1. Introduction

Biomimetics, the practice of drawing inspiration from nature, has received increasing attention in recent years, particularly in the development of antibacterial surfaces. Numerous studies have demonstrated that micro- and nanostructured surface topographies inspired by biological organisms can effectively inhibit bacterial adhesion and exert bactericidal effects by physically disrupting bacterial membranes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The nanopillar structures found on cicada wings are known to promote a Cassie–Baxter wetting state [

11], which reduces bacterial colonization, while their nanoscale protrusions can mechanically rupture bacterial membranes [

1,

4,

5,

6,

12,

13,

14,

15]. These natural structures exhibit antibacterial activity not only due to their chemical composition but also due to their physical topography [

1,

3,

10,

16,

17]. Artificial surfaces such as black silicon, fabricated via reactive ion etching, have been shown to replicate similar bactericidal effects [

2,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. In particular, nanostructured surfaces that combine superhydrophobicity with mechanical bactericidal activity are of great interest for biomedical applications, where preventing bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation is critical.

Various fabrication techniques have been employed to replicate such natural architectures [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32], including photolithography [

3,

33,

34], nanoimprinting [

35,

36], and plasma-based methods [

37,

38,

39]. Photolithography enables sub-100 nm patterning with high precision [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. However, both techniques impose limitations on substrate size and shape and require dedicated equipment, which restricts their practicality for large-scale or irregularly shaped surfaces. Plasma-based processes [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50], on the other hand, often require vacuum (low-pressure) environments, adding further complexity and cost. These factors present challenges for implementing such techniques in everyday or industrially scalable settings.

In this study, we focus on atmospheric-pressure low-temperature plasma (APLTP) as a practical and scalable method for fabricating antibacterial microstructures on polymer surfaces. APLTP enables plasma processing under ambient conditions, reduces equipment complexity, and allows for the treatment of large or irregularly shaped substrates [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. Our previous work demonstrated that APLTP treatment of solvent-cast polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) films can produce hydrophilic surfaces through the formation of micro- and nanostructures originating from pores located on and within the film [

51]. We also showed that APLTP treatment applied to the surface of polyethylene (PE) sheets and the inner walls of PE tubes resulted in ultra-hydrophilic surfaces with excellent antifouling performance against oil-based contaminants, resembling the functionality observed in snail shells [

53,

54,

55]. While such hydrophilic surfaces are effective in fouling prevention, antibacterial applications often demand the coexistence of both sharp-edged nanostructures and water repellency to prevent bacterial adhesion [

2,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

56]. To address this requirement, we introduce an annealing process following APLTP treatment. By thermally shrinking the surface and closing microscopic pores, we aim to restore hydrophobicity while preserving the bactericidal microstructure. This dual approach seeks to maintain sharp-edged topography and enhance the surface's antibacterial performance through controlled wettability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PMMA Film Preparation

The PMMA (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., LLC, MW=15,000) was dissolved in ethyl lactate (Wako first Grade; Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corp.). Its solution concentration was 30 wt%. The solution was spin-coated onto a glass substrate (1 mm thickness, 76×52 mm2, S9111; Matsunami Glass Ind., Ltd.,) using a spin-coater (K-359 S-1; Kyowa Riken Co., Ltd.). The rotation speed of the spin coater was 1800 rpm and the rotation time was 24 s. Pre-baking of the substrate in an oven (CLO-2AH; Koyo Thermo Systems Co., Ltd.) at 100 °C for 60 s. The initial film thickness was measured using a surface profiler (Surfcom 480A; Tokyo Seimitsu Co., Ltd.). The initial PMMA film thickness was about 5 µm.

2.2. Plasma Treatment

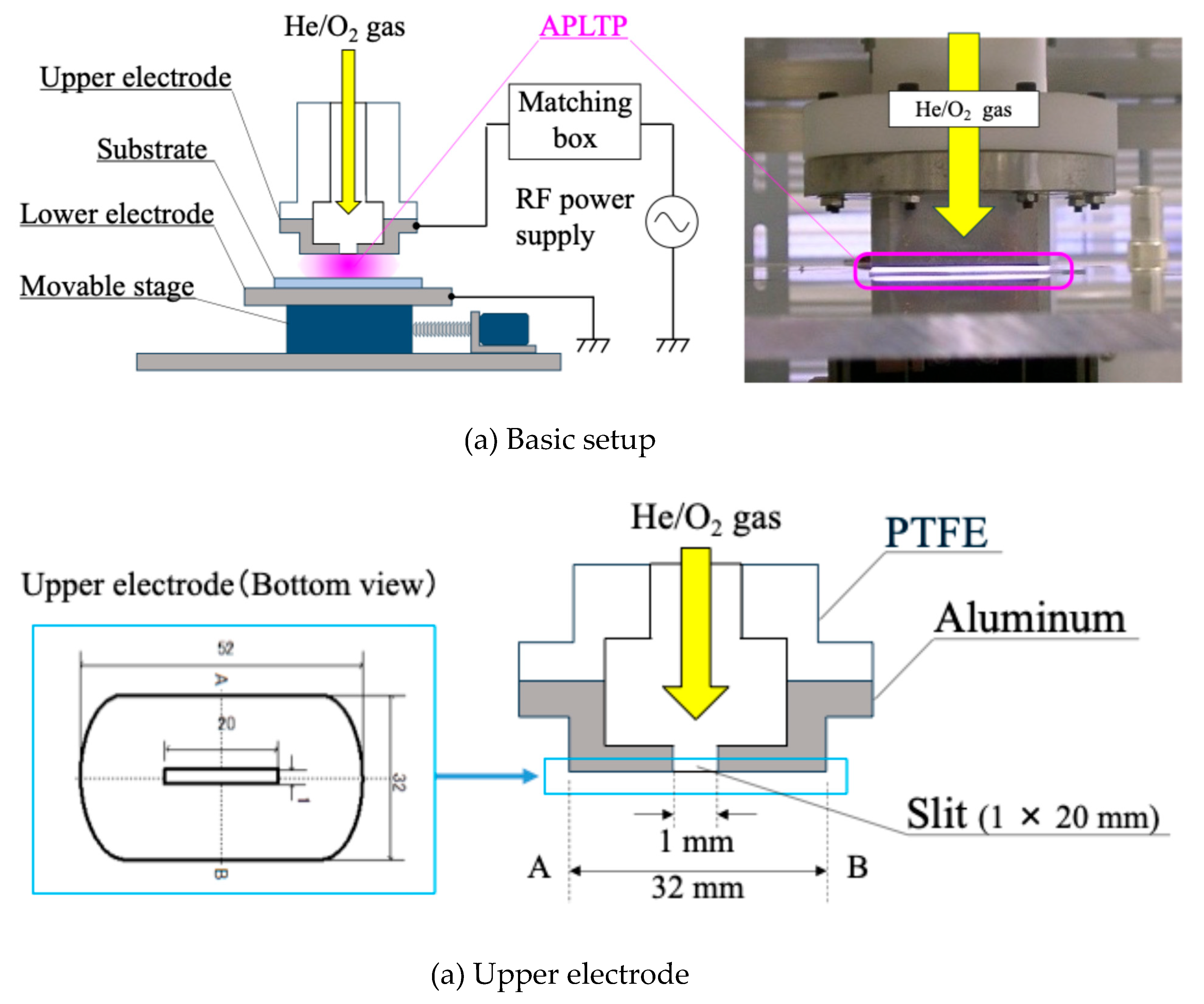

PMMA coated substrate was irradiated with atmospheric-pressure low-temperature plasma.

Figure 1 portrays the plasma treatment equipment diagram. The He gas (≥99.99%; Takamatsu Teisan Co.) flow rate was fixed at 2.0 slm using a mass flow controllers (SEC-400MK3; STEC Inc.). The O

2 gas (≥99.5%; Iwatani Sangyo Corp.) flow rate was fixed at 60 sccm using another mass flow controller (SEC-E4; HORIBA STEC). The He/O

2 mixture was introduced into an upper electrode. The bottom area of upper electrode is 32 × 52 mm

2. The upper electrode has a slit. Slit size is 1 × 20 mm. The mixture flows out from the slit. Distance between upper electrode and substrate was 0.7 mm, distance between upper and under electrode was 1.7 mm. RF power supply (RP-200-27M; Pearl Kogyo Co. Ltd.) and auto matching box (ZDK-916S-2 and M-05A2VD-27M; Pearl Kogyo Co. Ltd.) were used to generate an atmospheric pressure low-temperature plasma. The RF power was 120 W. Its frequency was 27.12 MHz. Stage, on which under electrode was put, can be movable by an electrical motor. The plasma irradiation time per irradiation was 5 s. Cooling time after irradiation was 15 s. They were one set; it was repeated several times. The substrate after plasma treatment was put in the oven at 120 °C for 5 days [

57,

58]. In this study, this heat treatment process will be called annealing.

2.3. Evaluation of PMMA Film

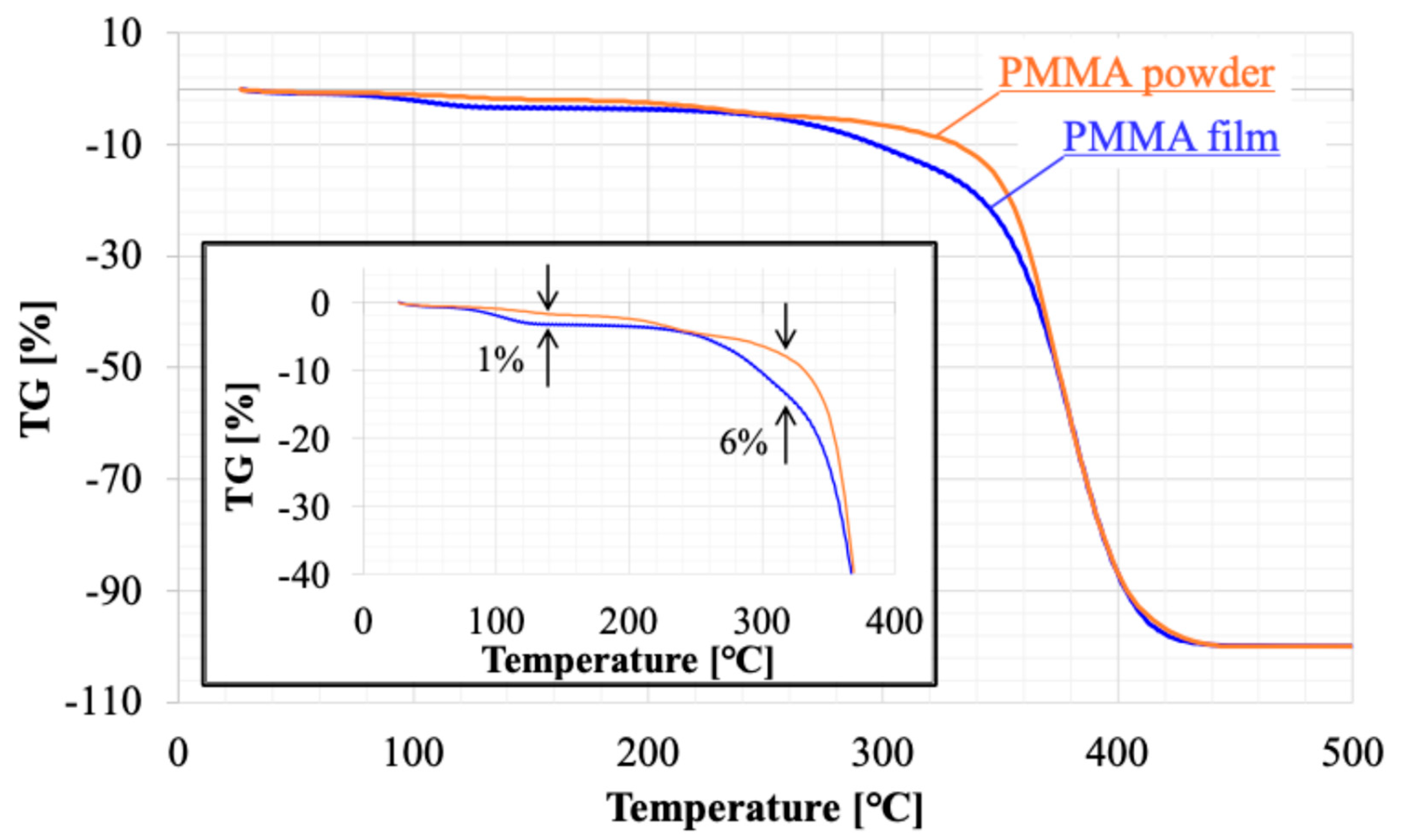

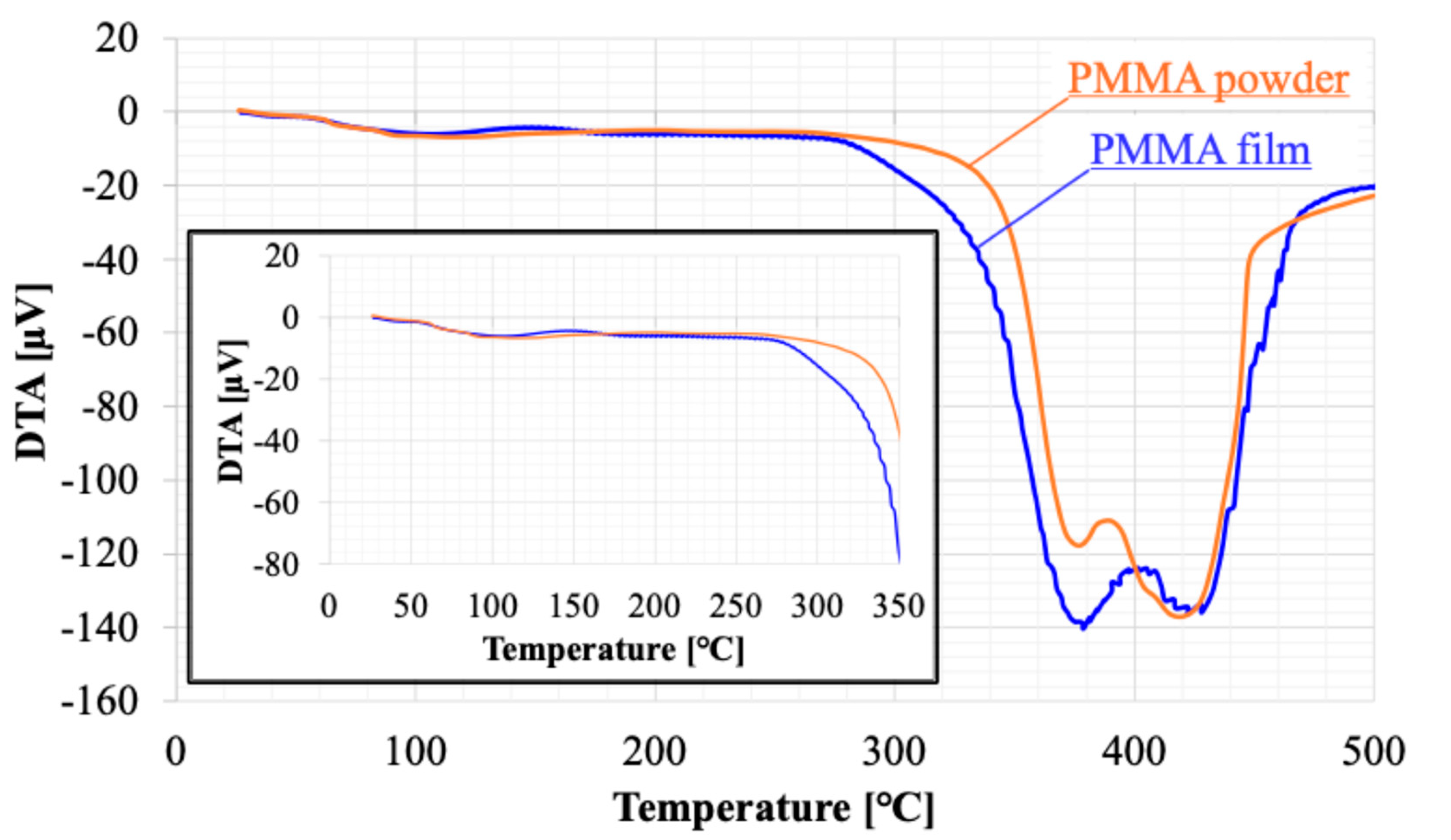

The relationship between the irradiation cycles of APLTP and the film thickness of PMMA was examined. The plasma resistance of PMMA was evaluated by the etching rate, which was calculated from the decrease in film thickness relative to the irradiation time. The amount of residual solvent in the film was examined using TG-DTA (Rigaku, TG 8121 Thermo plus EVO2), which is thermogravimetry (TG) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) . The PMMA film prepared on a glass substrate was scraped off with a scraper. The amount recovered was approximately 5 mg. This was placed in an Al pan and heated from room temperature to 500°C. The heating rate was 20°C/min. Ar gas (≥99.99%; Takamatsu Teisan Co.) was flowed at 150 mL/min. The amount of residual solvent was evaluated from the weight loss at 140-200 °C, which is near the boiling point of ethyl lactate.

The surface profile after irradiation was examined using atomic force microscopy (AFM, Veeco Dimension Icon; Bruker Corp.). The relation of the surface area to the surface roughness to the plasma irradiation condition was evaluated. The evaluation area of AFM was 5 × 5 μm

2 with a resolution of 256× 256 points. The surface roughness was analyzed based on AFM results obtained using WSxM [

59]. Before the analysis, each AFM image was digitally treated with a parabolic flattening, to suppress three-dimensionality and bow effects.

The wettability of the sample surface was evaluated by contact angle (Simage AUTO 100; Excimer Inc.). The water droplet volume was 2 μL. Pure water (specific resistance value > 18 MΩ·cm) was used for the droplets. The contact angle was measured 1 s after contact of the droplet on the surface. The contact angle was calculated by the tangent method.

The antibacterial test was performed to verify the potential of atmospheric pressure low-temperature plasma. The antimicrobial performance of the surface was evaluated according to antimicrobial test ISO 22196 using Escherichia coli (Escherichia NBRC 3972). Polyethylene sheet was used to reference. Untreated PMMA film was used as a control substrate. Initial number of colonies was 3.7 × 105 CFU. Three PMMA substrates were prepared under each condition for the antimicrobial test. Only one APLTP treatment condition was applied in this experiment. The test was carried out by an external agency. The condition of E. coli on the sample surfaces could not be examined because of testing constraints.

3. Results

3.1. Surface Morphology

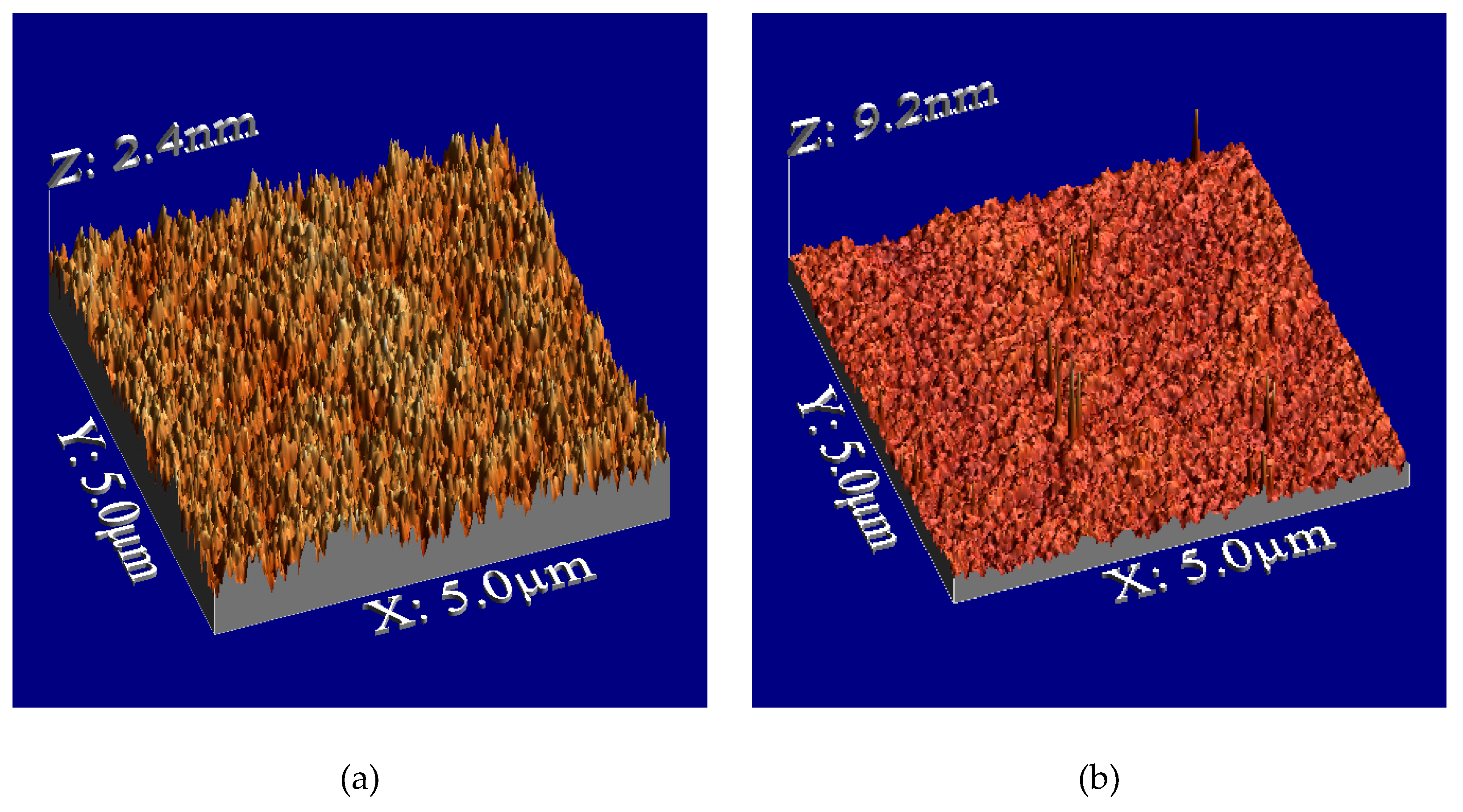

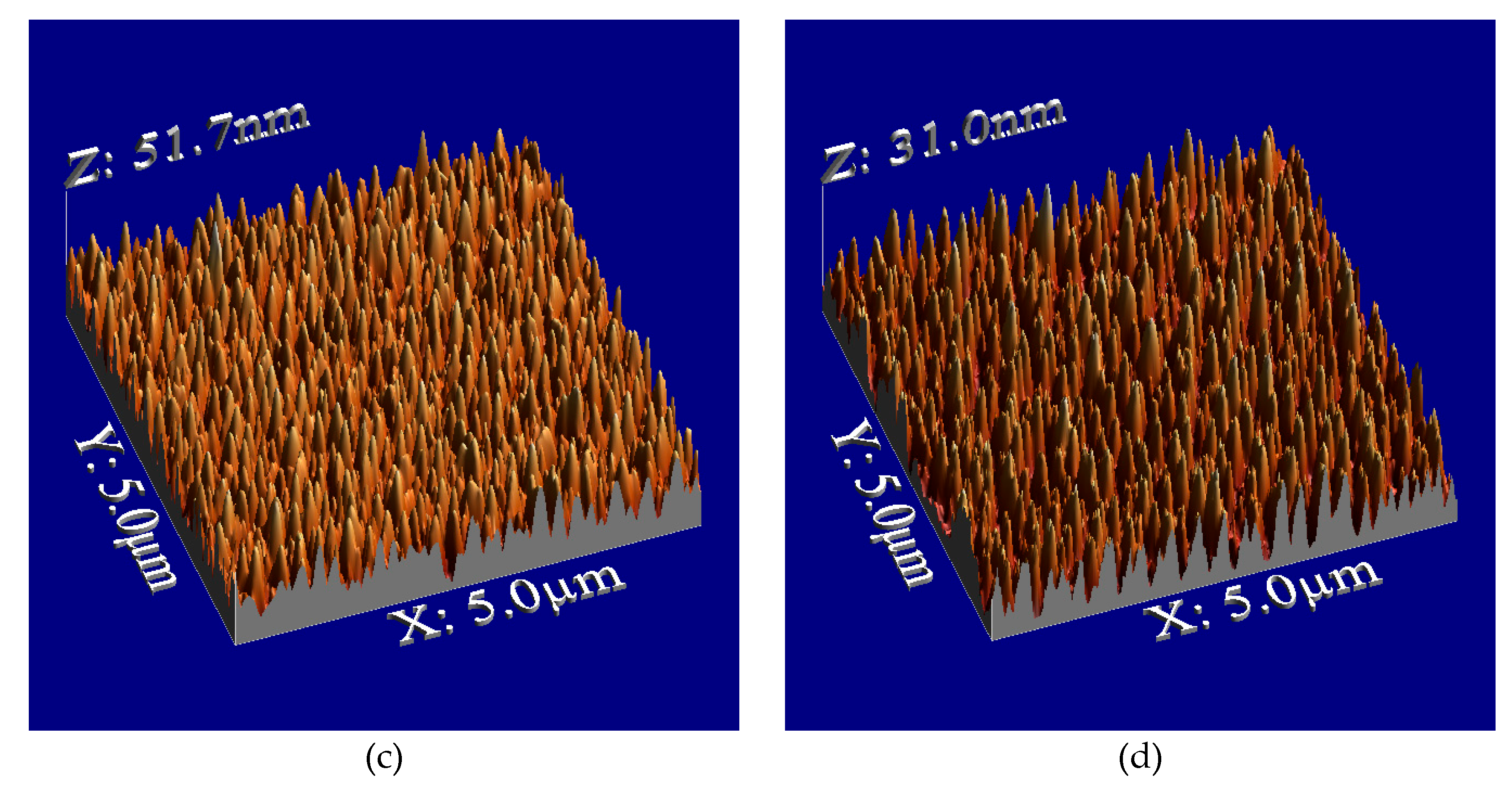

Figure 2 illustrates the surface morphologies, showing sharp-edged nanospikes on the film surface after plasma treatment.

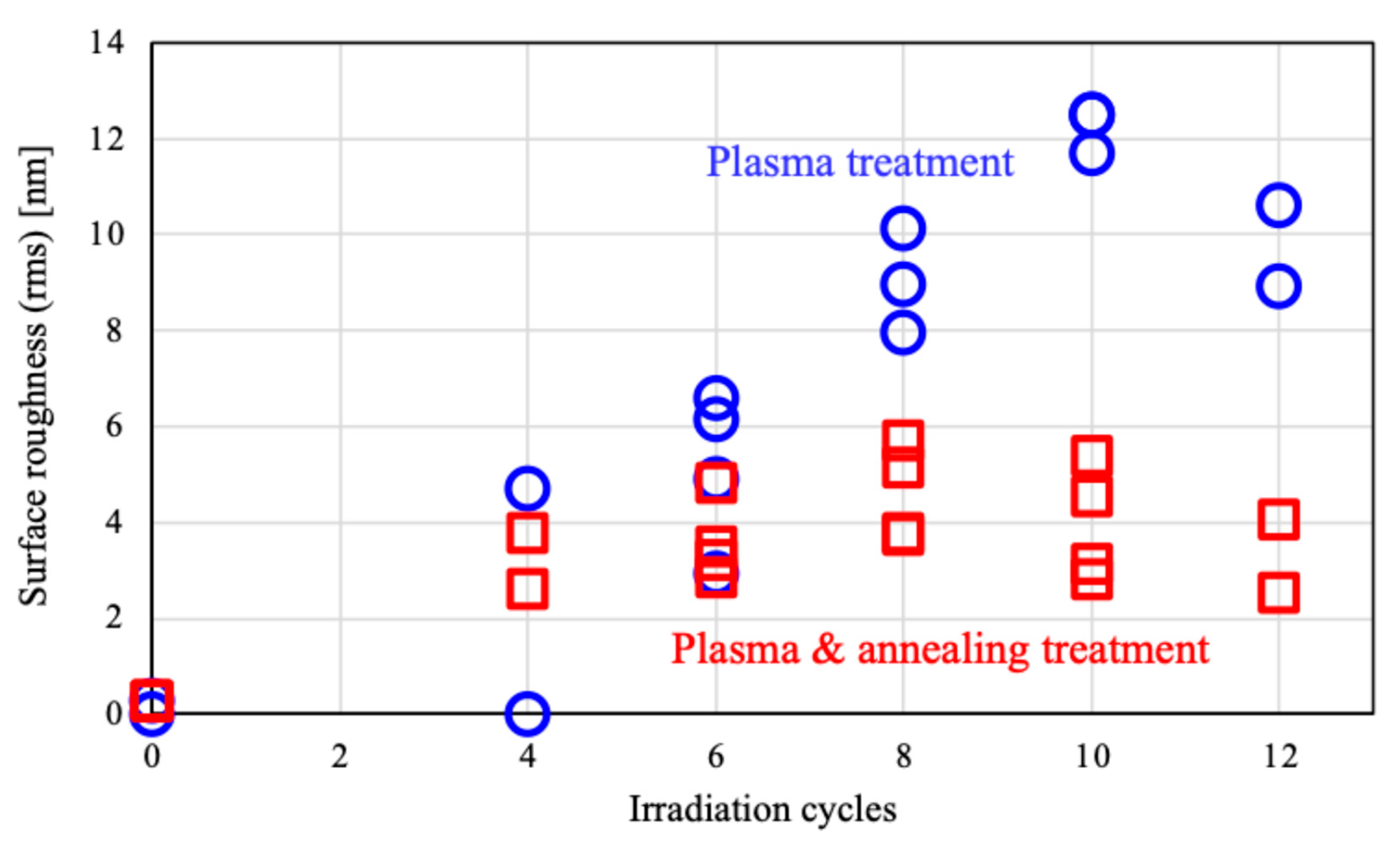

Figure 3 presents the dependence of surface roughness on plasma irradiation cycles for PMMA films. The surface roughness increased up to 10 cycles then after decreasing. Irradiation beyond 10 cycles may lead to the destruction of the microstructures. Annealing after plasma treatment resulted in a decrease in the height of the structures, and the surface roughness reduced to about half of the roughness of plasma-treated surface after irradiation cycles exceeding six. The observed decrease in both the height of the structures and the surface roughness may be attributed to this shrinkage. We will discuss later about thermal shrinking.

3.2. Wettability

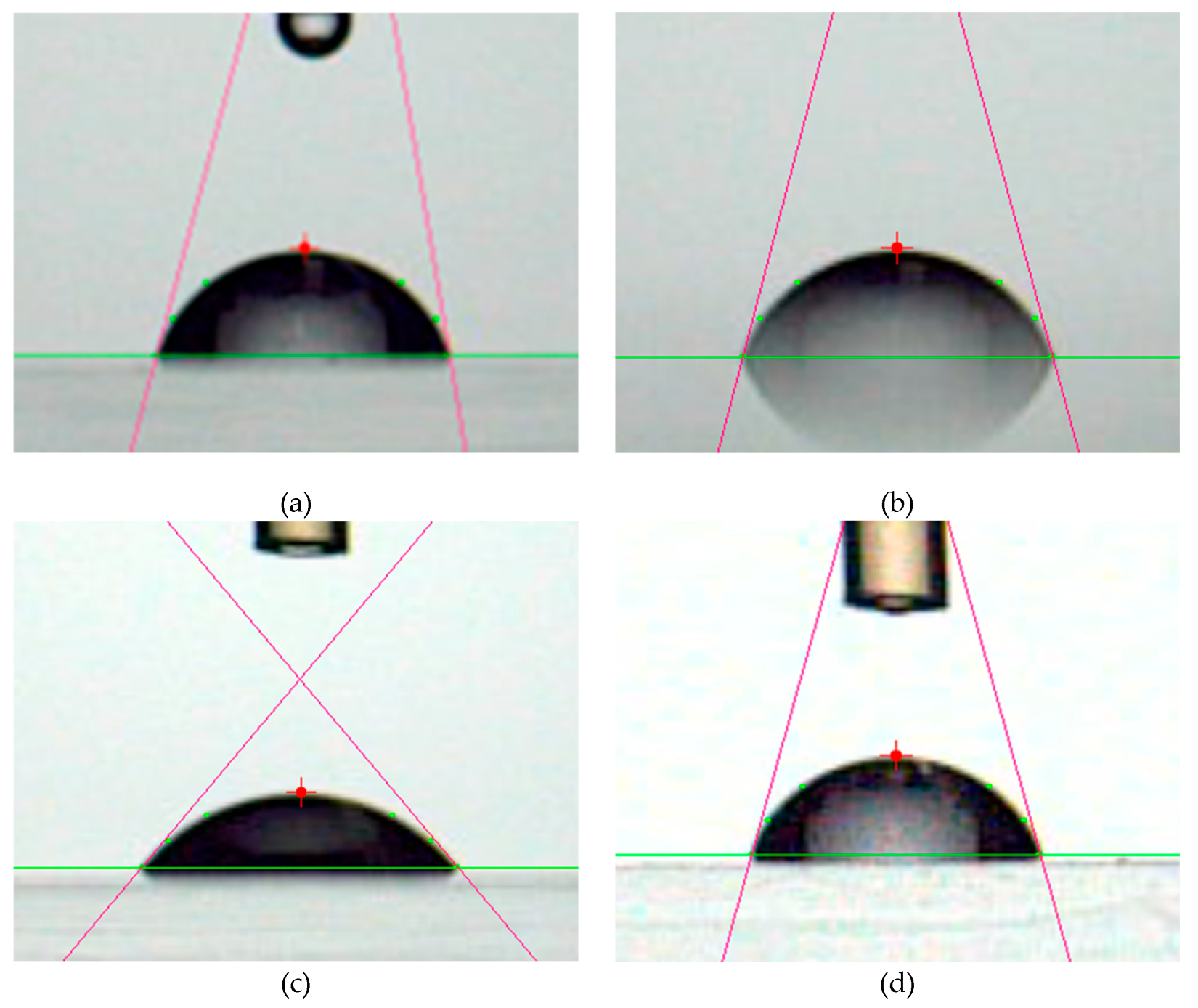

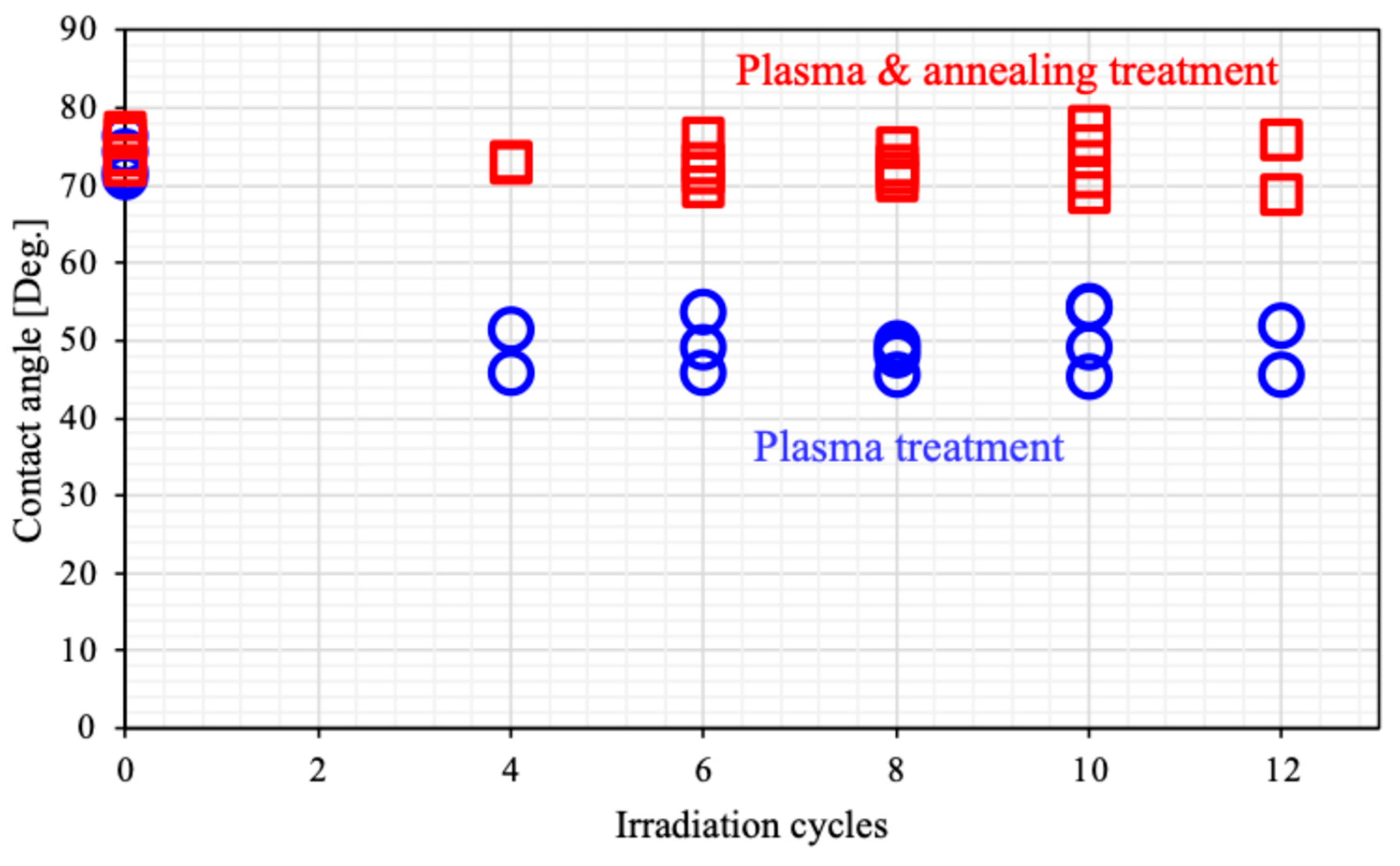

Figure 4 presents photographs of contact angle measurements for PMMA films, while

Figure 5 illustrates the dependence of the contact angle on plasma irradiation cycles. The surface treated only with plasma was hydrophilic. This hydrophilicity was almost independent from surface roughness shown in

Figure 3. Generally, hydrophilicity induced by microstructures is often explained using the Wenzel model [

60]. The increased surface area by the formation of microstructures may be too small to effect wettability. In our previous work, we reported that the formation of microstructures results in

super-nanohydrophilicity, similar to the surface of a snail’s shell [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. In contrast, the wettability of the surface treated with both plasma and annealing recovered to that of the untreated surface. Gotoh et al. have investigated the time course of wettability after plasma treatment and reported that hydrophobicity recovered [

61]. One of our ideas is that annealing may promote this recovery. We will also discuss later about wettability with another idea.

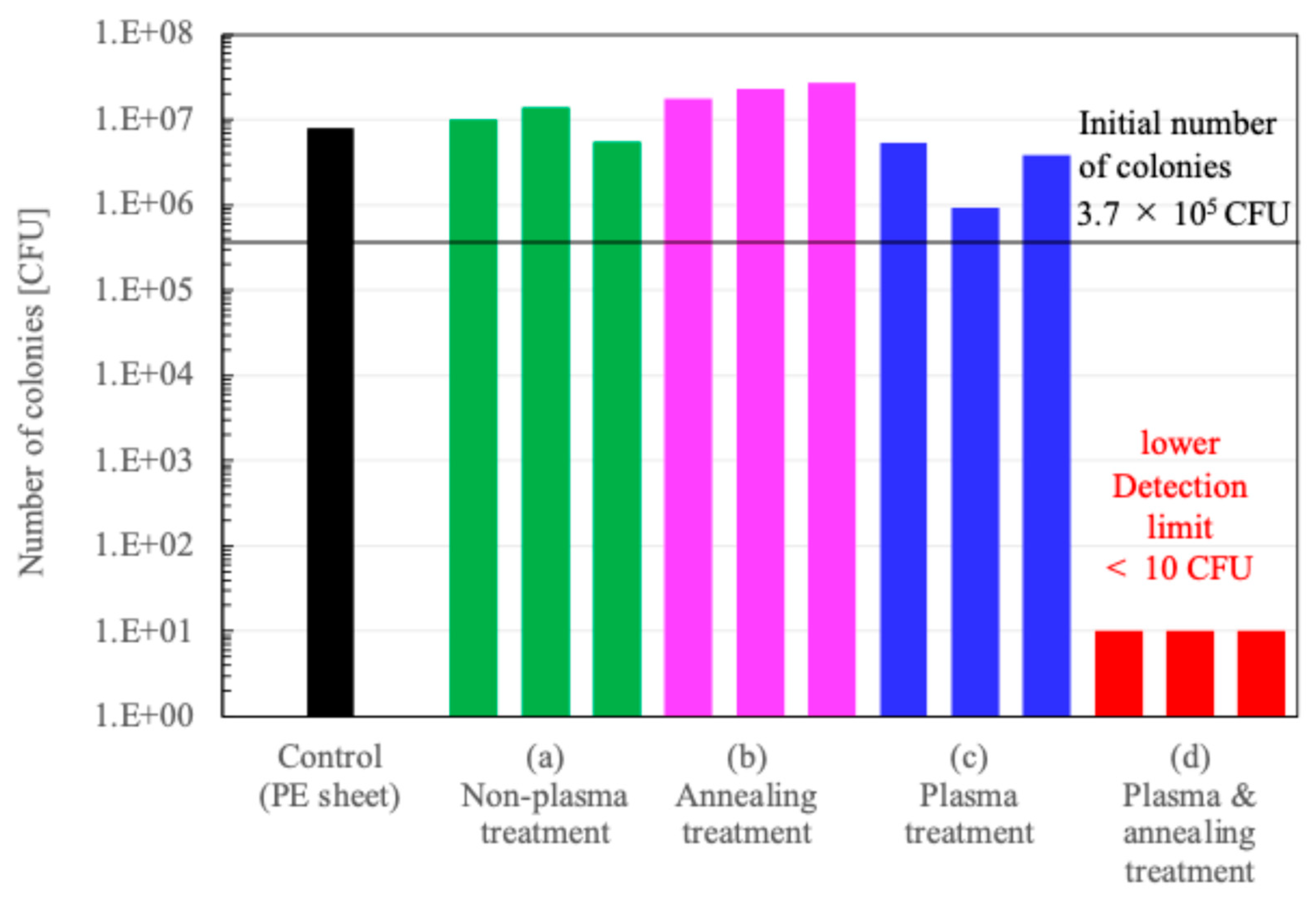

3.3. Antibacterial Test

Figure 6 shows the number of colonies on the surface of PMMA films before and after the treatments. The number of colonies on the untreated substrate was comparable to that on the control sheet, polyethylene (PE) sheet. The number of colonies on the substrate subjected to annealing treatment remained similar to that on the untreated one. In contrast, the number of colonies on the plasma-treated substrate was 30% lower than that on the untreated one. However, on these substrates, the number of colonies increased compared to the initial count. In contrast, the surface treated with both plasma and annealing exhibited a colony count at the detection limit (< 10 CFU). This substrate demonstrated high antimicrobial performance. We will discuss later about antimicrobial performance.

4. Discussion

4.1. Thermal Shrinking

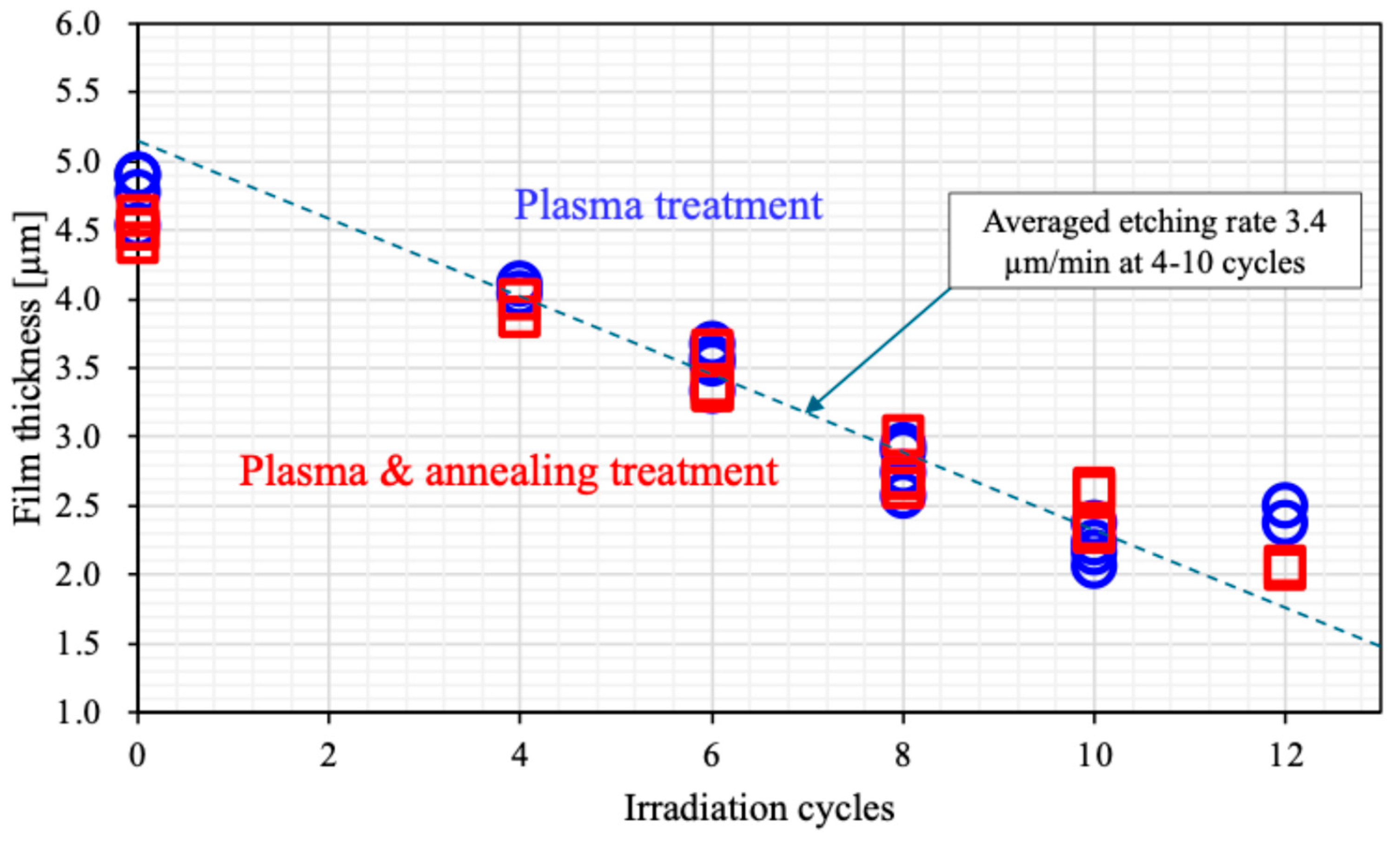

Figure 7 presents the PMMA film thickness on APLTP irradiation cycles for substrates of plasma treatment and plasma & annealing treatment. The initial film thickness is represented by the value at zero irradiation cycles. Prior to annealing, the film thickness ranged from 4.5 to 4.9 µm, whereas after annealing, it slightly decreased to 4.4 to 4.6 µm. This reduction in thickness must be attributed to the shrinkage of the PMMA film caused by the heating during the annealing process. No further decrease in film thickness was observed after four or more irradiation cycles, both before and after annealing, suggesting that the surface side of the PMMA film may be more susceptible to shrinkage. The etching rate, about 3.4 µm/min, was determined for irradiation cycles ranging from 4 to 10, calculated based on the reduction in film thickness relative to the number of irradiation cycles. After 12 irradiation cycles, the observed film thickness deviated from the expected value based on the calculated etching rate. Between 10 and 12 cycles, a decrease in the etching rate was observed, perhaps indicating an increase in the density of the PMMA film at below 2 µm thickness.

The etching rate remained slow for irradiation cycles between 0 and 4, which may be indicative of substances such as moisture and residue on the surface.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 presents the results of thermal analysis (TG-DTA) for raw powder sample of PMMA film and sample recovered from PMMA film. Weight loss was observed starting at approximately 80°C. The DTA results suggested that this weight loss was due to an endothermic reaction. This phenomenon should be consistent across each sample because of the volatilization of adsorbed moisture. The weight loss stabilizes around 140°C, with a total loss of 3%. The weight loss of the film sample was 1% more than that of the powder, suggesting that the film sample had more water adsorption sites. Above 360°C, a sharp weight decrease occurs, which is attributed to the thermal decomposition of PMMA. The temperature at which the weight loss reached -100% was the same for both, 440°C. On the other hand, the weight loss between 260 and 360°C indicates the presence of thermally decomposable substances within the film. DTA shows a large endothermic reaction that partially overlaps with the thermal decomposition of PMMA. Considering that the boiling point of ethyl lactate, the solvent used, is 154°C, the weight decrease observed at that temperatures in the film sample must be ascribed not to solvent remained within the film. This must be made from solvent material during the solvent casting process. It is a kind of solvent residue, and its weight is about 6% of the membrane weight.

4.2. Wettability

The formation of microstructures using plasma etching should be distinguished from so-called surface roughening. Her et al. reported the formation of microstructures on PMMA surfaces using a focused Ga ion beam [

62]. They explain that the formation of microstructures is caused by the penetration of Ga⁺ ions into the bulk of PMMA and these interactions occur not only on the surface but also below the surface. Combining their explanation with our findings [

51,

52], we explain the relationship between the formation of microstructures and wettability. Micropores, which serve as exits for vaporized solvent molecules, may form both on the surface and inside the PMMA film. Dropped water percolates through the microstructures due to capillary action. The pores then provide air paths, allowing the water to fill not only the spaces between the spikes but also the internal pores of the film, leading to a decrease in the contact angle. We call this phenomenon as super-nanohydrophilicity [

51,

53,

54,

55]. In contrast, the wettability of the surface treated with both plasma and annealing recovered to that of the untreated surface. This may be attributed to pore blocking, which is likely caused by the annealing treatment, our another idea. The volume of film shrinkage should correspond to the volume of the blocked pores. As shown in

Figure 7, the volume shrinkage is about 4%. The decrease in film thickness observed in the untreated PMMA film is likely due to the large number of pores on the surface. The volume shrinkage could be caused by pore blocking. As the film thickness decreases with increased plasma irradiation cycles, no further volume shrinkage was observed, suggesting that the pores are confined to the surface side of the PMMA film [

51]. Although water droplets attempt to percolate between the spikes and into the internal pores, the pores are already blocked. Consequently, the trapped air between the water and the spikes prevents further water penetration. This produces the Laplace pressure and is generally seen on hydrophobic surfaces [

63]. These experimental facts can support the validity of our explanation.

4.3. Antimicrobial Performance

The bactericidal effects of both natural and synthetic nanopillars have been thoroughly reviewed by Tripathy et al. [

9]. However, the complete elucidation of the fundamental mechanisms underlying microbial cell death on such surfaces has not yet been achieved. Several mechanisms have been proposed, but the contributions of factors such as wettability and surface roughness to the bactericidal activity of nanostructured surfaces remain subjects of ongoing debate [

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]. Our experimental results support the importance of both microstructure and hydrophobicity because

E coli are gram-negative bacteria that can multiply in water. Under these conditions, it is believed that the surface microstructures contribute to mechanical damage to bacterial cells, resulting in antibacterial activity [

5,

12]. According to them, droplets are partially supported by surface nanostructures and partially suspended over trapped air pockets beneath the liquid. The presence of these air pockets minimizes the effective contact area between the liquid (e.g., a droplet containing bacteria) and the surface, thereby reducing interfacial adhesion. Both wettability and microstructure may be crucial factors contributing to the observed antimicrobial properties. Starting with this work, hereafter, we would like to investigate the antibacterial performance of the surface produced by APLTP against bacteria other than

E. coli.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated the fabrication of cicada wing-inspired microstructures on polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) films using atmospheric-pressure low-temperature plasma (APLTP) without relying on conventional lithographic processes. Plasma treatment successfully generated sharp-edged microstructures, while subsequent annealing modified the surface morphology and wettability by inducing densification and pore closure.

The plasma-treated surfaces exhibited increased hydrophilicity due to enhanced surface roughness and capillary-driven infiltration into micropores. After annealing, the wettability reverted to near-initial levels, likely due to pore blocking associated with thermal shrinkage. Antimicrobial evaluation revealed that while plasma treatment alone moderately reduced bacterial adhesion, the combination of plasma treatment and annealing resulted in bacterial colony counts below the detection limit, indicating highly effective antimicrobial performance.

These findings highlight APLTP as a scalable and versatile approach for engineering functional polymer surfaces with antimicrobial properties, bypassing the material and geometric constraints of lithographic methods. This work contributes to the advancement of biomimetic surface engineering and suggests a promising route for the practical development of antimicrobial coatings for large-area polymeric materials. Further research will focus on understanding the underlying bactericidal mechanisms and optimizing process parameters for specific application demands.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Masashi Yamamoto, Methodology: Masashi Yamamoto, Kentaro Tada, Ayumu Takada, Investigation: Masashi Yamamoto, Kentaro Tada, Ayumu Takada, Data Curation: Masashi Yamamoto, Formal Analysis: Masashi Yamamoto, Writing – Original Draft: Masashi Yamamoto, Writing – Review & Editing: Masashi Yamamoto, Atsushi Sekiguchi, Visualization: Masashi Yamamoto, Supervision: No applicable, Funding Acquisition: Atsushi Sekiguchi, Project Administration: No applicable.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 22K04251.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon request.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ivanova, E.P.; Hasan, J.; Webb, H.K.; Truong, V.K.; Watson, G.S.; Watson, J.A.; Baulin, V.A.; Pogodin, S.; Wang, J.Y.; Tobin, M.J.; Löbbe, C.; Crawford, R.J. Natural bactericidal surfaces: mechanical rupture of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells by cicada wings. Small 2012, 8, 2489–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, E.P.; Nguyen, S.H.; Webb, H.K.; Hasan, J.; Truong, V.K.; Lamb, R.N.; Duan, X.; Tobin, M.J.; Mahon, P.J.; Crawford, R.J. Molecular Organization of the Nanoscale Surface Structures of the Dragonfly Hemianax papuensis Wing Epicuticle. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, E.P.; Hasan, J.; Webb, H.K.; Gervinskas, G.; Juodkazis, S.; Truong, V.K.; Wu, A.H.F.; Lamb, R.N.; Baulin, V.A.; Watson, G.S.; Watson, J.A.; Mainwaring, D.E.; Crawford, R.J. Bactericidal activity of black silicon. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, E.P.; Nguyen, S.H.; Guo, Y.; Baulin, V.A.; Webb, H.K.; Truong, V.K.; Wandiyanto, J.V.; Garvey, C.J.; Mahon, P.J.; Mainwaring, D.E.; Crawford, R.J. Bactericidal activity of self-assembled palmitic and stearic fatty acid crystals on highly ordered pyrolytic graphite. Acta Biomater. 2017, 59, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Kustas, J.; Hoffman, J.B.; Reed, J.H.; Gonsalves, A.E.; Oh, J.; Li, L.; Hong, S.; Jo, K.D.; Dana, C.E.; Miljkovic, N.; Cropek, D.M.; Alleyne, M. Molecular and Topographical Organization: Influence on Cicada Wing Wettability and Bactericidal Properties. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 2000112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogodin, S.; Hasan, J.; Baulin, V.A.; Webb, H.K.; Truong, V.K.; Nguyen, T.H.P.; Boshkovikj, V.; Fluke, C.J.; Watson, G.S.; Watson, J.A.; Crawford, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. Biophysical Model of Bacterial Cell Interactions with Nanopatterned Cicada Wing Surfaces. Biophys. J. 2013, 104, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, J.; Webb, H.K.; Truong, V.K.; Pogodin, S.; Baulin, V.A.; Watson, G.S.; Watson, J.A.; Crawford, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. Selective bactericidal activity of nanopatterned superhydrophobic cicada Psaltoda claripennis wing surfaces. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 9257–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, S.M.; Habimana, O.; Lawler, J.; O’Reilly, B.; Daniels, S.; Casey, E.; Cowley, A. Cicada Wing Surface Topography: An Investigation into the Bactericidal Properties of Nanostructural Features. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 14966–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, A.; Sen, P.; Su, B.; Briscoe, W.H. Natural and bioinspired nanostructured bactericidal surfaces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 248, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandara, D.; Singh, S.; Afara, I.O.; Wolff, A.; Tesfamichael, T.; Ostrikov, K.; Oloyede, A. Bactericidal Effects of Natural Nanotopography of Dragonfly Wing on Escherichia coli. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 6746–6760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassie, A.B.D.; Baxter, S. Wettability of porous surfaces. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1944, 40, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Dana, C.E.; Hong, S.; Román, J.K.; Jo, K.D.; Hong, J.W.; Nguyen, J.; Cropek, D.M.; Alleyne, M.; Miljkovic, N. Exploring the Role of Habitat on the Wettability of Cicada Wings. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 27173–27184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, G.S.; Watson, J.A.; Hu, S.; Brown, C.L.; Cribb, B.W.; Myhra, S. Micro and nanostructures found on insect wings – designs for minimising adhesion and friction. Int. J. Nanomanuf. 2010, 5, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.S.; Myhra, S.; Cribb, B.W.; Watson, J.A. Putative functions and functional efficiency of ordered cuticular nanoarrays on insect wings. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 3352–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.M.; Watson, J.A.; Cribb, B.W.; Watson, G.S. Fouling of nanostructured insect cuticle: adhesion of natural and artificial contaminants. Biofouling 2011, 27, 1125–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linklater, D.P.; Saita, S.; Murata, T.; Yanagishita, T.; Dekiwadia, C.; Crawford, R.J.; Masuda, H.; Kusaka, H.; Ivanova, E.P. Nanopillar Polymer Films as Antibacterial Packaging Materials. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 2578–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zuber, F.; Maniura-Weber, K.; Brugger, J.; Ren, Q. Nanostructured surface topographies have an effect on bactericidal activity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Q.; Wang, X.; Dai, B.; Li, X.; Hao, X.; Ding, Y.; Si, J.; Hou, X. Anisotropic wetting on microstrips surface fabricated by femtosecond laser. Langmuir 2011, 27, 359–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Liu, W.; Su, B.L. Superhydrophobic surfaces: from natural to biomimetic to functional. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 353, 335–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundo, R.D.; Nardulli, M.; Milella, A.; Favia, P.; d’Agostino, R.; Gristina, R. Cell adhesion on nanotextured slippery superhydrophobic substrates. Langmuir 2011, 27, 4914–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.K.; Webb, H.K.; Fadeeva, E.; Chichkov, B.N.; Wu, A.H.F.; Lamb, R.; Wang, J.Y.; Crawford, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. Air-directed attachment of coccoid bacteria to the surface of superhydrophobic lotus-like titanium. Biofouling 2012, 28, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, S.H.; Webb, H.K.; Hasan, J.; Tobin, M.J.; Crawford, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. Dual role of outer epicuticular lipids in determining the wettability of dragonfly wings. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 106, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Xie, G. Precise replication of antireflective nanostructures from biotemplates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 123115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Kasuya, M.; Kawasaki, K.; Washiya, R.; Shimazaki, Y.; Miyauchi, A.; Kurihara, K.; Nakagawa, M. Selection of Diacrylate Monomers for Sub-15 nm Ultraviolet Nanoimprinting by Resonance Shear Measurement. Langmuir 2018, 34, 9366–9375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.; Zou, J.; Zdyrko, B.; Iyer, K.S.; Luzinov, I. Capillary force lithography: the versatility of this facile approach in developing nanoscale applications. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafka, J.; Matschuk, M.; Larsen, N.B.J. Nanopatterning using roll-to-roll thermal nanoimprint lithography. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2013, 23, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Maghsoudi, K.; Jafari, R.; Momen, G.; Farzaneh, M. Micro-nanostructured polymer surfaces using injection molding: A review. Mater. Today Commun. 2017, 13, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.L. Controlled replication of butterfly wings for achieving tunable photonic properties. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, M.L.; Woo, J.H.; Lee, D.I.; Im, H.; Hur, J.; Choi, Y.K. Nature-Replicated Nano-in-Micro Structures for Triboelectric Energy Harvesting. Small 2014, 10, 3887–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zada, W.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Imtiaz, M.; Abbas, W.; Zhang, D. Ror2 signaling regulates Golgi structure and transport through IFT20 for tumor invasiveness. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, F.; Wang, M.; Zhou, D.; Yang, B.; Jiang, B. Fabrication of hierarchical polymer surfaces with superhydrophobicity by injection molding from nature and function-oriented design. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 436, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, F.; Ding, T.; Zhai, Z. Thermodynamic analysis and injection molding of hierarchical superhydrophobic polypropylene surfaces. J. Polym. Eng. 2020, 40, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-K.; Qui, J.-Q.; Fan, S.-K.; Kuo, S.-W.; Ko, F.-H.; Chu, C.-W.; Chang, F.-C. Using colloid lithography to fabricate silicon nanopillar arrays on silicon substrates. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 367, 40–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Du, K.; Wathuthanthri, I.; Choi, C.-H.; Fisher, F.T.; Yang, E.-H. Transfer patterning of large-area graphene nanomesh via holographic lithography and plasma etching. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2014, 32, 06FF01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.; Xie, G.; Liu, Z.; Shao, H. Cicada wings: a stamp from nature for nanoimprint lithography. Small 2006, 2, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, H. Replication of cicada wing's nano-patterns by hot embossing and UV nanoimprinting. Nanotechnology. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 385303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, H.; Gazicki, M. Biomedical applications of plasma polymerization and plasma treatment of polymer surfaces. Biomaterials 1982, 3, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poncin-Epaillard, F.; Chevet, B.; Brosse, J.-C. Plasma-induced surface grafting on polymer films. Eur. Polym. J. 1990, 26, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olde Riekerink, M.B.; Terlingen, J.G.A.; Engbers, G.H.M.; Feijen, J. Selective Etching of Semicrystalline Polymers: CF4 Gas Plasma Treatment of Poly(ethylene). Langmuir 1999, 15, 4847–4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halappa, C.; Park, S.-J. Pattern formation using polystyrene benzaldimine self-assembled monolayer by soft X-ray. Surf. Interface Anal. 2018, 51, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Ke, L.; Deng, J.; Chum, C.C.; Teo, S.L.; Shen, L.; Maier, S.A.; Teng, J. High Aspect Subdiffraction-Limit Photolithography via a Silver Superlens. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 1549–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, V.S.V.; Singh, V.; Kalyani, V.; Parameswaran, P.C.; Sharma, S.; Ghosh, S.; Gonsalves, K.E. A hybrid polymeric material bearing a ferrocene-based pendant organometallic functionality: Synthesis and applications in nanopatterning using EUV lithography. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 59817–59820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xiao, S.; Hu, W.; Hwu, J.; Van De Veerdonk, R.; Wago, K.; Lee, K.; Kuo, D. Integration of nanoimprint lithography with block copolymer directed self-assembly for fabrication of a sub-20 nm template for bit-patterned media. Nanotechnology 2014, 25, 395301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.K.; Cho, H.S.; Jung, H.S.; Lim, K.; Kim, K.B.; Choi, D.G.; Jeong, J.H.; Suh, K.Y. P Effect of surface tension and coefficient of thermal expansion in 30 nm scale nanoimprinting with two flexible polymer molds. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 235303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauss, P.R.; Chou, S.Y. Sub-10 nm imprint lithography and applications. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 1997, 15, 2897–2904. [Google Scholar]

- von Keudell, A.; Corbella, C. Review Article: Unraveling synergistic effects in plasma-surface processes by means of beam experiments. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2017, 35, 050801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, F.; Rider, A.E.; Kumar, S.; Han, Z.J.; Haylock, D.; Ostrikov, K. Emerging Stem Cell Controls: Nanomaterials and Plasma Effects. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013, 329139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Levchenko, I.; Huang, S.Y.; Ostrikov, K. Self-organized vertically aligned single-crystal silicon nanostructures with controlled shape and aspect ratio by reactive plasma etching. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 95, 111505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, D.; Ostrikov, K. Tailoring microplasma nanofabrication: from nanostructures to nanoarchitectures. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2009, 42, 092002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, D.; Bose, A.C.; Ostrikov, K. Atmospheric-microplasma-assisted nanofabrication: metaland metal-oxide nanostructures and nanoarchitectures. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2009, 37, 1027–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Mori, Y.; Kumagai, T.; Sekiguchi, A.; Minami, H.; Horibe, H. Microstructure Formation on Poly (Methyl Methacrylate) Film Using Atmospheric Pressure Low-Temperature Plasma. J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2021, 34, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Takada, A.; Fujii, N.; Sekiguchi, A.; Horibe, H. Formation of Double Roughness Structure on PVDF/PMMA Blended Film Using Atmospheric Pressure Low-Temperature Plasma. J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2024, 37, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Kumagai, T.; Mori, Y.; Minami, H.; Aikawa, M.; Horibe, H. Development of Bile Direct Stent Having Antifouling Properties by Atmospheric Pressure Low-Temperature Plasma. J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2021, 34, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Hamasaki, T.; Sekiguchi, A.; Minami, H.; Aikawa, M.; Horibe, H. Development of Bile Duct Stent with Antifouling Property Using Atmospheric Pressure and Low Temperature Plasma. J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2022, 35, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Aikawa, M.; Yasuda, M.; Hirai, Y. The Development of Bile Duct Stent Having Antifouling Properties by Using Atmosphere Pressure Cold Plasma(2). J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2024, 37, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.H.; Gonsalves, A.E.; Román, J.K.; Oh, J.; Cha, H.; Dana, C.E.; Toc, M.; Hong, S.; Hoffman, J.B.; Andrade, J.E.; Jo, K.D.; Alleyne, M.; Miljkovic, N.; Cropek, D.M. Ultrascalable Multifunctional Nanoengineered Copper and Aluminum for Antiadhesion and Bactericidal Applications. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019, 2, 2726–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horibe, H.; Taniyama, M. Poly(vinylidene fluoride) Crystal Structure of Poly(vinylidene fluoride) and Poly(methyl methacrylate) Blend after Annealing. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, G119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, H.; Kono, A.; Danno, T.; Horibe, H. Crystal Structure Control of Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) in the Blend Films of PVDF and Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) Prepared by Solvent Casting. Kobunshi Ronbunshu 2012, 69, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horcas, I.; Fernández, R.; Gómez-Rodríguez, J.M.; Colchero, J.; Gómez-Herrero, J.; Baro, A.M. WSXM: A software for scanning probe microscopy and a tool for nanotechnology. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2007, 78, 013705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, R.N. Resistance of Solid Surfaces to Wetting by Water. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1936, 28, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yasukawa, A.; Ishigami, Y. Surface modification of PET films by atmospheric pressure plasma exposure with three reactive gas sources. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2012, 290, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Her, K.; Chung, H.S.; Moon, M.W.; Oh, K.H. An angled nano-tunnel fabricated on poly(methyl methacrylate) by a focused ion beam. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 285301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayama, H. Secret of Lotus Leaf: Importance of Double Roughness Structures for Super Water-Repellency. J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2018, 31, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, P.; Shirtcliffe, N.J.; Newton, M.I. Progess in superhydrophobic surface development. Soft Matter 2008, 4, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, D.; Eggers, J.; Indekeu, J.; Meunier, J.; Rolley, E. Wetting and spreading. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 739–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.S.; Zhang, J.; Stafford, J.; Anthony, C.; Gao, N. Implementing Superhydrophobic Surfaces within Various Condensation Environments: A Review. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 8, 2001442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, P.; Farella, I.; D. Matteis, V.; Cascione, M.; Calcagnile, M.; Villani, S.; Vincenti, L.; Alifano, P.; Quaranta, F.; Rinaldi, R. Morphological and mechanical variations in E. coli induced by PMMA nanostructures patterned via electron beam lithography: An atomic force microscopy study. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 56, 105707. [Google Scholar]

- Hawi, S.; Goel, S.; Kumar, V.; Pearce, O.; Ayre, W.N.; Ivanova, E.P. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 1. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, E.P.; Linklater, D.P.; Werner, M.; Baulin, V.A.; Xu, X.; Vrancken, N.; Rubanov, S.; Hanssen, E.; Wandiyanto, J.; Truong, V.K.; Elbourne, A.; Maclaughlin, S.; Juodkazis, S.; Crawford, R.J. The multi-faceted mechano-bactericidal mechanism of nanostructured surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 12598–12605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).