Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

3. Results and Discussions

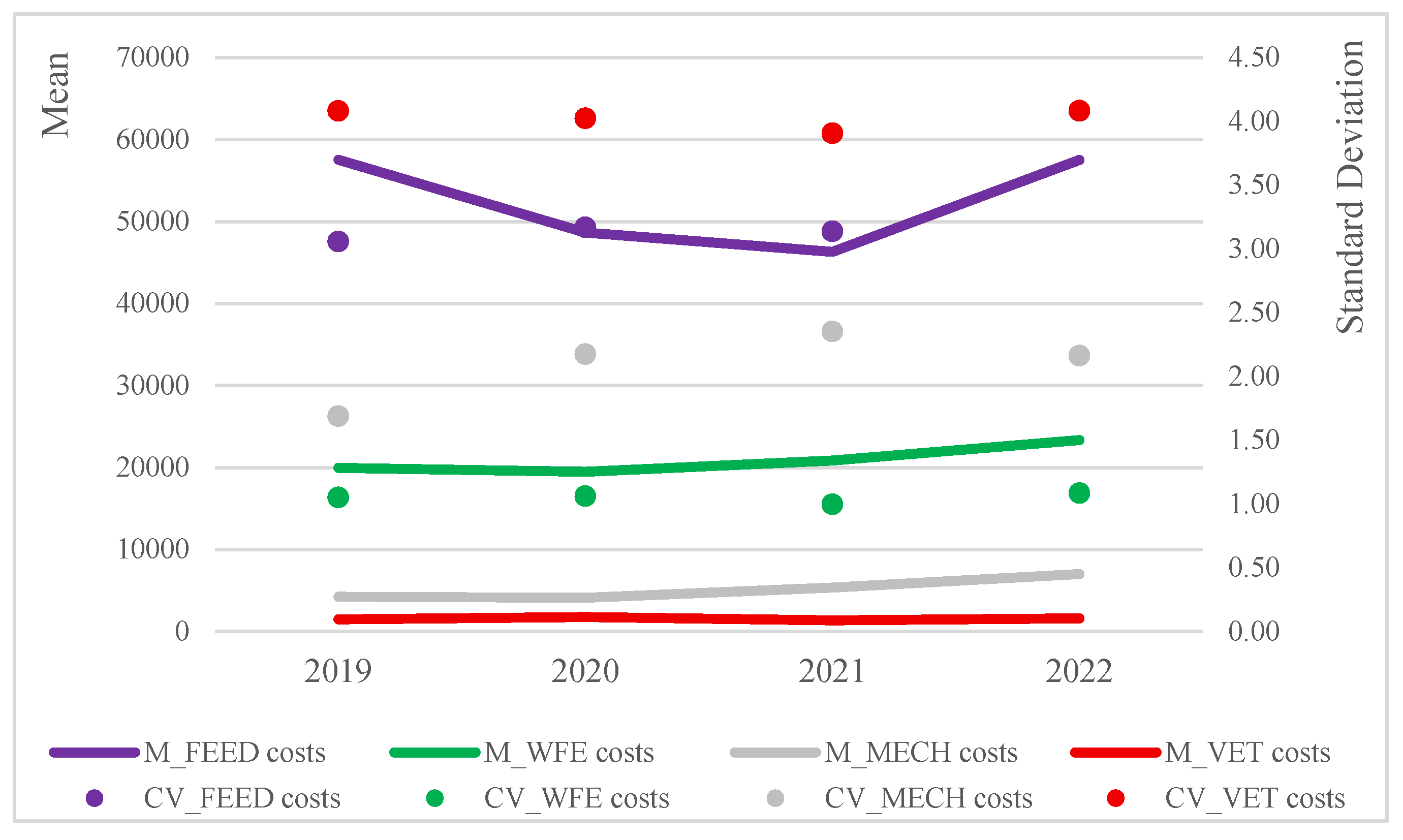

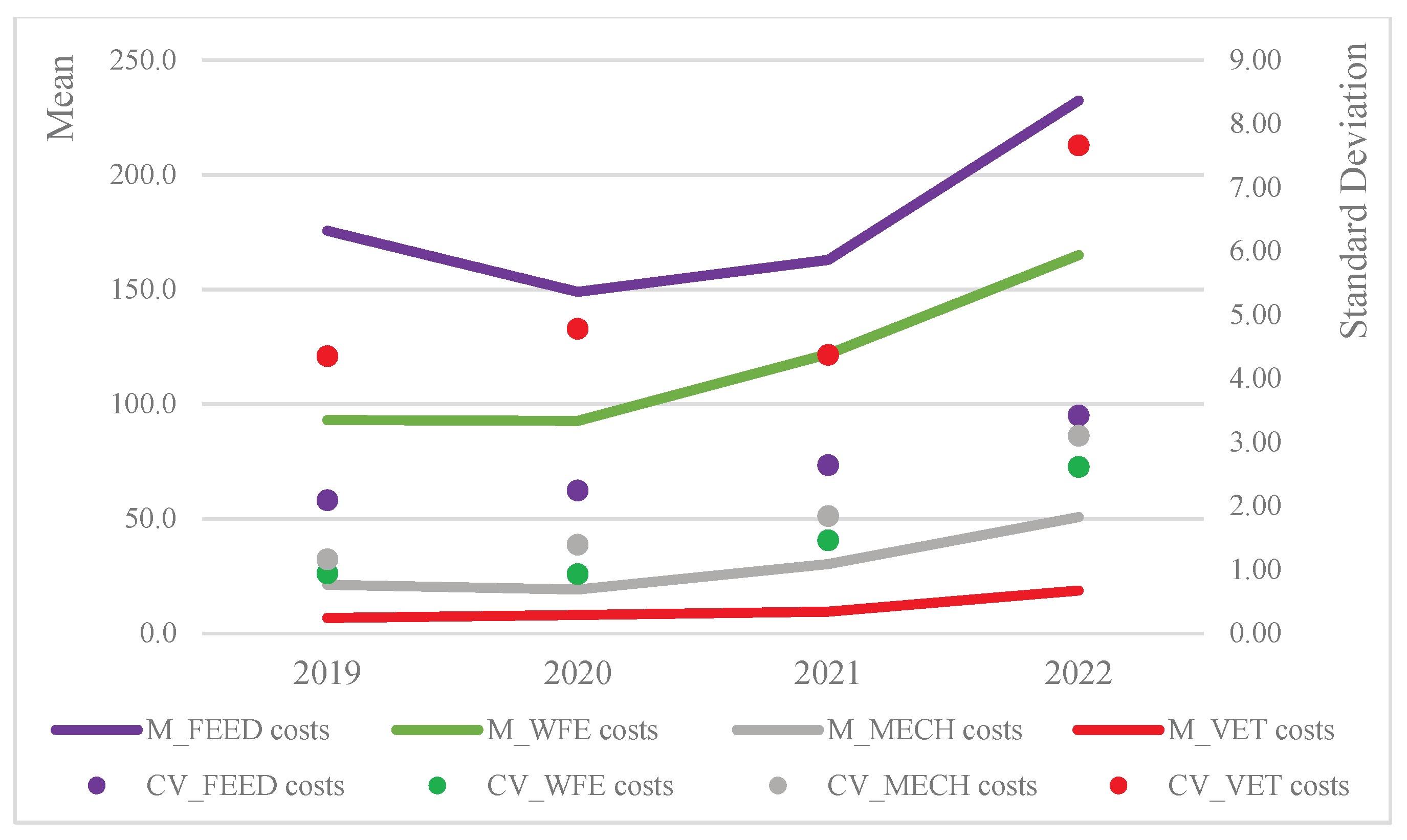

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics of Italian Poultry Farms

3.2. The Technical Efficiency of Livestock Farms: Results of the Econometric Analysis

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Global |

| 0.803 | 0.806 | 0.803 | 0.793 | 0.801 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DEA | Data Envelopment Analysis |

| FADN | Farm Accountancy Data Network |

| SFA | Stochastic Frontier Analysis |

| TE | Technical Efficiency |

| TEO | Technical-Economic Orientation |

References

- FAO. Poultry meat production. Our World in Data, 2025. https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20250624-125417/grapher/poultry-production-tonnes.html.

- OECD/FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025-2034, OECD Publishing: Paris, 2025. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-fao-agricultural-outlook-2025-2034_601276cd-en.html.

- European Commission. Market Situation for Poultry. European Union, Bruxelles, 2024. https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/a/cdd4ea97-73c6-4dce-9b01-ec4fdf4027f9/24.08.2017-Poultry.pptfinal.pdf.

- ISMEA. Avicoli e uova. Rome, Italy, 2024. https://www.ismeamercati.it/flex/files/1/a/9/D.b92cb4fbf6d7d5bd7ee2/SchedaAvicoli_2024.pdf.

- Attia, Y.A.; Rahman, M.T.; Hossain, M.J.; Basiouni, S.; Khafaga, A.F.; Shehata, A.A.; Hafez, H.M. Poultry production and sustainability in developing countries under the COVID-19 crisis: Lessons learned. Animals 2022, 12, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.; Golaviya, A.; Panchal, K.; Hinsu, A.; Yadav, K.; Fournié, G.; …; Dasgupta, R. Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 and the Associated Lockdown on the Production, Distribution, and Consumption of Poultry Products in Gujarat, India: A Qualitative Study, Poultry 2023, 2, 395–410. [CrossRef]

- Emrouznejad, A.; Cabanda, E. Introduction to Data Envelopment Analysis and its Applications. In Osman, I.; Anouze, A.; Emrouznejad A. (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Strategic Performance Management and Measurement Using Data Envelopment Analysis. IGI Global Scientific Publishing. 2015, pp. 235-255. [CrossRef]

- Ruzhani, F.; Mushunje, A. Technical efficiency in agriculture: A decade-long meta-analysis of global research, J. Agric. Food Res., 2025, 19, 01667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, K.; Venkataramani, A. Technical Efficiency in Agricultural Production and Its Determinants: An Exploratory Study at the District Level. Indian J. Agr. Econ. 2006, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Trentin, A.; Talamini, D.J.D.; Coldebella, A.; Pedroso, A.C.; Gomes, T.M.A. Technical and economic performance favours fully automated climate control broiler housing. Br. Poult. Sci. 2025, 66, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Workneh, W.M.; Kumar, R. The technical efficiency of large-scale agricultural investment in Northwest Ethiopia: A stochastic frontier approach, Heliyon 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Manevska-Tasevska, G.; Hansson, H.; Labajova, K. Impact of Management Practices on Persistent and Residual Technical Efficiency – a Study of Swedish pig farming. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2017, 38, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radlińska, K. Some Theoretical and Practical Aspects of Technical Efficiency—The Example of European Union Agriculture. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopler, I.; Marchaim, U.; Tikász, I. E.; Opaliński, S.; Kokin, E.; Mallinger, K. .; Banhazi, T. Farmers’ perspectives of the benefits and risks in precision livestock farming in the EU pig and poultry sectors. Animals 2023, 13, 2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasniqi, N.; Blancard, S.; Gjokaj, E.; Aalmo, G.O. Modelling technical efficiency of horticulture farming in Kosovo: An application of data envelopment analysis. Bio-based Appl. Ec. 2023, 12, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, R.; Haryanto, T.; Sari, D.W. Technical efficiency among agricultural households and determinants of food security in East Java, Indonesia. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhehibi, B.; Souissi, A.; Frija, A.; Fouzai, A.; Idoudi, Z.; Abdeladhim, M.; Devkota, M.; Rekik, M. Assessing technical efficiency of crop–livestock systems under conservation agriculture: exploring the potential for sustainable system transformation in Tunisia. Managem & Sustainab: An Arab Review 2025. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Ali, M.; Ahmad, N.; Abid, M.A.; Kusch-Brandt, S. Technical Efficiency. Analysis of Layer and Broiler Poultry Farmers in Pakistan. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ali, S.; Riaz, B. Estimation of Technical Efficiency of Open Shed Broiler Farmers in Punjab, Pakistan: A Stochastic Frontier Analysis. J. Econ. Sust. Dev. 2014, 5, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rokhani, M.R.; Kuntadi, E.B.; Suwandari, A.; Yanuarti, R.; Khasan, A.F.; Mori, Y.; Kondo, T. Impact of Contract Farming on the Technical Efficiency of Broiler Farmers in Indonesia. Food Ec. 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaszyńska-Skwirzyńska, M.; Konieczka, P.; Bucław, M.; Majewska, D.; Pietruszka, A.; Zych, S.; Szczerbińska, D. Analysis of the Production and Economic Indicators of Broiler Chicken Rearing in 2020–2023: A Case Study of a Polish Farm. Agriculture 2025, 15, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcu, A.; Vacaru-Opri¸s, I.; Dumitrescu, G.; Ciochină, L.P.; Marcu, A.; Nicula, M.; Pe¸t, I.; Dronca, D.; Kelciov, B.; Mari¸s, C. The influence of genetics on economic efficiency of broiler chickens growth. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 46, 339–346. [Google Scholar]

- Karaman, S.; Taşcıoğlu, Y.; Bulut, O.D. Profitability and Cost Analysis for Contract Broiler Production in Turkey. Animals 2023, 13, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarmołowicz,W.; Ziebakowski, L. Labor costs and their Conditions in Poland and the European Union. A Comparative Perspective. Stud. Prawno-Ekon. 2018, 107, 281–303. [CrossRef]

- Benoit, M.; Veysset, P. Livestock unit calculation: a method based on energy needs to refine the study of livestock farming systems. INRAE Prod. Anim. 2021, 34, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arata, L.; Chakrabarti, A.; Ekane, N.; Foged, H.L.; Pahmeyer, C.; Rosemarin, A.; Sckokai, P. Assessment of environmental and farm business impacts of phosphorus policies in two European regions. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latruffe, L.; Balcombe, K.; Davidova, S.; Zawalinska, K. Determinants of Technical Efficiency of Crop and Livestock Farms in Poland. Appl. Econ 2004, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, I. Estimation of technical efficiency of broiler production in Peninsular Malaysia: A stochastic frontier analysis. J. Bus. Manag. Account. 2012, 2, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewumi, A.; Agidigbo, K.O.; Arowolo, K.O. Profit efficiency of poultry farmers in Irepodun local government area of Kwara state, Nigeria. J. Agripreneurship Sust. Dev. 2022, 5, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szőllősi, L.; Béres, E.; Szűcs, I. Effects of modern technology on broiler chicken performance and economic indicators – a Hungarian case study. It. J. Animal Sc. 2021, 20, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Nasrullah, M.; Jiang, B.; Li, X.; Bao, J. A survey of broiler farmers’ perceptions of animal welfare and their technical efficiency: A case study in northeast China. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2022, 25, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myeki, L.W.; Nengovhela, N.B.; Mudau, L.; Nakana, E.; Ngqangweni, S. Estimation of technical, allocative, and economic efficiencies for smallholder broiler producers in South Africa. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmelstein, S.; Costa, I.P.D.A.; Terra, A.V.; Silva, R.F.D.; Capela, G.P.D.O.; Moreira, M.Â.L. .; Santos, M.D. Advancing efficiency sustainability in poultry farms through data envelopment analysis in a Brazilian production system. Animals 2024, 14, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aigner, D.; Lovell, C.K.; Schmidt, P. Formulation and estimation of stochastic frontier production function models. J. Econometr. 1977, 6, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battese, G.E.; Coelli, T.J. A model for technical inefficiency effects in a stochastic frontier production function for panel data. Empir. Ec. 1995, 20, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. Automated tracking systems for the assessment of farmed poultry. Animals 2022, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natsir, M.H.; Mahmudy, W.F.; Tono, M.; Nuningtyas, Y.F. Advancements in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Poultry Farming: Applications, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Smart Agr. Techn. 2025, 12, 101307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Y.S; Ansari, M.I.; Gharieb, R.; Ghosh, S.; Kumar Chaudhary, R.; Gomaa Hemida, M.; Torabian, D. , Rahmani, F., Ahmadi, H., Hajipour, P., Salajegheh Tazerji, S., 2024. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Agricultural, Livestock, Poultry and Fish Sectors. Vet. Med. Int. 2024, 1, 5540056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belarmino, L.C.; Pabsdorf, M.N.; Padula, A.D. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Production Costs and Competitiveness of the Brazilian Chicken Meat Chain. Economies 2023, 11, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Xue, X.; Riffat, S. Cost Effectiveness of Poultry Production by Sustainable and Renewable Energy Source. In Meat and Nutrition Chhabi Lal Ranabhat (Ed.), Intechopen 2021. [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A.; Himu, H.A. Global impact of COVID-19 on the sustainability of livestock production. Global Sust. Res. 2023, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.M.M.; Hossain, M.J.; Rana, M.S. Livestock and Poultry Rearing by Smallholder Farmers in Haor Areas in Bangladesh. Impact on Food Security and Poverty Alleviation. Bangladesh J. Agr. Econ. 2020, 41, 73–86. [Google Scholar]

| Item | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||||

| Mean | Coeff. Variation | Mean | Coeff. Variation | Mean | Coeff. Variation | Mean | Coeff. Variation | |

| LivU | 495.1 | 1.9 | 462.6 | 1.9 | 507.8 | 1.9 | 452.4 | 1.9 |

| LabU | 2.6 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 1.1 |

| FLU | 1.7 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 0.5 |

| UAA | 12.4 | 2.0 | 12.6 | 2.0 | 12.7 | 2.0 | 13.2 | 2.1 |

| VoP (€) | 149535.8 | 3.1 | 148266.8 | 3.3 | 147995.2 | 3.4 | 175240.1 | 3.7 |

| CurC (€) | 138555.6 | 2.2 | 132070.0 | 2.2 | 139736.4 | 2.2 | 174113.7 | 2.8 |

| ESC (€) | 9158.6 | 3.2 | 10252.4 | 3.0 | 9129.7 | 3.4 | 7147.8 | 1.9 |

| CapC (€) | 15291.9 | 1.3 | 14107.4 | 1.1 | 12850.8 | 1.1 | 12255.0 | 1.2 |

| Item | Estimate | Std. Error | z value | Pr(>|z|) | Signif. |

| (Intercept) | 5.128 | 0.201 | 25.478 | < 0.001 | *** |

| log(CurC) | 0.643 | 0.018 | 35.618 | < 0.001 | *** |

| log(ESC) | -0.010 | 0.008 | -1.162 | 0.245 | |

| log(CapC) | 0.021 | 0.007 | 3.064 | 0.002 | ** |

| Z_(Intercept) | 1.401 | 0.214 | 6.543 | 0.000 | *** |

| Z_LabU | -0.388 | 0.150 | -2.584 | 0.010 | ** |

| Z_LivU | -0.001 | 0.001 | -2.824 | 0.005 | ** |

| Z_UAA | -0.049 | 0.029 | -1.709 | 0.087 | . |

| Z_TEO_PMeat | -0.295 | 0.117 | -2.510 | 0.012 | * |

| sigmaSq | 0.219 | 0.037 | 5.930 | 0.000 | *** |

| alpha | 0.564 | 0.086 | 6.572 | 0.000 | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).