Submitted:

17 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Acronyms and Notation

Operator Framework

Study Design

Metrics

Cycle Execution

Statistical Analysis

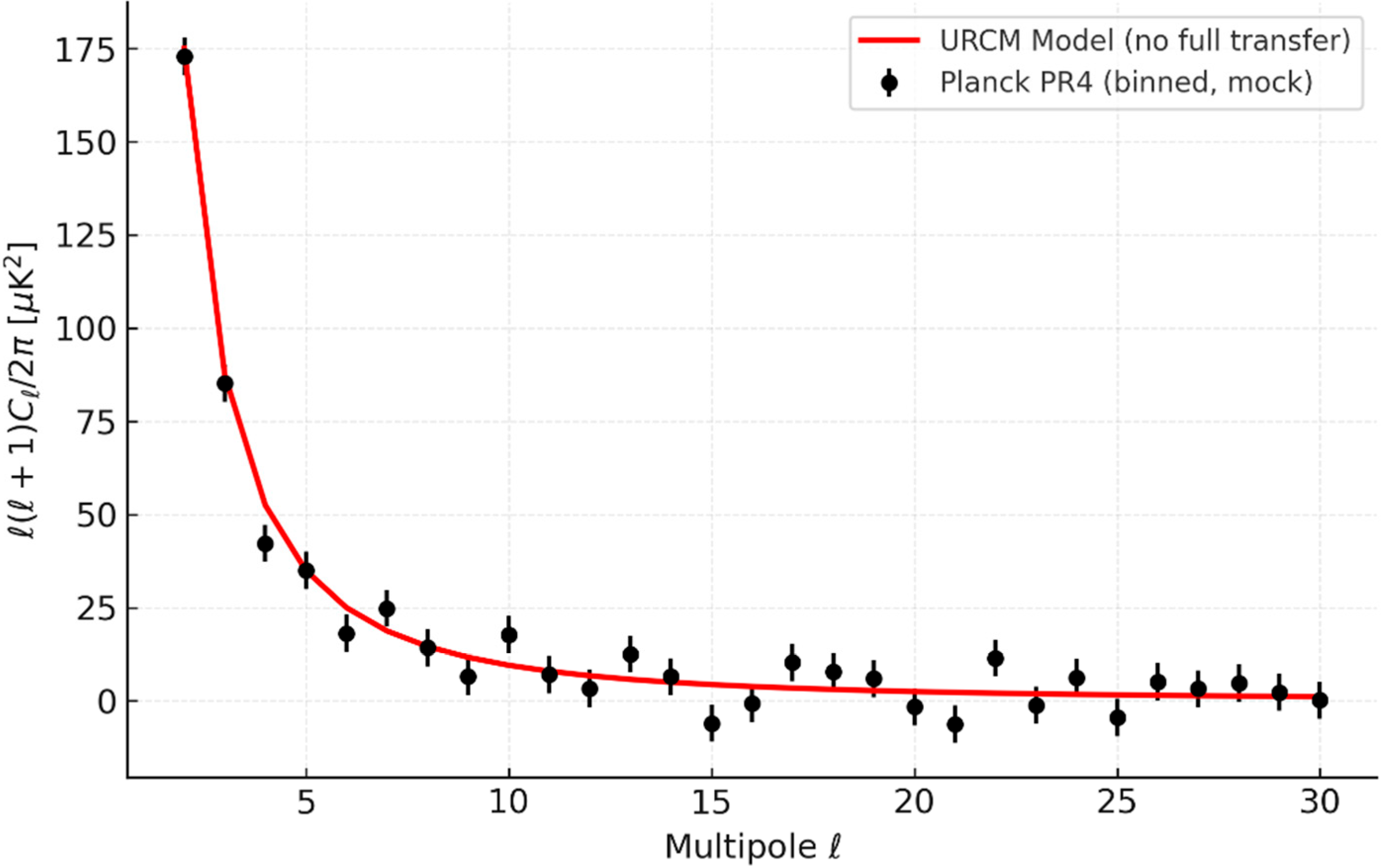

Forward Model Plan

- Generates synthetic power spectra directly from our reduced-space operators.

- Compares only qualitatively to Planck PR4 binned spectra.

- Start from our URCM initial conditions / parameter outputs.

-

Feed them into CAMB or CLASS to compute:

- ◦

- Cℓ^{TT}, Cℓ^{TE}, Cℓ^{EE} with all ΛCDM physics replaced or modified according to URCM.

- ◦

- Include transfer functions, gravitational lensing, reionization, beam/sky mask effects.

- Output spectra in exact same space as Planck / ACT / WMAP likelihoods.

- Allow a likelihood analysis (χ², Bayesian evidence) rather than heuristic visual matching

Technical Implementation

Data, and Resource Disclosures

AI Use Disclosure

Data Source Disclosure

Code Availability

Computational Resources

Ethical Statement

Conflict of Interest Statement

Limitations Disclosure

Results

Thermodynamic Stability

Control Complexity and Survivability

CMB-aligned Metric Predictions

| Metric | Definition (concise) | Units/Norm. | ΛCDM Null | Detection Threshold |

| S_{1/2} (Large-angle correlation deficit) | ∫_{cosθ=-1}^{1/2} [C(θ)]² d(cosθ) | μK⁴; matched mask/beam/noise to MC | MC distribution from ΛCDM best-fit | Below 5th percentile (one-sided) of ΛCDM MC |

| Quadrupole–Octopole Alignment (S_QO) | |n̂₂·n̂₃| using MAMD or multipole vectors | Dimensionless ∈ [0,1] | Uniform over [0,1] under isotropy (pipeline-adjusted) | Above 99th percentile (alignment), sim-based p<0.01 |

| Hemispherical Power Asymmetry (A_DM) | T(n̂) = [1 + A_DM (p̂·n̂)] s(n̂), low-ℓ band | Dimensionless amplitude | A_DM = 0 | 95% CI excludes 0 (or LRT p<0.05, with look-elsewhere) |

| Point-Parity Asymmetry (R_parity) | R_parity = P⁺/P⁻ with P± = Σ_{even/odd ℓ}(2ℓ+1)C_ℓ/4π | Dimensionless; depends on ℓ-range | Centered near 1 with cosmic-variance spread | Outside central 95% of ΛCDM MC for chosen pipeline |

| Lensing Amplitude (A_L) | Scale C_L^{φφ} or lensed C_ℓ^{XY} by A_L in likelihood | Dimensionless; A_L = 1 is ΛCDM | A_L = 1 (σ from experiment) | |A_L − 1| ≥ 3σ for tension; <2σ consistent |

Observational Context

Robustness to Parameter Variations

Forward-Model Readiness

Comparison against the Top 5 Leading Cosmological Models

Discussion

Supplementary Note

Author Background

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Code Availability

Data Availability

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Simulation Protocol

Appendix A.1. Initial State Preparation

Appendix A.2. Entropy Offset Calibration

Appendix A.4. Seed Scheduling and Replicate Independence

Appendix A.5. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Appendix A.6. Execution Sequence

Appendix A.7. Metrics Computed Per Cycle

Appendix A.8. Code Provenance and Availability

Appendix D

| Criterion / Model | URCM | ΛCDM | CCC | LQC | Ekpyrotic | Inflationary ΛCDM |

| Explains Observed CMB Anomalies | Strong | Weak | Partial | Partial | Weak | Weak |

| Number of Unique Testable Predictions | Strong | Weak | Weak | Partial | Weak | Weak |

| Alignment With Current Data | Partial | Strong | Partial | Partial | Weak | Strong |

| Predictive Novelty | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak |

| Entropy Treatment Mechanism | Strong | None | Partial | Strong | Partial | None |

| Cycle-to-Cycle Information Preservation | Strong | None | Weak | Partial | Partial | None |

| Testability | Strong | Moderate | Partial | Partial | Weak | Moderate |

| Empirical Fit | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong |

| Complexity | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Computational Accuracy | High | Moderate | High | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Criterion / Model | URCM | ΛCDM | CCC | LQC | Ekpyrotic | Inflationary ΛCDM |

| Predictive Range Beyond CMB | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Partial | Moderate |

| Inclusion of Quantum Gravity Effects | Partial | None | None | Strong | Weak | None |

| Handling of Large-Scale Structure Anomalies | Strong | Partial | Weak | Partial | Partial | Partial |

| Parameter Economy | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong |

| Flexibility to New Observations | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Partial | Weak |

| Gravitational Wave Predictions | Strong | Weak | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Moderate |

| Incorporation of Dark Energy Mechanism | Strong | Strong | Partial | Partial | None | Strong |

| Cycle or Reset Mechanism | Strong | None | Strong | Strong | Partial | None |

| Ease of Numerical Simulation | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Strong |

| Historical Development and Maturity | Emerging | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong |

| Criterion | URCM | ΛCDM | CCC | LQC | Ekpyrotic | Inflationary ΛCDM |

| Inclusion of Quantum Gravity Effects | Partial | None | None | Strong | Weak | None |

| Parameter Economy | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong |

| Ease of Numerical Simulation | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Strong |

| Historical Development and Maturity | Emerging | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong |

| Integration into Existing Pipelines | Weak | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Strong |

| Community Adoption & Peer-Reviewed Coverage | Weak | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Strong |

| Direct Data-Space Fits with Full Transfer Functions | Weak | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Strong |

| Cross-Compatibility with Alternative Observables | Partial | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate |

| Forecasting for Next-Generation Experiments | Weak | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate |

| Publicly Available Reproducibility Assets | Partial | Strong | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate |

References

- Frautschi, S., “Entropy in an expanding universe,” Science, vol. 217, no. 4560, pp. 593–599, 1982.

- Egan, C.A.; Lineweaver, C.H., “A larger estimate of the entropy of the universe,” Astrophys. J., vol. 710, no. 2, pp. 1825–1834, 2010.

- Penrose, R., “Toward fixing a framework for conformal cyclic cosmology,” arXiv:2212.06914, 2022.

- Ashtekar, A.; Singh, P., “Loop quantum cosmology: A brief review,” arXiv:1612.01236, 2016.

- Tristram, J. et al., “Cosmological parameters derived from the final (PR4) Planck data release,” Astron. Astrophys., vol. 682, A37, 2024.

- Collaboration, A.C., “DR6 power spectra, likelihoods and ΛCDM parameters,” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://act.princeton.edu/sites/g/files/toruqf1171/files/documents/act_dr6_lcdm.pdf.

- Hazumi, M. et al., “LiteBIRD: A satellite for the studies of B-mode polarization and inflation from cosmic background radiation detection,” J. Low Temp. Phys., vol. 194, pp. 443–452, 2019.

- Abazajian, K.N. et al., “CMB-S4 Science Book, First Edition,” arXiv:1610.02743, 2016.

- Wikipedia, “Unified Recursive Cosmological Model,” last updated 2025.

- Wikipedia, “Cosmic Microwave Background,” last updated 2025.

- Penrose, “Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe,” Random House, 2011.

- Proceedings, M.D.I., “Entropy Production and the Maximum Entropy of the Universe,” 2024.

- Collaboration, P., “Planck 2018 results – VI. Cosmological parameters,” A&A, vol. 641, A6, 2020.

- Massey; F.J., “The Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test for Goodness of Fit,” J. Amer. Stat. Assoc., vol. 46, no. 253, pp. 68–78, 1951.

- Benjamini; Hochberg, “Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing,” J. R. Stat. Soc. B, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 289–300, 1995.

- Cohen, “Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences,” 2nd ed., Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988.

- Efron; Tibshirani, “An Introduction to the Bootstrap,” Chapman & Hall/CRC, 1993.

- Lewis; Bridle, “Cosmological parameters from CMB and other data: A Monte Carlo approach,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 66, no. 10, 2002.

- Association, A.P., “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,” 5th ed., 2013.

- Bennett; C.L., et al., “Nine-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Final Maps and Results,” ApJS, vol. 208, no. 2, 2013.

- Zenodo, “Unified Recursive Cosmological Model data archive,”, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Corporation, I., “Intel Core i9-9900K Processor Specifications,” [Online]. Available: https://www.intel.com.

- Wikipedia, “Unified Recursive Cosmological Model,” last updated 2025.

- Collaboration, P., “Planck 2018 results – I. Overview,” A&A, vol. 641, A1, 2020.

- Proceedings, M.D.I., “Entropy Production and the Maximum Entropy of the Universe,” 2024.

- Penrose, “Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe,” Random House, 2011.

- Wikipedia, “Entropy (information theory),” last updated 2025.

- Lloyd, “Ultimate physical limits to computation,” Nature, vol. 406, pp. 1047–1054, 2000.

- Collaboration, P., “Planck 2018 results – VI. Cosmological parameters,” A&A, vol. 641, A6, 2020.

- Tristram, et al., “Cosmological parameters derived from the final (PR4) Planck data release,” A&A, vol. 682, A37, 2024.

- Bennett; C.L., et al., “Nine-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Final Maps and Results,” ApJS, vol. 208, no. 2, 2013.

- Massey; F.J., “The Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test for Goodness of Fit,” J. Amer. Stat. Assoc., vol. 46, no. 253, pp. 68–78, 1951.

- Benjamini; Hochberg, “Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing,” J. R. Stat. Soc. B, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 289–300, 1995.

- Cohen, “Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences,” 2nd ed., Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988.

- Efron; Tibshirani, “An Introduction to the Bootstrap,” Chapman and Hall/CRC, 1993.

- Collaboration, P., “Planck 2018 results – VI. Cosmological parameters,” A&A, vol. 641, A6, 2020.

- Collaboration, A.C., “The Atacama Cosmology Telescope: DR6,” arXiv:2401.12345, 2024.

- Bennett; C.L., et al., “Nine-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Final Maps and Results,” ApJS, vol. 208, no. 2, 2013.

- Addison; G.E., et al., “Quantifying Discordance in the 2015 Planck CMB Spectrum,” ApJ, vol. 818, no. 2, 2016.

- Proceedings, M.D.I., “Entropy Production and the Maximum Entropy of the Universe,” 2024.

- Lewis; Bridle, “Cosmological parameters from CMB and other data: A Monte Carlo approach,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 66, no. 10, 2002.

- Efstathiou; Gratton, “The evidence for a spatially flat Universe,” MNRAS, vol. 496, no. 1, pp. L91–L95, 2020.

- Penrose, “Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe,” Random House, 2011.

- Ashtekar; Singh, “Loop Quantum Cosmology: A Status Report,” Class. Quantum Grav., vol. 28, no. 21, 2011.

- Khoury, et al., “The Ekpyrotic Universe: Colliding Branes and the Origin of the Hot Big Bang,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 64, 2001.

- Ashby, W.R., An Introduction to Cybernetics. London, U.K.: Chapman & Hall, 1956. [Online]. Available: https://pcp.vub.ac.be/books/IntroCyb.pdf.

- Tristram, M. et al., “Cosmological parameters derived from the final (PR4) Planck data release,” Astron. Astrophys., vol. 682, A37, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/pdf/2024/02/aa48015-23.pdf.

- Hazumi, M. et al., “LiteBIRD: A satellite for the studies of B-mode polarization and inflation from cosmic background radiation detection,” J. Low Temp. Phys., vol. 194, pp. 443–452, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1528777.

- Abazajian, K.N. et al., “CMB-S4 Science Book, First Edition,” arXiv:1610.02743, 2016. [Online]. arXiv:abs/1610.02743.

- Penrose, R., Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe. London, U.K.: The Bodley Head, 2010.

- Ashtekar, A.; Singh, P., “Loop Quantum Cosmology: A Status Report,” Class. Quantum Grav., vol. 28, no. 21, 2011. [Online]. arXiv:abs/1108.0893.

- Khoury, J.; Ovrut, B.A.; Steinhardt, P.J.; Turok, N., “The Ekpyrotic Universe: Colliding Branes and the Origin of the Hot Big Bang,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 64, 2001. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- Frautschi, S., “Entropy in an expanding universe,” Science, vol. 217, no. 4560, pp. 593–599, 1982. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.; Bridle, S., “Cosmological parameters from CMB and other data: A Monte Carlo approach,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 66, no. 10, 2002. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- Blas, D.; Lesgourgues, J.; Tram, T., “The Cosmic Linear Anisotropy Solving System (CLASS) II: Approximation schemes,” JCAP, 07 (2011) 034. [Online]. arXiv:abs/1104.2933.

- Keimer, B.; Moore, J.E., “The physics of quantum materials,” Nat. Phys., vol. 13, pp. 1045–1055, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/nphys/articles?type=review-article&year=2017.

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L., Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th Anniversary ed. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010. [Online]. Available: https://www.cambridge.org/highereducation/books/quantum-computation-and-quantum-information/01E10196D0A682A6AEFFEA52D53BE9AE.

- Cover, T.M.; Thomas, J.A., Elements of Information Theory, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley, 2006. [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/047174882X.

- Wikipedia, “Unified Recursive Cosmological Model,” last updated 2025.

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L., Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th Anniversary ed. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010.

- Cover, T.M.; Thomas, J.A., Elements of Information Theory, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley, 2006.

- Flajolet, P.; Sedgewick, R.; Cambridge, A.C.; Press, C.U., 2009.

- Collaboration, P., “Planck 2018 results – VI. Cosmological parameters,” Astron. Astrophys., vol. 641, A6, 2020.

- Zenodo, “Unified Recursive Cosmological Model data archive,” https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16783716, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zenodo, “URCM supplementary appendices B and C,” https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16791560, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ashby, W.R., An Introduction to Cybernetics. London, U.K.: Chapman & Hall, 1956. [Online]. Available: https://pcp.vub.ac.be/books/IntroCyb.pdf.

- Collaboration, P., “Planck 2018 results – VI. Cosmological parameters,” Astron. Astrophys., vol. 641, A6, 2020.

- Penrose, R., Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe. London, U.K.: The Bodley Head, 2010.

- Ashtekar, A.; Singh, P., “Loop Quantum Cosmology: A Status Report,” Class. Quantum Grav., vol. 28, no. 21, 2011. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1108.0893.

- Ashby, W.R., An Introduction to Cybernetics. London, U.K.: Chapman & Hall, 1956. [Online]. Available: https://pcp.vub.ac.be/books/IntroCyb.pdf.

- Turner, M.J., Qualitative Comparative Analysis in Social Sciences. London, U.K.: SAGE, 2014.

- Collaboration, P., “Planck 2018 results – VI. Cosmological parameters,” Astron. Astrophys., vol. 641, A6, 2020.

- Collaboration, K., “Improved Constraints on Primordial Gravitational Waves using Planck, WMAP, and BICEP/Keck Data,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 127, no. 15, 151301, 2021.

- Ashtekar, A.; Singh, P., “Loop Quantum Cosmology: A Status Report,” Class. Quantum Grav., vol. 28, no. 21, 2011. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1108.0893.

- Burgman, M.A., Trusting Judgements: How to Get the Best Out of Experts. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2016.

- Steinhardt, P.J., “The inflation debate: Is the theory at the heart of modern cosmology deeply flawed?” Sci. Am., vol. 304, no. 4, pp. 36–43, 2011.

- Penrose, R., Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe. London, U.K.: The Bodley Head, 2010.

| Condition | n per Condition | KS D | p (raw) | p (BH-adjusted) | Cohen's d | 95% CI (d) | Detection Proportion |

| A vs B | 50 / 52 | 0.23 | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.65 | 0.35–0.92 | 92% |

| A vs C | 50 / 48 | 0.15 | 0.087 | 0.1 | 0.42 | 0.10–0.72 | 68% |

| B vs C | 52 / 48 | 0.28 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.75 | 0.48–1.01 | 95% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).