1. Introduction

Chronic stress contributes to obesity through

multiple interconnected eating behavior changes [1] .

Stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to

elevated cortisol levels that stimulate hunger and increase preference for

energy-dense "comfort foods" high in fat, sugar, and calories [1–3] . These hormonal changes are accompanied by

alterations in appetite-regulating hormones, including increased ghrelin

secretion and reduced sensitivity to leptin and insulin, which collectively

promote hyperphagia and disrupt normal satiety signaling [1,2,4] . Meta-analytic evidence from 54 studies

(N=119,820) demonstrates that stress systematically increases intake of

unhealthy, energy-dense foods (Hedges' g = 0.116) while significantly

decreasing consumption of nutritious options (Hedges' g = -0.111) [5] . Importantly, consuming highly palatable foods

provides temporary relief by suppressing stress responses and activating reward

systems through negative feedback mechanisms that dampen HPA axis activity [1,6] . Stress also enhances brain reward pathways,

particularly sensitizing the nucleus accumbens and increasing dopamine-mediated

food seeking, while simultaneously impairing executive function and

self-regulatory capacity [1] . This process

creates a reinforcing cycle in which stress-induced eating becomes a learned

coping strategy, with repeated consumption of comfort foods strengthening these

maladaptive behavioral patterns [2,6] .

Therefore, it is crucial to understand how stress-related changes lead to

distinct maladaptive eating behaviors—especially emotional eating and binge

eating—that differ in their psychological mechanisms, clinical significance,

and metabolic consequences.

Among the maladaptive eating patterns, emotional

eating and binge eating are recognized as critical pathways linking stress to

obesity. Emotional eating is characterized by consuming food in response to

emotional states rather than physiological hunger, serving as a coping

mechanism to regulate negative affect such as stress, anxiety, or depression [7,8] . In contrast, binge eating involves consuming

objectively large amounts of food within a discrete time period (e.g., in 2

hours) accompanied by a subjective sense of loss of control over eating [9] . While emotional eating typically involves

frequent episodes of modest food intake to cope with distress, binge eating

reflects a more severe and dysregulated pattern of intake, often followed by

intense guilt or shame [9] . Importantly, binge

eating is not only more behaviorally extreme but also constitutes a core

diagnostic symptom of eating disorders such as binge eating disorder (BED).

These behaviors differ not only in their severity and expression but also in

their neurobiological underpinnings: emotional eating is primarily associated

with limbic system activation for emotion regulation, whereas binge eating is

linked to prefrontal disinhibition and impaired executive control. [1,9] .

Emotional eating serves as a well-established

mediator of the relationship between perceived stress and obesity-related

outcomes [8] . For instance, in a large-scale

cross-sectional study of U.S. adults, stress-related eating was found to fully

mediate the link between stressful life events and key obesity markers like

waist circumference and BMI [10] . This finding

is consistent across different populations, with a study of multinational

university students similarly demonstrating that emotional eating mediated the

pathway from perceived stress to higher BMI [11] .

The mediating role of emotional eating is also evident in high-stress

populations, such as U.S. Army Soldiers, where it connected perceived stress to

both increased BMI and body composition failure [12] .

Furthermore, this mechanism appears to influence not just weight but also

dietary choices, as emotional eating partially mediated the relationship

between perceived stress and poorer dietary quality in a study of

Hispanic/Latino adolescents [13] .

Binge eating, likewise, has been identified as

another critical pathway in the stress–obesity link, with some evidence

suggesting it may be a more potent mediator than emotional eating. For example,

Chao and colleagues reported that although both behaviors were linked to

stress, only binge eating showed a significant relationship with increased

waist circumference in a sample of adult women. [14] .

The robustness of this pathway is strengthened by longitudinal evidence; a

study of sexual-minority women demonstrated that binge eating mediated the

relationship between baseline post-traumatic stress symptoms and higher BMI two

years later [15] . The clinical significance of

this link is further underscored in behavioral weight loss intervention

studies, where eating disorder pathology mediated the effect of stress on

weight loss specifically within the subgroup of patients with regular binge eating

[16] . Finally, mechanistic studies using

moderated mediation have begun to clarify how this occurs, showing that stress

is associated with increased likelihood of binge eating through maladaptive

coping strategies [17] .

Despite their distinctions, a growing body of

theoretical and empirical evidence suggests that emotional eating and binge

eating may lie on a single severity continuum, wherein emotional eating can

progress to clinically significant binge eating [9,18] .

This progression is theoretically grounded in Davis's ‘overeating continuum

model’ [18] , which posits that overeating

behaviors initially used to 'self-medicate' negative affect—a core functional

definition of emotional eating—can escalate in severity and compulsiveness

toward full-blown binge eating. This theoretical model is bolstered by

converging lines of empirical evidence. For instance, a longitudinal study with

adolescent girls has shown that baseline emotional eating significantly

predicts the onset of binge-eating symptoms over a two-year period (hazard

ratio ≈ 1.8) [19] .

This progression is also supported by a cross-sectional study of overweight

adults, which found that emotional eating scores increase progressively from

non-binge eaters to individuals with full Binge Eating Disorder (BED) [20] . Furthermore, mechanistic insight from a study

using ecological momentary assessment demonstrates that a failure to

down-regulate negative affect after an emotional eating episode can create a

self-reinforcing loop, precipitating full binge episodes. [21] . Finally, mediation studies in adults with

trauma exposure have confirmed that emotional eating is a key pathway linking

post-traumatic stress to binge eating [22] .

Collectively, this evidence aligns with the overeating continuum model and

points to a potential sequential pathway from stress to obesity, where

emotional eating develops into binge eating.

Prior research has established that both emotional

eating and binge eating are independent mediators in the stress-obesity

relationship. However, the sequential pathway suggested by the 'overeating

continuum model'—wherein emotional eating escalates into binge eating—has yet

to be empirically tested within a single, integrated framework. To address this

critical gap, this study tested a serial mediation model hypothesizing that

perceived stress increases BMI sequentially, first through emotional eating and

then through binge eating. The present cross-sectional analysis tests a

statistical model representing this hypothesized pathway, providing initial

evidence. The findings are expected to help clarify the distinct roles of

emotional and binge eating, potentially informing the development of more

precise intervention targets.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study was approved by the Institutional Review

Boards of Pusan National University (PNU IRB 2023-18-HR, PNU IRB 2024-148-HR),

and all participants provided informed consent in the present study.

Participants were recruited from the Korean adult population aged 19 to 59

years. Pregnant individuals were excluded due to potential effects on body

weight and dietary behaviors. Recruitment mostly occurred online through

advertisements posted on university internet boards and popular mobile and

messaging apps, while offline recruitment was limited to poster placements on

local university campuses.

Demographic information including gender, age,

years of education, height, and weight was collected via self-report. Of the

289 individuals initially screened, 17 participants with a BMI below 18.5 kg/m

2

were excluded from the analysis. The final analytic sample thus comprised 272

individuals, consisting of 96 normal-weight, 39 pre-obese, and 137 obese

individuals according to the diagnostic criteria in the Clinical Practice

Guidelines of the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity [23] . Among these 272 participants, 115 were male

(42.3%). The age distribution included 156 participants aged 29 years or younger

(57.4%), 108 participants in their 30s (39.7%), and 8 participants in their 40s

(2.9%). Additional demographic information is presented in

Table 1.

2.2. Clinical Questionnaires

2.2.1. Perceived Stress

Perceived stress levels were measured using the

10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) [24] ,

which employs a 5-point Likert-type response format ranging from 0 to 4. Higher

total scores indicate greater perceived stress. The Korean validation of the

PSS yielded satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha

coefficients of .82 [25] , and the present

study estimated Cronbach’s alpha as .85.

2.2.2. Emotional Eating

Emotional eating was assessed with the Dutch Eating

Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ), which comprises three subscales: emotional

eating, external eating, and restrained eating [26] .

Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 ('never') to 5

('very often'), with higher scores reflecting a greater tendency toward each

eating behavior. This study focused solely on the emotional eating subscale,

which consists of 13 items. The Korean version of the DEBQ emotional eating

subscale showed good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values of .92

in prior research [27] and .93 in this study.

2.2.3. Binge Eating

Binge eating severity was evaluated using the Binge

Eating Scale (BES), a widely employed 16-item self-report instrument [28] . Items are scored on either a 0–2 or 0–3 scale

depending on the item. Total scores are interpreted as follows: less than 18

indicates no binge eating symptoms; 18 to 26 indicates moderate binge eating;

and 27 or above indicates severe binge eating behavior. The Korean version of

the BES demonstrated good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha of .84 in

previous studies [29] and .90 in the present

study.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM

SPSS Statistics version 29.0. escriptive statistics (means and standard

deviations) and Pearson correlations were calculated for all study variables in

the full sample (see

Table 1). Gender was

coded as a binary variable (0 = female, 1 = male) for correlation analysis.

A serial mediation model was tested using Model 6

of the PROCESS macro version 4.2 for IBM SPSS Statistics [30] . Perceived stress (PSS) was entered as the

independent variable (X); emotional eating (DEBQ) and binge eating (BES) were

specified as mediators (M1 and M2); and BMI (kg/m2) was the

dependent variable (Y). Gender (1 = male, 0 = female), chronological age

(years), and years of education were included as covariates in the model.

Indirect effects were estimated using 10,000 bias-corrected bootstrap

resamples, and 95% percentile bootstrap confidence intervals were interpreted;

an effect was considered statistically significant if its confidence interval

did not include zero. Unstandardized regression coefficients (B), standard

errors (SE), confidence intervals, and standardized regression coefficients (β)

were reported. All analyses were conducted using the full sample (N = 272).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The study analyzed 272 participants, including 137

individuals classified as obese.

Table 2

presents the descriptive statistics and correlations for all study variables in

the full sample (N = 272). Bivariate Pearson correlation analyses showed that

BMI was positively correlated with emotional eating (r = 0.182, p < 0.01),

binge eating (r = 0.383, p < 0.001), and age (r = 0.214, p < 0.001).

Perceived stress was positively correlated with both emotional eating (r =

0.426, p < 0.001) and binge eating (r = 0.397, p < 0.001). Emotional

eating and binge eating were also strongly positively correlated (r = 0.621, p

< 0.001). Male gender was associated with higher perceived stress, emotional

eating, and binge eating (all p < 0.01).

3.2. Mediation Analysis

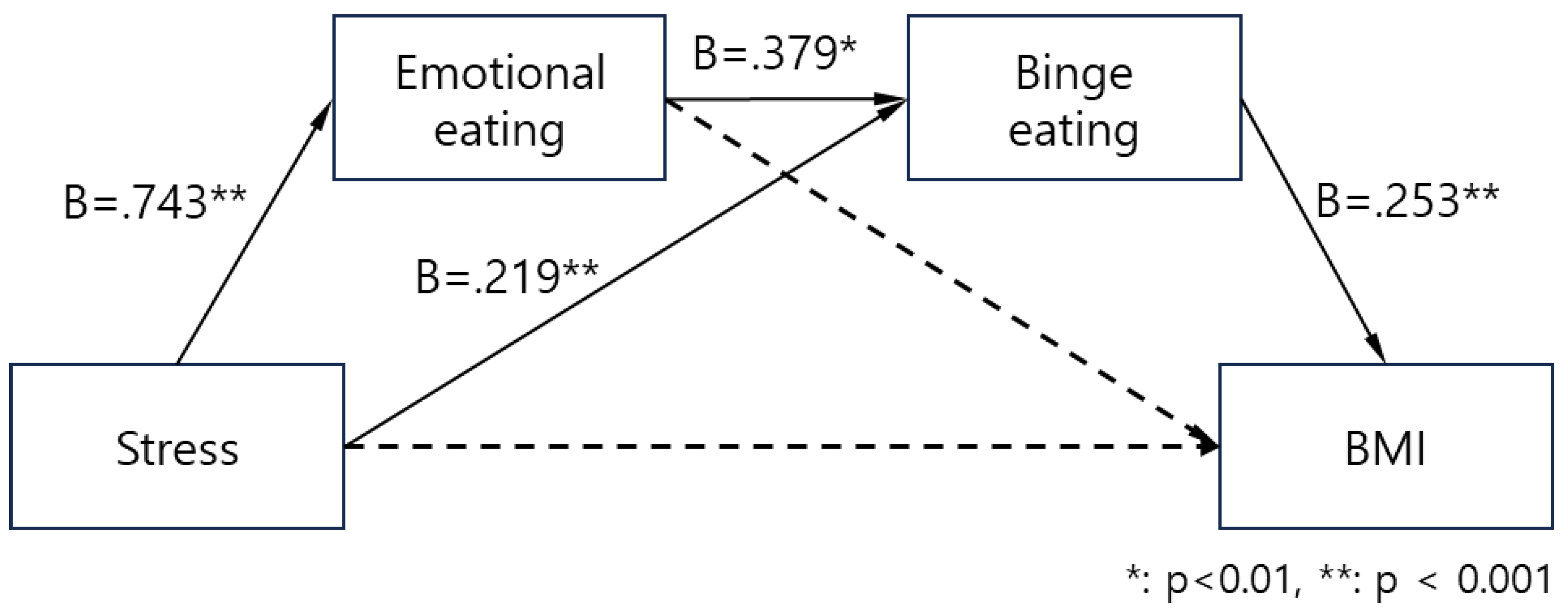

A serial multiple mediation analysis using PROCESS macro Model 6 was performed to examine whether emotional eating and binge eating sequentially mediate the effect of perceived stress on BMI, controlling for age, years of education, and gender. Regression coefficients are presented in

Figure 1 and

Table 2. Perceived stress was positively associated with emotional eating (B = 0.743, SE = 0.103, p < .001), and emotional eating significantly predicted binge eating (B = 0.379, SE = 0.039, p < .001). Perceived stress also had a direct positive effect on binge eating (B = 0.219, SE = 0.071, p = .002). In the final model predicting BMI, only binge eating showed a significant positive association with BMI (B = 0.253, SE = 0.041, p < .001). The effects of perceived stress (B = -0.016, p = .738) and emotional eating (B = -0.026, p = .393) on BMI were not significant, indicating full mediation.

The total effect of perceived stress on BMI was marginally significant (B = 0.091, SE = 0.047, p = .055). However, the direct effect became non-significant after inclusion of the mediators (B = -0.016, SE = 0.049, p = .738), indicating the presence of indirect effects.

Bootstrapping with 10,000 samples revealed a statistically significant total indirect effect of perceived stress on BMI (B = 0.108, Boot SE = 0.031, 95% CI [0.052, 0.172]; β = 0.137), as shown in Table 4. Among the three indirect pathways, the serial mediation path through emotional eating and binge eating was significant (B = 0.071, Boot SE = 0.018, 95% CI [0.041, 0.112]; β = 0.091), and the simple mediation path through binge eating alone (Stress → Binge eating → BMI) was also significant (B = 0.056, Boot SE = 0.022, 95% CI [0.018, 0.102]; β = 0.071). The mediation path through emotional eating alone (Stress → Emotional eating → BMI) was not significant (B = -0.019, Boot SE = 0.023, 95% CI [-0.068, 0.025]; β = -0.024). These results indicate that perceived stress indirectly contributes to increased BMI via its effects on binge eating, both directly and through emotional eating.

Table 3.

Indirect effects of perceived stress on BMI via emotional and binge eating (Bootstrp = 10,000).

Table 3.

Indirect effects of perceived stress on BMI via emotional and binge eating (Bootstrp = 10,000).

| Indirect Path |

Effect (B) |

Boot SE |

Boot LL |

Boot UL |

| Perceived stress → Emotional eating → BMI |

-.019 |

.023 |

-.068 |

.025 |

| Perceived stress → Binge eating → BMI |

.056 |

.022 |

.018 |

.102 |

| Perceived stress → Emotional eating → Binge eating → BMI |

.071 |

.018 |

.041 |

.112 |

| Total Indirect Effect |

.108 |

.031 |

.052 |

.172 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings and Theoretical Implications

The present study offers the first empirical test of a serial mediation model linking perceived stress to BMI through a sequential pathway involving emotional eating and binge eating. The findings highlight two key patterns: (1) a significant serial mediation pathway (Perceived stress → Emotional eating → Binge eating → BMI) that supports the overeating continuum hypothesis; and (2) an additional direct pathway from stress through binge eating alone to BMI. Notably, emotional eating did not independently mediate BMI when controlling for binge eating, suggesting that its influence on weight may primarily operate through progression to more severe dysregulated eating behaviors. This pattern is consistent with theoretical models positing emotional eating as an earlier, less severe stage on a continuum of problematic eating behaviors escalating toward clinically significant binge eating episodes [

9,

18].

These findings provide important empirical support for Davis's overeating continuum model [

18], which conceptualizes eating behaviors along a spectrum of severity—from occasional overeating to compulsive binge eating. The significant serial mediation observed here indicates that emotional eating may serve as a developmental precursor to binge eating. This progression aligns with affect regulation models, where repeated use of food to manage negative emotions can lead to more severe loss-of-control episodes over time. The present results extend previous longitudinal findings by Stice et al. [

19], who demonstrated that emotional eating prospectively predicted binge eating onset, by providing direct statistical evidence within a mediation framework. Furthermore, our findings complement cross-sectional observations by Ricca et al. [

20], which demonstrate stepped increases in emotional eating scores from non-binge eaters to subthreshold and full BED groups, illustrating how this progression may contribute to weight-related outcomes.

These findings provide crucial empirical support for Davis's overeating continuum model [

18], which conceptualizes eating behaviors as existing along a severity spectrum from occasional overeating to compulsive binge eating. The significant serial mediation pathway observed here suggests that emotional eating may indeed serve as a developmental precursor to binge eating, as theoretically proposed. This progression is consistent with affect regulation models of eating pathology, where repeated use of food to manage negative emotions may lead to more severe loss-of-control episodes over time. The current results extend previous longitudinal findings by Stice et al. [

19], who demonstrated that emotional eating prospectively predicted binge eating onset, by providing direct statistical evidence for this sequential relationship within a mediation framework. Furthermore, our findings complement cross-sectional observations by Ricca et al. [

20] showing stepped increases in emotional eating scores across non-binge eaters, subthreshold BED, and full BED groups, by demonstrating how this progression may contribute to weight-related outcomes.

The identification of a significant direct mediation pathway from stress through binge eating to BMI, independent of the serial pathway, carries important theoretical and clinical implications. This finding indicates that binge eating may develop in response to stress via multiple mechanisms, not solely through the escalation of emotional eating. For example, some individuals might bypass a distinct emotional eating phase and develop binge eating directly in reaction to stress, potentially due to factors such as genetic predisposition, pre-existing impulse control difficulties, or exposure to particularly severe stressors [

15,

31,

32,

33]. This dual-pathway model aligns with Chao et al. [

14], who reported that although both emotional eating and binge eating were linked to stress, only binge eating demonstrated a significant association with adverse metabolic outcomes. The simultaneous existence of both serial and direct pathways underscores binge eating as a critical intervention target, as it functions as the final common pathway for stress-related weight gain, regardless of whether individuals progress through emotional eating or develop binge eating independently.

4.2. Clinical and Practical Implications

The serial mediation results offer key guidance for prevention and intervention. First, recognizing emotional eating as a precursor to binge eating reveals a critical window for early prevention.

The serial mediation findings have significant implications for prevention and intervention strategies. The identification of emotional eating as a precursor to binge eating [

19,

20,

22] suggests a critical window for early intervention (or prevention). Early interventions targeting emotion regulation skills, stress management, and adaptive coping strategies may prevent the escalation from emotional eating to binge eating [

34,

35]. Second, these results underscore the need to tailor weight management interventions to behavior severity. Individuals exhibiting binge eating may benefit from intensive, specialized treatments, whereas those with predominant emotional eating could respond well to lower-intensity programs. For those with established binge eating, interventions must target both emotional triggers and loss-of-control episodes. Integrating dialectical behavior therapy, mindfulness techniques, and cognitive-behavioral strategies can effectively address both emotion regulation deficits and binge eating behaviors [

36,

37,

38].

4.3. Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences about the ordering of stress, emotional eating, and binge eating pathways; multi-wave longitudinal data are needed to confirm causality. Second, the relatively small sample (N = 272) drawn from a single cultural context—predominantly young Korean adults—limits external validity to older, non-Korean, or clinical populations. Third, reliance on self-report questionnaires introduces potential response bias and measurement error; objective assessments (e.g., ecological momentary assessment, clinician-administered interviews) should be incorporated in future studies. Fourth, only one serial mediation model based on the overeating continuum framework was tested; alternative or parallel pathways (e.g., involving sleep disturbance, physical activity, or dietary quality) remain unexamined and warrant comparison using model-comparison approaches.

4.4. Future Directions

Future research should pursue the following directions:

Longitudinal, multi-wave designs are essential to establish temporal precedence and examine how stress-related changes in eating behaviors predict weight gain trajectories over time.

Expanding recruitment to larger, more diverse samples—including varied ages, ethnicities, and clinical populations with diagnosed BED—will enhance generalizability and clarify subgroup differences.

Incorporating objective measures such as laboratory-based stress and eating assessments, wearable monitoring of physical activity, and biological markers (e.g., cortisol) can mitigate self-report biases and provide mechanistic insights.

Testing of competing mediation models and potential moderators (e.g., personality traits, genetic polymorphisms, environmental stressors) should delineate alternative pathways and identify individual vulnerability factors.

Prospective or retrospective studies in clinical eating disorder cohorts can pinpoint transition points from emotional eating to BED, elucidate risk and protective factors, and inform targeted prevention and intervention strategies.

5. Conclusions

This study offers the first empirical support for a serial mediation model linking perceived stress to BMI via sequential pathways of emotional eating and binge eating. These results validate theoretical frameworks of an overeating continuum, where emotional eating precedes more severe binge episodes. Importantly, the presence of both serial and direct pathways underscores binge eating as a critical intervention target for obesity prevention and treatment. Clinically, emotional eating may serve as an early indicator of risk for escalating dysregulated eating and weight gain, warranting timely emotion-regulation interventions. Individuals with established binge eating may benefit from specialized, intensive treatments. Future studies should employ longitudinal, multi-wave designs, recruit larger and culturally diverse samples, and incorporate objective assessments to further elucidate and confirm the stress–eating–obesity nexus.

This study provides the first empirical evidence for a serial mediation model linking perceived stress to BMI through sequential pathways involving emotional eating and binge eating. The findings support theoretical models proposing that these eating behaviors exist on a severity continuum, with emotional eating representing an earlier stage that can progress to more severe binge eating patterns. The identification of both serial and direct pathways to binge eating highlights the clinical importance of this behavior as a key target for obesity prevention and treatment. From a practical standpoint, the findings suggest that emotional eating may serve as an early warning sign for individuals at risk of developing more severe eating problems and weight gain. Early identification and intervention targeting emotion regulation skills may prevent progression to binge eating, while individuals already experiencing binge eating may require more intensive, specialized interventions. Future studies should employ longitudinal, multi-wave designs, recruit larger and culturally diverse samples, and incorporate objective assessments to further clarify and confirm the stress–eating–obesity pathway.

Author Contributions

The author, K.B., contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, and writing—review and editing of the manuscript. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022R1A2C1093132), Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) under the Artificial Intelligence Convergence Innovation Human Resources Development (IITP-2023-RS-2023-00254177) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT), and Ministry of Education of South Korea (the BK21 Four program, Korean Southeast Center for the 4th Industrial Revolution Leader Education).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University (PNU IRB/2023_18_HR, approved on 10 February 2023; 2024_148_HR, approved on 23 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author on request.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Mr. Jake Jeong and Ms. Jungwon Jang for their technical support in the present study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BED |

Binge eating disorder |

| BES |

Binge Eating Scale |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| DEBQ |

Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaires |

| HPA |

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal |

| PSS |

Perceived Stress Scale |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

References

- Tomiyama, A.J. Stress and Obesity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sominsky, L.; Spencer, S.J. Eating Behavior and Stress: A Pathway to Obesity. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.J.; Campbell, I.C.; Troop, N. Increases in Weight during Chronic Stress Are Partially Associated with a Switch in Food Choice towards Increased Carbohydrate and Saturated Fat Intake. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2014, 22, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.M.; Jastreboff, A.M.; White, M.A.; Grilo, C.M.; Sinha, R. Stress, Cortisol, and Other Appetite-Related Hormones: Prospective Prediction of 6-Month Changes in Food Cravings and Weight. Obesity 2017, 25, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.; Conner, M.; Clancy, F.; Moss, R.; Wilding, S.; Bristow, M.; O’Connor, D.B. Stress and Eating Behaviours in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2022, 16, 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razzoli, M.; Pearson, C.; Crow, S.; Bartolomucci, A. Stress, Overeating, and Obesity: Insights from Human Studies and Preclinical Models. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 76, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Strien, T.; Konttinen, H.; Homberg, J.R.; Engels, R.C.M.E.; Winkens, L.H.H. Emotional Eating as a Mediator between Depression and Weight Gain. Appetite 2016, 100, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakanalis, A.; Mentzelou, M.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Papandreou, D.; Spanoudaki, M.; Vasios, G.K.; Pavlidou, E.; Mantzorou, M.; Giaginis, C. The Association of Emotional Eating with Overweight/Obesity, Depression, Anxiety/Stress, and Dietary Patterns: A Review of the Current Clinical Evidence. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arexis, M.; Feron, G.; Brindisi, M-C. ; Billot, P-É.; Chambaron, S. A Scoping Review of Emotion Regulation and Inhibition in Emotional Eating and Binge-Eating Disorder: What about a Continuum? J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, E.W.; Kelly, N.R. Stress-Related Eating, Mindfulness, and Obesity. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, C.; Adjepong, M.; Chong Hueh Zan, M.; Cho, M.J.; Fenton, J.I.; Hsiao, P.Y.; Keaver, L.; Lee, H.; Ludy, M-J. ; Shen, W. Gender Differences in the Relationships between Perceived Stress, Eating Behaviors, Sleep, Dietary Risk, and Body Mass Index. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayne, J.M.; Ayala, R.; Karl, J.P.; Deschamps, B.A.; McGraw, S.M.; O’Connor, K.; DiChiara, A.J.; Cole, R.E. Body Weight Status, Perceived Stress, and Emotional Eating among US Army Soldiers: A Mediator Model. Eat. Behav. 2020, 36, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, B.M.; Spruijt-Metz, D.; Naya, C.H.; Lane, C.J.; Wen, C.K.F.; Davis, J.N.; Weigensberg, M.J. The Mediating Role of Emotional Eating in the Relationship between Perceived Stress and Dietary Intake Quality in Hispanic/Latino Adolescents. Eat. Behav. 2021, 42, 101537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.; Grey, M.; Whittemore, R.; Reuning-Scherer, J.; Grilo, C.M.; Sinha, R. Examining the Mediating Roles of Binge Eating and Emotional Eating in the Relationships between Stress and Metabolic Abnormalities. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 39, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronce, J.M.; Bedard-Gilligan, M.A.; Zimmerman, L.; Hodge, K.A.; Kaysen, D. Alcohol and Binge Eating as Mediators between Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Severity and Body Mass Index. Obesity 2017, 25, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruccoli, J.; Mack, I.; Klos, B.; Schild, S.; Stengel, A.; Zipfel, S.; Giel, K.E.; Schag, K. Mental Health Variables Impact Weight Loss, Especially in Patients with Obesity and Binge Eating: A Mediation Model on the Role of Eating Disorder Pathology. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gu, J.; Li, Y.; Xia, B.; Meng, X. The Effect of Perceived Stress on Binge Eating Behavior among Chinese University Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1351116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C. From Passive Overeating to “Food Addiction”: A Spectrum of Compulsion and Severity. ISRN Psychiatry 2013, 2013, 435027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stice, E.; Presnell, K.; Spangler, D. Risk Factors for Binge Eating Onset in Adolescent Girls: A 2-Year Prospective Investigation. Health Psychol. 2002, 21, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricca, V.; Castellini, G.; Lo Sauro, C.; Ravaldi, C.; Lapi, F.; Mannucci, E.; Rotella, C.M.; Faravelli, C. Correlations between Binge Eating and Emotional Eating in a Sample of Overweight Subjects. Appetite 2009, 53, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haedt-Matt, A.A.; Keel, P.K.; Racine, S.E.; Burt, S.A.; Hu, J.Y.; Boker, S.; Neale, M.; Klump, K.L. Do Emotional Eating Urges Regulate Affect? Concurrent and Prospective Associations and Implications for Risk Models of Binge Eating. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 874–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverri-Alvarado, B.; Pickett, S.; Gildner, D. A Model of Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms on Binge Eating through Emotion Regulation Difficulties and Emotional Eating. Appetite 2020, 150, 104659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haam, J-H. ; Kim, B.T.; Kim, E.M.; Kwon, H.; Kang, J-H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, K-K.; Rhee, S.Y.; Kim, Y-H.; Lee, K.Y. Diagnosis of Obesity: 2022 Update of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 32, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Shin, C.; Ko, Y-H. ; Lim, J.; Joe, S-H.; Kim, S.; Jung, I-K.; Han, C. Reliability and Validity Studies of the Korean Version of the Perceived Stress Scale. Korean J. Psychosom. Med. 2012, 20, 127–134. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- van Strien, T.; Frijters, J.E.R.; Bergers, G.P.A.; Defares, P.B. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for Assessment of Restrained, Emotional, and External Eating Behavior. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H-J. ; Lee, I-S.; Kim, J-H. A Study of the Reliability and Validity of the Korean Version of the Eating Behavior Questionnaire. Korean J. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 15, 141–150. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Gormally, J.; Black, S.; Daston, S.; Rardin, D. The Assessment of Binge Eating Severity among Obese Persons. Addict. Behav. 1982, 7, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Hyun, M.H. The Effects of Obesity, Body Image Satisfaction, and Binge Eating on Depression in Middle School Girls. Korean J. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 195–207. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, C. The Epidemiology and Genetics of Binge Eating Disorder (BED). CNS Spectr. 2015, 20, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leehr, E.J.; Schag, K.; Brückmann, C.; Plewnia, C.; Zipfel, S.; Nieratschker, V.; Giel, K.E. A Putative Association of COMT Val108/158Met with Impulsivity in Binge Eating Disorder. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2016, 24, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appolinario, J.C.; de Moraes, C.E.F.; Sichieri, R.; Hay, P.; Faraone, S.V.; Mattos, P. Associations of Adult ADHD Symptoms with Binge-Eating Spectrum Conditions, Psychiatric and Somatic Comorbidity, and Healthcare Utilization. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2024, 46, e20243728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juarascio, A.S.; Parker, M.N.; Manasse, S.M.; Barney, J.L.; Wyckoff, E.P.; Dochat, C. An Exploratory Component Analysis of Emotion Regulation Strategies for Improving Emotion Regulation and Emotional Eating. Appetite 2020, 150, 104634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morillo-Sarto, H.; López-del-Hoyo, Y.; Pérez-Aranda, A.; Modrego-Alarcón, M.; Barceló-Soler, A.; Borao, L.; Puebla-Guedea, M.; Demarzo, M.; García-Campayo, J.; Montero-Marin, J. ‘Mindful Eating’ for Reducing Emotional Eating in Patients with Overweight or Obesity in Primary Care Settings: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2023, 31, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berking, M.; Eichler, E.; Naumann, E.; Svaldi, J. The Efficacy of a Transdiagnostic Emotion Regulation Skills Training in the Treatment of Binge-Eating Disorder—Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 61, 998–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zompa, L.; Cassioli, E.; Rossi, E.; Cordasco, V.Z.; Caiati, L.; Lucarelli, S.; Giunti, I.; Lazzeretti, L.; D’Anna, G.; Dei, S. Group Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder: Emotion Dysregulation and Alexithymia as Mediators of Symptom Improvement. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Luz:, F.Q.; Hay, P.; Wisniewski, L.; Cordás, T.; Sainsbury, A. The Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder with Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Other Therapies: An Overview and Clinical Considerations. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).