1. Introduction

The first hours and days following a disaster — whether an earthquake, flooding or another natural or man-made disaster — are critical for saving lives. This initial phase is characterized by chaos, destruction and compromised infrastructure, creating extreme risk conditions that significantly hinder the rapid deployment of search and rescue teams [

1]. Reduced visibility, inaccessible terrain [

2] and, most importantly, a lack of accurate information about the extent of the damage and the location of victims, pose major obstacles to rescue operations. A prerequisite for crisis management is that critical decisions are largely based on the availability, accuracy and timeliness of information provided to decision-makers [

3]. In these emergency situations, a fast response and the ability to obtain a reliable overview are crucial for maximizing the chances of survival for those who are trapped or missing.

In addition to physical obstacles, the deployment of human resources across multiple locations presents a logistical challenge that is often impossible to overcome [

4], and the success of operations depends critically on the ability to overcome these logistical barriers [

5]. In this context, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have emerged as an indispensable tool for conducting search and rescue missions in the early stages of disasters. Recent simulations have demonstrated the potential of drones, with over 90% of survivors located in less than 40 minutes in disaster scenarios [

6]. Other studies have demonstrated similar success rates through multi-UAV collaboration [

7], further enhancing the efficiency of these systems.

Although unmanned vehicles have transformed the way data is collected in disaster areas by generating impressive volumes of real-time video and sensory information, this abundance of data presents its own challenges. Human operators are still overwhelmed by the task of constantly monitoring video streams and identifying critical information, such as immediate risks. This information overload is a well-known issue that can lead to high cognitive load, causing operators to overlook relevant information [

8,

9]. Although existing computer vision systems, such as those based on YOLO (You Only Look Once) [

10], can detect people, they often provide information that is isolated and lacks semantic context or state assessment. The major challenge is that detecting an object (a person) is insufficient. Future systems must enable a semantic understanding of the situation to support decision-making processes [

11]. The current reliance on raw information places a significant cognitive burden on rescue teams, consuming time and increasing the risk of errors in decision-making. Therefore, there is a need to move beyond simple data collection towards contextual understanding and intelligent analysis, which could significantly ease the work of intervention teams [

12].

To overcome these limitations and capitalize on the convergence of these fields, we propose a cognitive-agentic architecture that will transform drones from simple observation tools into intelligent, proactive partners in search and rescue operations. Our work's key contribution lies in its modular agentic approach, where specialized software agents manage perception, memory, reasoning and action separately. At the heart of this architecture is the integration of a large language model (LLM) acting as an orchestrator agent — a feature that enables the system to perform logical validation and self-correction via feedback loops. To enable this reasoning, we have developed an advanced visual perception module based on YOLO11, which has been trained on a composite dataset. This module can perform detailed semantic classification of victims' status, going beyond simple detection. This approach is necessary because accurately assessing disaster scenarios requires the semantic interpretation of aerial images, beyond simple detection [

13]. Finally, we present a fully integrated cycle of perception, reasoning and action by incorporating a physical module for the delivery of first aid kits, thereby closing the loop from analysis to direct intervention. Using drones to rapidly deliver first aid supplies to disaster-stricken areas where access is difficult can have a significant impact on survival rates [

14]. This integrated system's main objective is to drastically reduce the cognitive load on human operators and accelerate the process of locating and assisting victims by providing clear, contextualized, actionable information. This system can adapt to different fields, providing a deeper understanding of the environment in any use it is build (e.g., agriculture, topology, forestry etc.) [

15].

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents an analysis of relevant works in the field of UAVs for disaster response and AI-based SAR systems.

Section 3 details the architecture and key components of the proposed cognitive approach, including the data-collecting hardware.

Section 4 describes the implementation of the person detection module, including data acquisition, model training, and performance evaluation.

Section 5 presents the algorithms used to map detected persons and assign them GPS coordinates to facilitate rescue.

Section 6 describes every component of the cognitive-agentic architecture system.

Section 7 presents the results of the feedback loop of cognitive architecture. Finally,

Section 8 concludes the paper and presents future research directions.

2. Related Works

The field of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) use in SAR operations has evolved rapidly, progressing from basic remote sensing platforms to increasingly autonomous systems. To contextualize our contribution, we analyze the literature from three complementary perspectives: specialized UAV systems for SAR sub-tasks; cognitive architectures for situational awareness; and, most importantly, the emerging paradigm of agentic robotic systems based on large language models (LLMs).

This paper [

16] proposes an innovative method of locating victims in disaster areas by detecting mobile phones that have run out of battery power. The system uses a UAV equipped with wireless power transfer technology to temporarily activate these devices and enable them to emit a signal. The drone then uses traversal graph and clustering algorithms to optimize its search path and locate the signal sources, thereby improving the efficiency of search operations in scenarios where visual methods are ineffective.

The issue of how to plan drone routes for search and rescue missions is dealt with in article [

17]. The authors propose a genetic algorithm-based algorithm that aims to minimize total mission time while simultaneously considering two objectives: achieving complete coverage of the search area and maintaining stable communication with ground personnel. The innovation lies in evaluating flexible communication strategies (e.g. 'data mule', relay chains), which allow the system to dynamically adjust the priority between searching and communicating. Through simulations, the authors demonstrate a significant reduction in mission time.

In [

18], the authors focus on the direct interaction between the victim and the rescue drone. The proposed system uses a YOLOv3-Tiny model to detect human presence in real time. Once a person has been detected, the system enters a phase of recognizing gestures, thus enabling effective non-verbal communication. The authors created a new dataset comprising rescue gestures (both body and hand), which enables the drone to initiate or cancel interaction and overcome the limitations of voice communication in noisy or distant environments.

Article [

19] proposes a proactive surveillance system that uses UAVs. This system is designed to overcome the limitations of teleoperated systems by exhibiting human-like behavior. The main innovation lies in the use of two key components: Semantic Web technologies for the high-level description of objects and scenarios and a Fuzzy Cognitive Map (FCM) model to provide cognitive capabilities for the accumulation of spatial knowledge and the discernment of critical situations. The system integrates data to develop situational awareness, enabling the drone to understand evolving scenes and make informed decisions rather than relying solely on simple detection.

The reviewed literature highlights a clear trend toward specialized systems that solve critical sub-problems in SAR missions, from optimizing flight paths to enabling non-verbal communication or enhancing situational awareness through cognitive models like FCMs. However, a significant challenge remains: the integration of these functionalities into a cohesive system that actively reduces the cognitive burden on human operators by autonomously interpreting complex scenarios.

Our fundamental contribution addresses this integration challenge through a novel cognitive-agentic architecture. Unlike traditional approaches, our system is orchestrated by a LLM, which acts as the central reasoning core. This design choice introduces a crucial capability absent in prior models: robust self-correction through feedback loops, allowing the system to validate its own conclusion and rectify inconsistencies before presenting them to the operator. To fuel this reasoning process, we developed an advanced visual perception module based on a custom-trained YOLO11 model, which provides the necessary semantic context about a victim's condition (e.g., immobile, partially, occluded). Furthermore, by incorporating a physical module for first-aid delivery, our system demonstrates a fully closed perception - reasoning- action loop in this context. This transforms the drone from passive data-gathering tool into a proactive and intelligent partner, designed specially to convert raw data into actionable intelligence, thereby accelerating the decision-making process and the delivery of aid to victims.

3. Materials and Methods Used for the Proposed System

This section outlines the key components and methodological approaches of the intelligent system. The aim is to demonstrate how these components contribute to the system's overall functionality and efficiency, enabling autonomous operation in complex disaster response scenarios.

The choice of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) platform is critical to the development of autonomous search and rescue systems, directly influencing their performance, cost and scalability. For this study, we chose a customized multi-motor drone that balances research and development requirements with operational capabilities.

Table 1 compares the technical parameters of the proposed UAV platform with those of two representative commercial systems: The DJI Matrice 300 RTK, which is a multi-engine platform used in professional applications, while the other is a budget drone meant for amateur activities.

We chose a custom-built model because while others might offer more performance at a lower cost, our model was more versatile in the development stage and even in repairs, while the commercial solutions are tied to their own branding of spare parts, our choice can be changed very easily to new parts.

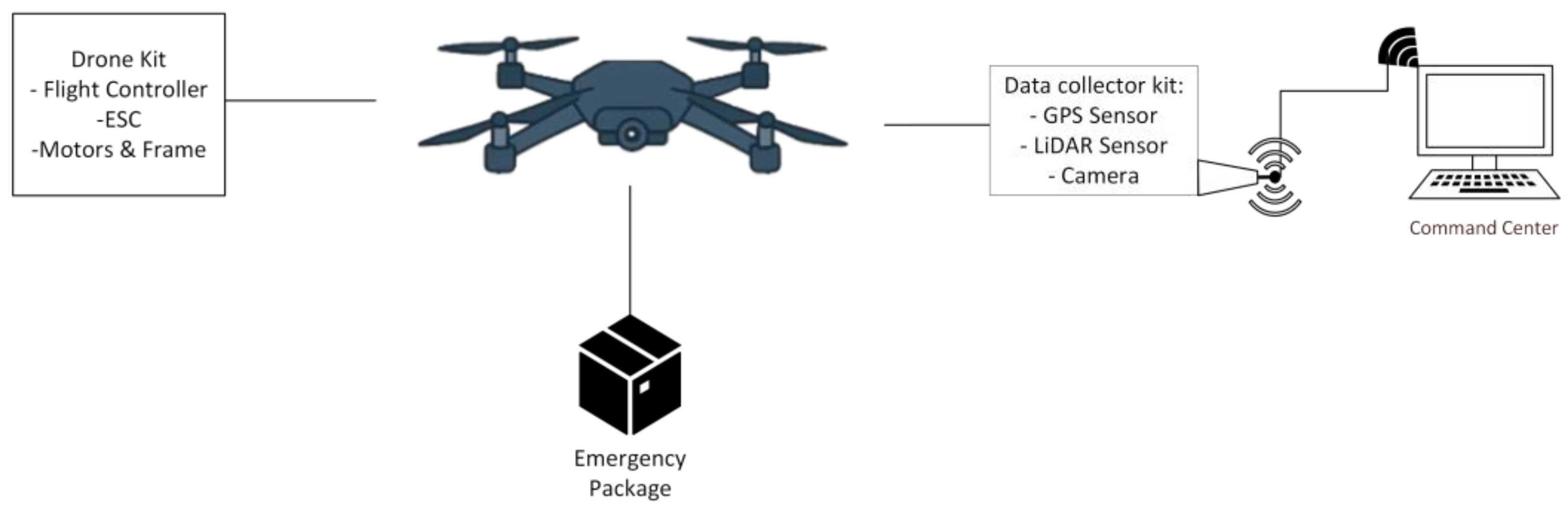

To improve understanding of the system,

Figure 1 illustrates the drone system architecture, showing how the modules (e.g., sensors, communication units, and control elements) interact. This modular design allows for the integration of functionalities such as navigation, data acquisition and victim detection, facilitating real-time processing and coordination.

The system operates via a continuous, integrated flow of data. It collects information from sensors and video streams via the ESP32S3 MPU, which is installed on board the drone. This data is then transmitted in real time to the ground command center via a secure connection using the 802.11 b/g/n standard (2.4 GHz Wi-Fi for the prototype phase).

Once received, the ground device directs the video stream to the YOLO11 module for preliminary identification of individuals. Both the processed and original video streams, along with the sensor data, are stored and transmitted to the command center for in-depth analysis and the generation of concrete recommendations.

The frequency at which our system acquires data is strategically configured to strike a balance between informational relevance and resource efficiency. Primary GPS location data is updated at a rate of 1 Hz. To improve the accuracy of distance measurements, values from the LiDAR sensor are acquired at 2 Hz. This enables two LiDAR readings to be taken for each GPS update, facilitating the calculation of a median value which contributes to noise filtering and providing more robust data for environmental assessment.

The system primarily uses standard commercial components. This approach was adopted to enable rapid development, facilitating concept validation and algorithm refinement in a controlled environment. While these components are not particularly robust, they are adequate for the prototyping phase. For operational deployment in the field, however, it is anticipated that a transition to professional-grade hardware specialized for hostile environments will be necessary.

The following sections will provide an overview of the platform's capabilities by describing the main hardware and software elements, from data acquisition and processing to the analysis core.

3.1. Flight Module

The flight module is the actual aerial platform. It was built and assembled from scratch using an F450 frame and an FPV drone kit. This approach enabled detailed control over component selection and assembly, resulting in a modular, adaptable structure. The proposed drone is a multi-motor quadcopter, chosen for its stability during hovering flight and its ability to operate in confined spaces.

Figure 2 shows the physical assembly of the platform, which forms the basis for the subsequent integration of the sensor and delivery modules.

The drone is equipped with 920KV motors and is powered by a 3650mAh LiPo battery, ensuring a balance of power and efficiency. This hardware configuration gives the drone an estimated payload capacity of 500 g–1 kg. Based on this configuration, the estimated flight time is 20-22 minutes under optimal conditions. This operational envelope, while limited, was deemed sufficient for the primary goal of this research stage: to conduct short-duration, controlled field tests aimed at validating the data flow and the real-time performance of the cognitive-agentic architecture. However, this can be directly influenced by the payload carried (especially the 300–700 g delivery package) and the flight style. These parameters are ideal for the small-scale laboratory and field tests required to validate cognitive architecture.

The drone is controlled via a radio controller and receiver to ensure a reliable command link. Under optimal conditions with minimal interference, the estimated range of the control system is 500 to 1,500 meters. The flight control board includes an STM32F405 microcontroller (MCU), a 3-axis ICM42688P gyroscope for precise stabilization, an integrated barometer for maintaining altitude and an AT7456E OSD chip for displaying essential flight data on the video stream. The motors are driven by a 55A speed controller (ESC). The flight controller supports power inputs from 3S to 6S LiPo. Additionally, it features an integrated ESP32 module through which we can configure various drone parameters via Bluetooth, enabling us to adjust settings at the last moment before a mission.

An important feature of the module is that the flight controller is equipped with a memory card slot. This allows continuous recording of all drone data, functioning similarly to an aircraft's 'black box'. Vital flight and system status information is saved locally and can be retrieved for analysis and for troubleshooting purposes.

3.2. Data Acquisition Module

The data acquisition module is designed as an independent, modular unit that acts as the drone's sensory nervous system, collecting multi-modal information from the surrounding environment. It acts as a bridge between the physical world and cognitive architecture, playing a critical role in providing the necessary raw data (visual, positioning and proximity) for ground agents to build an overall picture of the situation.

The data acquisition module is designed to operate as a stand-alone unit, integrating multiple sensors:

Main MPU: It features a 32-bit, dual-core Tensilica Xtensa LX7 processor that operates at speeds of up to 240 MHz. It is also equipped with 8 MB of PSRAM and 8 MB of Flash memory, which provides ample storage for processing sensor data and managing video streams.

Camera: Although the ESP32S3 MPU is equipped with an OV2640 camera sensor, a superior OV5640 camera module has been added to enhance image quality and transmission speed. This enables higher-resolution capture and faster access times, providing the analysis module with higher-quality visual data at a cost-effective price.

Distance sensor (LIDAR): A TOF LIDAR laser distance sensor (VL53LDK) is used. It is important to note that this sensor has a maximum measurement range of 2 meters, with an accuracy of ±3%. The sensor has a maximum measurement range of up to 2 meters and an accuracy of ±3%. Although this sensor is not designed for large-scale mapping, it enables proximity awareness and estimation of the terrain profile immediately below the drone. This data is essential for low-altitude flight and for the victim location estimation algorithm.

GPS module: A GY-NEO6MV2 module is integrated to provide positioning data with a horizontal accuracy of 2.5 meters (circular error probable) and an update rate of 1 Hz.

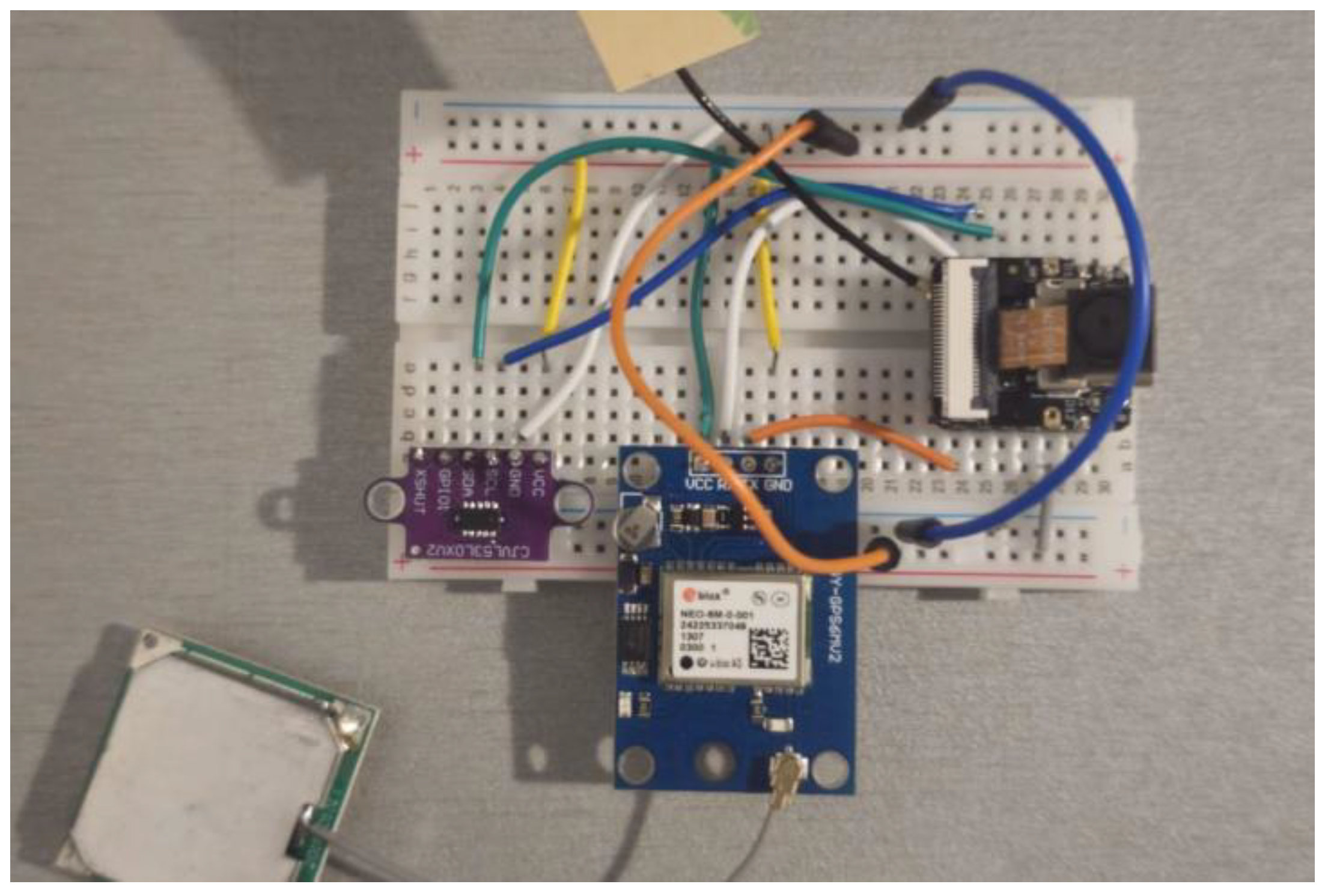

Integrating these components into a compact and efficient package is essential for the module's functionality.

Figure 3 shows how the acquisition system's hardware is assembled, highlighting that the ESP32S3 MPU serves as the central processing unit to which the camera, LiDAR sensor and GPS module are directly connected. This minimalist configuration ensures low weight and optimized energy consumption, both of which are crucial for maintaining the drone's flight autonomy.

These sensors were chosen based on the project's specific objectives. GPS data enables the route to be recorded, and combining information from LiDAR and the camera facilitates victim positioning and awareness of nearby obstacles.

The ESP32S3 runs optimized code to streamline video transmission and ensure the best possible video quality in operational conditions. It also exposes specific endpoints, enabling detailed sensor data to be retrieved on demand. Data is transmitted via Wi-Fi (2.4 GHz, 802.11 b/g/n).

3.3. Delivery Module

In addition to its monitoring functions, the system includes an integrated package delivery module designed to provide immediate assistance to identify individuals. The release mechanism, which controls the opening and closing of the clamping system, is powered by a servo motor (e.g., SG90 or similar) that is directly integrated into the 3D-printed structure. The servo motor is remotely controlled and connected to the flight controller, enabling the human operator to operate it remotely based on decisions made in the command center, potentially with the assistance of recommendations from the cognitive architecture.

Figure 4 illustrates the modular design of the package's fastening and release system, showing the 3D-printed conceptual components and an example package.

As shown in

Figure 5, the drone can transport and release controlled first aid packages containing essential items such as medicine, a walkie-talkie for direct communication, a mini-GPS for location tracking and food rations. This module has an estimated maximum payload of 300–700 g, enabling critical resources to be transported. Integrating this module transforms the drone from a passive observation tool into an active system that can rapidly intervene by delivering critical resources directly to victims in emergency situations.

3.4. Drone Command Center

The drone command center, also known as the Ground Control Station (GCS), forms the operational and computational core of the entire system. Implemented as a robust web application with a ReactJS frontend and a Python backend, it ensures a scalable and maintainable client-server architecture.

The command center's role goes beyond that of a simple visualization interface. It functions as a central hub for data fusion, intelligent processing, and decision support. Its main functionalities are:

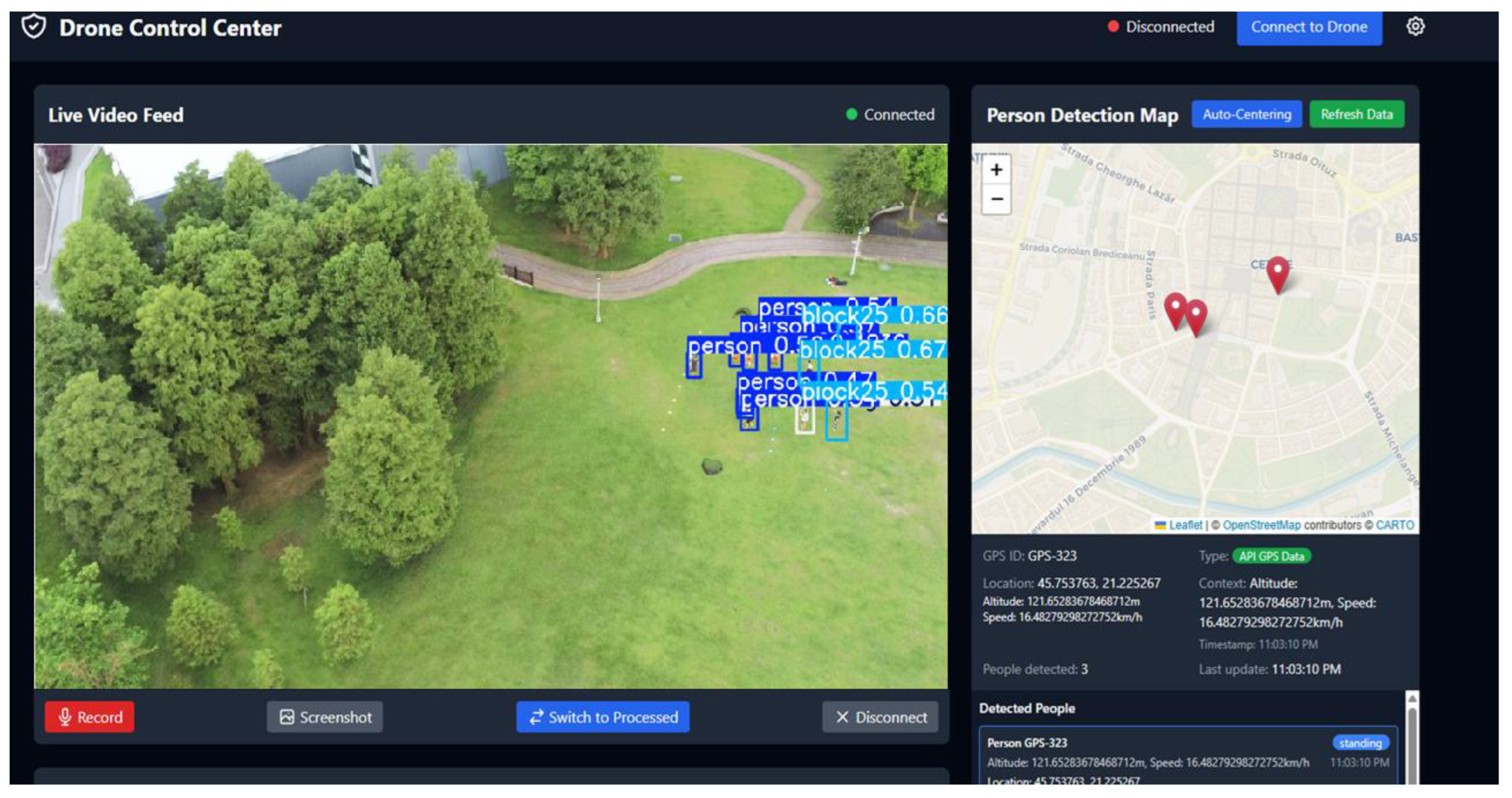

Human-Machine Interface (HMI): The front end gives the human operator complete situational awareness. A key feature is the interactive map, which displays the drone's position in real time, the precise location of any detected individuals and other relevant geospatial data. At the same time, the operator can view the live video stream annotated in real time by the detection module which highlights victims and classifies their status (e.g., walking, standing, or lying down).

Figure 6 shows the visual interface of the central application, which consolidates these data streams.

- 2.

-

Perceptual and cognitive processing: One of the fundamental architectural decisions behind our system is to decouple AI-intensive processing from the aerial platform and host it at the GCS level. The drone acts as an advanced data collection platform, transmitting video and telemetry data to the ground station. Here, the backend takes this data and performs two critical tasks:

- a.

Visual detection: Uses the YOLO11 object detection model to analyze the video stream and extract semantic information. This off-board approach allows the use of complex, high-precision computational models, that would otherwise exceed the hardware capabilities of resource-limited aerial platforms.

- b.

Agentic Reasoning: The GCS hosts the entire cognitive-agentic architecture. This architecture is detailed in Section 6. All interactions between AI agents, including contextual analysis, risk assessment and recommendation generation, take place at the ground server level.

This centralization of intelligence enables our system to surpass the standard AI functionalities integrated into commercial drones, which typically focus on flight optimization (e.g., AI Spot-Check or Smart Pin & Track). Our system offers a deeper reasoning and contextual analysis capabilities.

Furthermore, the command center is the interface point where prioritized recommendations generated by the cognitive-agentic architecture are presented to the operator. This centralization of raw data, processed information (via YOLO), and intelligent suggestions (from the agentic architecture) transforms GCS into an advanced decision support system, enabling human operators to efficiently manage complex disaster response scenarios.

4. Visual Detection and Classification with YOLO

Object detection is a fundamental task in computer vision, essential for enabling autonomous systems to perceive and interact with their environment [

23]. In the context of SAR operations, the ability to quickly identify and locate victims is of critical importance. For real-time applications, such as analyzing video streams from drones, an optimal balance between speed and detection accuracy is required [

24].

For our system, we chose a model from the YOLO (You Only Look Once) family due to its proven performance, flexibility, and efficiency [

25], and we chose to train it with datasets specialized in detecting people in emergency situations. To ensure robust performance in the complex and unpredictable conditions of disaster areas, we adopted a training strategy focused on creating a specialized dataset and optimizing the learning process. In the following, we will focus on how the model was adapted and trained to recognize not only human presence, but also various actions and states (such as walking, standing, or lying down).

4.1. Construction of the Dataset and Class Taxonomy

To address the specifics of post-disaster operations and optimize processing, we implemented a model based on YOLOv11l, trained by us. We built a composite dataset by aggregating and adapting two complementary sources to maximize the generalization and robustness of the module used [

26]:

C2A Dataset: Human Detection in Disaster Scenarios [

27] - This dataset is designed to improve human detection in disaster contexts.

NTUT 4K Drone Photo Dataset for Human Detection [

28] – It is a dataset designed to identify human behavior. It includes detailed annotations for classifying human actions.

Our objective goes beyond simply detecting human presence; we aim to achieve a semantic understanding of the victim's condition, which is vital information for the cognitive-agentic architecture. To this end, the model has been trained on a detailed taxonomy of classes designed to differentiate between states of mobility and potential distress. The classes are grouped into two main categories with clear operational significance for SAR missions:

-

States of Mobility and Action: This category helps the system distinguish between individuals who are mobile and likely at lower risk, versus those who may be incapacitated

- ○

High-Priority/Immobile (sit): This is the most critical class for SAR scenarios. It is used to identify individuals who are in a static, low-profile position, which includes not only sitting but also lying on the ground or collapsed. An entity classified as sit is treated as a potential victim requiring urgent assessment.

- ○

Low-Priority/Mobile (stand, walk): These classes identify individuals who are upright and mobile. They are considered a lower immediate priority but are essential for contextual analysis and for distinguishing active survivors from incapacitated victims.

- ○

General Actions (person, push, riding, watchphone): Derived largely from the NTUT 4K dataset, these classes help the model build a more robust and generalized understanding of human presence and posture, improving overall detection reliability even if these specific actions are less common in disaster zones.

-

Visibility and Occlusion: This category quantifies how visible a person is, which is crucial for assessing if a victim might be trapped or partially buried

- ○

Occlusion Levels (block25, block50, block75): These classes indicate that approximately 25%, 50%, or 75% of the person is obscured from view.

The final dataset, consisting of 5773 images, was randomly divided into training (80%), validation (10%), and testing (10%) sets. This division ensures that the model is evaluated on a set of completely unseen images, providing an unbiased assessment of its generalization performance.

4.2. Data Preprocessing and Hyperparameter Optimization

To maximize the model's potential and create a dynamic detector, we applied two types of optimizations:

Data augmentation: The techniques applied consisted exclusively of fixed rotations at 90°, random rotations between -15° and +15°, and shear deformations of ±10°. The purpose of these transformations was to artificially simulate the variety of viewing angles and target orientations that naturally occur in dynamic landscapes filmed by a drone, forcing the model to learn features that are invariant to rotation and perspective.

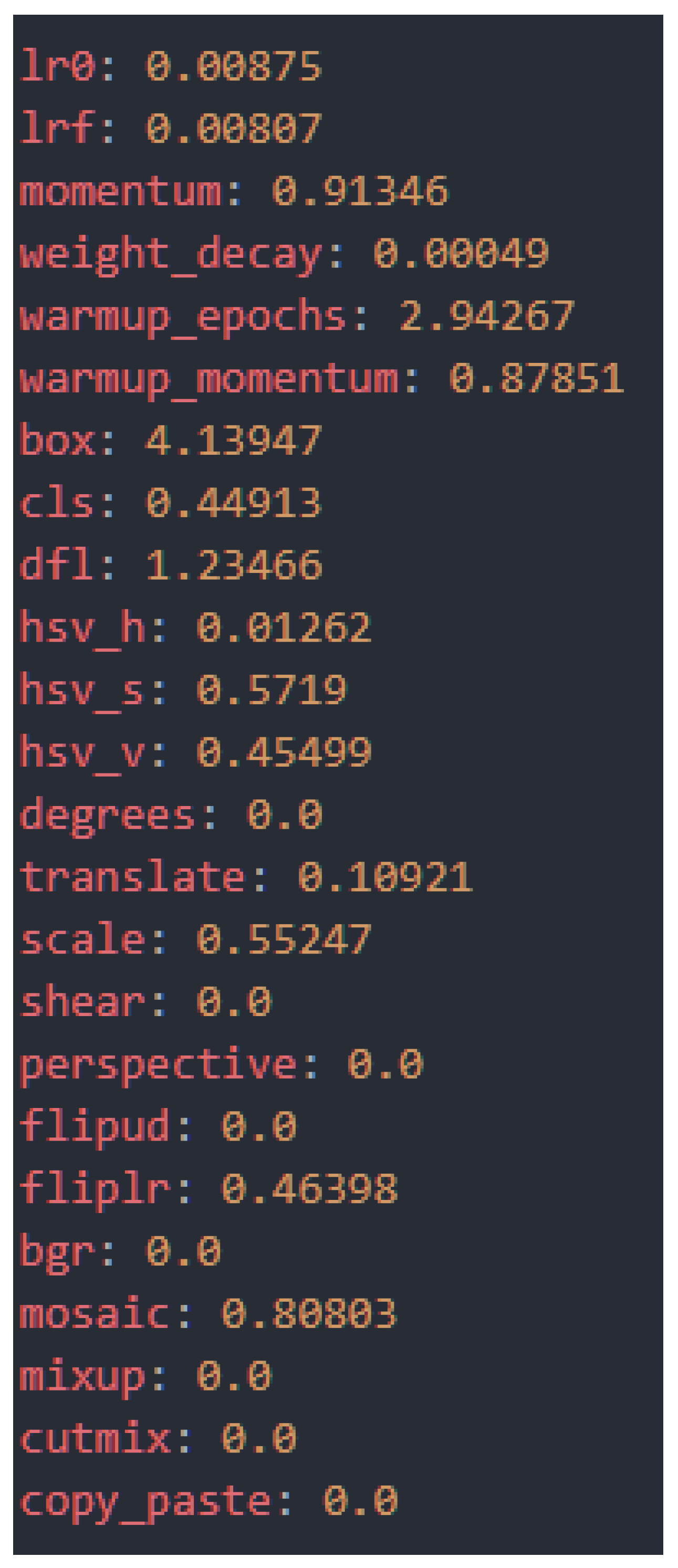

Hyperparameter optimization: Through a process of evolutionary tuning consisting of 100 iterations, we determined the optimal set of hyperparameters for the final training. This method automatically explores the configuration space to find the combination that maximizes performance. The resulting hyperparameters, which define everything from the learning rate to the loss weights and augmentation strategies, are shown in

Figure 7.

4.3. Experimental Setup and Validation of Overall Performance

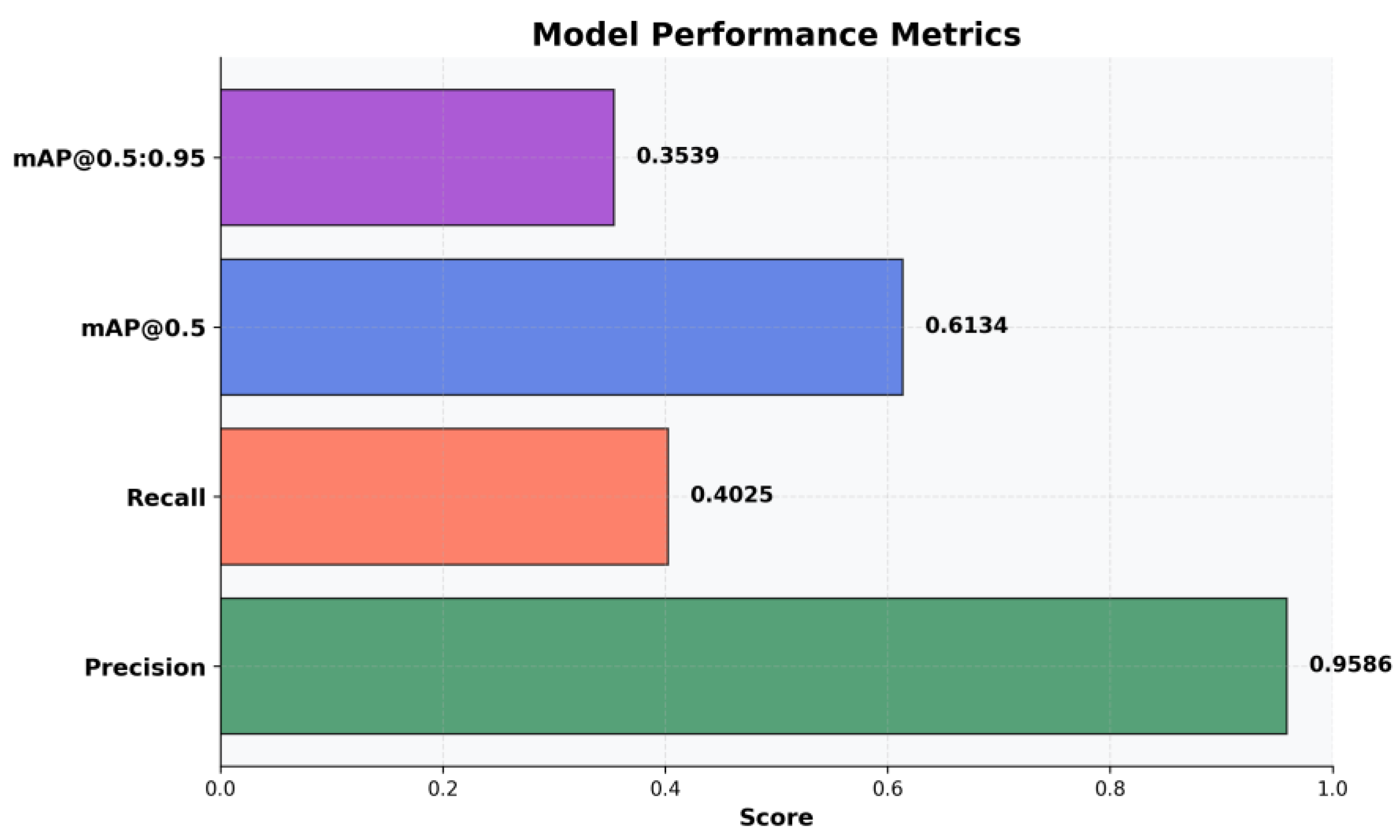

When developing an artificial intelligence model for visual tasks, such as object detection, demonstrating functionality is not enough; an objective, standardized evaluation based on quantitative indicators is required. Graphically represented performance metrics provide a clear quantification of the model's precision, accuracy, and efficiency, facilitating the identification of strengths and limitations, as well as informing optimization decisions. The graph in

Figure 8 highlights four key indicators:

Precision (0.9586 / 95.86%) indicates the proportion of correct detections out of the total number of detections performed. The high value reflects a low probability of erroneous predictions and high confidence in the model's results.

The Recall (0.4025 / 40.25%) expresses the ability to identify objects present in the image. The relatively low value suggests the omission of about 60% of objects. This is explained by the increased complexity of the training set due to the concatenation of two datasets, which reduces raw performance but increases the generalization and versatility of the model.

mAP@0.5 (0,6134 combines Precision and Recall, evaluating correct detections at an intersection over union (IoU) threshold of 50%. The result indicates balanced performance, despite the low Recall.

mAP@0.5:0.95 (0,3539) measures the accuracy of localization at strict IoU thresholds (50%–95%). The value significantly lower than mAP@0.5 suggests that, although the model detects objects, the generated bounding boxes are not always well adjusted to their contours.

In conclusion, quantitative analysis shows that the trained model has the profile of a highly reliable but conservative system. It excels at avoiding classification errors (high accuracy), at the cost of omitting a considerable number of targets and imperfect border localization.

4.4. Granular Analysis: From Aggregate Metrics to Error Patterns

To understand the model's behavior in depth, it is necessary to go beyond aggregate metrics and examine performance at the individual class level and the specific types of errors committed.

4.4.1. Classes Performance

The per-class performance analysis reveals a heterogeneous picture, highlighting an important compromise. On the one hand, the model achieves excellent Mean Average Precision (mAP) for distinct classes such as riding (97.8%), standing (96.4%), and sitting (90.5%), indicating that the detections made are extremely reliable. On the other hand, the recall (ability to find all instances) for these same classes is only moderate (stand: 48%, sit: 40%), which means that the model does not identify all existing targets.

The poor performance on underrepresented classes (block, push) confirms the negative impact of data imbalance, while the solid recall for the person class (72%) ensures robust basic detection. A detailed analysis of the performance for each class is presented in

Figure 9.

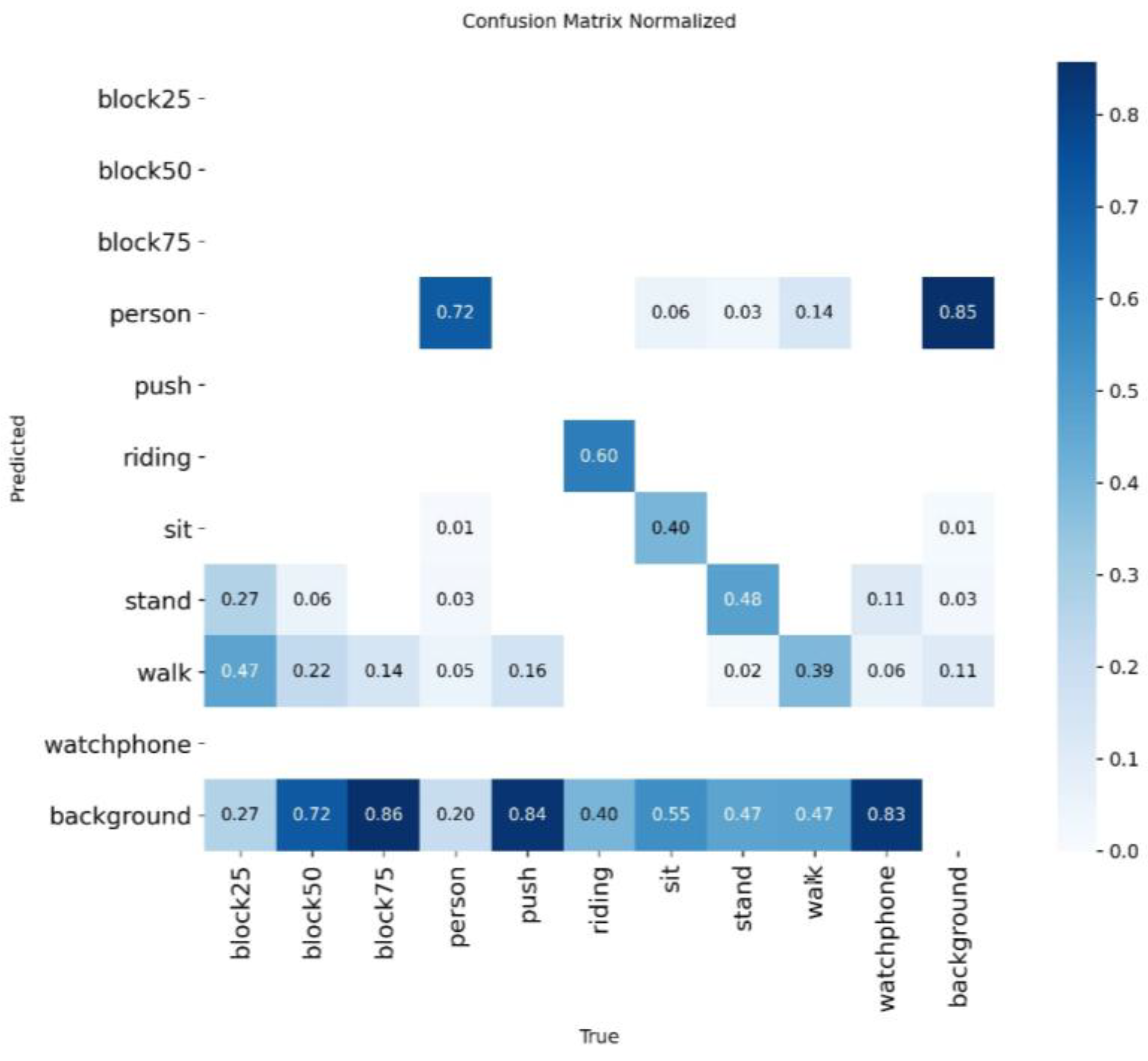

4.4.2. Diagnosing Error Patterns with the Confusion Matrix

To gain a deeper understanding of inter-class relationships and classification errors, we present a normalized confusion matrix in

Figure 10. This analysis is critical for linking the model's technical performance to its operational value in SAR scenarios, particularly in addressing the low overall recall rate of 40.25%.

The main diagonal of the matrix confirms moderate recall for specific postural states, such as stand (48%), sit (40%), and walk (39%). While these figures indicate a conservative model, a granular analysis of its error patterns reveals a crucial strength in terms of operational safety.

A. Analysis of Semantic Confusion and Critical Distinctions

The evaluation of a model for critical applications like SAR requires a contextual interpretation of its errors. A key observation is the model's interaction with the background. The model exhibits a high false-negative rate—a significant number of real instances, especially from the walk class (47%), are omitted and misclassified as background. This conservative tendency is the primary reason for the low overall recall.

This can be mitigated by the fact that YOLO algorithm is applied to every frame retrieved from the drone, and at around 20 frames per second this recall will be substantially lowered. Considering that a person can stay on the camera for around 2-3 seconds and combined with little changes in perspective and angle in the view, this recall shows that from a minimum of 40 frames, the person is detected in at least 16 frames.

However, this is balanced by a remarkably low false-positive rate: 85% of regions labeled as background are correctly identified, meaning the system generates very few false alarms from environmental noise. This trade-off, while impacting recall, is operationally preferable to a system that creates numerous false distractions for the human operator.

Most importantly, the model excels at the most critical distinction for SAR: separating high-risk, immobile victims from low-risk, mobile individuals. The confusion matrix validates this fundamental objective. There is minimal confusion between the high priority sit state (which includes lying victims in the dataset) and mobile states; only 2% of sit instances are misclassified as walk. This clear semantic separation is the most important evidence of the model's current utility. It ensures that the downstream cognitive-agentic architecture receives reliable data to prioritize rescue efforts, effectively avoiding the most dangerous error: classifying a victim in critical need as a low-priority mobile person.

In summary, while the absolute recall is a clear area for improvement, the model's current performance is operationally sound for this proof-of-concept stage. Its main value lies in the reliable separation of critical states from non-critical ones, fulfilling the primary objective of providing consistent, high-confidence data to the cognitive architecture for feasibility testing.

5. Geolocation of Detected Targets

Once a victim has been detected and classified by the YOLO-based visual perception module, establishing their precise location becomes the next critical priority. These geographical coordinates are essential input for the perception agent (PAg) and subsequently for the entire cognitive architecture's decision-making chain. Without accurate geolocation, the system's ability to assess risks and generate actionable recommendations can be severely compromised.

5.1. Methodology for Estimating Position

To estimate the actual position of a person detected in the camera image, we implemented a passive, monocular geolocation method that merges visual data with drone telemetry [

29].

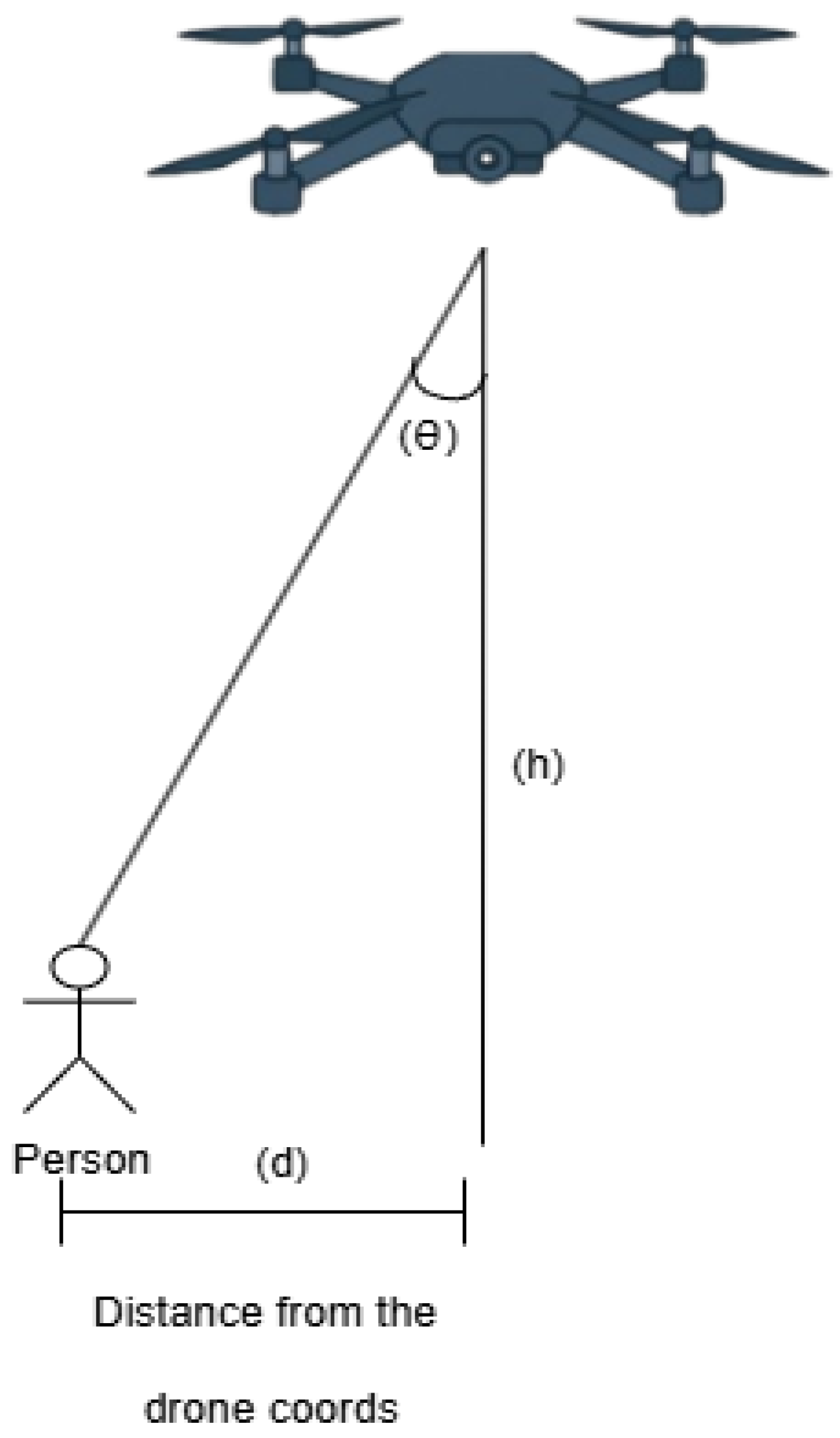

The mathematical model uses the following input parameters to calculate the geographical coordinates of the target (P) based on the drone's position (D):

): The geographical coordinates (latitude, longitude) of the drone, provided by the GPS module;

: Height of the drone above the ground;

: The vertical deviation angle, representing the angle between the vertical axis of the camera and the line of sight to the person. This is calculated based on the vertical position of the person in the image and the vertical field of view (FOV) of the camera;

: This value is provided by the magnetometer integrated into the flight controller's inertial measurement unit (IMU) and is crucial for defining the projection direction of the visual vector [

30];

: The estimated geographical coordinates of the person are the final result of the calculation.

First, the horizontal distance (d) from the drone's projection on the ground to the target is determined using simple trigonometry, according to Equation (1):

Once the starting point (GPS coordinates of the drone), distance (d), and direction (azimuth

) are known, the geographical coordinates of the target

can be calculated. To do this, the spherical cosine law formulas are used, which model the Earth as a sphere to ensure high accuracy over short and medium distances. The estimated coordinates of the person are calculated using Equations (2) and (3):

where,

is the angular distance, and R is the mean radius of the Earth (approximately 6,371 km).

We chose this method because of its computational efficiency. Error analysis shows that, for a FOV of 120° and a maximum flight altitude of 120 m, the localization error is approximately 1 meter, a margin considered negligible for intervention teams [

31]. We consider it negligible because at 20m the possible error drops to around 17 cm.

The angle

crucial for correctly positioning the person in the global coordinate system, as it indicates the direction in which the drone is facing. In the context of

Figure 11, the angle

is not explicitly visible, as the figure simplifies the projection to illustrate our additional calculation compared to the classical equations.

To illustrate the method, consider a practical scenario in which the drone identifies a target on the ground. The flight and detection parameters at that moment are:

Flight height (h): 27 m;

GPS position of the drone ): (45.7723°, 22.144°);

Drone orientation (): 30° (azimuth measured from North);

Vertical deviation angle (): 25° (calculated from the target position in the image).

Using Equation (1), the horizontal distance (d) is:

To convert this distance into a geographical position, Equations (2) and (3) are applied, first converting the values into radians:

Earth's radius (R): 6,371,000 m;

Angular distance (): ;

Azimuth (): ;

Drone latitude ): ;

Drone longitude .

Applying the equations, the estimated coordinates of the person are obtained:

These precise geographical coordinates are transmitted to the perception agent (PAg) to be integrated into the cognitive model of the system and subsequently displayed on the interactive map of the command center to visually identify the location and status of the target in the context of the mission.

6. Cognitive Agent Architecture

To function effectively in complex and dynamic environments such as search and rescue scenarios after disasters, an autonomous system requires not only perception and action capabilities, but also superior intelligence for reasoning, planning, and adaptation [

32]. Traditional, purely reactive systems, which only respond to immediate stimuli, are inadequate for these challenges [

33,

34]. To overcome these limitations, we propose an agentic cognitive architecture inspired by human thought processes. This architecture provides a structured framework for organizing perception, memory, reasoning, and action modules [

35].

The key contribution of this work is the modular architecture centered on a Large Language Model (LLM) serving as the Orchestrator Agent. This agent handles complex reasoning, logical data validation, and self-correction through feedback loops [

36,

37]. In doing so, the system evolves from a simple data collector into an intelligent partner [

38], capable of processing heterogeneous information [

39], transforming raw inputs into actionable knowledge [

40], prioritizing tasks, and making optimal decisions under uncertainty and resource constraints.

This chapter introduces the proposed architecture, outlining the roles of its specialized agents and describing the communication flow that enables a complete perception–reasoning–action cycle [

41].

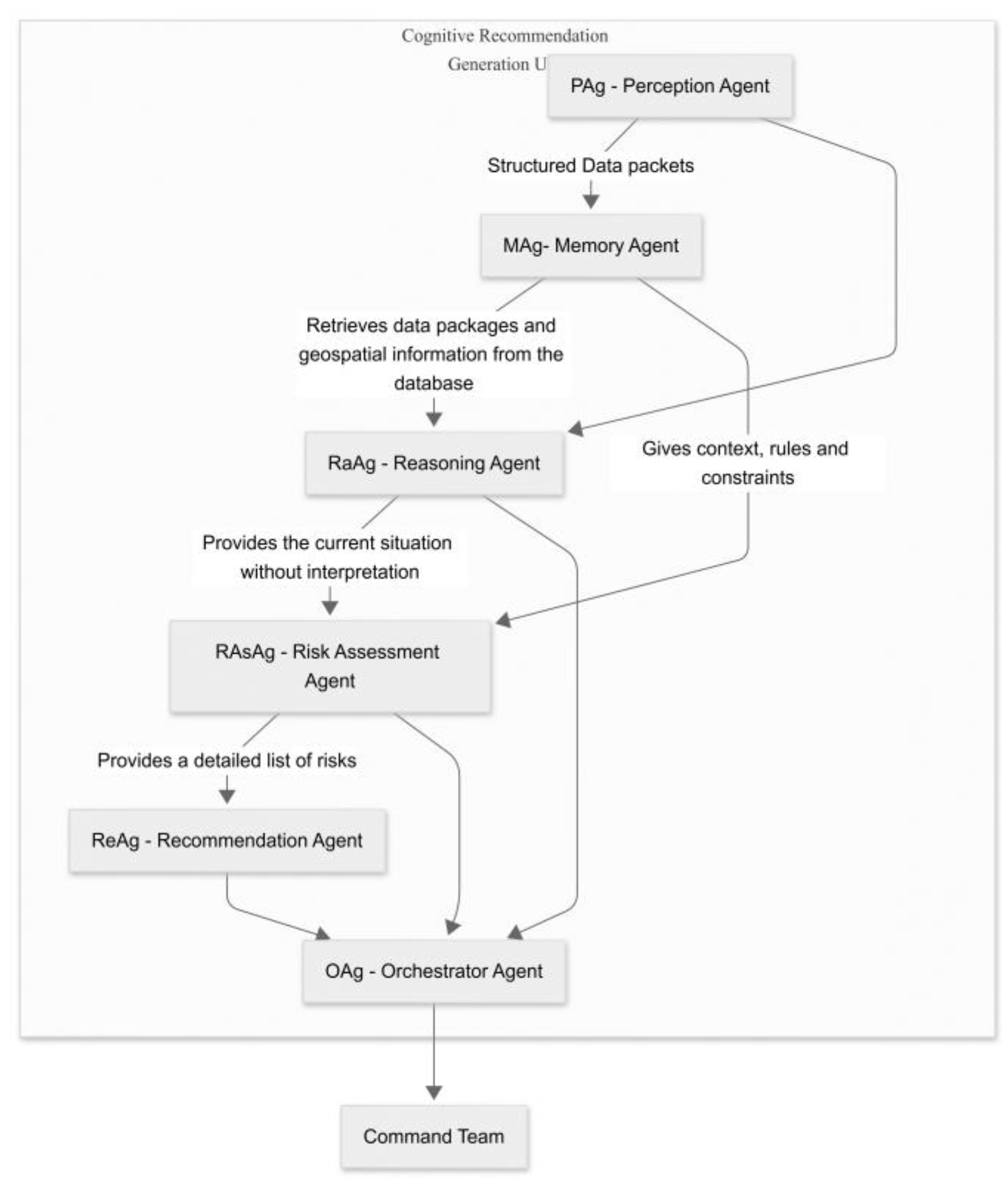

6.1. Components of the Proposed Cognitive-Agentic Architecture

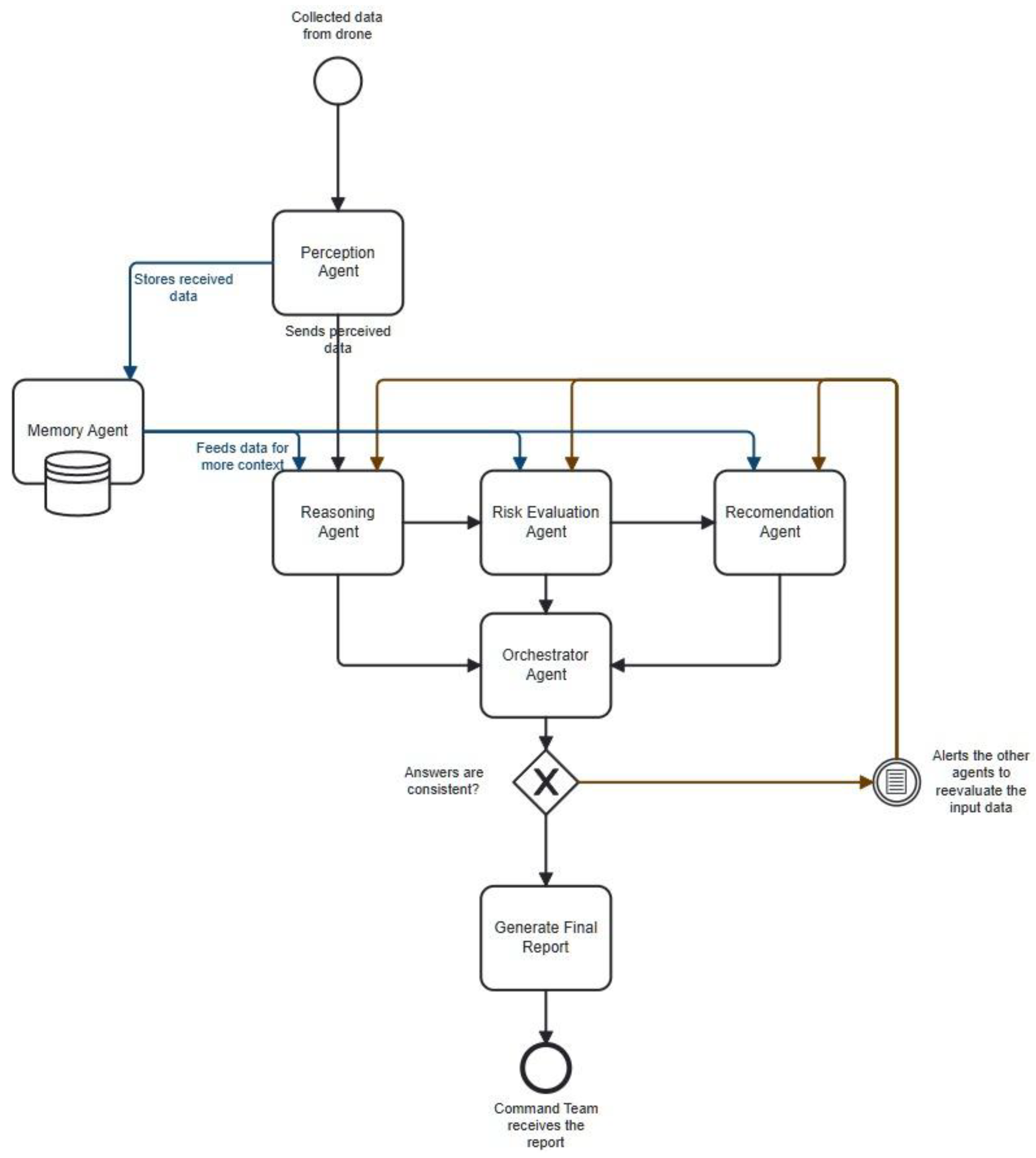

As illustrated in

Figure 12, the system architecture is designed as a complete cognitive flow, orchestrating the processing of information from data acquisition to decision consolidation for the command team. It follows a modular, interconnected model in which each software agent has a specialized role.

The agents are implemented using Google’s Agent Development Kit (ADK) [

42]. The cognitive core is the LLM Gemma 3n E4b, which enhances reasoning, contextual evaluation, and decision-making. Agents communicate via a Shared Session State, acting as a centralized working memory to ensure data consistency.

In cognitive architecture, the Perception Agent (PAg) acts as an intelligent interface between perceptual data sources and the system's rational core. Its primary role is to aggregate heterogeneous, partially processed data, such as visual detections, GPS locations, associated activities and drone telemetry data, and convert it into a standardized, coherent internal format.

This involves validating data integrity, normalizing format variations (e.g., GPS coordinates), and creating a coherent representation of the environment (e.g., JSON). The result provides the necessary context for reasoning, planning, and decision-making agents.

6.1.2. MAg – Memory Agent

The proposed cognitive-agentic architecture incorporates an advanced memory system modeled on human cognition, which is structured into two key components: a volatile short-term (working) memory and a persistent long-term memory.

Working memory is implemented via the LLM's context window. This acts as a temporary storage space where real-time data (e.g., YOLO detections, drone position), the current mission status, and recent decision-making steps are actively processed. However, this memory is ephemeral; information is lost once it leaves the context window.

To overcome this limitation, the Memory Agent (MAg) manages the system's long-term memory. The MAg serves as a distributed knowledge base for the persistent storage of valuable information, such as geospatial maps, flight rules, mission history, and intervention protocols. These are stored and retrieved with the help of a MCP Server that enables communication between database and the agent. This dynamic interaction between immediate perception (in working memory) and accumulated knowledge (in long-term memory) is fundamental to the system's cognitive abilities.

The value of this dual-memory system is best illustrated with a practical example. During a surveillance mission, the drone detects a person (P1). This real-time information is held in the agent's working memory. To assess the context, the agent queries the MAg to check if the person's location corresponds to a known hazardous area. The MAg returns the fact that the location is a "Restricted Area." By integrating this retrieved knowledge with the live data, the agent can correctly identify the situation as dangerous and trigger an appropriate response, such as alerting the operator.

6.1.3. RaAg - System Reasoning

The Reasoning Agent (RaAg) is the system's primary semantic abstraction component, responsible for transforming raw sensory streams into structured, contextualized representations. Receiving pre-processed inputs from the Perception Agent (PAg), including GPS coordinates, timestamps and categories of detected entities, it correlates these with related knowledge from long-term memory (MAg), such as maps of risk areas and operational constraints.

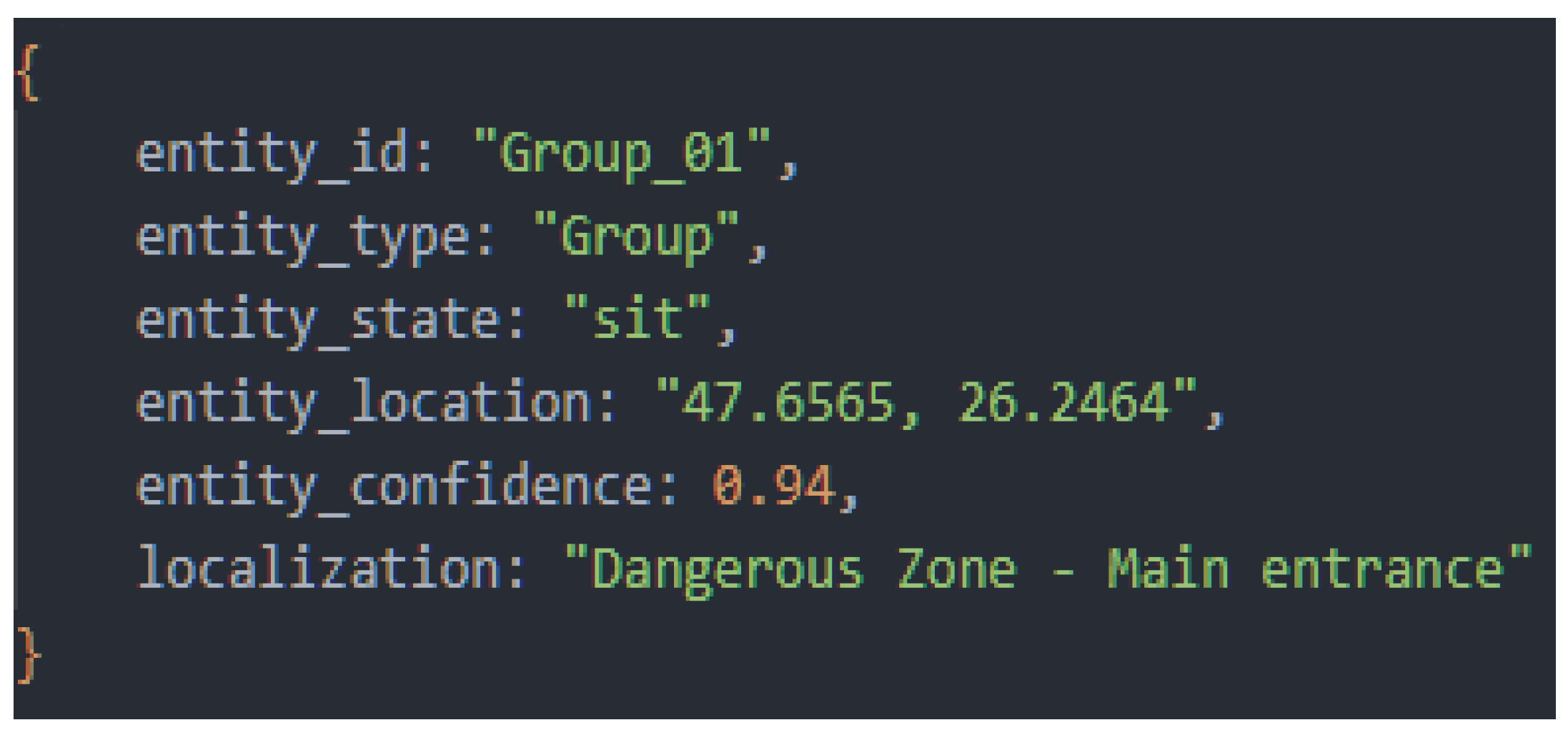

Through the fusion mechanism, RaAg generates contextualized facts. For example, reporting a person's coordinates triggers an inter-query in MAg to determine their membership of a predefined area. The result is a semantic structure present in

Figure 13.

The Reasoning Agent is mandated to perform the first layer of intelligent analysis by transforming the standardized perceptual data from the PAg into a contextualized factual report. Its core "prompt" is to take a given set of perceptual inputs (such as an entity's GPS location and category) and enrich it by fusing it with relevant information from the long-term memory. The agent is instructed to actively query the MAg to answer questions like, "Does this location fall within a predefined risk area?" or "Are there any operational constraints associated with this entity?". The expected output is a new, structured representation that objectively describes the situation (e.g., "Person P1 is located inside hazardous Zone B") without making any judgment on the level of danger.

This objective representation, created without an initial risk assessment, forms the basis of the Risk Assessment Agent's (RAsAg) decision-making process, as outlined in

Section 6.1.4.

6.1.4. RAsAg – Risk Assessment Agent

The Risk Assessment Agent (RAsAg) takes the contextualized report from RaAg and assigns operational significance in terms of danger. The agent's significant role is to convert objective facts (e.g., 'Person in Zone A') into quantitative assessments and risk prioritizations.

To achieve this, RAsAg uses a set of rules, heuristics and risk scenarios that are stored in its long-term memory of the MAg. This model is composed of a set of production rules. Each rule is defined as a tuple, structured to map specific conditions from the factual report of RAsAg to a structured and quantifiable risk report.

Rule R is formally defined as a 4-element tuple: R = (Rule_ID, Condition, Action, Severity) where:

Rule_ID: A unique identifier for traceability (e.g., R-MED-01).

Condition (C): The description of the rule prerequisites it to act.

Action (A): The process of generating the structured risk report, specifying the Type, Severity, and Justification.

Severity (S): A numerical value that dictates the order of execution in case multiple rules are triggered simultaneously. A higher value indicates a higher priority.

Some examples are present in

Table 2.

Based on these rules, the agent analyses the factual report and generates a risk report. This report contains:

Type of risk

Severity level: a numerical value, where 1 means low risk and 10 means high risk

Entities involved: ID of the person or area affected or coordinates

Justification: A brief explanation of the rules that led to the assessment

The Risk Assessment Agent is mandated to execute a critical evaluation function: to translate the objective, contextualized facts provided by RaAg into a quantifiable and prioritized assessment of danger. The agent is prompted to take the factual report as input and systematically compare it against a formalized set of rules, heuristics, and risk scenarios stored in the long-term memory (MAg). The core instruction is to find the rule whose conditions best match the current situation, using the rule's Severity value to resolve any conflicts. The expected output is a new, structured risk report that must contain four distinct fields: the Type of risk, a numerical Severity level, the Entities involved, and a Justification explaining the rule that triggered the assessment.

The resulting report is forwarded to the Recommendation Agent and Orchestrator Agent for further action.

6.1.5. ReAg – Recommendation Agent

The agent receives the risk assessment report from RAsAg and queries a structured operational knowledge base containing response protocols for different types of hazards. Based on the risk's severity, location and context, the agent generates one or more parameterized actions (e.g., alerting specific authorities or activating additional monitoring). The result is a set of actionable recommendations that provide the autonomous system or human operator with justified operational options for managing the identified situation.

6.1.6. Consolidate and Interpret (Orchestrator Agent)

The final and most critical stage of the cognitive cycle is managed by the central Orchestrator Agent (OAg), which acts as the system's ultimate cognitive authority and final decision-maker.

Its process begins by ingesting and synthesizing the consolidated reports from all specialized sub-agents (RaAg, RAsAg, and ReAg) to form a complete, holistic understanding of the operational situation. Crucially, its role extends beyond simple aggregation. The OAg is mandated to perform a "meta-reasoning" validation, using the LLM's capabilities to scrutinize the logical consistency of the incoming information against the master protocols stored in the Memory Agent (MAg). It can detect subtle anomalies that specialized agents, with their narrower focus, might overlook. For instance, if RaAg reports 'a single motionless person' while RAsAg assigns a 'Low' risk level, the Orchestrator immediately recognizes this discrepancy.

If an inconsistency is found, the agent does not proceed with a flawed decision. Instead, it initiates its self-correcting feedback loop, issuing a new, corrective prompt to the agent in question (e.g., "Inconsistency detected. Re-evaluate the risk for Entity P1...").

Only after achieving a fully coherent and validated state—either initially or following a corrective cycle—does the Orchestrator execute its final directive. It uses the ‘make_decision’ tool to analyze the complete synthesis and issue the single most appropriate command, whether it's a critical alert for the human operator or the autonomous activation of the delivery module. This robust, iterative process ensures that the system closes the perception-reasoning-action loop with a high degree of reliability.

6.1.7. Inter-Agent Communication and Operational Flow

Inter-agent communication is the nervous system of the proposed cognitive-agentic architecture and is essential for the system's coherence and agility. The architecture implements a hybrid communication model that combines passive data flow with active, intelligent control orchestrated by the LLM core. This model is based on three fundamental mechanisms, as shown in

Figure 14.

Shared session state: This mechanism represents the sequential analysis flow column. It acts as a shared working memory, or 'blackboard', where specialized agents publish their results in a standardized format (e.g., JSON). The blackboard model is a classic AI architecture recognized for its flexibility in solving complex problems [

43]. The flow is initiated by PAg, which writes the normalized perceptual data. Subsequently, RaAg reads this data and publishes the contextualized factual report, which RAsAg then takes over to add the risk assessment. Finally, ReAg adds recommendations for action to complete the status. This passive model decouples the agents and enables a clear, traceable data flow in which each agent contributes to progressively enriching situational understanding.

Control through tool invocation (LLM-driven tool calling): This active control mechanism means that the Orchestrator Agent is not just a reader of the shared state, but an active conductor. It treats each specialized agent (PAg, RaAg, RAsAg, MAg and ReAg) as a 'tool' that can be invoked via a specific API call. This approach is inspired by recent work demonstrating LLMs' ability to reason and act using external tools. When a new task enters the input queue, the Orchestrator, guided by the LLM, formulates an action plan. Execution of this plan involves sequentially or in parallel invoking these tools to collect the necessary evidence to make a decision [

43,

44,

45,

46].

Feedback and Re-evaluation Loop: The architecture's most advanced mechanism is the feedback loop, which provides robustness and self-correcting capabilities. After the Orchestrator Agent has collected information by calling tools, it validates it internally for consistency. If an anomaly or contradiction is detected (as described in Section 6.2.6), an iterative refinement cycle can be initiated, a process also known as self-reflection or self-correction in intelligent systems. The agent uses the same tool-calling mechanism to send a re-evaluation request to the responsible agent, specifying the context of the problem. This iterative refinement cycle ensures that the final decision placed in the output queue is based on a validated, robust analysis and not just the initial output of the process.

These three mechanisms work together to transform the system from a simple data processing pipeline into a collaborative ecosystem capable of reasoning, verification and dynamic adaptation to real-world complexity.

7. Results

7.1. Validation Methodology

Empirical validation of the cognitive-agentic architecture was performed through a series of synthetic test scenarios designed to reflect realistic situations in Search and Rescue missions. The main objective was to systematically evaluate the core capabilities of the architecture, focusing on four essential capabilities:

Information Integrity: The ability to maintain the consistency and accuracy of data as it moves through the cognitive cycle (from PAg to the final report).

Temporal Coherence (Memory): The effectiveness of the Memory Agent (MAg) in maintaining a persistent state of the environment to avoid redundant alerts and adapt to evolving situations.

Accuracy of Hazard Identification: The accuracy of the system in identifying the most significant threat in a given context.

Self-Correction Capability: The system's ability to detect and rectify internal logical inconsistencies, a key feature of the Orchestrator Agent.

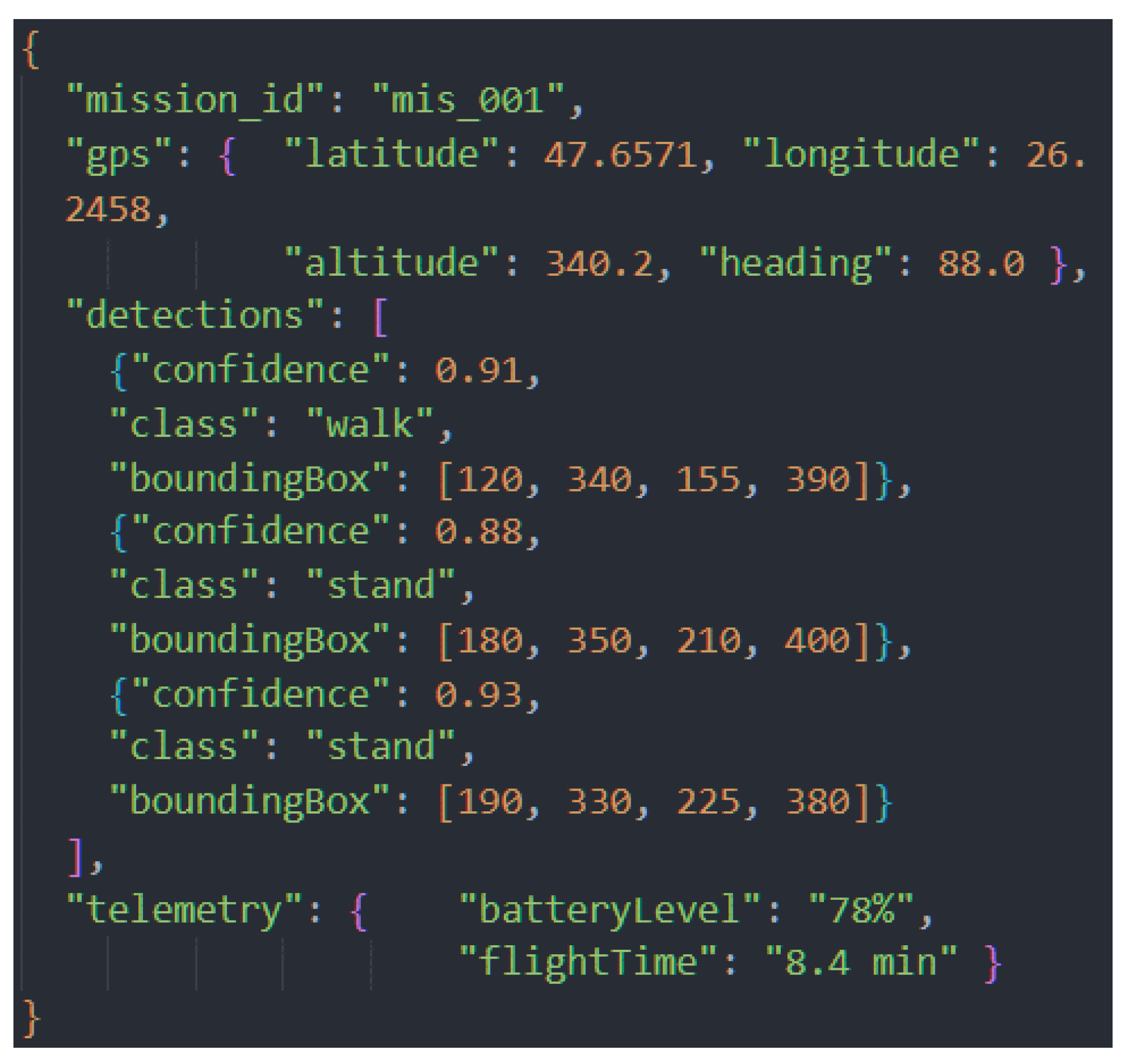

The input data for each scenario, comprising GPS location, camera detections, and drone telemetry, was formatted as a synthetic JSON object, simulating the raw output from the perception module of the ground control station.

7.2. First Scenario – Low Risk Situation

This scenario was designed to evaluate the system's behavior in a situation without events, frequently encountered in monitoring missions: detecting a group of tourists on a marked mountain trail, with no signs of imminent danger.

7.2.1. Initial Data

The data stream received by the Perception Agent (PAg) included GPS location information, visual detections from the YOLO model, and UAV telemetry data. The structure of the raw data is shown in

Figure 15.

PAg performed data standardization and filtering, removing irrelevant fields (e.g., the telemetry error field, which was empty). The objective was to reduce information noise and prepare a coherent set of inputs for the subsequent steps of the cognitive cycle.

7.2.2. Contextual Enrichment (RaAg)

Upon receiving the standardized data set, the Reasoning Agent (RaAg) triggered the contextual enrichment process. First, it retrieved the detections to store them in temporary memory. Then, it queried the long-term memory (MAg), which stores information about the terrain and past actions of the current mission.

The RaAg result included a specific finding: “A group of 3 people was detected: two people standing, one walking.” to which it added the geospatial context of the area where they were located: “The location (47.6571, 26.2458) is on the T1 Mountain Trail, an area with normal tourist traffic, according to the maps in MAg.”.

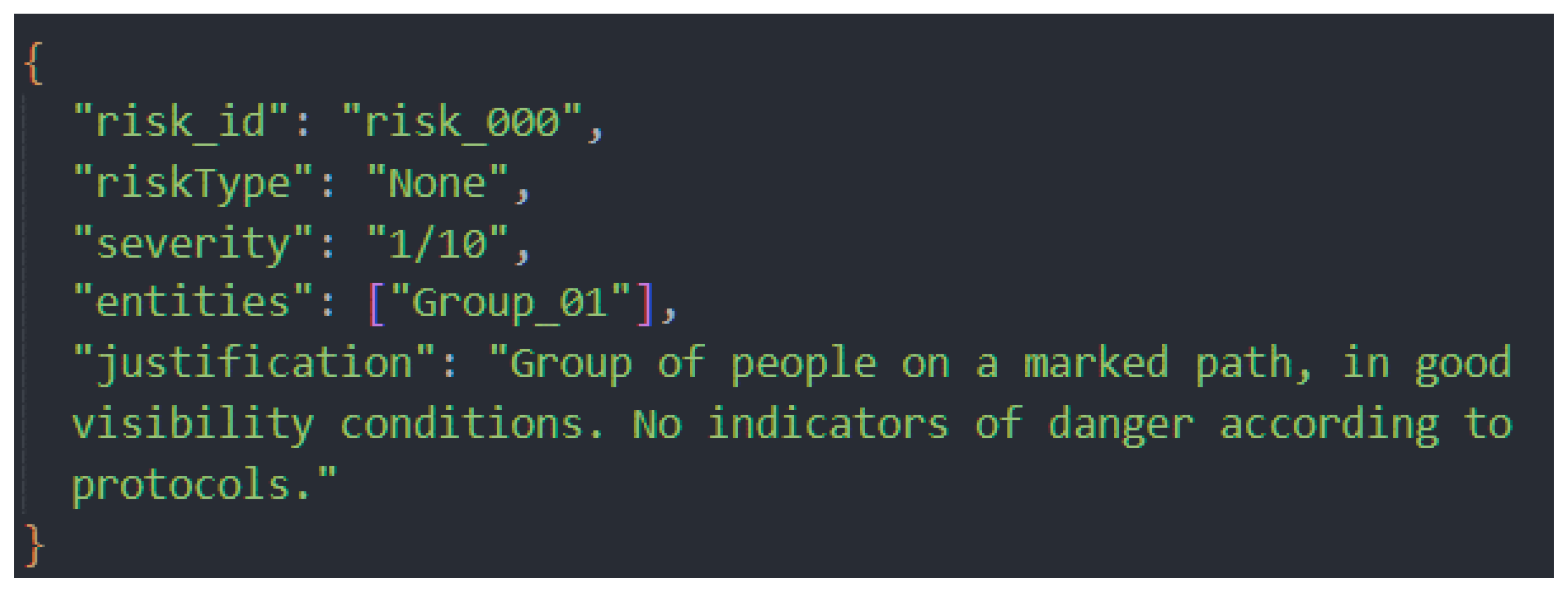

7.2.3 Risk Assessment (RAsAg)

The Risk Assessment Agent (RAsAg) analyzed the detections and geospatial context in relation to the set of rules stored in MAg. The main factors considered were location on a marked route, normal static/dynamic behavior of the group, absence of danger signs in telemetry data.

The result was a low risk assessment, quantified as 1/10 on the severity scale. This result is shown in

Figure 16.

7.2.4. Determining the Response Protocol (ReAg)

Based on the assessment, the Response Agent (ReAg) consulted the operational knowledge base and selected the protocol corresponding to level 1/10, risk ID “risk_000”. The final recommendation was to continue the mission without further action, reflecting the absence of immediate danger.

7.2.5. Final Validation and Display in GCS

The orchestrator verified the logical consistency between:

context: “group of people on a marked path”;

assessment of “low risk (1/10)”;

selected response protocol.

In the absence of any objections, the recommendation was approved. In the GCS interface:

The pins corresponding to individuals were marked in green;

The operator received an informative, non-intrusive notification.

7.3. Second Scenario – High Risk and Self-Correction

This scenario evaluated the system's performance in a critical situation, specifically testing the accuracy of hazard identification and self-correction capabilities.

7.3.1. Description of the Initial Situation

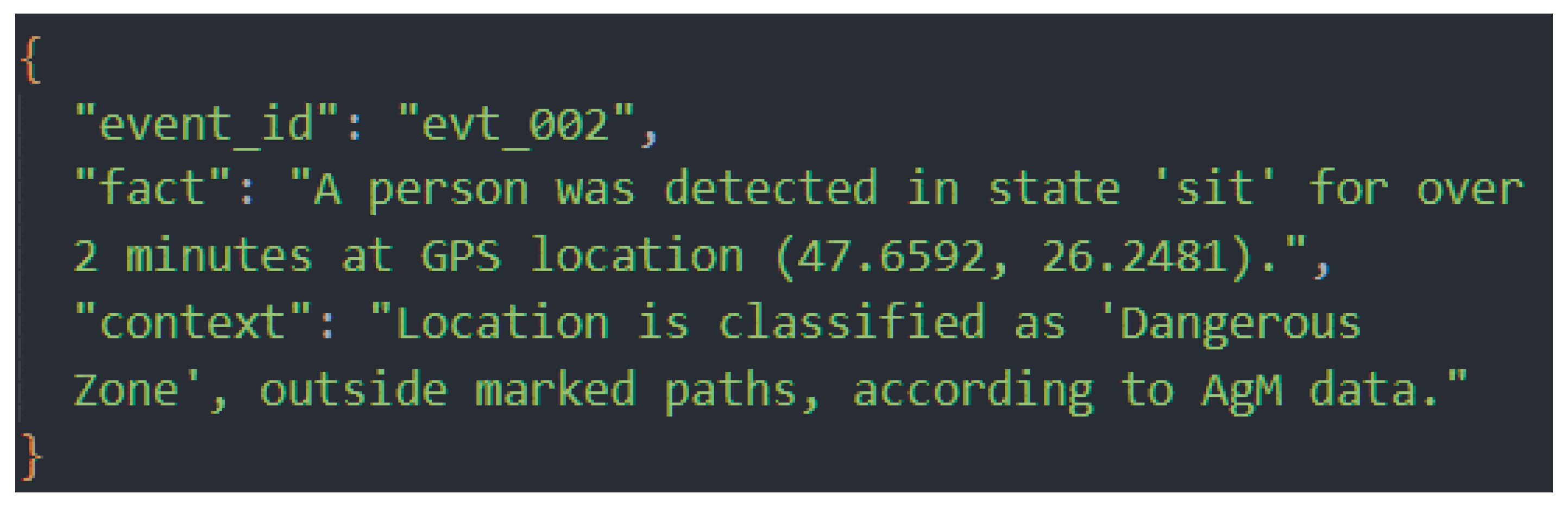

During the initialization phase, the detection of a person in a “sitting” state was simulated, a class classified as important because it refers to people who are lying on the ground or who may not be able to move. The contextualization provided by the RaAg module immediately raised the alert level, transforming a simple detection into a potential medical emergency scenario, as the memory agent (MAg) reported that the same entity had been previously detected at approximately the same coordinates and the interval between detections exceeded 2 minutes, indicating possible prolonged immobility. The area in question was classified as dangerous, being located outside the marked routes, according to MAg data. The data provided by RaAg corresponding to this situation is presented in

Figure 17.

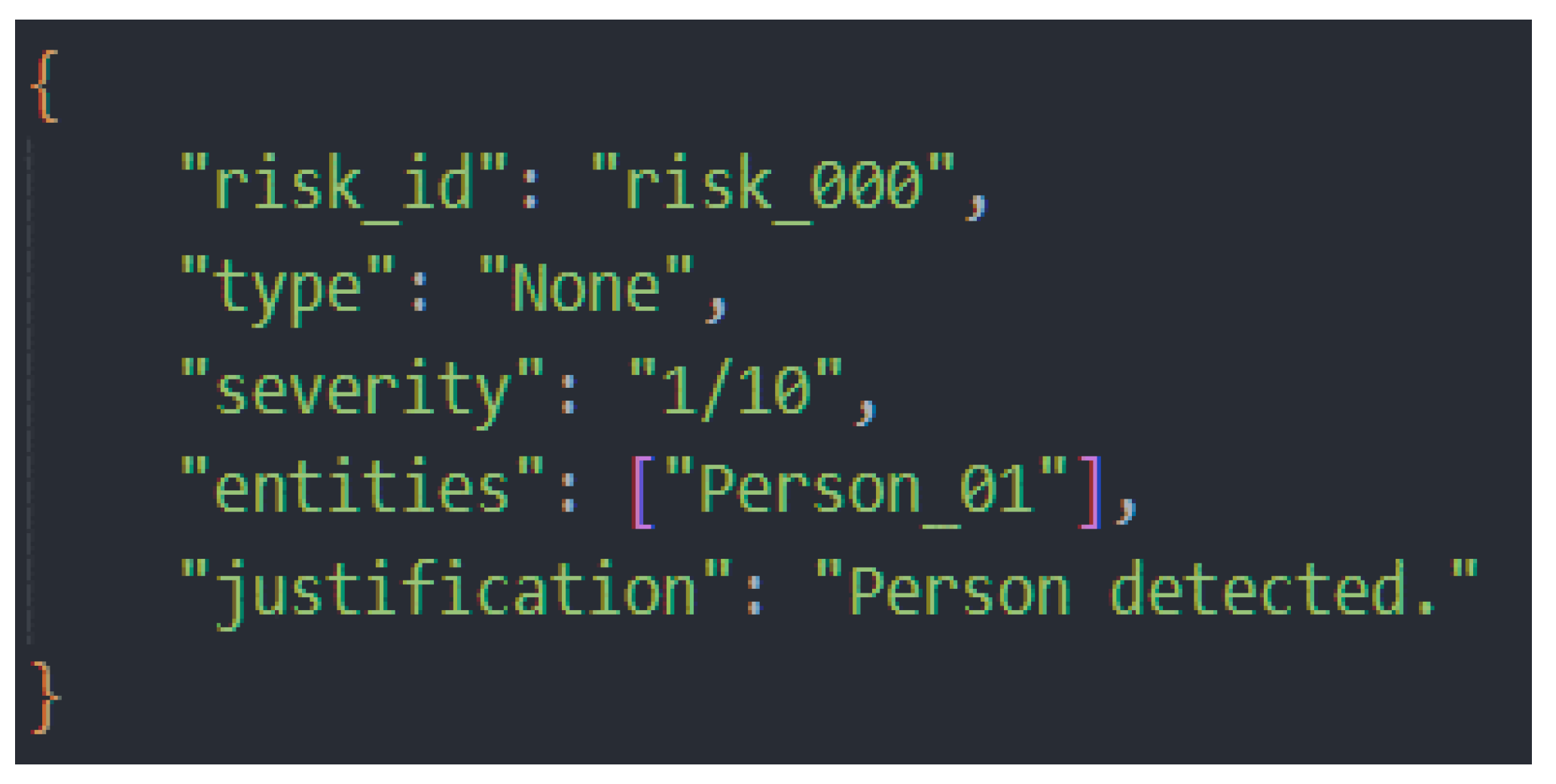

7.3.2. Deliberate Error and System Response

To test the self-correction mechanism, an error was intentionally introduced into the RAsAg module, generating an erroneous risk assessment that directly contradicted the input data presented in

Figure 18.

This assessment indicated a low risk (1/10), despite the fact that the input data described a static subject in a hazardous area for an extended period of time.

7.3.3. Self-Correcting Mechanism

The Orchestrator's supervision function immediately detected a direct conflict between the factual data (static entity, in a dangerous area, time > 2 minutes) and the risk assessment (minimum score, no associated risk type).

In accordance with its architecture, the Orchestrator did not propagate the error but treated RAsAg as a tool that needed to be re-invoked with additional constraints. The message sent to RAsAg was: "Inconsistency detected. Re-evaluate the risk for Entity Person_01 given the ‘sit’ status for >2 minutes. Apply the medical emergency protocol.".

Constrained by the new directive, RAsAg returned a correct assessment aligned with the high-risk rules, and the Orchestrator validated the report as consistent.

7.3.4. Final Result

After validation, the high-risk alert was propagated to the GCS, and the visible actions were:

marking the victim on the interactive map with a red pin;

displaying the detailed report in a prominent window;

enabling immediate intervention by the operator.

Thus, this scenario confirms that the proposed architecture can detect internal errors and automatically correct them before they affect the decision chain, ensuring the robustness and reliability of risk assessment in critical situations.

7.4. Third Scenario – Demonstration of Adaptation

This scenario was designed to evaluate the long-term memory capacity of the system and the contextual adaptation ability of the MAg (Memory Agent) and Orchestrator components. Unlike previous tests, the focus was on temporal consistency and avoiding redundant alerts, which are key to reducing operator fatigue and increasing operational response efficiency.

Following Scenario 1, the MAg internal database already contained an active event (evt_001) associated with the detection of a group of people in an area of interest. After approximately 15 minutes, the PAg (Perception Agent) component transmitted a new detection: five people identified at the same GPS coordinates as in the previous event

The Orchestrator protocol stipulates that, before generating a new event, a query must be made in MAg to determine whether the reported situation represents:

In this case, the check identified a direct spatial-temporal correlation with evt_001. Based on this analysis, the Orchestrator avoided creating a redundant event and instead initiated a procedure to update the existing record.

The instruction sent to MAg was explicitly worded: “Update event evt_001 with the new data received from PAg, maintaining the complete history of observations.”

This action resulted in the replacement of outdated information with the most recent data, while retaining the previous metadata for further analysis.

The test demonstrated the transition of the system from a purely reactive model to a proactive and contextually adaptive one, capable of constructing a persistent representation of the environment. The benefits of this approach include:

Reducing operator cognitive fatigue by limiting unnecessary alerts;

Increasing operational accuracy by consolidating information;

Improving information continuity in long-term missions.

7.5. Cognitive Performance Analysis

In addition to qualitative validation, key performance indicators (KPIs) were measured. The results, summarized in

Table 3, quantify the efficiency and responsiveness of the architecture.

Analysis of these metrics reveals several key observations. As expected, decision time increased in the scenario that required self-correction, reflecting the computational cost of the additional validation cycle. We believe that this increase of ~4 seconds is a fully justified trade-off for the huge gain in reliability and for preventing critical errors of judgment.

To mitigate perceived latency in a real-world deployment, the architecture is designed for pipeline (concatenated) processing. Although a single complete reasoning thread takes 11–18 seconds, the system can initiate a new analysis cycle on incoming data streams at a high frequency (e.g., 1 Hz). This ensures a high refresh rate of situational awareness, delivering a fully reasoned output on dynamic events with a median delay, while continuously processing new information. This delay is only for the complex analysis, the YOLO detections are shown in real-time.

7.6. Computational Cost and Reliability in Time-Critical Operations

The integration of a large language model (LLM) into time-critical Search and Rescue (SAR) operations introduces valid concerns regarding latency, computational requirements, and the reliability of AI-driven reasoning. This section directly addresses these aspects, contextualizing the performance of our proof-of-concept system and outlining the architectural choices made to ensure operational viability.

- A.

Computational Cost and Architectural Choices

A key design decision was to ensure the system remains practical and deployable without reliance on extensive cloud computing infrastructure. To this end, we deliberately selected Gemma 3n E4b, an LLM specifically optimized for efficient execution on edge and low-resource devices.

While the raw parameter count of this model is 8 billion, its architecture allows it to run with a memory footprint comparable to a traditional 4B model, requiring as little as 3-4 GB of VRAM for operation. This low computational cost means the entire cognitive architecture, including all agents and the LLM orchestrator, can be hosted on a single, high-end laptop or portable GCS in the field. This approach makes the system self-contained and resilient to the loss of internet connectivity, a common issue in disaster zones.

- B.

Reliability and Mitigation of Hallucinations

The most critical concern for an LLM in a SAR context is the risk of "hallucinations" or incorrect reasoning, which could have dangerous consequences. Our architecture incorporates two primary, well-established mechanisms from AI safety research to ensure reliability.

The first mechanism is Grounding in a verifiable knowledge base. The Orchestrator Agent (OAg) does not reason in a vacuum; every critical piece of information and every logical step is validated against the structured, factual data stored in the Memory Agent (MAg), which acts as the system's verifiable "source of truth". This process anchors the LLM's reasoning in established facts, such as operational protocols and risk area maps, preventing it from generating unverified or fabricated claims and ensuring factual accuracy.

The second mechanism is a Multi-Agent Review and Self-Correction loop. As demonstrated in Scenario 2, this is a practical implementation of multi-agent review and self-reflection, which are established techniques for mitigating AI errors. The Orchestrator Agent acts as a supervisor that scrutinizes the outputs of specialized sub-agents. When it detects a logical inconsistency—such as a low-risk assessment for a high-risk situation—it does not accept the flawed output. Instead, it initiates a corrective loop, forcing the responsible agent to re-evaluate its conclusion with additional constraints. This internal validation process ensures that logical errors are caught and rectified before they can impact the final decision, significantly enhancing the system's overall reliability.

8. Discussion

It is important to note that the current validation of the system has focused on demonstrating technical feasibility and evaluating the performance of individual components and algorithms in a controlled laboratory environment. The system has not yet been tested in real disaster scenarios or with the direct involvement of emergency response personnel. Therefore, its practical usefulness, operational robustness, and acceptance by end users remain issues that require rigorous validation in the field. This stage of extensive testing, in collaboration with emergency responders and in environments simulating real disaster conditions, represents a crucial direction for future research, with the aim of optimizing the system for operational deployment and ensuring its practical relevance.

Our results demonstrate the viability of a multi-agent cognitive architecture, orchestrated by an LLM, to transform a drone from a simple sensor into a proactive partner in search and rescue missions. We were able to demonstrate the system's ability to consume multi-modal information, analyze the context and present dangers, maintain temporal persistence of information, and self-correct in scenarios where erroneous elements appeared.

Unlike previous approaches that focus on isolated tasks, such as detection optimization or autonomous flight, our system proposes and implements a practical, holistic approach. By integrating a cognitive-agentic system, we have overcome the limitations of traditional systems that only provide raw or semi-processed data streams without a well-defined context. Our system goes beyond simple detection, assessing the status of people on the ground based on external contexts and geospatial data, an essential capability that we validated in scenario 2. This reasoning ability represents a future direction for a multitude of implementations where artificial intelligence becomes a collaborator in the field.

Validation was performed by injecting synthetic data, which demonstrates the logical consistency of the cognitive architecture, but does not take into account real-world sensor noise, communication packet loss, or the visual complexity of a real disaster.

Future directions will focus on overcoming the limitations outlined above. We will seek out small rescue teams to collaborate with in the rescue process, at least from a monitoring tool perspective. This also allows us to collect data from the field in order to further refine our system, including through optimized prompts and by transforming the video stream from the field into annotated images to enrich the dataset on which we will train the next YOLO model.

We will explore and update hardware components that will reduce latency and increase the quality of the information obtained, in which we will probably install a 3D LiDAR sensor, which allows us to scan an entire region, not just the distance to the ground, a more accurate GPS, and a digital radio transmission system for instant image capture from the drone.

In terms of cognitive systems, we will explore the increase in the number of agents, which will be more specialized, and the more concrete separation of agents on a single task, from data collection to correlation and concatenation of results. We will also explore the idea of developing edge computing on a development board capable of running multiple agents simultaneously on a portable system.

9. Conclusions

This paper demonstrates a viable path toward a new paradigm in human-robot collaboration for SAR operations. By elevating the UAV from a remote sensor to an autonomous reasoning partner, our LLM-orchestrated cognitive architecture directly addresses the critical bottleneck of operator’s cognitive overload. The system's ability to autonomously synthesize, validate, and prioritize information transforms the human operator's role from a data analyst to a strategic decision maker, ultimately accelerating the delivery of aid when and where it is most needed.

The cognitive overload of human operators in search and rescue missions with drones limits their effectiveness. In this article, we presented a solution in the form of a multi-agent cognitive architecture that transforms the drone into an intelligent partner.

The central contribution of this work is the realization of a cognitive system that goes beyond the classical paradigm of the drone as a simple surveillance tool. By orchestrating a team of advanced LLM agents, we have demonstrated the ability to perform complex contextual reasoning. Unlike conventional systems, which are limited to object detection, our architecture interprets the relationships between objects and their environment (e.g., a person in proximity to a hazard), providing a semantic understanding of the scene.

A key component ensuring the robustness of the system is the feedback loop and self-correction mechanism. We have experimentally demonstrated that the system can revise and correct its initial assessments when contradictory data arise, a functionality that is essential for critical missions where a single misinterpretation can have serious consequences.

The final result of this cognitive process is translated into clear reports, ranked according to urgency, which are delivered to the human operator. This intelligent filtering mechanism transforms raw data into actionable recommendations, exponentially increasing the efficiency and speed of the decision-making process. Our synthetic tests have successfully validated the integrity of this complex architecture, confirming that each module—from perception to reasoning and reporting—works coherently to achieve the ultimate goal.

This work not only provides a specific platform for SAR operations but also paves the way for a new generation of autonomous systems capable of complex reasoning and robust collaboration with humans in critical environments. We believe that the future of artificial intelligence in robotics lies in such agentic architectures, capable of reasoning, acting, and communicating holistically.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.C.G., B.I.B. and C.U.; software, N.C.G., B.I.B. and C.U.; data curation, N.C.G., B.I.B. and C.U.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C.G., B.I.B. and C.U.; writing—review and editing, N.C.G., B.I.B. and C.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by the North-East Regional Program 2021–2027, under Investment Priority PRNE_P1 – A More Competitive, More Innovative Region, within the call for proposals Support for the Development of Innovation Capacity of SMEs through RDI Projects and Investments in SMEs, Aimed at Developing Innovative Products and Processes. The project is entitled “DIGI TOUCH NEXTGEN”, Grant No. 740/28.07.2025, SMIS Code: 338580.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sun, J.; Li, B.; Jiang, Y.; Wen, C.-y. A Camera-Based Target Detection and Positioning UAV System for Search and Rescue (SAR) Purposes. Sensors 2016, 16, 1778. [CrossRef]

- Pensieri, Maria Gaia, Mauro Garau, and Pier Matteo Barone. "Drones as an integral part of remote sensing technologies to help missing people." Drones 4.2 (2020): 15. [CrossRef]

- Ashish, Naveen, et al. "Situational awareness technologies for disaster response." Terrorism informatics: Knowledge management and data mining for homeland security. Boston, MA: Springer US, 2008. 517-544.

- Kutpanova, Zarina, et al. "Multi-UAV path planning for multiple emergency payloads delivery in natural disaster scenarios." Journal of Electronic Science and Technology 23.2 (2025): 100303. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Dae Kun, et al. "Optimising disaster response: opportunities and challenges with Uncrewed Aircraft System (UAS) technology in response to the 2020 Labour Day wildfires in Oregon, USA." International Journal of Wildland Fire 33.8 (2024). [CrossRef]

- R. Arnold, J. Jablonski, B. Abruzzo and E. Mezzacappa, "Heterogeneous UAV Multi-Role Swarming Behaviors for Search and Rescue," 2020 IEEE Conference on Cognitive and Computational Aspects of Situation Management (CogSIMA), Victoria, BC, Canada, 2020, pp. 122-128. [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, Ebtehal Turki, Shahad Saleh Alqefari, and Anis Koubaa. "Lsar: Multi-uav collaboration for search and rescue missions." Ieee Access 7 (2019): 55817-55832. [CrossRef]

- Zak, Yuval, Yisrael Parmet, and Tal Oron-Gilad. "Facilitating the work of unmanned aerial vehicle operators using artificial intelligence: an intelligent filter for command-and-control maps to reduce cognitive workload." Human Factors 65.7 (2023): 1345-1360. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Wenjuan, et al. "Unmanned aerial vehicle control interface design and cognitive workload: A constrained review and research framework." 2016 IEEE international conference on systems, man, and cybernetics (SMC). IEEE, 2016.

- Jiang, Peiyuan, et al. "A Review of Yolo algorithm developments." Procedia computer science 199 (2022): 1066-1073. [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, Ranjan, Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis, and Manoj Karkee. "UAVs Meet Agentic AI: A Multidomain Survey of Autonomous Aerial Intelligence and Agentic UAVs." arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.08045 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Jones, Brennan, Anthony Tang, and Carman Neustaedter. "RescueCASTR: Exploring Photos and Live Streaming to Support Contextual Awareness in the Wilderness Search and Rescue Command Post." Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 6.CSCW1 (2022): 1-32. [CrossRef]

- Volpi, Michele, and Vittorio Ferrari. "Semantic segmentation of urban scenes by learning local class interactions." Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops. 2015.

- Kutpanova, Zarina, et al. "Multi-UAV path planning for multiple emergency payloads delivery in natural disaster scenarios." Journal of Electronic Science and Technology 23.2 (2025): 100303. [CrossRef]

- Gaitan, N.C.; Batinas, B.I.; Ursu, C.; Crainiciuc, F.N. Integrating Artificial Intelligence into an Automated Irrigation System. Sensors 2025, 25, 1199. [CrossRef]

- M. Atif, R. Ahmad, W. Ahmad, L. Zhao and J. J. P. C. Rodrigues, "UAV-Assisted Wireless Localization for Search and Rescue," in IEEE Systems Journal, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 3261-3272, Sept. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Hayat, E. Yanmaz, T. X. Brown and C. Bettstetter, "Multi-objective UAV path planning for search and rescue," 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 2017, pp. 5569-5574. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Szirányi, T. Real-Time Human Detection and Gesture Recognition for On-Board UAV Rescue. Sensors 2021, 21, 2180. [CrossRef]

- D. Cavaliere, S. Senatore and V. Loia, "Proactive UAVs for Cognitive Contextual Awareness," in IEEE Systems Journal, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 3568-3579, Sept. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, Luttfi Ahmed, et al. "Energy consumption and efficiency degradation predictive analysis in unmanned aerial vehicle batteries using deep neural networks." Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J 19.5 (2025): 21-30. [CrossRef]

- T. Toschi et al., Evaluation of DJI Matrice 300 RTK Performance in Photogrammetric Surveys with Zenmuse P1 and L1 Sensors, ISPRS Archives, Vol. XLIII-B1-2022, pp. 339–346, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Toschi et al., Evaluation of DJI Matrice 300 RTK Performance in Photogrammetric Surveys with Zenmuse P1 and L1 Sensors, ISPRS Archives, Vol. XLIII-B1-2022, pp. 339–346, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Junbiao. "A review of the development of YOLO object detection algorithm." Appl. Comput. Eng 71.1 (2024): 39-46. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xin, et al. "Yolo-erf: lightweight object detector for uav aerial images." Multimedia Systems 29.6 (2023): 3329-3339. [CrossRef]

- Terven, Juan, Diana-Margarita Córdova-Esparza, and Julio-Alejandro Romero-González. "A comprehensive review of yolo architectures in computer vision: From yolov1 to yolov8 and yolo-nas." Machine learning and knowledge extraction 5.4 (2023): 1680-1716. [CrossRef]

- Ragab, Mohammed Gamal, et al. "A comprehensive systematic review of YOLO for medical object detection (2018 to 2023)." IEEE Access 12 (2024): 57815-57836. [CrossRef]

- NIHAL, Ragib Amin, et al. UAV-Enhanced Combination to Application: Comprehensive analysis and benchmarking of a human detection dataset for disaster scenarios. In: International Conference on Pattern Recognition. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024. p. 145-162.

- https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/kuantinglai/ntut-4k-drone-photo-dataset-for-human-detection/data.

- Zhao, Xiaoyue, et al. "Detection, tracking, and geolocation of moving vehicle from uav using monocular camera." IEEE Access 7 (2019): 101160-101170. [CrossRef]

- Mallick, Mahendra. "Geolocation using video sensor measurements." 2007 10th International Conference on Information Fusion. IEEE, 2007.

- Cai, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xia, Y.; Qiao, P.; Zhao, J. Review of Target Geo-Location Algorithms for Aerial Remote Sensing Cameras without Control Points. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12689. [CrossRef]

- Thrun, Sebastian. "Toward a framework for human-robot interaction." Human–Computer Interaction 19.1-2 (2004): 9-24.

- Brooks, Rodney A. "Intelligence without representation." Artificial intelligence 47.1-3 (1991): 139-159. [CrossRef]

- Gat, Erann, R. Peter Bonnasso, and Robin Murphy. "On three-layer architectures." Artificial intelligence and mobile robots 195 (1998): 210.