The ever-growing application of technology in business and the economy presents numerous opportunities and challenges for stakeholders. Government authorities and public entities, such as financial supervisory authorities, central banks, and securities commissions, are public institutions responsible for overseeing financial markets, which means safeguarding economic stability. These organizations face mounting pressure to modernize in response to the rapid technological changes occurring worldwide.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly becoming a crucial tool for many organizations to enhance their internal operations and respond to rapidly changing market trends. For instance, approximately 72% of organizations globally have adopted AI (McKinsey, 2024). Additionally, 8% of EU enterprises utilize AI technologies, with adoption rates of 30.4% for larger companies (Eurostat, 2024). Despite this momentum, public institutions often face distinct barriers to AI adoption, including bureaucratic inertia, outdated infrastructure, limited procurement flexibility, and heightened expectations around transparency and accountability.

The above challenges are particularly acute in the public sector, where failures in implementation can have broader social and economic consequences.

Indeed, several public sector organizations struggle to adopt AI due to various legal, technical, and operational hurdles (Rane, 2024), highlighting the urgent need for a structured and replicable approach to AI adoption.

The study builds on the growing demand for evidence-based frameworks that governmental institutions and public authorities can use to navigate the integration of AI. The document outlines a pragmatic approach and presents key findings from a government organization on AI adoption and pilot projects as a method for effective AI implementation. The primary objectives of this research are to:

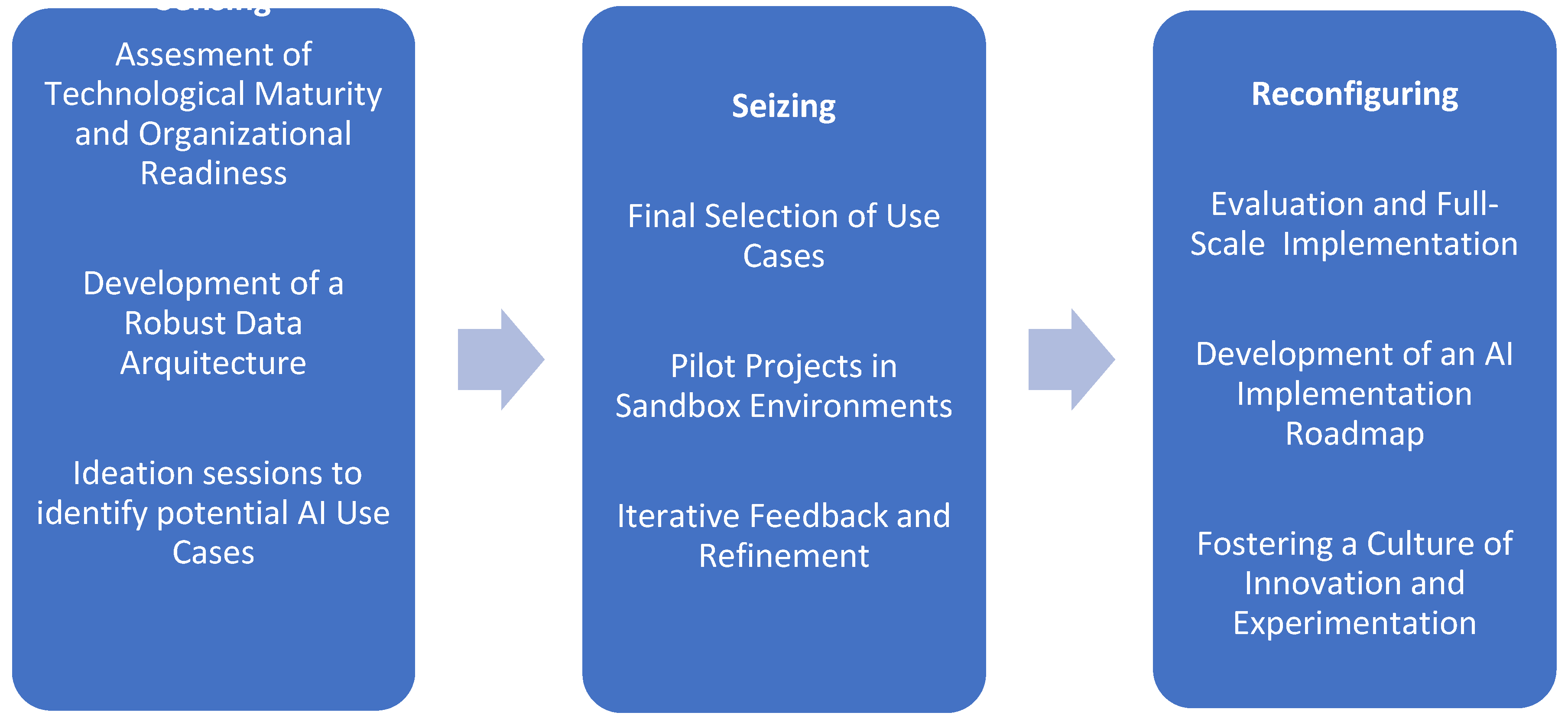

To address the above objectives, this study interprets the XYZ Government Financial Regulator’s AI adoption through the Dynamic Capabilities lens (Teece, 2007), focusing on three main functions:

1. Sensing: How the organization identified AI opportunities in its regulatory processes.

2. Seizing: How sandbox pilots and iterative feedback mobilized resources to capture value.

3. Reconfiguring: How infrastructure, culture, and governance were realigned for full deployment.

By doing so, we deepen the understanding of public-sector AI adoption and extend Dynamic Capabilities theory into highly regulated contexts.

This paper is organized as follows. The literature review provides an overview of existing studies on AI in organizations, emphasizing its benefits, challenges, and ethical considerations. It also introduces the dynamic capabilities framework as a theoretical lens to examine how public sector institutions adapt, integrate, and reconfigure resources for effective AI adoption. The methodology outlines the data collection and analysis techniques employed in this study. The results section presents findings aligned with the research objectives, including an evaluation of the AI adoption process and its alignment with global best practices. Finally, the discussion and conclusion highlight the implications of the findings, providing recommendations for public sector authorities and leaders, as well as suggesting future research directions.

1. Literature Review

Building on established strategic-management lenses, this review first examines how Dynamic Capabilities (Teece, 2007) and the Resource-Based View (Barney, 1991) have been applied to digital transformation, before turning to empirical studies of AI adoption in both private firms and public agencies. Then it revises the work on AI for inclusive business and SDG-aligned innovation, highlighting how technology can generate shared value in emerging market contexts (Prahalad & Hart, 2002; Kramer & Porter, 2011). Finally, we identify a gap (and thus, contribution): while numerous descriptive accounts document AI pilots in the government sector, few explicitly link those experiences to theory or assess their implications for innovation.

1.1. Strategic Management Theories and AI

Dynamic Capabilities theory asserts that in rapidly evolving environments, firms must develop the ability to sense new opportunities and threats, seize them by mobilizing resources, and reconfigure their asset and organizational structures to maintain a competitive edge (Teece, 2007; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000).

The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated the importance of these capabilities. Some public institutions were able to rapidly adopt digital tools, shift workflows, and respond to emerging citizen needs, while others struggled due to rigid structures or lack of preparedness (Christensen & Lægreid, 2020; Mergel, Edelmann, & Haug, 2019).

In this framework:

Sensing refers to the ability to identify technological trends, market shifts, and external risks or opportunities (Teece, 2007). During the pandemic, this capability was evident in agencies that systematically monitored infection trends, anticipated service disruptions, and recognized the need to accelerate digital services (Ansell & Sørensen, 2020).

Seizing involves mobilizing resources and making timely decisions to capture value from identified opportunities (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). For example, governments that rapidly deployed digital platforms for emergency financial aid or implemented AI-powered citizen service tools demonstrated high levels of seizing capability (Eom & Lee, 2022).

Reconfiguration is the process of reshaping organizational structures, workflows, and capabilities to support long-term adaptation (Teece, Peteraf, & Leih, 2016). This was evident in public institutions that overhauled outdated IT systems, created agile task forces, and retrained personnel to support digitally enabled service delivery beyond the crisis period (Mazzucato & Kattel, 2020).

In practice, sensing involves systematic market and technology scanning, such as piloting AI use cases or conducting workforce readiness audits, while seizing requires deploying resources through controlled experiments like sandbox environments. Reconfiguration then realigns processes, governance frameworks, and skill sets to embed successful innovations at scale. Complementing this, the Resource-Based View highlights that only resources which are Valuable, Rare, Inimitable, and Non-substitutable (VRIN), for example, robust data architectures and specialized AI talent, can underpin sustained performance (Barney, 1991; Hart & Milstein, 2003). Together, these lenses help explain whether an organization adopts AI and how it systematically builds and renews organizational capabilities to leverage AI for strategic and development outcomes.

1.2. AI Adoption in Digital Transformation

Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers to systems or technologies that mimic human cognitive processes such as learning, reasoning, and decision-making (Russell & Norvig, 2021). It utilizes machine learning (ML), natural language processing (NLP), and robotics to solve tasks that require human intelligence and expertise. AI has a range of applications, including process automation, predictive analytics, customer service, and compliance (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2016).

AI helps transform organizations by enabling real-time data analysis, anomaly detection, and informed decision-making. For instance, AI tools can streamline the reporting process through automation, enabling the classification of compliance filings (Bostrom & Yudkowsky, 2018). This versatility demonstrates AI’s ability to handle the operational and strategic burdens of modern organizations, including those faced by entities with complex operations, challenging data sets, or high-stakes decisions.

Recently, Large Language Models (LLMs) and Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools have brought us new frontiers in content creation, customer interaction, and strategic planning (Chen et al., 2020). AI integration offers organizations myriad benefits, enhancing efficiency, accuracy, and decision-making. One notable advantage of AI systems is that they can process vast datasets in real-time, uncovering patterns while providing actionable insights. Regardless of industry, AI-powered predictive analytics can detect fraudulent activities and assess market risks (Javaid, 2024).

AI has significantly improved most operational aspects, primarily through machine learning (ML) and natural language processing (NLP). Bostrom (2014) discusses how AI can optimize the decision-making process, minimize expenses, and increase authorities' efficiency in detecting and addressing market shifts. For instance, machine learning algorithms can analyze various financial records to identify potentially suspicious patterns arising from fraudulent operations or law violations (Mehrabi et al., 2021).

Automation is another key benefit of AI, reducing the burden of repetitive tasks and enabling employees to focus on higher-value activities. For example, AI-powered chatbots in customer service operations decrease response times and operate 24/7 (Adam et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2022). Moreover, AI enhances compliance and risk management by automating monitoring and reporting processes, as well as detecting anomalies in financial transactions (Fares et al., 2023). These advancements have drawn the interest of government entities, which utilize them to enhance efficiency and oversight or to address emerging risks in dynamic markets.

1.3. Governmental AI and Theoretical Gaps

Recent case studies demonstrate how AI enhances both creative and regulatory tasks in government and quasi-government settings. For example, Wirtz et al. (2019) provide a comprehensive overview of how AI technologies are being introduced in the public sector, emphasizing both the operational potential and the institutional barriers that shape adoption. Similarly, Mergel (2019) highlights how national governments have established Digital Service Teams (DSTs) as agile, semi-autonomous units outside traditional CIO structures to accelerate the adoption of digital services while addressing the challenges faced by the public sector.

Despite AI’s transformative potential, integrating it into organizations is fraught with obstacles. Many government organizations need more in-house expertise to develop, deploy, and manage their AI systems (Aderibigbe, 2023). Training programs and partnerships with external technology providers are resource-demanding. Another challenge is resistance to change within public sector organizational cultures, where employees may distrust AI systems or fear that they will put their jobs at risk. These challenges require holistic solutions that combine technical, managerial, and cultural approaches.

Incorporating AI into regulatory processes poses ethical and legal questions. Mittelstadt et al. (2016) suggested that algorithmic transparency and accountability are mandatory to avoid AI unfairness. Monitoring is especially crucial for issues such as algorithmic bias and data privacy (Ntoutsi et al., 2020). AI is capable of mirroring or even intensifying pre-existing biases in government \ processes. If the training data used to develop an AI system contained prejudiced information, the resulting choice may put one group at a disadvantage (Bostrom & Yudkowsky, 2018). Involving stakeholders from disadvantaged communities in governance processes is crucial for mitigating undesired side effects and ensuring that AI will be a positive factor for all members of society (Cath et al., 2018). Organizations should also implement regular impact assessments to protect individuals or groups from unfair treatment (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019a).

The ethical consideration of applying AI in government also entails safeguarding data privacy. Since the information handled by governing bodies is often sensitive, strict data management measures are needed to prevent privacy infringements. The measures public sector organizations must implement include adhering to legal requirements, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and other relevant data protection legislation (Benhamou, 2020).

To address these challenges, it is necessary to utilize the dynamic capabilities framework and engage the interests of key stakeholders within government organizations. According to Floridi and Cowls (2019), developing ethical frameworks to safeguard the design and use of AI is crucial. These frameworks ensure alignment with societal values and prevent the perpetuation or exacerbation of existing biases. Agbese et al. (2023) also assert that AI practice requires a deep understanding of ethical issues. Furthermore, ethical considerations in management practices require public sector organizations to apply AI responsibly by the accepted standards of society.

The interpretability of the models is correlated to transparency and trust (Mehrabi et al., 2021). Public authorities should demand that any AI for decision-making is explicable; in other words, humans should be able to audit and comprehend the reasoning behind the AI’s output. Notably, the necessity of explicability arises when an AI decision-maker's decision, such as that of a police officer or a social services officer, can have a substantial impact on an individual or a group. Applying AI use cases in regulatory agencies and government entities requires a clear understanding of the environment, including ethical issues and available regulatory preventive measures against potential mishaps. Therefore, human intervention remains beneficial for AI applications, particularly in government sectors. While AI systems can aid decision-making, they should not replace human decision-making in high-risk, high-stakes situations (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019b). The existing literature supports assisted AI, where tools augment human capabilities without replacing human judgment. This approach also guarantees that final decisions consider human mechanisms more than systematic interpretation of the analysis (European Union, 2019).

AI frameworks must address different factors and implementation challenges (Ångström, 2023). Weber et al. (2022) provide insights into the organizational capabilities necessary for deploying AI in government settings, emphasizing that project planning and co-development are crucial due to the opacity and data reliance of AI technologies. Their research recommends that government organizations be prepared and dynamic when integrating AI into their existing structures and practices. De Santis (2024) elaborates on the need for implementation frameworks that enable AI across different domains. The case studies demonstrate that a systemic understanding and frameworks are crucial for integrating AI technology into diverse application areas. Tapping into existing knowledge from implementation science paradigms may be beneficial for public sector organizations seeking to implement AI at varying levels of maturity (Lichtenthaler, 2020).

Despite a growing number of descriptive studies on government AI pilots and risk-management applications, few works explicitly link these empirical insights to established strategic management theories, such as Dynamic Capabilities and the Resource-Based View.

1.4. AI Adoption in Government Financial Regulators

Government financial regulators, such as central banks, financial supervisory authorities, and securities commissions, operate at the intersection of public accountability, legal mandates, and market oversight. These government entities face distinct pressures to adopt AI in ways that ensure regulatory efficiency while safeguarding systemic stability (Arner et al., 2017).

Financial regulators are responsible for supervising financial institutions, enforcing compliance, managing systemic risk, promoting market integrity, and other related activities. Hence, the entities must respond with agility and precision (World Bank, 2022; Financial Stability Board, 2019) to increasing and evolving market conditions.

In the financial regulator sector, AI provides fraud detection capabilities while handling clients’ issues. For instance, Benhamou (2020) discusses how machine learning (ML) models detect fraudulent transactions from merchants and eliminate time-consuming manual procedures, resulting in rapid responses. Bostrom and Yudkowsky (2018) also demonstrate the application of NLP in streamlining activities such as compliance filings and analyzing regulators' documents.

However, the adoption of AI tools remains uneven and slower compared to the private sector (Broeders & Prenio, 2018), mainly because of several institutional constraints: conservative risk cultures, legacy IT systems, opaque procurement processes, and heightened scrutiny around legal compliance and ethical standards (Arner et al., 2017).

While descriptive studies and international policy reports have explored early-stage AI pilots in regulatory agencies, few have applied established strategic management theories to explain how these institutions evolve in response to technological change. This paper addresses this gap by applying the Dynamic Capabilities framework (Teece, 2007) as a strategic lens to examine how a government financial regulator authority has approached the integration of AI.

2. Materials and Methods

This case study examined the process of integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) solutions into the operations of a government entity, anonymized as "The XYZ Government Financial Regulator." This study employs a mixed-methods research strategy, complemented by elements of explanatory research. Specifically, it aims to understand how strategic AI implementation has been adopted within a government organization and to identify the frameworks that might be beneficial for similar projects. Although the study has an exploratory nature by design, it also includes explanatory features by examining the interrelationships between the variables of interest, such as the association between workforce training and enhanced system accuracy, which helps to explain the observed phenomena. The study builds on the research objectives outlined in the introduction. It is guided by the following research question: What factors influence XYZ Organization's adoption of AI technologies, and how can these insights guide strategies for addressing operational challenges and enhancing performance outcomes in financial supervision?

The XYZ Government Financial Regulator’s AI integration strategy employed a phased approach that reflects the core dimensions of the Dynamic Capabilities framework—sensing, seizing, and reconfiguration This involved identifying technological opportunities and risks (sensing), piloting and allocating resources to AI-driven initiatives (seizing), and restructuring internal processes and capabilities to support sustainable implementation (reconfiguration). The strategy enabled rigorous testing and refinement of AI solutions in controlled environments before their full-scale deployment. The strategy was analyzed in detail, examining its underlying rationale, implementation steps, and effectiveness in achieving desired outcomes.

Ethical considerations were paramount throughout the research process. To ensure the privacy and security of sensitive information, the process guaranteed participant confidentiality and compliance with relevant data protection regulations. The data used in this study were de-identified prior to analysis. The dataset comprised exclusively secondary data obtained from the organization’s internal sources, including project documentation, system logs, and aggregated user feedback. These data were not personally identifiable and did not involve direct interaction with individuals. Given that the dataset contained no sensitive or individual-level information, and no human subjects were involved, formal Institutional Review Board (IRB) or ethics committee approval was not required for this research.

2.1. Unit of Analysis

The unit of analysis for this study is the XYZ Government Financial Regulator, a government entity responsible for overseeing financial markets. The XYZ Government Financial Regulator is responsible for regulating and supervising the financial sector, having been in operation since the early 1990s. With a workforce of approximately 800 employees, the XYZ Government Financial Regulator ensures stability, transparency, and trust in the financial system of its jurisdiction. As a public organization, it operates within a government-controlled environment, subject to an annual budget. The research examined the roles of senior leadership, technical professionals, and end-users within the XYZ Organization using internal documentation and system-level data. These materials reflected organizational practices that did not involve direct interaction with individuals or the use of personally identifiable information.

2.3. Data Collection

Data collection for this case study involved a multifaceted approach. Internal project documentation, including project plans, technical specifications, meeting minutes, progress reports, and evaluation reports, underwent a thorough analysis to provide a detailed record of the AI development and implementation process. The analysis captured decisions, challenges, and solutions.

Below is a detailed inventory of the data collected:

System logs and performance data were examined to assess the effectiveness of AI solutions in real-world scenarios. The data revealed insights into user adoption and system accuracy, highlighting potential areas for improvement. Furthermore, users' responses to AI systems were gathered through various channels, including feedback forms and formal and informal discussions. The user feedback offered insights into the usability, effectiveness, and overall impact of AI solutions on daily operations. The documents shown in

Table 1 cannot be shared or cited publicly due to confidentiality constraints.

Furthermore, relevant literature reviews, industry reports, and best practice guidelines for AI implementation in public contexts were reviewed to contextualize the XYZ Government Financial Regulator's approach and identify potential areas for improvement. The secondary data analysis benchmarked the XYZ Government Financial Regulator's AI integration efforts against established standards and industry best practices.

2.3. Data Analysis

The data was analyzed using a combination of qualitative and quantitative techniques. Qualitative analysis involved thematic coding of project documentation, field notes, and user feedback to identify recurring patterns, themes, and critical findings (Morgan, 2022). Moreover, quantitative analysis was employed to examine system logs and performance data, assessing the impact and effectiveness of AI solutions (He et al., 2021).

The analysis combined DELVE and Azure Cloud tools for both qualitative and quantitative analysis, aiming to produce a comprehensive understanding of the data while maintaining analytical rigor. DELVE was utilized to analyze project documentation, meeting minutes, and user feedback forms for qualitative research purposes (Paulus, 2023). The software’s choice aligns with recent research advocating the use of AI as an aid for reflexive thematic analysis, expanding the scope and detail of the study (Christou, 2024).

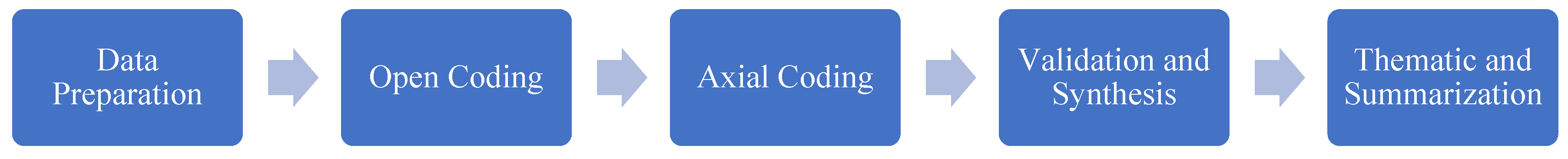

Using DELVE as a basis for qualitative analysis, the following step-by-step protocol describes the process used to ensure a rigorous examination of the gathered data. It also organizes the stages, from the initial preparation of the data to thematic synthesis, in which recurring themes and patterns were identified and validated. For the qualitative analysis, the following steps were taken:

First, data were prepared through a document review to ensure relevance, systematize source documents, and format them to facilitate analysis. Second, themes were identified based on initial thematic coding or open coding using DELVE. They included governance challenges and gaps in user training. Third, axial coding facilitated the analysis by refining these themes and connecting them to broader patterns, with a focus on their impact on system performance and adoption rates. Fourth, the coded data were validated against AI-assisted outputs and manual interpretations to ensure rigor and consistency (Trainor & Bundon, 2021). Feedback from peers and iterative reviews also improved reliability and reduced possible bias. Fifth, thematic summaries and frequency analyses were generated using DELVE to present critical findings and their implications.

The step-by-step process is illustrated in

Figure 1, providing a visual representation of the qualitative analysis workflow.

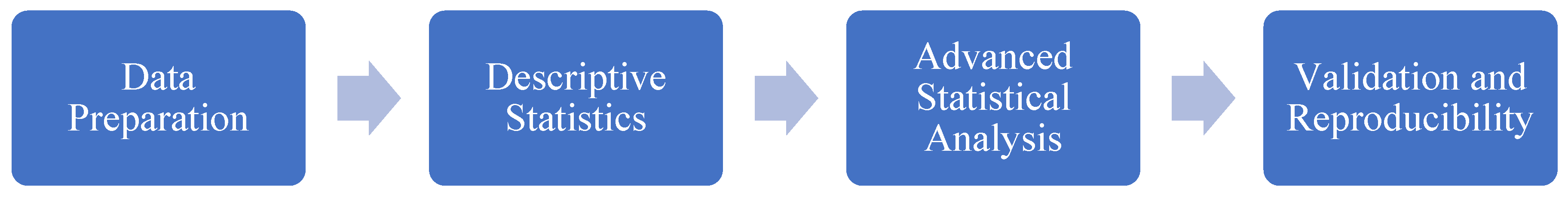

Quantitative analysis was conducted on structured datasets, which included system logs and performance metrics. In Step 1, datasets were cleaned and normalized with Azure Data Studio and Azure Data Factory. Missing values were addressed, and outliers were identified to ensure the reliability of subsequent analyses (Piastou, 2021). In Step 2, descriptive statistics were summarized to determine baseline performance indicators, including precision rates, task completion times, and error frequencies. In Step 3, advanced statistical analysis was carried out within the Azure Machine Learning environment. The statistically significant performance improvements observed after implementing AI solutions were captured through hypothesis testing. This step also developed predictive models to identify effects on system effectiveness, such as how data quality affects the accuracy rates. In Step 4, cross-validation techniques were applied to confirm the robustness of the predictive models. Through version controls on Azure DevOps, the reproducibility and reliability of the results were ensured (Haibe-Kains et al., 2020).

Figure 2 depicts the step-by-step process for the quantitative analysis:

The study employed a combination of qualitative and quantitative analyses to provide a comprehensive understanding of the XYZ Government Financial Regulator's AI adoption process. In this regard, qualitative themes regarding the importance of user training were supported by quantitative evidence showing notable correlations between increased training hours and improvements in system accuracy. This is because AI technologies require technical knowledge that most collaborators within these organizations lack (Jarrahi et al., 2023).

3. Results: AI Integration Through the Lens of Dynamic Capabilities

The government entity, the XYZ Government Financial Regulator, has embarked on a journey to integrate Artificial Intelligence (AI) into its operations, driven by the potential for efficiency gains and enhanced public effectiveness. The XYZ Government Financial Regulator's approach features a multi-phased framework that emphasizes careful planning, controlled experimentation, and continuous improvement.

3.1. Sensing: Assessing Readiness and Scanning Opportunities

This section presents the results aligned with the organization’s sensing capability, which involves identifying technological trends, assessing internal readiness, and scanning for strategic opportunities to implement AI.

3.1.1. Assessment of Technological Maturity and Organizational Readiness

The assessment of the XYZ Government Financial Regulator's existing technological infrastructure, personnel capabilities, and organizational culture provided actionable insights. The analysis revealed a solid foundation for AI adoption, characterized by a positive organizational culture that valued innovation and actively embraced new technologies. In data collected from 800 employees across various departments, summarized in evaluation reports, 82% of respondents expressed confidence in the XYZ Government Financial Regulator's ability to implement AI solutions, despite most respondents having mixed ideas about what AI meant. However, the assessment also identified areas for improvement, including the need for enhanced training and clear ethical guidelines. For instance, in an evaluation report, a user commented, “We believe that this training is essential for developing skills and updating knowledge in our area.” Another emphasized the importance of integrating ethical and transparency aspects, stating: “Finally, we are awaiting the updates to the XYZ Government Financial Regulator 's code of ethics and integrity so that the aspects of ethics and transparency in Artificial Intelligence (AI) can be integrated, as discussed in recent communications with the Human Resources Department.”

In addition, an evaluation report highlighted aspirations to align organizational changes with sustainable and responsible practices. For example, one response suggested: “Develop an online and data-driven supervision system, which, with a new organizational structure and well-being for all collaborators, will promote a sustainable, responsible, and developed financial system.”

The technological review highlighted the need for modernizing legacy systems. Only 60% of the XYZ Government Financial Regulator’s systems met the requirements for real-time data integration, indicating that the organization needed to upgrade its software and data analysis tools to support the incorporation of AI solutions. An evaluation report noted, "We need to map the current digital and technological structure. To propose a clear structure for the development and maintenance of analytical products and data management (policies, structure, processes, and controls), a phased approach to data analytics is required, starting at 20% completion and set to conclude by February 25,” underscoring the incremental nature of the organization’s efforts. Additionally, the skills assessment from the user feedback forms revealed a gap in AI-specific knowledge among the existing workforce. One participant remarked, “We consider this training essential for developing skills and updating our technical knowledge in this area,” indicating that fewer than 30% were proficient in AI-related tools and techniques, which prompted the development of targeted training programs and plans for talent acquisition in specialized AI domains.

The XYZ Government Financial Regulator took actionable steps to address the identified challenges. The measures included investments in upgrading infrastructure, establishing partnerships with technology providers for knowledge transfer, and launching training programs to upskill staff in AI-related areas. This technological and organizational assessment demonstrates the sensing capability, whereby the XYZ Government Financial Regulator scanned its internal data and culture to assess its readiness for AI adoption.

3.1.2. Development of a Robust Data Architecture

Data plays a critical role in AI initiatives. Meeting minutes records show that the XYZ Government Financial Regulator prioritized the development of robust and scalable data architecture: “Developing a scalable data architecture was emphasized to ensure seamless integration and management of diverse data sources, with the organization further enhancing this effort by migrating all its data to a secure cloud environment in partnership with a recognized technological company.” The technical specifications documents demonstrate how the technological architecture facilitated the orchestration of diverse data and systems. The architecture enabled the integration, management, and analysis of various data types, including structured data from relational databases, unstructured data such as emails and documents, and real-time data captured via application programming interfaces (APIs).

As shown in

Table 2 below, the implementation of this architecture involved several key data management strategies:

The data management strategy table considered the information originated in technical specifications as these documents describe the ETL tools, the hybrid storage platforms and their implementation: by consolidating the data from key systems across the financial sector into unified formats’, and combining the scalability of cloud storage with the security of on-premises solutions to manage financial sensitive data effectively in a hybrid way’.

The evaluation and progress reports discuss the advancement and effectiveness of data integration and processing platforms. The evaluation reports note that: “data integration efforts have reduced retrieval times by 25% and improved data accuracy across operational systems.” A progress report includes insights into governance frameworks and security measures: “Before implementing any system or process that uses Artificial Intelligence (AI) or any advanced technology for processing personal data, a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) must be conducted. The purpose of this assessment is to identify potential risks to the rights and freedoms of data subjects and establish measures to mitigate them effectively.” The proposed redesign of data pipelines and governance frameworks emerged during the sensing phase, as the organization evaluated how to prepare for the integration of scalable AI. These insights informed future reconfiguration efforts by identifying the foundational data infrastructure needed to support AI systems in regulated environments.

3.1.3. Identification of Specific Use Cases

An iterative and collaborative process was undertaken with 80 participants to identify specific AI use cases that aligned with the XYZ Government Financial Regulator's strategic objectives and offered the potential for significant impact. The meeting minutes shed light on specific use cases, including ideation sessions with stakeholders across various departments, workshops to brainstorm potential applications, and thorough feasibility analyses of each use case. For example, one recorded initiative states that the XYZ Government Financial Regulator seeks various AI-based solutions to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of its processes. These initiatives aim to optimize the detection of irregularities in financial transactions, improve communication on innovation topics, evaluate money laundering and terrorism financing risks (ML/TF) more precisely, and analyze authority comments to identify duplications or discrepancies.”

3.2. Seizing: Piloting AI Solutions and Resource Allocation

This section presents findings related to the organization’s seizing capability, its ability to act on identified opportunities by mobilizing resources, initiating pilot projects, and testing AI solutions in controlled environments.

3.2.1. Final Selection of Use Cases

The selected AI use cases encompassed a wide range of applications, as seen in

Table 3:

The use cases were selected based on their potential to address critical challenges, increase operational efficiency, enhance governance effectiveness, improve visibility into market fluctuations, and deliver tangible benefits to stakeholders. In addition, each use case underwent evaluation during development and user acceptance testing within controlled sandbox environments. The collaborative ideation workshops reflect the organization's ability to seize opportunities, as it mobilized cross-functional teams to capture strategic AI opportunities.

3.2.2. Pilot Projects in Sandbox Environments

The sandbox environments, as detailed in the evaluation reports, “are secure and flexible platforms that allow for testing solutions while safeguarding sensitive data and promoting public-private collaboration.” They proved invaluable in the early identification of inconsistencies and issues within the data pipeline. Working in a sandbox environment helps mitigate risks and ensure the smooth deployment of AI prototypes before migrating to production environments. A meeting minute highlighted the importance of sandbox environments in addressing high-priority issues with significant potential, while driving public agility and enhancing government processes. Moreover, a progress report illustrated how “the secure and flexible sandbox platform allowed for the testing of solutions using anonymized and synthetic data, ensuring data protection while fostering public-private collaboration and innovation.” Extensive testing within these controlled environments enabled the identification and resolution of technical issues, data discrepancies, and potential biases. One system log entry stated: “Detected anomalies during sandbox testing reduced data discrepancies by 15% and improved response times for AI model outputs by 25%, ensuring readiness for production deployment.” Furthermore, during chatbot testing, “the XYZ Government Financial Regulator identified and resolved data pipeline issues that improved response accuracy by 15%”. From a user perspective, highlighted in users feedback forms, the sandbox environments “facilitated the collection and analysis of critical user input to refine AI systems, user interfaces, and data pipelines.” Hence, the sandbox experiments are a concrete form of seizing, allowing the XYZ Government Financial Regulator to deploy resources in controlled settings before full rollout.

3.2.3. Iterative Feedback and Refinement

The XYZ Government Financial Regulator developed a robust feedback loop mechanism that enhanced the implementation of the AI solutions. This included gathering comments from users, technical experts, and various sources, such as documents, focus groups, and routine review meetings. The feedback process was reproduced for multiple topics, common problems, opportunities for improvement, and other areas for enhancement. The data collected from the users’ feedback forms and informal discussions provided insights into users’ preferences, their main issues when using apps and services, their expectations, and their perceptions regarding the accuracy of specific tools. One feedback form noted: “The interface needs to be more intuitive to support efficient task completion.” Moreover, an informal discussion participant remarked, “AI solutions need to provide more accurate and user-friendly interfaces to better align with our operational needs and expectations.” Furthermore, an evaluation report noted that: “Redesigning the legal assistance interface improved its usability rate from 40% to 80% across the organization.” Consequently, this organizational information enabled the team to improve the AI algorithms and facilitate user adoption.

As exemplified above, the feedback loop remained essential to the XYZ Government Financial Regulator’s expansion of AI functionalities and solutions. It also created more responsive AI solutions, whereby the tools could be adjusted based on user comments, performance, and overall adherence to the set of policies included in the early versions of the application. The continuous loop of user and technical feedback strengthened the XYZ Government Financial Regulator’s seizing capability by refining AI applications through real-world insights. This feedback mechanism informed the iterative adjustment of algorithms, user interfaces, and operational processes. While formal reconfiguration would occur at a later stage, these early learnings played a critical role in shaping scalable solutions and preparing the groundwork for institutional integration.

3.3. Reconfiguring: Institutionalizing AI Through Structural Change.

The final set of findings reflects the organization’s reconfiguring capability, i.e., its efforts to embed successful AI initiatives into institutional structures, processes, and culture.

3.3.1. Evaluation and Full-Scale Implementation

The first versions of the AI systems were checked thoroughly after a complete cycle of iterations to determine their readiness for large-scale testing. This evaluation process included qualitative and quantitative assessments. Evaluation reports and system logs provided quantitative assessments of AI tools: “key performance metrics, including accuracy, precision rate, recall rate, and F1 scores, were utilized to benchmark the effectiveness of AI tools in classification tasks,” “the F1 score averaged 92% across tested applications, demonstrating the model’s high accuracy as seen in the system logs.” These metrics were crucial for assessing the readiness of AI systems for large-scale deployment.

In addition to performance metrics, quantitative information was collected through user meeting minutes and automated annotation processes to create a 360-degree view of the AI system’s capability, efficiency, and performance within a user-centric design. The meeting minutes highlighted that users provided valuable insights into system functionality and usability, suggesting improvements to enhance organizational alignment with operational needs. Within this framework, it is crucial to understand the key elements necessary to achieve a high level of client satisfaction.

The development team focused on responsible and ethical AI as a key component of the government compliance review. The assessment included technical details concerning the explicability of AI models, leveraging results from the causal analysis of selected data and identifying possible biases and other unforeseen effects during the early stages of development. Additionally, the analysis included an assessment of the effectiveness of AI systems in mitigating cyber threats and data breaches through security audits, penetration testing, and the calculation of risks associated with the deployment of AI technologies.

Using the readiness assessment of each component of the AI system, the XYZ Government Financial Regulator identified the most effective path to migrate a specific tool from a development environment to an enterprise version. The selected dimensions included performance, usability, public compliance, and security. The primary objective was to design a system implementation plan for each application that met these criteria. The action plan for expanding the AI systems and frameworks included resource distribution, employee training, and oversight details.

The enterprise implementation of the AI systems was based on resource planning, user training, integration, reporting, and evaluation. The XYZ Government Financial Regulator also adopted change management strategies to adequately prepare staff for introducing AI systems and minimizing potential workflow disruptions. Accordingly, the XYZ Government Financial Regulator prioritized those applications with the highest operational impact, as seen in the economic example in the

Appendix A of this document. The use of performance metrics (e.g., F1 scores, precision rates) to decide on enterprise-level rollout demonstrates the final reconfiguring step, i.e., aligning organizational structures around proven AI solutions.

3.3.2. Development of an AI Implementation Roadmap

The XYZ Government Financial Regulator recognized that AI adoption requires a long-term commitment and a roadmap to guide future initiatives. Project plans and progress reports outlined the development of an AI implementation roadmap focused on performance optimization, workforce development, and government compliance. Project plans showed: “key dimensions such as performance optimization, workforce development, and ensuring public fulfillment through structured milestones and goals." In addition, progress reports further detailed that the XYZ Government Financial Regulator prioritized: “collaboration with multilateral organizations to benchmark practices and align with international standards.” Moreover, the evaluation reports highlighted the XYZ Government Financial Regulator's efforts, stating that “long-term investment in talent acquisition, continuous training, and infrastructure enhancement forms the backbone of the organization’s AI ecosystem.” As shown in

Figure 3, it developed comprehensive AI implementation guidelines that outline a strategic vision for the continued integration of AI into the XYZ Government Financial Regulator's operations.

The XYZ Government Financial Regulator remains proactive in defining additional areas for AI applications to improve operations. The XYZ Government Financial Regulator established an R&D division to track trends, methods, and applications of AI-based technologies. R&D benchmarks internal practices using a subset of multilateral organizations with government responsibilities worldwide. The XYZ Government Financial Regulator understood that systematic investment in people and facilities is compulsory to support the development of the AI ecosystem. Consequently, there was significant investment in the AI staff, continuous professional development, and enhanced technology infrastructure support for AI initiatives. To illustrate, the roadmap focuses on three key dimensions: performance optimization, user adoption, and government conformity. First, performance optimization involves creating measurable outcomes, such as achieving a 90% classification accuracy rate. Second, the roadmap emphasizes workforce development, setting a target of 90% of employees trained within two years. Lastly, regular audits and internal AI documents will enhance transparency and fairness. Other complementary activities included signing collaboration agreements between the XYZ Government Financial Regulator and other public sector agencies, advanced learning institutions, local industries, and other relevant parties to exchange information and develop joint research activities. Establishing dedicated “centers of excellence” and recognition programs embodies the reconfiguring capability, which means realigning organizational structures, incentives, and cultural norms to support continuous AI experimentation and knowledge sharing.

3.3.3. Fostering a Culture of Innovation and Experimentation

The decisive element in the success of new technology implementations was continuous experimentation, which the XYZ Government Financial Regulator promoted as a primary step in the process. It achieved this by combining various strategies, including extensive training for personnel across the organization, a horizontal organizational structure, increased technical roles, and the development of soft skills such as problem-solving and critical thinking. As seen in the evaluation reports, the XYZ Government Financial Regulator developed a specialized training program that increased employee receptiveness and supported the organization’s innovation agenda: “enhancing employee receptiveness to AI-driven projects and aligning workforce capabilities with the organization’s innovative strategic approach.”

In addition, the project plans documentation highlighted how the organization established three centers of innovation and excellence, where the staff is free to experiment with AI technologies: “the centers’ focus is to empower staff to experiment with advanced technologies and methodologies.” In addition, informal discussions revealed the way these centers promoted innovation, testing new ideas and configurations while giving the users tools to experiment using actual data without interfering with operations, as participants revealed: “Establishing governance rules centered on data security and compliance within the Centers of Excellence (CDE) ensures the organization effectively manages the influx of new AI tools and technologies while maintaining interoperability, security, and cultural fit.” “These centers provide the necessary tools and resources for experimenting with AI technologies, fostering creativity without disrupting regular operations.” The XYZ Government Financial Regulator has also established internal programs to recognize employees or teams for outstanding efforts in developing or applying AI tools, reinforcing a culture of creativity.

More time is needed to examine the effects of the AI integration initiative; however, some preliminary findings have been identified. With the assistance of artificial intelligence, the XYZ Government Financial Regulator initiated the automation and optimization of several internal processes, thereby reducing workloads and enhancing accuracy in tasks such as document analysis, classification, and data entry. AI applications, particularly chatbots in customer service support, have reduced response times, increased customer satisfaction, and lowered the cost of providing 24/7 service.

For public sector agencies, ML tools have demonstrated high accuracy, resulting in cost-effective solutions for monitoring potential threats and minimizing financial losses. In addition, state-of-the-art generative technologies have shown promise for the execution of government reports, compliance evaluations, and an acceptable error rate in analyzing government and legal documents. The use of machine learning (ML) and combined ML-LLM frameworks for forecasting has the potential to enhance risk prevention, enabling the XYZ Government Financial Regulator to minimize threats to its financial stability.

Figure 4 presents the integrated framework of AI discussed above. It suggests an approach that uses a multiple-phase model for government entities. In this setting, every phase involves a controlled and secure process for applying AI in operations.

Nonetheless, the XYZ Government Financial Regulator acknowledges that these preliminary results necessitate further testing and evaluation before implementing AI-powered tools in other processes. The XYZ Government Financial Regulator plans to keep the existing AI roadmap implementation plan and monitor, evaluate, and adjust the AI systems to maximize its target outcomes and achieve its strategic vision.

4. Discussion

Through benchmarking the XYZ Government Financial Regulator’s AI integration roadmap against global best practices and strategic management literature, we have identified how its sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring activities align with and extend established Dynamic Capabilities and Resource-Based View constructs. While the government's financial regulator demonstrates robust progress in pilot experimentation and data governance, the analysis also reveals critical gaps in workforce readiness and system modernization that require attention to realize governance and operational effectiveness fully.

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

The analysis confirms the applicability of Dynamic Capabilities theory to public-sector AI adoption while revealing important extensions. In particular, the deployment of sandbox environments emerges as a formal seizing mechanism, allowing government agencies to marshal resources and validate innovations within regulated boundaries—a nuance largely absent from private-sector accounts (Teece, 2007; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). Moreover, elaborating governance routines, manifested in comprehensive data architectures and codified ethical frameworks, constitutes a distinctive reconfiguring capability. These routines realign organizational structures, processes, and normative expectations to embed AI at scale, integrating compliance checkpoints directly into the capability cycle. This insight extends existing theory by highlighting how public agencies must interweave regulatory compliance with dynamic reconfiguration to sustain innovation (Hart & Milstein, 2003).

The benchmarking analysis also highlights the XYZ Government Financial Regulator’s leadership in innovative practices. One example is the creation of centers of excellence to jumpstart experimentation. These centers enabled staff to experiment with AI tools in a way that would not disrupt existing workflows, fostering a culture of innovation. A 40% increase in successful AI prototypes, from sandbox experimentation to production environments, demonstrates the potential of these centers.

The XYZ Government Financial Regulator demonstrated its ability to integrate the most up-to-date technological developments, such as machine learning and large language models (ML-LLMs), into its governance and compliance activities. ML models reached 92% accuracy in recognizing compliance risks, and generative AI tools decreased the duration of adherence evaluations by 30%. These achievements align with international trends in AI applications for governance efficiency (Mehrabi et al., 2021) and demonstrate the XYZ Government Financial Regulator's capability for technological innovation.

4.2. Managerial and Generalizable Lessons

Several strategic imperatives emerge for government bodies to replicate this regulator’s success. First, formalizing controlled experimentation through sandbox environments is essential: such pilots mitigate risk and generate the experiential knowledge needed to inform subsequent rollouts. Second, aligning data governance with early sensing activities ensures that ethical and compliance considerations guide opportunity identification from the outset. Third, investing in VRIN resources, specialized talent, domain expertise, and robust data stewardship establishes the human- and resource-based foundations for durable AI adoption (Barney, 1991; Prahalad & Hart, 2002). Ultimately, institutionalizing iterative feedback loops enables the continuous reconfiguration of algorithms, interfaces, and workflows, thereby accelerating learning and refinement. These lessons provide a replicable, dynamic capabilities framework for public agencies seeking to leverage AI for enhanced operational efficiency and broader development objectives.

Nonetheless, there are organizational practices that could be improved, including a gap in workforce readiness for AI adoption. The XYZ Government Financial Regulator initiated training programs; however, survey data revealed that 28% of staff felt unprepared to utilize AI tools effectively. This proves the need for more systematic training programs. Benhamou (2020) emphasizes that AI-specific skill development is crucial for successful integration; the XYZ Government Financial Regulator could enhance its performance in this area by developing high-throughput, advanced training modules tailored to its operational context.

Another challenge is that legacy systems are still in use, and they are not yet sufficiently scalable or efficient. As of July 2024, the XYZ Government Financial Regulator has only completed 60% of its core system upgrades. Due to this delay, the integration of real-time data processing has been limited. Public agencies in the European Union exemplify that early investment in full-scale modernization leads to faster AI deployment and better data-driven decision-making (Financial Stability Board, 2019).

The benchmarking process offers several strategic implications. First, addressing identified gaps—particularly workforce readiness and system modernization—will be essential for sustaining the XYZ Government Financial Regulator’s progress. Second, advanced training programs are crucial for targeting specific AI competencies, while infrastructure investments must prioritize replacing legacy systems with innovative tools to enhance organizational scalability and efficiency. Additionally, the XYZ Government Financial Regulator could establish partnerships with leading public bodies and academic institutions to exchange knowledge and expertise.

The expected benefits and initial observations indicate that integrating artificial intelligence into legal frameworks necessitates a controlled and rigorous approach. Working within sandboxes helps identify issues before implementing certain activities or processes on a large scale. This applies to many government organizations that seek to deploy artificial intelligence tools, ensuring that the solutions are ethical, efficient, secure, and user-friendly (Bostrom & Yudkowsky, 2018).

The expected benefits of applying AI in this study support the development of enterprise solutions that other government authorities can replicate and build upon. Adhering to the proposed framework helps these public sector organizations realize the benefits of AI. The findings support a process in which specific steps can be executed simultaneously, depending on the level of maturity of the government organization. We recommend a sequential and iterative approach for organizations new to these technologies. In addition, it is possible to advance various operational areas through well-planned AI implementation (Kim, 2019; Rane, 2024), thereby reducing the impact that poor implementation can have on the desired outcome and promoting the efficient use of AI in government agencies and public entities.

5. Conclusions

By applying Dynamic Capabilities theory, this paper demonstrates how a financial regulator can systematically identify AI opportunities, capitalize on them through pilot projects, and reconfigure its organizational structures to facilitate scalable innovation. These insights extend strategic management frameworks into public sector domains, providing a replicable model for institutional adoption of AI.

For public sector organizational leaders and policymakers, the framework emphasizes the importance of integrating AI in a staged approach. Organizational evaluations at the onset of technological maturity and managerial readiness provide the basis for developing solutions tailored to specific needs. Adhering to a proper data structure enhances data organization and security, which is essential for supporting AI-based analytics and decision-making. Consequently, technical teams should prioritize building robust data architecture utilizing hybrid cloud solutions for secure data storage, adopting ETL tools for data integration, and establishing data governance frameworks.

Top management's understanding of high-priority scenarios promotes the use of AI in areas with the highest expected, derived value, providing maximum benefit, such as improving customer satisfaction, explaining results in repetitive functions, reinforcing risk control, and ensuring compliance. Therefore, organizational leaders should create sandbox environments for piloting AI solutions to mitigate risks and ensure the efficiency of AI solutions before widespread adoption.

Enhancing organizational culture is at the heart of practical AI implementation. Managers within government entities should introduce training to help workers and companies innovate, establish so-called Sandbox Labs, and create incentives to encourage workers to experiment and share their knowledge with colleagues. Proactively supporting innovation enables organizations to navigate a constantly changing environment.

Trust is crucial for utilizing AI with transparency, fairness, and security. Explainable AI models, flexible and robust data governance, and monitorability are essential to supporting AI systems that comply with ethical and legal norms. Such measures also help build public confidence.

The implementation details in this case study should serve as a valuable reference for other authorities and government departments seeking to unlock AI's potential. By following the same procedural approach, these entities can utilize AI to optimize their organization, thereby enhancing the efficiency of governance and innovation in public sector administration.

Several caveats apply to the findings of this analysis. Certain limitations in the case study could influence the conclusions and generalizations drawn from the outcomes. The findings may be limited in some respects, particularly regarding the government body under consideration, due to its unique structure. The lasting effectiveness of AI solutions and the impact of outside forces are other areas that need further research.

Although the study utilized various data sources, it faced constraints in accessing some restricted information due to data privacy procedures. It implemented data collection through questionnaires completed at the discretion of the surveyed entity, which might result in bias. Moreover, the study maintains a long-term view of the benefits of applying AI tools; it has limited analysis of the implementation's short- to medium-term impact and resource ramifications.

Future research should focus on comparative studies across regions with disparate technological and governing maturity. In addition, studying the effects of long-term transparency and integrity initiatives powered by AI in public sector entities, such as public utilities and public sector agencies, globally will further determine how AI can help prevent corruption. Such studies must focus on proximate effectiveness metrics, such as how AI tools mitigate risks, enhance efficiency, and foster public trust.

Future research should also explore how data analytics and MLM can assist public organizations in making informed decisions about complex compliance issues, detecting fraudulent activities, and adhering to evolving international standards. By incorporating these sectors into AI research, it is possible to integrate human elements into the governing frameworks, thereby enhancing governance across diverse economic sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Carlos Merlano and Luis Arregoces; Methodology, Carlos Merlano and Luis Arregoces; Formal analysis, Carlos Merlano and Luis Arregoces; Investigation, Carlos Merlano and Luis Arregoces; Writing—original draft preparation, Carlos Merlano and Luis Arregoces; Writing—review and editing, Carlos Merlano, Luis Arregoces, Lisa Bosman and Monica Gamez-Djokic; Supervision, Lisa Bosman; Project administration, Carlos Merlano and Luis Arregoces. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Given that the dataset contained no sensitive or individual-level information, and no human subjects were involved, formal Institutional Review Board (IRB) or ethics committee approval was not required for this research.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Appendix A. Example of an AI Use Case implementation in the XYZ Organization

The following AI use case study highlights the potential costs and benefits of implementing an initiative within a government entity following the AI integration framework discussed above. As mentioned in the methodology section, the data was collected from internal records, evaluation reports, and measurements taken during the model's pilot phase. Some of the values were changed due to data privacy concerns. However, they showcase what to expect when implementing an AI model processing recently collected field data from supervised entities.

Use Case

Evaluating a Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (ML/TF) database with vectorization and a generative AI model. This initiative aimed to assess ML/TF risks more accurately using AI technological tools. The initiative achieved greater consistency in risk assessment, with a model precision of 97% and variability reduction of 82%, providing a more precise and reliable view of risk areas. Precision is calculated as shown in the following formula:

\[ \text{Precision} = \frac{\text{True Positives}}{\text{True Positives} + \text{False Positives}} \]

Where:

True Positives (TP): Cases where the model correctly identifies a legitimate ML/TF risk.

False Positives (FP): Cases where the model incorrectly flags a non-risk as a risk.

A precision of 97% means that out of all the risks flagged by the AI model, 97% were actual ML/TF risks, while 3% were false alarms.

On the other hand, Variability Reduction is as follows:

\[ \text{Variability Reduction (\%)} = \left( \frac{\text{Initial Variability} - \text{Final Variability}}{\text{Initial Variability}} \right) \times 100 \]

Where:

Initial Variability: Measured by assessing the inconsistency in risk assessments before implementing the AI model. This could involve analyzing risk score variance or standard deviation across different assessor inputs.

Final Variability: Measured similarly, but after implementing the AI model.

An 82% reduction in this case indicates that inconsistencies in risk assessments have dropped significantly, leading to a more stable and reliable evaluation process.

Additionally, it provided a reliable model that has improved risk evaluation.

Table A1.

Total investments and costs.

Table A1.

Total investments and costs.

| Concept |

Type |

Value in USD (Thousands) |

| Initial data investment |

Initial investment |

30,000 |

| Data accessibility and quality |

Initial investment |

20,000 |

| Involvement of subject matter experts (SMEs) |

Initial investment |

150,000 |

| AI model development |

Initial investment |

100,000 |

| Staff training |

Initial investment |

10,000 |

| Total Investment |

|

310,000 |

| Cloud computing |

Recurring cost |

50,000 |

| Data storage |

Recurring cost |

5,000 |

| Model monitoring and maintenance |

Recurring cost |

15,000 |

| Software licenses |

Recurring cost |

10,000 |

| Total Costs |

|

80,000 |

As the table shows, the most essential initial investments are AI model development and the involvement of subject matter experts, with values of $100,000 and $150,000, respectively. Concerning the operational costs, the most representative are model monitoring and maintenance, software licenses, and cloud computing, with values of $15,000, $10,000, and $50,000, respectively.

Table A2.

Benefits.

| Concept |

Type |

Value in USD (Thousands) |

| Operational cost savings and productivity |

Benefit |

212,500 |

| Total Benefits |

|

212,500 |

Implementing the AI model for ML/TF risks brings clear benefits, like saving costs and boosting productivity. By automating routine tasks, legal professionals can redirect 20%- 30% of their time to meaningful work, such as advising clients or tackling complex cases. Daily operations become smoother, and the organization stays on top of public administrative requirements with less effort.

ROI.

The Return on Investment (ROI) for the ML/TF risks project is 42.74%. The ROI formula is as follows:

\[

ROI = \frac{\text{Net Profit}}{\text{Investment}} \times 100

\]

Where:

Net Profit: Represents the gain from the investment, calculated as Total Revenue minus Total Costs.

Investment: This is the amount initially invested in the AI project.

×100: This converts the ROI value into a percentage.

For this project, the ROI is substantial. However, this has not been the case for every AI project. Many projects do not even surpass the test and pilot phases, which agrees with Gartner (2024) that at least 30% of AI projects do not go further than the initial phases. Moreover, as with most technologies, AI projects will not succeed just by investing considerable resources and deploying them in the organizations; they require a methodological approach. Nevertheless, strictly following the framework does not guarantee that AI projects will be successful. Still, it will guide organizations in evaluating whether any projects are worth the risk and cost of full deployment and whether they generate value for the organization.

References

- Adam, M., Wessel, M., & Benlian, A. (2020). AI-based chatbots in customer service and their effects on user compliance. Electronic Markets, 30(4), 497-514. [CrossRef]

- Aderibigbe, A. O., Ohenhen, P. E., Nwaobia, N. K., Gidiagba, J. O., & Ani, E. C. (2023). Artificial intelligence in developing countries: bridging the gap between potential and implementation. Computer Science & IT Research Journal, 4(3), 185-199. [CrossRef]

- Agbese, M., Mohanani, R., Khan, A., & Abrahamsson, P. (2023, June). Implementing ai ethics: Making sense of the ethical requirements. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering (pp. 62-71). [CrossRef]

- Ångström, R. C., Björn, M., Dahlander, L., Mähring, M., & Wallin, M. W. (2023). Getting AI Implementation Right: Insights from a Global Survey. California Management Review, 66(1), 5-22. [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C., Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic as a game changer for public administration and leadership? The need for robust governance responses to turbulent problems. Public management review, 23(7), 949-960. [CrossRef]

- Arner, D. W., Barberis, J., & Buckey, R. P. (2016). FinTech, RegTech, and the reconceptualization of financial regulation. Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus., 37, 371.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of management, 17(1), 99-120. [CrossRef]

- Benhamou, S. (2020). Artificial intelligence and the future of work. Revue d'économie industrielle, (169), 57-88.

- Bostrom, N. (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, dangers, strategies. Oxford University Press.

- Bostrom, N., & Yudkowsky, E. (2018). The ethics of artificial intelligence. In Artificial intelligence safety and security (pp. 57-69). Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Broeders, D., & Prenio, J. (2018). Innovative technology in financial supervision (suptech): The experience of early users. Financial Stability Institute/Bank for International Settlements.

- Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2016). The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Cath, C. (2018). Governing artificial intelligence: ethical, legal and technical opportunities and challenges. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 376(2133), 20180080. [CrossRef]

- Cath, C., Wachter, S., Mittelstadt, B., Taddeo, M., & Floridi, L. (2018). Artificial intelligence and the ‘good society’: the US, EU, and UK approach. Science and engineering ethics, 24, 505-528.

- Cha, S. (2024). Towards an international regulatory framework for AI safety: lessons from the IAEA’s nuclear safety regulations. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Balan, M. M., & Brown, K. (2023). Language models are few-shot learners for prognostic prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.12692.

- Christensen, T., & Lægreid, P. (2020). Balancing governance capacity and legitimacy: how the Norwegian government handled the COVID-19 crisis as a high performer. Public Administration Review, 80(5), 774-779. [CrossRef]

- De Santis, F. (2024). Artificial Intelligence to Support Business. Artificial Intelligence in Accounting and Auditing: Accessing the Corporate Implications, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: what are they?. Strategic management journal, 21(10-11), 1105-1121.

- Eom, S. J., & Lee, J. (2022). Digital government transformation in turbulent times: Responses, challenges, and future direction. Government Information Quarterly, 39(2), 101690. [CrossRef]

- European Union. (2019). Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/640163/EPRS_BRI%282019%29640163_EN.pdf.

- Eurostat. (2024, May 29). 8% of EU enterprises used AI technologies in 2023. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20240529-2.

- Fares, O. H., Butt, I., & Lee, S. H. M. (2022). Utilization of artificial intelligence in the banking sector: A systematic literature review. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 1. Financial Stability Board. (2019). Artificial intelligence and machine learning in financial services: Market developments and potential risks. https://www.fsb.org/2021/09/the-use-of-artificial-intelligence-ai-and-machine-learning-ml-by-market-intermediaries-and-asset-managers/.

- Floridi, L., & Cowls, J. (2022). A unified framework of five principles for AI in society. Machine learning and the city: Applications in architecture and urban design, 535-545.

- Gartner. (2024, July 29). Gartner predicts 30 percent of generative AI projects will be abandoned after proof of concept by end of 2025. Gartner Newsroom. Retrieved from https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2024-07-29-gartner-predicts-30-percent-of-generative-ai-projects-will-be-abandoned-after-proof-of-concept-by-end-of-2025.

- Haibe-Kains, B., Adam, G. A., Hosny, A., Khodakarami, F., & Aerts, H. J. (2020). Transparency and reproducibility in artificial intelligence. Nature, 586(7829), E14–E16. [CrossRef]

- Hart, S. L., & Milstein, M. B. (2003). Creating sustainable value. Academy of Management Perspectives, 17(2), 56-67.

- He, S., He, P., Chen, Z., Yang, T., Su, Y., & Lyu, M. R. (2021). A survey on automated log analysis for reliability engineering. ACM computing surveys (CSUR), 54(6), 1-37. [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. (2021). Artificial Intelligence in Finance: A Cross-Country Perspective.

- Jarrahi, M. H., Askay, D., Eshraghi, A., & Smith, P. (2023). Artificial intelligence and knowledge management: A partnership between human and AI. Business Horizons, 66(1), 87-99. [CrossRef]

- Javaid, H. A. (2024). How Artificial Intelligence is Revolutionizing Fraud Detection in Financial Services. Innovative Engineering Sciences Journal, 4(1).

- Kim, J. (2019). Case Study about efficient AI (Artificial Intelligence) Implementation Strategy. Journal of IJARBMS (International Journal of Advanced Research in Big Data Management System), 3(2), 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M. R., & Porter, M. (2011). Creating shared value (Vol. 17). Boston, MA: FSG.

- Lichtenthaler, U. (2020). Five maturity levels of managing AI: From isolated ignorance to integrated intelligence. Journal of Innovation Management, 8(1), 39-50. [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M., & Kattel, R. (2020). COVID-19 and public-sector capacity. Oxford review of economic policy, 36(Supplement_1), S256-S269. [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. (2024). The state of AI in early 2024. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai.

- Mittelstadt, B. D., Allo, P., Taddeo, M., Wachter, S., & Floridi, L. (2016). The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate. Big Data & Society, 3(2), 2053951716679679. [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, N., Morstatter, F., Saxena, N., Lerman, K., & Galstyan, A. (2021). A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM computing surveys (CSUR), 54(6), 1-35. [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I. (2019). Digital service teams in government. Government Information Quarterly, 36(4), 101389. [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I., Edelmann, N., & Haug, N. (2019). Defining digital transformation: Results from expert interviews. Government information quarterly, 36(4), 101385. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, H. (2022). Conducting a qualitative document analysis. The Qualitative Report, 27(1), 64-77. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019a). Preparing for the future of artificial intelligence. The National Academies Press.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019b). Artificial Intelligence in the Financial Services Industry: Assessing Potential Uses of Artificial Intelligence in the Financial Services Industry. National Academies Press.

- Ntoutsi, E., Fafalios, P., Gadiraju, U., Iosifidis, V., Nejdl, W., Vidal, M. E., ... & Staab, S. (2020). Bias in data-driven artificial intelligence systems—An introductory survey. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 10(3), e1356.

- Paulus, T. M. (2023). Using qualitative data analysis software to support digital research workflows. Human Resource Development Review, 22(1), 139-148. [CrossRef]

- Peng, C., van Doorn, J., Eggers, F., & Wieringa, J. E. (2022). The effect of required warmth on consumer acceptance of artificial intelligence in service: The moderating role of AI-human collaboration. International Journal of Information Management, 66, 102533. [CrossRef]

- Piastou, M. (2021). Enhancing Data Analysis by Integrating AI Tools with Cloud Computing. International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology, 13(7), 13924-13934.

- Prahalad, C. K., & Hart, S. L. (2002). The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. Strategy and business, 54-54.

- Rane, N. L., Desai, P., & Choudhary, S. (2024). Challenges of implementing artificial intelligence for smart and sustainable industry: Technological, economic, and regulatory barriers. Artificial Intelligence and Industry in Society, 5, 2-83.

- Russell, S. J., & Norvig, P. (2021). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic management journal, 18(7), 509-533.

- Teece, D., Peteraf, M., & Leih, S. (2016). Dynamic capabilities and organizational agility: Risk, uncertainty, and strategy in the innovation economy. California management review, 58(4), 13-35. [CrossRef]

- Weber, M., Engert, M., Schaffer, N., Weking, J., & Krcmar, H. (2023). Organizational capabilities for ai implementation—coping with inscrutability and data dependency in ai. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(4), 1549-1569. [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B. W., Weyerer, J. C., & Geyer, C. (2019). Artificial intelligence and the public sector—applications and challenges. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(7), 596-615. [CrossRef]

- World Bank (2022). Regulation and Supervision of Fintech: Considerations for Financial Regulators.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).