Introduction

Globally, the electrification of road transport has emerged as a critical pathway for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, improving energy security, and lowering dependence on volatile fossil fuel imports [

1,

2,

3]. In Sub-Saharan Africa, these imperatives are particularly acute given the region’s exposure to fuel price volatility, foreign currency constraints, and rapidly growing urban transport demand [

4]. For Zambia, transitioning to electric mobility aligns directly with national climate commitments, energy-transition objectives, and the need to shield households and firms from fuel-cost shocks [

5,

6].

Two dominant architectures currently define EV energy replenishment: conventional plug-in charging, which includes Level 1 and Level 2 AC charging and DC fast charging, and battery swapping, which allows depleted traction batteries to be replaced with fully charged units in under five minutes [

7,

8]. While charging remains foundational to universal access, battery swapping offers advantages in high-utilization applications such as ride-hailing, public transport, and commercial delivery fleets, where downtime has significant economic implications [

9].

The current global debate highlights trade-offs between the higher capital cost and operational complexity of battery swapping and the lower resilience and fleet uptime of charging-only infrastructure [

10,

11,

12]. Diverging hypotheses remain on the optimal mix for emerging markets: some argue that low-cost charging networks are best suited for early adoption, while others emphasize the long-term operational efficiency and grid benefits of integrating battery swapping [

13,14].

This study addresses these competing perspectives by comparing a dual “Battery Swapping + Charging” model with a “Charging-Only” model in Zambia’s context, assessing infrastructure cost, standardization, operational economics, safety, grid integration, environmental impact, consumer acceptance, and fleet uptime. The principal conclusion is that a phased, standards-led rollout of the dual model in high-utilization corridors—while retaining charging-only access for households—offers the strongest balance of resilience, inclusivity, and job creation for Zambia’s EV transition.

Materials and Methods

This study employed a comparative, multi-criteria assessment framework to evaluate two dominant electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure pathways in the Zambian context: the dual “Battery Swapping + Charging” model and the “Charging-Only” model. The analysis integrated qualitative and quantitative data drawn from published literature, international benchmarks, and Sub-Saharan Africa case studies, supplemented with Zambia-specific regulatory, economic, and infrastructure considerations.

Key parameters assessed included infrastructure cost, battery standardization requirements, technology lock-in risk, operating economics, safety, grid integration, environmental footprint, consumer acceptance, total cost of ownership, second-hand market compatibility, security, operational complexity, fleet uptime, and job creation potential. Sources included peer-reviewed journals, industry reports, and policy documents, with emphasis on findings from comparable high-utilization fleet use cases in Sub-Saharan Africa, China, and other emerging markets.

Comparative evaluation was conducted using a matrix-based scoring approach to capture trade-offs across stakeholder priorities. Zambia-specific context was incorporated by referencing national energy policy frameworks, fiscal incentives, and existing forecourt infrastructure data. The methodological framework ensured that findings are evidence-based, reproducible, and directly applicable to infrastructure investment and policy planning in Zambia’s mobility transition.

Defining the Choice Facing Zambia

This article contrasts a dual “Swapping + Charging” model with a “Charging-Only” model across infrastructure cost, standardization, technology lock-in, operations, risk and safety, grid integration, environmental footprint, market compatibility, security, and fleet uptime. In brief, the dual model requires higher capital expenditure and tighter standards but delivers greater resilience and fleet uptime, while the Charging-Only model is simpler and cheaper to deploy initially, though uptime is constrained by charging dwell times. Comparison of Swapping. Capital needs diverge because dual sites must build both swap bays and charging capacity, making them most viable in high-demand urban or fleet corridors where utilization supports the investment. Scaling battery swapping further hinges on battery-pack standardization—beyond plug and connector standards—so regulators would need to convene industry to agree on common pack formats, telemetry, and diagnostic requirements. Finally, the dual pathway reduces technology lock-in by preserving conventional charging as a fallback while chemistries and pack architectures evolve. Also, If standards are established and implemented, the swapping system can offer remarkable efficiency and user convenience (Simwaba, 2025).

Operating Economics, Battery-as-a-Service, and Fleet Use Case

Operating costs are higher for integrated swapping-and-charging sites because they must finance and manage a circulating battery inventory in addition to electricity purchases and site operations and maintenance (O&M). However, by bulk-charging pooled batteries during off-peak hours and offering Battery-as-a-Service (BaaS), these sites can improve unit economics in dense-use cases such as taxis, logistics, and corporate or campus fleets. By contrast, Charging-Only stations concentrate costs primarily in electricity and site maintenance and entail lower operational complexity. These patterns are consistent with operations-research findings that station siting, layout, and repairable-inventory control are central drivers of cost and service levels as volumes scale (Gull, M. S., 2025; Qi et al., 2023).

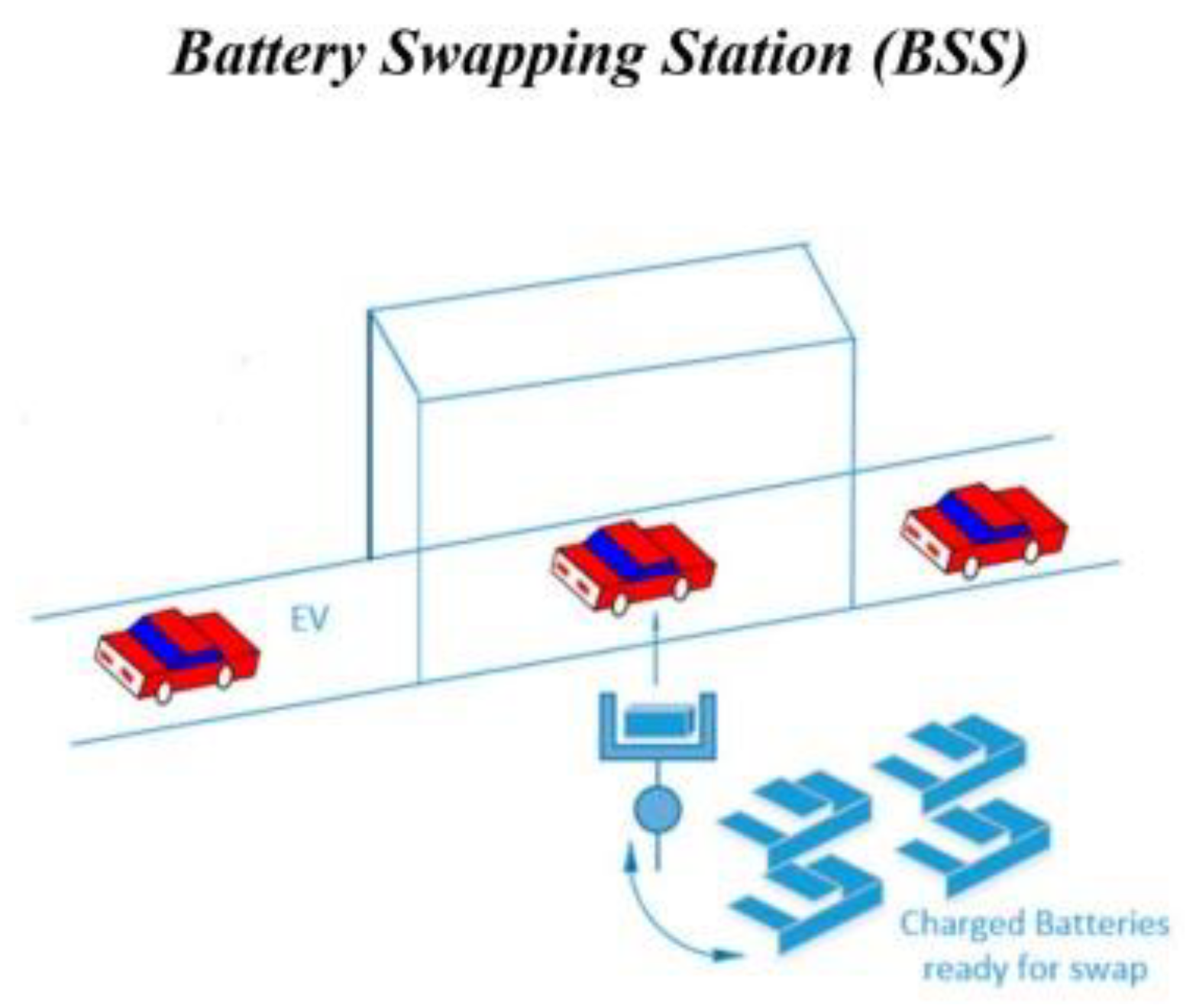

Figure 1.

Illustrates a conceptual diagram of electric vehicles (EVs) positioned at aBattery Swapping Station (BSS), ready to engage in the battery exchange process. Battery Swapping Station (BSS). Source: Adegbohun, F., von Jouanne, A., & Lee, K. Y. (2019). Autonomous battery swapping system and methodologies of electric vehicles. Energies, 12(4), 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12040667.

Figure 1.

Illustrates a conceptual diagram of electric vehicles (EVs) positioned at aBattery Swapping Station (BSS), ready to engage in the battery exchange process. Battery Swapping Station (BSS). Source: Adegbohun, F., von Jouanne, A., & Lee, K. Y. (2019). Autonomous battery swapping system and methodologies of electric vehicles. Energies, 12(4), 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12040667.

Table 1.

Provides a high-level comparison of key technical and operational parameters across four major EV energy replenishment methods: battery swapping, Level 1 and Level 2 AC charging, and DC fast charging. It highlights differences in replenishment time, power output, infrastructure cost, grid impact, ideal use cases, and technical challenges. Comparison of key technical and operational parameters across four major EV energy replenishment methods (Simwaba, D, 2025).

Table 1.

Provides a high-level comparison of key technical and operational parameters across four major EV energy replenishment methods: battery swapping, Level 1 and Level 2 AC charging, and DC fast charging. It highlights differences in replenishment time, power output, infrastructure cost, grid impact, ideal use cases, and technical challenges. Comparison of key technical and operational parameters across four major EV energy replenishment methods (Simwaba, D, 2025).

| Parameter |

Battery swapping |

Level 1 ac charging |

Level 2 ac charging |

DC fast charging (level 3) |

| Average Replenishment Time |

3–5 min |

40–50 h for a full charge |

4–10 h for a full charge |

20 min to 1 h for an 80 % charge |

| Typical Power Output |

N/A (focus on speed of swap) |

1.4 kW − 1.9 kW |

3 kW − 19.2 kW |

50 kW − 350 kW+ |

| Estimated Infrastructure Cost per unit/station |

High initial investment (approx. $500,000 + per station) |

Low ($300 − $600 for the unit, plus potential installation costs) |

Moderate ($400 − $6,500 for the unit, plus installation) |

High to Very High ($30,000 − $140,000 + per unit, plus installation) |

| Grid Impact |

Medium to High (Centralized high-power charging of multiple batteries) |

Low (Similar to a standard household appliance) |

Medium (Can increase local transformer load, especially with multiple units) |

High (Significant strain on local grid infrastructure, often requiring dedicated substations) |

| Ideal Use Case |

Fleet operations, taxis, ride-sharing, users valuing speed and convenience over home charging |

Overnight home charging, workplace charging where long dwell times are common |

Home charging, public top-up locations (shopping centers, etc.), workplaces |

Highway corridors, dedicated public charging hubs, commercial fleets with high daily mileage |

| Key Technical Challenges |

Battery standardization, high initial capital investment, complex logistics and inventory management, interoperability between vehicle brands. |

Very slow charging speed, limited to adding minimal range per hour, may not be sufficient for users with high daily mileage. |

Requires professional installation, potential need for home electrical panel upgrades, fragmentation of charging networks and payment systems. |

High infrastructure and installation costs, significant grid impact and demand charges, potential for accelerated battery degradation with frequent use, connector compatibility issues. |

Battery-as-a-Service and Operational Models in Africa: Electric Motorcycle Use Case

Expanding on earlier discussion, Battery-as-a-Service (BaaS) models have gained traction through the deployment of battery swapping kiosks, particularly for electric two- and three-wheelers. Systems like the KOFA-branded stations in Africa enable riders to exchange depleted portable batteries for fully charged ones in under five minutes. This model is especially impactful for informal and commercial users who depend on operational continuity for daily income. Instead of owning the battery, users subscribe to a service, reducing upfront costs and shifting maintenance responsibilities to the operator (Khan et al., 2025).

Figure 2.

Battery swapping station for electric motorcycles in Africa. The KOFA-branded kiosk holds an array of swappable battery packs; riders dock their depleted unit and retrieve a charged one in minutes, reducing downtime while supporting a managed lifecycle. Source:https://www.tycorun.com/blogs/news/top-10-battery-swap-station-companies-in-africa?srsltid=AfmBOoqtOXjmLvjnw5dI57wGVP_Wt2t2OWw5JCu2Ktn6eMaXdz7mdJlK.

Figure 2.

Battery swapping station for electric motorcycles in Africa. The KOFA-branded kiosk holds an array of swappable battery packs; riders dock their depleted unit and retrieve a charged one in minutes, reducing downtime while supporting a managed lifecycle. Source:https://www.tycorun.com/blogs/news/top-10-battery-swap-station-companies-in-africa?srsltid=AfmBOoqtOXjmLvjnw5dI57wGVP_Wt2t2OWw5JCu2Ktn6eMaXdz7mdJlK.

Risk Allocation, Safety, and Service Integrity

A dual model splits battery-management liability: operators are accountable for the health, safety, and performance of swapped packs, while users remain responsible for the care and charging of their own permanently installed batteries, where applicable. Under Charging-Only, the owner bears the full degradation and safety risk (absent specific warranties or insurance), including risks arising from poor charging habits or inadequate maintenance. Centralized inspection, testing, and telemetry at swap depots can reduce incidents; however, mechanical alignment during swaps introduces a distinct risk that must be controlled with strict Standard Operating Procedures(SOPs), tooling, and Quality Assurance(QA) protocols. Comparative reviews of global swap ecosystems echo that standardized diagnostics and handling procedures are critical to safety and user trust (Hussain et al., 2024; Feng & Lu, 2021).

Grid Integration and Environmental Considerations

Because swap pools can be charged off-peak (and potentially co-sited with storage and PV), dual sites offer a flexible demand profile that can ease stress on constrained feeders; unmanaged fast-charging, by contrast, risks exacerbating peaks. For Zambia, where certain urban nodes are constrained, this “virtual buffering” capability is appealing while grid reinforcement proceeds (Dioha et al., 2022). Environmental trade-offs differ: swapping implies a larger circulating battery pool, increasing the importance of second-life and recycling policy; Charging-Only avoids that additional stock. Regional transition analyses recommend pairing depot charging with renewable generation and smart-charging strategies to shrink lifecycle emissions as the grid greens (Conzade et al., 2024).

Consumer Acceptance, Total Cost of Ownership (TCO), and the Second-Hand Market

Choice tends to raise acceptance, when drivers can either swap for speed or charge for convenience and cost, EV adoption resistance falls. Total cost of ownership is use-case dependent. The dual model often favors high-mileage fleets that monetize uptime, whereas home AC charging remains the least-cost pathway for low-mileage private users. In Zambia and the broader region, second-hand imports play a large role in fleet composition (Simwaba, D, 2025); Charging-Only is universally compatible, while swapping may require retrofits on vehicles not designed for a compatible pack architecture, a consideration highlighted in the matrix (Table 2 below) and consistent with African import dynamics (Simwaba, D, 2025; Ayetor et al., 2021). Adoption-intention studies specific to battery swapping further show that perceived relative advantage and compatibility are decisive for uptake (Adu-Gyamfi et al., 2021; Rogers, 2003).

Security, Operational Complexity, and Resilience

Dual sites must secure both battery inventory and charging assets, raising site-security requirements relative to the cable-focused risks of Charging-Only. Operationally, managing two service systems is more complex, but the model offers built-in resilience: if swap station equipment is temporarily down, drivers can still charge on-site; if grid constraints slow charging, pre-charged batteries can keep vehicles moving. This redundancy underpins the consistently higher fleet uptime highlighted in the matrix (Table 2 below) for taxis, buses, and logistics operations.

Discussion: Implementation Pathway Tailored to Zambia

A Summary Table Comparison of EV Battery Swapping + Charging Model vs Charging-Only Model.

| Aspect |

Swapping + Charging Model |

Charging-Only Model |

Key Notes (Zambia Context) |

| Infrastructure Cost |

High – swap bays + chargers; higher capex. |

Medium – mostly DC fast + AC chargers. |

Dual model offers resilience but requires strong investment; best suited to high-demand urban/fleet areas. |

| Battery Standardization Need |

High – needed for swapping; charging side unaffected. |

Low – only charging connector standard needed. |

ERB will need to push battery pack standards if swapping scales. |

| Technology Lock-In Risk |

Medium – mitigated by having a charging option, therefore battery pack tech can be upgraded in future models. |

Low – Adapt easily to new standards. |

Dual model reduces lock-in risk because charging provides a fallback. |

| Operating Costs |

High – inventory + electricity + site maintenance.

+ charging ops; but can optimize with off-peak charging. |

Medium – Mainly electricity + site maintenance. |

BaaS model can improve ROI for high-utilization fleets and the due model is likely to be profitable in the long run. |

| Battery Management System Liability |

Responsibility is split— the operator is accountable for the health, safety, and performance of batteries provided through swapping, while the user is responsible for proper care and charging of their own permanently installed battery (if applicable). |

Responsibility is entirely user-side — the owner bears full degradation risk (when uninsured) and safety risk, including issues from poor charging habits or lack of battery maintenance. |

Dual model shares risk between operator and user. — swapping reduces user exposure to degradation risks, while charging ensures users retain control over their own battery when they prefer. |

| Safety (Battery Health) |

Higher – swapped batteries inspected; charging depends on owner care. |

Lower – no centralized inspection. |

Centralized checks via swapping can reduce incidents. |

| Vehicle Damage Risk During Service |

High – risk from mechanical alignment in swaps; charging side minimal. |

Minimal |

Needs strict safety protocols for swap operations. |

| Grid Impact |

Lower – swaps can bulk-charge off-peak; chargers managed via smart grid. Can provide grid support. |

Higher – DC fast charging can create peak loads (grid pressure). |

Dual model allows load balancing and storage integration.With bidirectional inverters, the station can charge packs when power is cheap/abundant (e.g., midday solar or off-peak) and discharge to the facility or grid at peak, delivering peak-shaving, load-shifting, frequency support, backup power, and microgrid services. Degraded “B-grade” packs can be reserved for stationary use, while “A-grade” packs serve vehicles. Smart scheduling (State of Charge/State of Health tracking + tariff signals) optimizes revenue and battery health. |

| Coverage & Accessibility |

High – can serve both swap-compatible and standard EVs. |

High – any EV can charge. |

Dual model avoids excluding non-standard EVs. |

| Environmental Footprint |

Medium – more batteries in rotation; mitigated by renewables. |

Low – no spare battery pool. |

Requires strong recycling/second-life battery policy. |

| Consumer Acceptance |

Higher – choice of swap or charge. |

High – familiar system. |

Flexibility reduces adoption resistance. |

| TCO (Total Cost of Ownership) |

Variable – lower for high-use fleets; neutral for casual drivers. |

Lowest for home AC charging. |

Dual model benefits fleets, may be neutral for private low-mileage users. |

| Second-Hand EV Market Compatibility |

Medium–High – can charge any EV; swap only if compatible. |

Medium – any EV can charge, but the lack of swapping options may affect Second-Hand EV Market Compatibility. |

Helps imports but may require retrofits for swap especially for EVs without swapping infrastructure. |

| Security & Theft Risks |

High – batteries + charging cables need protection. |

Medium – mostly cable theft. |

Needs strict site security measures. |

| Operational Complexity |

High – dual systems to manage. |

Low – simpler to run. |

The two service methods (swapping and charging), if one system goes down, the other can still serve customers:

If the swap equipment fails, drivers can still charge their EVs on-site.

If grid constraints slow charging, pre-charged batteries in the swap inventory can keep vehicles moving. |

| Fleet Uptime |

Highest – instant swaps + top-up charging. |

Medium – dependent on charging time. |

Dual model maximizes uptime for taxis, buses, and logistics fleets. |

| Job impact |

High job creation per site - swap attendants and supervisors, battery logistics and diagnostics, inventory planning, safety and quality control, BaaS customer operations, refurbishment/second-life and recycling roles. Strong pathway to redeploy OMC forecourt staff into swap operations with targeted upskilling. |

|

Moderate job creation - electricians and civil/Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing (MEP) installers, charger maintenance, network monitoring, site operations. OMCs can repurpose forecourts as charging plazas, but with fewer battery-handling roles than swapping. |

An investable pathway emerges from the evidence. Zambia can move early on standards: beyond open charging connectors, define minimum swap-pack specifications and a common data/telemetry schema to ensure safety, interoperability, and bankability. To convert standards into jobs, embed occupational standards and certification pathways so technicians can qualify for EV battery diagnostics, swap operations, charger installation, and safety audits through TEVETA-aligned programs and Energy Regulation Board(ERB)/Zambia Bureau of Standards(ZABS) certification. Current motor service station companies can participate in standards pilots at selected forecourts, accelerating workforce upskilling while de-risking compliance for future sites.

Zambia can also pursue fleet-led pilots where duty cycles are predictable and uptime monetized—ride-hailing, delivery, public transport, mines, campuses, and estates—so that trialability (ease of testing through small pilots) and observability (how easily stakeholders observe the real-world cases, challenges and benefits from other countries) to accelerate the diffusion of innovation (Qi et al., 2023; Rogers, 2003). Each pilot should include a workforce transition plan: short courses for swap attendants and battery handlers; cross-training for existing service station forecourt staff into e-mobility roles; and structured placements for graduates to build a technician pipeline. Where pilots are Charging-Only, prioritize installer and field-service micro-enterprises to stimulate MSME job creation in peri-urban and rural areas.

Site infrastructure on feeders with headroom, can use off-peak charging for swap pools, and integrate distributed PV and storage where viable to smooth demand and reduce emissions intensity (Dioha et al., 2022; Conzade et al., 2024). Grid-smart siting doubles as a jobs program: local EPC firms, electricians, and civil/MEP contractors can be engaged through OMC-hosted conversions of existing service stations into e-mobility hubs, while OEMs and operators commit to local maintenance depots and telemetry support centers.

We can implement extended-producer-responsibility rules and accredited second-life/recycling channels to address the larger circulating battery stock characteristic of swap ecosystems. This is a direct employment lever: formal refurbishment, second-life integration (stationary storage), and recycling facilities create skilled and semi-skilled jobs and offer service station businesses and independent operators a revenue diversification pathway into energy transition and circular-economy services linked to their forecourt networks.

Regulators can support the second-hand market by publishing clear retrofit guidance and homologation steps for swap compatibility while protecting buyers of standard plug-in vehicles (Ayetor et al., 2021). Retrofit protocols can be paired with accredited local workshops, creating technician jobs in diagnostics, harnessing, enclosure adaptation, and Battery Management Systems (BMS) calibration.

Finally, align fiscal levers—VAT/duty relief for certified components, stations, and safety systems—to de-risk early projects, consistent with Zambia’s budget posture toward clean-technology enablers (PKF Zambia, 2024). Fiscal policy should explicitly recognize workforce formation: tax credits or training rebates for firms that convert forecourts, certify technicians, and achieve placement targets; concessional finance that scores local jobs, technician certification, and service station participation as part of viability-gap support.

Conclusions

For Zambia’s climate-aligned mobility transition, a phased, standards-led, fleet-first program that deploys a dual EV Battery Swapping + Charging model in high-utilization corridors, while preserving broad Charging-Only access for households and low-mileage users—offers the strongest balance of resilience, grid friendliness, consumer protection, market inclusivity, and job creation. The Zambia-specific comparative evidence consistently indicates higher uptime, better load-management options, and reduced technology lock-in for the dual model, provided that standards, safety protocols, and second-life frameworks are established from the outset. Coupling these technical measures with a service station transition program—repurposing forecourts as e-mobility hubs, credentialing existing staff, and seeding refurbishment/recycling capacity—turns infrastructure investment into a durable employment engine. With targeted incentives and grid-smart siting, early diffusion among motorcycle taxis, couriers, and fleet operators can proceed quickly, ensuring that electrification contributes meaningfully to emissions reductions, energy security, and high-quality green jobs in Zambia.

Patents

No patents have resulted from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S.; methodology, D.S.; formal analysis, D.S.; investigation, D.S.; resources, D.S.; data curation, D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.; writing—review and editing, D.S.; visualization, D.S.; supervision, D.S.; project administration, D.S. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (UNZABREC), protocol code REF. No. 5983-2024, approval date: 29 November 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from subjects involved or mentioned in the study. When interacting with key stakeholders, formal letters were drafted and sent to secure their consent prior to participation.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. No new publicly archived datasets were generated.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges participating stakeholders for their time and insights, as well as to the University of Zambia for providing the ethical clearance necessary to undertake this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC |

Alternating Current |

| BaaS |

Battery-as-a-Service |

| BMS |

Battery Management System |

| BSS |

Battery Swapping Station |

| DC |

Direct Current |

| DoS |

Depth of Discharge |

| ERB |

Energy Regulation Board |

| EV |

Electric Vehicle |

| O&M |

Operations and Maintenance |

| OMC |

Oil Marketing Company |

| PV |

Photovoltaic |

| QA |

Quality Assurance |

| SOPs |

Standard Operating Procedures |

| SoC |

State of Charge |

| SoH |

State of Health |

| TCO |

Total Cost of Ownership |

| TEVETA |

Technical Education, Vocational and Entrepreneurship Training Authority |

| ZABS |

Zambia Bureau of Standards |

References

- Conzade, J.; et al. Power to Move: Accelerating the Electric Transport Transition in Sub-Saharan Africa; McKinsey & Company: 2024. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/power-to-move-accelerating-the-electric-transport-transition-in-sub-saharan-africa.

- Dioha, M.; et al. Guiding the deployment of electric vehicles in the developing world. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 071001. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361159605_Guiding_the_deployment_of_electric_vehicles_in_the_developing_world. [CrossRef]

- PKF Zambia. 2024 Budget & Tax Highlights; PKF Zambia: Lusaka, Zambia, 2024. https://www.pkf-zambia.co.zm/media/s5spiigb/pkf-zambia-2024-budget-tax-highlights.pdf.

- Ayetor, G.K.; Mbonigaba, I.; Sackey, M.N.; Andoh, P.Y. Vehicle regulations in Africa: Impact on used vehicle import and new vehicle sales. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 10, 100384. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590198221000919. [CrossRef]

- Simwaba, D.; Qutieshat, A. The potential of EV battery-swapping in developing countries: China’s use case as a baseline for Sub-Saharan Africa. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 32, 101505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- NIO. NIO Power: The Future of Charging. Available online: https://www.nio.com/nio-power (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Adegbohun, F.; von Jouanne, A.; Lee, K.Y. Autonomous battery swapping system and methodologies of electric vehicles. Energies 2019, 12, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Burghout, W.; Cats, O.; Jenelius, E.; Cebecauer, M. Charge-on-the-move solutions for future mobility: A review of current and future prospects. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 29, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, M. S., Ahmed, I., Khalid, M., & Arshad, N. (2025). Design and optimization of electric vehicle battery swapping stations with integrated storage for enhanced efficiency. Journal of Energy Storage, 129, 117211. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Lu, X. Construction planning and operation of battery swapping stations for electric vehicles: A literature review. Energies 2021, 14, 8202. https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/14/24/8202. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; et al. A comprehensive review on electric vehicle battery swapping stations. In Innovations in Electrical and Electronic Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 317–332. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377759162_A_Comprehensive_Review_on_Electric_Vehicle_Battery_Swapping_Stations. [CrossRef]

- Adu-Gyamfi, G.; et al. Who will adopt? Investigating the adoption intention for battery swap technology for electric vehicles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 136, 111979. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356842443_Who_will_adopt_Investigating_the_adoption_intention_for_battery_swap_technology_for_electric_vehicles. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).