1. Introduction

Cerebral small vessel disease (cSVD) is increasingly recognized as a major contributor to ischemic stroke, spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), and neurodegenerative disorders in older adults.[

1] cSVD cases most ICH particularly in elderly and spontaneous, non-traumatic primary ICH related to cSVD presents a catastrophic form of stroke associated with high mortality, significant morbidity, and high risk of recurrence.[

2,

3]

cSVD is associated with vascular dementia, gait disturbance, behavioral disorders, and functional disabilities[

1] and it also shares conventional vascular risk factors including age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking.[

4,

5] Despite its high prevalence and clinical significance, cSVD is often considered a “clinically silent” condition until it manifests through severe cerebrovascular events such as ischemic or hemorrhagic strokes.[

2] However, presence of cSVD has enormous implications for stroke prevention, acute management, post-stroke recovery, recurrence, and overall socioeconomic burden. Previous studies revealed that ICH is caused by SVD in a 85% of cases[

4,

6] and also can lead to poor prognosis.[

7] Notably, cSVD has profound implications across all stages of ICH.

Pathologically, cSVD encompasses all the pathological conditions affecting the cerebral microcirculatory vasculature, including small arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules, and small vein.[

8] It primarily involves the deep white and grey matter areas of the brain,[

9,

10] where perforating vessels play a critical role in supporting the brain’s most metabolically active nuclei and complex neural networks.[

11] Importantly, “small vessel disease” (SVD) is not limited to the brain; it can also involve any microvascular structures in the human body, such as the retina, heart, lung, and kidneys, reflecting a systemic vascular condition.[

12] Thus, the presence of SVD in any organ implies that the patient is already suffering from a “systemic” condition.[

12] Therefore, cSVD implies a systemic disease.

Throughout these findings, although “clinically silent” until hemorrhagic stroke has developed, the presence of cSVD has profound implications across all the stages of ICH.

Furthermore, as a manifestation of “systemic” small vessel pathology, cSVD reflects a broader vascular vulnerability that may influence stroke outcomes beyond the acute phase.

While the association between cSVD and ICH has been well-documented in prior studies, [

13,

14] most research has focused on the neuroimaging findings, as well as the risk of hematoma expansion and recurrence.[

4,

7,

15,

16] Unfortunately, functional assessment in previous studies were largely limited to the modified Rankin scale (mRS).[

13,

17] As is well recognized, functional recovery encompasses a broad spectrum, including gait, swallowing, cognition, and activities of daily living. Despite its clinical importance, the specific impact of cSVD on functional recovery after ICH remains poorly understood. In particular, the interaction between cSVD and aging, which may critically shape recovery trajectories, has not been thoroughly investigated.

This study aimed to investigate the impact of cSVD on functional improvement after ICH through a comprehensive assessment of multiple functional domains. Since both ICH and cSVD are significantly influenced by age,[

1,

3,

8] patients were stratified into two subgroups (<65 and ≥65 years) to minimize confounding effects.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was designed as a retrospective chart review. Consecutive patients with spontaneous ICH admitted at our medical university hospital between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2024, were screened for this study. Patients with traumatic ICH or hemorrhagic transformation of a cerebral infarction were excluded. Patients with a history of previous stroke that could affect functional decline were also excluded. In addition, patients with unavailable or unreliable CT scans, bilateral or multiple ICH sites (due to ICH classification), and those who died within 7 days after ICH onset were excluded.

Patients underwent MRI studies to rule out secondary causes of ICH, including arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), tumor, and other structural abnormalities. After initial management by the neurosurgical team—either surgical or conservative—rehabilitation therapy was initiated when patients became neurologically stable, typically within 2 weeks of ICH onset. Individualized rehabilitation included physical and occupational therapy, with additional dysphagia, cognitive, or speech therapy as needed.

2.1. Neuroimaging Classification of ICH and cSVD

CSVD was identified based on characteristic neuroimaging findings on CT or MRI, including lacunes and white matter changes, as assessed by an experienced neuroradiologist. The diagnosis incorporated both clinical and imaging data. cSVD subtypes were classified according to the STRIVE criteria and previous literature,[

2] including recent small subcortical infarct, lacune, white matter hyperintensity, perivascular spaces, cerebral microbleeds, and brain atrophy.

The etiology of ICH was classified based on neuroimaging and clinical data, categorized as hypertension-related ICH, cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), arteriovenous malformation (AVM), moyamoya disease (MMD), tumor-related hemorrhage, and ICH of unknown cause.[

18] The location of ICH was categorized as basal ganglia, thalamus, cerebral lobe, pons and brainstem, or cerebellum following previous studies.[

18,

19]

Neuroimaging was assessed to classify ICH etiology and location, as well as to confirm the presence of SVD. Subsequently, ICH and SVD scores were calculated using standardized criteria. ICH score[

20] is a validated prognostic grading scale (0–6 points) that incorporates GCS, hemorrhage volume, intraventricular extension, infratentorial origin, and age ≥ 80 years to predict 30-day mortality in spontaneous ICH patients. The SVD score (0-4)[

21] was assigned by summing the presence of lacunes, microbleeds, white matter hyperintensities (WMHs), and enlarged perivascular spaces on MRI. Patients without MRI were excluded from SVD score analysis.

2.2. Functional Evaluation

Functional evaluations were conducted at the start of rehabilitation (within 2weeks after ICH onset) and at 3 months after rehabilitation. The assessments included global disability (modified Rankin Scale, mRS), activities of daily living (Modified Barthel Index, MBI), balance and gait (Berg Balance Scale, BBS), gait function (Functional Ambulation Category, FAC), upper extremity function (Manual Function Test, MFT), and swallowing function.

The mRS is a 7-point scale measuring global disability after stroke, from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death)[

22] with scores of 0–2 indicating good outcomes. The Modified Barthel Index (MBI

) is a widely used scale for assessing independence in activities of daily living (ADL), such as feeding, bathing, bowel and bladder control, gait, and stair climbing et al. Higher scores indicating greater independence.[

23] The BBS is a 14-item objective measure that assesses static and dynamic balance abilities, with higher scores reflecting better balance function.[

24] The FAC categorizes walking ability into six levels based on required assistance.[

25] The MFT evaluates upper limb motor function through tasks such as grasping, pinching, and object manipulation, commonly used in stroke.[

26] Higher FAC and MFT scores also indicate better function. Swallowing function was assessed using the videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS), the gold standard for evaluating dysphagia.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Patients were stratified by age and cSVD status.Within each subgroup, categorical variables were compared between patients with and without SVD using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, while continuous variables were compared using the student’s t-test. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed using different dependent variables (e.g., poor prognosis or SVD status) to explore various associations with potential predictors.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Ethics Committee of our hospital (DC25RISI0033). Informed consents were waived due to a retrospective study design and minimal harm to the patients.

3. Results

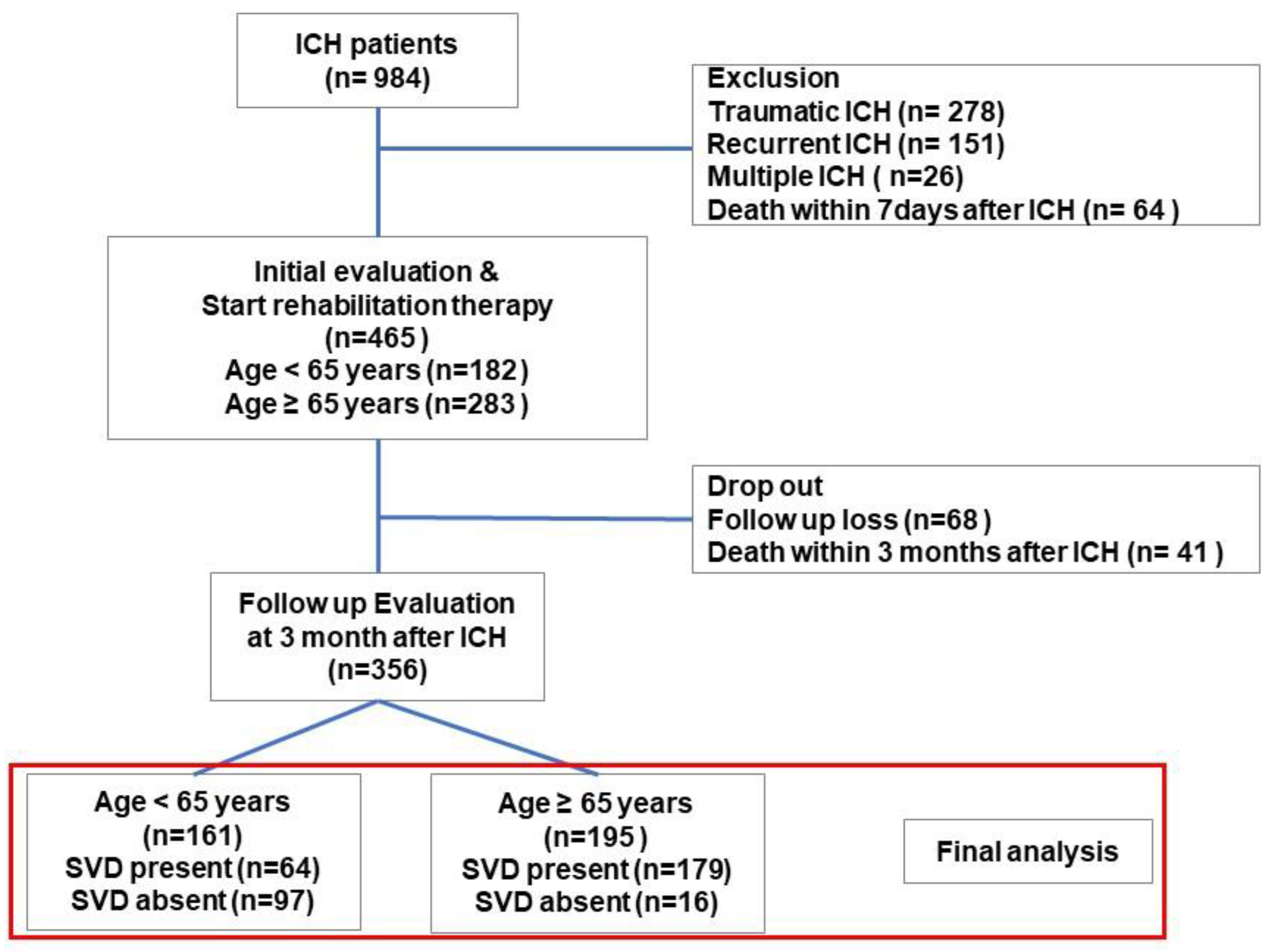

A total of 984 patients were admitted with ICH between 2020 and 2024. After excluding cases of traumatic, recurrent, or multiple ICH and early mortality, 465 patients with spontaneous ICH were identified. Of these, 356 patients who underwent both initial and 3-month post-ICH functional evaluations were included in the final analysis. This cohort study consisted of 161 patients aged under 65 years and 195 patients aged 65 years or older (

Figure 1).

Table 1 presents the demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of patients with ICH stratified by age group and the presence of cSVD. Among patients aged under 65 years, those with cSVD were significantly older and were more likely to be male and had higher rates of hypertension and diabetes mellitus compared to those without cSVD. The prevalence of chronic kidney disease and smoking was also significantly higher in the cSVD group (all p < 0.05).

In patients aged 65 years or older, those with cSVD were significantly older and had a higher prevalence of hypertension and chronic kidney disease compared to those without cSVD. Across all age groups, the presence of cSVD was significantly associated with higher ICH scores and poorer functional outcomes at 3 months after ICH (all p < 0.05).

Neuroimaging characteristics revealed that hypertension-related ICH was more prevalent among younger patients with cSVD, whereas CAA was significantly more common in older patient with cSVD (

Table 2). In addition, Moyamoya disease was significantly more prevalent in patients with cSVD across both age groups. In terms of ICH location, thalamic involvement was significantly more common among younger patients with cSVD. Notably, 82.57% of ICH cases in this group were located in subcortical or deep brain regions.

Regarding neuroimaging markers of cSVD, WMHs and cerebral microbleeds were the most frequently observed in patients under 65 years (76.6% and 51.6%, respectively), whereas WMHs and lacunes were predominant in those aged 65 years or older (84.9% and 50.8%, respectively). The total SVD score was higher in the older cSVD group compared to the younger cSVD group (2.18±0.90 vs. 1.73±0.67).

Table 3 summarizes the between-group comparisons of functional evaluations at initial and 3-month follow-up, stratified by age and cSVD status. Among patients aged under 65 years, those with cSVD had significantly higher initial mRS scores and lower initial MBI, BBS, and MFT scores compared to those without cSVD. At 3 months after ICH, patients with cSVD continued to demonstrate poorer functional outcomes, with significantly higher mRS scores and lower MBI and hand function scores (all P<0.05). Swallowing function also showed a significant difference at 3 months: while 91.8% of patients without cSVD resumed a normal diet, only 70.3% of those with cSVD did so, with a higher proportion remaining on limited or non-oral diets (p = 0.002).

Similarly, in patients aged 65 years or older, the cSVD group had significantly higher initial mRS scores and lower MBI and BBS scores. At 3 months after ICH, functional recovery in the cSVD group remained significantly poorer across all domains, with higher mRS scores and lower MBI, BBS, FAC, and MFT scores (all p < 0.05). Swallowing function was also notably impaired in this older group: at 3 months, 54.8% of patients with cSVD remained on non-oral feeding, whereas none of the patients without cSVD remained on non-oral feeding (p = 0.021). Only 17.3% of those with cSVD were able to resume a normal diet, indicating that cSVD was associated with markedly delayed recovery of swallowing function.

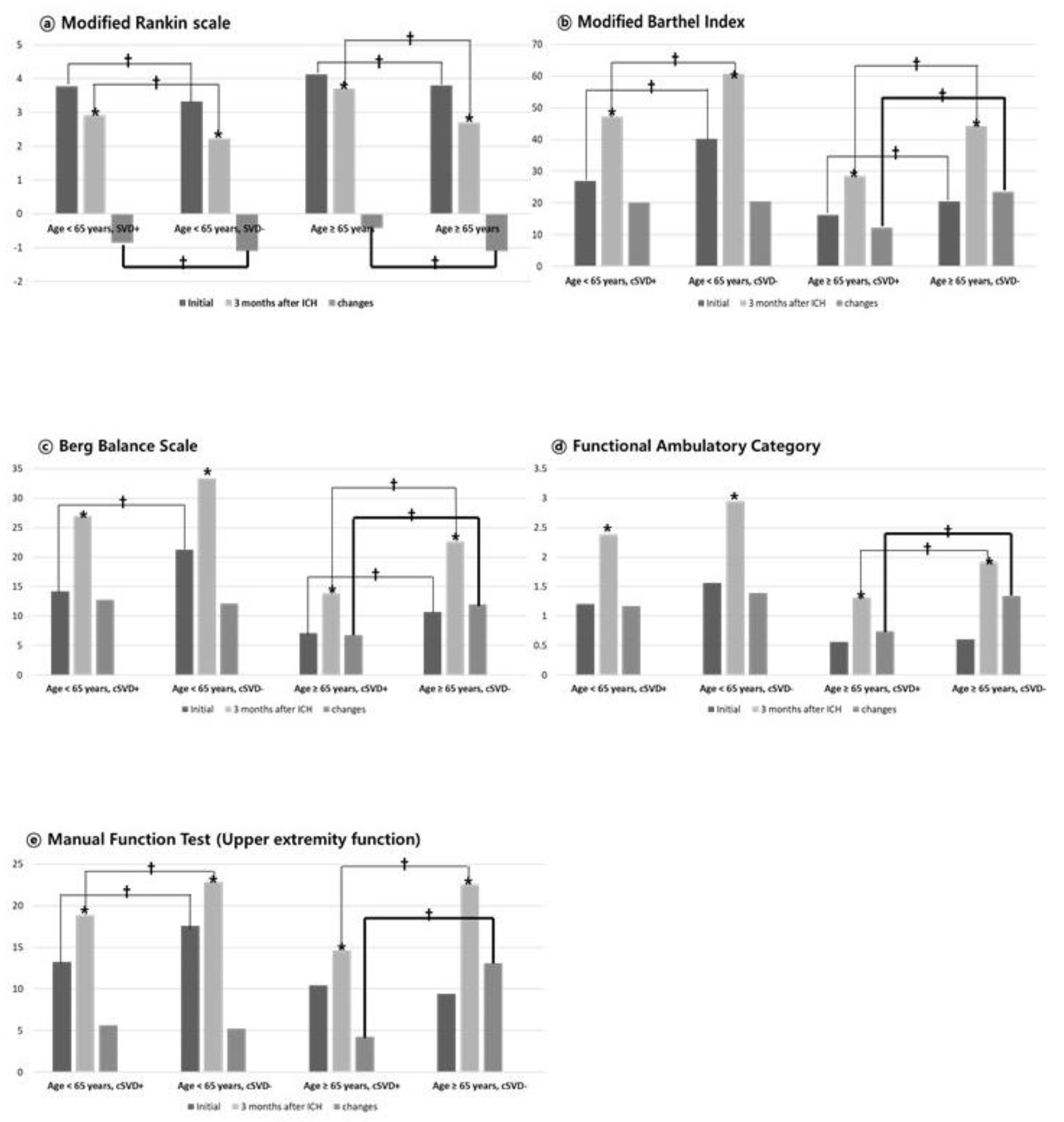

Figure 2 illustrates functional evaluations for each domain at initial assessment, 3-month follow-up, and the degree of functional improvement (change = 3-month score – initial score), according to age group (<65 years and ≥65 years) and cSVD status. In the within-group analysis, all groups - including those aged under and over 65years, and both cSVD and non-cSVD groups - achieved significant functional improvement between initial and 3-month evaluations across all functional domains (all p<0.05; indicated as “*” in

Figure 2). As also shown in

Table 3, functional status at both initial and 3-month evaluations was consistently and significantly better in the non-cSVD group compared to the cSVD group across both age groups.

However, when comparing the degree of functional improvement (“changes” in

Figure 2) between initial and 3-month evaluations, significant between-group differences were observed only in patients aged ≥65 years, with those without cSVD demonstrating significantly greater improvement across all functional domains (bold line in

Figure 2, all p < 0.05). In contrast, among patients aged under 65 years, the degree of improvement was similar between groups regardless of cSVD status, and no significant differences were observed in any functional domains except for the mRS (

Figure 2).

Table 4 demonstrates the results of multivariable logistic regression analysis for predictors of poor prognosis (defined as mRS 3–5 at 3 months after ICH), stratified by age group. In patients aged <65 years, the presence of cSVD was significantly associated with poor prognosis (OR = 3.82, 95% CI: 1.23–8.76, p = 0.004), as was a higher ICH score (OR = 3.95, 95% CI: 2.51–6.21, p < 0.001). Additionally, the presence of CKD (OR = 5.21, 95% CI: 1.35–7.61, p < 0.001), hypertension (OR = 2.95, 95% CI: 1.09–8.61, p = 0.034), and diabetes (OR = 3.16, 95% CI: 2.47–8.92, p < 0.001) were also significantly associated with poor outcomes. In contrast, age and heart failure were not significant predictors in this age group.

In patients aged ≥65 years, cSVD remained a strong independent predictor of poor prognosis (OR = 7.44, 95% CI: 2.40–15.35, p < 0.001), along with a higher ICH score (OR = 3.29, 95% CI: 2.36–4.89, p < 0.001). The presence of CKD (OR = 6.48, 95% CI: 0.43–0.95, p = 0.030) and hypertension (OR = 2.17, 95% CI: 1.74–11.49, p < 0.001) were also significantly associated with poor outcomes. However, age, diabetes, and heart failure were not significantly associated with prognosis in this older population.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the impact of cSVD on functional recovery after ICH by comprehensively evaluating multiple functional domains, including global disability (mRS), activities of daily living, gait, upper extremity function and swallowing. To minimize the confounding effect of age, patients were stratified into two subgroups: those aged <65 years and those aged ≥65 years.

In our large cohort of primary spontaneous ICH patients, those without cSVD consistently exhibited better functional status than those with cSVD at both initial and 3-month evaluations across both age groups. Notably, although all groups—regardless of age or cSVD status—achieved statistically significant functional improvement over time, the degree of improvement was significantly lower in patients with cSVD, particularly among those aged 65 years or older. These findings suggest that cSVD has a more pronounced negative impact on post-stroke recovery in older patients

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (

Table 4) further confirmed that the presence of cSVD was a strong and significant independent predictor of poor functional outcomes at 3 months after ICH even after adjusting for other variables such as ICH score, age, and comorbidities. This association was stronger in the older population, indicating that cSVD may play a critical role in determining long-term outcomes in elderly ICH survivors.

4.1. Distinct Contributions Compared to Previous Studies

Previous studies have identified cSVD as a key etiological factor for ICH, particularly in elderly patients, and is associated with poor clinical outcomes.[

5,

13,

15,

27,

28] Uniken et al.[

13] reported that cSVD significantly worsened functional outcomes after ICH, even after adjusting for hematoma volume and location. Similarly, Cheng et al.[

14] found that cSVD markers—such as white matter hyperintensities and lacunes—were significantly associated with reduced functional recovery. Sakamoto et al.[

29] also noted that higher cSVD burden and older age were independently associated with deep ICH locations, suggesting a shared microangiopathic mechanisms.

Our findings align with prior studies demonstrating the detrimental impact of cSVD on ICH and further offer several distinct contributions. First, we stratified patients by age, revealing that the detrimental impact of cSVD is evident even in younger adults, though more pronounced in the elderly. Second, unlike many studies that relied solely on the mRS as a functional outcome measure,[

7,

13,

14,

15,

29,

30] our study comprehensively assessed multiple functional domains—including daily activities, balance and gait, upper extremity function, and swallowing—using validated tools such as the MBI, BBS, FAC, MFT, and VFSS. This multidimensional approach offers a more comprehensive understanding of the functional burden of cSVD following ICH.

Our methodological strengths highlight the independent role of cSVD in limiting recovery after ICH and support the need for age-specific rehabilitation strategies.

4.2. Age-Dependent Impact of cSVD on Functional Recovery After ICH

Notably, our findings highlight the age-dependent influence of cSVD on functional recovery following ICH. While cSVD was associated with poorer functional status at both baseline and 3-month evaluations across all age groups, its impact was particularly pronounced in patients aged ≥65 years. Among younger patients, cSVD had a limited effect on the degree of functional improvement (

Figure 2). In contrast, older patients with cSVD exhibited significantly attenuated recovery across multiple functional domains indicating that cSVD imposes a broader and more detrimental effect in this age group.

This age-specific vulnerability may reflect a reduced neuroplasticity and diminished brain resilience with aging, amplifying the adverse effects of cSVD pathology.

Previous studies have established cSVD as a major contributor to spontaneous ICH in older adults and a strong predictor of cognitive and functional decline.[

1,

4,

6] It also shares conventional vascular risk factors, including age, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking.[

4,

5] cSVD becomes increasingly prevalent with age, affecting most individuals over 60 and nearly all those over 90.[

31] However, the interaction between age and the functional impact of cSVD has not been clearly delineated. Our study directly addressed this gap by stratifying patients by age and employing multidomain functional assessment. Multivariable logistic regression confirmed that cSVD was a strong and independent predictor of poor outcomes in older ICH survivors.

The negative impact of cSVD on recovery is amplified in the elderly, likely due to the cumulative burden of microvascular injury and concurrent age-related neurodegenerative processes.[

12,

25] Pathophysiological mechanisms implicated in aging-related cSVD include endothelial dysfunction, blood–brain barrier breakdown, chronic low-grade inflammation ("inflammaging"), and reduced cerebral perfusion—all of which contribute to impaired neuroplasticity and delayed recovery.[

28,

32,

33]

Taken together, these findings provide robust evidence that the aging brain is particularly vulnerable to the combined effects of small vessel pathology and hemorrhagic insult. Our results underscore the importance of considering both age and cSVD status when evaluating prognosis and designing individualized rehabilitation strategies for ICH patients.

4.3. Functional Impact of cSVD in Younger Adults

While the detrimental effect of cSVD on functional recovery has been predominantly observed in older adults, our study demonstrates that cSVD also adversely affects recovery in younger patients (<65 years). Despite generally higher recovery potential in younger ICH individuals[

34], those with cSVD exhibited significantly poorer functional status at both the initial and 3-month evaluations compared to those without cSVD (

Table 3 &

Figure 2). Although between-group differences in the degree of functional improvement were less marked in the younger cohort, the persistently lower scores in the cSVD group indicate a sustained functional disadvantage attributable to microvascular pathology even in younger brains. These findings are consistent with prior studies[

35,

36], which reported that cSVD is not uncommon in young adults with ICH and may impair recovery regardless of age. Consistent with previous studies,[

35,

36] our study found that cerebral microbleeds and white matter changes were the most frequently observed cSVD markers in younger ICH patients. This underscores the clinical relevance of detecting and monitoring cSVD in younger ICH patients, as early recognition could inform risk stratification and personalized rehabilitation planning, even in populations traditionally considered to have favorable prognoses.

As shown in

Table 1, younger patients with cSVD had significantly higher rates of conventional vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and smoking history compared to those without cSVD. As previously mentioned, SVD is increasingly recognized as a “systemic disease”, and cSVD shares many of the same vascular risk factors. These findings suggest that even in younger patients, the presence of cSVD may reflect a broader systemic vascular burden. Accordingly, early identification and aggressive management of underlying comorbidities may be essential to improving outcomes in this population.

4.4. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective and single-center design may introduce selection bias and limit generalizability. Second, the relatively small number of patients in certain subgroups—particularly elderly individuals without cSVD—may have reduced statistical power for subgroup analyses. Third, cognitive function and aphasia were not assessed due to limited data availability and evaluation constraints in retrospective settings. Future large-scale, prospective studies are needed to better clarify the impact of cSVD on premorbid status, ICH risk, and long-term rehabilitation outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of cSVD on functional recovery after ICH through a multidimensional assessment of functional domains and an age-stratified analysis. Our findings demonstrated that cSVD significantly influenced both the initial neurological severity and the degree of functional improvement after ICH—particularly in elderly patients. These results suggest that cSVD is not merely a passive comorbidity, but an active and independent determinant of poor prognosis and limited recovery.

Given that cSVD often remains clinically silent prior to stroke onset, routine screening – especially in the elderly- may facilitate risk stratification and inform post-ICH management strategies. Overall, our findings highlight the clinical importance of early detection of cSVD and support the need for more intensive, individualized rehabilitation approaches in ICH survivors. We hope that our findings may help inform future research directions exploring the role of cSVD in ICH recovery and outcomes.

Author Contributions

Hong Jae Lee: Study design, Manuscript preparation, Haney Kim: Literature search, Data collection, Sook Joung Lee: Study design, Analysis of data, Review of manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a Chung Hie Oh & Jin-Sang Chung research grant of Korean Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine for 2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Catholic University of Korea, Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital (IRB No: DC25RISI0033).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to retrospective study design and minimal harm to the patients.

Data Availability Statement

Data of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Non-financial competing interest. There are no financial competing interests to declare in relation to this manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

ADL: activities of daily living

BBS: Berg balance scale

cSVD: cerebral small vessel disease

FAC: functional ambulatory category,

MBI: modified Barthel index

MFT: manual function test

mRS: modified Rankin scale

ICH: intracerebral hemorrhage

WMHs: white matter hyperintensities

References

- Wardlaw, J.M.; Smith, C.; Dichgans, M. Small vessel disease: mechanisms and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol 2019, 18, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardlaw, J.M.; Smith, E.E.; Biessels, G.J.; Cordonnier, C.; Fazekas, F.; Frayne, R.; Lindley, R.I.; O'Brien, J.T.; Barkhof, F.; Benavente, O.R.; et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol 2013, 12, 822–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, S.M.; Ziai, W.C.; Cordonnier, C.; Dowlatshahi, D.; Francis, B.; Goldstein, J.N.; Hemphill, J.C., 3rd; Johnson, R.; Keigher, K.M.; Mack, W.J.; et al. 2022 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2022, 53, e282–e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duering, M.; Biessels, G.J.; Brodtmann, A.; Chen, C.; Cordonnier, C.; de Leeuw, F.E.; Debette, S.; Frayne, R.; Jouvent, E.; Rost, N.S.; et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease-advances since 2013. Lancet Neurol 2023, 22, 602–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Shan, Y.; Cai, W.; Liu, S.; Hu, M.; Liao, S.; Huang, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; et al. Cerebral small vessel disease: neuroimaging markers and clinical implication. J Neurol 2019, 266, 2347–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charidimou, A.; Boulouis, G.; Frosch, M.P.; Baron, J.C.; Pasi, M.; Albucher, J.F.; Banerjee, G.; Barbato, C.; Bonneville, F.; Brandner, S.; et al. The Boston criteria version 2.0 for cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a multicentre, retrospective, MRI-neuropathology diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Neurol 2022, 21, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Zong, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, K.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, B.; Xu, Y. Clinical features and associated factors of coexisting intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with cerebral small vessel disease: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 5596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantoni, L. Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol 2010, 9, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardlaw, J.M.; Smith, C.; Dichgans, M. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: insights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol 2013, 12, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurol, M.E.; Biessels, G.J.; Polimeni, J.R. Advanced Neuroimaging to Unravel Mechanisms of Cerebral Small Vessel Diseases. Stroke 2020, 51, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullmore, E.; Sporns, O. The economy of brain network organization. Nat Rev Neurosci 2012, 13, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, A.M. Small Vessel Disease. Front Neurol 2019, 10, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniken Venema, S.M.; Marini, S.; Lena, U.K.; Morotti, A.; Jessel, M.; Moomaw, C.J.; Kourkoulis, C.; Testai, F.D.; Kittner, S.J.; Brouwers, H.B.; et al. Impact of Cerebral Small Vessel Disease on Functional Recovery After Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke 2019, 50, 2722–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhan, Z.; Xia, L.; Han, Z. Cerebral small vessel disease and prognosis in intracerebral haemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Neurol 2022, 29, 2511–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, J.G.; Jesuthasan, A.; Werring, D.J. Cerebral small vessel disease and intracranial bleeding risk: Prognostic and practical significance. Int J Stroke 2023, 18, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.S.; de Leeuw, F.E. Cerebral small vessel disease: Recent advances and future directions. Int J Stroke 2023, 18, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliteur, M.P.; Sondag, L.; Wolsink, A.; Rasing, I.; Meijer, F.J.A.; Jolink, W.M.T.; Wermer, M.J.H.; Klijn, C.J.M.; Schreuder, F. Cerebral small vessel disease and perihematomal edema formation in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 949133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, J.C., 3rd; Greenberg, S.M.; Anderson, C.S.; Becker, K.; Bendok, B.R.; Cushman, M.; Fung, G.L.; Goldstein, J.N.; Macdonald, R.L.; Mitchell, P.H.; et al. Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2015, 46, 2032–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, A.I.; Tuhrim, S.; Broderick, J.P.; Batjer, H.H.; Hondo, H.; Hanley, D.F. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 2001, 344, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemphill, J.C., 3rd; Bonovich, D.C.; Besmertis, L.; Manley, G.T.; Johnston, S.C. The ICH score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2001, 32, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staals, J.; Makin, S.D.; Doubal, F.N.; Dennis, M.S.; Wardlaw, J.M. Stroke subtype, vascular risk factors, and total MRI brain small-vessel disease burden. Neurology 2014, 83, 1228–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcommon, N.J.; Green, T.L.; Haley, E.; Cooke, T.; Hill, M.D. Improving the assessment of outcomes in stroke: use of a structured interview to assign grades on the modified Rankin Scale. Stroke 2003, 34, 377–378, author reply 377-378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, F.I.; Barthel, D.W. FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION: THE BARTHEL INDEX. Md State Med J 1965, 14, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, K.O.; Wood-Dauphinee, S.L.; Williams, J.I.; Maki, B. Measuring balance in the elderly: validation of an instrument. Can J Public Health 1992, 83 Suppl 2, S7–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holden, M.K.; Gill, K.M.; Magliozzi, M.R.; Nathan, J.; Piehl-Baker, L. Clinical gait assessment in the neurologically impaired. Reliability and meaningfulness. Phys Ther 1984, 64, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo WK, P.S. , Kim JS, Ko MH. Manual Function Test for the evaluation of upper limb motor function in hemiplegic patients. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 1996, 20, 597–605. [Google Scholar]

- Vikner, T.; Karalija, N.; Eklund, A.; Malm, J.; Lundquist, A.; Gallewicz, N.; Dahlin, M.; Lindenberger, U.; Riklund, K.; Bäckman, L.; et al. 5-Year Associations among Cerebral Arterial Pulsatility, Perivascular Space Dilation, and White Matter Lesions. Ann Neurol 2022, 92, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, M.; Malherbe, C.; Cheng, B.; Thomalla, G.; Schlemm, E. Functional connectivity changes in cerebral small vessel disease - a systematic review of the resting-state MRI literature. BMC Med 2021, 19, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, Y.; Sato, T.; Nito, C.; Nishiyama, Y.; Suda, S.; Matsumoto, N.; Aoki, J.; Saito, T.; Suzuki, K.; Katano, T.; et al. The Effect of Aging and Small-Vessel Disease Burden on Hematoma Location in Patients with Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis 2021, 50, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniken Venema, S.M.; Marini, S.; Brouwers, H.B.; Morotti, A.; Woo, D.; Anderson, C.D.; Rosand, J. Associations of Radiographic Cerebral Small Vessel Disease with Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage Volume, Hematoma Expansion, and Intraventricular Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2020, 32, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannistraro, R.J.; Badi, M.; Eidelman, B.H.; Dickson, D.W.; Middlebrooks, E.H.; Meschia, J.F. CNS small vessel disease: A clinical review. Neurology 2019, 92, 1146–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupré, N.; Drieu, A.; Joutel, A. Pathophysiology of cerebral small vessel disease: a journey through recent discoveries. J Clin Invest 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, D.; Lin, J.; Thomas, A.M.; Miao, J.; Chen, D.; Li, S.; Chu, C. Cerebral small vessel disease: Pathological mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 961661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, N.; Bonsack, F.; Sukumari-Ramesh, S. Intracerebral Hemorrhage: The Effects of Aging on Brain Injury. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 859067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.S.; Park, Y.S. Contributing factors of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage development in young adults. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg 2024, 26, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Periole, C.; Blanc, C.; Calvière, L.; Fontaine, L.; Viguier, A.; Albucher, J.F.; Chollet, F.; Bonneville, F.; Olivot, J.M.; Raposo, N. Prevalence and characterization of cerebral small vessel disease in young adults with intracerebral hemorrhage. Int J Stroke 2023, 18, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).