1. Introduction

Corporate misconduct, whether manifested in the form of financial fraud or in the more recent emergence of environmental, social, and governance (ESG)-washing, continues to pose a significant threat to the credibility and stability of global markets. Such practices undermine the reliability of corporate disclosures, distort the allocation of resources, and weaken the relationship of trust between corporations, investors, and the wider public. While financial fraud has a long-documented history, with cases spanning from early market speculation to modern-day accounting scandals, ESG-washing represents a contemporary but equally pressing risk to market integrity [

1,

2]. Both practices share a common reliance on exploiting information asymmetries and deficiencies in monitoring systems, allowing the projection of compliance and ethical behaviour without the corresponding substantive action [

3].

Over the past two decades, the rapid growth of ESG-focused investment has reshaped expectations for corporate accountability and transparency. Policymakers, investors, and civil society actors increasingly demand robust sustainability reporting, recognising its capacity to capture material non-financial risks and opportunities that conventional accounting systems may overlook [

4,

5]. In principle, high-quality ESG reporting should empower stakeholders to make more informed decisions, align capital flows with sustainable business practices, and enhance long-term value creation. However, in practice, the coexistence of voluntary disclosure regimes and fragmented global reporting standards has left considerable room for selective, and at times misleading, communication of ESG performance [

6]. In this context, ESG-washing has emerged as a reputational and financial hazard, capable of influencing investor behaviour in ways analogous to the market effects of misstated financial statements [

7].

Academic research increasingly recognises parallels between financial fraud and ESG-washing, emphasising their mutual dependence on the fragile nature of trust and the centrality of transparency in sustaining capital markets [

8,

9]. When investor confidence is compromised, both types of misconduct can have cascading effects — from reduced market participation to systemic instability — that extend beyond the immediate actors involved. This conceptual convergence underscores the necessity for integrated governance frameworks, combining the verification of both financial and non-financial disclosures within a unified assurance architecture. In such a system, internal audit functions, external assurance providers, and regulatory oversight bodies play complementary roles in safeguarding disclosure integrity. Nevertheless, there remains a notable gap in empirical research examining how these governance structures influence investor decision-making in the specific context of ESG-washing [

10].

The present study seeks to address this gap by analysing the perceptions and experiences of professionals engaged in investment-related decisions, focusing on the prevalence, detection, and consequences of both financial fraud and ESG-washing. Using survey-based empirical data, the analysis investigates how these forms of misconduct affect trust in corporate disclosures, alter investment preferences, and interact with evolving regulatory frameworks. By embedding the findings within a historical and theoretical perspective, the study aims to enrich academic understanding while offering practical guidance for regulators, policymakers, and corporate leaders committed to maintaining transparency and protecting market integrity.

2. Literature Review

The study of corporate misconduct has long been a focal point in accounting, finance, and governance research, tracing its origins from early financial fraud cases such as the South Sea Bubble in the 18th century to contemporary scandals involving multinational corporations. Historical analyses demonstrate that fraudulent practices often emerge from a combination of weak regulatory oversight, misaligned incentives, and information asymmetry between managers and stakeholders [

11,

12,

14]. The collapse of firms such as Enron and WorldCom in the early 2000s catalysed major reforms, including the Sarbanes–Oxley Act, which sought to restore market trust by enhancing corporate accountability and strengthening internal controls [

13]. These landmark events established the importance of reliable disclosures as a cornerstone of efficient capital markets.

In parallel, the rise of the sustainability agenda has introduced new dimensions to corporate transparency, particularly through Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reporting. Frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), and, more recently, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) have aimed to standardise ESG disclosures and improve their comparability [

26]. Yet, despite regulatory advancements, scholars have documented persistent variability in reporting quality, with some firms engaging in symbolic rather than substantive compliance [

7,

21,

22]. This phenomenon, widely referred to as ESG-washing, mirrors the mechanisms of traditional financial fraud by distorting information flows and misrepresenting performance to stakeholders [

2,

32,

33].

Theoretical perspectives provide important insights into why both financial fraud and ESG-washing persist despite formal regulation. Agency theory posits that information asymmetry between principals (shareholders) and agents (managers) incentivises opportunistic behaviour when monitoring is weak [

14]. Legitimacy theory suggests that organisations may engage in selective disclosure to maintain societal approval, even if such disclosures are misleading [

18]. Stakeholder theory emphasises the multiplicity of audiences for corporate reporting, each with differing expectations, creating both pressures and opportunities for misrepresentation [

19]. Behavioural finance further illustrates that investor decision-making is influenced by trust, reputation, and signalling cues, meaning that both accurate and misleading disclosures can significantly affect capital flows [

20,

38].

Empirical evidence has confirmed that perceived corporate integrity influences both investor trust and market valuations [

15,

37,

39]. For instance, studies on greenwashing have shown that exaggerated sustainability claims can erode investor confidence, leading to reputational damage and long-term value destruction [

21,

22]. Notable real-world cases, such as the Volkswagen emissions scandal and controversies around green bonds’ actual environmental impact, illustrate how ESG-washing can undermine market stability by misdirecting capital toward non-sustainable activities. These examples underscore the parallels between traditional financial misrepresentation and ESG-related misconduct, particularly in their shared reliance on exploiting credibility gaps in reporting.

Nevertheless, despite the substantial body of literature on corporate fraud and, separately, on ESG-washing, few studies have examined the interplay between these phenomena in shaping investor perceptions and decision-making. While prior research has investigated the role of mandatory versus voluntary reporting [

34,

35], and the effects of assurance mechanisms on stakeholder trust [

6,

10,

25], the interaction between historical experiences of financial fraud and attitudes toward ESG disclosures remains underexplored. This represents a significant research gap, as prior exposure to misleading financial reporting may influence how stakeholders interpret sustainability information and assess its credibility.

The present study addresses this gap by integrating historical and theoretical insights with empirical survey data to investigate how perceptions of financial misrepresentation affect trust in ESG disclosures and, ultimately, investment decisions. By situating ESG-washing within the broader continuum of corporate integrity challenges, the research contributes to a more nuanced understanding of how traditional and sustainability-related misconduct jointly shape market trust. This approach also responds to calls in the literature for a more holistic view of corporate transparency, one that unites financial and non-financial reporting within a unified governance framework [

4,

27,

28].

3. Data and Methods

The empirical analysis in this study is based on primary data collected through a structured questionnaire designed to assess perceptions of ESG-washing, trust in ESG disclosures, investment preferences, and the influence of prior perceptions of corporate financial misconduct. The questionnaire was distributed between 01/10/2024 and 06/03/2025, for postdoc purposes, to a purposive sample of professionals engaged in auditing, corporate finance, public administration, academia, and sustainability consulting.

To address the research gap identified in the literature, this study employs a quantitative research design based on primary survey data. The methodological approach was selected to capture stakeholders’ perceptions of ESG-washing, trust in ESG disclosures, and the influence of prior experiences with financial misrepresentation on investment decision-making. A survey instrument was deemed suitable for this purpose, as it enables the systematic collection of comparable responses from a diverse respondent base while allowing for the measurement of attitudes, beliefs, and behavioural intentions [

1,

37].

3.1 Survey Design and Instrument

The questionnaire was developed following an extensive review of existing literature on corporate fraud, ESG reporting, and greenwashing practices [

2,

6,

21,

32]. Questions were designed to reflect the theoretical constructs discussed in

Section 2, including trust in corporate reporting, perceived frequency of misleading financial disclosures, and attitudes toward mandatory and voluntary ESG reporting. The instrument comprised both closed-ended and multiple-choice items, structured to facilitate descriptive, inferential, and cross-tabulation analyses. Demographic questions were included to capture respondent characteristics such as gender, age group, educational background, and professional sector, allowing for the examination of potential differences in perceptions across subgroups.

3.2 Sampling and Data Collection

The survey was disseminated electronically to a targeted sample of professionals, academics, and investors across multiple sectors, including finance, academia, and the public sector. This purposive sampling strategy was adopted to ensure that participants possessed sufficient familiarity with financial reporting and sustainability disclosures to provide informed responses. While the non-probability sampling limits generalisability, it provides valuable insights into the perceptions of a relevant and engaged respondent group [

15].

3.3 Variables and Measures

Key variables include:

Perceived frequency of misleading financial reporting (measured on a Likert scale ranging from “never” to “very frequently”).

Perceptions of ESG-washing (categorised as “systematic,” “occasional,” “rare,” or “non-existent”).

Trust in ESG disclosures (distinguishing between mandatory and voluntary reporting).

Impact of ESG-washing on investment trust (ordinal categories reflecting the degree of negative influence).

Demographic characteristics (gender, age, education, professional sector).

These variables were operationalised to align with established constructs in prior research [

15,

21,

32] while enabling cross-tabulations to examine potential relationships between demographic factors, previous experiences, and ESG-related perceptions.

3.4 Analytical Procedures

The analysis was conducted in three stages. First, descriptive statistics were computed to summarise respondent demographics and the distribution of key variables. Second, cross-tabulations with Chi-square tests were used to explore associations between demographic characteristics and attitudes toward ESG-washing, trust in disclosures, and investment behaviour. This approach is consistent with earlier research that examines socio-demographic influences on perceptions of corporate transparency [

3,

38]. Third, a targeted inferential analysis was performed to test the relationship between the perceived frequency of misleading financial reporting and the impact of ESG-washing on investment trust. Statistical significance was assessed at the 5% level (p < 0.05), and results are reported in

Section 4.

This structured methodological approach allows the study to systematically link theoretical insights from the literature to empirical findings, providing a robust basis for interpreting the relationship between historical perceptions of fraud, ESG disclosure credibility, and investment decision-making.

4. Results

The analysis is presented in two main parts: first, the descriptive statistics outlining respondents’ demographic and attitudinal profiles, and second, the results of inferential tests examining associations between perceptions of financial misrepresentation, ESG-washing, trust in disclosures, and investment behaviour.

4.1 Descriptive Statistics

As we mentioned, the empirical analysis draws on 133 completed questionnaires from professionals engaged in finance, auditing, corporate governance, and sustainability-related fields. This targeted sampling aimed to capture informed perspectives on the prevalence, impact, and governance challenges of financial fraud and ESG-washing. The questionnaire combined frequency-based measures with evaluative questions, allowing for both quantitative pattern recognition and interpretation within established theoretical frameworks (see

Appendix A).

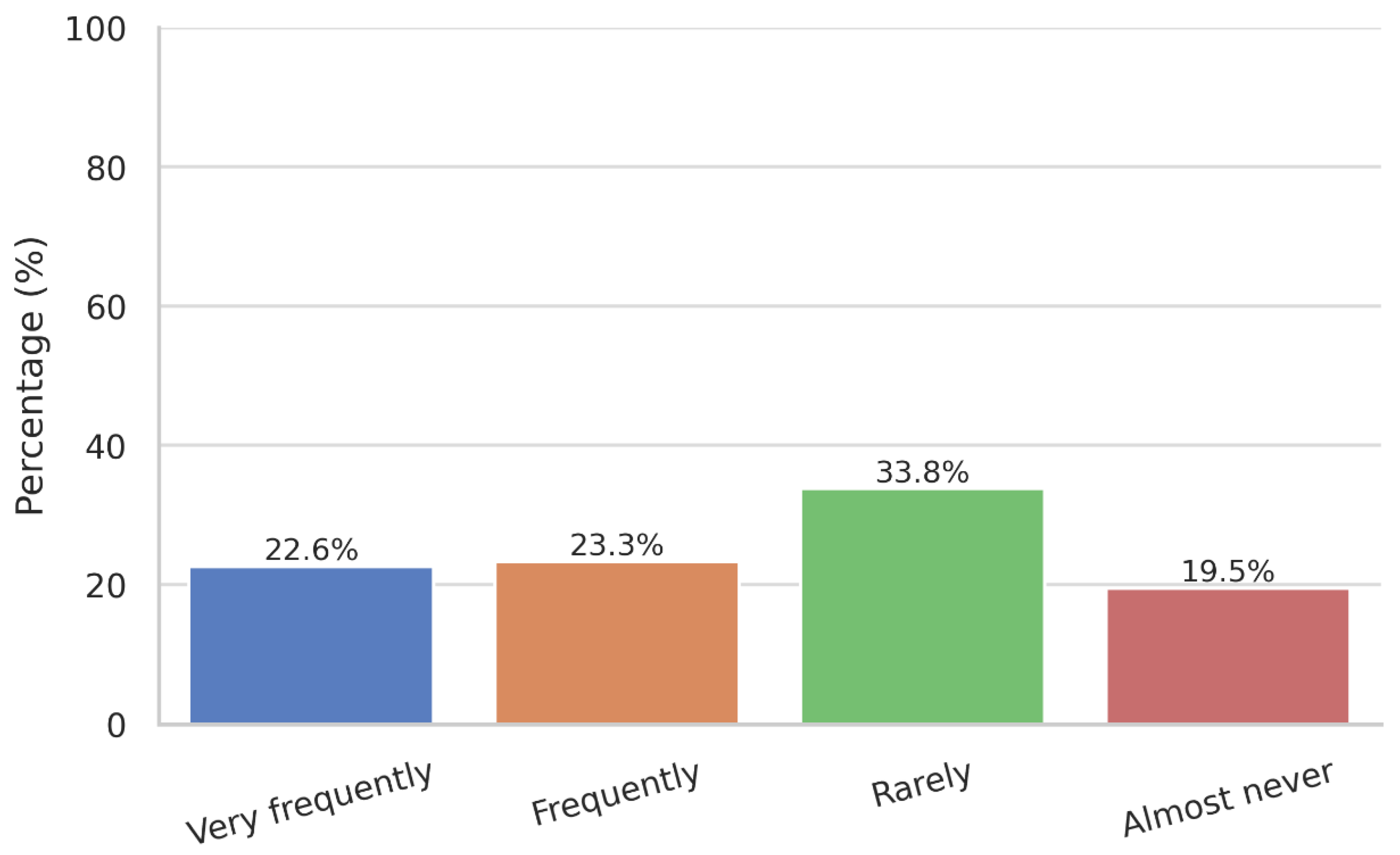

The distribution of responses regarding the frequency with which inaccurate or manipulated financial statements mislead investors is noteworthy (

Figure 1). A combined 45.9% of respondents reported encountering such practices either

very frequently (22.6%) or

frequently (23.3%), while 33.8% indicated they observe them

rarely and 19.5% stated

almost never. These results underscore the continued salience of fraudulent reporting despite decades of regulatory refinement, echoing the argument by Rezaee [

30] and Perols et al. [

31] that fraudulent practices adapt to oversight mechanisms and persist by exploiting emergent informational asymmetries.

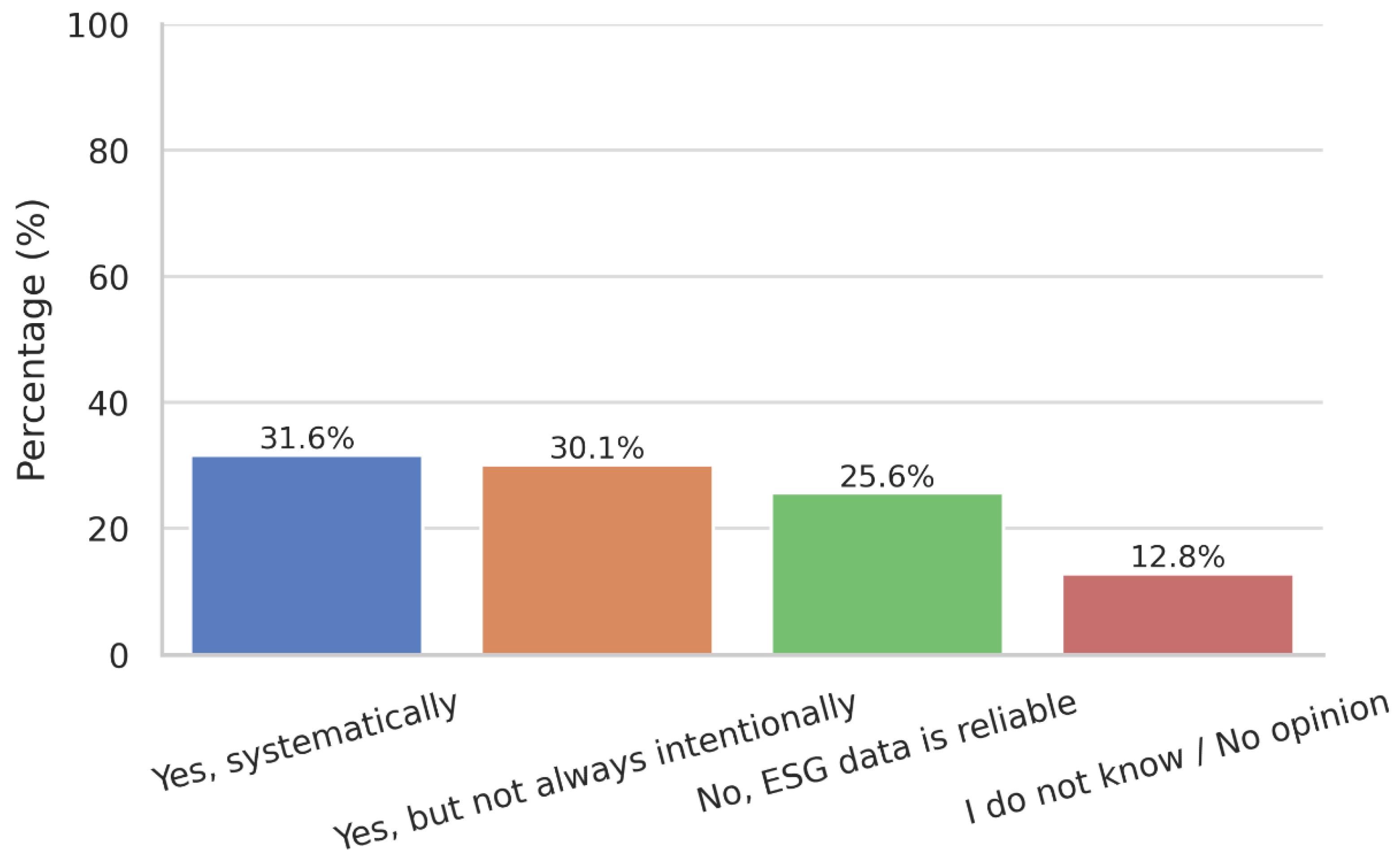

Turning to the perceived prevalence of ESG-washing, the data reveal that 31.6% believe such practices occur

systematically and 30.1% consider them common, though

not always intentional (

Figure 2). In contrast, 25.6% regard ESG data as reliable, while 12.8% express no opinion. These findings are consistent with Lyon and Montgomery’s [

32] conceptualisation of greenwashing as a deliberate strategic communication and with Testa et al.’s [

33] analysis of institutional complexity, which enables selective ESG disclosure. Within the lens of legitimacy theory, such practices can be interpreted as symbolic attempts to preserve organisational legitimacy, while stakeholder theory emphasises their role in selectively influencing key constituencies.

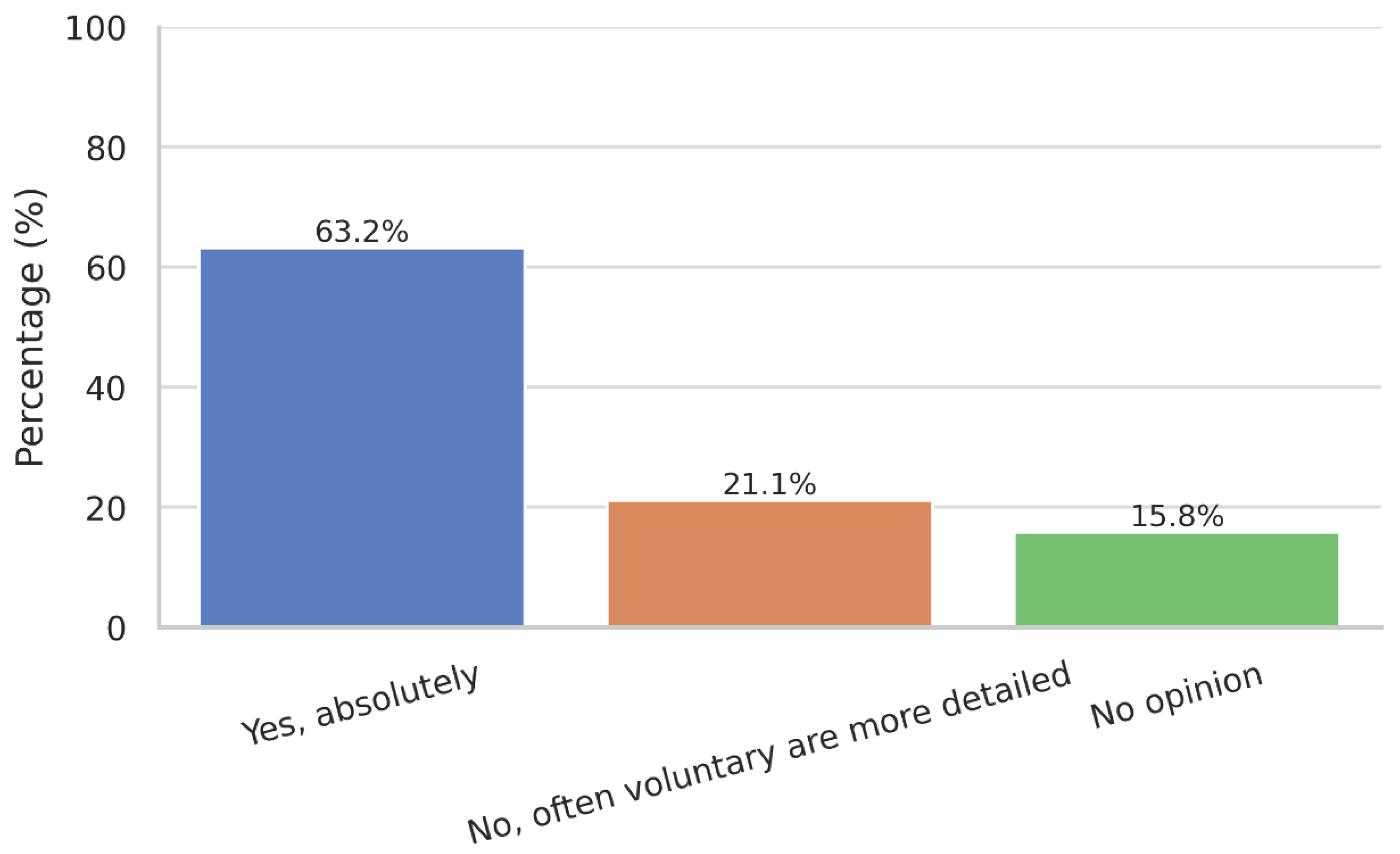

When respondents were asked about the comparative reliability of ESG disclosures, 63.2% expressed greater trust in

mandatory reporting frameworks, 21.1% believed

voluntary disclosures can be more detailed, and 15.8% had no opinion (

Figure 3). This preference aligns with findings by Ioannou and Serafeim [

34] and Christensen et al. [

35], who demonstrate that regulatory compulsion enhances comparability and reduces the scope for selective omission. Behaviourally, mandatory frameworks may function as credibility heuristics, leading stakeholders to assign greater weight to such disclosures when evaluating corporate performance.

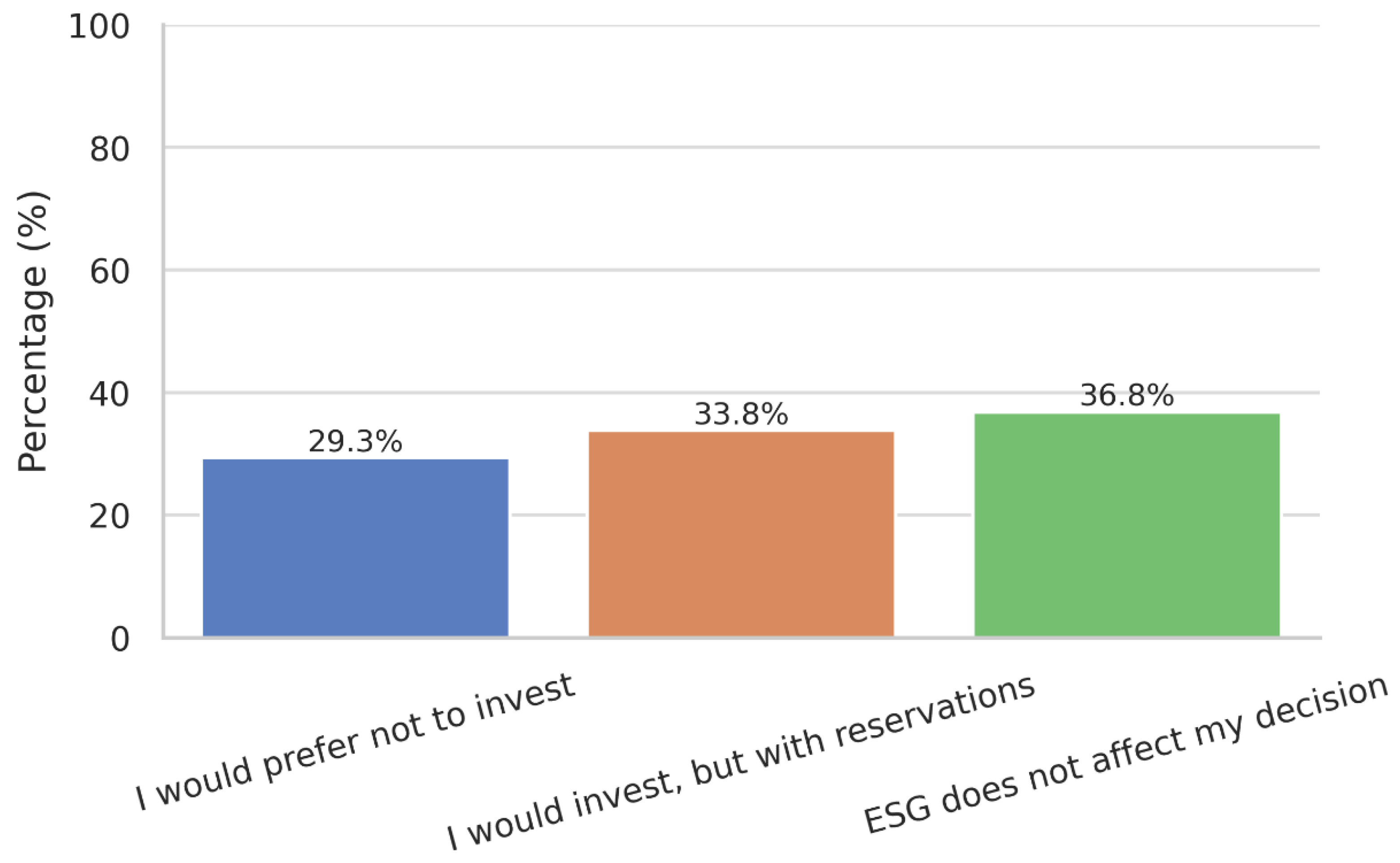

The influence of ESG compliance on investment decisions further illuminates the interplay between ethical and financial considerations (

Figure 4). While 36.8% of respondents stated that ESG criteria do not influence their decision-making, 33.8% indicated they would invest in non-compliant firms

but with reservations, and 29.3% preferred

not to invest in such firms at all. This distribution suggests that although values-based screening is not universal, it remains a substantial determinant for a significant proportion of investors, supporting the observations of Statman and Glushkov [

36] and Riedl and Smeets [

37] regarding the integration of sustainability criteria into investment practice.

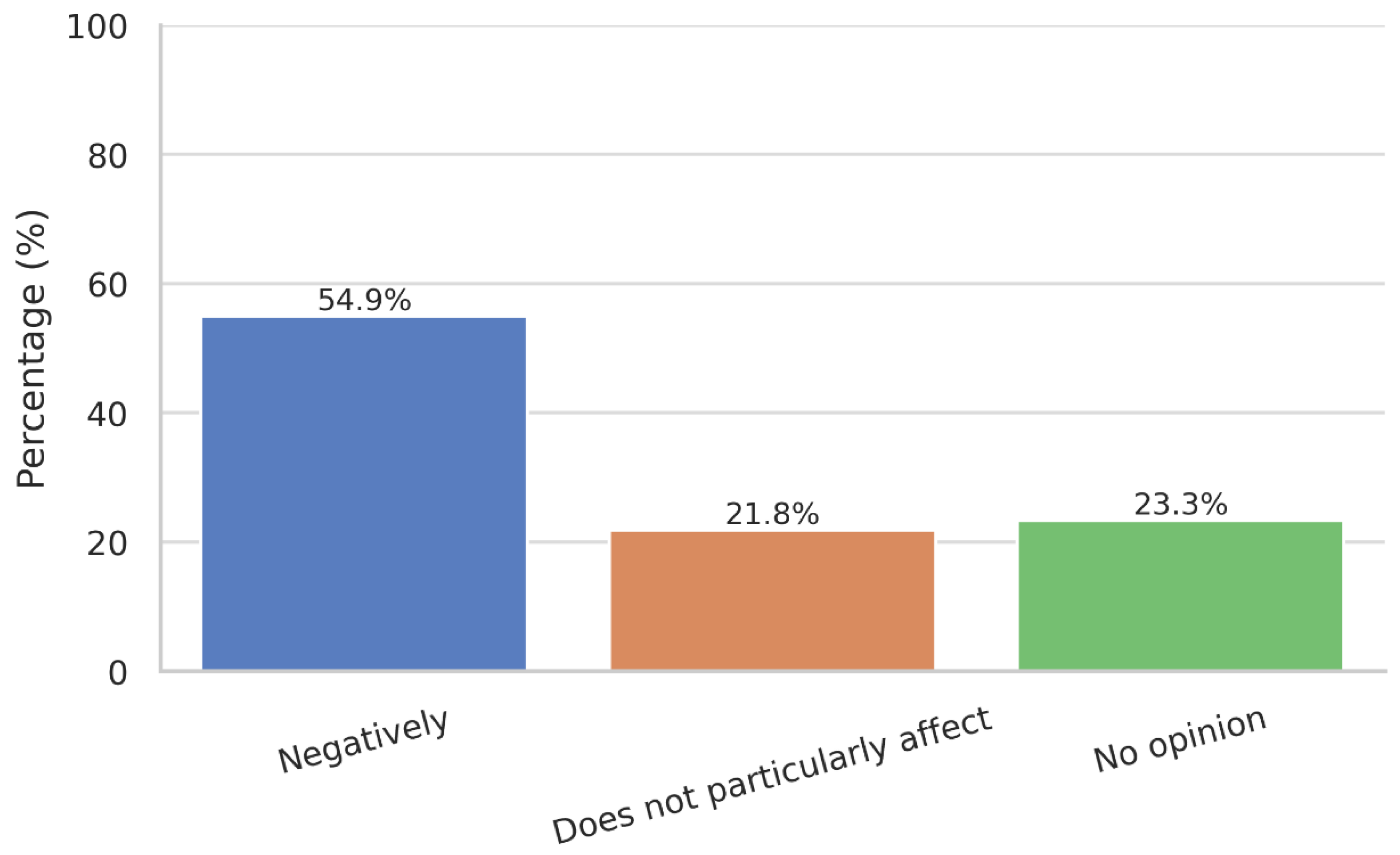

The reported effects of ESG-washing on trust are especially pronounced (

Figure 5). A majority (54.9%) indicated it affects their trust

negatively, 21.8% stated it

does not particularly affect their trust, and 23.3% expressed no opinion. These findings resonate with Guiso et al. [

38], who argue that trust is a critical intangible asset in financial markets, and with Krüger [

39], who shows that negative CSR-related events can depress firm valuation over the long term. The results emphasise that reputational damage from ESG-washing can be as detrimental as that stemming from overt financial fraud.

Taken collectively, these findings demonstrate the interconnectedness of financial fraud and ESG-washing: both are sustained by information asymmetries, both exploit verification gaps, and both exert measurable influence on investor behaviour and market efficiency. The strong preference for mandatory ESG disclosures further reinforces scholarly calls for integrated assurance frameworks that combine financial and non-financial reporting under a coherent regulatory architecture, thereby enhancing credibility and mitigating the systemic risks associated with declining stakeholder trust.

4.2 Extended Analysis (Cross-Tabulations)

To deepen the analysis, a series of cross-tabulations with Chi-square tests were conducted to explore whether demographic characteristics and prior perceptions of financial misrepresentation are associated with attitudes toward ESG-washing, trust in ESG disclosures, and investment behaviour. This approach is consistent with previous research highlighting that socio-demographic factors and past experiences can influence how individuals interpret corporate transparency and sustainability reporting credibility [

1,

2].

The analysis revealed that gender was not significantly associated with perceptions of ESG-washing (χ²(3) = 2.17, p = 0.540). Both male and female respondents displayed similar levels of scepticism, with roughly two-thirds in each group believing ESG-washing occurs either systematically or occasionally. This suggests that perceptions of ESG-washing may be shaped by shared exposure to professional discourse and public debate rather than gender-based differences.

Similarly, no statistically significant relationship was found between age group and trust in mandatory versus voluntary ESG disclosures (χ²(6) = 3.02, p = 0.551). Although younger respondents (18–30 years) showed a slightly higher tendency to trust mandatory disclosures fully, the differences were not meaningful. This finding diverges from certain prior studies that suggested generational variation in regulatory trust [

3] and may indicate a convergence of attitudes across age cohorts.

In the same vein, the professional sector was not significantly associated with investment preferences (χ²(4) = 2.51, p = 0.638). While private sector respondents were marginally more inclined to invest regardless of ESG compliance, and academic respondents somewhat more cautious, the variation did not reach statistical significance. This pattern suggests that ESG investment preferences are more strongly influenced by individual beliefs and the perceived credibility of disclosures than by professional affiliation.

A notable finding emerged in the relationship between perceived frequency of misleading financial reporting (Q7) and the impact of ESG-washing on investment trust (Q13). Here, a statistically significant association was observed (χ²(8) = 15.98, p = 0.040). Respondents who reported that distorted financial data frequently or very frequently mislead investors were substantially more likely to indicate that ESG-washing would negatively affect their investment trust. This supports the theoretical argument that trust in ESG disclosures is embedded within broader assessments of corporate integrity, and that prior perceptions of financial misconduct can heighten vigilance toward ESG misrepresentation [

4].

Overall, these results suggest that while demographic factors did not significantly shape ESG-related attitudes in this sample, prior perceptions of financial fraud play a decisive role in shaping the impact of ESG-washing on investor trust. This reinforces the need for policy measures that address the credibility of both financial and non-financial disclosures as part of a unified corporate governance strategy.

Detailed cross-tabulation outputs, including cell counts, row percentages, and associated Chi-square statistics, are presented in

Appendix B Table B1,

Table B2,

Table B3, and

Table B4 to provide transparency and facilitate replication of the analysis.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study contribute to the growing body of literature examining how perceptions of corporate transparency and ESG credibility influence investment-related decision-making. The descriptive results indicated that a considerable proportion of respondents believe ESG-washing is present in corporate communication, with approximately two-thirds perceiving it as either systematic or occasional. This aligns with prior research suggesting that stakeholders are increasingly aware of the strategic manipulation of sustainability narratives to project a more favourable image than warranted by actual practices [

40,

41]. Such perceptions, when widespread, can undermine the legitimacy of ESG disclosures, reducing their intended effect as tools for stakeholder engagement and informed decision-making.

In terms of trust in ESG disclosures, the majority of respondents expressed greater confidence in mandatory reporting compared to voluntary disclosures. This is consistent with regulatory trust theory, which posits that legally mandated frameworks tend to be perceived as more reliable due to the oversight mechanisms and penalties for non-compliance [

42]. However, our cross-tabulation results revealed that these preferences were relatively uniform across age groups, suggesting a possible convergence of views irrespective of generational differences. This contrasts with earlier studies that have documented generational gaps in trust toward institutional frameworks [

43], potentially reflecting the widespread public discourse on sustainability reporting in recent years, which may have harmonised attitudes.

Similarly, professional affiliation did not significantly influence ESG-based investment preferences. While minor variations were observed—such as slightly higher caution among academics and a greater inclination among private sector respondents to invest despite non-compliance—these differences were not statistically meaningful. This finding may suggest that personal values and perceptions of disclosure credibility carry more weight in shaping investment intentions than professional background alone [

44]. It also implies that policy interventions aimed at strengthening ESG disclosure quality could have a broadly uniform effect across occupational groups.

The most notable empirical relationship identified was between prior perceptions of financial reporting misconduct and the impact of ESG-washing on investment trust. Respondents who believed that investors are frequently or very frequently misled by distorted financial data were significantly more likely to report that ESG-washing would negatively influence their willingness to invest. This pattern reinforces theoretical perspectives that link trust in non-financial disclosures to broader corporate integrity frameworks [

45,

46]. It suggests that scepticism toward ESG claims may be heightened in contexts where financial misrepresentation is perceived as prevalent, creating a spillover effect from financial to sustainability reporting domains.

These results carry important implications for corporate governance and regulatory policy. First, they underscore that bolstering the credibility of ESG disclosures cannot be achieved in isolation; rather, it must be integrated into a holistic strategy addressing the integrity of both financial and non-financial reporting [

47]. Second, the absence of significant demographic effects indicates that such strategies could be effective across a wide spectrum of stakeholder groups, enhancing the efficiency of regulatory interventions. Third, the linkage between perceived financial fraud and ESG-washing sensitivity suggests that rebuilding investor trust may require demonstrable improvements in transparency and accountability across all disclosure channels, supported by independent verification mechanisms [

48].

6. Conclusions

This study examined the interplay between perceptions of ESG-washing, trust in ESG disclosures, and investment behaviour, with particular attention to how demographic characteristics and prior experiences with financial misrepresentation shape these perceptions. The findings provide nuanced insights into the determinants of stakeholder trust in sustainability communication and its potential consequences for capital allocation decisions.

The analysis revealed that demographic characteristics, including gender, age, and professional affiliation, did not significantly influence attitudes toward ESG-washing, trust in ESG disclosures, or ESG-based investment preferences. This suggests that scepticism toward ESG-washing and preferences for mandatory disclosures may be widely shared across societal groups, potentially reflecting the pervasive public discourse and heightened awareness of corporate sustainability practices in recent years [

40,

41].

By contrast, prior perceptions of financial misrepresentation emerged as a significant predictor of how ESG-washing influences investment trust. Respondents who believed that investors are frequently misled by distorted financial reporting were substantially more likely to state that ESG-washing would reduce their willingness to invest. This finding supports the argument that trust in ESG disclosures is embedded in broader assessments of corporate integrity, with scepticism toward one domain of disclosure likely to spill over into others [

45,

46].

From a policy perspective, these results underscore that enhancing the credibility of ESG disclosures requires a holistic approach to corporate reporting integrity. Measures to strengthen sustainability reporting — such as alignment with international standards, third-party assurance, and clearer definitions of materiality — should be implemented alongside continued reforms to financial reporting oversight [

47,

48]. This integrated approach could mitigate the reputational risks associated with ESG-washing and improve investor confidence across both financial and non-financial dimensions.

For corporate managers and investor relations teams, the findings highlight the strategic importance of authentic ESG engagement. In an environment where stakeholders increasingly question the veracity of corporate claims, organisations must demonstrate consistency between their disclosed sustainability commitments and observable operational practices. Failure to do so risks not only reputational damage but also diminished access to capital from increasingly discerning investors [

49].

Future research could build on this work by employing longitudinal designs to track whether sustained regulatory changes and evolving market norms alter the relationship between perceived corporate integrity and stakeholder trust. Additionally, cross-country comparative studies could explore how variations in legal frameworks, cultural attitudes, and media coverage shape the dynamics identified here, further refining the understanding of ESG disclosure credibility in global capital markets [

50,

51,

52].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.; methodology, I.P. and A.G.; software, I.P. and A.G.; validation, I.P. and A.G.; formal analysis, I.P.; investigation, I.P.; resources, I.P.; data curation, I.P.; writing—original draft preparation, I.P. and A.G.; writing—review and editing, I.P.; visualization, I.P. and A.G.; supervision, A.G.; project administration, I.P.; funding acquisition, I.P. and A.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the datasets.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

| ESG |

Environmental, Social, Governance |

| CSRD |

Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive |

| CSR |

Corporate Social Responsibility |

| OECD |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Respondent Demographics

This appendix summarises the demographic composition of the respondents and presents descriptive statistics for the principal survey variables. A total of 133 valid responses were collected from professionals engaged in auditing, corporate finance, public administration, academia, and sustainability consulting. Percentages are calculated relative to the total number of respondents.

Table A1 presents the distribution of respondents by gender, age group, and professional sector.

Table A1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample (n = 133)

Table A1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample (n = 133)

| Variable |

Category |

n |

% |

| Gender |

Male |

114 |

85.7% |

| |

Female |

19 |

14.3% |

| Age group |

18–30 years |

9 |

6.8% |

| |

31–45 years |

44 |

33.1% |

| |

46–60 years |

42 |

31.6% |

| |

61+ years |

38 |

28.6% |

| Professional sector |

Private sector |

46 |

34.6% |

| |

Public sector |

44 |

33.1% |

| |

Academic community |

43 |

32.3% |

Table A2 summarises the main substantive variables analysed in the study, corresponding to selected items from the questionnaire.

Table A2.

Descriptive statistics for the main study variables.

Table A2.

Descriptive statistics for the main study variables.

| Variable |

Category |

n |

% |

| Q7 – Frequency of misleading financial reporting |

Rarely |

45 |

33.8% |

| |

Frequently |

31 |

23.3% |

| |

Very frequently |

30 |

22.6% |

| |

Almost never |

26 |

19.5% |

| Q9 – Perceived prevalence of ESG-washing |

Yes, systematically |

42 |

31.6% |

| |

Yes, but not always intentional |

40 |

30.1% |

| |

No, ESG data is reliable |

34 |

25.6% |

| |

No opinion |

17 |

12.8% |

| Q14 – Trust in mandatory vs. voluntary ESG disclosures |

Yes, absolutely |

84 |

63.2% |

| |

No, often voluntary are more detailed |

28 |

21.1% |

| |

No opinion |

21 |

15.8% |

| Q12 – ESG compliance and investment preferences |

ESG does not affect my decision |

49 |

36.8% |

| |

Would invest, but with reservations |

45 |

33.8% |

| |

Prefer not to invest |

39 |

29.3% |

| Q13 – Impact of ESG-washing on trust |

Negatively |

73 |

54.9% |

| |

No opinion |

31 |

23.3% |

| |

Does not particularly affect |

29 |

21.8% |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Cross-Tabulation Outputs

Table 1.

Gender × Perceived ESG-washing (Q9).

Table 1.

Gender × Perceived ESG-washing (Q9).

| Gender |

ESG-washing does not occur (reliable data) |

Don’t know / No opinion |

Yes, but not always intentional |

Yes, systematically |

| Male |

30 (26.3%) |

13 (11.4%) |

36 (31.6%) |

35 (30.7%) |

| Female |

4 (21.1%) |

4 (21.1%) |

4 (21.1%) |

7 (36.8%) |

Table 2.

Age group × Trust in mandatory vs voluntary ESG disclosures (Q14).

Table 2.

Age group × Trust in mandatory vs voluntary ESG disclosures (Q14).

| Age group |

No, voluntary are often more detailed |

No opinion |

Yes, absolutely |

| 18–30 |

1 (11.1%) |

1 (11.1%) |

7 (77.8%) |

| 31–45 |

7 (15.9%) |

6 (13.6%) |

31 (70.5%) |

| 46–60 |

8 (19.0%) |

8 (19.0%) |

26 (61.9%) |

| 61+ |

12 (31.6%) |

6 (15.8%) |

20 (52.6%) |

Table 3.

Professional sector × ESG-based investment preferences (Q12).

Table 3.

Professional sector × ESG-based investment preferences (Q12).

| Sector |

Would invest but with caution |

Would prefer not to invest |

ESG does not affect my decision |

| Academic community |

14 (32.6%) |

14 (32.6%) |

15 (34.9%) |

| Public sector |

13 (29.5%) |

11 (25.0%) |

20 (45.5%) |

| Private sector |

18 (39.1%) |

14 (30.4%) |

14 (30.4%) |

Table 4.

Fraud frequency (Q7) × ESG-washing impact on investment trust (Q13).

Table 4.

Fraud frequency (Q7) × ESG-washing impact on investment trust (Q13).

| Perceived fraud frequency |

Strong negative impact |

Moderate impact |

No significant impact |

| Very frequently |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (100.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Frequently |

16 (53.3%) |

9 (30.0%) |

5 (16.7%) |

| Occasionally |

21 (46.7%) |

11 (24.4%) |

13 (28.9%) |

| Often |

25 (80.6%) |

2 (6.5%) |

4 (12.9%) |

| Almost never |

11 (42.3%) |

8 (30.8%) |

7 (26.9%) |

References

- Dyck, A., Morse, A., & Zingales, L. (2010). Who blows the whistle on corporate fraud? Journal of Finance, 65(6), 2213–2253. [CrossRef]

- Tapia, C., & Alberti, F. G. (2019). The impact of greenwashing on CSR credibility: A review of the literature. Sustainability, 11(19), 5380. [CrossRef]

- Scholtens, B., & Dam, L. (2007). Cultural values and international differences in business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(3), 273–284. [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R. G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2014). The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management Science, 60(11), 2835–2857. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M., Serafeim, G., & Yoon, A. (2016). Corporate sustainability: First evidence on materiality. Accounting Review, 91(6), 1697–1724. [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O., & Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. (2020). Sustainability reporting assurance: Creating stakeholder trust or a façade? Journal of Business Ethics, 155(1), 167–182.

- Marquis, C., & Qian, C. (2014). Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Symbol or substance? Organization Science, 25(1), 127–148. [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C. J., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33(2), 233–258. [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374. [CrossRef]

- Manetti, G., & Becatti, L. (2009). Assurance services for sustainability reports: Standards and empirical evidence. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(1), 289–298. [CrossRef]

- Neal, L. (1990). The rise of financial capitalism: International capital markets in the age of reason. Cambridge University Press.

- Benston, G. J. (2006). Following the money: The Enron failure and the state of corporate disclosure. AEI-Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies.

- Coates, J. C. (2007). The goals and promise of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1), 91–116. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. [CrossRef]

- Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A. (2015). ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 5(4), 210–233. [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R. G., & Klimenko, S. (2019). The investor revolution: Shareholders lead on sustainability. Harvard Business Review, 97(3), 106–116.

- KPMG. (2022). The time has come: The KPMG Survey of Sustainability Reporting 2022. https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2022/10/the-time-has-come.html.

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman. [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N., & Thaler, R. (2003). A survey of behavioral finance. Handbook of the Economics of Finance, 1, 1053–1128. [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M. A., & Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1), 64–87. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. H., & Lyon, T. P. (2015). Greenwash vs. brownwash: Exaggeration and undue modesty in corporate sustainability disclosure. Organization Science, 26(3), 705–723. [CrossRef]

- Ball, R. (2009). Market and political/regulatory perspectives on the recent accounting scandals. Journal of Accounting Research, 47(2), 277–323. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. (2017). Enterprise risk management and the financial reporting process: The experiences of audit committee members, CFOs, and external auditors. Contemporary Accounting Research, 34(2), 1178–1209. [CrossRef]

- Perego, P., & Kolk, A. (2012). Multinationals’ accountability on sustainability: The evolution of third-party assurance of sustainability reports. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(2), 173–190. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2022). Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive. https://finance.ec.europa.eu/capital-markets-union-and-financial-markets/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/corporate-sustainability-reporting_en [accesed on 10/08/2025].

- Coffee, J. C. (2007). Gatekeepers: The professions and corporate governance. Oxford University Press.

- Berg, F., Kölbel, J. F., & Rigobon, R. (2022). Aggregate confusion: The divergence of ESG ratings. Review of Finance, 26(6), 1315–1344. [CrossRef]

- Serafeim, G. (2020). How to build enduring commitment to long-term goals. California Management Review, 62(4), 74–100.

- Rezaee, Z. (2005). Causes, consequences, and deterrence of financial statement fraud. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 16(3), 277–298. [CrossRef]

- Perols, J. L., Bowen, R. M., Zimmerman, D., & Samba, B. (2017). Finding fraud: The value of accounting anomalies. Review of Accounting Studies, 22(2), 469–519.

- Lyon, T. P., & Montgomery, A. W. (2015). The means and end of greenwash. Organization & Environment, 28(2), 223–249. [CrossRef]

- Testa, F., Boiral, O., & Iraldo, F. (2018). Internalization of environmental practices and institutional complexity: Can stakeholders’ pressures encourage greenwashing? Journal of Business Ethics, 147(2), 287–307. [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2017). The consequences of mandatory corporate sustainability reporting. Harvard Business School Research Working Paper, (11-100). [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H. B., Hail, L., & Leuz, C. (2021). Mandatory CSR and sustainability reporting: Economic analysis and literature review. Review of Accounting Studies, 26(3), 1176–1248. [CrossRef]

- Statman, M., & Glushkov, D. (2009). The wages of social responsibility. Financial Analysts Journal, 65(4), 33–46. [CrossRef]

- Riedl, A., & Smeets, P. (2017). Why do investors hold socially responsible investments? Journal of Finance, 72(6), 2505–2550. [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2008). Trusting the stock market. Journal of Finance, 63(6), 2557–2600. [CrossRef]

- Krüger, P. (2015). Corporate goodness and shareholder wealth. Journal of Financial Economics, 115(2), 304–329. [CrossRef]

- Laufer, W. S. (2003). Social accountability and corporate greenwashing. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(3), 253–261. [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T. P., & Maxwell, J. W. (2011). Greenwash: Corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 20(1), 3–41. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H. B., Hail, L., & Leuz, C. (2021). Mandatory CSR and sustainability reporting: Economic analysis and literature review. Review of Accounting Studies, 26(3), 1176–1248. [CrossRef]

- Parment, A. (2013). Generation Y vs. Baby Boomers: Shopping behavior, buyer involvement and implications for retailing. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 20(2), 189–199. [CrossRef]

- Riedl, A., & Smeets, P. (2017). Why do investors hold socially responsible investments? Journal of Finance, 72(6), 2505–2550. [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, Z. (2005). Causes, consequences, and deterrence of financial statement fraud. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 16(3), 277–298. [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2008). Trusting the stock market. Journal of Finance, 63(6), 2557–2600. [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O., & Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. (2020). Sustainability reporting assurance: Creating stakeholder trust or a façade? Journal of Business Ethics, 155(1), 167–182.

- Perego, P., & Kolk, A. (2012). Multinationals’ accountability on sustainability: The evolution of third-party assurance of sustainability reports. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(2), 173–190. [CrossRef]

- Kotsantonis, S., Pinney, C., & Serafeim, G. (2016). ESG integration in investment management: Myths and realities. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 28(2), 10–16. [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2012). What drives corporate social performance? The role of nation-level institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(9), 834–864.

- Passas, I. The Evolution of ESG: From CSR to ESG 2.0. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1711-1720. [CrossRef]

- Yiannoulis, Y.; Vortelinos, D.; Passas, I. Exploring Audit Opinions: A Deep Dive into Ratios and Fraud Variables in the Athens Exchange. Account. Audit. 2025, 1, 3. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).