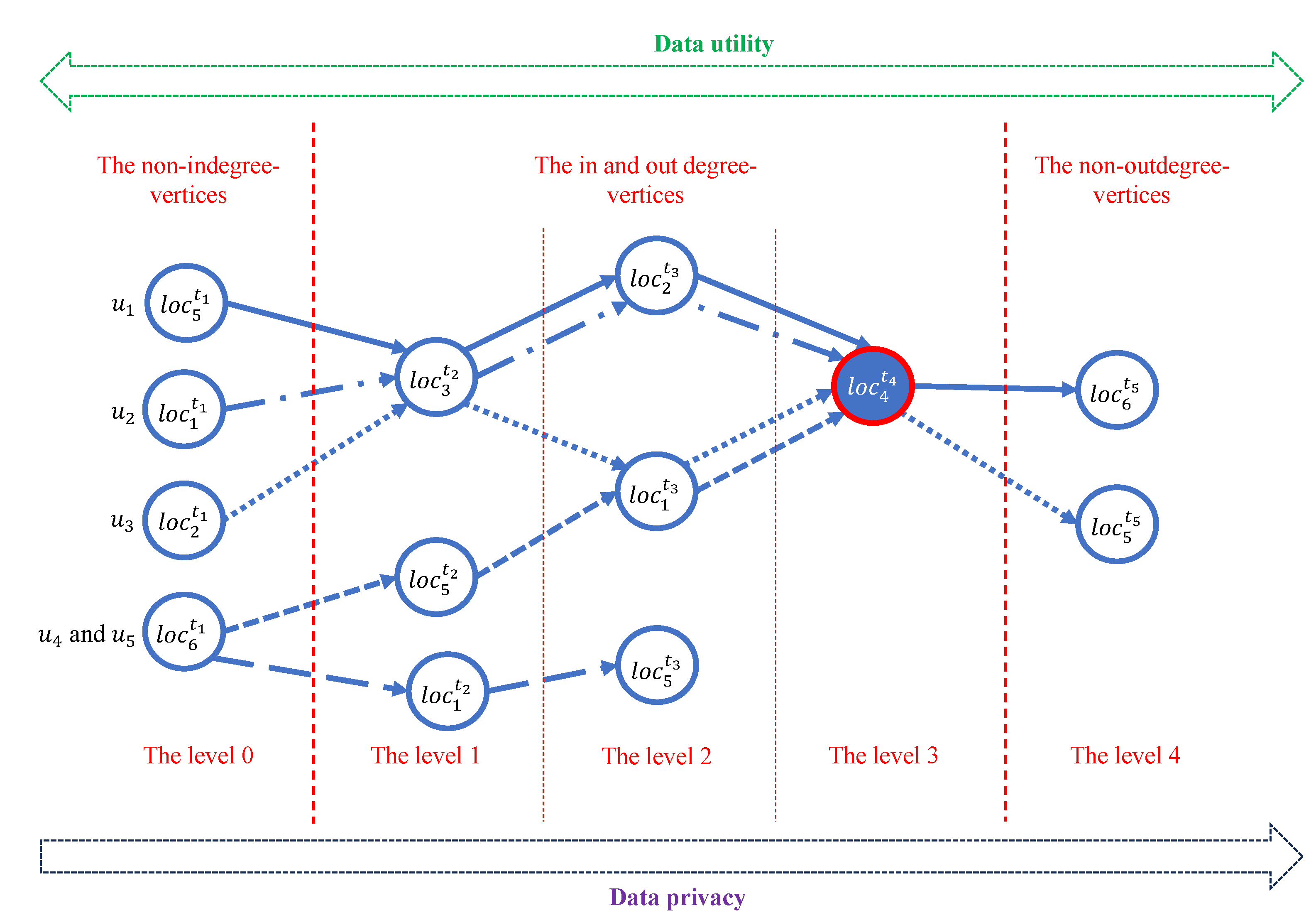

3.3. Data Sliding Windows [56,57,58,59]

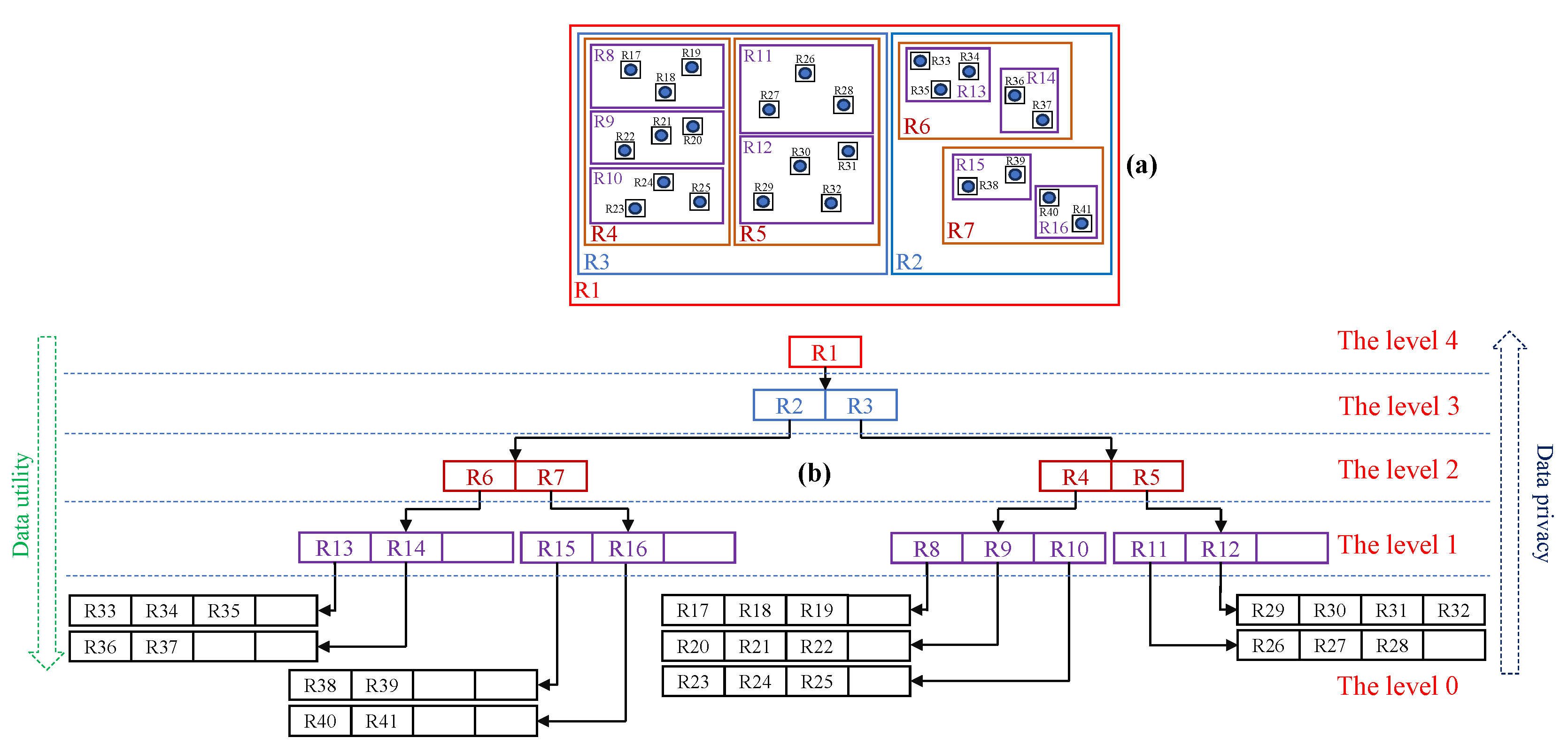

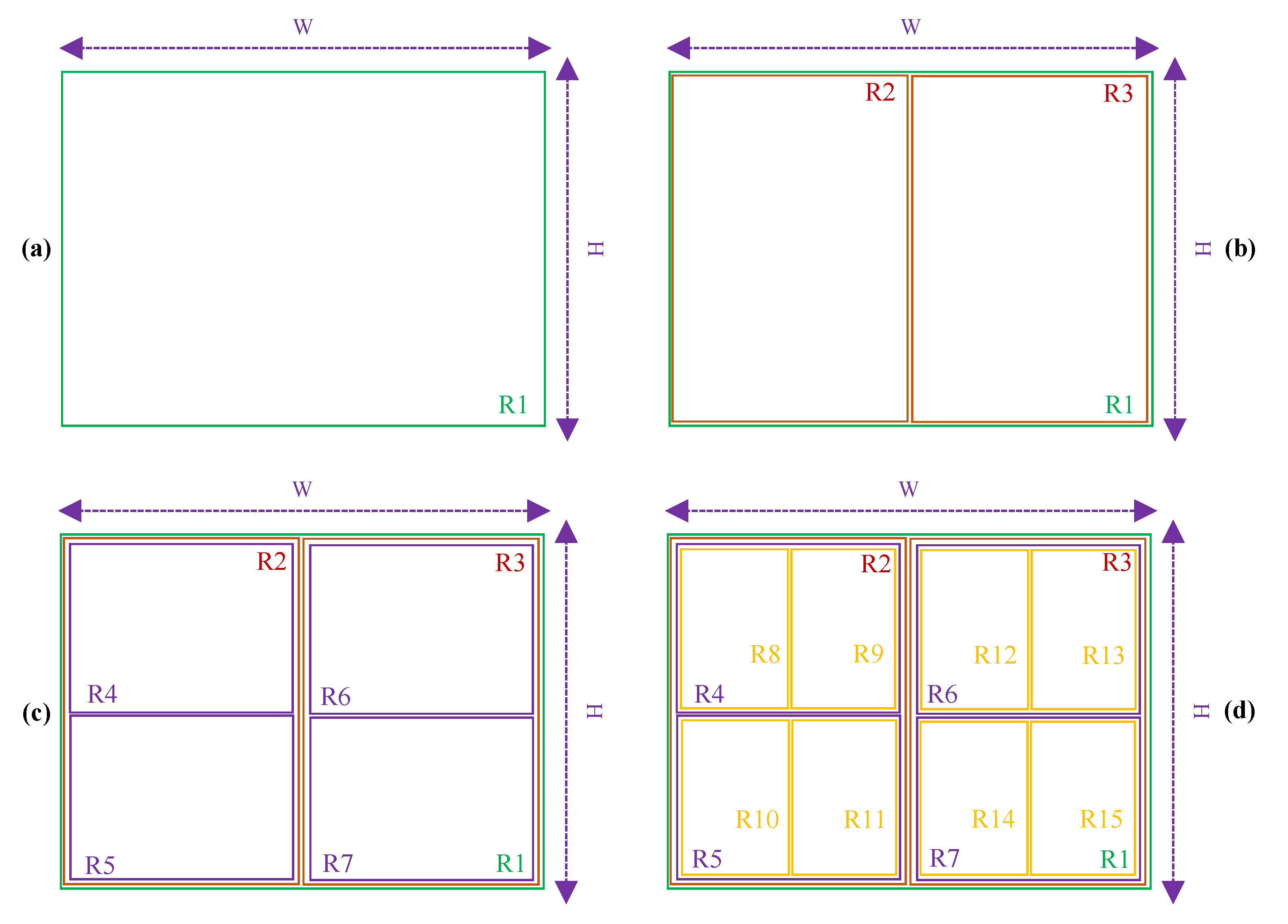

3.4. Location Hierarchy

3.4.1. Dynamic Location Hierarchy

- The bounding rectangle is not covered by others, it is the root of R.

- The child of is every that is only covered by and is not covered by others.

- The label of each vertex in the tree is represented by .

3.4.2. Manual Location Hierarchy

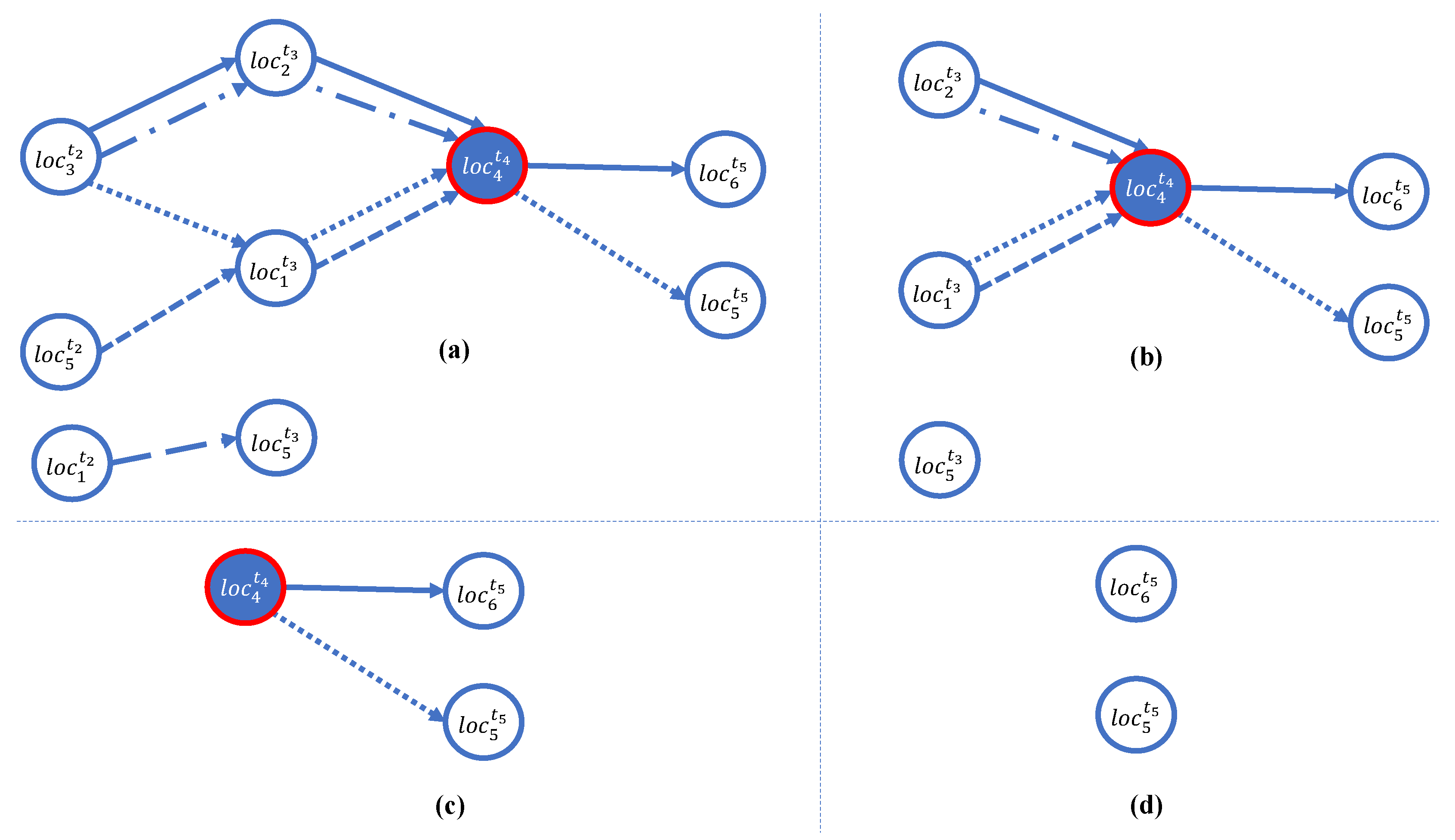

3.5. Data Suppression

- .

- ∪…∩∪…∪=∅ such that is the set of the vertices in level l of , where .

- ∪…∪∪…∪=.

3.6. Data Generalization

3.7. The Proposed Privacy Preservation Model

3.7.1. Problem Statement

3.7.2. The Privacy Preservation Algorithm

|

Algorithm 1:

, , , , , , )-Privacy

|

|

- is the level of vertices that are suppressed.

- n is the number of the paths of .

- n is the number of users’ visited location in .

- is the number of sensitive locations that must be protected in .

- is the number of the paths that are available in of .

- l is the high of .

- are the forest graphs of .

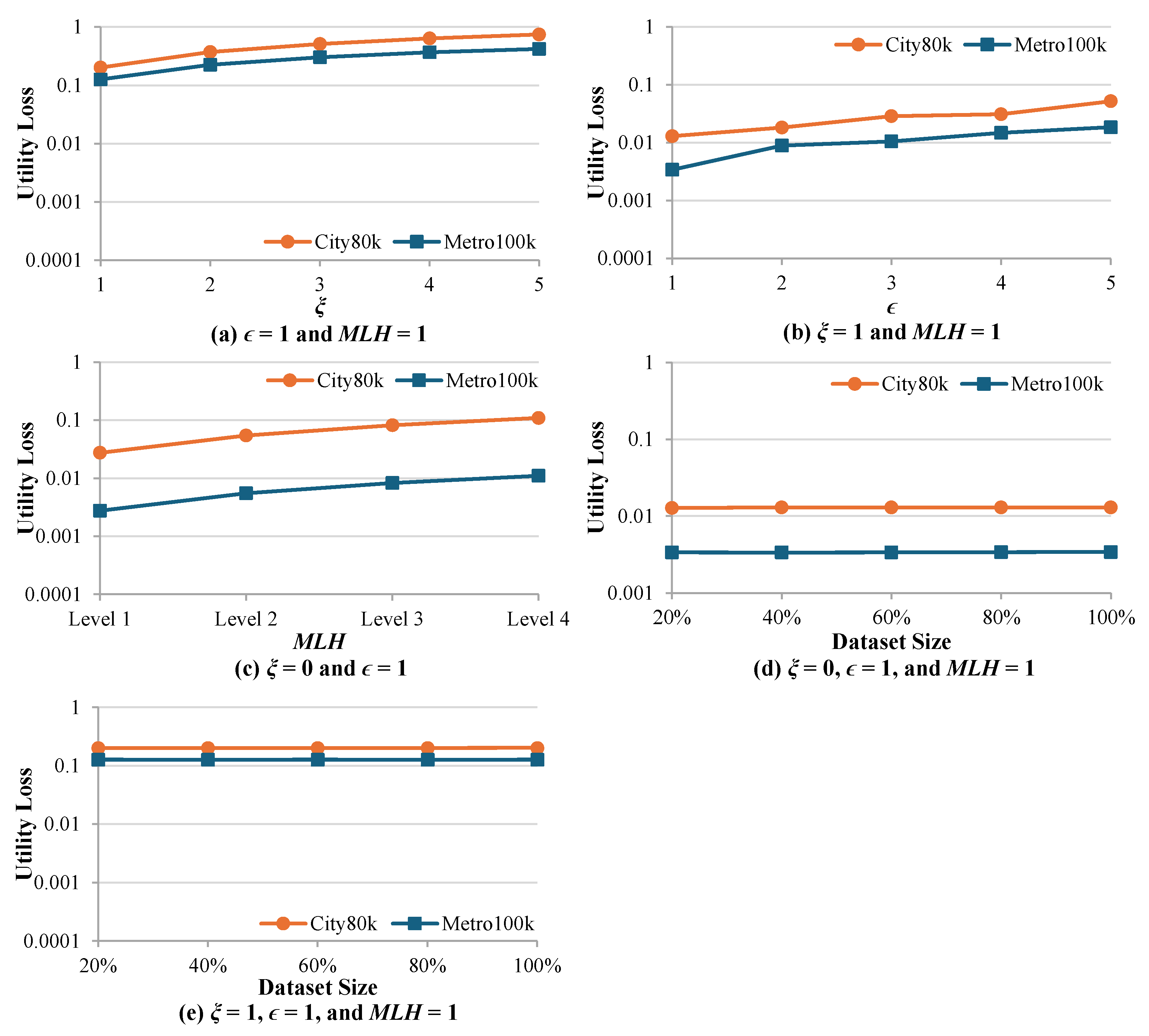

3.7.3. Utility Measurement

- is the number of paths in .

- is the number of vertices in .

- is the number of suppressed vertices in .

- represents the level of generalization of the data of the vertex .

- is the highest of .

- v is the original query result.

- is the result of the related experiment query.

4. Experiment

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Effectiveness

4.1.2. Efficiency

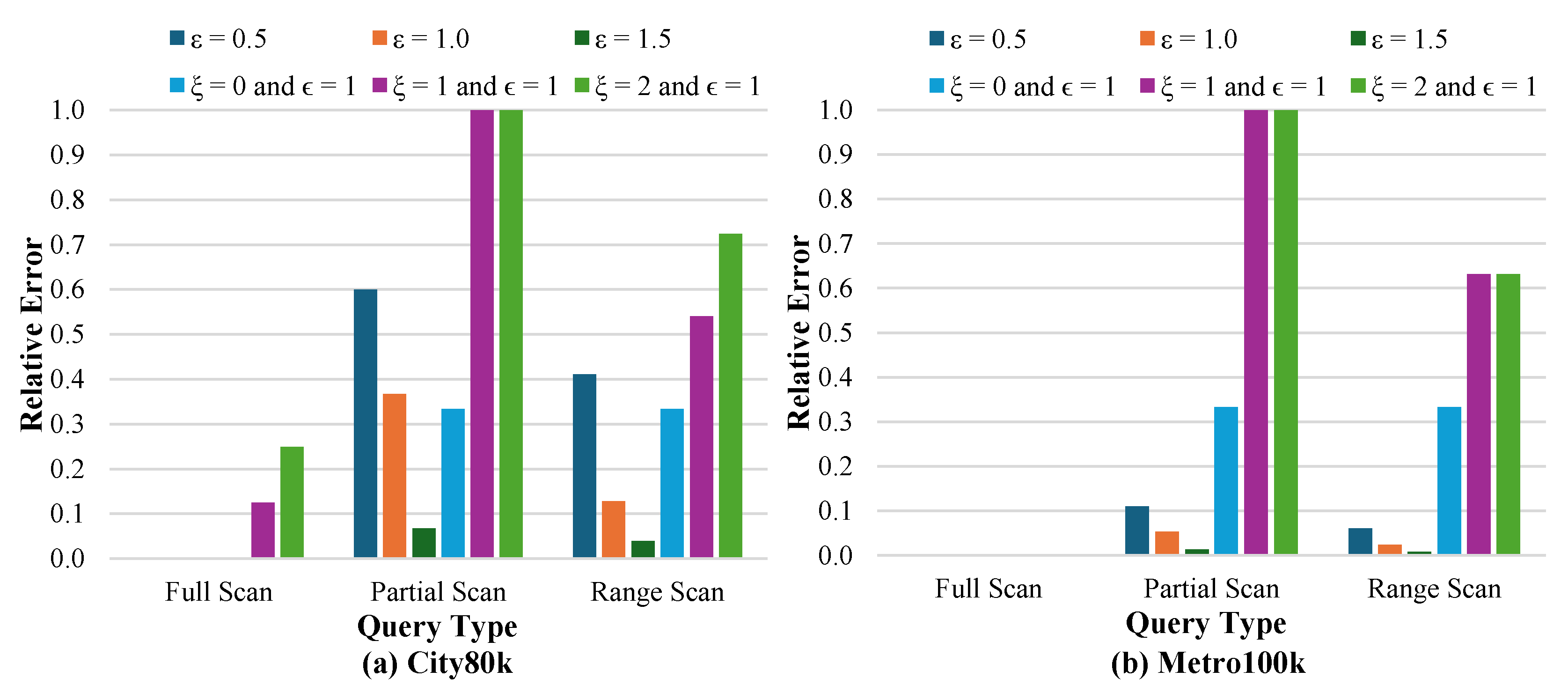

4.2. Relative Error Across Query Types

4.2.1. Full Scan Queries

4.2.2. Partial Scan Queries

4.2.3. Multi-Timestamp Scan Queries

5. Conclusions

6. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cummins, C.; Orr, R.; O’Connor, H.; West, C. Global positioning systems (GPS) and microtechnology sensors in team sports: a systematic review. Sports medicine 2013, 43, 1025–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enge, P.K. The global positioning system: Signals, measurements, and performance. International Journal of Wireless Information Networks 1994, 1, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, M.S.; Weill, L.R.; Andrews, A.P. Global positioning systems, inertial navigation, and integration; John Wiley & Sons, 2007.

- Greenspan, R.L. Global navigation satellite systems. AGARD Lecture, NATO 1996.

- Li, R.; Zheng, S.; Wang, E.; Chen, J.; Feng, S.; Wang, D.; Dai, L. Advances in BeiDou Navigation Satellite System (BDS) and satellite navigation augmentation technologies. Satellite Navigation 2020, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, W.; Guo, S.; Mao, Y.; Yang, Y. Introduction to BeiDou-3 navigation satellite system. Navigation 2019, 66, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noone, R. Location Awareness in the Age of Google Maps; Taylor & Francis, 2024.

- Pramanik, M.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Anam, A.I.; Ali, A.A.; Amin, M.A.; Rahman, A.M. Modeling traffic congestion in developing countries using google maps data. In Proceedings of the Advances in Information and Communication: Proceedings of the 2021 Future of Information and Communication Conference (FICC), Volume 1. Springer, 2021, pp. 513–531.

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, L.; Li, X.; Peng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, P. Progress and trends in the application of Google Earth and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Driscol, J.; Sarigai, S.; Wu, Q.; Chen, H.; Lippitt, C.D. Google Earth Engine and artificial intelligence (AI): a comprehensive review. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herfort, B.; Lautenbach, S.; Porto de Albuquerque, J.; Anderson, J.; Zipf, A. A spatio-temporal analysis investigating completeness and inequalities of global urban building data in OpenStreetMap. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biljecki, F.; Chow, Y.S.; Lee, K. Quality of crowdsourced geospatial building information: A global assessment of OpenStreetMap attributes. Building and Environment 2023, 237, 110295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtusiak, J.; Nia, R.M. Location prediction using GPS trackers: Can machine learning help locate the missing people with dementia? Internet of Things 2021, 13, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, A.; Mazhar, M.K.A.; Smith, M.D.; Lithander, F.E.; Ó Breasail, M.; Henderson, E.J. Wearable and portable GPS solutions for monitoring mobility in dementia: a systematic review. Sensors 2022, 22, 3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.P.; Zaidi, S.; Nascimento, C.D.S.; de Albuquerque, V.H.C.; Chauhan, S.S. Analysis and Design of automatically generating for GPS Based Moving Object Tracking System. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Communication (AISC). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–5.

- McFedries, P.; McFedries, P. Protecting Your Device. Troubleshooting iOS: Solving iPhone and iPad Problems 2017, pp. 91–109.

- Heinrich, A.; Bittner, N.; Hollick, M. AirGuard-protecting android users from stalking attacks by apple find my devices. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, 2022, pp. 26–38.

- Chen, Y.; Huang, Z.; Ai, H.; Guo, X.; Luo, F. The impact of GIS/GPS network information systems on the logistics distribution cost of tobacco enterprises. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2021, 149, 102299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Li, G.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, W.; He, X.; Zhang, M.; Wei, N. Emergency logistics centers site selection by multi-criteria decision-making and GIS. International journal of disaster risk reduction 2023, 96, 103921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, X. A two-stage robust model for express service network design with surging demand. European Journal of Operational Research 2022, 299, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Garg, H.; Li, N. Pythagorean fuzzy interactive Hamacher power aggregation operators for assessment of express service quality with entropy weight. Soft Computing 2021, 25, 973–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.X.; Guo, R.Y.; Zhai, Y.; Feng, J.; Ning, Y. Toward a positive compensation policy for rail transport via mechanism design: The case of China Railway Express. Transport Policy 2024, 146, 322–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondek, N. Are GrubHub and DoorDash the Next Vertical Monopolists? Chicago Policy Review (Online) 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, Y.; Ido, K.; Kawai, S.; Kuroda, S. Who took gig jobs during the COVID-19 recession? Evidence from Uber Eats in Japan. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 2022, 13, 100543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, C.; et al. A case study on Zomato–The online Foodking of India. Journal of Management Research and Analysis 2020, 7, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Crescimanno, M.; Vrontis, D.; Siggia, D. Contribution to the sustainability challenges of the food-delivery sector: finding from the Deliveroo Italy case study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourrahmani, E.; Jaller, M.; Fitch-Polse, D.T. Modeling the online food delivery pricing and waiting time: Evidence from Davis, Sacramento, and San Francisco. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 2023, 21, 100891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.F.; Tan, C.L.; Teo, S.L.; Tan, K.H. The role of food apps servitization on repurchase intention: A study of FoodPanda. International Journal of Production Economics 2021, 234, 108063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coifman, B.; Li, L. A critical evaluation of the Next Generation Simulation (NGSIM) vehicle trajectory dataset. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 2017, 105, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovic, B.; Song, G.; Gilitschenski, I.; Pavone, M. trajdata: A unified interface to multiple human trajectory datasets. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Yin, Y.; Lim, S.; Wang, G.; Hu, B.; Varadarajan, J.; Zheng, S.; Bulusu, A.; Zimmermann, R. asia. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 3rd ACM SIGSPATIAL international workshop on prediction of human mobility, 2019, pp.

- Jiang, W.; Zhu, J.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Zhao, P.; Zhao, L. A feature based method for trajectory dataset segmentation and profiling. World Wide Web 2017, 20, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.; Fung, B.; Debbabi, M. Preserving privacy and utility in RFID data publishing 2010.

- Peng, T.; Liu, Q.; Wang, G.; Xiang, Y.; Chen, S. Multidimensional privacy preservation in location-based services. Future Generation Computer Systems 2019, 93, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaham, S.; Ding, M.; Liu, B.; Dang, S.; Lin, Z.; Li, J. Privacy preservation in location-based services: A novel metric and attack model. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2020, 20, 3006–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Cai, S.; Yu, H.; Maharjan, S.; Chang, V.; Du, X.; Guizani, M. Location privacy preservation for mobile users in location-based services. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 87425–87438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gao, L.; Zheng, J.; Wei, W. Location privacy preservation mechanism for location-based service with incomplete location data. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 95843–95854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Huang, X.; Anand, V.; Sun, G.; Yu, H. k-DLCA: An efficient approach for location privacy preservation in location-based services. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC). IEEE, 2016, pp. 1–6.

- Riyana, S.; Riyana, N. A privacy preservation model for rfid data-collections is highly secure and more efficient than lkc-privacy. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Advances in Information Technology, 2021, pp. 1–11.

- Rafiei, M.; Wagner, M.; van der Aalst, W.M. TLKC-privacy model for process mining. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Research Challenges in Information Science. Springer, 2020, pp. 398–416.

- Liu, P.; Wu, D.; Shen, Z.; Wang, H. Trajectory privacy data publishing scheme based on local optimisation and R-tree. Connection Science 2023, 35, 2203880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemkumar, D.; Ravichandra, S.; Somayajulu, D. Impact of prior knowledge on privacy leakage in trajectory data publishing. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 2020, 23, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aïmeur, E.; Brassard, G.; Rioux, J. CLiKC: A privacy-mindful approach when sharing data. In Proceedings of the Risks and Security of Internet and Systems: 11th International Conference, CRiSIS 2016, Roscoff, France, September 5-7, 2016, Revised Selected Papers 11. Springer, 2017, pp. 3–10.

- Sweeney, L. Achieving k-anonymity privacy protection using generalization and suppression. International Journal of Uncertainty, Fuzziness and Knowledge-Based Systems 2002, 10, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, L. k-anonymity: A model for protecting privacy. International journal of uncertainty, fuzziness and knowledge-based systems 2002, 10, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machanavajjhala, A.; Kifer, D.; Gehrke, J.; Venkitasubramaniam, M. l-diversity: Privacy beyond k-anonymity. Acm transactions on knowledge discovery from data (tkdd) 2007, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Li, T.; Venkatasubramanian, S. t-closeness: Privacy beyond k-anonymity and l-diversity. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE 23rd international conference on data engineering. IEEE; 2006; pp. 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, T.S.; Chang, C.C. Privacy-preserving algorithms for multiple sensitive attributes satisfying t-closeness. Journal of Computer Science and Technology 2018, 33, 1231–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Roma, J.; Herrera-Joancomartí, J.; Torra, V. k-Degree anonymity and edge selection: improving data utility in large networks. Knowledge and Information Systems 2017, 50, 447–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Kate, A. Rpm: Robust anonymity at scale. Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorri, A.; Kanhere, S.S.; Jurdak, R.; Gauravaram, P. LSB: A Lightweight Scalable Blockchain for IoT security and anonymity. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 2019, 134, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojja Venkatakrishnan, S.; Fanti, G.; Viswanath, P. Dandelion: Redesigning the bitcoin network for anonymity. Proceedings of the ACM on Measurement and Analysis of Computing Systems 2017, 1, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temuujin, O.; Ahn, J.; Im, D.H. Efficient L-diversity algorithm for preserving privacy of dynamically published datasets. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 122878–122888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameshwarappa, P.; Chen, Z.; Koru, G. Anonymization of daily activity data by using l-diversity privacy model. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems (TMIS) 2021, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwork, C. Differential privacy. In Proceedings of the International colloquium on automata, languages, and programming. Springer, 2006, pp. 1–12.

- Tao, Y.; Papadias, D. Maintaining sliding window skylines on data streams. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2006, 18, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, V.; Ostrovsky, R.; Zaniolo, C. Optimal sampling from sliding windows. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the twenty-eighth ACM SIGMOD-SIGACT-SIGART symposium on Principles of database systems, 2009, pp. 147–156.

- Yang, L.; Shami, A. A lightweight concept drift detection and adaptation framework for IoT data streams. IEEE Internet of Things Magazine 2021, 4, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Shih, M.H.; Srivastava, D.; Tirthapura, S.; Xu, B. Stratified random sampling from streaming and stored data. Distributed and Parallel Databases 2021, 39, 665–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Feng, G.; Yao, G.; Li, C.; Tang, Y.; Fang, B.; Zhao, T.; Hong, Z.; Jing, X. Research progress on the principle and application of multi-dimensional information encryption based on metasurface. Optics & Laser Technology 2024, 179, 111263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.C.; Lee, J.; Chowdhury, A.; Grossman, D.; Frieder, O. On the design and evaluation of a multi-dimensional approach to information retrieval. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 23rd annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval, 2000, pp. 363–365.

- Guttman, A. R-trees: A dynamic index structure for spatial searching. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1984 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data, 1984, pp. 47–57.

- Riyana, S.; Natwichai, J. Privacy preservation for recommendation databases. Service Oriented Computing and Applications 2018, 12, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Fung, B.C.; Mohammed, N.; Desai, B.C.; Wang, K. Privacy-preserving trajectory data publishing by local suppression. Information Sciences 2013, 231, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnsamut, N.; Natwichai, J.; Riyana, S. Privacy preservation for trajectory data publishing by look-up table generalization. In Proceedings of the Australasian Database Conference. Springer International Publishing Cham, 2018, pp. 15–27.

- Harnsamut, N.; Natwichai, J. Privacy-aware trajectory data publishing: an optimal efficient generalisation algorithm. International Journal of Grid and Utility Computing 2023, 14, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Path | Diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|

| HIV | ||

| Food poisoning | ||

| Leukemia | ||

| Gerd | ||

| Cancer | ||

| Flu | ||

| Diabetes | ||

| Tuberculosis | ||

| Conjunctiva | ||

| Flu |

| Path | Diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|

| HIV | ||

| Food poisoning | ||

| Leukemia | ||

| Gerd | ||

| Cancer | ||

| Flu | ||

| Diabetes | ||

| Tuberculosis | ||

| Conjunctiva | ||

| Flu |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).