1. Introduction

The construction industry is undergoing a paradigm shift, driven by the emergence of digital technologies that enable the management of complexity, uncertainty, and sustainability [1-2]. As projects grow more intricate with diverse stakeholders, sustainability imperatives, and unpredictable site conditions, digital transformation has become essential. Among these advancements, Digital Twin (DT) technology stands out as a pivotal tool, enabling the real-time synchronization of physical assets with virtual models to support simulation-driven and predictive decision-making [

3,

4].

The integration of DT with Building Information Modeling (BIM) has garnered increasing attention. BIM provides a foundational platform for data-driven project coordination, design management, and stakeholder collaboration [5-9]. While BIM offers a comprehensive static representation of a facility, DT augments this by incorporating real-time data streams to enable dynamic responses, such as anomaly detection, maintenance forecasting, and risk evaluation, within a closed-loop feedback system [10-11].

Despite these technological advances, significant research gaps remain, particularly in applying BIM-DT integration to optimize the production and storage of precast concrete (PC) components. Prior research has often focused on modular production systems or factory-based simulation models, which tend to lack the flexibility required for resource-constrained, site-specific scenarios [12-13].

Moreover, existing studies have largely overlooked real-time planning for in-situ production and yard layout of PC components [14-16]. Efficient management of these components demands precise coordination of production, transportation, and temporary storage, all of which are susceptible to spatial limitations, scheduling conflicts, and environmental considerations [

17]. A comprehensive and real-time platform is urgently needed to monitor, predict, and optimize these tasks.

In particular, studies on in-situ PC production have primarily focused on production area and layout planning [18-22]. However, yard-stock areas are reported to require more than five times the space of production areas [23-26], and inefficient stockyard layouts can lead to material congestion, schedule delays, and increased environmental burden [27-29]. Nonetheless, research on operational strategies and layout management for storage areas remains limited [30-31].

In-situ production replicates the processes of factory manufacturing, rebar placement, formwork, concrete pouring, curing, and temporary storage, on the construction site [32-35]. This method has been shown to reduce environmental loads by over 14.58% and construction costs by up to 39.4% compared to factory production, without sacrificing quality [20,21,36-37]. These benefits highlight the need for intelligent, real-time scheduling and layout planning using BIM-integrated DT systems and simulation tools.

Studies also show that in-situ production can yield quality levels equal to or exceeding those of in-plant production, making it competitive in terms of convenience, quality, cost, and schedule [

21,

36]. To gain these advantages, it is essential to optimize real-time production and layout planning based on site conditions, requiring the integration of BIM-based DT technology and probabilistic simulation tools. Accordingly, this study proposes a BIM-based DT framework designed to optimize the in-situ production and yard-stock layout of PC components. The objectives are to minimize construction carbon emissions through predictive modeling and simulation.

This paper emphasizes the importance of an integrated platform that simultaneously addresses layout efficiency and carbon reduction strategies as a key enabler for sustainable construction. The scope of this study is confined to steel-reinforced concrete (SRC) precast components.

2. Literature Review

2.1. In-situ Production and Yard-stock PC Components

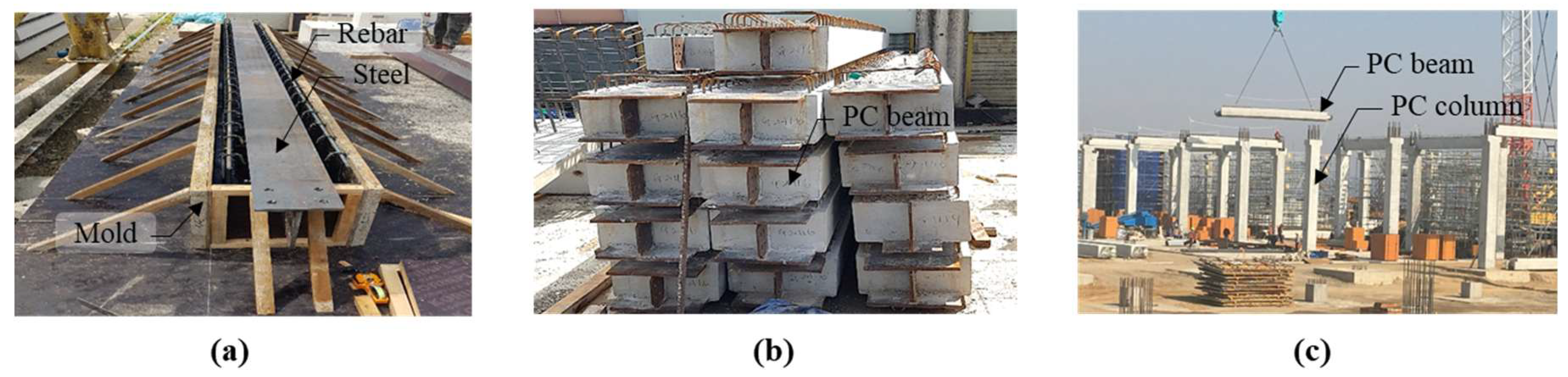

The yard layout process follows the sequence of production, storage, and installation [20-21,38]. As illustrated in

Figure 1 (a), components are first produced based on zone-specific requirements identified from design drawings. Since component shapes and sizes vary, multiple mold types are required. Zones are classified by component type (e.g., beams, columns, slabs), and production is planned to meet the earliest possible installation deadline within each zone. As production, storage, and installation quantities are the same, the components to be installed are identified. The quantity is calculated to determine the target quantity for in-situ production. The location of the column and beam components for each zone of in-situ production quantity is analyzed through design drawing analysis.

The number of members and area for yard-stock of

Figure 1(b) are calculated. And the required yard-stock area is calculated by multiplying the number of members. The production and yard storage available area for each process are calculated, and the yard storage and production arrangement plan are simulated based on the reviewed area. If yard storage and production are not satisfied, the arrangement simulation is completed through repeated modifications (feedback routine). For yard storage simulation, first, the crane movement path is analyzed and the possibility of utilizing the yard space is reviewed. At this time, the yard space is determined by dividing it into before and during the installation of PC members. The yard-stock utilization order is determined, the possibility of utilizing the yard-stock space according to the in-situ production schedule is reviewed.

For PC component installation, as shown in

Figure 1(c), the number of cranes required is determined based on the in-situ production duration. The specifications of each crane, such as work radius and lifting capacity, are defined accordingly [38-39]. Based on the number of cranes, zoning plans are established. The zoning plan is established based on the number of cranes. Installation sequence is determined, and installation time is estimated for each component type (columns, beams, slabs). Finally, the installation schedule is simulated according to the construction schedule. In other word, in-situ produced PC components are first arranged in the storage yard and installed in sequence.

2.1. Previous Studies

2.2.1. Integration of BIM and DT in the Construction Industry

BIM has become a foundational platform for construction information management, supporting tasks such as design coordination, scheduling, and resource allocation [

10,

31]. However, BIM traditionally functions as a static system, lacking the ability to reflect real-time conditions on site. To address this limitation, DT technology is increasingly being adopted to create dynamic, real-time representations of physical environments [3-4].

The integration of BIM and DT has significantly improved decision-making across the project lifecycle by enhancing visualization, operational control, and performance monitoring. For instance, Opoku et al. (2021) utilized DT to improve site visibility and adaptive decision-making [

37], while Kassem et al. (2022) applied IoT-based DT frameworks for real-time equipment tracking [

40]. Other studies, such as those by Xu et al. (2024) have reviewed the technical challenges and strategic benefits of integrating digital technologies in construction [

41].

Importantly, recent research has expanded DT applications to include environmental impact assessment through Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Chen et al. (2021) [

42], Tagliabue et al. (2023) [

43] and Alizadehsalehi et al. (2021) [

44] demonstrate how DT can be linked to LCA metrics to promote low-carbon construction and compliance with environmental regulations.

Lu et al. (2020) further illustrated the value of integrating sensor data into BIM-DT systems to enable anomaly detection in facility monitoring [

11]. Opoku et al. (2021) emphasized the use of real-time data from IoT and machine learning models to enhance the predictive capabilities of DT [

37]. According to Xu et al. (2024), the transition from BIM to DT represents a fundamental evolution in construction workflows, one that enables system-wide intelligence and predictive control [

41].

2.2.2. DT for Predictive Planning and Risk Management

DT’s core strength lies in its ability to simulate future scenarios and support proactive decision-making in complex environments. For example, Lu et al. (2020) developed a DT-based approach to improve coordination and productivity in on-site construction processes[

11]. Zhang et al. (2024) applied DT for real-time environmental monitoring and integrated lifecycle carbon footprint analysis into planning workflows [

45].

Case studies have shown that time and cost management of 4D and 5D BIM models has enabled stakeholders to prepare simulations and predict scenarios for resource optimization [

46]. It can also play a critical role in establishing predictive maintenance and energy management strategies [

47]. In the port area, this process has led to strategic asset management for risk and safety management activities [48-49].

More recently, scenario-based and probabilistic simulation tools have been embedded within DT frameworks. Bakhshi et al. (2024) introduced a DT platform that incorporates simulation techniques for proactive risk mitigation and emission tracking [

50]. The integration of optimization algorithms with DT has proven especially useful in improving the responsiveness and reliability of construction project control systems.

2.2.3. On-site Precast Concrete Production and Stockyard Management

Effective management of in-situ production and temporary storage is critical in precast construction, where just-in-time assembly and spatial optimization are essential. Kosse et al. (2020) proposed a simulation-based model for optimizing yard layout in precast construction [

51], while Lim and Kim (2024) explored the integration of scheduling and spatial constraints in PC logistics planning [

21].

However, many existing models remain static and are not responsive to real-time conditions. To overcome this limitation, it is essential to incorporate sensor inputs and intelligent simulation platforms within DT systems. Environmental optimization is an area that has not yet been adequately addressed in the literature.

2.2.4. Reducing carbon emissions using DT

Recent advancements in DT technologies have demonstrated substantial potential in reducing carbon emissions across the entire lifecycle of built environments. Several studies have shown that integrating DT with real-time sensing and AI-driven analytics enables dynamic monitoring and optimization of energy usage and CO₂ emissions in both construction and operation phases [52-53]. For instance, cognitive digital twins applied to HVAC systems in smart buildings have achieved up to 30–50% carbon reduction by adapting to occupant behavior and environmental conditions [

54]. Moreover, city-scale digital twin platforms, such as those implemented in Sydney and the European "Destination Earth" project, allow for urban-level simulation of emission sources and inform sustainable policy planning [

55]. These findings underscore the importance of embedding DT-enabled carbon intelligence within construction workflows, from design to operation, as a pathway to achieving low-carbon and climate-resilient infrastructure.

2.2.5. Research Gap

Despite growing interest in DT applications, there remains a lack of fully integrated BIM-DT systems specifically tailored to the complexities of precast concrete logistics. In particular, few frameworks support simulation-based optimization of CO₂ emissions in tandem with production and yard management. This study aims to address this gap by proposing a unified platform that enables environmentally conscious decision-making for in-situ PC component production.

3. Methodology

In general, DT is considered as a virtual mirror that describes the physical characteristics of the system, and transmits and receives information for control, monitoring, and decision-making processes [

56]. DT should be connected and synchronized while running simulations of physical counterparts over time. DT is defined as a model that pairs physical and digital models by automatically exchanging data between physical and digital [

57].

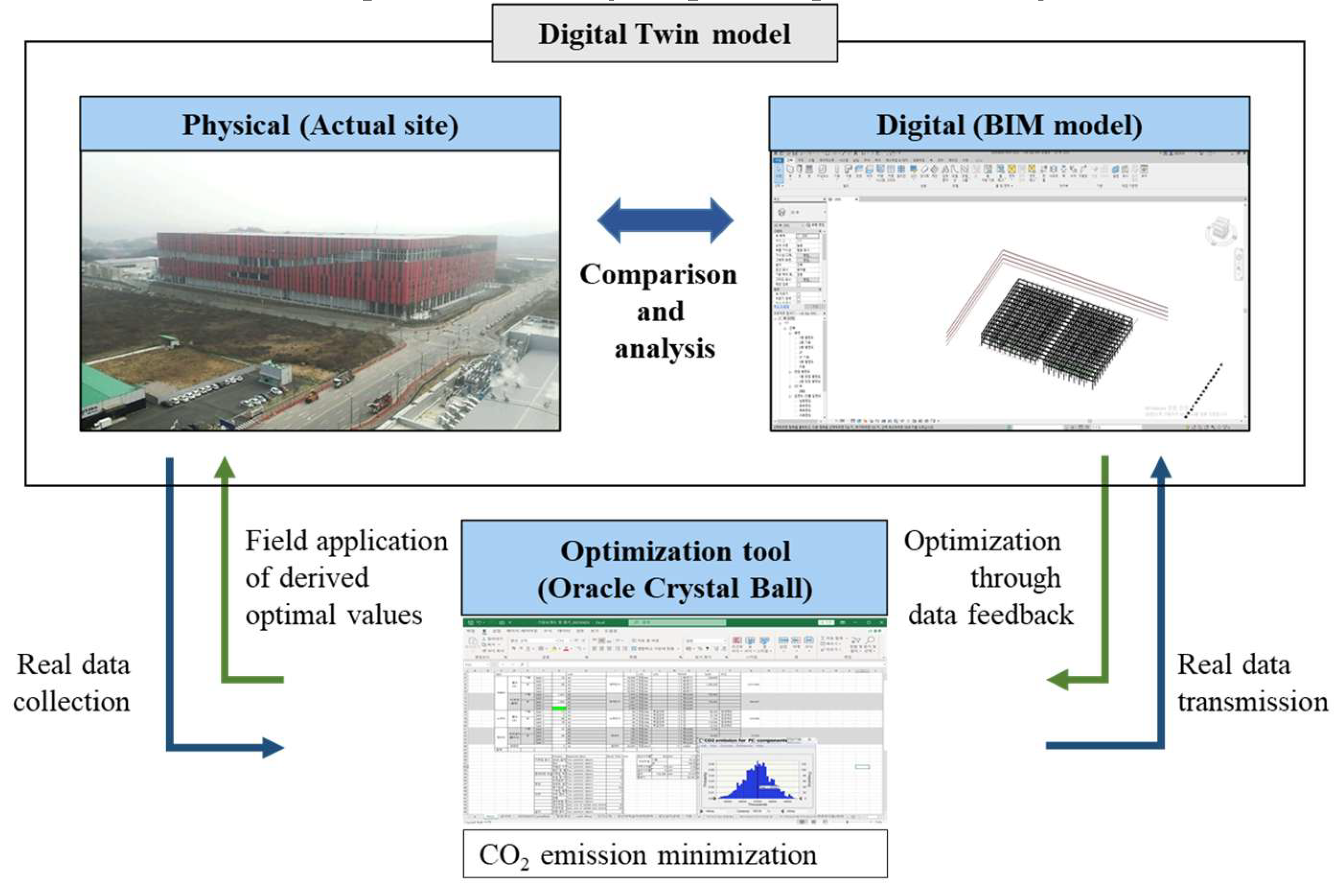

However, in this study, we apply DT technology that is different from general models by using an optimization tool. The conceptual diagram in

Figure 2 shows a framework for efficiently managing the in-situ production and installation of PC structures based on DT technology, while achieving sustainability (carbon reduction) goals at the same time. The DT model consists of a bidirectional link between the actual physical site and the BIM-based DT that virtually implements it. BIM model is updated based on real-time on-site data using Dynamo, and simulation and analysis are possible through BIM model.

The digital twin system is linked to optimization tools such as Oracle Crystal Ball to achieve the goals of minimizing carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions. The optimization tool uses information derived from the BIM model and actual field data to perform sensitivity analysis and control variable settings, thereby deriving the optimal scenario. The results are fed back into the digital twin model and reflected in field decision-making, continuously improving the accuracy of the model.

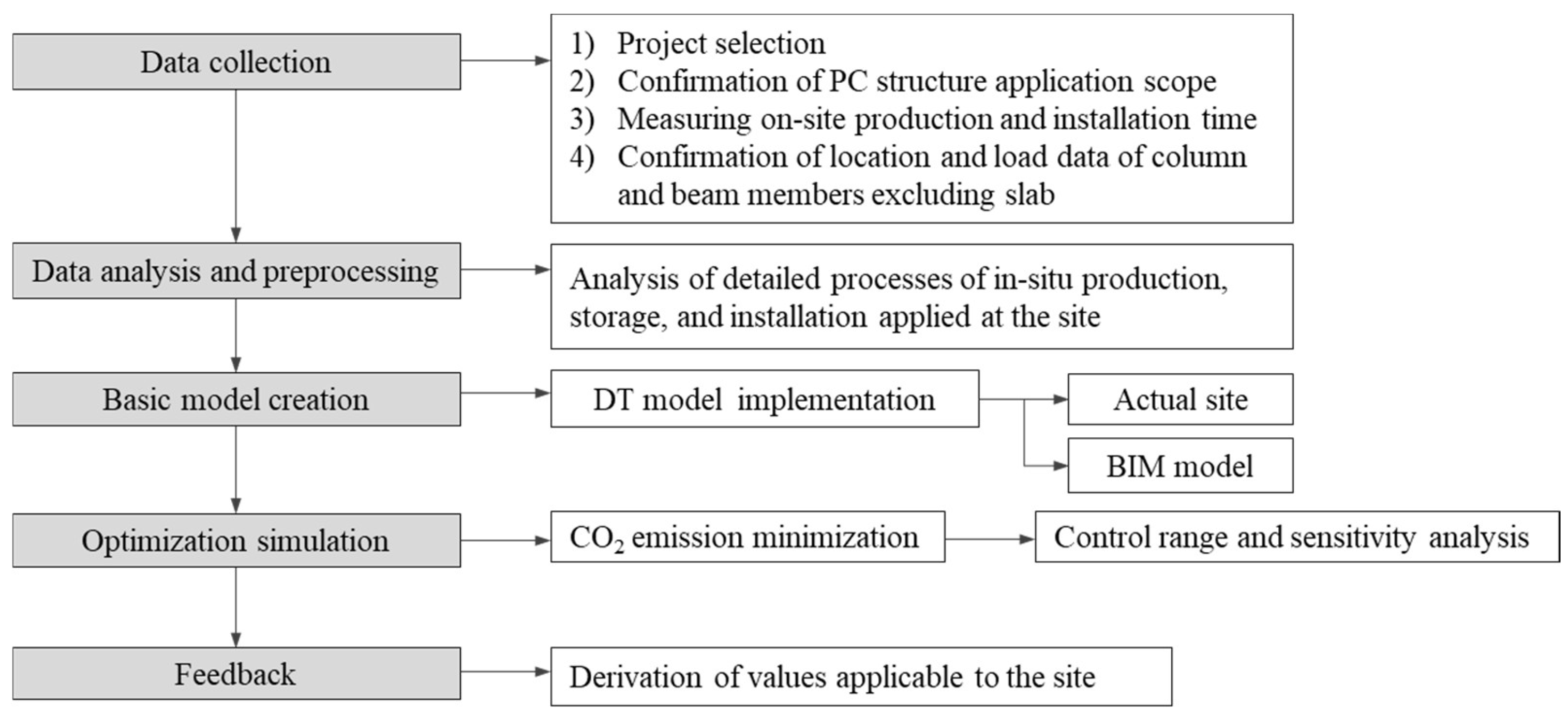

Based on the concept, the methodology of this study is as shown in

Figure 3.

1) In the data collection stage, a project is selected and the scope of application of PC structures is confirmed. And the actual production and installation time is measured on-site, and the location and load data of the column and beam members excluding the slab are collected.

2) In the data analysis and preprocessing stage, the detailed procedures of the production, storage, and installation processes applied on-site are analyzed based on the collected information.

3) In the basic model creation stage, DT model is implemented and linked with actual site information and BIM models. The model is used for simulation-based optimization.

4) In the optimization simulation stage, the goal is to minimize CO₂ emissions. For this, simulation-based analysis tool such as Oracle Crystal Ball is utilized. And the range of control variables is set for each scenario, and sensitivity analysis is analyzed to increase the reliability and efficiency of the results.

5) In the feedback stage, the optimal values applicable to the actual site are derived from the simulation results, and these are fed back into the model to enable iterative improvement.

4. Case Application of BIM-Based In-situ Production

4.1. Selection of the Case Project

To validate the effectiveness and practical applicability of the proposed BIM-based DT framework, a real construction project was selected as a case study. The project involves the construction of a large-scale logistics warehouse located in A City. The structure consists of four above-ground floors, with PC slabs installed from Level 1 to Level 4. The building’s core structure is composed of reinforced concrete (RC), and the ramp areas utilize a combination of steel and SRC systems. This study focuses primarily on the PC slab construction processes across the four floors.

4.44. D Simulation Using BIM

The

Table 1 shows the assumption for 4D simulation using BIM. The total cost and time are not considered because it satisfies the client's requirements. All PC components are in-situ produced, stored, and installed. The PC member production and storage location can always be located near the installation location. As this site has a large floor area and a low number of floors, it is difficult to use a tower crane. Hence, a mobile crane is used.

The

Table 2 shows the constraints for 4D simulation using BIM. To minimize environmental loads, unnecessary secondary transportation should be avoided, and equipment utilization should be limited to prevent excessive energy consumption. Formworks are assumed to be reused at least 40–50 times to reduce environmental impacts from material production and disposal. Furthermore, the production and storage of all columns and beams, as well as the installation of all columns, beams, and slabs, must be incorporated.

For efficient in-situ production and yard layout, implementation of DT using BIM and optimal space planning strategies based on time series analysis are required. These values were established based on actual site conditions during the preparation stage for in-situ production. The assumption conditions of the main factors for BIM implementation are as shown in

Table 3. This is a value that was reflected considering the on-site conditions during the on-site production preparation stage. The required construction period presented by the client is 18 months, and the applied quantity is 1,035ea of columns and 1,906ea of beams.

And the number of molds applied is 32ea for columns and 90ea for beams. Two cranes were assigned, corresponding to the number of designated work zones. The maximum yard storage area derived by reflecting these conditions was calculated to be 15,235㎡. The construction period applied on site is set at 8 months to comply with the client's requested conditions. The factors used as parameters are quantity, number of molds, and number of cranes.

The number of required molds is calculated based on production quantity, production cycle, and total production duration. Similarly, the number of cranes is determined by the unit erection time, total installation quantity, and allowable erection period. The total yard area is estimated by multiplying the number of stored components by the unit yard area per component type. These calculations are formalized in Equations (1) through (4).

Q

s: in-situ production quantity, Q

sc: column quantity in-situ production, Q

sb: beam quantity in-situ production

Nm: number of molds;

QMi: in-situ production quantity of each mold type;

TPC: production cycle time;

Ts: in-situ production time;

i: number of mold types (1, … , n).

NC : number of cranes; ;

TUE: unit erection time

QS : in-situ production quantity;

Te: erection time

AYS: yard stock area, QYSi: yard stock quantity of each mold type, AUYSi: unit yard stock area of each mold type, i :number of mold types(1, … , n))

The production and yard-stock areas for a unit area are calculated in real time as shown in the

Table 3 using Dynamo. The following Equations (5) and (6) were applied for the area. The production area, installation area, and yard-stock area for one member are 16.5㎡ and 9.6㎡, respectively. The maximum yard-stock area of 15,235㎡ was derived in real time at lead-time M+5. The reason why the highest number of yard-stock members is shown during this period is because the PC members produced during the lead-time were accumulated. And since the yard-stock members are installed, the number of PC members decreases as they are installed. The period from M+6 to M+8 means time-lag and is 3 months. That is, when construction begins, the yard-stock area gradually increases, and the largest yard-stock area is recorded just before the start of installation (M+6). And when installation begins, the yard-stock area decreases, and when the area becomes 0, the PC construction is finished. Monthly area are consistent with those presented in our parallel study [

58].

Table 3.

Monthly area (unit: 1,000㎡).

Table 3.

Monthly area (unit: 1,000㎡).

| Monthly area |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

| Production area |

12.1 |

12.1 |

12.1 |

12.1 |

12.1 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Yard stock area |

2.8 |

5.7 |

8.5 |

11.3 |

13.9 |

8.2 |

4.1 |

0.0 |

Ap(t): In-situ production area occupied at time t, Ay(t): Yard-stock area occupied at time t, Si: Production start date of the ith component, Ei: Production completion date of the ith component, Ii: Installation date of the ith component

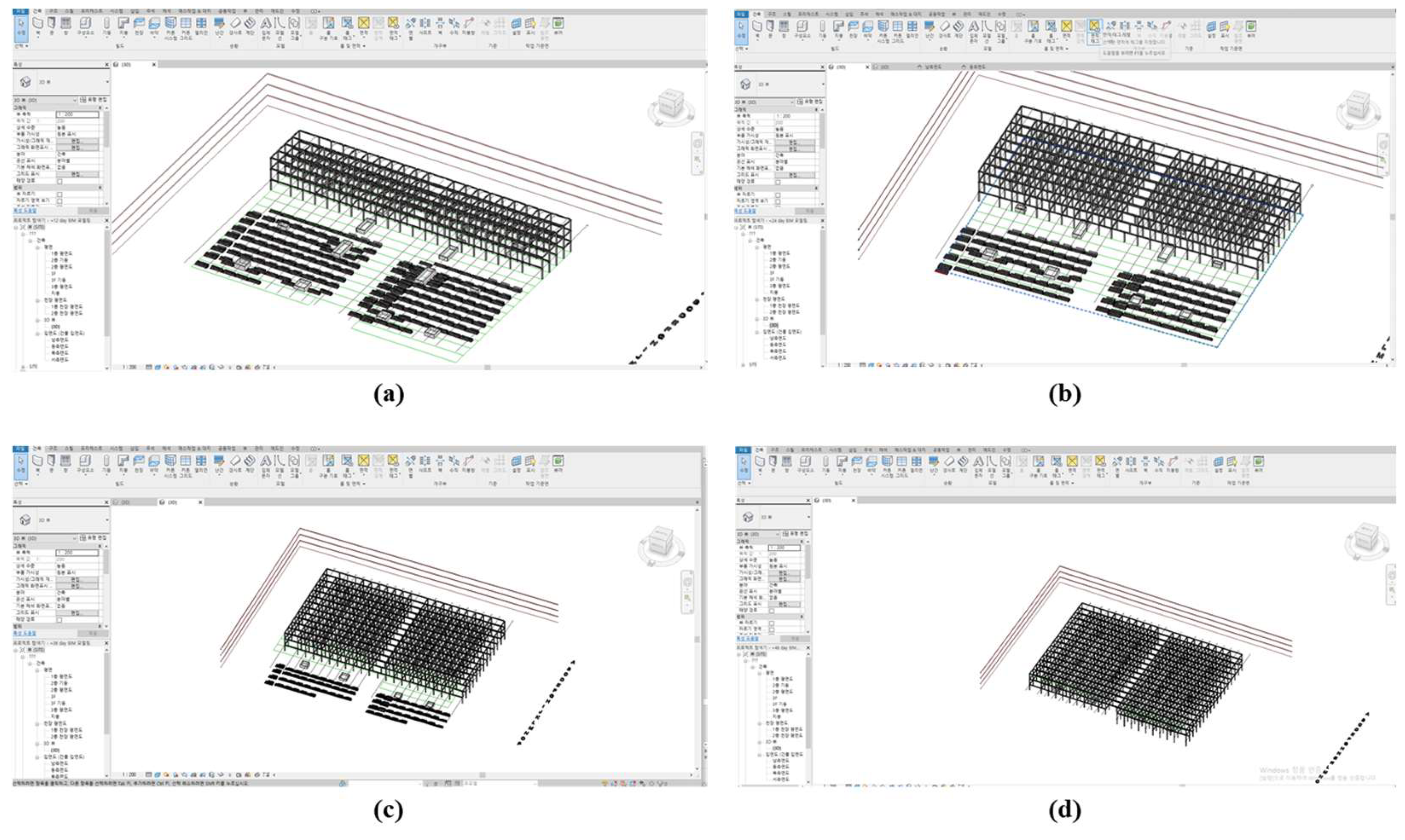

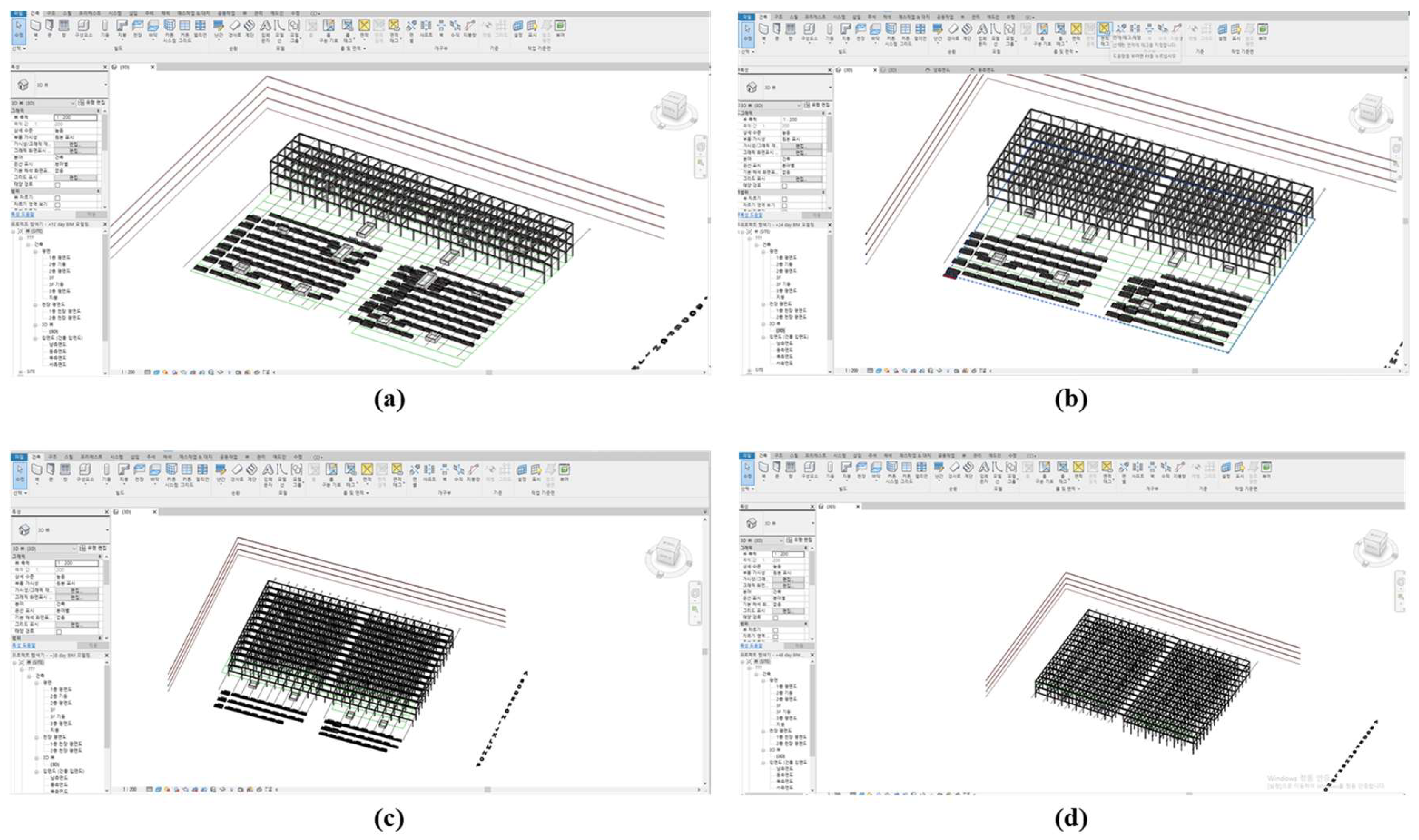

Figure 4 shows a BIM model implemented using Dynamo. A Dynamo script was created to obtain real-time information, and the BIM model was structured based on the IFC schema to ensure data consistency and interoperability. The IFC class and property set assigned to the selected member in the BIM model can be retrieved.

Figure 5 shows the 4D simulation after the installation of PC members has started, built using BIM. PC members are not installed during the lead time from M+1 to M+5. Therefore, only the construction from M+6 to M+8 is shown. In M+6 (D+12), the production areas of zone A and B are 630㎡ and 580㎡ in real time using Dynamo, respectively, and the yard-stock areas of zone A and B are 7,124㎡ and 6,812㎡ in real time, respectively. In the case of a general in-situ production system, since the erection area is added, it is difficult to produce and store PC members in the same location, so the production and yard-stock locations can have to be moved. However, in this study, only the production location was moved, and the yard-stock location was set up to be the closest location to the installation location. Monthly site plan using BIM are consistent with those presented in our parallel study [

58].

5. CO₂ Emission Optimization

Lim et al. (2020) [

38] explained six assumptions about the available area selected as the main influencing factor, and derived the highest cost reduction rate among the scenarios applicable to the field. In addition, Lim et al. (2020) [

39] derived Min and Max for each factor such as in-situ production quantity, lead time, number of molds, and number of cranes, and analyzed the effect of quantity on cost and CO₂. However, this study assumes that all members are produced, and derives factors affecting the process and CO₂ emission. In addition, the goal of this study is to reduce environmental loads by 10%.

Based on the quantity data extracted from the BIM model, this study presents a procedure for quantifying and optimizing CO₂ emissions generated during the production and yard storage of PC components using Oracle Crystal Ball. Carbon emissions at construction sites vary sensitively depending on the distance traveled by materials, equipment operation time, yard density, and work waiting time. However, this study focuses on the main factors of in-situ production. CO₂ emissions are calculated using actual labor inputs, along with oil and electricity consumption during the production and storage processes. The objective function for CO₂ emission optimization, as well as the CO₂ emission calculation formulas, are provided in Equations (7)–(9).

: total CO₂ emission, : CO₂ emission of column, : CO₂ emission of beam, : ith column quantity, : unit CO₂ emission of labor, : unit CO₂ emission of oil, : unit CO₂ emission of electricity, : unit CO₂ emission of lighting and heating, : unit CO₂ emission of environmental conservation, : ith beam quantity, : Number of installed ith column (1, … , n), : Number of installed ith beam (1, … , m)

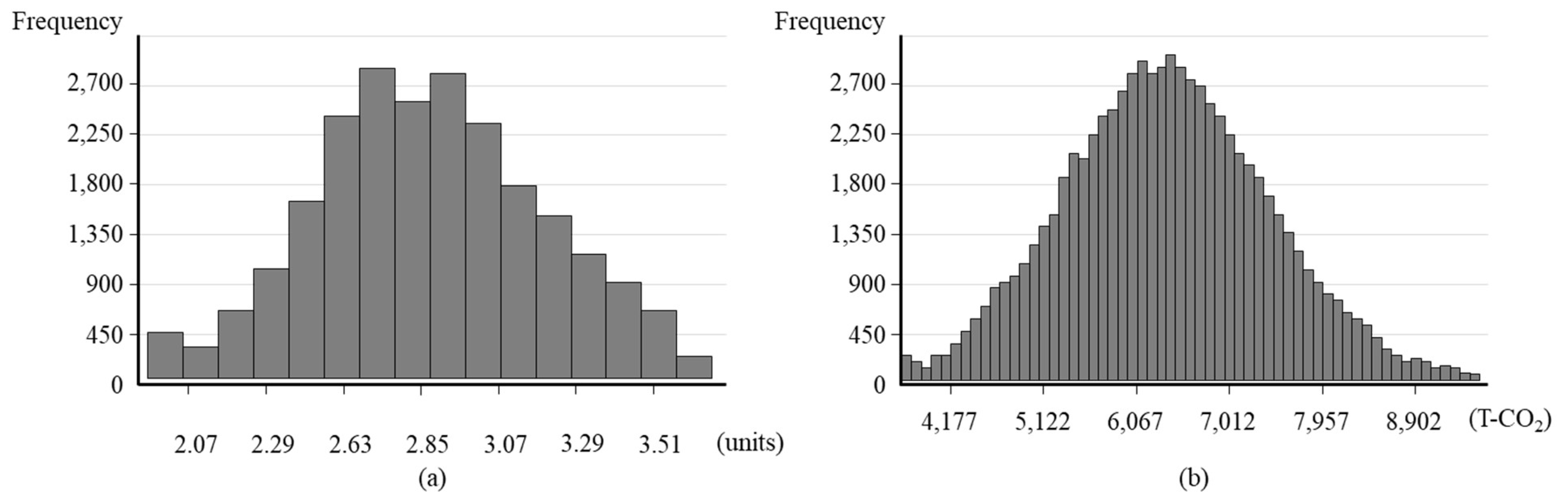

In the same way as schedule optimization, CO₂ emission optimization was performed through maximum repetition simulation (1,000,000 times) in the Oracle Crystal Ball program. All possible cases of crane and CO₂ occurrence were derived to derive Min and Max for each factor. The factors used as parameters at this time were quantity, production cycle, lead-time, number of molds, and number of cranes. As a result of deriving the Min-Max management range of the crane as shown in the following

Figure 6, Min was set to 2.00 ea and Max was set to 3.270 ea. The reason why the crane does not decrease below 2.00 months is because the minimum number of cranes is required to match the process. And CO₂ emission was estimated as Min 35,352 T- CO₂ and Max 97,244 T-CO₂. As a result of analyzing the management range, the crane and CO₂ emission according to the change in each factor were generally proportional, so they appeared in a graph of a similar shape.

Using the management scope of crane and CO₂ emission derived through Monte Carlo simulation, the optimal case is derived as shown in

Table 4. CO₂ emission is derived in real time as 40,423 T- CO₂, construction time is 6.5 months, and this value is the smallest value among the derived CO₂ emission values. The number of molds is 30 columns, 91 beams, number of cranes is 2, and yard-stock area is 15,729㎡. And when the derived values are applied to the DT model and explained in

Figure 5, (a) is modified to D+11, (b) to D+20, (c) to D+29, and (d) to D+38. And

Figure 7 shows this. Through the results, it is analyzed that CO₂ emission increases as the number of cranes increases, which means that the crane is a factor that increases CO₂ emission. In the future, the values of various factors can be determined on site considering the minimum CO₂ emission by considering various factors. The number of forms according to the yard-stock area is derived, and the lead time and total construction period applied to the number of forms are derived, and the yard-stock area is calculated. CO₂ emissions were calculated by applying these results step by step.

Table 5 shows the sensitivity analysis. The number of cranes and CO₂ emissions exhibited the most pronounced correlation (r ≈ 0.48). This result indicates that equipment operation is directly associated with increased energy consumption and carbon emissions. It also implies that as the number of cranes increases, additional waiting time between tasks can be required, thereby extending idle periods. Furthermore, project duration showed a negative correlation with yard-stock area (r ≈ -0.12), suggesting that longer durations tend to improve yard efficiency and reduce spatial occupation. The relationships among the remaining variables were weak, and duration and CO₂ emissions appeared largely independent. The algorithms employed to derive the final optimal values are provided in

Figure A1 of

Appendix A.

6. Discussion.

This study proposes a BIM-based DT framework for optimizing in-situ production and storage management of PC components. Oracle Crystal Ball simulation was used to perform probabilistic CO₂ emissions optimization. The results showed that the environmental impact can be reduced by 8.7%.

While this study focuses on optimizing both construction duration and carbon emissions, it is essential to acknowledge the potential trade-off between these objectives. Shortening construction duration may increase CO₂ emissions as more equipment and resources are required. On the other hand, reducing equipment operation time to reduce CO₂ emissions can require an extension of the construction period. Accelerating the schedule can lead to increased carbon emissions due to intensified equipment use, while minimizing emissions can require extended timelines. Therefore, A multi-objective optimization model was considered, and ranging most eco-friendly, were introduced to support informed decision-making.

And in this study, SRC precast components were applied. In previous studies, it was found that SRC precast components can reduce the construction period by at least 18.7% compared to RC structure precast components [59-60] and emit at least 11.7% less CO₂ [61-62]. If process optimization is applied to actual sites, it is expected that CO₂ emissions will be minimized up to 8.7%.

7. Conclusion

This study proposed a BIM-based DT framework to optimize in-situ production, yard-stock management, and installation of PC components in large-scale construction projects. By integrating probabilistic simulation with BIM-derived data based on data actually applied in the field, the framework effectively addressed the core constraints of environmental impact within a unified digital environment.

Using Oracle Crystal Ball, the study conducted Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate CO₂ emissions. CO₂ emissions were optimized to 40,423 T-CO₂, with a construction time of 6.5 months, highlighting the significant environmental benefits achievable through intelligent layout and production planning. Notably, increased crane use was associated with higher carbon output, indicating that equipment operation is a key driver of environmental load.

Overall, the results validate the feasibility of predictive and simulation-driven planning in managing complex construction variables. By enabling real-time synchronization of production, yard layout, and installation processes, the proposed framework contributes to more sustainable and resilient construction strategies. This study was conducted by utilizing data actually applied in the field and presenting assumption conditions. The optimization model can be used to control carbon emissions, and the DT model can be used to reflect real-time feedback in the field.

From an academic perspective, this research advances the application of DT in construction by holistically integrating environmental performance into a single model. Practically, it provides actionable insights for project managers and policy makers seeking to implement smart, low-carbon construction practices. However, the findings are limited to a single case project and do not yet incorporate real-time sensor feedback or automated 3D yard modeling.

Future research should focus on expanding the applicability of the framework by:

Integrating real-time sensor data for dynamic feedback control,

Applying machine learning techniques to improve CO₂ emission forecasting,

Enhancing safety and risk management through predictive analytics, and

Developing cloud-based visualization dashboards for intelligent site monitoring.

By addressing these directions, the framework can evolve into a fully autonomous, adaptive DT system capable of supporting the next generation of sustainable construction management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and J.L.; methodology, J.L.; software, J.P. and J.L.; validation, J.L.; formal analysis, J.P. and J.L.; investigation, S.K. and J.L.; resources, J.P., S.K. and J.L.; data curation, J.P. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.P., S.K. and J.L.; visualization, J.L.; supervision, S.K. and J.L.; project administration, S.K. and J.L.; funding acquisition, S.K. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MOE) (No. 2021R1C1C2094527 and No. 2022R1A2C2005276).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DT |

Digital Twin |

| BIM |

Building Information Modeling |

| PC |

Precast concrete |

| SRC |

Steel-reinforced concrete |

| RC |

Reinforced concrete |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Algorithms for the process of deriving the selected optimal CO₂ emission.

Figure A1.

Algorithms for the process of deriving the selected optimal CO₂ emission.

References

- Merschbrock, C., & Munkvold, B. E. (2024). The digital transformation of the construction industry: A review. Industrial and Commercial Training, 56(2), 123–140. [CrossRef]

- Nyqvist, R., Peltokorpi, A., Lavikka, R., & Ainamo, A. (2025). Building the digital age: management of digital transformation in the construction industry. Construction Management and Economics, 43(4), 262-283. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q., & Tao, F. (2021). Digital twins and big data towards smart manufacturing and Industry 4.0: 360-degree comparison. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 59, 101542. [CrossRef]

- Boje, C., Guerriero, A., Kubicki, S., & Rezgui, Y. (2020). Towards a semantic construction digital twin: Directions for future research. Automation in Construction, 114, 103179. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.-H., & Kim, G.-H. (2024). Development of BIM Utilization Level Evaluation Model in Construction Management Company. Korean Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 25(4), 24–33. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J., Song, S. H., Lee, C., Ahn, H., Cho, H., & Kang, K.-I. (2024). BIM and OpenAI-based Model for Supporting Initial Construction Planning of Bridges and Tunnels. Korean Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 25(6), 24–33. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H., & Seong, H. (2025). Conceptual Model for Quality Risk Assessment and Reserve Cost Estimation for Construction Projects based on BIM. Korean Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 26(2), 62–71. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., & Nam, J. (2025). Applying BIM Standard Guideline to Expressway BIM Results and Drawing its Improvement Measure for Project Management. Korean Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 26(2), 82–88. [CrossRef]

- Kim, I., & Shah, S. H. (2025). A Proposal for Evaluation Criteria of Decision Support System for BIM. Korean Journal of Con-struction Engineering and Management, 26(2), 89–102. [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R., Brilakis, I., Pikas, E., Xie, H. S., & Girolami, M. (2020). Construction with digital twin information systems. Da-ta-Centric Engineering, 1, e14. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q. , Parlikad, A. K., Woodall, P., Ranasinghe, G. D., Xie, Y., Liang, Z., & Konstantinou, E. (2020). Developing a digital twin at building and city levels: Case study of West Cambridge campus. Journal of Management in Engineering, 36(3), 05020004. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Li, M., Guo, D., Wu, W., Zhong, R. Y., & Huang, G. Q. (2022). Digital twin-enabled smart modular integrated con-struction system for on-site assembly. Computers in Industry, 136, 103594. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., Zhao, N., Sun, L. et al. Modular based flexible digital twin for factory design. J Ambient Intell Human Comput 10, 1189–1200 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Al-Kahwati, K., Birk, W., Nilsfors, E. F., & Nilsen, R. (2022, June). Experiences of a digital twin based predictive maintenance solution for belt conveyor systems. In PHM Society European Conference (Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 1-8). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Tan, Y., & Zhang, A. (2023). Integrating digital twin and blockchain for smart building management. Sustainable Cities and Society, 99, 104514. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Kim, J.J. Dynamic optimization model for estimating in-situ production quantity of PC members to minimize envi-ronmental loads. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.-K.; Lee, G.; Lee, S.; Kim, S. Algorithms for in-situ production layout of composite precast concrete members. Autom. Constr. 2014, 41, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Y.J.; Kim, S.K. A process for the efficient in-situ production of precast concrete members. J. Reg. Assoc. Archit. Inst. Korea 2017, 19, 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C. Construction Planning Model for In-situ Production and Installation of Composite Precast Concrete Frame. Ph.D. Thesis, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.; Son, C.-B.; Kim, S. Scenario-based 4D dynamic simulation model for in-situ production and yard stock of precast concrete members. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2022, 22, 2320–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J., & Kim, S. (2024). Environmental Impact Minimization Model for Storage Yard of In-Situ Produced PC Components: Comparison of Dung Beetle Algorithm and Improved Dung Beetle Algorithm. Buildings, 14(12), 3753. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.T.; Lee, M.S. A Study on the Site-production Possibility of the Prefabricated PC Components. In Proceeding of the 1992 Autumn Annual Conference of the Architectural Institute of Korea, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1992 Oct 24, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1992; Volume 12, pp. 629–636.

- Li, H.; Love, P.E. Genetic search for solving construction site-level unequal-area facility layout problems. Autom. Constr. 2000, 9, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, I.; Na, Y.; Kim, J.T.; Kim, S. Energy-efficient algorithms of the steam curing for the in situ production of precast concrete members. Energy Build. 2013, 64, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, G.; Kang, K. A Study on the effective inventory management by optimizing lot size in building construction. J. Korea Inst. Build. Constr. 2004, 4, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Yu, J.H.; Kim, C.D. A Economic Order Quantity (EOQ) Determination Method considering Stock Yard Size; Korea Institute of Construction Engineering and Management, , Seoul, Republic of Korea: 2007; pp. 549–552.

- Lee, J.M.; Yu, J.H.; Kim, C.D.; Lee, K.J.; Lim, B.S. Order Point Determination Method considering Materials Demand Variation of Construction Site. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 2008, 24, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, H.R.; Horman, M.J.; Minchin, R.E.; Chen, D. Improving labor flow reliability for better productivity as lean con-struction principle. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2003, 129, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.-S.; Yu, J.-H.; Kim, C.-D. Economic Order Quantity(EOQ) Determination Process for Construction Material considering Demand Variation and Stockyard Availability. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2011, 12, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, D. W., Sourani, A., Sertyesilisik, B., & Tunstall, A. (2013). Sustainable construction: analysis of its costs and benefits. American Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture, 1(2), 32-38.

- Volk, R., Stengel, J., & Schultmann, F. (2014). Building Information Modeling (BIM) for existing buildings—Literature review and future needs. Automation in Construction, 38, 109–127. [CrossRef]

- Osman, H.M.; Georgy, M.E.; Ibrahim, M.E. A hybrid CAD-based construction site layout planning system using genetic al-go-rithms. Autom. Constr. 2003, 12, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Lam, K.-C.; Lam, M.C.-K. Dynamic construction site layout planning using max-min ant system. Autom. Constr. 2009, 19, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahman, H.; Wang, C.; Eng, K.S. Repertory grid technique in the development of Tacit-based Decision Support System (TDSS) for sustainable site layout planning. Autom. Constr. 2011, 20, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.J. A Study of In-situ Production Management Model of Composite Precast Concrete Members. Ph.D. Thesis, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.; Kim, S. Evaluation of CO2 Emission Reduction Effect Using In-situ Production of Precast Concrete Components. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2020, 19, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, D. G. J., Perera, S., & Osei-Kyei, R. (2021). "Digital Twins for the Built Environment: Learning from Conceptual and Process Models in Manufacturing." Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, 10(4), 557–575.

- Lim, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.J. Dynamic simulation model for estimating in-situ production quantity of pc members. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 18, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Park, K.; Son, S.; Kim, S. Cost reduction effects of in-situ PC production for heavily loaded long-span buildings. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2020, 19, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, M., Kelly, G., Dawood, N., Serginson, M., & Lockley, S. (2015). "BIM in Facilities Management Applications: A Case Study of a Large University Complex." Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 5(3), 261–277.

- Xu, Q., Wang, J., Gao, W., Ren, S., & Li, Z. (2024, October). Digital Twin: State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives. In Pro-ceeding of the 2024 5th International Conference on Computer Science and Management Technology (pp. 731-740).

- Chen, C., Zhao, Z., Xiao, J., & Tiong, R. (2021). A conceptual framework for estimating building embodied carbon based on digital twin technology and life cycle assessment. Sustainability, 13(24), 13875.

- Tagliabue, L. C., Brazzalle, T. F., Rinaldi, S., & Dotelli, G. (2023). Cognitive Digital Twin Framework for Life Cycle Assessment Supporting Building Sustainability. In Cognitive Digital Twins for Smart Lifecycle Management of Built Environment and In-frastructure (pp. 177-205). CRC Press.

- Alizadehsalehi, S., Hadavi, A., & Huang, J. C. (2021). "From BIM to Extended Reality in AEC Industry." Journal of Information Technology in Construction (ITcon), 26, 1–17.

- Zhang, Z., Wei, Z., Court, S., Yang, L., Wang, S., Thirunavukarasu, A., & Zhao, Y. (2024). A review of digital twin technologies for enhanced sustainability in the construction industry. Buildings, 14(4), 1113. [CrossRef]

- Agostinelli, S., Cinquepalmi, F., and Ruperto, F. (2019). 5D BIM: tools and methods for digital project construction management. WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, 192, 205-215. [CrossRef]

- González, J., Soares, C. A. P., Najjar, M., and Haddad, A. N. (2021). BIM and BEM methodologies integration in ener-gy-efficient buildings using experimental design. Buildings, 11(10), 491. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F., Baptista, J. S., & Pinto, D. (2022). BIM approach in construction safety—A case study on preventing falls from height. Buildings, 12(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Muzi, F., Marzo, R., & Nardi, F. (2022). Digital information management in the built environment: Data-driven approaches for building process optimization. In International Conference on Technological Imagination in the Green and Digital Transition (pp. 123-132). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, S. , Ghaffarianhoseini, A., Ghaffarianhoseini, A., Najafi, M., Rahimian, F., Park, C., & Lee, D. (2024). Digital twin applications for overcoming construction supply chain challenges. Automation in Construction, 167, 105679. [CrossRef]

- Kosse, S., Forman, P., Stindt, J., Hoppe, J., König, M., & Mark, P. (2023, June). Industry 4.0 enabled modular precast concrete components: a case study. In International RILEM Conference on Synergising expertise towards sustainability and robustness of CBMs and concrete structures (pp. 229-240). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Wang, Q., Yin, Y., Chen, Y., & Liu, Y. (2024). Carbon peak management strategies for achieving net-zero emissions in smart buildings: Advances and modeling in digital twin. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 64, 103661. [CrossRef]

- Filippova, E., Hedayat, S., Ziarati, T., & Manganelli, M. (2025). Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twins for Bioclimatic Building Design: Innovations in Sustainability and Efficiency.

- Hosamo, H., Hosamo, M. H., Nielsen, H. K., Svennevig, P. R., & Svidt, K. (2023). Digital Twin of HVAC system (HVACDT) for multiobjective optimization of energy consumption and thermal comfort based on BIM framework with ANN-MOGA. Ad-vances in building energy research, 17(2), 125-171. [CrossRef]

- Sohail, A., Shen, B., Cheema, M. A., Ali, M. E., Ulhaq, A., Babar, M. A., & Qureshi, A. (2025). Beyond data, towards sus-tainability: A sydney case study on urban digital twins. PFG–Journal of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Geoinformation Science, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Tharma, R., Winter, R., & Eigner, M. (2018). An approach for the implementation of the digital twin in the automotive wiring harness field. In DS 92: Proceedings of the DESIGN 2018 15th International Design Conference (pp. 3023-3032). [CrossRef]

- Kritzinger, W., Karner, M., Traar, G., Henjes, J., & Sihn, W. (2018). Digital Twin in manufacturing: A categorical literature review and classification. Ifac-PapersOnline, 51(11), 1016-1022. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J & Kim, (manuscript in preparation) BIM-Driven Scheduling Optimization for In-situ Production and Yard-stock Integration of Precast Concrete Members.

- Hong, W. K., Park, S. C., Lee, H. C., Kim, J. M., Kim, S. I., Lee, S. G., & Yoon, K. J. (2010). Composite beam composed of steel and precast concrete (modularized hybrid system). Part III: Application for a 19-storey building. The Structural Design of Tall and Special Buildings, 19(6), 679-706. [CrossRef]

- Rajput, B. L., Hussain, M. A., Shaikh, N. N., & Vadodaria, J. (2013). Time and Cost Comparison of Construction of RCC, Steel and Composite Structure Building. IUP Journal of Structural Engineering, 6(4).

- Ghayeb, H. H., Razak, H. A., & Sulong, N. R. (2020). Evaluation of the CO2 emissions of an innovative composite precast concrete structure building frame. Journal of Cleaner Production, 242, 118567. [CrossRef]

- Kudo, S., Kapfudzaruwa, F., Broadhurst, J. L., Edusah, S. E., Awere, K. G., Matsuyama, K., ... & Mino, T. (2019). Moving towards Transdisciplinarity: Framing Sustainability Challenges in Africa. Sustainable Development in Africa: Concepts and Methodological Approaches, 5, 1.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).