1. Introduction

Soybeans are an important food and cash crop worldwide due to their high protein, high oil content, and excellent nutritional properties[

1,

2,

3]. Normal, intact soybeans have high economic value and are mainly used in food processing, high-end feed, biofuels[

4], and industrial raw materials[

5]. Defective soybeans (such as spotted , immature or broken soybeans) are unsuitable for consumption and have low economic value, but can be used for low-end feed[

6], industrial protein extraction, or biodiesel production after detoxification treatment. as well as composted into organic fertilizer[

7] or used for biogas power generation, achieving resource utilization. Therefore, soybean testing and classification will have a certain impact on food processing[

8,

9], feed production, and breeding efficiency[

10,

11].

Traditional manual inspection methods suffer from low efficiency and high subjectivity, making it difficult to meet the demands of modern large-scale agricultural production[

12,

13]. With the rapid development of computer vision and artificial intelligence technologies, soybean seed inspection has undergone a revolutionary transformation, shifting from traditional image processing approaches to deep learning-based methods. Conventional machine learning techniques classify and identify soybeans by extracting features such as color, texture, shape, and spectral characteristics[

14,

15].

de Medeiros et al. [

16] proposed a method based on interactive and traditional machine learning methods to classify soybean seeds according to their appearance characteristics. The overall accuracy rate reached 0.94. Wei et al. [

17] employed the random subspace linear discriminant (RSLD) algorithm to classify soybean seeds, using 155 features to distinguish among 15 soybean varieties, and attained a classification accuracy of 99.2%. Although traditional machine learning methods have achieved high accuracy in soybean seed classification tasks, they exhibit clear limitations[

18]. On the one hand, feature extraction requires manual design, and manual feature selection is not only inefficient and lacking in generalization capability, but also adversely affects model accuracy. On the other hand, the inherent limitations of existing algorithmic architectures impose low upper bounds on model performance

Huang et al. [

19]proposed a lightweight network called SNet based on depthwise separable convolutions, which improves small-region recognition accuracy through a mixed feature recalibration (MFR) module. The network comprises seven separable convolution blocks and three convolution blocks integrated with MFR modules, achieving a recognition accuracy of 96.2%. Kaler et al. [

20] introduced a hybrid architecture that combines convolutional long short-term memory networks (ConvLSTM) with integrated laser biospeckle technology to enable intelligent diagnosis of diseased soybean seeds, attaining an accuracy of 97.72%. Sable et al. [

21] developed SSDINet, a lightweight deep learning model that incorporates depthwise separable convolutions and squeezed activation modules, achieving 98.64% accuracy across eight classification tasks with an identification time of 4.7 ms. Zhao et al. [

22]integrated the ShuffleNet model structure into the MobileNetV2 model, achieving a classification accuracy of 97.84% and an inference speed of 35 FPS. Chen et al. [

23] enhanced the nonlinear judgment ability of the MobileNetV3 model by adding a fully connected layer and a Softmax layer, increased the generalization ability of the model by adding a Dropout layer and removing the SE attention mechanism, reduced the memory consumption of the model, and achieved an average detection accuracy of 95.7%. These studies leverage modular designs—such as separable convolutions and attention mechanisms—to optimize network architectures, improve small-object recognition through techniques like MFR and squeeze excitation (SE) modules, and apply strategies such as Dropout and model pruning to enhance generalization, achieving high recognition accuracy. However, traditional CNN models are constrained by insufficient global feature modeling, while Transformer-based models face challenges including high computational complexity, difficulty balancing lightweight design with accuracy, and limited generalization capability. Consequently, achieving an optimal trade-off between accuracy and efficiency remains a significant challenge.

MobileViT as an emerging lightweight visual Transformer model [

24] that has demonstrated excellent performance in recent years in fields such as medical image analysis [

25], plant pest and disease detection [

26], and industrial defect identification[

27]. To address the challenges in soybean seed detection, this paper proposes a method based on the MobileViT architecture. Specifically, to overcome the problem of low detection accuracy caused by the high visual similarity among abnormal soybean seeds, the proposed approach first reduces the number of model parameters by replacing standard convolutions with depthwise separable convolutions. Next, the model’s feature extraction capability is enhanced through the introduction of dimension reconstruction and dynamic channel recalibration modules. Finally, the CBAM attention mechanism is integrated into the MV2 module to further improve feature representation and generalization ability. This design achieves the dual objectives of significantly reducing model complexity while enhancing detection accuracy for soybean seeds.

2. Materials and Methods

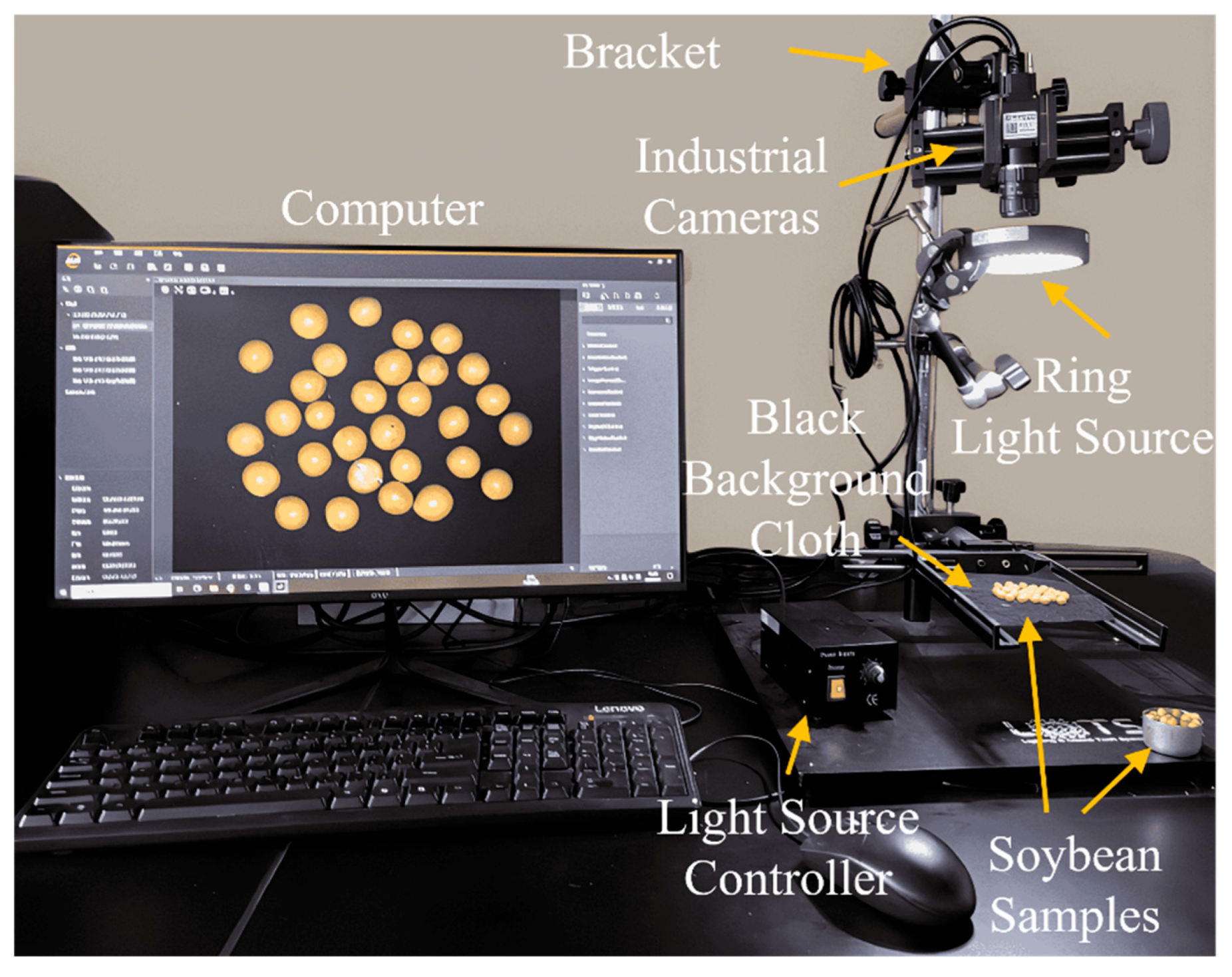

2.1. Image Acquisition Platform

The soybean image acquisition platform mainly consists of an industrial camera, ring light source, light source controller, black background cloth, fixed bracket, and computer, as shown in

Figure 1.

The test environment is summarized in

Table 1. The hardware configuration includes an RTX 3090 graphics card and an Intel Core i9-12900K processor. The operating system is Windows 10, and the programming language is Python 3.8.19. The model is implemented using the PyTorch deep learning framework, with CUDA version 11.2 and CUDNN version 8.1.1.

2.2. Image Acquisition and Preprocessing

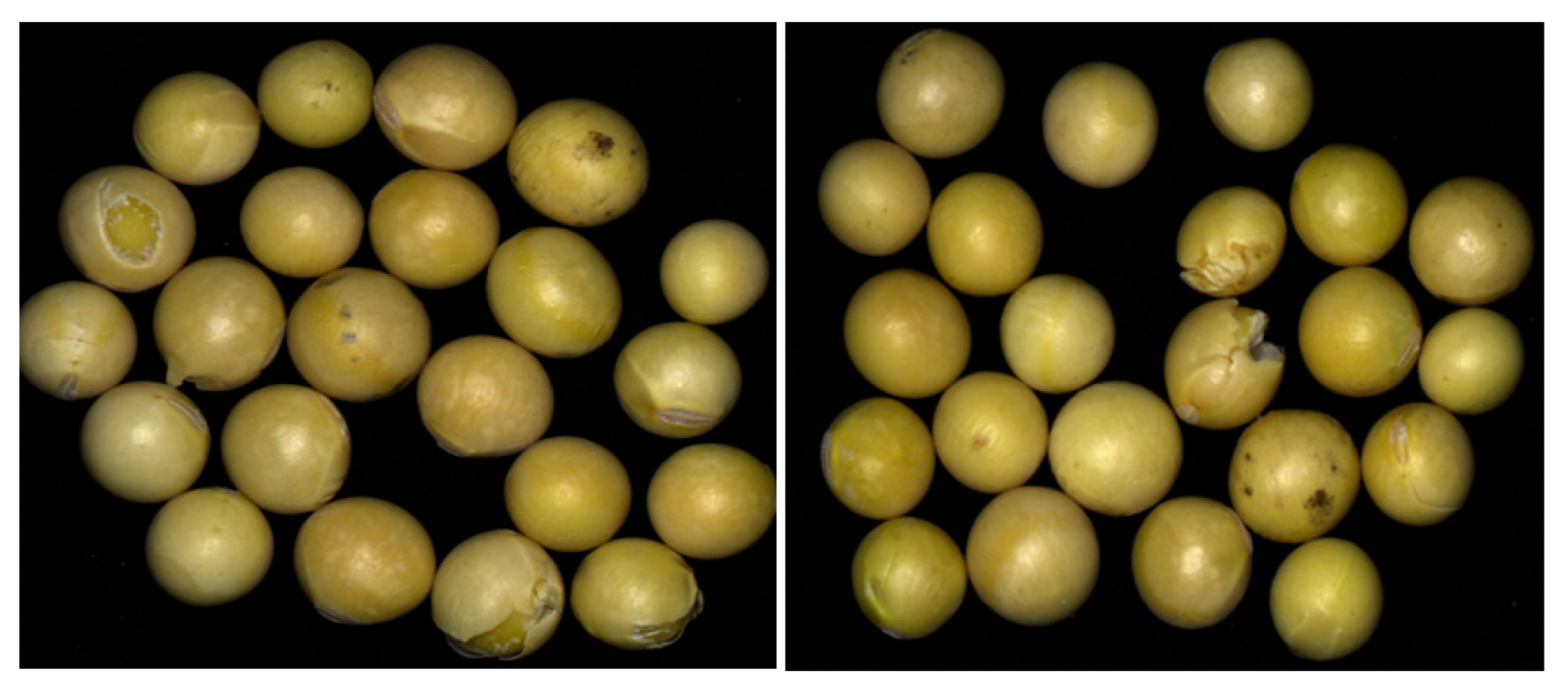

2.2.1. Image Acquisition

The soybeans used in the experiments were purchased from the market, sourced from Harbin City, Heilongjiang Province, and belonged to the variety “Xiao Jin Huang.” Prior to image acquisition, the MVS software developed by Hikvision was launched to enable real-time control and adjustment of the lens focal length, camera parameters, distance between the ring light source and the sample, and light source intensity, thereby ensuring image quality. During the experiment, approximately 25 seeds were placed in a tray for each capture, resulting in one image per batch. A total of 200 images were collected, each with a resolution of 4608 × 3456 pixels. Representative examples of the collected samples are shown in

Figure 2.

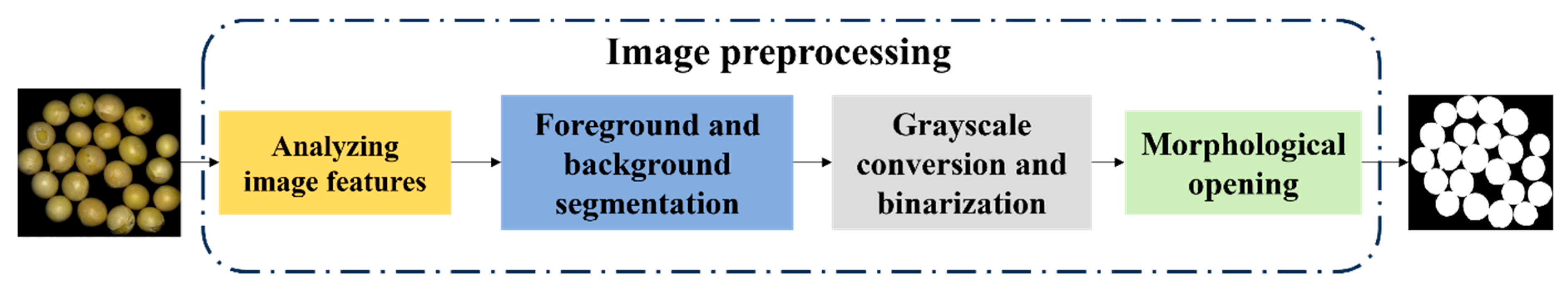

2.2.2. Image Preprocessing

To enable the segmentation of individual soybeans, the collected images were preprocessed through a series of steps, including background removal, grayscale conversion, binarization, and morphological opening. The detailed workflow is illustrated in

Figure 3.

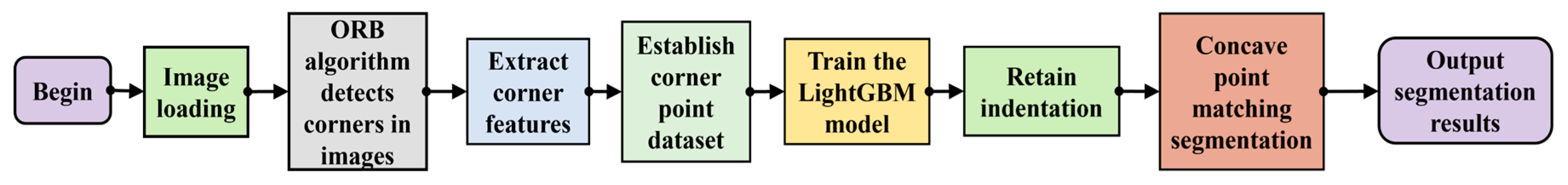

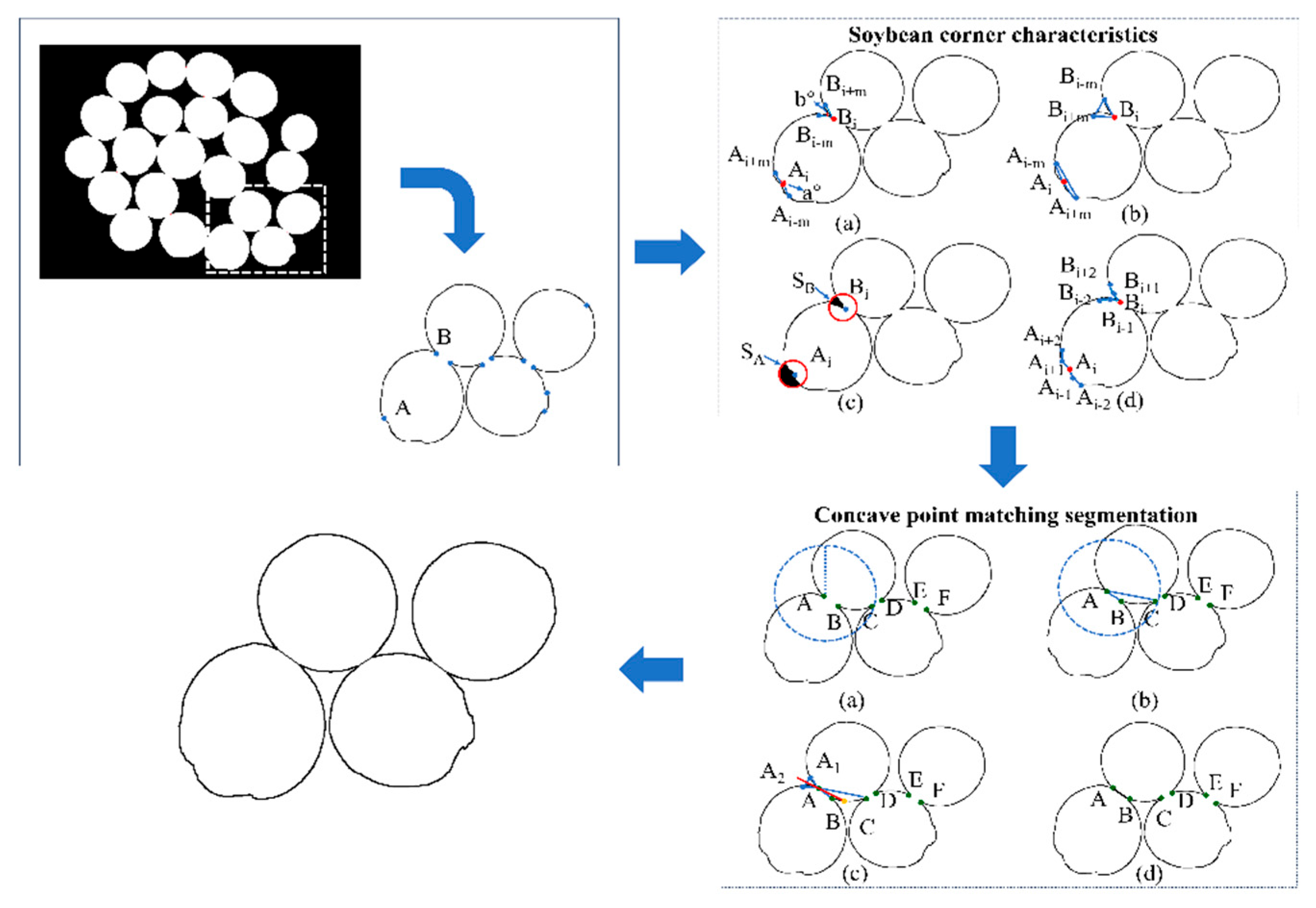

2.3. Soybean Seed Segmentation Algorithm Based on Multiple Corner Features

To establish a single-bean soybean dataset, it was necessary to convert multi-bean clumped soybeans into single-bean detection and identification by extracting each soybean from the image. However, when beans are clustered together, the curvature variations at the contact boundaries of their contours tend to be gradual. Furthermore, variations in surface reflectivity, combined with features such as indentations or damage, can lead to misclassification, resulting in incomplete extraction of individual beans. To address this challenge, this study proposes a soybean seed segmentation algorithm based on multi-feature corner detection, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

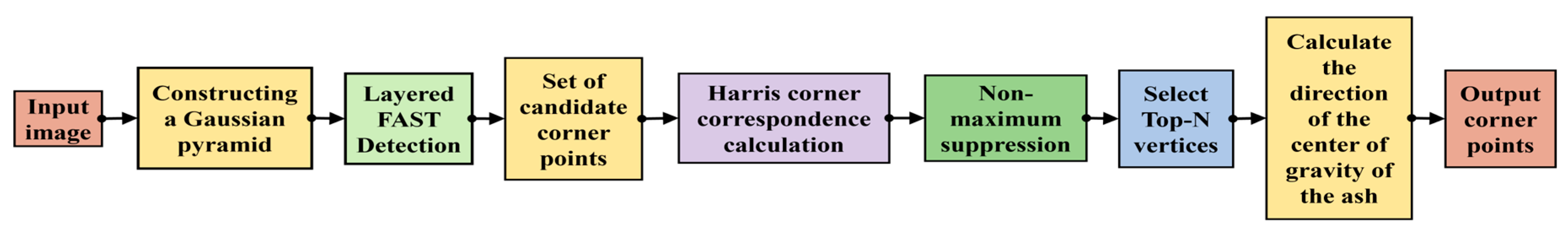

2.3.1. ORB Corner Detection Algorithm

Building upon the FAST (Features from Accelerated Segment Test) algorithm, Rublee et al. [

28] proposed the ORB (Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF) multi-corner detection algorithm, as shown in

Figure 5. First, a Gaussian pyramid is constructed for the input image to enable multi-scale detection. Then, the FAST algorithm is run on each layer of the image, and candidate corners are quickly located by comparing the gray-level differences in pixel neighborhoods. Next, the candidate points are scored and sorted using Harris corner response values, and the optimal corners are selected through non-maximum suppression (NMS). Finally, the gray-level centroid direction is calculated for each corner point to ensure rotation invariance, and feature points with position, scale, and direction information are output. The entire process ensures detection efficiency while improving the robustness of feature points through a pyramid structure and direction compensation.

2.3.2. Soybean Seed Segmentation Algorithm Based on LightGBM

LightGBM [

29] is an efficient gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT) framework developed by Microsoft, designed for large-scale data processing and high-speed training. Its core principle begins with discretizing continuous features into multiple bins using a histogram-based algorithm, thereby reducing computational complexity. To accelerate model convergence, it employs Gradient-based One-Side Sampling (GOSS) to retain high-gradient samples while discarding a portion of low-gradient samples. Furthermore, it utilizes Exclusive Feature Bundling (EFB) to merge mutually exclusive sparse features, effectively reducing feature dimensionality. During the decision tree growth phase, LightGBM adopts a leaf-wise growth strategy, which prioritizes splitting the leaf with the largest loss reduction rather than following the traditional layer-wise splitting method, thus enabling faster convergence. In addition, it supports both feature and data parallelism, further improving training efficiency on large datasets.

When segmenting images of multi-seeded sticky soybeans, corner points are first detected using the ORB algorithm as candidate points, as illustrated in

Figure 6A and

Figure 6B. Subsequently, features such as vector angle, triangular vector area, black pixel area within the circular module, and first-order difference chain code are extracted for each corner point. These features are then input into a LightGBM machine learning model to distinguish concave points from non-concave points. Next, a concave point matching algorithm is applied to identify corresponding concave point pairs, and finally, the matched concave points are connected to complete the segmentation. The overall process is illustrated in

Figure 6.

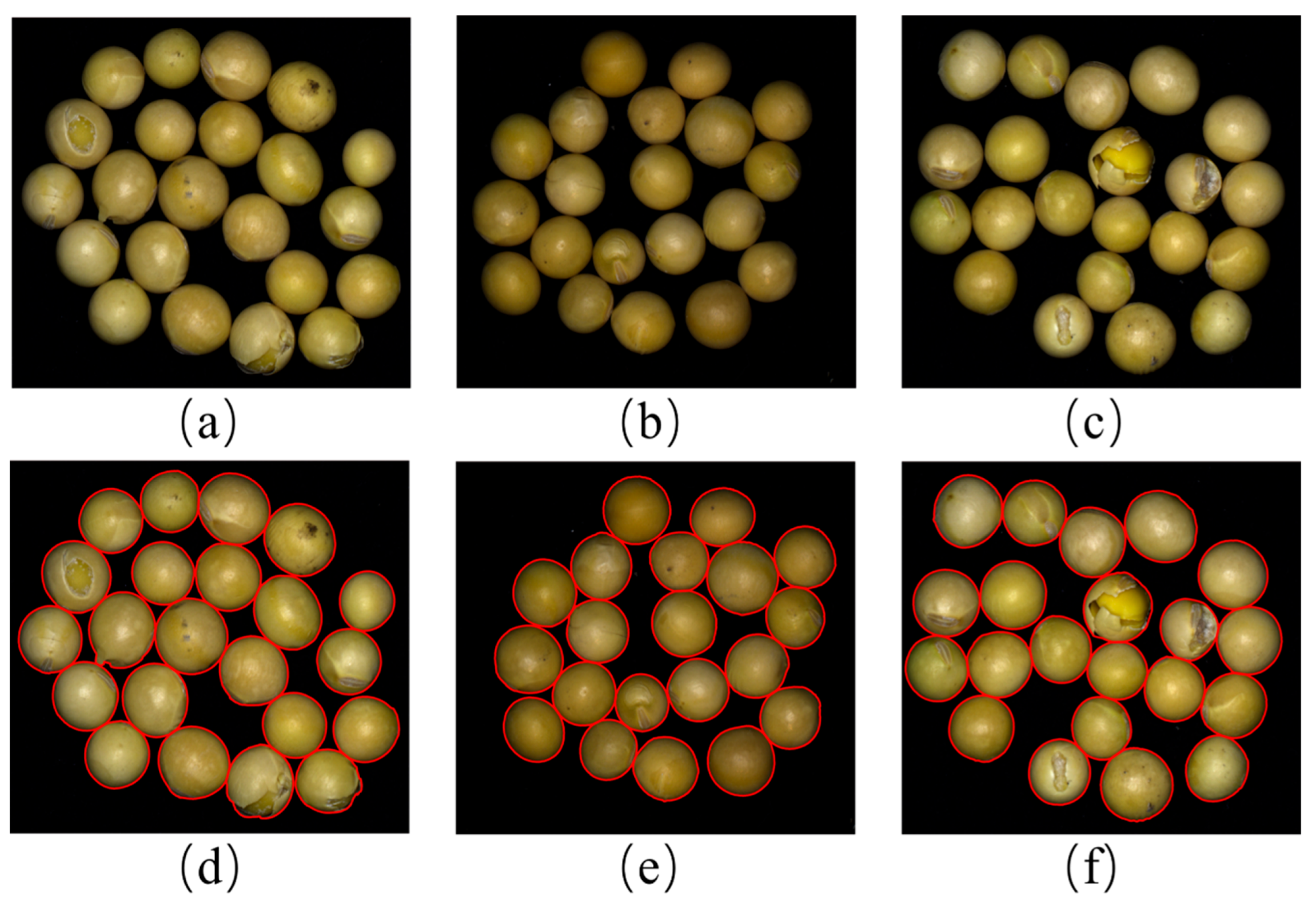

2.4. Partitioning Algorithm Verification

To validate the effectiveness and accuracy of the proposed soybean segmentation algorithm, three soybean images were randomly selected from the dataset for segmentation results, as shown in

Figure 7.

Figure 7(a–c) are the original soybean images, which include intact soybeans, broken soybeans, damaged soybeans, immature soybeans, and spotted soybeans.

Figure 7(d–f) are the segmented images (the outer contours of individual soybeans are indicated in red).

Figure 7 demonstrates that the proposed segmentation algorithm achieves excellent segmentation results.

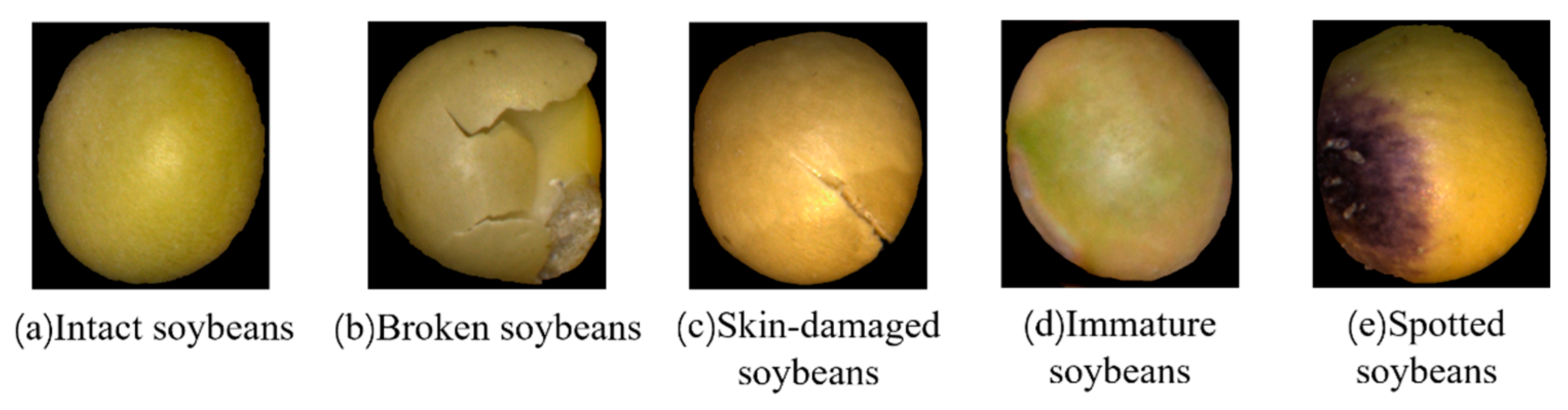

2.5. Soybean Seed Dataset

Using the aforementioned method, the collected soybean images were segmented, and the resulting single soybean images were manually annotated to construct a dataset comprising five categories: whole grains, broken grains, damaged grains, unripe grains, and spotted grains (as shown in

Figure 8). The number of images in each category is 1,210, 1,134, 1,143, 1,102, and 1,017, respectively. The dataset was split into training, testing, and validation subsets in an 8:1:1 ratio, which were used for model training, testing, and validation, respectively

3. Design of a Soybean Seed Detection Model Based on MobileViT

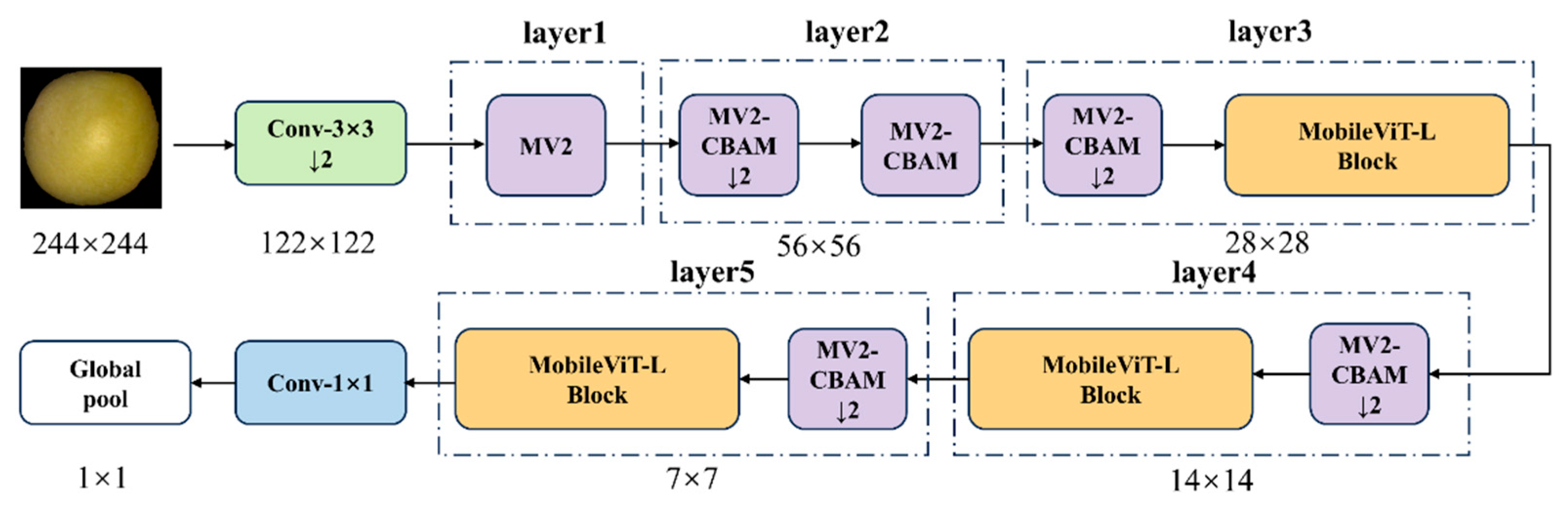

To achieve lightweight yet accurate soybean seed detection, this study proposes an improved model, MobileViT-SD (MobileViT for Soybean Detection). As illustrated in

Figure 9, the model is primarily composed of stacked MobileViT-L and MV2-CBAM modules, designed for efficient detection and recognition of soybean seeds.

3.1. MobileViT-L Module

The MobileViT network primarily consists of the MobileViT module and the MV2 module[

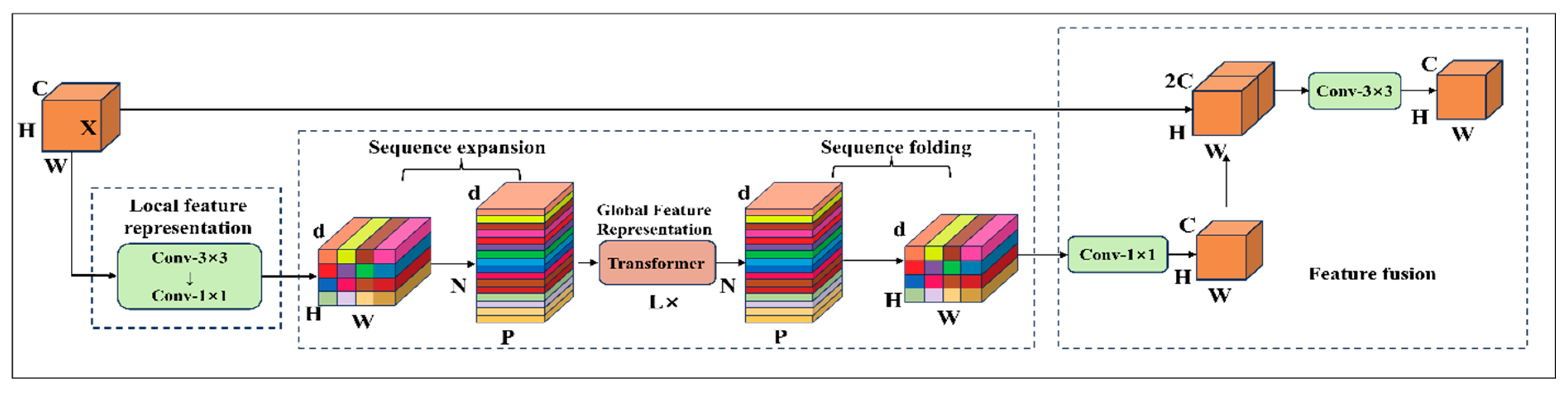

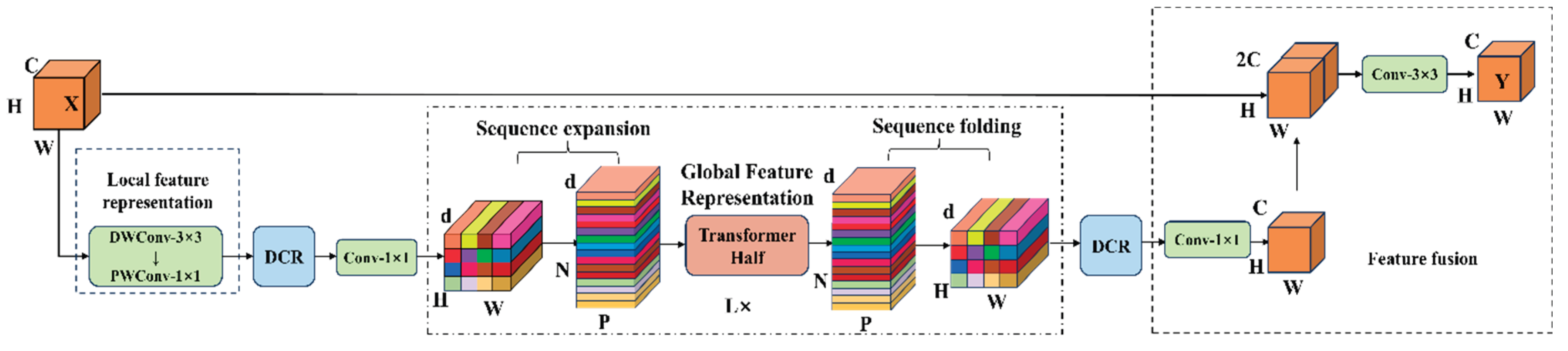

30]. The structure of the MobileViT module is shown in

Figure 10, which enables lightweight visual representation learning through a structured cross-modal feature interaction process. In the initial stage, the MobileViT module receives an input feature map of size H × W × C. It first extracts local spatial features using a 3×3 convolution layer, followed by a 1×1 convolution to expand the number of channels from C to d. In the global modeling stage, the expanded feature map is unfolded into a two-dimensional sequence of size H × W with d-dimensional vectors, which is then fed into the Transformer encoder. Within the encoder, the multi-head self-attention (MHSA) mechanism models dependencies between sequence elements to capture global contextual information, while the feedforward network (FFN) enhances feature representation through nonlinear transformations. After processing, the sequence is reconstructed into spatial features of size H × W × d. A 1×1 convolution is then applied to reduce the number of channels from d back to the original dimension C, and the compressed features are concatenated with the module’s original input. Finally, a 3×3 convolution is applied for feature fusion to produce the final output feature map.

Although the MobileViT network can effectively improve the performance of image classification tasks through its local and global feature fusion mechanism, related studies have shown that directly applying this network to fine-grained classification has significant limitations [

31]. This is because: 1. The phenotypic characteristics of different categories of soybean seeds are highly similar, and the MobileViT network lacks the ability to perceive such subtle differences, leading to limited classification accuracy; 2. The MobileViT network has relatively high parameter counts and computational complexity, making it difficult to meet the requirements of real-time detection scenarios. Therefore, this study targets the characteristics of the soybean seed dataset and makes the following improvements and optimizations to the MobileViT module:

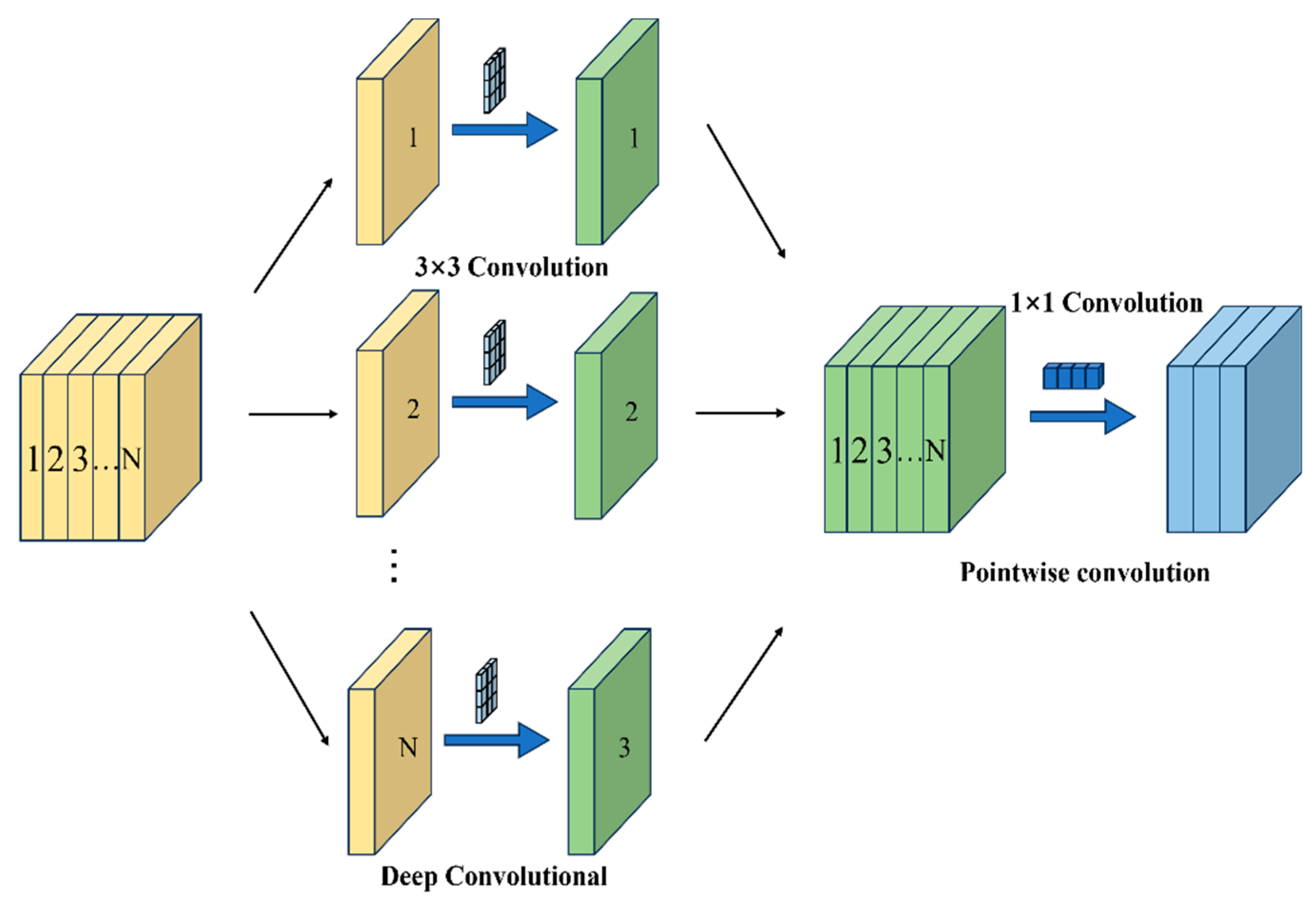

3.1.1. Using Depthwise Separable Convolution Modules to Reduce Model Parameter count

In the design of the MobileViT module, the standard 3×3 convolution used in the local feature extraction stage can effectively capture spatial features, but its parameter count and computational complexity increase quadratically with the number of channels. To address this, this study replaces the 3×3 convolution with depthwise separable convolution (DSC) [

32]. Through multi-level structural decomposition and sparsity design, the model achieves significant compression of computational complexity while maintaining feature expression capability, thereby reducing the number of parameters in the model.

The number of parameters in traditional convolution is shown in Equation (1):

The number of parameters in a depthwise separable convolution is calculated in two stages, as illustrated in

Figure 11. First, depthwise convolution is applied, where spatial features are extracted independently for each input channel. In this stage, each channel undergoes an independent 3×3 spatial convolution, processing only the local spatial features within that channel. Second, pointwise convolution is performed, in which the output from the depthwise convolution is passed through a 1×1 convolution to map the number of channels to

Cout. The total number of parameters is obtained by summing the parameters from these two stages, as expressed in Equation (2).

The comparison of the parameters of the two is shown in Equation (3):

In the above formula, K is the size of the convolution kernel, Cin is the number of input channels, and Cout is the number of output channels.

Although depthwise separable convolutions have fewer parameters compared with traditional convolutions, they facilitate inter-group information exchange and feature fusion across different channels, thereby significantly enhancing feature diversity and hierarchical representation capability. This improvement enables more effective semantic representation, particularly in lightweight architectures.

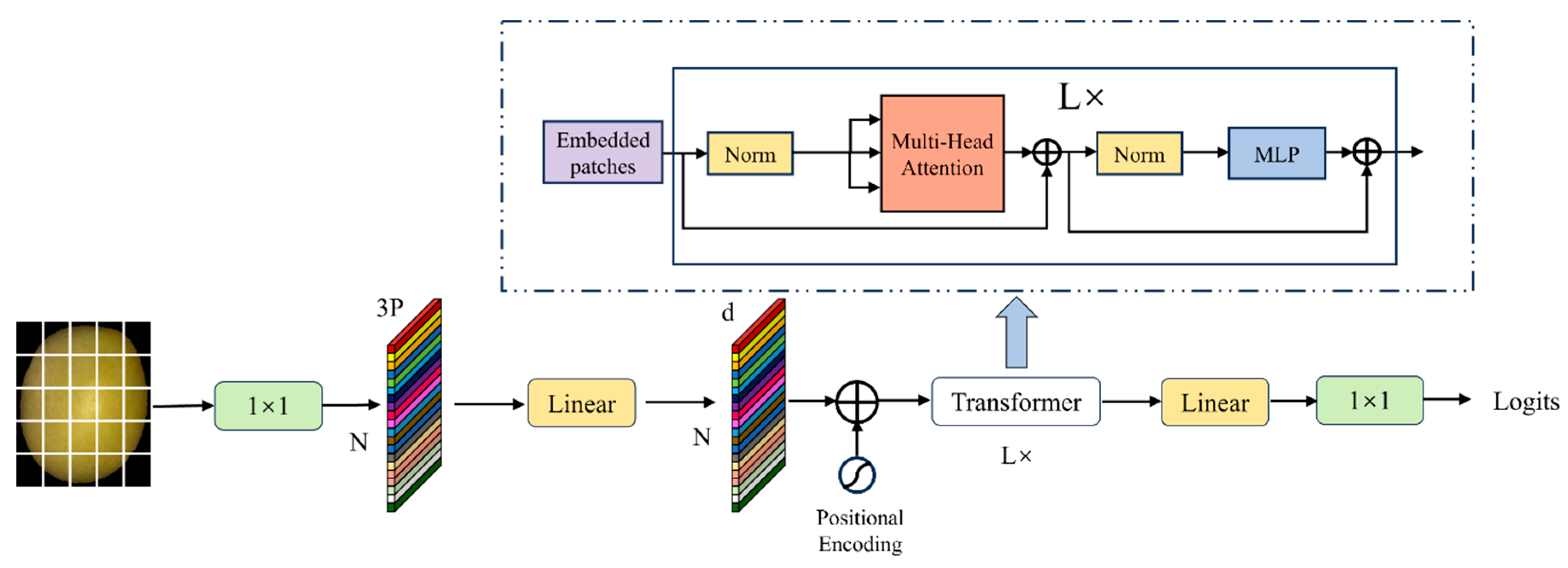

3.1.2. Simplifying Global Association Modeling Using Dimension Reconstruction

In MobileViT, the Transformer enhances the model's global context modeling capabilities through self-attention mechanisms. Deep features are fused with global semantic information through a lightweight Transformer module design, while the position-aware characteristics inherent in convolutions are used to replace explicit position encoding, thereby significantly improving the model's global feature expression capabilities. However, the self-attention mechanism requires calculating the similarity of all position pairs in the input sequence, which not only results in high computational complexity but also necessitates stacking multiple attention layers for certain tasks, leading to high cumulative computational costs and significant increases in computational load and parameter count. To address this, this study proposes a dimension reconstruction method called THD (Transformer Half-Dimension) to improve the Transformer architecture. The input feature dimension of the Transformer module is reduced to half of the original channel count. First, 1×1 convolution is used for channel compression, followed by lightweight multi-head attention calculation in the low-dimensional space. Then, 1×1 convolution is used to restore the original channel count (as shown in

Figure 12).

This dimensionality reconstruction effectively reduces the computational scale of the attention matrix while preserving key feature representations, enabling the attention weights to concentrate more on strongly correlated regions. By combining dimension reconstruction with a dynamic filtering mechanism, the proposed design significantly improves computational efficiency and filters redundant information, while maintaining robust global correlation modeling. This approach provides a framework for synergistic optimization of accuracy and efficiency, particularly suited for resource-constrained scenarios, achieving substantial reductions in computational complexity without sacrificing expressive power.

3.1.3. Enhancing the Extraction of Local and Global Features Through Dynamic Channel Recalibration

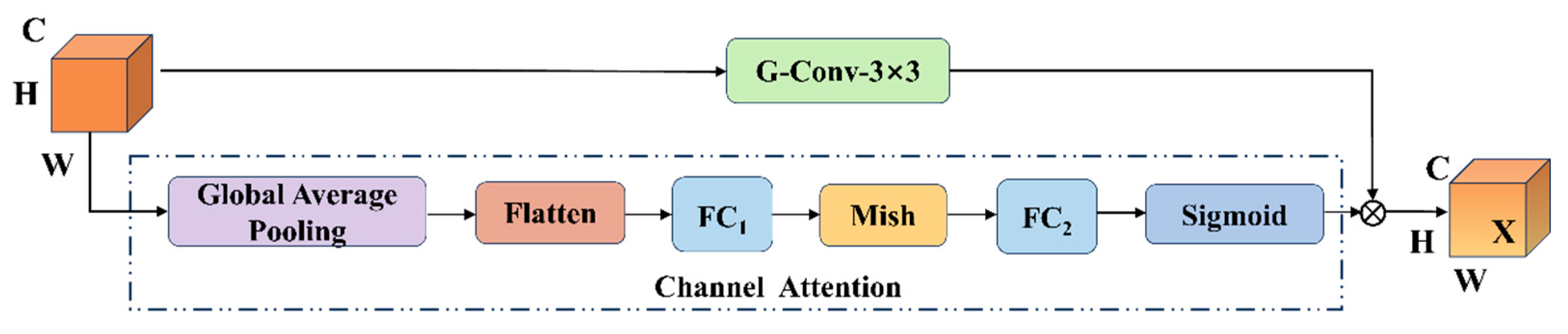

Soybean seeds involve local features such as surface texture, shape, and color, as well as global features such as overall morphology and arrangement patterns. Effective feature extraction therefore requires capturing fine-grained local details while simultaneously modeling global structural information. To address this need, this study introduces the Dynamic Channel Recalibration (DCR) module to enhance the extraction of both local and global features.As illustrated in

Figure 13, the core principle of DCR is to strengthen the network’s feature representation capability by dynamically adjusting channel weights and recalibrating inter-channel interactions. The module is composed of two branches: a channel attention branch and a group convolution branch, which work in a two-stage collaborative manner to achieve efficient and targeted feature optimization.

Let the input features be

X∈R

H×W×C, where

H×W is the spatial dimension and C is the number of channels. First, the spatial dimension is compressed through global average pooling, followed by two fully connected layers to generate channel attention weights. As shown in Equations (4) and (5):

where

W1∈R

C/r×C,

W1∈R

C×C /r,and δ is the ReLU activation function.

The normalized original features are subjected to channel-wise weighting via the Sigmoid function, which compresses the weights into the [0, 1] range. This operation prevents feature scaling imbalance caused by extreme values and ensures that the weights across all channels remain on the same magnitude, thereby enabling fair cross-channel importance comparison, as shown in Equations (6) and (7).

⊙ indicates channel-by-channel multiplication

Grouped convolution enhances cross-channel feature interaction through grouped convolution, as shown in the following equation.

xatt is uniformly divided into G along the channel dimension, and

k×k convolution

Kg is independently applied to each group. After feature splicing and merging, the output is grouped, and finally, the residual connection is retained to preserve the original information. While maintaining the lightweight characteristics of the convolution kernel, cross-channel information interaction is promoted, and the final output is an optimized feature with the same dimension as the input.

This design achieves coordinated optimization of channel awareness and cross-channel fusion with minimal computational overhead by separating channel importance assessment and feature recombination.

After the above three improvements and optimizations, the MobileViT-L module structure is shown in

Figure 14.

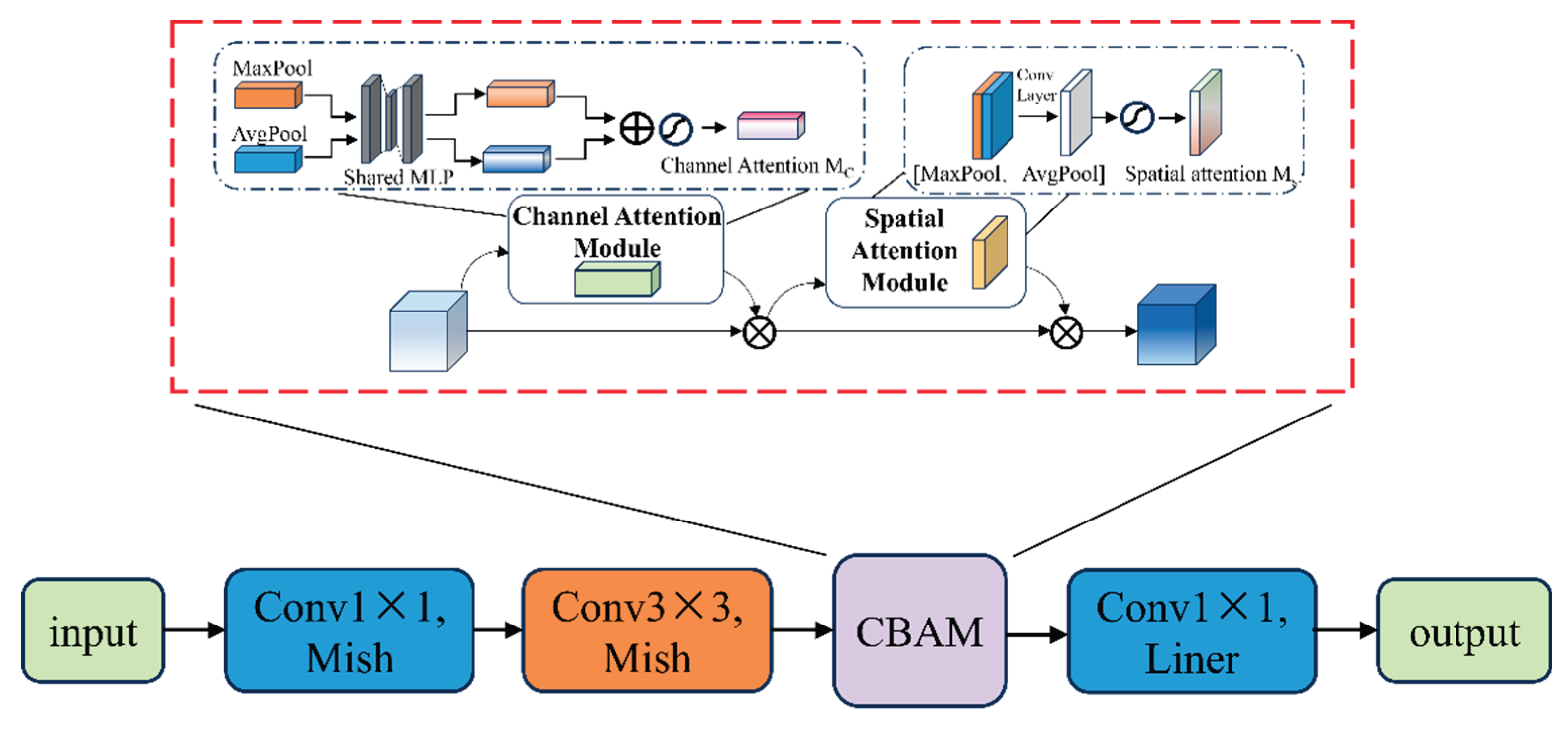

3.2. MV2-CBAM Module

MV2 is the core module of MobileNetV2, which achieves lightweight and efficient feature extraction through the collaborative design of a back-residual structure and depth-separable convolutions[

33]. First, pointwise convolution is applied to significantly expand the channel dimension, enhancing the nonlinear representation capability. This is followed by depthwise convolution to extract spatial features while reducing computational cost. Finally, another pointwise convolution without activation compresses the channels back to their original dimension. Residual connections are enabled only when the input and output channels match and the spatial resolution remains unchanged, ensuring stable gradient propagation.

Depthwise separable convolution decomposes standard convolution into channel-wise spatial filtering and pointwise channel fusion, greatly reducing parameter count. In MobileNetV2, the ReLU6 activation function imposes a threshold constraint on activation values, striking a balance between representational strength and stability. However, ReLU6 may cause neuron inactivation (“dead neurons”) due to hard clipping during training, thereby reducing feature utilization.

The Mish activation function [

34] is a high-performance neural network activation function whose core advantage lies in combining smooth nonlinearity with self-gating mechanisms. It retains the unbounded positive output characteristics similar to ReLU while enhancing noise robustness by preserving small negative activations. Its continuously differentiable nature significantly improves gradient flow, effectively alleviating the vanishing gradient problem in deep networks. Therefore, replacing ReLU6 with Mish to mitigate the “dead neuron” issue caused by hard clipping can enhance the model's generalization ability under complex data distributions. The Mish expression is as follows:

In soybean seed detection tasks, capturing both the microscopic details and macroscopic morphology is challenging due to the subtle differences in seed color and size. Model performance can be improved by embedding an attention mechanism into the MV2 module, which enhances the discrimination of dynamic feature channels and focuses on key spatial regions. This integration enables the model to maintain accurate feature extraction capabilities while effectively addressing the fine-grained variations present in soybean seeds.

CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module) is a lightweight dual attention mechanism module [

35].Dynamically enhancing CNN feature representations through cascaded channel attention and spatial attention [

36].

Channel attention: Perform global averaging and max pooling on the input

X to obtain two sets of descriptors

zavg and

zmax∈

RC, and generate channel attention maps through a shared MLP, as shown in Equation 13:

Spatial attention: After channel weighting of the feature map, perform max and average pooling on the channel dimension, concatenate, and input into a 7×7 convolution to generate a spatial attention map, as shown in Equation 14:

In the formula, X′ = Mc⊕X, the final output is Mx⊕X′.

The channel attention module uses average pooling and max pooling to extract channel statistical information, combines it with a shared MLP to generate channel weights, and completes channel importance calibration to highlight key feature dimensions. The spatial attention module fuses channel-direction pooled features with convolution to generate spatial weights, outputting features that optimize channel and spatial positions. Therefore, by introducing the CBAM mechanism into MV2 and replacing ReLU6 with Mish, the MV2-CBAM module is formed, as shown in

Figure 15.

3.3. Evaluation Indicators

Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score are used to evaluate the model [

37], as follows:

Among these, TP represents the number of target soybean categories correctly identified by the model, TN denotes the number of non-target soybean categories correctly identified, FP refers to the number of non-target soybean categories incorrectly classified as target categories, and FN indicates the number of target soybean categories that exist in reality but were missed by the model.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. MobileViT-SD Model Detection Results and Analysis

The MobileViT-SD model was applied to the validation set, and the recognition results are shown in

Table 2. The model can accurately identify the categories of soybean seeds. As shown in

Table 2, the MobileViT-SD model achieves an average accuracy rate of 98.40%, a recall rate of 98.40%, and an F1 score of 98.38% for the recognition of five categories of soybean seeds. Among them, the model achieved 100% accuracy, recall rate, and F1 score for detecting immature grains. This may be because immature grains are greenish in color and wrinkled in shape, which are significantly different from other types of soybeans in terms of color and shape, making their characteristics more obvious and thus achieving 100% detection accuracy. However, the model had low recall rates and F1 scores for the two categories of broken grains and skin-damaged grains, which may be due to the similarity between broken grains and skin-damaged grains.

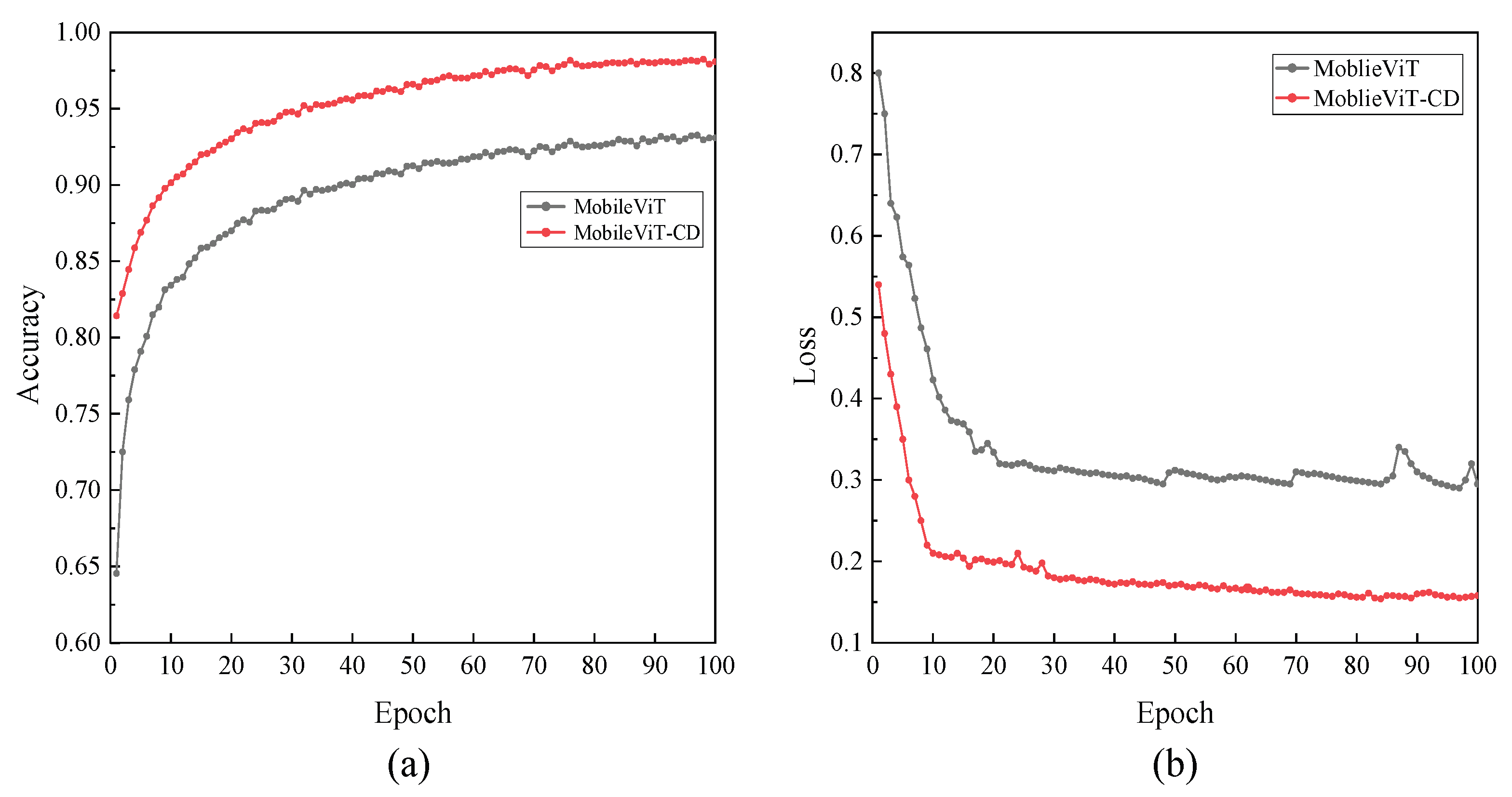

Figure 16(a,b) present the accuracy curves on the validation set and the loss curves on the training set for the MobileViT and MobileViT-SD models, respectively. As shown, compared with MobileViT, MobileViT-SD not only achieves a notable improvement in accuracy but also exhibits a clear reduction in loss values. These results indicate that the proposed improvements and optimizations have significantly enhanced the detection performance of the MobileViT-SD model.

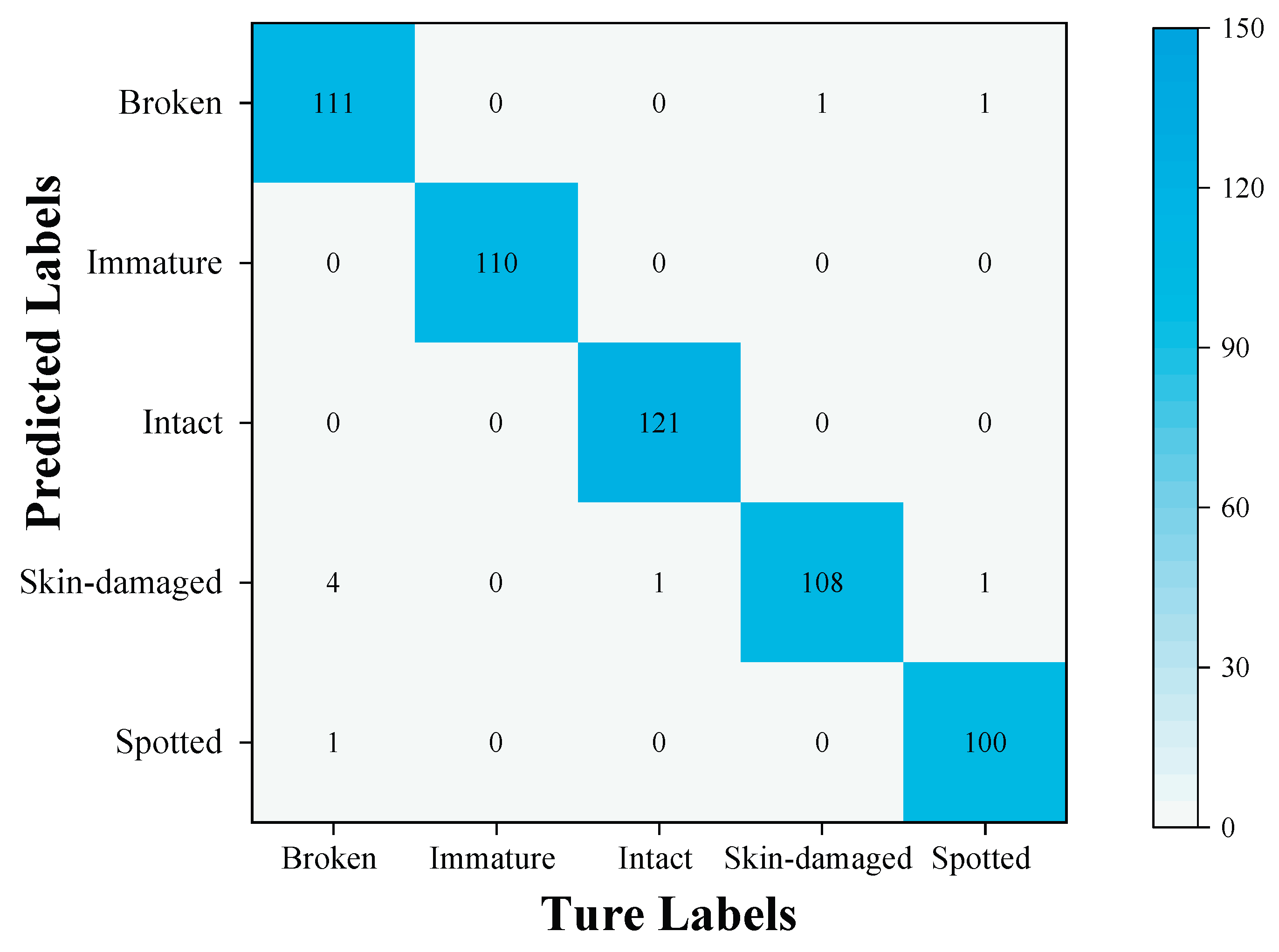

To further validate the generalization capability and robustness of the MobileViT-SD model, soybean classification performance on the validation set was analyzed using a confusion matrix, as illustrated in

Figure 17. The model successfully identified 100% of the immature and intact soybean samples. Misclassifications were limited to a single instance of a spotted bean being incorrectly labeled as a broken bean, two instances of broken beans being misclassified, and five instances of skin-damaged beans being misclassified. The overall detection accuracy reached 98.57%, indicating that the MobileViT-SD model exhibits excellent generalization ability and robustness in soybean classification.

4.2. The Impact of Attention Mechanisms on Model Performance

4.2.1. The impact of CBAM Module Embedding Location on Model Performance

To investigate the optimal embedding strategy for the CBAM attention module within the MV2 network architecture, three configurations were systematically examined: embedding before channel expansion, embedding after channel expansion, and a dual embedding strategy. The comparative results, presented in

Table 3, reveal that the integration of the CBAM module markedly enhances detection performance relative to the baseline model without attention mechanisms. Among the three configurations, embedding after channel expansion delivers the most substantial gains, particularly in terms of refined feature extraction and improved classification accuracy. This superiority may be attributed to the reinforcement of salient information in the low-dimensional feature space, which mitigates the dilution of critical features during subsequent expansion, while also stabilizing gradient propagation and alleviating the gradient conflicts observed in the dual embedding scheme.

4.2.2. Impact of Different Attention Mechanisms on Model Performance

To assess the influence of various attention mechanisms on model performance, CBAM, SE, ECA, and SimAM modules were embedded into the model after channel expansion and subsequently evaluated on the validation set. The experimental results, summarized in

Table 4, clearly demonstrate that the incorporation of any attention module leads to a marked improvement in performance metrics. Among these, the CBAM module consistently achieves the highest scores across all evaluation indicators. This superiority can be attributed to its capability to concurrently model dependencies in both channel and spatial dimensions, thereby enabling a more comprehensive representation of feature interactions and ultimately yielding enhanced detection accuracy and classification robustness.

4.3. Ablation Experiment

To investigate the impact of different improvement methods on model performance, a series of ablation experiments were conducted, with the results presented in

Table 5. Replacing the 3×3 convolutions in the MobileViT module with depthwise Separable Convolutions (DSC) not only improved the model's accuracy and F1 score but also significantly reduced the number of parameters. When THD was introduced on top of DSC, although the model's accuracy was slightly affected, the number of parameters further decreased to 1.77M, a reduction of 2M compared to the original model, approximately 53%; If the dynamic channel recalibration module DCR is further introduced after local and global feature extraction in the model, although the number of parameters in the model increases slightly (from 1.77 million to 1.86 million), the DCR module enhances the degree of feature information interaction and improves the model's feature fusion capabilities, thereby increasing the model's accuracy to 97.13%; After adding the CBAM attention mechanism to the MV2 module of the model, the model's ability to extract key features is enhanced, and the accuracy rate is improved by 0.72%, reaching 98.03%; by modifying the ReLU6 activation function to the more efficient Mish activation function, the model's accuracy rate is further improved by 0.36%, reaching the highest value of 98.39%. Compared to the original MobileViT model, the accuracy rate improved by 2.63%, the F1 score increased by 2.89%, and the number of model parameters also additionally decreased by 1.83M.

4.4. Comparative Analysis with Existing Classical Models

To further assess the performance of the MobileViT-SD model, we compared it with several mainstream neural network architectures, as summarized in

Table 6. Compared to other lightweight neural network models such as EfficientNet, MobileNet, ResNet, ShuffleNetV2, and MobileViT, the MobileViT-SD model achieved the highest accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, while also possessing the smallest parameter count and shortest inference time.

When compared with heavyweight models, MobileViT-SD slightly lagged behind the ConvNeXt model in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, but outperformed Vgg16, ResNet50, and DenseNet121. However, the number of parameters in the MobileViT-SD model is only 2% of that in ConvNeXt, and its inference time is only 20% of that in ConvNeXt, both significantly lower than those of other heavyweight models. This demonstrates that MobileViT-SD imposes minimal computational and storage overhead during both training and inference, achieving high recognition accuracy without requiring substantial memory bandwidth or computational power. Consequently, the model is well suited for deployment in resource-constrained environments, particularly in real-time agricultural quality inspection scenarios where efficiency, portability, and energy efficiency are critical for large-scale, on-site soybean classification.

5. Conclusions

(1) The proposed adhesion segmentation algorithm based on multiple corner features can rapidly and accurately segment adhered soybean grains.

(2) The optimization and improvement methods adopted, including replacing ordinary convolutions with separable convolutions, introducing dimension reconstruction and dynamic channel recalibration modules, and integrating the CBAM attention mechanism to the MV2 module, can all effectively enhance the performance of the MobileViT model.

(3) The proposed MobileViT-SD model, built upon the MobileViT architecture, achieves high-precision soybean quality detection. Its detection accuracy and efficiency surpass those of typical lightweight models and several mainstream heavyweight models currently in use.

(4) The MobileViT-SD model features a highly optimized lightweight architecture, efficient inference capability, and low resource consumption, making it well suited for deployment on edge computing devices and other resource-constrained platforms.

References

- Sui, Y.; Zhao, X.; Ding, J.; Sun, S.; Tong, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhao, Y. A Nondestructive and Rapid Method for in Situ Measurement of Crude Fat Content in Soybean Grains. Food Chemistry 2025, 491, 144862. [CrossRef]

- Sreechithra, T.V.; Sakhare, S.D. Impact of Processing Techniques on the Nutritional Quality, Antinutrients, and in Vitro Protein Digestibility of Milled Soybean Fractions. Food Chemistry 2025, 485, 144565. [CrossRef]

- Montanha, G.S.; Perez, L.C.; Brandão, J.R.; De Camargo, R.F.; Tavares, T.R.; De Almeida, E.; Pereira De Carvalho, H.W. Profile of Mineral Nutrients and Proteins in Soybean Seeds (Glycine Max (L.) Merrill): Insights from 95 Varieties Cultivated in Brazil. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2024, 134, 106536. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xie, G.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Z. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Soybean Oil with CaO/Bio-Char Based Catalyst to Produce High Quality Biofuel. Journal of Renewable Materials 2022, 10, 3107–3118. [CrossRef]

- Madayag, J.V.M.; Domalanta, M.R.B.; Maalihan, R.D.; Caldona, E.B. Valorization of Extractible Soybean By-Products for Polymer Composite and Industrial Applications. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2025, 13, 115703. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.Q.; Hussain, A.S.; Araujo, A.N.; Strebel, L.M.; Corby, T.L.; Rhodes, M.A.; Bruce, T.J.; Cuéllar-Anjel, J.; Davis, D.A. Effects of Different Soybean Protein Sources on Growth Performance, Feed Utilization Efficiency, Intestinal Histology, and Physiological Gene Expression of Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus Vannamei) in Green Water and Indoor Biofloc System. Aquaculture 2026, 611, 743021. [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Gong, X.; Ding, H.; Li, S.; Hao, D.; Yu, K.; Ma, Q.; Sun, X.; Muneer, M.A. Vermicomposting with Food Processing Waste Mixtures of Soybean Meal and Sugarcane Bagasse. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2022, 28, 102699. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ma, X.; Li, L.; Yang, L.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H. Purine Content of Different Soybean Products and Dynamic Transfer in Food Processing Techniques 2025.

- Hammond, B.G.; Jez, J.M. Impact of Food Processing on the Safety Assessment for Proteins Introduced into Biotechnology-Derived Soybean and Corn Crops. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2011, 49, 711–721. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, X.; Hu, B.; Li, W.-X.; Ning, H. QTN Mapping, Gene Prediction and Molecular Design Breeding of Seed Protein Content in Soybean. The Crop Journal 2025, S2214514125001631. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhou, G.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.; Shen, Y.; Ma, X.; Tian, Z.; Fang, C. Unlocking Soybean Potential: Genetic Resources and Omics for Breeding. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2025, S1673852725000414. [CrossRef]

- Kovalskyi, S.; Koval, V. Comparison of Image Processing Techniques for Defect Detection.

- Dang, C.; Wang, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, L.; Cai, Y.; Shi, H.; Jiang, J. The Accelerated Inference of a Novel Optimized YOLOv5-LITE on Low-Power Devices for Railway Track Damage Detection. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 134846–134865. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, M.; Lingamuthu, V.; Venkatesan, C.; Perumal, S. Content-Based Image Retrieval Using Colour, Gray, Advanced Texture, Shape Features, and Random Forest Classifier with Optimized Particle Swarm Optimization. International Journal of Biomedical Imaging 2022, 2022, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ning, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, D.; Li, H.; Gao, L. Discriminating and Elimination of Damaged Soybean Seeds Based on Image Characteristics. Journal of Stored Products Research 2015, 60, 67–74. [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, A.D.; Capobiango, N.P.; da Silva, J.M.; da Silva, L.J.; da Silva, C.B.; dos Santos Dias, D.C.F. Interactive Machine Learning for Soybean Seed and Seedling Quality Classification. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 11267. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, X.; Pan, X.; Li, L. Nondestructive Classification of Soybean Seed Varieties by Hyperspectral Imaging and Ensemble Machine Learning Algorithms. Sensors 2020, 20, 6980. [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Naseem, A.; Humphries, U.W.; Hlaing, P.T.; Dechpichai, P.; Wangwongchai, A. Applications of Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review. Green Technologies and Sustainability 2025, 3, 100199. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, R.; Cao, Y.; Zheng, S.; Teng, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Du, J. Deep Learning Based Soybean Seed Classification. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 202, 107393. [CrossRef]

- Kaler, N.; Bhatia, V.; Mishra, A.K. Deep Learning-Based Robust Analysis of Laser Bio-Speckle Data for Detection of Fungal-Infected Soybean Seeds. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 89331–89348. [CrossRef]

- Sable, A.; Singh, P.; Kaur, A.; Driss, M.; Boulila, W. Quantifying Soybean Defects: A Computational Approach to Seed Classification Using Deep Learning Techniques. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1098. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Quan, L.; Li, H.; Feng, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, R. Real-Time Recognition System of Soybean Seed Full-Surface Defects Based on Deep Learning. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 187, 106230. [CrossRef]

- CHEN Siyu; ZHU Hongyuan; YU Tian; WANG Zhenxu; QIAO Rui; LIU Chunshan Research on Identifying Abnormal Soybean Grains Based on Opt-MobileNetV3. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery 2023, 54, 359–365, doi:910.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2023.S2.042.(in Chinese with English abstract).

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M. MobileViT: Light-Weight, General-Purpose, and Mobile-Friendly Vision Transformer 2022.

- Jiang, P.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Lu, N. CSMViT: A Lightweight Transformer and CNN Fusion Network for Lymph Node Pathological Images Diagnosis. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 155365–155378. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lin, Z.; Tang, S.; Lin, C.; Zhang, L.; Dong, W.; Zhong, N. Dual-Attention-Enhanced MobileViT Network: A Lightweight Model for Rice Disease Identification in Field-Captured Images. Agriculture 2025, 15, 571. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, D.; Zhang, G.; Gong, T.; Liang, Z.; Yin, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, W. Defects Detection in Metallic Additive Manufactured Structures Utilizing Multi-Modal Laser Ultrasonic Imaging Integrated with an Improved MobileViT Network. Optics & Laser Technology 2025, 187, 112802. [CrossRef]

- Rublee, E.; Rabaud, V.; Konolige, K.; Bradski, G. ORB: An Efficient Alternative to SIFT or SURF. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision; 2011; pp. 2564–2571.

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree.

- Liu, X.; Sui, Q.; Chen, Z. Real Time Weed Identification with Enhanced Mobilevit Model for Mobile Devices. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 27323. [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Zhang, J.; Liu, N.; Li, M.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yin, F. Improved MobileVit Deep Learning Algorithm Based on Thermal Images to Identify the Water State in Cotton. Agricultural Water Management 2025, 310, 109365. [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions 2017.

- Feng, Y.; Liu, C.; Han, J.; Lu, Q.; Xing, X. Identification of Wheat Seedling Varieties Based on MssiapNet. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1335194. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.R.; Singh, S.K.; Chaudhuri, B.B. Activation Functions in Deep Learning: A Comprehensive Survey and Benchmark 2022.

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module 2018.

- Ma, B.; Hua, Z.; Wen, Y.; Deng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Pu, L.; Song, H. Using an Improved Lightweight YOLOv8 Model for Real-Time Detection of Multi-Stage Apple Fruit in Complex Orchard Environments. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture 2024, 11, 70–82. [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Sun, L.; Ma, B.; Liu, R.; Liu, S.; Hu, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. TFEMRNet: A Two-Stage Multi-Feature Fusion Model for Efficient Small Pest Detection on Edge Platforms. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 4688–4703. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Soybean image acquisition platform.

Figure 1.

Soybean image acquisition platform.

Figure 3.

Image preprocessing pipeline.

Figure 3.

Image preprocessing pipeline.

Figure 4.

Segmentation algorithm workflow.

Figure 4.

Segmentation algorithm workflow.

Figure 5.

ORB Corner Detection Schematic Diagram.

Figure 5.

ORB Corner Detection Schematic Diagram.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the segmentation algorithm.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the segmentation algorithm.

Figure 7.

Demonstration of segmentation results.

Figure 7.

Demonstration of segmentation results.

Figure 8.

Soybean seed categories.

Figure 8.

Soybean seed categories.

Figure 9.

Architecture of MobileViT-SD model.

Figure 9.

Architecture of MobileViT-SD model.

Figure 10.

MobileViT module.

Figure 10.

MobileViT module.

Figure 11.

Depthwise Separable Convolution Schematic Diagram.

Figure 11.

Depthwise Separable Convolution Schematic Diagram.

Figure 12.

Transformer Architecture.

Figure 12.

Transformer Architecture.

Figure 13.

DCR structure.

Figure 13.

DCR structure.

Figure 14.

MobileViT-L module.

Figure 14.

MobileViT-L module.

Figure 15.

MV2-CBAM module.

Figure 15.

MV2-CBAM module.

Figure 16.

Accuracy and loss comparison curves.

Figure 16.

Accuracy and loss comparison curves.

Figure 17.

Confusion matrix.

Figure 17.

Confusion matrix.

Table 1.

Experimental Environment.

Table 1.

Experimental Environment.

| Test Environment |

Attributes |

| Operating System |

Windows10 |

| Graphics card |

RTX3090 |

| Processor |

Intel-i9-12900k |

| Programming languages |

Python3.8.19 |

| Deep learning frameworks |

Pytorch |

| CUDA |

11.2 |

| CUDNN |

8.1.1 |

Table 2.

Recognition Results of the Improved MobileViT-SD.

Table 2.

Recognition Results of the Improved MobileViT-SD.

| category |

Precision/% |

Recall/% |

F1-score/% |

| Broken grains |

95.69 |

98.23 |

96.94 |

| Immature grains |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

| Intact grains |

99.18 |

100.00 |

99.59 |

| Skin-damaged grains |

99.08 |

94.74 |

96.86 |

| Spotted grains |

98.04 |

99.01 |

98.52 |

| Average |

98.40 |

98.40 |

98.38 |

Table 3.

CBAM in MV2 module different embedding methods.

Table 3.

CBAM in MV2 module different embedding methods.

| Embedding Method |

Accuracy/% |

Precision/% |

Recall/% |

F1-score/% |

| None |

95.53 |

95.52 |

95.57 |

95.50 |

| Pre-expansion embedding |

97.13 |

97.07 |

97.14 |

97.08 |

| Post-expansion embedding |

98.03 |

97.99 |

98.03 |

98.00 |

| Dual embedding |

97.49 |

97.43 |

97.50 |

97.45 |

Table 4.

Comparison of Different Attention Mechanisms.

Table 4.

Comparison of Different Attention Mechanisms.

| Method |

Accuracy/% |

Precision/% |

Recall/% |

F1-score/% |

| None |

95.53 |

95.52 |

95.57 |

95.50 |

| SE |

97.13 |

97.10 |

97.18 |

97.10 |

| ECA |

97.49 |

97.45 |

97.53 |

97.47 |

| SimAM |

97.67 |

97.63 |

97.69 |

97.65 |

| CBAM |

98.03 |

97.99 |

98.03 |

98.00 |

Table 5.

Ablation Experiment Results.

Table 5.

Ablation Experiment Results.

| Model |

Factors |

Accuracy

/% |

F1-score

/% |

Model

Size/M |

| DSC |

THD |

DCR |

CBAM |

Mish |

| MobileViT |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

95.53 |

95.50 |

3.77 |

| √ |

× |

× |

× |

× |

96.78 |

96.76 |

2.82 |

| √ |

√ |

× |

× |

× |

96.42 |

96.39 |

1.77 |

| √ |

× |

√ |

× |

× |

96.60 |

96.42 |

2.93 |

| √ |

√ |

√ |

× |

× |

97.13 |

97.08 |

1.86 |

| √ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

× |

98.03 |

98.03 |

2.08 |

| √ |

√ |

× |

√ |

× |

97.50 |

97.48 |

1.99 |

| √ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

98.39 |

98.38 |

2.09 |

Table 6.

Performance Comparison with Other Models.

Table 6.

Performance Comparison with Other Models.

| Model |

Accuracy/% |

Precision/% |

Recall/% |

F1-score/% |

Model size/M |

Inference

time/ms |

| Vgg16 |

95.35 |

95.36 |

95.39 |

95.32 |

528.80 |

12.36 |

| ConvNeXt |

98.57 |

98.59 |

98.57 |

98.56 |

106.20 |

5.27 |

| ResNet50 |

98.03 |

98.01 |

98.04 |

97.91 |

96.58 |

6.53 |

| DenseNet121 |

97.14 |

97.08 |

97.17 |

97.10 |

31.02 |

7.19 |

| EfficientNetB0 |

96.42 |

96.39 |

96.45 |

96.40 |

18.46 |

3.28 |

| MoblieNetV2 |

97.32 |

97.26 |

97.35 |

97.28 |

12.60 |

2.47 |

| RegNetX-200MF |

96.06 |

96.03 |

96.10 |

96.03 |

10.41 |

1.81 |

| MoblieNetV3 |

95.17 |

95.20 |

95.21 |

95.15 |

8.51 |

1.95 |

| ShuffleNetV2 |

95.71 |

96.69 |

95.73 |

95.66 |

5.35 |

1.76 |

| MobileViT-XXS |

95.53 |

95.52 |

95.57 |

95.50 |

3.77 |

2.06 |

| MobileViT-SD |

98.39 |

98.40 |

98.40 |

98.38 |

2.09 |

1.04 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).