1. Introduction

Endoscopy is the primary method for diagnosing and managing gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding; however, transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) serves as a valuable non-surgical alternative when the bleeding source is inaccessible to endoscopy or cannot be treated endoscopically.[

1,

2] TAE is performed using the most appropriate embolic material, selected based on the bleeding pattern and the feasibility of selectively targeting the affected vessel. The risk of bowel ischemia or infarction varies depending on the embolic material used. Bowel ischemia or infarction following TAE is more frequently observed in the lower GI tract, which has fewer collateral vessels than the upper GI tract [

3,

4]. An animal study in pigs reported that the risk of substantial bowel ischemic changes increases when four or more vasa recta are occluded by NBCA [

5]. For gelatin sponge particles (GSPs), Bua-Ngam et al. treated 27 patients with lower GI bleeding using standard GSPs, and 4 patients (14.8%) developed bowel ischemic complications [

6].

Quick-soluble GSP (QS-GSP), which dissolves more rapidly than conventional GSP, has been shown to reduce skin ischemic injury in genicular artery embolization for knee osteoarthritis [

7]. Based on this principle, temporary embolic agents such as QS-GSP for GI bleeding can embolize the bleeding focus, providing time for healing while subsequently dissolving to restore blood flow and prevent ischemic complications. In a study involving 10 patients with angiographically negative bleeding in the upper and lower GI tract, no bowel ischemic complications were reported following QS-GSP embolization [

2]. The prior study focused primarily on angiographically negative bleeding, likely due to concerns about the efficacy of temporary embolic agents in cases of active extravasation, and also included the upper GI tract, where the risk of ischemic injury is relatively low. However, further evaluation is needed to assess the effectiveness of these agents in addressing active bleeding foci and their safety in the ischemia-prone lower GI tract. To explore these concerns further, this study evaluated the safety and effectiveness of QS-GSP embolization for lower GI bleeding, regardless of the presence of a bleeding focus.

2. Materials and Methods

This multicenter retrospective study was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions, with a waiver of the requirement for written informed consent due to its retrospective nature. All research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The data were accessed on 13 February 2025 after the Ethics Committee’s approval. All data were fully anonymized before being accessed by the investigators. The study included 29 patients (20 men; mean age, 64.9 ± 12.9 years; range, 21–82 years) who underwent TAE with QS-GSP for acute nonvariceal lower GI bleeding between September 2021 and November 2024. Acute nonvariceal GI bleeding was defined as hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia originating from nonvariceal sources and occurring within 24 hours before angiography.

Electronic medical records, laboratory findings, and endoscopic and/or radiologic features were reviewed. The following data were collected for each patient: clinical information, including symptoms and signs of GI bleeding; coagulopathy; hemodynamic instability; the identified cause of GI bleeding; the time interval between GI bleeding onset and TAE; history of previous treatment; angiographic findings and TAE procedure details; hemoglobin levels before and within two days following TAE; clinical outcomes; and procedure-related complications.

2.1. TAE Procedure

All TAE procedures were performed in an interventional radiology suite by more than ten interventional radiology specialists from the four participating institutions. Each specialist had 5 to 25 years of experience. Procedures were conducted under fluoroscopic guidance. A 5-F vascular sheath was inserted into the right common femoral artery, followed by the introduction of a 5-French catheter (RH catheter; Cook, Inc., Bloomington, IN, USA) over a 0.035-inch guidewire (Radifocus; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) through the sheath. Superior and inferior mesenteric angiography was performed based on the location of the bleeding focus. Superselective angiography was then conducted using 2- to 2.4-French microcatheters (Progreat; Terumo, or Radiomate; S&G Biotech, Yongin, Korea) to identify the bleeding site, as determined by the location shown on computed tomography (CT) and, if available, endoscopy.

In cases where active bleeding was observed on angiography but superselective embolization was not feasible, a broader embolization approach was used. Embolization was then performed at the site closest to the bleeding focus. If no active bleeding was detected, prophylactic embolization was conducted, targeting the suspected bleeding site based on findings from endoscopy or CT scans. QS-GSPs (K-IPZA®; Engain, Hwaseong, Korea) were used as the embolic agent. These QS-GSPs dissolve completely within four hours upon contact with saline or blood.

2.2. Definitions and Analytic Items

Coagulopathy was defined as a prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PT-INR) greater than 1.5 or thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of less than 50,000/μL. Hemodynamic instability was defined as a systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg. Technical success was defined as the occlusion or stasis of blood flow in the target artery, as observed on the angiogram obtained immediately after TAE. Clinical success was defined as the cessation of bleeding symptoms with hemodynamic stability during the week following TAE, without major procedure-related complications. Clinical failure was defined as the presence of one or more of the following three conditions within one week after the initial TAE: persistent bleeding (ongoing bleeding despite TAE), recurrent bleeding at the same site within one week after the initial successful hemostasis achieved by TAE, and procedure-related major complications.

Electronic medical records, follow-up endoscopy reports, and post-TAE CT scans were reviewed to assess the presence of procedure-related complications, such as bowel ischemia or infarction. Procedure-related complications were classified according to the Society of Interventional Radiology clinical practice guidelines. Major complications were defined as those requiring further treatment or prolonged hospitalization, while minor complications were those that resolved spontaneously [

8]. To determine whether clinical success differed between patients with and without active bleeding, Fisher’s exact test was used. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed to compare hemoglobin levels before and after TAE. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

The primary clinical manifestations included hematochezia (n = 23), melena (n = 4), and both (n = 2). Bleeding sites were identified in the jejunum (n = 7), ileum (n = 7), ileocolic anastomosis (n = 1), cecum (n = 2), colon (n = 7), and rectosigmoid region (n = 5). The underlying causes of bleeding included: diverticular bleeding (n = 6), ulceration (n = 5), metastatic (n = 2) or lymphomatous (n = 2) involvement of the jejunum or ileum, postoperative bleeding (n = 1), colitis (n = 1), hemorrhoidal bleeding (n = 1), graft-versus-host disease (n = 1), and an indeterminate cause (n = 10).

The diagnosis of lower GI bleeding was established using endoscopy (n = 10), CT imaging (n = 13), or a combination of both (n = 5). In one patient, bleeding was detected via a red blood cell (RBC) scan. Six patients had a history of prior GI bleeding treatments, including endoscopic clipping with or without epinephrine injection (n = 4), TAE (n = 1), and small bowel resection with TAE (n = 1).

The median time between GI bleeding onset and TAE intervention was 1 day (range, 1–10 days). Coagulopathy was observed in three patients, and four patients experienced hemodynamic instability.

3.2. Details of TAE

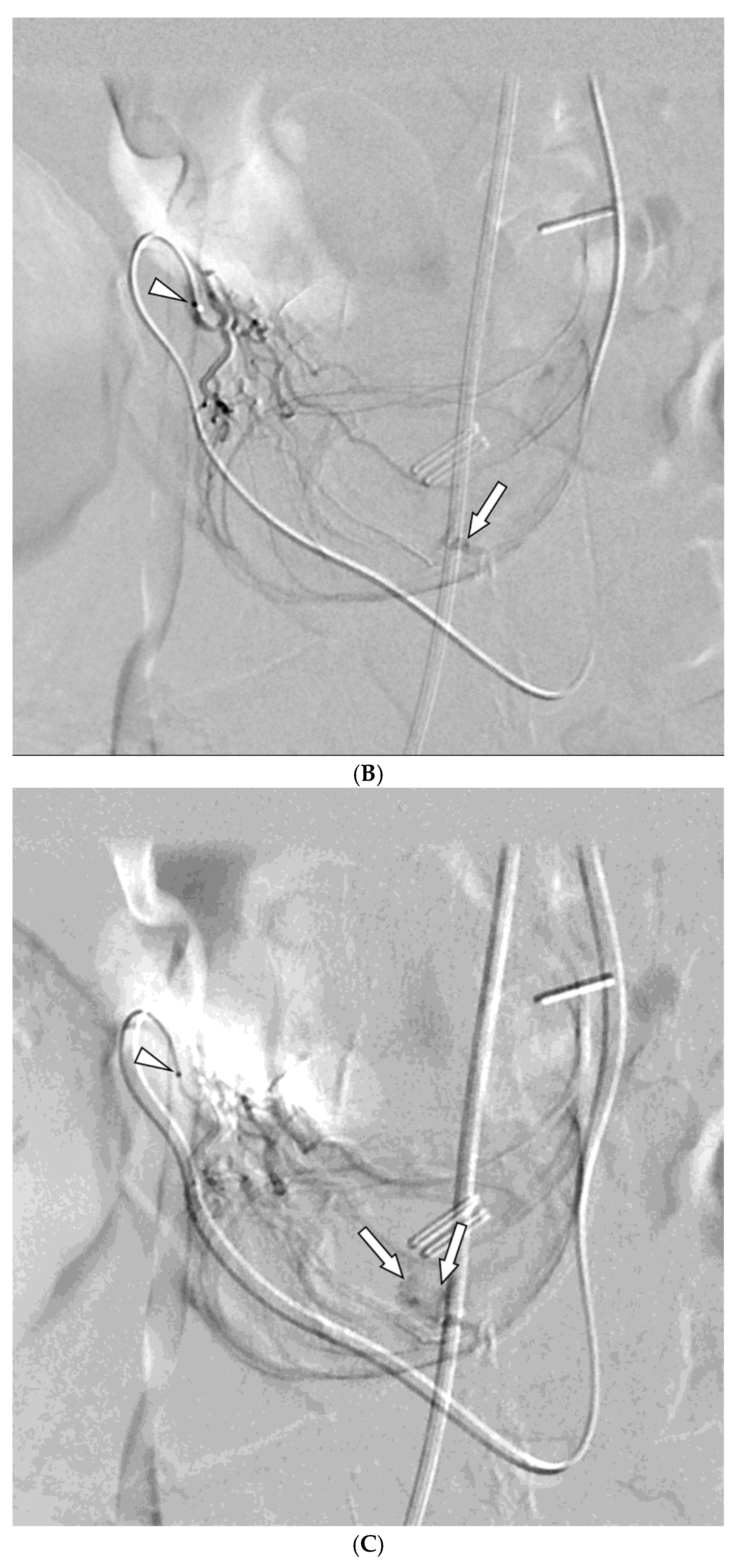

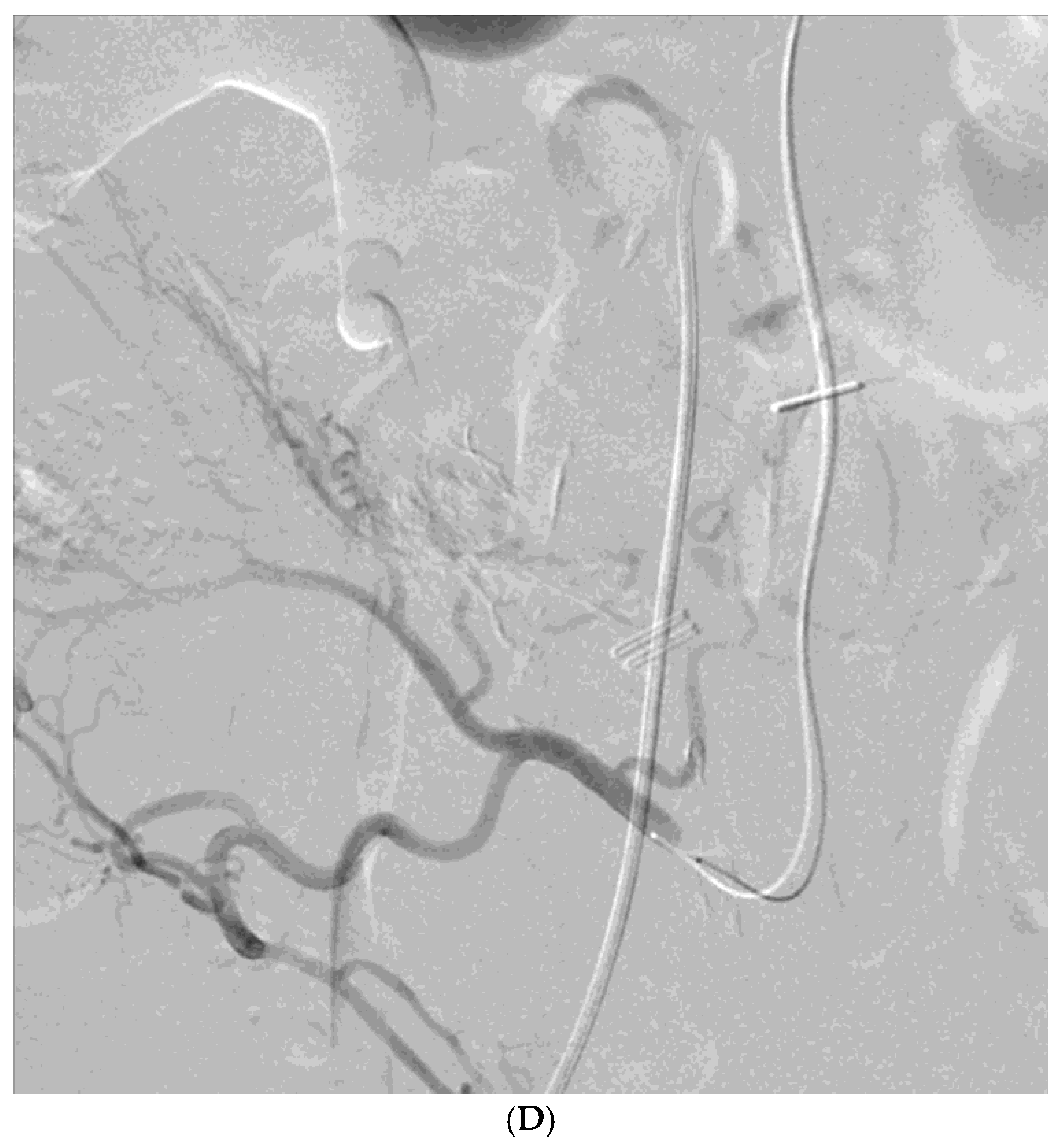

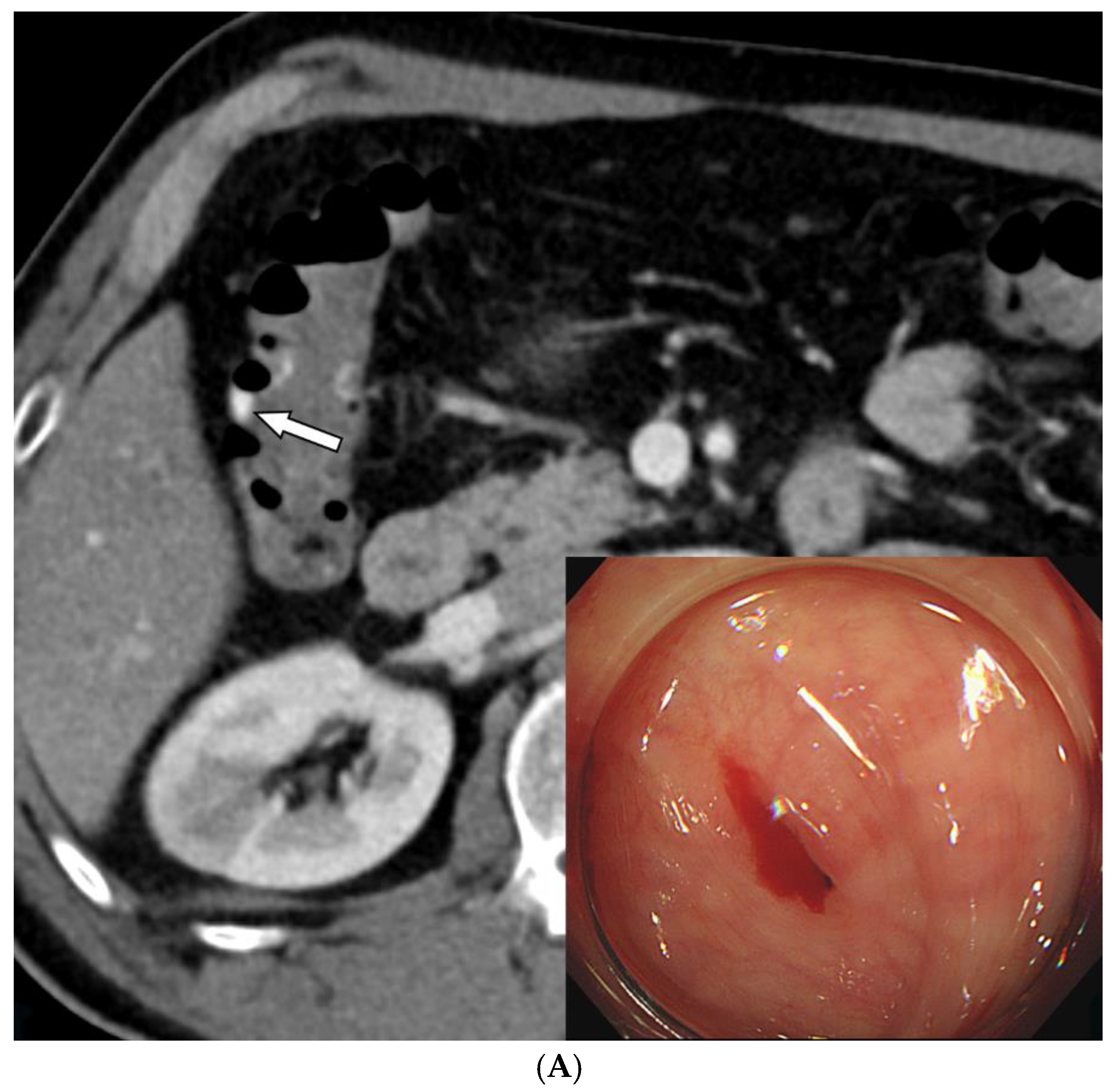

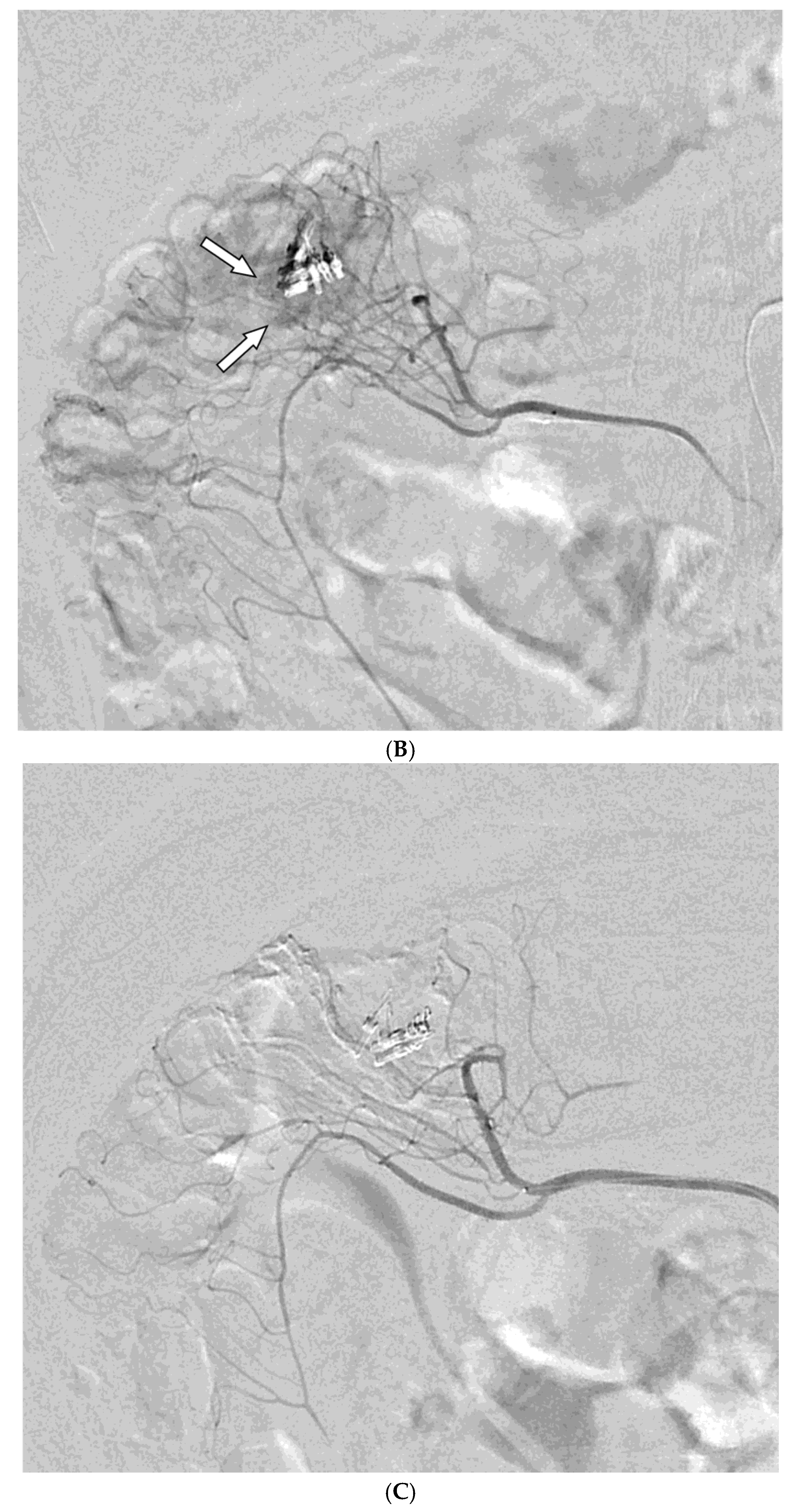

Among the 29 patients, active bleeding was identified on angiography in six patients (20.7%, 6/29), and tumor staining was observed in two patients (6.9%, 2/29). However, the bleeding focus involved tortuous or small vessels that could not be selectively catheterized; therefore, QS-GSP was administered from a more proximal location (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). No evidence of bleeding or tumor staining was detected on angiography in the remaining 21 patients, where the target artery for embolization was determined based on endoscopic and/or CT findings, with angiography serving as a reference (

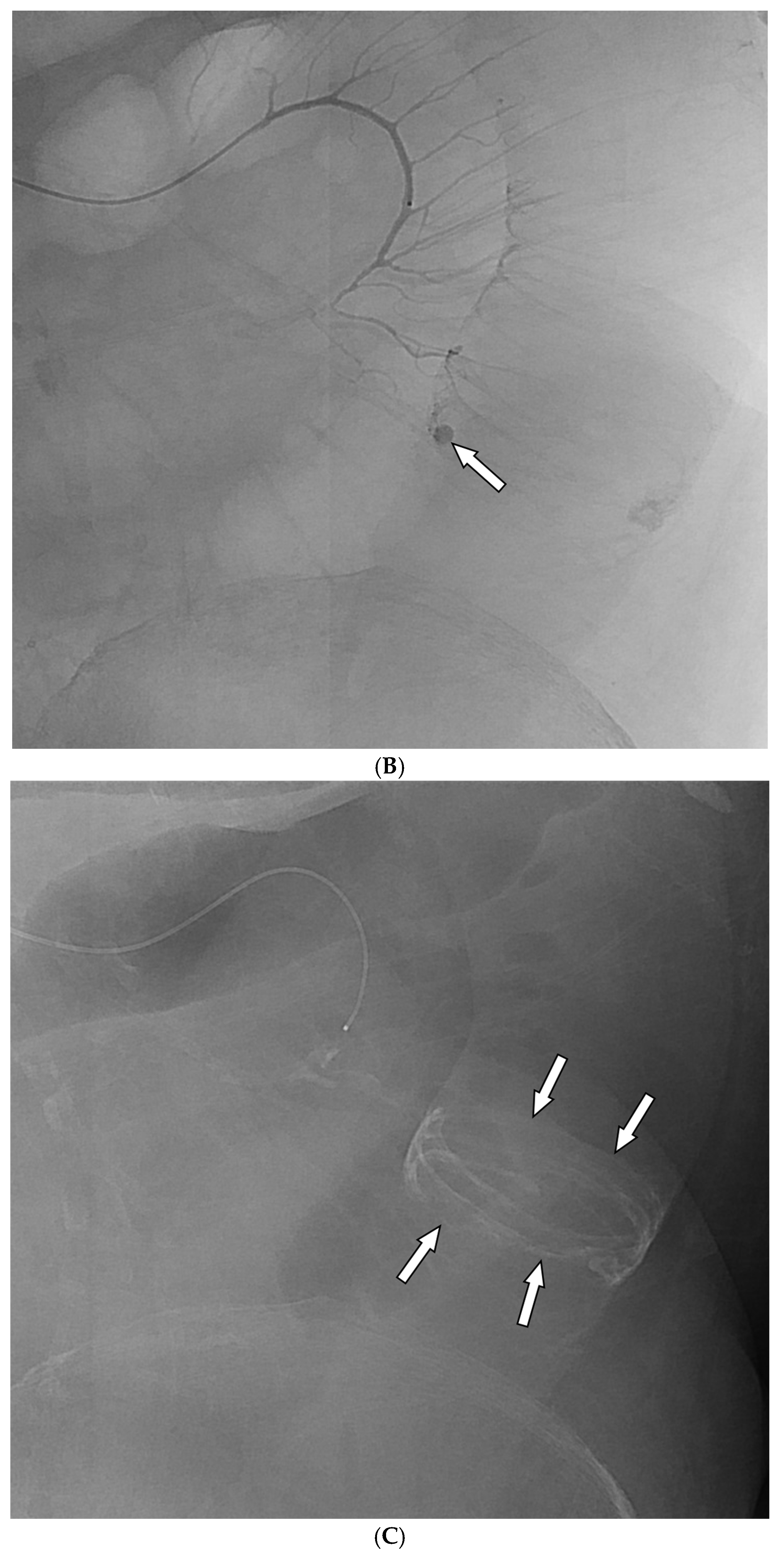

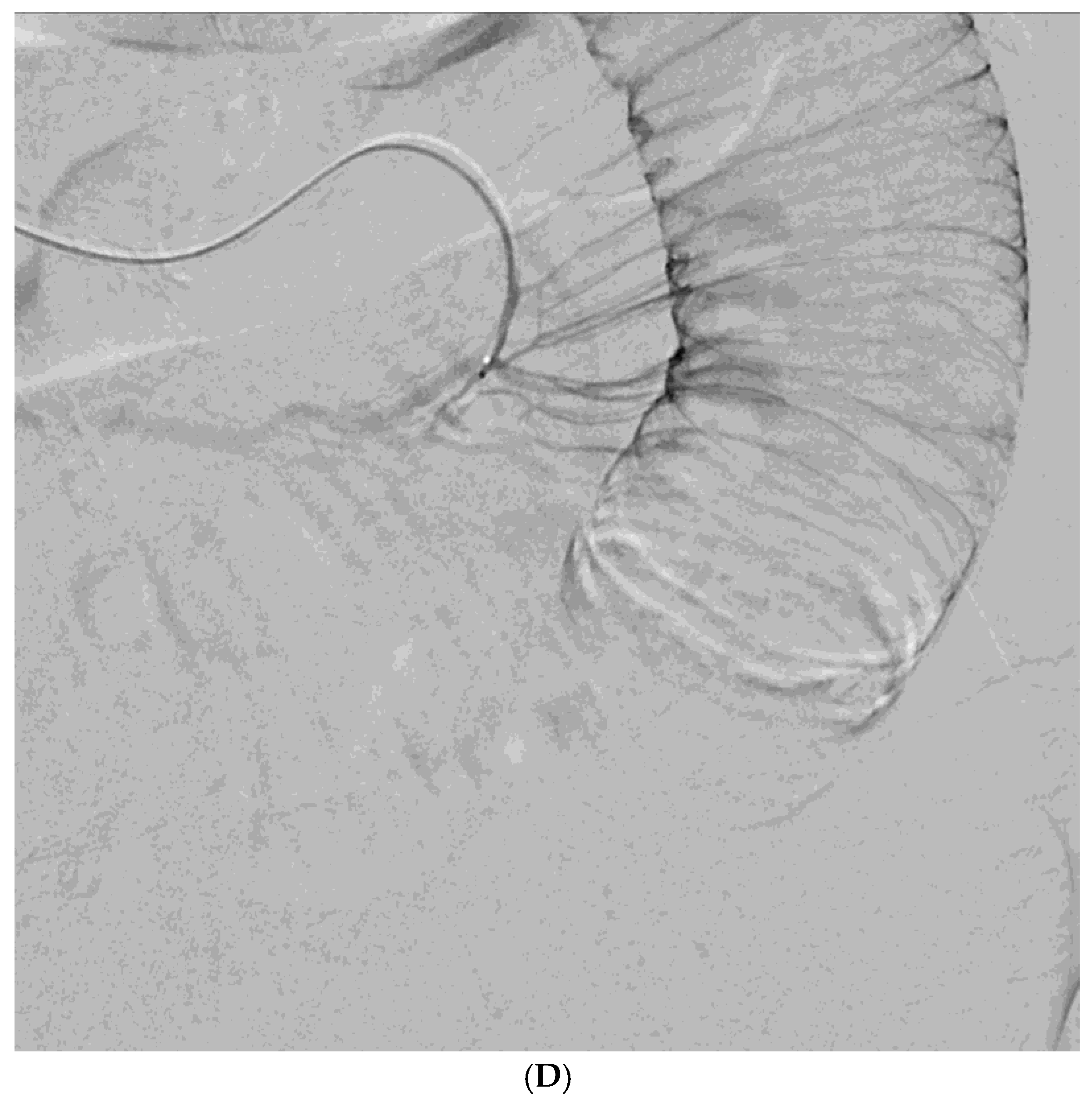

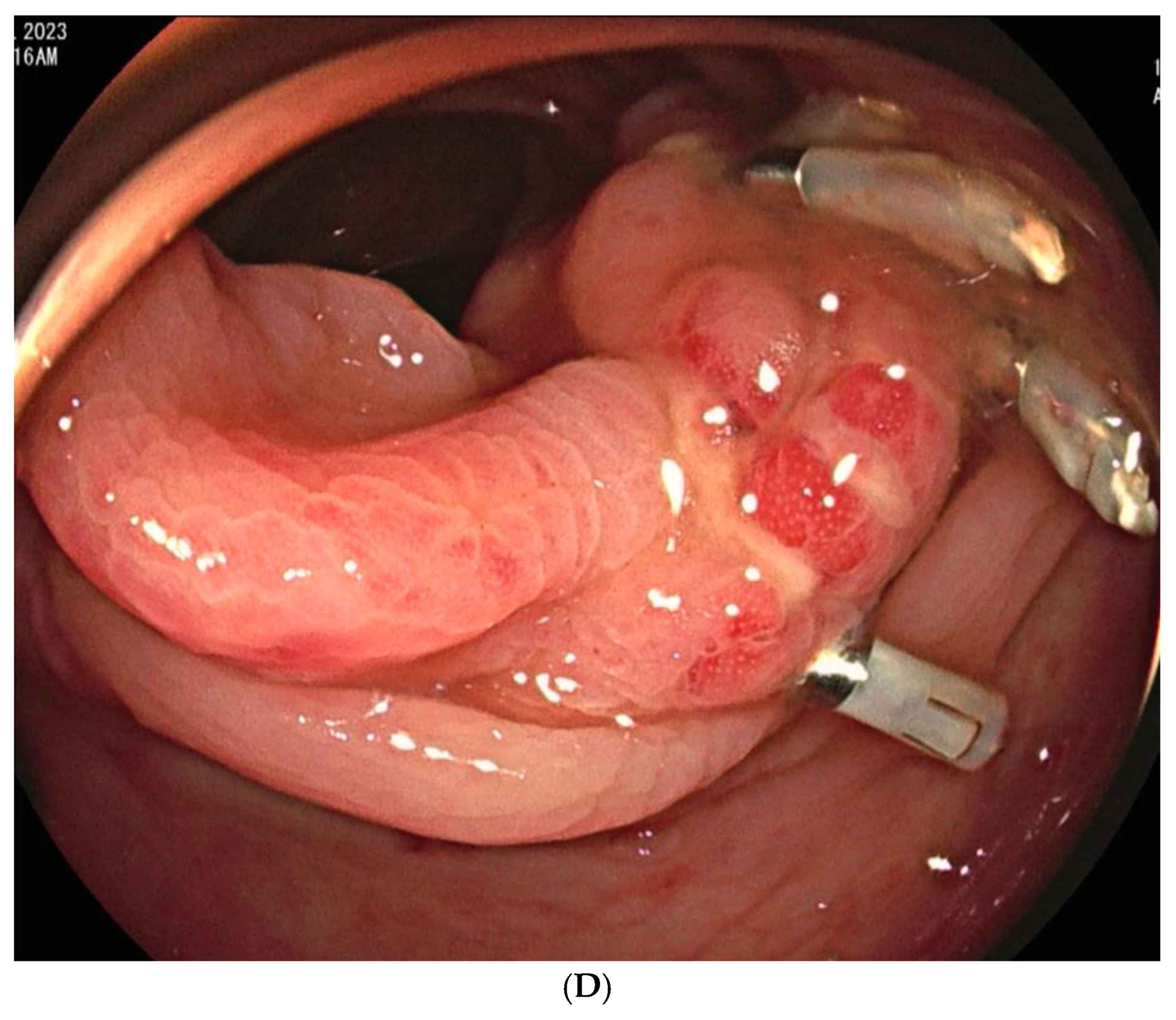

Figure 3).

Embolization was performed on the following arteries: jejunal (n = 7), ileal (n = 7), ileocolic anastomotic (n = 1), cecal (n = 2), colic (n = 7), and rectosigmoid (n = 5). QS-GSPs (150–350 μm, n = 10; 350–560 μm, n = 19) were used as the sole embolic agents in all patients. Angiography following TAE confirmed occlusion or stasis of flow in the target artery in all patients, resulting in a 100% technical success rate.

3.3. Outcomes of TAE

During a follow-up period of 1 to 34 months (median, 4.5 months) post-TAE, clinical success was achieved in 22 patients (75.9%, 22/29), while clinical failure was observed in seven (24.1%, 7/29), including four with persistent bleeding after TAE and three with recurrent bleeding at the same site two, four-, and five-days post-TAE. Details of seven patients with clinical failure are provided in

Table 1.

Procedure-related complications, including transient bowel ischemia, were observed in two patients and were classified as minor procedure-related complications. (6.9%,

Figure 3). Transient ischemia of the rectum or ascending colon was confirmed via colonoscopy one and two-days post-TAE, respectively. However, the transient ischemia of the rectum improved on endoscopy after three days, and the abdominal pain associated with ischemia of the ascending colon resolved within three days.

Among the six patients with active bleeding on angiography, clinical success was achieved in four (66.7%), while among the 23 patients without active bleeding, clinical success was observed in 17 (73.9%). No significant difference was found between the groups (P = 1). The median hemoglobin level increased from 7.4 ± 1.73 to 9.5 ± 1.22 g/dL (P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

In a previous preliminary report [

2], QS-GSP embolization was assessed for angiographically negative GI bleeding in both the upper and lower GI tracts in a small cohort of patients. However, the present study focuses on a larger cohort of patients with only lower GI bleeding, where the risk of bowel ischemic complications is expected to be higher. In this study, the rate of successful bleeding control without further bleeding during the week following TAE, referred to as clinical success, was 75.9%. These findings are consistent with those observed in a cohort of 112 patients with lower GI bleeding, where GSP was the primary embolic agent (administered to 20 of 24 patients), and the rebleeding rate was 25% [

4]. A four-hour occlusion by QS-GSP seems sufficient to achieve effective hemostasis. While initial clot formation with platelet aggregation occurs rapidly within minutes, full stabilization, where the fibrin network reinforces the initial plug and secures the vessel against shear forces, typically develops over several hours. This suggests that a temporary occlusion of about four hours, as provided by QS-GSP, may be sufficient to allow the formation of a stable clot, particularly when compared to the longer durations required for irreversible mucosal ischemia.

Bowel ischemic complications, classified as minor procedure-related complications, were observed in only 2 of 29 patients (6.9%) in this study, and these complications resolved spontaneously within a few days. While reports on bowel ischemic changes following GSP-based TAE for lower GI bleeding are limited, one study reported that among 20 patients who received standard GSP embolization for lower GI bleeding, 1 patient (5%) died due to small bowel infarction and subsequent postoperative complications [

4]. Another study reported that 4 of 27 patients (14.8%) with lower GI bleeding experienced bowel ischemic complications following standard GSP embolization [

6]. In comparison, the 6.9% incidence of bowel ischemic changes observed in this study is acceptable. Furthermore, the spontaneous resolution within several days suggests that QS-GSP is relatively safe, even in the lower GI tract, where collateral circulation is limited.

In contrast, animal experiments have demonstrated that occlusion of four or more vasa recta by NBCA increases the risk of bowel ischemic complications [

5]. Despite the expectation that QS-GSP, as a particulate embolic agent, may occlude a larger area, it resulted in fewer bowel ischemic changes, indicating that it is a highly safe agent for embolization in lower GI bleeding. Although ischemic complications in the small bowel may be difficult to confirm endoscopically, potentially leading to underreporting, major complications such as bowel infarction are clinically detectable, making it unlikely that severe complications would be underestimated.

The diameter of the arteries supplying the small bowel, as measured in cadaveric samples, ranges from 560 to 770 μm, while angiographic measurements range from 500 to 600 μm, yielding an approximate range of 500–800 μm [

9,

10]. The diameter of the arteries supplying the large bowel, as measured by angiography, ranges from 400 to 500 μm, which is slightly smaller than that of the small bowel [

9]. Therefore, the particle size of QS-GSP used in this study, which ranges from 150 to 560 μm, is considered appropriate for embolizing the vasa recta in both the small and large bowels. The absence of bowel infarction despite this particle size may be attributed to the resorbable nature of QS-GSP, which dissolves within four hours. It is well established that complete acute occlusion of the enteric blood supply leads to irreversible mucosal ischemia within approximately six hours [

11], suggesting that the dissolution of QS-GSP within four hours makes permanent infarction unlikely. Consequently, even with embolization of relatively large areas involving multiple vasa recta, permanent infarction is not expected to occur. However, the optimal degradation time for temporary embolic agents remains unclear. Longer degradation times may reduce the risk of rebleeding due to recanalization but increase the risk of ischemic complications, whereas shorter degradation times have the opposite effect.

In a previous preliminary study, no patients with active bleeding were included [

2]. However, in this study, 20.7% of patients presented with active bleeding. In cases of active bleeding, permanent embolic materials are typically used if superselective embolization is feasible. However, when arterial feeders are narrow or highly tortuous, making superselective embolization with a microcatheter unfeasible, traditional embolic agents may increase the risk of bowel ischemic complications. In contrast, QS-GSP is expected to present a significantly lower risk of bowel ischemic complications, making it a promising option for active bleeding cases in which superselective embolization is not achievable. Furthermore, the lack of a significant difference in clinical success between the active bleeding and non-active bleeding groups in this study suggests that QS-GSP may be a viable option even in cases of active bleeding.

This study had a few limitations. First, it was a retrospective study with a relatively small sample size. Second, because the study was multicenter in design, the patient population was heterogeneous, and slight variations in the study protocol and procedural details may have existed between hospitals. Third, embolization-related adverse events, such as bowel ischemia or infarction, were primarily assessed through clinical records, and colonoscopy was performed only in selected patients after embolization to evaluate bowel ischemic complications.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, TAE with QS-GSP for acute lower GI bleeding was found to be safe, with a clinical success rate exceeding 75%. Transient bowel ischemia occurred in 6.9% of patients, but no cases of bowel infarction were observed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.H.J. and S.B.Y.; Methodology, J.H.S.; Validation, J.H.S., C.H.J., and S.B.Y.; Formal Analysis, C.H.J.; Investigation, C.H.J., S.B.Y., W.J.Y., J.H.S., K.K., J.H.P., and J.H.K.; Resources, J.H.S.; Data Curation, C.H.J. and S.B.Y.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.H.J.; Writing—Review & Editing, J.H.S.; Visualization, C.H.J.; Supervision, J.H.S.; Project Administration, J.H.S.; Funding Acquisition, J.H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by The Technology Innovation Program (or Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program) (20017903, Development of medical combination device for active precise delivery of embolic beads for transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and simulator for embolization training to cure liver tumor) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by all four participating hospitals (Eunpyeong St. Mary’s Hospital-PC25RIDI0031, Nowon Eulji Medical Center-EMCS2025-07-016, Korea University Guro Hospital-2025GR0186, Asan Medical Center-S2023-2007-0001).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shin, JH. Recent update of embolization of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Korean J Radiol. 2012;13 Suppl 1:S31-9.

- Alali M, Cao C, Shin JH, Jeon G, Zeng CH, Park J-H, et al. Preliminary report on embolization with quick-soluble gelatin sponge particles for angiographically negative acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Scientific Reports. 2024;14:6438. [CrossRef]

- Ini’ C, Distefano G, Sanfilippo F, Castiglione DG, Falsaperla D, Giurazza F, et al. Embolization for acute nonvariceal bleeding of upper and lower gastrointestinal tract: a systematic review. CVIR Endovascular. 2023;6:18.

- Hur S, Jae HJ, Lee M, Kim HC, Chung JW. Safety and efficacy of transcatheter arterial embolization for lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a single-center experience with 112 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:10-9. [CrossRef]

- Jae HJ, Chung JW, Kim HC, So YH, Lim HG, Lee W, et al. Experimental study on acute ischemic small bowel changes induced by superselective embolization of superior mesenteric artery branches with N-butyl cyanoacrylate. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:755-63.

- Bua-Ngam C, Norasetsingh J, Treesit T, Wedsart B, Chansanti O, Tapaneeyakorn J, et al. Efficacy of emergency transarterial embolization in acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: A single-center experience. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2017;98:499-505. [CrossRef]

- Min J, Park SW, Hwang JH, Lee JK, Lee DW, Kwon YW, et al. Evaluating the Safety and Effectiveness of Quick-Soluble Gelatin Sponge Particles for Genicular Artery Embolization for Chronic Knee Pain Associated with Osteoarthritis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2023;34:1868-74.

- Omary RA, Bettmann MA, Cardella JF, Bakal CW, Schwartzberg MS, Sacks D, et al. Quality improvement guidelines for the reporting and archiving of interventional radiology procedures. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:879-81.

- Koganemaru M, Abe T, Iwamoto R, Kusumoto M, Suenaga M, Saga T, et al. Ultraselective arterial embolization of vasa recta using 1.7-French microcatheter with small-sized detachable coils in acute colonic hemorrhage after failed endoscopic treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:W370-2. [CrossRef]

- Conley D, Hurst PR, Stringer MD. An investigation of human jejunal and ileal arteries. Anat Sci Int. 2010;85:23-30.

- Klar E, Rahmanian PB, Bücker A, Hauenstein K, Jauch KW, Luther B. Acute mesenteric ischemia: a vascular emergency. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:249-56. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).