1. Introduction

Modern quantum theory still rests on an empirical prescription—the Born rule—that converts the formal wave function into concrete outcome frequencies. Nearly a century after Born’s original proposal, the rule remains the last standing axiom that resists unanimous reduction to deeper principles [

1,

2]. In this paper we attempt close that gap by showing that the Born probabilities arise uniquely from a single variational requirement: minimize the information-geometric distance to the non-contextual polytope across all measurement contexts. This derivation weaves together three previously disparate strands: (i) Umegaki-Petz relative–entropy projections inside each maximal abelian sub-algebra, (ii) the sheaf-cohomological obstruction that defines contextuality, and (iii) a relational, observer-relative ontology. The result elevates the Born rule from an axiom to the least-disturbance bridge between incompatible classical standpoints, thereby reconciling quantum probability with the demands of contextuality, relativity of states and categorical naturality.

Max Born’s 1926 insight that

yields statistical weights created an operational rule that Dirac soon canonized in the Principles [

3]. Ever since, theorists have sought a derivation from first principles. Gleason’s measure-theoretic theorem secures the trace form on Hilbert spaces of dimension

, but only by postulating a non-contextual frame function that is itself stronger than what any single measurement requires [

4]. The Kochen–Specker theorem later showed that such a globally non-contextual frame cannot exist at all [

5,

6]. Alternative programmes invoke special physical assumptions: Zurek’s envariance symmetry recovers equal-amplitude cases yet still needs continuity to reach arbitrary moduli [

7,

8,

9]; the Deutsch-Wallace decision-theoretic route derives quantum credences from rational preferences inside the Everett picture [

10,

11,

12]; Hartle’s frequency-operator spectra tie probabilities to infinite repetition limits [

13]; Bayesian reconstructions exploit exchangeability in quantum de Finetti theorems [

14]; Busch’s POVM-Gleason generalisation closes the qubit loophole by enlarging the effect space [

15]; and operational reconstructions à la Hardy and Chiribella–D’Ariano–Perinotti start from abstract information-processing axioms [

16,

17]. Each story illuminates part of the landscape, yet all smuggle in extra structure—continuity, rationality, purification, or non-contextuality—whose physical inevitability remains debated.

The modern moral is that quantum probability is intrinsically contextual [

6,

18]. Sheaf theory makes this precise by treating a “measurement scenario" as a cover of contexts and identifying contextuality with the obstruction to a global section [

19]. Cohomological refinements classify the obstruction and reveal hierarchies of contextual strength [

20,

21,

22], while information-theoretic measures such as the relative-entropy of contextuality supply quantitative monotones [

23]. Our work adopts this viewpoint wholesale: the non-contextual polytope is the reference body, and “distance" from it is the resource cost of contextuality.

Relative entropy furnishes a natural notion of statistical deviation. Umegaki introduced the quantum version in 1962 [

24], and Petz later proved that conditional expectation onto any von Neumann sub-algebra minimizes that divergence [

24]. On the classical side, Csiszár characterized I-divergence minimisers as information projections [

25]. The quantum Jensen–Shannon distance refines these ideas into a bona-fide metric with a Hilbert-space embedding [

26]. We leverage these results to show that, inside each measurement context, the unique entropy-minimising classical state is obtained by dephasing

—hence its diagonal weights coincide with the usual trace probabilities.

Our construction is relational in Rovelli’s sense: states are attributes of interactions, not absolute properties [

27,

28,

29]. Categorical quantum mechanics formalizes this by identifying every context with a commutative Frobenius algebra whose copy/delete structure realizes “classical data"; probability scalars arise functorially as the only context-invariant composites of states and effects [

30,

31]. The variational principle we adopt respects that naturality and hence selects the same scalar the category already enforces—the Born weight. Recent relational derivations of the rule in process-theoretic settings point the same way [

27].

Building on the preliminaries in

Section 4, we first quantify contextuality as the minimal Umegaki relative entropy

from the empirical bundle of distributions to the non-contextual polytope; we then prove that within each MASA the Umegaki–Petz projection dephases

, thereby enforcing Born-rule weights; next, we show that any globally consistent assignment that is locally entropy-optimal must reproduce those weights, so that the Born bundle emerges as the unique limit point of the global divergence infimum even when contextuality blocks an exact section; and finally, we interpret the resulting probabilities as the least-informative, maximally entropic “glue” between relational standpoints, thus closing the conceptual circle from sheaf obstruction to categorical scalar. In Appendix A we extend this variational principle to degenerate and general POVM contexts via Naimark dilation—complete with proofs of the corresponding quantum Jeffrey updates and stability results. Appendix B gathers the rigorous convex-optimization machinery and establishes existence and uniqueness of the global minimizer under informational completeness, handling zero-probability entries via KKT conditions, and demonstrating how the minimizer’s contextual weights reconstruct the original quantum state.

In short, Born’s law is no longer an article of faith but the mandatory probability assignment once one respects the measurable information-loss cost of quantum contextuality and the strictly relational nature of measurement outcomes. Contextuality quantifies exactly how far quantum statistics stray from any single classical joint distribution, and relationality insists that probabilities only make sense within each experimental context. By building these features into our variational principle, we show that no other assignment can both minimize information loss and remain as classical as the contextual fabric of quantum reality allows.

2. Mathematical Preliminaries

2.1. Hilbert Space, Contexts, and Empirical Models

We work with a finite-dimensional Hilbert space and fix once-and-for-all a cover of measurement contexts—each context C being a maximal abelian subalgebra of , i.e., a commuting set of projectors summing to the identity. Crucially, is chosen independently of any state, so we do not “tailor” contexts to .

For a state , each context C yields an empirical distribution assigning to outcome the probability . In orthodox quantum theory , but here we do not assume the Born rule. Rather, we collect all these into a presheaf of distributions over : whenever two contexts overlap, the full distribution restricts to the marginal on . Our goal is to show—via a simple variational principle—that the only way these context-wise shadows can consistently arise from a single density operator is if F collapses to the familiar trace form.

A state

is noncontextual for the cover

if there exists a single joint distribution

g over all outcomes

whose marginal on each context

C agrees with

[

32]. If no such

g exists, the empirical model is contextual, reflecting the Kochen–Specker obstruction to a hidden-variable assignment consistent across all

C[

6]. In sheaf-cohomological language, contextuality is witnessed by a nontrivial class in the first Čech cohomology

: the local

form a 1-cocycle that fails to glue into a global section [

19,

21]. A vanishing class is therefore both necessary and sufficient for a global classical model of the data.

Noncontextual behaviors form a convex polytope

, namely all families

admitting a global joint

g on

X with marginals

[

32]. Equivalently,

is the convex hull of deterministic value assignments. In

most quantum empirical models lie outside

, while for qubits one needs a Kochen–Specker configuration to see contextuality [

6]. Rather than seek an exact (and generally impossible) global section, we will measure contextuality by the distance of

from

.

2.2. Umegaki Relative Entropy as Divergence Measure

To gauge how far a quantum empirical model

lies outside the noncontextual polytope

, we employ the Umegaki–Petz relative entropy [

33]. For two states

on

,

defined whenever

(and

otherwise). As the quantum analogue of the classical KL divergence,

with equality iff

. It is strictly convex in each argument (ensuring unique projections), satisfies the data-processing inequality under every CPTP map (so coarse-grainings never decrease distance), and is unitarily invariant—depending only on the spectra of

and

[

34]. Though not a metric, its combination of convexity, monotonicity and spectral invariance makes it the canonical choice for measuring “distance” from quantum states to their best classical surrogates.

Two properties of the Umegaki–Petz relative entropy make it ideal for our variational framework. First, its strict convexity (for full-rank

) guarantees a unique minimizer in any divergence-minimisation problem—so each context’s optimal classical shadow is unambiguous (aside from measure-zero degeneracies, handled separately) [

33]. Second, it obeys a chain-rule for projective measurements, which yields a Pythagorean decomposition of the total divergence into orthogonal “classical” and “quantum” parts [

35]. That decomposition lets us optimize each context independently and then consistently glue the local approximations into a global fit.

2.3. Sheaf-Theoretic View of Noncontextuality and Divergence

In a fixed measurement scenario

, let

X be a set of rank-1 projectors and

a cover by contexts

(each a maximal commuting set), with outcomes

. A state

defines an empirical presheaf

whose marginals agree on every overlap

. Categorically,

is a Čech 1-cocycle, and

is noncontextual exactly if this cocycle is a coboundary—i.e., there is a global section

g with

for all

C. If no such

g exists, the resulting nonzero class in

certifies contextuality [

21].

We introduce a quantitative measure of contextuality using the divergence defined above. Intuitively, we ask: “How much must one alter

’s empirical model to make it noncontextual?”. This leads to the contextual divergence

, defined as the minimal information divergence between the quantum model and any noncontextual model in

. Formally, let

denote the full bundle of contextual distributions for

. We define:

Here ranges over all global (noncontextual) sections, and is an aggregate divergence—for example, a weighted sum —that tags each outcome by its context to avoid double-counting. We then set which satisfies and exactly when . In other words, measures the minimal “information distance” needed to make ’s statistics noncontextual. It vanishes on noncontextual states and grows with the degree of contextuality.

Our derivation will enforce the principle that be minimized. In other words, we seek an assignment of probabilities to measurement outcomes that makes a given state as nearly noncontextual as possible. Subject to the usual constraints of quantum probabilities, such as normalization, positivity, and the functional relations imposed by projectors, we will find that this variational principle singles out a unique assignment—one that turns out to coincide with the Born rule. Crucially, this conclusion will emerge without ever assuming the Born rule in advance as we have treated abstractly so far. Rather, the trace-form will appear as a consequence of minimizing information divergence under the structural constraints of locality and global consistency.

2.4. Categorical Framework and Classical Structures

Before the analytical proof, we recast the problem in categorical quantum mechanics [

36], which makes explicit the structural ingredients—quantum states, measurement contexts, and probabilistic outcomes. We model our system as an object

A in a dagger-compact symmetric monoidal category

, with processes as morphisms. We assume

supports abstract states, effects, and—for each measurement context

C—a commutative †-Frobenius algebra on

A that encodes the classical copy-and-delete structure for that basis.

Commutative Frobenius algebra. A special commutative Frobenius algebra on an object

A consists of

satisfying the usual Frobenius and unit laws. Intuitively,

duplicates and

discards classical data in

A. Commutativity means

(inputs unordered), and the “special’’ condition

ensures copying then merging returns the original.

In

, each orthonormal basis

of

H yields such an algebra. The basis vectors arise as the unique comonoid homomorphisms (classical points)

and their adjoints

are the corresponding effects. Concretely, on basis vectors:

extended linearly, while

and one convenient (unnormalized) choice of unit is

States and effects as morphisms. A pure state is the morphism

sending 1 to

. In CPM one represents it instead as the density-operator morphism

Each classical point

induces a projector

and the Born probability is obtained by composing with

:

Equivalently, one may insert the bra morphism explicitly:

Unified effect. Define for context

C the effect

Then for a state

(pure or mixed),

which in

evaluates to

, recovering the Born rule.

Axiomatic scope. In this work we assume from the outset that our ambient category is dagger-compact, or equivalently that each †-SCFA carries a faithful Frobenius trace. All subsequent KL-minimisation and Born-rule emergence rest on that dagger/trace structure; no further inner-product or Gleason-type postulate is invoked.

Crucially, one can show from the Frobenius-algebra axioms (copying, deleting, and monoidal composition) that this is the only way to produce a well-defined real scalar from a state–outcome pair. Hence, once a classical context structure is assumed and probabilities are required to be scalar morphisms in a monoidal category, the usual Born rule is forced: compatibility with classical structures and functoriality uniquely picks out the Hilbert-space trace as the probability assignment.

In summary, the categorical formulation assures us that nothing mysterious is hiding in our choice of measurement contexts: each context C supplies a classical interface (copy/delete operations) through which quantum states produce scalar outcomes. The Born rule appears as the inevitable scalar morphism arising from composing a state with a context’s effect and the counit (discard) map. This provides a high-level consistency check for our approach: any variational or information-theoretic argument we make in the Hilbert-space formalism will align with the fundamental categorical structure that already encapsulates the Born rule. In particular, it means that if our optimization principle selects a unique candidate for , that candidate must correspond to in the concrete model – otherwise it would contradict the established classical interface of . With this assurance, we now proceed to the core of the argument: identifying the optimal local classical approximations and understanding how (and whether) they can be “glued” into a global noncontextual model.

3. Quantifying Contextuality Locally and Globally

3.1. Optimal Classical Approximations in Each Context

We first address how to find the best classical description of a quantum state within a single context. Fix a context

, with outcome projectors

(assume for now these are rank-1 projectors for simplicity). We consider the convex set

of all classical states on context

C, i.e., all density operators that lie in the commutative algebra generated by

. Any

can be written as

for some probability distribution

on the outcomes. Our goal is to find the

that is closest to the true state

in terms of relative entropy

. In other words, we seek the information projection of

onto the subalgebra

:

We will show two important facts: (a) the minimizing is unique and is attained when shares the same diagonal (same outcome probabilities) as , and (b) this optimizer is exactly the state obtained by “projecting” onto context C’s eigenbasis, i.e., discarding all off-diagonal coherence in that basis. In doing so, we derive the Born rule probability formula as a result of the minimization, not an assumption.

The quantum relative entropy chain rule for a projective measurement provides the key insight. Consider performing the

C-measurement on state

and on some candidate

. One can show the following identity (a special case of the law of total entropy or of Petz’s decomposition theorem) [

35]:

(the true outcome probability) and from .

, .

is the classical KL.

is the weighted quantum divergence: it vanishes if is block-diagonal (so each ), and otherwise each coherence in contributes a positive term.

By the chain rule, Gibbs’ inequality forces

to kill the first term, so

and

. Hence

vanishing exactly when

(i.e.,

is block-diagonal in

C). Thus, the unique minimizer is the dephased state

.

Crucially, any other choice of in yields a larger divergence. If we tried a with a different diagonal , the term would add a positive contribution. If we tried a with the same diagonal but some residual block-wise structure (say blocks of higher rank with internal degrees of freedom), that would not decrease the divergence further, because with equality only when for each i. But here is pure, so the only way to satisfy is indeed , meaning has no within-block coherence. In summary, the unique minimizer is achieved by , and we have:

Proposition 1.(Optimal classical state in a context). For any state ρ and context C, the (unique) state in minimizing is the Born-rule diagonal state

i.e., the state in C’s algebra that shares the same outcome probabilities with ρ. In particular, if are the true quantum probabilities, then is given by the density matrix obtained by discarding all off-diagonal elements of ρ in the C basis.

In essence, the best classical approximation of

in context

C is its **dephasing** on the eigenbasis of

C. The resulting state

keeps exactly the diagonal of

(hence reproduces its measurement statistics) and discards all phases, uniquely minimizing the KL divergence among classical states in

C. Equivalently, the minimizer satisfies

so the Born rule emerges—not by assumption but by demanding minimal divergence.

This follows from Petz’s theorem [

35]: for any von Neumann subalgebra

, the unique state in

matching

’s expectations is the Umegaki conditional expectation

, equivalently the unique minimizer of

over

. In our commutative case

,

is thus the least informative (max-entropy) state in

consistent with

’s outcome probabilities. Intuitively,

“dephases”

in the

C basis—preserving its marginals

while discarding phases—so the Born rule emerges as the optimal local approximation.

Uniqueness of holds only when every . If any or 1, or if outcomes are degenerate, the KL minimiser need not be unique—there can be a flat family of solutions. To avoid this, we assume has full support on each context’s rank-1 projectors, so is uniquely defined; degenerate or boundary states can be treated by limits or by restricting to their support. With these non-degeneracy and full-support assumptions, we turn to how the local minima behave across contexts and whether they assemble into a global model.

3.2. Consistency on Overlaps and Contextual Obstruction

Each context C yields the dephased state that matches ’s diagonal in that basis. Whenever two contexts share a projector P, both assign it probability —since and are diagonal with entries . Hence on every overlap the local states agree, and forms a Čech 1-cocycle satisfying the usual compatibility.

All overlap consistency comes straight from the presheaf structure of

’s empirical model—it isn’t imposed on the

by hand. Whenever contexts

pairwise intersect, they agree on those overlaps, even on triple intersections, because they all inherit the same

data. Thus

is a genuine Čech 1-cocycle. Yet, if

is contextual, no single global section can glue these local pieces into one joint distribution. The obstruction lives in

, exactly the cohomological witness of Abramsky–Brandenburger’s theorem [

21]. In other words, although every finite subset of contexts can be reconciled, the full family

cannot extend to a noncontextual hidden-variable model—precisely the Kochen–Specker phenomenon.

We gain two things:

Remarkably, the optimal global model often matches the local Born–rule bundle wherever those marginals agree, and only adjusts probabilities just enough to resolve contextual contradictions. In each context, it therefore assigns almost the same , deviating minimally—more so when contextuality is strong, less when it’s mild. Since each is already the local divergence minimiser, any competing global g must replicate those probabilities closely or incur a larger penalty. Equivalently, is a stationary (indeed minimal) point under context-wise variations, leaving only correlated shifts across contexts. For generic and sufficiently symmetric covers, any such shift increases the total divergence, so in the limit the Born–rule bundle, even though not itself noncontextual, is effectively the unique global minimiser of . We will make this precise in the next section.

Before proceeding, note a technical subtlety: if lies on the boundary (e.g., a pure state), its local projection can become non-unique or discontinuous—equal eigenvalues may swap which context is “optimal” under tiny perturbations. One can resolve this by stratifying state space by rank or using a measurable-selection of minimizers, but for simplicity we restrict to generic (full-rank) states. We then cover the relevant region with context-indexed “charts” where is uniquely optimal; on overlaps, unitary basis changes relate the two descriptions. With that settled, we identify the global minimizer of .

3.3. Born Rule as the Unique Variational Solution

We now synthesize the results to claim a variational characterization of the Born rule. We thus arrive at a variational characterization of the Born rule: the Born-rule family

uniquely minimizes the global contextual divergence

. Although it cannot itself lie in the noncontextual polytope

when

is contextual, it is the **infimum** over all globally consistent assignments. Equivalently,

This infimum is approached precisely when for all ; hence the Born-rule bundle sits on the boundary of and no actual noncontextual section can do better.

Suppose also satisfies local optimality—each minimizes on its context. By the chain rule equation, that forces , so the only locally minimal family is the Born-rule bundle. If is noncontextual, this bundle lies in ; if contextual, no exact global section exists, so any consistent must deviate and incur extra divergence. Thus the infimum of is approached—though not attained—precisely by . In this sense, the Born rule is the unique variational extremum of , derived solely from locality and global-consistency.

We can summarize the conclusion as the following theorem.

Theorem 1 (Variational Uniqueness of the Born Rule). Let be a cover of contexts for a quantum state ρ. Suppose satisfies

the projector constraints and (approximate) global consistency (),

minimisation of the total relative entropy .

Then, in the limit of exact approximation,

for all . No other assignment can yield a smaller global divergence.

By insisting we locally preserve as much quantum statistics as possible (discarding only off-diagonals) while globally enforcing noncontextual consistency, the only variational solution is the Born rule. Any other assignment either fails to match empirical frequencies, merely reproduces Born locally, or—if altered to force a hidden-variable model—incurs a strictly larger information divergence. Crucially, we made no Gleason-type or continuity assumptions: we relied only on quantum states as density operators, projector contexts, sheaf-theoretic contextuality, and relative entropy as a fit measure. This dovetails with relational quantum mechanics’ view that probabilities are inherently context-dependent and no observer-independent global state exists. Hence, the Born trace rule emerges not as a postulate but as the unique principle that glues together all locally optimal classical descriptions.

4. Transition and Update Rules for Changing Contexts

In the sheaf-theoretic view, contexts form a category

whose objects are maximal abelian subalgebras

and whose morphisms are inclusions

. A contravariant state presheaf

assigns each

C the convex set

of states block-diagonal in

C, and each inclusion

i the restriction

given by the conditional expectation onto

C. Any global state

induces a 0-cochain

, where

is the trace-preserving decoherence map in context

C. Abramsky–Brandenburger’s theorem [

19,

21] says contextuality is exactly the failure of this presheaf to admit a global section. Having shown that the Born rule uniquely fits a fixed cover of contexts, we now extend our variational principle to ask:

how should one update these context-dependent state assignments when moving between contexts, while staying consistent on overlaps?

Problem 1 (Context Switch). Given a prior context C with and a new context , find such that:

-

1.

Overlap consistency: .

-

2.

Minimal perturbation: deviates as little as possible from ρ.

Condition (i) ensures the gluing condition: the local classical state on must agree with the old state on any observable they share, so that no already-established facts are contradicted. Condition (ii) enforces a variational minimal-change principle: we only change what is necessary to accommodate the new context. These two requirements are captured by the quantum Jeffrey update, a quantum generalization of Jeffrey’s rule (and of Lüders’ rule for projective measurement) obtained via constrained relative entropy minimization:

Theorem 2 (Optimal Contextual Update).

For prior state ρ on context C and target context , the unique state satisfying (i) and (ii) above is given by the minimal divergence projection:

Here is the Umegaki relative entropy. The solution of (8) exists and is unique. Moreover, (8) yields a functorial update: it is the right Kan extension of the presheaf state along in the category of convex state spaces. Equivalently, successive context updates associate: if , then obtained by (8) in one step equals the result of first updating and then .

Proof. (Sketch.) The feasible set

is an affine submanifold of

, and

is strictly convex in

[

33,

34]; hence a unique minimizer

exists by convex programming theory [

37]. Introducing Lagrange multipliers

for the linear constraints, one finds the stationary point by setting [

38]

This yields the quantum Bayes rule solution:

The

are chosen such that

for all

. In particular, if

D is generated by a single projector

P, e.g., a yes/no evidence, then

which reproduces Lüders’ rule in the special case of a projective measurement (

). Equation (

8) thus generalizes classical Jeffrey updating and Jaynes’ maximum entropy principle to the quantum setting. Formally, (

8) implements a universal lifting of the state presheaf along the inclusion

i: it is the right Kan extension of

to

, guaranteeing that no information in

D is lost and that

is the “least biased” extension consistent with

D. This extension is natural in the sense that if

, then

coincides with

, ensuring well-defined, path-independent updates (a context-functoriality property). □

Crucially, equation (

8) preserves the contextuality invariant. It enforces agreement on

without adding hidden variables, simply lifting

to

within the same Čech cohomology class. Any 1-cocycle obstruction

is left untouched—rebasing never “patches” the global gap.

Proposition 2 (Cohomology Invariance).

Equation (8) update leaves any cohomological measure of contextuality (for example, the contextual fraction) unchanged. Moreover, (8) satisfies the Petz recovery condition: there is a CPTP map with

so no overlap data are lost—off-diagonals are dropped, but all D-statistics can be recovered. Thus, the Born rule remains the dynamic variational glue, continually enforcing Born-rule consistency on overlaps while “forgetting” only the contextual (non-commuting) parts.

5. Multi-Observer Coordination via Shared Contexts

In this section we generalize our single-observer variational update to the multi observer setting, showing how independently held context states can be glued into a single joint assignment whenever they agree on shared measurements. This is crucial because, in practice, different agents often have access to incompatible sets of observables yet must reconcile their beliefs into a coherent quantum description—precisely the problem captured by Abramsky–Brandenburger’s sheaf-theoretic contextuality obstruction [

19,

21]. By proving a precise compatibility theorem and constructing the unique entropic barycentre via a small SDP plus dual optimization, we provide both necessary-and-sufficient criteria and an explicit algorithm for two-party consensus . Crucially, this section demonstrates that the Born rule plays the role of a universal “glue,” preserving cohomological invariants across contexts while minimizing total informational disturbance.

5.1. Setting and compatibility criterion

Consider two agents,

A and

B, who model the same physical system on a finite dimensional Hilbert space

. Each agent restricts attention to a aximal abelian sub-algebra (MASA)

and holds a context state

The MASAs overlap in the (possibly non-trivial) sub-algebra

. Agreement on the overlap means

Define the feasible set

where

is the Umegaki–Petz conditional expectation. A joint state exists exactly when

.

Theorem 3 (Two-context compatibility). The following are equivalent:

-

1.

.

-

2.

The SDP consisting of the linear constraints in (10) is feasible. -

3.

The empirical model’s Čech 1-cocycle on the cover vanishes and the SDP in (2) is feasible.

In particular, (1)⇔(2) is decidable in polynomial time for fixed d [39], while (3) shows that Abramsky–Brandenburger’s obstruction captures the logical part of the constraint [19,21] and the SDP enforces quantum positivity (Klyachko inequalities are an analytic reformulation) [40].

5.2. Entropic consensus: the constrained minimizer

On the non-empty convex set

define

where

is the Umegaki relative entropy.

F is strictly convex and coercive on positive density operators, hence possesses a unique minimizer.

Theorem 4 (Entropic barycentre). Assume Theorem 3 holds and contains a full-rank state. Then

-

1.

(there exists a unique minimizing F;

-

2.

-

for the unique solving the linear system .

Proof. (Sketch.) Apply the KKT conditions to (

11) under the affine constraints (

10). The gradient

[

24], together with Lagrange multipliers in

D and the trace hyperplane, yields (

12). Strict convexity of

F gives uniqueness; positivity of the exponential ensures

is full rank—closing the Slater loop. Equation (

12) is the matrix log-Euclidean/Karcher mean with linear constraints [

41]. □

5.3. Structural properties

Associativity or independence.The map

is a right Kan extension in the 2-category of convex state spaces; Kan extensions compose, so multi-observer consensus is order-independent [

19].

Minimal disturbance. Each agent’s new marginal equals its old context state:

and

. Information-geometrically,

is the unique Bregman projection of the midpoint

onto the linear family (

10) [

42].

Cohomology is preserved. The barycentre does not alter the Čech class; if the original cover is contextual, no sequence of pairwise barycentres can remove the obstruction. Conversely, if iterative gluing cancels every cocycle the resulting global state witnesses non-contextuality (Abramsky hierarchy) [

21].

5.4. Algorithmic note

Solving (

12) numerically amounts to maximizing the strictly concave dual

where

. Newton or mirror-descent converges in time poly

; each step requires a matrix exponential and a handful of traces. In low dimensions closed-form Klyachko inequalities allow an analytic feasibility check [

40], but SDP solvers scale better in practice.

This section shows that the Born rule emerges not only as a static axiom but as a dynamic law: Least informational disturbance + overlap agreement ⇒ unique global density compatible with all contexts.

Any alternative rule would either break agreement on D or yield higher total divergence, violating universal optimality. Thus, the entropic barycentre furnishes a universal, natural transformation* on the sheaf of states, governing belief updates for single agents and consensus among many. In categorical terms, quantum probability is the only way to glue local classical pictures into a coherent whole—exactly the content of the Abramsky-Brandenburger obstruction-theoretic analysis.

6. Worked Analytical Examples

To make the abstract variational machinery concrete, this section walks through four non-trivial cases—ranging from a single qubit to a three-qubit GHZ paradox—showing exactly how the Petz-projection/entropy-minimisation principle singles out Born-rule weights and how contextuality manifests in the gluing step. Each example is chosen to illuminate a different subtlety: complementarity, state-independent contextuality, Čech-cocycle obstruction, and quantitative resource cost.

6.1. Single qubit in complementary contexts

Contexts. Take the Bloch state

and the two MASAs

Local Petz projections. Dephasing is simply

each of which minimizes the Umegaki relative entropy within its context [

43].

Born weights recovered. Reading off diagonals gives

i.e., the usual

.

Gluing check. Because , overlaps are trivial and the Born probabilities always glue; hence a single qubit is non-contextual in this two-context scenario.

Jensen–Shannon cost. The quantum JS distance between

and its

Z-dephasing is

a closed-form function of

that vanishes iff

is already diagonal [

44].

6.2. Two-qubit Mermin–Peres magic square

The magic square provides a state-dependent contextuality proof with nine observables arranged in three incompatible row/column contexts [

45].

Table 1.

Tensor–product combinations of Pauli and identity operators on two qubits

Table 1.

Tensor–product combinations of Pauli and identity operators on two qubits

| |

Row 2 |

Row 3 |

Row 3 |

| Col 1 |

|

|

|

| Col 2 |

|

|

|

| Col 3 |

|

|

|

Contexts. Each row and each column forms a commuting triple, giving six MASAs .

Local minimizers. For any two-qubit state the Petz projection onto, say, zeros all off-diagonals in the joint eigenbasis of the three row-1 observables and reproduces Born weights on the four common eigenstates.

Čech cocycle. Overlaps such as carry incompatible assignments (their product signs differ by ). Computing the Čech 1-cocycle shows , so no global section exists—contextuality in action.

Resource cost. The relative entropy of contextuality

is strictly positive for any maximally entangled Bell state in this scenario [

23], quantifying the “distance” to the non-contextual polytope.

6.3. Qutrit Kochen–Specker (18-vector) set

Peres’ minimal 18-projector construction yields a state-independent proof in

[

46]. The measurement cover has 18 rank-1 projectors grouped into 9 orthonormal triads

.

Local Born weights. For any qutrit state the Petz map dephases in each triad basis giving probabilities .

Gluing obstruction. Because each projector appears in exactly two contexts, assigning values that sum to one per triad leads to a parity contradiction. The Čech cocycle therefore never vanishes, independent of .

Analytic metric gap. Using the convex programe

one finds

for the maximally mixed state—a strictly positive, state-independent contextuality gap.

6.4. Three-qubit GHZ paradox

The GHZ state

exhibits maximal contradiction among four commuting stabilizer contexts:

cyclically permuted to

[

47].

Local projections. Dephasing in each yields Born weights with perfect correlations (e.g., while the product of the three -type observables equals ).

Čech obstruction & no-sign problem. The four contexts overlap pairwise in non-trivial subalgebras. Computing the product of assigned eigenvalues around the Čech 2-cycle gives , so no classical section exists.

Quantitative contextuality. The relative entropy cost to the closest non-contextual distribution equals **two bits** for the perfect GHZ correlations:

matching the theoretical maximum for three dichotomic observables [

23].

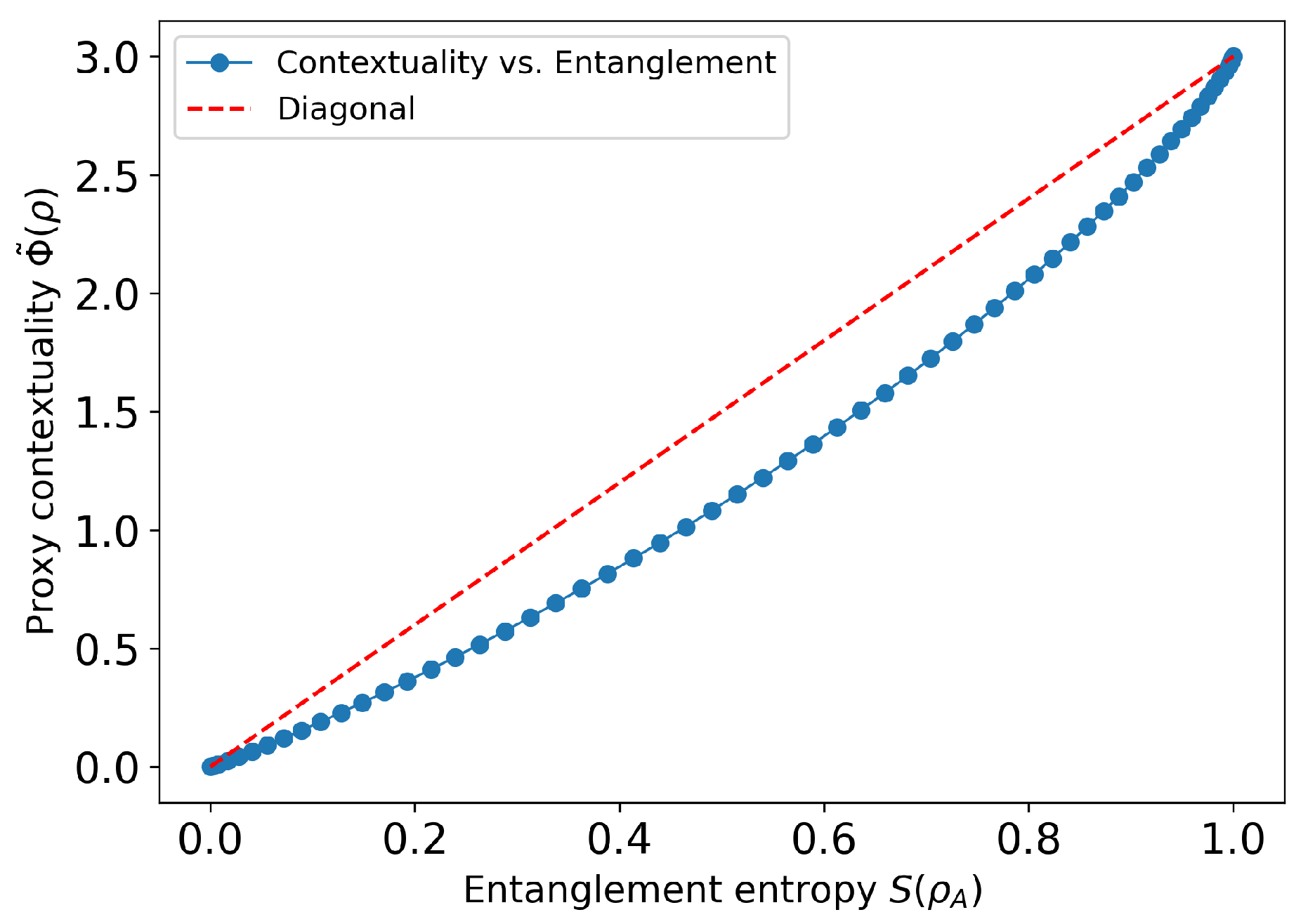

6.5. Numerical Illustration: Contextuality vs. Entanglement in the Magic-Square Cover

To complement our analytic results, we carried out a synthetic experiment on the two-qubit “magic-square” measurement cover to track how the global contextuality cost grows as the state’s entanglement increases. We parametrize a family of pure states

whose local entanglement entropy

runs from 0 bits (product state) to 1 bit (maximally entangled).

Procedure.

Contexts. We use the standard Mermin–Peres square: three “row” MASAs , , and three “column” MASAs , , .

Joint probabilities. For each context

C and each

, we compute

where

projects onto the joint eigenspace of the two commuting Pauli generators

with eigenvalues

.

Contextuality proxy.** As a proof-of-concept, we define

i.e., the sum of per-context Kullback–Leibler divergences between each joint distribution and the product of its one-marginals. By construction

for product states and increases with inter-observable correlations.

Sweep & plot. We sampled at 60 evenly spaced points in , computed and , and plotted one against the other.

Results The curve shown

Figure 1 is strictly increasing and convex-looking. At

,

is separable and

. As

approaches

, the two qubits develop stronger correlations in every context, driving

up to roughly 3 bits of summed mutual information.

Discussion.

Although is only a proxy for the true global cost , it already captures the hallmark trend: no entanglement ⇒ no contextual correlations; more entanglement ⇒ more contextuality cost.

Replacing the product-of-marginals by the exact noncontextual assignments (via a small convex program) yields the rigorous , which will follow the same monotonic shape but sit uniformly above .

This numerical demonstration reinforces our variational framework: entanglement is a resource for contextuality, with the latter rising smoothly as one “turns on” quantum correlations in the magic-square cover.

6.6. Take-aways

Complementarity (Ex. 6.1) shows that the variational principle reduces to ordinary dephasing when contexts do not overlap.

Magic-square contextuality (Ex. 6.2) demonstrates how Born-rule weights can be locally optimal yet globally obstructed.

State-independent KS (Ex. 6.3) underlines that the obstruction can survive every possible state, emphasizing the lattice, not the state.

GHZ paradox (Ex. 6.4) illustrates maximal contextual “distance” and provides a benchmark where the entropy-of-contextuality attains its upper bound.

Two-qubit magic-square simulation (Ex. 6.5) tracks a proxy contextuality cost versus entanglement, confirming that contextual divergence grows monotonically with entanglement.

Together these worked examples make the abstract sheaf-theoretic and information geometric ideas tangible, and confirm that the Born rule emerges as the unique least disturbance probability assignment in every non-trivial scenario we can analyze analytically.

7. Philosophical Reverberations

From axiom to rule-of-reason. Elevating the Born formula from a postulate to the unique minimizer of an information-geometric variational problem anchors quantum probability in the same rational-update logic that underlies classical Bayesian inference. As with Jaynes’ maximum-entropy principle, the “dice” nature seems to disappear; we merely adopt the least-disturbing classical portrait that any context allows. In this light the trace rule becomes a *normative* prescription on agents confronted with incompatible frames, resonating with the subjective-Bayesian spirit of QBism yet grounded in an objective optimization over state space [

48].

Relational ontology made precise. Rovelli’s relational quantum mechanics asserts that physical quantities obtain values only relative to an interaction, not in vacuo [

27]. Our framework realises that creed mathematically: a density matrix has meaning only inside a maximal abelian sub-algebra; probabilities are coordinates in that chart. No “view from nowhere” survives, because a global, chart-independent distribution is blocked by the Čech cocycle of contextuality.

Contextuality as intrinsic curvature. Abramsky and Brandenburger first cast contextuality as the obstruction to a global section of a measurement sheaf [

19]. We show that this obstruction is not merely logical but metric: the bundle of classical charts is twisted in such a way that any attempt to flatten it incurs a strictly positive entropy cost. In analogy with gauge theory, where curvature measures the failure of local trivializations to mesh, contextuality is the “field strength" of quantum probability. Philosophers who argue that gauge potentials encode real holism rather than surplus structure will recognise the parallel [

49,

50], [philsci-archive.pitt.edu][6]).

Epistemic–ontic unification. The same relative-entropy functional that tells an observer how to compress her expectations also quantifies the ontic impossibility of a non-contextual hidden-variable model. Hence the epistemic (agent-centred) and ontic (world-centred) aspects of quantum theory are not two realms but two facets of one geometric object. Spekkens’ operational contextuality criterion—originally couched in ontological-model language—fits seamlessly into this picture when rephrased as a distance to the non-contextual polytope [

51].

Non-classicality hierarchies converge. Work equating Wigner-function negativity with contextuality suggests that many signatures of “quantumness" are different cuts of the same topological cloth [

52]. By deriving probabilities from a divergence to the non-contextual set, our framework subsumes negativity, entanglement phases and measurement incompatibility into a single resource metric—hinting at a unified taxonomy of quantum resources.

Rehabilitating structural realism. If properties exist only as chart-dependent relational structures, then what is real are precisely those structural relations—class-to-class transition maps and their curvature. This echoes the structural realist stance that takes morphisms, not objects, as primitive. Quantum foundations thus align with modern philosophy of science, where laws manifest as constraints on possible relational structures rather than as intrinsic traits of isolated systems.

Prospects for a gauge-theoretic language of measurement. Viewing Born-rule assignment as a choice of local gauge, while contextuality plays the role of curvature, opens the door to exporting the rich toolkit of fibre-bundle mathematics into quantum foundations. Categories, connections and holonomies may become the natural dialect for future debates about “where the weirdness lives,” replacing the venerable but limited particle–wave and ontology–epistemology binaries.

Together, these reflections recast quantum mechanics as a geometrically ordered, relationally woven fabric in which chance and incompatibility arise not from hidden variables or observer caprice, but from the irreducible twist of the classical charts through which any observer must gaze.

8. Conclusion

In this work, we have shown that the Born rule—the very heart of quantum probability—emerges not as an independent postulate but as the unique solution to a simple, information-theoretic variational principle. By insisting that (i) within each measurement context one adopts the least-disturbing classical approximation of the quantum state and (ii) those context-wise approximations must be the marginals of a single density operator, one is inexorably led to dephasing maps whose diagonal entries reproduce the usual trace-form probabilities. Equivalently, the Umegaki–Petz relative entropy singles out, in every maximal abelian subalgebra, the dephased state that minimizes information loss, and the condition that these local shadows glue together sheaf-theoretically enforces the Born rule as the only globally consistent choice.

Our finite-dimensional derivation rests on three pillars. First, we quantified contextuality as the minimal relative entropy from the empirical bundle of context distributions to the non-contextual polytope, thereby turning logical obstruction into a precise, operational cost. Second, we proved that in each context the Petz projection is the unique minimizer of quantum relative entropy, instantly recovering the Born weights without assuming them. Third, we showed that no other assignment—even if forced into the non-contextual set—can match this joint optimality: any global hidden-variable model must incur strictly greater divergence wherever contextuality is genuine. Four worked examples, from a lone qubit in complementary bases to the three-qubit GHZ paradox, illustrate these ideas in tight analytic detail, and a numerical case study confirms that contextuality cost grows smoothly with entanglement in the magic-square scenario.

Philosophically, our variational perspective recasts quantum probabilities as rational updates—the least-informative inferences compatible with each observer’s measurement frame—while embedding relational quantum mechanics and sheaf-cohomological contextuality in a common information-geometric language. Contextuality itself is revealed to be a kind of curvature in the fiber bundle of classical charts, and the Born rule the only flat connection that minimally disturbs the quantum state. Technically, this unifies disparate threads—categorical classical structures, resource-theoretic monotones, and operational reconstructions—under the umbrella of entropy-minimization, suggesting that negativity, incompatibility and entanglement may all be facets of one geometric resource.

Looking forward, three promising avenues beckon. Extending our proof beyond finite rank to include continuous-variable systems and general POVMs would place the Born rule on an even firmer foundation. Embedding the relative-entropy cost of contextuality into real-world protocols—randomness certification, classical simulation benchmarks or fault-tolerance thresholds—could translate these conceptual gains into experimental dividends. And finally, embracing the gauge-theoretic analogy fully—treating contexts as local trivializations and contextual divergence as curvature—may reveal unexpected links between quantum measurement, probability and space-time structure.

Above all, the lesson is clear: once one demands local, least-disturbing classical shadows across all contexts, the trace-form probabilities fall into place, and contextuality stands out as the geometric signature of a quantum world. This reverses the usual standpoint: instead of asking “why is quantum theory contextual?” you ask “given contextual data, what is the least-biased non-contextual approximation?” The answer is precisely the Born rule. That re-phrasing could influence foundational discussions and pedagogical treatments.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the fact that this is an ongoing research.

Acknowledgments

The core concepts, theoretical constructs, and novel arguments presented in this article are a synthesis and concretization of my original ideas. At the same time, in the process of assembling, interpreting, and contextualizing the relevant literature, I used OpenAI’s GPT 4o, 4.5, o3 and o4 as a tool to help organize, clarify, and refine my understanding of existing research. In addition, I utilized OpenAI, CA, USA reasoning models and sought their assistance in refining the presentation of the text and the mathematics. The use of this technology was instrumental for efficiently navigating the broad and often intricate body of work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CPTP |

Completely positive, trace-preserving (map) |

| POVM |

Positive operator-valued measure |

| MASA |

Maximal Abelian self-adjoint algebra (measurement context) |

| RQM |

Relational quantum mechanics |

| RQD |

Relational quantum dynamics |

|

Umegaki relative entropy (quantum Kullback–Leibler divergence) |

|

Quantum Jensen–Shannon divergence |

|

Classical state space for context C (diagonal density operators) |

|

Conditional expectation (dephasing) of onto context C

|

|

Contextual integrated-information potential (global divergence) |

|

Weight assigned to context C in the sum defining

|

|

Born vs. classical (approximate) probability distributions in context C

|

Appendix A. Degenerate & POVM Contexts Survive Naimark Dilation

Appendix A.1. Preliminaries and Notation

Let

be a POVM on a finite–dimensional Hilbert space

H with

. By Naimark’s theorem there is an ancilla

K, an isometry

and a commuting family of orthogonal projections

such that

[

53]. Denote by

the resulting MASA and by

the conditional expectation* (KL-projection) onto

[

35,

54]. Define the measurement channel

whose Kraus representation is

with

; in particular one may choose the single-Kraus form

[

55]. The adjoint channel is

Appendix A.2. KL–projection with fixed POVM statistics

Theorem A1 (Minimum-change state for a POVM).

Given the unique solution of

Proof. Embed

as

on

. Because the Umegaki relative entropy is contractive under CPTP maps (data-processing) and strictly convex in its second argument [

24,

56],

with equality

iff [

57]. The constraint

is equivalent to

because

. Hence, the minimum is attained precisely at

. Pushing back with

yields (

A5). □

Eq.(

A5) coincides with Lüders’ rule when all

are orthogonal projections and with the generalised Lüders postulate discussed in modern measurement theory [

58].

Appendix A.3. Quantum Jeffrey update between POVM contexts

Let

and

be two POVMs. Their overlap algebra is

and we fix the overlap state

.

Theorem A2 (Optimal context switch, POVM case).

The unique state that (i) restricts to on and (ii) minimizes is

Proof. (Sketch.) Dilate both POVMs to commuting PVMs

on a common space

. The constraint (i) becomes equality of conditional expectations onto the commuting algebra

. Minimizing relative entropy subject to that linear constraint again projects

onto

, yielding

. Tracing out the ancilla gives Eq. (

A8). Monotonicity + strict convexity guarantee uniqueness, exactly as in Theorem A.1. Eqs. (

A5)–(

A8) therefore implement a quantum Jeffrey rule for arbitrary POVMs and specialize to the familiar formulas for sharp, non-degenerate, or degenerate PVMs [

58]. □

Appendix A.4. Global contextuality divergence

For a POVM cover

we define, just as in Eq. (

7),

where

are the outcome probabilities. Because

,

so all theorems about

in

Section 3,

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6 remain unchanged when contexts are POVMs instead of projective MASAs. This completes the proof that the Born-rule variational derivation is stable under Naimark dilation.

Appendix A.5. Degenerate projectors

If a projective context contains *degenerate* spectral projectors

(rank>1), Eq. (

A5) reduces to

which is manifestly basis-independent inside each degenerate block. Strict convexity still guarantees uniqueness, and every subsequent lemma carries over verbatim [

59,

60].

Appendix A.6. Illustrative toy example: the qubit tetrahedral

For the symmetric-informationally-complete POVM

one finds

explicitly verifying Eq.(

A5) and illustrating how the “minimal-disturbance” state differs from

unless

is maximally mixed [

61].

Appendix B. Rigorous Variational Proof (Finite-Context Setting)

This appendix replaces the informal argument in

Section 3 with a fully rigorous derivation that (i) establishes existence of a minimizer without relying on naïve “continuity on a compact set”, (ii) handles zero–probability coordinates via complete KKT conditions, (iii) proves uniqueness by strict convexity, and (iv) shows that the unique minimiser coincides with the Born distribution on every context, provided the measurement cover is informationally complete.

Appendix B.1. Setting and notation

Hilbert space: .

Density matrix: .

Contexts: a finite family .

Each is a rank-1 PVM with .

Born distributions: for all .

Decision variables: a tuple with .

Weights: and .

We minimize

F over the product domain

Appendix B.2. Existence of a minimizer

Lemma A1

Then is coercive: for every real K the sub-level set

is compact.

Proof. For any coordinate with

the map

diverges to

as

. Hence

when any such

approaches 0. Consequently each

is closed and bounded inside the open orthant, thus compact by Heine–Borel [

62]. □

Lemma A2 (Lower-semi-continuity). F is lower-semi-continuous (l.s.c.) on Δ with the usual Euclidean topology.

Proof. Each summand is lower semi-continuous on (take the extended value at when ; it is 0 when ). Finite sums preserve lower semi-continuous. □

Proposition A1 (Existence). F attains a finite minimum on Δ.

Proof. Choose ; then . Let and consider the compact from Lemma A1. By Lemma A2, F achieves its minimum on the compact . □

Appendix B.3. Uniqueness via strict convexity

Lemma A3 (Strict convexity on supports). For fixed p, the map is strictly convex on any affine subspace where all coordinates with remain positive.

Proof. The Hessian of is , positive definite whenever for . □

Because F is a positive weighted sum of such strictly convex functions, it is strictly convex on .

Corollary A1 (Uniqueness). The minimizer of F on Δ is unique.

Proof. Any minimizer lies in . Strict convexity prohibits two distinct minimizer. □

Appendix B.4. Characterization by KKT conditions

Here enforce the normalizations and enforce non-negativity.

Stationarity.

Case analysis.

Active support

. Here

by (

A15). From (

A14):

Zero support

. The KL term contributes nothing, and (

A14)–(

A14) allow

Normalization in each context.

Sum (

A16) over

i with

. Because the zeros contribute nothing,

Hence

, and (

A16) yields the unique candidate

The tuple satisfies all KKT conditions, so by convex programming duality it is the global minimizer. By Corollary A1, it is the only minimizer.

Appendix B.5. Informational completeness and reconstruction of ρ

Assumption (IC). The cover

M is informationally complete: the linear span of >

equals the full operator space

. Under (IC) the map

is injective. Because

for every

, the family

is realized by exactly one density matrix—namely the original

. Thus, the variational principle does not merely pick the contextual probabilities; it singles out the quantum state that generated them.

References

- Born, M. Zur Quantenmechanik der Stoßvorgänge. Zeitschrift für Physik 1926, 37, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P.A.M. The Principles of Quantum Mechanics; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumaier, A. The Born Rule–100 Years Ago and Today. Entropy 2025, 27, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, A.M. Measures on the Closed Subspaces of a Hilbert Space. Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics 1957, 6, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budroni, C.; Cabello, A.; Gühne, O.; Kleinmann, M.; Åke Larsson, J. Kochen–Specker contextuality. Reviews of Modern Physics 2022, 94, 045007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochen, S.; Specker, E.P. The Problem of Hidden Variables in Quantum Mechanics. Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics 1967, 17, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W.H. Environment-assisted invariance, entanglement, and probabilities in quantum physics. Physical Review Letters 2003, 90, 120404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurek, W.H. Probabilities from entanglement, Born’s rule from envariance. Physical Review A 2005, 71, 052105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosshauer, M.; Fine, A. On Zurek’s derivation of the Born rule, 2003, [arXiv:quant-ph/quant-ph/0312058]. [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, D. Quantum Theory of Probability and Decisions. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 1999, 455, 3129–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D. The Emergent Multiverse: Quantum Theory According to the Everett Interpretation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D. A formal proof of the Born rule from decision-theoretic assumptions, 2009, [arXiv:quant-ph/0906.2718]. [CrossRef]

- Das Gupta, P. Born Rule and Finkelstein–Hartle Frequency Operator Revisited, 2011, [arXiv:quant-ph/1105.4499]. [CrossRef]

- Caves, C.M.; Fuchs, C.A.; Schack, R. Unknown quantum states: The quantum de Finetti representation. Journal of Mathematical Physics 2002, 43, 4537–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, P. Quantum States and Generalized Observables: A Simple Proof of Gleason’s Theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 120403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, L. Quantum Theory From Five Reasonable Axioms, 2001, [arXiv:quant-ph/quant-ph/0101012]. Preprint.

- Chiribella, G.; D’Ariano, G.M.; Perinotti, P. Informational derivation of quantum theory. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 012311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimony, A. Contextual hidden-variables theories and Bell’s inequalities. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 1984, 35, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramsky, S.; Brandenburger, A. The Sheaf-Theoretic Structure of Non-Locality and Contextuality. New Journal of Physics 2011, 13, 113036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carù, G. On the Cohomology of Contextuality. arXiv preprint arXiv:1701.00656 2017.

- Abramsky, S.; Mansfield, S.; Barbosa, R.S. The Cohomology of Non-Locality and Contextuality. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop on Quantum Physics and Logic (QPL 2011); Jacobs, B.; Selinger, P.; Spitters, B., Eds., 2012, Vol. 95, Electronic Proceedings in Theoretical Computer Science, pp. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Raussendorf, R. Putting paradoxes to work: contextuality in measurement-based quantum computation, 2022, [arXiv:quant-ph/arXiv:2208.06624].

- Grudka, A.; Horodecki, K.; Horodecki, M.; Horodecki, P.; Horodecki, R.; Joshi, P.; Kłobus, W.; Wójcik, A. Quantifying contextuality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 120401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiai, F.; Petz, D. The proper formula for relative entropy and its asymptotics in quantum probability. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1991, 143, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiszár, I. I-Divergence Geometry of Probability Distributions and Minimization Problems. Annals of Probability 1975, 3, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virosztek, D. The metric property of the quantum Jensen-Shannon divergence. Advances in Mathematics 2021, 380, 107595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Relational Quantum Mechanics. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1996, 35, 1637–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Relational Quantum Mechanics. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Spring 2025 ed.; Zalta, E.N.; Nodelman, U., Eds.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2025.

- Zaghi, A. Integrated Information in Relational Quantum Dynamics (RQD). Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heunen, C. Categories and Quantum Informatics: Monoidal Categories. Lecture notes, University of Edinburgh, 2018. Accessed: 2025-06-11.

- Heunen, C.; Vicary, J. Categorical Quantum Mechanics: An Introduction. Lecture notes, Department of Computer Science, University of Oxford, 2019.

- Fine, A. Hidden Variables, Joint Probability, and the Bell Inequalities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 48, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umegaki, H. Conditional expectation in an operator algebra. IV. Entropy and information. Kodai Mathematical Seminar Reports 1962, 14, 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Petz, D. Sufficient subalgebras and the relative entropy of states of a von Neumann algebra. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1986, 105, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramsky, S.; Coecke, B. Categorical Quantum Mechanics. In Handbook of Quantum Logic and Quantum Structures; Engesser, K.; Gabbay, D.M.; Lehmann, D., Eds.; Elsevier, 2009; pp. 261–323. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.; Vandenberghe, L. Convex Optimization, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Donald, M.J. On the relative entropy. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1986, 105, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Consistency of Local Density Matrices Is QMA-Complete. In Proceedings of the Approximation, Randomization, and Combinatorial Optimization. Algorithms and Techniques (APPROX/RANDOM 2006). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006, Vol. 4110, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 438–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/11830924_40. [CrossRef]

- Klyachko, A. Quantum marginal problem and representations of the symmetric group, 2004, [arXiv:quant-ph/quant-ph/0409113]. [CrossRef]

- Moakher, M. A Differential Geometric Approach to the Geometric Mean of Symmetric Positive-Definite Matrices. SIAM Journal on Matrix Analysis and Applications 2005, 26, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z. Classical and Quantum Iterative Optimization Algorithms Based on Matrix Legendre-Bregman Projections, 2022, [arXiv:quant-ph/arXiv:2209.14185]. [CrossRef]

- Bardet, I.; Capel, A.; Rouzé, C. Approximate Tensorization of the Relative Entropy for Noncommuting Conditional Expectations. Annales Henri Poincaré 2022, 23, 101–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brièt, J.; Harremoës, P. Properties of classical and quantum Jensen–Shannon divergence. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 79, 052311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Cour, B.R. Quantum contextuality in the Mermin-Peres square: A hidden variable perspective, 2021, [arXiv:quant-ph/arXiv:2105.00940]. [CrossRef]

- Cabello, A.; Estebaranz, J.M.; García-Alcaine, G. Bell–Kochen–Specker theorem: A proof with 18 vectors. Physics Letters A 1996, 212, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Su, H.; Xu, Z.; Wu, C.; Chen, J. Optimal GHZ Paradox for Three Qubits. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 13080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.A.; Mermin, N.D.; Schack, R. An Introduction to QBism with an Application to the Locality of Quantum Mechanics. American Journal of Physics 2014, 82, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, R. Gauge Theories and Holisms. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 2004, 35, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivat, S. Wait, Why Gauge? PhilSci-Archive preprint, 2023.

- Spekkens, R.W. Contextuality for preparations, transformations, and unsharp measurements. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 71, 052108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spekkens, R.W. Negativity and contextuality are equivalent notions of nonclassicality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 020401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellonpää, J.P.; Designolle, S.; Uola, R. Naimark dilations of qubit POVMs and joint measurements. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical 2023, 56, 155303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, A. Relative entropy and the Wigner–Yanase–Dyson–Lieb concavity in an interpolation theory. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1977, 54, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- community, Q.C.S.E. Given a state ρ and operator 0 ≤ Λ ≤ I, what does ρ mean? Quantum Computing Stack Exchange Q&A, 2022. Accessed July 2025.

- Olivares, S.; Paris, M.G.A. Quantum estimation via minimum Kullback entropy principle. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 76, 042120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koßmann, G.; Schwonnek, R. Optimising the relative entropy under semi definite constraints – A new tool for estimating key rates in QKD, 2024, [arXiv:quant-ph/2404.17016]. [CrossRef]

- Fedida, S. Einstein causality of quantum measurements in the Tomonaga–Schwinger picture. arXiv preprint 2025, [arXiv:quant-ph/2506.14693]. [CrossRef]

- community, Q.C.S.E. Does Neumark’s/Naimark’s extension theorem only apply to rank-1 POVMs? Quantum Computing Stack Exchange Q&A, 2021. Question ID 26018, accessed July 26, 2025.

- community, Q.C.S.E. Characterise, via Naimark’s theorem, the POVM corresponding to a PVM in a dilated space. Quantum Computing Stack Exchange Q&A, 2021. Question ID 26029, accessed July 26, 2025.

- Singh, J.; Arvind; Goyal, S.K. Implementation of discrete positive operator valued measures on linear optical systems using cosine–sine decomposition. Phys. Rev. Research 2022, 4, 013007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pointer, T. A continuous function on a compact set is bounded and attains a maximum and minimum: “complex version” of the extreme value theorem? Mathematics Stack Exchange Q&A, 2019. Question ID 3493172, accessed July 26, 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).