1. Introduction

In traditional spectrum allocation policies, licensed users are granted exclusive access to fixed frequency bands [

1]. However, this conventional approach has led to a spectrum scarcity issue, leaving limited available bandwidth to accommodate emerging communication needs. Furthermore, studies on spectrum usage reveal that many Primary User (PU) occupy their assigned bands for only a small portion of the time & area, resulting in significant underutilization of the spectrum.

In recent years, the demand for wireless communication has surged, often outpacing the availability of designated frequency bands. Amid this increasing pressure, innovative approaches to spectrum management have gained prominence, particularly in the context of Dynamic Spectrum Access (DSA). This technique allows secondary users to access frequency bands that are primarily allocated to license holding technologies, like satellites; radars; aerospace communications, specifically within the 3.8-4.2 GHz range. This approach allows multiple users or technologies to reuse or share radio resources, improving spectrum efficiency and increasing throughput without requiring new spectrum resources [

2].

In South Africa, terrestrial wireless mobile networks are essential for bridging the digital divide caused by vast geography, low population density in rural provinces, and economic disparities. Fibre deployment across regions like Limpopo, Kwazulu Natal, the Eastern and Northern Cape is often not cost-effective due to rugged terrain and sparse settlements [

3], making Fourth Generation of Radio Networks (4G)/Fifth Generation of Radio Networks (5G) wireless solutions a more scalable and practical alternative. Major Mobile Network Operator (MNO)s typically focus on profitable urban metros for network upgrades, leaving rural and low-income communities underserved despite their growing need for connectivity to support eHealth, eGov, digital agriculture, education, and mobile finance. Wireless access enables broader socio-economic inclusion by expanding access to government services, job markets, remote learning, and entrepreneurship. Furthermore, national policies such as Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA)’s spectrum obligations in [

1,

4] mandate universal service coverage, which wireless technologies can fulfill efficiently—especially when combined with spectrum sharing models like TV White Space (TVWS), Licensed Shared Access (LSA) or Citizens Broadcast Radio Service (CBRS). These frameworks also empower smaller operators and municipalities to deploy affordable, community-based networks. Thus, terrestrial wireless mobile infrastructure is not merely a technical solution but a strategic tool for inclusive development and equitable digital access.

By intelligently identifying and utilizing underused spectrum resources, DSA aims to enhance spectrum efficiency, a critical requirement given the finite nature of frequency allocations. This review explores the mechanisms through which DSA can be adopted and implemented in satellite environments as, critically examining its potential to mitigate spectrum scarcity while ensuring that PU as considered in [

5,

6,

7] maintain their operational integrity. Ultimately, analysis in [

2,

8,

9,

10] revealed that effectively leveraging DSA could establish a more robust communication framework, fostering both technological advancement and improved user experiences in an increasingly congested spectrum landscape. These claims raises research interest in a successful setup of 5G and Fixed Satellite Service (FSS) coexistence while considering antenna evolution in 5G New Radio (NR), in-terms of Multiple Input Multiple Output (MIMO) and Reconfigurable Interface Controller (RIC) configurations.

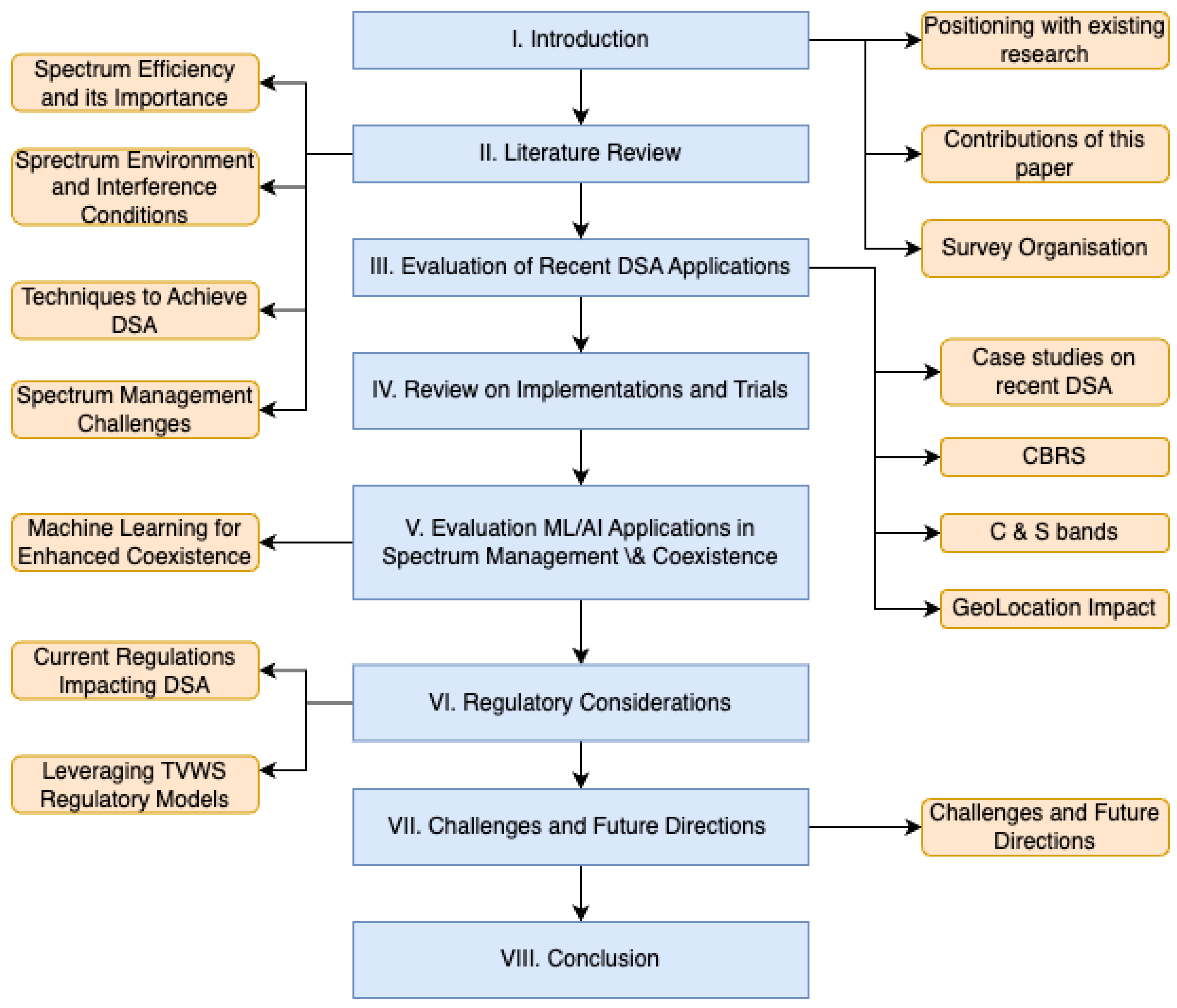

Figure 1 shows the outline of the paper.

1.1. Positioning within Existing Surveys

Existing literature in

Table 1 on Dynamic Spectrum Sharing (DSS) has laid a strong foundation across several dimensions, including spectrum coexistence, resource allocation, and policy development. For example, coexistence mechanisms and interference mitigation strategies have been thoroughly classified for cognitive radio networks in TVWS [

11,

12]. Surveys such as [

13,

14] provide insights into inter-technology coexistence frameworks and models like CBRS and LSA, while [

2,

15] highlight opportunities and challenges for spectrum sharing in 5G and Beyond 5G (B5G) environments.

A strong body of research has also emerged around Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence (ML/AI) applications for dynamic spectrum access and radio resource allocation. These include supervised and reinforcement learning-based mechanisms for efficient spectrum assignment and automation [

16,

17,

18]. Several works point to ML as a crucial tool for enhancing the intelligence and adaptability of spectrum management frameworks [

2,

15], though most of this research has focused on terrestrial coexistence among traditional wireless mobile broadband systems. However, there is limited literature that specifically addresses the coexistence between terrestrial wireless mobile networks (such as 4G, 5G New Radio (5G NR)) and terrestrial ground satellite receivers. The need to safeguard these incumbent services while leveraging dynamic spectrum access calls for new models of interference characterization and intelligent spectrum management. Therefore, this paper positions itself to fill this gap by investigating ML/AI-driven resource allocation approaches to enable efficient coexistence in DSS environments while ensuring protection of FSS/Satellite Services (SS) receiving ground stations. This approach integrates real-time learning, geolocation databases, and regulatory-aware constraints into the coexistence and spectrum reuse framework.

1.2. Contributions of This Paper

This paper contributes to the body of knowledge by proposing a systematic approach for extracting and incorporating the physical and technical parameters of FSS and SS ground stations into DSS environments. Specifically, it addresses the critical challenge of protecting satellite downlink transmissions from interference caused by nearby terrestrial mobile networks. The study outlines methods for identifying relevant FSS/SS parameters—such as antenna orientation, elevation angle, sensitivity thresholds, and geographic location—that must be integrated into spectrum management frameworks. Leveraging these parameters, the paper introduces ML/AI-driven models that enables real-time adjustment of terrestrial network transmission power, antenna beamforming patterns, and spectrum access decisions based on proximity and alignment with satellite ground receivers. This dynamic, data-informed approach enhances the coexistence between terrestrial and satellite systems by minimizing harmful interference while maximizing spectral efficiency. Ultimately, the paper provides a foundation for intelligent, location-aware, and adaptive interference management policies that support scalable deployment of mobile broadband systems. The contributions can be listed as:

A comprehensive review of DSA techniques involving coexistence between PU and Secondary User (SU).

A detailed discussion on the spectrum environment factors and interference challenges.

ML/AI insights to enhance spectrum management considering antenna technologies.

Evaluation of recent DSA implementations.

Review on Trials and regulatory factors.

Proposal of future directions

This aims to explore the most effective methods for ML/AI-based coexistence framework of DSA networks. The main research question to be answered is:

“How can ML/AI-based opportunistic spectrum access systems enhance coexistence and access accuracy in the sub-6 GHz spectrum bands, while addressing limitations and challenges of existing DSA frameworks?”

To address the above question, the following sub-questions will be answered:

What are the key limitations and challenges of current multi-network operator spectrum sharing in tiered coexistence frameworks in the different spectrum bands?

How can ML/AI algorithms such as Deep Learning (DL) and Reinforced Learning (RL) be applied to enhance spectrum access accuracy and coexistence in the sub-6 GHz bands in radically changing environment conditions in real-time?

1.3. Survey Organization

The organization of this survey, shown in

Figure 1 is structured to comprehensively address DSA with a focus on coexistence between terrestrial wireless mobile networks and satellite ground stations such as FSS/SS. The literature review section follows, covering the importance of spectrum efficiency, the spectrum environment and interference conditions, techniques to enable DSA—including cognitive radio and database-assisted sharing—and the role of ML/AI in spectrum coordination. It also examines spectrum management approaches relevant to satellite systems. Subsequent sections evaluate recent DSA applications, enablers, and frameworks/models (CBRS, TVWS, LSA), and review regional implementations and trials. This is followed by an assessment of ML/AI models used for coexistence and interference management. The survey then discusses implementation challenges and future directions, and concludes by summarizing key findings and proposing research opportunities for intelligent, satellite-aware DSA frameworks.

Figure 1.

Structure of the paper

Figure 1.

Structure of the paper

2. Literature Review

Coexistence broadly refers to the ability of multiple wireless systems or technologies with similar priorities to operate in the same spectrum band without significantly negatively impacting each other’s performance.

Table 2.

Summary of Key Literature on Spectrum Sharing, DSA, and ML-based Coexistence

Table 2.

Summary of Key Literature on Spectrum Sharing, DSA, and ML-based Coexistence

| Reference/ Journal |

Year |

Core Contributions |

Focus |

| [2] |

2020 |

Proposes ML models for spectrum-as-a-service (SaaS) and dynamic sharing. |

SaaS and ML-driven DSS architecture. |

| [15] |

2022 |

Presents intelligent SS for 5G/B5G using Cognitive Radio (CR), ML/AI, and blockchain; outlines challenges and future research. |

AI-enhanced spectrum management in 5G/B5G. |

| [16] |

2020 |

Offers taxonomy and challenges in ML-driven dynamic spectrum management. |

ML for DSA and interference-aware access. |

| [18] |

2022 |

Surveys deep reinforcement learning for dynamic spectrum and resource management. |

DRL for intelligent resource allocation. |

| [19] |

2017 |

Surveys database-assisted spectrum sharing for satellite systems (GSO/NGSO) and coexistence. |

Satellite-terrestrial spectrum sharing via databases. |

| [20] |

2016 |

Discusses spectrum occupancy and interference maps for PU protection and DSS efficiency. |

Interference-aware DSA planning and PU safeguarding. |

While these contributions in

Table 2 have made substantial progress in enabling efficient and flexible spectrum usage, they primarily focus on terrestrial coexistence scenarios or overlook the fine-grained protection mechanisms required for primary users in satellite bands. Notably, the growing interest in utilizing the 3.8–4.2 GHz band for 5G NR highlights the increasing pressure on incumbent FSS ground stations, which require robust protection against harmful interference. Current approaches often lack detailed characterizations of interference at satellite receive terminals and fail to incorporate predictive, location-aware interference mitigation using spectrum occupancy data.

This review paper addresses this critical gap by focusing on the coexistence of terrestrial wireless mobile broadband systems and FSS/SS ground stations. It aims to explore how spectrum databases and interference maps can be integrated with ML/AI-based decision systems to enhance dynamic resource allocation while ensuring the protection of incumbent satellite users to achieve a higher Dynamic Spectrum Utilisation Efficiency (DSUE). By examining recent advances in PU protection, interference prediction, and adaptive learning for spectrum access, this review establishes a research direction that enables intelligent, real-time management of spectrum access in shared bands involving ground satellite receivers. Ultimately, this contributes to the development of resilient, database-assisted coexistence frameworks suitable for both national regulators and mobile network operators seeking to deploy 5G in shared environments.

DSA is a paradigm that allows for flexible and opportunistic use of the radio spectrum, enabling multiple users grouped as primary and secondary users to share the same frequency bands dynamically. It is another spectrum sharing mechanism/framework, which compared to other techniques, is dynamic, dependent on a definition of an algorithm to manage access with a level of fairness. DSA can significantly increase spectrum efficiency through coexistence techniques, allowing for more effective utilization of available spectrum resources. It refers to the real-time adjustment of spectrum utilization in response to changing conditions, allowing for more efficient use of available frequency bands.

2.1. Spectrum Efficiency and Its Importance

Spectrum efficiency refers to the optimal use of available spectrum resources [

2]. Although this is a generic metric, this might appear high even when some of the bands are not in use. Spectrum Utilisation Efficiency (SUE) measures how efficiently unused or underutilised spectrum is accessed and reused. Maximizing utilisation efficiency is a fundamental goal of spectrum sharing [

2]. DSUE enhances spectrum efficiency by ensuring that available spectrum is not left idle. This is the dynamic, intelligent layer that fills in spectrum usage gaps to achieve maximum efficiency across users, time, space, and frequency.

The measure of the data rate achieved per unit bandwidth by equation

1 is useful in realising the efficiency in statically allocated spectrum, but not insightful if the spectrum is used efficiently in an extended geological view.

where:

Spectrum Utilisation Factor (SUF) refers to how fully the allocated spectrum is utilised over time and geography. It captures spectrum occupancy across space, time, and frequency. This is shown by equation

2

The basic SUE, equation

3, is defined as the ratio of useful data throughput

T to the allocated spectrum bandwidth

B and time

t to realise the SUF in equation

2, expressed as:

In a dynamic spectrum sharing scenario involving terrestrial wireless mobile networks and FSS/SS ground stations, this metric must be spatially and temporally adjusted to account for geographic restrictions around satellite receivers, as well as uplink and downlink separation. We introduce a location-aware efficiency term extending from equation

3, denoted as

, defined as:

where:

is the throughput achieved by user or base station i at spatial location ,

B is the total spectrum bandwidth available for dynamic access (3.6–4.2 GHz),

t is the total transmission time observed,

A is the total area under consideration,

is the area excluded due to satellite protection constraints, such as exclusion zones around FSS ground stations.

Maximizing SUE, equation

3, must not compromise the operational integrity of the PU. The uplink interference from User Equipment (UE) to the satellite receiver is spatially dependent and can be captured through the interference coupling function

, while downlink interference from gNodeB (gNB) to satellite receiver can be expressed as

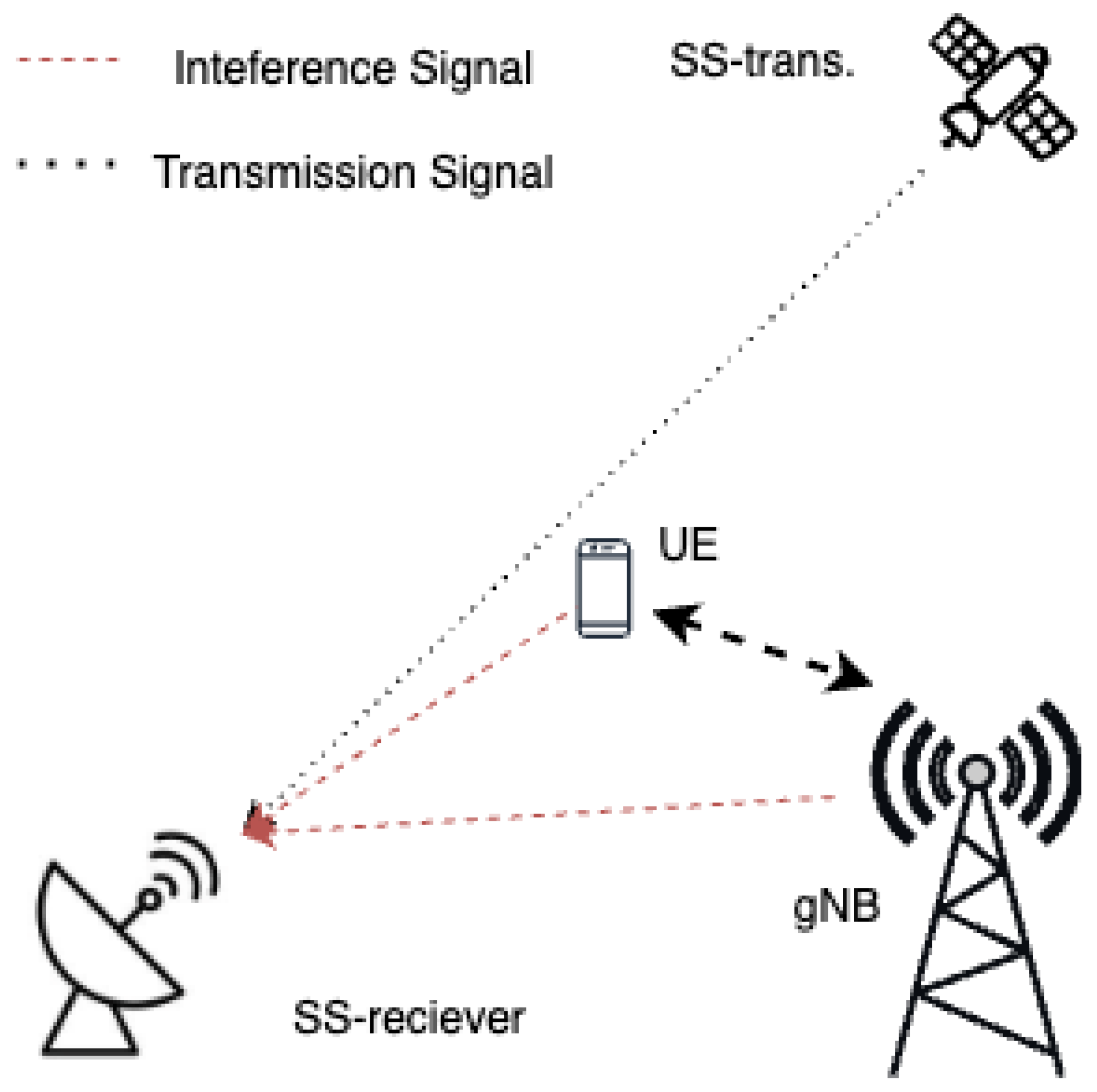

. The resulting interference-aware DSUE can be further refined as:

where

is the interference protection threshold (e.g.,

dB I/N), and the indicator functions

ensure that only locations satisfying interference constraints are included in the efficiency calculation. This formulation captures the essence of coexistence-aware spectrum efficiency, accounting for the impact of spatial exclusion zones, uplink/downlink directional interference, and throughput contributions from dynamically allowed users, thereby enabling an accurate representation of dynamic spectrum utilization efficiency in shared FSS with 5G environments as depicted in

Figure 2 showing the satellite ground station receiving from a space transmitter and also receiving interfering signals from both the gNB and UE.

Satellites transmission power is relatively lower than wireless mobile networks power levels, hence the possible degradation mechanisms to influence equation

5 and ultimately equation

2 be considered are as below:

Aggregate Interference: the cumulative interference from multiple base stations or user devices transmitting concurrently. Even if each SU transmission is compliant individually, their aggregate power may exceed the interference-to-noise (I/N) threshold required by FSS receivers.

Adjacent Cahnnel Interference (ACI): 5G NR signals operating near FSS downlink frequencies can leak energy into adjacent satellite bands due to imperfect filters and non-linearities, especially if no guard band is maintained between the two systems.

Out-of-Band Emission (OOBE): SU transmissions may cause unintended radiation beyond their allocated channel, which can desensitize satellite receivers that have very low noise floors, impacting their ability to detect weak satellite signals.

Co-channel Interference (CCI): In cases where DSS permits co-channel use (e.g., through database-assisted spectrum access), direct overlap in time-frequency-space can lead to significant signal degradation or loss at the satellite ground station.

Beam Misalignment and Antenna Side Lobe Coupling: The use of high-gain, beamforming antennas by 5G and 4G base stations or UE may inadvertently illuminate satellite receivers, especially when side lobes or reflected beams align with FSS antennas, increasing interference risk.

Near-field Interference: If SUs are deployed too close to FSS ground stations, line-of-sight interference paths can bypass natural attenuation and clutter, resulting in elevated interference levels even from low-power devices.

Interference types discussed in [

13], can be applied in an example considering FSS and 5G NR environment to be considered in a calculating the DSUE are listed in

Table 3

Effectively implementing DSA techniques necessitates a comprehensive understanding of both the technological and economic implications of spectrum-sharing methodologies. By enhancing SUE in frequency bands where satellites operate as PUs, DSA presents an innovative solution to address the increasing demand for wireless bandwidth. As highlighted in the analysis of shared spectrum economics, stakeholders must optimize SU bandwidths to fully capitalize on available opportunities for spectrum sharing. Thus, integrating DSA techniques could yield substantial economic benefits while simultaneously accommodating the exponential growth of user traffic in critical frequency bands.

In the realm of satellite communication, DSA techniques play a crucial role in optimizing SUE, particularly in frequency bands where satellites operate as PUs. One of the prominent DSA methods is CR, which allows SUs to detect unoccupied frequency bands and opportunistically access them without causing harmful interference to PUs. This approach enhances SUE and fosters innovation in applications such as disaster recovery and emergency communication, where timely access to bandwidth can save lives, since it provides a level of guarantee to connectivity. Additionally, techniques like spectrum sensing and dynamic frequency selection help identify and adapt to the dynamic nature of satellite service demand, enhancing DSUE to achieve a better SUF. As elaborated in [

4], these advancements have the potential to significantly increase economic benefits for MNOs by optimizing shared bandwidth in saturated frequency bands, thereby underscoring the transformative impact of DSA on satellite communications bands. Notably, the historical evolution of satellite technology, highlighted in [25], has paved the way for these DSA techniques, demonstrating their essential role in enhancing global connectivity through efficient data transmission and supporting crucial sectors such as telecommunications and navigation.

One way to enable DSA is through a Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) architecture where users can access radio resources on demand. This model is particularly relevant for terrestrial wireless communication networks and ground satellites aiming to coexist in C-bands and higher bands.

Navigating the complex landscape of regulatory and technical considerations is paramount for the successful implementation of DSA systems, especially in bands dominated by satellite communications. Effective regulation is necessary to balance the competing interests of satellite as PU and SU looking to exploit the same spectrum. The establishment of clear Exclusion Zone (EZ)s is crucial to mitigate interference, particularly when considering the sensitivity due to variations in PU antenna characteristics, which can significantly influence the assessment of sharing opportunities [26,27]. Furthermore, the technical feasibility of DSA hinges on robust protocols that must ensure seamless coordination between operators. This includes addressing the overhead costs associated with implementing DSA protocols, which can impact the net benefits derived from spectrum sharing. As satellite communication continues to evolve, it is imperative to create regulatory frameworks that facilitate innovation while safeguarding the integrity of existing services [28].

2.2. Spectrum Environment and Interference Conditions

The effectiveness of DSA mechanisms depends heavily on an accurate understanding of the surrounding radio environment and the interference conditions within it. Central to this understanding is the ability to dynamically monitor and adapt to spectrum usage in real time. According to [29], real-time bandwidth monitoring plays a critical role in guiding the optimal transmission strategy for SUs. Spectrum reconstruction techniques, as discussed in the same study, further enhance this by enabling the adaptive adjustment of system parameters in response to environmental variations. These techniques facilitate rapid analysis of channel availability and propagation characteristics.

The spectrum environment consists of both static and dynamic inputs. Static inputs typically include Geographic Information System (GIS) data, such as terrain profiles and clutter classification, which influence signal propagation and coverage. Dynamic inputs, on the other hand, include real-time spectrum sensing/monitoring data that provides current usage and occupancy levels and rapid description of environmental characteristics [29]. By combining these inputs, interference and propagation models can be applied to conduct a comprehensive impact analysis of emissions across the environment.

A foundational principle in DSA systems is the protection of PUs from harmful interference caused by SUs as depicted in equation

5 in the pursuit of higher DSUE, introducing SU networks—such as Base Station (BS) and UEs. As noted in [30], SUs are required to operate in a non-interfering manner and cannot claim protection from interference generated by PUs. This regulatory condition underpins many coexistence and spectrum-sharing protocols. Effective interference mitigation strategies are therefore necessary to ensure that SU transmissions remain below defined thresholds, especially in densely populated or mission-critical spectrum bands. These require the adoption of robust coordination protocols among sharing players due to the sensitivity of the sharing players in terms of interference protection and guaranteed access to the licensed bands [31].

Coexistence refers to the ability of two or more communication technologies to operate within the same spectrum band and environment without hindering each others performance although operating under different rules [

13]. Coexistence can be divided into horizontal spectrum sharing and vertical spectrum sharing cases based on the spectrum access priorities of coexisting Radio Frequency (RF) systems [

10]. Horizontal sharing refers to scenarios where coexisting systems have the same regulatory status (or priority) over the same frequency band. In contrast, vertical sharing refers to the scenarios where coexisting systems have different regulatory status (or priorities) over the same frequency band [

10]. DSA can be classified into the vertical sharing group since the PU, licensed, have a higher priority than the SU.

Coexistence methods involve the definition of boundaries for the occupation of radio resources by the network. On the other hand, interworking is the exchange of information between the technologies to coordinate spectrum usage amongst each other [24]. It is a vital component of spectrum sharing, particularly in unlicensed bands where multiple wireless systems coexist. Coexistence mechanisms regulate spectrum access among different technologies, minimizing interference and promoting fair utilization.

These mechanisms can be categorized into coordinated and uncoordinated approaches. Coordinated coexistence relies on centralized or inter-network coordination, where a central entity, dynamically allocates channels the different technologies to prevent interference [

13,32]. Additionally, inter-network coordination allows networks to exchange information to optimize spectrum access collaboratively. On the other hand, uncoordinated mechanisms operate independently, using techniques which mandates that devices sense the spectrum before transmission to minimize interference [

10,

13,33]. Power control mechanisms further enhance coexistence by adjusting transmission power to minimize interference while maintaining connectivity [

10]. Beyond technical solutions, fairness considerations, regulatory requirements, and standardization efforts from international working bodies to ensure efficient spectrum usage.

2.3. Techniques to Achieve DSA

Spectrum sensing identifies available spectrum by detecting the presence or absence of PUs [34], utilizing methods such as energy detection, cooperative sensing, and database-assisted approaches like the Spectrum Access System (SAS) in CBRS. Spectrum decision involves selecting the optimal frequency band based on channel conditions, interference, and Quality of Service (QoS) requirements, often leveraging machine learning models for intelligent decision-making. Spectrum sharing coordinates multiple users within the same band through underlay, overlay, and interweave approaches, integrating access mechanisms like TDMA, Frequency Division Multiple Access (FDMA), and spatial division. Finally, spectrum mobility ensures seamless transitions when PUs reclaim spectrum, facilitating dynamic reallocation and uninterrupted connectivity. These interdependent techniques form the foundation of DSA, enabling efficient coexistence of licensed and unlicensed users while optimizing spectrum utilization in wireless networks.

2.3.1. Traditional Methodologies in DSA Coexistence Management

Traditional methodologies for developing regulations to manage coexistence often rely on static interference models, fixed separation distances, and predefined protection contours. These approaches, while effective in some scenarios with static environment effects will exhibit shortcomings. Traditional frameworks typically use static interference thresholds and rigid operational parameters that do not adapt to dynamic and evolving spectrum usage patterns. This leads to either over-protection of PUs, wasting valuable spectrum, or insufficient protection, causing harmful interference. These methods rely on conservative assumptions about interference scenarios, such as worst-case power levels, antenna patterns, and geographic separation. This approach does not account for localized variations in deployment scenarios or real-time environmental factors, which can lead to inefficient spectrum utilisation. Traditional systems do not incorporate real-time environmental features such as terrain variations, urban density, or weather conditions that could significantly impact signal propagation and interference. Manual analysis and fixed policies can delay regulatory responses to changing spectrum demands, hindering the deployment of 5G networks while maintaining FSS protections. With the increasing number of devices and users, traditional interference management methods struggle to scale effectively in densely populated regions or globally distributed FSS networks.

2.3.2. Opportunistic Spectrum Access

The general view of enabling licensed spectrum use by SUs when the PUs has no activity within the vicinity bounds. The main challenge is to protect the PU from compromise, either in transmission or security. The SU typically do not have any license to use these vacant channels within the spectrum, and their transmission cannot be guaranteed. The goal of OSA is to take advantage of spectrum opportunities by learning/monitoring the environment and adjusting their transmission parameters adaptively [35]. This relies on accuracy in sensing PU activity, which is proven to bring about expensive overheads, and potential security exposure. Database-assisted enhancements have been studied and implemented in LSA, TVWS and CBRS frameworks to guide SU transmission parameters.

2.4. RIC, Reconfigurable Intelligent Surface (RIS) & MIMO Applications

Improved technologies to enhance efficiency on the physical layer have been discussed and investigated in theory in [36,37], advanced wireless technologies such as RIS, RIC, and MIMO antennas serve as key enablers for interference mitigation and efficient spectrum utilization. RIS, composed of programmable surfaces, can dynamically steer radio signals away from FSS earth stations and synthesize RF nulls, thereby minimizing electromagnetic leakage into protected satellite zones without reducing 5G transmission power. RIC, a component of the Open RAN architecture, leverages ML/AI algorithms to implement real-time radio resource optimization, enabling proactive beam and power control, policy enforcement around exclusion zones, and adaptive interference avoidance strategies. Meanwhile, massive MIMO systems facilitate spatial multiplexing and beamforming, allowing for highly directional transmissions and interference nulling that limit the exposure of FSS receivers to unwanted signals. The integration of these technologies supports intelligent and fine-grained control over the propagation environment, enabling the coexistence of high-capacity 5G deployments with incumbent satellite operations. However, achieving effective protection for FSS also necessitates accurate geolocation data, real-time coordination mechanisms, and standardized coexistence frameworks, particularly in dense or heterogeneous network scenarios.

2.5. Spectrum Management Challenges in DSA Systems

Designing and implementing spectrum management in centralized DSA systems presents significant challenges due to the inherent complexities of monitoring, scalability, and privacy. Spectrum monitoring and infrastructure limitations are pronounced, as traditional monitoring relies on costly and geographically constrained infrastructure like spectrum observatories. Centralized systems require accurate, real-time data on dynamic spectrum usage, which is complicated by the need for efficient data collection from resource-constrained devices in large-scale deployments. Scalability poses another obstacle, as the central controller endures substantial computational and communication loads, impeding system expansion to support extensive user bases and wide areas.

PU privacy is equally critical, as centralized systems often require sensitive PU information, such as location and operational status, to allocate spectrum effectively. Protecting this data against unauthorized access and potential misuse demands robust security measures for the central controller, introducing further computational overheads. Striking a balance between PU privacy and optimal spectrum utilization is challenging, as overly stringent privacy protections may compromise spectrum sharing efficiency, while lax measures could expose sensitive PU data.

Emerging solutions address these issues through innovative approaches. Crowdsourcing leverages the sensing capabilities of mobile devices to reduce monitoring costs and expand geographical coverage [38]. Intelligent task scheduling algorithms optimize resource usage for efficient crowdsourced monitoring, complemented by incentive mechanisms to ensure user participation. Advanced PU privacy measures, such as smart antennas and location uncertainty schemes, enhance privacy without sacrificing spectrum efficiency. Additionally, ML/AI techniques offer transformative potential, enabling accurate channel prediction, RL for decision-making, and Federated Learning (FL) to preserve data privacy in collaborative model training. These advancements, particularly relevant to 5G NR and FSS coexistence, underline the need for adaptive and secure spectrum management strategies in centralized DSA systems.

2.6. Challenges of Implementing DSA

Protecting the PUs from harmful interference is the most important factor in achieving a successful DSA. This is ensuring that the SU does not interfere with the PU. This requires careful spectrum sensing and access management [39] which can be achieved by exchanging activity information in coordinated schemes, but remains a challenge in uncoordinated schemes.

SUs must accurately detect the presence of PUs to avoid interference, but reliable detection can be subject to system complexity and increased costs of enhanced sensing/measurement techniques [41]. Consequently, the trade-offs on sensing/measurement capabilities due to the complexity of the system can lead to threats at the Medium Access Control layer (MAC) layer, such as the hidden node problem, and sub-optimal false alarm and detection probability issues can affect the Physical Layer (PHY) [42]. Additionally, the time it takes to sense and detect an idle channel reduces the effective data transmission time.

Traditional interference coordination and cancellation methods rely on accurate Channel State Information (CSI) estimations, which may be difficult to obtain in DSA networks, mainly because they are of different priority and rely on different regulatory frameworks due to their difference in technology. This ultimately leads to a lack of a centralized control framework due to the impossibility to share CSI and activity information. When a centralized control is achieved, scalability becomes an issue due to heavy computational and communication overheads in a dynamic allocation system environment. Such vast harvesting of CSI and activity information also posses security threats to the PU system which can lead to deduction of PUs locations, status and activity profile.

The economic challenges facing DSA in the C-band and 5 GHz, where cellular, FSS, and other services coexist, include incentivising efficient spectrum use, ensuring cost-effective access, and addressing business concerns of stakeholders. Deployment of spectrum sharing introduces economic and business concerns, such as costs for additional infrastructure and modifications of existing systems by the MNOs. Although these costs might be fractional to established operators, additional Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) is always a risk. To new entrants, these costs become relatively lower and makes it easier to penetrate the market with minimal risk which in-turn poses revenue threats to established operators with traditional spectrum licenses. National Regulatory Authority (NRA)s may wish to monitor and charge a relative administrative fee to incentivize the efficient use of spectrum and punitively if non-efficient usage. Ensuring DSA-capable network equipment is priced similarly to existing equipment, despite potential variations for different administrations needs to be factored-in to realise viability and standardisation. New spectrum releases and pooling may affect the willingness of established MNOs to participate in a joint DSA network deployment, especially if they are more successful in acquiring exclusively licensed spectrum. Availability of spectrum by pooling and other frameworks drive monopoly MNOs to rejecting DSA to protect their monopoly.

Spectrum pooling can be understood as the basis of spectrum sharing in DSA with multi-operators, which can also be the genesis of exacerbated discussions and legal battles between the monopoly operators, or them teaming up to reject DSA in the C-band due to historical battles with the regulators as seen in South Africa in [43,44].

New technologies present complex challenges in protecting PU within DSA. Massive MIMO is an advancement in antenna technology used in 5G networks to significantly improve spectral efficiency, capacity, and coverage. It involves deploying a large number of antenna elements at the base station to simultaneously serve multiple users using spatial multiplexing. Although, currently used in n77, and n79 bands and in mmWave frequencies, this technology employs complex signal processing techniques to achieve Carrier Aggregation and Beamforming to deliver higher throughputs and increase spectral efficiency. These increases the complexity of calculating and deducing the transmission power to be considered in protecting the PU.

2.6.1. Multi-Objective Problem

The maximising of DSUE while considering the above challenges presents a multi-objective optimisation problem because it involves reconciling the conflicting goals across the two communication systems. The terrestrial wireless mobile networks aim to maximise spectral efficiency, coverage, and user throughput through dense deployments and dynamic spectrum use. The FSS/SS, operating with high sensitivity and stringent interference thresholds must be protected from harmful emissions in

Table 3 originating from terrestrial wireless mobile transmissions. These conflicting objectives introduce trade-offs like, increasing transmission power or coverage can enhance mobile performance but risks violating satellite protection criteria, while enforcing larger EZ around satellite ground stations ensures interference avoidance but restricts wireless mobile networks access to valuable spectrum.

Given these challenges, the coexistence problem is best framed as a multi-objective optimization goal. Advanced, data-driven techniques such as ML/AI, DRL, and game-theoretic strategies promise to handle the complexity and adaptivity required in such scenarios. These methods can be employed to learn and predict optimal transmission configurations that yield Pareto-efficient outcomes, ensuring high spectral efficiency for the terrestrial wireless mobile networks while adhering to the strict protection criteria of satellite ground stations. This enables the design of intelligent, real-time spectrum management frameworks that support sustainable coexistence within shared spectrum environments.

3. Overview of Spectrum Management Challenges in Satellite Bands

Coexistence of RF networks are categorised by the need of coordination of the networks involved according to the spectrum usage and opportunities. Coordinated approaches require information collection exchange and analysis among the coexisting networks to increase spectral efficiency. The uncoordinated is when minimal or no information exchange is required to increase spectral efficiency, but the networks tune and adjust their operating parameters for a better coexistence with neighbouring networks. Uncoordinated methods re-adjust their operating parameters by observing the spectrum usage of the other RF system. They are all resource allocation scheme extended with consideration of the environment. Table 2 in [

10] presents pros and cons of the most common spectrum sharing methods. They can be further classified into four domains: time, frequency, code, space domains, depending on the domain they allocate resources in. The spectrum to which the network is deployed-in drives the type of sharing to be employed. In the C-band, infrastructure-based & sharing rule-based methods promise to be easy to implement with minimal changes to existing standards on primary users. Compared to other methods, these two methods have overheads in considering the environmental changes and primary user activity.

Satellite receivers have been operating in the C-band from 3.4 to 4.2 GHz for downlink connectivity. The use of the C-band for 5G services poses potential interference risks to FSS Very Small Aperture Terminals (VSAT) systems that operate within close proximity, typically within 1-2 kilometres [45–47].

The existence of 5G signals and satellite signals in this band will lead to mainly co-channel interference, inter-modulation interference, and adjacent channel interference. OOBE can arise due to FSS operating just below 3800 MHz. The high power levels in 5G devices can saturate sensitive receivers in FSS VSAT systems, even if they only operate in adjacent bands. These 5G signals in nearby frequencies and locations can block or desensitise satellite receivers, making them less effective at detecting weak satellite signals.

The FSS Earth Station (ES) Low-Noise Block (LNB) amplifier operates linearly only up to a certain power level of the incident signals. In the traditional operating range of the LNB of 3400-4200 MHz, the incident signals could be from the 5G BS, the satellite downlink, or both. As the incident power increases, the amplifier transitions from linear to non-linear behaviour and eventually saturates, resulting in the complete loss of the incoming signals. Satellite signals received by the LNB have much lower power than the higher-powered 5G terrestrial signals, potentially causing overloading/saturation of satellite antenna LNBs and disrupting FSS C-band receivers [45].

4. Evaluation of Recent DSA Applications

4.1. Case Studies and Application

4.1.1. TVWS

TVWS is the vacant spectrum in the television broadcast bands (Very High Frequency (VHF) and Ultra High Frequency (UHF)) that is not being used by licensed television stations [48–51]. This spectrum became available due to the transition from analogue to digital television broadcasting. Regulators have embraced licence exemption or light licensing policies to improve spectrum accessibility for wireless innovations in the TVWS bands [52]. It offers a cost-effective means of connecting sparsely-populated areas, areas with dense vegetation, and rugged terrain due to its favourable propagation characteristics [34]. SUs access TVWS spectrum on the condition that they cause no harmful interference to Digital Terrestrial Television (DTT) services and that they vacate the channel when a PU occupies it. The regulatory framework goal is to protect licensed Televisions (TV) stations from harmful interference that may originate from SU networks.

Advanced wireless radio equipment, like White Space Device (WSD) can interact autonomously with geo-location databases to submit device parameters and obtain operating parameters. The Protocol to Access White Spaces (PAWS) is used to achieve interoperability between WSDs and geo-location databases.

4.1.2. LTE-Unlimited (LTE-U) and Wi-Fi Coexistence

The 2.4 GHz is widely utilized by Wi-Fi and other unlicensed technologies, the 2.4 GHz band is also considered for LTE-U and LAA. Its global availability and mid-band characteristics make it suitable for DSS, but interference management remains a critical challenge. Authors in [53–55] explored Listen Before Talk (LBT) mechanisms such as Carrier Sense Multiple Access (CSMA)/Collision Avoidance (CA) for spectrum sharing without coordination among networks. Busy tone signaling in [56] can also be used to announce occupancy of a frequency.

4.1.3. Citizens Broadband Radio Service

CBRS is a specific implementation of DSA in the United States of America (USA), operating in the 3.5 GHz band (3550-3700 MHz). The main objective in the CBRS system is to reuse the 3.5 GHz spectrum allocated to military and federal radio and radar services while protecting the PUs from interference. These are the original incumbents of the spectrum before CBRS was introduced. It employs a three-tiered access model designed to optimise spectrum utilisation and promote more efficient sharing among various types of users [57,58]. The tiers include PU, Priority Access License (PAL), and General Authorised Access (GAA). PUs, such as the USA Navy and FSS, retain top priority and guaranteed protection from interference, and can require all secondary systems in a spatial region to relinquish spectrum when needed. The PAL tier offers licensed access to commercial users for critical services with a moderate level of interference protection from the GAA tier. They hold short-term licenses over a small geographic area. Lastly, the GAA tier allows unlicensed users to operate in the band opportunistically, provided they do not interfere with higher-tier users. This dynamic framework leverages advanced spectrum sensing technologies and a centralised SAS to manage and coordinate access.

The SAS dynamically monitors for PU activity and ensures they are protected from interference by instructing PAL and GAA devices (CBRS Device (CBSD)s and CBRS Devices) to vacate the necessary channels [59]. A network of sensors, Environmental Sensing Capability (ESC) that detect the PU signals to determine activity and to deduce which CBSD transmission is to be suspended to guarantee PU protection. The SAS is also responsible for assigning mutually exclusive channels to PAL and GAA users when PUs are not using the spectrum. The main idea of CBRS as a DSA mechanism is to allow SU (PAL and GAA) to opportunistically utilize spectrum that is not actively being used by the higher-priority PUs. When PUs are inactive in a specific area and frequency, this spectrum can be made available for commercial and other uses, thus improving overall spectrum efficiency.

While both LSA and SAS are licensed spectrum sharing models, SAS, as implemented in the US for the 3.5 GHz CBRS band, includes a third tier GAA, which has lower access guarantees than the PAL tier (similar to LSA licensees) [61]. SAS also relies on a SAS entity for authorization and management of spectrum use. Furthermore, SAS is designed to ensure coexistence with incumbents who may not provide a priori information, potentially utilizing sensing mechanisms like the ESC.

4.2. C & S Bands and Other Bands

The ITU-R Sector and 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) both play significant roles in the evolution and standardization of DSA, from TVWS to 5G NR, while also considering coexistence with FSS. The ITU-R establishes the global regulatory framework for spectrum allocation by distinguishing between primary and secondary services, where secondary users must tolerate interference from primaries.

The ITU-R has:

Identified International Mobile Telecommunications (IMT) bands, such as for Third Generation of Radio Networks (3G) and 5G, necessitating compatibility studies with FSS in bands like 3400–4200 MHz.

Conducted technical studies (e.g., ITU-R Recommendations M.2101 and P.452) to define interference thresholds, separation distances, and conditions necessary for coexistence between IMT and FSS.

Defined protection criteria using methods such as Interference-to-Noise (I/N) ratios to assess and limit potential harm to satellite receivers.

Provided standardized antenna patterns (e.g., ITU-R S.465) critical for accurately modelling interference from terrestrial systems onto FSS earth stations.

Through the World Radio Conference (WRC) process, ITU-R updates global rules, identifies new bands, and adjusts regulations to balance growth in mobile services and protection for incumbents.

The 3GPP complements ITU-R by developing technical specifications and architectures for mobile systems like Long Term Evolution (LTE) and 5G NR, incorporating DSA mechanisms into system designs. Specifically, 3GPP:

Defines dynamic spectrum sharing methods, including LSA, enabling MNOs to use incumbent spectrum under managed conditions, supporting evacuations on demand.

Introduced New Radio-Unlicensed (NR-U) and LTE-U mechanisms that employ LBT and adaptive duty cycling to coexist in unlicensed bands with technologies like Wi-Fi.

Specifies channel models, deployment scenarios (Urban Macrocell - UMa, Urban Microcell - UMi, Rural Macrocell - RMa), and antenna patterns used in coexistence analysis with FSS [62].

Integrates DSS technologies to allow seamless 4G-5G coexistence within the same band, optimizing resource usage [63].

Aligns with SAS frameworks, particularly in bands like CBRS (3.5 GHz), enabling multi-tiered dynamic spectrum access and protecting PUs based on ITU-R and localized regulations.

The ITU-R establishes the global regulatory and technical environment necessary for spectrum sharing, including protecting incumbent services through studies, thresholds, and coordination procedures. The 3GPP develops the technology standards and protocols that implement these regulatory principles within mobile networks, ensuring that 5G NR systems dynamically adapt to protect PUs. Together, they bridge policy and technology, ensuring that dynamic and opportunistic access to spectrum is both technically feasible and legally compliant.

4.3. Geo-Location Usage in Network Management

Geo-location databases as presented in [

14,

19] play a fundamental role in enabling DSA by facilitating spectrum sharing while protecting PUs. These databases are used to determine localized spectrum availability by acquiring and managing information about service providers and incumbents, as seen in models like TVWS and LSA. By maintaining detailed records of PU locations, types, and operating schedules, geo-location databases ensure that SUs avoid causing harmful interference, often by enforcing exclusion zones. Systems such as the SAS for CBRS rely on registered device locations to dynamically allocate spectrum resources while coordinating between PUs and SU. The operational aspects involve building and maintaining secure, collaborative databases capable of sharing real-time information across multiple services. Furthermore, advancements such as integrating spectrum sensing and developing Radio Environment Maps (REMs) are being explored to enhance the precision and responsiveness of geo-location databases, making them even more critical in future dynamic spectrum sharing ecosystems. Thus, geo-location databases serve as a cornerstone in managing spectrum access, ensuring efficient usage and robust protection of primary services across modern DSA frameworks.

Despite of the limited opportunities, actions have been taken towards exploring new unencumbered frequency bands for the use of wireless activities. Meanwhile, the idea of spectrum sharing has started to attract a great deal of interest from both academia and industry. Hence, DSA is then proposed to enable the spectrum sharing between PUs and SUs to mitigate the above mentioned spectrum scarcity problem.

There are two significant spectrum initiatives in South Africa for enabling DSA [26]: (1) TV bands: Low power unlicensed users are permitted by ICASA to access the unused channels in the TVWS. A database-driven approach is mandated by ICASA in these bands. To obtain the spectrum access permission, the unlicensed devices must register with a database that informs the spectrum availability. (2) 3.5 GHz Band: Similar to the CBRS in the USA promulgated by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for dynamic spectrum sharing between government and commercial users in the 3.5-3.7 GHz (referred to as 3.5 GHz band) [28,64]. This sharing paradigm allows CBSD, which are also called SUs, to opportunistically use the 3.5 GHz band licensed to Satellite and Radar systems, in locations and times where the PUs are not using this band.

5. Review on Implementations and Trials

Countries have adopted different technical, regulatory, and operational approaches to ensure that 5G NR can expand without causing harmful interference to incumbent FSS/SS systems.

The international DSA trials summarized in

Table 4 demonstrate a range of regulatory and technical strategies adopted to enable the coexistence of terrestrial 5G networks and incumbent FSS operations in the C-band (3.4–4.2 GHz). Countries such as the United States and Canada led structured, phased rollouts with formal spectrum clearance, relocation of FSS services, and strict out-of-band OOBE controls. Malaysia, South Korea, and Japan implemented coexistence guidelines that included guard bands, exclusion zones, beamforming constraints, and geographic coordination databases to protect satellite ground stations.

In contrast, India adopted a more conservative approach by deferring aggressive 5G rollout near FSS infrastructure and emphasizing mandatory coordination. Despite different regulatory environments, all countries shared a common goal of minimizing interference to satellite downlinks through physical separation, power control, and coordination protocols.

Importantly, the trials did not report significant integration of ML/AI techniques in real-world deployments, highlighting a research opportunity. Future work could build upon these frameworks by introducing ML-driven spectrum management and interference mitigation strategies that dynamically adapt to real-time satellite and mobile network conditions.

6. Evaluation ML/AI Applications in Spectrum Management & Coexistence

Coexistence studies in dynamic spectrum sharing environments utilize a variety of mathematical methods to manage interference and allocate spectrum efficiently. In typical terrestrial scenarios—such as coexistence between Wi-Fi, LTE, or 5G networks—models like stochastic geometry, game theory, and optimization are employed to characterize and optimize network behaviour under interference constraints. However, when FSS or other satellite ground receivers are introduced into the spectrum environment, these modelling approaches require significant adaptation due to the stringent protection requirements, highly sensitive receiver front-ends, and directional antenna characteristics inherent to satellite systems.

ML/AI pose a positive advancement in addressing the limitations by dynamically learning and adapting to the diverse and complex coexistence scenarios. ML/AI algorithms can extract meaningful features from large datasets, such as spectrum usage, signal power, geographic and topographic characteristics, and temporal patterns. This allows for more granular and scenario-specific interference management. The systems can model and predict interference levels in real-time, accounting for changing environmental factors and device deployments. This enables adaptive protection measures for FSS while maximizing 5G NR spectrum efficiency. Complementing the systems with satellite monitoring systems data, environmental historical data, context-aware regulatory insights can be extracted to develop tailored policies for specific characteristics of each deployment scenario. Techniques like RL can optimize coexistence strategies by continuously learning from operational feedback, balancing interference protection and spectrum utilization dynamically. By addressing these limitations of traditional methodologies, ML/AI provides a pathway to develop more robust, adaptive, and efficient coexistence frameworks, ensuring harmonious 5G NR and FSS operation in shared spectrum environments like the 3.6-4.2 GHz band.

Table 4.

Comparison of International DSA Trials Involving FSS Coexistence

Table 4.

Comparison of International DSA Trials Involving FSS Coexistence

| Country |

Band (GHz) |

PU / SU |

Regulation Developed |

PU Protection Measures |

DSA Trial Outcomes |

ML Used |

| Malaysia |

3.5–4.2 |

FSS / 5G |

Yes (MCMC Guidelines) |

|

Successful pre-deployment trials validated coexistence assumptions |

No |

| South Korea |

3.5–3.8 |

FSS / 5G |

Yes |

|

Successful, with ongoing adjustments for urban deployment |

No |

| Japan |

3.4–3.8 (5G); 3.8+ (FSS) |

FSS / 5G |

Yes (MIC Guidelines) |

|

Effective with localized constraints; hybrid use approved |

Partial |

| India |

3.4–3.6 (5G); 3.7–4.2 (FSS) |

FSS / 5G |

Yes (TRAI Strategy) |

|

Conservative deployment; full DSA not yet realized |

No |

| Canada |

3.45–3.65 (5G); 3.8+ (FSS) |

FSS / 5G |

Yes (ISED Phased Plan) |

|

Successful urban trials (e.g., Toronto); ongoing migration |

No |

| United States |

3.7–3.98 (5G); 4.0+ (FSS) |

FSS / 5G |

Yes (FCC Auction 107) |

FSS relocation to upper C-band OOBE limits, filters, siting restrictions Ground station tech upgrades |

Highly structured, commercial deployments active |

No |

6.1. Machine Learning for Enhanced Coexistence

ML/AI can play a significant role in optimizing dynamic spectrum sharing between 5G NR and FSS, since this is a mainly a regional specific problem, with unique challenges all round. This necessitates careful planning, coordination, and dynamic adaption to the environmental changes per region.

ML/AI plays a pivotal role in enhancing the coexistence, employing SAS frameworks by effectively managing interference and considering distances from PUs. By leveraging ML/AI algorithms, SAS frameworks can dynamically adapt their resource allocation strategies based on real-time environmental conditions, thereby improving spectrum efficiency and minimising interference. One approach involves utilising supervised learning techniques to predict interference levels based on historical data and environmental parameters such as distance from PUs, signal strength, and traffic patterns. By training models on past interference scenarios and their corresponding outcomes, SAS frameworks can make informed decisions on channel assignment and power control to mitigate interference while maximising spectrum utilisation. Regression models like polynomial regression or Support Vector Regression can predict channel conditions for users across different technologies and bands [

2].

Channel Condition Prediction: Regression models like polynomial regression or Support Vector Regression (SVR) can predict channel conditions for users across different technologies and bands. This information enables 5G NR networks to select high-quality channels in various frequency bands, facilitating a flexible, on-demand Spectrum-as-a-Service architecture. RL: RL agents can learn to make optimal decisions regarding spectrum sharing, maximizing rewards for efficient spectrum utilization. These agents can use predicted channel conditions as input to allocate suitable channels for user requests.

The main object in coexistence is to allow new technologies access to the spectrum while guaranteeing protection of the PU. Authors in [22,23,47] emphasize interference management as a critical aspect of the system. Both 5G NR and FSS are to operate in the licensed bands and must avoid causing harmful interference to each other. Technical and regulatory bodies like the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), Wireless Innovation Forum (WINF) and 3GPP play a critical role in standardizations, developing frameworks that define technical specifications, interference thresholds, and operational procedures to ensure harmonious coexistence between different technologies [22,47]. These technical specifications addresses the directionality of the antennas, power levels and operating bands for the different coexistence scenarios. FSS earth stations typically utilize highly directional antennas pointed towards the satellite, while BS’s might use more omnidirectional antennas. This difference in antenna characteristics can be exploited to manage interference by carefully planning BS locations and antenna beam directions [22]. BSs can transmit at higher power levels compared to some unlicensed devices. This necessitates careful power control mechanisms and potentially larger separation distances to protect FSS receivers from interference.

Works like [27] employ neural networks, including Radial Basis Function Neural Networks (RBFNN) and General Regression Neural Networks (GRNN), to mitigate interference between 5G and FSS systems operating in adjacent frequency bands. However, challenges persist, such as adapting these methods to advanced 5G technologies like beamforming and MIMO, which fundamentally reshape the interference landscape. Similarly, studies such as [65] explore the potential of Q-learning and auction-based approaches for dynamic channel allocation in the CBRS band but highlight the computational complexity associated with real-time operations under high load conditions. Furthermore, hierarchical reinforcement learning, as discussed in [66], demonstrates its utility in balancing quality of service QoS for diverse traffic types, including ultra-reliable low-latency communications URLLC and enhanced mobile broadband eMBB. However, scalability and throughput degradation for eMBB traffic under heavy loads remain significant hurdles. Collectively, these studies underscore the transformative potential of ML/AI in fostering coexistence but also emphasize the need for scalable, adaptable, and efficient algorithms to meet the evolving demands of 5G and beyond.

7. Regulatory Considerations

ICASA, is the national custodian of the frequency spectrum and regulator of wireless communication technologies in South Africa. As the custodian, ICASA sells over licenses to MNO’s to facilitate their communications. In licensed bands, the MNO’s implement access policies to allocate access to their customers through their distributed infrastructure of radios all over the country. With the adoptions of 4G, LTE, 5G, B5G, the regulator has been stretched by big MNO’s requesting more spectrum to grow and maintain their business and the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) industry as a whole in the forefront comparing to the rest of the world.

With the short-comings of the two transitions mentioned in [67,68], emphasis and explorations have been added to opportunistic access technologies, with Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) leading the path with TVWS technology [72]. With successful roll-out of the technology recently, ICASA has increased the scope to follow the international trends of adopting coexistence and opportunistic access in unlicensed bands with 5G technologies [73]. The undertaking with the TVWS roll-out has proven potential success in creating an opportunistic access environment in a band can help expand and augment wireless communications, while increasing spectral efficiency. In the 2023, ICASA presented a proposal for a regime to formulate opportunistic spectrum management in the S and C frequency bands [74]. The proposal aims to establish mechanisms to coexist the resident new and old technologies in the two bands with fairness.

Navigating the complexities of spectrum management in satellite bands presents a myriad of challenges, particularly as demand for terrestrial and satellite communications continues to escalate. Satellite services operate predominantly within designated frequency bands, where they must contend with both regulatory limitations and the operational requirements of ground-based systems. The coexistence of multiple users, particularly in the 3.8-4.2 GHz range, exacerbates the challenge of interference, necessitating sophisticated management strategies. Notably, the integration of DSA technologies could dramatically enhance spectrum efficiency, allowing for greater flexibility in the allocation and utilization of frequencies as highlighted in the call for increased C-Band carrier aggregation bandwidth from 300 MHz to 800 MHz. As satellite communications evolve, particularly in response to burgeoning data demands, the shift towards shared spectrum frameworks is paramount, offering potential economic benefits to mobile network operators by optimizing spectrum use. Hence, addressing these spectrum management challenges is vital for the sustainable growth of satellite communications and the efficacy of emerging DSA technologies.

7.1. Current Regulations Impacting DSA Implementation in Satellite Bands

The implementation of DSA in satellite bands, particularly within the 3.8-4.2 GHz range, is significantly influenced by current regulatory frameworks that prioritize the protection of primary users, especially satellite operators. Regulations mandate strict exclusion zones to mitigate interference risks that could arise from secondary users in these bands [75]. Consequently, MNO’s face challenges in optimizing spectrum utilization due to these restrictions, which can stifle investment in shared networks and limit potential economic benefits. Moreover, the complexity of inter-operator coordination in deploying DSA poses further obstacles, requiring regulatory bodies to evaluate the efficacy of existing protocols [

8]. In balancing innovation with incumbent rights, regulators must develop transparent guidelines that facilitate DSA while ensuring satellite communications remain robust. Such a regulatory landscape is essential for fostering the necessary investment and technological advancements in these critical spectrum bands.

Similarly, the considerations in 5G NR and FSS coexistence is similar to the TVWS considerations, wherein the primary incumbent is the TV broadcasting network, and is to be protected at all time. Although, in this instance, both technologies will be licensed, the primary incumbent is to be guarantee protection at all times. The FCC, for the CBRS, employed a SAS to manage the spectrum sharing, ensuring incumbent protection, and coordinating access of the secondary users by interacting with the incumbent databases [76]. This SAS monitors interference levels between the different devices/transmissions and allocates power transmission levels for each, guided by the standards in [77]. Standardization also considers fairness in the sharing between secondary users and interoperability between different technologies.

7.2. Leveraging TVWS Regulatory Models for 5G NR vs. FSS Coexistence in the 3.6–4.2 GHz Spectrum

The development of regulatory frameworks for TVWS devices by bodies such as the FCC in the United States and European Telecommunications Standard Institute (ETSI)/Ofcom in Europe provides valuable lessons for facilitating 5G NR and FSS coexistence in the 3.8-4.2 GHz band through dynamic spectrum sharing. The FCC’s approach, which categorizes devices into fixed, Mode II, and Mode I (sensing-only) types, allows for flexibility in device deployment based on operational requirements. However, the reliance on geolocation databases for interference protection, along with detailed separation distances and protection contours, ensures robust incumbent protection [78]. In contrast, the ETSI/Ofcom framework in Europe adopts a more unified approach to WSD regulation, emphasizing geolocation databases and conservative power limits based on worst-case density estimates to safeguard incumbents. These frameworks illustrate the importance of balancing innovation and spectrum efficiency with rigorous protections for incumbent users, a principle that can guide international coexistence strategies for 5G NR and FSS [79].

In South Africa, ICASA have also developed regulations that could inform coexistence management in this spectrum. ICASA has implemented TVWS guidelines focusing on geo-location databases to protect broadcasters while maximizing secondary access opportunities. Similarly, CSIR has been instrumental in conducting trials and establishing technical standards for WSDs in the region. For the 3.8-4.2 GHz band, such approaches can be adapted to incorporate advanced geolocation systems tailored for FSS protection while allowing flexible 5G NR deployments. By leveraging lessons from TVWS regulation, including the potential use of spectrum sensing as a supplementary tool and fostering international collaboration on database harmonization for cross-border spectrum management, regulators can create robust frameworks for dynamic spectrum sharing. This will support equitable spectrum utilization while safeguarding critical satellite services.

All three regulators approach emphasizes predefined separation distances, and protection contours with transmission power management to ensure incumbent protection [79]. Although CBRS and LSA incorporate sensing to complement the geolocation database, sensing can easily complicate the management algorithms by catering for sensor malfunctions and other technical issues.

8. Challenges and Future Directions

As DSA frameworks evolve to support increasingly dense and heterogeneous networks, new challenges emerge—particularly due to the integration of advanced antenna technologies such as Massive MIMO, RIS, and RIC. While these innovations improve spectral efficiency and beamforming capabilities, they also increase the complexity of interference management and coexistence protection, especially in shared bands involving incumbent services like FSS. Massive MIMO and RIS enable highly directional transmissions, but their real-time dynamic behavior can create unpredictable interference footprints, challenging conventional protection zones. Guaranteeing protection for incumbent users now requires environment-aware, adaptive models that can dynamically account for changing radiation patterns and propagation conditions. Furthermore, RIS-aided beam steering adds a layer of reconfigurability that cannot be easily modelled using traditional static interference assumptions.

With a few possible advancements in facilitating DSA involving PUs and SUs, mainly achieving absolute protection for the PU with the introduction of MIMO, RIC, and beamforming necessitates intricate computation to decision making. One future direction involves the need for a database-enabled model to address the challenges of protecting primary users from interference caused by unlicensed spectrum users and ensuring equal spectrum access opportunities for new users [

8]. This emphasises a need for a central store for PU sites and operational parameters or limits to enhance a SAS logic to manage SU operational parameter, limits and consideration of protection zones. This further poses a need for influence on MIMO and RIC operational parameters and beamforming algorithms to achieve dynamic protection of the PU; fair spectrum allocation within SUs and protection between SUs.

Research is needed to analyse decisions on spectrum, especially with migration to higher frequency bands, considering the specific location-based deployment of technologies like B5G. This ties into the idea of localized licenses, where the value and pricing might vary geographically and temporally according to socio-economic factors, creating opportunities for DSA based on these factors. Several research efforts focus on DSA that adapts to network conditions and user needs [80]. Applying these dynamic approaches to incorporate temporal and localized licensing, while respecting protection zones, is a promising avenue. ML/AI techniques are being explored to facilitate automation and dynamic spectrum sharing [

8,22,81–83].

DSA with temporal localized licenses and protection zones needs to focus on developing sophisticated management systems, possibly leveraging ML/AI, to ensure efficient spectrum utilization while safeguarding PUs. It also requires defining clear operational rules and evaluating the practical implementation and performance of such dynamic licensing and protection mechanisms in various wireless network scenarios, including terrestrial and satellite systems [

8].

Effective interference management is crucial as more technologies coexist within the same spectrum bands. Advanced techniques like ML/AI-based interference prediction, adaptive beamforming, and dynamic power control are being explored to address this challenge. Ensuring fair and efficient coexistence among diverse technologies remains a significant challenge. Coexistence mechanisms such as LBT, adaptive duty cycling, and dynamic spectrum allocation are being refined to improve DSS performance. Spectrum opportunities are often fragmented, complicating aggregation and utilization. Techniques like carrier aggregation and spectrum stitching are being developed to address this issue, albeit at the cost of increased system complexity.

The success of DSS depends on harmonized regulatory frameworks and viable business models. Collaborative efforts between stakeholders, including regulators, operators, and industry players, are essential to ensure efficient spectrum sharing.

ML/AI are poised to revolutionize DSS by enabling intelligent and adaptive spectrum management. Techniques like reinforcement learning, deep learning, and federated learning can automate decision-making, optimize resource allocation, and enhance interference mitigation in real-time. To address these challenges, ML/AI present promising avenues. ML/AI techniques can be employed to predict interference, learn optimal beam configurations, and dynamically allocate resources in real time. Particularly, reinforcement learning and federated learning approaches are being explored to support adaptive spectrum management with limited centralized control. These models enable multi-MNO coordination under LSA or similar models by supporting short-term, geo-local licensing schemes.

Future research should focus on integrating spatial awareness, antenna state information, and spectrum demand forecasting into learning-based DSA algorithms. There is also a growing need for standardized metrics and datasets to evaluate ML/AI-driven spectrum sharing under realistic deployments. In addition, regulatory evolution must keep pace, potentially requiring real-time spectrum monitoring via geo-location databases and RIC-level orchestration to enforce interference protection guarantees.

Ultimately, the convergence of advanced antenna systems and intelligent spectrum management holds the potential to realize highly efficient, interference-resilient spectrum coexistence across 5G and beyond. Key research directions include:

Development of hybrid ML/AI-assisted databases for coordinated DSA.

Integration of RIS/MIMO-aware propagation models for real-time interference estimation

Standardization of ML/AI-driven coexistence metric.

Regulatory updates that support flexible, data-driven spectrum sharing.

9. Conclusions

In reviewing the spectrum management challenges in DSA systems from the perspective of spectrum sharing mechanisms, it is evident that traditional approaches face significant limitations in effectively balancing spectrum utilization, scalability, and incumbent protection. Static spectrum-sharing mechanisms, reliant on fixed rules or predefined parameters, struggle to adapt to dynamic and complex scenarios, leading to inefficiencies in spectrum allocation and coexistence management. This review highlights several key findings for enabling efficient and interference-aware DSA:

Coexistence Feasibility: Coexistence is feasible when technical safeguards—such as exclusion zones, antenna beam steering, power control, and spectrum coordination—are enforced. Ensuring that interference from gNBs and UEs does not exceed established interference-to-noise (I/N) thresholds at the FSS/SS ground station is critical. These thresholds are defined by the sensitivity and operating parameters of the satellite receivers.

Spectrum Utilization Efficiency: Traditional spectrum efficiency metrics can be extended to DSUE by incorporating the probability and severity of interference events. This includes factoring in both spatial (proximity, antenna alignment) and temporal dimensions (time-varying traffic demand) of spectrum use. A reduction in spectral reuse due to interference mitigation measures must be captured in DSUE calculations, allowing for a more realistic assessment of spectrum productivity in shared environments.

Dynamic Environments and Interference Modeling: In highly dynamic settings, such as urban deployments with moving UEs, interference patterns vary over time. Hence, real-time interference estimation—using models that consider antenna patterns, blockage, terrain profiles, and directional gain is necessary. These models help determine how much usable spectrum remains available without degrading the performance of protected SS.

-

ML/AI Integration: ML/AI techniques such as DRL and Q-learning can enhance DSUE as a multi-objective problem by enabling intelligent spectrum management. ML/AI can:

Predict interference conditions and adjust transmission parameters proactively,

Classify zones of permissible transmission based on the satellite receiver’s location,

Optimize beamforming and power control decisions in real time,

Assist in dynamic channel allocation that balances utilization and protection constraints.

The adoption of DRL within simulated environments present a transformative approach to address these limitations. DRL enables DSA systems to learn optimal spectrum-sharing policies by interacting with dynamic and realistic simulations of spectrum environments, incorporating features such as varying interference levels, user demands, and environmental conditions. By simulating diverse scenarios, DRL can optimize spectrum usage in real-time while safeguarding incumbent operations, enhancing both the effectiveness and adaptability of policy development. This methodology offers a promising pathway to create robust, data-driven spectrum-sharing frameworks, ensuring efficient utilization of shared resources in increasingly congested and competitive spectrum environments.