Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

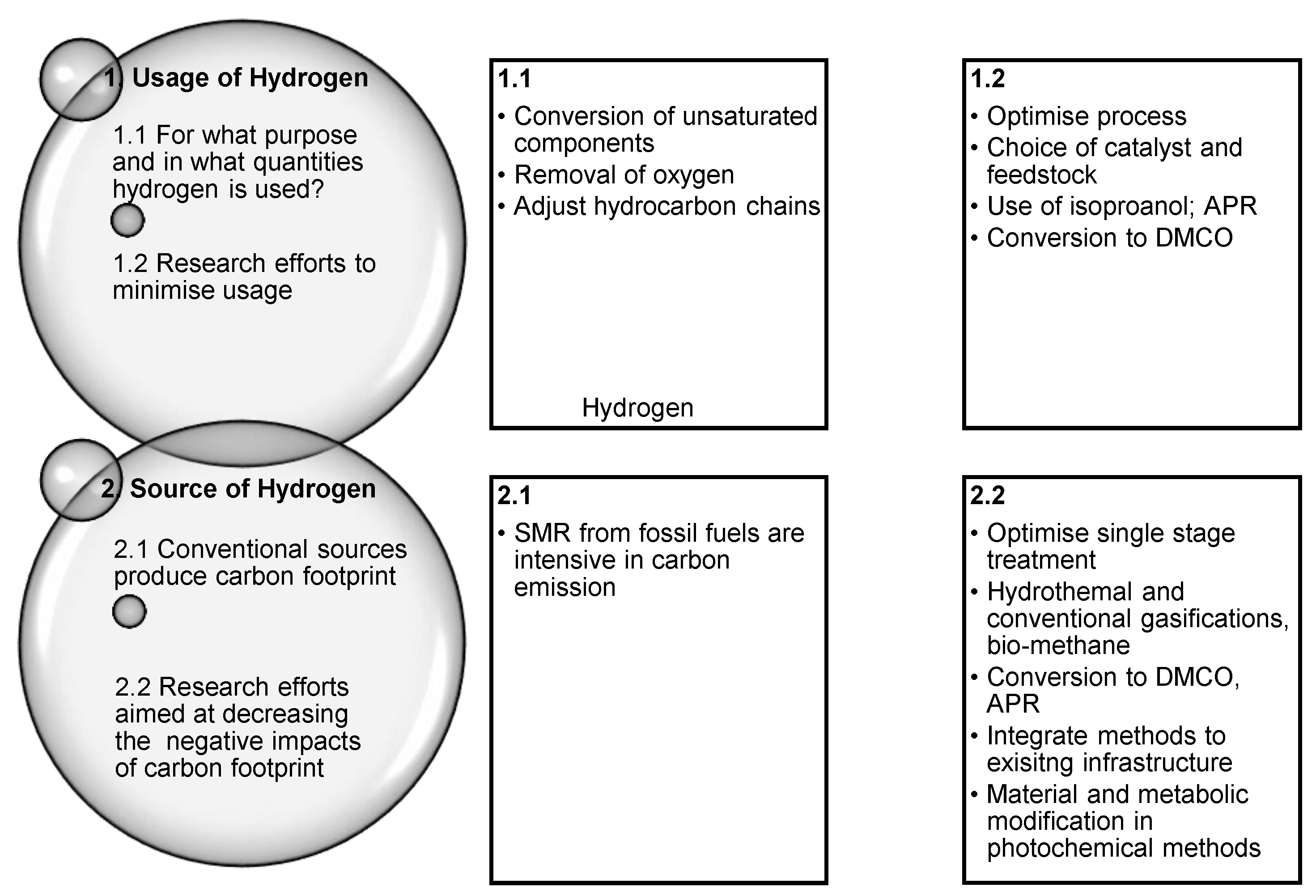

2. Usage of Hydrogen

3. Source of Hydrogen

4. Strategy for Alleviating the Issues of Source of Hydrogen and Usage of Hydrogen

4.1. Conventional Approach Impacting Greenhouse Gas Emission

| Study description | Research Problem | Research Output Emission benefit Cost |

Opportunity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feasibility of in-situ Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenation (CTH) to generate jet fuel from waste cooking oil in comparison to commercial Hydroprocessed Renewable Jet (HRJ) [22] | - High cost associated with the use of high-pressure hydrogen (25 to 100 bar) in HRJ or HEFA for proper mixing with oil - Storage and transportation issue of hydrogen - Relies on fossil source of hydrogen that emits harmful gases |

- 100 year GWP is 8% low in CTH without sequestering carbon | - Energy use for cooling in CTH is 59% low - 95% reduction in CAPEX of CTH compared to HRJ - CTH performs well in term of revenues except - Isopropanol contributes 68% of the total operation and maintenance cost |

- CTH profitable despite large input cost of isopropanol - Gas compression is costly compared to pumping isopropanol - CTH operates with cheaper catalyst (Activated carbon) unlike nickel-molybdenum based catalyst in hydrotreating HRJ - Performed nearly at atmospheric condition |

| Environmental assessment of first grade biorefinery based on conversion of sugar based feedstock (corn) to (DMCO) [23] | - How to produce SAF with the existing commercial first grade biorefineries? - To evaluate the environmental performance |

- Obtained average life cycle emission with and without carbon capture are: 36 g CO2 equivalent /MJ and 5 g CO2 equivalent /MJ | __ | - Corn to DMCO can bridge the SAF targets - Use of renewable source of hydrogen could further reduces emission during hydrogenation of DMCO - Effectual crop management practices could reduce the land use change - Prospect for economic viability study |

| Study of modified Nickel supported hexagonal mesoporous silica (HMS) in absence of hydrogen to produce renewable fuel [24] | - To identify the connection between the tested catalyst and the performance of deoxygenation (DO) in absence of hydrogen | - Improved the DO at 380ºC and free of hydrogen - 10 wt.% Nickel led to 92.5% conversion and 95.2% selectivity - Pore size and surface area of HMS played a critical part |

__ | - Ni/HMS is a promising catalyst to produce sustainable oil from non-edible oil feed with high conversion and performance in absence of hydrogen |

| Study of the enviro-economic effects for producing SAF from TOFA via catalytic deoxygenation under two scenarios of source of hydrogen – grey hydrogen (Case 1) and using hydrothermal gasification (Case 2) [26] | - Evaluate the integration of hydrothermal gasification to produce SAF | - Greenhouse reductions: 94% (Case 2) and 76% (Case 1) | - Minimum fuel selling price (MSP): USD $ 0.39/L (Case 2) against USD $ 0.62/L (Case 1) | - Economically and environmentally viable solution - Can process variety of waste feedstock such as sewage sludge, agricultural residues, FOG etc. -Optimisation of process to produce low-cost hydrogen |

| Study of enviro-economic implications on HEFA using in-situ hydrogen via APR [27] | - To assess the technical, economical, and environmental capacity of APR for improving the HEFA process | - Emission: 54% lower (11.7 g CO2 equivalent /MJ) than conventional method | - MSP: USD $ 1.84/kg, i.e., 17% lesser than SAF produced using hydrogen generated via electrolysis - Investment in capital: 6.6% higher - Direct manufacturing cost: 22% low due to less hydrogen demand externally and compression |

- Can be integrated in other approved SAF routes - Effect of cost of feedstock, plant capacity, yield of SAF requires further investigation for marketability |

| Study of cost, environmental impact, energy and exergy analysis of producing hydrogen from conventional and renewable sources [31] | - To compare and evaluate the different technologies depending on efficiencies for energy and exergy, the cost of generation, warming effect globally, and acidification potential (AP) inclusive social cost | - Energy efficiency is greatest in fossil fuel (83%) reforming and lowest in photocatalysis (2%) - Biomass gasification has best exergy efficiency (60%) - Photonic based hydrogen have almost zero GWP, AP and hence, negligible social cost of carbon (SCC) - Hydrogen via electrical methods have high GWP and SCC - Hydrogen produced from photonic resource have least AP, GWP and SCC - Hybrid and thermal based production methods perform better |

- Photoelectrochemical hydrogen is expensive (USD $ 10.36/kg hydrogen) | - Integrating the technologies with minimal environmental impacts can be the source of hydrogen. |

| Analysis of Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) for hydrogen production [30] | - To identify opportunity for removing carbon dioxide, renewable hydrogen from agricultural residues and other biomass wastes and provide insight for net zero economy of Europe | - Biohydrogen Carbon Capture Storage (BHCCS) can produce 12.5 Mtons of low carbon hydrogen and 133 Mtons of CO2 - Potential location for bio-hydrogen within desirable range from the suitable industries |

- Opportunity occurs for use of BECCS | |

4.2. Alternative Perspectives Impacting Variability in Hydrogen Usage and Greenhouse Gas Emission

5. Opportunities for Future Research and Development

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Air Transport Association (IATA). Global Outlook for Air Transport: Highly Resilient, Less Robust — June 2023. IATA Economic Report, 24 pp. (2023).

- Shahriar, M. F. & Khanal, A. The current techno-economic, environmental, policy status and perspectives of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). Fuel 325, 124905 (2022).

- Mupondwa, E., Li, X. & Tabil, L. Production of biojet fuel: Conversion technologies, technoeconomics, and commercial implementation. in Biofuels and Biorefining 157–213 (Elsevier, 2022). [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R. et al. Environmental and economic issues for renewable production of bio-jet fuel: A global prospective. Fuel 332, 125978 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wei, H. et al. Renewable bio-jet fuel production for aviation: A review. Fuel 254, 115599 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Why, E. S. K. et al. Renewable aviation fuel by advanced hydroprocessing of biomass: Challenges and perspective. Energy Conversion and Management 199, 112015 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Hernandez, E., Ramírez-Verduzco, L. F., Amezcua-Allieri, M. A. & Aburto, J. Process simulation and techno-economic analysis of bio-jet fuel and green diesel production — Minimum selling prices. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 146, 60–70 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Tao, L., Milbrandt, A., Zhang, Y. & Wang, W.-C. Techno-economic and resource analysis of hydroprocessed renewable jet fuel. Biotechnol Biofuels 10, 261 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Geleynse, S., Brandt, K., Garcia-Perez, M., Wolcott, M. & Zhang, X. The Alcohol-to-Jet Conversion Pathway for Drop-In Biofuels: Techno-Economic Evaluation. ChemSusChem 11, 3728–3741 (2018).

- Klein, B. C. et al. Techno-economic and environmental assessment of renewable jet fuel production in integrated Brazilian sugarcane biorefineries. Applied Energy 209, 290–305 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Tanzil, A. H., Brandt, K., Wolcott, M., Zhang, X. & Garcia-Perez, M. Strategic assessment of sustainable aviation fuel production technologies: Yield improvement and cost reduction opportunities. Biomass and Bioenergy 145, 105942 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Bezergianni, S., Dimitriadis, A., Kikhtyanin, O. & Kubička, D. Refinery co-processing of renewable feeds. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 68, 29–64 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Farooqi, H. & Fairbridge, C. Experimental Study on Co-hydroprocessing Canola Oil and Heavy Vacuum Gas Oil Blends. Energy Fuels 27, 3306–3315 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Chu, P. L., Vanderghem, C., MacLean, H. L. & Saville, B. A. Process modeling of hydrodeoxygenation to produce renewable jet fuel and other hydrocarbon fuels. Fuel 196, 298–305 (2017). [CrossRef]

- de Jong, S. et al. Life-cycle analysis of greenhouse gas emissions from renewable jet fuel production. Biotechnol Biofuels 10, 64 (2017).

- Morgan, T. et al. Catalytic deoxygenation of triglycerides to hydrocarbons over supported nickel catalysts. Chemical Engineering Journal 189–190, 346–355 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Wang, Q., Zhang, X., Wang, L. & Li, G. Hydrotreating of C18 fatty acids to hydrocarbons on sulphided NiW/SiO2–Al2O3. Fuel Processing Technology 116, 165–174 (2013).

- Afonso, F. et al. Strategies towards a more sustainable aviation: A systematic review. Progress in Aerospace Sciences 137, 100878 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Klein-Marcuschamer, D. et al. Technoeconomic analysis of renewable aviation fuel from microalgae, Pongamia pinnata, and sugarcane. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 7, 416–428 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Budsberg, E. et al. Hydrocarbon bio-jet fuel from bioconversion of poplar biomass: life cycle assessment. Biotechnology for Biofuels 9, 170 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Seber, G., Escobar, N., Valin, H. & Malina, R. Uncertainty in life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of sustainable aviation fuels from vegetable oils. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 170, 112945 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Barbera, E. et al. Techno-economic analysis and life-cycle assessment of jet fuels production from waste cooking oil via in situ catalytic transfer hydrogenation. Renewable Energy 160, 428–449 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Batten, R., Galant, O., Karanjikar, M. & Spatari, S. Meeting sustainable aviation fuel policy targets through first generation corn biorefineries. Fuel 333, 126294 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Zulkepli, S. et al. Modified mesoporous HMS supported Ni for deoxygenation of triolein into hydrocarbon-biofuel production. Energy Conversion and Management 165, 495–508 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, M. C., Silva, E. E. & Castillo, E. F. Hydrotreatment of vegetable oils: A review of the technologies and its developments for jet biofuel production. Biomass and Bioenergy 105, 197–206 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Umenweke, G. C., Pace, R. B., Santillan-Jimenez, E. & Okolie, J. A. Techno-economic and life-cycle analyses of sustainable aviation fuel production via integrated catalytic deoxygenation and hydrothermal gasification. Chemical Engineering Journal 452, 139215 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Pipitone, G., Zoppi, G., Pirone, R. & Bensaid, S. Sustainable aviation fuel production using in-situ hydrogen supply via aqueous phase reforming: A techno-economic and life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions assessment. Journal of Cleaner Production 418, 138141 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Su, G., Ong, H. C., Mofijur, M., Mahlia, T. M. I. & Ok, Y. S. Pyrolysis of waste oils for the production of biofuels: A critical review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 424, 127396 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Neuling, U. & Kaltschmitt, M. Techno-economic and environmental analysis of aviation biofuels. Fuel Processing Technology 171, 54–69 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L. & Mazzotti, M. Potential for hydrogen production from sustainable biomass with carbon capture and storage. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 157, 112123 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Dincer, I. & Acar, C. REVIEW AND EVALUATION OF HYDROGEN PRODUCTION METHODS FOR BETTER SUSTAINABILITY. Alʹtern. ènerg. èkol. 14–36 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, T. V. & Phillips, C. B. Renewable fuels via catalytic hydrodeoxygenation. Applied Catalysis A: General 397, 1–12 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Misra, P., Alvarez-Majmutov, A. & Chen, J. Isomerization catalysts and technologies for biorefining: Opportunities for producing sustainable aviation fuels. Fuel 351, 128994 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.-O. et al. Facile production of biofuel via solvent-free deoxygenation of oleic acid using a CoMo catalyst. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 239, 644–653 (2018). [CrossRef]

- El-Araby, R., Abdelkader, E., El Diwani, G. & Hawash, S. I. Bio-aviation fuel via catalytic hydrocracking of waste cooking oils. Bulletin of the National Research Centre 44, 177 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Song, M. et al. Hydroprocessing of lipids: An effective production process for sustainable aviation fuel. Energy 283, 129107 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Emmanouilidou, E., Mitkidou, S., Agapiou, A. & Kokkinos, N. C. Solid waste biomass as a potential feedstock for producing sustainable aviation fuel: A systematic review. Renewable Energy 206, 897–907 (2023). [CrossRef]

- AlNouss, A., McKay, G. & Al-Ansari, T. A comparison of steam and oxygen fed biomass gasification through a techno-economic-environmental study. Energy Conversion and Management 208, 112612 (2020). [CrossRef]

| Methods | Purpose | Quantity of hydrogen (From available studied sources) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

|

FT-SPK (Synthetic Paraffinic Kerosene) & FT-SPK/A (Synthetic Paraffinic Kerosene with Aromatics) ~Carbon containing biomass |

a. Refining fuel [2,3] | - No use of hydrogen (comparative study in [15]) - 0.01 MT hr for 43 MT/hr corn stover [11] |

- Make up hydrogen is used in the refining of FT product [5] - Theoretically 0.351 kg H/kg lignocellulosic biomass for synthesis of fuel [11] |

|

HEFA-SPK & HC-HEFA-SPK (Hydrocarbon) ~Oil based including algae |

a. Hydrogenation [3] b. Hydrodeoxygenation [11] c. Decarboxylation [3] d. Isomerisation [3] e. Hydrocracking [3] |

- For per kg feedstock hydrodeoxygenation - 0.033 kg; Isomerisation - 0.019 kg [7] - Hydrotreating and isomerisation/hydrocracking: 0.020 to 0.04kg for varied feedstock, cross refer [3] - 4% of oil based feedstock (comparative study [11]) - 0.15 MJ/MJ renewable jet fuel (RJF) (comparative study as referred [15]) - 0.3 MT/hr for 7 MT/hr soyabean oil [11] - 31.7 kg/tonne palm oil, 33.3 kg/tonne macuaba oil and 37.7 kg/tonne soyabean oil. Up to 2000kg/h processing 4 million tonnes of feedstock/annum [10] |

- Transform unsaturated triglyceride and fatty acids to saturated compounds [16] - HDO & DCOX converts saturated substance to linear alkanes of C15 to C18 [17] - Branched alkanes based liquid fuel produced via isomerisation and hydrocracking [2] - Hydrogen is used to deoxygenate [15] |

|

ATJ-SPK ~Alcohol and sugar based |

a. Hydrogenation [1,2,3,18] | - 0.16% of feedstock (comparative study [11]) - 0.08 MJ/MJ RJF (comparative study as referred [15]) - 0.07 MT/hr for 39 MT/hr corn stover [11] |

- Paraffins are produced after saturating double bonds in olefins [2] |

|

CHJ ~Algae, oil derived from waste and plant |

a. Hydrogenation [3,18] b. Decarboxylation [3] c. Hydrotreatment [3] |

- | - Hydrogen is used in hydrogenation [2] - Straight, branched and cyclo-olefins are transformed to alkanes [5] |

|

SIP-HFS or DSHC (Direct Sugars to Hydrocarbons) ~Lignocellulosic, sugar based feedstock |

a. Hydrotreating [1,2,18] | - 1.04% of feedstock (from the comparative study [11]) - 0.52 MJ/MJ RJF for high blending ratio and 0.12 MJ/MJ RJF for 10% blending fuel (comparative study as referred [15]) - 0.6 MT/hr for 56 MT/hr corn stover [11] |

- Sugar containing feedstock are modified to farnesene, further transformed to jet fuel [2,15] - Branched molecules are formed after hydroisomerisation and hydrocracking [19] -High hydrogen consumption contributes to GHG emission [15] |

|

FOG Co-processing ~Oil based inputs |

a.Hydrodeoxygenation [2] |

- For hydro processing: 420-590 nl per litre liquid feed [12] | - Oil based feedstock deoxygenated in presence of hydrogen [2] - Hydrogen consumption increases by 7% [12], if lipid-based feedstock blending (waste cooking oil) increases from 10 to 30%. - Saturated feedstocks consume less hydrogen (such as palm oil, animal fats etc. targeted for renewable diesel) [12] -Lipid feed such as algae oil, camelina oil, linseed oil etc. with unsaturated fatty acids are suitable for aviation fuels [12] - Different catalyst combinations to be further explored to comprehend its effect on the extent of deoxygenation and hydrotreatment process apart from CoMo and NiMo catalysts [12]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).