1. Introduction

The accurate prediction of postoperative care requirements following elective surgical procedures plays a central role, both from a medical and an economical perspective [

1]. For instance, if a patient is mistakenly assumed to require only PACU (Post-Anesthesia Care Unit) followed by timely transfer to a general ward, this can lead to last-minute scheduling changes with significant consequences for operating room and intensive care resources [

2], ultimately compromising patient safety [

3,

4,

5]. On the other hand, planning for intensive care resources that are not actually needed can also have negative medical and economic consequences [

6], for example delay of surgeries that by local protocol require postoperate transfer to an ICU. Numerous risk factors and scoring systems have already been described for general [

7,

8,

9] and specific postoperative complications [

10], such as respiratory complications [

11] or acute kidney injury [

12], which may necessitate postoperative admission to a unit with advanced monitoring and therapeutic capabilities. A predictive model titled “SURPAS” [

13] identified several risk factors for the necessity of advanced postoperative monitoring such as the ASA classification, preoperative functional status, and surgical specialty. The machine learning (ML)-based model for predicting ICU admission presented by Chiew et al. demonstrated a specificity of 98%, a sensitivity of 50%, and an AUROC of 0.96. Despite the existence of such models in literature, there are currently no clearly defined recommendations for clinical practice. No standardized guidelines currently exist that call for routine ICU admission based on preoperative variables or planned surgical procedures—neither from surgical, anesthesiological, nor intensive care perspectives [

14,

15]. In practice, the preoperative assessment of the required level of care—whether ICU, Intermediate Care (IMC) [

16], prolonged PACU, or PACU—is still primarily based on internal hospital protocols and the individual judgment of physicians. The absence of widespread adoption of promising data-driven and ML-based approaches can also be attributed to the lack of direct performance comparisons with subjective clinical decision-making [

3]. The aim of this study is to evaluate a real-world dataset to generate robust insights into the performance of subjective physician decision-making, thereby enabling practical recommendations for the integration of modern ML approaches.

The data-driven concept in this work aims to improve the prediction of postoperative care requirements and thus optimize the management of elective surgical procedures.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective analysis was conducted using an anonymized dataset from the University Hospital Augsburg and was previously reviewed by the Ethics Committee of Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (Nr 25-0377-KB).

To classify the postoperative care requirements of elective surgery patients, four levels were defined:

A patient assigned to Level 0 requires standard postoperative care in the recovery room followed by timely transfer to a general ward (= standard care) when transfer criteria are met. This corresponds to the international standard of a PACU. This level was set as the system default.

Level 1 patients are expected to stay in the PACU for an extended period of at least 4 hours, e.g., including overnight monitoring. Level 2 patients are monitored at the IMC during the postoperative phase.

For Level 3 patients, postoperative care in an ICU is assumed to be necessary.

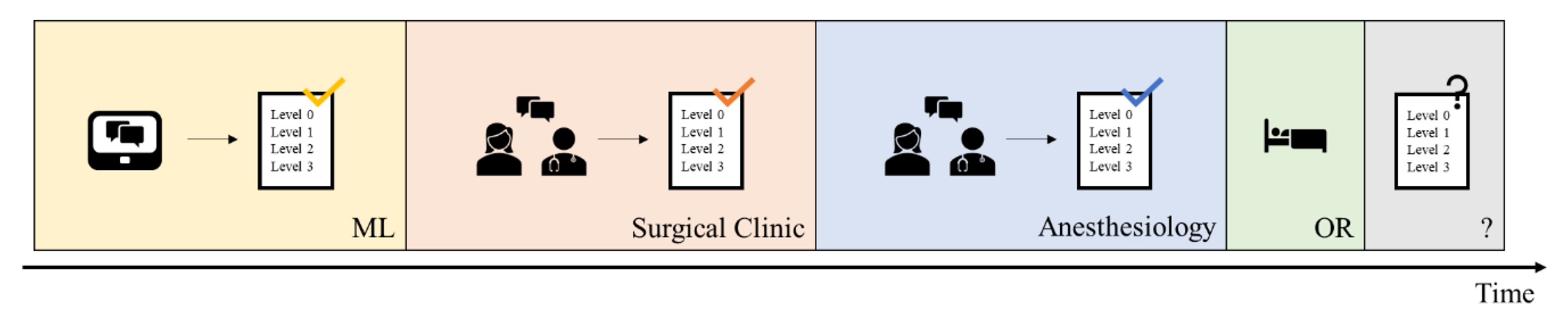

In daily clinical practice at University Hospital Augsburg, the initial prediction of the required postoperative level of care was made by the responsible surgical team during the scheduling of the operation. This was later reassessed during the anesthesiological consultation and preoperative evaluation by anesthesiology physicians (see

Figure 1). Typically, the anesthesiologist was aware of the surgical team’s initial level-of-care prediction prior to making their own assessment.

The performance of the decision-making process was retrospectively evaluated based on a cohort of 35,488 interdisciplinary elective surgical procedures conducted between August 1, 2023, and January 31, 2025. For each case, both the surgical and anesthesiologic preoperative predictions, as well as the actual postoperative level of care provided, were taken into account.

2.1. Statistics

To assess the predictive accuracy of the physicians’ classifications, both disciplines—surgery and anesthesiology—were analysed individually and comparatively. Evaluation metrics included accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, balanced accuracy, and precision. To evaluate the quality of the level-of-care predictions, several performance metrics were employed. Accuracy represents the overall proportion of correctly classified patients across all categories. Sensitivity measures the proportion of true positives correctly identified for each care level, whereas specificity reflects the model’s ability to correctly exclude patients who did not require a particular level of care. Given the imbalanced distribution of care levels in the dataset, balanced accuracy was additionally calculated, as it incorporates both sensitivity and specificity and thus provides a more robust measure. Precision, defined as the proportion of correctly predicted positive cases among all positive predictions, indicates the likelihood that a predicted care level matches the level actually required. This approach allows for a nuanced evaluation of subjective clinical decision-making and its potential alignment—or divergence—from actual postoperative needs.

Cohen’s Kappa was used to quantify the interrater agreement between the two medical assessments, correcting for agreement expected by chance. To test whether the performance of the assessments differed significantly, a Chi-square test was conducted. Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 2024.04.2

www.r-project.org)and Python (version 3.12.11).

3. Results

In the following sections, the performance of the surgical and anesthesiological assessments is analysed separately. This is followed by a comparative evaluation of the predictions made by both disciplines.

3.1. Surgical-Based Predictions

Overall, the surgeons show an accuracy of 91.17%, meaning that in approximately 9% of cases, the surgical assessment did not match the level of care actually provided postoperatively. For 2,008 patients, a postoperative care level higher than Level 0 was predicted. Among patients who ultimately required Level 3 care, 656 (38.05%) were correctly identified preoperatively.

Table 1 compares the surgical prediction with the actual postoperative observation.

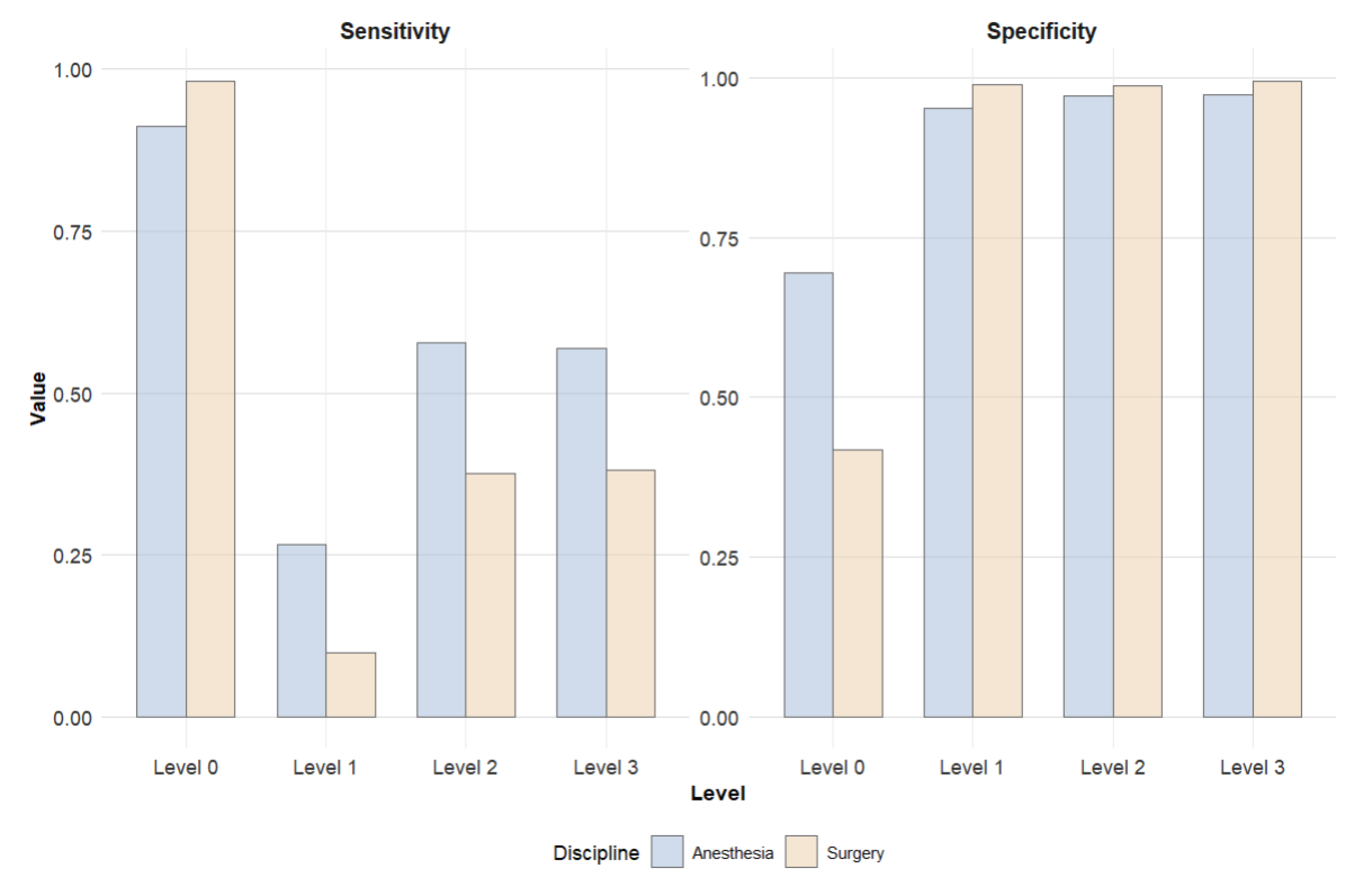

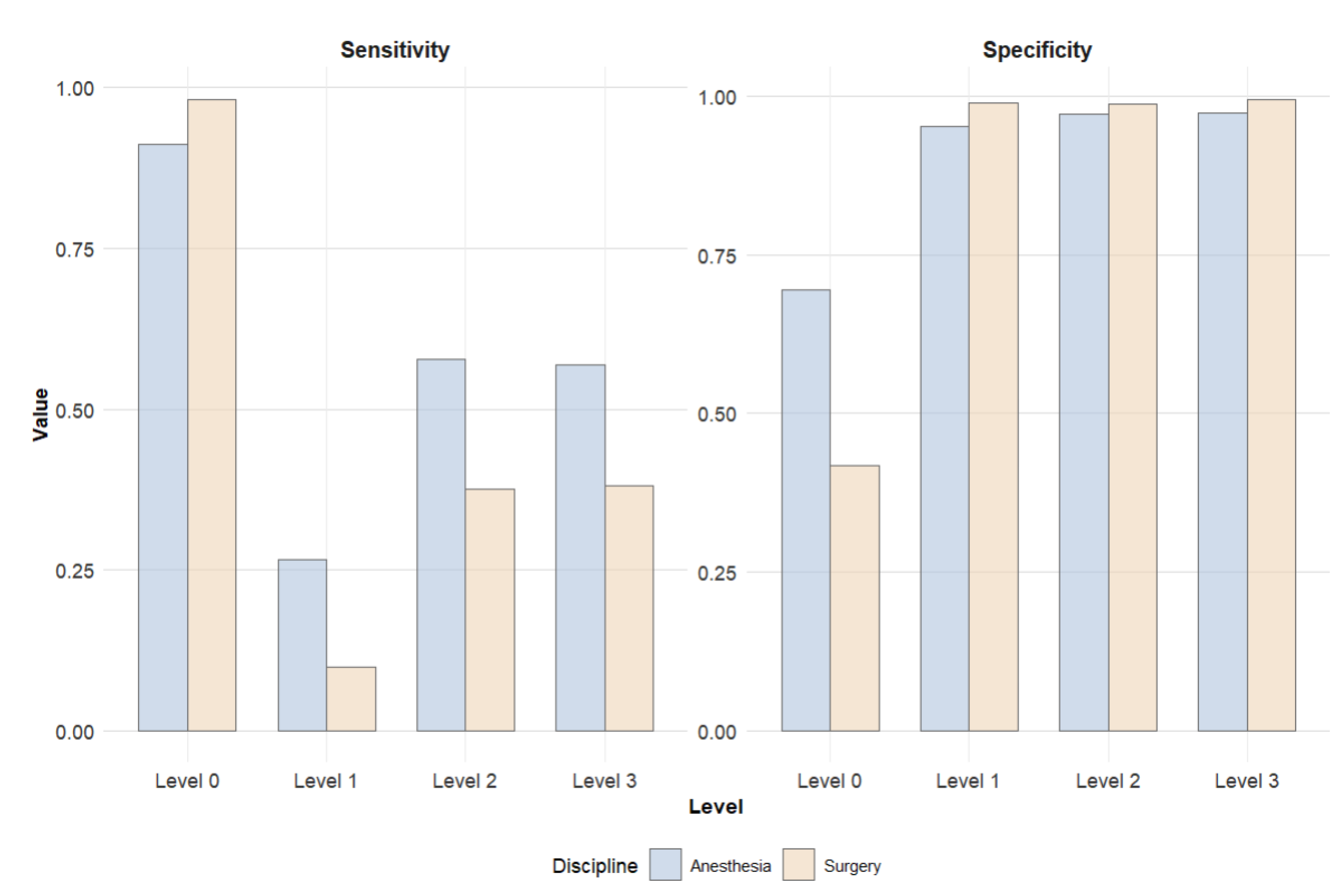

Patients requiring Level 0 care were identified with a sensitivity of 98.21%. The sensitivities for Level 1, Level 2, and Level 3 patients were 9.88%, 37.63%, and 38.05%, respectively. The specificity for the Level 0 group was 41.78%, while specificities for Levels 1 through 3 were 98.95%, 98.80%, and 99.51%, respectively. For patients ultimately requiring Level 3 care, the surgical assessment achieved a balanced accuracy of 68.78%. When a surgeon predicted Level 3 care, this was correct in 79.9% of cases. The precision for Level 0 predictions was 94.03%.

3.2. Anesthesiological-Based Predictions

Overall, the anesthesiologic prediction showed an accuracy of 87.12%, meaning that in approximately 13% of cases, the anesthesiologic assessment did not match the actual postoperative level of care. The overall performance is influenced by the high number of patients requiring only Level 0 care. For 5,227 patients, a higher level of postoperative care than standard care (Level 0) was predicted. Among these, 1,717 (32,85%) cases were overestimated, and 1,049 (20,07%) cases were underestimated in terms of care level. Within the group of patients who ultimately required Level 3 care, 980 (56.84%) were correctly classified.

Table 2 compares the anesthesiologic care level predictions with the levels that were actually realized.

With a sensitivity of 91.14%, the Level 0 patient group demonstrated the highest sensitivity. In contrast, sensitivities for Level 2 and Level 3 patients were 57.84% and 56.84%, respectively, while the identification of Level 1 patients showed the lowest sensitivity at 26.59%. The relatively low specificity for Level 0 (69.46%) indicates that patients are often incorrectly classified as requiring only standard care. Specificity increases for higher levels of care.

The balanced accuracy of the anesthesiological assessment for Level 3 patients was 77.12%, although Level 0 remained the most reliably predicted category. Overall, the positive predictive values for Level 1 through 3 (11.82%, 34.11%, and 52.83%, respectively) indicate limited precision in predicting higher care levels.

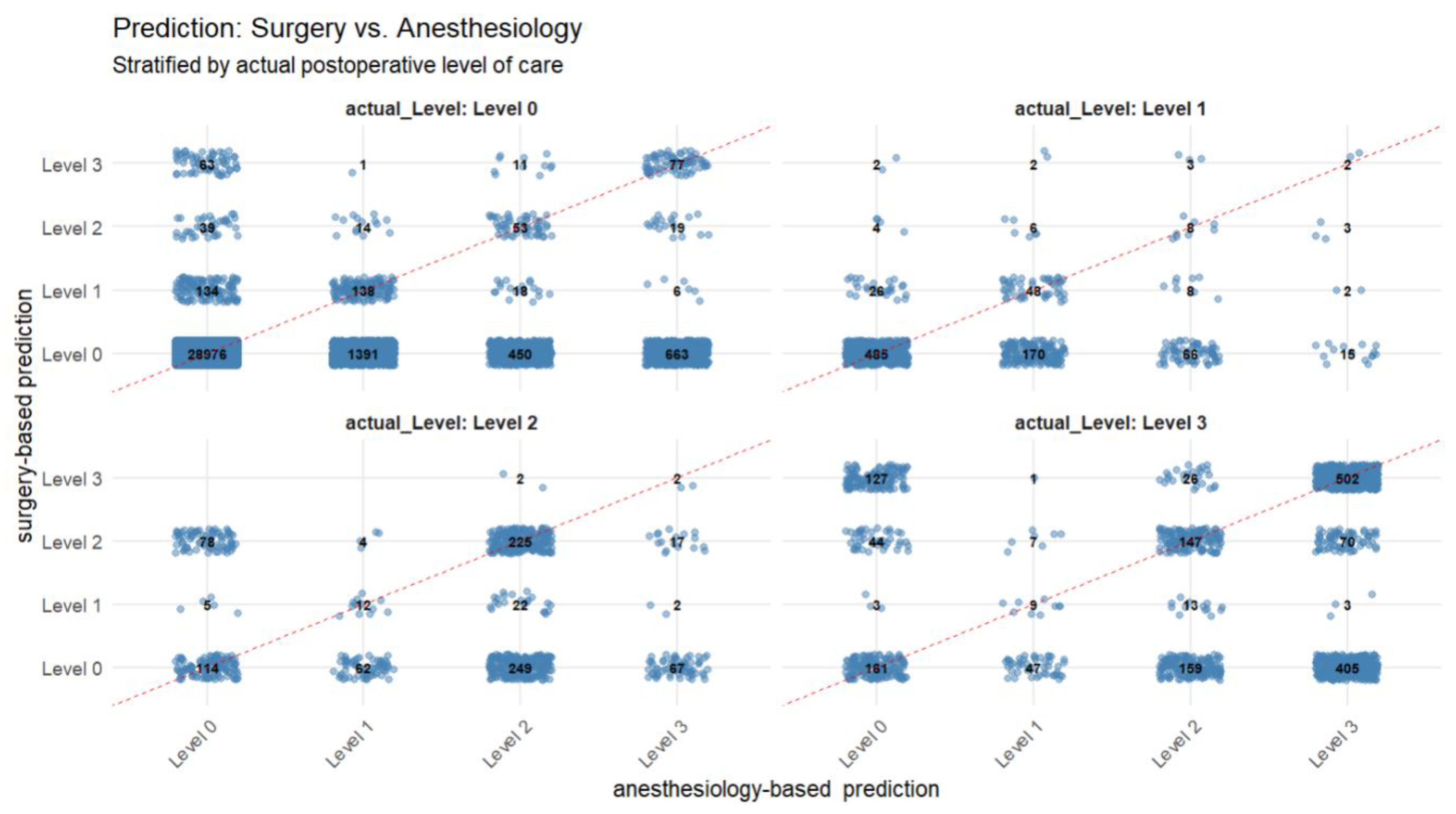

3.3. Comparison of Predictions

A direct comparison between the two disciplines—anesthesiology and surgery—reveals that the surgical assessments demonstrated slightly higher overall accuracy (87.12% vs. 91.17%, χ2 = 2252.32, p < 0.001).

Figure 2 provides detailed information on the different predictions, stratified by the actual postoperative level of care. It Level 0 was the most frequently predicted category—even in cases where the actual postoperative care requirement corresponded to Level 1 through 3. In 28,976 instances, both specialties predicted Level 0 care, which was subsequently confirmed by the observed outcome. However, among these presumed low-risk patients, a relevant number ultimately required a higher level of care (Level 1: n = 485; Level 2: n = 114; Level 3: n = 161), indicating potential underestimation of postoperative needs or the occurence of unexpected intraoperative complications. Discrepancies between surgical and anesthesiologic assessments were also evident. For example, 405 cases were classified as Level 0 by surgery but as Level 3 by anesthesiology, whereas 127 cases showed the inverse outcome. Although the total number of patients jointly predicted to require intensive postoperative care (Level 3) by both disciplines was comparatively low (n = 502), this group showed a high concordance with actual outcomes.

Figure 3 compares the sensitivities and specificities. While surgical clinicians achieved higher sensitivity for Level 0 patients, anesthesiology physicians demonstrated significantly higher sensitivities across all other care levels. The conclusions regarding specificity are vice versa.

Figure 4 presents an aggregated comparison: all levels of care exceeding standard recovery (Level 1–3) were combined and contrasted with PACU (Level 0). This visualization allows for assessment of how well patients requiring enhanced postoperative care were identified. The comparison highlights that anesthesiologic assessments resulted in fewer patients being incorrectly classified as Level 0, thereby ensuring that critical resources were more appropriately utilized. However, this approach also led to a higher proportion of false positive classifications.

4. Discussion

Our study shows that both anesthesiologic and surgical predictions demonstrate a high, though not perfect, concordance with the care that was ultimately provided. In approximately 11% of cases, an incorrect prediction was made. Only about half of the patients who ultimately required postoperative intensive care were correctly identified as such during the preoperative assessment by either the surgical or the anesthesiology team, resulting in a large number of patients requiring an unplanned ICU admission. Since ICUs are commonly required to have a high bed utilization due to economic reasons, multiple unplanned ICU admissions of elective cases can pose major challenges.

As outlined in the introduction, Chiew et al. proposed a ML-algorithm for predicting postoperative ICU admission. The authors highlight the absence of a clinical prognostication benchmark as a key limitation in objectively evaluating the algorithm’s performance [

3]. This analysis provides insights into the quality of preoperative clinical assessments regarding postoperative care requirements from a practical point of view. The results highlight the challenges associated with preoperative assessment of postoperative care requirements in the real world. According to the findings of this study, integrating an appropriate upstream ML-model into the clinical decision-making process would particularly enhance the sensitivity for the most critical patient group - those requiring Level 3 postoperative care.

Using ten preoperative parameters, Chiew et al. trained multiple ML models that demonstrated superior sensitivity and, to a lesser extent, specificity compared to the physician-based predictions reported in the present study [

3]. However, it must be noted that different ML methods yield varying performance metrics. For practical implementation, a nuanced evaluation of the respective models is essential. In the referenced study, the gradient boosting model showed the highest overall performance (AUROC 0.97). Nevertheless, the support vector machine (SVM) model (AUROC 0.94) would be preferable for practical application in this context. Although the SVM model demonstrated slightly lower specificity compared to the gradient boosting model (94% vs. 97%), it outperformed in terms of sensitivity (70% vs. 50%) [

3]. Another key consideration for clinical implementation is that preoperative risk stratification primarily aims to ensure optimal patient care and only secondarily to support resource-efficient planning. Therefore, the presence of false positives should be regarded as an undesirable, yet comparatively acceptable, trade-off in a patient-centered risk evaluation [

6]. While overestimation of care levels may result in inefficient use of limited intensive care resources, underestimation poses potential threats to patient safety [

17]. Taking these requirements into account,

Figure 5 outlines a data-driven concept developed from the findings of this study, aimed at guiding practical implementation in real-world clinical settings. The proposed approach could thus improve overall sensitivity without negatively affecting specificity. In practical terms, this would allow for more accurate preoperative planning of ICU bed allocation—at least for elective procedures. Over the approximately one-year observation period, this concept could lead to a maximum increase of 1,309 correctly predicted ICU admissions.

This study is subject to some limitations: the overall performance of physician-based predictions, particularly accuracy, is influenced by the high proportion of patients classified as Level 0. This effect is further amplified by the system’s default setting to Level 0. Moreover, the training level of the participating physicians was not systematically recorded. Therefore, differences in the proportion of residents, board-certified specialists, and senior physicians across both disciplines may have biased the results. Additionally, the need for a higher level of postoperative observation is influenced by center-specific protocols, where patients undergoing certain procedures are always transferred to an ICU postoperatively, regardless of their assumed risk.

In addition, the reasons for the actual level of postoperative care realized were not available. It remains unclear whether the observed care levels were based solely on medical necessity or also influenced by organizational factors such as limited bed availability in IMC/ICU units. Consequently, no judgment could be made regarding the medical appropriateness of the care allocation observed in this dataset.

Furthermore, current ML models only predict the need for ICU admission - corresponding to Level 3 in our methodology [

3]. Looking ahead, the development and prospective validation of ML models capable of predicting care needs across all levels—including Levels 1 and 2 - would be a desirable advancement.

A key strength of this study lies in the use of a large, real-world dataset comprising over 35,000 elective surgical procedures from a tertiary care center. This allows for robust, practice-oriented insights into current clinical decision-making processes. By incorporating both surgical and anesthesiologic assessments and comparing them to the actual postoperative level of care, the study offers a comprehensive evaluation of current practice patterns. The dual-perspective design adds depth and realism, reflecting interdisciplinary workflows in perioperative planning.

Moreover, the classification system employed - differentiating between four distinct postoperative care levels (PACU, prolonged PACU, IMC, ICU) - closely mirrors commonly applied structures in many European hospitals. Despite the inherent heterogeneity in how observation units are defined and utilized across institutions, the applied model is broadly representative and thus enhances the generalizability of findings.

Finally, the study provides a valuable reference benchmark for evaluating future ML-based prediction models. By quantifying the performance of human clinical judgment, it enables a meaningful comparison and helps guide the development and implementation of data-driven decision support systems.

5. Conclusions

This study offers real-world insights into the preoperative prediction of postoperative care requirements following elective surgical interventions.

Both anesthesiological and surgical assessments demonstrated a high degree of concordance with the actual level of care provided—averaging approximately 89%. The data-driven concept introduced here shows potential to enhance existing clinical decision-making processes. As demonstrated, early findings from the literature indicate that ML–based approaches can provide meaningful support in this context [

3]. Through the present analysis, this potential has, for the first time, been objectively quantified in a real-world clinical setting.

Looking ahead, future interdisciplinary research should prioritize the development of data-driven decision support systems that effectively bridge the interface between human expertise and algorithmic assistance. The goal must be to create actionable, user-centered tools that deliver measurable value for both patients and clinicians in anesthesiology and surgery.

The framework developed in this study represents a promising foundation for such efforts. It illustrates a pragmatic approach to optimizing resource allocation in perioperative care.

The key challenge for future research lies in translating the predictive performance of ML-based models into clinical practice—while navigating the regulatory, ethical, and organizational constraints inherent to healthcare systems.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, Axel Heller, Philipp Simon and Oliver Spring; methodology, Alexander Althammer and Christina Bartenschlager; software, Alexander Althammer; validation, Alexander Althammer and Christina Bartenschlager; formal analysis, Alexander Althammer and Christina Bartenschlager; investigation, Alexander Althammer, Christina Bartenschlager and Felix Berger; resources, Axel Heller, Sergey Shmygalev; data curation, Christina Bartenschlager and Alexander Althammer; writing—original draft preparation, Alexander Althammer; writing—review and editing, Philipp Simon, Felix Girrbach, Felix Berger, Sergey Shmygalev; visualization, Alexander Althammer; supervision, Axel Heller, Philipp Simon; project administration, Axel Heller, Christina Bartenschlager.; funding acquisition, Christina Bartenschlager. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This work was conducted as part of the KISIK project, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). (Funding reference number: 16SV9030).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (Nr 25-0377-KB).

Data Availability Statement

For data access inquiries, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the physicians of the surgical and anesthesiological departments at University Hospital Augsburg for providing the level predictions. During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICU |

Intensive care unit |

| ML |

Machine learning |

| PACU |

Post-Anesthesia Care Unit |

| IMC |

Intermediate Care |

| SVM |

Support vector machine |

| OR |

Operating Room |

References

- van Klei, W.A.; Moons, K.G.M.; Rutten, C.L.G.; Schuurhuis, A.; Knape, J.T.A.; Kalkman, C.J.; et al. The effect of outpatient preoperative evaluation of hospital inpatients on cancellation of surgery and length of hospital stay. Anesth Analg 2002, 94, 644–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turunen, E.; Miettinen, M.; Setälä, L.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K. Financial cost of elective day of surgery cancellations. JHA 2018, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiew, C.J.; Liu, N.; Wong, T.H.; Sim, Y.E.; Abdullah, H.R. Utilizing Machine Learning Methods for Preoperative Prediction of Postsurgical Mortality and Intensive Care Unit Admission. Ann Surg 2020, 272, 1133–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grass, F.; Behm, K.T.; Duchalais, E.; Crippa, J.; Spears, G.M.; Harmsen WS; et al. Impact of delay to surgery on survival in stage I-III colon cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2020, 46, 455–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kompelli, A.R.; Li, H.; Neskey, D.M. Impact of Delay in Treatment Initiation on Overall Survival in Laryngeal Cancers. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019; 160, 651–7.

- Nothofer, S.; Geipel, J.; Aehling, K.; Sommer, B.; Heller, A.R.; Shiban E; et al. Postoperative Surveillance in the Postoperative vs. Intensive Care Unit for Patients Undergoing Elective Supratentorial Brain Tumor Removal: A Retrospective Observational Study. J Clin Med 2025, 14.

- Silva, J.M.; Rocha, H.M.C.; Katayama, H.T.; Dias, L.F.; Paula MBde Andraus LMR; et al. SAPS 3 score as a predictive factor for postoperative referral to intensive care unit. Ann Intensive Care 2016, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moonesinghe, S.R.; Mythen, M.G.; Das, P.; Rowan, K.M.; Grocott, M.P.W. Risk stratification tools for predicting morbidity and mortality in adult patients undergoing major surgery: qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology 2013, 119, 959–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devereaux, P.J.; Bradley, D.; Chan, M.T.V.; Walsh, M.; Villar, J.C.; Polanczyk CA; et al. An international prospective cohort study evaluating major vascular complications among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: the VISION Pilot Study. Open Med 2011, 5, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan, S.; Zbar, A. Risk scoring in perioperative and surgical intensive care patients: a review. Curr Surg 2006, 63, 226–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brueckmann, B.; Villa-Uribe, J.L.; Bateman, B.T.; Grosse-Sundrup, M.; Hess, D.R.; Schlett CL; et al. Development and validation of a score for prediction of postoperative respiratory complications. Anesthesiology 2013, 118, 1276–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheterpal, S.; Tremper, K.K.; Heung, M.; Rosenberg, A.L.; Englesbe, M.; Shanks AM; et al. Development and validation of an acute kidney injury risk index for patients undergoing general surgery: results from a national data set. Anesthesiology 2009, 110, 505–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozeboom, P.D.; Henderson, W.G.; Dyas, A.R.; Bronsert, M.R.; Colborn, K.L.; Lambert-Kerzner A; et al. Development and Validation of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Postoperative Intensive Care Unit Stay in a Broad Surgical Population. JAMA Surg 2022, 157, 344–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cashmore, R.M.J.; Fowler, A.J.; Pearse, R.M. Post-operative intensive care: is it really necessary? Intensive Care Med 2019, 45, 1799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.-M.; Suh, G.Y. Who benefits from postoperative ICU admissions?-more research is needed. J Thorac Dis 2018, 2055–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ch Waydhas, E. Herting, S. Kluge, A. Markewitz, G. Marx, E. Muhl, T. Nicolai, K. Notz, V. Intermediate Care Station Empfehlungen zur Ausstattung und Struktur, 2017.

- Haller, G.; Myles, P.S.; Wolfe, R.; Weeks, A.M.; Stoelwinder, J.; McNeil, J. Validity of unplanned admission to an intensive care unit as a measure of patient safety in surgical patients. Anesthesiology 2005, 103, 1121–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).