Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

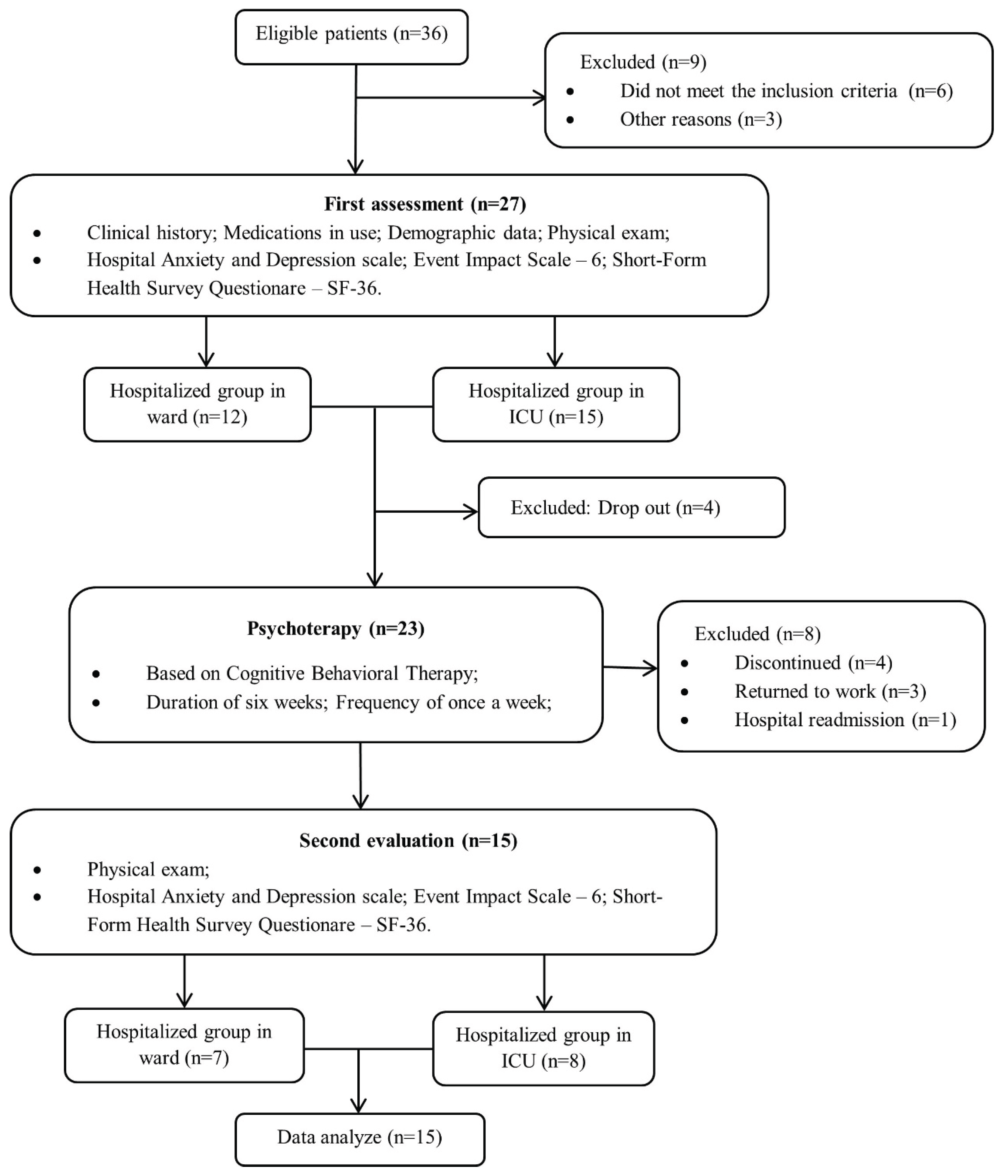

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Ethical Aspects

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

2.3.2. Event Impact Scale – IES-6

2.3.3. Short-Form Health Survey – SF-36

2.4. Psychological Intervention

2.5. Statistical Analysis and Sample Size

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. 2021. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 20 Oct 2024).

- World Health Organization. Diagnostic testing for SARS-CoV-2: Interim guidance. COVID-19: Laboratory and diagnosis. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publi cations/i/item/diagnostic-testing-for-sars-cov-2 (accessed on 20 Oct 2024).

- Jung G, Ha JS, Seong M, Song JH. The Effects of Depression and Fear in Dual-Income Parents on Work-Family Conflict During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sage Open. 2023, 13, 21582440231157662. [CrossRef]

- Azizi A, Achak D, Saad E, Hilali A, Youlyouz-Marfak I, Marfak A. Post-COVID-19 mental health and its associated factors at 3-months after discharge: A case-control study. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2022, 17, 101141. [CrossRef]

- García-Molina A, García-Carmona S, Espiña-Bou M, Rodríguez-Rajo P, Sánchez-Carrión R, Enseñat-Cantallops A. Neuropsychological rehabilitation for post-COVID-19 syndrome: results of a clinical programme and six-month follow up. Neurologia (Engl Ed). 2022, 39, 592-603. [CrossRef]

- Lee AM, Wong JG, McAlonan GM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Sham PC, et al. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatry. 2007, 52, 233-40. [CrossRef]

- Lee SH, Shin HS, Park HY, Kim JL, Lee JJ, Lee H, et al. Depression as a Mediator of Chronic Fatigue and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Survivors. Psychiatry Investig. 2019, 16, 59-64. [CrossRef]

- Zeng N, Zhao YM, Yan W, Li C, Lu QD, Liu L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of long term physical and mental sequelae of COVID-19 pandemic: call for research priority and action. Mol Psychiatry. 2023, 28, 423-433. [CrossRef]

- Altundal Duru H, Yılmaz S, Yaman Z, Boğahan M, Yılmaz M. Individuals' Coping Styles and Levels of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Sage Open. 2023, 13, 21582440221148628. [CrossRef]

- Filgueiras A, Stults-Kolehmainen M. Risk Factors for Potential Mental Illness Among Brazilians in Quarantine Due To COVID-19. Psychol Rep. 2022, 125, 723-741.

- Bellan M, Soddu D, Balbo PE, Baricich A, Zeppegno P, Avanzi GC, et al. Respiratory and Psychophysical Sequelae Among Patients With COVID-19 Four Months After Hospital Discharge. JAMA Netw Open. 2021, 4, e2036142. [CrossRef]

- Hammerle MB, Sales DS, Pinheiro PG, Gouvea EG, de Almeida PIFM, de Araujo Davico C, et al. Cognitive Complaints Assessment and Neuropsychiatric Disorders After Mild COVID-19 Infection. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2023, 38, 196-204. [CrossRef]

- Huang L, Li X, Gu X, Zhang H, Ren L, Guo L, et al. Health outcomes in people 2 years after surviving hospitalisation with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022, 10, 863-876. [CrossRef]

- Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021, 8, 416-427. [CrossRef]

- Al-Jassas HK, Al-Hakeim HK, Maes M. Intersections between pneumonia, lowered oxygen saturation percentage and immune activation mediate depression, anxiety, and chronic fatigue syndrome-like symptoms due to COVID-19: A nomothetic network approach. J Affect Disord. 2022, 297, 233-245. [CrossRef]

- Akova İ, Kiliç E, Özdemir ME. Prevalence of Burnout, Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Hopelessness Among Healthcare Workers in COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey. Inquiry. 2022, 59, 469580221079684. [CrossRef]

- Bortolato B, Carvalho AF, Soczynska JK, Perini GI, McIntyre RS. The Involvement of TNF-α in Cognitive Dysfunction Associated with Major Depressive Disorder: An Opportunity for Domain Specific Treatments. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015, 13, 558-76. [CrossRef]

- Ou X, Liu Y, Lei X, Li P, Mi D, Ren L, et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2020, 11, 1620. [CrossRef]

- Badenoch J, Cross B, Hafeez D, Song J, Watson C, Butler M, et al. Post-traumatic symptoms after COVID-19 may (or may not) reflect disease severity. Psychol Med. 2023, 53, 295-296. [CrossRef]

- Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, Pollak TA, McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020, 7, 611-627. [CrossRef]

- Huang L, Yao Q, Gu X, Wang Q, Ren L, Wang Y, et al. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2021, 398, 747-758. [CrossRef]

- Song J, Jiang R, Chen N, Qu W, Liu D, Zhang M, et al. Self-help cognitive behavioral therapy application for COVID-19-related mental health problems: A longitudinal trial. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021, 60, 102656. [CrossRef]

- Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N; TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004, 94, 361-6. PMID: 14998794; PMCID: PMC1448256. [CrossRef]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983, 67, 361-70. [CrossRef]

- Hosey MM, Leoutsakos JS, Li X, Dinglas VD, Bienvenu OJ, Parker AM, et al. Screening for posttraumatic stress disorder in ARDS survivors: validation of the Impact of Event Scale-6 (IES-6). Crit Care. 2019, 23, 276. [CrossRef]

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992, 30, 473-83.

- Beck JS. Terapia cognitivo-comportamental: Teoria e prática. Porto Alegre: Artmed. 2013.

- Beck JS, Knapp P. Terapia cognitivo-comportamental: Teoria e prática. 3ª ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed. 2021.

- Deng J, Zhou F, Hou W, Silver Z, Wong CY, Chang O, et al. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2021, 1486, 90-111. [CrossRef]

- Mazza MG, De Lorenzo R, Conte C, Poletti S, Vai B, Bollettini I, et al. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav Immun. 2020, 89, 594-600. [CrossRef]

- Carrijo M, Oliveira MC, Oliveira AC, Lino MEM, Souza SKA, Afonso JPR, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression in post-COVID19 patients: integrative review. Mtprehabjournal. 2022, 20, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Delmo J, Portillo De-Antonio P, Porras-Segovia A, de León-Martínez S, Figuero Oltra M, del Pozo-Herce P, Sánchez-Escribano Martínez A, Abejón Pérez I, Vera-Varela C, Postolache TT, et al. Onset of mental disorders following hospitalization for COVID-19: a 6-month follow-up study. COVID. 2023, 3, 218-225. [CrossRef]

- Vlake JH, Wesselius S, van Genderen ME, van Bommel J, Boxma-de Klerk B, Wils EJ. Psychological distress and health-related quality of life in patients after hospitalization during the COVID-19 pandemic: A single-center, observational study. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0255774. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Tian J, Xu Q. The Associated Factors of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in COVID-19 Patients Hospitalized in Wuhan, China. Psychiatr Q. 2021, 92, 879-887. [CrossRef]

- Olgun Yıldızeli S, Kocakaya D, Saylan YH, Tastekin G, Yıldız S, Akbal Ş, et al. Anxiety, Depression, and Sleep Disorders After COVID-19 Infection. Cureus. 2023, 15, e42637. [CrossRef]

- Khatun K, Farhana N. Assessment of Level of Depression and Associated Factors among COVID-19-Recovered Patients: a Cross-Sectional Study. Microbiol Spectr. 2023, 11, e0465122. [CrossRef]

- Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, et al. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020, 323, 1574-1581. [CrossRef]

- Poudel AN, Zhu S, Cooper N, Roderick P, Alwan N, Tarrant C, et al. Impact of Covid-19 on health-related quality of life of patients: A structured review. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0259164. [CrossRef]

- Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Cheung T, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020, 7, 228-229. [CrossRef]

- First MB. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, and clinical utility. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013, 201, 727-9. [CrossRef]

- Bonazza F, Borghi L, di San Marco EC, Piscopo K, Bai F, Monforte AD, et al. Psychological outcomes after hospitalization for COVID-19: data from a multidisciplinary follow-up screening program for recovered patients. Res Psychother. 2021, 23, 491. [CrossRef]

- Shanbehzadeh S, Tavahomi M, Zanjari N, Ebrahimi-Takamjani I, Amiri-Arimi S. Physical and mental health complications post-COVID-19: Scoping review. J Psychosom Res. 2021, 147, 110525. [CrossRef]

- Coventry PA, Meader N, Melton H, Temple M, Dale H, Wright K, et al. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental health problems following complex traumatic events: Systematic review and component network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003262. [CrossRef]

- Merz J, Schwarzer G, Gerger H. Comparative Efficacy and Acceptability of Pharmacological, Psychotherapeutic, and Combination Treatments in Adults With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019, 76, 904-913. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira MC, Carrijo MM, Afonso JPR, Moura RS, Oliveira LFRJ, Fonseca AL, et al. Effects of hospitalization on functional status and health-related quality of life of patients with COVID-19 complications: a literature review. Mtprehabjournal. 2022, 20. [CrossRef]

- Hu J, Zhang Y, Xue Q, Song Y, Li F, Lei R, et al. Early Mental Health and Quality of Life in Discharged Patients With COVID-19. Front Public Health. 2021, 9, 725505. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Canales LG, Muñoz-Corona C, Barrera-Chávez I, Viloria-Álvarez C, Macías AE, Guaní-Guerra E. Quality of Life and Persistence of Symptoms in Outpatients after Recovery from COVID-19. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022, 58, 1795. [CrossRef]

- Germann N, Amozova D, Göhl-Freyn K, Fischer T, Frischknecht M, Kleger G-R, Pietsch U, Filipovic M, Brutsche MH, Frauenfelder T, et al. Evaluation of psychosomatic, respiratory, and neurocognitive health in COVID-19 survivors 12 months after ICU discharge. COVID. 2024, 4, 1172-1185. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Corona C, Gutiérrez-Canales LG, Ortiz-Ledesma C, Martínez-Navarro LJ, Macías AE, Scavo-Montes DA, et al. Quality of life and persistence of COVID-19 symptoms 90 days after hospital discharge. J Int Med Res. 2022, 50, 3000605221110492. [CrossRef]

- Koullias E, Fragkiadakis G, Papavdi M, Manousopoulou G, Karamani T, Avgoustou H, et al. Long-Term Effect on Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With COVID-19 Requiring Hospitalization Compared to Non-hospitalized COVID-19 Patients and Healthy Controls. Cureus. 2022, 14, e31342. [CrossRef]

- da Silveira AD, Scolari FL, Saadi MP, Brahmbhatt DH, Milani M, Milani JGPO, et al. Long-term reduced functional capacity and quality of life in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Frontiers in Medicine. 2024, 10, 1289454. [CrossRef]

- Bolgeo T, Di Matteo R, Gatti D, Cassinari A, Damico V, Ruta F, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on Quality of Life After Hospital Discharge in Patients Treated With Noninvasive Ventilation/Continuous Positive Airway Pressure: An Observational, Prospective Multicenter Study. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 2024, 43, 3–12.

- Wiertz CMH, Hemmen B, Sep SJS, van Santen S, van Horn YY, van Kuijk SMJ, et al. Life after COVID-19: the road from intensive care back to living - a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2022, 12, e062332. [CrossRef]

- Rizanaj N, Gavazaj F. Effects of depressive and anxiety-related behaviors in patients aged 30–75+ who have experienced COVID-19. COVID. 2024, 4, 1041-1060. [CrossRef]

- Mazurek J, Cieślik B, Szary P, Rutkowski S, Szczegielniak J, Szczepańska-Gieracha J, et al. Association of Acute Headache of COVID-19 and Anxiety/Depression Symptoms in Adults Undergoing Post-COVID-19 Rehabilitation. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 5002. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Qiao D, Xu Y, Zhao W, Yang Y, Wen D, et al. The Efficacy of Computerized Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Patients With COVID-19: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26883. [CrossRef]

- Asimakos A, Spetsioti S, Mavronasou A, Gounopoulos P, Siousioura D, Dima E, et al. Additive benefit of rehabilitation on physical status, symptoms and mental health after hospitalisation for severe COVID-19 pneumonia. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2023, 10, e001377. [CrossRef]

- Jin Y, Xu J, Liu D. The relationship between post traumatic stress disorder and post traumatic growth: gender differences in PTG and PTSD subgroups. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 1903-10. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi H, Saffari M, Movahedi M, Sanaeinasab H, Rashidi-Jahan H, Pourgholami M, et al. A mediating role for mental health in associations between COVID-19-related self-stigma, PTSD, quality of life, and insomnia among patients recovered from COVID-19. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e02138. [CrossRef]

- Khan S, Siddique R, Li H, Ali A, Shereen MA, Bashir N, et al. Impact of coronavirus outbreak on psychological health. J Glob Health. 2020, 10, 010331. [CrossRef]

- Zysberg L, Zisberg A. Days of worry: Emotional intelligence and social support mediate worry in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 268-277. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Li X, Jiang J, Xu X, Wu J, Xu Y, et al. The Effect of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Patients With COVID-19: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Psychiatry. 2020, 11, 580827. [CrossRef]

- Cheng P, Kalmbach DA, Tallent G, Joseph CL, Espie CA, Drake CL. Depression prevention via digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2019, 42, zsz150. [CrossRef]

- Kong X, Kong F, Zheng K, Tang M, Chen Y, Zhou J, et al. Effect of Psychological-Behavioral Intervention on the Depression and Anxiety of COVID-19 Patients. Front Psychiatry. 2020, 11, 586355. [CrossRef]

- Vink M, Vink-Niese A. Could Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Be an Effective Treatment for Long COVID and Post COVID-19 Fatigue Syndrome? Lessons from the Qure Study for Q-Fever Fatigue Syndrome. Healthcare (Basel). 2020, 8, 552. [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski S, Bogacz K, Czech O, Rutkowska A, Szczegielniak J. Effectiveness of an Inpatient Virtual Reality-Based Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program among COVID-19 Patients on Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression and Quality of Life: Preliminary Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19, 16980. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total (n=15) | WG (n=7) | ICUG (n=8) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idade, média (dp) | 53,4 (14,1) | 51,7 (17,4) | 54,9 (11,4) | 0,68¹ |

| Sex, n (%) | 0,28² | |||

| Female | 10 (66,7) | 6(85,7) | 5(50) | |

| Male | 5(33,3) | 1(14,3) | 4(50) | |

| Self-reported race, n (%) | 0,5² | |||

| White | 2(13,4) | 0 | 2(25,0) | |

| Brown | 8(53,3) | 5(71,4) | 3(37,5) | |

| Black | 5(33,3) | 2(28,6) | 3(37,5) | |

| Educational status, n (%) | 1² | |||

| Incomplete elementar school | 2(13,3) | 1(14,3) | 1(12,5) | |

| Complete primary school | 3(20,0) | 1(14,3) | 2(25,0) | |

| High school | 7(46,7) | 3(42,9) | 4(50,0) | |

| University education | 3(20,0) | 2(28,6) | 1(12,5) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| DM | 4 (26,7) | 1(14,3) | 3(37,5) | 0,56² |

| SAH | 6(40,0) | 2(28,6) | 4(50,0) | 0,6² |

| Respiratory diseases | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Hepatic steatosis | 2(13,3) | 0 | 2(25,0) | 0,46² |

| Obesity | 3(20,0) | 0 | 3(37,5) | 0,2² |

| Dyslipidemia | 1(6,7) | 0 | 1(12,5) | 1² |

| Anxiety, n (%) | 8(53,3) | 2(28,6) | 6(75,0) | 0,13¹ |

| Depression, n (%) | 3(20,0) | 2(28,6) | 1(12,5) | 0,56¹ |

| Hospitalization time, n (%) | 11,3 (10,1) | 6,4 (6,5) | 15,5 (11,2) | 0,08¹ |

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | p WG pre x post² |

p ICUG pre x post² |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WG (n=7) | ICUG (n=8) | p | WG (n=7) | ICUG (n=8) | p | |||

| IES | 0,2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| <10 | 0 | 2(28,6) | 7(87,5) | 6(85,7) | ||||

| ≥ 10 | 8(100,0) | 5(71,4) | 1(12,5) | 1(14,3) | ||||

| TEPT | 1 | --- | 0,38 | 0,34 | ||||

| <1.09 | 4(50,0) | 4(57,1) | 8(100,0) | 7(100,0) | ||||

| ≥1.09 | 4(50,0) | 3(42,9) | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Depression (HADS-D) | 0,53 | 0,56 | --- | --- | ||||

| Unlikely diagnosis | 2(25,0) | 1(14,3) | 5(62,5) | 6(85,7) | ||||

| Possible diagnosis | 2(25,0) | 4(57,1) | 3(37,5) | 1(14,3) | ||||

| Probable diagnosis | 4(50,0) | 2(28,6) | ||||||

| Anxiety (HADS-A) | 1 | 0,56 | --- | --- | ||||

| Unlikely diagnosis | 1(12,5) | 1(14,3) | 7(87,5) | 5(71,4) | ||||

| Possible diagnosis | 4(50,0) | 4(57,1) | 1(12,5) | 2(28,6) | ||||

| Probable diagnosis | 3(37,5) | 2(28,6) | ||||||

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | p ICUG | p WG | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WG | ICUG | p¹ | WG | ICUG | p¹ | pré x pós | pré x pós | |

| TEPT average (sd) | 0,8(0,3) | 1,0(0,2) | 0,1¹ | 0,4(0,2) | 0,8(0,3) | 0,86¹ | 0,001² | 0,004² |

| Depression (HADS) (IQ) | 10(8-12) | 10(7,5-13,5) | 0,86³ | 4(3-7) | 5(2,5-8) | 0,72³ | 0,014 | 0,014 |

| Anxiety (HADS) (IQ) | 10(9-12) | 10(9,5-12,5) | 0,51³ | 6(2-8) | 5,5(2-6,5) | 0,48³ | 0,014 | 0,014 |

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | p ICUG pre x pós² |

p WG pre x pós² |

Δ ICUG |

Δ WG |

p Δ¹ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 | ICUG | WG | p¹ | ICUG | WG | p¹ | |||||

| Functional capacity | 28,7(19,3) | 50,7(30,6) | 0,11 | 56,2(25,6) | 62,1(24,5) | 0,65 | 0,01 | 0,17 | 27,5(25,2) | 11,4(19,5) | 0,19 |

| Physical aspects | 0 | 42,8(42,6) | 0,0062 | 28,1(33,9) | 46,4(36,6) | 0,33 | 0,04 | 0,79 | 28,1(33,9) | 3,6(62,0) | 0,35 |

| Pain | 55,5(30,0) | 58,6(27,2) | 0,84 | 71,2(27,7) | 64,6(24,9) | 0,63 | 0,13 | 0,41 | 15,7(26,0) | 6,0(18,0) | 0,42 |

| General health status | 48,6(15,1) | 50,3(19,2) | 0,85 | 55,5(11,6) | 64,6(16,9) | 0,24 | 0,18 | 0,01 | 6,9(13,2) | 14,3(11,1) | 0,26 |

| Vitality | 49,4(18,0) | 50,7(7,3) | 0,55* | 63,1(18,7) | 62,1(20,8) | 0,92 | 0,01 | 0,12 | 13,7(16,8) | 11,4(16,5) | 0,79 |

| Social aspects | 48,4(25,4) | 55,3(25,9) | 0,61 | 65,6(23,8) | 67,8(27,8) | 0,87 | 0,12 | 0,15 | 17,2(28,3) | 12,5(20,4) | 0,72 |

| Emotional aspects | 25(23,8) | 61,9(35,6) | 0,01 | 58,3(38,8) | 57,1(16,2) | 0,94 | 0,01 | 0,8 | 33,3(30,9) | -4,8(48,9) | 0,08 |

| Mental Health | 52,7(22,3) | 52,6(14,7) | 0,98 | 66,5(21,8) | 66,8(17,5) | 0,97 | 0,02 | 0,01 | 13,7(13,7) | 14,3(10,5) | 0,93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).