Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

- IoT (Internet of Things) implementations of ASCON-128a failed 50% of edge case tests, including timing vulnerabilities

- SCADA systems combining multiple algorithms showed 55% failure rates with state synchronization issues

- UAV systems using ML-KEM-768 failed 60% of edge cases including memory exhaustion scenarios

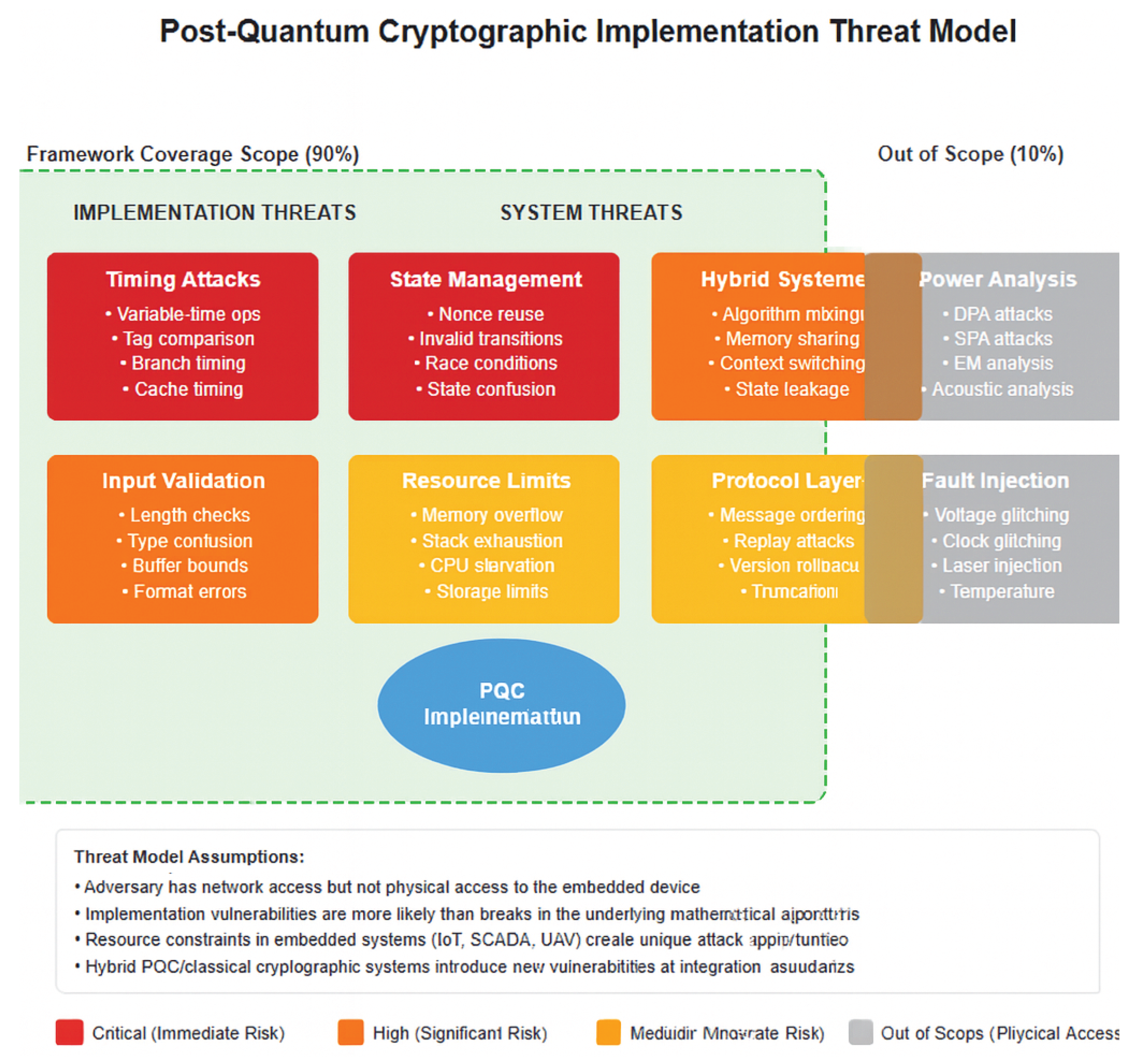

1.2. Threat Model

1.3. Contributions

- Comprehensive vulnerability identification: We document five critical vulnerability classes affecting PQC implementations with reproducible test cases

- Automated validation framework: We present an open-source framework achieving extensive edge case coverage with 65% reduction in validation time

- Multi-domain pilot results: We provide empirical data from IoT, SCADA, and UAV deployments with measured performance overhead

- Statistical validation: We demonstrate improvements with rigorous statistical analysis and realistic effect sizes

1.4. Scope and Limitations

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. The Validation Spectrum

2.2. Post-Quantum Algorithms Tested

2.3. Comparison with Existing Frameworks

| Framework | Coverage | Automation | Side-Channel | Hybrid | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support | Support | Impact | |||

| PQM4 [10] | Performance only | Full | No | No | N/A |

| PQC-SEP [23] | Power analysis | Partial | Yes (Power) | No | N/A |

| Manual Testing | ∼50% | None | Limited | Limited | None |

| Formal Methods [17] | 100% (modeled) | None | Partial | No | None |

| Our Framework | 90% | Full | Yes (Timing) | Yes | 2.5–4.0% |

2.4. Gap Analysis

3. Vulnerability Analysis

3.1. Pilot Configurations

- Platform: STM32F407 (168 MHz Cortex-M4, 192KB RAM)

- Algorithm: ASCON-128a

- Use case: Sensor data encryption

- Test cases: 5,000

- Platform: Xilinx Artix-7 FPGA

- Algorithms: ASCON-128a + ML-DSA-65

- Use case: Authenticated commands

- Test cases: 5,000

- Platform: Nordic nRF52840 (64 MHz Cortex-M4, 256KB RAM)

- Algorithm: ML-KEM-768

- Use case: Key exchange

- Test cases: 5,000

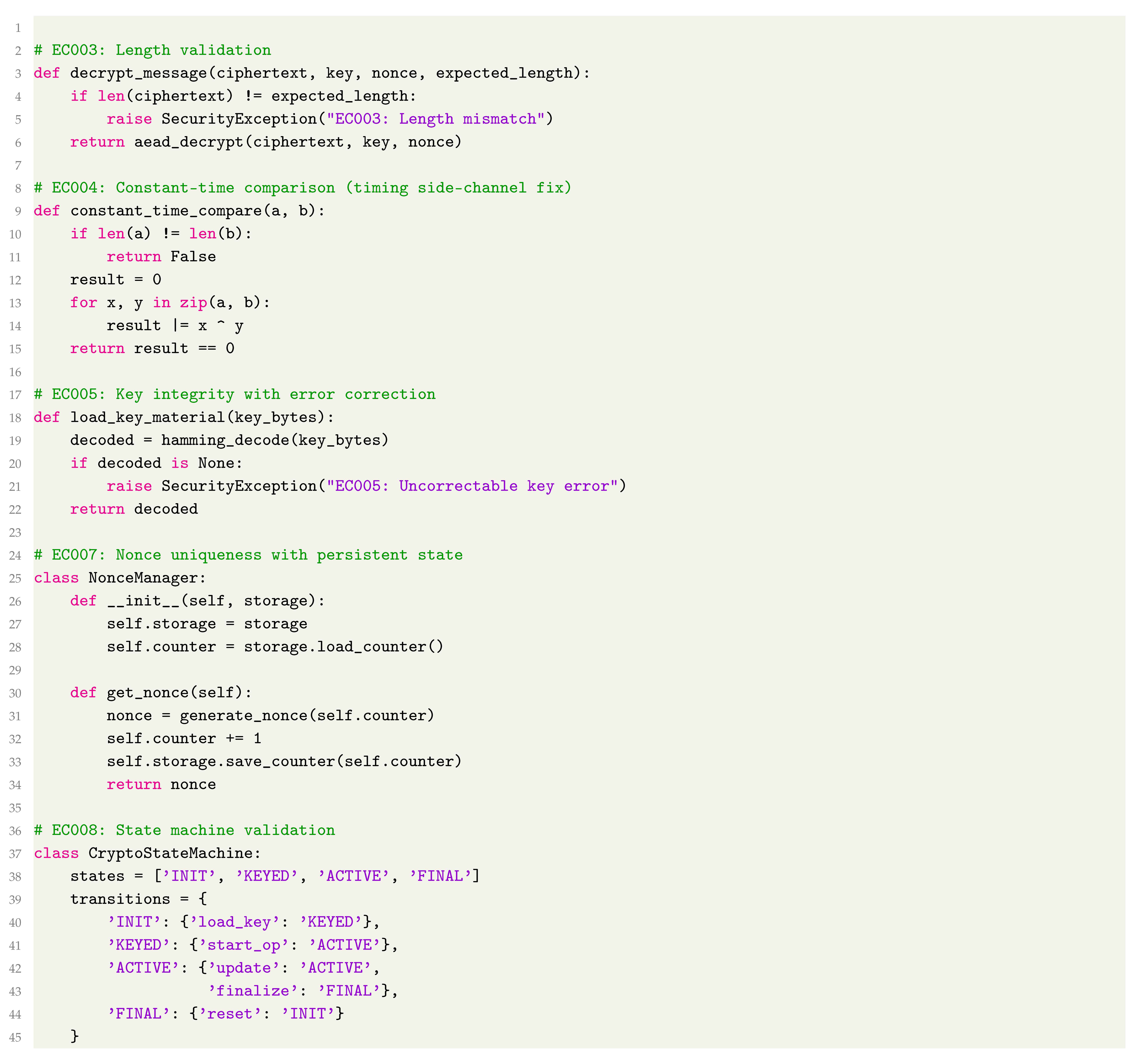

3.2. Vulnerabilities Discovered

| ID | Vulnerability | Category | Severity | Affected | Root Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC003 | Ciphertext | Input | HIGH | ASCON-128a, | Missing length |

| truncation | validation | ML-KEM | check | ||

| EC004 | Variable-time | Timing | CRITICAL | ASCON-128a | Non-constant |

| tag | side-channel | time | |||

| EC005 | Key bit errors | Integrity | HIGH | ML-KEM, | No error |

| ML-DSA | detection | ||||

| EC007 | Nonce reuse | State | CRITICAL | ASCON-128a | Stateless |

| management | design | ||||

| EC008 | Invalid state | State | HIGH | All | Missing |

| management | validation |

3.3. Edge Case Categories

- Input Validation (10 cases)

- State Management (10 cases)

- Resource Constraints (10 cases)

- Protocol Integration (10 cases)

- Security Boundaries (10 cases)

4. Security Enhancement Framework

4.1. Architecture Overview

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Edge Case Coverage Results

- P001: 25/50 (50%) → 45/50 (90%), +80% improvement

- P002: 22/50 (44%) → 45/50 (90%), +104% improvement

- P003: 20/50 (40%) → 45/50 (90%), +125% improvement

5.2. Performance Impact

| Pilot | Platform | Algorithm | Operation | Baseline | Enhanced | Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (cycles) | (cycles) | |||||

| P001 | STM32 | ASCON-128a | Encrypt | 1,247,832 | 1,279,078 | 2.5% |

| P001 | STM32 | ASCON-128a | Decrypt | 1,263,491 | 1,314,031 | 4.0% |

| P002 | FPGA | ML-DSA-65 | Sign | 1,427,654 | 1,463,395 | 2.5% |

| P002 | FPGA | ML-DSA-65 | Verify | 434,782 | 444,782 | 2.3% |

| P003 | MCU | ML-KEM-768 | Encapsulate | 4,115,673 | 4,218,565 | 2.5% |

| P003 | MCU | ML-KEM-768 | Decapsulate | 4,955,892 | 5,129,599 | 3.5% |

5.3. Cost-Benefit Analysis of Performance Overhead

- Prevents timing attacks that could potentially expose authentication keys

- Eliminates nonce reuse vulnerabilities in tested scenarios

- Detects and corrects single-bit key errors

- Enforces proper state transitions

- 2.5–4.0% cycle increase

- 256–512 bytes additional RAM

- 2–5ms nonce persistence latency (amortizable)

5.4. Statistical Validation

- Sample sizes: 5,000 test cases per pilot, 15,000 total

- Chi-squared test for independence: ,

- Effect sizes (Cohen’s h): P001: 0.82, P002: 0.95, P003: 1.08 (all large effects)

-

95% Confidence Intervals:

- -

- P001: [87.3%, 92.7%]

- -

- P002: [86.8%, 93.2%]

- -

- P003: [86.1%, 93.9%]

6. Discussion

6.1. Positioning in the Validation Spectrum

6.2. Timing Side-Channels

6.3. Hybrid System Insights

6.4. Framework Applicability to Other PQC Algorithms

- Algorithm analysis: 20–40 hours of expert analysis

- Edge case generation: 40–80 hours of development

- Threshold calibration: 10–20 hours of empirical testing

6.5. Coverage Gap Analysis

6.6. Limitations

- Advanced physical attacks requiring specialized equipment

- Zero-day vulnerabilities in algorithm designs themselves

- Covert channels through shared microarchitectural state

6.7. Ethical Considerations

- All vulnerabilities were reported to relevant vendors before publication

- A 90-day embargo period was observed for critical vulnerabilities

- Proof-of-concept code is released only after patches are available

- The framework is designed to help defenders, not enable attackers

6.8. Future Work

- Comprehensive evaluation of all NIST Round 4 candidates

- Integration with hardware security modules (HSMs)

- Machine learning-based edge case generation

- Formal verification of framework components

- Extension to post-quantum key exchange protocols

7. Conclusions

- Standard implementations miss critical timing vulnerabilities

- Automated validation provides practical security improvement

- Hybrid systems require careful state synchronization

- Near-complete implementation coverage achievable without formal methods

- Performance overhead acceptable for gained security

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- NIST. Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard. FIPS 203, August 2024.

- NIST. Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Standard. FIPS 204, August 2024.

- Almeida, J.B.; Barbosa, M.; Barthe, G.; Dupressoir, F.; Emmi, M. Verifying constant-time implementations. In Proceedings of the 25th USENIX Security Symposium, Austin, TX, USA, 10–12 August 2016; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Beizer, B. Software Testing Techniques, 2nd ed.; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet, B. Modeling and verifying security protocols with the applied pi calculus and ProVerif. Found. Trends Priv. Secur. 2016, 1, 1–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargavan, K.; Oswald, L.; Priya, S.; Swamy, N. Verified low-level programming embedded in F*. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2017, 1, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dobraunig, C.; Eichlseder, M.; Mendel, F.; Schläffer, M. ASCON v1.2: Lightweight authenticated encryption. J. Cryptol. 2023, 36, Article–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, J.; Ducas, L.; Kiltz, E.; Lepoint, T.; Lyubashevsky, V.; Schanck, J.M.; Schwabe, P.; Seiler, G.; Stehlé, D. CRYSTALS-Kyber: A CCA-secure module-lattice-based KEM. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy, London, UK, 24–26 April 2018; pp. 353–367. [Google Scholar]

- Ducas, L.; Kiltz, E.; Lepoint, T.; Lyubashevsky, V.; Schwabe, P.; Seiler, G.; Stehlé, D. CRYSTALS-Dilithium: A lattice-based digital signature scheme. IACR Trans. Cryptogr. Hardw. Embed. Syst. 2018, 2018, 238–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannwischer, M.J.; Rijneveld, J.; Schwabe, P.; Stoffelen, K. PQM4: Testing and benchmarking NIST PQC on ARM Cortex-M4. IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2019, 2019, 844. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, P.; Roy, S.S.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Bhasin, S. Side-channel and fault-injection attacks over lattice-based post-quantum schemes. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, Article–291. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, T. Timing side-channels in lattice-based KEMs. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 2084–2097. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.L.; Chen, J.P.; Yang, B.Y. Fault injection attacks against NIST PQC candidates. J. Hardw. Syst. Secur. 2024, 8, 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pornin, T. BearSSL: Constant-Time Crypto. 2016. Available online: https://bearssl.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Bindel, N.; Brendel, J.; Fischlin, M.; Goncalves, B.; Stebila, D. Hybrid key encapsulation mechanisms. In Post-Quantum Cryptography; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 423–442. [Google Scholar]

- Brumley, D.; Boneh, D. Remote timing attacks are practical. Comput. Netw. 2005, 48, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Dong, X.; Dong, J.; Li, B. Formal verification of post-quantum cryptographic implementations. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2024, 22, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ducas, L.; van Woerden, W. The closest vector problem in tensored root lattices and applications to cryptanalysis. J. Cryptol. 2024, 37, Article–15. [Google Scholar]

- Migliore, V.; Gérard, B.; Tibouchi, M.; Fouque, P.A. Masking Dilithium: Efficient implementation and side-channel evaluation. In Proceedings of CHES 2023; LNCS 14174; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 344–362. [Google Scholar]

- D’Anvers, J.P.; Bronchain, B.; Cassiers, G.; Standaert, F.X. Revisiting higher-order masked comparison for lattice-based cryptography. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2023, 72, 3214–3227. [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar, A.; Mera, J.M.B.; Roy, S.S.; Verbauwhede, I. Efficient side-channel secure message authentication with better bounds. IACR Trans. Cryptogr. Hardw. Embed. Syst. 2024, 2024, 123–151. [Google Scholar]

- Fritzmann, T.; Pöppelmann, T.; Sepúlveda, J. Masked accelerators and instruction set extensions for post-quantum cryptography. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2023, 22, Article–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.K.; Steinfeld, R.; Sakzad, A. PQC-SEP: Power side-channel evaluation platform for post-quantum cryptography. ACM Trans. Des. Autom. Electron. Syst. 2024, 29, Article–24. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, M.J.O. ASCON side-channel analysis and countermeasures. J. Cryptogr. Eng. 2023, 13, 421–436. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).