Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

11 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection, Data Collection and Analysis

2.2. Statistical Analysis - Data Distribution:

2.2.1. Univariate Analysis:

2.2.2. Bivariate Analysis:

3. Results

3.1. Age Distribution:

3.2. Crown-Rump-Length:

3.3. Nuchal Translucency:

3.4. Karyotype:

3.5. Malformations:

3.6. Malformations and/or Karyotype:

3.7. Karyotype:

3.8. Pregnancy Outcome:

3.9. Negative Outcomes and/or Abnormal Karyotype and/or Malformations:

3.10. NIPT:

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DEGUM | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ultraschall in der Medizin |

| NT | Nuchal translucency |

| CRL | Crown rump length |

References

- Nicolaides, K.H.; Azar, G.B.; Byrne, D.; Mansur, C.A.; Marks, K. Fetal nuchal translucency: ultrasound screening for chromosomal defects in first trimester of pregnancy. BMJ 1992, 304, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuhamad, A. Technical Aspects of Nuchal Translucency Measurement. Seminars in Perinatology 2005, 29, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. Abnormal first-trimester fetal nuchal translucency and Cornelia De Lange syndrome. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2002, 99, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. What is fetal nuchal translucency? BMJ 1999, 318, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, A.F.; Pandya, P.; Yüksel, B.; Greenough, A.; Patton, M.A.; Nicolaides, K.H. Outcome of chromosomally normal livebirths with increased fetal nuchal translucency at 10-14 weeks’ gestation. Journal of Medical Genetics 1998, 35, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, F.D.; Ralston, S.J.; D’Alton, M.E. Increased Nuchal Translucency and Fetal Chromosomal Defects. New England Journal of Medicine 1998, 338, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, K.H. Nuchal translucency and other first-trimester sonographic markers of chromosomal abnormalities. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004, 191, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagan, K.O.; Anderson, J.M.; Anwandter, G.; Neksasova, K.; Nicolaides, K.H. Screening for triploidy by the risk algorithms for trisomies 21, 18 and 13 at 11 weeks to 13 weeks and 6 days of gestation. Prenat Diagn 2008, 28, 1209–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaides, K.H.; Spencer, K.; Avgidou, K.; Faiola, S.; Falcon, O. Multicenter study of first-trimester screening for trisomy 21 in 75 821 pregnancies: results and estimation of the potential impact of individual risk-orientated two-stage first-trimester screening. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2005, 25, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, K.O.; Wright, D.; Valencia, C.; Maiz, N.; Nicolaides, K.H. Screening for trisomies 21, 18 and 13 by maternal age, fetal nuchal translucency, fetal heart rate, free β-hCG and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Hum Reprod 2008, 23, 1968–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, P.P.; Kondylios, A.; Hilbert, L.; Snijders, R.J.; Nicolaides, K.H. Chromosomal defects and outcome in 1015 fetuses with increased nuchal translucency. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995, 5, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugthart, M.A.; Bet, B.B.; Elsman, F.; van de Kamp, K.; de Bakker, B.S.; Linskens, I.H.; van Maarle, M.C.; van Leeuwen, E.; Pajkrt, E. Increased nuchal translucency before 11 weeks of gestation: Reason for referral? Prenat Diagn. 2021, 41, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grande, M.; Solernou, R.; Ferrer, L.; et al. Is nuchaltranslucency a useful aneuploidy marker in fetuses with crown-rump length of 28-44mm? Ultrasound Obstetr Gynecol. 2014, 43, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syngelaki, A.; Hammami, A.; Bower, S.; et al. Diagnosis of fetal non-chromosomal abnormalities on routine ultrasound examination at 11-13weeks’ gestation. Ultrasound Obstetr Gynecol. 2019, 54, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilardo, C.M.; Pajkrt, E.; de Graaf, I.; et al. Outcome of fetuses with enlarged nuchal translucency and normal karyotype. Ultrasound Obstetr Gynecol. 1998, 11, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souka, A.P.; Von Kaisenberg, C.S.; Hyett, J.A.; et al. Increased nuchal translucency with normal karyotype. Am J Obstetrics Gynecol. 2005, 192, 1005–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithner, C.U.; Kublickas, M.; Ek, S. Pregnancy outcome for fetuses with increased nuchal translucency but normal karyotype. J Med Screen. 2016, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spataro, E.; Cordisco, A.; Luchi, C.; Filardi, G.R.; Masini, G.; Pasquini, L. Increased nuchal translucency with normal karyotype and genomic microarray analysis: A multicenter observational study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2023, 161, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsch, A.; Degenhardt, J.; Stressig, R.; Dudwiesus, H.; Graupner, O.; Ritgen, J. The ‘Radiant Effect’: Recent Sonographic Image-Enhancing Technique and Its Impact on Nuchal Translucency Measurements. J. Clin. Med 2024, 13, 3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.A.; Pajkrt, E.; Bleker, O.P.; Bonsel, G.J.; Bilardo, C.M. Disappearance of enlarged nuchal translucency before 14 weeks’ gestation: relationship withchromosomal abnormalities and pregnancy outcome. Ultrasound Obstetr Gynecol. 2004, 24, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoppi, M.A.; Ibba, R.M.; Floris, M.; et al. Changes in nuchal translucency thickness in normal and abnormal karyotype fetuses. BJOG 2003, 110, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Mean (SD) / % | |

|---|---|---|

| CRL | 39.95 (3.47) | |

| NT | 4.40 (1.4) | |

| Gestational Age (days) | 76.45(4.65) | |

| NT | 2.50-3.49mm | 63 (30.3%) |

| 3.50-4.49mm | 63 (30.3%) | |

| 4.50-5.49mm | 36 (17.3%) | |

| ≥ 5.50mm | 46 (22.1%) | |

| Karyotype | Missing | 47 (22.6%) |

| Normal | 94 (45.2%) | |

| Trisomy 18 | 32 (15.4%) | |

| Trisomy 13 | 4 (1.9%) | |

| Trisomy 21 | 11 (5.3%) | |

| Monosomy | 13 (6.3%) | |

| Structural chromosomal abnormality | 3 (1.4%) | |

| Triploidy | 3 (1.4%) | |

| Trisomy 9 | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Invasive Testing and/or NIPT | No | 45 (21.6%) |

| CVS | 150 (72.1%) | |

| Amniocentesis | 2 (1.0%) | |

| NIPT | 4 (1.9%) | |

| Unknown | 6 (2.9%) | |

| CVS and Amniocentesis | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Aneuploidy | No | 94 (45.2%) |

| Yes | 64 (30.8%) | |

| Unknown/Missing | 50 (24.0%) | |

| Termination of Pregnancy | No | 106 (51.0%) |

| Yes | 56 (26.9%) | |

| Unknown/Missing | 46 (22.1%) | |

| Malformation | No | 65 (31.3%) |

| Yes | 57 (27.4%) | |

| Unknown/Missing | 86 (41.3%) | |

| Cardiac Anomalies | No | 68 (32.7%) |

| Yes | 36 (17.3%) | |

| Unknown/Missing | 104 (50%) | |

| Abnormal soft markers beyond other than NT | No | 96 (46.2%) |

| Yes | 74 (35.6%) | |

| Unknown/Missing | 38 (18.3%) |

| NT | Normal Karyotype |

Trisomy 18 | Trisomy 13 | Trisomy 21 | Monosomy | Structural Chromosomale Anaomalies | Triploidy | Trisomy 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.50-3.49mm | 32 (74.4%) |

4 (9.3%) |

1 (2.3%) |

3 (6.9%) |

2 (4.7%) |

0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 1 (2.3%) |

| 3.50-4.49mm | 35 (68.6%) |

5 (9.8%) |

1 (2.0%) |

6 (11.8%) |

0(0.0%) | 2 (3.9%) |

2 (3.9%) |

0(0.0%) |

| 4.50-5.49mm | 15 (48.4%) |

12 (38.7%) |

0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 3 (9.7%) |

1 (3.2%) |

0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) |

| ≥ 5.50mm |

12 (33.3%) |

11 (30.5%) |

2 (5.6%) |

2 (5.6%) |

8 (22.2%) |

0(0.0%) | 1 (2.8%) |

0(0.0%) |

| Total | 94 (58.4%) |

32 (19.9%) |

4 (2.5%) |

11 (6.8%) |

13 (8.1%) |

3 (1.9%) |

3 (1.9%) |

1 (0.6%) |

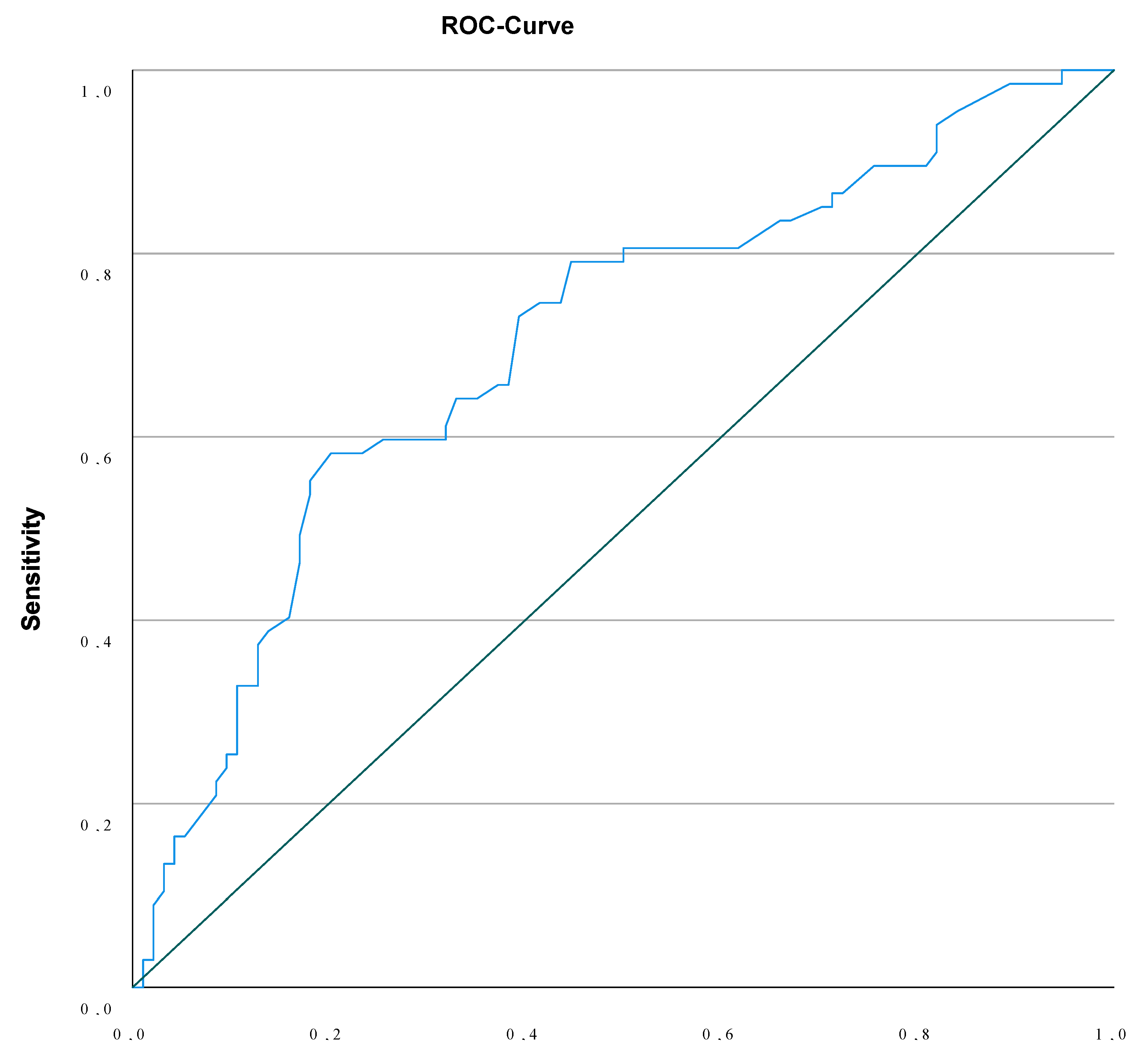

| Malformation and/or Aneuploidy | NT < 3.595mm | NT ≥ 3.595mm | Chi-square P<0.000 |

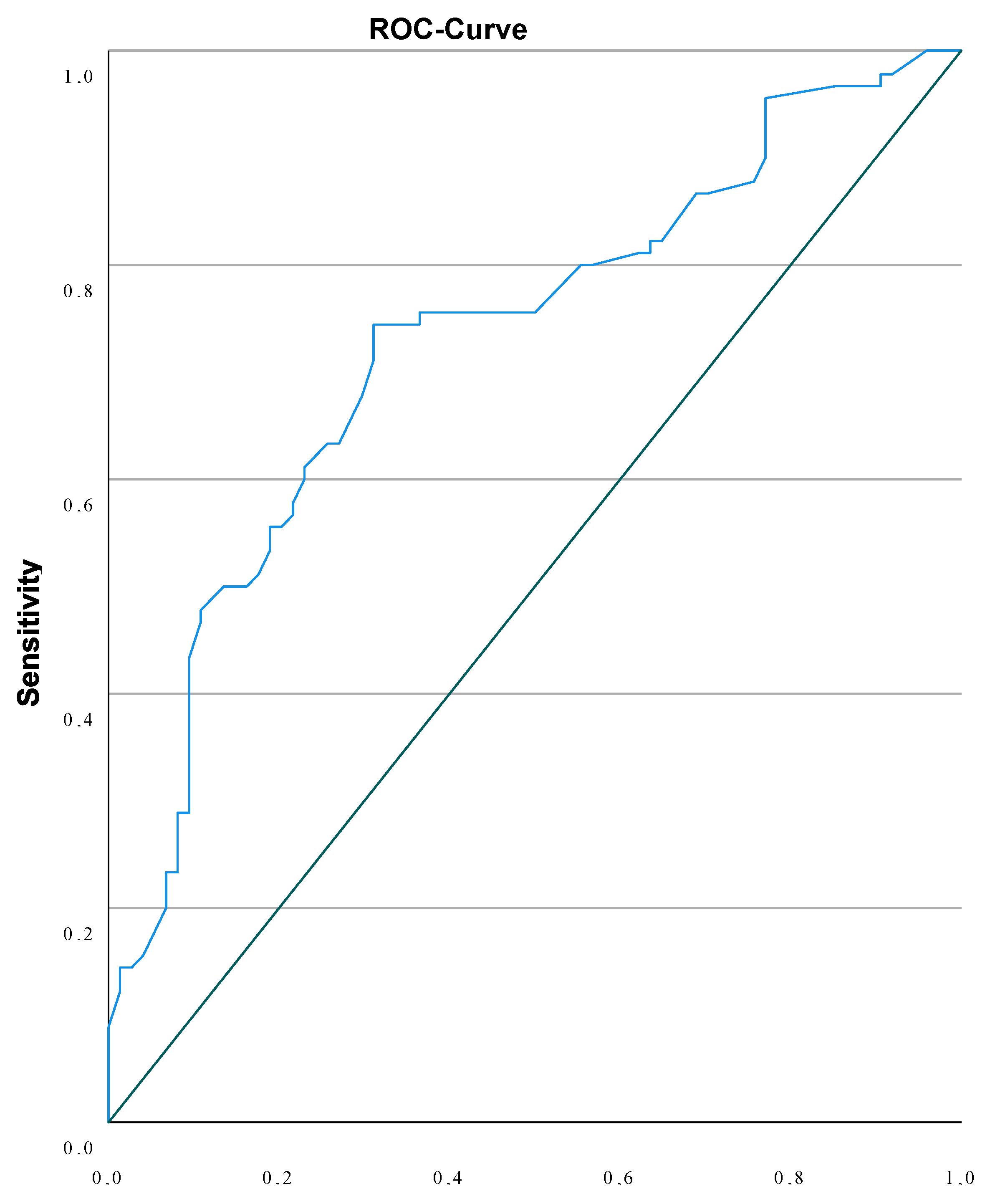

| Adverse Outcome | NT < 3.89mm | NT ≥ 3.89mm | Chi-square P<0.001 |

| 25.6% | 74.4% |

| Not detected by NIPT | |

|---|---|

| Monosomy X | 13 (19.4%) |

| Structural Chromosomale Defects | 3 (4.5%) |

| Triploidy | 3 (4.5%) |

| Trisomy 9 | 1 (1.5%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).