1. Introduction

Currently, the significant rise in carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions has become a pressing global concern due to the growing demand from the automotive sector (Palea & Santhia, 2022). This phenomenon can be attributed to the rapid increase in urbanisation and economic growth. The anticipated growth in transport demand is expected to lead to a corresponding rise in CO₂ emissions. In Malaysia, the transport sector accounted for 28 per cent of total CO₂ emissions, with 85 per cent of that coming from road transport (Husain et al., 2023). Hence, this has sparked a keen interest in exploring effective strategies to reduce the CO₂ emissions from this sector (Mohd Shafie & Mahmud, 2020).

In line with the Low Carbon Mobility Blueprint 2021-2030, Malaysia plans for EVs and hybrids to comprise a minimum of 15 per cent of the overall industry volume by 2030. Malaysia aims to establish 125,000 electric vehicle (EV) charging stations by 2030 under the National Electric Mobility Blueprint. Notwithstanding these initiatives, the adoption of EVs in Malaysia remains far behind those of nations like China, the United States, and Norway (Noor et al., 2021; Muzir et al., 2022). As per the statistics from the Road Transport Department Malaysia (JPJ), there are approximately 22,728 fully EVs registered in Malaysia as of April 2024 and the majority fuel type of registered automobiles in Malaysia is petrol, accounting for 88.3 per cent, followed by green diesel at 7.4 per cent and hybrid vehicles at 2.5 per cent (

https://malaysia.news.yahoo.com/ev-sales-increasing-malaysia-data-122918062.html). This signifies that the majority of car ownership in Malaysia remains focused on internal combustion engine-powered vehicles. Merely 1.2 per cent of consumers bought EVs, while the remaining 98.8 per cent have not.

As addressed by Muzir et al. (2022), Malaysians are promoting the EV as a way to lessen their reliance on fossil fuels and reduce carbon emissions from the transportation sector, especially in personal transportation. People recognise EVs as a viable sustainable solution for decarbonising personal transportation, given their ability to improve air quality and their availability as a green technology (Asadi et al., 2022; Gulzari et al., 2022). Thus, in the Malaysian market, public acceptance of EVs is crucial, as it ensures a push for their supply.

Past studies on consumer EV adoption have examined many factors influencing the adoption of EVs. Past studies have concentrated on different aspects of adoption and non-adoption behaviour (Ehsan et al., 2024; Kumar & Alok, 2020; Krishna, 2021). They have employed many variable ideas and examined diverse EVs across multiple regions globally. Such an approach has made the research fragmented and increasingly hard to know where important knowledge gaps lie and where contributions can be made in future research. Significant consumer acceptability of alternative fuel vehicles is a crucial prerequisite for assessing the feasibility of successful implementation (Kowalska-Pyzalska et al., 2022).

The success of EVs is primarily contingent upon consumer acceptance and adoption (Ehsan et al., 2024). Nonetheless, public acceptance of this novel eco-friendly vehicle remains inadequate, as consumers’ exhibit skepticism towards this technology due to their limited experience and knowledge. (Skippon et al., 2016). The present adoption of greener or cleaner transport methods is primarily encouraged by policies or incentives initiated by the government. (Qadir et al., 2024). There is limited research available that provides a comprehensive understanding of consumer acceptance from a social standpoint. Bajaj et al. (2020) addressed that consumers' consumption motive is multi-faceted, encompassing both situational and psychological elements. Therefore, to comprehend how consumers' decision-making processes are influenced by these aspects, it is imperative to examine these multifaceted elements through established behavioural theoretical models to elucidate their underlying relationships.

The existing literature on the adoption of EVs primarily derives from two views. One viewpoint focuses on the characteristics, specifically the instrumental characteristics of EVs (Adepetu & Keshav, 2017; König et al., 2024; Knowles et al., 2012; Marczak & Droździel, 2021; Kim et al., 2017). The results demonstrate that instrumental attributes, including price, operational cost, comfort, performance, pollution level, driving range, charging time, and convenience, significantly influence consumers' attitudes and acceptance of EVs. The other research view examines EVs as innovations in green technology, innovative personality, green values and beliefs, environmental attitudes and responsibilities, moral norms, and other cognitive and psychological factors on consumers' intentions to adopt EVs (Adnan et al., 2018; Irfan & Ahmad, 2021; Junquera et al., 2016). Various research theories and models, including the Theory of Planned Behaviour, the Diffusion of Innovation Theory, the Values-Beliefs-Norms Theory, the Technology Acceptance Model, and the Norm Activation Model, are commonly used (Haustein & Jensen, 2018; Xia et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022; Ashraf Javid et al., 2021).

Marketing theory, particularly The Theory of Consumption Value (TCV), posits that consumers are inclined to make purchasing decisions only when products embody particular values and fulfil their needs (Xu et al., 2024). Nonetheless, to our knowledge, there is scant empirical study examining the influence of consumer value on the adoption of EVs. This absence creates a substantial disparity between theoretical and empirical studies aimed at promoting EVs. This study aims to address the identified gap by examining consumer behavioural intention of EV purchase through the comprehensive application of the TCV proposed by Sheth et al. (1991). The present study is to examine the influence of consumption values on attitudes and behavioural purchase intentions for EVs.

This study has multiple contributions. It was conducted from the standpoint of consumption value. Furthermore, we classify consumption values into five categories to assess their effects, which may enhance the accuracy and specificity of our findings. The subsequent sections of this work are structured as follows. Sections 2, Literature Review, and 3, Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses, examine the literature and present the conceptual framework and hypotheses.

Section 4 concentrates on the methodology.

Section 5 details the data analysis and outcomes.

Section 6 presents the conclusion of the research, highlighting its implications and limitations.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theory of Consumption Value (TCV)

Many academic studies, especially in the field of marketing, recognise consumption values as a critical component of the consumer's decision-making process (Liu et al., 2021; Talwar et al., 2020). Consumption values indicate the extent to which consumers recognise the importance of the attributes associated with a product or service (Wang, 2020). TCVs function as a theoretical framework that establishes consumer consumption values as the core basis for explaining consumer purchase behaviours. TCVs provide a critical framework for understanding the reasons behind consumer purchasing decisions, based on their perceived value. The TCVs suggest that five consumer consumption value perceptions influence consumer behaviour, namely; functional, conditional, social, emotional, and epistemic/ novelty values. The five perceptions of consumption value affect consumer purchasing patterns in different ways, depending on the context. The five perspectives on consumption value are independent of one another. The TCVs have been used to clarify behavioural outcomes, including purchase intention (Aravindan et al., 2023; Shoukat et al., 2021); choice behaviour (Tanrikulu, 2021; Bahoo et al., 2024); consumer trust (Chakraborty et al., 2022); and loyalty (Zhang et al., 2023).

Sheth et al. (1991) posited that five values govern consumer behaviour regarding intention: functional, social, emotional, conditional, and epistemic. These values suggest that individuals assign varying significance to different products, which subsequently affects their purchasing decisions (Lee, 2021). Multiple consumption values determine consumer choice, according to this theory, which integrates components from other consumer behaviour models (Tanrikulu, 2021). This theory also elucidates the reasons consumers select specific products or prefer one product over another (Hur, 2020). This idea relies on the manner in which consumers are informed about a product or service, which intrinsically and extrinsically influences their consumption decisions (Ray et al., 2024; Tanrikulu, 2021).

Rana and Solaiman (2023) demonstrated that the TCV, encompassing functional, symbolic, emotional, epistemic, social, and conditional dimensions, influenced consumers' engagement in green purchasing behaviour. TCV has been utilised in various investigations concerning purchasing intention. Amoah et al. (2016) identified the correlations among value, satisfaction, and behavioural intention regarding guesthouses in Ghana. Chakraborty and Paul (2023) conducted research to identify the determinants of healthcare app users' behavioural intention using TCV, revealing that all consumption values, except social values, influence brand love for healthcare apps, with emotional value being the most significant factor, followed by conditional value. Amin and Tarun (2021) also investigated the influence of consumption factors, including functional, emotional, and social value, on green buying intention. Their research revealed that emotional value substantially impacts green buy intention, whereas the other two dimensions of consumption values, namely functional and social value, exert negligible effects on customers' green purchase intention. Consequently, elucidating individual consumption behaviour is more relevant when employing the TCV (Kaur et al., 2021).

In summary, TCV is a cohesive model that integrates variables from various consumer values, including the implications of consumer choice. The word consumption value refers to the extent to which a consumer's needs are met, derived from a comprehensive evaluation of the customer's overall satisfaction with a product (Uzir et al., 2020).

2.1.1. Functional Value

Functional value refers to consumers' assessment of a product's price and quality. It also signifies the perceived utility that arises from an alternative's capacity for functional, utilitarian, or physical performance. An alternative attains functional value by the acquisition of prominent functional, utilitarian, or physical attributes. Chaerudin and Syafarudin (2021) established that customers evaluated price and quality prior to product acquisition. Price may represent the most prominent functional value (Han & Kim, 2020). In the product selection process, customers' awareness of price greatly impacts their purchasing decisions about green products (Wijekoon & Sabri, 2021).

Additionally, functional value is measured by consumers’ perception of various product performances such as durability, permanence, dependability, reliability, price, and quality. It is assessed as the primary factor influencing consumers' choice behaviour in the context of product purchase decisions. (Amin & Tarun, 2021; Ahmad & Zhang, 2020). Numerous empirical studies have demonstrated that functional value is a significant determinant of purchase behaviour. (Akkaya, 2021; Chakraborty & Paul, 2023; Dangelico et al., 2021). Thus, it is hypothesised that:

H1: Functional value positively influences consumers’ behavioural intentions to purchase EV.

2.1.2. Symbolic Value

Symbolic or social value pertains to the perceived utility derived from affiliation with one or more social groups. Social pressure is a significant determinant of consumer decision-making. (Li et al., 2020; Mansori et al., 2020). However, some research indicates that personal factors like attitudes and personality traits have a greater influence on consumers' decisions than social norms or pressures (Tajeddini et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). A sense of social duty motivates environmental actions (Pan et al., 2022). According to Neumann et al. (2020), consumers would become more motivated if others acknowledged or praised their environmental efforts. The symbolic value of green products is defined as the perceived net utility derived from their use, influenced by the perception of social pressure or the prestige associated with engaging in environmental conservation (Tandon et al., 2021). Social pressure, comparisons, and peer opinions are primary determinants in decision-making (Hoek et al., 2021; Tajeddini et al., 2021). Dangi et al. (2020) indicated a significant impact of social groupings and the aspiration for social recognition on the buying behaviour of consumers exhibiting a preference for green credentials. Peers, family, self-identity, and various social aspects influenced consumers' purchasing decisions, according to prior research by AlShurman et al. (2021) and Baker et al. (2022). Based on this, the present study hypothesised that:

H2: Symbolic value positively influences consumers’ behavioral intentions to purchase EVs.

2.1.3. Emotional Value

The emotional value reflects how consumers feel about eco-friendly products. A product's or service's perceived utility elicits emotions or affective states. This value influences the behaviour of environmentally conscious consumers (Kautish & Sharma, 2021). There is a notable shift in consumer behaviour toward more sustainable practices as awareness and concern for environmental protection increase (Suphasomboon & Vassanadumrongdee, 2022). In addition, studies found that individuals with higher New Environment Paradigm (NEP) scores were more inclined to engage in pro-environmental behaviour (Wang et al., 2020; Yue et al., 2020). The emotions of consumers regarding environmental protection as well as individual accountability will influence their decisions to make green purchases (Shimul & Cheah, 2023; Zhang & Dong, 2020). Sharma et al. (2023) indicated that emotional values significantly influenced individuals' correlated behaviour in various situations, with aggressive behaviour appearing to dominate their involvement in ecological and environmental activities. Previous findings indicated that different emotions, especially those related to personal safety (Veale et al., 2023; Wang & Liau, 2021), guilt (Gallego-Alberto et al., 2017), and generativity (Klein et al., 2016), had a direct impact on consumer behaviour and could steer consumers toward sustainable purchasing decisions. As such, it was hypothesised that:

H3: Emotional value positively affects consumers’ behavioural intentions to purchase EVs.

2.1.4. Novelty Value

Novelty value encompasses the desire for information or inquisitiveness regarding a product (Zhou et al., 2017). In this study, novelty value was used in place of epistemic value based on the argument by Sheth et al. (1991) that there is an overlap between novelty and epistemic value in practical applications, as both share the same definition. They further noted that epistemic value is derived from an alternative's ability to stimulate curiosity and offer novel or enlightening experiences. Khan and Mohsin (2017) revealed that the novelty value of green products had a significantly positive impact on consumers’ choice behaviour. A similar outcome was gained in various contexts like mobile applications (Karjaluoto et al., 2019) and adventure tourism (Williams et al., 2017; Hettiarachchi & Lakmal, 2018).

Novelty values, such as product characteristics and designs, significantly influence consumer behaviour regarding green products (Zhou et al., 2017). Consumers purchase products due to brand familiarity, attention to new offerings, or a desire to acquire knowledge about them. The pursuit of novelty is associated with the development of problem-solving skills (Hardy III et al., 2019). Consumers' inclination to satisfy their desire for information regarding a product's features and innovation positively influences their purchasing behaviour toward green products (Choi & Johnson, 2019; Zhang et al., 2020). Novelty value arises when an individual engages with new products or services, experiences boredom with existing options, seeks variety, or aims to satisfy curiosity through novel experiences (Qasim et al., 2019). Moreover, novelty value emphasises the innovative aspects of a product, highlighting its novelty and distinctiveness; thereby, cultivating curiosity can enhance this value. Evidence suggests that novelty values influence the behaviour of green consumers (Kaur et al., 2018). Hence, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H4: Novelty value positively affects consumers’ behavioural intentions to purchase EVs.

2.1.5. Conditional Value

According to Sheth et al. (1991), conditional value refers to the value a product or service gains in specific circumstances or contexts. It highlights the significance of situation or circumstance in consumers’ product choices. A product or service gains this value because the existence of physical or social contingencies raises the functional or social value (Sheth et al., 1991). Moreover, when the value is closely linked to the usage of the product or service in particular contexts, the conditional value rises. Research indicates that variations in consumer situational variables can influence the adoption of green products (Khan & Mohsin, 2017; Woo & Kim, 2019). Candan and Yildirim (2013) identified 'time, place, and context' as the fundamental determinants for conditional factors. Previous empirical studies have demonstrated that conditional value influences green purchase behaviour (Sharma & Foropon, 2019; Liu et al., 2020).

The conditional value of green products can be defined as the net utility gained from consuming them compared to traditional alternatives, based on the consumer's perceived readiness to obtain personal benefits, such as discounts, or their perceptions of situational variables that influence their consumption (Woo & Kim, 2019). Diverse infrastructural and contextual factors influence pro-environmental behaviour, acting as either facilitators or inhibitors (Nguyen et al., 2019; Nuttavuthisit & Thøgersen, 2017). Examples of these conditional factors include monetary elements such as government incentives or subsidies (Sun et al., 2020), promotional discounts (Büyükdağ et al., 2020), regulations and laws (Pan et al., 2023), and physical accessibility to green products (Weissmann & Hock, 2022). As such, studies have found that factors such as cash rebates and government subsidies may impact green purchase intention and serve as a rationale for acquiring EVs (Lu et al., 2022; Williams & Pallonetti, 2023). Thus, we hypothesised that:

H5: Conditional value positively affects consumers’ behavioural intentions to purchase EVs.

2.1.6. The Relationship Between the Dimension of Consumption Values and Consumers’ Attitudes Toward EVs

Prior investigations have shown that shared consumption values contribute to the development of attitudes and their influence on consumer behaviour. Various scholars agree that consumer perception of a product's functional value significantly shapes consumption patterns and influences consumer attitudes (Han et al., 2017; Choe & Kim, 2018). People with positive perceptions of functional value, such as quality and price, tend to cultivate more favourable attitudes and behaviours than those who consider alternative options (Diallo & Seck, 2018; Pan et al., 2024). Wahid et al. (2017) found that functional values significantly influence attitudes towards drinking water. This explanation suggests that consumer perceptions of functional value significantly shape their attitudes in relation to EVs.

Symbolic or social values significantly influence consumer behaviour by shaping consumption patterns in various ways. People frequently adjust their behaviours in response to the dominant social values around them, resulting in an increased attraction to products or brands that boost their acceptance and visibility among their peers (Tajeddini et al., 2021). People form distinct notions regarding how they think their social environment should view them (Kosse et al., 2020). This understanding affects how consumers behave and evaluate particular products (Paço & Lavrador, 2017). Varghese and Jana (2019) suggested that the social advantages consumers gain from a product arise from its association with particular social groups. Furthermore, the social benefits associated with a product can play a significant role in improving consumers' self-image. Moreover, several scholars have suggested that social values influence perceptions related to environmentally friendly purchasing behaviours (Ives & Kidwell, 2019; Woo & Kim, 2019; Yusliza et al., 2017).

As mentioned earlier, emotional value refers to the way consumers understand the emotional advantages derived from utilising a product (Sheth et al., 1991). The importance of EV is especially evident in influencing how consumers evaluate a product. A greater probability of a product providing emotional satisfaction results in a more positive assessment by the consumer (Sukhu et al., 2019). Trivedi and Teichert (2019) found that consumers typically prefer and experience positive emotional reactions to products that offer emotional advantages, such as relaxation, joy, fun, excitement, and enjoyment.

The idea of novelty value relates to the fundamental motivation for curiosity, new experiences, and comprehension linked to a product (Sheth et al., 1991). The importance of novelty value is crucial, especially in influencing consumer evaluations of products. In particular contexts, evaluations conducted by consumers often depend on their views about how well a product can provide information, innovation, and functionalities to satisfy their curiosity (Talukdar & Yu, 2024). In evaluating a new product, individuals frequently make comparisons with current alternatives. To gain acceptance, new products must exhibit a markedly greater degree of novelty in comparison to existing offerings (Albaity & Melhem, 2017). Chi (2018) suggested that informational factors, novelty, and curiosity are crucial in influencing product acceptance. Consumers generally embrace a product more readily than alternatives when it satisfies their craving for novelty (Lee et al., 2017; Leclercq-Machado et al., 2022).

The conditional value examines how consumers understand the benefits of their consumption behaviours in particular situations or contexts (Sheth et al., 1991). From this viewpoint, changes to these conditions will result in changes in consumer behaviour (Woo & Kim, 2019). Sangroya and Nayak (2017) noted that various conditional factors often influence consumer consumption patterns, emphasising the necessity for marketers to integrate multiple conditions, such as reduced lead times, to encourage consumer consumption behaviour. Furthermore, a variety of studies have shown that conditional value plays a crucial role in shaping consumer evaluations, both favourable and unfavourable, concerning a product (Arghashi & Yuksel, 2022; Chawla & Joshi, 2019; Woo & Kim, 2019).

Based on the above explanations, we suspect that all the dimensions of consumption value (functional, symbolic, emotional, novelty and conditional) are also drivers of attitudes towards EVs. Therefore, it is hypothesised:

H6: Functional value positively affects consumers’ attitudes toward EVs.

H7: Symbolic value positively affects consumers’ attitudes toward EVs.

H8: Emotional value positively affects consumers’ attitudes toward EVs.

H9: Novelty value positively affects consumers’ attitudes toward EVs.

H10: Conditional value positively affects consumers’ attitudes toward EVs.

2.2. The Influence of Consumers’ Attitudes Toward EVs on Behavioural Intentions to Purchase EVs

Studies in green consumer psychology consistently emphasise the significance of attitude as a vital precursor to both behavioural intention and actual behaviour (Liau et al., 2020; Mazhar et al., 2022). Consumers acquire a tendency to consistently react positively or negatively to an object (Ajzen et al., 2018). Additionally, this behavioural phenomenon highlights consumers' preferences and dislikes, particularly in relation to their purchasing decisions regarding products or services (Hill, 2017). As a result, we can categorise attitudes into general and specific categories (Verma et al., 2019). The general attitude pertains to the inclination to engage in behaviours associated with a category of attitude objects, while the specific attitude serves as a robust predictor of behaviour related to a particular attitude object (Choi & Johnson, 2019). In the field of environmental consumer studies, it refers to the beliefs or emotions that influence the decision to buy eco-friendly products like EVs, as well as the ecological effects of these specific behaviours (Lashari et al., 2021). Nonetheless, the perspective on eco-friendly products, such as EVs, differs from the overall environmental mind-set, influencing the behavioural aspects of green purchasing decisions aimed at fostering positive environmental sustainability (Beck et al., 2017).

Numerous investigations have demonstrated that one's attitude toward eco-friendly products and their environmental mind-sets are significant indicators of green purchasing behaviour (Mallick et al., 2024; Paço & Lavrador, 2017; Marcinkowski & Reid, 2019). Tamar et al. (2021) found that the environmental attitude was the primary factor influencing green purchase behaviour. Furthermore, Jakučionytė-Skodienė et al. (2020) determined that attitude served as the most significant predictor of intention and behaviour associated with energy-saving behaviour. In a similar vein, Judge et al. (2019) found that the attitude toward green and sustainable homes positively influenced behavioural intention. Jung et al. (2020) concluded that attitude plays a vital role in shaping an individual’s intentions and actual behaviour. Therefore, the subsequent hypothesis was formulated:

H11: Consumers’ attitudes toward EVs are positively associated with behavioural intentions to purchase EVs.

2.3. Mediating Effect of Consumers’ Attitudes Toward EVs on the Relationship Between Consumption Values and Behavioural Intentions to Purchase EVs

Attitude reflects an individual's overall evaluation of behaviour. Many past studies found that attitude acts as a critical bridge in the relationship between consumption values and purchase intentions (Liu et al., 2021; Rachman & Amarullah, 2024). Salehzadeh and Pool (2000) discovered a connection between values, attitude, and purchase intention. Indriani et al. (2019) and Ogiemwonyi et al. (2023) examined the role of the mediator in the connection between environmental factors and the intention to make green purchases. The findings indicated that attitude played a crucial role as a mediator in that relationship. Furthermore, empirical findings by Zheng et al. (2020) demonstrated the influence of attitude on the green purchasing behaviour of consumers and the mediating role of attitude on the relationship between perceived environmental responsibility and green purchasing behaviour. Product attitude has a significant mediating effect between ethnocentrism and purchase intention. Wu et al. (2010) conducted a study that exemplifies the role of attitude in mediating the relationship between product knowledge and ethnocentrism in relation to purchasing intention. Subsequently, Noor and Wen (2016) demonstrated that functional and conditional values, along with consumers' attitudes, exhibited a positive and significant relationship with consumers' purchase intentions. In contrast, emotional value affected consumers’ purchase intentions through their attitudes. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H12: Consumers’ attitudes toward EVs mediate the relationship between functional value and behavioural intentions to purchase EVs.

H13: Consumers’ attitudes toward EVs mediate the relationship between symbolic value and behavioural intentions to purchase EVs.

H14: Consumers’ attitudes toward EVs mediate the relationship between emotional value and behavioural intentions to purchase EVs.

H15: Consumers’ attitudes toward EVs mediate the relationship between novelty value and behavioural intentions to purchase EVs.

H16: Consumers’ attitudes toward EVs mediate the relationship between conditional value and behavioural intentions to purchase EVs.

2.4. Moderating Effect of Infrastructure Readiness on the Relationship Between Attitude and Behavioural Intentions to Purchase EVs.

Some of the barriers to consumer adoption of EVs include restricted driving range and extended charging durations (Tsai et al., 2024; Husain et al., 2021). Therefore, the establishment of fast-charging infrastructure plays a crucial role in facilitating long-distance travel for EVs, which may be essential for enhancing the market adoption of EVs (Liu et al., 2021). Fischer et al. (2019) and Anand et al. (2020) offer evidence that charging demands or local refuelling primarily influence spatial distributions. However, it is important to note the significant variations that exist between EV charging infrastructure and petrol refuelling stations.

Additionally, Miele et al. (2020) suggested that alternative fuel vehicles appeared to compete with conventional vehicles, provided that the refuelling infrastructure is in place. Consequently, the preparedness of infrastructure plays a crucial role in enhancing market penetration and fostering public acceptance of EVs. Public charging stations and battery-exchange stations are widely acknowledged as practical options for charging electric vehicles outside of the home (Chen et al., 2025). Home charging solutions are essential, yet the economic justification for public rapid chargers remains inadequately understood (Ahmad et al., 2024).

Various strategies can be implemented to promote the adoption and market expansion of EVs, such as offering financial incentives for purchases and establishing charging infrastructure in urban areas that are easily accessible (Lanzini, 2024). Nevertheless, range anxiety, which denotes the concern that the vehicle might lack sufficient battery power to arrive at its desired location, has been recognised as a major barrier to the extensive acceptance of battery-electric vehicles (Pei et al., 2025). Range anxiety not only reduces the chances of individuals acquiring BEVs, but it also limits their societal benefits. Those who initially adopted EVs may find their usage restricted to short trips, leading to a lower annual mileage compared to those who do not experience range anxiety (Pevec et al., 2020). Higueras-Castillo et al. (2024) and Fang et al. (2023) have noted that the high price of EVs and the lack of necessary support services, like battery charging stations, can lead to doubt. In their study, Goel et al. (2023) examined EV adoption in India and discovered that EV infrastructure plays a moderating role in the relationship between financial attributes and EV adoption. Moreover, the findings indicate that the availability of charging infrastructure enhances trust, subsequently motivating and reassuring EV consumers. Therefore, we develop the following hypothesis based on the above discussion:

H17: Infrastructure readiness moderates the relationship between consumers’ attitudes toward EVs and behavioural intentions to purchase EVs.

2.5. Research Model Development

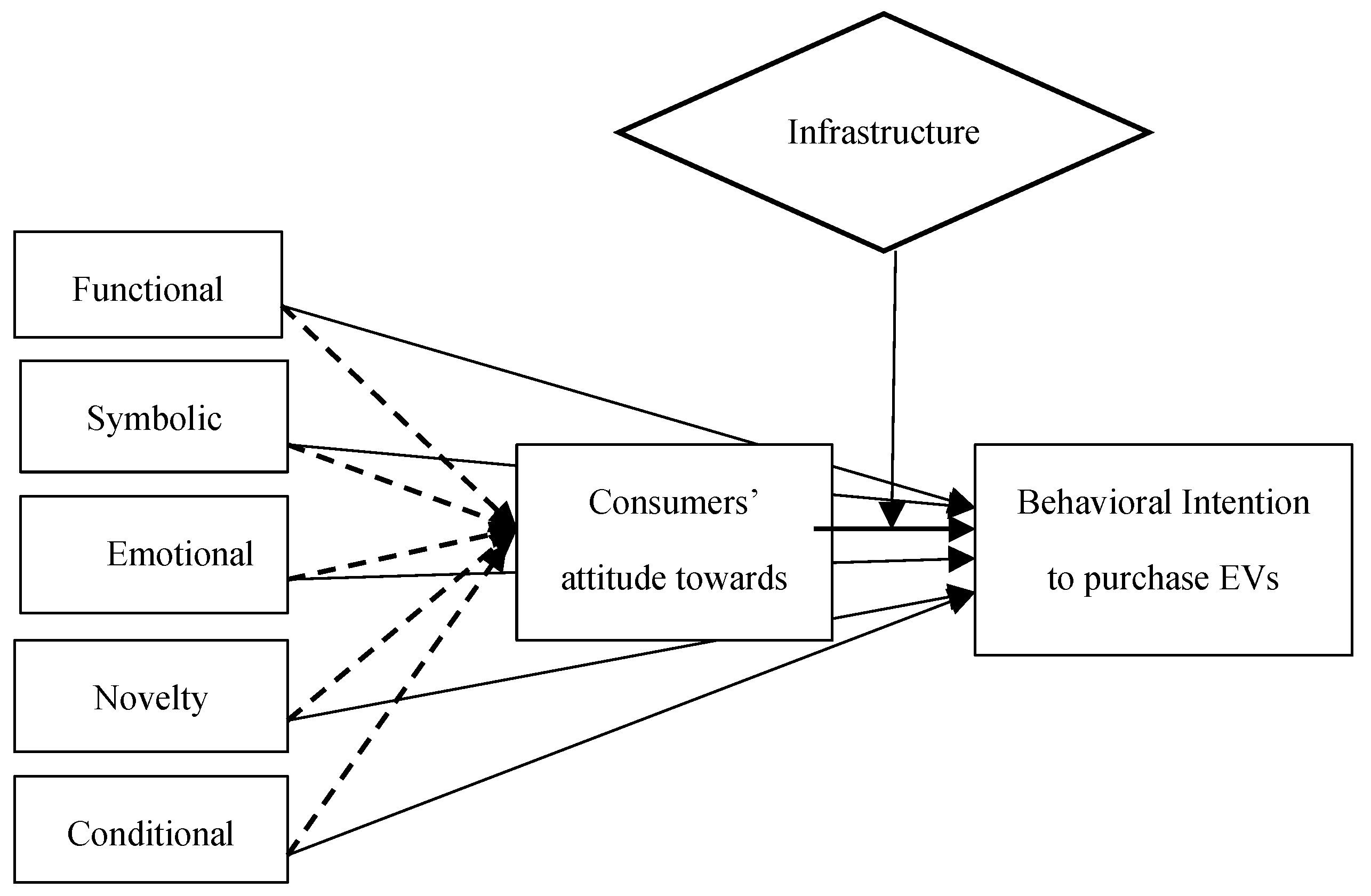

The relevant literature on well-known theory and past studies has been discussed to develop this study’s conceptual model. There are five direct relationships between consumption value dimensions and behavioural intention to purchase EVs namely; functional value, symbolic value, emotional value, novelty value, and conditional value. Meanwhile, consumers’ attitudes towards EVs are anticipated to have a direct relationship with the behavioural intention to purchase EVs and act as a mediating variable for the relationship between consumption value dimensions and the behavioural intention to purchase EVs. Besides, infrastructure readiness is postulated to influence the relationship between consumers’ attitudes towards EVs and their behavioural intention to purchase EVs, as shown in figure 1 below:

3. Methodology and Data Collection Procedure

This study employed a quantitative method and cross sectional research design in nature. A questionnaire was employed to gather data regarding the behavioural intentions of consumers in Klang Valley, Malaysia, towards purchasing EVs. The current research concentrated on Klang Valley because of its advanced transportation infrastructure and the presence of many charging stations, making it an appropriate location for examining EV adoption behaviour (Afroz et al., 2015; An et al., 2024). The current investigation focused on individuals aged 25 and older. The selection of consumers aged 25 years and older is based on the study's focus on the high-end product category. This demographic is appropriate, as they typically possess greater disposable income and require a vehicle for transportation. Moreover, most research to date concurs that younger people or people below the age of 45 are more prone to purchasing EVs (Coffman et al., 2017; Lin & Wu, 2018). This may be because younger people are more prone to trying new products and have a more favourable attitude towards change as well as a higher level of environmental consciousness; individuals place greater emphasis on factors such as car performance, value, quality, and risk when evaluating their car purchase decisions (Higueras-Castillo et al., 2024).

The instruments employed to assess the constructs in this study have been adapted from earlier research to ensure content validity. Six items were used to assess the behavioural intention to purchase EVs, adapted from the work of Kanchannapibul et al. (2014). Eleven items were used to assess consumers’ attitudes towards EVs, drawing from the works of Han et al. (2010), Hong et al. (2012), and Lee (2009). Five items were employed to assess infrastructure readiness, adapted from the work of Sang and Bekhet (2015). Ten items were used to assess functional value, adapted from Lin and Huang's (2012) work. A total of twelve items and eight items were utilised to assess symbolic value and emotional value adapted from the work of Teoh and Mohd Noor (2015). Novelty and conditional value are derived from the work of Lin and Huang (2012), comprising six and five items to assess the respective variables. All items are measured using five-point Likert scales. A pilot study was carried out using a convenience sample of 30 respondents who visited car showrooms in a small city in Malaysia. The reliability for the pilot study ranged from 0.741 to 0.949, which is adequate for the intended analysis (Pallant, 2020).

The sampling procedure utilised in this study involved proportionate stratified sampling, wherein the population was segmented into groups based on the major cities within the Klang Valley, namely; Kuala Lumpur, Ampang, Klang, Shah Alam, Subang Jaya, and Petaling Jaya. The minimum sample size recommended for five arrows directed at a single construct in PLS-SEM analysis is 228, as outlined in Cohen’s Rules of Thumb (Hair et al., 2017). This study used the intercept survey method to gather data. In the process of the intercept survey, trained interviewers adhered to a systematic sampling protocol, approaching individuals who visited car showrooms in the designated cities in Klang Valley areas and enquiring if anyone would be willing to take part in the survey. After obtaining consent, respondents were provided with a survey questionnaire. Consequently, a total of 300 questionnaires were distributed. The respondents were asked to complete and submit the questionnaire promptly.

The self-administered questionnaire was distributed at the showrooms of the top three EV brands in Malaysia. The questionnaire was distributed outside the showrooms, targeting individual consumers as they exited after consulting the sales representatives or sales administrators. The rationale for selecting individual consumers who visit the showroom lies in the increased likelihood that these individuals have a genuine intent to purchase an EV (Ye et al., 2021).

4. Results

A total of 300 questionnaires were distributed, and 283 were successfully returned. Nonetheless, merely 264 were deemed usable. Nineteen questionnaires were excluded due to incomplete responses from the respondents. Consequently, a usable response rate of 88 per cent has been attained. The demographic profile of the respondents for this study is presented in

Table 1. Out of 264 valid respondents, 147 are male, accounting for 56 per cent, while 117 are female, representing 44 per cent. The study's population includes consumers aged 25 and older, with the largest group of respondents falling within the 41 to 50-year range (45.5%), followed by those aged 31 to 40 years (25.4%), 25 to 30 years (15.5%), and those aged 51 years and above (13.6%). The majority of the respondents are married (77.3%). In terms of academic qualification, 89 respondents are bachelor’s degree holders (33.7%); 68 respondents are master’s degree holders (25.8%); 52 respondents are diploma holders (19.7%); 37 respondents are secondary certificate holders (14%); 11 respondents are doctorate holders (4.2%); and 7 respondents possess professional qualifications (2.7%). On respondents’ employment sector, most of them are from the private sector (74.2%) and the government sector (12.9%). Self-employed, retired or pensioners and others such as students comprised 9.10 per cent, 1.10 per cent and 2.70 per cent respectively.

To evaluate the hypotheses, partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was employed. PLS-SEM has been selected for various reasons. PLS's efficacy in studying the link between one or more dependent variables and one or more independent variables has been confirmed by many prior studies (Hair et al., 2019; Memon et al., 2021). In addition to that, PLS-SEM is a multivariate technique that allows for the concurrent assessment of multiple equations. The moderation results are computed using a two-stage approach in SmartPLS. This method utilises the latent variable scores from the main effects model, which excludes the interaction term, for both the latent predictor and latent moderator variables (Fassot et al., 2016). The latent variable scores are recorded and used to compute the product indicator for the subsequent stage of analysis, which incorporates the interaction term along with the predictor and moderator variables (Hair et al., 2021).

In structural equation modelling, data analysis is divided into two steps (Ramayah, 2018). The first step involves analysis of the measurement model where assessment of validity and reliability of the items was carried out. The second step involves analysis of the structural model where assessment of the relationship between the latent constructs and hypotheses is tested. Partial least squares (PLS) was used to carry out the analysis of the measurement model and structural model because PLS does not require a large sample size, does not require normally distributed input data, can be applied for complex models, and is useful for prediction (Hair et al., 2019).

4.1. Measurement Model

The measurement model assessed two types of validity, namely, convergent validity and discriminant validity, as proposed by Hair et al. (2017). Convergent validity and reliability were assessed first in the measurement model. Composite reliability was used to test the construct reliability, while average variance extracted (AVE) was used to assess the construct's convergent validity. According to Hair et al. (2021), the threshold value for composite reliability is above 0.70, while the threshold value for AVE is 0.5.

Table 2 showed that the AVE values and composite reliability were above the required levels, meaning there is a high level of reliability and the constructs account for more than half of the differences in their indicators.

Upon confirming the convergent validity and reliability of each construct, the last step is to assess discriminant validity, which evaluates the extent to which it is distinct from other constructs in the study. Cross loadings and the Fornell-Larcker criterion (correlation matrix) are conducted as recommended by Hair et al. (2017). Looking at

Table 3, each item's score is higher on its assigned latent variable than on the other constructs, which shows that there is strong discriminant validity. Next, the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) is checked against the correlations of the latent variables.

Table 4 illustrates that the diagonal values significantly exceed the correlations among the constructs. Consequently, discriminant validity was attained.

4.2. Measurement Model

The subsequent phase following the measurement model is the structural model. This step involved testing hypotheses. R2 values and path coefficients were derived by running the PLS algorithm and bootstrapping with 5,000 samples over 264 cases. The findings are displayed in

Table 5. The R2 score of 0.587 indicates that the four variables account for 58.7 percent of the variance in the intention to purchase EV.

4.3. Mediating Effect of Consumers’ Attitude Toward EV

The advantage of employing SEM for mediation analysis lies in its ability to evaluate the mediating variable within the context of a holistic model (Cheah et al., 2021). Kaur and Kaur (2023) indicate that the analysis of mediating effects encompasses both direct and indirect effects. This study explores the mediating influence of consumers’ attitudes towards EVs on the relationship between various consumption values (including functional, symbolic, emotional, novelty, and conditional values) and the behavioural intention to purchase EVs.

Table 6 presents the findings regarding the mediating effects of consumers' attitudes towards EVs.

4.4. Moderating Effect of Infrastructure Readiness

A moderator variable can be considered as an additional variable that influences the relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variable. It is typically referred to as a contingent variable. Jadil et al. (2022) define a moderator variable as one that affects the relationship between two variables. The influence of the predictor on the criterion is contingent upon the level or values of the moderator.

In examining the moderation effect of infrastructure readiness, the consumers’ attitude towards EV was treated as the independent variable, whereas the behavioural intention to purchase EV was maintained as the dependent variable. The changes in R² and the effect size are crucial for assessing the impact of infrastructure readiness as a moderating factor. The interaction effect of infrastructure readiness was checked using a bootstrapping method in Smart PLS, with a sample size of 500 for this process. The cut-off values for this test were established at 1.645 and 2.33 for significance levels of 0.05 and 0.01, respectively.

Table 7 demonstrates the moderating influence of infrastructure readiness.

5. Discussion

This study reveals that consumers with more favourable attitudes toward EVs exhibit stronger behavioural intention to purchase them. This aligns with the findings of Adnan et al. (2018); Sahoo et al. (2022); and Chaturvedi et al. (2023). This is probably due to the fact that a favourable attitude develops when consumers recognise that EVs provide advantages like environmental sustainability, long-term cost savings, technological advancements, and government incentives. When consumers possess favourable feelings regarding the benefits of EV ownership, they are more inclined to cultivate a positive attitude, which subsequently enhances their intention to make a purchase.

The functional value considerably affects consumer attitudes towards EVs, although it does not directly lead to purchase intention. Attitude, defined as an individual's overall evaluation of a product, is profoundly influenced by cognitive beliefs about the product's effectiveness and utility. When consumers acknowledge EVs as functionally advantageous, offering benefits such as low operating costs, high energy efficiency, and environmental sustainability, they are likely to cultivate a favourable disposition towards them. The Theory of Planned Behaviour asserts that attitudes are formed through behavioural beliefs, which, in this case, are grounded on perceived functional benefits (Ajzen & Cote, 2008). Empirical research substantiates this link; for instance, Boonchunone et al. (2023) found that functional value significantly influenced perceptions of EVs, despite its reduced effect on actual purchasing intentions. Wang et al. (2022) established that perceived utility, an essential element of functional value, significantly affected customer perceptions regarding electric vehicle adoption.

This study indicates that the symbolic value associated with a product, including social meaning, identity expression, and status, does not consistently influence consumer perceptions or purchase intentions for EVs. This is primarily because EVs are not uniformly regarded as status-enhancing or socially prestigious commodities across various markets or demographic segments (Xia et al., 2022). Consumers often perceive EVs as niche or utilitarian, which limits the effectiveness of their symbolic associations (Zamil et al., 2023). Symbolic interpretations of EVs can be contradictory. For some, EVs represent innovation and environmental stewardship; for others, they may signify political affiliation, performance compromise, or elitism. This uncertainty reduces the clarity and appeal of EVs as symbolic entities. High-involvement acquisitions, such as automobiles, are often driven by practical considerations such as range, charging accessibility, and cost rather than by symbolic significance. Thus, consumers who have positive symbolic views may still struggle to convert them into favourable attitudes or purchase intentions if practical issues remain unaddressed. Previous studies supported this limited effect; for instance, Liu et al. (2021) and Xia et al. (2022) found that symbolic value had a lesser or non-significant impact on attitudes and behavioural intentions compared to environmental concerns or perceived functional utility.

Emotional value has emerged as an essential variable influencing consumer attitudes and purchasing intentions for EVs. Emotional value refers to the subjective benefits a product offers, such as feelings of pride, excitement, or satisfaction, which enhance positive assessments of EVs beyond their practical utility (Boonchunone et al., 2023). Unlike functional or symbolic features, emotional value connects on a psychological level, frequently harmonising with consumers' self-identity, values, and aspirations. This connection is especially prominent in the EV scenario, where ownership may elicit a sense of personal commitment to environmental sustainability or technological advancement. The Theory of Consumption Values posits that emotional value is one of the five fundamental determinants of consumer choice, affecting both attitude development and behavioural intention (Aravindan et al., 2023). Empirical research further substantiates this correlation. Maharum et al. (2017) discovered that emotional value substantially affected views towards EVs and the desire to adopt them, frequently exceeding the influence of functional or symbolic value. He and Hu (2022) similarly highlighted that emotional links, such as the pride of being an early adopter or an environmentally concerned consumer, may exert greater influence than practical factors.

While novelty value associated with newness, innovation, and advanced features may initially attract customer attention in EVs, it does not substantially affect attitudes or purchase intentions among consumers in this study. This is probably because novelty typically exerts a temporary impact, as initial enthusiasm diminishes with time, diminishing its effect on consumer evaluation and decision-making. As EVs become more prevalent, their initial allure wanes, and elements such as practical use or emotional resonance become paramount. Moreover, innovation frequently induces perceived risk among consumers, particularly concerning the dependability and enduring efficacy of a novel technology (Theocharis & Tsekouropoulos, 2025). In high-involvement decisions, such as vehicle acquisitions, pragmatic factors like cost, efficiency, and infrastructure outweigh mere novelty. Research corroborates these findings, as Xia et al. (2022) discovered that novelty exerted minimal influence on purchase intention relative to emotional or functional aspects. Rezvani et al. (2015) similarly noted that novelty primarily pertained to early adopters, but social and environmental elements exerted a more significant influence on wider customer demographics. However, the finding contradicts Zhang et al. (2022), who found that the domain-specific innovativeness of EVs leads to adoption among users.

Although numerous studies indicate that conditional value may facilitate the adoption of EVs (Aravindan et al., 2023; Bull et al., 2025), it does not significantly influence customer attitudes or purchase intentions in the current study. This is likely because conditional value depends on context and varies across different locations and times. The existence of tax refunds or incentives may entice specific consumers; nevertheless, these benefits are often transient or geographically limited, reducing their importance in long-term decision-making. Moreover, whereas conditional elements may reduce the perceived cost of adoption, they do not satisfy the essential customer needs for reliability, safety, or emotional satisfaction. Moons and De Pelsmacker (2012) observed that conditional factors, such as subsidies or charging infrastructure, had a limited impact on purchase intention compared to more persistent factors like functional value or emotional appeal. Rezvani et al. (2015) similarly found that the influence of conditional value was less pronounced than that of environmental incentives or personal values, which are more effective in fostering consumer commitment. Thus, while conditional value may facilitate short-term adoption, it does not significantly affect attitudes or purchase intentions, particularly for high-involvement purchases like automobiles, where consumers emphasise long-term, intrinsic factors. However, the finding contradicts Alganad et al. (2021), who found that conditional value positively influences consumers' sentiments and purchase intentions for energy-efficient vehicles.

The present study discovered that attitude mediates the association between functional value and the behavioural purchase intention of EVs. This is in line with the TCV which asserts that consumer selection is affected by several value dimensions, with functional value being paramount in the assessment of utilitarian items such as EVs. Functional value denotes the perceived utility obtained from a vehicle's practical advantages, including performance, energy efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and reliability (Lin & Huang, 2012). Consumers that possess a favourable disposition towards EVs are more inclined to acknowledge and value these functional characteristics, hence augmenting their confidence and incentive to make a purchase (Teoh & Mohd Noor, 2015). In this context, functional value acts as a cognitive filter, converting overall optimism (attitude) into active intent. Empirical evidence supports this mediation effect. Ye et al (2021) discovered that functional value significantly influenced the association between attitudes and behavioural intentions regarding green vehicles. Wang et al. (2022) similarly indicated that functional value, encompassing evaluations of fuel efficiency and driving performance, reinforced the connection between attitude and EV purchase intention. This finding indicates that even when buyers possess a favourable disposition towards EVs, their intention to purchase is further solidified when functional advantages are distinctly recognised and assessed.

Similarly, this study found that attitude mediates the relationship between emotional value and behavioural intention to purchase EVs. As previously discussed, emotional value plays a significant role in shaping consumer behaviour, particularly when it comes to high-involvement and value-oriented items such as EVs. The TCV posits that emotional value pertains to the feelings or affective states elicited by a product in the consumer, including pride, enthusiasm, or satisfaction (Sheth et al., 1991). In the realm of EVs, consumers may derive emotional value from viewing themselves as environmentally responsible, inventive, or socially aware. Emotional value alone does not directly influence behavioural intentions; instead, it typically operates indirectly through attitude, which serves as a cognitive filter that converts emotional responses into evaluative judgements (Wang et al., 2022). Consumers that experience significant emotional satisfaction from EVs are inclined to form positive views towards them, hence enhancing their purchase intention (Rezvani et al., 2015). The evidence indicates that attitude influences the process by converting emotional experiences into a consistent and rational preference for EV ownership. This finding is consistent with Kim et al. (2017), who discovered that emotional value significantly affected attitude, which subsequently enhanced consumers' desire to select environmentally friendly items. In the realm of EV adoption, emotional value was identified as a factor that predominantly influences intention through its impact on attitude, rather than serving as a direct predictor (Ye et al., 2021)

The study's findings indicated that infrastructure readiness did not significantly moderate the association between attitude and behavioural intention to purchase EVs. This outcome indicates that consumers who possess a favourable disposition towards EVs are likely to establish buying intentions, irrespective of their perceptions of the adequacy of charging infrastructure. One possible explanation lies in the differentiation between internal and external influences as delineated in the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991). Attitude is an internal psychological construct rooted in individual ideas, values, and assessments of behaviour; infrastructure readiness is an external contextual aspect. The development of buying intention based on attitude may transpire independently of perceived infrastructural sufficiency. In fact, in some market situations, like cities or places where the government supports EVs, consumers might see the charging infrastructure as "good enough" or improving, which can lessen its effect on their choices. This conclusion aligns with previous research indicating that infrastructure readiness significantly impacts actual or perceived behavioural control rather than mitigating the influence of attitudes on intention (Rezvani et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2022). Furthermore, early adopters or ecologically conscious consumers may be inclined to disregard infrastructural deficiencies, placing greater emphasis on their ideals and convictions than on practical issues (Palm, 2020).

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that emotional and functional values are critical in shaping consumer attitudes towards EVs, thereby significantly influencing behavioural purchase intentions. The results indicate several important implications for managers in the EV industry. Marketers should prioritise techniques that enhance emotional engagement, such as emphasising environmental stewardship, social prestige, and a progressive lifestyle in their campaigns to develop positive emotional connections with EV ownership.

Emotional appeals enhance brand loyalty and influence consumer preference, especially among younger, urban demographics. Furthermore, highlighting the practical benefits of EVs, including lower fuel costs, decreased maintenance expenses, enhanced performance, and government incentives, can strengthen positive perceptions and purchasing intentions. Transparent and data-driven communication through marketing, showroom interactions, and digital platforms can effectively bridge the information gap for potential buyers.

Additionally, automobile manufacturers and dealerships should consider implementing test drive initiatives, interactive digital simulations, or testimonial-based content to demonstrate the emotional satisfaction and functional superiority of EVs. These strategies reduce uncertainty and promote trust among hesitant consumers. The findings suggest that policymakers and city planners should back efforts that make EVs more appealing, like promoting eco-friendly public EV projects and making charging easier, to help change people's attitudes and encourage more people to buy them.

While this study provides important insights into the ways emotional and functional values shape attitudes and intentions regarding EV adoption, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. This study was confined to Klang Valley, which is recognised as Malaysia’s most urbanised area. This setting is suitable for examining early adopters of EVs; however, it restricts the applicability of the findings to other areas, especially rural or semi-urban regions where factors such as infrastructure readiness, income levels, and consumer awareness might vary significantly. Future studies ought to incorporate comparative research across various regions to improve the external validity of the findings.

The cross-sectional design employed in this study limits the capacity to draw causal inferences. Conducting longitudinal studies would provide valuable insights into the shifts in consumer perceptions and behavioural intentions over time, particularly in relation to changing government policies, technological progress, and market incentives.

The dependence on self-reported data raises concerns regarding social desirability and recall bias. To address this, subsequent studies might utilise mixed-method approaches or behavioural data (e.g., actual purchase records, test drive participation) to confirm attitudinal measures. Lastly, future studies may investigate the influence of moderating variables like environmental concern, perceived risk, or trust in government incentives, which could provide a more nuanced understanding of the boundary conditions surrounding attitude-intention relationships.

Author Contributions

Nor Azila Mohd Noor: She has formulated the idea notion to explore this issue and prepare the introduction, literature section and final draft of the article. Azli Muhammad: Participated in the data collection process. Filzah Md Isa: Assisted Azli Muhammad in collecting data. Mohd Farid Shamsudin: Methodology and implications of this study. Tuanku Nur Atikhah: Data analysis.

Funding

This research was fully funded by the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) Malaysia through Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2023/SS01/UUM/01/1) with project ID 472183-501135.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported and funded by the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) Malaysia through Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2023/SS01/UUM/01/1) with project ID 472183-501135; FRGS 2023-1 and SO Code: 21573.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EV |

Electric Vehicle |

| TCV |

Theory of Consumption Value |

| SEM |

Structural Equation Modelling |

| |

|

References

- Adepetu, A., & Keshav, S. (2017). The relative importance of price and driving range on electric vehicle adoption: Los Angeles case study. Transportation, 44, 353-373.

- Adnan, N., Nordin, S. M., Rahman, I., Vasant, P., & Noor, M. A. (2018). An overview of electric vehicle technology: a vision towards sustainable transportation. Intelligent Transportation and Planning: Breakthroughs in Research and Practice, 292-309.

- Afroz, R., Rahman, A., Masud, M. M., Akhtar, R., & Duasa, J. B. (2015). How individual values and attitude influence consumers’ purchase intention of electric vehicles—Some insights from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 6(2), 193-211.

- Ahmad, S., Chaveeesuk, S., & Chaiyasoonthorn, W. (2024). The adoption of electric vehicle in Thailand with the moderating role of charging infrastructure: an extension of a UTAUT. International Journal of Sustainable Energy, 43(1), 2387908. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W., & Zhang, Q. (2020). Green purchase intention: Effects of electronic service quality and customer green psychology. Journal of Cleaner Production, 267, 122053. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179 – 211.

- Ajzen, I., & Cote, N. G. (2008). Attitudes and the prediction of behavior. Attitudes and Attitude Change, 13, 289-305.

- Ajzen, I., Fishbein, M., Lohmann, S., & Albarracín, D. (2018). The influence of attitudes on behavior. The Handbook of Attitudes, 1, 197-255.

- Akkaya, M. (2021). Understanding the impacts of lifestyle segmentation & perceived value on brand purchase intention: An empirical study in different product categories. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 27(3), 100155. [CrossRef]

- Albaity, M., & Melhem, S. B. (2017). Novelty seeking, image, and loyalty—The mediating role of satisfaction and moderating role of length of stay: International tourists' perspective. Tourism Management Perspectives, 23, 30-37.

- Alganad, A. M. N., Isa, N. M., & Fauzi, W. I. M. (2021). Boosting green cars retail in Malaysia: The influence of conditional value on consumers’ behaviour. Journal of Distribution Science, 19(7), 87-100.

- AlShurman, B. A., Khan, A. F., Mac, C., Majeed, M., & Butt, Z. A. (2021). What demographic, social, and contextual factors influence the intention to use COVID-19 vaccines: a scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 9342. [CrossRef]

- Amin, S., & Tarun, M. T. (2021). Effect of consumption values on customers’ green purchase intention: a mediating role of green trust. Social Responsibility Journal, 17(8), 1320-1336.

- Amoah, F., Radder, L., & van Eyk, M. (2016). Perceived experience value, satisfaction and behavioural intentions: A guesthouse experience. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 7(3), 419-433.

- An, K. P. C., & Kamaruddin, N. K. (2024). The Relationship between Perceived Benefit and Perceived Risk Toward Electric Vehicle (EV) Purchase Intention Among Consumers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Research in Management of Technology and Business, 5(1), 346-364.

- Anand, M. P., Bagen, B., & Rajapakse, A. (2020). Probabilistic reliability evaluation of distribution systems considering the spatial and temporal distribution of electric vehicles. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 117, 105609. [CrossRef]

- Aravindan, K. L., Ramayah, T., Thavanethen, M., Raman, M., Ilhavenil, N., Annamalah, S., & Choong, Y. V. (2023). Modeling positive electronic word of mouth and purchase intention using theory of consumption value. Sustainability, 15(4), 3009. [CrossRef]

- Arghashi, V., & Yuksel, C. A. (2022). Interactivity, Inspiration, and Perceived Usefulness! How retailers’ AR-apps improve consumer engagement through flow. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 64, 102756.

- Asadi, S., Nilashi, M., Iranmanesh, M., Ghobakhloo, M., Samad, S., Alghamdi, A., ... & Mohd, S. (2022). Drivers and barriers of electric vehicle usage in Malaysia: A DEMATEL approach. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 177, 105965. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf Javid, M., Ali, N., Abdullah, M., Campisi, T., & Shah, S. A. H. (2021). Travelers’ adoption behavior towards electric vehicles in lahore, Pakistan: An extension of norm activation model (NAM) theory. Journal of Advanced Transportation, 2021(1), 7189411.

- Bahoo, S., Umar, R. M., Mason, M. C., & Zamparo, G. (2024). Role of theory of consumption values in consumer consumption behavior: a review and Agenda. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 34(4), 417-441. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, N., Steel, M., Ogden, S., & Rahman, K. (2020). Consumer motivations to create alternative consumption platforms. Australasian Marketing Journal, 28(3), 50-57. [CrossRef]

- Baker, M. T., Lu, P., Parrella, J. A., & Leggette, H. R. (2022). Consumer acceptance toward functional foods: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1217.

- Beck, M. J., Rose, J. M., & Greaves, S. P. (2017). I can’t believe your attitude: a joint estimation of best worst attitudes and electric vehicle choice. Transportation, 44, 753-772. [CrossRef]

- Boonchunone, S., Nami, M., Krommuang, A., Phonsena, A., & Suwunnamek, O. (2023). Exploring the effects of perceived values on consumer usage intention for electric vehicle in Thailand: the mediating effect of satisfaction. Acta Logistica, 10(2), 151-164. [CrossRef]

- Bull, S., Buch, K., Freling, C., Hardman, S., & Firestone, J. (2025). Electric vehicles and rooftop solar energy: Consumption values influencing decisions and barriers to co-adoption in the United States. Energy Research & Social Science, 122, 103990. [CrossRef]

- Büyükdağ, N., Soysal, A. N., & Ki̇tapci, O. (2020). The effect of specific discount pattern in terms of price promotions on perceived price attractiveness and purchase intention: An experimental research. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102112. [CrossRef]

- Candan, B., & Yıldırım, S. (2013). Investigating the relationship between consumption values and personal values of green product buyers. International Journal of Economics and Management Sciences, 2(12), 29-40.

- Chaerudin, S. M., & Syafarudin, A. (2021). The effect of product quality, service quality, price on product purchasing decisions on consumer satisfaction. Ilomata International Journal of Tax and Accounting, 2(1), 61-70. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D., & Paul, J. (2023). Healthcare apps’ purchase intention: A consumption values perspective. Technovation, 120, 102481. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D., Siddiqui, M., & Siddiqui, A. (2022). Can initial trust boost intention to purchase Ayurveda products? A theory of consumption value (TCV) perspective. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 46(6), 2521-2541. [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, P., Kulshreshtha, K., Tripathi, V., & Agnihotri, D. (2023). Exploring consumers' motives for electric vehicle adoption: bridging the attitude–behavior gap. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 30(10), 4174-4192.

- Chawla, D., & Joshi, H. (2019). Consumer attitude and intention to adopt mobile wallet in India–An empirical study. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(7), 1590-1618. [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J. H., Nitzl, C., Roldán, J., Cepeda-Carrion, G., & Gudergan, S. P. (2021). A primer on the conditional mediation analysis in PLS-SEM. The Data Base for Advances in Information Systems, 52, 43-100. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Liu, X., Yu, J., & Okubo, K. (2025). Residual Performance Evaluation of Electric Vehicle Batteries: Focusing on the Analysis Results of a Social Survey of Vehicle Owners. Sustainability, 17(10), 4685. [CrossRef]

- Chi, T. (2018). Mobile commerce website success: Antecedents of consumer satisfaction and purchase intention. Journal of Internet Commerce, 17(3), 189-215. [CrossRef]

- Choe, J. Y. J., & Kim, S. S. (2018). Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 71, 1-10.

- Choi, D., & Johnson, K. K. (2019). Influences of environmental and hedonic motivations on intention to purchase green products: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 18, 145-155. [CrossRef]

- Coffman, M., Bernstein, P., & Wee, S. (2017). Electric vehicles revisited: A review of factors that affect adoption. Transportation Review. 37, 79–93.

- Dangelico, R. M., Nonino, F., & Pompei, A. (2021). Which are the determinants of green purchase behaviour? A study of Italian consumers. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(5), 2600-2620.

- Dangi, N., Gupta, S. K., & Narula, S. A. (2020). Consumer buying behaviour and purchase intention of organic food: a conceptual framework. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 31(6), 1515-1530. [CrossRef]

- Diallo, M. F., & Seck, A. M. (2018). How store service quality affects attitude toward store brands in emerging countries: Effects of brand cues and the cultural context. Journal of Business Research, 86, 311-320.

- Ehsan, F., Habib, S., Gulzar, M. M., Guo, J., Muyeen, S. M., & Kamwa, I. (2024). Assessing policy influence on electric vehicle adoption in China: an in-Depth study. Energy Strategy Reviews, 54, 101471. [CrossRef]

- Fang, W., Xin, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2023). Eco-label knowledge versus environmental concern toward consumer's switching intentions for electric vehicles: A roadmap toward green innovation and environmental sustainability. Energy & Environment, 0958305X231177735. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D., Harbrecht, A., Surmann, A., & McKenna, R. (2019). Electric vehicles’ impacts on residential electric local profiles–A stochastic modelling approach considering socio-economic, behavioural and spatial factors. Applied Energy, 233, 644-658.

- Gallego-Alberto, L., Losada, A., Márquez-González, M., Romero-Moreno, R., & Vara, C. (2017). Commitment to personal values and guilt feelings in dementia caregivers. International psychogeriatrics, 29(1), 57-65. [CrossRef]

- Goel, P., Kumar, A., Parayitam, S., & Luthra, S. (2023). Understanding transport users' preferences for adopting electric vehicle based mobility for sustainable city: A moderated moderated-mediation model. Journal of Transport Geography, 106, 103520. [CrossRef]

- Gulzari, A., Wang, Y., & Prybutok, V. (2022). A green experience with eco-friendly cars: A young consumer electric vehicle rental behavioral model. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 65, 102877.

- Hair Jr, J. F., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107-123.

- Hair, J. F. Jr, Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Moderation analysis. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A workbook (pp. 155–172). Springer.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLSSEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24.

- Han, H., Hsu, L. T. J., & Sheu, C. (2010). Application of the theory planned behaviour to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tourism Management, 31(3), 325 – 334.

- Han, L., Wang, S., Zhao, D., & Li, J. (2017). The intention to adopt electric vehicles: Driven by functional and non-functional values. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 103, 185-197.

- Han, S. L., & Kim, K. (2020). Role of consumption values in the luxury brand experience: Moderating effects of category and the generation gap. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57, 102249.

- Hardy III, J. H., Ness, A. M., & Mecca, J. (2017). Outside the box: Epistemic curiosity as a predictor of creative problem solving and creative performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 230-237.

- Haustein, S., & Jensen, A. F. (2018). Factors of electric vehicle adoption: A comparison of conventional and electric car users based on an extended theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 12(7), 484-496. [CrossRef]

- He, X., & Hu, Y. (2022). Understanding the role of emotions in consumer adoption of electric vehicles: the mediating effect of perceived value. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 65(1), 84-104.

- Hettiarachchi, W. N., & Lakmal, H. A. (2018). The impact of perceived value on satisfaction of adventure tourists: with special reference to Sri Lankan domestic tourists. Colombo Business Journal, 9(1), 80-107. [CrossRef]

- Higueras-Castillo, E., Liébana-Cabanillas, F., Santos, M. A. D., Zulauf, K., & Wagner, R. (2024). Do you believe it? Green advertising skepticism and perceived value in buying electric vehicles. Sustainable Development, 32(5), 4671-4685.

- Hill, R. J. (2017). Attitudes and behavior. In Social psychology (pp. 347-377). Routledge.

- Hoek, A. C., Malekpour, S., Raven, R., Court, E., & Byrne, E. (2021). Towards environmentally sustainable food systems: decision-making factors in sustainable food production and consumption. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 26, 610-626. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.H., Gowrie, V., Muhammad Madi Abdullah, & Nasreen, K. (2012). A study of hybrid car adoption in Malaysia. Paper presented at the 2nd Annual Summit on Business and Entrepreneurial Studies (2nd ASBES 2012) Proceeding, Sarawak, Malaysia.

- Hur, E. (2020). Rebirth fashion: Second hand clothing consumption values and perceived risks. Journal of Cleaner Production, 273, 122951.

- Husain, I., Ozpineci, B., Islam, M. S., Gurpinar, E., Su, G. J., Yu, W., ... & Sahu, R. (2021). Electric drive technology trends, challenges, and opportunities for future electric vehicles. Proceedings of the IEEE, 109(6), 1039-1059. [CrossRef]

- Husain, R., Wahab, N. S. A., & Husain, R. (2023). Awareness of CO2 Emission by Cars and Eco-Friendly Environment in the Malaysian Automotive Industry: A Study on Drivers’ Perspectives. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 13(8), 463-482. [CrossRef]

- Indriani, I. A. D., Rahayu, M., & Hadiwidjojo, D. (2019). The influence of environmental knowledge on green purchase intention the role of attitude as mediating variable. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding, 6(2), 627-635. [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M., & Ahmad, M. (2021). Relating consumers' information and willingness to buy electric vehicles: Does personality matter?. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 100, 103049. [CrossRef]

- Ives, C. D., & Kidwell, J. (2019). Religion and social values for sustainability. Sustainability Science, 14, 1355-1362. [CrossRef]

- Jadil, Y., Jeyaraj, A., Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., & Sarker, P. (2022). A meta-analysis of the factors associated with s-commerce intention: Hofstede's cultural dimensions as moderators. Internet Research, 33(6), 2013-2057. [CrossRef]

- Jakučionytė-Skodienė, M., Dagiliūtė, R., & Liobikienė, G. (2020). Do general pro-environmental behaviour, attitude, and knowledge contribute to energy savings and climate change mitigation in the residential sector?. Energy, 193, 116784. [CrossRef]

- Judge, M., Warren-Myers, G., & Paladino, A. (2019). Using the theory of planned behaviour to predict intentions to purchase sustainable housing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 215, 259-267. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H. J., Choi, Y. J., & Oh, K. W. (2020). Influencing factors of Chinese consumers’ purchase intention to sustainable apparel products: Exploring consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. Sustainability, 12(5), 1770. [CrossRef]

- Junquera, B., Moreno, B., & Álvarez, R. (2016). Analyzing consumer attitudes towards electric vehicle purchasing intentions in Spain: Technological limitations and vehicle confidence. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 109, 6-14.

- Kanchanapibul, M., Lacka, E., Wang, X., & Chan, H. K. (2014). An empirical investigation of green of purchase - Cleaner behaviour among 66, the young. Generation. Journal Production, 528-536.

- Karjaluoto, H., Shaikh, A. A., Saarijärvi, H., & Saraniemi, S. (2019). How perceived value drives the use of mobile financial services apps. International Journal of Information Management, 47, 252-261.

- Kaur, D., & Kaur, R. (2023). Does electronic word-of-mouth influence e-recruitment adoption? A mediation analysis using the PLS-SEM approach. Management Research Review, 46(2), 223-244.

- Kaur, P., Dhir, A., Talwar, S., & Ghuman, K. (2021). The value proposition of food delivery apps from the perspective of theory of consumption value. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(4), 1129-1159.

- Kautish, P., & Sharma, R. (2021). Study on relationships among terminal and instrumental values, environmental consciousness and behavioral intentions for green products. Journal of Indian Business Research, 13(1), 1-29.

- Khan, S. N., & Mohsin, M. (2017). The power of emotional value: Exploring the effects of values on green product consumer choice behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 150, 65-74.

- Kim, S., Lee, J., & Lee, C. (2017). Does driving range of electric vehicles influence electric vehicle adoption?. Sustainability, 9(10), 1783.

- Klein, C., Keller, B., Silver, C. F., Hood, R. W., & Streib, H. (2016). Positive adult development and “spirituality”: Psychological well-being, generativity, and emotional stability. Semantics and Psychology of Spirituality: A Cross-Cultural Analysis, 401-436.

- Knowles, M., Scott, H., & Baglee, D. (2012). The effect of driving style on electric vehicle performance, economy and perception. International Journal of Electric and Hybrid Vehicles, 4(3), 228-247.

- König, A., Nicoletti, L., Schröder, D., Wolff, S., Waclaw, A., & Lienkamp, M. (2021). An overview of parameter and cost for battery electric vehicles. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 12(1), 21.

- Kosse, F., Deckers, T., Pinger, P., Schildberg-Hörisch, H., & Falk, A. (2020). The formation of prosociality: causal evidence on the role of social environment. Journal of Political Economy, 128(2), 434-467.