1. Introduction

Extracting insights from unstructured healthcare data remains one of the most time-consuming and resource-intensive stages of the healthcare data science workflow [

1]. Healthcare research environments, for example, large hospital systems and academic medical centers, generate massive volumes of heterogeneous data ranging from free-text clinical notes and research articles to imaging and laboratory results. A projection by LEK Consulting estimates that global healthcare data will grow from 2,300 EB in 2020 to around 10.8 ZB by 2025—representing an annual growth rate (CAGR) of about 36% [

2]. However, due to a lack of standardized formats and persistence of data silos across systems, data integration and analysis are challenging [

3]. In a 2025 survey of medical informatics professionals [

4], 21% identified the lack of standardized data formats, and 30% cited internal data silos as primary barriers to achieving seamless interoperability. For data scientists, these barriers manifest as prolonged data-wrangling cycles, inconsistent feature representations, and extensive effort spent reconciling domain-specific semantics before modeling can begin [

5]. Studies estimate that up to 80% of a healthcare data scientist’s time is devoted to preprocessing, profiling, and harmonizing raw datasets rather than developing or validating models [

6]. At scale, addressing these inefficiencies demands significant investment. Large corporations have reported spending billions to acquire the necessary talent, data, and infrastructure [

7].

In various healthcare contexts, data scientists must collaborate with clinicians, statisticians, and compliance teams to ensure both analytical validity and regulatory adherence. This not only delays model deployment but also heightens the risk of data leakage, misinterpretation, and non-compliance with frameworks like HIPAA [

8] and GDPR [

9]. Consequently, there is a clear need for efficient and cost-effective solutions. Solutions must be capable of handling heterogeneous healthcare data in an end-to-end workflow. By streamlining data preparation, data scientists can redirect their efforts to higher-value activities such as complex model development, rigorous evaluation, and feedback [

10].

With the advent of agentic AI, new methodologies have emerged to streamline and enhance information extraction in healthcare [

11], potentially decreasing workloads. These intelligent systems mark a shift from conventional data processing approaches by providing adaptive, context-aware capabilities [

12]. Unlike traditional machine learning pipelines, agentic AI autonomously decomposes complex tasks, dynamically selects appropriate tools and models, and iteratively refines outputs based on intermediate feedback, and can carry out many more tasks [

13]. This may enable greater robustness to data variability, improved scalability across heterogeneous data sources [

10].

We propose an agent-based system (NimbleLabs) that gives diverse stakeholders, including data scientists, healthcare experts, and practitioners, the capability to achieve three interconnected objectives. Not only may this system increase the overall efficiency of data scientists, but it could also result in health system-wide cost reductions [

13].

We define agentic AI as a role-specific, reusable software service that encapsulates a well-bounded task in the clinical data pipeline

Modular purpose: Each agent targets one core task (e.g., file classification, anonymization, modality detection).

Distinct inputs & outputs: Accepts defined inputs, performs processing, and produces deterministic outputs.

First, the framework enables comprehensive dataset understanding through automated profiling, feature identification, and support from auxiliary files, without requiring deep technical expertise. Second, it automates the enrichment of feature semantics by systematically extracting descriptive information from associated support files, eliminating the manual effort of extracting individual features. Third, it facilitates predictive model development with minimal user expertise through guided workflows and intelligent model selection, allowing users to focus on interpretation and implementation. Our system can thus create value for data scientists by enabling a streamlined, user-friendly platform aiding the derivation of insights with limited intervention [

14]. NimbleLabs can dynamically adapt to user needs, add information based on the specialty, and surface the most relevant model based on the dataset. We evaluate our architecture on multi-modal datasets consisting of both structured (tabular) and unstructured (image) raw data. Furthermore, we demonstrate how the coordinated operation of the agents enables data scientists to obtain contextually relevant insights.

2. Literature Review

2.1. AI in Healthcare Systems

2.1.1. Insights from Academia

Several studies have developed systems to extract insights from complex, heterogeneous datasets. Examples include opioid monitoring, depression prediction, and EHR analysis [

15,

16,

17,

18], using methods such as AutoML [

19], Perpetual Booster [

20], and other machine learning techniques for tasks like risk assessment, drug usage prediction, and practitioner recommendations. While effective, these methods function as isolated pipelines and can require extensive manual oversight for data preparation, feature engineering, model selection, and refinement [

14]. Moreover, these solutions cannot carry out autonomous, context-aware tasks for the entire workflow. Given rising healthcare costs and inefficiencies, there is a need to create systems that can ingest heterogeneous healthcare data, perform automated and semantic enrichment, predictive models, and iteratively improve outputs based on intermediate results—all with limited human intervention.

2.1.2. Industry Solutions

Various commercial systems have been developed to streamline healthcare documentation, prescribing, and patient data management [

21,

22,

23]. Epic Systems’ scribe tool [

24] leverages AI to generate patient prescriptions based on clinical workflows and drive medication adherence, satisfaction, and efficiency. Abridge [

21] focuses on real-time clinical conversation transcription and summarization, allowing physicians to capture key visit details without diverting attention from patient interactions. Similarly, Veradigm’s ePrescribe [

22] optimizes medication management by integrating prescription workflows with clinical decision support, helping reduce errors and improve prescribing efficiency. In addition, solutions like Smart Profile from Smart EHR [

23] are cloud-based electronic health record (EHR) software for advanced workflow automation in opioid treatment programs. These tools collectively reduce administrative workload, enhance the accessibility of critical information, and improve the accuracy of patient records. By automating key steps in the clinical documentation and data integration process, these solutions enable healthcare professionals to focus more on direct patient care.

While these advances provide clear benefits for clinical operations, they are not necessarily designed to meet the needs of data scientists working with healthcare data [

4]. Optimized for point-of-care efficiency and clinician usability, they often produce outputs formatted for human readability and billing needs, rather than machine-ready, structured datasets [

24]. Moreover, these tools rarely integrate seamlessly with analytical pipelines, forcing additional wrangling to align outputs with modeling requirements, reintroducing the very preprocessing burden they seek to reduce [

25]. This mismatch between clinical-facing AI tools and data science workflows can lead to inefficiencies, data quality issues, and reduced trust in outputs for research and predictive modeling [

22].

2.2. Agentic AI in Healthcare

2.2.1. Insights from Academia

Recent advances in agentic AI have shown considerable promise in healthcare applications, with multiple studies investigating the use of multi-modal agent systems. For example, Huang et al. [

26] present a comprehensive framework for AI agents in clinical settings, highlighting their ability to process diverse data modalities and adapt dynamically to varied clinical contexts. Building on this, Schmidgall et al. [

27] introduce AgentClinic, a multi-agent system designed to facilitate patient interactions and systematically collect incomplete clinical information. Their work demonstrates how agentic AI can address persistent challenges of missing or fragmented data in clinical environments by deploying specialized agents that identify information gaps and guide targeted data collection strategies. While prior studies [

28,

29,

30] have demonstrated the utility of agentic AI in patient-facing applications, they have not adequately explored how autonomous agents could facilitate tasks such as data profiling, feature engineering, model selection, and results interpretation within medical contexts. Similarly, Shimgekar et al. [

31] showcase the potential of agent-based approaches across individual stages of the clinical ML pipeline. Yet, these contributions remain fragmented, addressing isolated components rather than offering an integrated solution.

2.2.2. Industry Solutions

Several commercial implementations have emerged that further validate the utility of agentic AI in healthcare. Kairo Health [

32] has developed agent-based systems that focus on patient engagement and care coordination. In contrast, MentalHappy [

33] demonstrates the application of agentic AI for mental health support and patient communication. Additionally, Trapeze [

34] employs agentic AI to facilitate patient-practitioner connections by developing agents capable of responding to patient calls. It mimics the communication style and voice characteristics of specific medical practitioners to make the conversation personalized. Similarly, Avelis Health [

35] leverages AI agents for comprehensive medical claims. Avelis Health carries out pre-payment verification systems to prevent fraudulent claims and post-payment analysis to identify billing discrepancies and ensure compliance with healthcare regulations.

Existing research and commercial healthcare agentic AI primarily focus on clinical operations such as patient engagement, documentation, and workflow management rather than supporting end-to-end data science workflows. While effective for clinicians, these solutions often do not produce machine-ready, annotated datasets, limiting dataset use for modeling. This forces data scientists to reprocess and restructure outputs [

25]. Our proposed agentic AI framework is purpose-built for healthcare data science, emphasizing better data preprocessing, data interpretation, and model building through machine learning pipelines while addressing the complexity of healthcare data. By delivering context-aware, analysis-ready outputs, we can reduce preprocessing burdens, enhance reproducibility, and directly support core tasks such as data understanding, feature engineering, and model development capabilities absent in current solutions.

3. Data

Tabular data was obtained from Hospice and Palliative Care Evaluation (HOPE) [

36]. This dataset represents inpatient or outpatient hospice and palliative care service visits. The resulting model in our pipeline classifies patient anxiety levels. For the image data pipeline, we used the dataset in [

37], which provides an annotated compilation of three publicly available sources: the CVC-ColonDB dataset [

38], the GLRC dataset [

39], and the KUMC dataset, comprising 80 colonoscopy video sequences from the University of Kansas Medical Center. The resulting model in our pipeline detects and classifies hyperplastic vs. adenomatous polyps in colonoscopy images.

4. Workflow

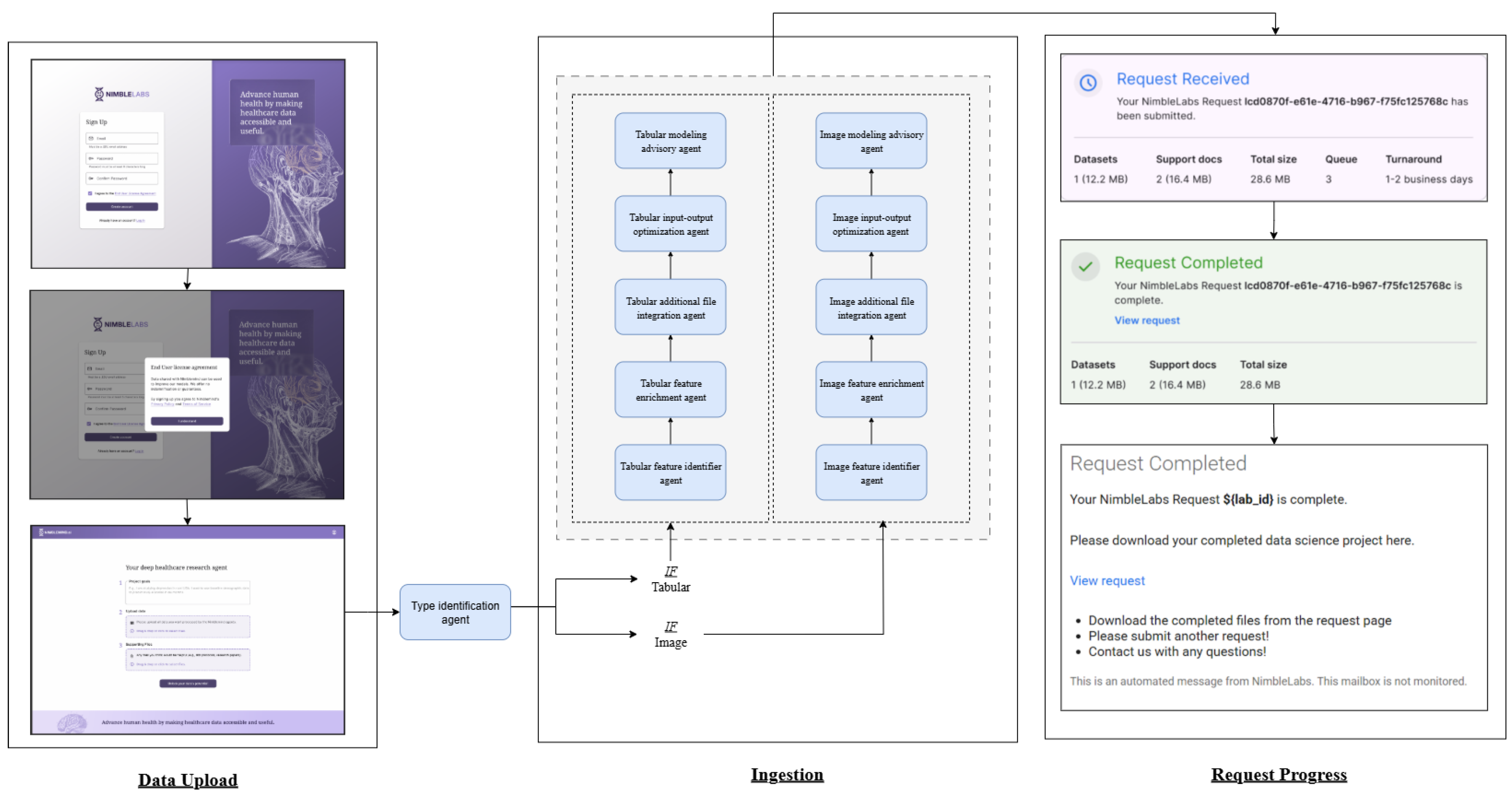

The workflow diagram in

Figure 1 illustrates the frontend and backend components. The frontend (left) displays the NimbleLabs interface. The process begins with the sign-up page, where the user enters an email address and password, followed by acceptance of the user license agreement. The user then uploads the data, specifies the project goals, and provides any supporting files. Once submitted, the backend processes the request. The data is first analyzed by agents that classify it into tabular and image formats using the type identification agent. Tabular data processing involves a type identification agent, followed by a column enrichment agent, an additional file integration agent, an input-output agent, and concludes with the advisory tabular agent. A similar sequence is applied to image data, which first identifies the image feature using the image identification agent, followed by the image advisory agent. Upon completion, the system presents a confirmation indicating that the request has been processed.

5. Proposed Agentic Pipeline

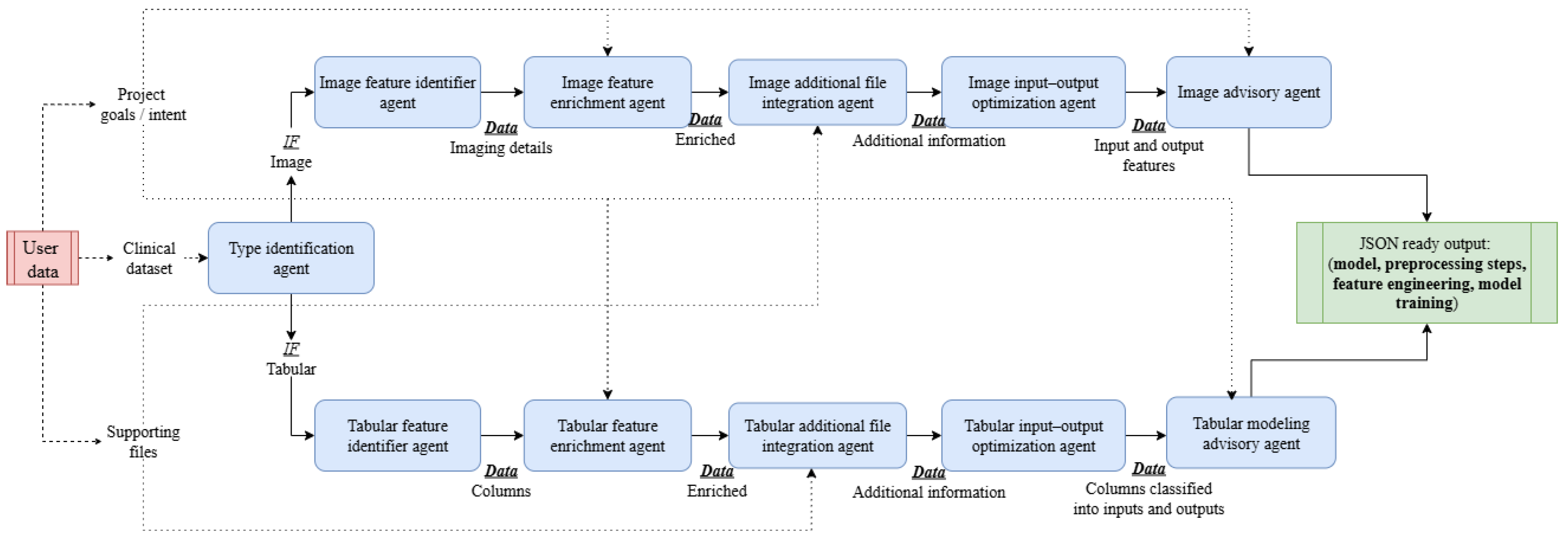

NimbleLabs leverages a multi-agent architecture comprising six specialized agents that collaboratively interact to address complex tasks, including providing model specifications, executing preprocessing routines, and other operations. An overview of the complete pipeline, illustrating the interactions among all agents and the flow of data, is presented in

Figure 2. A summary of all the agents with their description is shown in

Table 1.

5.1. Type Identification Agent

The type identification agent functions as an autonomous file and data classification module that detects and categorizes heterogeneous data formats, including CSV, JSON, XML, and compressed archives. Using the Magika library, it identifies MIME types for both individual files and extracted contents from ZIP archives, distinguishing between tabular and image-based data. When image data is detected, the agent triggers anonymization routines, while tabular files undergo automated de-identification. The agent outputs the detected MIME type along with file size metrics, enabling downstream processing pipelines to apply format-specific analytical workflows.

5.2. Feature Identification Agent

The feature identification agents are responsible for extracting structured information from both tabular and image data sources. For medical imaging, the

image feature identifier agent employs a vision language model (VLM), which uses Google’s MedGemma [

40] to perform automated, modality-aware interpretation. Google’s MedGemma is an open-source suite of multimodal AI models designed to understand medical text and images. We chose it for its ability to perform clinical reasoning, image classification, and medical report generation, closely related to our use case. It supports diverse image types, including radiographs, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), histopathology slides, etc. The agent determines the imaging modality, localizes relevant anatomical regions, and identifies both normal structures and pathological findings of clinical significance. Structured outputs are then generated in a machine-readable format, capturing modality, anatomical context, and salient observations. For medical images, these descriptions enable direct integration into diagnostic workflows. For non-medical images, concise categorical labels are produced to preserve dataset integrity. An illustrative example for a colonoscopic image is shown below, where the system identifies the presence of multiple polyps.

{

"data description": "This image is a

colonoscopy view showing multiple

polyps in the colon."

}

For tabular datasets, the tabular feature identifier agent systematically enumerates all available columns, enabling downstream agents to perform schema-aware processing and semantic enrichment. An illustration showing the extracted columns from the data for anxiety prediction is shown below.

{

"data description": ["age", "gender",

..., "tension"]

}

Table 1.

Agent overview

|

Agent |

Purpose and Functionality |

| Type identification agent |

Detects data modality, structured (tabular) or unstructured (image) using Magika, so data-specific downstream workflows can be used. |

|

Feature identification agent |

Extracts the features from the data, columns for tabular and image modality for image data. |

| Feature enrichment agent |

Enriches the feature by adding additional keywords based on user intent |

|

Additional file integration agent |

Adds more context to each feature based on the additional files uploaded by the user. |

| Input-output optimization agent |

Based on the feature descriptions and user intent, finds the most optimal input-output feature set. |

|

Modeling advisor agent |

Based on feature description, input-output set, and user intent, recommends details of the appropriate machine learning model to use, a set of hyperparameters, preprocessing steps, etc. |

5.3. Feature Enrichment Agent

The feature enrichment agents perform automated semantic augmentation of dataset features to enhance interpretability, searchability, and downstream analytic potential. This capability applies to both image and tabular datasets, where the term feature refers to a semantically significant element in an image or a column name in structured data. For image datasets, the image feature enrichment agent augments visual features extracted by upstream interpretation models with semantically rich vocabularies. Using the google.adk.agents.Agent framework in conjunction with the gemini-2.0-flash model, the agent processes a list of feature names along with a user-defined project_goal to produce at least five highly relevant terms per feature. In the medical imaging domain, for example, a colonoscopic image containing polyps may yield features such as “polyps” which are then expanded into context-aware sets of related terms, morphological descriptors, and clinically relevant synonyms. This enriched representation supports enhanced retrieval of relevant information about the feature from the supporting document. An example of such an enrichment is shown below:

{

"polyps": [

"colonic polyp",

"adenomatous polyp",

"sessile polyp",

"pedunculated polyp",

"precancerous lesion"]

}

For structured datasets, the tabular feature enrichment agent applies a similar process to feature names, expanding each into a set of contextually relevant keywords. An example for two features, “age” and “gender,” is shown below:

{

"age": [

"years",

"age of patient",

"patient age",

"age at diagnosis",

"age group"

],

"gender": [

"sex",

"male",

"female",

"gender identity",

"Masculino",

"Femenino"

]

}

5.4. Additional File Integration Agent

The additional file integration agents serve as data fusion components that enhance dataset features—whether derived from image or tabular sources—by incorporating supplementary content from external support files such as PDF-based codebooks, data dictionaries, or reference manuals. These agents ensure that each feature is accompanied by relevant contextual information, improving interpretability. For image datasets, the

image additional file integration agent uses the names of extracted visual features and their enriched keyword vocabularies to retrieve supplementary details from external resources. For example, in a colonoscopic image annotated with “polyps” the system may locate corresponding definitions, clinical guidelines, or descriptive passages from supporting documents. The integration process begins by segmenting support files into overlapping windows of 200 words, followed by preprocessing steps such as stopword removal, lemmatization, and stemming. These windows are then embedded using the

all-MiniLM-L6-v2 sentence transformer model to generate 384-dimensional semantic vectors. Feature keywords are similarly embedded, and cosine similarity [

41] is applied to identify the top 5 most relevant windows. In parallel, a keyword-driven extraction module [

42] searches for enriched keywords directly within the document windows and chooses the ones where at least one of the keywords is present. The outputs from both methods are merged and summarized using the

gemini-2.0-flash model to produce concise, context-specific descriptions. An example for an image-based feature integration is shown below:

{

"polyps": "Polyps are abnormal tissue

growths protruding from the mucosal

surface of the colon. Some types, such

as adenomatous polyps, carry a risk of

malignant transformation.",

}

For tabular datasets, the tabular additional file integration agent applies the same hybrid extraction pipeline to textual features. An example for two tabular features, “age” and “gender,” is shown below:

{

"age": "The study used anonymized data

of adult patients from palliative care

services in Germany.",

"gender": "The study sample consisted

of 9924 patients, with just over half

being female (51.9%) and 47.3% being

male. There were 0.8% missing values

for gender. Female gender had a beta

value of 0.312, odds ratio of 1.36

(1.21, 1.55), and p-value of less than

0.0001, with male as the reference."

}

5.5. Input–Output Optimization Agent

The input–output optimization agents determine the most appropriate division of dataset features into predictive inputs and target outputs, enabling streamlined integration into machine learning workflows. This process applies to both image-derived and tabular features, leveraging feature descriptions generated by the additional file integration agents in conjunction with the user-defined project goal. For image datasets, the image input–output optimization agent evaluates enriched visual features and their contextual metadata to identify which characteristics should be treated as predictive variables and which correspond to the target outcome. For example, in a colonoscopic imaging dataset, where the user intent is to find the exact location of cancer in the colon, features such as “polyps” may serve as inputs, while a bounding box around “presence of colorectal cancer” could be designated as the output. The analysis is performed using the gemini-2.0-flash model. Results are returned in a structured JSON format, as shown below:

{

"input": [

"polyps"],

"output": ["colorectal cancer

diagnosis"]

}

For tabular datasets, the tabular input–output optimization agent applies the same principle to structured feature sets. By analyzing each feature’s integrated description, the system automatically classifies variables into inputs and outputs in a manner consistent with the specified project objective. An example for a tabular dataset is presented below, where the user intent is to predict anxiety:

{

"input": [

"age",

"gender",

...

"tension"

],

"output": ["anxiety"]

}

5.6. Modeling Advisory Agent

The modeling advisory agents provide context-aware, end-to-end guidance for designing optimized machine learning pipelines across both image and tabular datasets. Leveraging the structured outputs from preceding agents and the user-defined project goal, these agents determine appropriate modeling strategies tailored to the dataset characteristics and analytical objectives. For image datasets (image modeling advisory agent), the agent interprets visual feature descriptions to identify the most suitable computer vision task, such as classification, detection, or segmentation. For tabular datasets (tabular modeling advisory agent), it analyzes structured features and their designated input–output roles to recommend predictive modeling approaches. In both cases, the guidance encompasses optimal model architectures, preprocessing steps, feature handling or engineering techniques, and comprehensive training protocols. Recommendations include considerations for loss functions, optimization methods, data augmentation, regularization strategies, hyperparameter tuning, and evaluation metrics. The outputs are returned in a validated, structured JSON format to ensure reproducibility and facilitate direct integration into automated pipelines, as shown below:

{

"model": "Various model suggestions

based on data",

"preprocessing": "Various preprocessing

steps for the data",

"feature_engineering": "feature

engineering techniques to

improve model training",

"model_training": "Loss Function,

Hyperparameter Tuning, Regularization,

Evaluation Metrics",

"data": "input: [input features],

output: [output features]"

}

6. Implementation

The complete multi-agent system is packaged within a containerized environment to ensure reproducibility, portability, and efficient scaling. All source code, dependencies, and configuration files are built into a Docker image, which is subsequently deployed to Google Cloud Run. This serverless deployment model enables automatic scaling in response to incoming requests while eliminating the need for manual infrastructure management.

Once deployed, Cloud Run provides a secure endpoint URL that serves as the system’s primary API interface. Users interact with the API by sending a POST request to this endpoint, including three essential parameters in the request payload: the user’s analytical intent, a signed URL to the dataset stored in a Google Cloud Storage bucket, and a signed URL to any supporting documentation such as data dictionaries, metadata files, or imaging protocols. These signed URLs provide time-bound, secure access to the required resources without exposing them publicly.

When the API receives a request, it retrieves the specified files, interprets them in the context of the user’s intent, and processes them through the appropriate sequence of agents in the pipeline. The system then returns a structured JSON output containing all relevant recommendations, analyses, and modeling strategies generated by the agents.

7. Discussion

The primary scientific contribution of this work is the establishment of a comprehensive, domain-specific agent ecosystem capable of processing both structured tabular datasets and unstructured imaging data through specialized and interoperable pipelines. The deployment of our multi-agent medical data processing framework represents a significant advancement in healthcare analytics infrastructure, with the potential to meaningfully accelerate the translation of healthcare data into actionable clinical and research insights. By integrating modular agents capable of automated data type identification, semantic enrichment, and optimal model selection, the system directly addresses a persistent bottleneck in the medical AI adoption pipeline: The dependence on scarce technical expertise [

43]. In operational terms, this reduction in the time and skill required to prepare datasets for advanced analytics can lead to measurable efficiency gains. For example, preliminary internal benchmarking indicates that workflows traditionally requiring several hours of expert labor can be completed within minutes, potentially reducing operational costs by up to 22% [

44] and shortening project initiation timelines by a factor of 10 [

45].

From a market perspective, our approach aligns with trends seen in commercially available AI development environments such as Google’s Vertex AI and Amazon SageMaker, but distinguishes itself through its explicit specialization in multimodal healthcare data and its ability to ingest heterogeneous datasets through a unified API [

46,

47]. While comparable platforms often require manual feature engineering or bespoke preprocessing pipelines, our architecture delivers end-to-end suggestions, thereby lowering barriers for institutions without dedicated machine learning engineering teams [

48,

49].

7.1. Limitations and Future Work

While the proposed framework demonstrates strong applicability across medical modalities, several limitations remain that temper its immediate universality. First, the system’s reliance on large language model APIs introduces infrastructure dependencies that may constrain adoption in resource-limited clinical environments [

50]. Second, the current instantiation is optimized for static datasets, and does not yet accommodate real-time ingestion, streaming analytics, or continuous model retraining—all critical features for deployment in time-sensitive clinical monitoring or public health surveillance contexts. Lastly, although semantic enrichment partially mitigates the challenge of cross-domain variability, the framework has yet to be comprehensively validated across the full spectrum of medical subdomains, particularly those with sparse data availability [

51], such as rare disease registries (Huntington’s Disease, Gaucher Disease, Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH), etc.) or niche imaging modalities (Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) for Rare Ophthalmic Disorders, PET-MRI Fusion for Neurodegenerative Diseases, etc.).

Future development efforts will focus on (i) integrating incremental learning to accommodate evolving datasets without catastrophic forgetting [

52], (ii) improving computational efficiency to enable inference on lower-specification hardware, (iii) expanding the modality portfolio to include genomics, multi-omics, and continuous wearable sensor streams and (iv) large-scale benchmarking across geographically and institutionally diverse healthcare systems is planned to evaluate the platform’s robustness and generalizability. Addressing these dimensions will position the framework not only as a technical innovation but as a commercially viable, domain-agnostic solution capable of transforming medical AI deployment strategies globally.

7.2. Ethical Considerations

The deployment of our multi-agent medical data processing framework necessitates careful attention to ethical considerations, including privacy, bias, and explainability. Automated aggregation and processing of sensitive medical data require strict adherence to regulations such as HIPAA and GDPR, with techniques like differential privacy and secure data handling to protect patient confidentiality [

53]. To mitigate potential bias, representative datasets and systematic bias detection and correction mechanisms must be employed, ensuring equitable outcomes across populations [

54]. Additionally, the complexity of AI-driven decisions underscores the need for explainable AI (XAI) approaches, enabling clinicians to interpret and validate model outputs transparently [

55]. By integrating these safeguards, the framework can balance efficiency and automation with responsible, ethical deployment in medical contexts.

References

- Rajpurkar, P.; Chen, E.; Banerjee, O.; Topol, E.J. AI in health and medicine. Nature medicine 2022, 28, 31–38.

- L.E.K. Consulting. Tapping Into New Potential: Realising the Value of Data in the Healthcare Sector. https://www.lek.com/insights/hea/eu/ei/tapping-new-potential-realising-value-data-healthcare-sector, 2023. Between 2020 and 2025, the total amount of global healthcare data is projected to increase from 2,300 to 10,800 exabytes, representing a CAGR of 36%.

- Schmetz, A.; Kampker, A. Inside Production Data Science: Exploring the Main Tasks of Data Scientists in Production Environments. AI 2024, 5, 873–886.

- Newswire. Medical Reports (newswire). https://www.newswire.com/news/ai-and-interoperability-trends-black-books-amia-membership-survey-22531347#:~:text=Interoperability%20remains%20a%20persistent%20challenge,sharing%20obstacles/, 2024. Medical reports from newswire about data challenges.

- Aggarwal, R.; Sounderajah, V.; Martin, G.; Ting, D.S.; Karthikesalingam, A.; King, D.; Ashrafian, H.; Darzi, A. Diagnostic accuracy of deep learning in medical imaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ digital medicine 2021, 4, 65.

- Lund, S.; Manyika, J.; Segel, L.H.; Dua, A.; Rutherford, S.; Hancock, B.; Macon, B. The Future of Work in America: People and Places, Today and Tomorrow; McKinsey Global Institute, 2019.

- Centene. Centene Reports. https://www.globaldata.com/store/report/centene-corporation-enterprise-tech-analysis/, 2024. Centene corporation analysis of technology.

- U.S. Congress. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/laws-regulations/index.html, 2025.

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). https://gdpr-info.eu/, 2016. Regulation (EU) 2016/679.

- Healthcare AI. Healthcare AI. https://www.salesforce.com/healthcare-life-sciences/healthcare-artificial-intelligence/healthcare-agentic-ai/#:~:text=Enter%20agentic%20artificial%20intelligence%20,outcomes%20and%20reduce%20healthcare%20costs, 2024. Accessed: 2025-07-17.

- Kocak B, M.I. AI agents in radiology: Toward autonomous and adaptive intelligence 2025.

- Acharya, D.B.; Kuppan, K.; Divya, B. Agentic ai: Autonomous intelligence for complex goals–a comprehensive survey. IEEe Access 2025.

- Agent AI. Benefits of Agent AI. https://www.wwt.com/blog/agentic-ai-strategic-value-and-high-impact-use-cases-for-healthcare-systems, 2025. Accessed: 2025-07-17.

- Moazemi, S.; Vahdati, S.; Li, J.; Kalkhoff, S.; Castano, L.J.; Dewitz, B.; Bibo, R.; Sabouniaghdam, P.; Tootooni, M.S.; Bundschuh, R.A.; et al. Artificial intelligence for clinical decision support for monitoring patients in cardiovascular ICUs: A systematic review. Frontiers in Medicine 2023, 10, 1109411.

- Elhaddad, M.; Hamam, S. AI-driven clinical decision support systems: An ongoing pursuit of potential. Cureus 2024, 16.

- Kumar, P.; Chauhan, S.; Awasthi, L.K. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Review, ethics, trust challenges & future research directions. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 120, 105894.

- Goyal, A.; Parekh, N.; Yin Cheung, L.; Saha, K.; L Altice, F.; O’hanlon, R.; Ho Chun Man, R.; Fong, C.; Poellabauer, C.; Guarino, H.; et al. Predicting Opioid Use Outcomes in Minoritized Communities. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology, and Health Informatics, 2023, pp. 1–2.

- Goyal, A.; Ho Chun Man, R.; Lee, R.K.W.; Saha, K.; L. Altice, F.; Poellabauer, C.; Papakyriakopoulos, O.; Yin Cheung, L.; De Choudhury, M.; Allagh, K.; et al. Using Voice Data to Facilitate Depression Risk Assessment in Primary Health Care. In Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 16th ACM Web Science Conference, New York, NY, USA, 2024; Websci Companion ’24, p. 17–18. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhao, K.; Chu, X. AutoML: A survey of the state-of-the-art. Knowledge-based systems 2021, 212, 106622.

- Booster, P. Perpetual Booster. https://perpetual-ml.com/blog/how-perpetual-works/, 2022. Accessed: 2025-07-17.

- Abridge Solutions. Abridge Solutions. https://www.abridge.com/abridge-contextual-reasoning-engine/, 2024. Accessed: 2025-08-14.

- Verdigm Eprescribe. Verdigm Eprescribe. https://veradigm.com/eprescribe//, 2024. Accessed: 2025-08-14.

- Smart Profile. Smart Profile. https://www.softwareadvice.com/medical/smart-profile/, 2024. Accessed: 2025-08-14.

- Systems, E. Epic Systems (scribe). https://www.epic.com/software/ai-clinicians/, 2024. Accessed: 2025-07-17.

- Oracle Health. Oracle Health. https://www.oracle.com/health/clinical-suite/clinical-ai-agent/, 2024. Accessed: 2025-08-14.

- Huang, K. AI Agents in Healthcare. In Agentic AI: Theories and Practices; Springer, 2025; pp. 303–321.

- Schmidgall, S.; Ziaei, R.; Harris, C.; Reis, E.; Jopling, J.; Moor, M. AgentClinic: A multimodal agent benchmark to evaluate AI in simulated clinical environments. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.07960 2024.

- Zhu, Y.; Ren, C.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Xie, S.; Feng, J.; Zhu, X.; Li, Z.; Ma, L.; Pan, C. Emerge: Enhancing multimodal electronic health records predictive modeling with retrieval-augmented generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, 2024, pp. 3549–3559.

- Asthana, S.; Mahindru, R.; Zhang, B.; Sanz, J. Adaptive PII Mitigation Framework for Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12465 2025.

- Neupane, S.; Mittal, S.; Rahimi, S. Towards a hipaa compliant agentic ai system in healthcare. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.17669 2025.

- Shimgekar, S.R.; Vassef, S.; Goyal, A.; Kumar, N.; Saha, K. Agentic AI framework for End-to-End Medical Data Inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.18115 2025.

- Kairo Health Website. YCombinator, 2024. Accessed: 2024-08-12.

- Mental Happy website. YCombinator, 2024. Accessed: 2024-08-12.

- Trapeze website. YCombinator, 2024. Accessed: 2024-08-12.

- Avelis Health. YCombinator, 2024. Accessed: 2024-08-12.

- Hofmann, S.; Hess, S.; Klein, C.; Lindena, G.; Radbruch, L.; Ostgathe, C. Patients in palliative care—Development of a predictive model for anxiety using routine data. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Fathan, M.I.; Patel, K.; Zhang, T.; Zhong, C.; Bansal, A.; Rastogi, A.; Wang, J.S.; Wang, G. Colonoscopy polyp detection and classification: Dataset creation and comparative evaluations. Plos one 2021, 16, e0255809.

- Bernal, J.; Sánchez, J.; Vilarino, F. Towards automatic polyp detection with a polyp appearance model. Pattern Recognition 2012, 45, 3166–3182.

- Mesejo, P.; Pizarro, D.; Abergel, A.; Rouquette, O.; Beorchia, S.; Poincloux, L.; Bartoli, A. Computer-aided classification of gastrointestinal lesions in regular colonoscopy. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 2016, 35, 2051–2063.

- Yang, L.; Sellergren, A.; Golden, D.; et al. MedGemma Technical Report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.05201 2025. Accessed: 2025-07-17.

- Xia, P.; Zhang, L.; Li, F. Learning similarity with cosine similarity ensemble. Information sciences 2015, 307, 39–52.

- Jiang, K.; Jin, G.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, R.; Zhao, Y. Incorporating external knowledge for text matching model. Computer Speech & Language 2024, 87, 101638.

- Hemmer, P.; Schemmer, M.; Riefle, L.; Rosellen, N.; Vössing, M.; Kühl, N. Factors that influence the adoption of human-AI collaboration in clinical decision-making. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.09082 2022.

- Luo, Y.; Shi, L.; Li, Y.; Zhuang, A.; Gong, Y.; Liu, L.; Lin, C. From intention to implementation: Automating biomedical research via LLMs. Science China Information Sciences 2025, 68, 1–18.

- Urbanowicz, R.J.; Bandhey, H.; Keenan, B.T.; Maislin, G.; Hwang, S.; Mowery, D.L.; Lynch, S.M.; Mazzotti, D.R.; Han, F.; Li, Q.Y.; et al. Streamline: An automated machine learning pipeline for biomedicine applied to examine the utility of photography-based phenotypes for osa prediction across international sleep centers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.05461 2023.

- Das, P.; Ivkin, N.; Bansal, T.; Rouesnel, L.; Gautier, P.; Karnin, Z.; Dirac, L.; Ramakrishnan, L.; Perunicic, A.; Shcherbatyi, I.; et al. Amazon SageMaker Autopilot: A white box AutoML solution at scale. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the fourth international workshop on data management for end-to-end machine learning, 2020, pp. 1–7.

- Google Cloud. Google Cloud Enhances Vertex AI Search for Healthcare with Multimodal AI. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/google-cloud-enhances-vertex-ai-search-for-healthcare-with-multimodal-ai-302388639.html, 2023. Describes Vertex AI support for multimodal healthcare data and the need for manual preprocessing in some cases.

- Google Cloud. Vertex AI Generative AI Models Documentation. https://cloud.google.com/vertex-ai/generative-ai/docs/models, 2023. Outlines Vertex AI deployment and management tools and the requirement for custom pipelines in specialized healthcare applications.

- Amazon Web Services. Automate Feature Engineering Pipelines with Amazon SageMaker. https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/machine-learning/automate-feature-engineering-pipelines-with-amazon-sagemaker/, 2023. Describes SageMaker tools for data preparation and feature engineering, highlighting manual intervention for complex healthcare datasets.

- Dennstädt, F.; Hastings, J.; Putora, P.M.; Schmerder, M.; Cihoric, N. Implementing large language models in healthcare while balancing control, collaboration, costs and security. NPJ digital medicine 2025, 8, 143.

- Gisslander, K.; Mohammad, A.J.; Vaglio, A.; Little, M.A. Overcoming challenges in rare disease registry integration using the semantic web-a clinical research perspective. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2023, 18, 253.

- Yavari, S.; Furst, J. Mitigating Catastrophic Forgetting in the Incremental Learning of Medical Images. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.20033 2025.

- Torkzadehmahani, R.; Nasirigerdeh, R.; Blumenthal, D.B.; Kacprowski, T.; List, M.; Matschinske, J.; Spaeth, J.; Wenke, N.K.; Baumbach, J. Privacy-preserving artificial intelligence techniques in biomedicine. Methods of information in medicine 2022, 61, e12–e27.

- Hasanzadeh, F.; Josephson, C.B.; Waters, G.; Adedinsewo, D.; Azizi, Z.; White, J.A. Bias recognition and mitigation strategies in artificial intelligence healthcare applications. NPJ Digital Medicine 2025, 8, 154.

- Mienye, I.D.; Obaido, G.; Jere, N.; Mienye, E.; Aruleba, K.; Emmanuel, I.D.; Ogbuokiri, B. A survey of explainable artificial intelligence in healthcare: Concepts, applications, and challenges. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2024, 51, 101587.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).