Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Brief Overview

1.2. Brief Comparison and Explanation

1.3. Research Aim

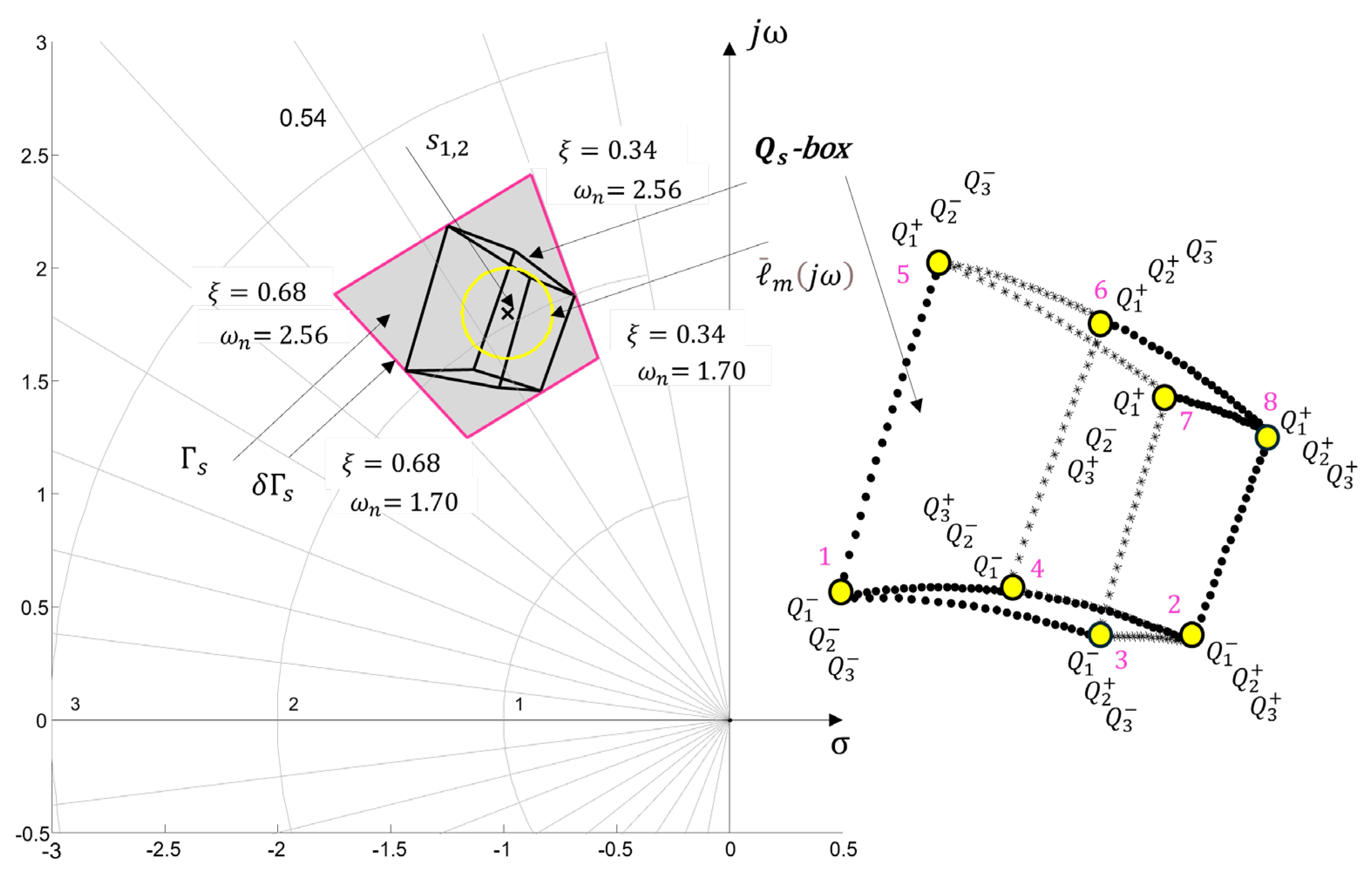

2. Gamma Regions

2.1. Definition of the Performance Region in the -Plane

2.2. Defining of the Performance Region in the –Plane

- , – for

- – for

- , – for

3. Robustness in the s-Plane

3.1. Calculation of Sensitivity Functions and .

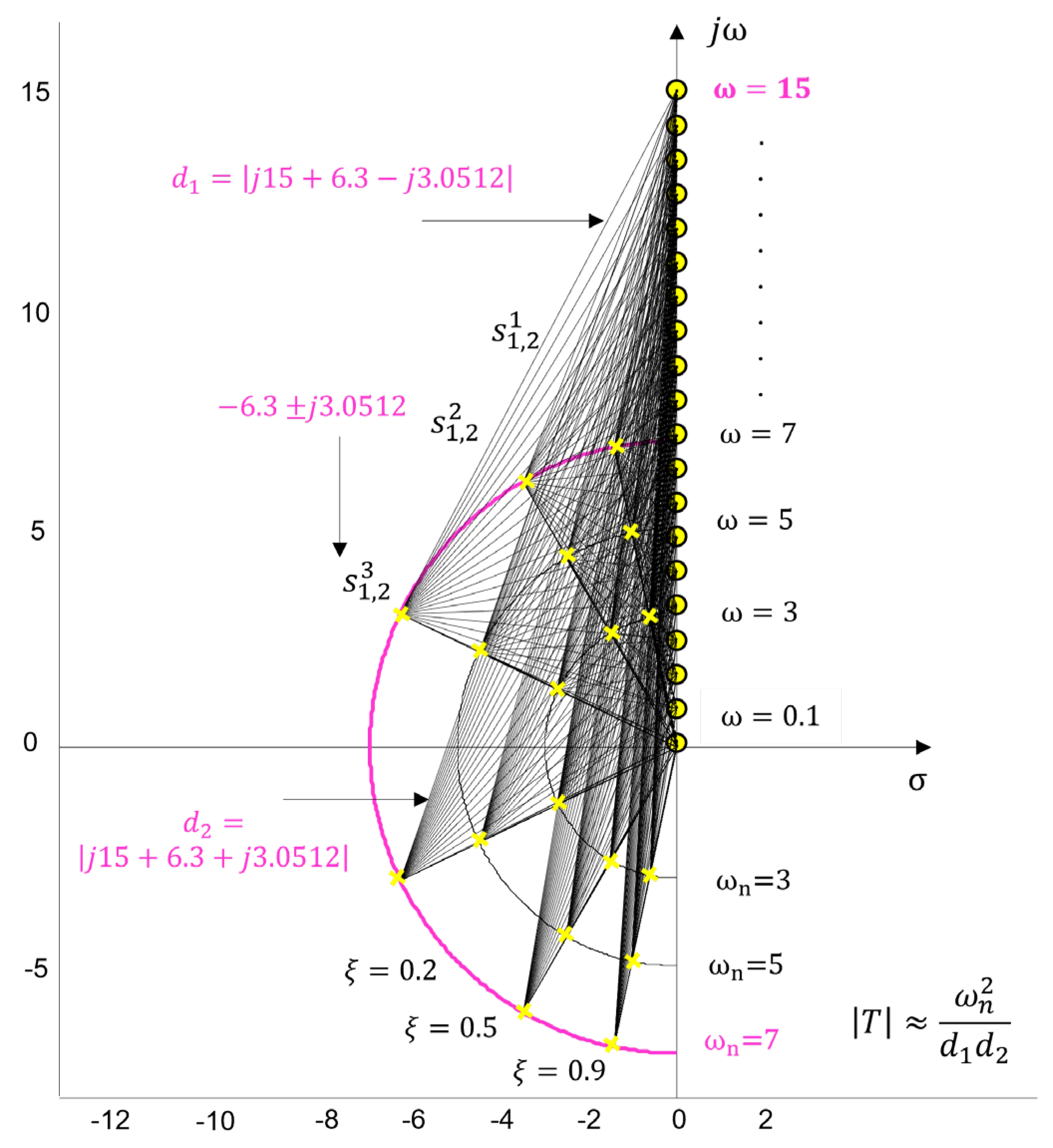

- If the control point frequency is close to the dominant poles and the distance to the imaginary axis is small, the magnitude becomes large, and the control system will exhibit oscillatory-damped transient responses.

- If the control point is far from the poles , is smaller, and the control system will show faster time response at that frequency .

- When , the magnitude of the closed-loop system tends to approach 1 more rapidly, and the system sensitivity remains low for a fixed damping ratio . However, if the value of , where changes, the real part of the dominant poles decreases, leading to an increase in the magnitude of the sensitivity function , as shown in Table A1.

- When , the magnitude , regardless of the value of the damping ratio , which results in , also shown in Table A1.

3.1.1. Discussion

- The dominant roots of the closed-loop system , which characterize the control of the real process must be located sufficiently far from every point , on the imaginary axis so that the magnitude remains acceptably small to compensate for the uncertainty .

- If the magnitude is larger, this leads to oscillations in the transient responses, a general reduction in system stability, and the robustness condition (31) will be violated.

- If are located close to the points on the imaginary axis , the distances and become small, i.e., is large, and stability decreases. On the other hand, this implies that will be small, (30), which is an indication of insensitivity.

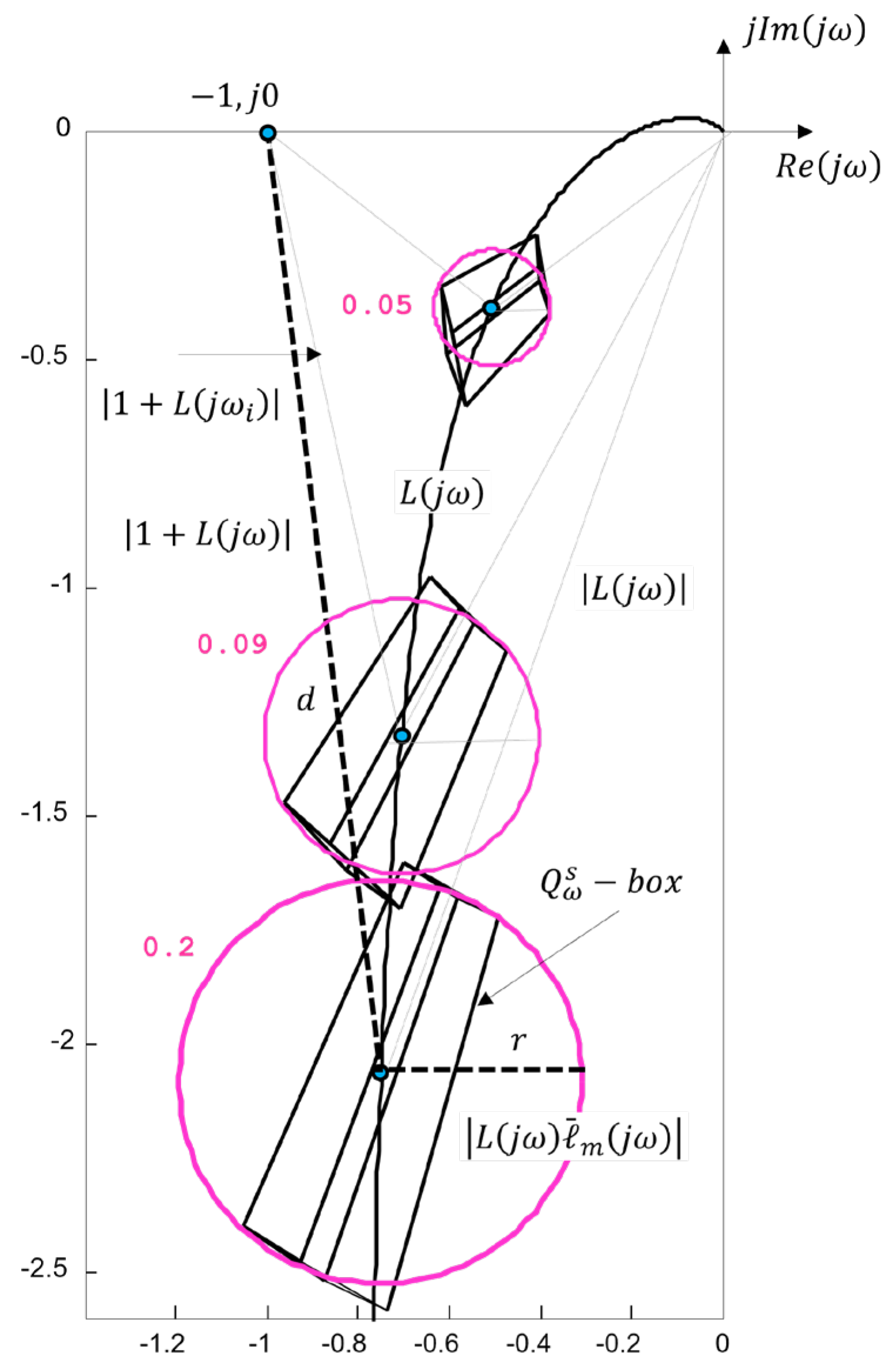

3.2. Robust Stability and Robust Performance (

3.2.1. Discussion

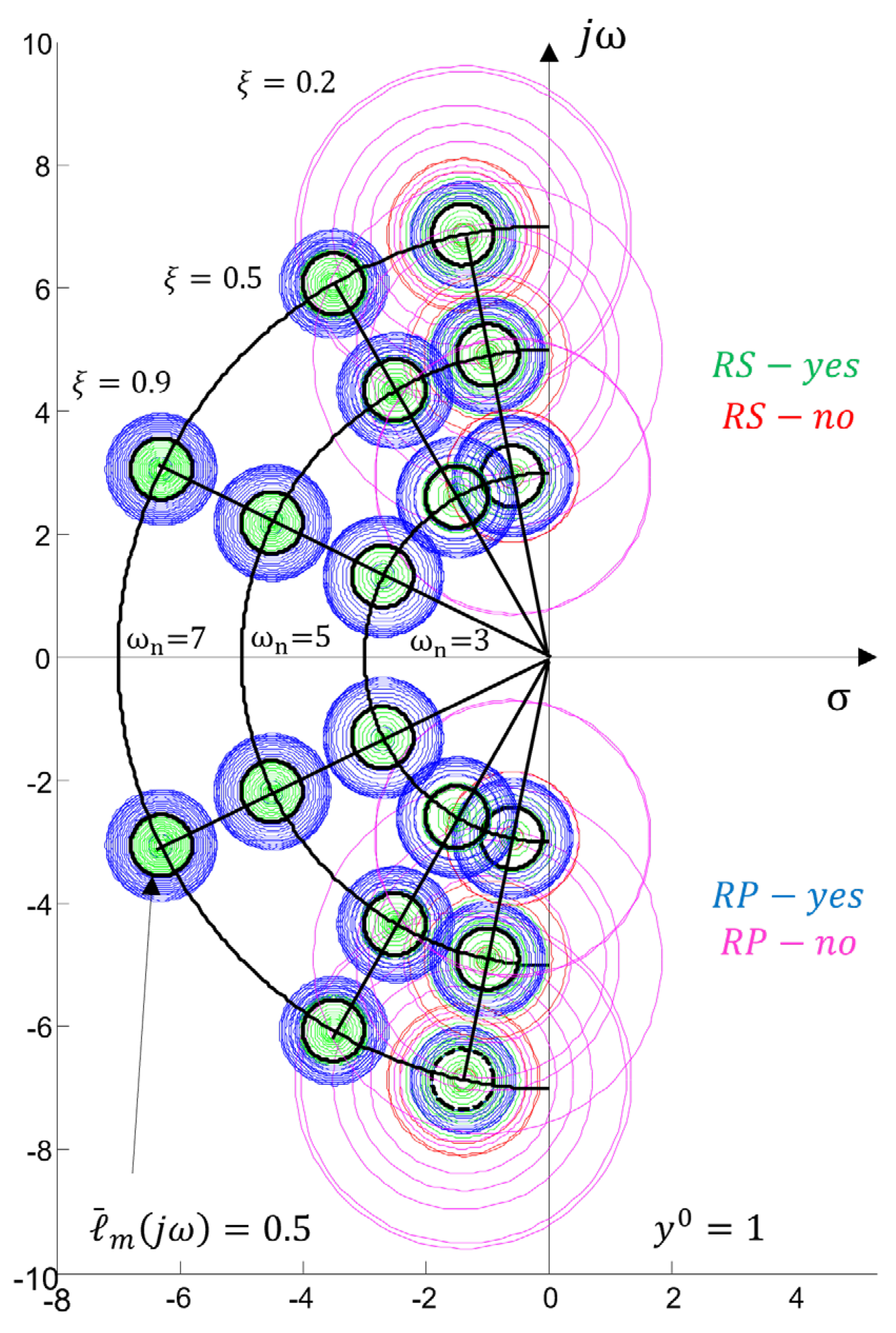

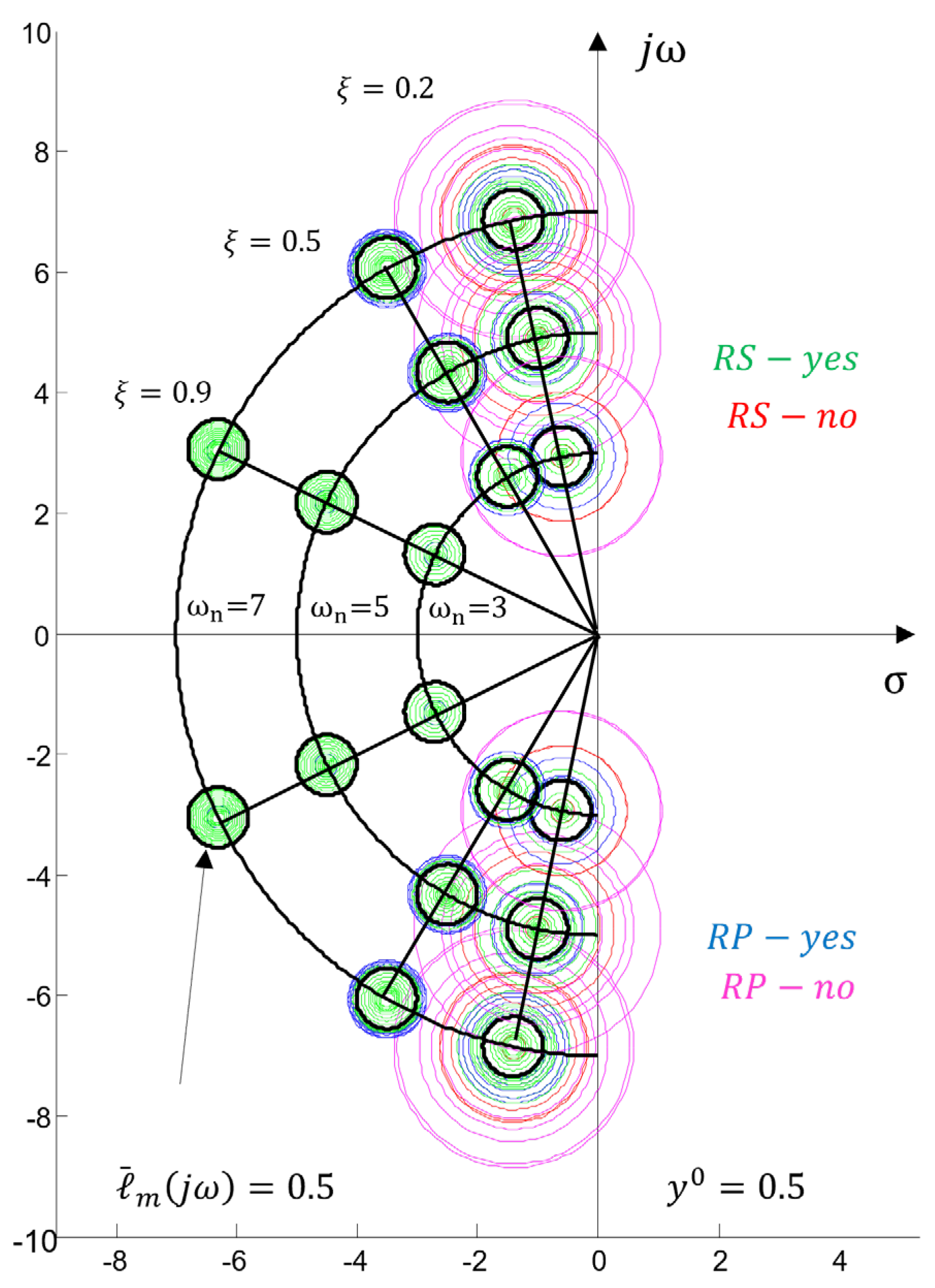

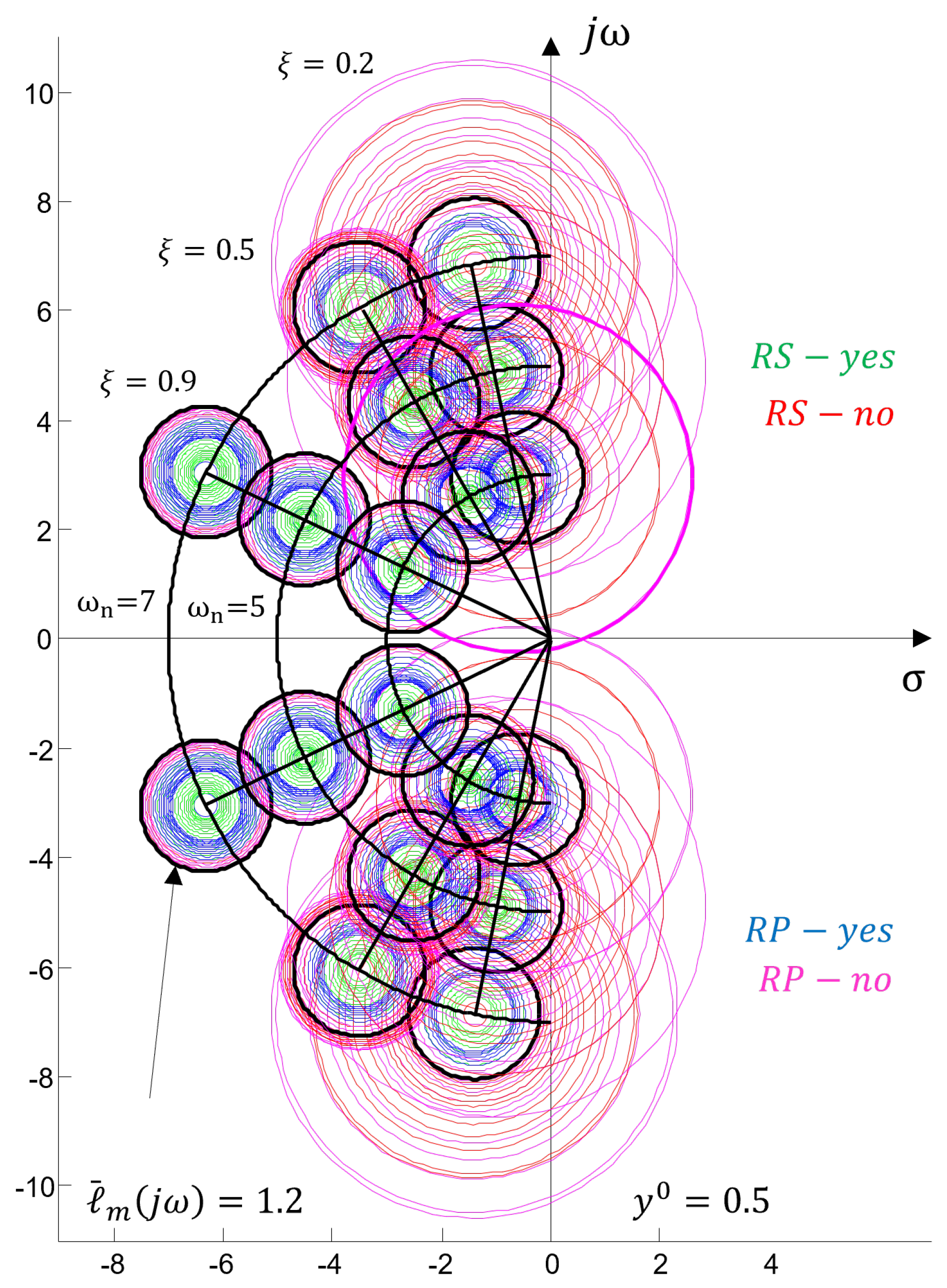

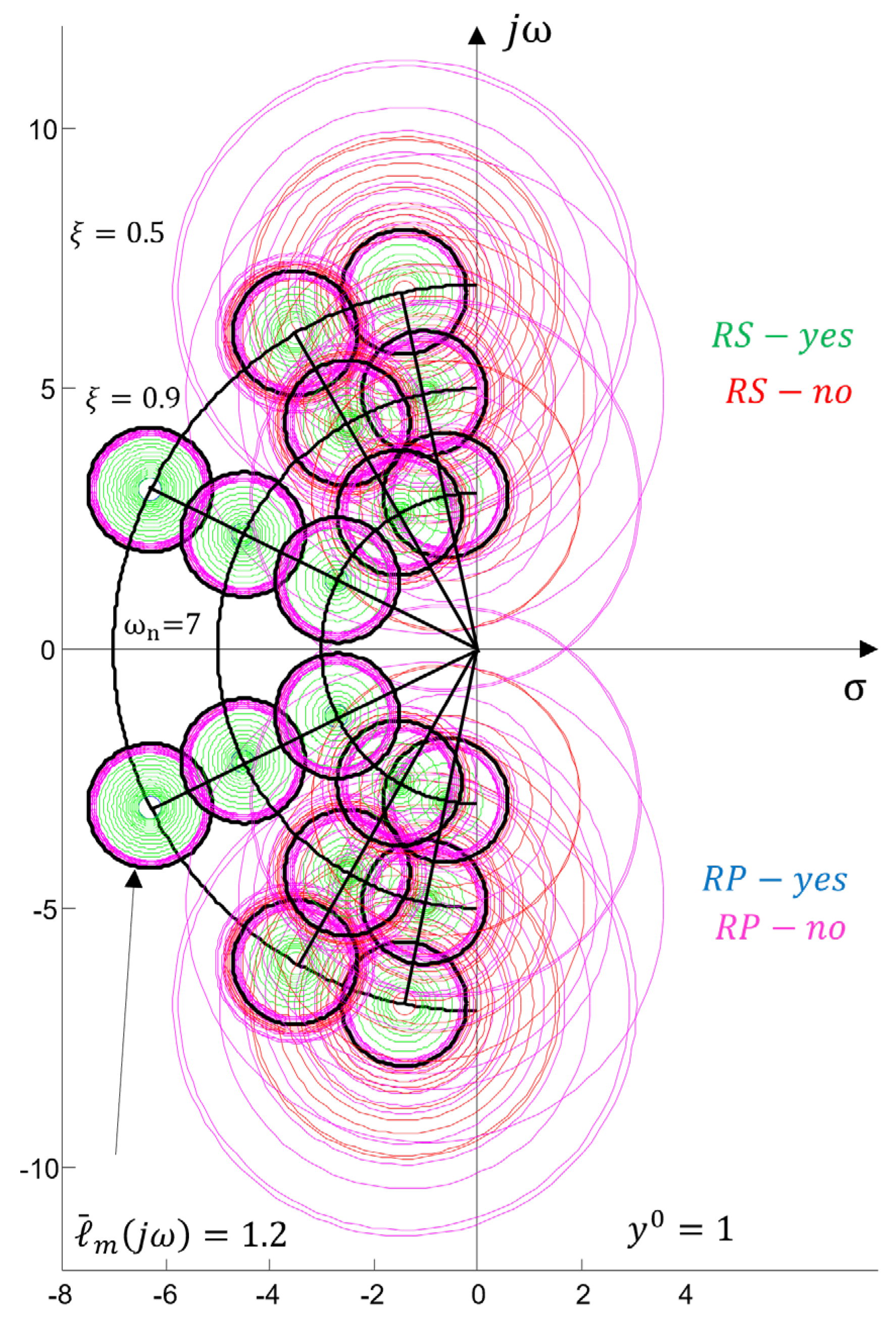

- A quick engineering analysis when applying the proposed strategy for evaluating robust properties from the complex plane boils down to checking the radii of the circles. Larger radii and indicate smaller margins of robust stability and robust performance , as seen in Figure 6 and Table A1. The intersection of circles obtained when conditions (31) and (32) are violated is an indicator of a potential loss of stability of the system/process control (classical analysis is required for confirmation).

- Visualization of regions defined by circles in the complex plane allows searching for solutions that will reduce the radii and n order to bring the regions into the desired performance region. This shows that the study of robust properties in controlling real processes from the root locus plane is a feasible approach, which can be easily automated and provide information to expert systems and designers for preliminary and/or final selection of a control algorithm.

4. Parametric Uncertainty Models

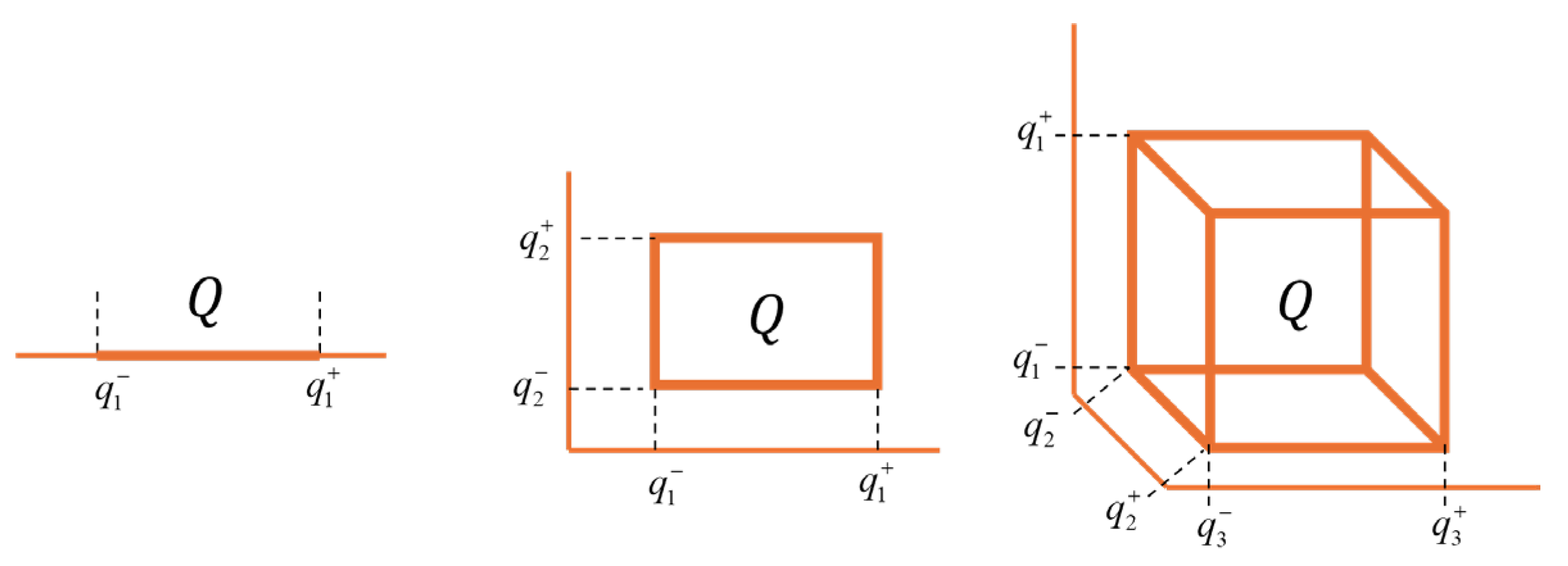

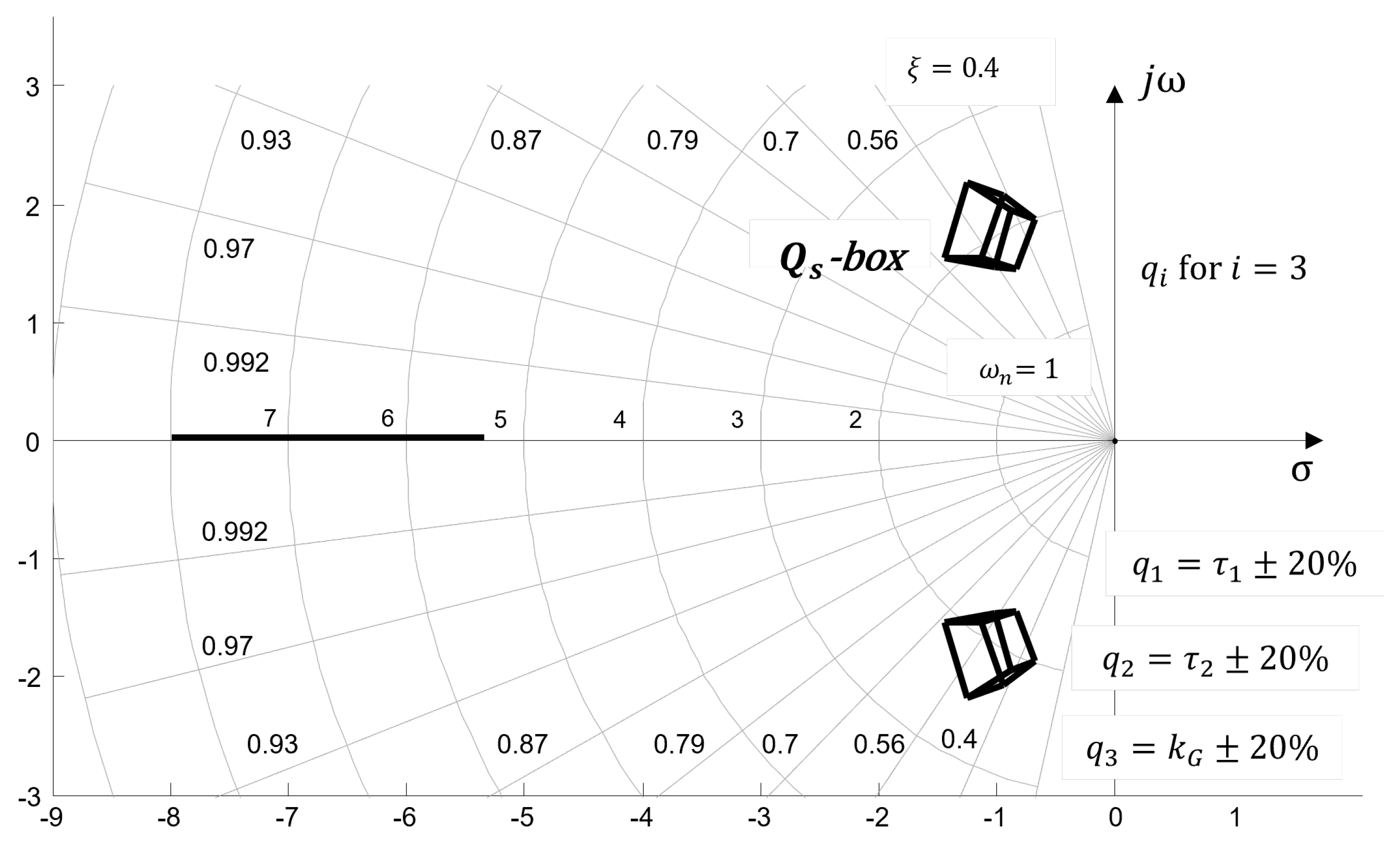

4.1. Q−box. Parameters Uncertainty

4.2. Generation in s-Complex Roots Plane

- For values of the root locus enters the class of negative root locus ().

- When modifying equation (52), it is possible that equation (53) violates the physical realizability condition, resulting in - that is, the order of the numerator polynomial exceeds the order of the denominator polynomial in the open-loop transfer function. Therefore, instead of using , as the varying parameter, the Evans coefficient function is represented by .

- In case of a nonlinear dependence of , the usual rules for constructing the root locus are not applicable.

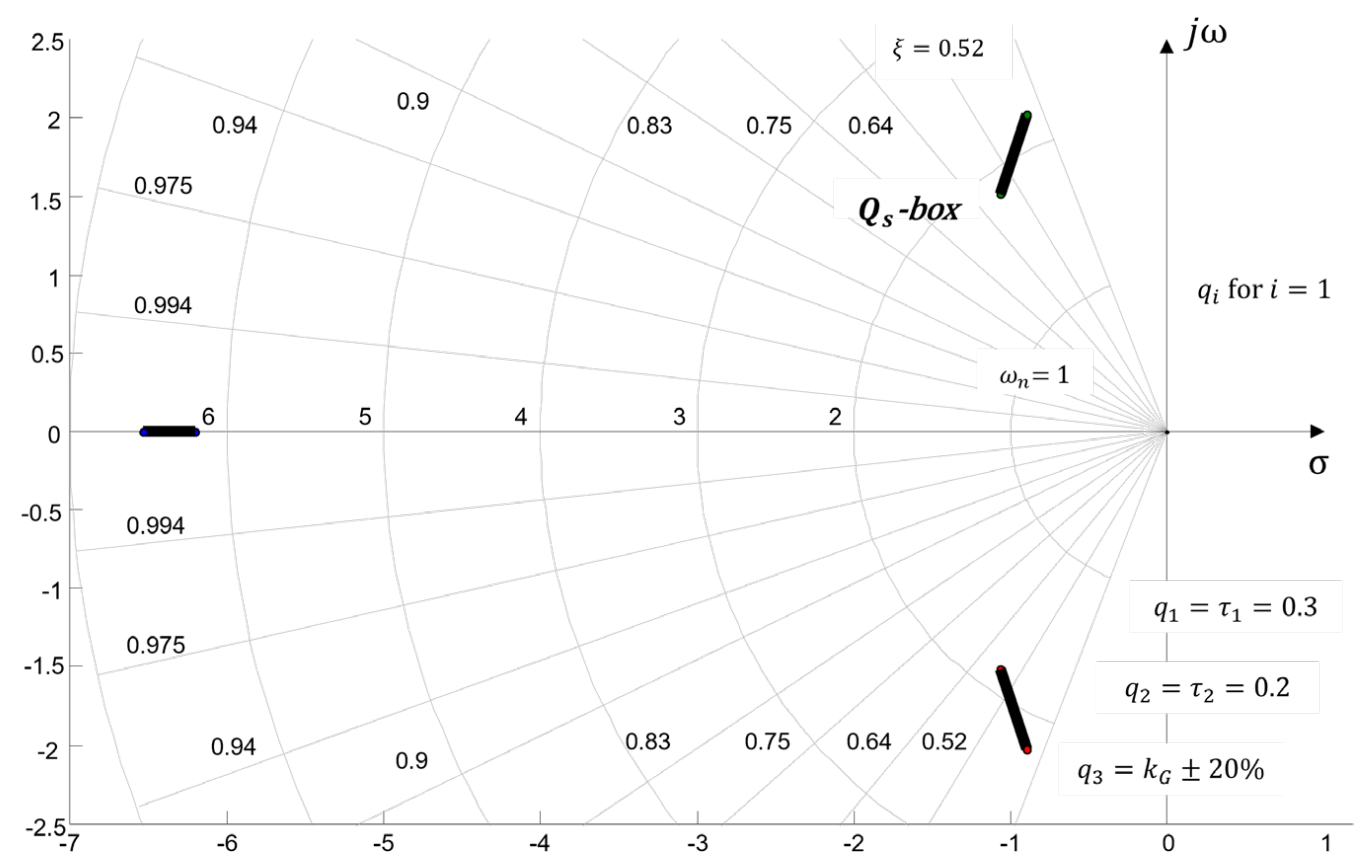

4.2.1. Numerical Example

- Discussion

- 1.

- Case 1 -

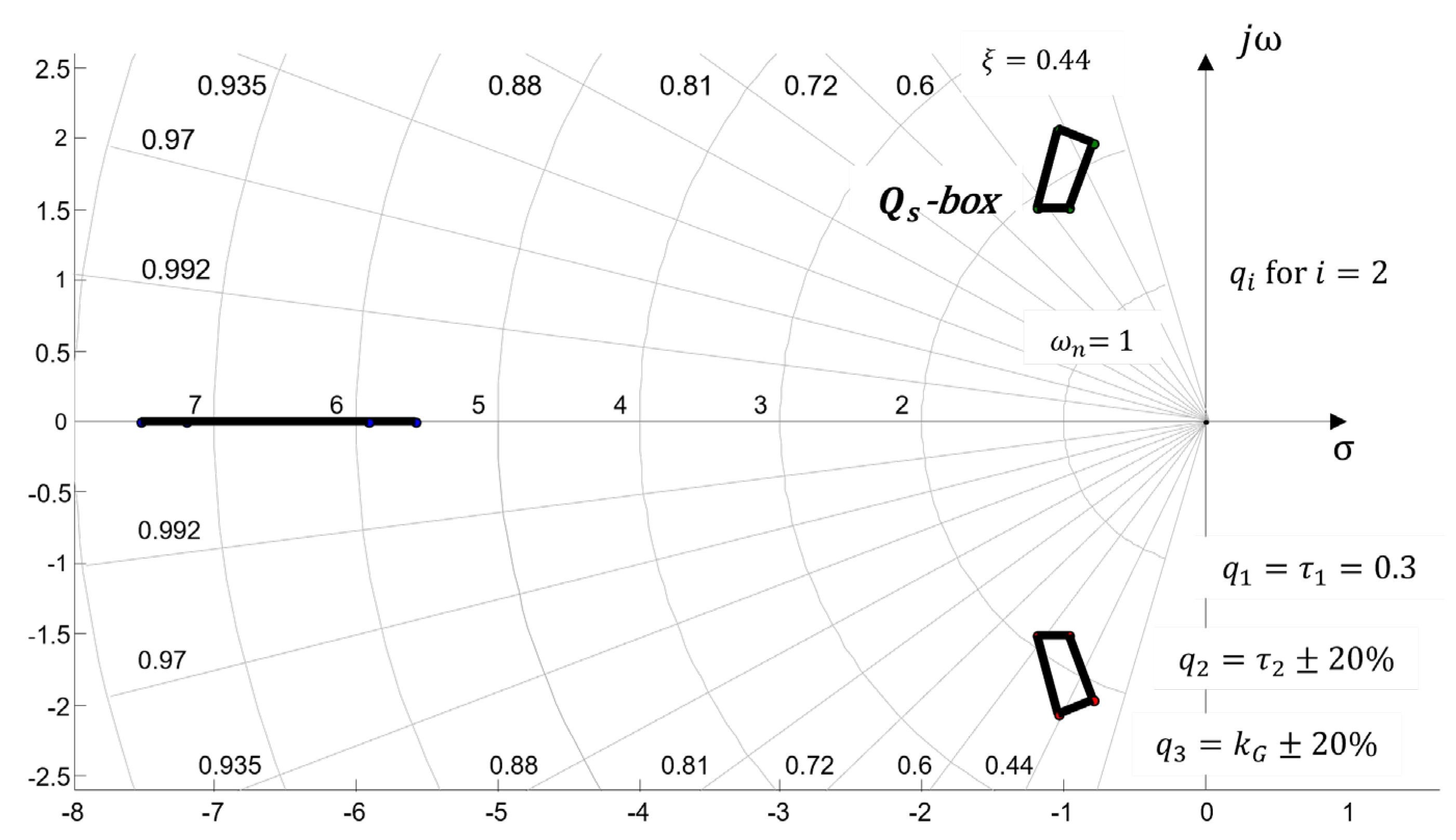

- 2.

- Case 2 -

- 3.

- Case 3 - for , , , ,

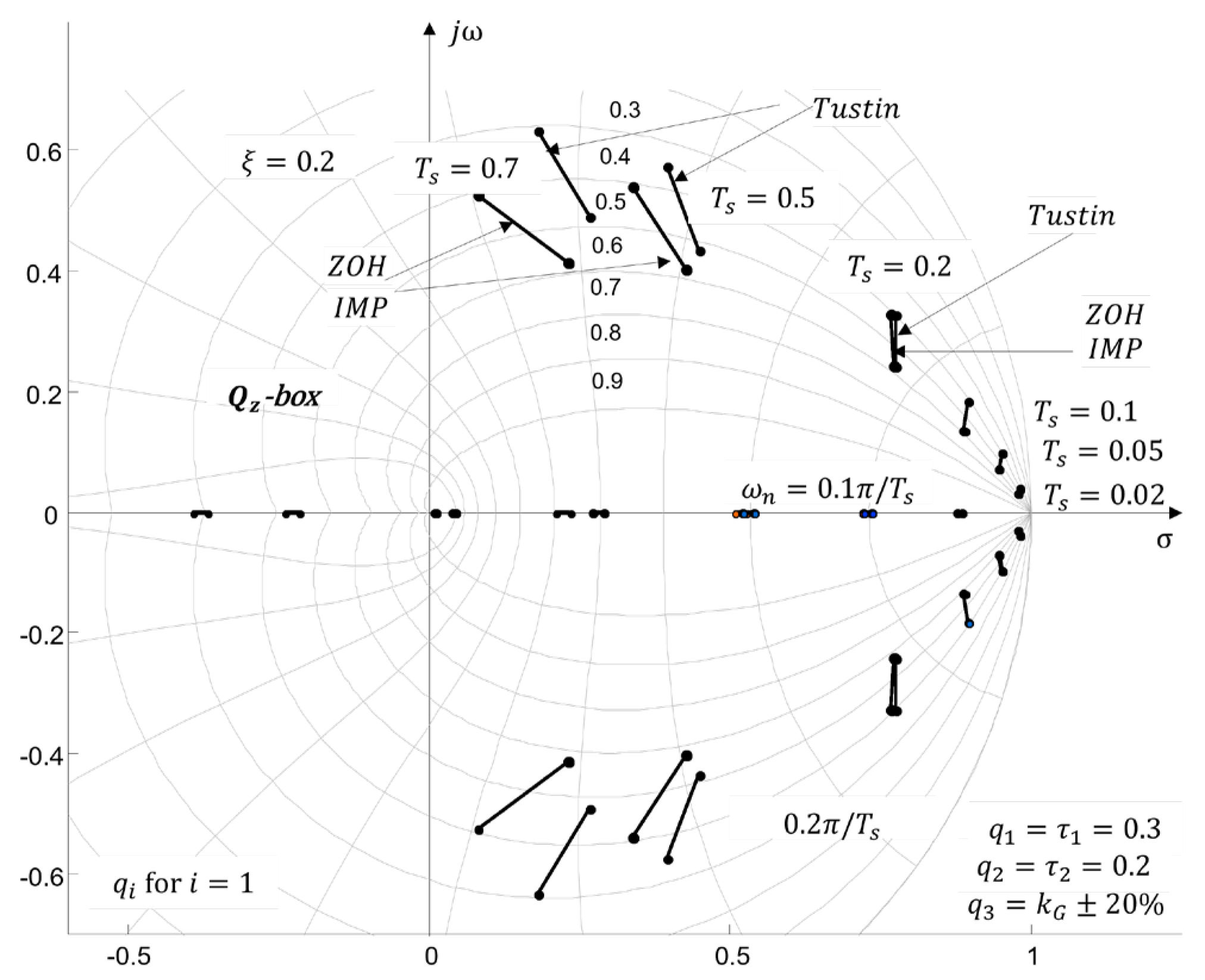

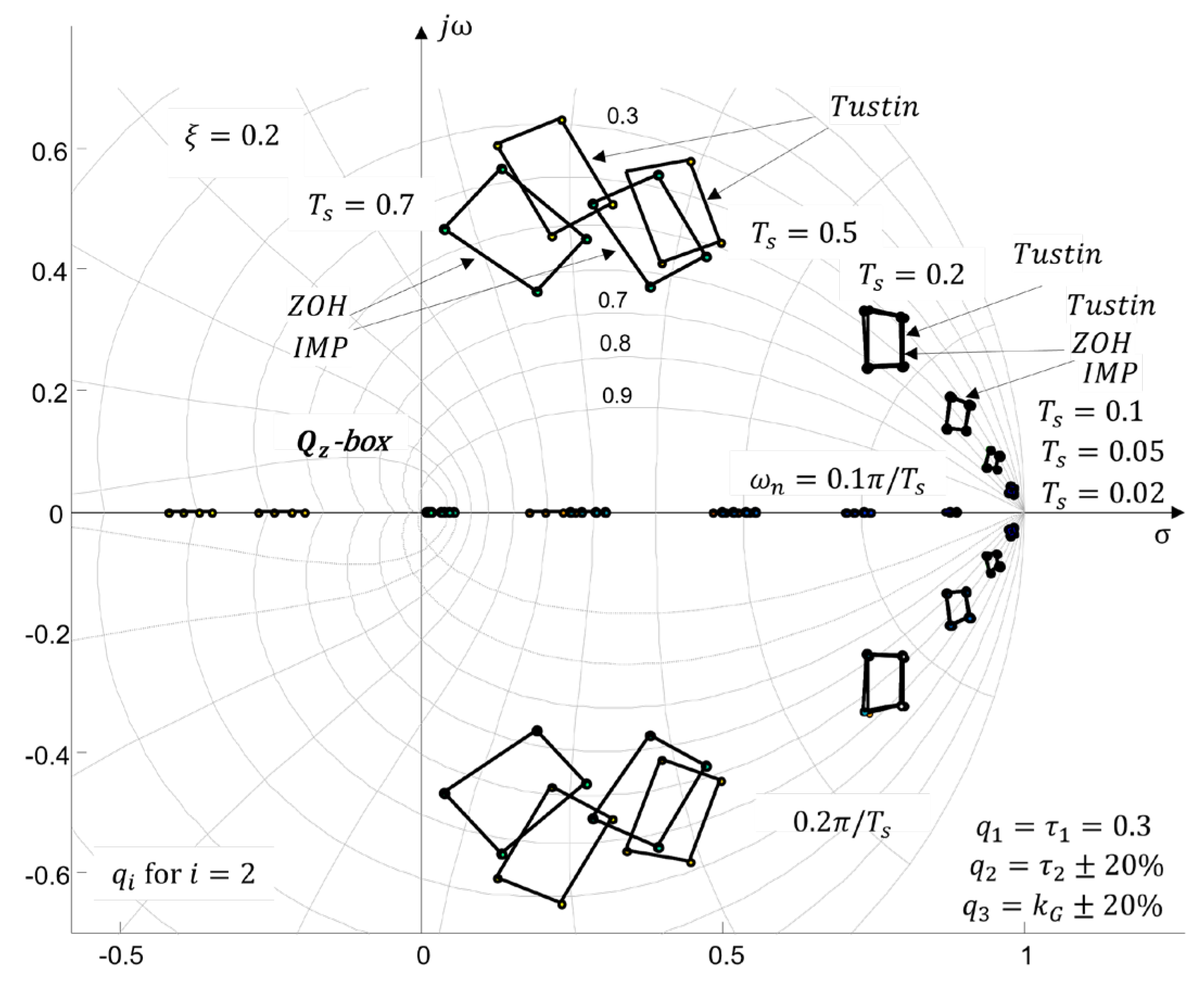

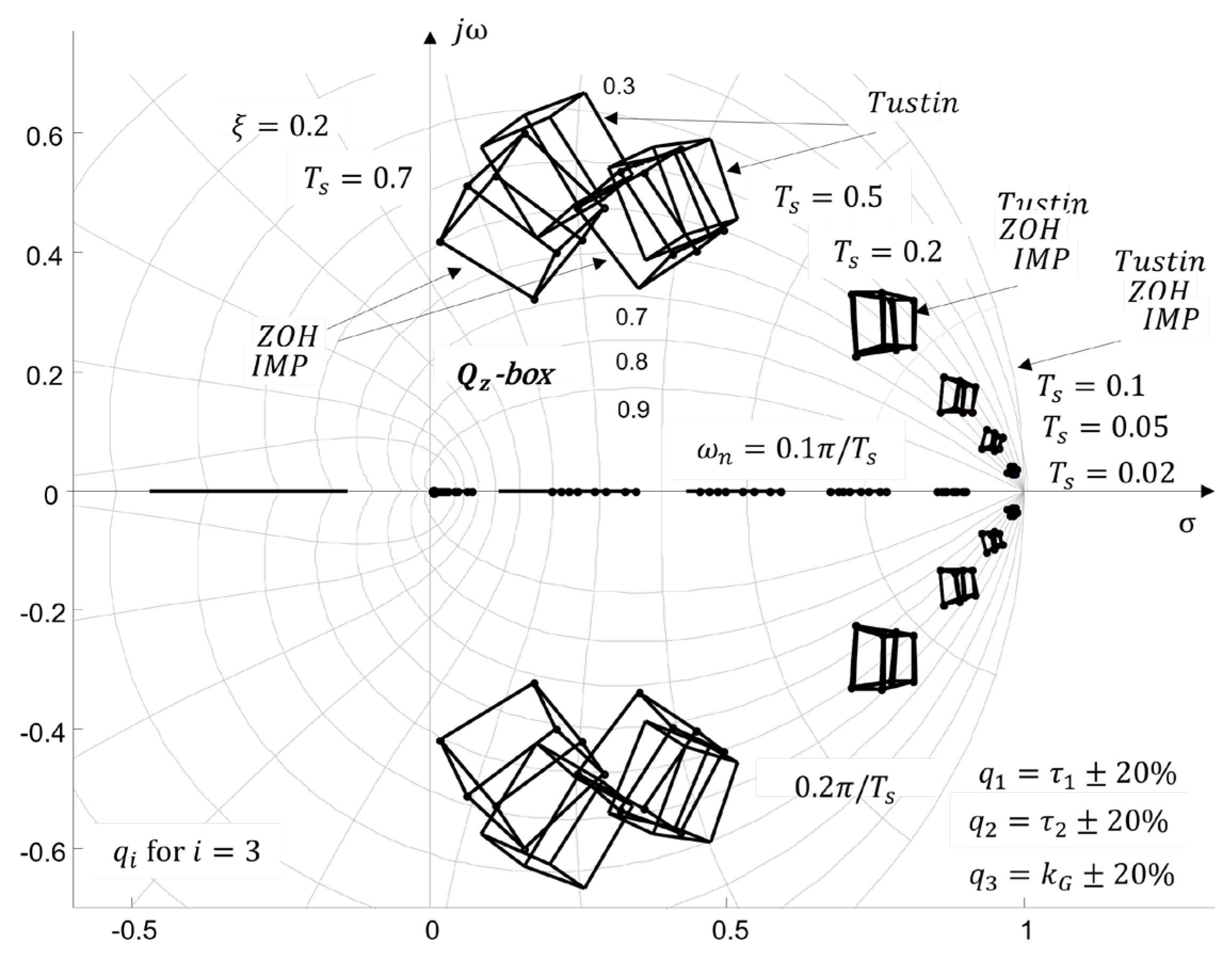

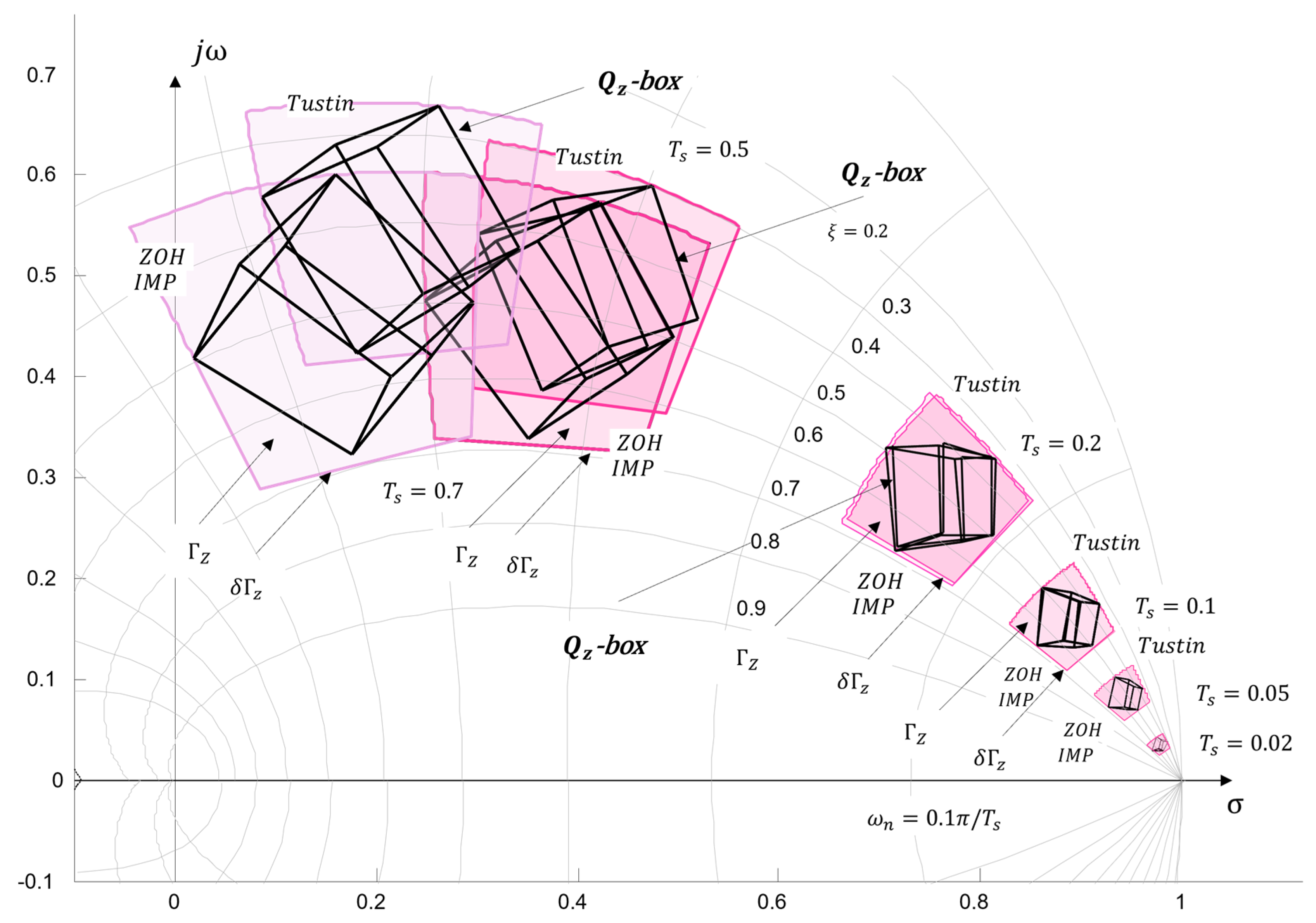

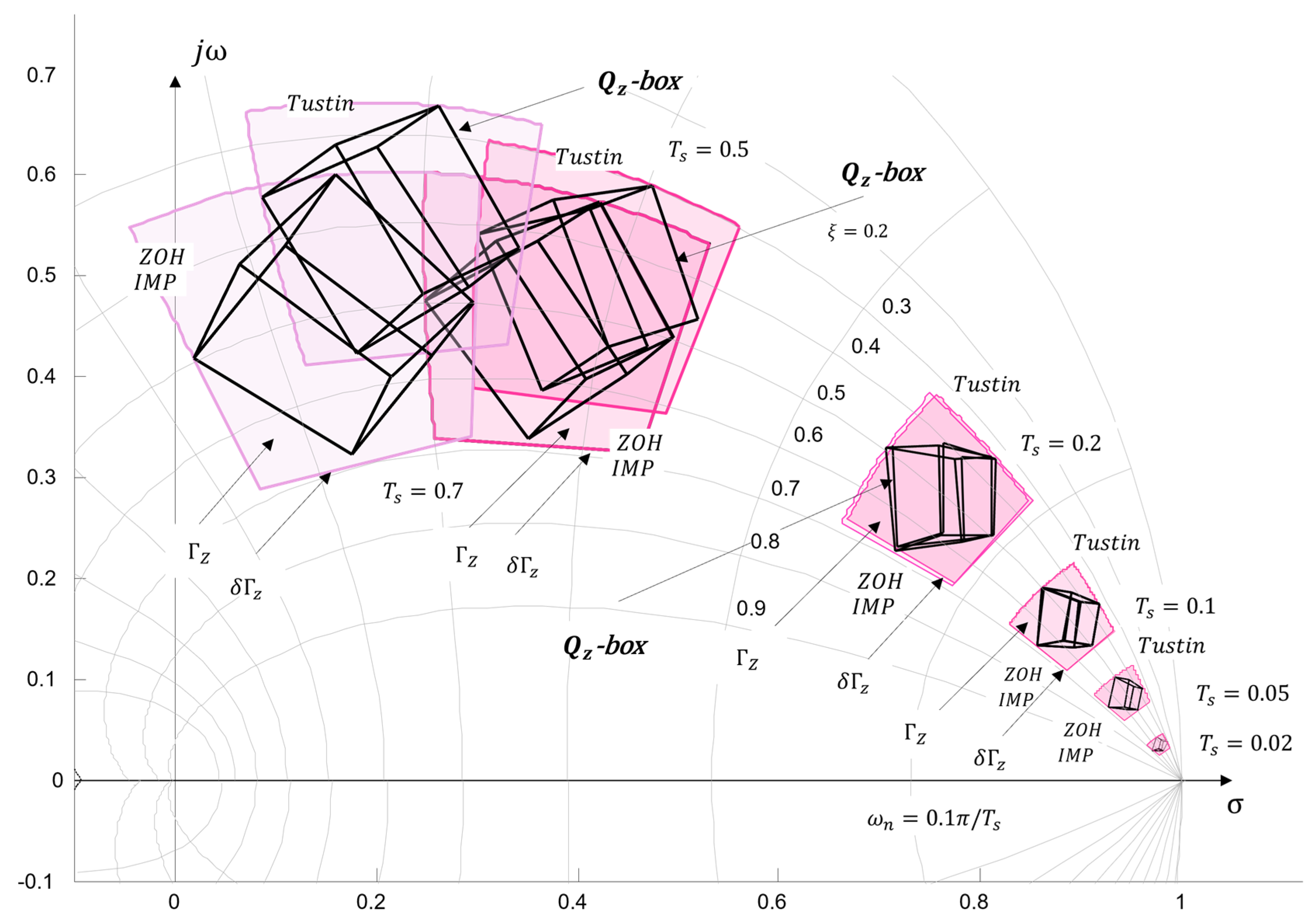

4.3. Generation in z-Complex Roots Plane

4.3.1. Numerical Example

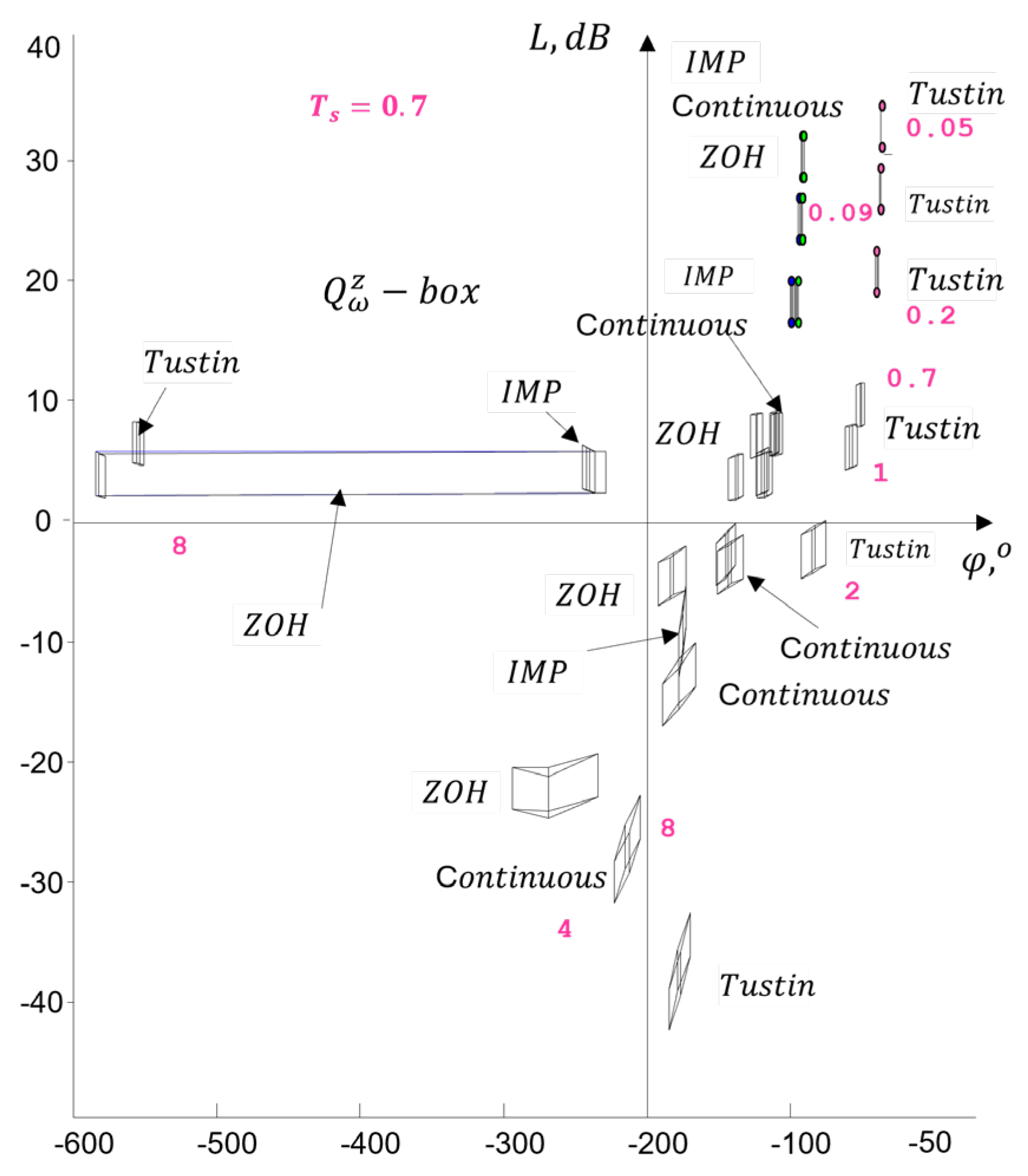

- Discussion

- Discussion.

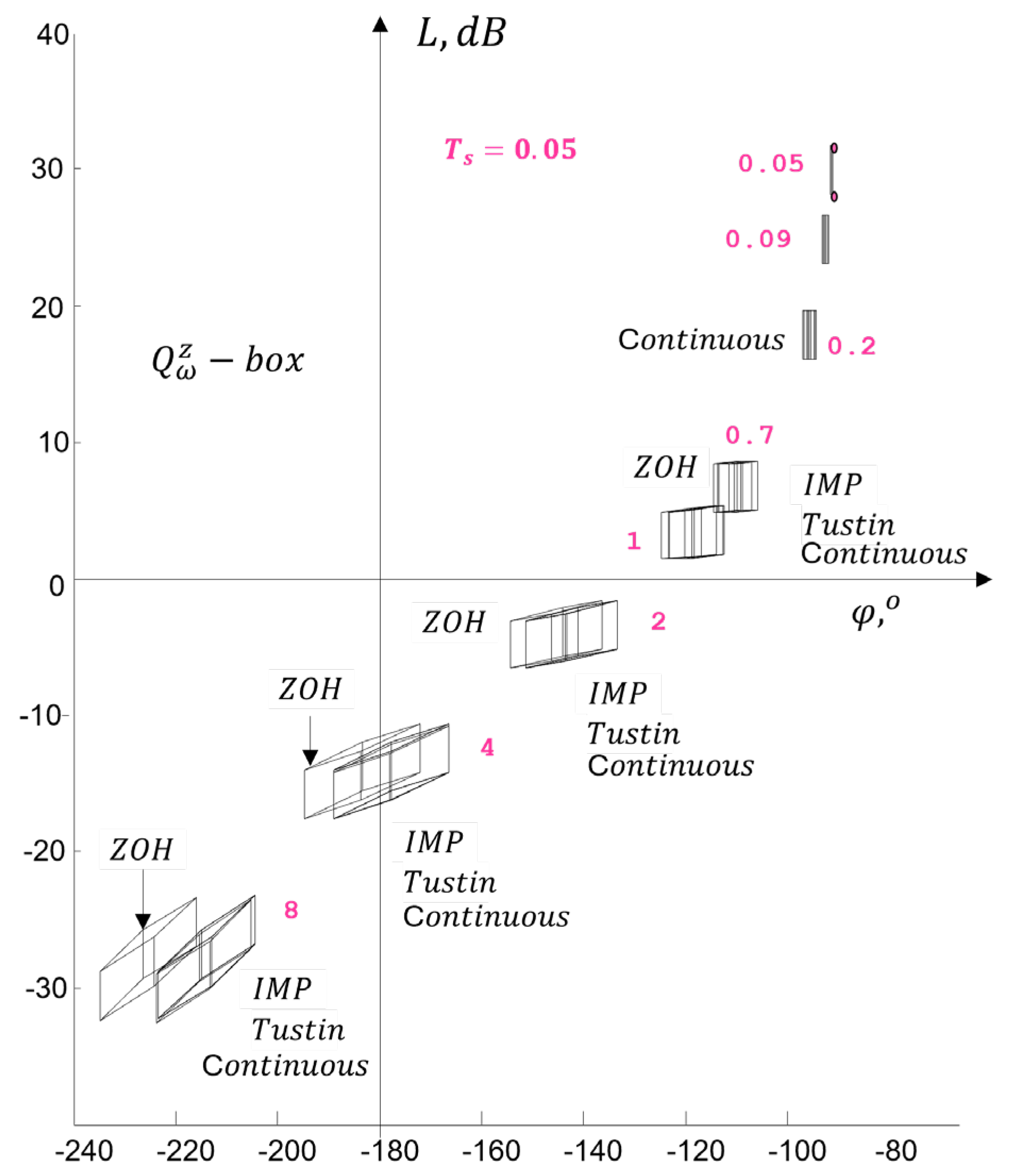

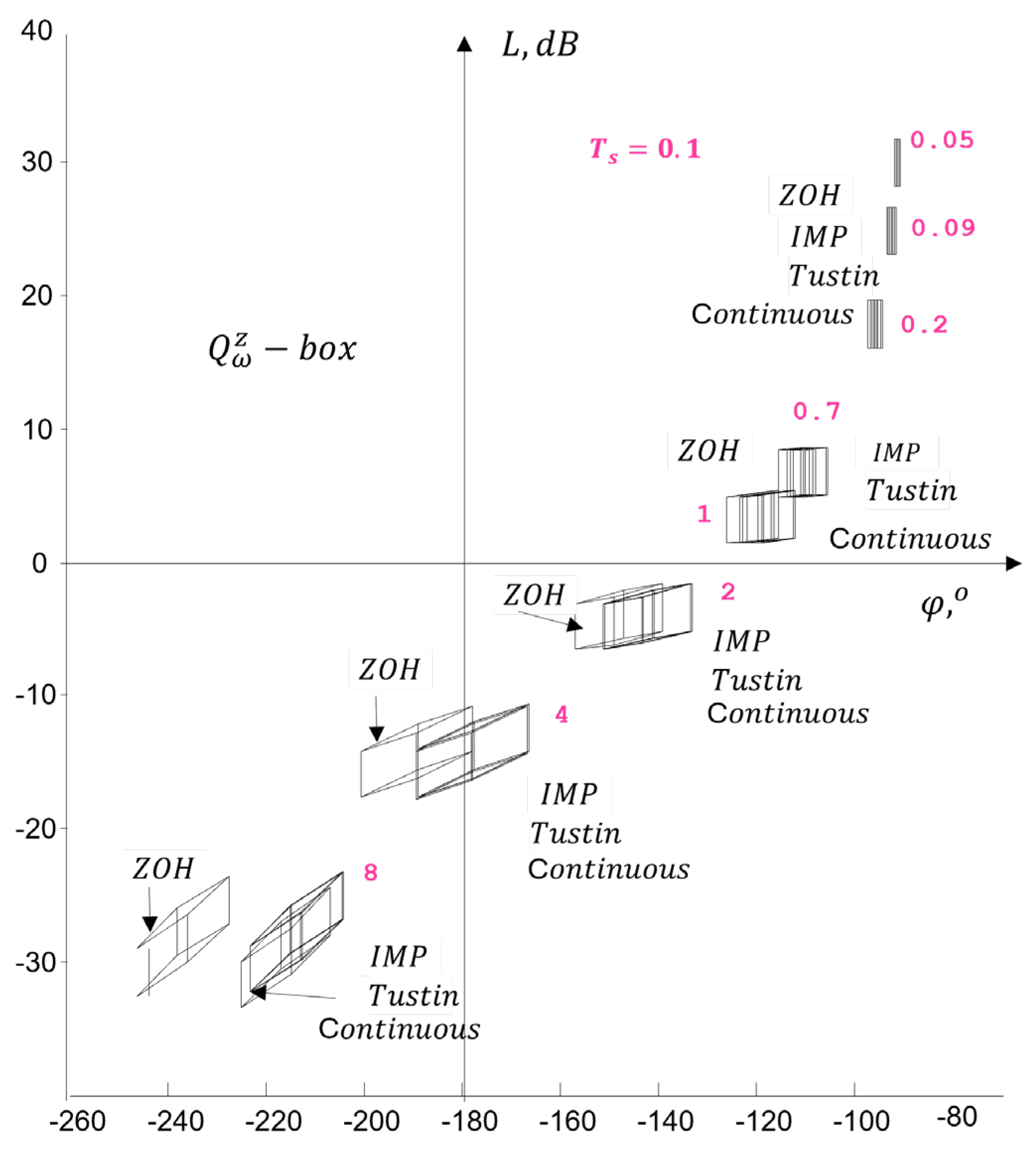

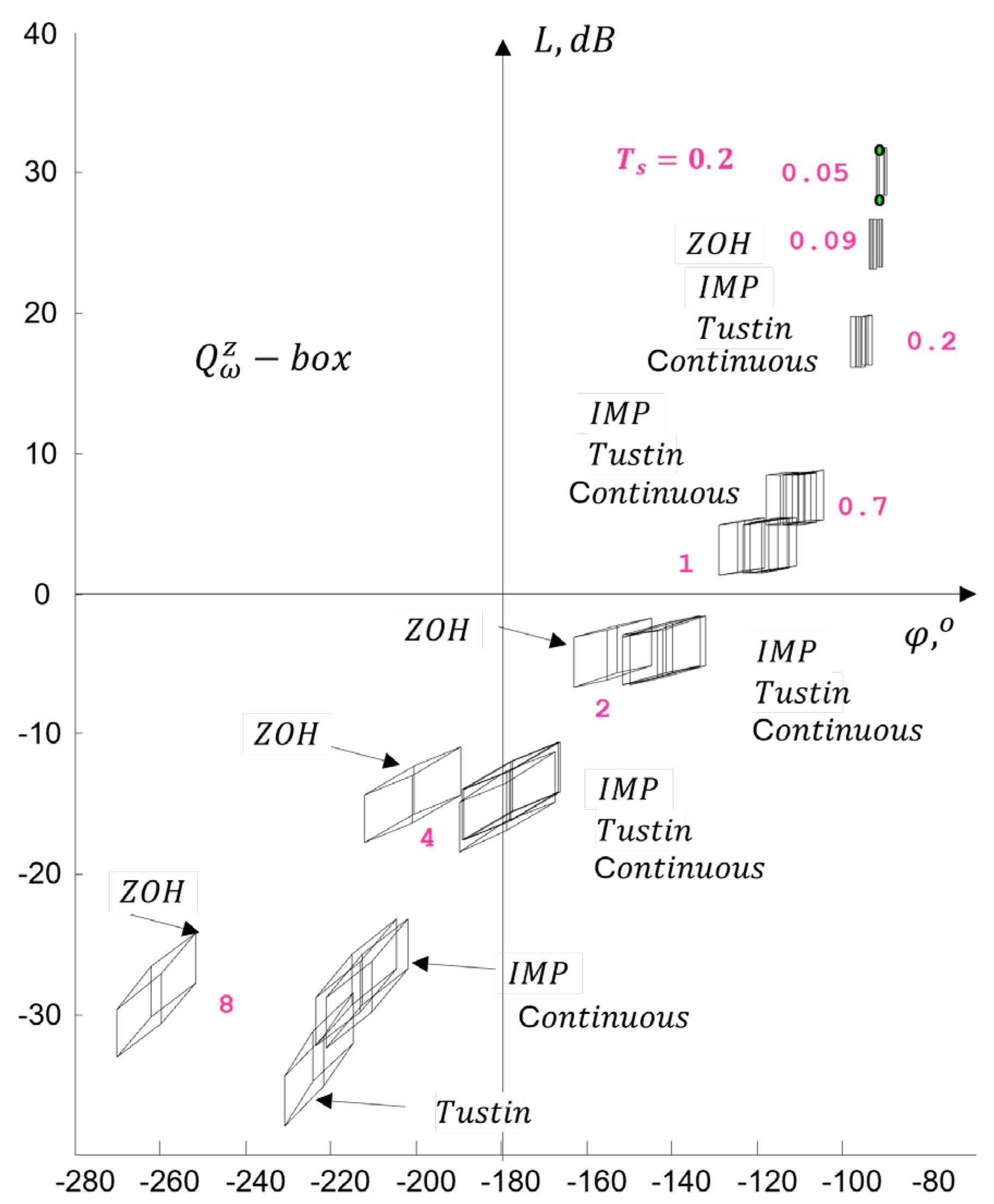

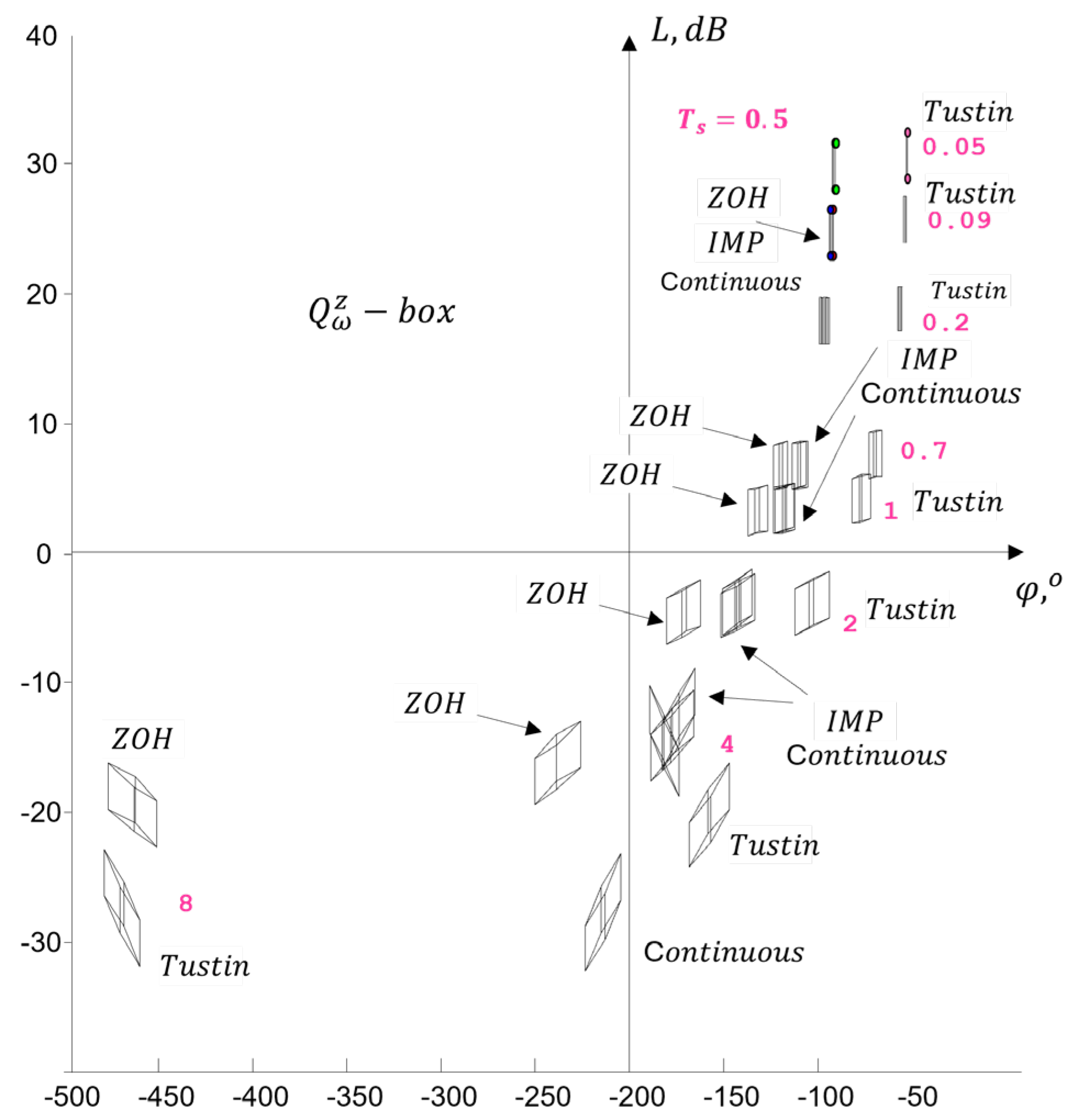

4.3.2. Study of the Influence of Sampling Time

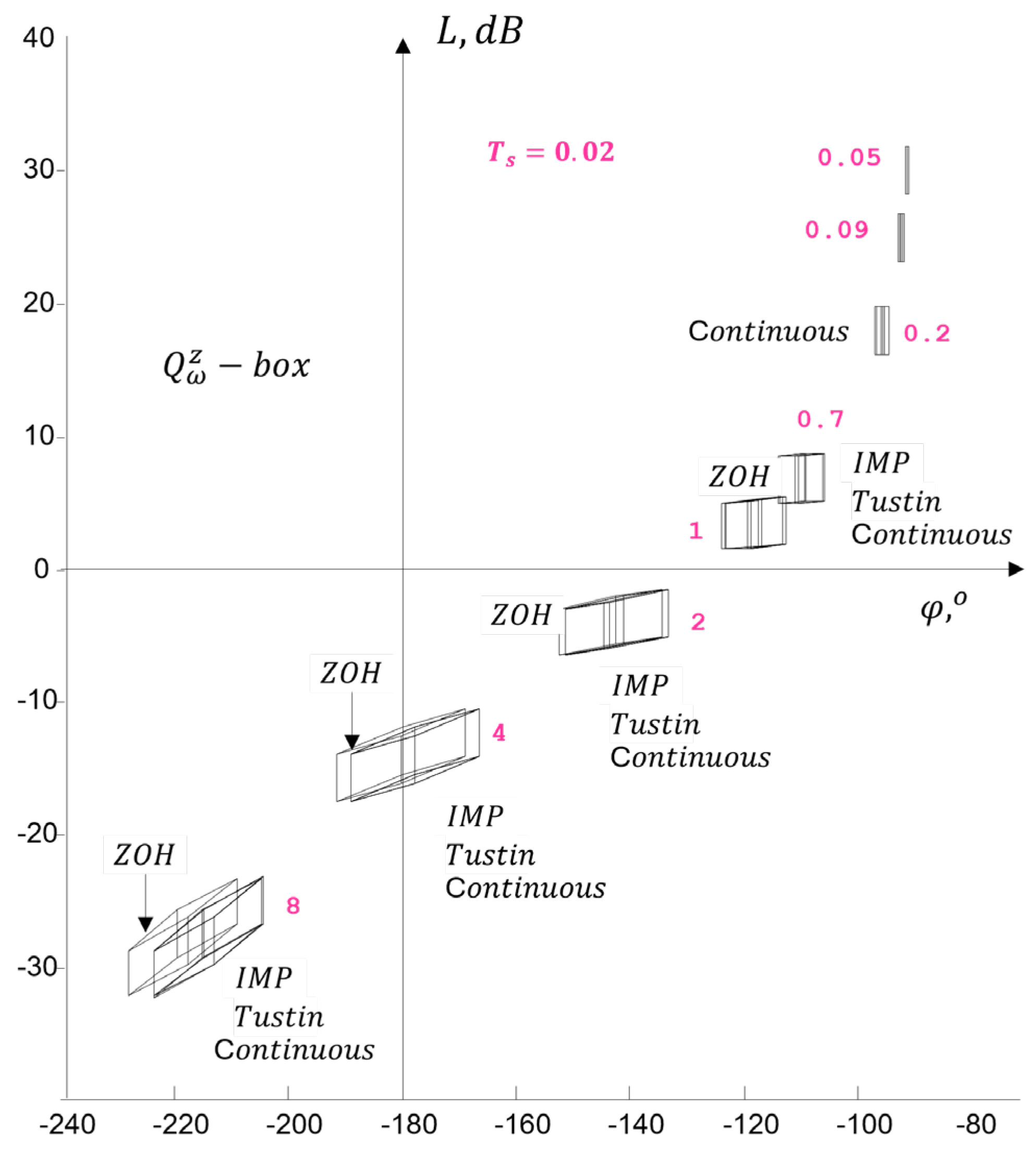

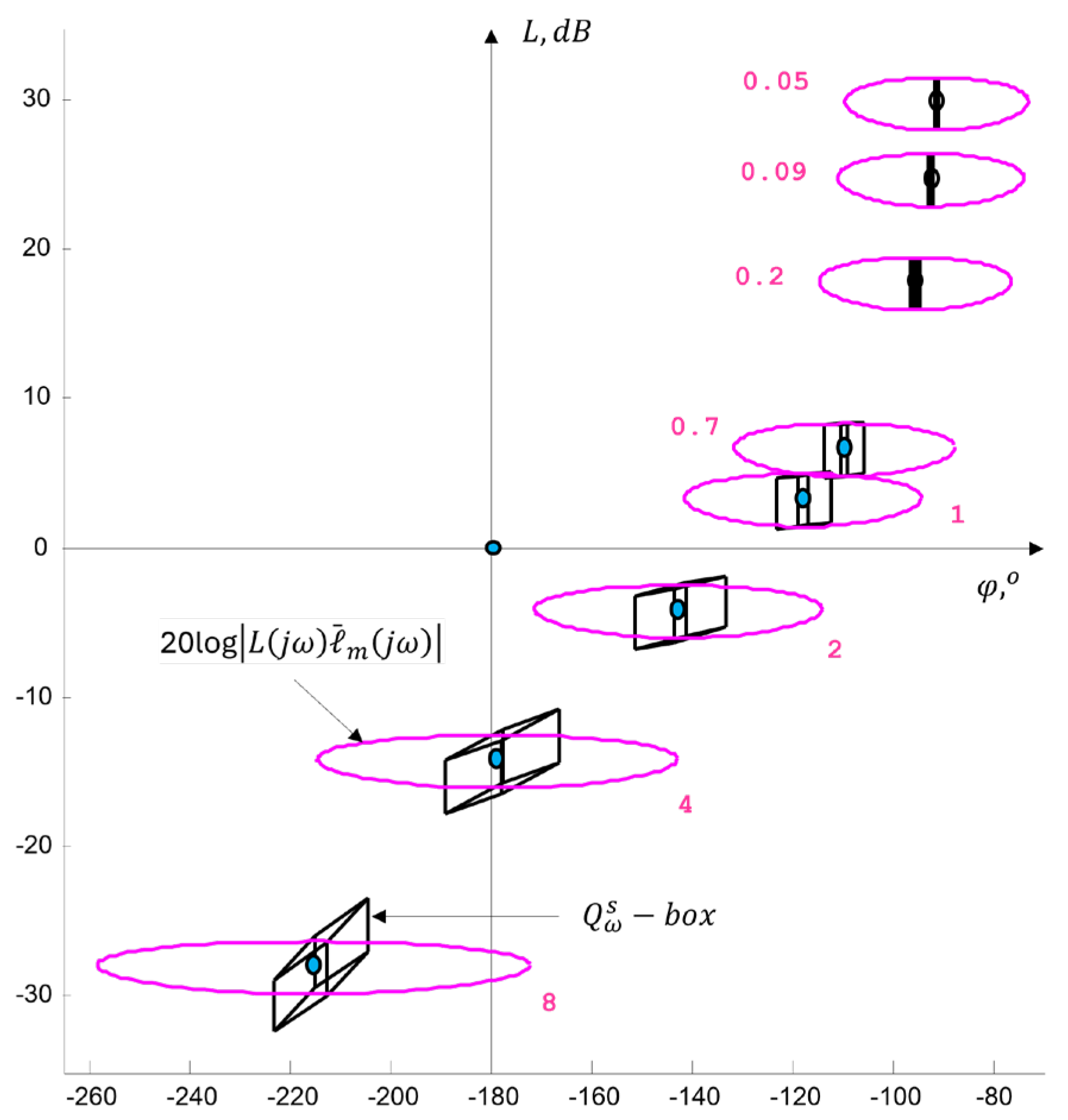

4.4. Generation in a Frequency Domain Design Template

4.4.1. Numerical Example

- Discussion

4.4.2. Robustness in the Frequency Domain

5. Conclusions

Appendix A

| 0.10 | 3.00 | 0.20 | 2.9021 | 3.0980 | 1.0010 | 0.0010 | 1.202 | 1.201 | |

| 0.10 | 3.00 | 0.50 | 2.9138 | 3.0870 | 1.0006 | 0.0006 | 1.201 | 1.201 | |

| 0.10 | 3.00 | 0.90 | 2.9578 | 3.0449 | 0.9993 | 0.0007 | 1.200 | 1.199 | |

| 0.10 | 5.00 | 0.20 | 4.9021 | 5.0980 | 1.0004 | 0.0004 | 1.201 | 1.200 | |

| 0.10 | 5.00 | 0.50 | 4.9137 | 5.0868 | 1.0002 | 0.0002 | 1.200 | 1.200 | |

| 0.10 | 5.00 | 0.90 | 4.9572 | 5.0444 | 0.9998 | 0.0002 | 1.200 | 1.200 | |

| 0.10 | 7.00 | 0.20 | 6.9020 | 7.0980 | 1.0002 | 0.0002 | 1.200 | 1.200 | |

| 0.10 | 7.00 | 0.50 | 6.9136 | 7.0868 | 1.0001 | 0.0001 | 1.200 | 1.200 | |

| 0.10 | 7.00 | 0.90 | 6.9570 | 7.0442 | 0.9999 | 0.0001 | 1.200 | 1.200 | |

| 3.83 | 3.00 | 0.20 | 1.0697 | 6.7909 | 1.2389 | 0.2389 | 1.606 | 1.487 | |

| 3.83 | 3.00 | 0.50 | 1.9379 | 6.5959 | 0.7041 | 0.2959 | 0.993 | 0.845 | |

| 3.83 | 3.00 | 0.90 | 3.6915 | 5.7995 | 0.4204 | 0.5796 | 0.794 | 0.504 | |

| 3.83 | 5.00 | 0.20 | 1.4675 | 8.7811 | 1.9401 | 0.9401 | 2.798 | 2.328 | |

| 3.83 | 5.00 | 0.50 | 2.5505 | 8.5297 | 1.1491 | 0.1491 | 1.454 | 1.379 | |

| 3.83 | 5.00 | 0.90 | 4.7914 | 7.5036 | 0.6954 | 0.3046 | 0.987 | 0.834 | |

| 3.83 | 7.00 | 0.20 | 3.3410 | 10.7749 | 1.3611 | 0.3611 | 1.814 | 1.633 | |

| 3.83 | 7.00 | 0.50 | 4.1539 | 10.4884 | 1.1247 | 0.1247 | 1.412 | 1.350 | |

| 3.83 | 7.00 | 0.90 | 6.3473 | 9.3259 | 0.8278 | 0.1722 | 1.079 | 0.993 | |

| 7.55 | 3.00 | 0.20 | 4.6495 | 10.5065 | 0.1842 | 0.8158 | 0.629 | 0.221 | |

| 7.55 | 3.00 | 0.50 | 5.1741 | 10.2583 | 0.1696 | 0.8304 | 0.619 | 0.203 | |

| 7.55 | 3.00 | 0.90 | 6.8012 | 9.2600 | 0.1429 | 0.8571 | 0.600 | 0.171 | |

| 7.55 | 5.00 | 0.20 | 2.8334 | 12.4891 | 0.7065 | 0.2935 | 0.995 | 0.848 | |

| 7.55 | 5.00 | 0.50 | 4.0765 | 12.1403 | 0.5052 | 0.4948 | 0.854 | 0.606 | |

| 7.55 | 5.00 | 0.90 | 7.0066 | 10.7197 | 0.3328 | 0.6672 | 0.733 | 0.399 | |

| 7.55 | 7.00 | 0.20 | 1.5614 | 14.4764 | 2.1678 | 1.1678 | 3.185 | 2.601 | |

| 7.55 | 7.00 | 0.50 | 3.8031 | 14.0549 | 0.9167 | 0.0833 | 1.142 | 1.100 | |

| 7.55 | 7.00 | 0.90 | 7.7414 | 12.3319 | 0.5133 | 0.4867 | 0.859 | 0.616 | |

| 11.28 | 3.00 | 0.20 | 8.3572 | 14.2270 | 0.0757 | 0.9243 | 0.553 | 0.091 | |

| 11.28 | 3.00 | 0.50 | 8.8056 | 13.9539 | 0.0732 | 0.9268 | 0.551 | 0.088 | |

| 11.28 | 3.00 | 0.90 | 10.326 | 12.8691 | 0.0677 | 0.9323 | 0.547 | 0.081 | |

| 11.28 | 5.00 | 0.20 | 6.4540 | 16.2049 | 0.2390 | 0.7610 | 0.667 | 0.287 | |

| 11.28 | 5.00 | 0.50 | 7.3811 | 15.8041 | 0.2143 | 0.7857 | 0.650 | 0.257 | |

| 11.28 | 5.00 | 0.90 | 10.147 | 14.1870 | 0.1736 | 0.8264 | 0.622 | 0.208 | |

| 11.28 | 7.00 | 0.20 | 4.6330 | 18.1875 | 0.5815 | 0.4185 | 0.907 | 0.698 | |

| 11.28 | 7.00 | 0.50 | 6.2788 | 17.6869 | 0.4412 | 0.5588 | 0.809 | 0.529 | |

| 11.28 | 7.00 | 0.90 | 10.359 | 15.6503 | 0.3022 | 0.6978 | 0.712 | 0.363 | |

| 15.00 | 3.00 | 0.20 | 12.075 | 17.9494 | 0.0415 | 0.9585 | 0.529 | 0.050 | |

| 15.00 | 3.00 | 0.50 | 12.492 | 17.6619 | 0.0408 | 0.9592 | 0.529 | 0.049 | |

| 15.00 | 3.00 | 0.90 | 13.956 | 16.5297 | 0.0390 | 0.9610 | 0.527 | 0.047 | |

| 15.00 | 5.00 | 0.20 | 10.148 | 20.0351 | 0.1211 | 0.8789 | 0.690 | 0.325 | |

| 15.00 | 5.00 | 0.50 | 10.991 | 19.6020 | 0.1059 | 0.8941 | 0.667 | 0.287 | |

| 15.00 | 5.00 | 0.90 | 13.610 | 17.7170 | 0.0847 | 0.9153 | 0.573 | 0.124 | |

| 15.00 | 7.00 | 0.20 | 8.2194 | 22.0674 | 0.2840 | 0.7160 | 0.690 | 0.325 | |

| 15.00 | 7.00 | 0.50 | 9.7930 | 21.5540 | 0.2106 | 0.7894 | 0.582 | 0.140 | |

| 15.00 | 7.00 | 0.90 | 13.932 | 19.3397 | 0.1433 | 0.8567 | 0.633 | 0.228 |

| Method | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.02 | 0.341 | 0.682 | 1.674 | 2.511 | |

| 0.02 | 0.341 | 0.682 | 1.674 | 2.511 | |

| 0.02 | 0.341 | 0.681 | 1.674 | 2.511 | |

| 0.05 | 0.341 | 0.682 | 1.674 | 2.511 | |

| 0.05 | 0.341 | 0.682 | 1.674 | 2.511 | |

| 0.05 | 0.4 | 0.681 | 1.674 | 2.510 | |

| 0.1 | 0.341 | 0.682 | 1.674 | 2.511 | |

| 0.1 | 0.341 | 0.682 | 1.674 | 2.511 | |

| 0.1 | 0.339 | 0.679 | 1.672 | 2.505 | |

| 0.2 | 0.341 | 0.682 | 1.674 | 2.511 | |

| 0.2 | 0.341 | 0.682 | 1.674 | 2.511 | |

| 0.2 | 0.333 | 0.671 | 1.666 | 2.484 | |

| 0.5 | 0.341 | 0.682 | 1.674 | 2.511 | |

| 0.5 | 0.341 | 0.682 | 1.674 | 2.511 | |

| 0.5 | 0.298 | 0.614 | 1.623 | 2.334 | |

| 0.7 | 0.341 | 0.682 | 1.674 | 2.511 | |

| 0.7 | 0.341 | 0.682 | 1.674 | 2.511 | |

| 0.7 | 0.267 | 0.554 | 1.571 | 2.173 |

References

- Horowitz, I. M. (1992). Quantitative Feedback Design Theory: Fundamentals and Applications. IEEE Press.

- Goodwin, G. C., Graebe, S. F., & Salgado, M. E. (2001). Control System Design. Prentice Hall.

- M. Panahi, G. M. Porta, M. Riva, и A. Guadagnini, “Modelling parametric uncertainty in PDEs models via Physics-Informed Neural Networks,” Advances in Water Resources, vol. 195, art. no. 104870, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K., Doyle, J. C., & Glover, K. (1996). Robust and Optimal Control. Prentice Hall.

- Tredinnick, J., Zampieri, S., & Rantzer, A. (2010). Sampling-Period Influence in Performance and Stability in Sampled-Data Control Systems. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 55(10), 2321–2334.

- Ádám, D., Dadvandipour, M., & Futás, J. (2009). Influence of discretization method on the digital control system performance. International Journal of Control, 82(5), 853–865.

- Ogata, K. (2021). Modern Control Engineering (5th ed.). Pearson.

- Golnaraghi, F., & Kuo, B. C. (2017). Automatic Control Systems (10th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Richard C. Dorf, Robert H. Bishop, Modern Control Systems, 14th edition, Published by Pearson (January 14th, 2021) - Copyright © 2022.

- Ackerman, J. in co-operation A. Barlett, D. Kaesbauer, W. Sienel, R. Steinhauser, Robust Control – Systems with Uncertain Parameters, L., Springer-Verlag, 1993.

- Sanchez-Pena, R., M. Sznaier, Robust Systems – Theory and Applications, Jonh Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1998.

- Barmish, B. R. Tempo, The Robust Root Locus, International Federation of Automatic Control, Automatica, vol. 26, Number 2, pp 283-292, l, 1990.

- Henrion, D., Šebek, M., & Kučera, V. (2005). Robust pole placement for second-order systems: An LMI approach. Kybernetika, 41(1), 1–14.

- Garcia-Sanz, M., C. Houpis, Wind Energy Systems, Control Engineering Design, CRC Press, 2012.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L. Control Strategy and Corresponding Parameter Analysis of a Virtual Synchronous Generator. Electronics 2022, 11(18), 2806. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Li, J. Stable PIR Controller Design Using Stability Boundary Locus. Processes 2023, 13(5), 1535. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, H. Small-Signal Stability Analysis of DC Microgrids Based on Root Locus Method. Energies 2023, 18(10), 2467. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A., Dolai, S. K., & Sarkar, P. (2023). A unified direct approach for digital realization of fractional order operator in delta domain. Facta Universitatis, Series: Electronics and Energetics, 35(3), 313–331. [CrossRef]

- Baños, A., Salt, J., & Casanova, V. (2020). A QFT approach to robust dual-rate control systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.03718. https://arxiv.org/abs/2002.03718.

- Dincel, E., & Bhattacharyya, S. P. (2021). Adaptive-Robust Stabilization of Interval Control System Quality on a Base of Dominant Poles Method. Automation and Remote Control, 82(10), 1903–1915. [CrossRef]

- Nesenchuk, A. A. (2010). The root-locus method of synthesis of stable polynomials by adjustment of all coefficients. Automation and Remote Control, 71(8), 1515–1525. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S., & Ohnishi, K. (2019). Robust stability for uncertain sampled-data systems with discrete disturbance observers. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.08722. https://arxiv.org/abs/1901.08722.

- Sariyildiz, E., & Ohnishi, K. (2021). A guide to design disturbance observer-based motion control systems in discrete-time domain. IEEE Access, 9, 32842–32860. [CrossRef]

- Biannic, J.-M., Roos, C., & Cumer, C. (2024). LFT modelling and μ-based robust performance analysis of hybrid multi-rate control systems. IFAC-PapersOnLine. (2024).

- Zhang, X., Kamgarpour, M., Georghiou, A., Goulart, P., & Lygeros, J. (2015). Robust optimal control with adjustable uncertainty sets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.04700. https://arxiv.org/abs/1511.04700.

- Arceo, V. M., Arceo, R. P., & Cervantes, E. F. (2022). Robust Control for Uncertain Systems: A Unified Approach. Mathematics, 10(4), 583. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, A. C., Hollot, C. V., & Huang, L. (1992). Root locations of polynomials with parametric uncertainty. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 37(1), 127–131.

- K. Noury and B. Yang, "A Pseudo S-Plane Mapping of Z-Plane Root Locus," in Proceedings of the ASME 2020 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition (IMECE2020), Portland, OR, USA, Nov. 15–19, 2020, Paper No. IMECE2020-23096.

- N. Alla, ‘Investigation and Synthesis of Robust Polynomials in Uncertainty on the Basis of the Root Locus Theory’, Polynomials - Theory and Application. IntechOpen, May 02, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Nesenchuk, V. I. (2010). The root-locus method of synthesis of stable polynomials by adjustment of all coefficients. Автoматизация и дистанциoннo управление, 71(8), 1389–1397. [CrossRef]

- Arceo, M. I., Lee, T. H., & Kim, J. H. (2022). On robust stability for Hurwitz polynomials via recurrence relations and linear combinations of orthogonal polynomials. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 427, 127004. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, A. C., Hollot, C. V., & Huang, L. (1992). A structural approach to robust stability of polynomials. Systems & Control Letters, 19(3), 207–212. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., & Chen, Y. (2017). Robust stability of fractional order polynomials with complicated uncertainty structure. Fractional Calculus and Applied Analysis, 20(3), 649–672. [CrossRef]

- Dincel, A., & Bhattacharyya, S. P. (2021). Adaptive-robust stabilization of interval control system quality on a base of dominant poles method. Automation and Remote Control, 82(10), 1903–1915. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A., et al. (2013). Frequency-domain robust control toolbox. In 2013 IEEE 52nd Annual Conference on Decision and Control (CDC) (pp. xxx–xxx). [CrossRef]

- V. A. Karlova-Sergieva, Robust Performance Assessment of Control Systems with Root Contours Analysis, Cybernetics and Information Technologies, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 83–99, June 2025.

- Morari, M., & Zafiriou, E. (1989). Robust Process Control. Prentice Hall.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).