1. Introduction

There is much research suggesting that entrepreneurship matters in sustainable economic development, these days perhaps more than ever (e.g. Mahieu et al., 2022; Pricopoaia et al., 2024; Zarkua et al., 2025). Entrepreneurial new ventures, in particular, are considered as drivers of innovation, creators of new industries, agents of growth, substantial sources of employment and potential solutions to both social and environmental concerns (Kayser et al., 2023; Shepherd and Souitaris, 2021). Echoing their importance, there is a conspicuous body of empirical studies examining the causes of post-entry success (or failure) of entrepreneurial start-ups (e.g. Du et al., 2025; Korpysa et al., 2023). However, most scholarly investigations are predominately focused on selective performance drivers; such as the effects of social (Pirolo and Presutti, 2010), financial and entrepreneurial capital (Ruthensteiner and Leitner, 2025), organizational forms and resources (Chrisman et al., 1998), the cognitive and emotional abilities of entrepreneurs (Ruiz-Ortega et al., 2025), the impact of industry (Argaw and Liu, 2024) and local entrepreneurial systems (Tula et al., 2024). Although insightful and useful, these studies seem to be fragmented: the narrow lens of investigating specific determinants limits our understanding of the broader context and make us to lose sight of the ‘bigger picture’ of performance antecedents (Azeem and Khanna, 2023). In other words, it seems that existing literature on strategic entrepreneurship lacks an integrated framework that conceptualizes multifaceted antecedents pertaining to start-ups’ performance. To further explicate, we lose the influences of the strategic ecosystem of entrepreneurial ventures, i.e., the interconnected network of resources, capabilities, decisions and partnerships, on competitiveness and sustained growth. Providing the co-existence of different activities and planning focus, as well as multiple objectives, structures and phenomena within the organizational milieu, we believe that integrated and multidiscipline-based approaches are much needed for theory building and empirical testing in the research of the relationship between strategic management orientations and the sustainability of start-ups’ ecosystem.

The above motivates this research: we draw from resource-based perspectives (Barney, 1991), competency-based views (Colombo and Grilli, 2005), network tenets (Landqvist and Lind, 2019), financial economics (Carpenter and Petersen, 2002) and organization theory in board composition (Johnson et al., 2013) to test the relationships of a wide array of firm determinants with start-ups’ post-entry success. In particular, we draw upon a unique sample of 108 new ventures founded in Greece to investigate the associations of human and strategic capital, partnership-based linkages, funding decisions, and board profiles with market-based performance.

Our research offers three main contributions: First, we propose and empirically validate an integrative, multidisciplinary framework of sustainable entrepreneurship, addressing a critical gap in the extant research. By showing that performance differentials stem from a system of attributes working in concert, we respond to recent, direct calls for a more holistic approach toward the study of the complex and organizationally inseparable nature of new ventures’ performance (e.g. Argaw and Liu, 2024; Aryadita et al., 2023). Second, providing that entrepreneurial new ventures are typically resource-constrained (Herrmann et al., 2022), we inform strategic entrepreneurship and performance studies by identifying the key determinants underpinning their market success. In so doing, we empirically substantiate that the human capital of both founders and employees, innovative business models, adaptive-to-customers strategies, and board heterogeneity impact significantly on the successful practice of nascent entrepreneurship. We conclude that internal factors are more influential in explain performance outcomes than external influences. Finally, in entrepreneurship research, much of the focus has been placed on US Silicon Valley-type contexts and different variants as prime examples of regional entrepreneurial activity (Seet et al., 2021). However, these are relatively unique environments for new ventures when compared to those operating in most other parts of the world. Here, we provide initial evidence of the start-ups’ performance determinants in a EU peripheral economy (Greece); rarely studied in the literature. In Greece, the number of start-ups created per year have risen a record during the last decade, since these ventures were conceived as stopgaps to market and state failures in the business and social landscape (Giotopoulos et al., 2017): our context seems thus also relevant for similar post-crisis environments.

2. Theoretical Underpinnings of the Study and Research Model

Start-ups’ performance is shaped by many firm internal and external factors (e.g. Argaw and Liu, 2024; Azeem and Khanna, 2023; Bao, 2022; Chrisman et al., 1998; McGee et al., 1995; Zott and Amit, 2007). Our conceptualization is anchored at the firm level and control for external influences, allowing us to explore performance precursors mainly rooted within the organizational space.

Human assets: Human capital effects on performance are well recorded; with research highlighting its contribution in multiplying firms’ success prospects (Al Frijat and Elamer, 2025). Human capital theory, originally developed by Becker (1964) and Mincer (1958), indicates that people possess varying extents of intellectual capital, i.e., knowledge, experience and skills that create economic value. To further refine, individuals or groups endowed with higher levels of knowledge stock, expertise, and other competencies tend to achieve greater performance outcomes than those who possess lower levels (Mai and Thai, 2024). In the entrepreneurial new ventures’ research, a human capital perspective has been used to predict a variety of outcomes; such as becoming a nascent entrepreneur, new venture formation, and new venture performance and survival (Dimov, 2017). This research stream concludes that the human assets of the founding teams and/or individual entrepreneurs are determinant for post-entry success and future growth (Baptista et al., 2014; De Winne and Sels, 2010), safeguarding ventures against competitive rivalry (Colombo and Grilli, 2005). This is because they allow for the discovery, creation and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities (Alvarez and Barney, 2007; Marvel, 2013). The knowledge, experience and skills of employees, also assist in the accumulation of new knowledge and the creation of advantages for new firms (Bradley et al., 2012; Corbett et al., 2007).

Human capital assets of both founders and employees can be divided into general, such as knowledge, and specific (or task-related), such as education and experience. These categories are interrelated; for instance, specific human capital assets increase performance and the chances of new venture survival (Criaco et al., 2014), by adding significant experiential knowledge inputs to start-ups. According to Marvel and colleagues (2016, p. 607), the most common human capital assets investigated in scholarly investigations exploring start-ups’ performance antecedents is work experience (39.9% of case) and education (26.6% of cases).

Strategic capital: Mobilizing and combining resources to build new organizations is an undertaking laden with uncertainty and unforeseeable hazards (Foss et al., 2025). Thus, accumulation and re-combinations of idiosyncratic intangible resources and capabilities (Barney, 1991) with the purpose of distilling them into a sustainable competitive advantage lays at the core of start-ups’ strategic foundation. Drawing on these resource-based tenets, Lee and associates (2001) argue for the prominence of resource orchestration by the founding teams in explaining the performance variations of start-ups. The strategic approach of entrepreneurship also advocates the superiority of rationalized planning for better outcomes. Central to this arguement is the notion of proactiveness: by employing a coherent pre-launch strategic analysis, new ventures can gain a-priori insights of possible hindrances they are bound to face in their marketspaces and places, enabling, thus, a more promising pre-entry planning (Shaarani, 2018). Finally, inherent to start-ups’ success trajectory is their ability to deliver innovative products and/or services, that create value. According to Symeonidou and Nicolaou (2018), innovation-oriented ventures are more likely to gain enhanced performance outcomes in the long run, compared to their counterparts scarcely fostering any developments in their offerings. Beyond product and/or service innovation, business modeling is another factor that matters to new ventures. Configuring value proposition with customer needs and behaviors in particular, is a key concern for new entrepreneurs (Guo et al., 2022), since it enables better adjustment to market conditions and unveils novel ways of value creation and capture (Balboni et al., 2019).

Networking: Many studies argue that start-ups play a pivotal role in a large fraction of innovations (e.g. Acs et al., 2014; Audretsch et al., 2020). However, it is not easy for these ventures to successfully innovate, because of their limited business experience and resources. For instance, Stinchcombe (1965), in his seminal work, proposed that the propensity of start-ups to fail exists because they have not established effective relationships with external agents, lacking also a track record with outside buyers and suppliers. To compensate for these deficiencies, collaborative formations with external organizations are considered to be an effective solution (Okamuro et al., 2011). Thus, leveraging partnership-based networking opportunities at founding is a key concern for nascent firms in order to address their liabilities of newness and smallness, and establish connections with their marketplace.

The significance of networking is well admitted in entrepreneurship literature (Arasti et al., 2022), yet its empirical investigation with the performance of new ventures has remained relatively unattended. Network’s contribution consists in, but not limited to, endowing nascent firms with both tangible (i.e., infrastructure, financial capital and stuff) and intangible (i.e., knowledge sharing, intellectual capital and advisory) resources, critical to their survival and growth (Bergek and Norrman, 2008; Lechner et al., 2006).

Business incubators/accelerators have become a ubiquitous phenomenon in many parts of the world and are viewed as an effective tool for promoting the development and growth of entrepreneurial new ventures (Bonfanti et al., 2025). They provide business assistance and compensate efforts of start-ups to assure critical resources and take advantage of their capabilities, enabling thus a more effective handling of their infancy-stage rigors (Lukeš and Zouhar, 2016). As a result, incubated new ventures typically experience enhanced performance in terms of sales revenue and employment growth compared to non-incubated (Lukeš et al., 2018). Establishing links with other firms in the industry, is also typical for firms to exploit networking opportunities. New ventures’ relations with existing firms could pave the way to privileged information, technology transfer, and resources, increasing in that way their survival prospects (Sooampon, 2025). Network ties of entrepreneurial ventures also include partnerships with research centers meant to leverage on knowledge economy to trigger innovation. Academic entrepreneurship could also be the onset of entrepreneurial venturing: probing the relationship between network capabilities and performance of university spin-offs, Walter et al. (2006) conclude that networking is an important determinant of new ventures success.

Funding sources: Adequate financial capital is fundamental for the survival and growth for every single firm. When it comes to new ventures’ formation, ensuring initial funding can stipulate success or failure: this is why funding decisions/alternatives attract considerable interest in entrepreneurial literature (Papamichail and Carayannis, 2025). To a broad extent, relevant research is concerned with deciding an optimal capital structure for nascent firms, since debt and equity hold distinct implications for current performance and future competitiveness (Eckhardt et al., 2006). Faced with the reef of securing their growth, start-ups typically choose between internal and external funding in search of an equilibrium point between current liabilities and future prospects.

Among the funding options available, financial bootstrapping is the most commonly considered by entrepreneurial founders, especially when they encounter financial constraints and their access to financial markets is limited (Van Auken and Neeley, 1996). Bootstrapped firms tap mainly into informal means of financing, such as family, friends and personal finances; attaching in this way greater importance in maintaining proprietorship, rather than exploiting growth opportunities through the attraction of external funding (Archibald and Possani, 2021). Financial bootstrapping provides then a viable alternative to new ventures’ external financing, yet empirical evidence of its relationship with performance produced mixed results (Miao et al., 2017). For instance, while a host of studies hold that a primary cause of new firm failure is the inability to receive adequate external financing (De Blick et al., 2024), Rutherford and colleagues (2012) suggest that bootstrapping is related to increased profitability.

Within the external funding alternatives, bank loans and angel finance appear as compelling methods to fund start-up activity, while venture capital (VC) (both domestic and international) seems to be more an option when strategic thresholds have been met, to attract larger funds (Schwienbacher, 2007). Robb and Robinson (2014) analyze the capital structure decisions of new entrepreneurial ventures, reporting that start-ups rely heavily on external debt in the form of banking loans and credit lines; associating also the higher levels of external debt with start-ups’ faster revenues’ growth. In the same line, Cole and Sokolyk (2018) found that new ventures obtaining bank loans outperform other firms in terms of growth and survival prospects. Angel financing is another, often neglected segment of entrepreneurial finance. Typically, business angels have recorded professional experience in the foundation of a company and have contributed to its development potentials. Thus, they represent a sound reference for new ventures (Lange et al., 2024). The limited evidence on the associations between angel financing and new ventures’ performance points in general towards a positive relationship (e.g. Croce et al., 2018). Finally, extant research delineates an obscure picture of VC finance relative to firm performance, making hard to draw reproducible conclusions (Drover et al., 2017). While for instance Chatterji et al. (2019) found no statistical significant relationship between VC and new ventures’ survival, empirical evidence reported in Croce et al. (2018) suggests that start-ups conjoining angel and VC are more likely to attract larger funds and stand better chances of success.

Organizational factors / board demography: Nowadays, there is a renewed academic interest on the various notions and mechanisms of corporate governance and how these can affect organizations (e.g. Di Vitto and Trottier, 2022; Scherer and Voegtlin, 2020). Past work associating board composition with performance has often examined the educational diversity of board members, age, gender and their ethnicity (e.g. Bamford et al., 2020; Mizruchi and Stearns, 1988). In general, while diversity might result in specific organizational inefficiencies (e.g. Cannella et al., 2008; Li and Hambrick, 2005), there is a broad consensus among scholars that board heterogeneity leads to higher decision quality due to the interaction of multiple perspectives, experiences, and behaviors (Kim and Rasheed, 2014), which, in turn, substantiate in high performance (e.g. Fernández-Temprano and Tejerina-Gaite, 2020). In entrepreneurial start-ups, where board members are normally identical to the members of the founding team, the locus of interest is shifted towards assessing the prevalence of founding team’s demographics in ventures’ success. In this regard, Steffens et al. (2012) assess the impact of key decision-makers homogeneity on start-ups’ performance, concluding that an undiversified team composition in terms of gender and age is less likely to produce substantial financial benefits for the organization. Adding to this, Chen and Lai (2023) posit that new ventures with more diversified boards experience increased performance levels, whereas positive effects are lessened assuming more homogenous board configurations. According to Cheng (2008), start-ups’ board size is negatively associated with performance variations: in larger boards decisions are better scrutinized and are consequently less exposed to bias. As of gender diversity evidence is mixed: a greater female board representation was found non-significant for new ventures’ performance in a bulk of cases, but significant in others (Miller and Del Carmen Triana, 2009). Finally, board stability allows members to develop working relationships and understand each member's perspective, which can enhance organizational efficiencies (Pearce II and Patel, 2018).

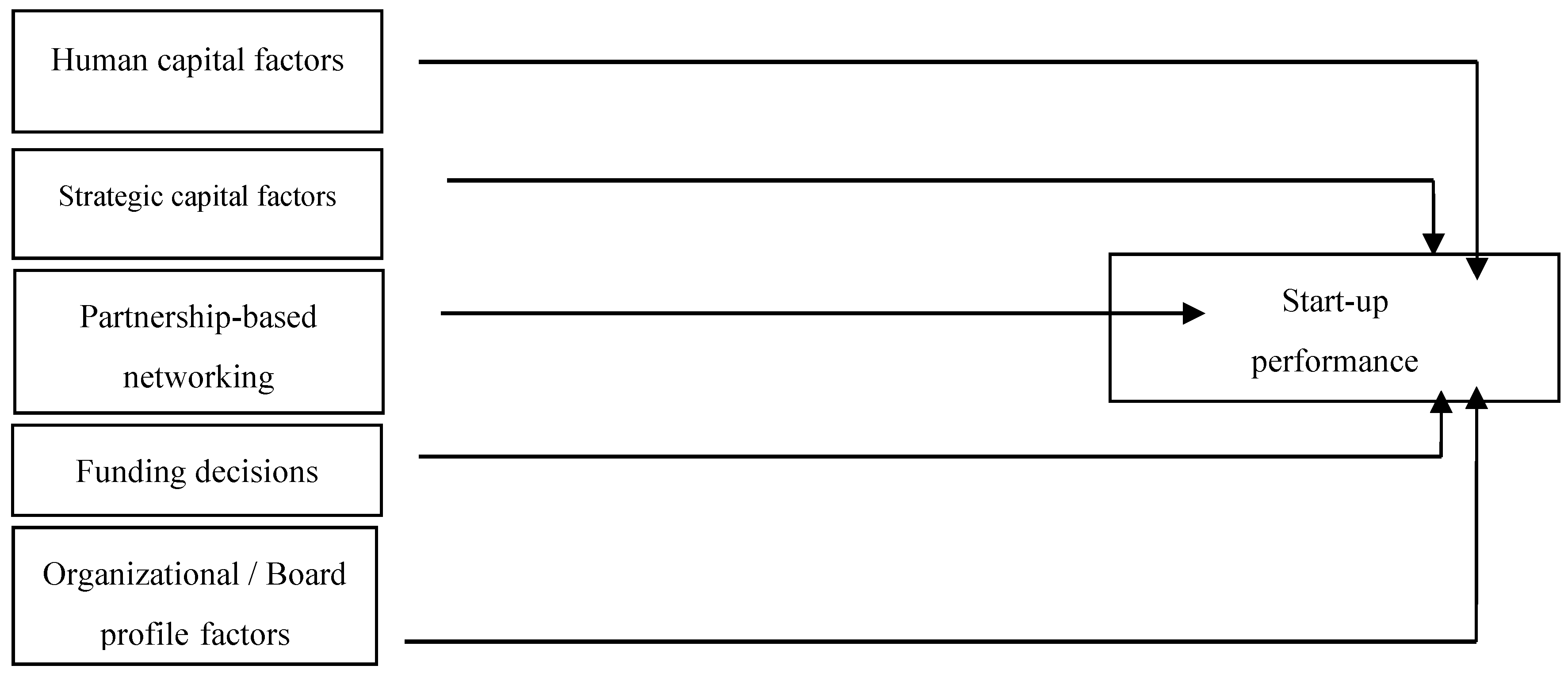

Research model: Based on the above conceptualization and accounting for start-ups’ idiosyncratic characteristics, we postulate that new ventures performance determinants are contingent upon their human and strategic capital, established partnership-based networks at founding, funding decisions and board profiles (

Figure 1).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

We tested our research model on a sample of entrepreneurial start-ups founded in Greece. A study of new ventures in the local context seems appropriate: as said, successful start-ups create and maintain a functional market economy, especially as a means of stimulating competition and job creation (Ali et al., 2020; Kayser et al., 2023; Shepherd and Souitaris, 2021). More importantly, in resource-constrained environments with unstable institutional conditions, besides the positive signs of entrepreneurial activity, employment growth and innovation, a rise in the volume of successful start-ups could also enhance the creation of a healthy and viable overall business ecosystem (Gruber et al., 2013; Park et al., 2002). Since a core purpose underlying the design of our study was to ensure that its results could be generalized (like many other countries, Greece has wide regional and sectoral disparities in its start-up initiatives and ventures’ performance; see for instance Audretsch et al., 2020), our sampling strategy included entrepreneurial new ventures from different marketplaces and diverse marketspaces.

We identify an entrepreneurial start-up as a venture typically in the early stages of its formation. For our sampling purposes, we adopt the established literature in the field (e.g. Dai et al., 2016) and define these firms as companies six years old or younger, offering innovative outputs (products and services), and seeking for a scalable business opportunity under conditions of high turbulence and uncertainty. Further, while nowadays it is increasingly recognized that entrepreneurial activity can emerge in a broad range of organizational arrangements; such as corporate spin-offs (Siegel and Wright, 2014), family firms and social enterprises (Sharir and Lerner, 2006), our study follows Autio and associates (2014) and focuses only on independent start-ups, as the organizational mode that contextualize our research.

Providing the absence of an official, all-encompassing listing of entrepreneurial ventures in the local economy (Manolopoulos et al., 2023), we could not easily draw a reliable single sampling source. Thus, we had triangulated our sample frame: we had recourse to lists from the incubation and acceleration centre of Athens University of Economics and Business (ACEin), the records of the Greek General Secretariat of Research and Technology (GSRT), and the ‘Elevate Greece’ database, the official resource for in-depth information about the Greek startup ecosystem. In our sampling strategy, we only included firms that had been able to commercialize their output / offering; possessing thus a recordable knowledge about the relationships of a wide array of various internal factors and external influences with performance. In total, we have compiled a sampling frame including 616 entrepreneurial new ventures. In making our sample compilation, we obtained the contact information of founders / CEOs through the directories of these associations, as well as through our academic institution professional network and an extensive search on the internet (e.g. the LinkedIn® social network).

3.2. Data Collection

Entrepreneurship research stresses the importance to identify key-respondents when collecting firm-level data that aim at providing evaluations of corporate organizational and strategic issues. Here, our data were collected through the perceptions of start-up founders. The underlying assumption is that these are knowledgeable individuals, and their perceptions reflect the collective perspective of the company. The reliability and validity of founders’ self-reported data of entrepreneurial new ventures has been repeatedly stressed in the literature, where the views of the respondent entrepreneur typically reflect those of the firm (e.g. Glick et al., 1990; Lyon et al., 2000). Consequently, in the absence of hard data, subjective measures provided by founders, are held as reliable sources of information.

We sent our questionnaire following a request to participate in the survey to all 616 firms. In one month following the first mailing, we received completed responses from 28 ventures. We followed the initial mailings with second, third, and fourth rounds of reminders along with questionnaires to non-respondents. The second round of mailings yielded 44, the third 37, while the fourth-round yield 11 responses. Accordingly, we had a total of 120 completed questionnaires. Some of these questionnaires had missing information on key variables. We removed these from the final analysis, resulting in a final sample of 108 completed questionnaires. This represents a response rate of 17.5 per cent, which is considered acceptable in similar survey-based research, and taking also into consideration that our respondents were top executives (Agho, 2009). In the entrepreneurial field in particular, Rutherford and colleagues (2017) recorded that a third of studies have response rates under 25%; suffering, thus, significantly from lower response rates than other areas of management (Baruch and Holtom, 2008).

We formally tested for response bias following the procedure suggested by Oppenheim (1966). This test includes comparing responses received in the early and late rounds. The t-tests revealed no significant difference between early and late respondents. Similarly, we found no significant differences between responding and non-responding firms with respect to corporate characteristics such as size, sector, and years of operation. Among our 108 responding start-ups, a vast majority (70.3%) are located at the capital (Athens), while the remaining 29.7% have been founded in the periphery of the country. Our sample covered six industry sectors: technology and applications (62.9% of sample), healthcare (4.6%), financial services (1.8%), tourism (10.1%), agri-food (14.9%), and light manufacturing (5.7%). Average annual corporate sales ranged from €34.789 to €875.000 (mean 167.015; std. dev. = 141.751), and the average number of corporate employees ranged from 2 to 25 (mean 8.27; std. dev. = 4.71).

3.3. Survey Instrument

Our survey instrument had subjective measures for organizational demographics, the factors accounting for start-ups’ success in their respective marketspace, and some industry / macro controls (market growth rate of the industry, rate of technology obsoletion, quality of the local entrepreneurial system, aggregate R&D spending); and objective measures for firm performance and other firm-level control variables (size, location and sector of activity). The statements developed used attitudinal scaled questions and covered the various characteristics deemed important from the literature in relation with our research objectives (for instance, background details of the start-up; details about the founders’ background and employment history, etc.). To avoid response patterns, some questions were reverse-coded. Our questionnaire was accompanied by a covering letter which aimed to assure participants of full anonymity and confidentiality of individual survey responses. The cover letter served to build trust with the respondents, establish legitimacy, and encourage participation by motivating them to complete and return the survey.

We administered the survey instrument via the Google forms survey tool in both Greek and English language. Web surveys have become increasingly popular in academic research, as manifested in the growing numbers of Web survey methodologies (Callegaro et al., 2015). Overall, internet-based surveys minimize time lags during distribution rounds and usually provide more responses compared to mail surveys (Truell et al., 2002). Following standard academic procedures, the design of our survey instrument was in complete accordance with the ethical guidelines and research policy of our academic institution.

3.4. Variables

Dependent variable: Organizational performance was (Murphy et al., 1996) and continuous to be (Cacciolatti et al., 2020) one of the most commonly studied output variables in entrepreneurial research. In accordance with that, the performance of new ventures serves as our dependent variable. No commonly accepted set of performance criteria or methods by which new ventures should be evaluated exist (Dowling and McGee, 1994). Frequently used performance metrics include sales indicators, employment and asset growth, and profitability indices (McGee et al., 1995). Each variable has its own strengths and weaknesses (Chrisman et al., 1995). Here, we used a market-based performance metric; the volume of start-up net sales (in Euros), as our performance measure. The specific variable was selected, since it has been suggested that revenues derived from sales are often indicative of technical quality, market acceptance, and overall new venture success (Feeser and Willard, 1990). Furthermore, sales are highly correlated with firm ability to leverage efficiency advantages (Murphy et al., 1996). In parallel, widely employed financial performance indicators (such as return on assets, equity and/or investments) seem inappropriate here because in the early stages of a venture’s development these firms typically earn little if any profits, invest heavily, and thus burn capital (Mauer and Ebers, 2006).

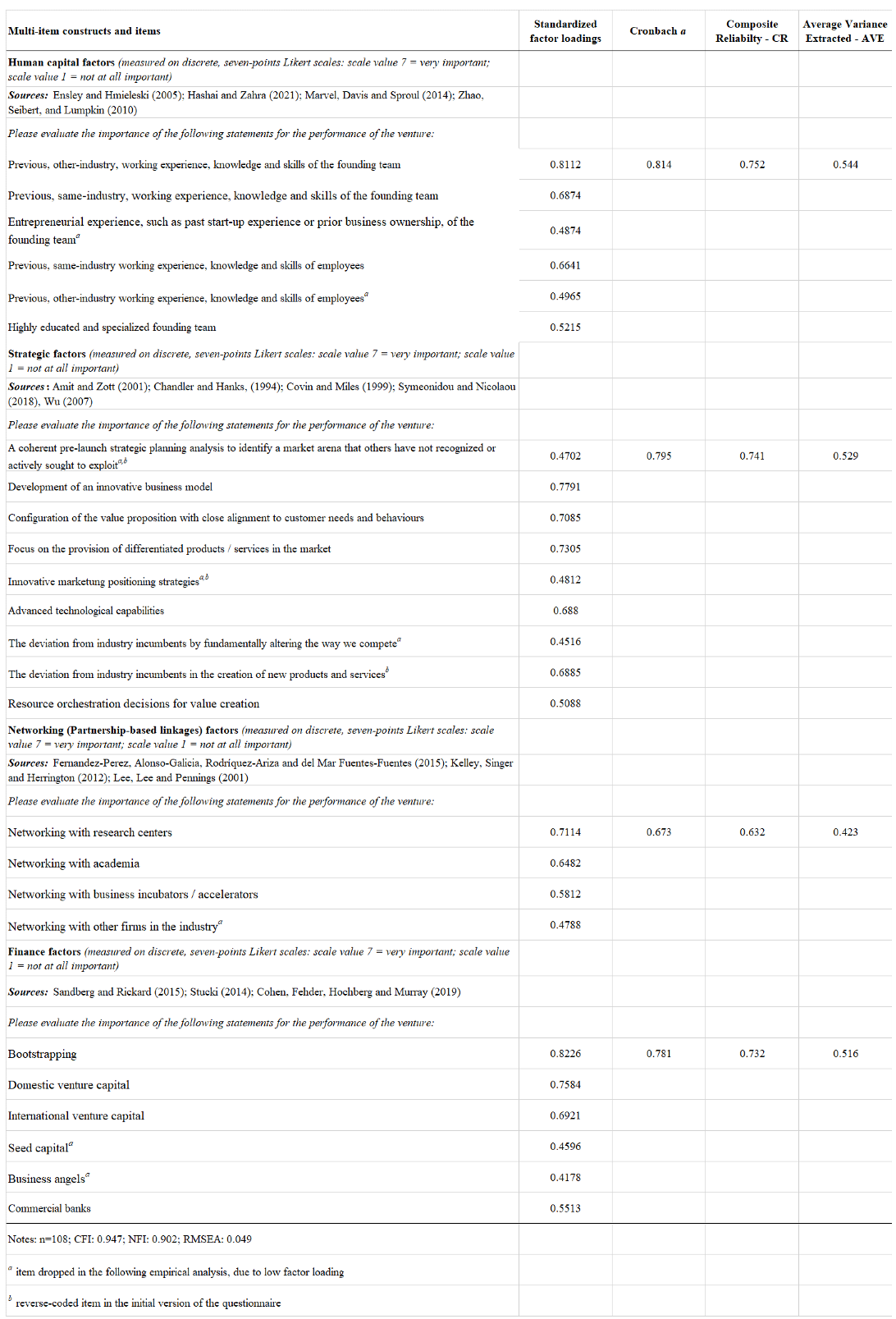

Explanatory variables: Human capital, strategic constructs, partnership-based networks, funding choices and organizational (board profile / demography) factors are the core explanatory variables in our models. Drawing mainly from Hashai and Zahra (2022) and Marvel et al. (2016), we have developed our construct for human capital assets with six items, aiming at capturing the work experience, knowledge and skills of the ventures’ employees and founders. Strategic factors are mainly rooted in Kuratko and Audretsch (2009) work on strategic entrepreneurship, and Symeonidou and Nicolaou (2018) on the importance of resource orchestration in start-ups. These are captured with nine items; trying to frame strategic renewal, sustained regeneration, domain redefinition, business modelling and the importance of firm resources and capabilities on performance. They include start-ups’ business model architecture, resource decisions, dynamic capabilities and elements of strategy decision-making. Networking reflects the expectations, attitudes, and tendencies of start-ups to create and maintain network dynamics. An extended network represents start-ups capabilities in terms of resource acquisition. Partnership-based networks included the liaisons of start-ups with research centers, the academia, incumbents / accelerators and industry at large (four items) (Fernandez-Perez et al., 2015; Kelley et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2001); whereas the finance of the venture included both internal (bootstrapping) and external (venture and seed capital, business angels and bank loan) sources (six items). All our multi-item scales, together with the source of items, are operationalized and reported in

Table 1. Our constructs were captured with seven-point Likert-type questions, where the scale item (7) represented a strong prevalence of the statement, whereas the scale value (1) represented the opposite case. Finally, providing the importance of founding demographics upon the performance of start-ups (Bamford et al., 2020), organizational demography measured the number of founding team members, their educational specialization (a binary variable; where 1 = a degree in entrepreneurial / managerial studies; 0 = a technical / engineering degree), board stability (in months), the number of board meetings per year, and female representation in the start-up board (percentage).

Control variables: To avoid extraneous variation, we have applied a number of industry/macro and firm-level controls that can also influence the performance of new ventures. More specifically, we adopt Baum and Silverman (2004), and control for (i) start-up characteristics (firm size and location), and (ii) industry and macro-environmental effects. We measured firm size in absolute terms, as the total number of the venture’s employees (including both full-time and part-timers). Location was captured with a dummy variable (1 = the start-up is founded at the capital; 0 = the start-up is founded in the periphery of the country). We also controlled for industry effects by the use of a dummy for sector of activity (1 = services, 0 = production / manufacturing). Other market controls were also assessed with seven-point Likert-type scales and included evaluations of the market growth rate of the industry and the rate of technology obsoletion. Finally, the quality of the local entrepreneurial system and gross domestic spending on R&D are macro-environmental factors that may impact on start-ups’ performance (Seo and Lee, 2019) and were also included in our analysis.

3.5. Assessing Validity and Reliability of Measures

Multiple steps were taken to ensure (and test) the validity and reliability of our measures. First, since our research is exploratory in nature, we followed Govindarajan and Kopalle (2006) and have employed a multi-stage process to build our scales for the factors that affect the performance of entrepreneurial start-ups. In order to assess content / face validity, we discussed our scales with two scholars in the innovation / entrepreneurship field and based on their recommendations we reworded the items. Our scales were then pilot tested in two stages: in the first, they were tested with a sample of ten (10) postgraduate students expected to hold in the very near future a degree in entrepreneurship for clarity and relevance. Our scale items were then rephrased based on their feedback. Next, we pilot tested the scales with a set of five (5) start-ups’ employees. In both pilot tests, the respondents read the aim and scope of the research and then responded to the corresponding scale items. While the vast majority of coefficient alphas (75%) for the proposed seven-item scales in both pilot tests were above the cut-off level of 0.70, we further refined the instrument based on professional feedback from two other scholars in the entrepreneurship area. The responses from both pilot tests were not included in our final analyses of reliability and validity.

Further, following Gatignon et al. (2002), we assessed the reliability and validity of our independent constructs, by: (a) determining the coefficient alphas and the average intra- and inter-construct correlations, as an initial reliability diagnostic, and (b) performing confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which mainly tests the validity of our proposed measurement model. The respective coefficient alphas for human capital, strategic, networking, and financial factors are 0.81, 0.79, 0.67, and 0.78 all of which are greater or very close to the recommended 0.70 threshold (Nunnally, 1978). Hence, alpha values suggest a reasonable degree of internal consistency between the corresponding indicators. We further computed the average inter-, and intra-construct correlations based on all the corresponding item-to-item correlations and found the average intra-construct correlations (ranging from 0.28 to 0.46) to be noticeably much higher than the average inter-construct correlations (ranging from 0.21 to 0.33). Notably, all correlations used to compute the average intra-construct correlations were significantly different from zero (p < 0.01), while many of the correlations used to compute the average inter-construct correlations were not. This provides a preliminary assurance of the internal consistency and reliability of our scales, as well as the discriminant validity of our constructs (Govindarajan and Kopalle, 2006).

Next, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to check for structural validity (Hair et al., 1992), using a factor loading > 0.5 to remove the constructs’ weak indicators, and also (i) to test whether the data support the four-factor proposed model, and (ii) assess whether the proposed factor structure is different from alternate solutions (see

Table 1). Most of the standardized factor loadings are greater than the recommended cut-off point of 0.5 (Hair et al., 1995), and the percentage variance explained by these factors are 21.4, 14.8, 9.6, and 12.9 respectively. Moreover, the distribution of standardized residuals was symmetrical around zero and contained no large residuals. The composite reliability (CR) indices range between 0.63 and 0.75. Although the internal consistency is usually measured with Cronbach’s alpha, this criterion is sensitive to the number of items on the scale, thus, the CR becomes an alternate with greater adequacy (Wong, 2016). Finally, the variance extracted by each factor (AVE), range between 0.42 to 0.54.

Various model fit indexes derived from the analysis are shown in the lower portion of

Table 1. While, the χ

2 to degrees-of-freedom ratio is below the suggested cut-off point of 3.0 (Kline, 2004), providing that χ

2 statistic is highly sensitive to sample size (Bagozzi and Foxall, 1996), other more powerful fit indexes such as the comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were computed. Their values met the threshold requirements (CFI and NFI > 0.90; RMSEA < 0.1) suggested by psychometric researchers. Taken together, these results further demonstrate acceptable discriminant and convergent validity of our constructs.

4. Findings and Discussion

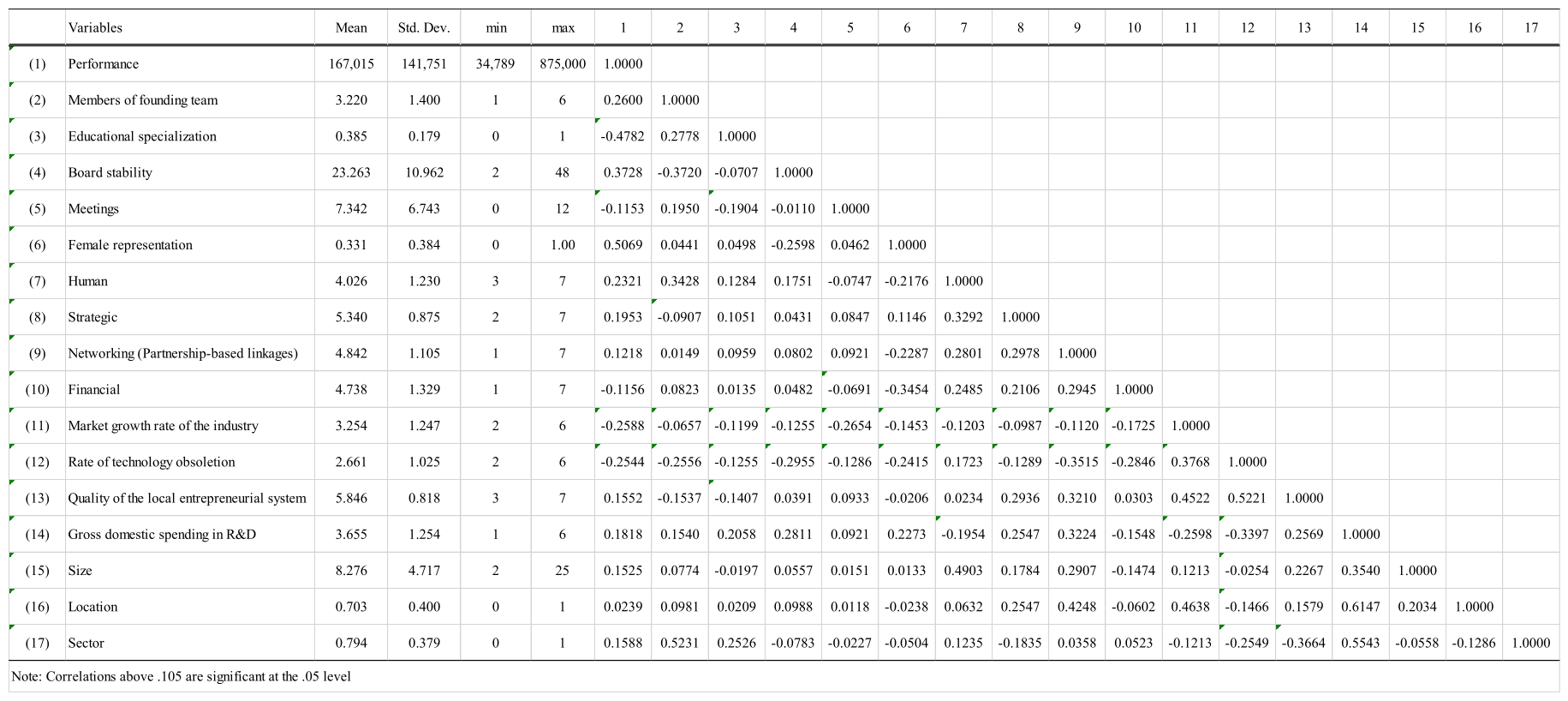

Table 2 reports descriptive statistics and correlations. We can see that the means and standard deviations were reasonable. Such normal dispersal provides an initial legitimization to continue analyzing the data. Correlation coefficients are within the conventional limits. In particular, no correlations are above the 0.65 threshold, suggesting that estimations are not being rendered less precise by multicollinearity (Tabachnick and Fidell, 1996). Further, the values of all variance inflation factors (VIFs) are well below the recommended level of 10 (mean VIF=1.89), which further suggests that the likelihood of multicollinearity is minimal (Kleinbaum et al., 1988). Our performance indicator was significantly related to all our explanatory constructs, showing the strongest correlation with board demographics, and in particular the educational specialization of the founders (

r = -.478, p <0.01), and the extent of female representation in the venture’s decision-making (

r = .506, p <0.01).

Our research focus was to assess a range of firm-internal factors accounting for the success of entrepreneurial start-ups. To test our hypothesized effects, ordinary least squares (OLS) modelling techniques are used throughout. In entrepreneurship literature, OLS regressions are a widely employed empirical strategy to assess the relationships between firm-level contingencies and output indicators, including start-ups’ performance (e.g. Bao, 2022; Lee et al., 2001; Sommer et al., 2009).

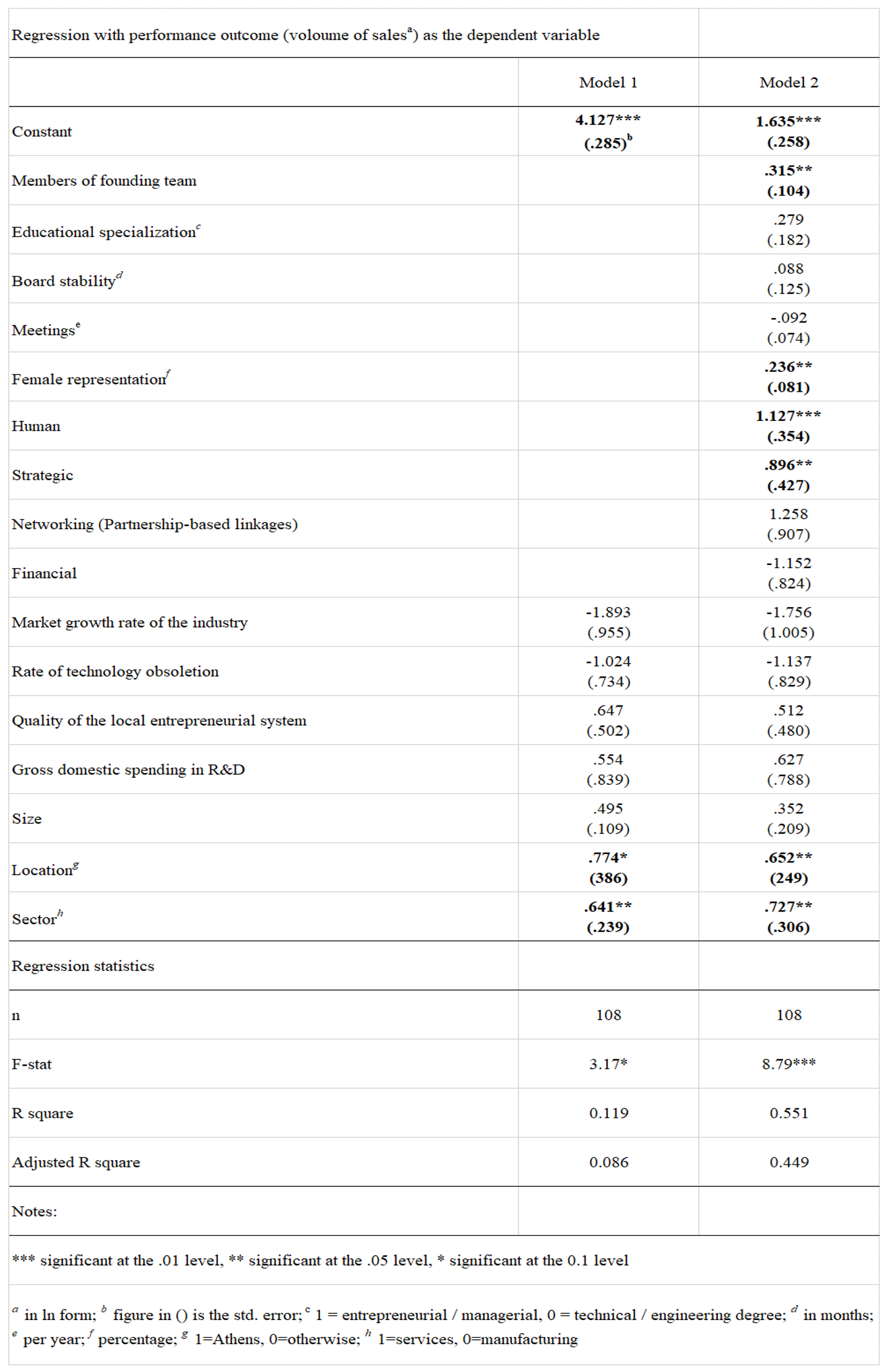

Table 3 presents the results of our empirical specifications.

We first estimated a baseline model (model 1) that reports only the results of our controls on start-ups’ sale volumes. The direct influences of our core explanatory variables are introduced in model 2. We have checked criterion validity by examining R coefficients. In these regressions, R2, the coefficient of determination, represents the proportion of variance in the dependent variable accounted for by the independent variables (Rarnanujam and Venkatraman, 1987). Here, a considerable increase has been reported in our models’ R2 values; from 0.119 to 0.551 (similarly, adjusted R2 values which report the percentage of variation explained by only the independent variables that actually affect the dependent variable shifted from 0.086 to 0.449); suggesting that our understanding of new entrepreneurial ventures’ performance increases considerably when our core independent constructs are included in the analysis.

Among our controls, only location and start-ups’ sector of activity are statistically significant (β = .774 and β = .641; at the 0.10 and 0.05 level of significance, respectively). We provide some explanations for these findings that seem reasonable. By extending economic geography literature (Audretsch, 1998; Krugman, 1991), we suggest that entrepreneurial new ventures are more productive, innovative and, thus, more profitable when clustered within a location that capture the benefits of agglomeration externalities associated with access to a diversified and specialized talent pool and capital sources, close proximity to distinctive market segments, qualitative institutional infrastructure, and a matured localized competition system. To put it otherwise, the concentration of economic activity in specific spaces fulfilling the above characteristics generates positive spillovers for entrepreneurial activity (Audretsch and Feldman, 1996; Delgado et al., 2010). Greece is a country with large and persistent spatial inter-, and intra-regional inequalities (Artelaris, 2022). Whereas an overwhelming portion of economic activity, including employment growth and knowledge creation, is concentrated at the capital, the regional economic development of the country is far less developed. Therefore, in Athens agglomeration effects and knowledge spillovers are evident; arising within clusters related by technology, skills, shared infrastructure, demand and other linkages. Agglomeration economies lower the cost of starting a business, enhance opportunities for innovations and enable better access to a more diverse range of inputs and complementary assets (Saxenian, 1994; Feldman et al., 2005). The co-location of companies, customers, suppliers and other institutions also increases the perception of innovation opportunities while amplifying the pressure to innovate (Porter, 2000). Since entrepreneurs are essential agents of innovation, a strong cluster environment fosters entrepreneurial activity (Delgado et al., 2010). Thus, locating entrepreneurial activity in the capital of the country seems a central element in the puzzle of maximizing start-up sales and performance.

As far as the sector of activity is concerned, evidence reported in

Table 3 suggests that start-ups’ manufacturing / production has little demand in the domestic market compared to the offerings of service industries. According to scholars (e.g. O’Leary-Kelly and Flores, 2002; Salomon and Shaver, 2005), an increase of manufacturing firms’ sale volumes mainly depends upon such factors, as a large amount of capital investment, sophisticated production systems, advanced marketing capabilities and efforts, heavy advertising expenditures and considerable R&D investments. Typically conceived as possessing limited resources, manufacturing start-ups seem to be disadvantageous positioning on these elements compared with incumbents in the industry, which, furthermore, are able to capture scale economies driving down production costs and exploit consumers’ brand loyalty which facilitates them not only to expand, but also retain their customer base. Therefore, manufacturing start-ups face pressures in increasing their sales margins. In an opposite direction, service start-ups have fewer barriers to entry to overcome, little to no startup overhead costs, is easier for them to globalize and offer more diversified revenue models, rendering the expansion of their sales’ volume as a more anticipated scenario. Finally, the relationship between services growth and overall economic growth has become stronger in the past two decades as services’ average contribution to GDP and value added of national developed economies has increased. The economy of Greece has improved its performance; it is plausible to assume that service start-ups sell more compared to their manufacturing counterparts.

Turning our attention to our individual research assumptions, results seem to corroborate the human capital (Agarwal et al., 2016; Dencker et al., 2009) and the strategic (Kuratko and Audretsch, 2009) perspectives of entrepreneurship. The positive, statistically significant relationship between human assets and performance (β = 1.127; significant at the 0.01 level), seems to validate these perspectives recorded in the entrepreneurship literature positing that the knowledge, skills, on-the-job training and experience of enterprising individuals and founding teams provide the foundation for ventures’ growth and survival (Marvel et al., 2016); since they allow for the discovering and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities (Alvarez and Barney, 2007; Marvel, 2013). Within the same lines, imprinting theory (Stinchcombe, 1965) suggests that founders' and employees’ assets (such as their experience and knowledge) are among the most important factors that affect start-ups' performance and future evolution (Simsek et al., 2015; Snihur and Zott, 2020). The importance of the founding team human capital on the performance of their venture offers also empirical support to an argument presented by many entrepreneurship scholars, positing that absent significant experiential knowledge of their own, start-ups typically build on their founders' knowledge, experience and skills, which become the main sources for their knowledge base and performance trajectories (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven, 1990; Felin and Zenger, 2009). Interestingly enough, despite that human and financial capital are both considered as core determinants of start-ups’ success (e.g. Colombo et al., 2004; Cooper et al., 1994), the regression coefficient for finances was insignificant (β = -1.152, p > 0.1). Thus, on the basis of our sample, the finance decisions do not have a direct effect on start-ups’ performance.

The positive, statistically significant relationship between our strategic construct and start-ups’ performance (β =.896; significant at the 0.05 level) highlights the importance for these ventures to effectually conceptualize their business environment, provide a compelling value proposition, and make effective resource allocations. During the early years of their creation, start-ups are typically confronted with uncertainty, a surge for novelty, low market acceptance and high costs (Park, 2005). In this scenario, these ventures typically promote the search for competitive advantages by being involved simultaneously in opportunity-seeking and advantage-seeking behaviors (Ireland et al., 2003); so as to pursue the marketplace promise for innovations (Amit et al., 2000). Throughout this process, it seems that business models and resource combinations may spur the differentiation aspects of new entrepreneurial ventures from industry competitors in ways valued by the market. Our strategy items suggest that the development of an innovative business model that configures the value proposition of start-ups with close alignment to customer needs and behaviors and focus on the provision of differentiated products / services in the market seem to be a determining strategic prerequisite for high-performing entrepreneurial new ventures. This finding accords with Zott and Amit (2007, 2008), positing that novelty-centered designs lead to higher firm performance. In parallel, in line with Simon et al. (2008), a fit between a firm's resource investments and its leveraging strategy seems important for augmenting the value proposition offered to customers. It can then be concluded that the strategic assets of start-ups have positive performance implications. Despite some authors have argued that the strategic choices of start-ups may be influenced by the partnership-based networks they have established, since networks may impact on product / service lines and ways of conducting business (Lee et al., 2001; Littunen, 2000) our regression coefficient for the impact of networking with performance was insignificant (β = 1.258, p > 0.1)

Among our constructs for organizational demography, the number of venture founders and the greater female representation on start-ups’ boards are positively, statistically significant related with performance (β = .315; significant at the 0.05 level and β = .236; significant at the 0.05 level, respectively). The founding team size might have a positive impact on performance because the variety of human capital assets (skills, knowledge and experience) in the decision-making team increases with it (Müller, 2010), leading to better organizational outcomes (De Winne and Sels, 2010). As far female percentage in the participation of the founding team is concerned, advocates of greater female representation on decision boards (e.g. Robinson and Dechant, 1997) posit that if a board comprises heterogeneous decision-makers, diversity leverages performance outcomes and success. Male and female entrepreneurs are significantly different in several cognitive characteristics, personality traits and social skills. Here, we suggest that their co-existence in the ventures’ board has positive impacts on firm performance. This finding may provide partial empirical support to socialist-feminist theory (Wharton, 1991): females have different attitudes and values and, consequently, adopt a different approach to business compared to their male counterparts. Thus, we may conclude that board diversity might, to some extent, explain the performance gaps in start-ups.

Robustness tests and endogeneity: We performed several supplementary analyses to examine the robustness of the findings. A major concern was the possibility of endogeneity, since recent research posit performance as an important contextual variable that may influence our firm-level constructs (e.g. financial structure and network ability). To alleviate this concern, we introduced a time lag between our independent and dependent constructs, having asked our respondents to evaluate the funding choices and networking of their ventures at or very near the point of founding. By measuring these independent variables in year

t-x, and sales’ performance in year

t (i.e., the independent variables are measured in a time-lagged fashion) we can significantly lessen endogeneity issues stemming from simultaneity effects. In addition, the fact that we included important control variables and industry dummies in our analysis can further ease the concern on endogeneity bias (Wang and Berens, 2015). Additional robustness checks have also been conducted to ensure the validity of our findings. First, by adopting Behn’s (2003) recommendation suggesting that an organization’s performance should be evaluated in accordance to the specific objectives set, we have asked new ventures’ founders to report subjectively the degree to which the sales of their ventures have been successfully achieved, by making early and end-year evaluations. This has created an ordered five-point scaled dependent variable. An ordered probit regression was run and results were consistent with those of

Table 3, having though the problem of common method bias. Finally, we performed an additional robustness check by running the same regressions of start-ups’ performance with two sub-samples split based on the mean firm age (ages 1–3 and 4–6). We found similar results across the two samples (albeit inferior in significance).

5. Conclusion and Limitations

There is broad consensus on the significant role that entrepreneurial start-ups play in advancing the static and dynamic efficiency imperatives of a country’s socio-economic context. Yet, these firms are typically associated with high failure rates, exceeding commonly reported industry figures (Gage, 2012). New ventures are especially vulnerable in their post-entry period (Pena, 2002) thus, understanding their performance precursors provide valuable insights into their support needs (Marvel et al., 2019). Our study found that variability in their performance was better “accounted for” when firm-internal factors (knowledge-based inputs and strategies, business models, governing boards) were included in our specifications; external influences seem secondary in significance.

To further detail, our findings suggest that start-ups’ market success can be largely attributed to the magnitude of their human assets and strategic capital. Thus, we extend human capital perspectives on new entrepreneurial ventures; arguing that individuals with higher level of human capital operate more successful start-ups. Specifically, founders' and employees’ experience, knowledge and skills are fundamental ingredients of firm growth, since these assets have a direct positive effect on its market success. The argument that firms run by individuals with greater human capital outperform others is hardly new in the literature. However, our research highlights the synergistic effects of a combination of generic (knowledge and skills) and specific (experience) human capital elements of both founders and employees.

Similarly, strategic capital elements, such as the importance of a high adaptation strategy and business models designed to respond to market conditions, are also associated with new ventures’ market growth. These results complement studies at the intersection of strategy and entrepreneurship (e.g. Ketchen and Craighead, 2020; Short et al., 2010); providing insights for theory extensions. More specifically, while our findings are in line with the arguments of compelling strategy-based perspectives, such as the resource-based view (e.g. Barney, 1991), prior analyses have paid less attention to the effects of these resources as a key source of start-ups’ potential strategic advantage. Here, we extent these arguments to entrepreneurial new ventures by positing that resource decisions guide start-ups to increase their market performance in dynamic market environments. According to Zahra (2021, p. 1842), start-up companies offer a fertile environment where new resource combinations are likely to emerge; therefore, learning how these companies orchestrate successfully their resources can enrich the relevance of strategy theories. In parallel, we reinforce the strategy perspective of business models (e.g. Teece, 2010). A business model articulates the logic that demonstrates how a business creates and delivers value to customers. Here, we record that innovative, customer-oriented business models enhance new ventures’ organizational outcomes. In so doing, we contribute to an ongoing discussion about the relationship between the evolution of dynamic business model elements with start-up’s growth (e.g. Balboni et al., 2019).

Finally, in the organizational context, heterogeneity of skills among the members of the founding team is considered a success factor for nascent entrepreneurship. Decision boards, holding diverse knowledge inputs, cognitive characteristics and personality traits are expected to predict more accurately environmental changes and the appropriateness of actions to take. This finding is in line with a plethora of scholarly investigations (e.g. Roure and Keeley, 1990; Roure and Maidique, 1986) arguing that the diversity of skills among the members of founding teams has been considered one of the factors shaping new venture success. In our case, heterogeneity is reflected in greater female representation in decisions and an extended number or founding members participating in the decision-making. Horwitz and Horwitz (2007) confirm that heterogeneous teams in terms of expertise and experiences result in higher performance than homogeneous teams.

In the empirical forefront, our findings may be of interest to the founders of start-ups and new venture practitioners, in the sense that since these ventures are typically resource-constrained, they may prioritise the relative importance of distinct categories of input elements on their performance levels. New entrepreneurs might value insights from a fully specified model of venture performance that facilitate them to shift priorities as they plan the success of their firm. Also, the strategic impetus of the new entrepreneurial ventures and the positive human assets effects indicate that there are synergistic relationships between human and strategic capital and performance for start-ups. Thus, we point towards the importance of a combined strategy of attracting valuable human resources for achieving superior performance. We also recommend that new ventures should focus on novelty when they design their business models to reap the benefits of service / product differentiations. Finally, since we found a strong case for gender diversity on boards, female representation should be encouraged and promoted. Overall, installing a heterogenous board of directors with more independent board members account for ventures’ better performance

Limitations: Several limitations of the study necessitate caution when interpreting its results, and might provide directions for future research. First, our sample size and the ventures’ location (an EU peripheral economy with chronic structural economic pathogenies) may hinder the generalization of our findings. Another important limitation derives from our output variable: start-ups’ performance was captured with a market-based indicator. Although performance literature suggests that financial ratio indicators are particularly suitable in research on large, well-established firms (Haans, 2019), and may not considered as particularly appropriate here because they could exaggerate relations of interest and confound the interpretation of findings (Wiseman, 2009), we acknowledge that the relationship between start-ups’ internal conditions and their performance should accommodate time-based information and, in this direction, the use of ratio financial indicators could lead to more powerful models. In similar veins, longitudinal, process-focused designs would provide complementary information to our study. Next, stemming from our limited sample size, some variables that might be significant predictors of post-entry start-up performance (e.g. entrepreneurial orientation, initiatives, founders’ personality traits and cognitions) were omitted from the study. Likewise, to keep the survey’s length manageable, some variables related to external influences were measured with less precision than would be possible with a longer questionnaire. Finally, our survey secured responses only from new ventures’ founders; results may suffer from attribution bias and ego-defensive misrepresentations. To limit this risk, we adopt Eisenmann, (2021) and did not ask respondents to rank the factors that had the greatest impact on their start-up’s performance.

References

- Acs, Zoltan J., Erkko Autio, and László Szerb. 2014. “National Systems of Entrepreneurship: Measurement Issues and Policy Implications.” Research Policy 43 (3): 476–94. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, Rajshree, Benjamin A. Campbell, Abril M. Franco, and Martin Ganco. 2016. “What Do I Take with Me? The Mediating Effect of Spin-Out Team Size and Tenure on the Founder–Firm Performance Relationship.” Academy of Management Journal 59 (3): 1060–87. [CrossRef]

- Agho, Augustine O. 2009. “Perspectives of Senior-Level Executives on Effective Followership and Leadership.” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 16 (2): 159–66. [CrossRef]

- Al Frijat, Yousef S., and Ahmed A. Elamer. 2025. “Human Capital Efficiency, Corporate Sustainability, and Performance: Evidence from Emerging Economies.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 32 (2): 1457–72. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., Douglas J. Kelley, and Jonathan Levie. 2020. “Market-Driven Entrepreneurship and Institutions.” Journal of Business Research 113: 117–28. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, Sharon A., and Jay B. Barney. 2007. “Discovery and Creation: Alternative Theories of Entrepreneurial Action.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1 (1): 11–26. [CrossRef]

- Amit, Raphael H., Kelley Brigham, and Gideon D. Markman. 2000. “Entrepreneurial Management as Strategy.” In Entrepreneurship as Strategy: Competing on the Entrepreneurial Edge, edited by G.D. Meyer and K.A. Heppard, 83–100. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Arasti, Mahdi, Negin Garousi Mokhtarzadeh, and Iran Jafarpanah. 2022. “Networking Capability: A Systematic Review of Literature and Future Research Agenda.” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 37 (1): 160–79. [CrossRef]

- Archibald, Timothy W., and Eduardo Possani. 2021. “Investment and Operational Decisions for Start-up Companies: A Game Theory and Markov Decision Process Approach.” Annals of Operations Research 299 (1–2): 317–30. [CrossRef]

- Argaw, Yirgalem Mulu, and Ying Liu. 2024. “The Pathway to Startup Success: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of Critical Factors and the Future Research Agenda in Developed and Emerging Markets.” Systems 12 (12): 541. [CrossRef]

- Artelaris, Panagiotis. 2022. “The Economic Geography of European Union’s Discontent: Lessons from Greece.” European Urban and Regional Studies 29 (4): 479–97. [CrossRef]

- Aryadita, Hendra, Bambang Mulyana Sukoco, and Martin Lyver. 2023. “Founders and the Success of Start-Ups: An Integrative Review.” Cogent Business & Management 10 (3): Article 2284451. [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, David B. 1998. “Agglomeration and the Location of Innovative Activity.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 14: 19–28.

- Audretsch, David B., Alessandra Colombelli, Luca Grilli, Tommaso Minola, and Einar Rasmussen. 2020. “Innovative Start-Ups and Policy Initiatives.” Research Policy 49 (10): 104027. [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, David B., and Maryann P. Feldman. 1996. “R&D Spillovers and the Geography of Innovation and Production.” American Economic Review 86 (3): 630–40.

- Autio, Erkko, Martin Kenney, Patrick Mustar, Donald Siegel, and Mike Wright. 2014. “Entrepreneurial Innovation: The Importance of Context.” Research Policy 43 (7): 1097–1108. [CrossRef]

- Azeem, Muhammad, and Anubhav Khanna. 2023. “A Systematic Literature Review of Startup Survival and Future Research Agenda.” Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship 26 (1): 111–39. [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, Richard P., and Gordon R. Foxall. 1996. “Construct Validation of a Measure of Adaptive Innovative Cognitive Styles in Consumption.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 13: 201–213. [CrossRef]

- Balboni, Barbara, Guido Bortoluzzi, Riccardo Pugliese, and Aldo Tracogna. 2019. “Business Model Evolution, Contextual Ambidexterity and the Growth Performance of High-Tech Start-Ups.” Journal of Business Research 99: 115–24. [CrossRef]

- Bamford, Charles E., Thomas J. Dean, and Patricia P. McDougall. 2000. “An Examination of the Impact of Initial Founding Conditions and Decisions upon the Performance of New Bank Start-Ups.” Journal of Business Venturing 15 (3): 253–77. [CrossRef]

- Bao, Jing. 2022. “Social Safety Nets and New Venture Performance: The Role of Employee Access to Paid Family Leave Benefits.” Strategic Management Journal 43 (12): 2545–76. [CrossRef]

- Baptista, Rui, Murat Karaöz, and José Mendonça. 2014. “The Impact of Human Capital on the Early Success of Necessity versus Opportunity-Based Entrepreneurs.” Small Business Economics 42: 831–47. [CrossRef]

- Barney, Jay. 1991. “Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage.” Journal of Management 17 (1): 99–120. [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Yehuda, and Brooks C. Holtom. 2008. “Survey Response Rate Levels and Trends in Organizational Research.” Human Relations 61: 1139–60. [CrossRef]

- Baum, Joel A., and Brian S. Silverman. 2004. “Picking Winners or Building Them? Alliance, Intellectual, and Human Capital as Selection Criteria in Venture Financing and Performance of Biotechnology Startups.” Journal of Business Venturing 19 (3): 411–36. [CrossRef]

- Becker, Gary S. 1964. Human Capital. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Behn, Robert D. 2003. “Why Measure Performance? Different Purposes Require Different Measures.” Public Administration Review 63 (5): 586–606. [CrossRef]

- Bergek, Anna N., and Claes Norrman. 2008. “Incubator Best Practice: A Framework.” Technovation 28 (1–2): 20–28. [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, Alessio, Giulio Mion, Veronica Vigolo, and Valentina De Crescenzo. 2025. “Business Incubators as a Driver of Sustainable Entrepreneurship Development: Evidence from the Italian Experience.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 31 (6): 1430–54. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, Steven W., Jeffery S. McMullen, Kendall Artz, and Esther M. Simiyu. 2012. “Capital Is Not Enough: Innovation in Developing Economies.” Journal of Management Studies 49 (4): 684–717. [CrossRef]

- Cacciolatti, Luca, Ainurul Rosli, José L. Ruiz-Alba, and Jianchang Chang. 2020. “Strategic Alliances and Firm Performance in Startups with a Social Mission.” Journal of Business Research 106: 106–17. [CrossRef]

- Callegaro, Mario, Katja Lozar Manfreda, and Vasja Vehovar. 2015. Web Survey Methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cannella, Alfred A. Jr., Jong Hyun Park, and Hyeon U. Lee. 2008. “Top Management Team Functional Background Diversity and Firm Performance: Examining the Roles of Team Member Colocation and Environmental Uncertainty.” Academy of Management Journal 51 (4): 768–84. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, Robert E., and Bruce C. Petersen. 2002. “Capital Market Imperfections, High-Tech Investment, and New Equity Financing.” Economic Journal 112: F54. [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, Aaron, Sophie Delecourt, Sharique Hasan, and Rembrand Koning. 2019. “When Does Advice Impact Startup Performance?” Strategic Management Journal 40 (3): 331–56. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Li-Yu, and Jui-Hung Lai. 2023. “Board Diversity and Post-IPO Performance: The Case of Technology Start-Ups.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Shijun. 2008. “Board Size and the Variability of Corporate Performance.” Journal of Financial Economics 87 (1): 157–76. [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, James J., Alex Bauerschmidt, and Charles W. Hofer. 1998. “The Determinants of New Venture Performance: An Extended Model.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 23 (1): 5–29. [CrossRef]

- Cole, Rebel A., and Tatiana Sokolyk. 2018. “Debt Financing, Survival, and Growth of Start-Up Firms.” Journal of Corporate Finance 50: 609–25. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, Massimo G., and Luca Grilli. 2005. “Founders’ Human Capital and the Growth of New Technology-Based Firms: A Competence-Based View.” Research Policy 34 (6): 795–816. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, Massimo G., Marcello Delmastro, and Luca Grilli. 2004. “Entrepreneurs’ Human Capital and the Start-Up Size of New Technology-Based Firms.” International Journal of Industrial Organization 22 (8–9): 1183–1211. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Arnold C., Francisco J. Gimeno-Gascon, and Carolyn Y. Woo. 1994. “Initial Human and Financial Capital as Predictors of New Venture Performance.” Journal of Business Venturing 9 (5): 371–95. [CrossRef]

- Corbett, Andrew C., Heidi M. Neck, and Dawn R. DeTienne. 2007. “How Corporate Entrepreneurs Learn from Fledgling Innovation Initiatives: Cognition and the Development of a Termination Script.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 31 (6): 829–52.

- Criaco, Giuseppe, Tommaso Minola, Paola Migliorini, and Carolina Serarols-Tarrés. 2014. “‘To Have and Have Not’: Founders’ Human Capital and University Start-Up Survival.” Journal of Technology Transfer 39 (4): 567–93. [CrossRef]

- Croce, Alessandra, Matteo Guerini, and Emanuele Ughetto. 2018. “Angel Financing and the Performance of High-Tech Start-Ups.” Journal of Small Business Management 56 (2): 208–28. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Yujia, Phillip T. Roundy, Jong-In Chok, Feng Ding, and Gun Byun. 2016. “‘Who Knows What?’ in New Venture Teams: Transactive Memory Systems as a Micro-Foundation of Entrepreneurial Orientation.” Journal of Management Studies 53 (8): 1320–47. [CrossRef]

- De Blick, Thibaut, Ine Paeleman, and Eddy Laveren. 2024. “Financing Constraints and SME Growth: The Suppression Effect of Cost-Saving Management Innovations.” Small Business Economics 62 (3): 961–86. [CrossRef]

- De Winne, Sophie, and Luc Sels. 2010. “Interrelationships between Human Capital, HRM and Innovation in Belgian Start-Ups Aiming at an Innovation Strategy.” International Journal of Human Resource Management 21 (11): 1860–80. [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Michael, Michael E. Porter, and Scott Stern. 2010. “Clusters and Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Economic Geography 10 (4): 495–518. [CrossRef]

- Dencker, John C., Marc Gruber, and Sonali K. Shah. 2009. “Pre-Entry Knowledge, Learning, and the Survival of New Firms.” Organization Science 20 (3): 516–37. [CrossRef]

- Dimov, Dimo. 2017. “Towards a Qualitative Understanding of Human Capital in Entrepreneurship Research.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 23 (2): 210–27. [CrossRef]

- Di Vito, Jennifer, and Kathleen Trottier. 2022. “A Literature Review on Corporate Governance Mechanisms: Past, Present, and Future.” Accounting Perspectives 21 (2): 207–35. [CrossRef]

- Dowling, Michael J., and Jeffrey E. McGee. 1994. “Business and Technology Strategies and New Venture Performance: A Study of the Telecommunications Equipment Industry.” Management Science 40 (12): 1663–77. [CrossRef]

- Drover, William, Lowell Busenitz, Sharon Matusik, David Townsend, Alex Anglin, and Guy Dushnitsky. 2017. “A Review and Road Map of Entrepreneurial Equity Financing Research: Venture Capital, Corporate Venture Capital, Angel Investment, Crowdfunding, and Accelerators.” Journal of Management 43 (6): 1820–53. [CrossRef]

- Du, Jiangtao, Jing Li, Bin Liang, and Zhiyu Yan. 2025. “Optimizing Sustainable Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: The Role of Government-Certified Incubators in Early-Stage Financing.” Sustainability 17 (9): 3854. [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, Jonathan T., Scott Shane, and Frédéric Delmar. 2006. “Multistage Selection and the Financing of New Ventures.” Management Science 52 (2): 220–32. [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M., and Claudia Bird Schoonhoven. 1990. “Organizational Growth: Linking Founding Team, Strategy, Environment, and Growth among US Semiconductor Ventures, 1978–1988.” Administrative Science Quarterly: 504–29.

- Eisenmann, Thomas. 2021. Why Startups Fail: A New Roadmap for Entrepreneurial Success. New York: Crown Currency.

- Feeser, Harry R., and George E. Willard. 1990. “Founding Strategy and Performance: A Comparison of High and Low Growth High-Tech Firms.” Strategic Management Journal 11 (2): 87–98. [CrossRef]

- Feldman, Maryann P., Johanna Francis, and Janet Bercovitz. 2005. “Creating a Cluster While Building a Firm: Entrepreneurs and the Formation of Industrial Clusters.” Regional Studies 39 (1): 129–41. [CrossRef]

- Felin, Teppo, and Todd R. Zenger. 2009. “Entrepreneurs as Theorists: On the Origins of Collective Beliefs and Novel Strategies.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 3 (2): 127–46. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Perez, Virginia, Pilar E. Alonso-Galicia, Lázaro Rodríquez-Ariza, and María del Mar Fuentes-Fuentes. 2015. “Professional and Personal Social Networks: A Bridge to Entrepreneurship for Academics?” European Management Journal 33 (1): 37–47. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Temprano, Maria A., and Fernando Tejerina-Gaite. 2020. “Types of Director, Board Diversity and Firm Performance.” Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 20 (2): 324–42. [CrossRef]

- Foss, Nicolai J., Peter G. Klein, and Samuele Murtinu. 2025. “Entrepreneurial Judgment, Uncertainty, and Resource Mobilization.” Review of Austrian Economics. [CrossRef]

- Gage, Deborah. 2012. “The Venture Capital Secret: 3 Out of 4 Start-Ups Fail.” Wall Street Journal, March 20.

- Gatignon, Hubert, Michael L. Tushman, Wendy Smith, and Philip Anderson. 2002. “A Structural Approach to Assessing Innovation: Construct Development of Innovation Locus, Type, and Characteristics.” Management Science 48 (9): 1103–22. [CrossRef]

- Giotopoulos, Ioannis, Athanasios Kontolaimou, and Aggelos Tsakanikas. 2017. “Antecedents of Growth-Oriented Entrepreneurship Before and During the Greek Economic Crisis.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 24 (3): 528–44. [CrossRef]

- Glick, William H., George P. Huber, Charles C. Miller, Douglas H. Doty, and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe. 1990. “Studying Changes in Organizational Design and Effectiveness: Retrospective Event Histories and Periodic Assessments.” Organization Science 1 (3): 293–312. [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, Vijay, and Praveen K. Kopalle. 2006. “Disruptiveness of Innovations: Measurement and an Assessment of Reliability and Validity.” Strategic Management Journal 27 (2): 189–99. [CrossRef]

- Gruber, Marc, Ian C. MacMillan, and James D. Thompson. 2013. “Escaping the Prior Knowledge Corridor: What Shapes the Number and Variety of Market Opportunities Identified before Market Entry of Technology Start-Ups?” Organization Science 24 (1): 280–300.

- Guo, Hong, An Guo, and Haibin Ma. 2022. “Inside the Black Box: How Business Model Innovation Contributes to Digital Start-Up Performance.” Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 7 (2): Article 100188. [CrossRef]

- Haans, Richard F. J. 2019. “What’s the Point of Being Different When Everyone Is? The Effects of Distinctiveness on Performance in Homogeneous versus Heterogeneous Categories.” Strategic Management Journal 40 (1): 3–27. [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Rolph E. Anderson, Ronald L. Tatham, and William C. Black. 1992. Multivariate Data Analysis. New York: Macmillan.

- Hashai, Niron, and Shaker A. Zahra. 2022. “Founder Team Prior Work Experience: An Asset or a Liability for Startup Growth?” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 16 (1): 155–84. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, Andrea M., Christoph Storz, and Lena Held. 2022. “Whom Do Nascent Ventures Search For? Resource Scarcity and Linkage Formation Activities during New Product Development Processes.” Small Business Economics 58 (1): 475–96. [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, Skye K., and Irwin B. Horwitz. 2007. “The Effects of Team Diversity on Team Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Review of Team Demography.” Journal of Management 33 (6): 987–1015.

- Ireland, R. Duane, Michael A. Hitt, and David G. Sirmon. 2003. “A Model of Strategic Entrepreneurship: The Construct and Its Dimensions.” Journal of Management 29 (6): 963–89. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Sara L., Karen Schnatterly, and Andrew D. Hill. 2013. “Board Composition Beyond Independence: Social Capital, Human Capital, and Demographics.” Journal of Management 39 (1): 232–62. [CrossRef]

- Kayser, Kristel, Ashwin Telukdarie, and Simon P. Philbin. 2023. “Digital Start-Up Ecosystems: A Systematic Literature Review and Model Development for South Africa.” Sustainability 15 (16): 12513. [CrossRef]

- Kelley, Douglas J., Slavica Singer, and Mike Herrington. 2012. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2011 Global Report. Babson College: Babson Park, MA.

- Ketchen Jr., David J., and Christopher W. Craighead. 2020. “Research at the Intersection of Entrepreneurship, Supply Chain Management, and Strategic Management: Opportunities Highlighted by COVID-19.” Journal of Management 46 (8): 1330–41. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Kwang Hyun, and Abdul A. Rasheed. 2014. “Board Heterogeneity, Corporate Diversification and Firm Performance.” Journal of Management Research 14 (2): 121.

- Kleinbaum, David G., Lawrence L. Kupper, and Keith E. Muller. 1988. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariate Methods. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: PWS-Kent.

- Kline, Rex B. 2004. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press.

- Korpysa, Jarosław, Updesh Singh, and Sukhdev Singh. 2023. “Validation of Decision Criteria and Determining Factors Importance in Advocating for Sustainability of Entrepreneurial Startups Towards Social Inclusion and Capacity Building.” Sustainability 15 (13): 9938. [CrossRef]

- Krugman, Paul. 1991. “Increasing Returns and Economic Geography.” Journal of Political Economy 99: 483–99.

- Kuratko, Donald F., and David B. Audretsch. 2009. “Strategic Entrepreneurship: Exploring Different Perspectives of an Emerging Concept.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33 (1): 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Landqvist, M., and F. Lind. 2019. “A Start-Up Embedding in Three Business Network Settings – A Matter of Resource Combining.” Industrial Marketing Management 80: 160–71. [CrossRef]

- Lange, Jan, Stanislav Rezepa, and Martina Zatrochová. 2024. “The Role of Business Angels in the Early-Stage Financing of Startups: A Systematic Literature Review.” Administrative Sciences 14 (10): 247. [CrossRef]

- Lechner, Christian, Michael Dowling, and Isabell M. Welpe. 2006. “Firm Networks and Firm Development: The Role of the Relational Mix.” Journal of Business Venturing 21 (4): 514–40. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Chung, Kee Lee, and Johannes M. Pennings. 2001. “Internal Capabilities, External Networks, and Performance: A Study on Technology-Based Ventures.” Strategic Management Journal 22 (6–7): 615–40. [CrossRef]

- Li, Ji-Yong, and Donald C. Hambrick. 2005. “Factional Groups: A New Vantage on Demographic Faultlines, Conflict, and Disintegration in Work Teams.” Academy of Management Journal 48 (5): 794–813. [CrossRef]

- Littunen, Hannu. 2000. “Networks and Local Environmental Characteristics in the Survival of New Firms.” Small Business Economics 15: 59–71. [CrossRef]

- Lukeš, Martin, and Jiří Zouhar. 2016. “The Causes of Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Discontinuance.” Prague Economic Papers 2016 (1): 19–36. [CrossRef]

- Lukeš, Martin, Marco C. Longo, and Jiří Zouhar. 2018. “Do Business Incubators Really Enhance Entrepreneurial Growth? Evidence from a Large Sample of Innovative Italian Start-Ups.” Technovation 82: 25–34. [CrossRef]

- Lyon, Douglas W., G. Thomas Lumpkin, and G. Greg Dess. 2000. “Enhancing Entrepreneurial Orientation Research: Operationalizing and Measuring a Key Strategic Decision-Making Process.” Journal of Management 26: 1055–85. [CrossRef]

- Mahieu, Julien, Francesco Melillo, and Peter Thompson. 2022. “The Long-Term Consequences of Entrepreneurship: Earnings Trajectories of Former Entrepreneurs.” Strategic Management Journal 43 (2): 213–36. [CrossRef]

- Mai, Khanh N., and Quoc H. Thai. 2024. “Entrepreneurial Competencies – A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of International Entrepreneurship: 1–77. [CrossRef]

- Manolopoulos, Dimitris, Karl-Erik Söderquist, and Xenia J. Mamakou. 2023. “Performance Impacts of Innovation Outcomes in Entrepreneurial New Ventures.” Entrepreneurship Research Journal 13 (4): 841–79. [CrossRef]

- Marvel, Matthew R. 2013. “Human Capital and Search-Based Discovery: A Study of High-Tech Entrepreneurship.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 37 (2): 403–19. [CrossRef]

- Marvel, Matthew R., Jason L. Davis, and Christopher R. Sproul. 2016. “Human Capital and Entrepreneurship Research: A Critical Review and Future Directions.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 40 (3): 599–626.

- Marvel, Matthew R., Dennis M. Sullivan, and Molly T. Wolfe. 2019. “Accelerating Sales in Start-Ups: A Domain Planning, Network Reliance, and Resource Complementary Perspective.” Journal of Small Business Management 57 (3): 1086–1101. [CrossRef]

- Maurer, Ingrid, and Mark Ebers. 2006. “Dynamics of Social Capital and Their Performance Implications: Lessons from Biotechnology Start-Ups.” Administrative Science Quarterly 51 (2): 262–92.

- McGee, Jeffrey E., Michael J. Dowling, and William L. Megginson. 1995. “Cooperative Strategy and New Venture Performance: The Role of Business Strategy and Management Experience.” Strategic Management Journal 16 (7): 565–80. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Chao, Matthew W. Rutherford, and John M. Pollack. 2017. “An Exploratory Meta-Analysis of the Nomological Network of Bootstrapping in SMEs.” Journal of Business Venturing Insights 8 (C): 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Miller, Toyah, and María del Carmen Triana. 2009. “Demographic Diversity in the Boardroom: Mediators of the Board Diversity–Firm Performance Relationship.” Journal of Management Studies 46 (5): 755–86. [CrossRef]

- Mincer, Jacob. 1958. “Investment in Human Capital and Personal Income Distribution.” Journal of Political Economy 66 (4): 281–302. [CrossRef]

- Mizruchi, Mark S., and Linda B. Stearns. 1988. “A Longitudinal Study of the Formation of Interlocking Directorates.” Administrative Science Quarterly: 194–210. [CrossRef]

- Müller, Kristina. 2010. “Academic Spin-Off’s Transfer Speed—Analyzing the Time from Leaving University to Venture.” Research Policy 39 (2): 189–99. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Gail B., Jon W. Trailer, and R. Duane Hill. 1996. “Measuring Performance in Entrepreneurship Research.” Journal of Business Research 36 (1): 15–23. [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, Jum C. 1978. “An Overview of Psychological Measurement.” In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders: A Handbook, 97–146.

- O’Leary-Kelly, Susan W., and Benito E. Flores. 2002. “The Integration of Manufacturing and Marketing/Sales Decisions: Impact on Organizational Performance.” Journal of Operations Management 20 (3): 221–40. [CrossRef]