Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Equipment

2.3. Synthesis and Coating Procedure

2.4. Electrochemical characterization

3. Results

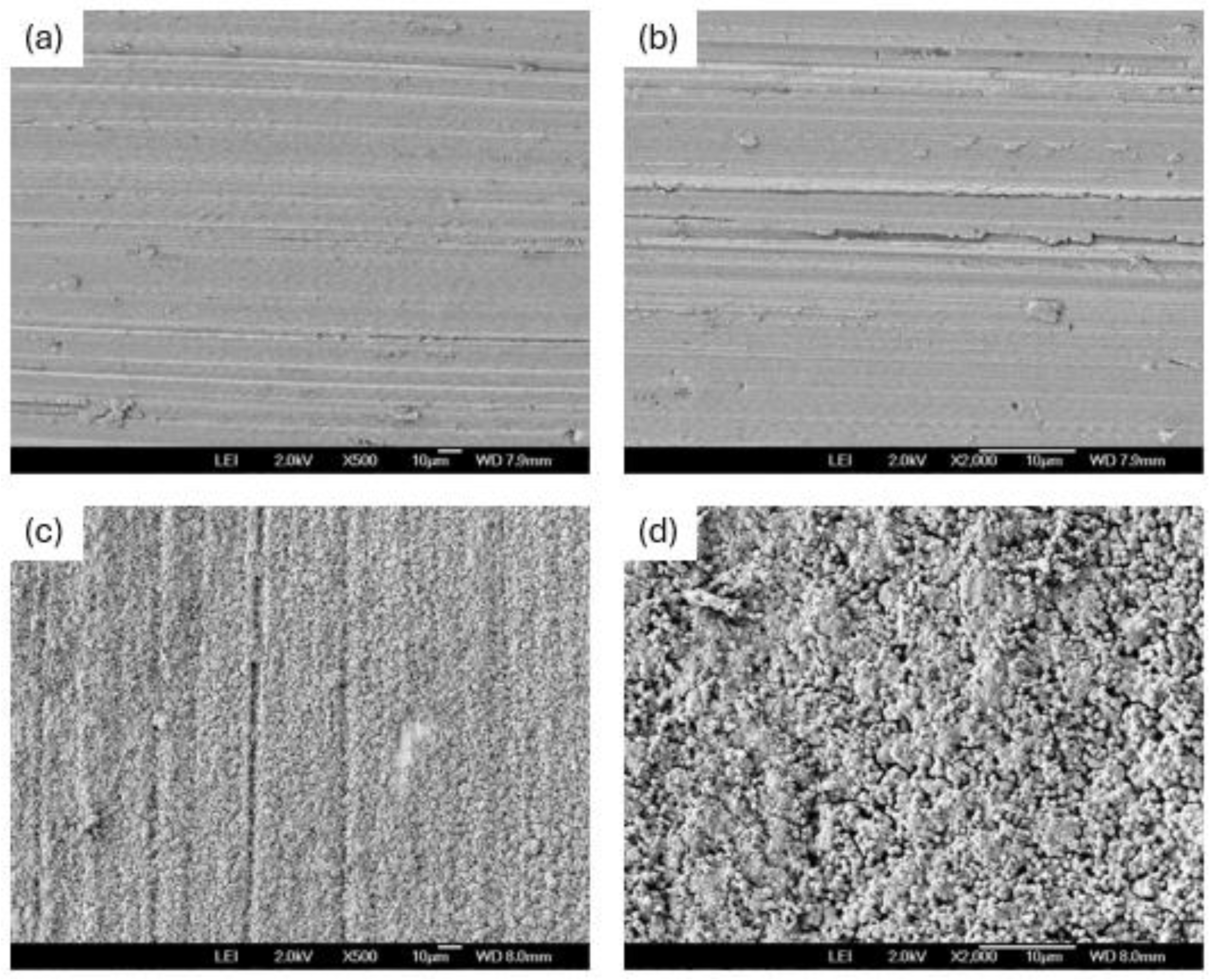

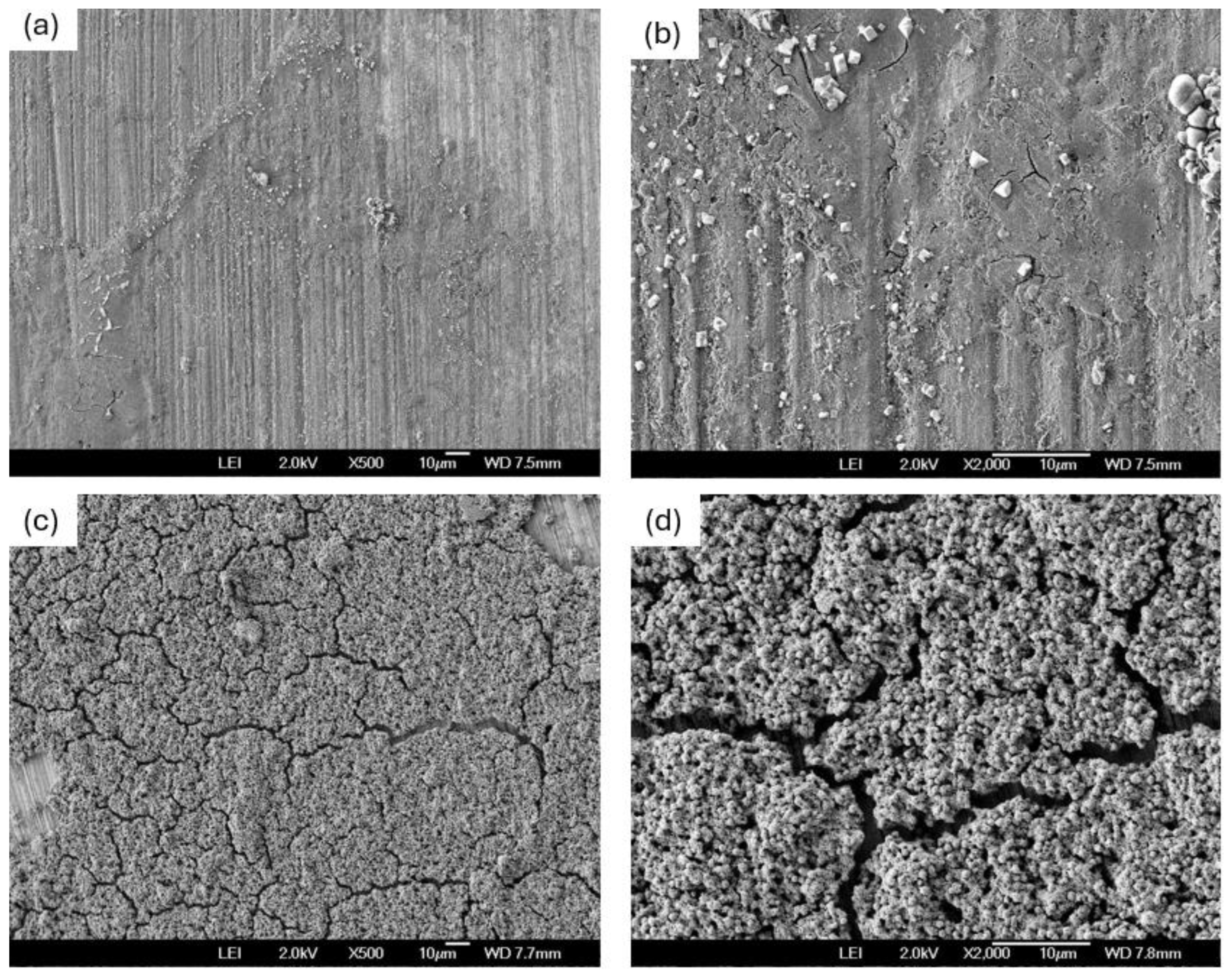

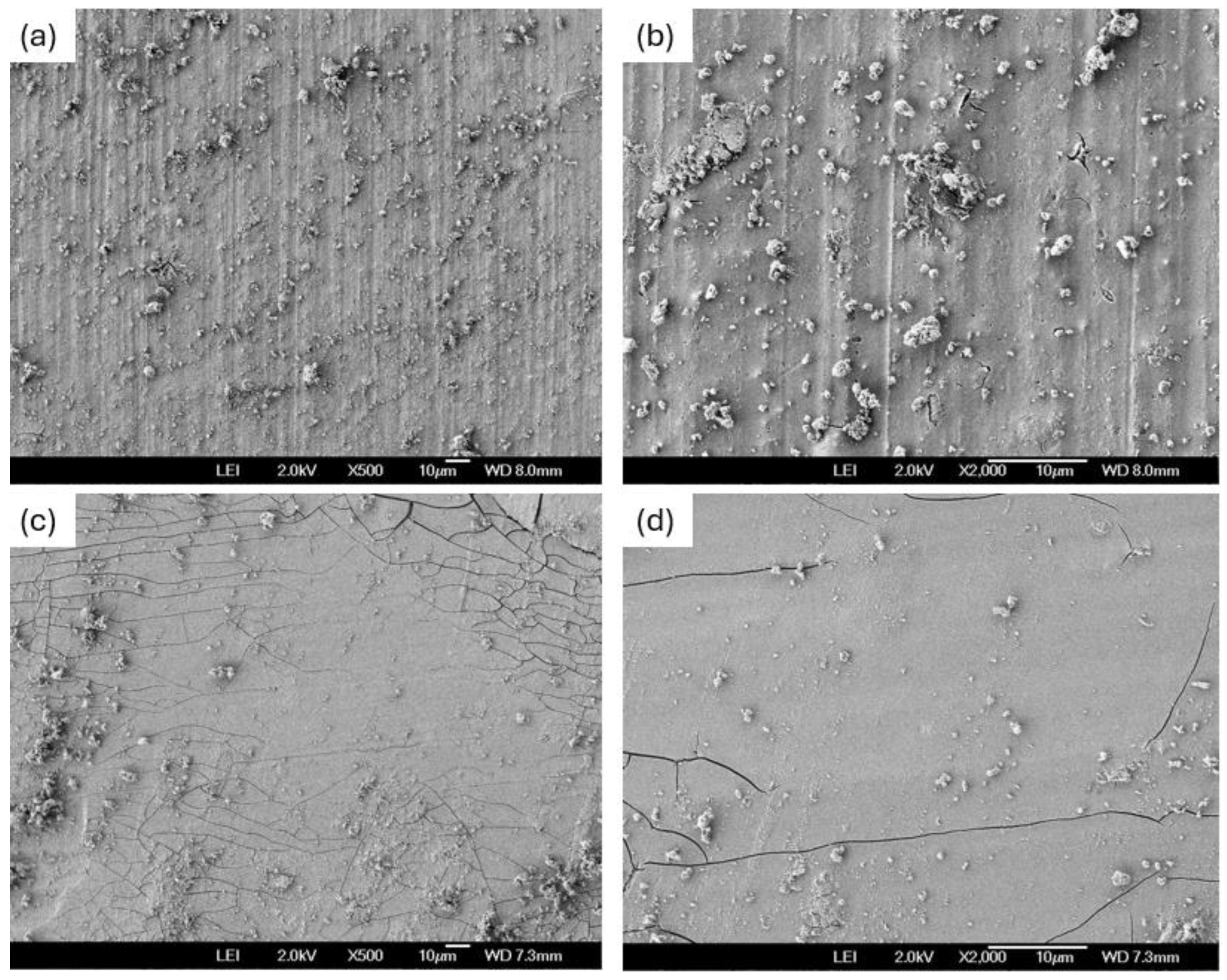

3.1. SEM Before Corrosion

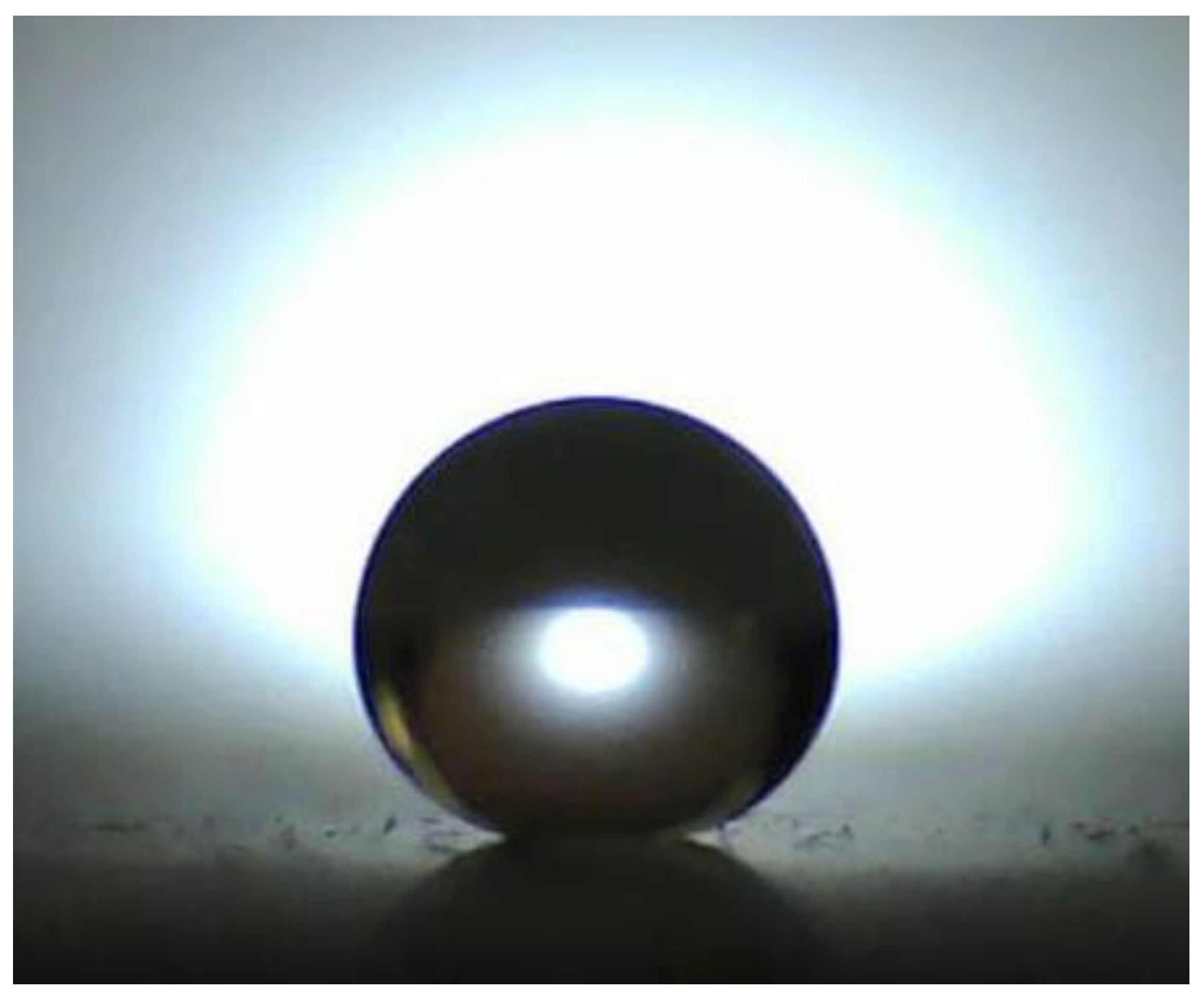

3.2. Wettability Test

3.3. Electrochemical Test

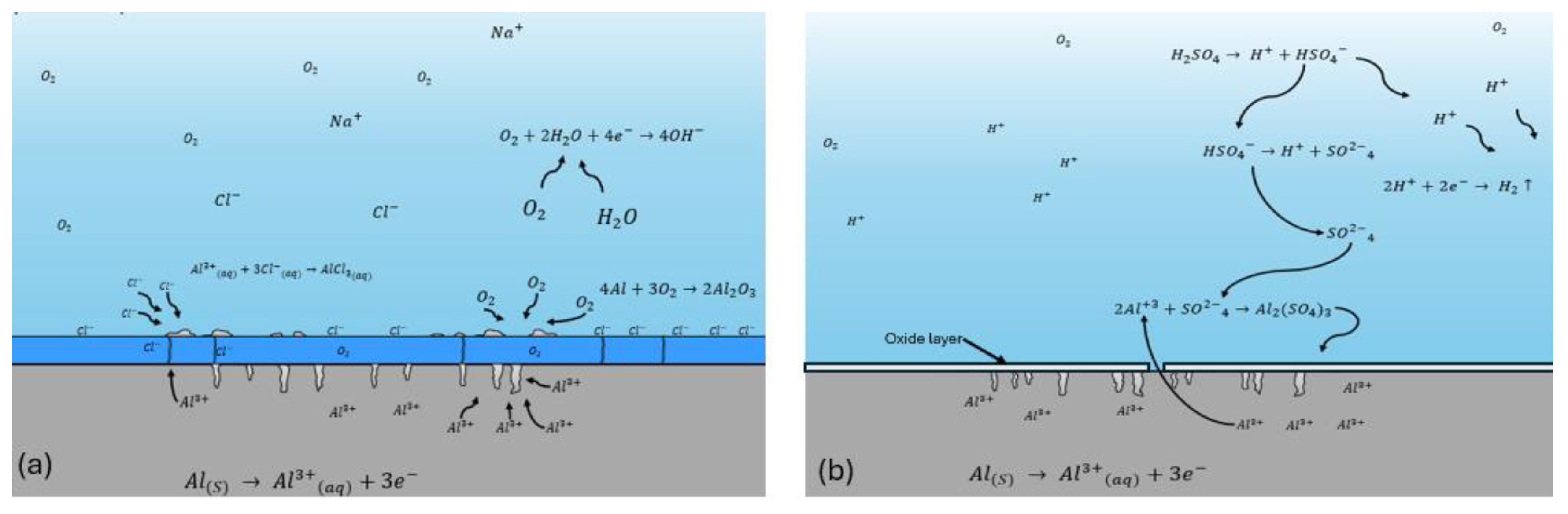

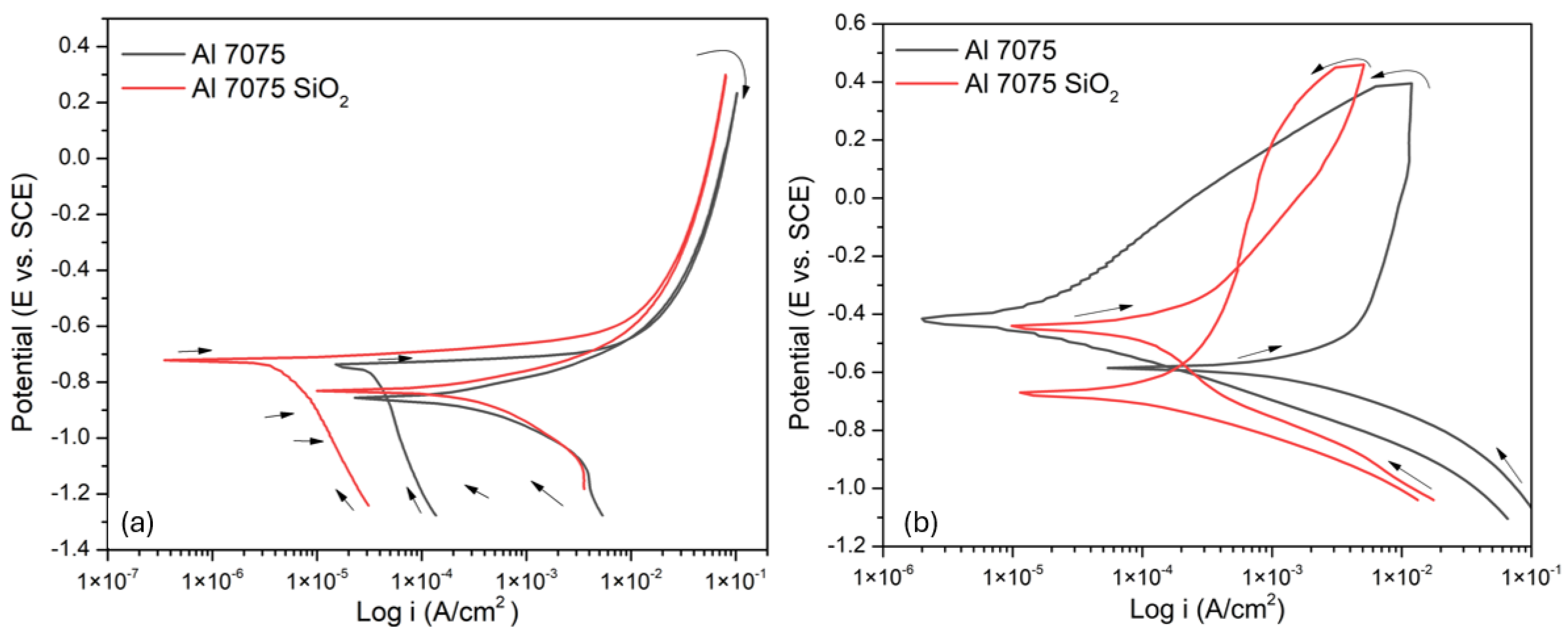

3.3.1. Cyclic Potentiodynamic Polarization

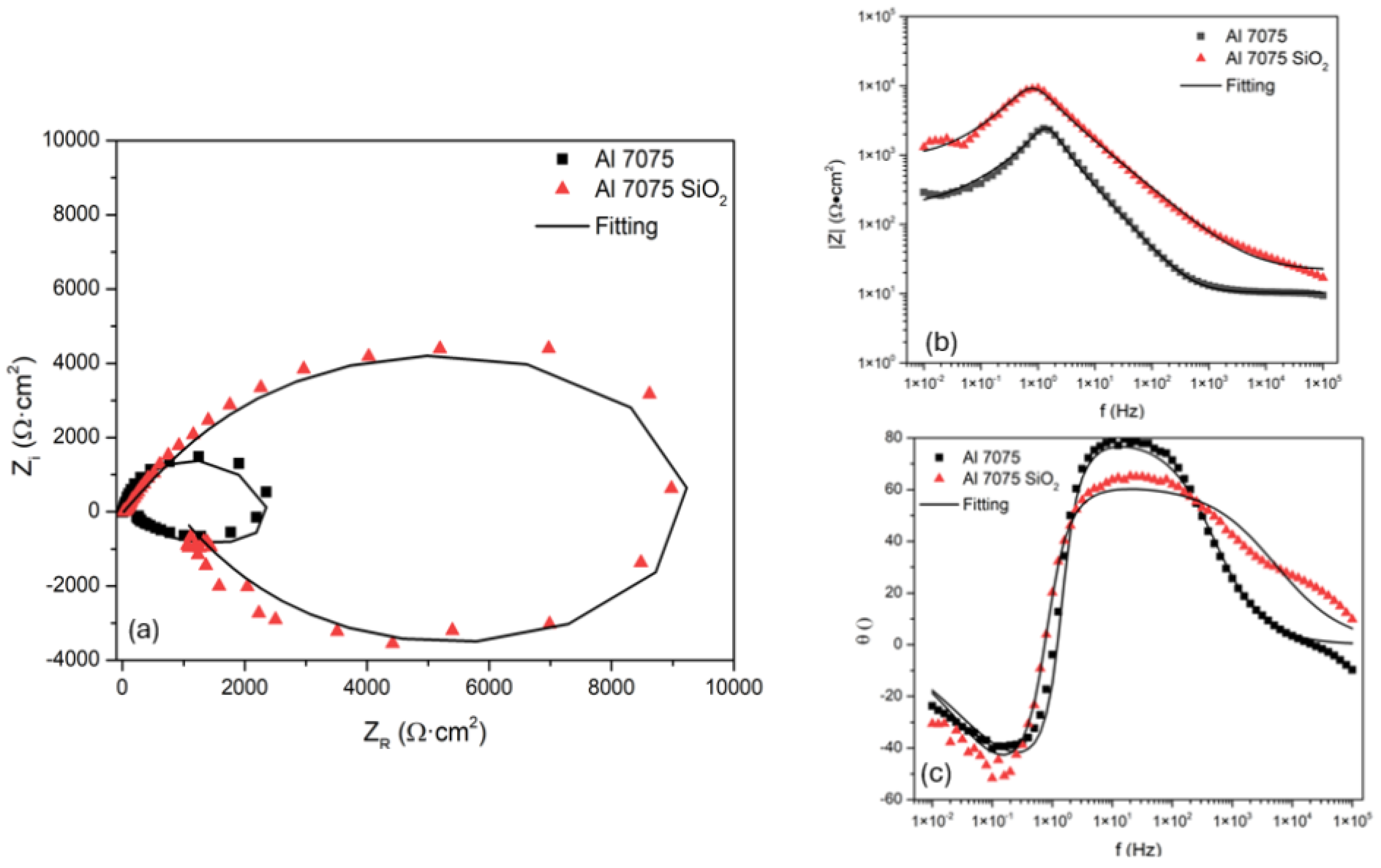

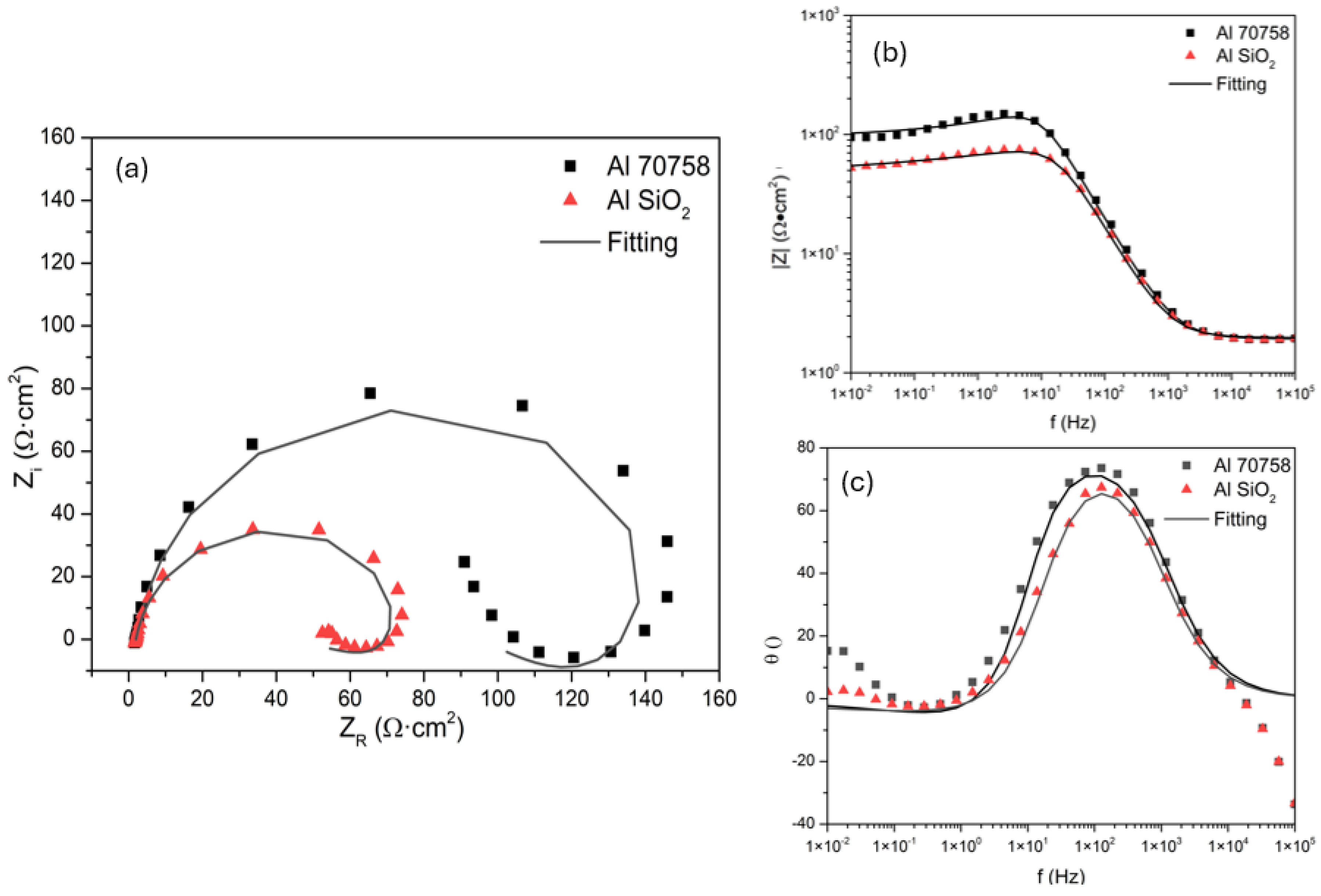

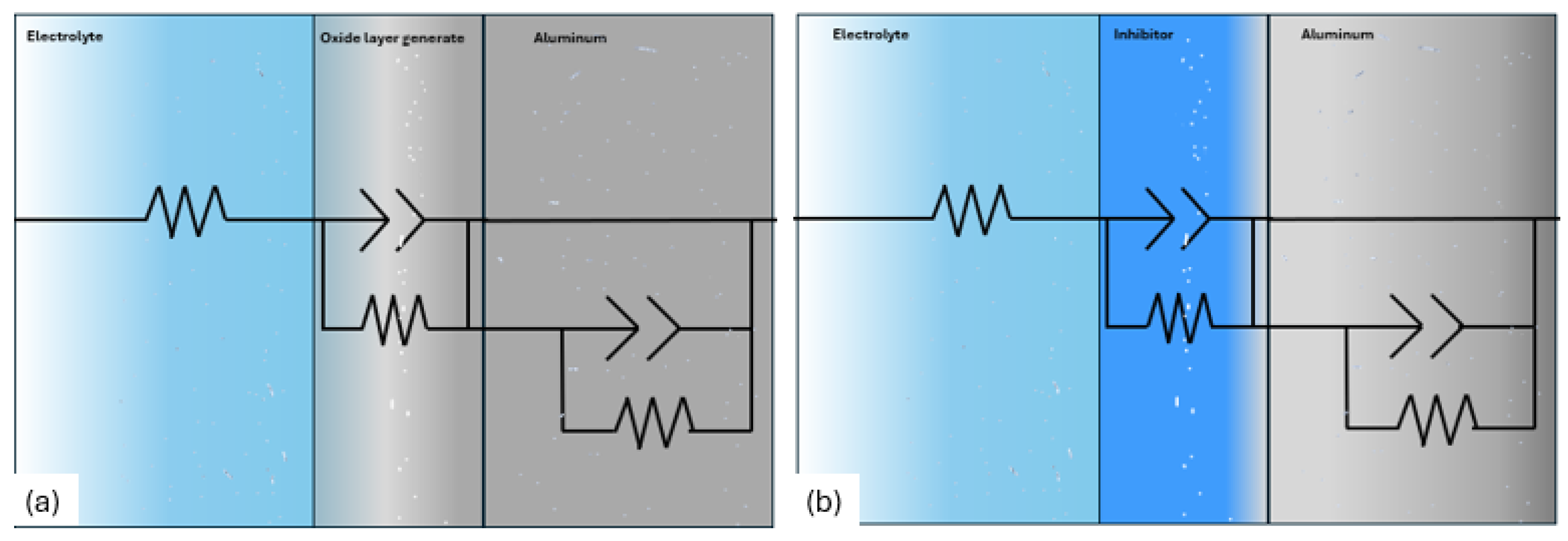

3.3.1. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

| Sample | Rs (Ω·cm2) | CPE1-T (F/cm2) | n | Rct (Ω·cm2) | CPE2-T (F/cm2) | n | RC (Ω·cm2) | IE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl | ||||||||

| Al 7075 | 21.3 | 3.6×10-5 | 0.68698 | 874 | 3.42×10-4 | -0.70 | 1.04×103 | - |

| Al 7075 SiO2 | 10.35 | 6.6×10-5 | 0.9036 | 177 | 2.09×10-3 | -0.68 | 1.01×104 | 81.37 |

| H2SO4 | ||||||||

| Al 7075 | 1.928 | 1.1×10-4 | 0.9386 | 99 | 0.066 | -0.87 | 52.95 | - |

| Al 7075 SiO2 | 1.985 | 1.5×10-4 | 0.92533 | 52 | 0.11 | -0.76 | 22.91 | -102 |

3.4. SEM After Corrosion Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The coating of SiO2 presented a hierarchical structure, with a heterogeneous distribution, nearly homogeneous; however, it presented crack zones that helped as a corrosion concentrator.

- Samples coated with superhydrophobic coatings showed a reduction in corrosion rate obtained by CPP, indicating that the coating protects the material.

- The Al 7075 coated with SiO2 presented localized corrosion when exposed to NaCl. Cl- ions attack on the cracking zone. On the other hand, the H2SO4 coating presented a uniform corrosion due to the dissolution of the coating in this medium.

- The inhibitor efficiency in NaCl is 81%, indicating higher corrosion resistance. Also, the Rct value of Al 7075 coated by SiO2 exposed to H2SO4 is 70% lower than the Rct in NaCl; therefore, this coating can be employed in marine atmospheres.

- The behavior of Al 7075 coated with SiO2 presented an inductive behavior, indicating that adsorption phenomena are occurring on the surface. This is the natural aluminum behavior, and the coating did not change it.

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Liu, M.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Yergin, M. Corrosion Avoidance in Lightweight Materials for Automotive Applications. npj Mater. Degrad. 2018, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukkum, V.B.; Christudasjustus, J.; Darwish, A.A.; Storck, S.M.; Gupta, R.K. Enhanced Corrosion Resistance of Additively Manufactured Stainless Steel by Modification of Feedstock. npj Mater. Degrad. 2022, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, B.H.; Park, J.; Jeon, J.; Heo, S. bo; Chung, W. Effect of Cooling Rate after Heat Treatment on Pitting Corrosion of Super Duplex Stainless Steel UNS S 32750. Anti-Corrosion Methods Mater. 2018, 65, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, J. OVERVIEW ON CORROSION IN AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY AND THERMAL POWER PLANT. Proc. Eng. Sci. 2022, 4, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.Z.; Qi, W.C.; Zeng, R.C.; Chen, X.B.; Gu, C.D.; Guan, S.K.; Zheng, Y.F. Advances in Coatings on Biodegradable Magnesium Alloys. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2020, 8, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, N.; Ueda, N.; Okamoto, A.; Sone, T.; Tsujikawa, M.; Oki, S. DLC Coating on Mg–Li Alloy. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2007, 201, 4913–4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukiman, N.L.; Zhou, X.; Birbilis, N.; Hughes, A.E.; Mol, J.M.C.; Garcia, S.J.; Zhou, X.; Thompson, G.E.; Sukiman, N.L.; Zhou, X.; et al. Durability and Corrosion of Aluminium and Its Alloys: Overview, Property Space, Techniques and Developments. Alum. Alloy. - New Trends Fabr. Appl. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, C.M.; Verma, C.; Aslam, J.; Aslam, R.; Zehra, S. Handbook of Corrosion Engineering: Modern Theory, Fundamentals and Practical Applications. Handb. Corros. Eng. Mod. Theory, Fundam. Pract. Appl. 2023, 1–459. [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, A.; Al-Amiery, A.A.; Alazawi, R.; Al-Ghezi, M.K.S.; Abass, R.H. Corrosion Inhibitors. A Review. Int. J. Corros. Scale Inhib. 2021, 10, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopha, H.; Norikawa, Y.; Motola, M.; Hromadko, L.; Rodriguez-Pereira, J.; Cerny, J.; Nohira, T.; Yasuda, K.; Macak, J.M. Anodization of Electrodeposited Titanium Films towards TiO2 Nanotube Layers. Electrochem. commun. 2020, 118, 106788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Azhar, M.R.; Fredj, N.; Burleigh, T.D.; Oloyede, O.R.; Almajid, A.A.; Ismat Shah, S. Influence of SiO2 Nanoparticles on Hardness and Corrosion Resistance of Electroless Ni–P Coatings. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2015, 261, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasturibai, S.; Kalaignan, G.P. Physical and Electrochemical Characterizations of Ni-SiO2 Nanocomposite Coatings. Ionics (Kiel). 2013, 19, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha Ray, S.; Okamoto, M. Polymer/Layered Silicate Nanocomposites: A Review from Preparation to Processing. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2003, 28, 1539–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhi, G.; Modi, O.P.; Sinha, A.S.K.; Singh, I.B. Effect of Sintering Temperatures on Corrosion and Wear Properties of Sol–Gel Alumina Coatings on Surface Pre-Treated Mild Steel. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Karapanagiotis, I. Materials with Extreme Wetting Properties: Methods and Emerging Industrial Applications. Mater. with Extrem. Wetting Prop. Methods Emerg. Ind. Appl. 2021, 1–370. [Google Scholar]

- Sajadi, G.S.; Ali Hosseini, S.M.; Saheb, V.; Shahidi-Zandi, M. Using of Asymmetric Cell to Monitor Corrosion Performance of 304 Austenitic Stainless Steel by Electrochemical Noise Method. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.; Baleizão, C.; Farinha, J.P.S. Functional Films from Silica/Polymer Nanoparticles. Mater. 2014, 7, 3881–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.L.; Cai, Y.X.; Liu, X.C.; Ma, G.W.; Lv, W.; Wang, M.X. Hydrophobic Modification on the Surface of SiO2Nanoparticle: Wettability Control. Langmuir 2020, 36, 14924–14932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, H.; Pramanik, C.; Heinz, O.; Ding, Y.; Mishra, R.K.; Marchon, D.; Flatt, R.J.; Estrela-Lopis, I.; Llop, J.; Moya, S.; et al. Nanoparticle Decoration with Surfactants: Molecular Interactions, Assembly, and Applications. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2017, 72, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Fan, H.; Su, N.; Hong, R.; Lu, X. Highly Hydrophobic Polyaniline Nanoparticles for Anti-Corrosion Epoxy Coatings. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 130540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuji, M.; Takei, T.; Watanabe, T.; Chikazawa, M. Wettability of Fine Silica Powder Surfaces Modified with Several Normal Alcohols. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 1999, 154, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haidary, J.T.; Haddad, J.S.; Alfaqs, F.A.; Zayadin, F.F. Susceptibility of Aluminum Alloy 7075 T6 to Stress Corrosion Cracking. SAE Int. J. Mater. Manuf. 2020, 14, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairy, S.K.; Turk, S.; Birbilis, N.; Shekhter, A. The Role of Microstructure and Microchemistry on Intergranular Corrosion of Aluminium Alloy AA7085-T7452. Corros. Sci. 2018, 143, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Li, X.; Yang, L.; Du, C. Corrosion Resistance of 316L Stainless Steel in Acetic Acid by EIS and Mott-Schottky. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 2008, 23, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Robson, J.D.; Yao, Y.; Zhong, X.; Guarracino, F.; Bendo, A.; Jin, Z.; Hashimoto, T.; Liu, X.; Curioni, M. Effects of Heat Treatments on the Microstructure and Localized Corrosion Behaviors of AA7075 Aluminum Alloy. Corros. Sci. 2023, 221, 111361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Verma, R.; Kango, S.; Constantin, A.; Kharia, P.; Saini, R.; Kudapa, V.K.; Mittal, A.; Prakash, J.; Chamoli, P. A Critical Review on Recent Progress, Open Challenges, and Applications of Corrosion-Resistant Superhydrophobic Coating. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; Ji, G.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, B. Sustainable Corrosion-Resistant Superhydrophobic Composite Coating with Strengthened Robustness. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 121, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamgain, H.P.; Pati, P.R.; Samanta, K.K.; Brajpuriya, R.; Gupta, R.; Pandey, J.K.; Giri, J.; Sathish, T.; Kanan, M. A Review on Bio-Inspired Corrosion Resistant Superhydrophobic Coating on Copper Substrate: Recent Advances, Mechanisms, Constraints, and Future Prospects. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, M.; Yang, C.; Yang, Z.; Liu, X. Insights into the Stability of Fluorinated Superhydrophobic Coating in Different Corrosive Solutions. Prog. Org. Coatings 2021, 151, 106043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, D.; Ou, J. Effect of Surface Nanostructure on Enhanced Atmospheric Corrosion Resistance of a Superhydrophobic Surface. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 647, 129058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM Standard G61-86 "Standard Test Method for Conducting Cyclic Potentiodynamic Polarization Measurements for Localized Corrosion Susceptibility of Iron, Nickel or Cobalt Based Aalloys"; 2010; Vol. 86.

- Liu, T.; Chen, S.; Cheng, S.; Tian, J.; Chang, X.; Yin, Y. Corrosion Behavior of Superhydrophobic Surface on Copper in Seawater. Electrochim. Acta 2007, 52, 8003–8007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Xing, Q.; Chen, Z.; Jin, M.; Xing, Q.; Chen, Z. A Review: Natural Superhydrophobic Surfaces and Applications. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 11, 110–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.L.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhai, J.; Song, Y.; Liu, B.; Jiang, L. Superhydrophobic Surfaces: From Natural to Artificial. Adv. Mater. 2002, 1857–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; McQuillan, A.J.; A Sharma, L.; Waddell, J.N.; Shibata, Y.; Duncan, W.J. Spark Anodization of Titanium–Zirconium Alloy: Surface Characterization and Bioactivity Assessment. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2015, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibaeva, T. V.; Laurinavichyute, V.K.; Tsirlina, G.A.; Arsenkin, A.M.; Grigorovich, K. V. The Effect of Microstructure and Non-Metallic Inclusions on Corrosion Behavior of Low Carbon Steel in Chloride Containing Solutions. Corros. Sci. 2014, 80, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.B.; Hu, H.X.; Zheng, Y.G. Synergistic Effects of Fluoride and Chloride on General Corrosion Behavior of AISI 316 Stainless Steel and Pure Titanium in H2SO4 Solutions. Corros. Sci. 2018, 130, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizi Mohazzab, B.; Jaleh, B.; Kakuee, O.; Fattah-alhosseini, A. Formation of Titanium Carbide on the Titanium Surface Using Laser Ablation in N-Heptane and Investigating Its Corrosion Resistance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 478, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, G.R.; Macdonald, D.D. Monte-Carlo Simulation of Pitting Corrosion with a Deterministic Model for Repassivation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 013540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilescu, C.; Drob, S.I.; Osiceanu, P.; Calderon-Moreno, J.M.; Drob, P.; Vasilescu, E. Characterisation of Passive Film and Corrosion Behaviour of a New Ti-Ta-Zr Alloy in Artificial Oral Media: In Time Influence of PH and Fluoride Ion Content. Mater. Corros. 2015, 66, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castany, P.; Gordin, D.M.; Drob, S.I.; Vasilescu, C.; Mitran, V.; Cimpean, A.; Gloriant, T. Deformation Mechanisms and Biocompatibility of the Superelastic Ti–23Nb–0.7Ta–2Zr–0.5N Alloy. Shape Mem. Superelasticity 2016, 2, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bi, Q.; Leyland, A.; Matthews, A. An Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Study of the Corrosion Behaviour of PVD Coated Steels in 0.5 N NaCl Aqueous Solution: Part II.: EIS Interpretation of Corrosion Behaviour. Corros. Sci. 2003, 45, 1257–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, A.B.; Sutanto, H.; Ruslan, W. Effects of Immersion in the NaCl and H2SO4 Solutions on the Corrosion Rate, Microstructure, and Hardness of Stainless Steel 316L. Res. Eng. Struct. Mat 2023, 9, 1153–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpanya, P.; Wongpinij, T.; Photongkam, P.; Siritapetawee, J. Improvement in Corrosion Resistance of 316L Stainless Steel in Simulated Body Fluid Mixed with Antiplatelet Drugs by Coating with Ti-Doped DLC Films for Application in Biomaterials. Corros. Sci. 2022, 208, 110611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, D. Facile Fabrication of High-Aspect-Ratio Superhydrophobic Surface with Self-Propelled Droplet Jumping Behavior for Atmospheric Corrosion Protection. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 555, 149549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yan, J.; Yu, T.; Zhang, B. Versatile Nonfluorinated Superhydrophobic Coating with Self-Cleaning, Anti-Fouling, Anti-Corrosion and Mechanical Stability. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 642, 128701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hao, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Ke, W. EIS Evaluation on the Degradation Behavior of Rust-Preventive Oil Coating Exposure to NaCl Electrolyte. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 492, 144359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Díaz, M.P.; Luna-Sánchez, R.M.; Vazquez-Arenas, J.; Lartundo-Rojas, L.; Hallen, J.M.; Cabrera-Sierra, R. XPS and EIS Studies to Account for the Passive Behavior of the Alloy Ti-6Al-4V in Hank's Solution. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2019, 23, 3187–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, J.R. Generalizations of '“Universal Dielectric Response”’ and a General Distribution-of-activation-energies Model for Dielectric and Conducting Systems. J. Appl. Phys. 1985, 58, 1971–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Ecorr (mV) |

icorr (A/cm2) |

Hysteresys |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl | |||

| Al 7075 | -750 | 1.54×10-4 | Positive |

| Al 7075 SiO2 | -721 | 5.91 ×10-5 | Positive |

| H2SO4 | |||

| Al 7075 | -589 | 1.45×10-3 | Negative |

| Al 7075 SiO2 | -420 | 2.28×10-4 | Negative |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).