Introduction

In 2024, Abrahao et al. reported a remarkable experiment [

1], in which a laser beam, under certain conditions, casts a shadow—something typically only observed with material objects. The experimental setup was described as follows:

“As our object we use a laser beam with an optical wavelength of 532 nm. This object beam travels through a cube of standard ruby crystal. We illuminate the beam from the side with blue light.” That is, the object laser beam (light at 532 nm, perceived as green) and the broader blue beam (450 nm) intersect at a right angle within the ruby crystal. After passing through the crystal, a darker region appears in the blue light where the projection of the object beam lies, apparently because the crystal molecules (Al₂O₃ : Cr) are induced by the green light to absorb more of the blue light (“wherever the object laser beam (green) exists in the ruby, it increases the optical absorption of the illuminating laser beam (blue)”).

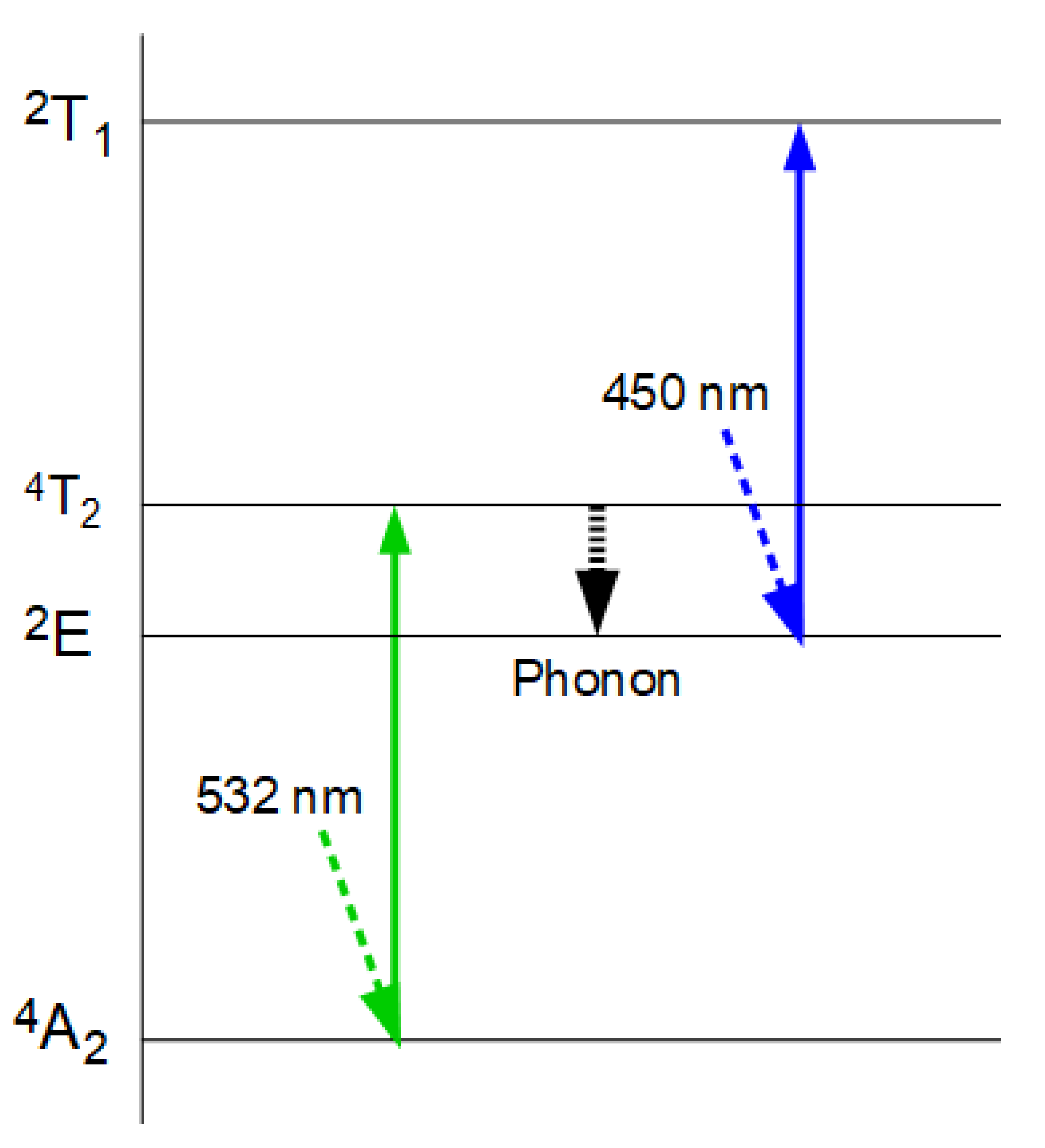

The authors explain this effect by proposing the existence of various hierarchically arranged energy levels in the ruby crystal lattice: “One colour is green, the object laser beam, which has an optical wavelength of 532 nm. It will drive the transition of the ground state ⁴A₂ to an excited state ⁴T₂, which then decays rapidly via phonons to the ²E state. This then allows the electron to absorb blue light (450 nm), the illumination, by transitioning from ²E to ²T₁. However, the blue laser (450 nm) could in principle be absorbed by the electrons in ⁴A₂ and transition to some other level (…). The effect will only take place if the absorption cross-section of the second transition (²E to ²T₁) is larger than that of the first transition (⁴A₂ to ⁴T₂).”

Based on the assumption expressed in the last sentence, one of the authors (Safari), together with others, has already explained the phenomenon of reverse saturation of absorption observed in ruby for a certain frequency range—i.e. that absorption increases with increasing laser intensity [

24].

The assumption of hierarchical energy levels appears entirely plausible when one considers Bohr’s orbital model of the atom: the electron can exist only in certain “permitted” orbits around the nucleus. However, modern quantum theory has replaced the concept of circular orbits with spatial distributions of the electron’s probability density, which, in particularly simple cases, can be calculated exactly. For atoms with two or more electrons — and especially for molecules — only approximate solutions are feasible.

Nonetheless, it is indisputable that well-defined orbitals — and corresponding energy levels — exist, and that a molecule must absorb or emit a specific amount of energy in order to transition from one orbital to another. In order for a photon of a given energy or frequency (hereafter referred to as its ‘colour’, following common usage for light, while acknowledging that this is, strictly speaking, a physiological rather than a physical concept) to be absorbed, the energy difference between two orbitals must correspond to the photon’s energy.

If the electron does not initially occupy an energy level (orbital) from which a transition to a higher, permitted level is possible via absorption of a photon of a given colour, then — according to the hierarchical model — that photon cannot be absorbed. Whether or not a photon of a certain colour is absorbed thus determines, under this premise, the potential absorbability of another photon of a different colour. According to this model, a causal dependency thus exists between photon colours with respect to molecular absorption. The Ritz combination principle in spectroscopy could also be interpreted as supporting this assumption of hierarchical orbitals.

However, it is well known that the Bohr model — despite its lasting influence on our conceptual understanding — is incorrect. The planetary system is not an appropriate analogy for the atom. We would not revisit this model were it not for the fact that the derived assumption — of a hierarchical influence on the absorption of photons of different colours or frequencies — appears to be either incorrect or valid only in a limited sense. These conclusions are fundamentally connected to the Boltzmann factor and Planck’s law of radiation.

The experimental findings of Abrahao et al. (2024) [

1] clearly demonstrate that interactions between the absorptive capacities for photons of different energies do occur — though in this case, they may not be hierarchical in nature. An alternative mechanism for such influence is proposed, along with experiments designed to test this hypothesis. These experiments may also contribute to resolving the fundamental question of whether particles such as photons can interfere with themselves, as suggested by the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory.

Absorption and Emission of Photons and the Boltzmann Factor

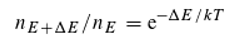

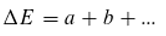

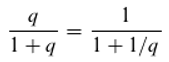

The Boltzmann factor describes the relationship between particle energies and their relative frequencies as a function of temperature T (k being the Boltzmann constant):

n

E+ΔE and n

E represent the relative frequencies of particles with energies

E+ΔE and

E, respectively. We assume that this equation, which describes the equilibrium of energy exchange resulting from the interaction of quanta with matter, is valid. For the holochromatic molecule, which can absorb quanta of different energies (

a, b, …, with

a, b, … ∈ ℝ₀⁺), the following applies:

when a particle with energy

(E+ΔE) has absorbed quanta of energy (or “colour”)

a, b, etc., whereas a particle with energy

E has not. Furthermore, let

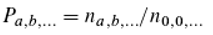

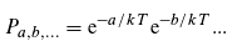

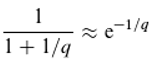

so that the following holds:

That can, however, also be written as:

Assuming that

and so on, it naturally follows that:

Where

and so on.

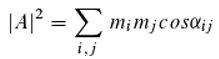

nₐ is the relative number of all molecules that contain an

a-quantum, completely independent of which quanta of other colours they do or do not contain. Correspondingly,

n₀... is the relative number of all molecules that do not possess an

a-quantum. Equation 6 in conjunction with Equation 8 describes the energy distribution in “monochromatic resonators” [

3,

29], which Boltzmann derived from probabilistic considerations (his model for molecules). We can therefore assume that the relationship between Equations 6 and 8 is consistent. From Equation 7 it then follows that the state distributions of the individual “colours” can be regarded as independent of each other (this is explained in more detail in Ref. 29).

This, in turn, means that absorption and emission events of quanta of different energies do not influence each other. This hypothesis straightforwardly aligns with empirical evidence but contradicts a common view that assigns hierarchical energy levels to molecules and thereby postulates a hierarchical dependence of emission and absorption events. It also apparently contradicts the experiment by Abrahao et al. (2024) [

1].

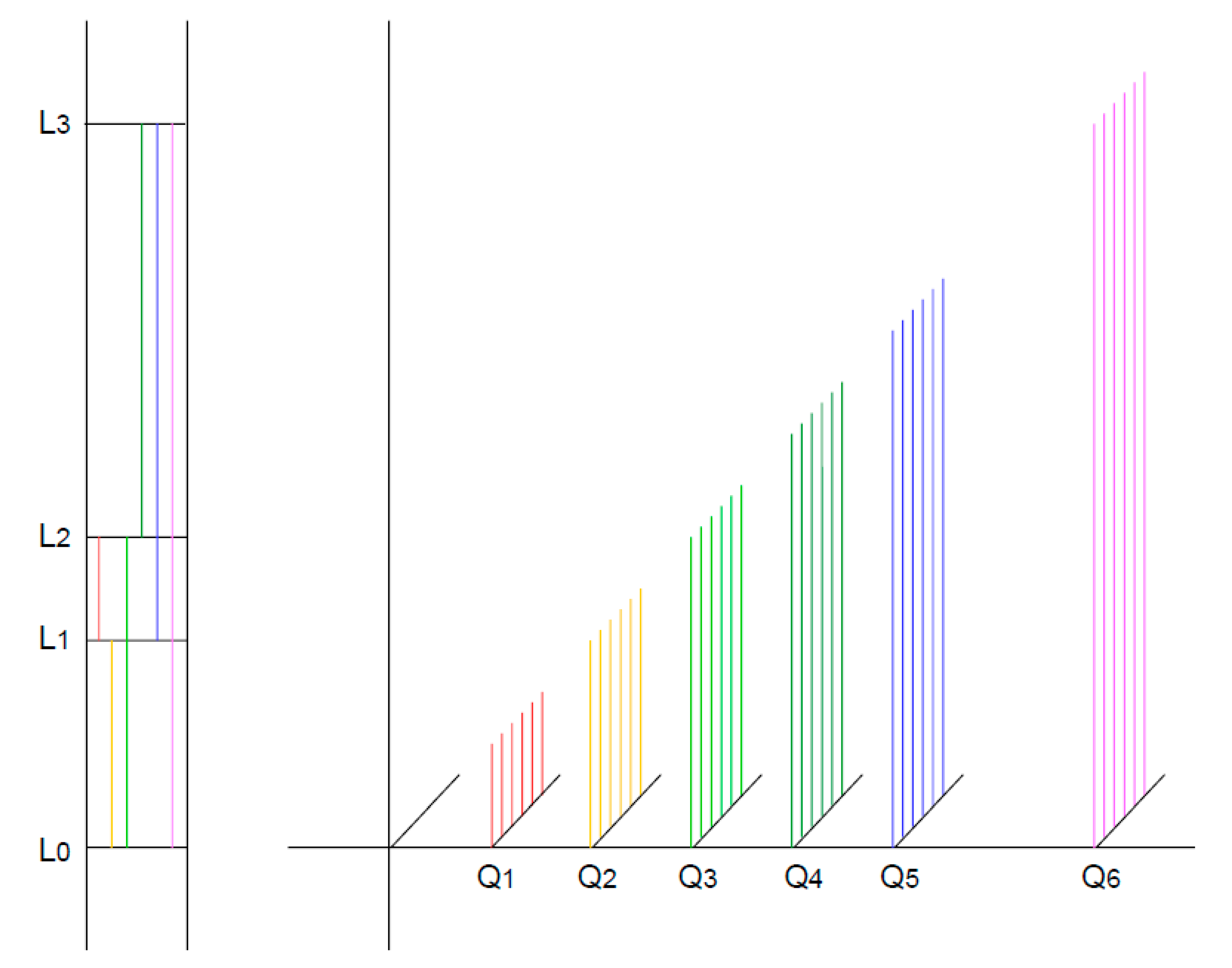

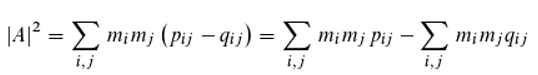

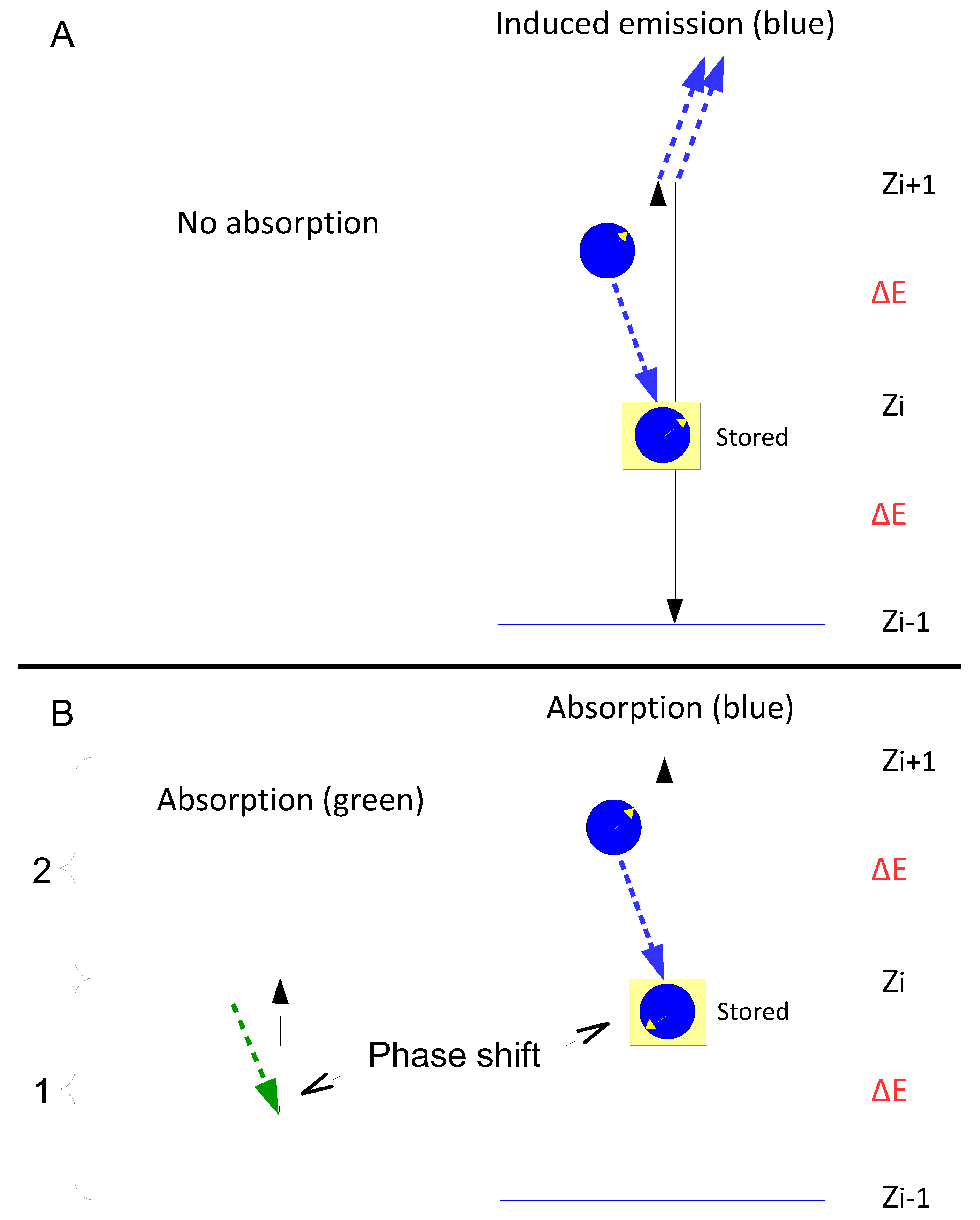

Figure 1 illustrates the difference using a simple “model molecule” for which the Ritz combination principle applies.

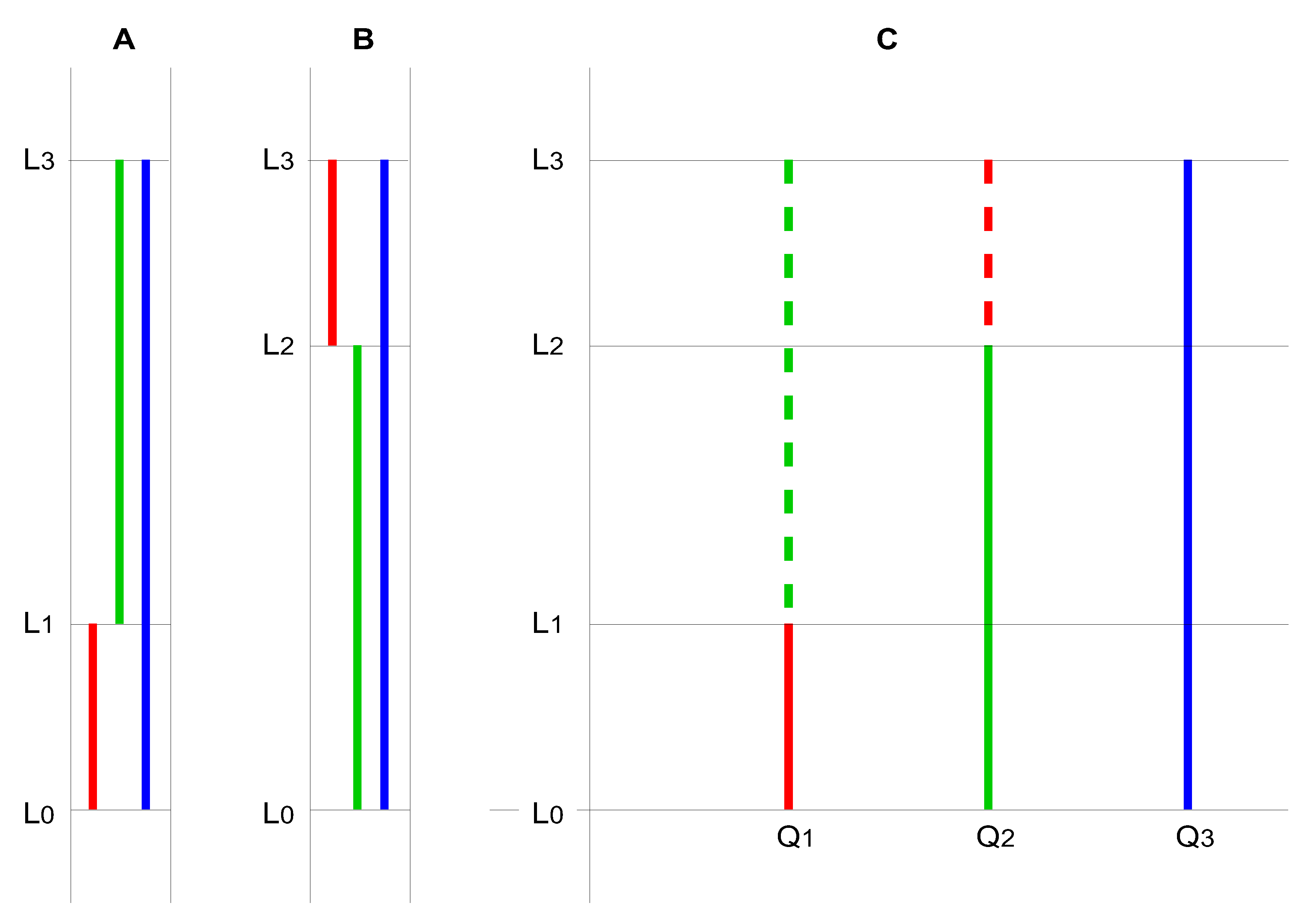

Figure 1.

The energy levels in ruby relevant to the experiment by Abrahao et al. (2024). Absorption of a “green” photon (wavelength 532 nm) raises the energy level to ⁴T₂, which then relaxes via phonon emission to ²E. This level forms the starting point for the absorption of a “blue” photon (wavelength 450 nm).

Figure 1.

The energy levels in ruby relevant to the experiment by Abrahao et al. (2024). Absorption of a “green” photon (wavelength 532 nm) raises the energy level to ⁴T₂, which then relaxes via phonon emission to ²E. This level forms the starting point for the absorption of a “blue” photon (wavelength 450 nm).

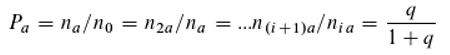

Figure 2.

A–C: A, B: Alternative hierarchical models of the energy levels of a molecule that can absorb three differently coloured quanta. C: A non-hierarchical model. Note that the level L₂–L₁ is not occupied. If it were, a new energy level would be created, leading ultimately to an infinite cascade of absorbable quanta of different colours.

Figure 2.

A–C: A, B: Alternative hierarchical models of the energy levels of a molecule that can absorb three differently coloured quanta. C: A non-hierarchical model. Note that the level L₂–L₁ is not occupied. If it were, a new energy level would be created, leading ultimately to an infinite cascade of absorbable quanta of different colours.

The hypothetical molecule can absorb—or emit from the excited state—three differently coloured (energetic) quanta (Q

1: red; Q

2: green; Q

3: blue). According to the Ritz combination principle, the energy of Q

3 results from the sum of the energies of Q

1 and Q

2. In this simple case, two hierarchies are possible (

Figure 1A and 1B).

In

Figure 1A, Q

2 can only be absorbed if the molecule is already in the excited state with respect to Q

1; in

Figure 1B, Q

2 must have been absorbed for Q

1 to be absorbed. The two models in Figures 1A and 1B are generally considered mutually exclusive—that is, either one model or the other is correct. However, Equation 7 suggests that both models are equally valid, as hinted at in

Figure 1C. Despite the validity of the Ritz combination principle, the absorption of quanta of different colours is assumed to be independent.

How can it be that the experiment by Abrahao et al. (2024) and the conclusions drawn from the Boltzmann factor appear to contradict each other? The derivation of the Boltzmann factor is based on a model—the “monochromatic resonator”—which we must briefly consider if we want to understand the contradiction.

Interference Experiments with Light and an Alternative Hypothesis on the Interaction of Light and Matter

In his book “The Principles of Quantum Mechanics” (third edition, 1947), P. A. M. Dirac explains why classical physics, in his view, is insufficient to explain nature [

8]:

“...we are concerned only with observable things and ... we observe an object only by letting it interact with some outside influence. An act of observation is thus necessarily accompanied by some disturbance of the object observed. We may define an object to be big when the disturbance accompanying our observation of it may be neglected, and small when the disturbance cannot be neglected. If ... the limiting disturbance is not negligible, ... we require a new theory for dealing with it. … Causality applies only to a system which is left undisturbed. If a system is small, we cannot observe it without producing a serious disturbance and hence we cannot expect to find any causal connexion between the results of our observations.” (Emphases added by me)

This position is likely uncontroversial. The basis of his interpretation of quantum physics is the Copenhagen interpretation, which, however, remains not universally accepted. Its essential element is the principle of superposition. Dirac illustrates it by means of experiments on the polarisation and interference of photons. The latter is relevant to the present work:

“Suppose we have a beam of light which is passed through some kind of interferometer, so that it gets split up into two components and the two components are subsequently made to interfere. We may … take an incident beam consisting of only a single photon and inquire what will happen to it as it goes through the apparatus. ... we must now describe ... the photon as going partly into each of the two components into which the incident beam is split. … Let us consider now what happens when we determine the energy in one of the components. The result of such a determination must be either the whole photon or nothing at all. Thus the photon must change suddenly from being partly in one beam and partly in the other to being entirely in one of the beams.”

According to this view, before measurement the photon does not have a clearly defined path but exists in a superposition of all possible trajectories (in the interferometer as well as in the double-slit experiment, there are two. In other interference experiments, such as multiple-slit setups, there may be many). It is only upon measurement that this changes. Dirac further states:

“Some time before the discovery of quantum mechanics people realized that the connexion between light waves and photons must be of a statistical character. What they did not clearly realize, how ever, was that the wave function gives information about the probability of one photon being in a particular place and not the probable number of photons in that place.”

This view was never accepted by A. Einstein, who strongly opposed it [

12]. For him, quantum physics was an ensemble theory, making no statement about a single event or, in the example discussed, the fate of an individual photon. Even today, many do not accept Dirac’s conclusion (or the Copenhagen interpretation)—see, for example, Ref. 30. Dirac, however, extended this assumption as follows:

“Each photon ... interferes only with itself. Interference between two different photons never occurs.”

Under this premise—that is, without assuming that, for example, photons of the same colour but different phases can interfere with each other—it is difficult to understand the difference between coherent (e.g., laser) and incoherent light (e.g., sunlight) [

17]. Some observations support the assumption that the trajectory of a photon essentially corresponds to that of a classical particle; i.e., that it follows one well-defined path only and does not interfere with itself (incidentally, Dirac also assumed classical paths for light in his derivation of the radiation law [

7], which dates from the early quantum theory period following Wentzel, Heisenberg and Schrödinger). It already follows from electromagnetic theory that an electromagnetic wave, unlike a classical transverse wave, transfers momentum in the direction of propagation [

21]. This, of course, presupposes a direction of propagation. But not only during absorption, but also during emission of a photon, the molecule interacting with the photon receives momentum in a specific direction, which would not be the case if a spherical wave or isotropic emission were involved [

11]. Curiously, in connection with the Born rule, it also follows that even in multiple-slit experiments (when there are more than two slits), only two paths interfere at a time [

16]. This has also been experimentally confirmed [

25]. Finally, the double-slit experiment can also be performed with electrons. Here too, an interference pattern emerges; on the other hand, in the cloud chamber, the path of the electron is visible, a fact that troubled Heisenberg and prompted him to formulate the uncertainty principle [

18]. Not the only, but the most straightforward explanation for the observation in the cloud chamber is that electrons do indeed follow a definite path.

Of course, none of these observations constitutes a decisive proof against the Copenhagen interpretation, particularly since there is no compelling alternative. However, the Copenhagen interpretation itself ensures that no such alternative can be found [

8]:

“Only questions about the results of experiments have a real significance and it is only such questions that theoretical physics has to consider.”

As an example concerning the phenomenon of polarisation, Dirac states:

“Questions about what decides whether the Photon is to go through or not … a crystal of tourmahne, which has the property of letting through only light plane-polarized perpendicular to its optic axis … and how it changes its direction of polarization when it does go through cannot be investigated by experiment and should be regarded as outside the domain of science.”

This “prohibits” models concerning the mechanism of the interaction between light and matter, although many such models could exist which do not contradict the observations nor quantum theory. Not all have adhered to this restriction. Most notably, L. de Broglie’s phase or pilot-wave theory [

4] and M. Born’s “quantum mechanical” potential [

2] have become well known. Both are consistent with the mathematics of quantum theory but not with the Copenhagen interpretation, insofar as they do not rely on the superposition of a particle with itself. The assumptions made by Einstein regarding the interaction of light and matter in his derivation of the radiation law (a purely kinetic model) arguably go beyond what Dirac would permit (yet they are widely accepted and certainly not dismissed as unscientific) [

9,

10].

Only after the turn of the millennium has a new approach emerged, consisting in the development of algorithms that produce, via computer simulations, results consistent with those of quantum physics, without employing quantum theory in the form of the Copenhagen interpretation. For the simulation of an interferometer experiment, photons are initially attributed with unusual properties [

20]:

“We consider the photon to be a particle having an internal clock with one hand that rotates with a frequency f = ω/2π. Hence, the rotation velocity of the hand depends on the angular frequency ω, that is the “color” of the photon. Thus, the hand of a blue photon rotates faster than the hand of a red photon. As the photon travels from one position in space to another, the clock encodes its time of flight t modulo the period 1/f. We therefore view the photon as a messenger carrying as message the position of the clock’s hand. ... This particle model for the photon was previously used by Feynman in his theory of quantum electrodynamics [

14]

. Feynman used the position of the clock’s hand to calculate the probability amplitudes. Although quantum electrodynamics resolves the wave-particle duality by saying that light is made of particles ..., it is only able to calculate the probability that a photon will hit a detector, without offering a mechanism of how this actually happens.”

To inquire into such a mechanism would, according to Dirac, be considered “unscientific”, which may explain why earlier works by the authors explicitly state that no attempt is made to reinterpret quantum mechanics [

5], and that the model is not intended to represent physical reality [

19]. Only in the cited work [

20] does this position change.

In any case, the assumption that a photon can interfere with itself is not part of the authors’ model. If a photon is incapable of self-interference—and if, as follows from electromagnetic theory, light cannot interfere in vacuum (i.e., interaction with matter is required)—then interference at the detector, which De Raedt et al. (2005) consider central to their model, must occur between different photons of the same colour (i.e., energy) emitted by the source. The emitted light is assumed to be coherent. The detector decides, based on messages from multiple photons (which it stores internally) and using a threshold function, whether a detection event (a “click”) occurs. Thus, not every photon is detected, and a “click” does not correspond to a single photon.

The results of the simulations of interference experiments [

5,

19,

20] fully agree with the predictions of quantum theory

in terms of the probability of detecting a photon. However, this correspondence holds only for detection frequency, not for the energy density of the radiation at the detector, since many photons are not registered. The source therefore emits more energy than can, in principle, be detected.

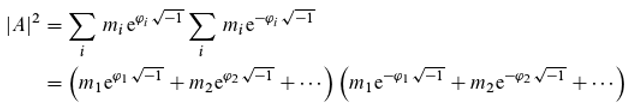

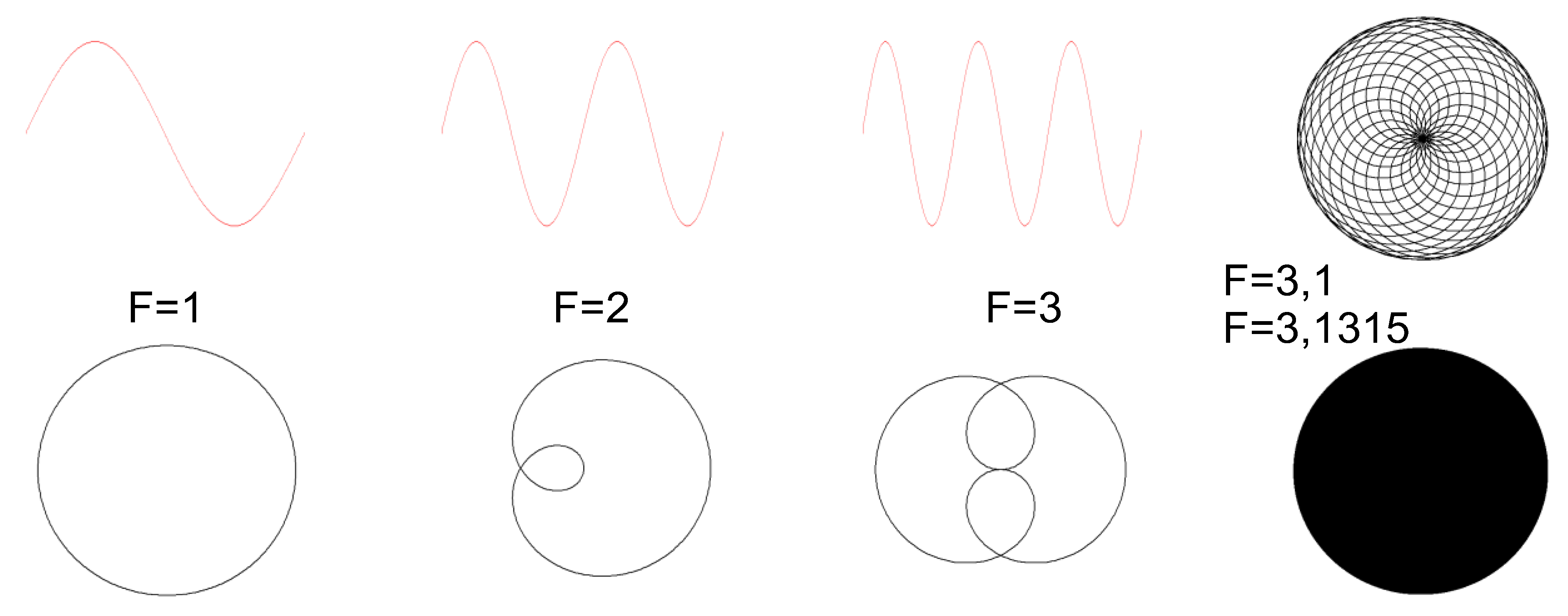

As mentioned,

“Feynman ... used the position of the clock’s hand to calculate the probability amplitudes.” In the multiple-(k)-slit experiment, for instance, the detection probability at the location of the detector is given by the square of the modulus of the probability amplitude

A (according to Born’s rule), where

k different paths from the source to the detector are possible. The photons arrive at the detector carrying the phase information

φᵢ (

i = 1, …,

k), which differs depending on the length of the respective path from the source to the detector. The relative frequency of photons with phase information

φᵢ is denoted by

mᵢ (with ∑

mᵢ = 1; in the double-slit experiment,

k = 2). For the experiment, the following applies (here,

i denotes an index, contrary to convention, and not the imaginary unit):

Eq. 13 describes the superposition as the addition of complex numbers (supplemented by Born’s rule, although the necessity of applying this rule remains unexplained), each corresponding to one of the various possible paths of a photon. The mathematics is therefore in complete agreement with the principle of superposition, and it appears entirely clear how quantum mechanics is to be interpreted.

However, Eq. 13 can be very easily reformulated as [

26,

27,

28]:

where αᵢⱼ = φᵢ − φⱼ (

i, j = 1, …,

k). To obtain the detection probability, one must therefore form the sum (over all photons) of all possible pairwise comparisons of the photon phases at the moment they reach the detector, and divide the result by the square of the total number of photons. The interpretation of Eq. 14, which is mathematically equivalent to Eq. 13, now appears entirely different! Moreover, Born’s rule becomes redundant. Based on this equation, one can assume that the detector—or, more precisely, a molecule within it—performs a pairwise comparison of photons. Eq. 14 does not permit any conclusions about individual photons; it merely yields a statistical prediction.

We now seek a suitable process that allows for such pairwise comparisons and find it in the stimulated emission postulated by Einstein in 1916 [

9], which, however, we must reinterpret in light of Eq. 14 and the postulates concerning photon properties by De Raedt et al. (2005). According to this model, the detector consists of idealised molecules, which act as monochromatic resonators. In the excited state, the molecule has absorbed a photon and—according to the postulate (which extends Einstein’s original ideas)—not only acquired its energy, but also stored its phase information. This information is then compared with that of a second photon upon collision (provided that spontaneous emission has not already occurred, which incidentally explains the phenomenon of coherence time, as already recognised by Wentzel in 1924 [

31]).

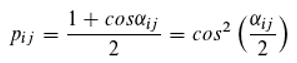

Depending on the degree of phase agreement, stimulated emission occurs with probability pᵢⱼ (thereby somehow triggering detection [

28]), whereas it fails to occur with complementary probability qᵢⱼ, where pᵢⱼ + qᵢⱼ = 1.

To satisfy some natural constraints [

26], one may choose

The detection probability is given by:

This means that, in order for the interference pattern to emerge, it must be possible for a detection event to be cancelled out by a complementary event—a “non-detection”. Eq. 16 replaces the threshold function used in the 2005 publication by De Raedt [

5].

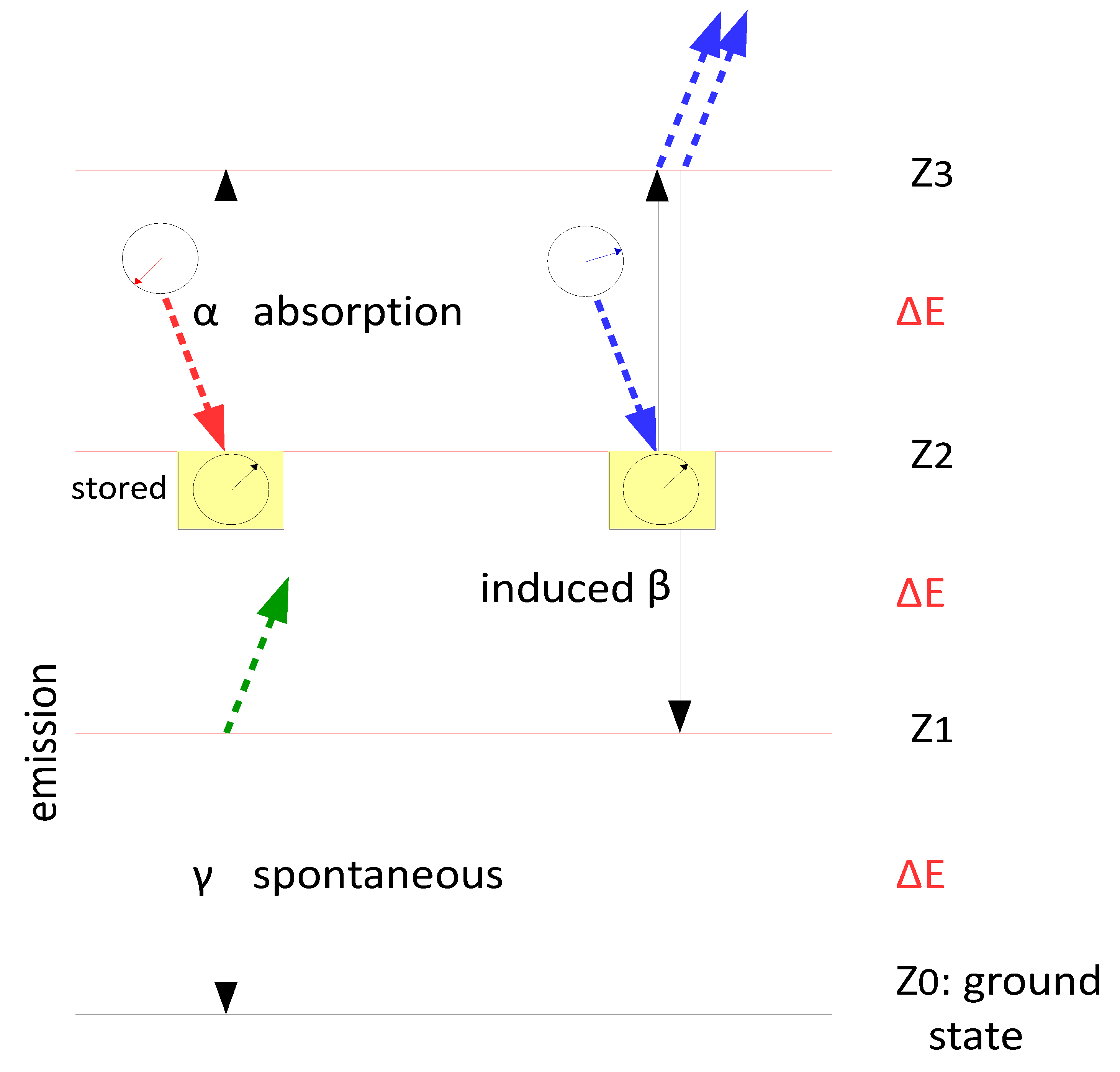

A detection event must therefore correspond to stimulated emission, as only in this process can a photon comparison take place. Since the molecule loses a photon in the course of this emission, it is plausible to assume that the complementary event is absorption, during which the molecule gains a photon. However, if the detector consists of monochromatic two-level systems (i.e. with only a ground and an excited state relative to a single colour), which behave independently of one another, such complementarity is impossible. According to Einstein’s model, the two complementary processes—stimulated emission and absorption—do not originate from the same state: absorption occurs from the ground state Z₀, while stimulated emission occurs from the excited state Z₁. In a two-level system, these are necessarily independent events, and their respective probabilities pᵢⱼ and qᵢⱼ generally do not sum to one.

In contrast, this is possible in a monochromatic resonator, because there exist many excited states

Zᵢ (see

Figure 5); such a system can absorb multiple quanta of the same colour (one might say that the mathematics of “quantum interference” describes the kinetics of a resonator).

For a monochromatic resonator to arise, the interaction of light with matter must involve the encounter of a photon with an ensemble of molecules, rather than with a single one. The author’s current views on this topic shall not be further discussed here; however, reference is made to [

6].

Einstein discovered in 1916 that the kinetic constants for absorption (α in

Figure 5) and stimulated emission (β) are equal (α = β). This is to be expected for incoherent light, provided that Eq. 15 holds—that is, if interference occurs at the monochromatic resonator. Furthermore, according to Ref. [

29], it follows that α=β=γ⁄2, where γ is the kinetic constant for spontaneous emission.

However, this relationship should change with the degree of coherence of the light: α and β are no longer constants, but variables that can be calculated using Eq. 15. The greater the coherence, the more likely stimulated emission should become at the expense of absorption. Nonetheless, Ref. [

29] states that the following must always hold: α+β=γ.

How can this help us understand the interaction of a molecule with light of different colours? How is it possible that, under incoherent illumination, such interactions generally do not influence each other (as follows from the Boltzmann factor and Planck’s radiation law), but do in fact influence one another when coherent light is used—as demonstrated, for example, by the experiment of Abraho et al. (2024)?

A Hypothesis on the Interaction of a Molecule with Photons of Different Colours and a Proposal for an Experiment

Based on the conclusions of the previous sections, we now return to the experiment by Abrahao et al. (2024). The ad hoc hypothesis providing an alternative explanation of their results (which goes beyond a mere reinterpretation of Eq. 13) is illustrated in

Figure 6. According to this, the ruby crystal acts as a multichromatic resonator in which absorption and stimulated emission of photons of different colours mutually influence each other at the molecular level, such that the absorption of a photon (in the example: green) leads to a change in the stored phase information of another colour (in the example: blue). This effect is assumed to occur regardless of whether the light is coherent or incoherent; however, an observable effect arises only with coherent light. This is because a phase shift caused by the absorption of a green photon on the stored phase information of a blue photon becomes noticeable only if the phases of the two photons of the same colour are not random. If the phase difference remains random—as is the case with incoherent light—then α=β, even if a constant value is added to one of the two phase informations.

As mentioned in the previous section, in the case of coherent light, stimulated emissions should occur more frequently at the expense of absorptions. Conversely, a phase shift of approximately π in the stored phase information leads to an increased probability of absorption events under coherent illumination (

Figure 6B). This results from the altered agreement between the stored phase information and that of the colliding photon, which is described by Eq. 15. Hence, the green laser beam casts a shadow in the coherent blue light (and also in blue LED light [

1], which must be discussed elsewhere). It is assumed that the reverse is also true—that is, the absorption of a blue photon (6B) induces a phase shift in the stored phase information of green.

Currently, there is no theory regarding the quantitative extent of the phase shift caused by absorption of a photon of a different colour, nor whether its coherence is also relevant, or what other factors it might depend on. That the phase shift amounts to approximately π in the experiment by Abrahao et al. (2024) can therefore only be inferred from the experimental results themselves.

The phenomenon of phase shifting can, in principle, also explain the “reverse saturation of absorption”, although in that case it remains unclear what causes the change in the stored phase information.

This raises the question of the experimental falsifiability of the hypothesis described above (according to A. Weissmann and K. Popper, theories cannot be verified; one must therefore be satisfied if an experiment does not falsify them). A suitable experimental approach could involve combining an interference experiment (such as a Mach–Zehnder interferometer or a multiple-slit experiment) with the setup described by Abrahao et al. (2024). This is first discussed using the example of the double-slit experiment, in which coherent, monochromatic light of wavelength 450 nm (blue) from a source passes through two narrow, parallel slits and reaches an observation screen. The distance from the slits to the screen is assumed to be much greater than the separation between the slits. A ruby crystal block is now integrated into the experimental setup immediately in front of the detection screen (i.e., without any spatial separation). A green laser beam with an optical wavelength of 532 nm passes laterally through a portion of the crystal.

If the theory developed here is correct, the interference pattern on the observation screen should be shifted within the projection area of the green laser beam relative to the rest of the interference pattern—such that the bright fringes in that region approximately coincide with the dark fringes elsewhere, and vice versa. One potential difficulty in implementing this setup concerns scaling: The ruby block, with an edge length of 1.2 cm, is relatively small, and accordingly, the adjacent detection screen — and thus the resulting interference pattern — would also need to be of comparable size.

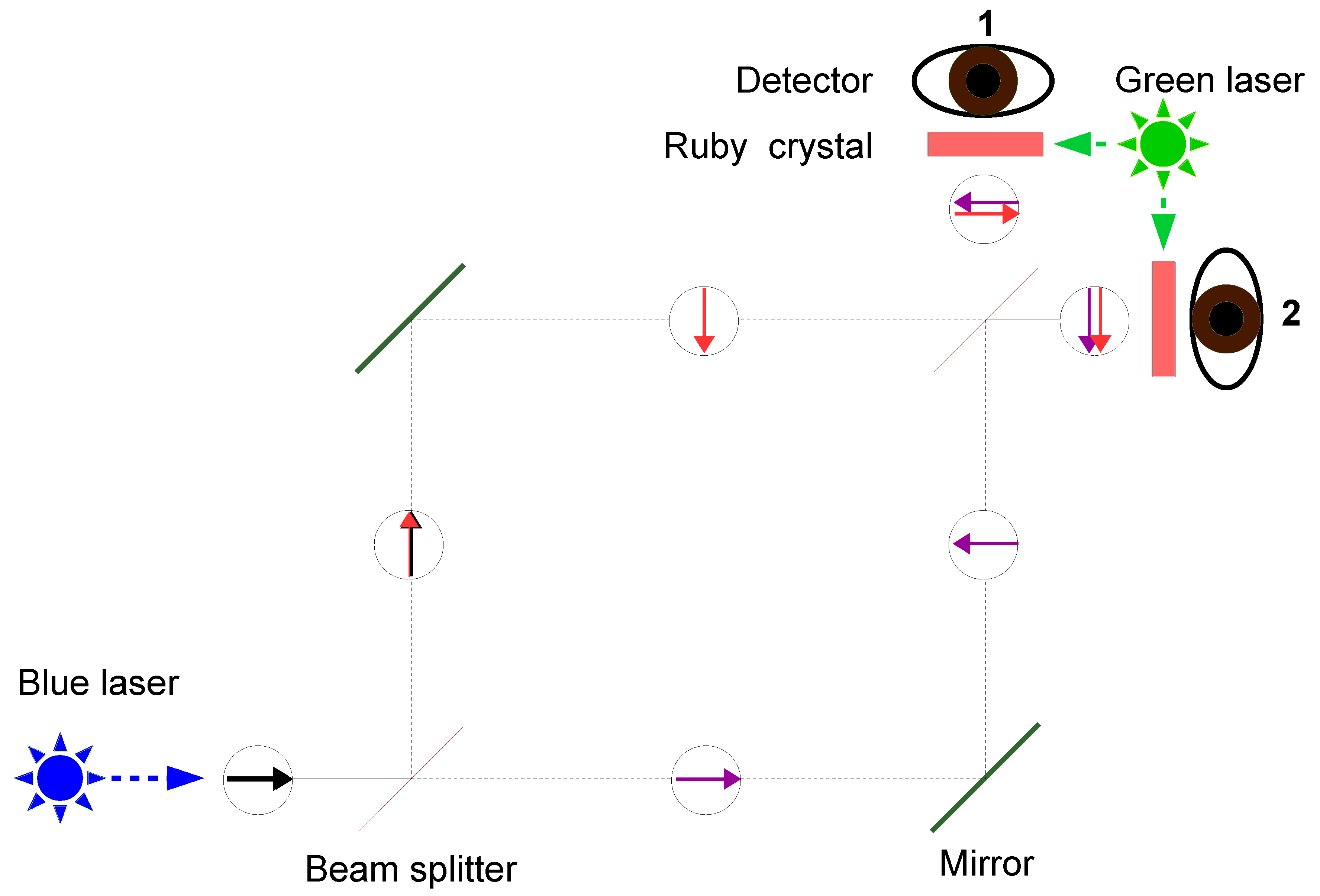

A potentially better alternative is therefore an experimental setup based on a Mach–Zehnder interferometer, as shown in

Figure 7. Immediately in front of each of the two detectors, a ruby crystal is placed, which can be illuminated laterally by green laser light. When the green lasers are switched off, Detector 2 will respond, while Detector 1 will not. If both ruby crystals are illuminated by green light, the result should be reversed. Particularly interesting is the case in which only one of the ruby crystals is illuminated by green laser light.

The theory developed here deviates significantly from the mainstream, and it is therefore unlikely that this experiment will ever actually be performed. However, should it be carried out, and should it yield the expected result, the magnitude of the shift in the interference pattern could be used to determine precisely the phase change of the blue light caused by the absorption of green photons.

This would allow one to demonstrate that the event complementary to stimulated emission is indeed absorption—a fact that is by no means self-evident [

28]. Finally, such a result would call into question both the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory (in particular, the view that particles such as photons interfere with themselves), as well as the

hierarchical orbital model. At the same time, it would provide support for the core idea of De Raedt et al. (2005).