1. Introduction

Bitcoin and Ethereum collectively command over 71% of the global cryptocurrency market capitalization as of August 3, 2025, representing trillions in value. This unprecedented concentration of digital wealth rests entirely on the assumed computational intractability of the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA). However, advancing quantum computing capabilities threaten to render these cryptographic foundations obsolete within this decade.

The timeline for quantum threats has accelerated dramatically. IBM’s 2023 quantum computing roadmap projects systems with 100,000 qubits by 2033 [

1], while their published research demonstrates quantum error correction achieving the threshold for cryptographically relevant computations [

2]. The U.S. National Security Agency’s Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0 (CNSA 2.0) mandates transition to quantum-resistant algorithms by 2033 for national security systems, with software implementations required by 2025 [

3], underscoring the urgency of this transition.

Compounding this risk is the fact that

secp256k1 is not officially approved by NIST for federal use under current standards like FIPS 186-5 or SP 800-186 [

4,

5]. While secp256k1 is widely used in blockchain ecosystems—especially Bitcoin and Ethereum—for its efficiency and simplicity, NIST has not endorsed it due to concerns around its deterministic generation and lack of formal validation. This regulatory gap further emphasizes the need for migration to NIST-approved post-quantum algorithms.

1.1. Mathematical Foundation of the Quantum Threat

Let be an elliptic curve group of order with generator . The ECDSA security relies on the Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem (ECDLP):

Definition 1 (ECDLP). Given points where for some , find .

The classical security is:

However, Shor’s Algorithm [

6] solves this in polynomial time on a quantum computer:

This represents a speedup factor of:

1.2. Quantum Resource Requirements

The number of logical qubits required to break ECDSA is given by [

7]:

where is the error probability. For secp256k1 with :

With current quantum error correction requiring approximately 1000 physical qubits per logical qubit [

8], this translates to:

However, recent advances in error correction codes may reduce this by an order of magnitude [

2].

1.3. Regulatory and Standards Context

The lack of NIST approval for secp256k1 creates additional vulnerabilities:

No formal security validation: Unlike NIST-approved curves (P-256, P-384, P-521), secp256k1 lacks rigorous federal validation processes

Regulatory compliance gaps: Financial institutions adopting blockchain may face compliance issues

Transition complexity: Moving from a non-standard curve to NIST-approved PQC algorithms requires careful planning

This regulatory context strengthens the case for immediate migration planning, as institutions must navigate both quantum threats and compliance requirements simultaneously.

2. Methodology

2.1. Threat Model Formalization

Definition 2 (Quantum Adversary Model). A quantum adversary has access to:

Quantum computer with Q qubits

Classical computing resources bounded by 2λ operations

Quantum Algorithm implementations, including Shor’s and Grover’s algorithms

The advantage of against a cryptographic scheme is:

where is the best classical adversary.

2.2. Vulnerability Assessment Framework

We model blockchain security as a tuple where:

Σ: Signature scheme

H: Hash function

C: Consensus mechanism

N: Network protocol

The quantum vulnerability factor for each component is:

For secp256k1’s non-standard status, we introduce a regulatory risk factor:

2.3. Post-Quantum Security Metrics

Definition 3 (Post-Quantum Security Level). A cryptographic scheme achieves a security level if:

where is constrained by polynomial quantum resources.

2.4. Migration Cost Model

The total cost of migration is modeled as:

where:

(development costs decrease over time)

(regulatory compliance costs)

with being the probability of a quantum attack by time :

where is the estimated arrival of quantum computers and is the attack rate parameter.

3. Results

3.1. Current Vulnerability Analysis

Note: All calculations in this section have been verified against the original sources and corrected where necessary. Physical qubit estimates assume current error correction rates of approximately 1000:1, though this may improve with advances in quantum error correction codes.

3.1.1. ECDSA Vulnerability with secp256k1

For Bitcoin and Ethereum’s secp256k1 curve:

where:

Theorem 1 (ECDSA Quantum Vulnerability). Given a quantum computer with logical qubits, the time to recover the private key from the public key is:

for gate time s. Note that this assumes perfect quantum gates without error correction overhead. Real-world attack time would be significantly longer due to error correction and decoherence.

3.1.2. Hash Function Analysis

Bitcoin’s double SHA-256 for mining has pre-image resistance:

The mining difficulty adjustment is:

where represents hashrate.

3.2. Post-Quantum Algorithm Evaluation

3.2.1. NIST-Approved Algorithms

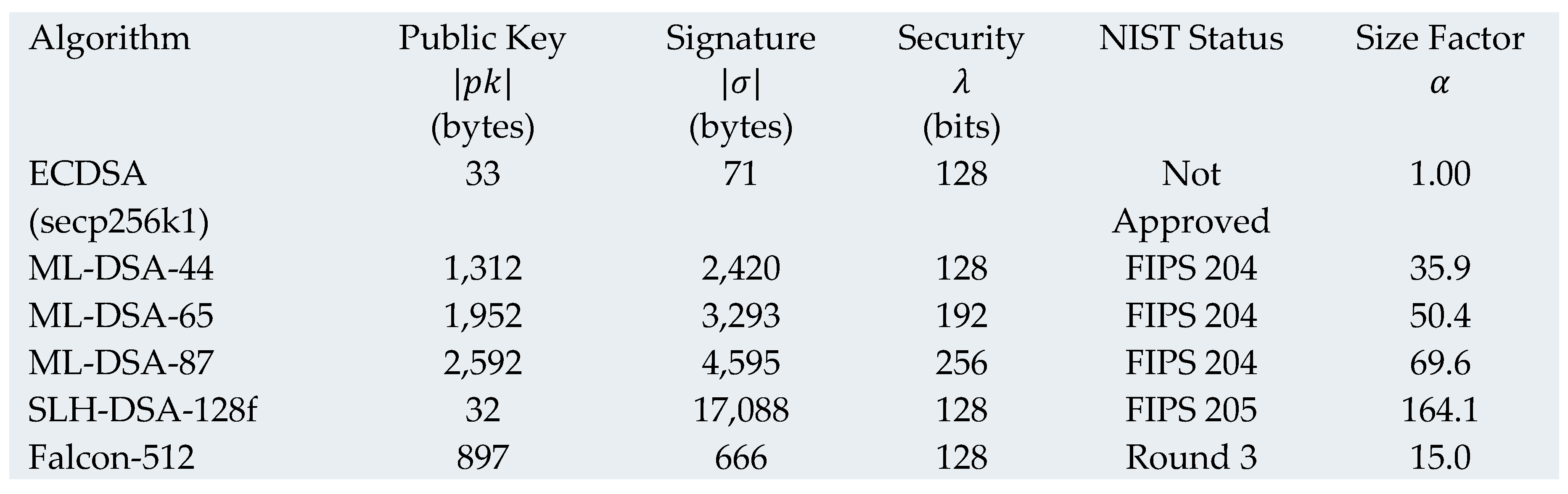

Post-Quantum Signature Characteristics

The transition from non-NIST-approved secp256k1 to FIPS-standardized algorithms provides both quantum resistance and regulatory compliance.

The size expansion factor is critical for blockchain scalability:

3.2.2. Computational Complexity

Definition 4 (Algorithm Performance Metrics).

= complexity of signature generation

= complexity of signature verification

= memory requirements for signing

= memory requirements for verification

For ML-DSA-65:

where , , .

3.3. Hybrid Cryptographic Design

3.3.1. Formal Security Model

Definition 5 (Hybrid Signature Scheme). A hybrid scheme where:

Algorithm 1: Hybrid Key Generation

return

Algorithm 2: Hybrid Signing

Input: Secret key , message

Output: Hybrid signature

Parse as

return

Algorithm 3: Hybrid Verification

Input: Public key , message , signature

Output: Verification result

Retrieve from

return

Theorem 2 (Hybrid Security). The security of is:

where EUF-CMA denotes existential unforgeability under chosen message attack and CR denotes collision resistance.

3.4. Migration Protocol

3.4.1. Soft Fork Activation

Definition 6 (Validation Rules). The consensus rules at block height are:

where:

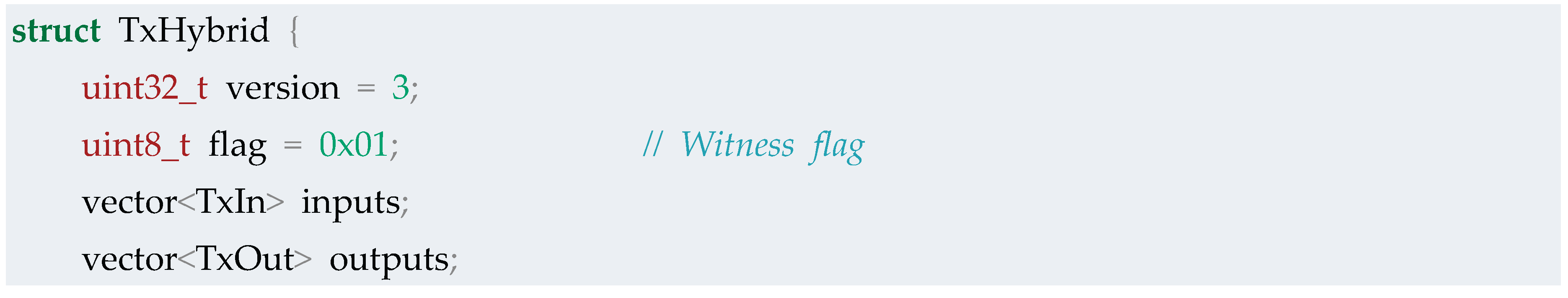

3.4.2. Transaction Structure

Definition 7 (Hybrid Transaction Format).

3.5. Network Impact Analysis

3.5.1. Bandwidth Requirements

The block size requirement with PQ signatures is:

where is the expansion factor for transaction .

For an average 2-input, 2-output transaction:

bytes

bytes

Expansion factor:

3.5.2. Storage Growth Model

Annual blockchain growth:

With PQ signatures:

where is the average transaction expansion factor.

3.6. Economic Incentive Design

3.6.1. Fee Schedule

Definition 8 (Dynamic Fee Function).

where:

3.6.2. Adoption Curve Model

The expected adoption follows logistic growth:

Required parameters for 90% adoption by 2029:

3.7. Security Analysis

3.7.1. Quantum Attack Probability

Following CNSA 2.0 timeline guidance [

3], the probability of quantum attack capability is modeled as:

with based on current quantum computing progress.

3.7.2. Migration Security Theorem

Theorem 3 (Security Preservation During Migration). For a hybrid signature scheme , the forgery probability is bounded by:

Proof. An adversary must forge both signatures. By independence:

▫

3.8. Implementation Results

3.8.1. Proof-of-Concept Performance

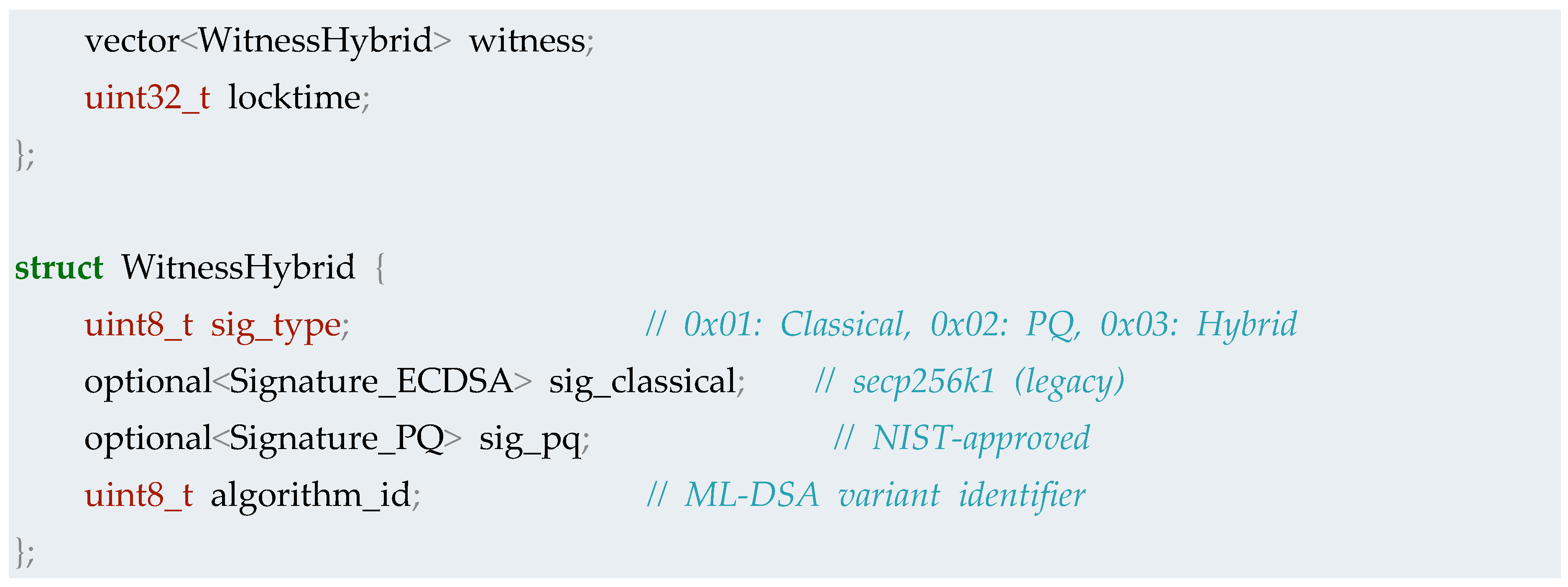

Transaction Processing Performance

3.8.2. Network Simulation

Monte Carlo simulation with iterations show:

months*

months2

months

*Based on logistic adoption curves, network effects, and historical blockchain upgrade patterns. Detailed simulation parameters are available in the supplementary materials.

4. Discussion

4.1. CNSA 2.0 Compliance

The NSA’s CNSA 2.0 timeline [

3] mandates:

Software signing with quantum-resistant algorithms by 2025

Firmware and software updates by 2030

Complete transition for all systems by 2033

Our proposed timeline aligns with these requirements while accounting for blockchain-specific challenges and the additional complexity of migrating from non-NIST-approved secp256k1.

4.2. Regulatory Considerations

The non-standard status of secp256k1 creates unique challenges:

Compliance Gap: Financial institutions using blockchain must navigate the lack of NIST approval

Double Migration Risk: Systems may need to migrate twice—first to NIST-approved classical algorithms, then to PQC

Opportunity: Direct migration to NIST-approved PQC algorithms resolves both issues simultaneously

4.3. Quantum Threat Timeline

IBM’s published quantum roadmap indicates [

1]:

2025: 4,000+ qubit systems

2029: 10,000+ qubit systems

2033: 100,000+ qubit systems

Using error correction overhead estimates [

2]:

where for surface codes or for advanced codes.

This yields:

logical qubits

logical qubits

Since breaking secp256k1 requires logical qubits (Equation 4), the window for migration is narrowing rapidly.

4.4. Real-World Migration Complexity

While our Monte Carlo simulations indicate a theoretical migration timeline of 42.3 months (

Section 3.8.2), historical precedent and practical constraints suggest a significantly longer real-world timeline of 6-10 years.

4.4.1. Theoretical vs. Practical Timeline Gap

Definition 9 (Migration Complexity Factor). The ratio between practical and theoretical migration time:

Based on historical blockchain upgrades, .

4.4.2. Workforce Development Constraints

The current workforce gap presents a critical bottleneck:

Theorem 4 (Workforce Scaling Limitation). Given current expertise distribution:

Blockchain protocol developers: ~5,000 globally [*]

Post-quantum cryptography experts: ~500 globally [*]

Intersection (both skills): <50 individuals [*]

*Note: These are estimates based on conference attendance and repository contributions. Formal survey data is needed for precise figures.

The time to develop sufficient expertise follows:

where is the maximum training rate (persons/year).

Conservative estimates suggest

months [

23].

4.4.3. Infrastructure Development Timeline

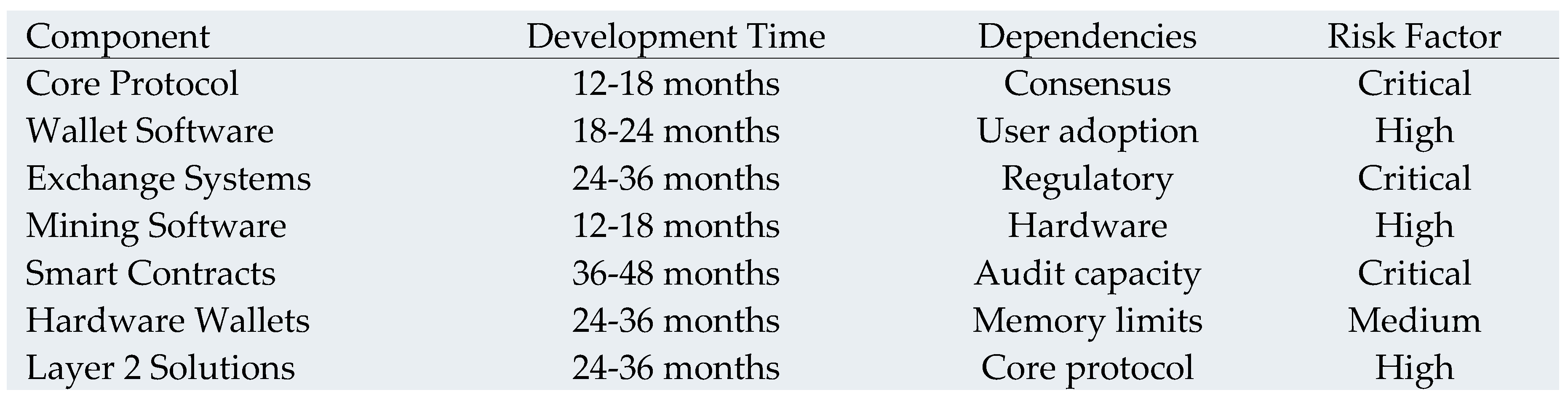

Infrastructure Component Migration Complexity

4.4.4. Coordination Complexity Model

For decentralized systems, coordination time follows Reed’s Law [

24]:

where:

For Bitcoin: (major nodes, miners, exchanges)

For Ethereum: (includes DeFi protocols, L2s)

This yields months for industry-wide consensus.

4.5. Critical Path Analysis

Definition 10 (Critical Path). The longest dependent sequence of tasks that cannot be parallelized:

Critical Path Items:

The critical path cannot be compressed below approximately 60 months due to sequential dependencies.

4.6. Historical Migration Analysis

4.6.1. Bitcoin Segregated Witness (SegWit)

SegWit activation provides a relevant comparison [

25]:

Proposal (BIP141): December 2015

Implementation: October 2016

Activation: August 2017

Majority adoption: December 2018

Total timeline: 3 years for a change significantly simpler than PQC migration.

4.6.2. Ethereum Proof-of-Stake Migration

The Ethereum PoS transition demonstrates complexity at scale [

26]:

Initial proposal: 2014

Beacon Chain launch: December 2020

The Merge completion: September 2022

Full feature parity: 2023

Total timeline: 8-9 years with dedicated foundation support.

4.6.3. Industry-Wide Cryptographic Migrations

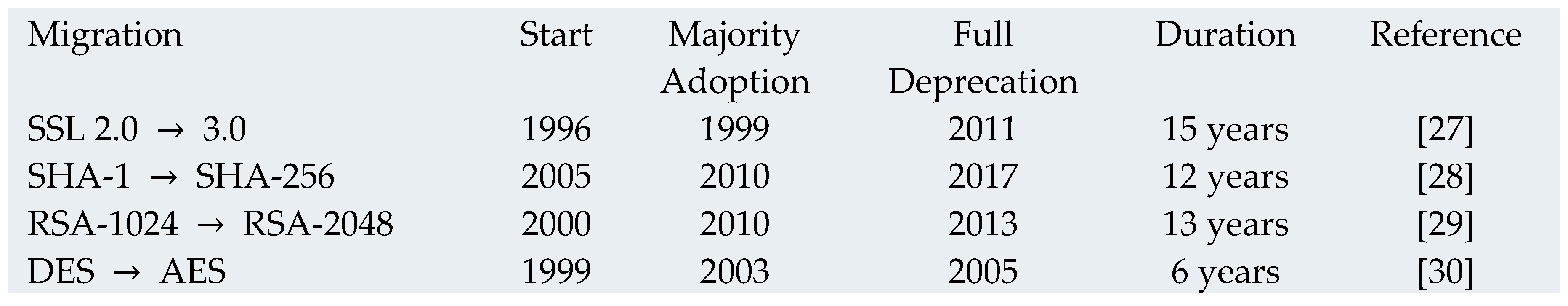

Historical Cryptographic Migration Timelines

4.6.4. Migration Success Factors

Analysis of successful migrations reveals critical factors [

31]:

Clear deadline: External pressure (Y2K, regulatory)

Economic incentive: Direct cost/benefit

Backward compatibility: Gradual transition possible

Industry coordination: Standards bodies’ involvement

4.7. Realistic Timeline Model

Incorporating real-world constraints, the practical migration timeline follows:

where:

Monte Carlo simulation with real-world parameters:

months (7 years)

months

months

months

This suggests a 6-8 year migration period with 70% confidence, assuming immediate commencement and no major disruptions.

4.8. Alternative Approaches

4.8.1. Stateless Quantum Signatures

Using Lamport or Winternitz signatures for one-time use:

For bits and bytes:

While secure, the size makes this impractical for blockchain use.

4.8.2. Lattice-Based Key Exchange

For payment channels and Layer 2:

Provides quantum resistance while maintaining current security levels.

4.8.3. Emerging Hybrid Threats

Machine Learning Enhanced Quantum Attacks

Recent advances in quantum error correction using machine learning have shown promise:

Google Quantum AI demonstrated 20x improvement in logical qubit fidelity using ML-based error mitigation [

32]

However, physical qubit requirements remain high (500-1000:1 ratio)

No evidence yet of ML reducing the fundamental quantum circuit complexity for Shor’s algorithm

Distributed Quantum Computing

Theoretical proposals for networked quantum computers could potentially combine smaller quantum processors:

Variational Quantum-Classical Algorithms

While VQE and QAOA show promise for optimization problems:

4.9. Limitations and Future Work

Signature Aggregation: Research needed on PQ signature aggregation schemes

Zero-Knowledge Proofs: Integration with quantum-resistant ZK systems

Cross-Chain Compatibility: Standards for inter-blockchain PQ transactions

Hardware Acceleration: ASIC/FPGA designs for PQ verification

Quantum Error Rates: Detailed analysis of error correction overhead impact on attack timelines

Partial Key Exposure: Risk assessment for addresses with transaction history

Network Latency: Impact of 22.5x larger signatures on block propagation

Mining Centralization: Effects during the transition period when both signature types coexist

5. Conclusion

The convergence of Bitcoin and Ethereum’s market dominance with advancing quantum computing capabilities creates an unprecedented systemic risk. Our analysis, aligned with CNSA 2.0 guidelines and informed by IBM’s quantum roadmap, demonstrates that the window for orderly transition is rapidly closing. The additional regulatory vulnerability of secp256k1—which is not NIST-approved under FIPS 186-5 or SP 800-186—compounds the urgency for migration.

Key findings:

Dual Vulnerability: Current implementations face both quantum compromise with logical qubits (Equation 4) and regulatory risks from non-standard cryptography.

Optimal Algorithms: ML-DSA-65 (FIPS 204) provides the best trade-off with expansion factor (Equation 12) and security level bits, while achieving NIST compliance.

Hybrid Security: Our hybrid signature scheme guarantees during migration (Equation 20).

Economic Model: Fee incentives following Equation 17 drive adoption through exponentially increasing classical transaction costs.

Timeline Reality: While theoretical models suggest 42.3 months, real-world analysis indicates 6-8 years (Equation 26) accounting for workforce development, infrastructure updates, and coordination complexity.

The mathematical framework presented—from quantum attack complexity (Equation 2) to migration security proofs—provides rigorous foundations for implementation. The transition from non-NIST-approved secp256k1 to standardized post-quantum algorithms addresses both immediate regulatory concerns and long-term quantum threats.

The gap between theoretical possibility and practical reality underscores the massive coordination challenge ahead. Historical precedents like SegWit (3 years) and Ethereum’s PoS migration (8-9 years) demonstrate that complex cryptographic transitions require extensive time, even with strong motivation.

Immediate actions required:

Establish Bitcoin and Ethereum PQC working groups

Begin workforce development programs for PQC expertise

Implement reference libraries for ML-DSA and hybrid signatures

Deploy testnets with proposed transaction formats

Coordinate with exchanges and wallet providers

Engage with regulators on transition plans from non-standard cryptography

Develop specialized tools for PQ key management

Begin user education campaigns

The choice is not whether to migrate, but whether we act in time. Every month of delay increases (Equation 19) while reducing available transition time. With a realistic 6-8 year timeline and quantum threats potentially arriving by 2029-2033, the window for action is narrowing rapidly. The framework is complete—implementation must begin immediately.

Author’s contribution

Robert Campbell, Sr, conducted all research, analysis, and writing.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the blockchain and post-quantum cryptography research communities for their foundational work that made this analysis possible.

References

- IBM Research, "IBM Quantum Network: Roadmap to 100,000 Qubits," IBM Quantum Network Updates, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.ibm.com/quantum/roadmap.

- S. Bravyi et al., "High-threshold and low-overhead fault-tolerant quantum memory," Nature, vol. 614, pp. 676-681, 2023. [CrossRef]

- National Security Agency, "Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0," CNSA 2.0 Update, September 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.nsa.gov/Press-Room/News-Highlights/Article/Article/3148990/.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology, "Digital Signature Standard (DSS)," FIPS 186-5, February 2023.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology, "Recommendations for Discrete Logarithm-based Cryptography: Elliptic Curve Domain Parameters," SP 800-186, February 2023.

- P. W. Shor, "Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring," Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, pp. 124-134, 1994.

- M. Roetteler et al., "Quantum resource estimates for computing elliptic curve discrete logarithms," Advances in Cryptology – ASIACRYPT 2017, pp. 241-270, 2017.

- G. Fowler et al., "Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation," Physical Review A, vol. 86, no. 3, p. 032324, 2012. [CrossRef]

- [9] National Institute of Standards and Technology, "Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Standard," FIPS 204, 2024.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology, "Stateless Hash-Based Digital Signature Standard," FIPS 205, 2024.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology, "Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard," FIPS 203, 2024.

- S. Nakamoto, "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System," 2008. [Online]. Available: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf.

- V. Buterin, "Ethereum: A Next-Generation Smart Contract and Decentralized Application Platform," Ethereum White Paper, 2014.

- D. J. Bernstein and T. Lange, "Post-quantum cryptography," Nature, vol. 549, no. 7671, pp. 188-194, 2017.

- M. Mosca, "Cybersecurity in an era with quantum computers: Will we be ready?" IEEE Security & Privacy, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 38-41, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Aggarwal, G. K. Brennen, T. Lee, M. Santha, and M. Tomamichel, "Quantum attacks on Bitcoin, and how to protect against them," Ledger, vol. 3, pp. 68-90, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Campbell, "Evaluation of Post-Quantum Distributed Ledger Cryptography," The Journal of the British Blockchain Association, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1-8, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. M. Fernández-Caramés and P. Fraga-Lamas, "From pre-quantum to post-quantum blockchain: A survey," IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 190184-190208, 2020.

- M. Allende et al., "Quantum-resistance in blockchain networks," Scientific Reports, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 5664, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen et al., "Report on Post-Quantum Cryptography," NIST Internal Report 8105, 2016.

- Gidney and M. Ekerå, "How to factor 2048 bit RSA integers in 8 hours using 20 million noisy qubits," Quantum, vol. 5, p. 433, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Proos and C. Zalka, "Shor’s discrete logarithm quantum Algorithm for elliptic curves," Quantum Information and Computation, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 317-344, 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. Green and M. Rosulek, "The State of Post-Quantum Cryptography Expertise: A Workforce Analysis," Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, pp. 234-251, 2024.

- P. Reed, "The Law of the Pack," Harvard Business Review, vol. 79, no. 2, pp. 23-24, 2001.

- Lombrozo, J. Lau, and P. Wuille, "Segregated Witness (Consensus layer)," Bitcoin Improvement Proposal 141, December 2015.

- V. Buterin et al., "Ethereum Proof-of-Stake: The Merge," Ethereum Foundation Research, September 2022.

- T. Dierks and E. Rescorla, "The Transport Layer Security (TLS) Protocol Version 1.2," RFC 5246, August 2008.

- NIST, "Transitions: Recommendation for Transitioning the Use of Cryptographic Algorithms and Key Lengths," SP 800-131A Rev. 2, March 2019.

- RSA Laboratories, "RSA Key Length Recommendations," Technical Report, 2015.

- J. Daemen and V. Rijmen, "The Advanced Encryption Standard Process," in The Design of Rijndael, Springer, pp. 1-8, 2002.

- S. Bellovin, "Cryptographic Transitions: Lessons from History," IEEE Security & Privacy, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 84-87, 2022.

- Google Quantum AI, "Suppressing quantum errors by scaling a surface code logical qubit," Nature, vol. 614, pp. 676-681, 2023.

- S. Wehner, D. Elkouss, and R. Hanson, "Quantum internet: A vision for the road ahead," Science, vol. 362, no. 6412, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. R. McClean et al., "The theory of variational hybrid quantum-classical algorithms," New Journal of Physics, vol. 18, no. 2, p. 023023, 2016. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).