Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. GLORYS12 Monthly Average Ocean Reanalysis and ENSO Index

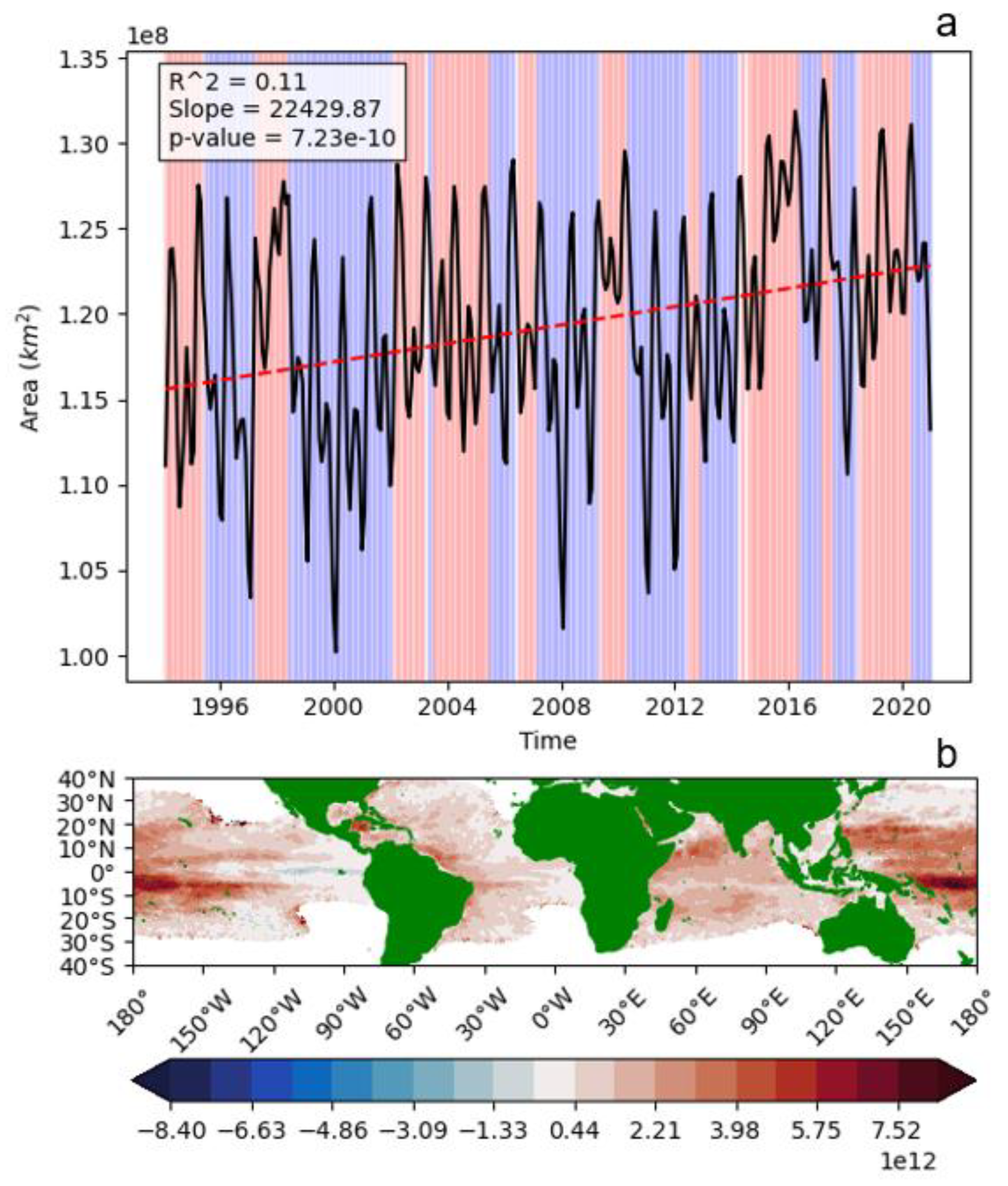

2.2. OHC100, Its Time Tendency, and Horizontal Advections

2.3. Quantifying Correlations, Residuals, and ENSO Impacts

3. Results

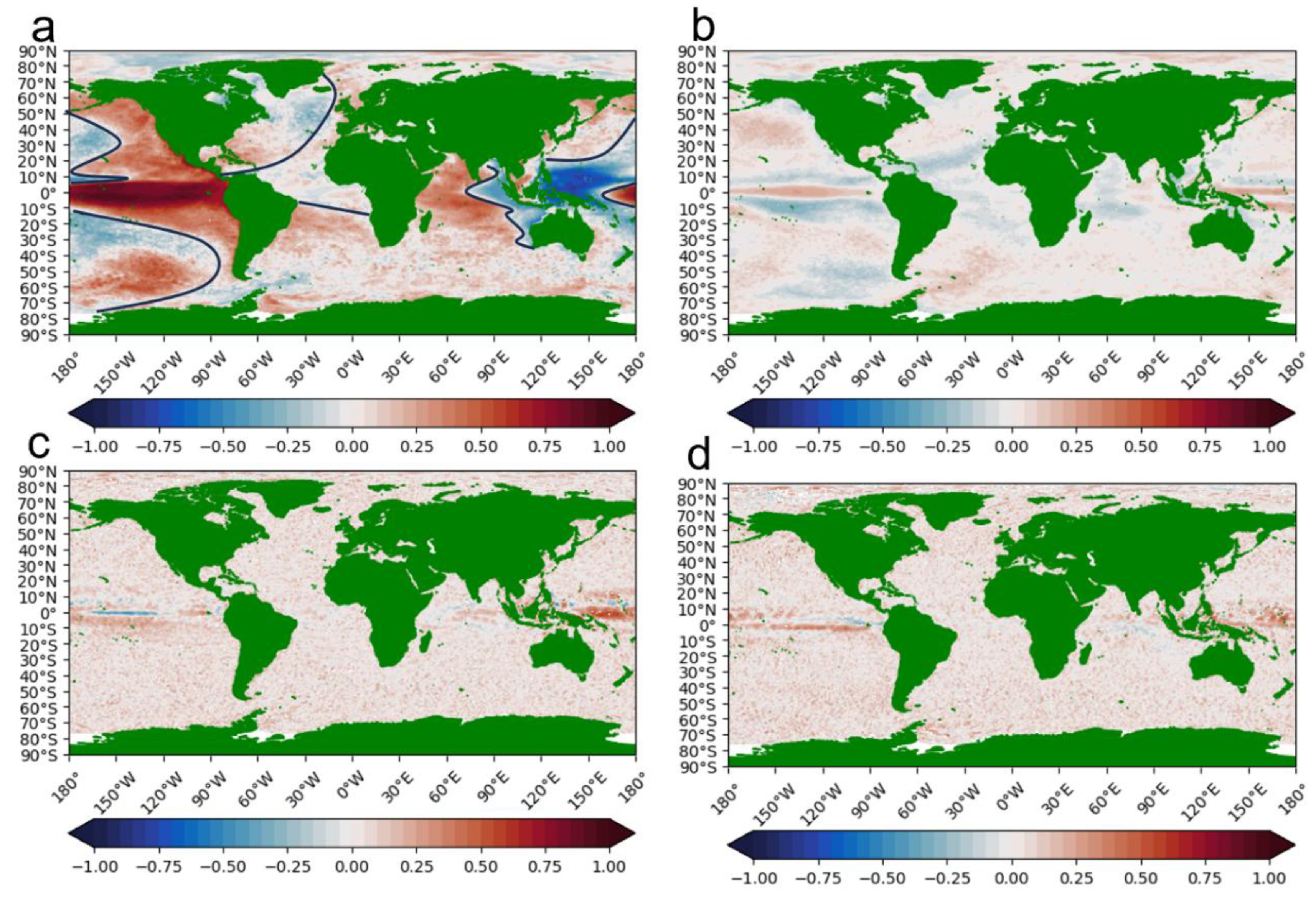

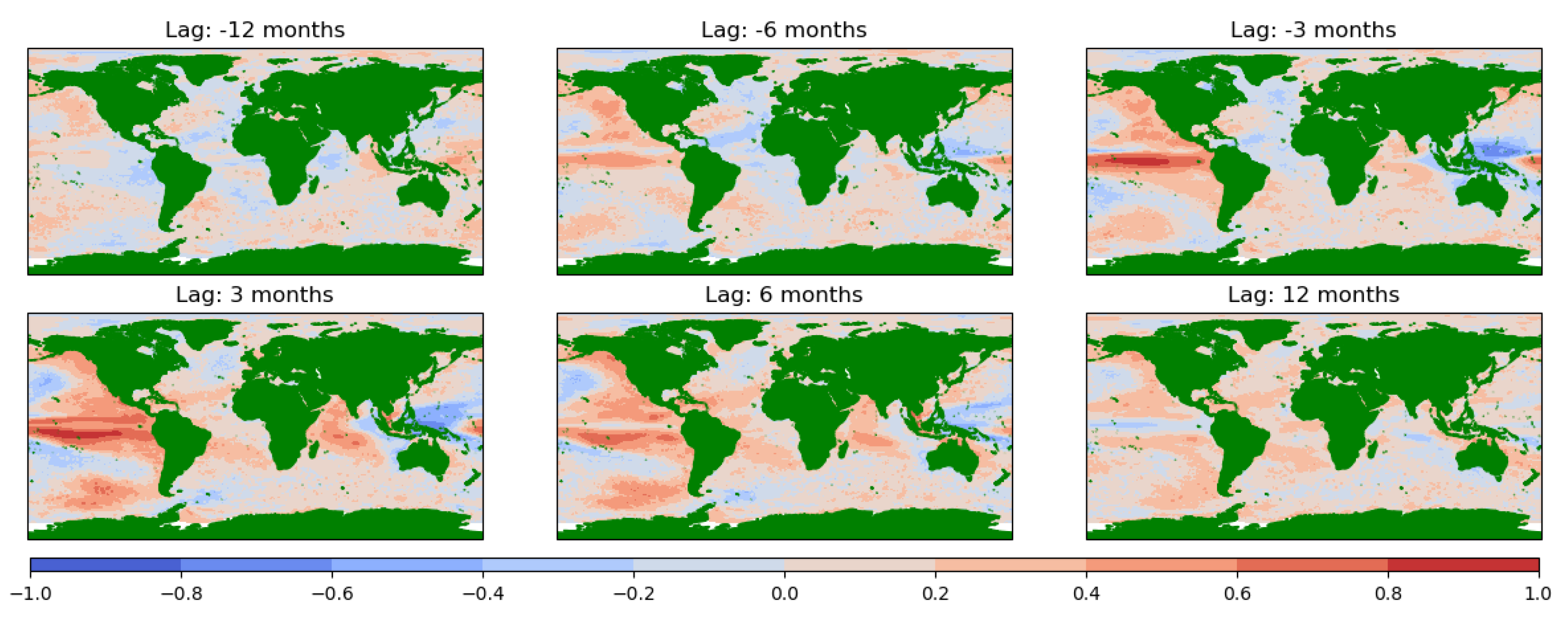

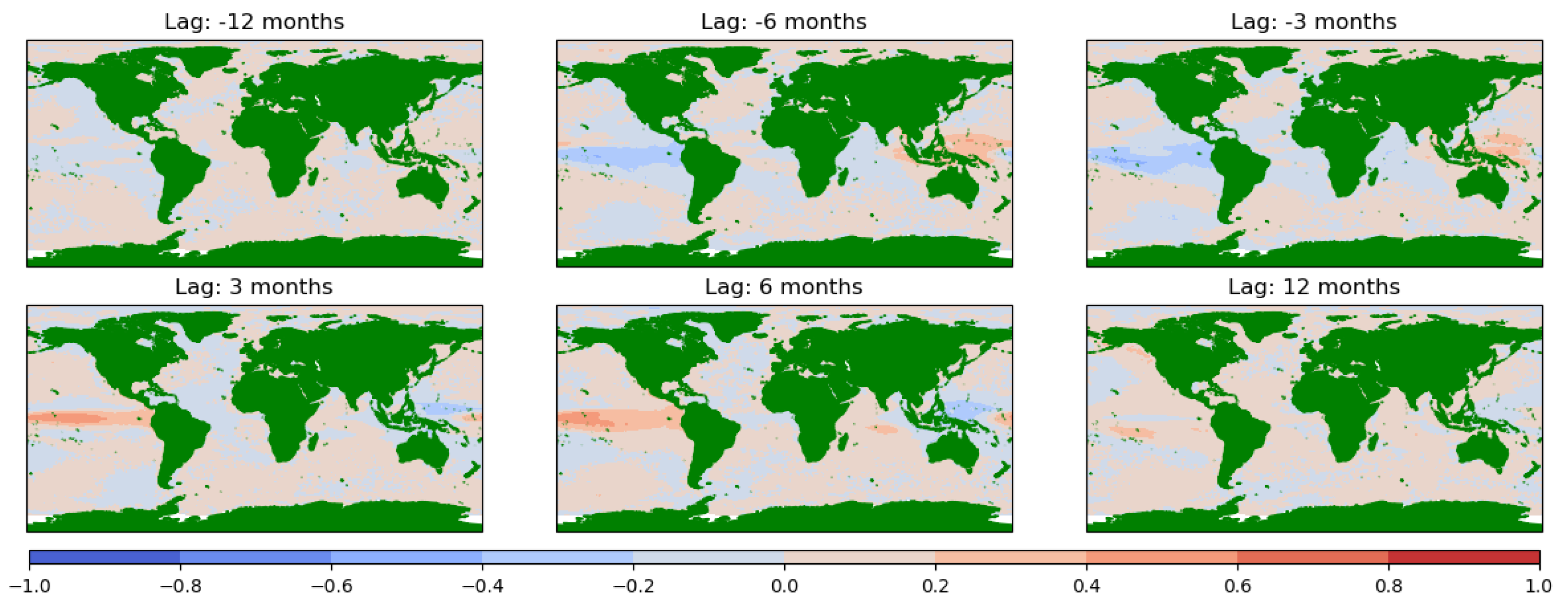

3.1. How Do ENSO Correlations of OHC100, ZAO, MAO, and OHCT Change from ±12 Months Lag Globally at the Mesoscale?

3.2. What Does the Geographic Distribution of Residuals of These Variables Reveal about the Oceanic and Atmospheric Drivers of Change?

4. Discussion

4.1. Which Regions Are ENSO-Dominated, and Which Are Residual-Dominated?

4.2. What Are the Implications for TCs and Other Extreme Weather?

5. Conclusions

- Incorporating analysis of atmospheric variables like surface and upper troposphere temperature and winds from a compatible reanalysis such as ERA5 could provide further insights into how ENSO-like or “residual-like” ocean-driven extreme weather impacts were during the study period—this would inform what these impacts would be like if they continued into the future;

- Confirm the symmetry of OHCT, ZAO, MAO responses to ENSO at various lags—since El Niño phase is known to last longer and have greater intensity than La Niña phase, correlations may disproportionately represent the former, but on the other hand, the correlations are fairly strong, which may support a symmetric response to both phases;

- Further investigation of OHC100 leading SST in correlation with ENSO and vice versa—does this relate to the local direction of forcing between ocean and atmosphere?

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ENSO. | El Niño – Southern Oscillation |

| ITCZ | Intertropical convergence zone |

| MAO | Meridional advection of ocean heat content |

| MDR | Main development region for tropical cyclones |

| MHW | Marine heatwave |

| ONI | Oceanic Niño Index |

| OHC100 | Ocean heat content of the upper 100 meters |

| OHCT | Ocean heat content tendency |

| PI | Tropical cyclone potential intensity |

| PL | Polar low |

| RI | Tropical cyclone rapid intensification |

| SST | Sea surface temperature |

| TC | Tropical cyclone |

| TCHP | Tropical cyclone heat potential |

| WBC | Western boundary current |

| ZAO | Zonal advection of ocean heat content |

References

- Simpson, G. C. G. C. SIMPSON, C.B., F.R.S., ON SOME STUDIES IN TERRESTRIAL RADIATION Vol. 2, No. 16. Published March 1928. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1929, 55, 73–73. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.R.; Van Houtan, K.S. The recent normalization of historical marine heat extremes. PLOS Clim. 2022, 1, e0000007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, M. Decadal changes in radiative fluxes at land and ocean surfaces and their relevance for global warming. WIREs Clim. Change 2016, 7, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvin, K.; et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (Eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/.

- Bolin, B.; Rossby, C.-G. The Atmosphere and the Sea in Motion: Scientific Contributions to the Rossby Memorial Volume. 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.C.; Lyman, J.M. Warming trends increasingly dominate global ocean. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 757–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitus, S.; Antonov, J.I.; Boyer, T.P.; Stephens, C. Warming of the World Ocean. 2000; 287. [Google Scholar]

- Su, H.; Wei, Y.; Lu, W.; Yan, X.-H.; Zhang, H. Unabated Global Ocean Warming Revealed by Ocean Heat Content from Remote Sensing Reconstruction. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Trenberth, K.E.; Fasullo, J.T.; Mayer, M.; Balmaseda, M.; Zhu, J. Evolution of Ocean Heat Content Related to ENSO. J. Clim. 2019, 32, 3529–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, W.; Hu, A.; Meehl, G.A.; Wang, F. Multidecadal Changes of the Upper Indian Ocean Heat Content during 1965–2016. J. Clim. 2018, 31, 7863–7884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotzbach, P.J.; Jones, J.J.; Wood, K.M.; Bell, M.M.; Blake, E.S.; Bowen, S.G.; Caron, L.-P.; Chavas, D.R.; Collins, J.M.; Gibney, E.J.; et al. The 2023 Atlantic Hurricane Season: An Above-Normal Season despite Strong El Niño Conditions. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2024, 105, E1644–E1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Xie, S.-P.; Miyamoto, A.; Deser, C.; Zhang, P.; Luongo, M.T. Strong 2023–2024 El Niño generated by ocean dynamics. Nat. Geosci. 2025, 18, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, M.; Bister, M.; Emanuel, K. Potential Intensity of Tropical Cyclones: Comparison of Results from Radiosonde and Reanalysis Data. J. Clim. 2004, 17, 1722–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; Jing, Z.; Wang, H.; Wu, L.; Chen, Z.; Gan, B.; Yang, H. Oceanic mesoscale eddies as crucial drivers of global marine heatwaves. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.; Leben, R.; Anderson, S.; Haag, A.; Pilley, C. High Frequency Satellite Surveillance of Gulf of Mexico Loop Current Frontal Eddy cyclones. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2009; IEEE: Biloxi, MS, 2009; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Price, J.F. Metrics of hurricane-ocean interaction: vertically-integrated or vertically-averaged ocean temperature? Ocean Sci. 2009, 5, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortum, G.; Vecchi, G.A.; Hsieh, T.-L.; Yang, W. Influence of Weather and Climate on Multidecadal Trends in Atlantic Hurricane Genesis and Tracks. J. Clim. 2024, 37, 1501–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.S.; Walsh, K.J.E.; Camargo, S.J.; Kossin, J.P.; Tory, K.J.; Wehner, M.F.; Chan, J.C.L.; Klotzbach, P.J.; Dowdy, A.J.; Bell, S.S.; et al. Declining tropical cyclone frequency under global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X. Translation speed slowdown and poleward migration of western North Pacific tropical cyclones. Npj Clim. Atmospheric Sci. 2024, 7, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, S.; Toumi, R.; Song, X.; Wang, Q. Recent increases in tropical cyclone rapid intensification events in global offshore regions. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkin, H.; Holland, G.J.; Holbrook, N.; Henderson-Sellers, A. An Evaluation of Thermodynamic Estimates of Climatological Maximum Potential Tropical Cyclone Intensity. Mon. Weather Rev. 2000, 128, 746–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bister, M.; Emanuel, K.A. Low frequency variability of tropical cyclone potential intensity 1. Interannual to interdecadal variability. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 2002, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bister, M.; Emanuel, K.A. Low frequency variability of tropical cyclone potential intensity 2. Climatology for 1982–1995. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 2002, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguru, K.; Foltz, G.R.; Leung, L.R.; Asaro, E.D.; Emanuel, K.A.; Liu, H.; Zedler, S.E. Dynamic Potential Intensity: An improved representation of the ocean’s impact on tropical cyclones. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 6739–6746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilford, D.M.; Solomon, S.; Emanuel, K.A. On the Seasonal Cycles of Tropical Cyclone Potential Intensity. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 6085–6096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilford, D.M. pyPI (v1.3): Tropical Cyclone Potential Intensity Calculations in Python, 2020. Available online: https://gmd.copernicus.org/preprints/gmd-2020-279/gmd-2020-279.pdf.

- Holland, G.J. The Maximum Potential Intensity of Tropical Cyclones. J. Atmospheric Sci. 1997, 54, 2519–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieu, C. Hurricane maximum potential intensity equilibrium: Hurricane MPI Equilibrium. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 141, 2471–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.-I.; Black, P.; Price, J.F.; Yang, C. -Y.; Chen, S.S.; Lien, C. -C.; Harr, P.; Chi, N. -H.; Wu, C. -C.; D’Asaro, E.A. An ocean coupling potential intensity index for tropical cyclones. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 1878–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarieva, A.M.; Gorshkov, V.G.; Nefiodov, A.V.; Chikunov, A.V.; Sheil, D.; Nobre, A.D.; Nobre, P.; Li, B.-L. Hurricane’s maximum potential intensity and surface heat fluxes. Preprint 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau-Rizzi, R.; Merlis, T.M.; Jeevanjee, N. The Connection between Carnot and CAPE Formulations of TC Potential Intensity. J. Clim. 2022, 35, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, S.M.; Miles, T.N.; Seroka, G.N.; Xu, Y.; Forney, R.K.; Yu, F.; Roarty, H.; Schofield, O.; Kohut, J. Stratified coastal ocean interactions with tropical cyclones. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.D.; Leben, R.R.; Pilley, C.T.; Shannon, M.; Herndon, D.C.; Pun, I.; Lin, I. -I.; Gentemann, C.L. Slow translation speed causes rapid collapse of northeast Pacific Hurricane Kenneth over cold core eddy. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 7595–7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramer, L.J.; Zhang, J.A.; Alaka, G.; Hazelton, A.; Gopalakrishnan, S. Coastal Downwelling Intensifies Landfalling Hurricanes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL096630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-C.; Lee, C.-Y.; Lin, I.-I. The Effect of the Ocean Eddy on Tropical Cyclone Intensity. J. Atmospheric Sci. 2007, 64, 3562–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaimes, B.; Shay, L.K.; Uhlhorn, E.W. Enthalpy and Momentum Fluxes during Hurricane Earl Relative to Underlying Ocean Features. Mon. Weather Rev. 2015, 143, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, H.; Drennan, W.M.; Graber, H.C. Upper ocean cooling and air-sea fluxes under typhoons: A case study. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2017, 122, 7237–7252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, H.; DiMarco, S.F.; Knap, A.H. Tropical Cyclone Heat Potential and the Rapid Intensification of Hurricane Harvey in the Texas Bight. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2019, 124, 2440–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, H.; Rudzin, J.E. Upper-Ocean Temperature Variability in the Gulf of Mexico with Implications for Hurricane Intensity. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2021, 51, 3149–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, A.; Usui, N. Importance of tropical cyclone heat potential for tropical cyclone intensity and intensification in the Western North Pacific. J. Oceanogr. 2007, 63, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, R.; Feng, X. Dominant Role of the Ocean Mixed Layer Depth in the Increased Proportion of Intense Typhoons During 1980–2015. Earths Future 2018, 6, 1518–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, M.; Singh, V.K.; Ganadhi, M.K.; Roxy, M.K.; Emmanuel, R.; Kumar, U. Changing status of tropical cyclones over the north Indian Ocean. Clim. Dyn. 2021, 57, 3545–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidya, P.J.; Chatterjee, S.; Ravichandran, M.; Gautham, S.; Nuncio, M.; Murtugudde, R. Intensification of Arabian Sea cyclone genesis potential and its association with Warm Arctic Cold Eurasia pattern. Npj Clim. Atmospheric Sci. 2023, 6, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Newman, M.; Capotondi, A.; Stevenson, S.; Di Lorenzo, E.; Alexander, M.A. An increase in marine heatwaves without significant changes in surface ocean temperature variability. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrtki, K. El Niño—The Dynamic Response of the Equatorial Pacific Oceanto Atmospheric Forcing. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1975, 5, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. A review of ENSO theories. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2018, 5, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. On the ENSO Mechanisms. Adv. Atmospheric Sci. 2001, 18, 674–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewitte, B.; Cibot, C.; Périgaud, C.; An, S.-I.; Terray, L. Interaction between Near-Annual and ENSO Modes in a CGCM Simulation: Role of the Equatorial Background Mean State. J. Clim. 2007, 20, 1035–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Yan, H. Redefined background state in the tropical Pacific resolves the entanglement between the background state and ENSO. Npj Clim. Atmospheric Sci. 2024, 7, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, Y.M.; Ohba, M.; Deser, C.; Ueda, H. A Proposed Mechanism for the Asymmetric Duration of El Niño and La Niña. J. Clim. 2011, 24, 3822–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, G.; Jiang, W.; Long, S.-M.; Lu, B. Asymmetric relationship between ENSO and the tropical Indian Ocean summer SST anomalies. J. Clim. 2021, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penland, C.; Matrosova, L. Studies of El Niño and Interdecadal Variability in Tropical Sea Surface Temperatures Using a Nonnormal Filter. J. Clim. 2006, 19, 5796–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhaden, M.J.; Lee, T.; McClurg, D. El Niño and its relationship to changing background conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, 2011GL048275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M. ; The CMIP Modelling Groups (BMRC (Australia), CCC (Canada), CCSR/NIES (Japan), CERFACS (France), CSIRO (Austraila), MPI (Germany), GFDL (USA), GISS (USA), IAP (China), INM (Russia), LMD (France), MRI (Japan), NCAR (USA), NRL (USA), Hadley Centre (UK) and YNU (South Korea)) El Niño- or La Niña-like climate change? Clim. Dyn. 2005, 24, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, A.; Oberhuber, J.; Bacher, A.; Esch, M.; Latif, M.; Roeckner, E. Increased El NinÄ o frequency in a climate model forced by future greenhouse warming. 1999; 398. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, M.; Feng, M.; Bindoff, N.L.; Phillips, H.E. Local Drivers of Extreme Upper Ocean Marine Heatwaves Assessed Using a Global Ocean Circulation Model. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 788390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rey, M.; Rodríguez-Fonseca, B.; Polo, I. Atlantic opportunities for ENSO prediction. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 6802–6810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Esteve, B.; Domeisen, D.I.V. The Tropospheric Pathway of the ENSO–North Atlantic Teleconnection. J. Clim. 2018, 31, 4563–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Michel, L.; Eric, G.; Romain, B.-B.; Gilles, G.; Angélique, M.; Marie, D.; Clément, B.; Mathieu, H.; Olivier, L.G.; Charly, R.; et al. The Copernicus Global 1/12° Oceanic and Sea Ice GLORYS12 Reanalysis. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 698876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA. Cold & Warm Episodes by Season. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Drévillon, M.; Lellouche, J.-M.; Régnier, C.; Garric, G.; Bricaud, C.; Bourdallé-Badie, R. Approval Date by Quality Assurance Review Group: 23/11/2023. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oldenborgh, G.J.; Hendon, H.; Stockdale, T.; L’Heureux, M.; Coughlan De Perez, E.; Singh, R.; Van Aalst, M. Defining El Niño indices in a warming climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 044003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compo, G.P.; Sardeshmukh, P.D. Removing ENSO-Related Variations from the Climate Record. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1957–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penland, C.; Matrosova, L. Prediction of Tropical Atlantic Sea Surface Temperatures Using Linear Inverse Modeling. J. Clim. 1998, 11, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Leipper, D.F.; Volgenau, D. Hurricane Heat Potential of the Gulf of Mexico. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1972, 2, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipper, D.F. A sequence of current patterns in the Gulf of Mexico. J. Geophys. Res. 1970, 75, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgenau, Douglas. Hurricane heat potential of the Gulf of Mexico; Naval Postgraduate School: Monterey, California, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cione, J.J. The Relative Roles of the Ocean and Atmosphere as Revealed by Buoy Air–Sea Observations in Hurricanes. Mon. Weather Rev. 2015, 143, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Q.; Xue, H.; Qin, H.; Zeng, X.; Peng, S. Features and variability of the South China Sea western boundary current from 1992 to 2011. Ocean Dyn. 2016, 66, 795–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terray, P.; Dominiak, S. Indian Ocean Sea Surface Temperature and El Niño–Southern Oscillation: A New Perspective. J. Clim. 2005, 18, 1351–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, K.E.; Caron, J.M.; Stepaniak, D.P.; Worley, S. Evolution of El Niño–Southern Oscillation and global atmospheric surface temperatures. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 2002, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Q.; Xie, S.; Liu, Z.; Wu, L. Impact of the Indian Ocean SST basin mode on the Asian summer monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, 2006GL028571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Périgaud, C.; Delecluse, P. Annual sea level variations in the southern tropical Indian Ocean from Geosat and shallow-water simulations. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1992, 97, 20169–20178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Xie, S.-P.; Huang, G.; Hu, K. Role of Air–Sea Interaction in the Long Persistence of El Niño–Induced North Indian Ocean Warming*. J. Clim. 2009, 22, 2023–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.-P.; Philander, S.G.H. A coupled ocean-atmosphere model of relevance to the ITCZ in the eastern Pacific. Tellus A 1994, 46, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, K.E.; Fasullo, J.T.; Balmaseda, M.A. Earth’s Energy Imbalance. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 3129–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydbeck, A.V.; Jensen, T.G.; Flatau, M.K. Reciprocity in the Indian Ocean: Intraseasonal Oscillation and Ocean Planetary Waves. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2021, 126, e2021JC017546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhaden, M.J. A 21st century shift in the relationship between ENSO SST and warm water volume anomalies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, 2012GL051826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinen, C.S.; McPhaden, M.J. Observations of Warm Water Volume Changes in the Equatorial Pacific and Their Relationship to El Niño and La Niña. J. Clim. 2000, 13, 3551–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhaden, M.J. Tropical Pacific Ocean heat content variations and ENSO persistence barriers. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 2003GL016872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.; Haimberger, L.; Balmaseda, M.A. On the Energy Exchange between Tropical Ocean Basins Related to ENSO*. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 6393–6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.; Fasullo, J.T.; Trenberth, K.E.; Haimberger, L. ENSO-driven energy budget perturbations in observations and CMIP models. Clim. Dyn. 2016, 47, 4009–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.M.; Kim, K.M. Cooling of the Atlantic by Saharan dust. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, 2007GL031538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Dessler, A.E.; Mahowald, N.M.; Colarco, P.R.; da Silva, A. Long-term variability in Saharan dust transport and its link to North Atlantic sea surface temperature. Geophysical Research Letters 2008, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avellaneda, N.M.; Serra, N.; Minnett, P.J.; Stammer, D. Response of the eastern subtropical Atlantic SST to Saharan dust: A modeling and observational study. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P.W.; Williams, M.; Mote, T. Modeled Atmospheric Optical and Thermodynamic Responses to an Exceptional Trans-Atlantic Dust Outbreak. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 2021, 126, e2020JD032909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.W.; Ramseyer, C. The Relationship Between the Saharan Air Layer, Convective Environmental Conditions, and Precipitation in Puerto Rico. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 2024, 129, e2023JD039681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Cai, W.; Zhang, L.; Nakamura, H.; Timmermann, A.; Joyce, T.; McPhaden, M.J.; Alexander, M.; Qiu, B.; Visbeck, M.; et al. Enhanced warming over the global subtropical western boundary currents. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Jing, Z.; Chang, P.; Liu, X.; Montuoro, R.; Small, R.J.; Bryan, F.O.; Greatbatch, R.J.; Brandt, P.; Wu, D.; et al. Western boundary currents regulated by interaction between ocean eddies and the atmosphere. Nature 2016, 535, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecchi, G.A.; Soden, B.J. Global Warming and the Weakening of the Tropical Circulation. J. Clim. 2007, 20, 4316–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.D.; Black, M.T.; Min, S.; Fischer, E.M.; Mitchell, D.M.; Harrington, L.J.; Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S.E. Emergence of heat extremes attributable to anthropogenic influences. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 3438–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, K. Effect of Upper-Ocean Evolution on Projected Trends in Tropical Cyclone Activity. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 8165–8170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Lin, I.-I.; Chou, C.; Huang, R.-H. Change in ocean subsurface environment to suppress tropical cyclone intensification under global warming. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, A.V. Ocean Response to Wind Variations, Warm Water Volume, and Simple Models of ENSO in the Low-Frequency Approximation. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 3855–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.-I.; Chen, C.; Pun, I.; Liu, W.T.; Wu, C. Warm ocean anomaly, air sea fluxes, and the rapid intensification of tropical cyclone Nargis (2008). Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, 2008GL035815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.; Camargo, S.J.; Patricola, C.M.; Boucharel, J.; Chand, S.; Klotzbach, P.; Chan, J.C.L.; Wang, B.; Chang, P.; Li, T.; et al. ENSO and Tropical Cyclones. In Geophysical Monograph Series; McPhaden, M.J., Santoso, A., Cai, W., Eds.; Wiley, 2020; pp. 377–408. ISBN 978-1-119-54812-6. [Google Scholar]

- Shay, L.K.; Brewster, J.K. Oceanic Heat Content Variability in the Eastern Pacific Ocean for Hurricane Intensity Forecasting. Mon. Weather Rev. 2010, 138, 2110–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.-F.; Boucharel, J.; Lin, I.-I. Eastern Pacific tropical cyclones intensified by El Niño delivery of subsurface ocean heat. Nature 2014, 516, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglietta, M.M.; Rotunno, R. Development mechanisms for Mediterranean tropical-like cyclones (medicanes). Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 145, 1444–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacox, M.G.; Alexander, M.A.; Amaya, D.; Becker, E.; Bograd, S.J.; Brodie, S.; Hazen, E.L.; Pozo Buil, M.; Tommasi, D. Global seasonal forecasts of marine heatwaves. Nature 2022, 604, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiswell, S.M. Atmospheric wavenumber-4 driven South Pacific marine heat waves and marine cool spells. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radfar, S.; Moftakhari, H.; Moradkhani, H. Rapid intensification of tropical cyclones in the Gulf of Mexico is more likely during marine heatwaves. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, K.A.; Rotunno, R. Polar lows as arctic hurricanes. Tellus A 1989, 41A, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, P.J.; Graversen, R.G.; Noer, G.; Hodges, K. An objective global climatology of polar lows based on reanalysis data. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2018, 144, 2099–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolstad, E.W. A global climatology of favourable conditions for polar lows. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 137, 1749–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Rutgersson, A.; Wu, L. Influence of mesoscale sea surface temperature anomaly on polar lows. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 014051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, B.; Dash, M.K.; Behera, S.K. Global wave number-4 pattern in the southern subtropical sea surface temperature. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).