Submitted:

13 August 2025

Posted:

14 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods and Materials

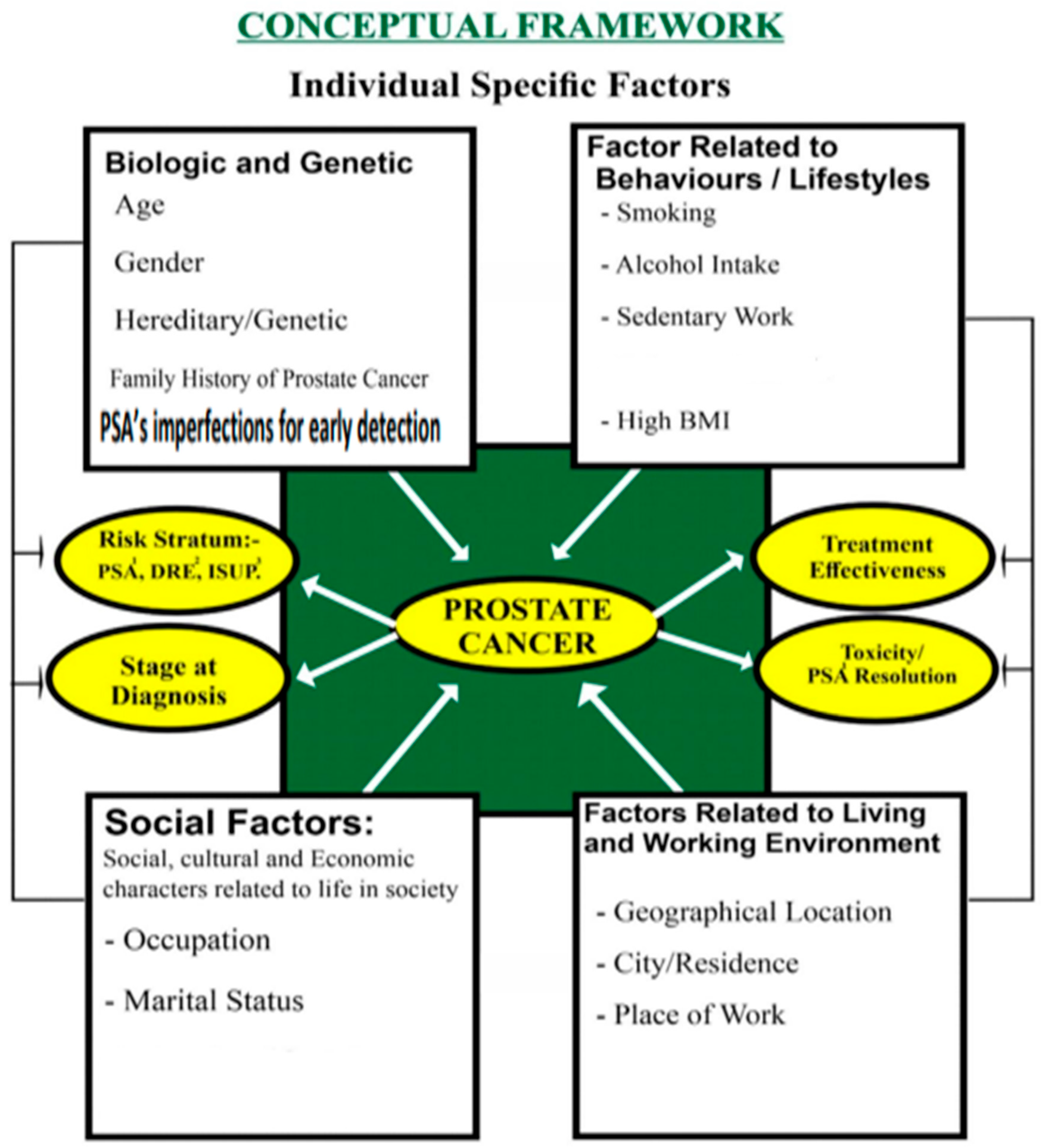

Conceptual Framework

Study Design and Setting

Study Population

Inclusion Criteria

Exclusion Criteria

Data Sources and Extraction

Study Variables

Independent Variables

Dependent Variables

Sample Size and Sampling

Data Collection Tool

Data Management

Statistical Analysis

Bias and Confounding

Ethical Approval

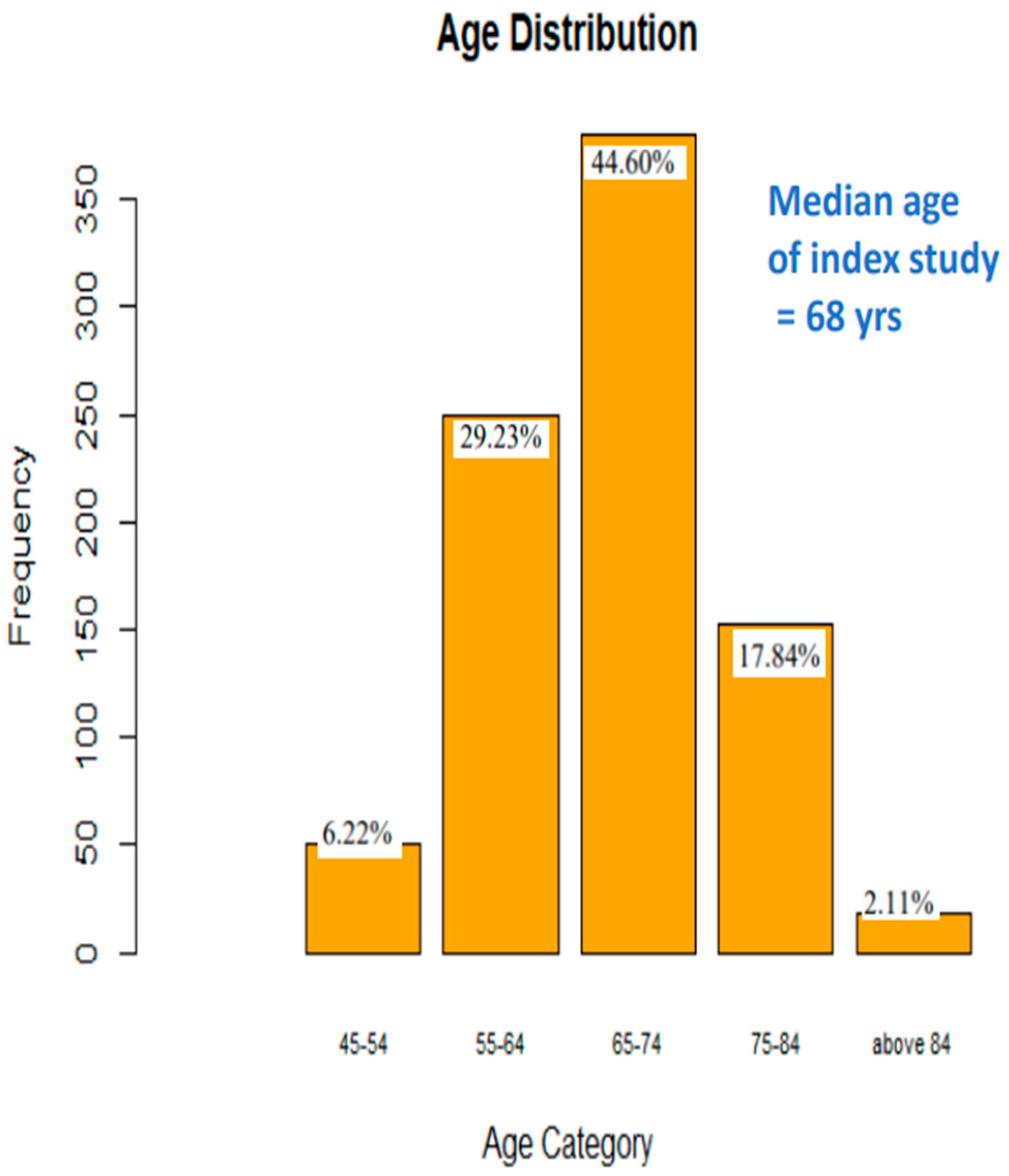

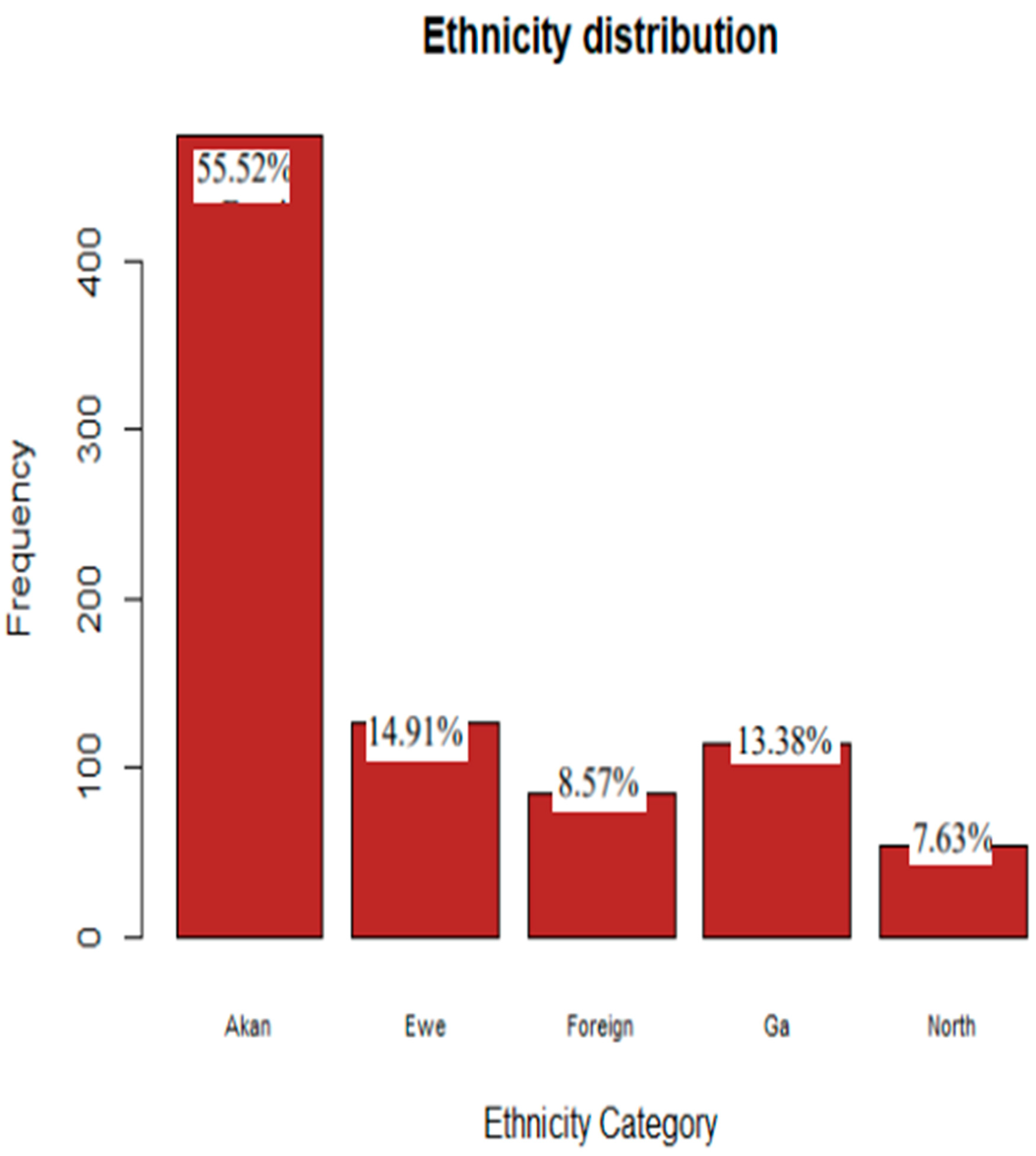

Results

Discussion

Comparison with Existing Literature

Limitations

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Laryea DO, Awuah B, Amoako YA et al. Cancer incidence in Ghana, 2012: evidence from a population-based cancer registry. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:362. Available from: https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2407-14-362. [CrossRef]

- Hsing AW, Tsao L, Devesa SS et al. International Trends and Patterns of Prostate Cancer Incidence and Mortality. Int J Cancer. 2000;85(1):60–67. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000101)85:1<60::AID-IJC11>3.0.CO;2-B. [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Globocan. Cancer statistics, 2020 [Internet]. WHO/IARC; cited 2023 Mar 22. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr.

- Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2014: Key Indicators. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service; 2014.

- Odedina FT, Akinremi TO, Chinegwundoh F et al. Prostate cancer disparities in black men of African descent: comparative literature review. Infect Agents Cancer. 2009;4(Suppl 1):S2. [CrossRef]

- Rebbeck TR, Haas GP, Colbert LE et al. Origins of human prostate cancer. Cancer J. 2014;20(3):196–201. [CrossRef]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Behav. 1988;15(4):351–377. [CrossRef]

- Amoako YA, Hammond EN, Assasie-Gyimah A et al. Prostate-specific antigen and risk of bone metastases in West Africans with prostate cancer. World J Nucl Med. 2019;18:143–148. [CrossRef]

- Catalona WJ, Partin AW, Sanda MG et al. [−2]pro-PSA combined with PSA and free PSA for prostate cancer detection in the 2.0–10.0 ng/ml range. J Urol. 2011;185(5):1650–1655. [CrossRef]

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. Prostate Cancer – Statistics. Prostate Cancer - Statistics [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/prostate-cancer/statistics.

- Wiredu EK, Armah HB. Cancer mortality patterns in Ghana: a 10-year review of autopsies and hospital mortality. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:159. [CrossRef]

- Biritwum RB, Yarney J, Mensah G et al. Cancer incidence in Ghana, 2012: evidence from a population-based cancer registry. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:736. [CrossRef]

- Gyedu AA, Salazar K, Lee JJ et al. Ethnic and geographic variations in the epidemiology of prostate cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: systemic review. Int J Cancer. 2018;142(2):241–248. [CrossRef]

- Seibert TM, Garraway IP, Plym A et al. Genetic Risk Prediction for Prostate Cancer: Implications for Early Detection and Prevention. Eur Urol. 2023;83(3):241–248. [CrossRef]

- Rota M, Scotti L, Turati F et al. Alcohol consumption and prostate cancer risk: dose–risk meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21(4):350–359. [CrossRef]

- Maamri A. Conceptual framework: the amount and various determinants of cancer in Morocco. OJPM. 2015;5(10):047. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=60666. [CrossRef]

- Kyei MY, Mensah JE, Djagbletey R et al. Trifecta outcomes after open radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer in Ghana. Open J Urol. 2023;13(8):282–292. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I et al. Estimating global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: sources and methods (GLOBOCAN). Int J Cancer. 2020;144(8):1941–1953. [CrossRef]

- Jemal A, Bray F, Forman D et al. Cancer burden in Africa and opportunities for prevention. Cancer. 2016;118(18):4372–4384. [CrossRef]

- Obeng F et al. Prostate cancer disease determinants, disease severity, and treatment outcomes in Ghana: retrospective study, SGMC-2023 [MPH thesis]. Kpong (Ghana): Ensign Global College; 2024. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382690202_FULL_THESIS….

- Adeloye D, David RA, Aderemi AV et al. An estimate of the prevalence of prostate cancer in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153496. [CrossRef]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. [CrossRef]

- Dunstan DW, Howard B, Healy GN et al. Too Much Sitting—A Health Hazard. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97(3):368–376. [CrossRef]

- Chinegwundoh F, Enver M, Lee A et al. Risk and presenting features of prostate cancer among African Caribbean, South Asian and European men in North East London. BJU Int. 2006;98(6):1216–1220. [CrossRef]

- Liede A, Malik IA, Aziz Z et al. Contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to breast and ovarian cancer in Pakistan. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71(3):595–606. [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff T, Kauff ND, Mitra N et al. BRCA mutations and risk of prostate cancer in Ashkenazi Jews. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(9):2918–2921. [CrossRef]

- Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP et al. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3869–3876. [CrossRef]

- Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E et al. Physical activity and survival after prostate cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(6):726–732. [CrossRef]

- Cao Y, Ma J, Zhang J et al. The role of obesity in prostate cancer. Front Oncol. 2018;8:743. [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2021 [Internet]. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2021. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-figures/2021.pdf.

| ATTRIBUTE/ PARAMETER; and VARIABLES | TOTALS | ||||||||||

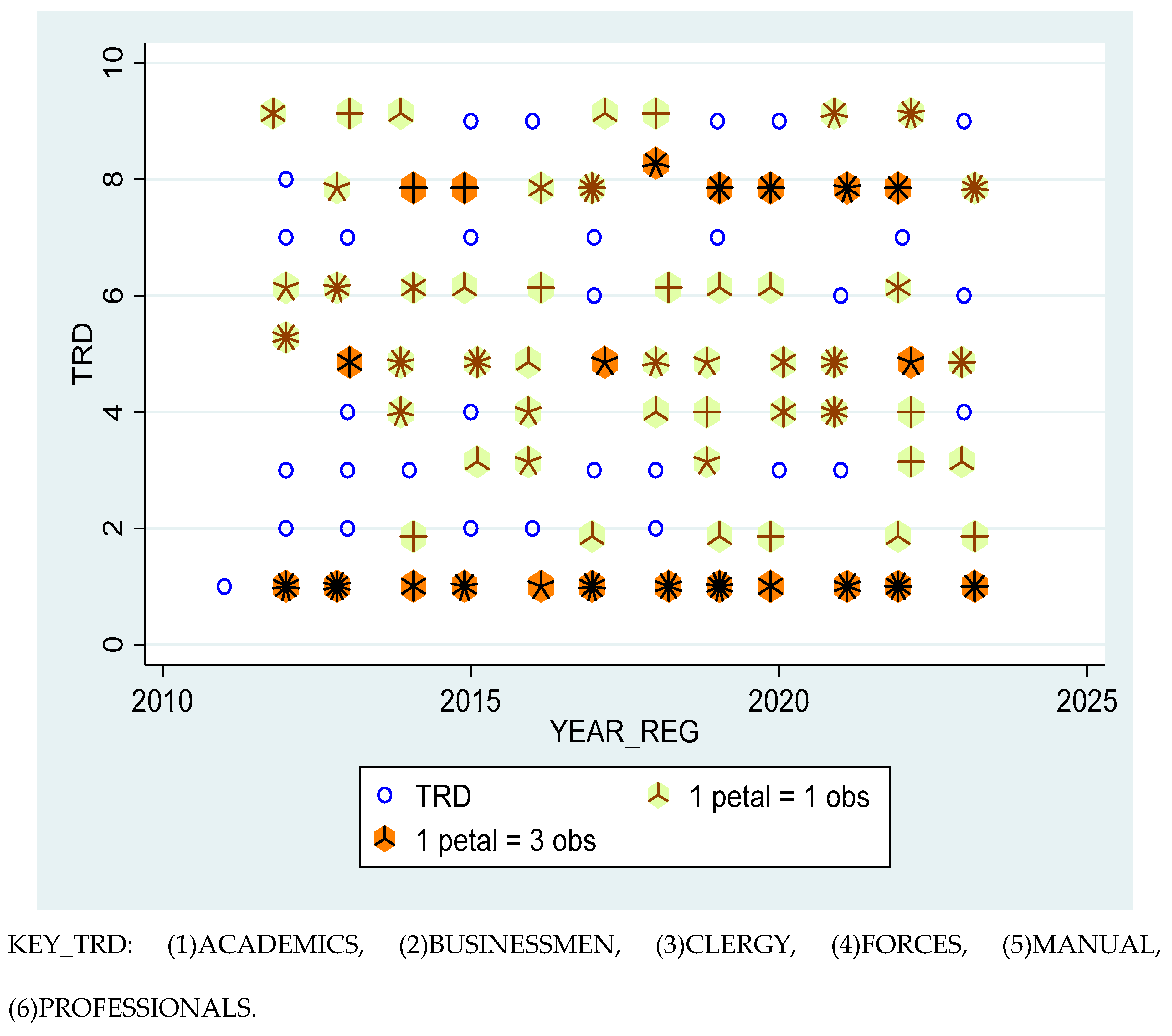

| OCCUPATION AS TRADITIONALLY CLASSIFIED | |||||||||||

| ACADEMICS | BUSINESS -MEN |

CLERGY | FORCES | MANUAL | PROFESSIONALS | RETIRED/NOT STATED | UNEMPLOYED | TOTAL | |||

| 3.52% | 5.74% | 3.63% | 5.28% | 13.60% | 40.33% | 27.06% | 0.84% | 100% | |||

| SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS (SES) BASED ON OCCUPATIONS∗ | |||||||||||

| LOW SES | HIGH SES | RETIRED | NOT STATED | TOTAL | |||||||

| 13.5% | 59.4% | 21.7% | 5.4% | 100% | |||||||

| ACTIVITY LEVELS BASED ON OCCUPATIONAL∗ | |||||||||||

| SEDENTARY | NON-SEDENTARY | - | RETIRED /NOT STATED/NA | TOTAL | |||||||

| 31.07% | 43.85% | - | 24.08% | 100% | |||||||

| BMI CATEGORIES | |||||||||||

| UNDERWEIGHT | NORMAL BMI | OVERWEIGHT | OBESE/ MORBIDLY OBESE |

TOTAL | |||||||

| 4.23% | 26.9% | 53.4% | 16.08% | 100% | |||||||

| SMOKING HABIT | |||||||||||

| YES | NO | NOT STATED | TOTAL | ||||||||

| 8.6% | 81.8% | 9.6% | 100% | ||||||||

| ALCOHOL HABIT | |||||||||||

| YES | NO | NOT STATED | TOTAL | ||||||||

| 31.3% | 61.2% | 7.5% | 100% | ||||||||

| PARAMETER | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| AGE (yrs) | 852 | 67.385 | 8.41 | 45 | 91 |

| WEIGHT(Kg) | 852 | 77.332 | 14.693 | 38.9 | 152.2 |

| HEIGHT(M) | 852 | 1.71 | 0.07 | 1.50 | 1.99 |

| BMI (Kg/M2) | 852 | 26.571 | 6.396 | 14.53 | 41.42 |

| LINEAR W-H (Kg/M) | 852 | 44.95 | 7.00 | 24.46 | 72.06 |

| PONDEREX (Kg/M3) | 852 | 15.46 | 2.62 | 8.54 | 25.18 |

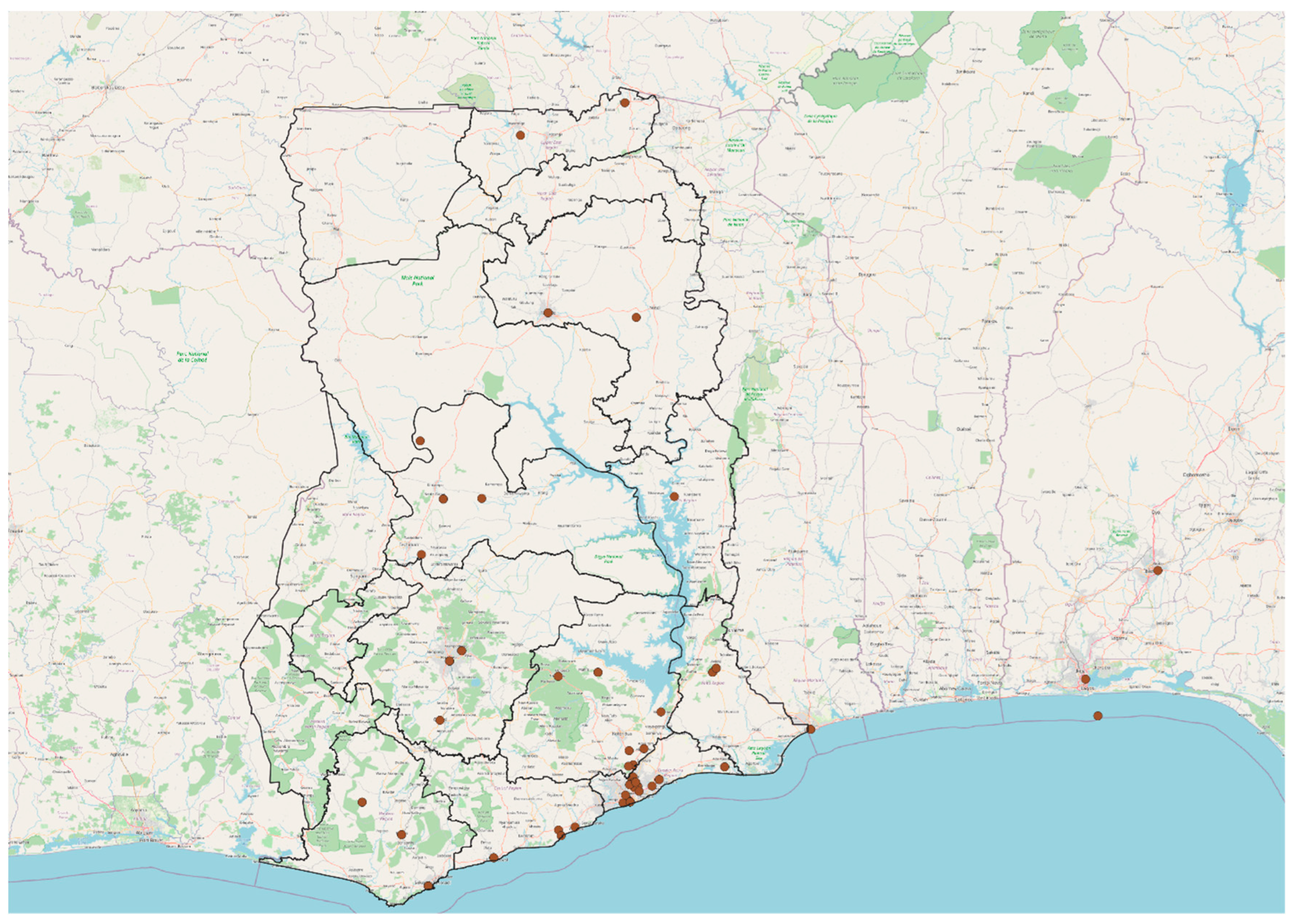

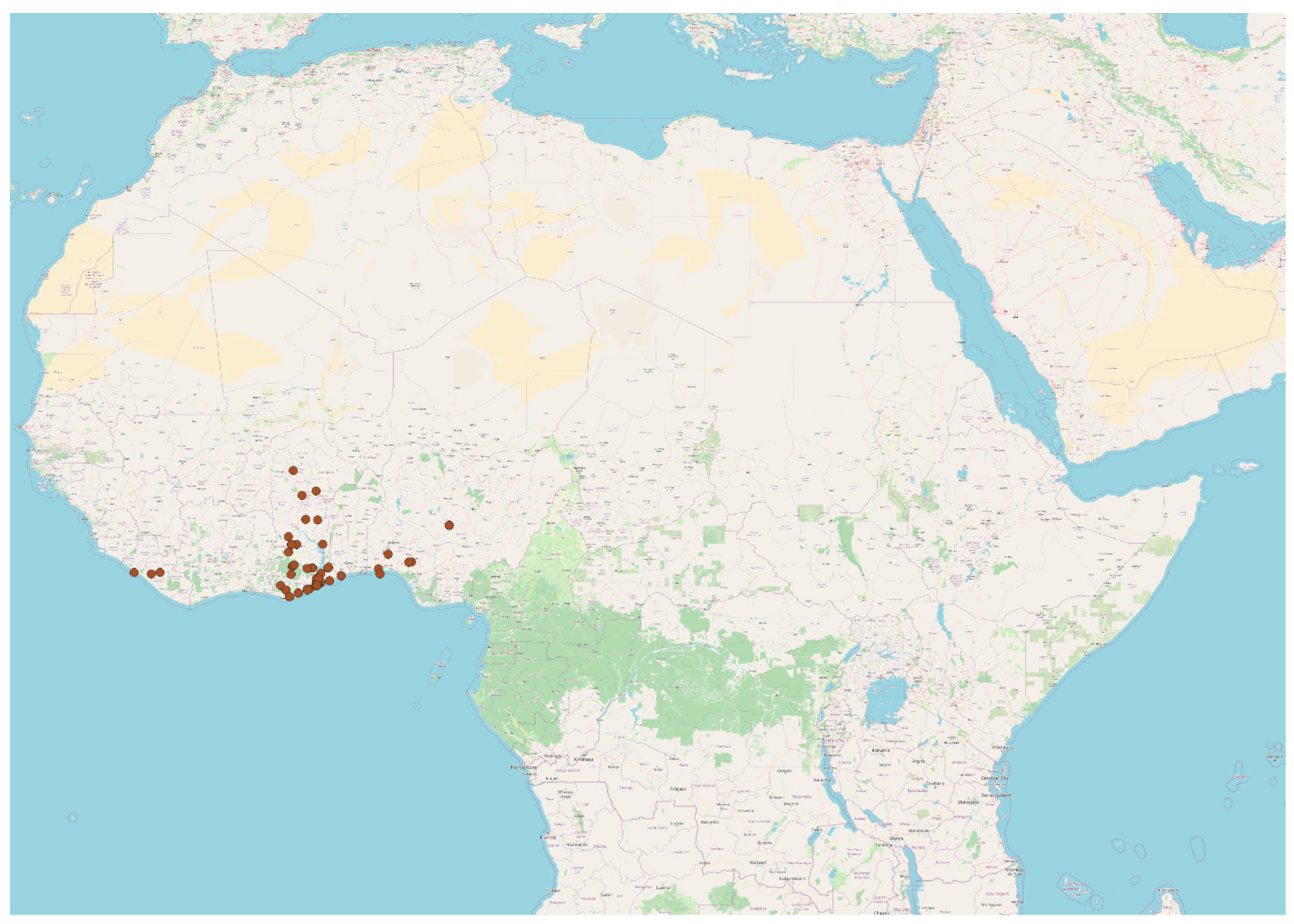

| Region | Patient Count | Percentage (%) | Cumulative (%) |

| Accra | 364 | 43.75 | 43.75 |

| Volta Region | 122 | 14.66 | 58.41 |

| Kumasi | 56 | 6.73 | 65.14 |

| Tema | 53 | 6.37 | 71.51 |

| Ho | 35 | 4.21 | 75.72 |

| Hohoe | 19 | 2.28 | 78 |

| Nigeria (Abuja) | 10 | 1.2 | 79.2 |

| Koforidua | 10 | 1.2 | 80.4 |

| Togo | 9 | 1.08 | 81.48 |

| Cape Coast | 9 | 1.08 | 82.56 |

| Takoradi | 7 | 0.84 | 83.4 |

| Kasoa | 6 | 0.72 | 84.12 |

| Tamale | 5 | 0.6 | 84.72 |

| Sunyani | 5 | 0.6 | 85.32 |

| Bolgatanga | 3 | 0.36 | 85.68 |

| Navrongo | 3 | 0.36 | 86.04 |

| Lagos | 2 | 0.24 | 86.28 |

| Other Regions | 114 | 13.72 | 100.00 |

| PARAMETER | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| PSA AT DIAGNOSIS (ng/ml); Median value = 29.0 ng/ml | 852 | 496.391 | 2240.127 | .19 | 25000 |

| PSA AT THE BEGINNING OF TREATMENT (ng/ml) | 419 | 559.198 | 2664.561 | .05 | 25000 |

| DOSE OF RADIATION TREATMENT RECEIVED(Grays) | 852 | 0.000∗ ∗(Median) |

0.000∗ ∗ (Mode) |

0.00 | 78.00 |

| LOWEST PSA / NADIR (ng/ml) |

852 | 154.750 | 545.251 | .020 | 5405.50 |

| PSA RESOLUTION (ng/ml) | 852 | 233.983 | 2065.528 | -5393.28 | 249600 |

| PSA PER DOSE OF RADIATION (ng/ml- per Gray) | 852 | 31.602 | 905.751 | -5393.28 | 15299.80 |

| PSA RESOLUTION PER TREATMENT MODALITY (ng/ml) | 852 | 228.514 | 2034.179 | -5360.50 | 24960.00 |

| HIGHEST PSA (ng/ml) | 852 | 1210.764 | 3982.174 | .25 | 25000.00 |

| FAIL PSA (ng/ml) | 128 | 249.514 | 560.037 | .58 | 2600.00 |

| FAIL-RESOLUTION-MULTIPLES (unitless) | 852 | 4.579 | 39.794 | 0.00 | 512.80 |

| COMORBIDITY | FREQUENCY | PERCENTAGE | CUMMULATIVE PERCENTAGE |

| None | 668 | 78.43 | 78.43 |

| Hypercholesterolemia Alone | 1 | 0.12 | 78.55 |

| Diabetes Alone | 17 | 1.99 | 80.54 |

| Hypertension Alone | 90 | 10.55 | 91.09 |

| Hypertension And Hypercholesterolemia | 2 | 0.23 | 91.32 |

| Hypertension And Diabetes | 35 | 4.10 | 95.43 |

| Hypertension, Diabetes, Hypercholesterolemia | 2 | 0.23 | 95.66 |

| Hematuria/Urinary Tract Infection | 7 | 0.82 | 96.48 |

| Various Others (Asthma, Musculoskeletal pain, Erectile Dysfunction, Obesity, Weakness, Peptic Ulcer Disease, Gout) | 30 | 3.52 | 100.00 |

| Total | 852 | 100.00 |

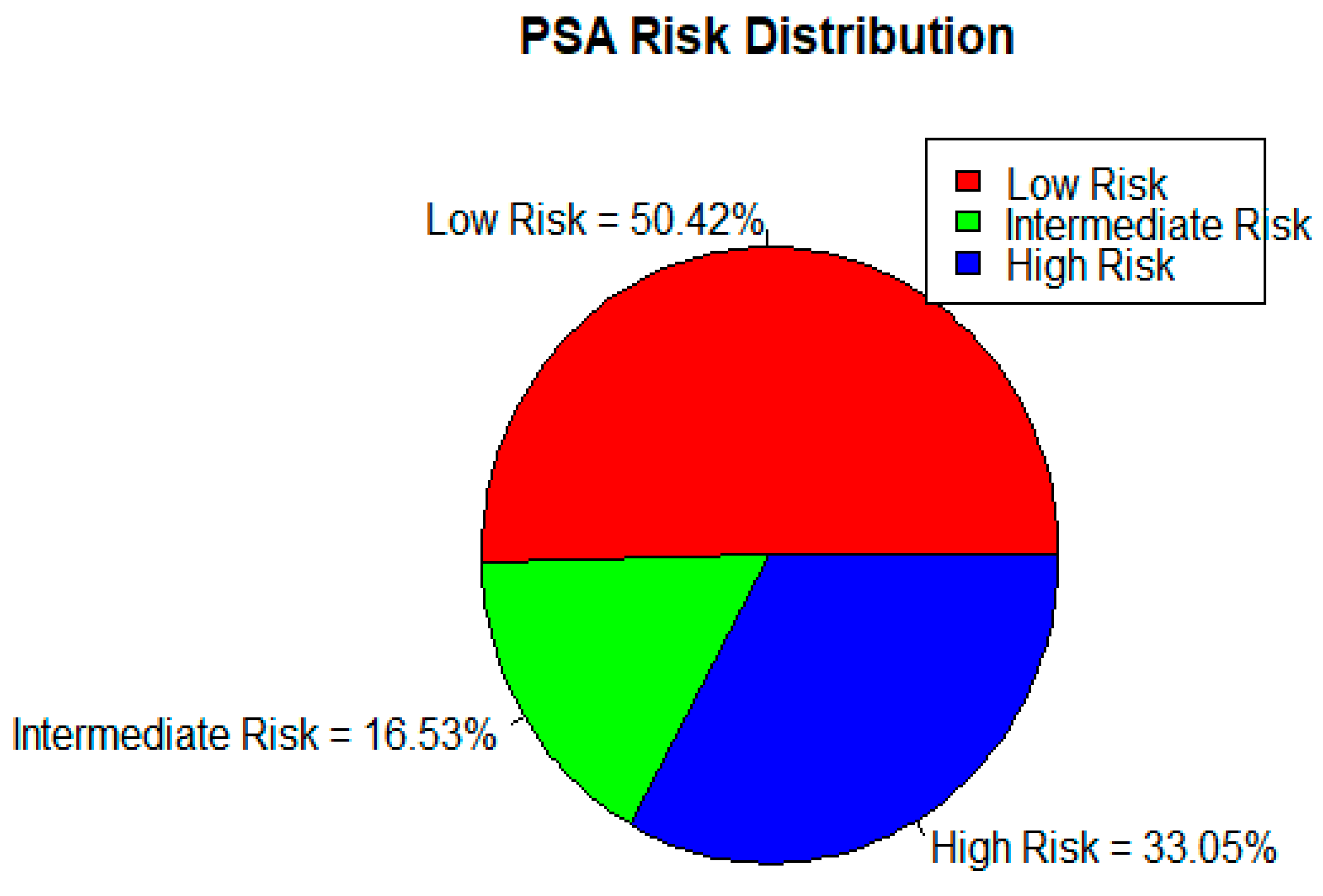

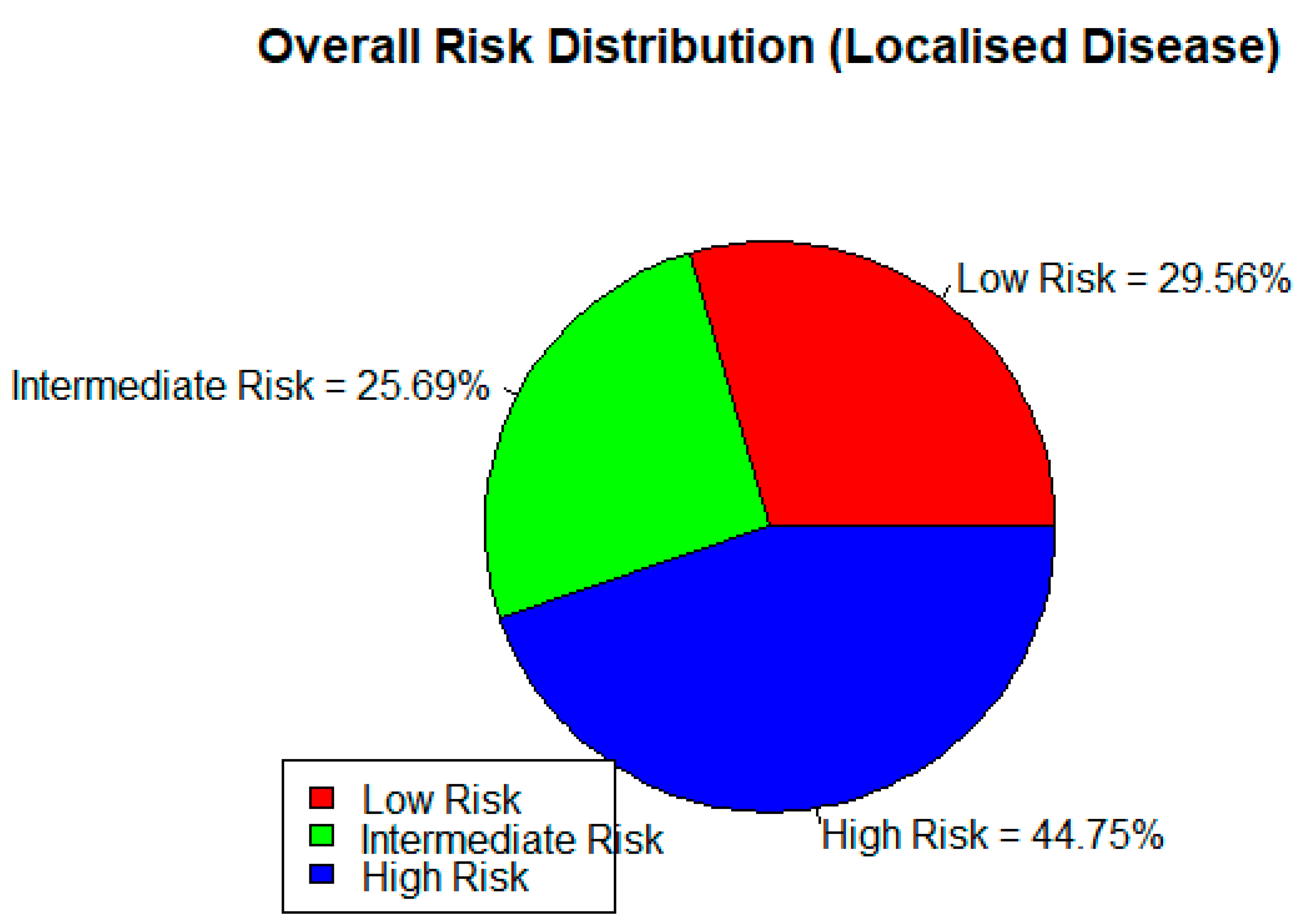

| DISEASE RISK STRATIFICATION BY PSA | ||||||||

| LOW RISK | INTERMEDIATE RISK | HIGH RISK | TOTAL | |||||

| 50.42% | 16.53% | 33.05% | 100% | |||||

| DISEASE RISK STRATIFICATION BY DRE | ||||||||

| LOW RISK | INTERMEDIATE RISK | HIGH RISK | TOTAL | |||||

| 53.19% | 17.38% | 29.43% | 100% | |||||

| ISUP GRADES DISTRIBUTION | ||||||||

| GRADE 1 | GRADE 2 | GRADE 3 | GRADE 4 | GRADE 5 | TOTAL | |||

| 19.13% | 21.48% | 19.50% | 20.58% | 19.31% | 100% | |||

| DISEASE RISK STRATIFICATION BY HISTOLOGY (GLEASON SCORE/ISUP) | ||||||||

| LOW RISK | INTERMEDIATE RISK | HIGH RISK | TOTAL | |||||

| 46.67% | 36.03% | 17.06% | 100% | |||||

| DISEASE TREATMENT; MODALITIES | ||||||||

| TYPE OF ADJUVANT/ALLIED THERAPY GIVEN TO THE PATIENTS | ||||||||

| NONE | BRACHY THERAPY |

CHEMO THERAPY |

CHEMO- RADIATION |

CHEMO and SURGERY |

GOLD SEEDS |

SURGERY MAIN; AND ALLIED |

TOTAL | |

| 65.12% | 3.72% | 8.85% | 0.18% | 3.54% | 4.07% | 14.52% | 100% | |

| TOTAL NUMBER OF ADJUVANT THERAPY GIVEN PER PATIENT | ||||||||

| None | One | Two | TOTAL | |||||

| 65.12% | 16.59% | 18.29% | 100% | |||||

| DISEASE TREATMENT OUTCOMES | ||||||||

| HIGHEST PSA PEAK DURING TREATMENT PERIOD; CATEGORISED (ng/ml) | ||||||||

| 10 or less | 10 to>100 | TOTAL | ||||||

| 8.33% | 91.67% | 100% | ||||||

| PSA RESOLUTION PER NUMBER TOTAL OF TREATMENT MODALITIES GIVEN (ng/ml- per modality given) | ||||||||

| <0.5 | 0.5 to 20 | >20 | TOTAL | |||||

| 41.78% | 26.76% | 31.96% | 100% | |||||

| LOWEST PSA ATTAINED DURING TREATMENT PERIOD (NADIR); CATEGORISED (ng/ml) | ||||||||

| <0.5 | 0.5 TO 4 | >4 | TOTAL | |||||

| 22.30% | 31.81% | 45.89% | 100% | |||||

| FAIL-PSA-REFRACTORY MULTIPLES (FAIL PSA DIVIDED BY LOWEST PSA) (ng/ml) | ||||||||

| <3 | 3.5 to 10 | 10.5 to 20 | 20.5 to 100 | >100 | TOTAL | |||

| 49.2% | 28.8% | 0.1% | 18.0% | 3.9% | 100% | |||

| Characteristic | Outcome | Test Statistic | p-value |

| Age (years) | PSA at diagnosis | Kruskal-Wallis | 0.003 |

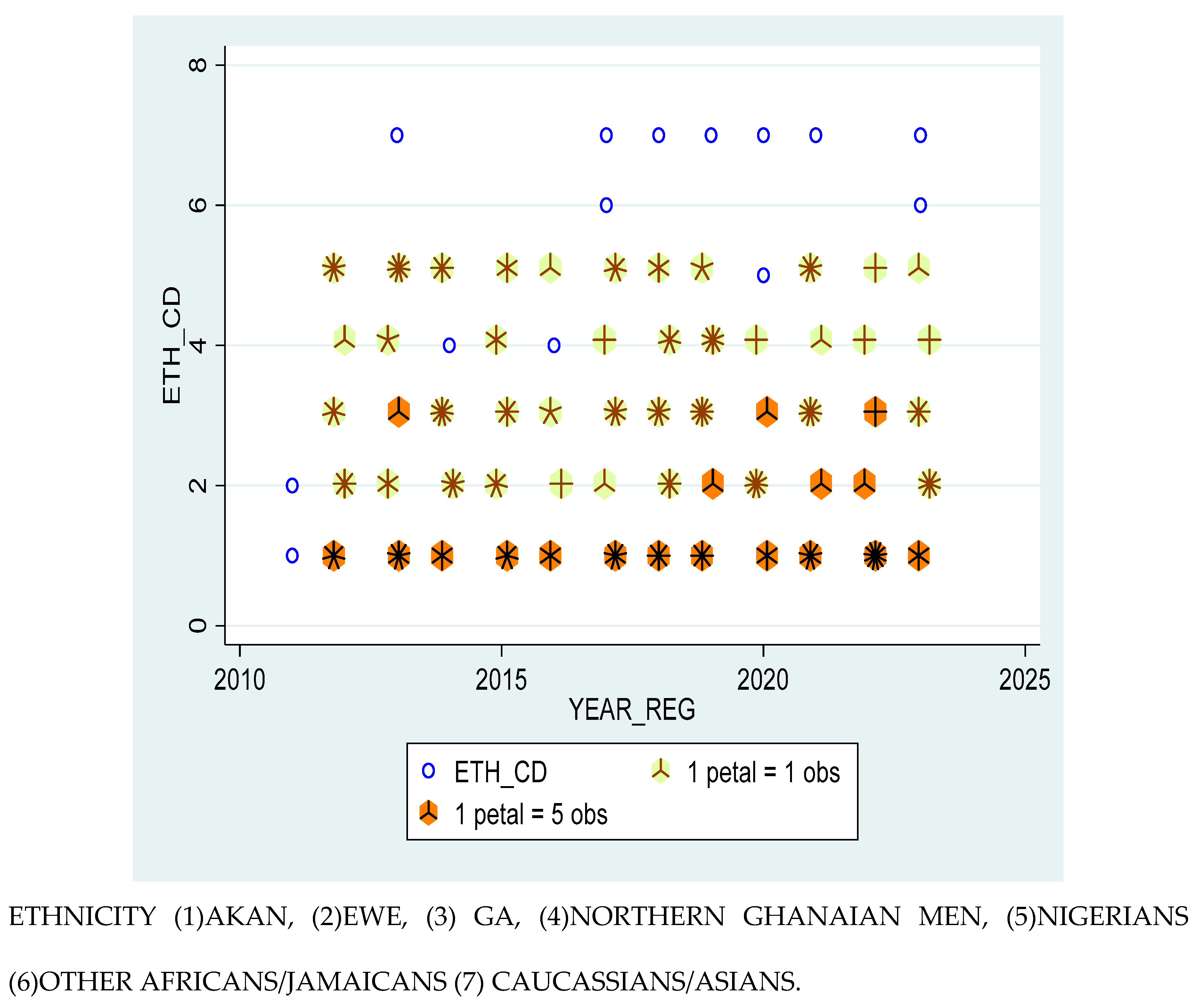

| Ethnicity | PSA at diagnosis | Kruskal-Wallis | 0.049 |

| Nationality | PSA at diagnosis | Kruskal-Wallis | 0.030 |

| Marital Status | PSA at diagnosis | Kruskal-Wallis | 0.001 |

| Age (years) | ISUP grade | Kruskal-Wallis | 0.009 |

| Ethnicity | ISUP grade | Kruskal-Wallis | 0.049 |

| Nationality | ISUP grade | Kruskal-Wallis | 0.030 |

| Nationality | Total number of Treatment modality | Chi-squared test | 0.030 |

| Comorbidity Status | Adjuvant treatment | Pearson’s Chi-squared | 0.001 |

| Age (years) | Toxicity | Wilcoxon rank-sum | 0.001 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Toxicity | Wilcoxon rank-sum | 0.034 |

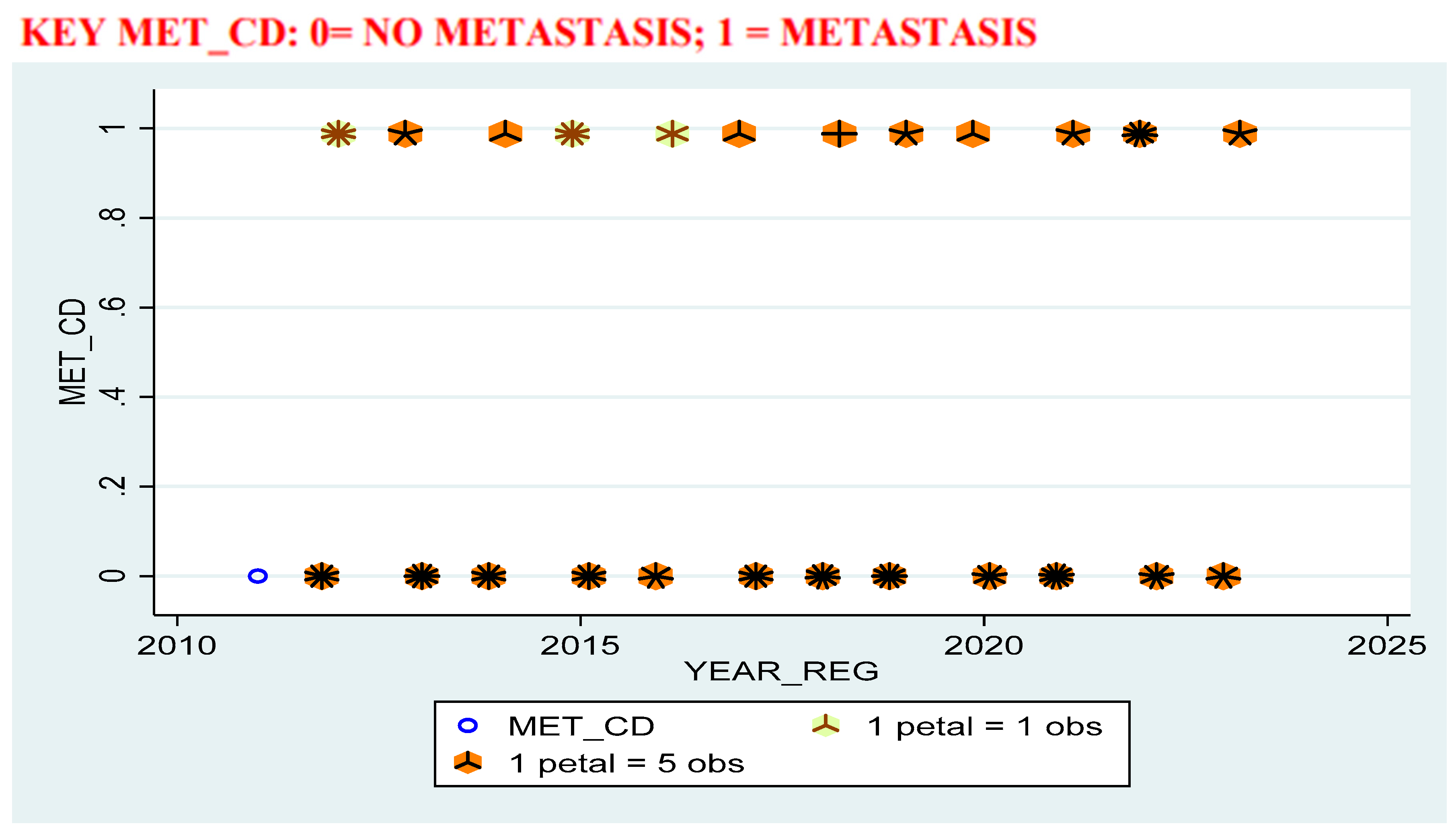

| High BMI | High-risk Localised Prostate Cancer | (OR) 2.34 | 0.022 |

| High BMI | Propensity to Metastatic Prostate Cancer | (OR) 0.35 | 0.026 |

| Ethnicity (Ga and Ewe vs. Akans) | High Risk Localised Prostate Cancer on DRE | (OR) 0.52 | 0.049 |

| Socio-economic Status | Prostate Cancer Disease | (OR) 3.3 | <0.01 |

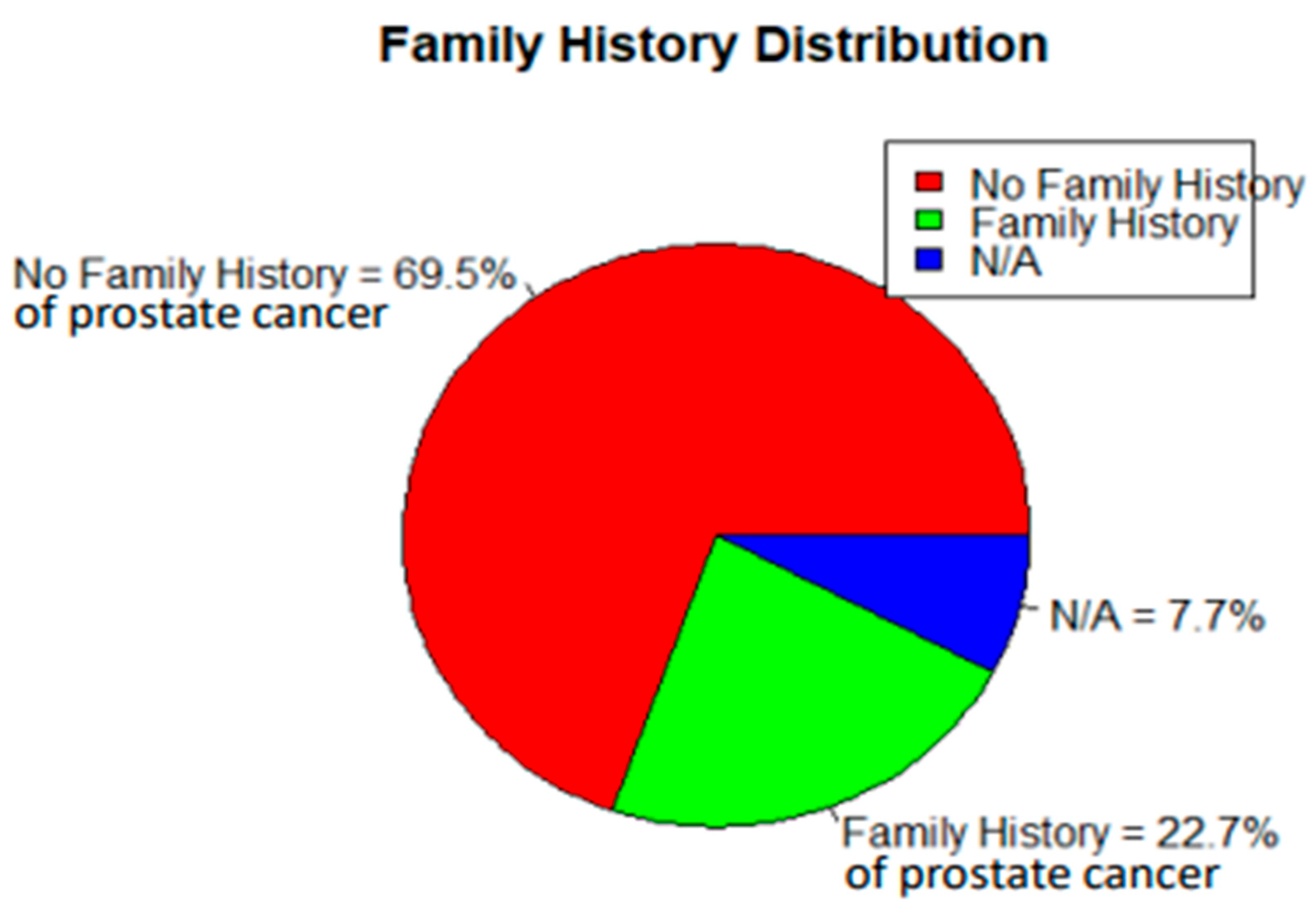

| Family History | Prostate Cancer Disease | (OR) 2.3 | <0.01 |

| CHI-QUARE: Variable | Chi2 | Dof | p-value | UNIVARIATE LOGISTIC REGRESSION: Variable | OR | CI Lower | CI Upper | Z | p-value | |

| ACT | 7.404548 | 3 | 0.060 | ACT | 0.887901 | 0.79468 | 0.992057 | -2.10087 | 0.035 | |

| AGE_CD | 277.1374 | 5 | <0.001 | AGE_CD | 2.122956 | 1.912975 | 2.355985 | 14.16693 | <0.001 | |

| ALC | 5.445207 | 2 | <0.001 | ALC | 0.810723 | 0.661849 | 0.993085 | -2.027 | 0.042 | |

| BMI_CD | 48.35092 | 4 | <0.001 | BMI_CD | 1.045975 | 0.950214 | 1.151386 | 0.917529 | 0.359 | |

| ETH_CD | 97.83927 | 6 | <0.001 | ETH_CD | 0.799188 | 0.749586 | 0.852072 | -6.85672 | <0.001 | |

| FMH | 34.5831 | 2 | <0.001 | FMH | 2.18415 | 1.676112 | 2.846176 | 5.783486 | <0.001 | |

| H | 209.0936 | 48 | <0.001 | H | 0.977944 | 0.904855 | 1.056935 | -0.56276 | 0.574 | |

| LIN_CD | 64.04639 | 5 | <0.001 | LIN_CD | 1.250279 | 1.112893 | 1.404625 | 3.760964 | 0.0002 | |

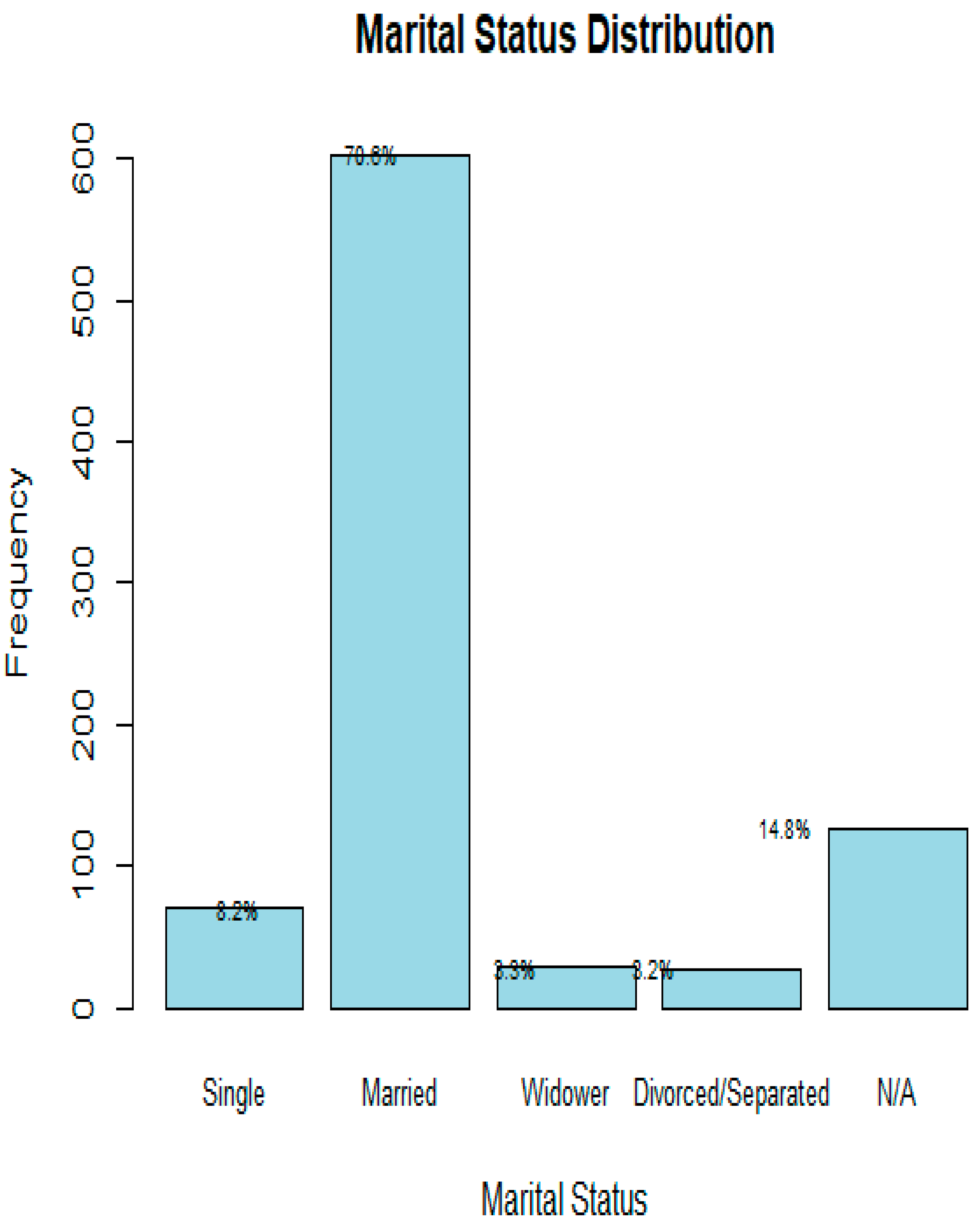

| MAR_CD | 955.2117 | 4 | <0.001 | MAR_CD | 1.72774 | 1.576975 | 1.892919 | 11.7379 | <0.001 | |

| PND_CD | 53.58187 | 5 | <0.001 | PSA | 1.024192 | 1.01424 | 1.034242 | 4.798184 | <0.001 | |

| PSA | 881.8912 | 294 | <0.001 | SES | 1.591092 | 1.420385 | 1.782315 | 8.020344 | <0.001 | |

| SES | 356.3435 | 3 | <0.001 | TBC | 0.371965 | 0.276924 | 0.499624 | -6.5693 | <0.001 | |

| TBC | 44.56501 | 1 | <0.001 | W | 1.007744 | 1.000935 | 1.014599 | 2.229992 | 0.026 | |

| W | 769.7882 | 316 | <0.001 | |||||||

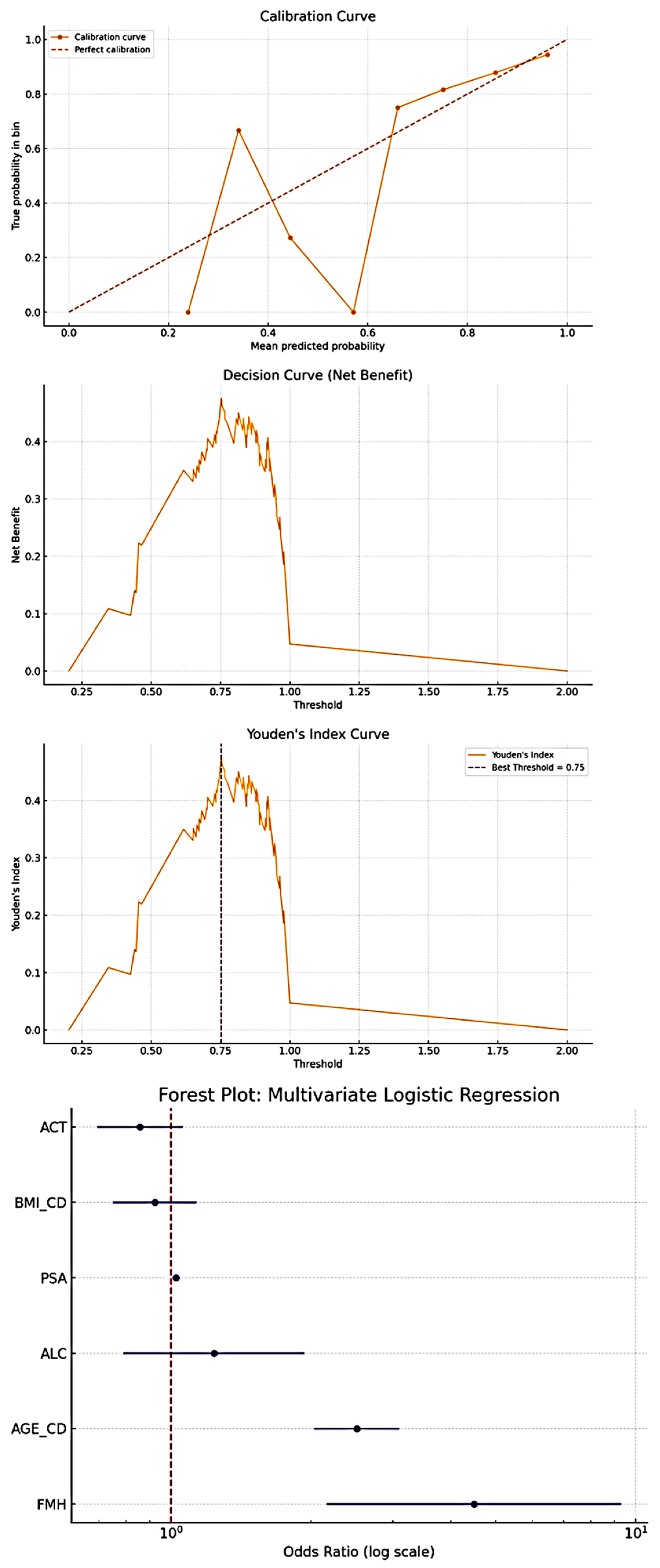

| Multivariate Logistic Regression: | ||||||||||

| Variable | OR | CI Lower | CI Upper | z | p-value | |||||

| const | 0.159355 | 0.055841 | 0.454756 | -3.43279 | 0.000597 | |||||

| AGE_CD | 2.510028 | 2.032442 | 3.099838 | 8.546282 | <0.001 | |||||

| BMI_CD | 0.922045 | 0.750286 | 1.133123 | -0.77168 | 0.440304 | |||||

| FMH | 4.48667 | 2.164282 | 9.301103 | 4.035711 | <0.001 | |||||

| ACT | 0.857443 | 0.693877 | 1.059565 | -1.4242 | 0.15439 | |||||

| ALC | 1.236622 | 0.790181 | 1.935296 | 0.929418 | 0.352672 | |||||

| PSA | 1.024192 | 1.01424 | 1.034242 | 4.798184 | <0.001 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).