1. Introduction

Statistical confidentiality refers to safeguarding data to ensure it remains useful for statistical analysis while minimizing the risk of identifying individuals [

1,

2]. It ensures that information collected for research or statistical purposes is used solely for those intended purposes and not in ways that could compromise personal privacy. While techniques such as encryption, access control, anonymization, and differential privacy provide some level of statistical privacy, they often have limitations [

3].

Statistical confidentiality is a central concern in the operations of the US Census Bureau[

4]. This is true for its counterparts all over the world as well as other institutions that deal with data collected from users [[

1,

5,

6]. The US Census Bureau, in 2020, emphasized the limitations of the traditional methods to protect the privacy of users and introduced differential privacy to quantify the level of privacy that is provided with various methods [

7] . For the 2030 census, the Census Bureau has published a research agenda to identify improvements to the current disclosure avoidance methods. According to the planning and development timeline published on their website, after a two-year research, feedback, and development phase, the final system will be selected in 2027-2028 to get ready for production in the next census year of 2030[

8].

Homomorphic encryption (HE), which relies on deep mathematical theories allows operations on encrypted data. Unlike traditional mechanisms for confidentiality where the focus is on hiding the association between the data points and users, HE hides the plaintext data itself. As such it is a powerful tool to protect not just the associations or relations between data points, but the data itself. Combined with other protection mechanisms such as strong access control, HE can provide ultimate security of data not only at rest and in transit but also in use. With statistical confidentiality becoming increasingly critical with the data-centric world we live in, this is a great time to explore the viability of homomorphic encryption for statistical confidentiality for various use cases.

Two major challenges of homomorphic encryption are the computational intensity of operations resulting in high time complexity and the difficulty of adapting traditional algorithms designed for plaintext data, to operate on encrypted data. Sorting is one such example. In this study, we use ZAMA’s Concrete compiler [

9], which implements Fully Homomorphic Encryption over the Torus (TFHE) [

10] to implement and evaluate the performance of three sorting algorithms on homomorphically encrypted data. In addition, we provide implementations of traditional algorithms for basic statistical computations on encrypted datasets, including the five-number summary, mean, variance, and mode, and record the time required for each operation. While our findings support the theoretical feasibility of fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) for statistical analysis, significant optimization is needed to make its practical use in real-world applications more efficient.

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides background information on homomorphic encryption and ZAMA’s Concrete complier.

Section 3 summarizes the literature on the use of homomorphic encryption for statistical calculations.

Section 4 explains our methodology, and

Section 5 provides implementation details.

Section 6 reports the results, and section 7 concludes the paper with a discussion of the results.

2. Background

Homomorphic encryption (HE) allows computations on encrypted data without revealing it to anyone other than an owner or an authorized collector. When combined with other techniques, homomorphic encryption offers an ideal solution for ensuring statistical confidentiality.

HE schemes are categorized into three families based on the main operations they involve and how they achieve homomorphic encryption: Partially Homomorphic Encryption (PHE), Somewhat Homomorphic Encryption (SWHE) and Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE). PHE schemes allow only one type of operation with no limits on the number of times the operation can be performed. PHE schemes support evaluation of either addition or multiplication, but not both. SWHE schemes allow both addition and multiplication with a limit on the number of operations that can be carried out. FHE schemes allow computations with no bounds on the type of operations and number of times they are performed.

The first FHE scheme was proposed by Craig Gentry in 2009[

11]. The study included not just an FHE scheme but a broad framework for designing new schemes. Several researchers have tried to build a safe and useful FHE scheme based on Gentry’s work.

A major leap forward came with the work of Chillotti, Gama, Georgieva, and Izabachène in 2016 who introduced a method for bootstrapping in under 0.1 seconds [

12]. Their approach reimagined FHE in the context of Boolean logic, focusing on evaluating one logic gate at a time rather than full arithmetic circuits. By leveraging a representation of ciphertexts over the torus (real numbers mod 1), they achieved a dramatic speedup, making homomorphic operations viable for real-time applications.

Building on this, the same team formalized and refined their method in the “TFHE: Fast Fully Homomorphic Encryption over the Torus” paper [

10]. This work presented a complete, well-optimized system for fast homomorphic encryption over the torus, including security proofs and performance benchmarks. Following this, an open-source library was released that made TFHE one of the most practical FHE schemes available, particularly for applications involving encrypted decision-making and control flow. For an excellent overview of TFHE we refer the reader to the 2023 thesis by Paolo Tassoni [

13].

ZAMA is a French cryptography company that specializes in building open-source homomorphic encryption solutions with a focus on development of applications in the field of Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain [

14]. It aims to simplify the use of homomorphic encryption for developers and helps with the “complexity of FHE operations, managing noise, choosing appropriate crypto parameters, and finding the best set and order of operations for a specific computation” [

13].

The core product of ZAMA is a compiler called Concrete written in C++ and developed with Multi-Level Intermediate Representation (MLIR), an open-source project for building reusable and extensible compiler infrastructure[

15]. In April 2023 ZAMA released a version of Concrete that converts Python programs into their FHE equivalents. The conversion process includes representing each function as a “circuit”, a direct acyclic graph of operations on variables, where each variable can be encrypted or in plaintext. The circuit is compiled with parameters producing a dynamic library with FHE operations and a JSON file with the cryptographic configuration called Client Specs. The circuit can perform the homomorphic evaluation of the desired function, and these operations can be used in the context of a Client-Server interactions.

3. Related Work

Homomorphic encryption has emerged as a transformative technique in privacy-preserving computation, allowing mathematical operations on encrypted data without decryption. This capability is particularly valuable in fields requiring secure data processing, such as statistical analysis of sensitive information, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence. Fully homomorphic encryption algorithms have been around more than a decade and have recently evolved from a theoretical concept to a practical tool. In addition to Zama, major tech companies including Microsoft and IBM have contributed to the field. Microsoft’s SEAL (Simple Encrypted Arithmetic Library) supports both BFV and CKKS encryption schemes to enable secure arithmetic and approximate computations on encrypted data [

16]. Likewise, IBM has been a major contributor in the development of HElib, a library that implements the BGV scheme [

17].

In this study we focus on preserving privacy in statistical computations. Two main tasks that are needed for statistical computations are comparison and sorting. In this section we present recent studies that have proposed innovative approaches to enhance the efficiency and practicality of sorting and comparison.

The study “Homomorphic Comparison Method Based on Dynamically Polynomial Composite Approximating Sign Function” introduces a polynomial approximation method for the sign function, enabling effective comparison of encrypted values[

18] The dynamically composed polynomials adapt to the encrypted domain’s constraints, improving accuracy and maintaining acceptable computational costs.

In “Efficient Sorting of Homomorphic Encrypted Data With k-Way Sorting Network” authors propose a scalable and parallelizable sorting mechanism using k-way sorting networks [

19]. Unlike traditional binary sort networks, k-way networks reduce the number of comparisons and depth of computation, making them well-suited for homomorphic environments. The method is compatible with leveled homomorphic encryption schemes, optimizing for both depth and ciphertext noise. Experimental results show significant performance gains compared to earlier sorting methods in HE, particularly in terms of latency and computational overhead.

The paper “Innovative Homomorphic Sorting of Environmental Data in Area Monitoring Wireless Sensor Networks” explores a practical application of HE in wireless sensor networks (WSNs) for environmental data monitoring [

20]. The authors employ an additive homomorphic encryption scheme to enable secure sorting of sensor data without compromising data confidentiality. Their approach integrates a modified bubble sort algorithm that operates directly on ciphertexts, optimized for low-power devices in WSNs. The results demonstrate a feasible balance between computational efficiency and data security, showcasing the potential of HE in real-time environmental analytics.

In “An Efficient Fully Homomorphic Encryption Sorting Algorithm Using Addition Over TFHE”, the authors leverage the TFHE scheme’s capabilities, particularly its fast gate bootstrapping and efficient binary circuit evaluation [

21]. They design a sorting algorithm that primarily uses addition operations to minimize expensive multiplications. The approach is tailored for the TFHE framework, which supports bit-level operations efficiently.

The 2024 paper “Practical solutions in fully homomorphic encryption: a survey analyzing existing acceleration methods” systematically compares and analyzes the strengths and weaknesses of FHE acceleration schemes [

22]. The authors classify existing acceleration schemes from algorithmic and hardware perspectives and propose evaluation metrics to conduct a detailed comparison of various methods.

The growing reliance on cloud computing, data analytics, and artificial intelligence has heightened the need for privacy-preserving computations.

Our study explores the practicality of homomorphic encryption for statistical computations. In particular, we examine the efficiency of the TFHE algorithm as implemented in Zama’s Concrete framework following the optimizations in “Parameter Optimization and Larger Precision for (T)FHE” [

23] on a standard computer and provide implementations of traditional algorithms for basic statistical computations on encrypted datasets, including the five-number summary, mean, variance, and mode.

4. Materials and Methods

To explore the viability of homomorphic encryption and computations for statistical calculations, we implement a client-server application that allows the client to send encrypted data to the server for statistical computations. We consider the client the owner of the data, and the server the computational engine and report the time it takes to carry out the homomorphic calculations on the server side.

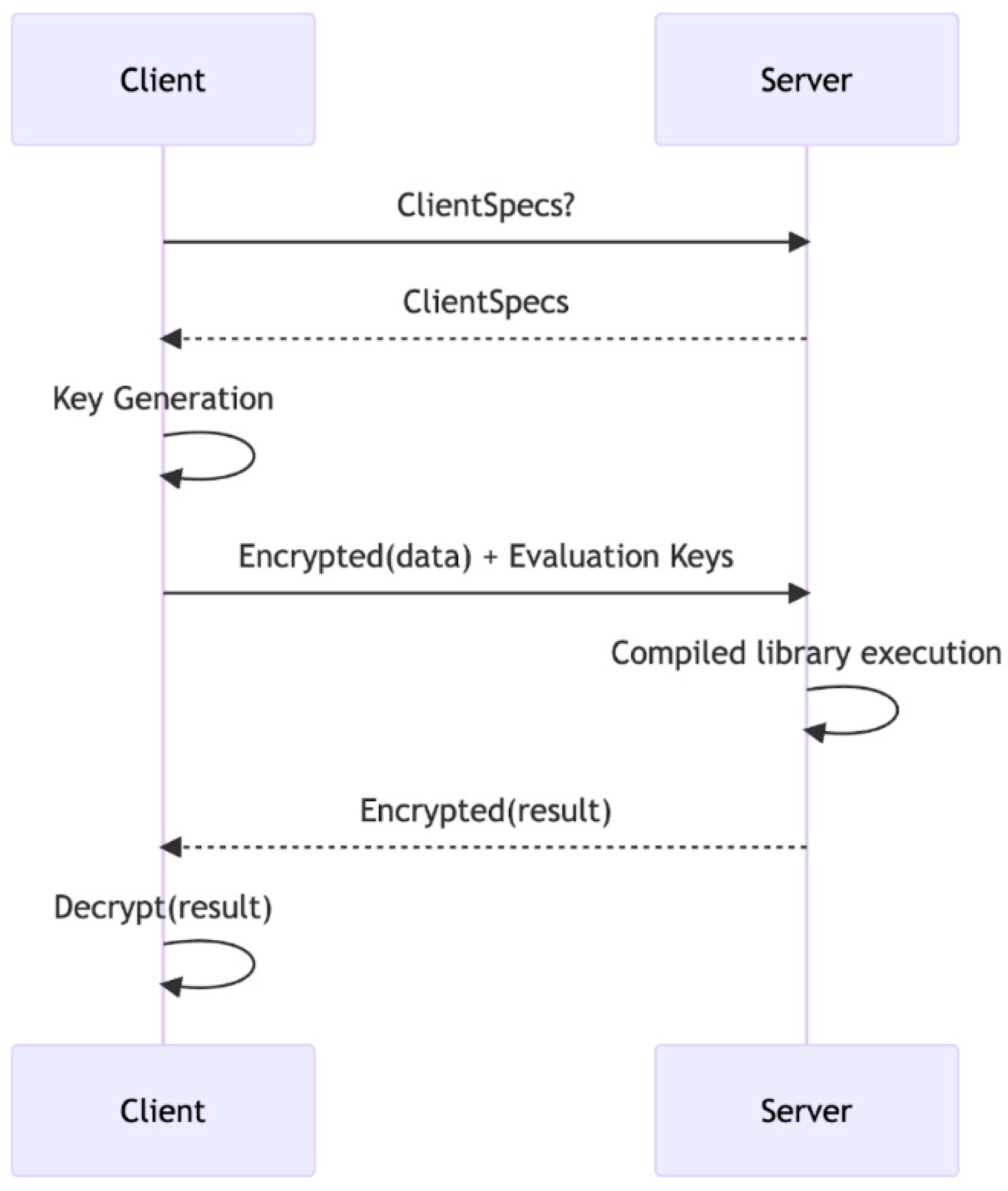

We follow the client-server model provided by ZAMA as depicted in

Figure 1 and use ZAMA’s Concrete compiler to implement calculation of the 5-point summary statistics, mean, variance, and mode. In the application, the data is randomly generated for the desired range and size.

The main points to note of the application are:

The client possesses the key to encrypt and decrypt the data.

The client encrypts the dataset and sends the encrypted dataset to the server.

The server gets the encrypted dataset, calculates the requested statistics, and sends the encrypted result(s) to the client.

The client then decrypts the encrypted results to get the desired results.

The application allows the calculation of basic statistics: mean, variance, mode, 5-point summary statistics which include the min, max, median, lower quartile, and upper quartile. Among these, the calculation of 5-point summary is straightforward if the data is sorted. For this reason, we placed special emphasis on sorting encrypted data. We implemented three sorting algorithms, namely bubble sort, odd-even sort, and bitonic sort and compared their timing.

To sum up, we collect timing data on these computations:

4.1. Security of the Application

The data is protected in transit and in use by the application since it is encrypted on the client side before it is transmitted and not decrypted until the encrypted result reaches the client. As such the data is also protected at rest on the server side.

The data is randomly generated on the client side and is not stored in the application. If needed, an additional layer of encryption can be implemented on the client side to provide the security of the data at rest on the client side.

In the system, the only party who can view and manipulate the data in plaintext is the data owner, i.e., the client. The server does not have access to the key that can decrypt the data. All computations are done on encrypted values ensuring user privacy and robust protection against data breaches even if the server is compromised.

In the application, the only information that the server (and hence others) has access to in plaintext is the number of data points. This quantity needs to be shared with the server for the homomorphic computations to be carried out.

5. Implementation

The proposed system is implemented using Zama’s Concrete framework, an open-source framework that simplifies the use of Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) [

9]. The main component of the framework is the Concrete compiler which turns Python code into its FHE equivalent in a process called “FHE compilation”. It incorporates the TFHE algorithm for homomorphic computations.

5.1. Limitations

While implementing the system, we came across the following limitations within FHE and Concrete:

Branching: Concrete does not support branching, which means we cannot use conditional statements such as if-else. This limitation makes it difficult to implement complex algorithms, especially sorting algorithms since they rely on comparisons.

Data Types: Concrete only supports encrypted Integers along with Boolean data types which means we cannot work with decimal or floating-point numbers. Furthermore, the division of encrypted numbers is not supported. This limitation further restricts the number of analyses that can be performed.

5.2. Calculation of Mean

Mean is calculated by dividing the sum of data points with the total number as shown in Equation (1).

However, as mentioned in section 5.1, we are unable to perform division on encrypted data. Therefore, only the sum of the encrypted data points is calculated, which is then divided by the total number of data points after decryption to get the result.

5.3. Calculation of Variance

Variance of a set of values is calculated using Equation (2)

This equation is not compatible with FHE calculations since it includes calculation of mean and therefore involves division. To overcome this limitation, we use Equation (3) which is derived in [

24].

With this approach we are able to eliminate mean calculation; however, it was not possible to remove division altogether. Therefore, we are only calculating the numerator on the encrypted data. Once the result is returned, it is decrypted and divided by the denominator.

5.4. Sorting

Except for mean and variance, all statistical operations mentioned in

Section 4 can be calculated easily from a sorted dataset. Sorting is not a function provided in the Concrete library. So, we explored ways to implement sorting on encrypted data.

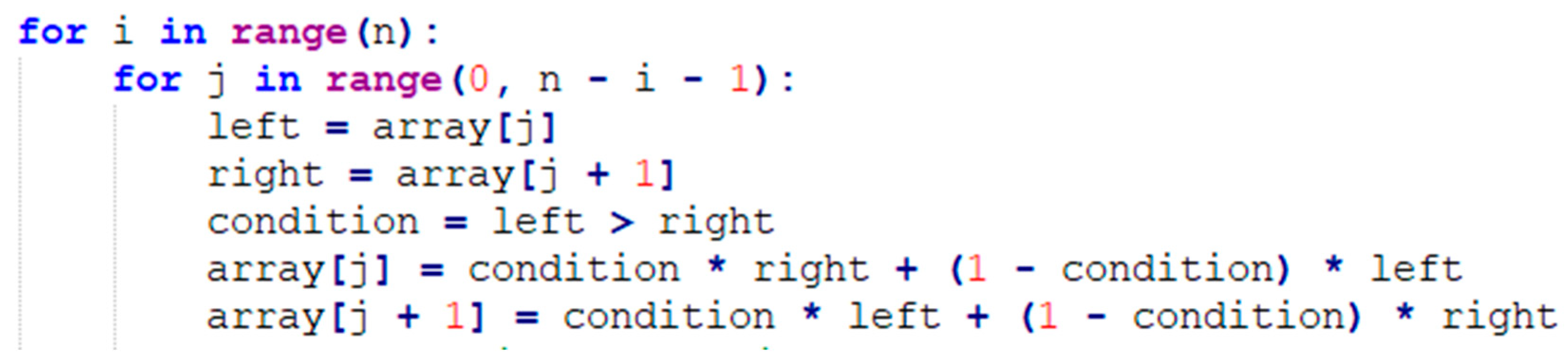

We have implemented three different algorithms for sorting encrypted data: bubble sort, odd-even sort, and bitonic sort. Considering the limitations associated with Concrete, implementing any sorting algorithm becomes a challenge. Essentially sorting works by comparisons and since we were unable to use branching (if-else statements) we had to come up with alternate strategies. To overcome this issue, we used equality:

In expression (4), the left-hand side is a ternary operator where is the condition, is the result if is true, and is the result if is false. This logic can be easily implemented in traditional programming. However, since we are unable to implement branching on encrypted data, we took inspiration from the mathematical alternate shown on the right-hand side of Equation (4). The condition when evaluated would return a boolean value which would either be 0 or 1 in encrypted form. The logic is demonstrated in the following equations:

If then Equation (4) becomes

If then Equation (4) becomes

Bubble sort works by repeatedly comparing two adjacent values in an array and swapping the numbers if they are in the wrong order. This is achieved by implementing nested loops. Where the outer loop runs for each element of the array and the inner loop performs comparisons of the adjacent values. With each pass of the inner loop, the largest unsorted value is shifted towards the end, therefore the number of iterations in each pass of the inner loop decreases by one. The implementation of bubble sort is shown in

Figure 2.

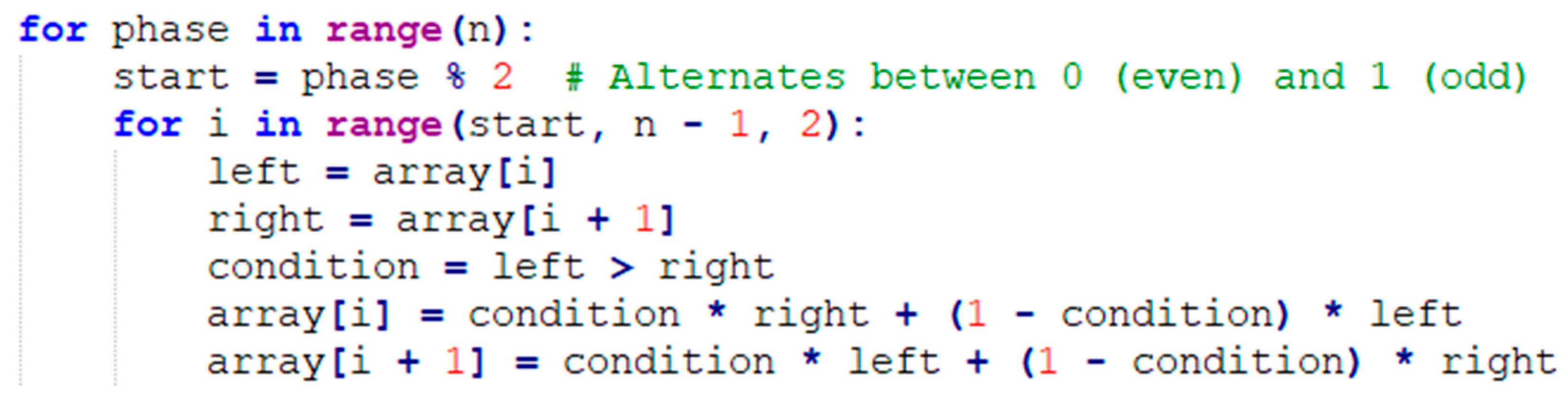

Like bubble sort,

odd-even sort algorithm works by repeatedly comparing two adjacent values in an array and swapping the numbers if they are in the wrong order. However, unlike bubble sort, this algorithm works in two alternating phases: odd and even. Even phase starts at index 0 and compares the element at index 0 with the element at index 1 and moves to index 2 by comparing the element at index 2 with the element at index 3 and so on. Similarly, odd phase starts with index 1 and compares the element at index 1 with the element at index 2 and so on. These phases continue until the array is completely sorted.

Figure 3 depicts the implementation of odd-even sort algorithm.

Bitonic Sort is a recursive, divide and conquer sorting algorithm that works by splitting the array into smaller sub arrays and arranging them in a bitonic sequence where the first half is sorted in ascending order and second half is sorted in descending order. These sequences are then merged recursively using compare and swap operations until the entire array is sorted in ascending order. One limitation of bitonic sort is that it only works correctly when the length of array is a power of 2 since the algorithm works by splitting the array in two of each recursive step. A part of the implementation of bitonic sort is shown in

Figure 4.

5.5. Five-Point Summary

The five-point summary includes min, max, median, upper quantile, and lower quantile of the data. For a sorted dataset, the task of implementing the 5-point summary is trivial. Once the array is sorted, min and max values are retrieved from the first and last index, respectively. To calculate the median, we return the middle element of the array if the length of the array is an odd number. If the length is an even number, we return the sum of the middle two elements. After decryption, the sum is divided by 2 which results in the median value. Since upper and lower quantiles are essentially the medians of first and second half of a given data set, we split the sorted array into two and calculate the median of these two halves. We are calculating the five-point summary of data using bitonic sort if the number of data points is a power of two and using bubble sort otherwise.

5.6. Mode and Frequencies

Mode is defined as the most frequent value in a data set. In traditional programming, it can be easily implemented by using data structures that hold key value pairs (example: a HashMap). However, that approach was not feasible while working with encrypted data. Therefore, we create a separate array which stores the frequency of each element. This is achieved by comparing each element with all the elements using nested loops. After constructing the frequency array, we return the element with the highest frequency.

6. Results

The application is run within a Docker environment with limited resources (8 CPUs, 8 GB memory) on a system with an 11th Gen Intel Core i5 processor and 16 GB RAM.

For each size and range, we ran the application five times and recorded the average of the five5 runs.

6.1. Timing of Mean Calculations

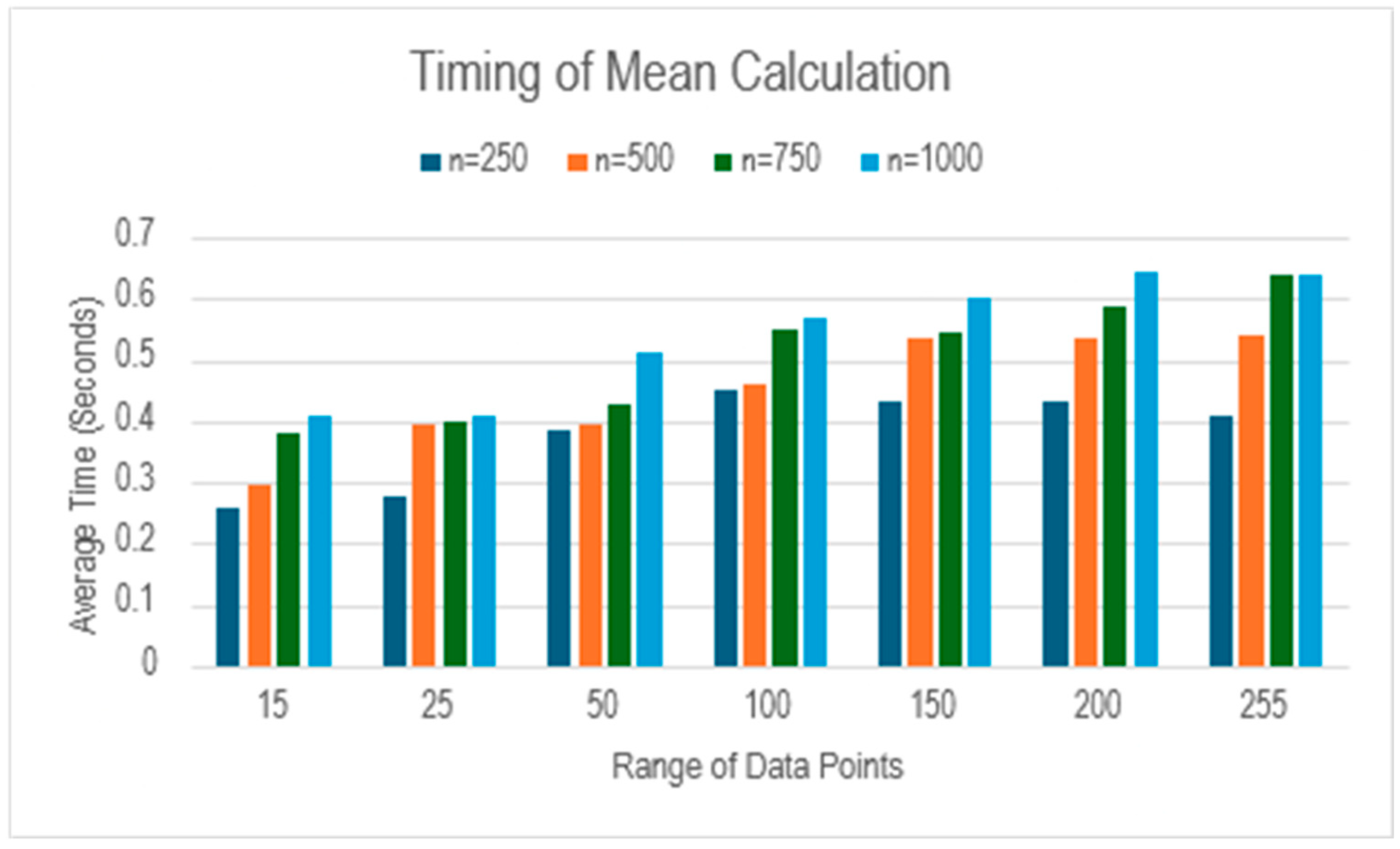

We recorded the time (seconds) it takes to calculate the sum of encrypted data points of 250, 500, 750 and 1000 over the range of 15, 25, 100, 150, 200 and 255.

As

Table 1 indicates, the process of calculating the mean takes under 1 second even for a data set containing 1000 data points. However, we were unable to calculate mean for more than 2000 data points. Even though there is no significant difference between the timings, the general trend observed in this data set is that time increases with the number of data points as well as the range of numbers which can be seen in

Figure 5.

6.2. Timing of Variance Calculations

For variance, we recorded the time in seconds for 5, 10 and 15 data points with the range of 5, 10, 15 and 25 as shown in

Table 2. We were only able to collect limited data since calculation of variance is expensive in terms of resources as it involves a lot of computations on encrypted data.

As

Table 2 indicates, there is a significant increase in time as the number of data points increases. The time also increases as the range of numbers increases.

Figure 6 provides a visual representation of

Table 2.

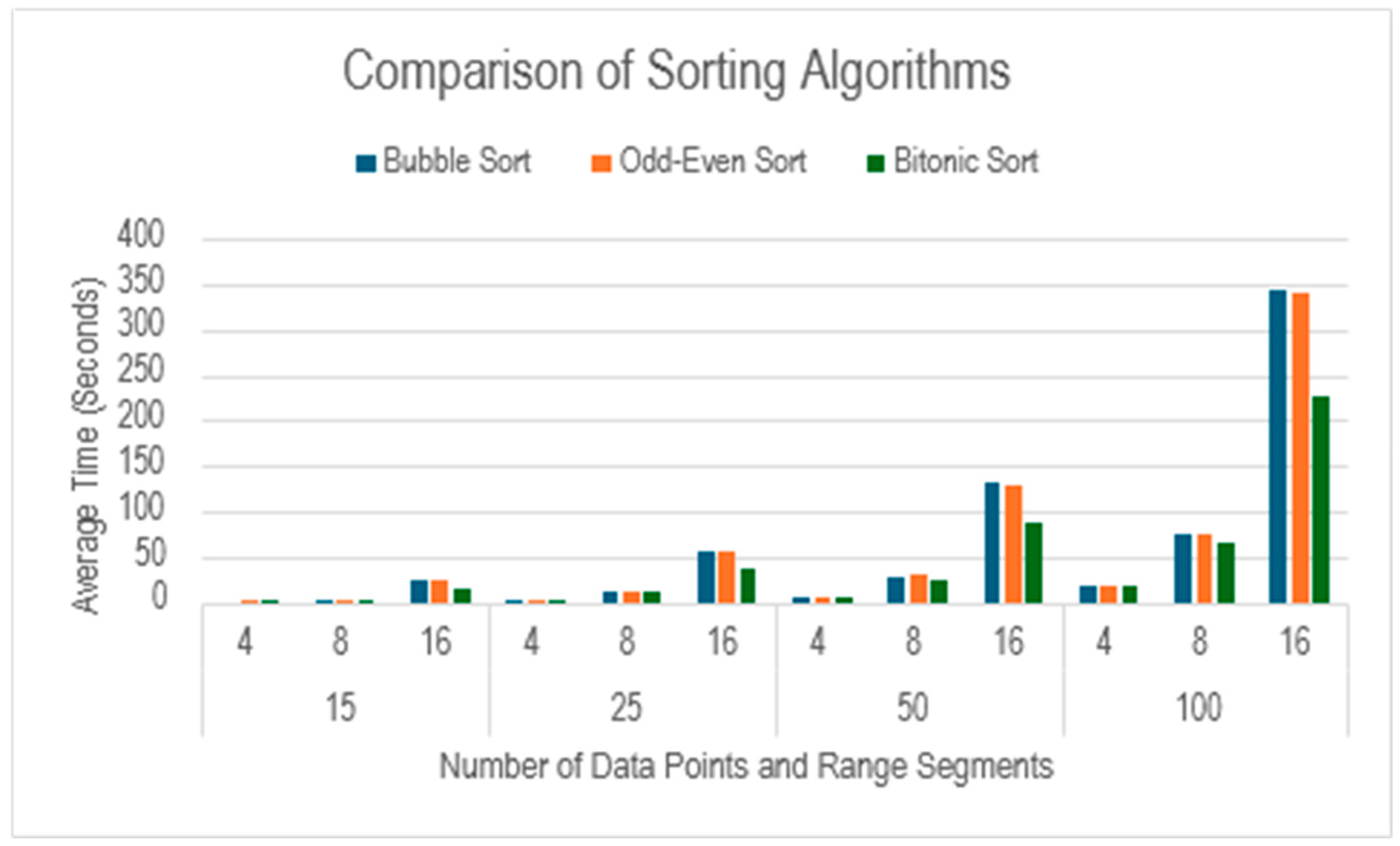

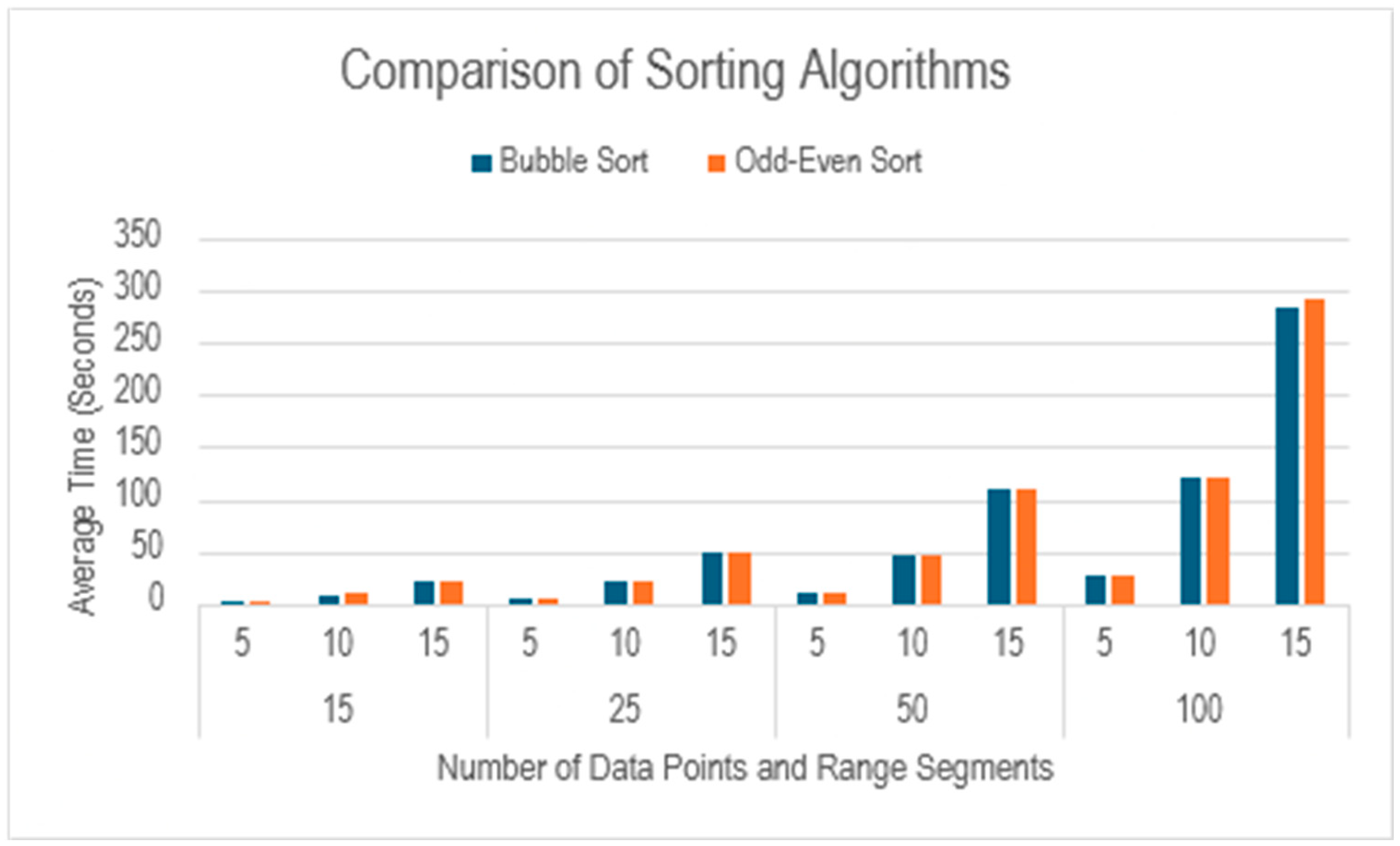

6.3. Timing of Sorting Algorithms

We have recorded the timing of the three sorting algorithms; namely bubble sort, odd-even sort, and bitonic sort, described in

Section 5.4.

Table 3 compares the timings of the three sorting algorithms when the number of data points is a power of two.

Table 4 shows the comparison between bubble sort and odd-even sort for other cases.

The performance of bitonic sort is significantly better than bubble sort and odd-even sort, especially as the data sets get larger and the range of numbers increases, which can be clearly observed in

Figure 7. In comparison there is no significant difference between the timing of bubble sort and odd-even sort as can be seen in

Figure 8.

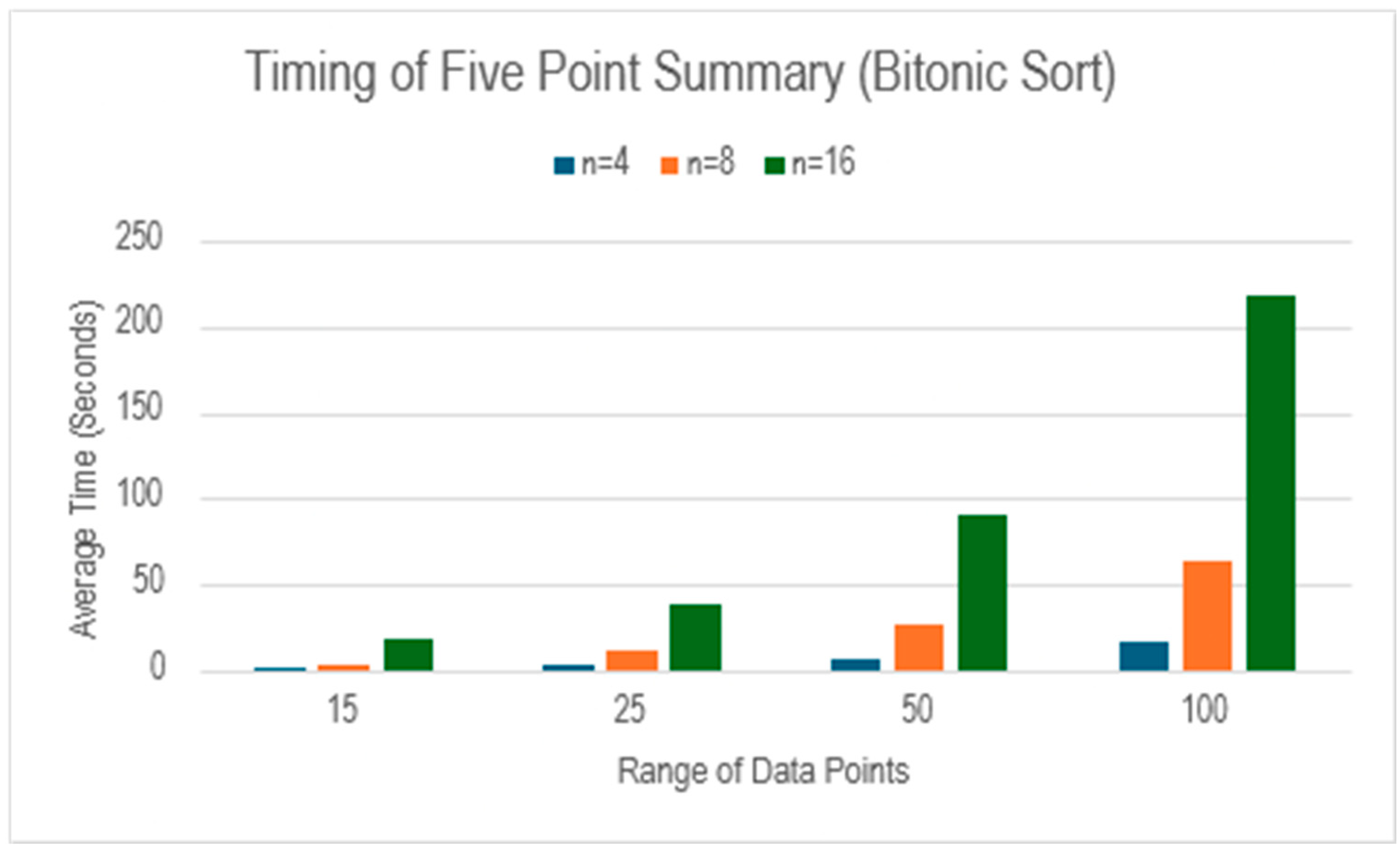

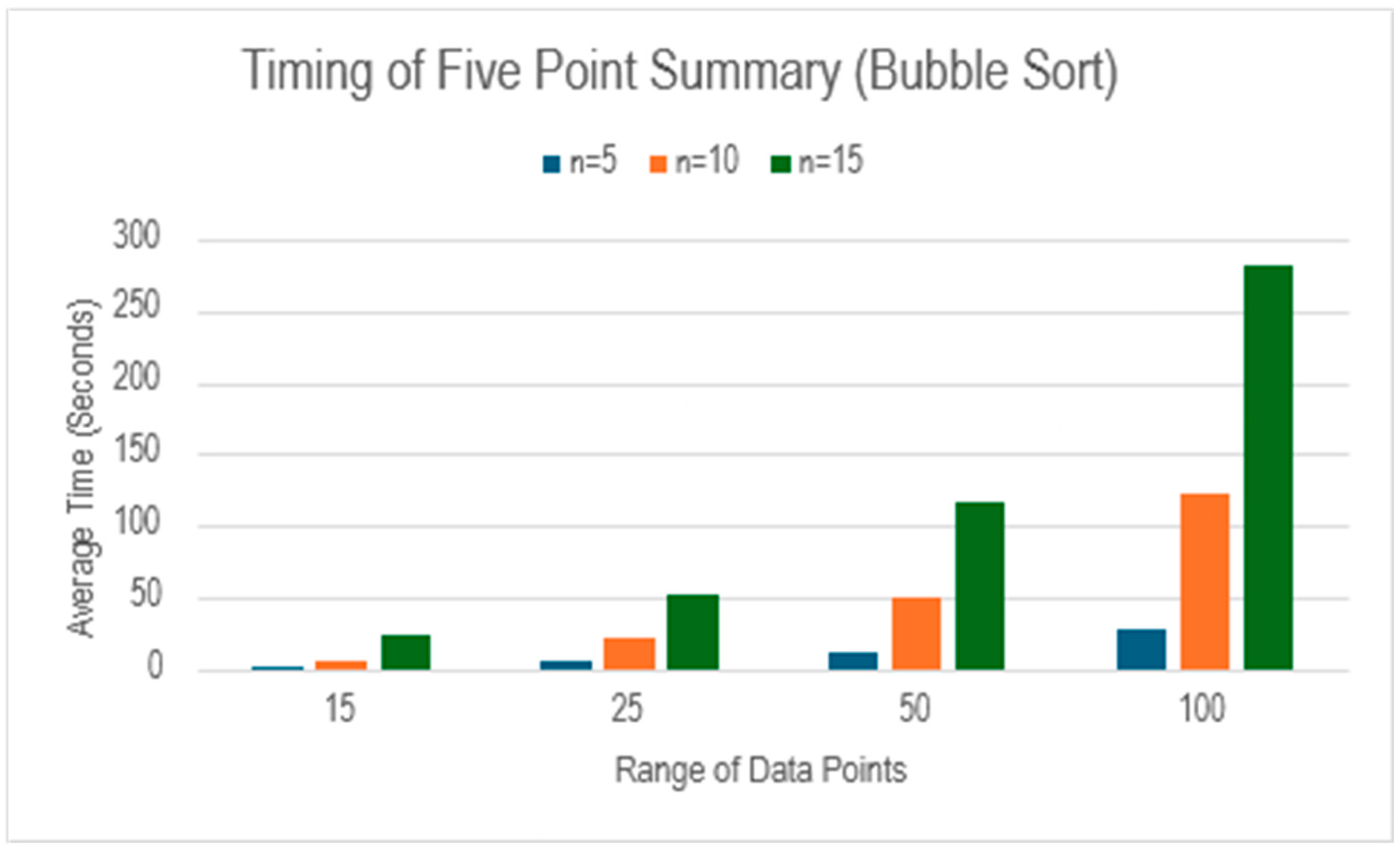

6.4. Timing of Five-Point Summary Calculations

Five-point summary is being calculated on sorted data. Since the performance of bitonic sort algorithm is better than bubble sort and odd-even sort, we are using bitonic sort for sorting the data set if the number of data points is power of two and bubble sort otherwise. The data that we collected includes the time it takes to sort the encrypted data and the calculation of five-point summary which includes; min, max, median, upper quantile and lower quantile.

Table 5 shows the time of calculating five-point summary using bitonic sort algorithm whereas

Table 6 shows the calculation using bubble sort algorithm.

The results from

Table 5 clearly indicate the trend of time increasing with the number of data points as well as the range of numbers which is also illustrated in

Figure 9.

Table 6 follows a similar trend of an increase in time with the number of data points and their range which can also be seen in

Figure 10. However, as observed in the comparison of sorting algorithms, the calculation of five-point summary is faster with bitonic sort algorithm especially when the number of data points and their range increases.

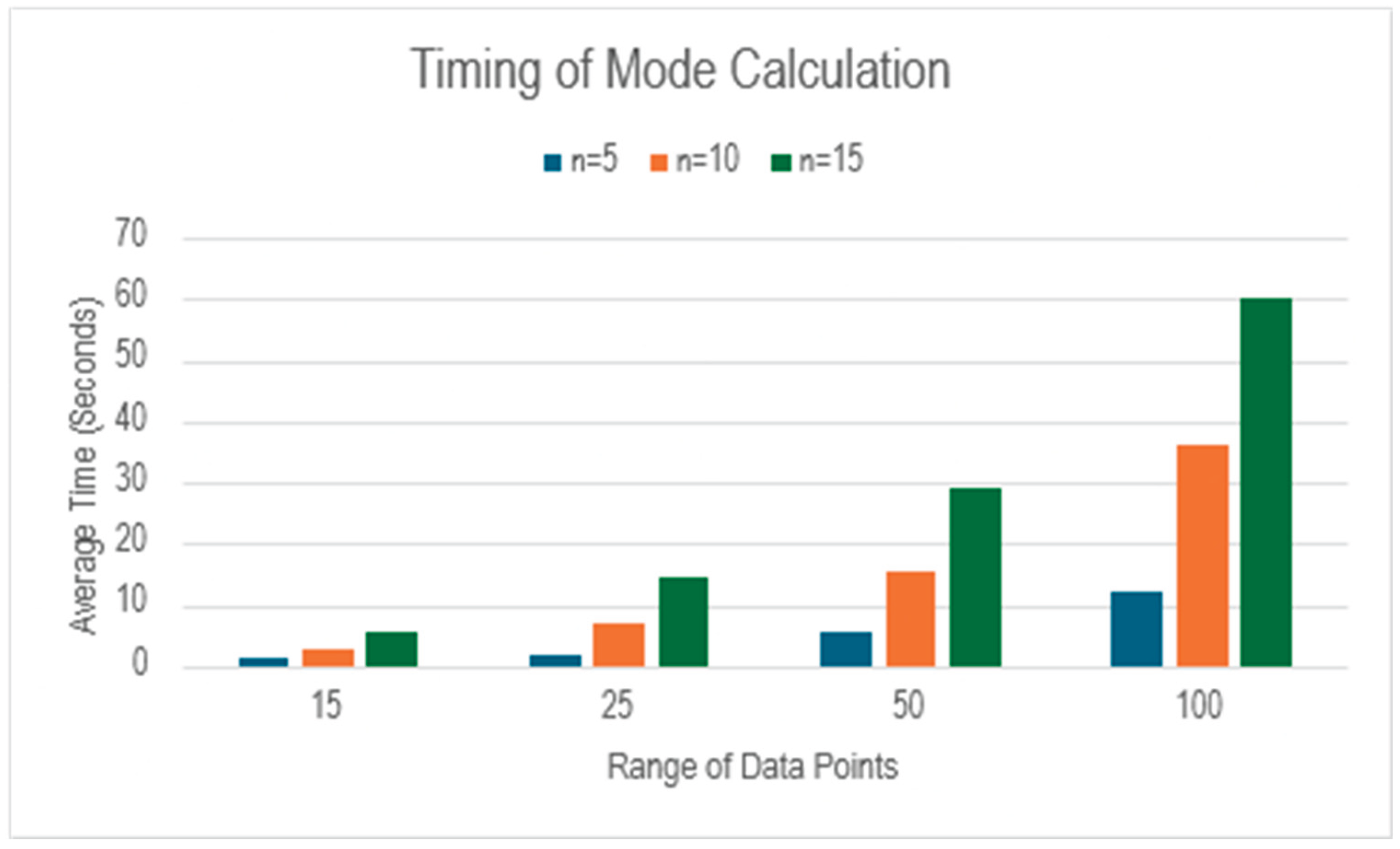

6.5. Timing of Mode Calculations

For mode calculation we have collected data for 5, 10, and 15 data points with the range of 15, 25, 50 and 100.

Table 7 shows the average time to calculate mode for each range and number of data points.

Similar to the trend observed so far,

Table 7 also highlights the increase of time with the increase in range and number of data points. This is further demonstrated in

Figure 11.

7. Discussion

This study proposed a system that provides security and confidentiality of data by utilizing fully homomorphic encryption. Data is encrypted by the client and sent to the server where the statistical operations are performed, and the result is returned in encrypted form. The encrypted result is then decrypted on the client side to get the results. This ensures that the data remains secure in transit as well as in use.

The results show that for encrypted numbers, simple operations such as addition can be performed quickly for small to large datasets. However, multiplication takes comparatively longer. The time increases with the complexity of the algorithms, which includes nature as well as the number of operations that must be performed, including the number of data points and their range. Limitations such as the inability to divide encrypted numbers and using only integers are major hurdles that restrict the number of algorithms that can be implemented.

Nevertheless, this work reinforces the theoretical promise of Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) for statistical analysis and highlights a clear path forward: the development of optimized, FHE-compatible algorithms. With continued advancements, the practical application of FHE in real-world analytics is well within reach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K.P; methodology, Y.K.P and R.R.; software, R.R.; validation, Y.K.P. and R.R.; formal analysis, Y.K.P.; resources, Y.K.P and R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K.P and R.R.; writing—review and editing, Y.K.P and R.R.; visualization, R.R.; supervision, Y.K.P.; project administration, Y.K.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Statistical Confidentiality and Personal Data Protection - Microdata - Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/statistical-confidentiality-and-personal-data-protection# (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- 11 Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act (2002) | CIO. Available online: https://www.cio.gov/handbook/it-laws/cipsea/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Bureau, U.C. Statistical Safeguards.

- Data Protection and Privacy Policy. Available online: https://www.census.gov/about/policies/privacy.html (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Statistical Confidentiality | Insee. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/en/information/2388575 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Statistical Standards Program - Confidentiality Procedures. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/statprog/confproc.asp (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Differential Privacy for Census Data Explained. Available online: https://www.ncsl.org/technology-and-communication/differential-privacy-for-census-data-explained (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Decennial Census Disclosure Avoidance. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/disclosure-avoidance.html (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Welcome | Concrete. Available online: https://docs.zama.ai/concrete (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Chillotti, I.; Gama, N.; Georgieva, M.; Izabachène, M. TFHE: Fast Fully Homomorphic Encryption Over the Torus. Journal of Cryptology 2020, 33, 34–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, C. Fully Homomorphic Encryption Using Ideal Lattices. Proceedings of the Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing 2009, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chillotti, I.; Gama, N.; Georgieva, M.; Izabachène, M. Faster Fully Homomorphic Encryption: Bootstrapping in Less than 0.1 Seconds. Cryptology ePrint Archive 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tassoni, P. A Fully Homomorphic Encryption Application: SHA256 on Encrypted Input. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zama - Open Source Cryptography. Available online: https://www.zama.ai/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- MLIR. Available online: https://mlir.llvm.org/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Microsoft SEAL: Fast and Easy-to-Use Homomorphic Encryption Library. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/project/microsoft-seal/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- IBM Z Content Solutions | Fully Homomorphic Encryption. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/z-content-solutions/fully-homomorphic-encryption/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Feng, X.M.; Li, X.D.; Zhou, S.Y.; Jin, X. Homomorphic Comparison Method Based on Dynamically Polynomial Composite Approximating Sign Function. 2023 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security, CNS 2023; 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Kim, S.; Choi, J.; Lee, Y.; Cheon, J.H. Efficient Sorting of Homomorphic Encrypted Data with K-Way Sorting Network. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2021, 16, 4389–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvi, N.B.; Shylashree, N. Innovative Homomorphic Sorting of Environmental Data in Area Monitoring Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 59260–59272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, H. An Efficient Fully Homomorphic Encryption Sorting Algorithm Using Addition Over TFHE. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems - ICPADS; 2023; 2023-Janua, pp. 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Chang, X.; Mišić, J.; Mišić, V.B.; Wang, J.; Zhu, H. Practical Solutions in Fully Homomorphic Encryption: A Survey Analyzing Existing Acceleration Methods. Cybersecurity 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergerat, L.; Boudi, A.; Bourgerie, Q.; Chillotti, I.; Ligier, D.; Orfila, J.-B.; Tap, S. Parameter Optimization and Larger Precision for (T)FHE. J. Cryptol. 2023, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, R.; Kurt Peker, Y.; Mutlu, Z.D. Blockchain and Homomorphic Encryption for Data Security and Statistical Privacy. Electronics 2024, 13, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 2.

Implementation of Bubble Sort Algorithm.

Figure 2.

Implementation of Bubble Sort Algorithm.

Figure 3.

Implementation of Odd-Even Sort Algorithm.

Figure 3.

Implementation of Odd-Even Sort Algorithm.

Figure 4.

Implementation of Bitonic Sort Algorithm.

Figure 4.

Implementation of Bitonic Sort Algorithm.

Figure 5.

Comparison of mean calculation time with respect to number of data points (represented by n) and their range.

Figure 5.

Comparison of mean calculation time with respect to number of data points (represented by n) and their range.

Figure 6.

Comparison of variance calculation time with respect to number of data points (represented by n) and their range.

Figure 6.

Comparison of variance calculation time with respect to number of data points (represented by n) and their range.

Figure 7.

Comparison of sorting algorithms with respect to number of data points and their range.

Figure 7.

Comparison of sorting algorithms with respect to number of data points and their range.

Figure 8.

Comparison of sorting algorithms with respect to number of data points and their range.

Figure 8.

Comparison of sorting algorithms with respect to number of data points and their range.

Figure 9.

Comparison of five-point summary calculation with respect to number of data points and their range using bitonic sort algorithm.

Figure 9.

Comparison of five-point summary calculation with respect to number of data points and their range using bitonic sort algorithm.

Figure 10.

Comparison of five-point summary calculation with respect to number of data points and their range using bubble sort algorithm.

Figure 10.

Comparison of five-point summary calculation with respect to number of data points and their range using bubble sort algorithm.

Figure 11.

Comparison of mode calculation with respect to number of data points and their range.

Figure 11.

Comparison of mode calculation with respect to number of data points and their range.

Table 1.

Timing of calculating mean on encrypted data.

Table 1.

Timing of calculating mean on encrypted data.

| Range of Data Points |

Number of Data Points |

Average Time (seconds) |

| 15 |

250 |

0.2591563225 |

| 15 |

500 |

0.2949240685 |

| 15 |

750 |

0.38118453 |

| 15 |

1000 |

0.4087949276 |

| 25 |

250 |

0.2753661633 |

| 25 |

500 |

0.396542263 |

| 25 |

750 |

0.3986121178 |

| 25 |

1000 |

0.4104460239 |

| 50 |

250 |

0.383390665 |

| 50 |

500 |

0.3923248768 |

| 50 |

750 |

0.4271043301 |

| 50 |

1000 |

0.5118193626 |

| 100 |

250 |

0.4524414539 |

| 100 |

500 |

0.4589883327 |

| 100 |

750 |

0.5494303226 |

| 100 |

1000 |

0.5682396412 |

| 150 |

250 |

0.4333281517 |

| 150 |

500 |

0.5372673035 |

| 150 |

750 |

0.545094347 |

| 150 |

1000 |

0.5996977806 |

| 200 |

250 |

0.4320604324 |

| 200 |

500 |

0.5359194756 |

| 200 |

750 |

0.5851401329 |

| 200 |

1000 |

0.6423121452 |

| 255 |

250 |

0.4070921421 |

| 255 |

500 |

0.5407989502 |

| 255 |

750 |

0.6363827229 |

| 255 |

1000 |

0.6393474102 |

Table 2.

Timing of calculating variance on encrypted data.

Table 2.

Timing of calculating variance on encrypted data.

| Range of Data Points |

Number of Data Points |

Average Time (seconds) |

| 5 |

5 |

1.246793652 |

| 5 |

10 |

3.375664091 |

| 5 |

15 |

33.91963091 |

| 10 |

5 |

3.607125664 |

| 10 |

10 |

10.76089249 |

| 15 |

5 |

3.438992119 |

| 25 |

5 |

3.458190584 |

Table 3.

Timing of sorting an encrypted array using bubble sort, odd-even sort and bitonic sort algorithms.

Table 3.

Timing of sorting an encrypted array using bubble sort, odd-even sort and bitonic sort algorithms.

| Range of Data Points |

Number of Data Points |

Bubble Sort |

Odd-Even Sort |

Bitonic Sort |

| 15 |

4 |

0.9289829731 |

0.7964228153 |

0.8072038174 |

| 15 |

8 |

3.802570963 |

3.864653492 |

3.272667646 |

| 15 |

16 |

24.73645005 |

24.69945812 |

16.30537062 |

| 25 |

4 |

2.856794691 |

2.788843584 |

2.765028334 |

| 25 |

8 |

12.97878513 |

13.01196995 |

11.17189612 |

| 25 |

16 |

56.15869894 |

55.68540888 |

37.06650977 |

| 50 |

4 |

6.555260181 |

6.388585186 |

6.457304382 |

| 50 |

8 |

28.90009408 |

29.26282926 |

25.16641912 |

| 50 |

16 |

130.86719 |

129.7057092 |

86.97843432 |

| 100 |

4 |

17.98627133 |

18.19524159 |

17.79985828 |

| 100 |

8 |

75.5639575 |

76.38956137 |

66.86756725 |

| 100 |

16 |

343.5751762 |

339.6416773 |

225.6959048 |

Table 4.

Timing of sorting an encrypted array using bubble sort, and odd-even sort.

Table 4.

Timing of sorting an encrypted array using bubble sort, and odd-even sort.

| Range of Data Points |

Number of Data Points |

Bubble Sort |

Odd-Even Sort |

| 15 |

5 |

1.537935781 |

1.378816271 |

| 15 |

10 |

6.759463835 |

10.02927947 |

| 15 |

15 |

21.59084606 |

21.59491601 |

| 25 |

5 |

4.542301035 |

4.644551325 |

| 25 |

10 |

20.7969069 |

20.76616225 |

| 25 |

15 |

49.09692616 |

49.09074335 |

| 50 |

5 |

10.75415287 |

10.73756552 |

| 50 |

10 |

47.21169949 |

47.18740268 |

| 50 |

15 |

110.4754518 |

110.6606554 |

| 100 |

5 |

26.53084812 |

26.59446735 |

| 100 |

10 |

120.4038908 |

121.4246564 |

| 100 |

15 |

283.6238332 |

291.6370564 |

Table 5.

Timing of calculating five-point summary of encrypted data including sorting with bitonic sort algorithm.

Table 5.

Timing of calculating five-point summary of encrypted data including sorting with bitonic sort algorithm.

| Range of Data Points |

Number of Data Points |

Average Time (seconds) |

| 15 |

4 |

0.9810014725 |

| 15 |

8 |

3.417602873 |

| 15 |

16 |

17.51649423 |

| 25 |

4 |

2.912345314 |

| 25 |

8 |

11.7951118 |

| 25 |

16 |

39.08947101 |

| 50 |

4 |

6.989213991 |

| 50 |

8 |

26.62157102 |

| 50 |

16 |

90.04364886 |

| 100 |

4 |

16.12305002 |

| 100 |

8 |

64.05258303 |

| 100 |

16 |

218.2426797 |

Table 6.

Timing of calculating five-point summary of encrypted data including sorting with bubble sort algorithm.

Table 6.

Timing of calculating five-point summary of encrypted data including sorting with bubble sort algorithm.

| Range of Data Points |

Number of Data Points |

Average Time (seconds) |

| 15 |

5 |

1.417282438 |

| 15 |

10 |

6.477654457 |

| 15 |

15 |

23.12285528 |

| 25 |

5 |

5.151349926 |

| 25 |

10 |

21.98973017 |

| 25 |

15 |

52.02675552 |

| 50 |

5 |

11.52323828 |

| 50 |

10 |

49.68436537 |

| 50 |

15 |

116.3990614 |

| 100 |

5 |

27.65277104 |

| 100 |

10 |

122.0125351 |

| 100 |

15 |

282.037562 |

Table 7.

Timing of calculating mode on encrypted data.

Table 7.

Timing of calculating mode on encrypted data.

| Range of Data Points |

Number of Data Points |

Average Time (seconds) |

| 15 |

5 |

1.134563398 |

| 15 |

10 |

2.909134007 |

| 15 |

15 |

5.814851332 |

| 25 |

5 |

1.949247265 |

| 25 |

10 |

7.032726526 |

| 25 |

15 |

14.75217366 |

| 50 |

5 |

5.563875389 |

| 50 |

10 |

15.28342657 |

| 50 |

15 |

29.15656028 |

| 100 |

5 |

12.18101587 |

| 100 |

10 |

36.2555759 |

| 100 |

15 |

60.19268651 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).