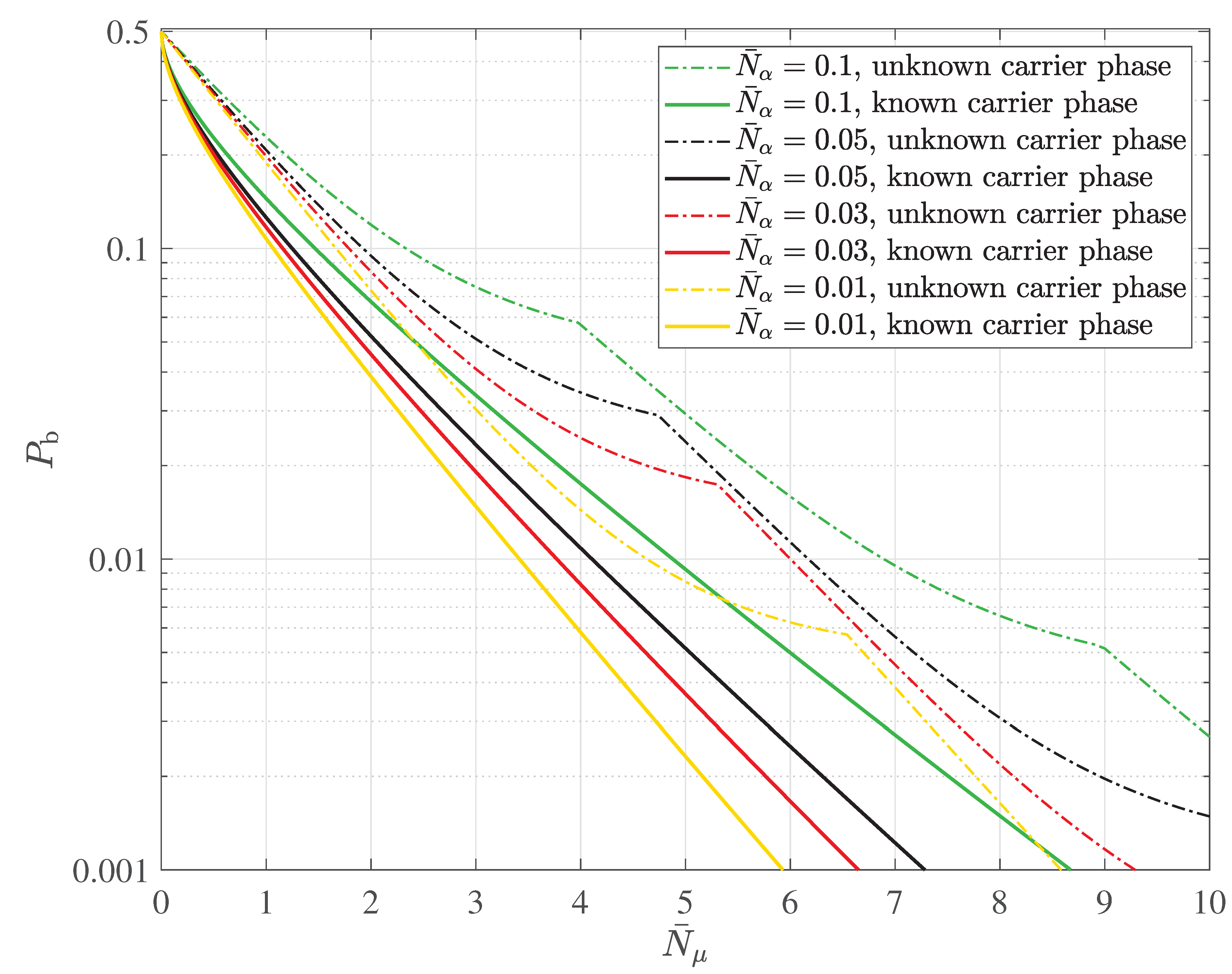

2.4. Multipath Transmission and Reception with Decoherence

In particular, scenarios involving longer transmission links often experience multipath transmission and reception. In such cases, the quantum channel is characterized by multiple paths, through which the transmitted signals arrive at the receiver. This situation has been illustrated very recently for the first time, cf. e.g. [

19,

20,

21].

Consider a quantum channel modelled as a linear multipath channel that causes uncorrelated scattering of the signal photons emitted by the laser. These scatterers are randomly located and statistically independent, forming a continuum of uncorrelated scatterers similar to what occurs in mobile propagation channels [

18,

19]. The channel impulse response (CIR) of this multipath channel, parameterized by the delay

, is denoted as

[

19]. We assume that the CIR

is nonzero only for

within the delay time interval

, where

. Under these conditions, ISI arises at the quantum receiver. Defining

the said multipath channel is referred to as a

-path channel. The signal arriving at the receiver can be expressed by the ket vector [

19]

The previously mentioned uncorrelated scattering induces decoherence [

14,

15,

16,

25], which contributes to the loss of phase coherence between the transmitter and the receiver, see e.g. [

19,

20,

21]. As a result, we should assume that no phase coherence is preserved between the transmitter and receiver [

6][p. 1590], [

9,

19][p. 171]. Consequently, the zero phase angles

appearing in the aforementioned phase factors mentioned in

Section 2.2 are considered unknown and modelled as uniformly distributed random variables with the constant probability density function of

. Moreover, the uncorrelated scattering inherent to the multipath quantum channel further contributes to the degradation of phase coherence, cf. e.g. [

19] and the references therein.

In the absence of phase coherence, the optimum quantum receiver employs photon counting at its front end [

6][p. 1590]. Assume that the transmitter and the receiver are synchronized in time, meaning that the quantum receiver operates over mutually disjoint and consecutive observation time intervals

of duration

, each beginning with the arrival of the corresponding codebit

[

19]. Using the number operator

and denoting mathematical expectation by

, the average number of signal photons

received during the observation time interval

is given by

, after averaging over all uniformly distributed phase differences

, and we obtain

Due to decoherence and averaging over

, the second integral vanishes, while the first integral remains unaffected. Therefore, equation (

19) simplifies to [

19]

which becomes

supposing that only

channel coefficients

,

, can assume nonzero values.

In the case of a single path channel where

equals 1, only the first term

of equation (

21) remains. The scenario where

equals 1 has already been discussed, for instance, in [

6, pp. 1589f] and [

9, pp. 171-176]. Moreover, if

is a nonnegative random variable with unit expected value, the result is a fading single path turbulent channel, also known as a turbulence channel, which was already investigated from a quantum communications perspective several decades ago [

26][pp. 1630-1644].

For

, the ISI term

in equation (

21) does not vanish [

19]. As a result, the average number of received signal photons

of (

21) depends not only on the current codebit

, but also on the

preceding codebits

,

…

. Therefore, equation (

21) describes a finite state machine (FSM) that operates according to a Markov chain model [

17,

19,

27].

In the context of Mealy modelling, cf. e.g. [

27], the previously described FSM consists of

states

, defined as

at each time index

. Since the term

can take on either of two distinct values, 0 or

, each of the

states

gives rise to two transitions, labelled by the hypothetical codebit value

. This results in a total of

distinct transitions, which lead to the

states

at the next time step

[

19]. The behavior of the said FSM is conveniently represented by a trellis diagram, often abbreviated as trellis [

17,

19,

28]. Accordingly, the

possible transitions correspond to the

different values that the average number of received signal photons

, as defined in (

21), can assume during each observation time interval

, with

. For this reason, we will denote

as

going forward, identifying these quantities as the

distinct hypotheses employed in the quantum data detection scheme [

19]. Note that the said hypotheses

do not necessarily match the actual number of received signal photons

observed in the

ith observation time interval [

19].

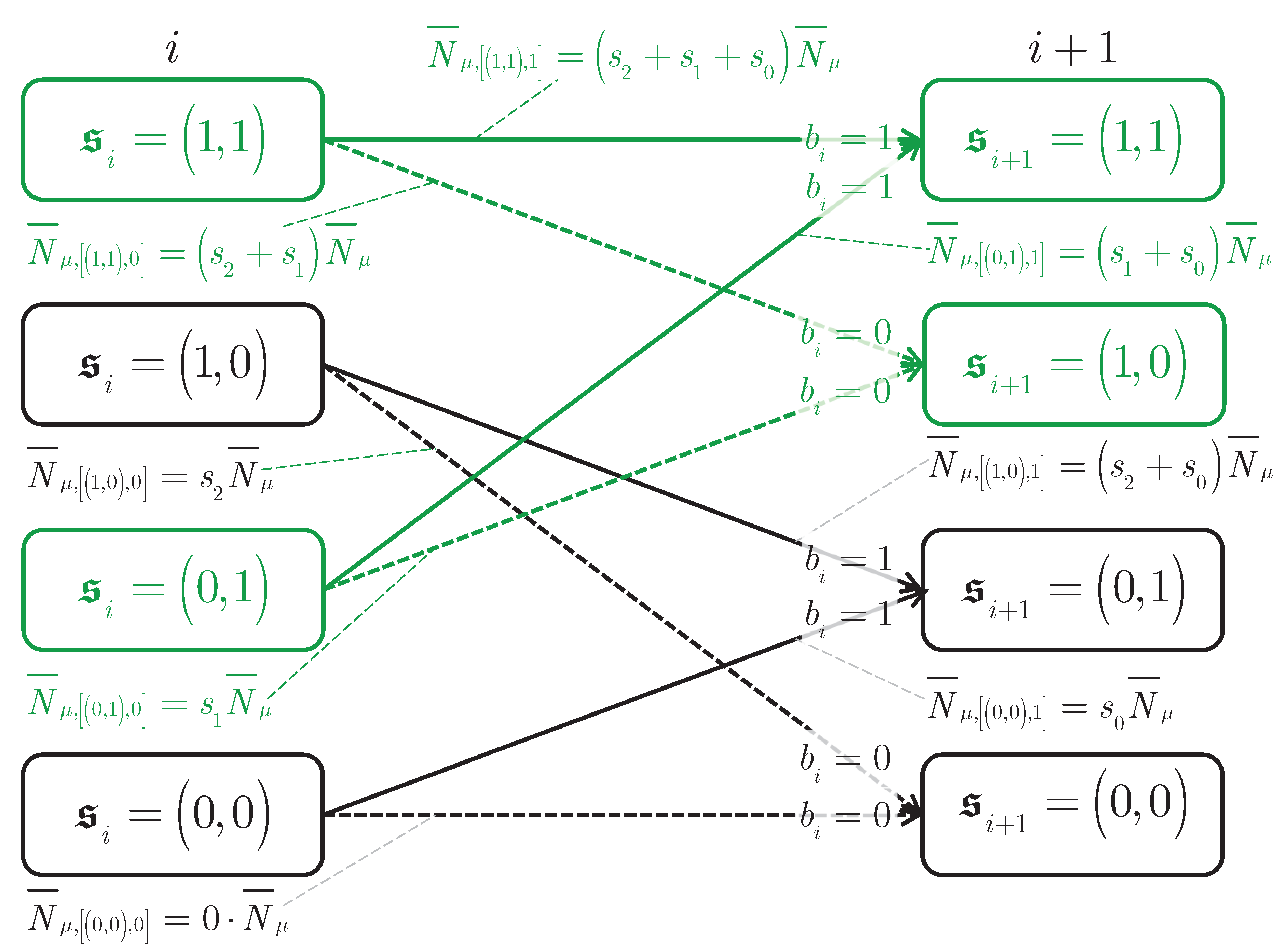

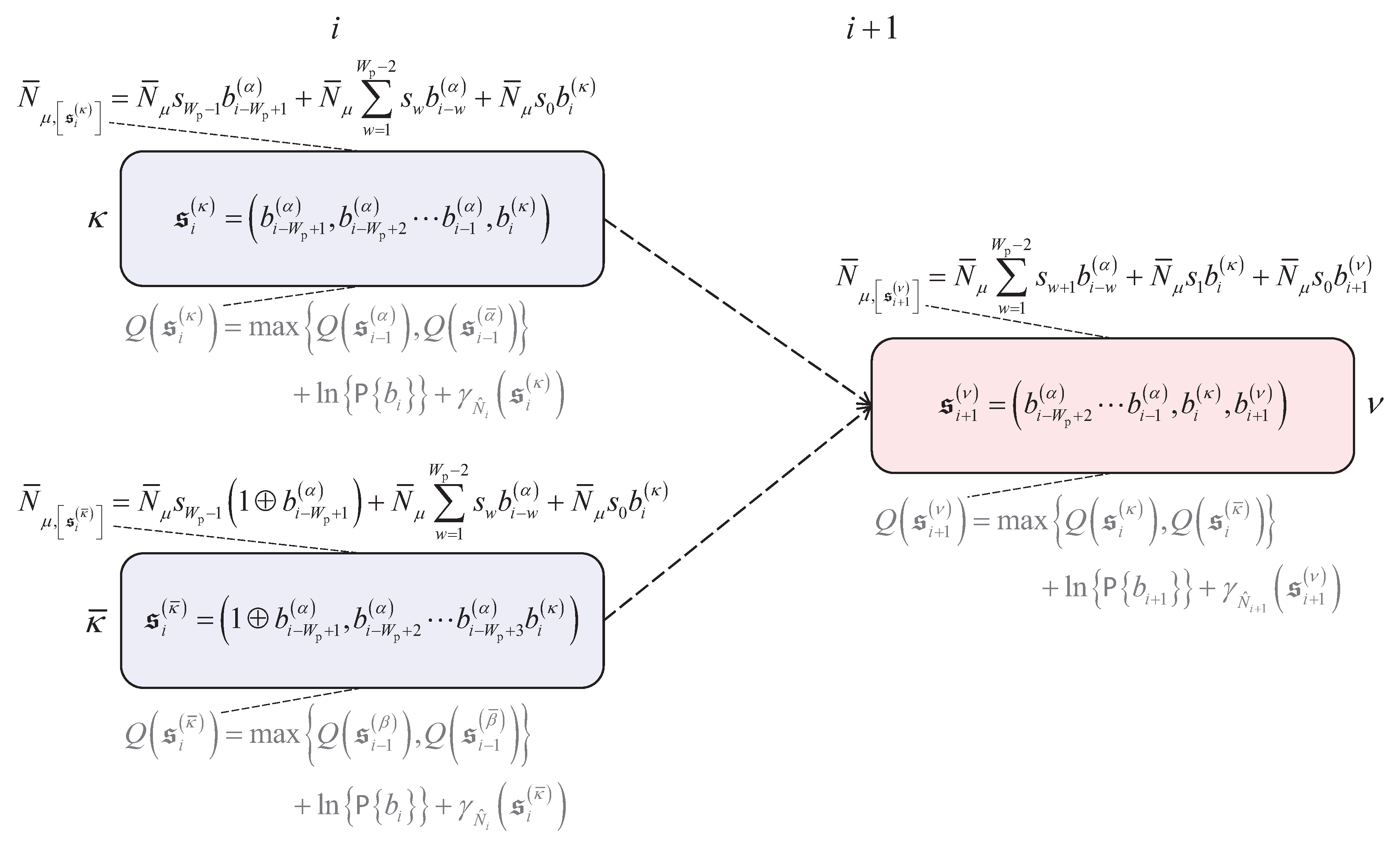

Figure 2 shows the detail of a trellis representing a quantum channel with

equal to 3 possibly nonvanishing channel coefficients

,

and

, thus, when applying Mealy modelling, having

equal to 4 states at each time instant. The two states

equal to

and

equal to

at time instant

i are connected to the two states

equal to

and

equal to

at time instant

by a total of

equal to four transitions. The said states and the aforementioned four transitions, all represented in black color, form the first of the two butterflies of the considered trellis. The two states

equal to

and

equal to

at time instant

i are connected to the two states

equal to

and

equal to

at time instant

by a total of

equal to four transitions. These states and the associated four transitions, all represented in green color, form the second of the two butterflies of the considered trellis.

Figure 2.

Detail of a trellis representing a quantum channel with equal to 3 possibly nonvanishing channel coefficients , and , thus, when applying Mealy modelling, having equal to 4 states at each time instant; the two states equal to and equal to at time instant i are connected to the two states equal to and equal to at time instant by a total of equal to four transitions, forming the first of the two butterflies; the two states equal to and equal to at time instant i are connected to the two states equal to and equal to at time instant by a total of equal to four transitions, forming the second of the two butterflies; on-off keying (OOK) is assumed.

Figure 2.

Detail of a trellis representing a quantum channel with equal to 3 possibly nonvanishing channel coefficients , and , thus, when applying Mealy modelling, having equal to 4 states at each time instant; the two states equal to and equal to at time instant i are connected to the two states equal to and equal to at time instant by a total of equal to four transitions, forming the first of the two butterflies; the two states equal to and equal to at time instant i are connected to the two states equal to and equal to at time instant by a total of equal to four transitions, forming the second of the two butterflies; on-off keying (OOK) is assumed.

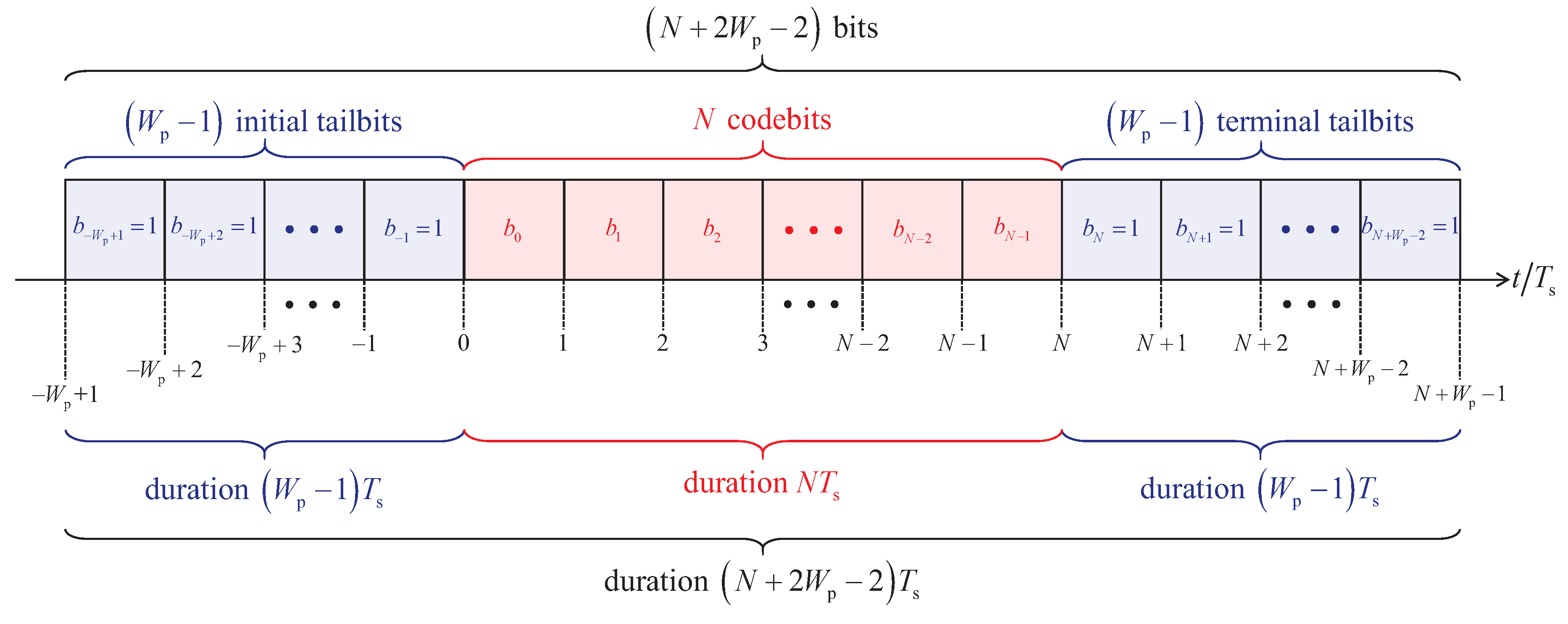

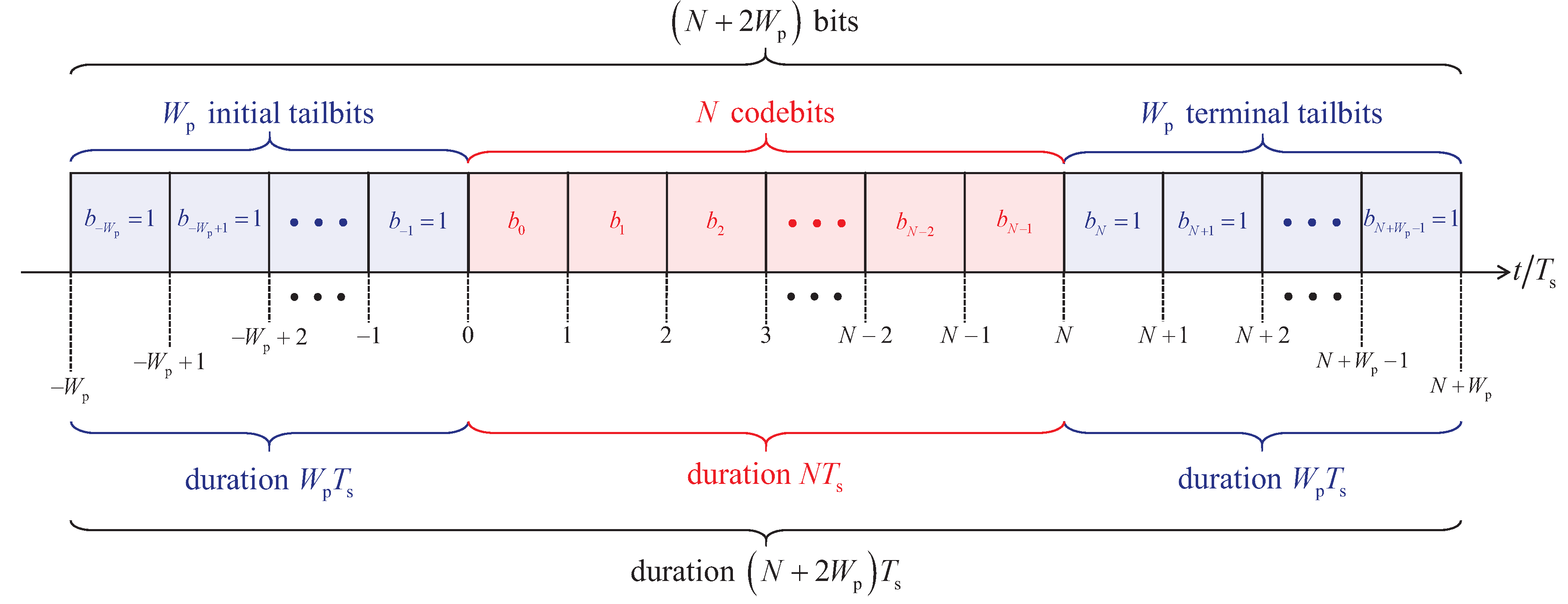

To support trellis initialization in the state equal to and trellis termination in the state equal to , a choice known to improve data detection performance, we introduce initial and terminal tailbits. Specifically, we set equal to 1 for all . All other codebits , for and , are assumed to be 0.

The schematic representation of the transmitted bit vector used when applying the trellis based quantum data detectors, which set out from the Mealy modelling of the FSM representing the multipath quantum channel, is depicted in

Figure 3. As pointed out above, the said transmitted bit vector consists of

N codebits,

initial tailbits and

terminal tailbits, hence, containing

bits.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the transmitted bit vector used when applying the trellis based quantum data detectors, which set out from the Mealy modelling of the FSM representing the multipath quantum channel; the transmitted bit vector consists of N codebits, initial tailbits and terminal tailbits, hence, containing bits.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the transmitted bit vector used when applying the trellis based quantum data detectors, which set out from the Mealy modelling of the FSM representing the multipath quantum channel; the transmitted bit vector consists of N codebits, initial tailbits and terminal tailbits, hence, containing bits.

At the output of the quantum channel, the radiation field resulting from laser emission is linearly superimposed with the omnipresent thermal background radiation field, which is in a thermal state characterized by Bose-Einstein distributed thermal noise photons. As already mentioned above,

denotes the average number of thermal noise photons and

represents the complex amplitudes of the associated coherent states present in the thermal field. The said linear superposition is modelled by the map

Given

where

is a zero phase angle, the corresponding statistical operator in Glauber’s “

P-representation” with

defined as [

9, eqs. (4.6) and (4.10), pp. 134f.]

is denoted by

during the observation time interval

,

.

Since the function

of (

24) used in (

25) is always nonnegative, the associated laser light is often referred to as “classical.” In contrast, light, for which

takes on negative values in some regions is sometimes labelled “nonclassical” [

29][p. 60]. However, this distinction may be misleading. For instance, a Fock state is entirely nonclassical by nature [

29][p. 58], and, fundamentally, all states of light are governed by quantum mechanics [

29][pp. 60, 150]. Thus, the binary classification of light as either “classical” or “nonclassical” may not be entirely appropriate. Considering that Max Planck’s treatment of thermal radiation on December 14, 1900, marked the beginning of quantum mechanics, cf. e.g. [

30][pp. 217, 277], and that laser light was theoretically introduced by Albert Einstein in 1917 on the basis of quantum principles, it seems inconsistent not to regard both thermal radiation and laser light as “nonclassical”.

With the regular Laguerre polynomial

of degree

, we find

neglecting any phase coherence, see also [

19][p. 2], [

9][pp. 136f.]. Equation (

26) is based on the assumption that the quantum receiver front-end essentially consists of a photon counting detector. This photon counting detector measures the number

of photons present at the receiver during the observation time interval

[

19]. Using the trace operation, denoted by

, and the projection operator

defined as

,

is the conditional probability of detecting

photons at the photon counting detector, given the transmission of the codeword

. Equation (

27) describes this probability as a Laguerre distribution, see also [

5, eq. (4.71), p. 174]. Notably,

coincides with the transition probability

associated with the FSM introduced earlier [

19]. It follows that equation (

27) assumes the use of an ideal photon counting detector, such as the one discussed in [

31][pp. 231f.], as the front-end component of the optimum quantum data detection scheme.

If the photon counting detector cannot precisely count the exact number of photons but is only able to differentiate among zero photons, one photon, or more than one photon, we may use

,

and

equal to

instead of

for arbitrary

[

19]. Accounting for real-world effects such as dark counts with the mathematical expectation

and quantum efficiency

, in equation (

27)

should be replaced by

and

has to be replaced by

[

19].

Based on the above discussion, the actual number of received signal photons

in the

ith observation time interval

results from a linear superposition of

Poisson distributed random variables

, each with mean

. Consequently,

itself follows a Poisson distribution [

19,

32]. It is important to note that Poisson distributed random variables are, by definition, mutually independent [

32]. Moreover, the thermal noise photons, governed by the Bose-Einstein distribution, follow a memoryless geometric distribution [

19,

32]. As a result, measurements taken across any two disjoint observation time intervals are statistically independent. This insight aligns with Forney’s classical considerations [

28].

With reference to, e.g., [

33][pp. 100-104], the likelihood function

, which denotes the conditional probability of observing the photon count vector

given the transmission of the codeword

including the terminal tailbits, is defined as follows. Let

represent the tensor product of the corresponding

statistical operators

, and

the tensor product of the associated projection measurement operators

. Then, the likelihood function is given by:

This expression reflects the joint probability of measuring the specific photon count sequence

conditioned on the transmission of the bit sequence

, via the tensor product structure of the quantum states and measurements across all observation intervals. We obtain

When the codebits

are treated as outcomes of statistically independent random experiments, the a-priori probability

of a specific codeword

including the fixed-value terminal tailbits set to 1 is given by the regular product of the individual a-priori probabilities

Applying the definition of conditional probability as found in [Def. 3.25, p. 270 [

17], the corresponding a-posteriori probability is obtained by

where

denotes the total probability of observing the photon count vector

, accounting for all possible codewords. Using the definition of the conditional probability [

17,Def. 3.25, p. 270], [

34, eq.

(5), p. 5], we yield

from (

30) after multiplying by the joint a-priori probability

of (

31).

The likelihood function

and its logarithmic counterpart

as well as the a-posteriori probability

, or its logarithmic form

constitute the foundation of the quantum data detection process that directly follows photon counting and serves to mitigate ISI [

19]. The term

is referred to as the

metric increment. In summary, optimum quantum data detection leverages either the likelihood function

, as defined in (

30), or the a-posteriori probability

, see (

33). Since classical channel decoding follows the quantum detection step, cf.

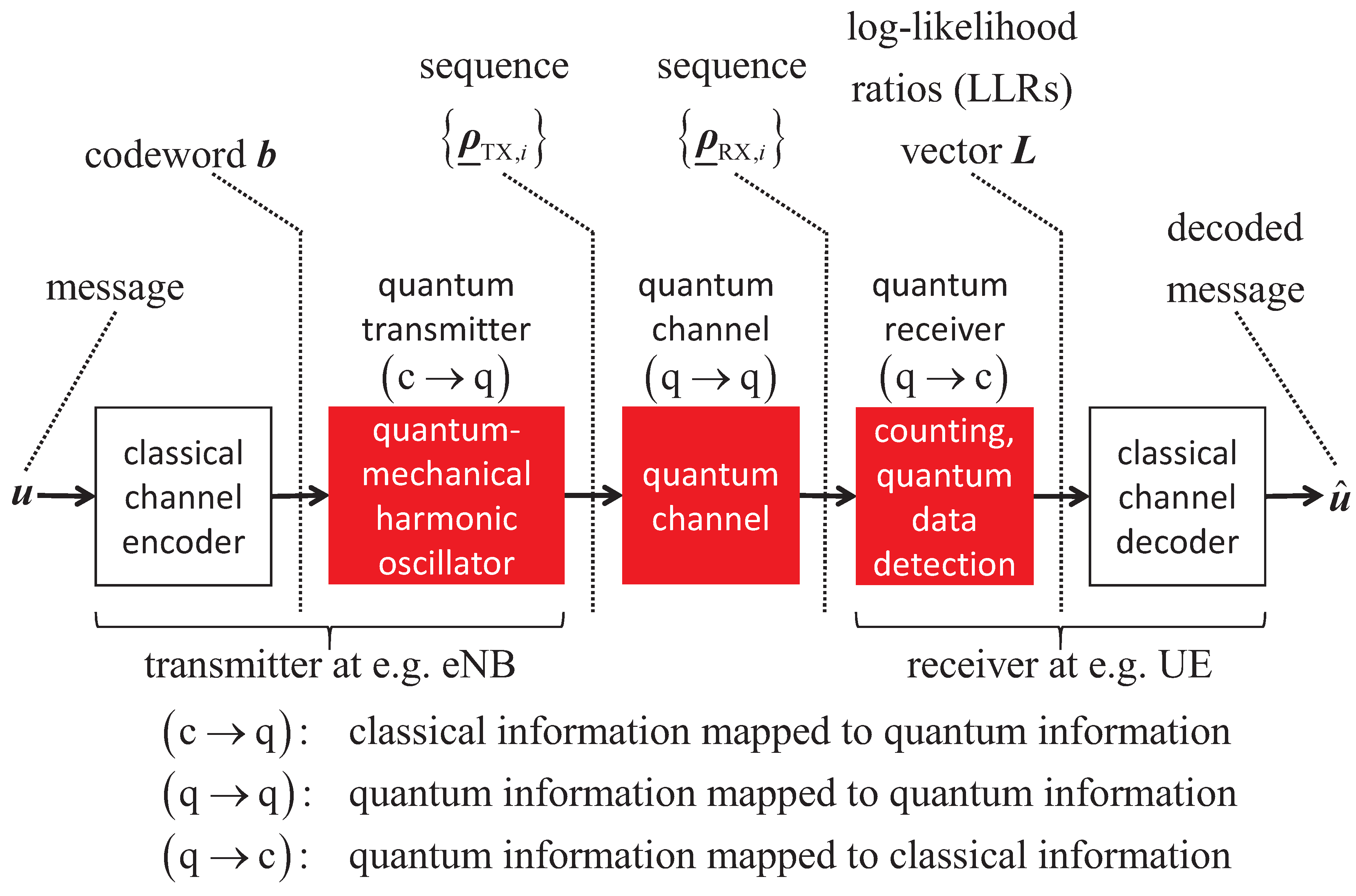

Figure 1, producing LLRs at the quantum data detector output, assembled into the LLR vector

, is advantageous.

Referring to optimum quantum data detection as first presented in e.g. [

19,

20,

21], like in

Section 2.3, we set out from the

ith observation time interval

. Again, with the Kronecker symbol

, with the cost

equal to

of the decision in favor of hypothesis

when the codebit

with value

m was transmitted,

, and with the Hermitian measurement operator

reflecting the hypothesis

, in the case of the MAP concept [

17, eq. (3.1181), p. 433] the average cost of the observational strategy in the said

ith observation time interval

is

which is a modified version of (

36), replacing

used in (

36) by

, hence taking the FSM related to the ISI into account explicitly.

Each

is diagonal in the Fock basis, with the Fock state vectors

acting as eigenkets, and the associated eigenvalues given by

, which are equal to

. As an example, consider the Hermitian detection operator in equation (

36), corresponding to

and given by

with the eigenvalues

Accordingly, the optimum measurement operators that minimize

of (

36) and are naturally realized by the ideal photon counter discussed in

Section 2 are

given by

and

given by

[

9].

At the conclusion of the measurement within the

ith observation time interval

, the exact Fock state

of the received radiation field, as present in the ideal photon counter, is known. Consequently, only the projector

within

or

contributes a nonzero eigenvalue

. This nonzero eigenvalue

is then evaluated using the conventional classical likelihood ratio test. Nonetheless, due to the presence of ISI, the decision made in the

ith observation time interval

not only depends on earlier transmitted codebits but also influences the decisions in following intervals. As a result, and as reflected in equation (

33), the classical likelihood ratio test must be modified, accordingly, taking the following form

This result is an extended variant of Helstrom’s theory [

9], as expressed in equation (

33). Hence, the optimum MAP symbol by symbol quantum data detection strategy is expressed as

cf. e.g. [

35][p. 216], being a classical likelihood ratio test, because we left the quantum regime at the end of the quantum measurement process. However, due to the occurrence of ISI, modelled by the FSM discussed above and, thus, by a Markov chain, (

40) requires an appropriate detection scheme, e.g. the trellis based Bahl-Cocke-Jelinek-Raviv (BCJR) algorithm [

17,

19,

35,

36]. It seems that this approach has been first introduced by [

19].

Correspondingly, also taking ISI and Markov chain modelling into account explicitly, with (

33), the optimum MAP sequence quantum data detection strategy is presented by

cf. e.g. [

35][p. 216], which can be implemented by the trellis based Viterbi algorithm [

17,

19,

35].

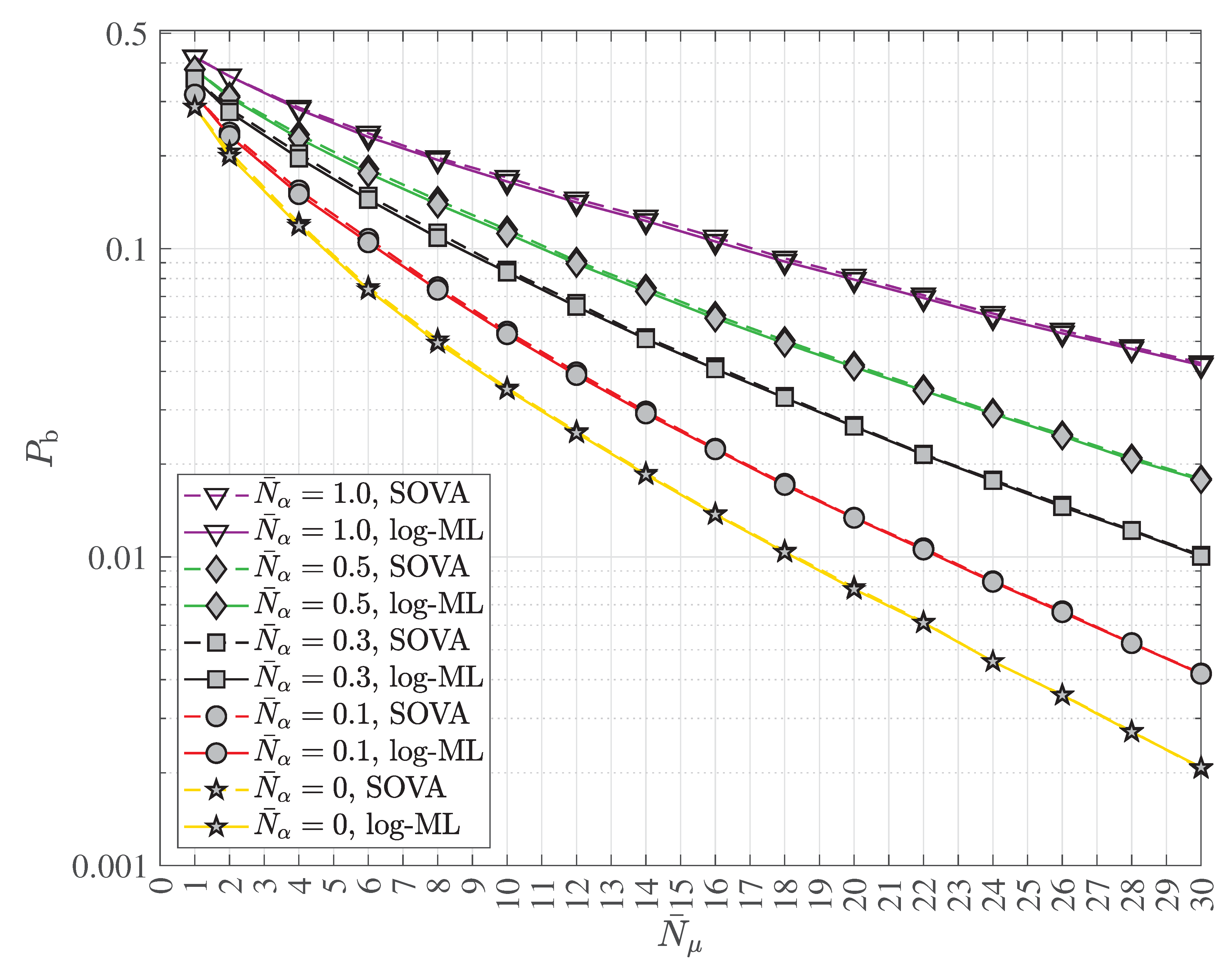

Maximizing the likelihood function

over all possibly transmitted codewords

will yield the maximum-likelihood (ML) sequence detector, which can be realized by the soft output Viterbi algorithm (SOVA) [

17,

19,

35]. Maximizing the a-posteriori probability

over all possibly transmitted codewords

will yield the MAP sequence detector. Since a-priori information is processed in the latter case, the corresponding variant of the SOVA is termed APRI-SOVA [

35,

37]. Both the SOVA and the APRI-SOVA are considered optimum because they maximize the probability of correct sequence detection, which is equivalent to minimizing the sequence error probability, provided that the metric increments discussed above are used. Details of the mode of operation of the SOVA and the APRI-SOVA have been well-known [

17,

19,

28,

35,

37].

ML symbol by symbol detection focuses on maximizing the conditional probabilities of the observed data given the symbol,

, while MAP symbol by symbol detection aims to maximize the posterior probabilities of the symbol given the observed data,

[

17,

35]. To reduce computational complexity, both detection methods are typically implemented in the log domain, similar to optimum sequence detection. Accordingly, ML symbol by symbol detection employs metric increments

, whereas MAP symbol by symbol detection uses metric increments of the form

[

17,

19]. Both approaches can be efficiently realized using the BCJR algorithm [

17,

19,

36], which is considered optimum as it maximizes the probability of correct symbol detection, equivalently, minimizing symbol error probability, when the metric increments

are used. The operational details of the BCJR algorithm are well-established, see e.g. [

17,

36]. It is important to note that optimum symbol by symbol detection schemes implemented in the log domain apply the Jacobian logarithm [

17][pp. 472f.], which leads to the so-called “log-ML” and “log-MAP” algorithms [

17][p. 479]. Approximations of the Jacobian logarithm yield variants known as “max

*-log-ML” and “max

*-log-MAP”, as well as “max-log-ML” and “max-log-MAP”, respectively [

17][pp. 472f., p. 479].

Optimum sequence quantum data detectors, as well as optimum symbol by symbol quantum data detectors, operate as “forward/backward” algorithms that conceptually consist of four key processing units. These are:

- 1.

The transition metric unit, which computes the metric increments for ML detection, or for MAP detection.

- 2.

The forward recursion unit, responsible for calculating the forward path metrics.

- 3.

The backward recursion unit, which either computes the backward path metrics or performs traceback to identify the most likely path through the trellis.

- 4.

The LLR generation unit, which produces the LLR vector mentioned earlier.

Importantly, only the computations within the transition metric unit differ from those in e.g. classical mobile radio, such as mobile radio detection. The other three units can be reused without modification.

For the SOVA and the APRI-SOVA algorithms, only approximate LLRs can be generated, using three distinct LLR computation methods known as the “SIMPLE RULE (SR)”, the “HUBER RULE (HR)”, and the “BATTAIL RULE (BR)” [

17][pp. 463-475]. In contrast, all optimum symbol by symbol quantum data detectors produce LLR vectors

containing exact LLRs when implemented as log-ML or log-MAP algorithms, and approximate, though very close to exact, LLRs in the cases of max

*-log-ML, the max

*-log-MAP, the max-log-ML and the max-log-MAP. implementations.

Trellis based reduced state quantum data detection sets out from the now well-known trellis based optimum sequence quantum data detection, respectively the trellis based optimum symbol by symbol quantum data detection discussed above. Like in the cases of these optimum data detection schemes, the reduced state quantum data detection continues until all LLRs to be determined and, consequently, all the corresponding data symbols have been detected. Trellis based reduced state quantum data detection requires small modifications and extensions of the transition metric unit and the forward recursion unit, which we will discuss in what follows. Since the said modifications and extensions only concern the transition metric unit and the forward recursion unit, which are identical in the case of the max-log-MAP symbol by symbol detection and the SOVA, the novelties presented are identically applicable to

the trellis based reduced state sequence quantum data detection, which is formed by setting out from the SOVA, termed rsSOVA with the “prefix rs” indicating the reduced state version, respectively from the APRI-SOVA, termed rsAPRI-SOVA, and

the trellis based reduced state symbol by symbol quantum data detection, which is formed by setting out from the max-log-MAP symbol by symbol detection, termed rsmax-log-MAP, the max-log-ML symbol by symbol detection, termed rsmax-log-ML, the max*>-log-MAP symbol by symbol detection, termed rsmax*-log-MAP, the max*-log-ML symbol by symbol detection, termed rsmax*-log-ML, the log-MAP symbol by symbol detection, termed rslog-MAP and the log-ML symbol by symbol detection, termed rslog-ML, the latter two differing from the max*-log-ML symbol by symbol detection and the max-log-MAP symbol by symbol detection only in the used version of Jacobi’s logarithm but not in the processing of the trellis states and the trellis transitions.

Suppose that we require reduced state quantum data detection with only

trellis states,

,

,

. Using

explicitly, (

21) can be written as follows

Reduced state data detection requires that the

binary data symbols

,

⋯

,

contained in the third term on the right side of (

42) are known to the quantum data detector prior to the

trellis transitions

. This requirement calls for preliminary decisions

,

⋯

,

needed for the transition metric computation and hence in the forward recursion. The said preliminary decisions can be accomplished by recursive processing and adds iteratively one single decision per forward recursion step. Therefore, reduced state quantum data detection requires the modification of the transition metrics computation by using

of (

42), which relies on the preliminary decided binary data symbols

,

⋯

,

and the extension of the forward recursion by adding preliminary decision taking.

In the reduced state trellis, there are

trellis transitions

, which originate at those

states

leading to the

possible forward recursion path metrics

denoting the path metric of the state

at the time instant

i. Also, there are

trellis transitions

, which originate at those

states

leading to the

possible forward recursion path metrics

,

denoting the path metric of the state at the time instant i.

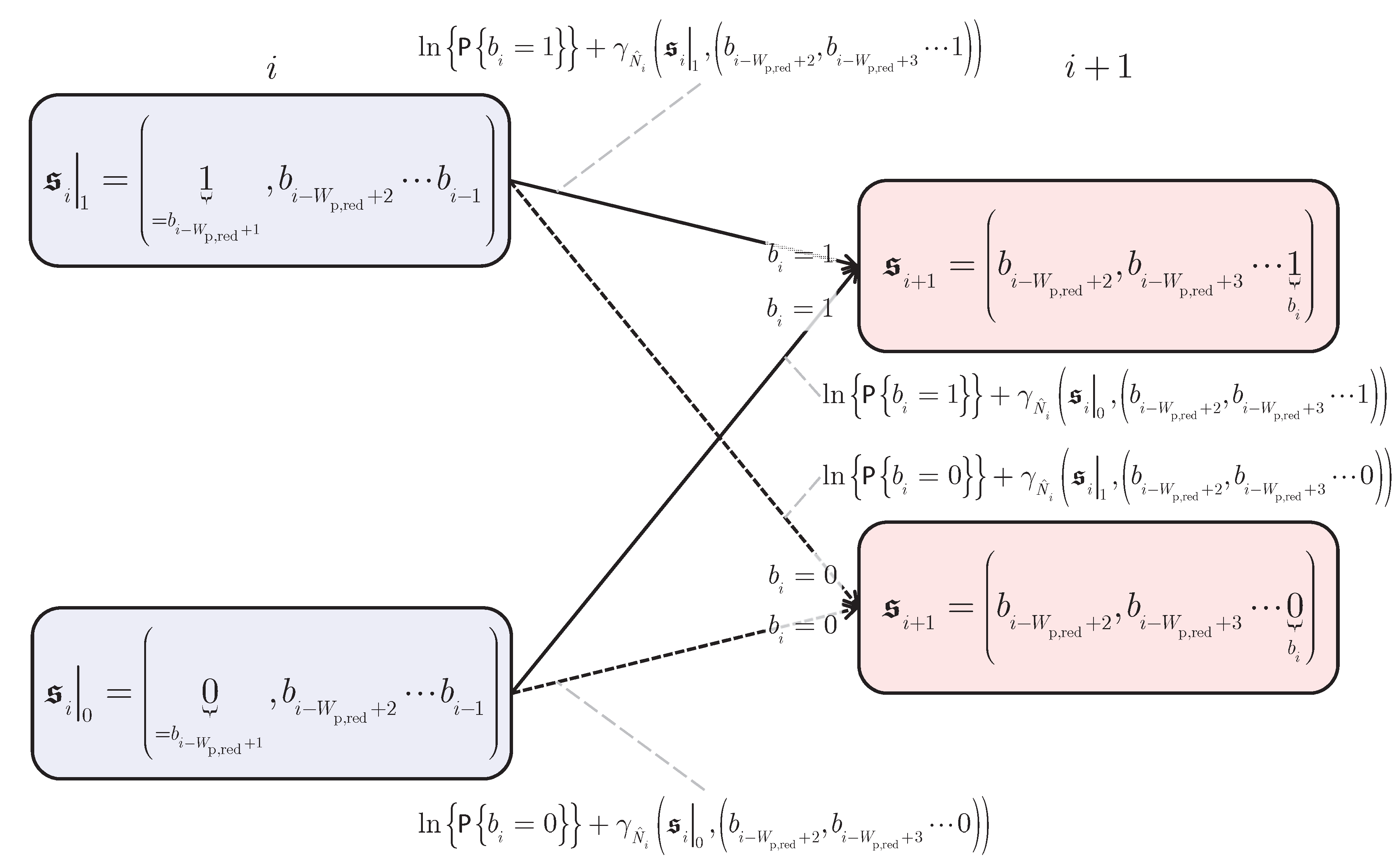

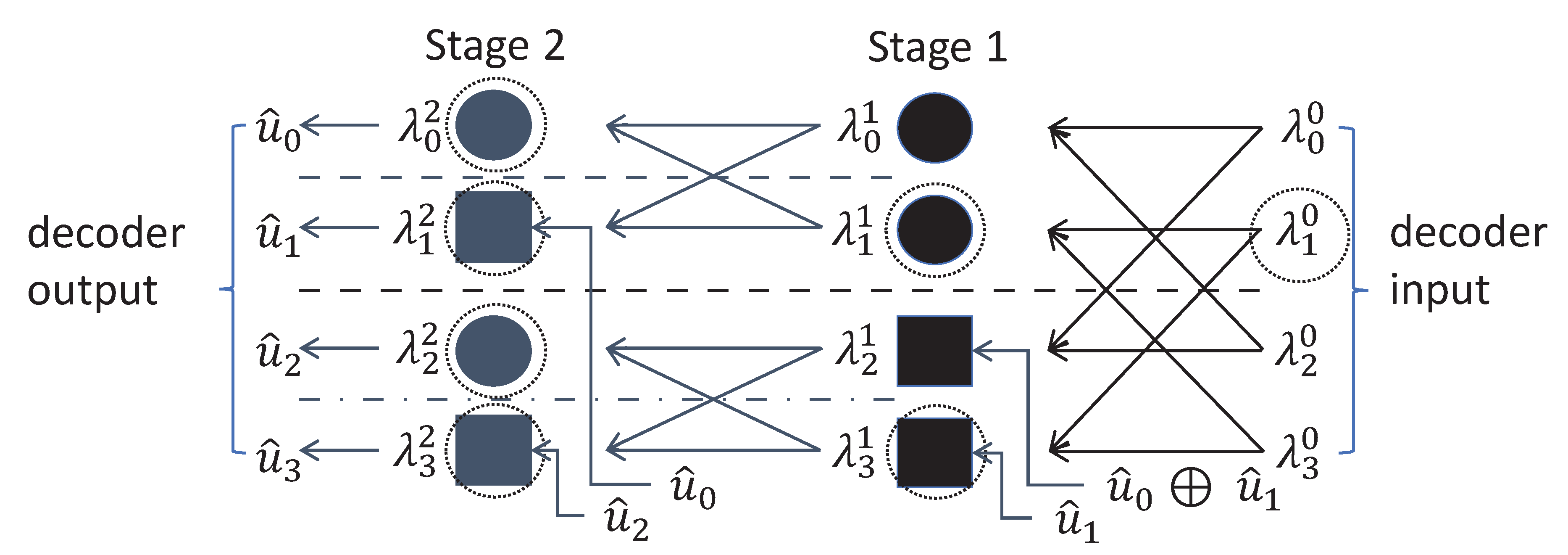

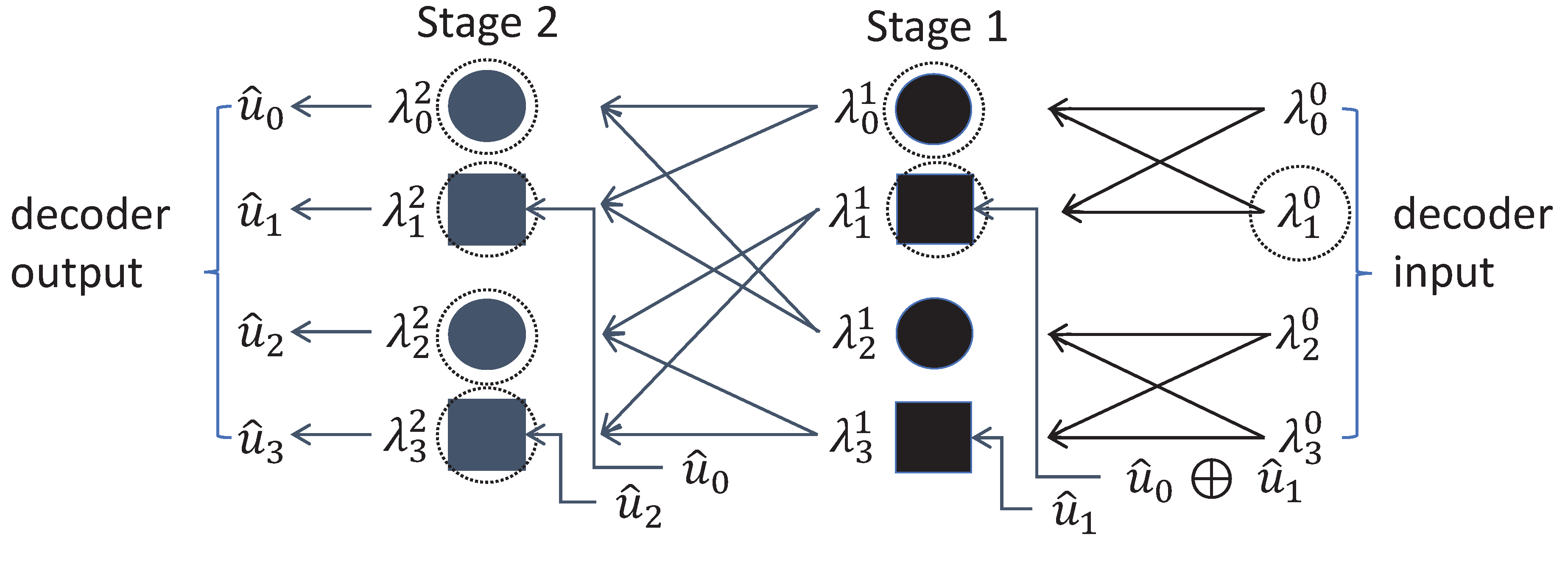

Figure 4 depicts a butterfly of the trellis with

states per time instant, considered in trellis based reduced state quantum data detection, which comprises of the two states

of (

43) and

of (

44) at the time instant

i and the two states

equal to

and

equal to

at the time instant

. The butterfly consists of two transitions originating at the state

at time instant

i and two transitions originating at the state

at time instant

i. Two of these four transitions terminate at the state

equal to

at time instant

and the remaining two of these four transitions terminate at the state

equal to

at time instant

.

Figure 4.

Butterfly of the trellis with states per time instant considered in trellis based reduced state quantum data detection; on-off keying (OOK) is assumed.

Figure 4.

Butterfly of the trellis with states per time instant considered in trellis based reduced state quantum data detection; on-off keying (OOK) is assumed.

When summing up all the above-mentioned possible forward recursion path metrics by iteratively applying Jacobi’s logarithm, we yield the forward recursion estimate of the logarithmic probability . Next, when summing up all the possible forward recursion path metrics by iteratively applying Jacobi’s logarithm, we yield the forward recursion estimate of the logarithmic probability . Subtracting from yields the forward recursion LLR of , which is to be used for the preliminary decision . Since we now have the viable decision , we may continue with the next iteration step in the forward recursion.

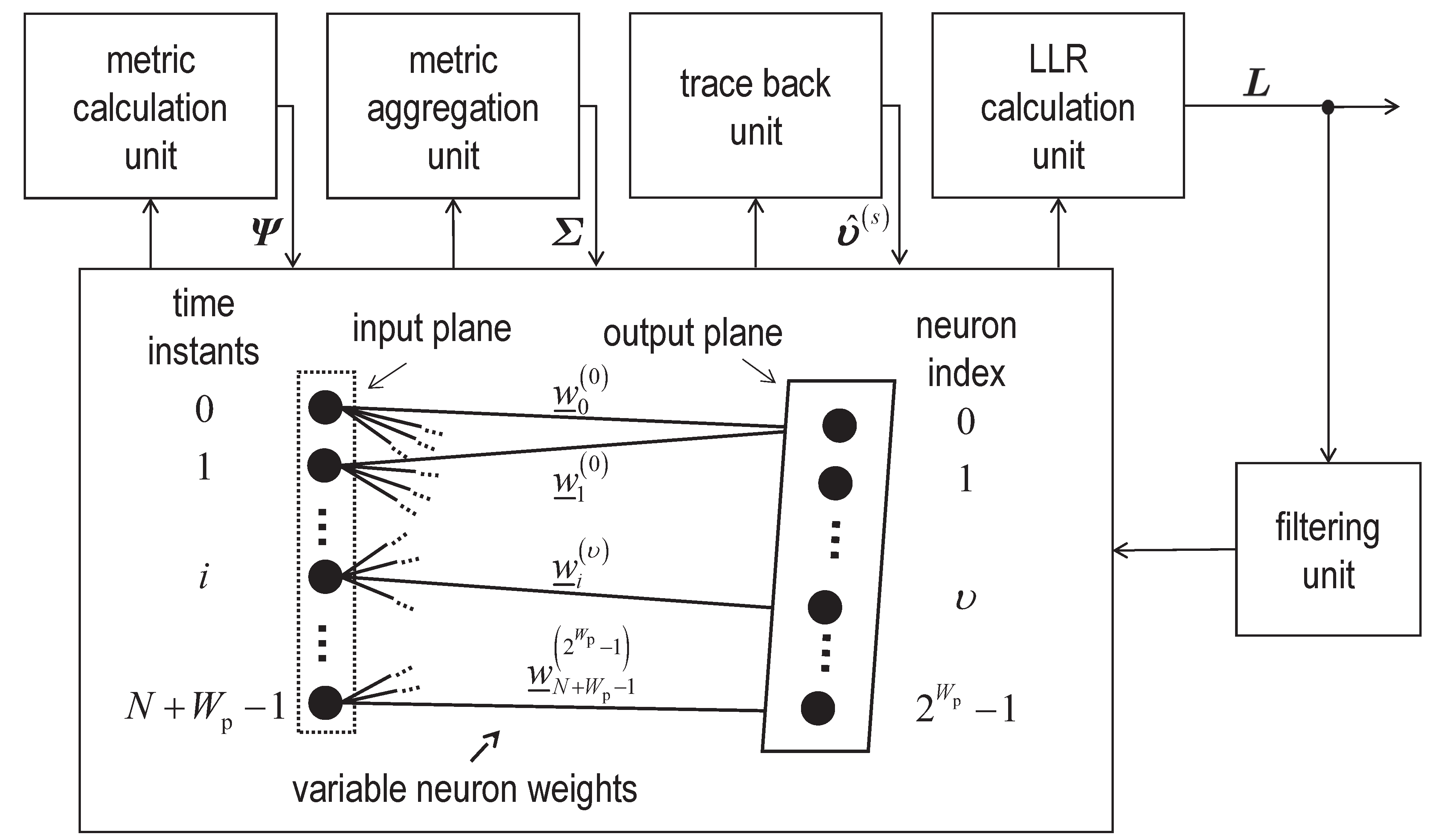

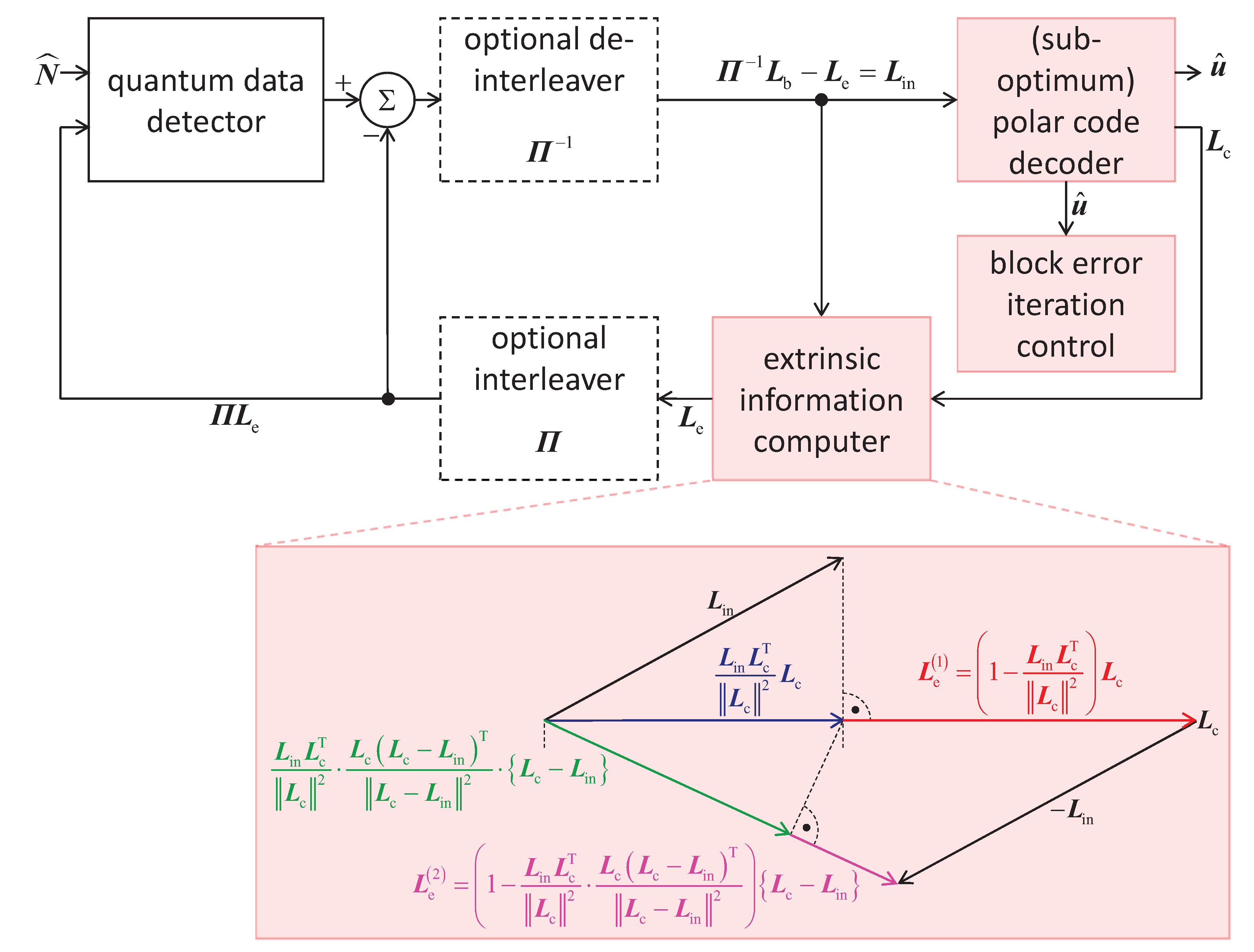

Figure 5.

System design of the Kohonen maps based detector employing a neural network using variable neuron weights, cf. e.g. [

22][Fig. 1].

Figure 5.

System design of the Kohonen maps based detector employing a neural network using variable neuron weights, cf. e.g. [

22][Fig. 1].

While state reduction is an advantageous strategy for managing detection complexity,

Kohonen maps can be employed for resource-efficient implementations, and near optimum performance in classical mobile communication systems [

22]. The Kohonen maps based sequence detector, also referred to as “Kohonen maps based detector” or “Kohonen detector”, is also applicable to quantum channels. It consists of four processing units, namely the

metric calculation unit, the

metric aggregation unit, the

trace back unit and the

LLR calculation unit [

22]. The combination of these four units follows the signal processing principle of a APRI-SOVA by applying a neural network with a one-dimensional linear structure in both the input plane and the output plane using distinct features of the Kohonen map by appropriately adjusting the weights and the distance function [

22]. More specifically, the neural network adopted by the Kohonen maps based detector is a hybrid of learning vector quantization (LVQ) and Kohonen maps, both belonging to the family of soft competitive learning clustering algorithms [

38]. This approach enables leveraging neural networks to perform near optimum sequence detection by efficiently utilizing existing hardware resources [

22]. Training the Kohonen map by incorporating LLR feedback has been shown to improve the overall performance of the Kohonen maps based detector [

22].

In order for the Kohonen maps based detector to be applied in quantum communication channels, the aforementioned FSM has to be modelled by means of a Moore machine. In the case of Moore modelling, the FSM contains unique states equal to at each time instant . For this reason, we will use initial and terminal tailbits, setting equal to 1 for all .

The schematic representation of the transmitted bit vector used when applying the Kohonen map based quantum data detector, which sets out from the Moore modelling of the FSM representing the multipath quantum channel, is shown in

Figure 6. As pointed out above, the said transmitted bit vector consists of

N codebits,

initial tailbits and

terminal tailbits, hence, containing

bits.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the transmitted bit vector, used when applying the Kohonen map based quantum data detector, which sets out from the Moore modelling of the FSM representing the multipath quantum channel; the transmitted bit vector consists of N codebits, initial tailbits and terminal tailbits, hence, containing bits.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the transmitted bit vector, used when applying the Kohonen map based quantum data detector, which sets out from the Moore modelling of the FSM representing the multipath quantum channel; the transmitted bit vector consists of N codebits, initial tailbits and terminal tailbits, hence, containing bits.

Each possible state at a given time instant

i is associated with a state number, i.e. a state index

. Interpreting the FSM as a Moore machine involves a doubling of the number of states and a reinterpretation of the transition metrics, as they no longer depend on transitions, i.e., both the initial states and the target states, but solely on the target states. We further denote the set of possible states in the Mealy case by

and the corresponding set in the Moore case by

. The remodelling as a Moore machine necessitates the introduction of a mapping function in order to assign the previously determined transition metrics

, for the Mealy case to transition metrics for the Moore case

, respectively,

,

. We define a surjective mapping

to assign the transition of a Mealy state pair to a Moore state. For each

the mapping is defined as

where

denotes the floor function (in German “Gaußklammer”). Furthermore,

denotes the state index of the initial state and

the state index of the target state in the case of Mealy modelling.

Once the transition metrics according to Moore modelling are obtained and summarized in a

matrix

, the Kohonen detector operates similarly to the case of classical wireless communication systems. At this stage, the Kohonen map serves as a state mapper allowing for an adequate add-compare-select (ACS) operation for the permissible state transitions [

22]. In what follows,

denotes a possible predecessor state with its state index

at the time instant

i of the successor state

with state index

at the time instant

. The output neuron for the state

with state number

at the time instant

is configured with the weight vector

using

where

denotes the path metric of the state with state number

at the time instant

i. Any state

can be reached by two distinct predecessors,

and

say. In order to determine the path metrics at the time instant

for each possible successor state

, solely the weights of the Kohonen map must be examined. We obtain

which can be arranged in the

path metrics row vectors

We will illustrate the above discussions of the soft output Kohonen maps based quantum data detection in what follows. Let the states with the state indices

and

refer to the predecessor states at time instant

of the state

with the state index

at time instant

i. Furthermore, let the state indices

and

refer to the predecessor states at time instant

of the state

with the state index

at time instant

i. As shown in

Figure 7, the state

with the state index

,

,

…

and

denoting the particular bit values associated with this state

, and the state

with the state index

,

,

…

and

denoting the particular bit values associated with the state

, are the predecessor states at time instant

i of the state

with the state index

at time instant

. The aforementioned states

of (

51),

of (

52) and

of (

53) are part of the trellis representing the multipath quantum channel with

possibly nonvanishing channel coefficients

,

, setting out from the Moore modelling applied in the soft output Kohonen maps based quantum data detector. In

Figure 7, the average numbers

and

of signal photons at the photon counter are associated with the appropriate states. Also, the recursive computation of the path metrics

by the soft output Kohonen map based quantum data detector is also illustrated.

The calculated path metrics are arranged in the

matrix

for further processing. The optimum path is found in the trace back unit by again utilizing the Kohonen map as a state mapper, yet in a reverse-oriented manner. The weights of the neurons representing the possible predecessor states

are configured with

Denoting the state index of the survivor state at time instant

by

, its predecessor state is found according to

The remaining predecessor states can be determined recursively. All predecessors along the survivor path can be arranged in the vector

of length

. Similarly to the case of SOVA, respectively the APRI-SOVA, approximate LLRs can be generated using the Kohonen detector [

22].

Owing to its simplicity and promising performance, the authors choose to begin with the aforementioned “SIMPLE RULE” (SR). According to the SR, approximate LLRs are built based on the path metric differences of the survivor and concurrent predecessor states [p. 466 [

17, p. 466]. In the case of Moore modelling of the FSM, the path metric difference at time instant

is given by

where

denotes the path metric of the concurrent predecessor at time instant

i. The structure of the Kohonen map employed in the generation of LLRs mirrors that of the trace back unit, with the sole modification being the inversion of the sign of the concurrent predecessor state’s path metric and the insertion of zeros instead of

for impermissible state transitions, i.e.

The path metric difference

represents the distinct metric deviation that allows to distinguish between whether the FSM was in the predecessor state

or in the concurrent predecessor state

. Due to the structure of FSM modelling and the influence of ISI, these two states differ by only a single symbol, specifically, the one at time instant

. Therefore, the path metric difference is interpreted as a reliability measure for that particular symbol at time instant

. The LLRs are found recursively using

The updates according to the “HUBER RULE” (HR) and the “BATTAIL RULE” (BR) can be performed in accordance with [pp. 469, 474 [

17, pp. 469, 474].

In order to improve the adaptability of the Kohonen map based detector, a novel updating procedure was also introduced, where, instead of investigating spatial distribution of FSM states, a probability based neighborhood function is calculated [

22]. These probabilites are calculated based on the LLRs, which can be filtered and fed back in order to update the Kohonen map. Since Kohonen maps follow a “winner takes most” approach, not only the weights of the winning output neuron are updated, but also those within a defined “winning neighborhood”

. The probability of each state

at each time instant

is governed by the a-priori probabilities of the

most recently received codebits, which are supposed to be

mutually independent. It is thus obtained by

Given the state probability (66) and the probability threshold

, which must be exceeded if the weights of a neuron shall be updated, the neighborhood of the winning output neuron is given by

[

22]. This purely local perspective can be improved by using a “forward/backward” approach to obtain the optimum state probabilities.

By combining two megatrends, namely artificial intelligence and quantum communications, soft output quantum data detectors using Kohonen maps may provide low-complexity, high-performance detection methods that enhance the scalability and efficiency of next-generation communication networks.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the connections between the states and with the state indices and at the time instant i with the state with the state index at the time instant , which are part of the trellis representing the multipath quantum channel with possibly nonvanishing channel coefficients , , setting out from the Moore modelling applied in the soft output Kohonen maps based quantum data detector; the average numbers , and of signal photons at the photon counter are associated with the appropriate states; also, the recursive computation of the path metrics , and by the soft output Kohonen map based quantum data detector is also illustrated.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the connections between the states and with the state indices and at the time instant i with the state with the state index at the time instant , which are part of the trellis representing the multipath quantum channel with possibly nonvanishing channel coefficients , , setting out from the Moore modelling applied in the soft output Kohonen maps based quantum data detector; the average numbers , and of signal photons at the photon counter are associated with the appropriate states; also, the recursive computation of the path metrics , and by the soft output Kohonen map based quantum data detector is also illustrated.