Submitted:

17 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Source and Variables

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Clinical Findings in Survivors and Nonsurvivors

3.3. Laboratory Findings in Survivors and Nonsurvivors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DLRG:Statistik Ertrinken. 2024. Available online: https://www.dlrg.de (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Szpilman, D.; Bierens, J.J.; Handley, A.J.; Orlowski, J.P. Drowning. New Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2102–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichhorn, L.; Leyk, D. Diving Medicine in Clinical Practice. Dtsch. Aerzteblatt Online 2015, 112, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VDST: Unfallanalyse. 2018. Available online: https://www.vdst.de (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Ceglarek, U.; Schellong, P.; Rosolowski, M.; Scholz, M.; Willenberg, A.; Kratzsch, J.; Zeymer, U.; Fuernau, G.; de Waha-Thiele, S.; Büttner, P.; et al. The novel cystatin C, lactate, interleukin-6, and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (CLIP)-based mortality risk score in cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Hear. J. 2021, 42, 2344–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M; et al. Öffentlicher Jahresbericht 2023 des Deutschen Reanimationsregisters: Außerklinische Reanimation 2023. 10 May 2024. Available online: www.reanimationsregister.de/berichte.html (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Böttcher, F; et al. Tödlicher Tauchunfall. In Der Anaesthesist; Springer: Berlin, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guillén-Pino, F.; Morera-Fumero, A.; Henry-Benítez, M.; Alonso-Lasheras, E.; Abreu-González, P.; Medina-Arana, V. Descriptive study of diving injuries in the Canary Islands from 2008 to 2017. Diving Hyperb. Med. J. 2019, 49, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasenjäger M, Burchert H Statistische Erfassung von Ertrinkungsnotfällen in Deutschland. Präv Gesundheitsf. 2014, 9, 305–311. [CrossRef]

- Jüttner, B.; Wölfel, C.; Camponovo, C.; Schöppenthau, H.; Meyne, J.; Wohlrab, C.; Werr, H.; Klein, T.; Schmeißer, G.; Theiß, K.; et al. S2K guideline for diving accidents. Ger. Med. Sci. 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarozzi, I.; Franceschetti, L.; Simonini, G.; Raddi, S.; Machado, D.; Bugelli, V. Black box of diving accidents: Contribution of forensic underwater experts to three fatal cases. Forensic Sci. Int. 2023, 346, 111642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzacott, P.L. The epidemiology of injury in scuba diving. Med Sport Sci. 2012, 58, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesús, J.M.; Aguirre, F.; Carrera, A.; Boadas-Vaello, P.; Serrando, M.T.; Reina, F. Diving-related fatalities: multidisciplinary, experience-based investigation. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2019, 15, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzold, A.; Schlote, J.; Gries, A.; Dreßler, J. Fatal Diving Accidents in East Germany. J Forensic Sci & Criminal Inves. 2024, 18, 555989. [Google Scholar]

- Gries, A. Notfallmanagement bei Beinahe-Ertrinken und akzidenteller Hypothermie. Der Anaesthesist 2001, 50, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torabi, M.; Abadi, F.M.S.; Baneshi, M.R. Blood sugar changes and hospital mortality in multiple trauma. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 36, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.; Urban, N.; Döll, S.; Hartwig, T.; Yahiaoui-Doktor, M.; Burkhardt, R.; Petros, S.; Gries, A.; Bernhard, M. Early Lactate Dynamics in Critically Ill Non-Traumatic Patients in a Resuscitation Room of a German Emergency Department (OBSERvE-Lactate-Study). J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 56, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, J.A.; Madias, N.E.; Ingelfinger, J.R. Lactic Acidosis. New Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2309–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenger, A.K.; Jaffe, A.S. Requiem for a heavyweight: the demise of creatine kinase-MB. Circulation 2008, 118, 2200–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servonnet, A; et al. Y a-t-il un intérêt au dosage de la myoglobine en 2017? [Myoglobin: still a useful biomarker in 2017?]. Ann Biol Clin. 2018, 76, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, F.S.; Tipton, M.J.; Scott, R.C. Immersion, near-drowning and drowning. Br. J. Anaesth. 1997, 79, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.-L.; e Silva, A.Q.; Couto, L.; Taccone, F.S. The value of blood lactate kinetics in critically ill patients: a systematic review. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Board of Internal Medicine: ABIM Laboratory Test Reference Ranges. 14 April. Available online: https://www.abim.org (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Guy, A.; Kawano, T.; Besserer, F.; Scheuermeyer, F.; Kanji, H.D.; Christenson, J.; Grunau, B. The relationship between no-flow interval and survival with favourable neurological outcome in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Implications for outcomes and ECPR eligibility. Resuscitation 2020, 155, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevathasan, T.; Gregers, E.; Mørk, S.R.; Degbeon, S.; Linde, L.; Andreasen, J.B.; Smerup, M.; Møller, J.E.; Hassager, C.; Laugesen, H.; et al. Lactate and lactate clearance as predictors of one-year survival in extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation – An international, multicentre cohort study. Resuscitation 2024, 198, 110149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myat, A.; Song, K.-J.; Rea, T. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: current concepts. Lancet 2018, 391, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, Y. No association of CPR duration with long-term survival. Resuscitation 2022, 182, 109677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohlin, O.; Taeri, T.; Netzereab, S.; Ullemark, E.; Djärv, T. Duration of CPR and impact on 30-day survival after ROSC for in-hospital cardiac arrest—A Swedish cohort study. Resuscitation 2018, 132, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, N.; Kokubu, N.; Nagano, N.; Nishida, J.; Nishikawa, R.; Nakata, J.; Suzuki, Y.; Tsuchihashi, K.; Narimatsu, E.; Miura, T. Prognostic Impact of No-Flow Time on 30-Day Neurological Outcomes in Patients With Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Who Received Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Circ. J. 2020, 84, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, G.D.; Callaway, C.W.; Haywood, K.; Neumar, R.W.; Lilja, G.; Rowland, M.J.; Sawyer, K.N.; Skrifvars, M.B.; Nolan, J.P. Brain injury after cardiac arrest. Lancet 2021, 398, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suominen, P.K.; E Korpela, R.; Silfvast, T.G.; Olkkola, K.T. Does water temperature affect outcome of nearly drowned children. Resuscitation 1997, 35, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhail, J. The trauma triad of death: hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy. AACN Clin Issues 1999, 10, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, D.N.; Arcinue, E.L.; Peek, C.; Kraus, J.F. Effect of Immediate Resuscitation on Children with Submersion Injury. Pediatrics 1994, 94, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Wentz, K.R.; Gore, E.J.; Copass, M.K. Outcome and Predictors of Outcome in Pediatric Submersion Victims Receiving Prehospital Care in King County, Washington. Pediatrics 1990, 86, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, G.; Jennett, B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 1974, 2, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.J.; Liao, C.J.; Kabir, C.; Hallak, O.; Samee, M.; Potts, S.; Klein, L.W. Etiology and Determinants of In-Hospital Survival in Patients Resuscitated After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in an Urban Medical Center. Am. J. Cardiol. 2020, 130, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldırım, S.; Varışlı, B. The effects of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) performed out-of-hospital and in-hospital with manual or automatic device methods and laboratory parameters on survival of patients with cardiac arrest. Ir. J. Med Sci. (1971-) 2023, 192, 2365–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient characteristics | Age [yrs] | Sex [m/f] | Survival [yes/no] | Drowning / Diving accident |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical parameters on admission | Initial body temperature [°C] (36 - 37)1 |

CPR2 duration [≤ 10 min / >10 min] | No-flow time3 [≤ 5 min / >5 min] | Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)4 (3-15) |

| Laboratory parameters on admission | Lactate [mmol/l] (0.5 - 2.2) |

pH value (7.36 - 7.44) |

Blood sugar [mmol/l] (4.0 - 7.8) |

Heart enzymes [troponin in pg/ml (<14), CK-MB quotient in % (<6), myoglobin in µg/l (28 – 72)] |

| Parameter | Survivor | Nonsurvivor | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 10 | 15 | |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Case [drowning/diving] | 6/4 | 13/2 | 0.175 |

| Sex [m/f] | 7/3 | 10/5 | 1.000 |

| Age [yrs] | 51.6±22.2 | 47.8±20.0 | 0.660 |

| Clinical findings | |||

|

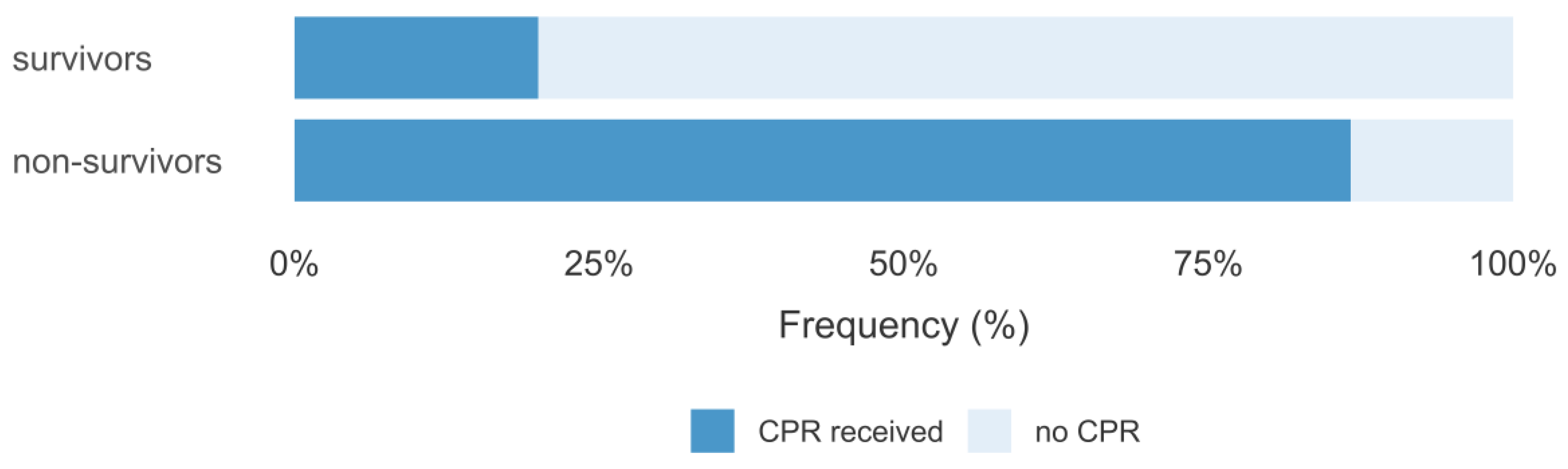

CPR [yes/no] If yes: CPR duration [≤10 min, >10 min] No-flow time [≤5 min, >5 min] |

2/8 2/0 2/0 |

13/2 2/11 4/8 |

0.002 n.a. n.a. |

| Body temperature [°C] | 36.1±1.0 | 33.5±3.4 | 0.100 |

|

GCS GCS ≤ 8 GCS 9-12 GCS ≥ 13 |

3 0 7 |

15 0 0 |

<0.001 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

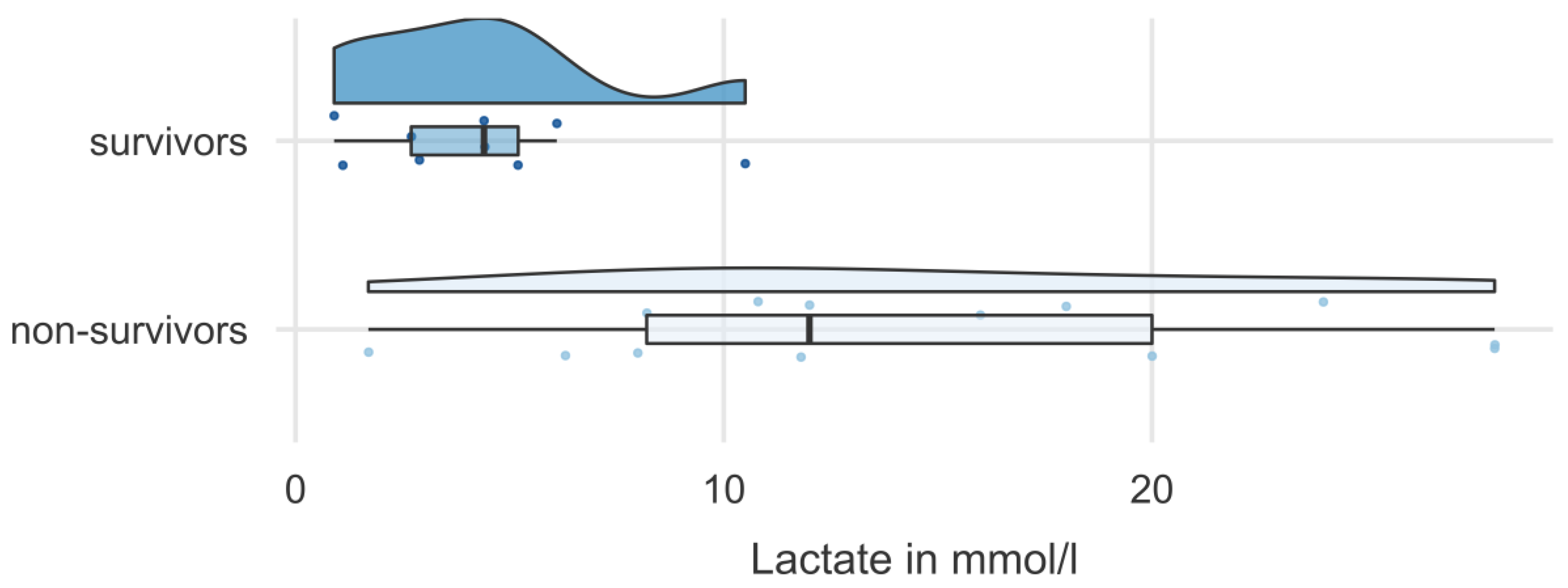

| Lactate [mmol/l] | 4.3±2.9 | 14.8±8.4 | 0.002 |

| pH | 7.4±0.1 | 6.7±0.3 | <0.001 |

| CK-MB quotient [%] | 9.7±4.5 | 51.8±20.5 | <0.001 |

| Myoglobin [µg/l] | 188.9±190.4 | 1930.9±1977.4 | <0.001 |

| Troponin [pg/ml] | 19.2±12.9 | 67.7±70.6 | 0.076 |

| Blood sugar [mmol/l] | 6.6±1.4 | 14.3±4.1 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).