Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

-

We start by doing the state of the art overtime with:

- -

- Time according to I. Newton,

- -

- Relativistic time mixed with space-time according to the special relativity of A. Einstein,

- -

- The time bent by gravitation according to the general relativity of A. Einstein.

- 2

-

Then we look at contemporary developments on time, all published in reputable peer-reviewed journals:

- -

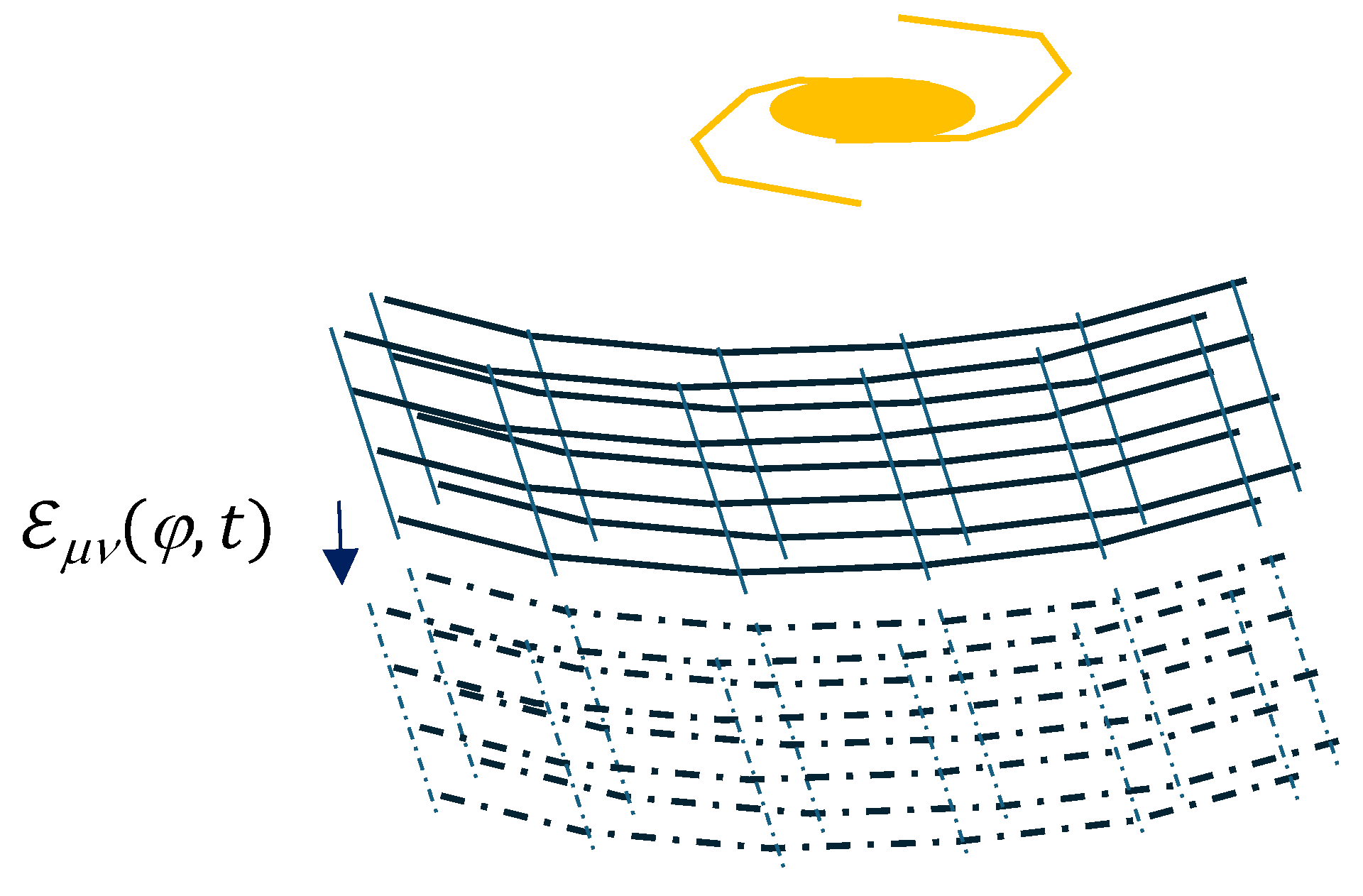

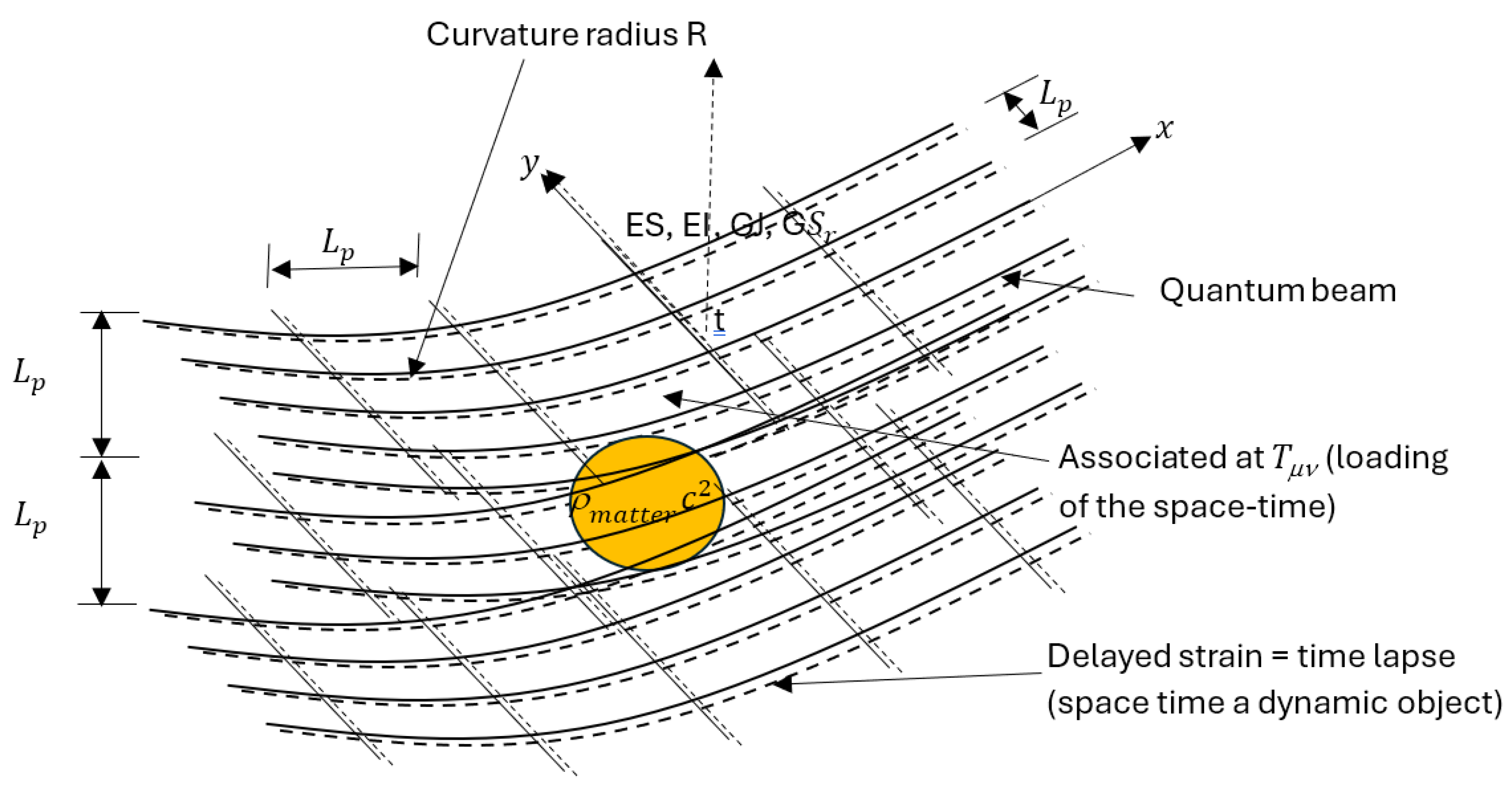

- Elastic time in the context of the analogy of space-time with an elastic medium,

- -

- Temperature-sensitive space-time according to Hawking radiation to temperature-sensitive elastic time,

- -

- Creep-sensitive elastic space-time and consequences on time,

- -

- Plasticity of the elastic medium and infinite stretching of time,

- -

- Time as an illusion with quantum gravity,

- -

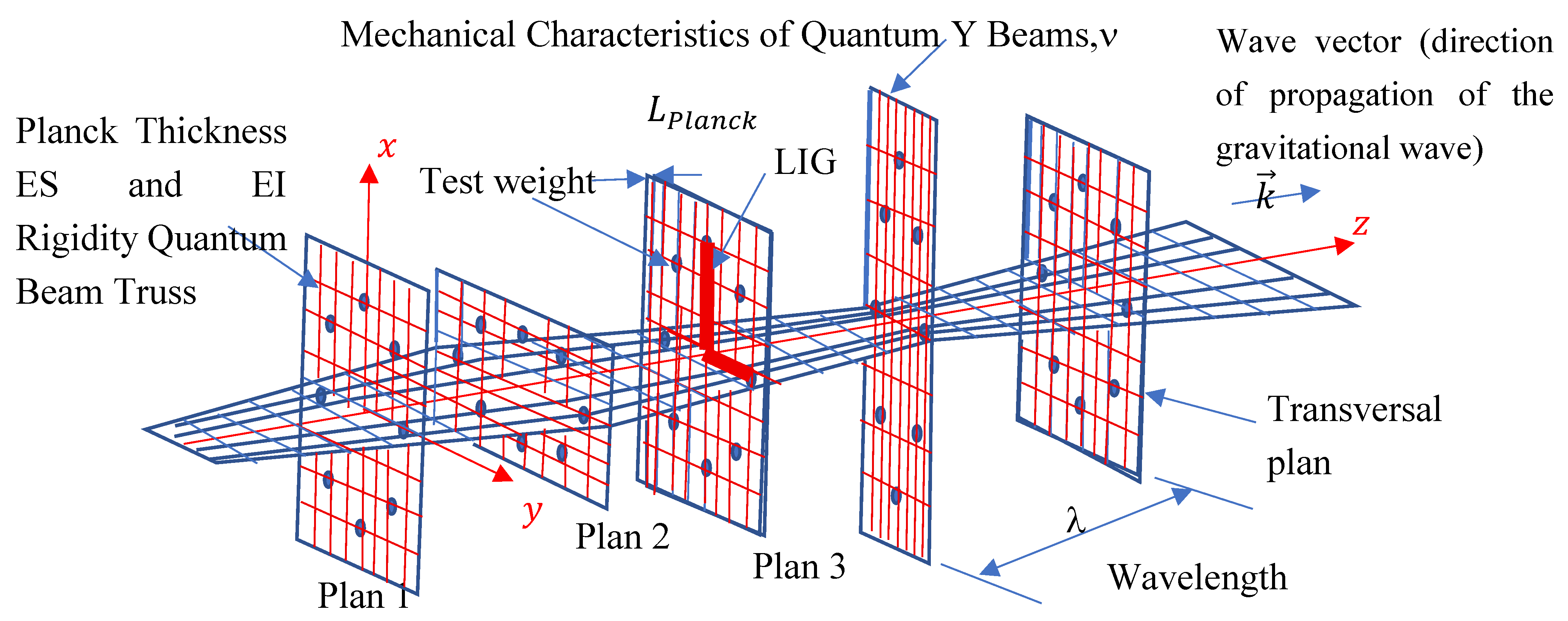

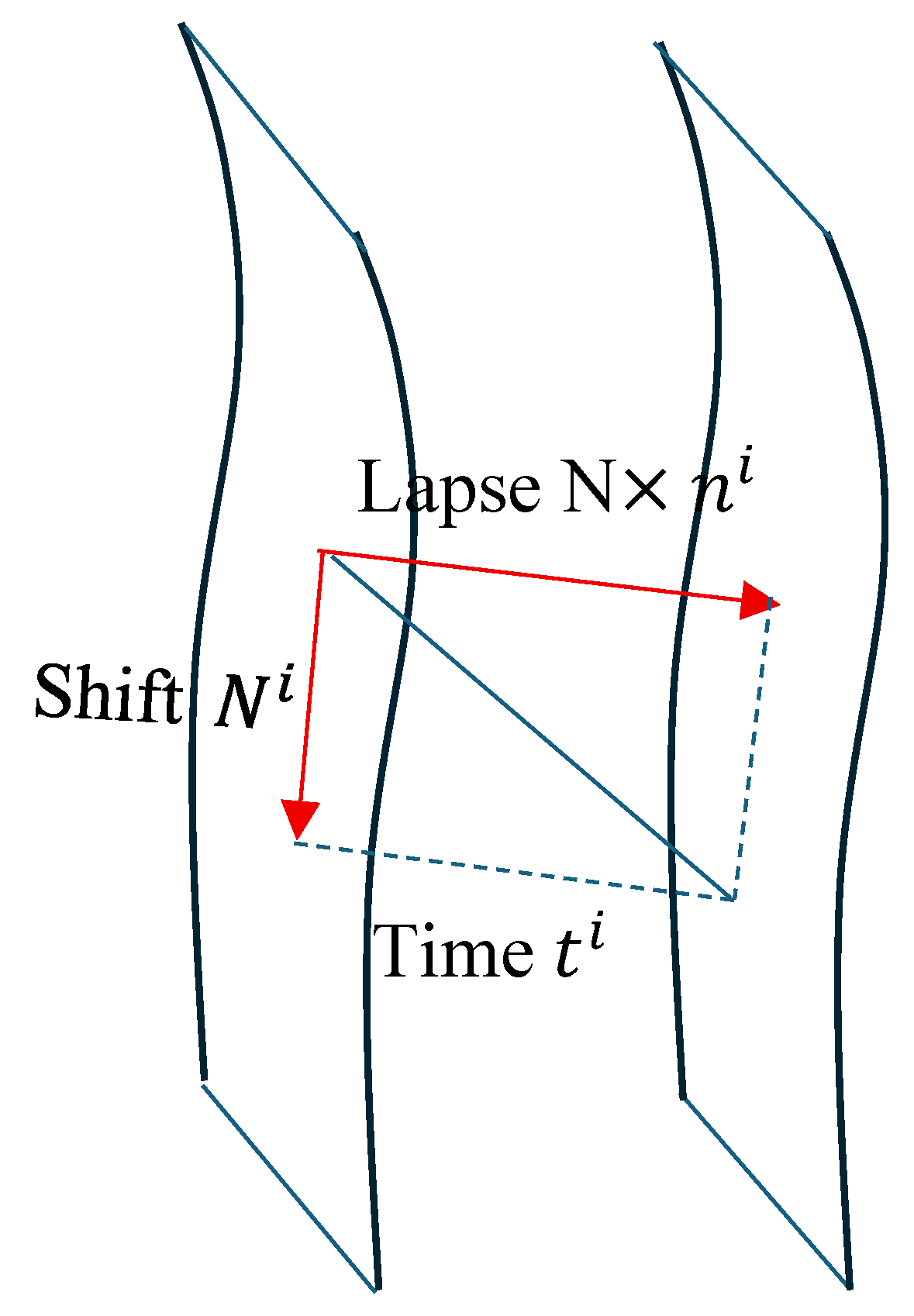

- Foliation of space-time and time lapse in the case of gravitational waves - Modified theory of general relativity with addition of Einstein Cartan geometric torsion,

- 3

-

In the context of a Discussion about elastic medium analogy, we highlight the different consequences implied by the different research studied in 2:

- -

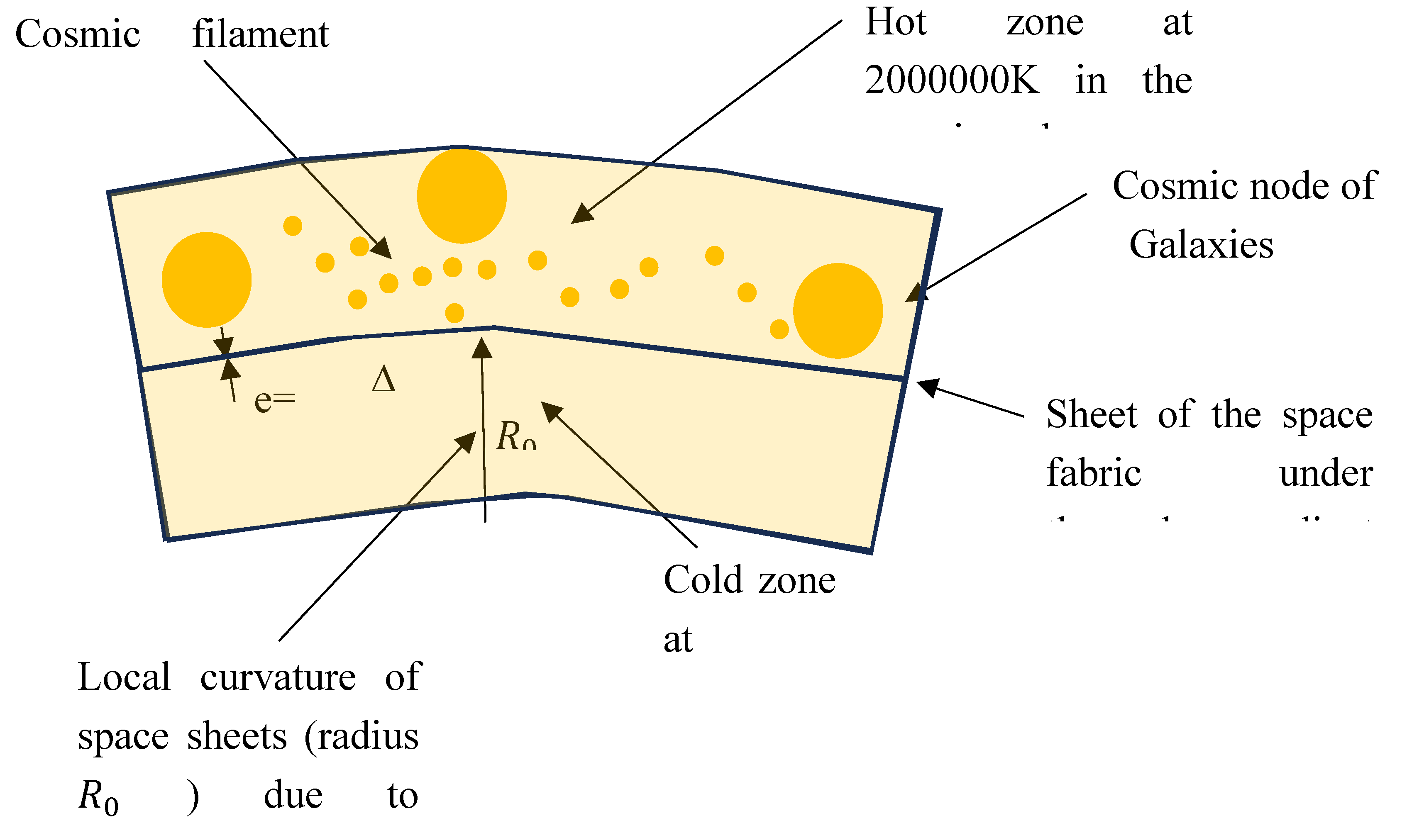

- Consequence of a variation of time and space as a function of temperature in connection with dark energy,

- -

- Consequence of a variation of time and space by creep of space-time in connection with dark matter,

- -

- Consequence of the foliation of space-time on the nature of time in the case of an equivalent elastic medium in connection with the possible emerging mechanistic nature of time.

3. State of the Art

3.1. Time According to I. Newton

3.2. Relativistic Time Mixed with Space-Time According to A. Einstein

3.3. The Time Bent by Gravitation According to the General Relativity of A. Einstein

4. Contemporary Developments Over Time

4.1. Elastic Time in the Context of the Space-Time Analogy with an Elastic Medium

4.1.1. Elastic Analogy and Theory

4.1.2. Experimental Validation

4.1.3. Predictive Power of the Model

4.2. Temperature-Sensitive Space-Time According to Hawking Radiation to Temperature-Sensitive Elastic Time?

4.2.1. Elastic Analogy and Theory

4.2.2. Experimental Validation

4.3. Elastic Space-Time Sensitive to Creep and Consequences on Time?

4.3.1. Elastic Analogy and Theory

4.3.2. Experimental Validation

4.4. Plasticity of the Elastic Medium and Infinite Stretching of Time

4.5. Time as an Illusion with Quantum Gravity

4.6. Space-Time Lamination and Time Lapse in the Case of Gravitational Waves – Einstein Cartan’s Modified Theory of General Relativity

- The lapse , which measures the normal proper time interval at between two hypersurfaces;

- The shift, which describes the spatial shift of points from one hypersurface to another.

- the Hamiltonian stress H≈0, which generates the normal evolution at the surface (via lapse),

- ≈0 moment constraints, which describe tangent rearrangements (via shift).

- There is a relativity of time: no absolute time, but a plurality of internal "clocks" depending on the choices of lapse and shift.

- Time is dynamic: it corresponds to the successive sliding of spatial hypersurfaces, which reflects the evolution of the gravitational metric.

5. Discussion

5.1. Consequence of a Variation in Time and Space as a Function of Temperature

5.2. Consequence of a Variation in Time and Space by Creep of Space-Time

5.3. Consequence of the Foliation of Space-Time on the Nature of Time in the Case of an Equivalent Elastic Medium

- a)

- b)

- Then, according to special relativity, time expands [2].

- c)

- In general relativity, time can indeed be associated with deformation, and we have seen that this translates into the 00 component of the tensors involved in general relativity [12] [13] [18] [20] [21]. And we have seen that time can be expressed from this deformation in the 4th dimension of general relativity .

- d)

- e)

- Finally, in physics, time is defined as the ratio between distance and speed

- -

- -

- -

- -

- The creep of space-time increases gravitation and therefore the curvatures and therefore the distances to be covered to transmit information with respect to an initial length L [61].

- -

- In a black hole, time dilates, until it seems to stop since the deformation enters the plastic regime and stretches to infinity.

6. Limitations and Future Challenges

7. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newton, I. philosophiae naturalis Principia Mathematica 1687.

- Einstein, A. Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper. Annalen der Physik, 26 septembre 1905,17, pp. 891–921.

- Einstein, A. Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation Sitzungsberichte der Königlich. Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2 décembre 1915, 2, pp. 844–847.

- Einstein, A. Die Grundlage der allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie. Annalen der Physik, 1916, Serie IV, 49, pp. 769–822.

- Sakharov, A. D. Vacuum Quantum Fluctuations in Curved Space and the Theory of Gravitation. Soviet Physics – Doklady, 1968, 12, pp. 1040–1041. [CrossRef]

- Synge, J.L. A Theory of Elasticity in General Relativity. Mathematische Zeitschrift of. phy. Sc. 1959, 72, pp. 82–87.

- Rayner, C.B. Elastic and thermoelastic media in general relativity, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 1963, 272, 1350, pp. 44–54.

- Grot, R. A.; Eringen, A. C. Relativistic Continuum Mechanics – Part I: Mechanics and Thermodynamics. International Journal of Engineering Science,1966, 4, pp. 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Vasiliev, V. V.; Fedorov L. V. Relativistic Theory of Elasticity. Mechanics of Solids,2018, 53, pp. 256–261.

- Vasiliev, V. V.; Fedorov L. V. Analogy Between the Equations of Elasticity and the General Theory of Relativity. Mechanics of Solids,2021, 56, pp. 404–413.

- David Brown, J. Relativistic Elasticity II. Classical and Quantum Gravity,2012, 29, 8, Article ID: 085017, pp. 1–20.

- Tenev, T.G. An Elastic Constitutive Model of Spacetime and its Applications. Doctoral Dissertation, Mississippi State University, James Worth Bagley College of Engineering, Department of Computational Engineering.2018.

- Tenev, T. G.; Horstemeyer, M. F. Mechanics of Spacetime: A Solid Mechanics Perspective on the Theory of General Relativity. International Journal of Modern Physics D, 2018, 27, No. 8, 1850083. [CrossRef]

- Beau, M. On the acceleration of the expansion of a cosmological medium.Prépublication sur arXiv.2018 : arXiv:1805.03020.

- Kirk T. McDonald. What is the Stiffness of Spacetime? Joseph Henry Laboratories, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544.2018.

- A.C. Melissinos. Upper limit on the Stiffness of space-time. Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA. Prépublication sur arXiv.2018: arXiv:1806.01133.

- Pierre A. Millette . Elastodynamics of the Spacetime Continuum (STCED). American Research Press, Rehoboth, New Mexico, USA.2019.

- Izabel, D. Mechanical conversion of the gravitational Einstein’s constant κ. Pramana – Journal of Physics- Indian Academy of Sciences, 2020, 94, Article 119.

- Izabel, D. What is Space-Time Made of? EDP Sciences, Collection Current Natural Sciences, Les Ulis, France.2021.

- Izabel, D.; Rémond, Y.; & Ruggiero, M. L. Some geometrical aspects of gravitational waves using continuum mechanics analogy: State of the art and potential consequences. Mathematics in Engineering, Mechanics and Computer Science (MEMOCS),2025, 13, 2, pp. 201–236.

- Izabel, D.; Rémond, Y.; & Ruggiero, M. L. Elastic Medium Analogy of Spacetime: hµν Metric Perturbation Tensor Analysis and Theoretical Implications. International Journal of Theoretical Physics,2025, 64, Article 186. [CrossRef]

- Damour, T. General Relativity Today. In: Duplantier, B., Rivasseau, V. (eds), Gravitation and Experiment: Poincaré Seminar 2006, Progress in Mathematical Physics,2006, 52, pp. 1–40.

- Damour, T. Si Einstein m’était conté... Éditions Flammarion, Collection Champs Sciences, Paris.2016.

- T. Damour. conférence sur Les ondes gravitationnelles Banyuls sur mer explication de l’ancien et nouvel ether durant séance des questions. 2017 1 :03 :14 - 1 :05 :37. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oYOnBLjo7IM.

- Landau, L. D. ; & Lifchitz, E. M.Théorie de l’élasticité (Vol. 7 de la série Physique Théorique). Éditions Mir, Moscou. Traduit du russe par Edouard Oloukhian.1967.

- Misner, C. W. ; Thorne, K. S.; & Wheeler, J. A. Gravitation. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Company.1973.

- Michelson, A. A.; Morley, E. W. On the Relative Motion of the Earth and the Luminiferous Ether. American Journal of Science,1887, Vol. 34,203, pp. 333–345.

- Hafele, J.C. – Relativistic Time for Terrestrial Circumnavigations, publié dans American Journal of Physics,1972, 40, No. 1, pp. 81–85.

- Hafele, J.C.; Keating R.E. – Around-the-World Atomic Clocks: Predicted Relativistic Time Gains, Science,1972a, 177, No. 4044, pp. 166–168.

- Hafele, J.C.; Keating R.E. (1972b) – Around-the-World Atomic Clocks: Observed Relativistic Time Gains, Science,1972b, 177, 4044, pp. 168–170.

- Einstein, A. Näherungsweise Integration der Feldgleichungen der Gravitation. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 22 juin 1916, pp. 688–696.

- Shapiro, I.I. Fourth Test of General Relativity. Physical Review Letters 13.789, 28 décembre 1964, 13, pp. 789–791.

- Casimir, H.B.G. On the attraction between two perfectly conducting plates. Proc. Kon. Ned. Akad. Wetensch,1948, 51, pp. 793–795.

- Lamoreaux, S.K. Demonstration of the Casimir Force in the 0.6 to 6 μm Range. Physical Review Letters,1997, 78, pp. 5–8. [CrossRef]

- Higgs, P. Higgs, P.W. Broken Symmetries and the Masses of Gauge Bosons. Physical Review Letters, 19 octobre 1964, 13, pp. 508–509.

- Englert, F. Brout, R. Broken Symmetry and the Mass of Gauge Vector Mesons. Physical Review Letters, 31 août 1964, 13, pp. 321–323.

- ATLAS Collaboration & CMS Collaboration. The Higgs Boson Discovery. Scholarpedia, 2015,10, Article 32413.

- Ruggiero, M.L.; Tartaglia, A. Einstein-Cartan theory as a theory of defects in spacetime, American Journal of Physics,2003, 71, 1303-1313.

- Kleinert, H. Emerging gravity from defects in world crytal, Brazilian Journal of Physics,2005, 35 (2a).

- Capozziello, S.; Lambiase,G.; Stornaiolo, C. Geometric classification of the torsion tensor in space-time; Annalen der Physik,2001, 10, 713-727.

- Shrikanth, S.; Knowles, K. M.; Neelakantan, S.; Prasad, R. Planes of isotropic Poisson’s ratio in anisotropic crystalline solids, International Journal of Solids and Structures,2020, 191-192, 628-645.

- TAHIM, M. O.; LANDIM, R. R.; ALMEIDA, C. A. S. space time as a deformable solid. Modern Physics Letters A,2009,24, No. 15, pp. 1209-1217 Research Papers.

- Lobo, F. S. N.; Olmo, G. J.; Rubiera-Garcia, D. Crystal clear lessons on the microstructure of space-time and modified gravity. Phys. Rev. D, 2015, 91, 124001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, F.W.; Eddington, A.S.; Davidson, C.A. Determination of the Deflection of Light by the Sun’s Gravitational Field, from Observations Made at the Total Eclipse of May 29, 1919.Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, 1920, 220, pp. 291–333.

- Luminet, J.P Des accidents ordinaires de l’espace-temps: les trous noirs Panorama LUTH Observatoire de paris, 2009, pp182 – 193.

- B. P. Abbott1, R. Abbott1, T. D. Abbott2, M. R. Abernathy1, F. Acernese3,4, K. Ackley5, C. Adams6, T. Adams7, P. Addesso3 et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and VIRGO Collaboration) (2016) Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger Physical review letter,2016, 116, 061102.

- B. P. Abbott, R. Abbott, T. D. Abbott, F. Acernese, K. Ackley, C. Adams, T. Adams, P. Addesso, R. X. Adhikari et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and VIRGO Collaboration) (2017) GW170817: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Neutron Star Inspiral. Phys. Rev. Lett,2017, 119, 161101.

- Hawking, S.W. Black holes aren’t black. Wellesley: Gravity Research Foundation, Essay awarded Honorable Mention in the 1974 Gravity Research Foundation Essay Competition.1974a.

- Hawking, S.W. Black hole explosions? Nature,1974b, 248(5443), pp. 30–31.

- Hawking, S.W. Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 1975, 43(3), pp.199–220.

- Hawking, S.W. Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics,1976, 46, 206.

- Lucia, U.; Grisolia, G. (2020). Time & clocks: A thermodynamic approach. Results in Physics,2020, 16, 102977.

- Chatterjee, A., & Iannacchione, G.Time and Thermodynamics: Extended Discussion on "Time & clocks: A thermodynamic approach". arXiv preprint,2020, arXiv:2007.09398v1.

- Shreyansh S. Dave, Oindrila Ganguly, P. S. Saumia and Ajit M. Srivastava, Hawking radiation from acoustic black holes in hydrodynamic flow of electrons. Europhysics Letters,2022, 139, Number 6.

- Izabel, D. Analogy of spacetime as an elastic medium—Can we establish a thermal expansion coefficient of space from the cosmological constant Λ? International Journal of Modern Physics,2023, D,32, 13, 2350091.

- Hernandez, H. On the Relationship between Time and Temperature. ForsChem Research Reports, 2019 ; Report No. FRR 2019-14.

- Hadi,H.; Atazadeh, K.; Darabi, F. Quantum time dilation in the near-horizon region of a black hole Physics. Letters. B.2022, 834 137471.

- Hauret, C.; Magain, P.; Biernaux, J. Cosmological Time, Entropy and Infinity MDPI. Entropy. 2017, 19, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chas. A. Eganc, H. Lineweaver,A LARGER ESTIMATE OF THE ENTROPY OF THE UNIVERSE, Astr. J.2010. 710, 1825–1834.

- Chatterjee, A.; Lannacchione, G. Time and Thermodynamics Extended Discussion on “Time & clocks: A thermodynamic approach”2020 arXiv:2007.09398v1 1 1.

- Izabel, D. Analogy of spacetime as an elastic medium — Estimation of a creep coefficient of space from space data via the MOND theory and the gravitational lensing effect — the ball cluster — and via time data from the GPS effect — comparison, discussion and implication of the results for dark matter and Einstein’s field equation. International Journal of modern physic D,2025, 34, No. 02 2450070.

- Lense, J.; Thirring, H. Über den Einflub der Eigenrotation der Zentrlkörper auf die Bewegung der Planeten und Monde nach der Einsteinschen gravitatiostheorie. Physik Zeitschr XIX,1918, 156.

- Everitt, C.W.F.; DeBra, D.B.; Parkinson, B.W.; Turneaure, J.P.; Conklin, J.W.; Heifetz, M.I.; Keiser,G.M.; Silbergleit, A.S.; Holmes, T.; Kolodziejczak, J.; Al-Meshari, M.; Mester, J.C.; Muhlfelder, B.,Solomonik, V.; Stahl, K.; Worden, P.; Bencze, W.; Buchman, S., Clarke, B., Al-Jadaan, A., Al-Jibreen,H., Li, J., Lipa, J.A., Lockhart, J.M., Al-Suwaidan, B.; Taber, M.; Wang, S.: Gravity Probe B: Final Results of a Space Experiment to test General Relativity. Physical Review Letter,2011; 106, 221101.

- M. L. Ruggiero, A. Tartaglia, Einstein-Cartan theory as a theory of defects in spacetime, American Journal of Physics 71,2003, 1303-1313.

- Gabriele Veneziano, "Construction of a crossing-symmetric, Regge-behaved amplitude for linearly rising trajectories", Il Nuovo Cimento A,1968, 57, 1968, pp190–97.

- C. Rovelli & L. Smolin, "Loop space representation for quantum general relativity", Nuclear Physics B,1990, 331, pp. 80–152.

- R. Arnowitt, S. Deser, and C. W. Misner, (1962) The Dynamics of General Relativity, Gen.Rel.Grav.2008, 40,pp.1997-2027.

- Chiang, Y.-K.; Makiya, R.; Ménard, B.; & Komatsu, E. "An observational probe of cosmic homogeneity using the fossil record of galaxies." The Astrophysical Journal, 2020, 902(1), 56.

- Milgrom, M., MOND theory, Canadian Journal Of Phys,2015, Vol, 93.

- Nasrulloh, H. Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) vs Newtonian Dynamics: The Simple Test to Solve the Constant Speed of Galaxy Rotation, Journal of Physical Science and Engineering);2022, 7, No. 1 pp 1–5.

- Rubin, D.; Perlmutter, S.; Aldering, G.; et al. Union through UNITY: Cosmology with 2000 SNe Using a Unified Bayesian Framework. The Astrophysical Journal,2025, 902(1), 56.

- Reichardt, C., et al Growing evidence for evolving dark energy could inspire a new model of the universe. Phys.org, 30 juin 2025.

- DESI 2024 VII: Cosmological Constraints from the Full-Shape Modeling of Clustering Measurements,2024, arXiv:2411.12022.

- Claeskens, J.F. These Aspect statistic du phénomène de lentille gravitationnelle dans un échantillon de quasars très lumineux Chapitre 2 Theorie du phenomene de mirage gravitationnel, Bulletin de la société royale des sciences de Liege 1998,1999, 68 (1-4), 1999.

- Weiss R. Nobel lecture 2017.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).