Submitted:

16 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

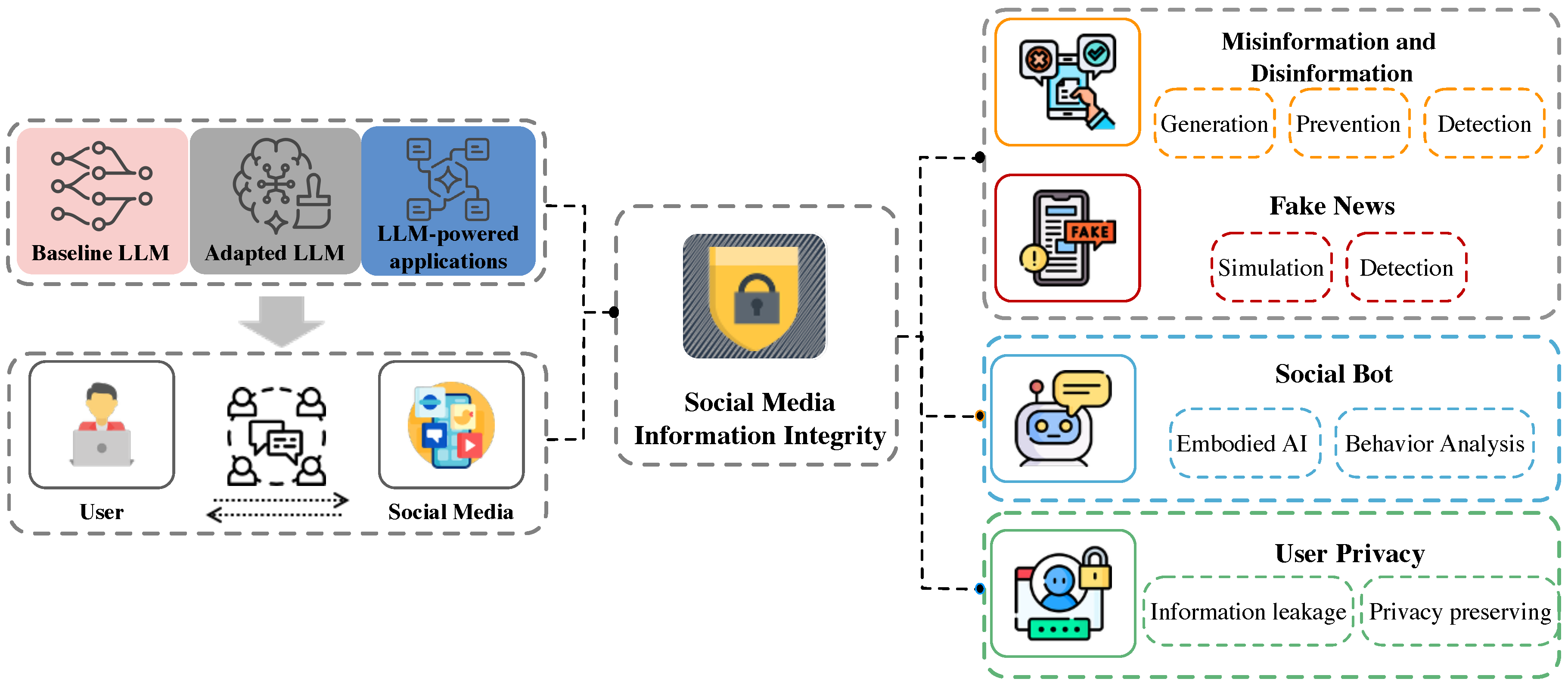

1. Introduction

- RQ1. What is the potential of LLMs in enhancing social media information integrity?

- RQ2. How do LLMs challenge the detection and mitigation of information integrity issues?

- RQ3. To what extent do ethical and security implications emerge from LLMs’ role in information integrity?

2. Backgrounds

2.1. What Are the Information Security Issues in Social Media?

| Category | Author and Year | Definition | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Misinformation | Altay et al. (2023)[7] | False and misleading information. | Academia |

| Wardle et al.(2017)[159] | Information that is false but not created with the intention of causing harm. | Academia | |

| UNHCR (2021)[155] | Misinformation is false or inaccurate information. Examples include rumors, insults, and pranks. | NGO | |

| Disinformation | Wardle et al.(2017)[159] | Information that is false and is knowingly shared to cause harm. | Academia |

| UNHCR (2021)[155] | Disinformation is deliberate and includes malicious content such as hoaxes, spear phishing, and propaganda. It spreads fear and suspicion among the population. | NGO | |

| Fake News | Cooke et al.(2017) [36] | False and often sensational information disseminated under the guise of news reporting, yet the term has evolved over time and has become synonymous with the spread of false information | Academic |

| Allcott et al. (2017) [5] | News articles that are intentionally and verifiably false and could mislead readers. | Academic | |

| Social Bot | Staab et al.(2023) [146] Lyu et al.(2023) [100] |

Social bots capable of inferring and utilizing multimodal capabilities, effectively processing and generating both textual and visual content. | Academic |

| Cloudflare (2025) [32] | Social bots are automated programs that mimic human users, operating partially or fully on their own, with many being used for deceptive or harmful purposes. | Industry | |

| User Privacy | Helen et al.(2019) [114] | The right of users to control information flows and disclosures about themselves according to contextual norms and social expectations. | Academia |

| Facebook (2023) [105] | Providing users transparency and practical control over how their personal data is collected, used, and shared, consistent with regulatory compliance. | Industry |

2.2. Why Does LLM Raise Information Security Issues in Social Media?

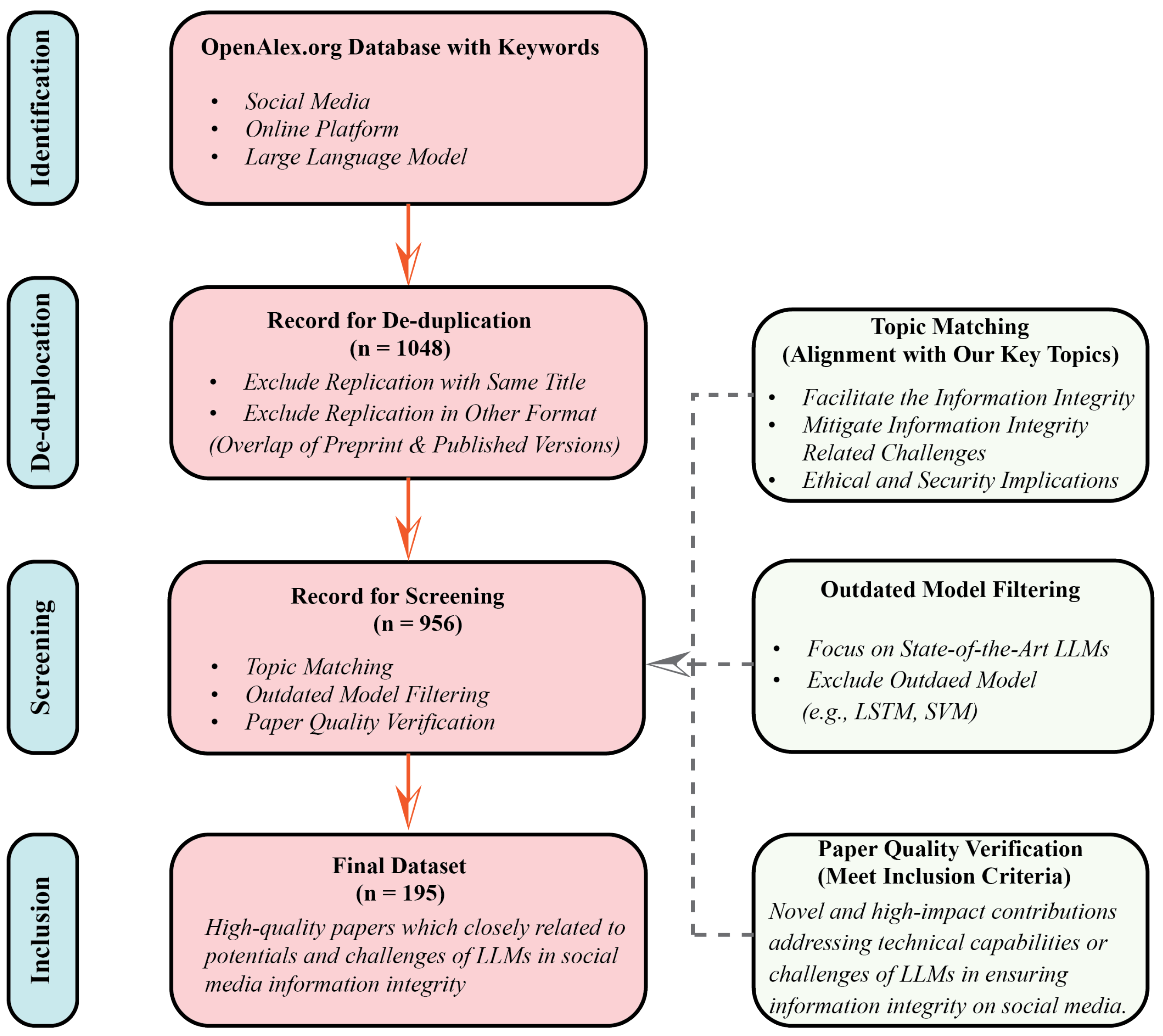

3. Data, Methods and Initial Findings

3.1. Data Preparation

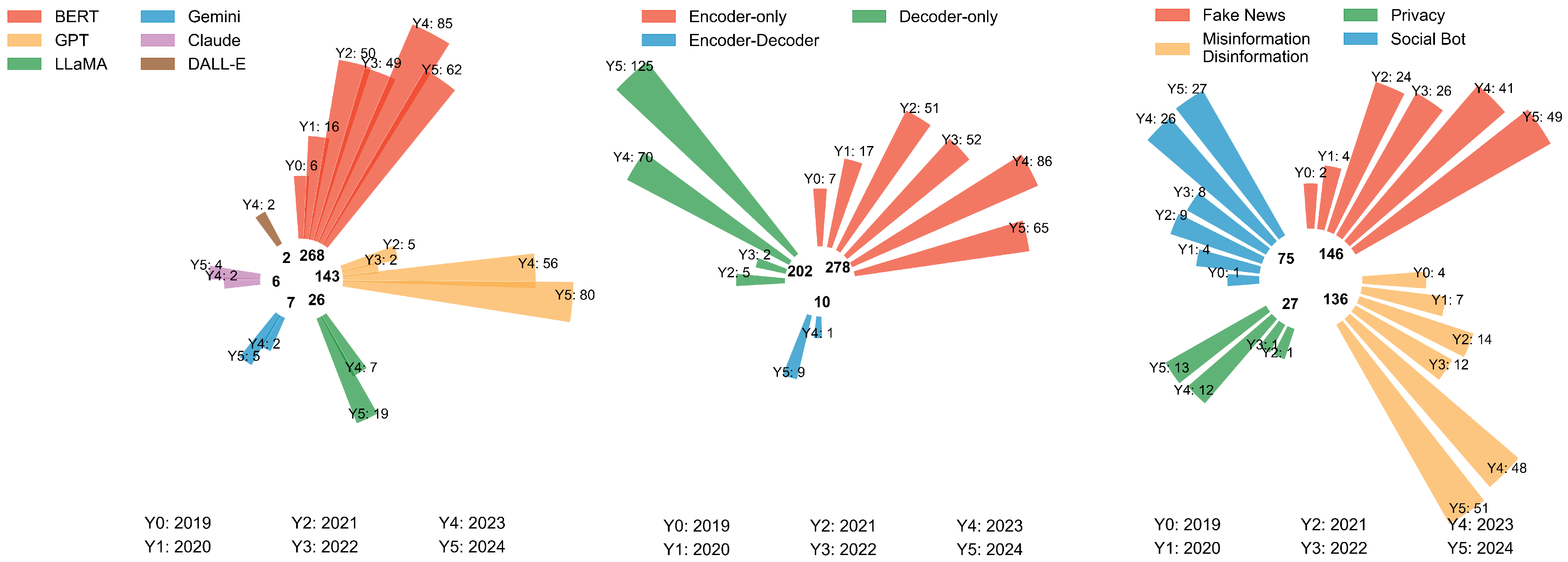

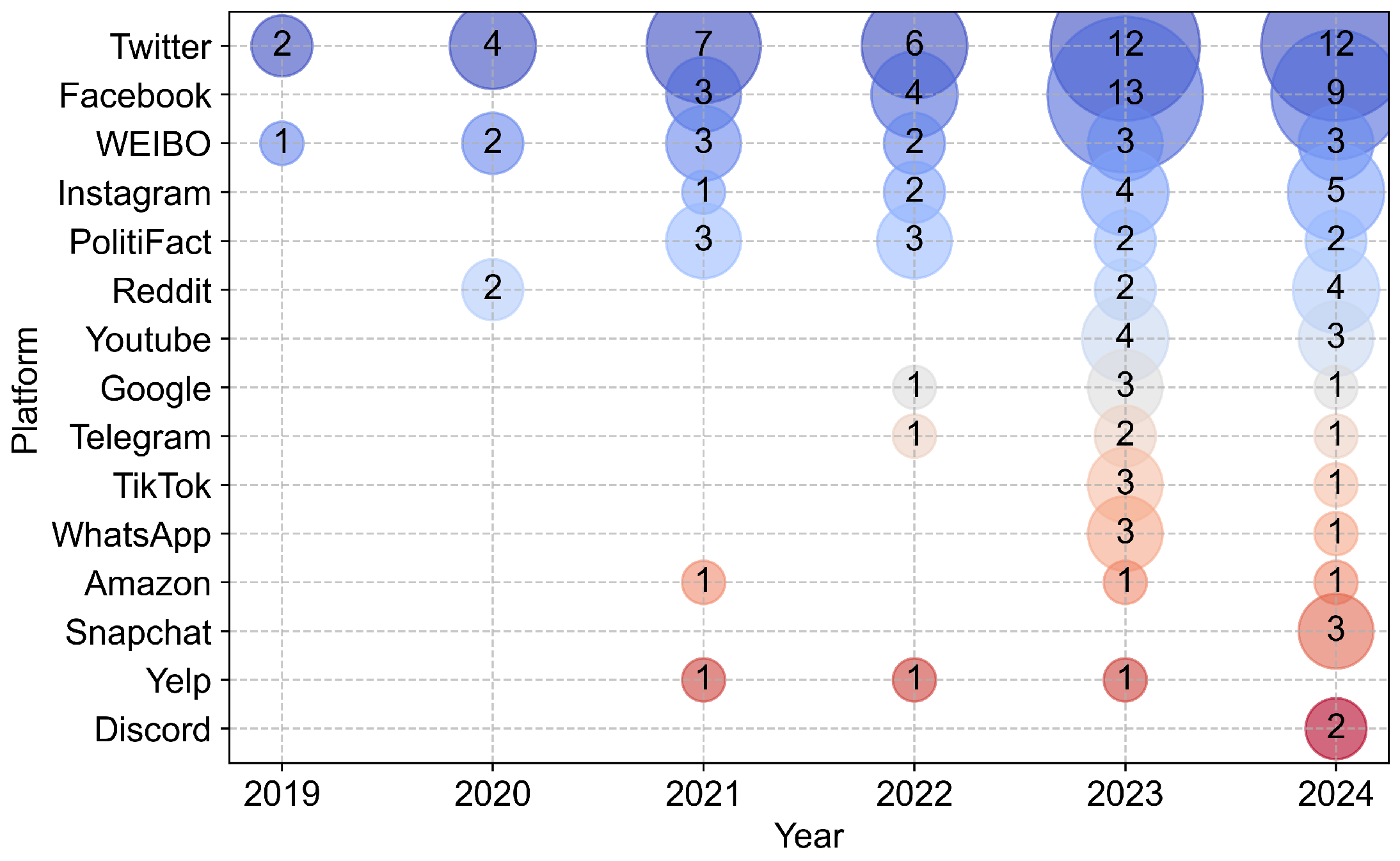

3.2. Data Description

4. Research Outlook

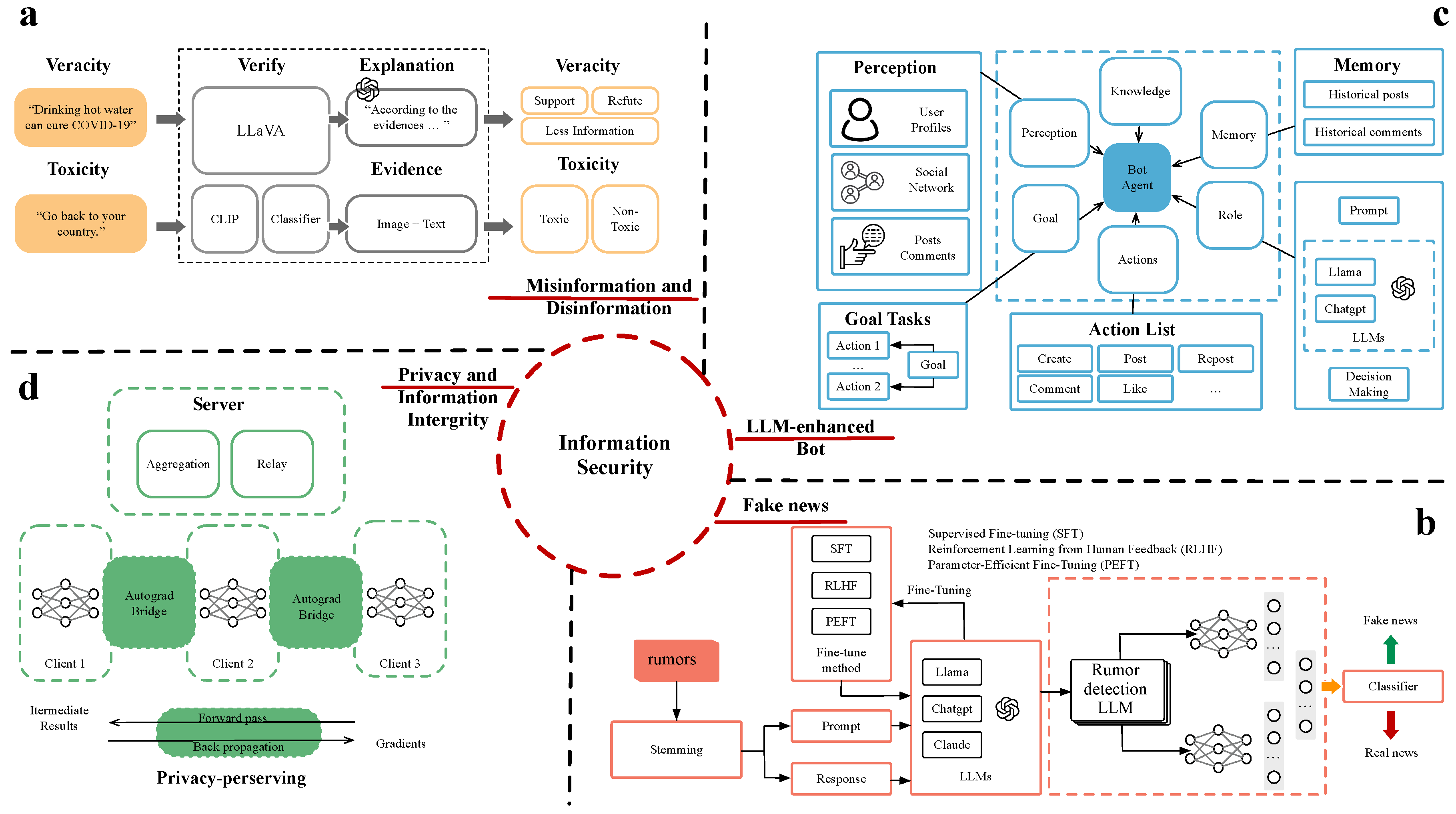

4.1. Topic 1: Information Disorder

4.1.1. Misinformation and Disinformation

4.1.2. Misinformation and Disinformation Potentials: How LLMs Enhance Detection and Prevention.

4.1.3. Misinformation and Disinformation Challenges.

Fake News Fake News |

Factual Correction Factual Correction |

|---|---|

| XStarbucks is sponsoring the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee. | ✓Social media users are claiming that Starbucks, known for taking strong positions in support of progressive political issues, is sponsoring the RNC. |

| XA bill signed into law this week by Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer prohibits vote recounts based on election fraud allegations. | ✓The bill, SB 603, does not prohibit such recounts, according to two state senators involved in updating the laws around recounts. It stipulates that candidates may request a recount if they have a “good-faith belief” that they would have had a “reasonable chance” to win the election if not for an “error” in the vote-counting process. That means that the number of votes the petitioning candidate requests to be recounted must be greater than the difference of votes between them and the winning candidate. |

| XA video shows President Joe Biden trying to sit in a chair that wasn’t there during a ceremony in Normandy, France, commemorating the 80th anniversary of D-Day. | ✓The video, in which Biden’s chair is for the most part clearly visible, is cut before the president sits down. Full footage of the ceremony shows the president looking over his shoulder for his chair and pausing before taking a seat. |

| XA video shows a worker at a voter registration drive in Florida registering people to vote without asking for proof of citizenship. | ✓Shortly before the U.S. House of Representatives on Wednesday passed a bill requiring proof of citizenship to register to vote, social media users shared a video of a voter registration drive in Palm Beach, Florida, to raise questions about noncitizens voting in U.S. elections. |

| Techniques | Model | Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer Learning |

BERT, RoBERTa, XLM-RoBERTa |

Text-based detection; rumor analysis; cross-lingual detection |

[35,37,97] [26,55,101] |

| Enhance Explainability |

DistilBERT +SHAP |

Enhancing model interpretability; explainable decision-making |

[135] [99] |

| Multi-modal Fusion |

BDANN, EANBS, FND-CLIP, ChatGPT |

Joint analysis of textual and visual information |

[137,176] [46,100] |

| Prompt-based Learning |

ChatGPT, GenFEND | Zero-shot classification; training data augmentation;debiasing |

[4] [66,113] |

| Few-shot Learning |

RumorLLM | Reducing annotation costs and improving performance in low -resource settings |

[84] |

| Privacy-preserving Learning |

AugFake-BERT | Collaborative training without data sharing, ensuring data privacy |

[78] |

| Domain Transfer Learning |

CT-BERT RoBERTa |

Domain-adaptive or region-specific misinformation detection |

[101] [147] |

4.1.4. Fake News Potentials: LLMs as Detection Tools

4.1.5. Fake News Emerging Challenges

4.2. Topic 2: Social Bot

4.2.1. Potential of LLM-Enhanced Bots in Information Integrity

| Techniques | Methods | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid neural Detection |

BERT+GCN, ALBERT+Bi-LSTM, Transformer method |

Advanced bot detection using hybrid neural architectures |

[83,162] [54,59] |

| Multilingual Processing |

XLM-RoBERTa, mBERT, Multilingual GPT |

Cross-lingual bot detection and content analysis across different languages and cultural contexts |

[51,116] [107] |

| Real-time Monitoring |

News Monitor, Moderation Systems |

Continuous monitoring and instant detection of malicious activities |

[115,126] [17] |

| Domain-specific Defense |

Child Protect Systems, Financial Monitors |

Specialized bot detection systems for specific sectors or use cases |

[73,133] [129] |

| Multimodal Analysis |

GPT-4V, CLIP-based Models |

Joint analysis of text, images, and other media types for comprehensive bot detection |

[100,104] |

| Privacy Preserving |

Federated Learning, Differential Privacy |

Collaborative bot detection while maintaining data privacy |

[121] |

| Proactive Prevention |

Sheaf Theory + LLMs, Topic Expansion |

Early warning and prevention systems before bot attacks occur |

[69,94] |

| Context-aware Detection |

SBERT + Topic Models Contextual Embeddings |

Understanding and analyzing bot behavior in specific contexts |

[9,94] |

| Hybrid Defense |

LSTM+BERT, Ensemble Methods |

Integration of multiple detection techniques for robust defense |

[6,134] |

4.2.2. Challenges and Risks of LLM-Enhanced Bots

4.3. Topic 3: Privacy

4.3.1. Potential in Privacy-Preserving Techniques to Guarantee Information Integrity

4.3.2. Privacy Challenges Arising from LLM-Induced Information Integrity Collapse

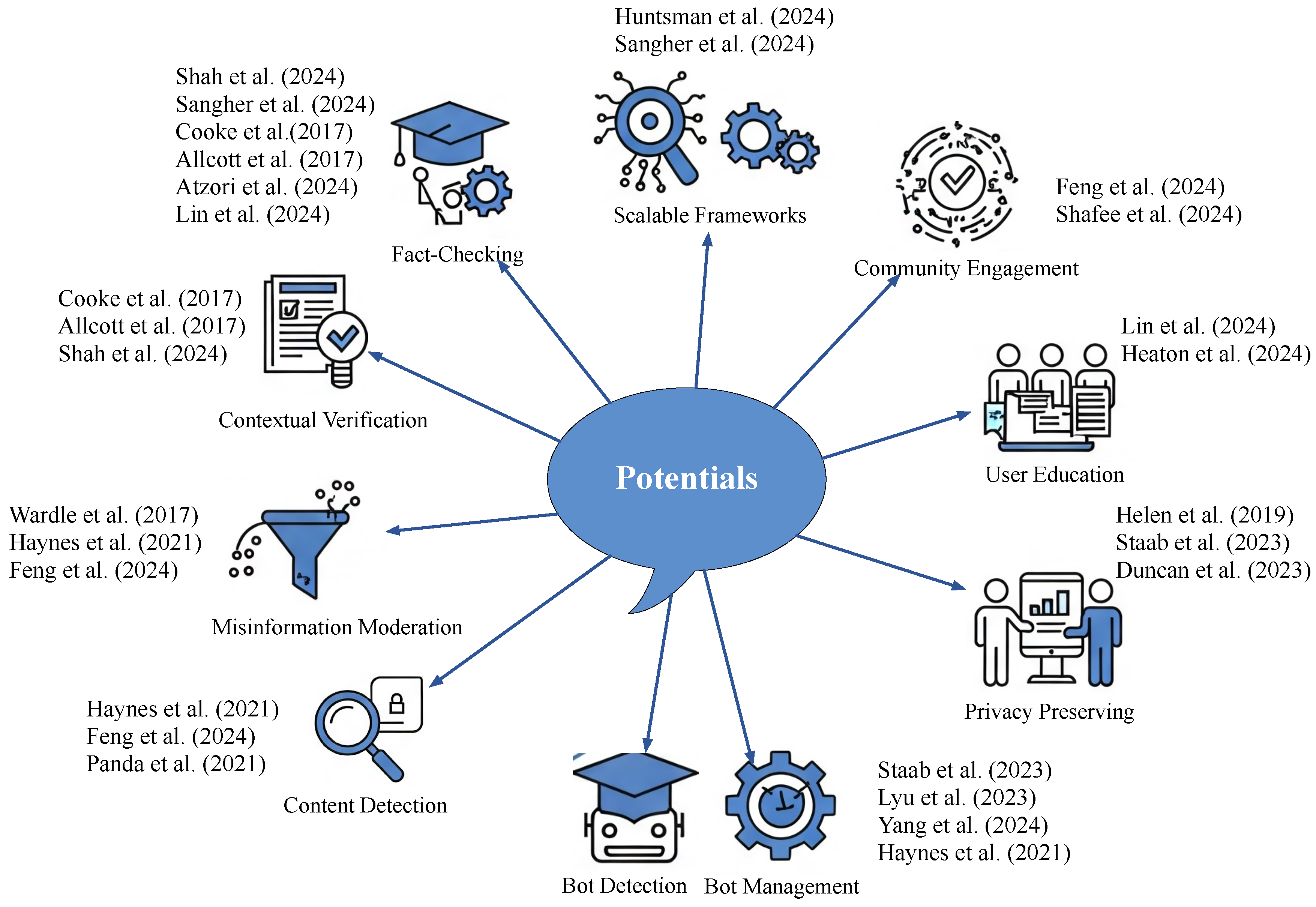

5. Landscape Analysis: Potentials and Challenges

5.1. Landscape: Opportunities in Social Media Information Integrity

Detect & Moderate Misinformation.

Multimodal Fact-Checking & Contextual Verification.

Bot Detection, Analysis & Management.

Privacy-Preserving Content Processing.

User Education & Media-Literacy Support.

Community Engagement & Collaborative Verification.

5.2. Landscape: Challenges in Social Media Information Integrity

Detection and Verification Challenges

Resource and Deployment Challenges

Privacy and Security Challenges

Fairness and Accountability Challenges

6. Discussion

6.1. Key Findings

6.2. Implications

6.3. Future Research

6.3.1. Information Disorder Detection

6.3.2. LLM-Enhanced Social Bot Detection

6.3.3. Privacy Preservation

7. Conclusions

References

- Kawsar Ahmed, Md Osama, Md Sirajul Islam, Md Taosiful Islam, Avishek Das, and Mohammed Moshiul Hoque. 2023. Score_IsAll_you_need at BLP-2023 task 1: A hierarchical classification approach to detect violence inciting text using transformers. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Bangla Language Processing (BLP-2023) (Singapore). Association for Computational Linguistics, Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 185–189.

- Hani Al-Omari, Malak Abdullah, Ola Al-Titi, and Samira Shaikh. 2019. Justdeep at nlp4if 2019 shared task: propaganda detection using ensemble deep learning models. EMNLP-IJCNLP 2019 (2019), 113.

- Hani Al-Omari, Malak Abdullah, Ola AlTiti, and Samira Shaikh. 2019. JUSTDeep at NLP4IF 2019 task 1: Propaganda detection using ensemble deep learning models. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Internet Freedom: Censorship, Disinformation, and Propaganda (Hong Kong, China). Association for Computational Linguistics, Stroudsburg, PA, USA.

- Jawaher Alghamdi, Yuqing Lin, and Suhuai Luo. 2024. Cross-domain fake news detection using a prompt- based approach. Future Internet 16, 8 (2024), 286. [CrossRef]

- Hunt Allcott and Matthew Gentzkow. 2017. Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of economic perspectives 31, 2 (2017), 211–236.

- Sawsan Alshattnawi, Amani Shatnawi, Anas M R AlSobeh, and Aws A Magableh. 2024. Beyond word-based model embeddings: Contextualized representations for enhanced social media spam detection. Appl. Sci. (Basel) 14, 6 (March 2024), 2254.

- Sacha Altay, Manon Berriche, Hendrik Heuer, Johan Farkas, and Steven Rathje. 2023. A survey of expert views on misinformation: Definitions, determinants, solutions, and future of the field. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 4, 4 (2023), 1–34.

- Dimitris Asimopoulos, Ilias Siniosoglou, Vasileios Argyriou, Thomai Karamitsou, Eleftherios Fountoukidis, Sotirios K Goudos, Ioannis D Moscholios, Konstantinos E Psannis, and Panagiotis Sarigiannidis. 2024. Benchmarking Advanced Text Anonymisation Methods: A Comparative Study on Novel and Traditional Approaches. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.14465 (2024).

- Hadi Askari, Anshuman Chhabra, Bernhard Clemm von Hohenberg, Michael Heseltine, and Magdalena Wojcieszak. 2024. Incentivizing news consumption on social media platforms using large language models and realistic bot accounts. PNAS Nexus 3, 9 (Sept. 2024), gae368. [CrossRef]

- Associated Press. 2025. AP Fact Check. https://apnews.com/ap-fact-check.

- Maurizio Atzori, Eleonora Calò, Loredana Caruccio, Stefano Cirillo, Giuseppe Polese, and Giandomenico Solimando. 2024. Evaluating password strength based on information spread on social networks: A combined approach relying on data reconstruction and generative models. Online Soc. Netw. Media 42, 100278 (Aug. 2024), 100278.

- Navid Ayoobi, Sadat Shahriar, and Arjun Mukherjee. 2023. The looming threat of fake and llm-generated linkedin profiles: Challenges and opportunities for detection and prevention. In Proceedings of the 34th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media. 1–10.

- Jackie Ayoub, X Jessie Yang, and Feng Zhou. 2021. Combat COVID-19 infodemic using explainable natural language processing models. Information Processing & Management 58, 4 (2021), 102569.

- Calvin Bao and Marine Carpuat. 2024. Keep It Private: Unsupervised Privatization of Online Text. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.10260 (2024).

- George-Octavian Ba˘rbulescu and Peter Triantafillou. 2024. To Each (Textual Sequence) Its Own: Improving Memorized-Data Unlearning in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML).

- Dipto Barman, Ziyi Guo, and Owen Conlan. 2024. The dark side of language models: Exploring the potential of llms in multimedia disinformation generation and dissemination. Machine Learning with Applications (2024), 100545.

- Simone Bonechi. 2024. Development of an automated moderator for deliberative events. Electronics (Basel) 13, 3 (Jan. 2024), 544.

- Ali Borji and Mehrdad Mohammadian. 2023. Battle of the wordsmiths: Comparing ChatGPT, GPT-4, Claude, and bard. SSRN Electron. J. (2023).

- Robert Brandt. 2023. AI-Assisted Medicine: Possibly Helpful, Possibly Terrifying. Emergency Medicine News 45, 7 (2023), 20. [CrossRef]

- Olivia Brown, Robert M Davison, Stephanie Decker, David A Ellis, James Faulconbridge, Julie Gore, Michelle Greenwood, Gazi Islam, Christina Lubinski, Niall G MacKenzie, et al. 2024. Theory-driven perspectives on generative artificial intelligence in business and management. British Journal of Management 35, 1 (2024), 3–23.

- Yunna Cai, Fan Wang, Haowei Wang, and Qianwen Qian. 2023. Public sentiment analysis and topic modeling regarding ChatGPT in mental health on Reddit: Negative sentiments increase over time. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.15800 (2023).

- Nicholas Carlini, Florian Tramer, Eric Wallace, Matthew Jagielski, Ariel Herbert-Voss, Katherine Lee, Adam Roberts, Tom B. Brown, Dawn Song, Colin Raffel, et al. 2021. Extracting Training Data from Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 30th USENIX Security Symposium. USENIX Association, 2633–2650.

- Rosario Catelli, Hamido Fujita, Giuseppe De Pietro, and Massimo Esposito. 2022. Deceptive reviews and sentiment polarity: Effective link by exploiting BERT. Expert Syst. Appl. 209, 118290 (Dec. 2022), 118290.

- Pew Research Center. 2024. Social Media and News Fact Sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/ fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/.

- Vaishali Chawla and Yatin Kapoor. 2023. A hybrid framework for bot detection on twitter: Fusing digital DNA with BERT. Multimed. Tools Appl. 82, 20 (Aug. 2023), 30831–30854. [CrossRef]

- Ben Chen, Bin Chen, Dehong Gao, Qijin Chen, Chengfu Huo, Xiaonan Meng, Weijun Ren, and Yang Zhou. 2021. Transformer-based language model fine-tuning methods for COVID-19 fake news detection. In Combating online hostile posts in regional languages during emergency situation: First international workshop, CONSTRAINT 2021, collocated with AAAI 2021, virtual event, February 8, 2021, revised selected papers 1. Springer, 83–92.

- Canyu Chen and Kai Shu. 2023. Can LLM-generated misinformation be detected? (2023). 2309.13788 [cs.CL].

- Tsun-Hin Cheung and Kin-Man Lam. 2023. Factllama: Optimizing instruction-following language models with external knowledge for automated fact-checking. In 2023 Asia Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC). IEEE, 846–853.

- Xiaoxiao Chi, Xuyun Zhang, Yan Wang, Lianyong Qi, Amin Beheshti, Xiaolong Xu, Kim-Kwang Raymond Choo, Shuo Wang, and Hongsheng Hu. 2024. Shadow-free membership inference attacks: recommender systems are more vulnerable than you thought. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.07018 (2024).

- Eun Cheol Choi and Emilio Ferrara. 2024. Automated claim matching with large language models: empowering fact-checkers in the fight against misinformation. In Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024. 1441–1449.

- Jeff Christensen, Jared M Hansen, and Paul Wilson. 2024. Understanding the role and impact of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) hallucination within consumers’ tourism decision-making processes. Curr. Issues Tourism (Jan. 2024), 1–16.

- Cloudflare. 2025. What is a social media bot? https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/bots/what-is-a-social- media-bot/ Accessed: March 17, 2025.

- Sean M Coffey, Joseph W Catudal, and Nathaniel D Bastian. 2024. Differential privacy to mathematically secure fine-tuned large language models for linguistic steganography. In Assurance and Security for AI-enabled Systems, Vol. 13054. SPIE, 160–171.

- Henry Collier. 2024. AI: The Future of Social Engineering! Proc. Eur. Conf. Inf. Warf. Secur. 23, 1 (June 2024).

- Alexis Conneau, Guillaume Lample, Marco Ranzato, Lionel Denoyer, and Hervé Jégou. 2020. Unsupervised Cross-lingual Representation Learning at Scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.02116 (2020).

- Nicole A Cooke. 2017. Posttruth, truthiness, and alternative facts: Information behavior and critical information consumption for a new age. The library quarterly 87, 3 (2017), 211–221.

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. (2019), 4171–4186.

- Jane Dickson and Thomas S. McCauley. 2023. The Ethics of AI in Mental Health: Safeguarding Patient Privacy in Online Settings. ACM Transactions on Internet Technology 23, 2 (2023), 1–24.

- Dilara Dogan, Bahadir Altun, Muhammed Said Zengin, Mucahid Kutlu, and Tamer Elsayed. 2023. Catch Me If You Can: Deceiving Stance Detection and Geotagging Models to Protect Privacy of Individuals on Twitter. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Vol. 17. 173–184. [CrossRef]

- Yao Dou, Isadora Krsek, Tarek Naous, Anubha Kabra, Sauvik Das, Alan Ritter, and Wei Xu. 2023. Reducing Privacy Risks in Online Self-Disclosures with Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.09538 (2023).

- Sunny Duan, Mikail Khona, Abhiram Iyer, Rylan Schaeffer, and Ila Rani Fiete. 2025. Uncovering Latent Memories in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

- David Dukic, Dominik Keca, and Dominik Stipic. 2020. Are you human? Detecting bots on twitter using BERT. In 2020 IEEE 7th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA) (sydney, Australia). IEEE.

- Chris Dulhanty, Jason L Deglint, Ibrahim Ben Daya, and Alexander Wong. 2019. Taking a stance on fake news: Towards automatic disinformation assessment via deep bidirectional transformer language models for stance detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.11951 (2019).

- Clay Duncan and Ian Mcculloh. 2023. Unmasking Bias in Chat GPT Responses. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (Kusadasi Turkiye). ACM, New York, NY, USA.

- Mohammed E. Almandouh, Mohammed F Alrahmawy, Mohamed Eisa, Mohamed Elhoseny, and AS Tolba. 2024. Ensemble based high performance deep learning models for fake news detection. Scientific Reports 14, 1 (2024), 26591.

- Mengyi Wang Fangfang Shan, Huifang Sun. 2024. Multimodal Social Media Fake News Detection Based on Similarity Inference and Adversarial Networks. Computers, Materials & Continua 79, 1 (2024), 581–605. 1546-2226.

- Shangbin Feng, Zhaoxuan Tan, Herun Wan, Ningnan Wang, Zilong Chen, Binchi Zhang, Qinghua Zheng, Wenqian Zhang, Zhenyu Lei, Shujie Yang, et al. 2022. TwiBot-22: Towards Graph-Based Twitter Bot Detection. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

- Shangbin Feng, Herun Wan, Ningnan Wang, Zhaoxuan Tan, Minnan Luo, and Yulia Tsvetkov. 2024. What does the bot say? Opportunities and risks of large language models in social media bot detection. (2024). 2402.00371 [cs.CL].

- Chiarello Filippo, Giordano Vito, Spada Irene, Barandoni Simone, and Fantoni Gualtiero. 2024. Future applications of generative large language models: A data-driven case study on ChatGPT. Technovation 133 (2024), 103002.

- Matt Fredrikson, Somesh Jha, and Thomas Ristenpart. 2015. Model Inversion Attacks that Exploit Confidence Information and Basic Countermeasures. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS). ACM, 1322–1333.

- José Antonio García-Díaz and Rafael Valencia-García. 2022. Compilation and evaluation of the Spanish SatiCorpus 2021 for satire identification using linguistic features and transformers. Complex Intell. Syst. 8, 2 (April 2022), 1723–1736.

- Andres Garcia-Silva, Cristian Berrio, and Jose Manuel Gomez-Perez. 2021. Understanding Transformers for Bot Detection in Twitter. (2021). [arxiv]2104.06182.

- Razan Ghanem and Hasan Erbay. 2020. Context-dependent model for spam detection on social networks. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 9 (Sept. 2020).

- Razan Ghanem, Hasan Erbay, and Khaled Bakour. 2023. Contents-based spam detection on social networks using RoBERTa embedding and stacked BLSTM. SN Comput. Sci. 4, 4 (May 2023).

- Masood Ghayoomi. 2023. Enriching contextualized semantic representation with textual information transmission for COVID-19 fake news detection: A study on English and Persian. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 38, 1 (2023), 99–110. [CrossRef]

- Erwin Gielens, Jakub Sowula, and Philip Leifeld. 2025. Goodbye human annotators? Content analysis of social policy debates using ChatGPT. Journal of Social Policy (2025), 1–20.

- Nir Grinberg, Kenneth Joseph, Lisa Friedland, Briony Swire-Thompson, and David Lazer. 2019. Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 US presidential election. Science 363, 6425 (2019), 374–378.

- Tianle Gu, Zeyang Zhou, Kexin Huang, Liang Dandan, Yixu Wang, Haiquan Zhao, Yuanqi Yao, Yujiu Yang, Yan Teng, Yu Qiao, et al. 2024. Mllmguard: A multi-dimensional safety evaluation suite for multimodal large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 37 (2024), 7256–7295.

- Qinglang Guo, Haiyong Xie, Yangyang Li, Wen Ma, and Chao Zhang. 2021. Social bots detection via fusing BERT and graph convolutional networks. Symmetry (Basel) 14, 1 (Dec. 2021), 30.

- Ankur Gupta*, School of Information Technology, RGPV, Bhopal, India., Yogendra P S Maravi, Nishchol Mishra, School of Information Technology, RGPV Bhopal, India., and School of Information Technology, RGPV Bhopal, India. 2019. Twitter Spam Detection using Pre-trained Model. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) 8, 4 (Nov. 2019), 10620–10623.

- Fouzi Harrag, Maria Dabbah, Kareem Darwish, and Ahmed Abdelali. 2020. Bert Transformer Model for Detecting Arabic GPT2 Auto-Generated Tweets. In Proceedings of the Fifth Arabic Natural Language Processing Workshop (WANLP). Association for Computational Linguistics, Barcelona, Spain (Online), 207–214. https://aclanthology.org/2020.wanlp-1.19/.

- Ehtesham Hashmi, Sule Yildirim Yayilgan, Muhammad Mudassar Yamin, Subhan Ali, and Mohamed Abomhara. 2024. Advancing Fake News Detection: Hybrid Deep Learning With FastText and Explainable AI. IEEE Access 12 (2024), 44462–44480.

- Katherine Haynes, Hossein Shirazi, and Indrakshi Ray. 2021. Lightweight URL-based phishing detection using natural language processing transformers for mobile devices. Procedia Comput. Sci. 191 (2021), 127–134.

- Dan Heaton, Jeremie Clos, Elena Nichele, and Joel E Fischer. 2024. “The ChatGPT bot is causing panic now – but it’ll soon be as mundane a tool as Excel”: analysing topics, sentiment and emotions relating to ChatGPT on Twitter. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. (May 2024).

- Maryam Heidari and James H Jones. 2020. Using BERT to extract topic-independent sentiment features for social media bot detection. In 2020 11th IEEE Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON) (New York, NY, USA). IEEE.

- Hanjuan Huang, Hsuan-Ting Peng, and Hsing-Kuo Pao. 2023. Fake News Detection via Sentiment Neutralization. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData). IEEE, 5780–5789.

- Jinyuan Huang, Zhao Song, Keliang Li, Shuang Zhang, Sitao Duan, Bo Li, and Haitao Zhao. 2020. InstaHide: Instance-hiding Schemes for Private Discourse on Public Training. In International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML).

- Kexin Huang, Xiangyang Liu, Qianyu Guo, Tianxiang Sun, Jiawei Sun, Yaru Wang, Zeyang Zhou, Yixu Wang, Yan Teng, Xipeng Qiu, Yingchun Wang, and Dahua Lin. 2024. Flames: Benchmarking Value Alignment of LLMs in Chinese. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, Mexico City, Mexico, 4551–4591.

- Steve Huntsman, Michael Robinson, and Ludmilla Huntsman. 2024. Prospects for inconsistency detection using large language models and sheaves. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.16713 (2024).

- Sungsoon Jang, Yeseul Cho, Hyeonmin Seong, Taejong Kim, and Hosung Woo. 2024. The Development of a Named Entity Recognizer for Detecting Personal Information Using a Korean Pretrained Language Model. Applied Sciences 14, 13 (2024), 5682. [CrossRef]

- Shan Jiang, Miriam Metzger, Andrew Flanagin, and Christo Wilson. 2020. Modeling and measuring expressed (dis) belief in (mis) information. In Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media, Vol. 14. 315–326.

- Weiqiang Jin, Ningwei Wang, Tao Tao, Bohang Shi, Haixia Bi, Biao Zhao, Hao Wu, Haibin Duan, and Guang Yang. 2024. A veracity dissemination consistency-based few-shot fake news detection framework by synergizing adversarial and contrastive self-supervised learning. Scientific Reports 14, 1 (2024), 19470.

- Bianca Montes Jones and Marwan Omar. 2023. Detection of twitter spam with language models: A case study on how to use BERT to protect children from spam on twitter. In 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, & Applied Computing (CSCE) (Las Vegas, NV, USA). IEEE, 511–516.

- Niket Tandon Kandpal, Samuel Bowman, Ethan Perez, and Colin Raffel. 2023. Quantifying Memorization Across Neural Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

- Debanjana Kar, Mohit Bhardwaj, Suranjana Samanta, and Amar Prakash Azad. 2021. No rumours please! a multi-indic-lingual approach for covid fake-tweet detection. (2021), 1–5.

- Kornraphop Kawintiranon, Lisa Singh, and Ceren Budak. 2022. Traditional and context-specific spam detection in low resource settings. Mach. Learn. 111, 7 (July 2022), 2515–2536. [CrossRef]

- Indra Kertati, Carlos Y T Sanchez, Muhammad Basri, Muhammad Najib Husain, and Hery Winoto Tj. 2023. Public relations’ disruption model on chatgpt issue. J. Studi Komun. (Indones. J. Commun. Stud.) 7, 1 (March 2023), 034–048.

- Ashfia Jannat Keya, Md. Anwar Hussen Wadud, M. F. Mridha, Mohammed Alatiyyah, and Md. Abdul Hamid. 2022. AugFake-BERT: Handling Imbalance through Augmentation of Fake News Using BERT to Enhance the Performance of Fake News Classification. Applied Sciences 12, 17 (2022). 2076-3417.

- M Mehdi Kholoosi, M Ali Babar, and Roland Croft. 2024. A Qualitative Study on Using ChatGPT for Software Security: Perception vs. Practicality. (2024), 107–117.

- Myeong Gyu Kim, Minjung Kim, Jae Hyun Kim, and Kyungim Kim. 2022. Fine-tuning BERT models to classify misinformation on garlic and COVID-19 on Twitter. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 9 (April 2022), 5126.

- Siwon Kim, Sangdoo Yun, Hwaran Lee, Martin Gubri, Sungroh Yoon, and Seong Joon Oh. 2024. Propile: Probing privacy leakage in large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2024).

- Sahas Koka, Anthony Vuong, and Anish Kataria. 2024. Evaluating the Efficacy of Large Language Models in Detecting Fake News: A Comparative Analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.06584 (2024).

- Shubham Kumar, Shivang Garg, Yatharth Vats, and Anil Singh Parihar. 2021. Content based bot detec- tion using bot language model and BERT embeddings. In 2021 5th International Conference on Computer, Communication and Signal Processing (ICCCSP) (Chennai, India). IEEE.

- Jianqiao Lai, Xinran Yang, Wenyue Luo, Linjiang Zhou, Langchen Li, Yongqi Wang, and Xiaochuan Shi. 2024. RumorLLM: A Rumor Large Language Model-Based Fake-News-Detection Data-Augmentation Approach. Applied Sciences 14, 8 (2024). 2076-3417.

- David MJ Lazer, Matthew A Baum, Yochai Benkler, Adam J Berinsky, Kelly M Greenhill, Filippo Menczer, Miriam J Metzger, Brendan Nyhan, Gordon Pennycook, David Rothschild, et al. 2018. The science of fake news. Science 359, 6380 (2018), 1094–1096. [CrossRef]

- Jaeyoung Lee, Ximing Lu, Jack Hessel, Faeze Brahman, Youngjae Yu, Yonatan Bisk, Yejin Choi, and Saadia Gabriel. 2024. How to Train Your Fact Verifier: Knowledge Transfer with Multimodal Open Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.00369 (2024).

- Siyu Li, Jin Yang, and Kui Zhao. 2023. Are you in a masquerade? exploring the behavior and impact of large language model driven social bots in online social networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.10337 (2023).

- Wei Li, Jiawen Deng, Jiali You, Yuanyuan He, Yan Zhuang, and Fuji Ren. 2025. ETS-MM: A Multi-Modal Social Bot Detection Model Based on Enhanced Textual Semantic Representation. In Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025. 4160–4170.

- Xuechen Li, Florian Tramer, Percy Liang, and Tatsunori Hashimoto. 2022. Large Language Models Can Be Strong Differentially Private Learners. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

- Xinyi Li, Yongfeng Zhang, and Edward C Malthouse. 2024. Large Language Model Agent for Fake News Detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.01593 (2024).

- Yufan Li, Zhan Wang, and Theo Papatheodorou. 2024. Staying vigilant in the Age of AI: From content generation to content authentication. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.00922 (2024).

- Ying Lian, Huiting Tang, Mengting Xiang, and Xuefan Dong. 2024. Public attitudes and sentiments toward ChatGPT in China: A text mining analysis based on social media. Technol. Soc. 76, 102442 (March 2024), 102442.

- Luyang Lin, Lingzhi Wang, Jinsong Guo, and Kam-Fai Wong. 2024. Investigating bias in llm-based bias detection: Disparities between llms and human perception. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.14896 (2024).

- Xiaohan Liu, Yue Zhan, Hao Jin, Yuan Wang, and Yi Zhang. 2023. Research on the classification methods of social bots. Electronics (Basel) 12, 14 (July 2023), 3030. [CrossRef]

- Yuhan Liu, Xiuying Chen, Xiaoqing Zhang, Xing Gao, Ji Zhang, and Rui Yan. 2024. From Skepticism to Acceptance: Simulating the Attitude Dynamics Toward Fake News. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Third Interna- tional Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-24, Kate Larson (Ed.). International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 7886–7894. Human-Centred AI.

- Yifan Liu, Yaokun Liu, Zelin Li, Ruichen Yao, Yang Zhang, and Dong Wang. 2025. Modality interactive mixture-of-experts for fake news detection. In Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025. 5139–5150.

- Yinhan Liu, Myle Ott, Naman Goyal, Jingfei Du, Mandar Joshi, Danqi Chen, Omer Levy, Mike Lewis, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Veselin Stoyanov. 2019. RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.11692 (2019). https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.11692.

- Ye Liu, Jiajun Zhu, Kai Zhang, Haoyu Tang, Yanghai Zhang, Xukai Liu, Qi Liu, and Enhong Chen. 2024. Detect, Investigate, Judge and Determine: A Novel LLM-based Framework for Few-shot Fake News Detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.08952 (2024).

- Scott M. Lundberg and Su-In Lee. 2017. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Vol. 30. 4765–4774.

- Hanjia Lyu, Jinfa Huang, Daoan Zhang, Yongsheng Yu, Xinyi Mou, Jinsheng Pan, Zhengyuan Yang, Zhongyu Wei, and Jiebo Luo. 2023. Gpt-4v (ision) as a social media analysis engine. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.07547 (2023).

- SreeJagadeesh Malla and PJA Alphonse. 2022. Fake or real news about COVID-19? Pretrained transformer model to detect potential misleading news. The European Physical Journal Special Topics 231, 18 (2022), 3347–3356.

- J. Martin, P. Johnson, and D. Chang. 2022. AI and Mental Health: Privacy Challenges and Solutions. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 9, 3 (2022), 180–192.

- Justus Mattern, Benjamin Weggenmann, and Florian Kerschbaum. 2022. The limits of word level differential privacy. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.02130 (2022).

- Nikhil Mehta and Dan Goldwasser. 2024. Using RL to identify divisive perspectives improves LLMs abilities to identify communities on social media. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.00969 (2024).

- Meta Platforms, Inc. 2023. Facebook Privacy Policy. Available at https://www.facebook.com/privacy/ policy, accessed March 2024.

- Zhongtao Miao, Qiyu Wu, Kaiyan Zhao, Zilong Wu, and Yoshimasa Tsuruoka. 2024. Enhancing cross-lingual sentence embedding for low-resource languages with word alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.02490 (2024).

- Maria Milkova, Maksim Rudnev, and Lidia Okolskaya. 2023. Detecting value-expressive text posts in Russian social media. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.08968 (2023).

- Helen Milner and Michael Baron. 2023. Establishing an optimal online phishing detection method: Evaluating topological NLP transformers on text message data. Journal of Data Science and Intelligent Systems 2, 1 (July 2023), 37–45.

- Fatemehsadat Mireshghallah, Kartik Goyal, Archit Uniyal, Taylor Berg-Kirkpatrick, and Reza Shokri. 2022. Quantifying privacy risks of masked language models using membership inference attacks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.03929 (2022).

- Niloofar Mireshghallah, Hyunwoo Kim, Xuhui Zhou, Yulia Tsvetkov, Maarten Sap, Reza Shokri, and Yejin Choi. 2023. Can llms keep a secret? testing privacy implications of language models via contextual integrity theory. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.17884 (2023).

- Yichuan Mo, Yuji Wang, Zeming Wei, and Yisen Wang. 2024. Fight back against jailbreaking via prompt adversarial tuning. In The Thirty-eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems.

- Robert T. Morris, Florian Tramer, and Nicholas Carlini. 2024. Language Model Inversion: Recovering Training Data from Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

- Qiong Nan, Qiang Sheng, Juan Cao, Beizhe Hu, Danding Wang, and Jintao Li. 2024. Let silence speak: Enhancing fake news detection with generated comments from large language models. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management. 1732–1742.

- Helen Nissenbaum. 2019. Contextual Integrity Up and Down the Data Food Chain. Theoretical Inquiries in Law 20, 1 (2019), 221–256. [CrossRef]

- Nikolaos Panagiotou, Antonia Saravanou, and Dimitrios Gunopulos. 2021. News Monitor: A framework for exploring news in real-time. Data (Basel) 7, 1 (Dec. 2021), 3.

- Subhadarshi Panda and Sarah Ita Levitan. 2021. Detecting multilingual COVID-19 misinformation on social media via contextualized embeddings. In Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on NLP for Internet Freedom: Censorship, Disinformation, and Propaganda (Online). Association for Computational Linguistics, Stroudsburg, PA, USA.

- Constantinos Patsakis and Nikolaos Lykousas. 2023. Man vs the machine in the struggle for effective text anonymisation in the age of large language models. Scientific Reports 13, 1 (2023), 16026.

- Protik Bose Pranto, Syed Zami-Ul-Haque Navid, Protik Dey, Gias Uddin, and Anindya Iqbal. 2022. Are you misinformed? a study of covid-related fake news in bengali on facebook. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.11669 (2022).

- Jason Priem, Heather Piwowar, and Richard Orr. 2022. OpenAlex: A fully-open index of scholarly works, authors, venues, institutions, and concepts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.01833 (2022).

- Haritz Puerto, Martin Gubri, Sangdoo Yun, and Seong Joon Oh. 2024. Scaling Up Membership Inference: When and How Attacks Succeed on Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.00154 (2024).

- Sai Puppala, Ismail Hossain, Md Jahangir Alam, and Sajedul Talukder. 2024. FLASH: Federated Learning- Based LLMs for Advanced Query Processing in Social Networks through RAG. (2024), 281–293.

- Sai Puppala, Ismail Hossain, Md Jahangir Alam, and Sajedul Talukder. 2024. SocFedGPT: Federated GPT-based Adaptive Content Filtering System Leveraging User Interactions in Social Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.05243 (2024).

- Shengsheng Qian, Jinguang Wang, Jun Hu, Quan Fang, and Changsheng Xu. 2021. Hierarchical Multi- modal Contextual Attention Network for Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (Virtual Event, Canada) (SIGIR ’21). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 153–162. 9781450380379.

- Kristina Radivojevic, Nicholas Clark, and Paul Brenner. 2024. LLMs Among Us: Generative AI participating in digital discourse. Proceedings of the AAAI Symposium Series 3, 1 (May 2024), 209–218.

- Sarika S Raga and Chaitra B. 2022. A bert model for sms and twitter spam ham classification and comparative study of machine learning and deep learning technique. In 2022 IEEE 7th International Conference on Recent Advances and Innovations in Engineering (ICRAIE) (MANGALORE, India). IEEE.

- David Ramamonjisoa and Shuma Suzuki. 2024. Comments Analysis in Social Media based on LLM Agents. In CS & IT Conference Proceedings, Vol. 14.

- Junaid Rashid, Jungeun Kim, and Anum Masood. 2024. Unraveling the Tangle of Disinformation: A Multimodal Approach for Fake News Identification on Social Media. In Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024 (Singapore, Singapore) (WWW ’24). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1849–1853. 9798400701726.

- V Rathinapriya and J Kalaivani. 2024. Adaptive weighted feature fusion for multiscale atrous convolution- based 1DCNN with dilated LSTM-aided fake news detection using regional language text information. Expert Systems (2024), e13665. [CrossRef]

- Prismahardi Aji Riyantoko, Tresna Maulana Fahrudin, Dwi Arman Prasetya, Trimono Trimono, and Tahta Dari Timur. 2022. Analisis Sentimen Sederhana Menggunakan Algoritma LSTM dan BERT un- tuk Klasifikasi Data Spam dan Non-Spam. PROSIDING SEMINAR NASIONAL SAINS DATA 2, 1 (Dec. 2022), 103–111.

- Daniel Russo, Serra Sinem Tekirog˘ lu, and Marco Guerini. 2023. Benchmarking the Generation of Fact Checking Explanations. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 11 (2023), 1250–1264.

- Marko Sahan, Vaclav Smidl, and Radek Marik. 2021. Active Learning for Text Classification and Fake News Detection. In 2021 International Symposium on Computer Science and Intelligent Controls (ISCSIC). 87–94.

- Siva Sai. 2020. Siva at WNUT-2020 task 2: Fine-tuning transformer neural networks for identification of informative covid-19 tweets. In Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop on Noisy User-generated Text (W-NUT 2020) (Online). Association for Computational Linguistics, Stroudsburg, PA, USA.

- Amine Sallah, El Arbi Abdellaoui Alaoui, Said Agoujil, Mudasir Ahmad Wani, Mohamed Hammad, Yassine Maleh, and Ahmed A Abd El-Latif. 2024. Fine-tuned understanding: Enhancing social bot detection with transformer-based classification. IEEE Access 12 (2024), 118250–118269.

- Kanti Singh Sangher, Archana Singh, and Hari Mohan Pandey. 2024. LSTM and BERT based transformers models for cyber threat intelligence for intent identification of social media platforms exploitation from darknet forums. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 16, 8 (Dec. 2024), 5277–5292.

- Victor Sanh, Lysandre Debut, Julien Chaumond, and Thomas Wolf. 2019. DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.01108 (2019).

- Ali Satvaty, Suzan Verberne, and Fatih Turkmen. 2024. Undesirable Memorization in Large Language Models: A Survey. In arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.02650.

- Isabel Segura-Bedmar and Santiago Alonso-Bartolome. 2022. Multimodal fake news detection. Information 13, 6 (2022), 284.

- Samaneh Shafee, Alysson Bessani, and Pedro M Ferreira. 2025. Evaluation of LLM-based chatbots for OSINT-based Cyber Threat Awareness. Expert Systems with Applications 261 (2025), 125509.

- Siddhant Bikram Shah, Surendrabikram Thapa, Ashish Acharya, Kritesh Rauniyar, Sweta Poudel, Sandesh Jain, Anum Masood, and Usman Naseem. 2024. Navigating the web of disinformation and misinformation: Large language models as double-edged swords. IEEE Access (2024), 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Filipo Sharevski, Jennifer Vander Loop, Peter Jachim, Amy Devine, and Emma Pieroni. 2023. Talking abortion (mis) information with chatgpt on tiktok. In 2023 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW). IEEE, 594–608.

- Utkarsh Sharma, Prateek Pandey, and Shishir Kumar. 2022. A transformer-based model for evaluation of information relevance in online social-media: A case study of Covid-19 media posts. New Gener. Comput. 40, 4 (Jan. 2022), 1029–1052. [CrossRef]

- Kai Shu, Suhang Wang, Dongwon Lee, and Huan Liu. 2020. Mining disinformation and fake news: Concepts, methods, and recent advancements. Disinformation, misinformation, and fake news in social media: Emerging research challenges and opportunities (2020), 1–19.

- Utsav Shukla, Manan Vyas, and Shailendra Tiwari. 2023. Raphael at ArAIEval shared task: Understanding persuasive language and tone, an LLM approach. In Proceedings of ArabicNLP 2023 (Singapore (Hybrid)). Association for Computational Linguistics, Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 589–593.

- Nathalie A Smuha. 2025. Regulation 2024/1689 of the Eur. Parl. & Council of June 13, 2024 (EU Artificial Intelligence Act). International Legal Materials (2025), 1–148.

- Giovanni Spitale, Nikola Biller-Andorno, and Federico Germani. 2023. AI model GPT-3 (dis) informs us better than humans. Science Advances 9, 26 (2023), eadh1850.

- Robin Staab, Mark Vero, Mislav Balunovic´, and Martin Vechev. 2023. Beyond memorization: Violating privacy via inference with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.07298 (2023).

- Andrei Stipiuc. 2024. Romanian Media Landscape in 7 Journalists’ Facebook Posts: A ChatGPT Sentiment Analysis. SAECULUM 57, 1 (2024), 20–46.

- Ningxin Su, Chenghao Hu, Baochun Li, and Bo Li. 2024. TITANIC: Towards Production Federated Learning with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of IEEE INFOCOM.

- B N1 Supriya and CB Akki. 2022. P-BERT: Polished Up Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers for Predicting Malicious URL to Preserve Privacy. In 2022 IEEE 9th Uttar Pradesh Section International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (UPCON). IEEE, 1–6.

- Yingjie Tian and Yuhao Xie. 2024. Artificial cheerleading in IEO: Marketing campaign or pump and dump scheme. Inf. Process. Manag. 61, 1 (Jan. 2024), 103537.

- Ahmed Tlili, Boulus Shehata, Michael Agyemang Adarkwah, Aras Bozkurt, Daniel T Hickey, Ronghuai Huang, and Brighter Agyemang. 2023. What if the devil is my guardian angel: ChatGPT as a case study of using chatbots in education. Smart Learn. Environ. 10, 1 (Feb. 2023). [CrossRef]

- Christopher K Tokita, Kevin Aslett, William P Godel, Zeve Sanderson, Joshua A Tucker, Jonathan Nagler, Nathaniel Persily, and Richard Bonneau. 2024. Measuring receptivity to misinformation at scale on a social media platform. PNAS nexus 3, 10 (2024), pgae396. [CrossRef]

- Ben Treves, Md Rayhanul Masud, and Michalis Faloutsos. 2023. RURLMAN: Matching Forum Users Across Platforms Using Their Posted URLs. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining. 484–491.

- Milena Tsvetkova, Taha Yasseri, Niccolo Pescetelli, and Tobias Werner. 2024. A new sociology of humans and machines. Nature Human Behaviour 8, 10 (Oct. 2024), 1864–1876. 2397-3374. [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. 2021. Using Social Media in Community-Based Protection. Retrieved January, 2021 from https://www.unhcr.org/innovation/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Using-Social-Media-in-CBP.pdf.

- Soroush Vosoughi, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral. 2018. The spread of true and false news online. science 359, 6380 (2018), 1146–1151.

- Nazmi Ekin Vural and Sefer Kalaman. 2024. Using Artificial Intelligence Systems in News Verification: An Application on X. I˙letis¸im Kuram ve Aras¸tırma Dergisi 67 (2024), 127–141.

- Xiao Wang, Jinyuan Sun, Jinyuan Zhang, Neil Shah, and Bo Li. 2024. Prompt Inversion: Leveraging Attention-Based Inversion to Recover Prompts from Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

- Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan. 2017. Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policymaking. Vol. 27. Council of Europe Strasbourg.

- Sam Wiseman, Stuart M. Shieber, and Alexander M. Rush. 2018. Learning Neural Templates for Text Generation. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). Association for Computational Linguistics, 3174–3187.

- Yunfei Xing, Justin Zuopeng Zhang, Guangqing Teng, and Xiaotang Zhou. 2024. Voices in the digital storm: Unraveling online polarization with ChatGPT. Technology in Society 77 (2024), 102534. 0160-791X.

- Guangxia Xu, Daiqi Zhou, and Jun Liu. 2021. Social network spam detection based on ALBERT and combination of Bi-LSTM with self-attention. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2021 (April 2021), 1–11.

- Junhao Xu, Longdi Xian, Zening Liu, Mingliang Chen, Qiuyang Yin, and Fenghua Song. 2024. The future of combating rumors? retrieval, discrimination, and generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.20204 (2024).

- Keyang Xuan, Li Yi, Fan Yang, Ruochen Wu, Yi R Fung, and Heng Ji. 2024. LEMMA: towards LVLM- enhanced multimodal misinformation detection with external knowledge augmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.11943 (2024).

- Hongwei Yan, Liyuan Wang, Kaisheng Ma, and Yi Zhong. 2024. Orchestrate latent expertise: Advancing online continual learning with multi-level supervision and reverse self-distillation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 23670–23680.

- Chang Yang, Peng Zhang, Wenbo Qiao, Hui Gao, and Jiaming Zhao. 2023. Rumor detection on social media with crowd intelligence and ChatGPT-assisted networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. 5705–5717.

- Kaicheng Yang and Filippo Menczer. 2024. Anatomy of an AI-powered malicious social botnet. J. Quant. Descr. Digit. Media 4 (May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Yingguang Yang, Renyu Yang, Hao Peng, Yangyang Li, Tong Li, Yong Liao, and Pengyuan Zhou. 2023. FedACK: Federated adversarial contrastive knowledge distillation for cross-lingual and cross-model social bot detection. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023. 1314–1323.

- Xin Yao, Tianchi Huang, Chenglei Wu, Rui-Xiao Zhang, and Lifeng Sun. 2019. Federated learning with additional mechanisms on clients to reduce communication costs. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.05891 (2019).

- Yuhang Yao, Jianyi Zhang, Junda Wu, Chengkai Huang, Yu Xia, Tong Yu, Ruiyi Zhang, Sungchul Kim, Ryan Rossi, Ang Li, et al. 2024. Federated large language models: Current progress and future directions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.15723 (2024).

- Junshuai Yu, Qi Huang, Xiaofei Zhou, and Ying Sha. 2020. IARNet: An Information Aggregating and Reasoning Network over Heterogeneous Graph for Fake News Detection. In 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). 1–9.

- Zhenrui Yue, Huimin Zeng, Yang Zhang, Lanyu Shang, and Dong Wang. 2023. MetaAdapt: Domain adaptive few-shot misinformation detection via meta learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.12692 (2023).

- Hanna Yukhymenko, Robin Staab, Mark Vero, and Martin Vechev. 2024. A Synthetic Dataset for Personal Attribute Inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.07217 (2024).

- Sajjad Zarifzadeh, Philippe Liu, and Reza Shokri. 2023. Low-cost high-power membership inference attacks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.03262 (2023).

- Jinyuan Zhang, Xinyue Chen, Xuechen Li, and Cho-Jui Hsieh. 2024. Membership Inference Attacks against Fine-tuned Large Language Models via Self-prompt Calibration. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS).

- Tong Zhang, Di Wang, Huanhuan Chen, Zhiwei Zeng, Wei Guo, Chunyan Miao, and Lizhen Cui. 2020. BDANN: BERT-Based Domain Adaptation Neural Network for Multi-Modal Fake News Detection. In 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). 1–8.

- Xiang Zhang, Yufei Cui, Chenchen Fu, Zihao Wang, Yuyang Sun, Xue Liu, and Weiwei Wu. 2025. Transtream- ing: Adaptive Delay-aware Transformer for Real-time Streaming Perception. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 39. 10185–10193. [CrossRef]

- Yiming Zhang, Sravani Nanduri, Liwei Jiang, Tongshuang Wu, and Maarten Sap. 2023. Biasx:" thinking slow" in toxic content moderation with explanations of implied social biases. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.13589 (2023).

- Yizhou Zhang, Karishma Sharma, Lun Du, and Yan Liu. 2024. Toward mitigating misinformation and social media manipulation in LLM era. In Companion Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2024 (Singapore Singapore), Vol. 19. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 1302–1305.

- Chenye Zhao and Cornelia Caragea. 2021. Knowledge distillation with BERT for image tag-based privacy prediction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing (RANLP 2021). 1616–1625.

- Xinyi Zhou, Ashish Sharma, Amy X Zhang, and Tim Althoff. 2024. Correcting misinformation on social media with a large language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.11169 (2024).

- Xinyi Zhou and Reza Zafarani. 2020. A survey of fake news: Fundamental theories, detection methods, and opportunities. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 53, 5 (2020), 1–40.

| Info-disorder Cases | Description | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unintentional Generation | Unintentional generation, known as hallucinations, occurs naturally through their generation properties. | [31,139] | |

| Intentional Generation | The deliberate misuse of LLMs to create disinformation. | [16,124] | |

| Techniques | Methods | Description | References |

| Zero-shot Detection | ChatGPTLLaMA | The ability to detect both human-written and LLM-generated misinformation. | [27] |

| Fine-tuned Detection | FACT-GPTFactLLaMA | Fine-tuned LLMs to enhance fact-checking to complement human expertise. | [28,30,86] |

| Knowledge-based Detection | LEMMA | Introducing external knowledge to the detection algorithm. | [86,164,166] |

| Techniques | Methods | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Distillation |

Privacy-aware model compression and transfer |

Minimize sensitive data exposure during training |

[49,180] |

| Differential Privacy |

DP-SGD and privacy- preserving optimization |

Formal privacy guarantees for model training |

[67,89] |

| Federated Learning |

Decentralized model updates and training |

Privacy-preserving distributed learning |

[148,169] |

| Adversarial Protection |

Text perturbation and obfuscation techniques |

Prevent unauthorized inference and linking |

[39,149] |

| Privacy-Preserving Attention |

Modified attention mechanisms for privacy |

Secure information processing in LLMs |

[22,117] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).