Background

Collaborating Centres (CCs) are specialized institutions designated by the World Health Organization (WHO) to provide scientific or technical support in specific health areas [

1]. The role of CCs is pivotal in global public health efforts, as they participate in a wide range of WHO activities, including the implementation of programs, development of evidence-based guidelines, global monitoring of diseases, standardization of terminology or procedures, dissemination of information, and training [

1].

However, achieving sustainability for CCs is a complex goal. These centers are structurally linked to their host institutions, relying on their resources, and adhering to their frameworks and regulations. Simultaneously, they are functionally linked to WHO through a joint work plan agreed upon for each designation period, requiring them to allocate resources to this plan and adhere to WHO’s operating rules. Successful collaboration, which is essential for re-designation and sustainability, depends on the progression and completion of the work plan [

1]. This places significant responsibility on the CC director to integrate the strategic and managerial challenges of both WHO and the host institution to ensure the center’s sustainability.

An objective indicator of successful collaboration between WHO and its Collaborating Centres is the duration of their active status. Despite the ongoing need for WHO to rely on top-level health institutions to address global public health challenges, the number of active CCs is decreasing. WHO official database states that 769 CCs are active up to February 2025, with 2267 CCs having lost their label since the creation of WHO [

2]. Most of the CCs are from high-expertise institutions in the health sector, primarily in Europe and Americas [

2]. The loss reported by region have been 1091 in European Region (EUR), 556 in Americas Region (AMR), 266 in Western Pacific Region (WPR), 153 in South-East Asia Region (SEAR), 101 in African Region (AFR) and 100 in Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR). This represents a significant loss for global health in terms of established expertise and economic status, which are crucial for large-scale collaboration [

2].

The hypothesis is that the decrease in active CCs is due to a failure to meet the optimal conditions for successful collaboration. It could alternatively be explained by a downsizing strategy decided to address an overlapping between different CCs’ topics or to rebalance the geographical distribution of CCs network between WHO regions [

13].

Objectives

The current work focuses on the strategic and management conditions necessary for successful collaboration from a perspective of CC directors’ leadership capabilities. Due to the lack of available data on this matter, a qualitative research approach is employed to shed light on the strategic management challenges of CCs and the needs from the field to address them.

Considering a CC as a manageable entity in the health sector, and the approach involves applying management science theoretical frameworks to a CC and testing if they align with the concrete management reality and needs reported by experienced top managers of CCs worldwide.

Methods

The work is divided into three parts: (a) Conceptual Framework: Identification of important strategic and management contributors to the sustainable development of a CC based on theoretical contributions from management science. (b) Empirical Observation: Data collection from CC directors about their reported management and strategic challenges, experiences, and needs. This includes a discussion of the potential fit between the conceptual framework and the data collected from CCs’ concrete experiences from different socio-economic contexts and cultures worldwide. (c) A set of recommendations and needs for sustainable management, derived from high-level managers of continued active CCs worldwide.

1. Conceptual Framework for Strategic Management of a Collaborating Centre

Strategy is defined as creating a unique and valuable position within a set of activities. There is an inextricable link between the development and execution of strategy and leadership [

3]. The role of the leader in strategic plan development is to have a sustainability goal for the institution, which involves developing a strategic plan that integrates specific features of the organization, such as missions, core purpose, vision, strategic options, opportunities, and threats [

3]. The conceptual framework for strategic success, developed by Collins and Porras [

4], is based on the ability to manage continuity (a) core ideology elements that should never change: core purpose and core values; while taking advantage of needed changes and progress to accomplish what an organization aspires to (b) envisioned future.

A clear consideration of missions and functional scope is essential [

4]. CCs have concrete goals and expected deliverables formalized in a four-year work plan. However, operational effectiveness does not guarantee an organization’s sustainability. To last, a CC must identify and preserve its core purpose, which is the organization’s most fundamental reason for being. This core purpose inspires change and success by fuelling people’s motivation to carry out the organization’s activities.

Core values are the essential and enduring tenets of an organization [

4]. WHO has five core values:

trust, commitment to excellence, integrity, collaboration, and

caring [

5]. CCs are expected to align with these values and never compromise them under any condition. The hypothesis is that enduring CCs align with WHO’s core values and use them as guiding principles in their collaborative activities.

The envisioned future is a big and bold objective that takes 10 to 30 years for the organization to attain [

4]. It should be inspiring, catalyse commitment, and stimulate progress within the organization [

4]. Vivid descriptions of this Big, Hairy, Audacious Goal convey conviction and passion and translate into a clear and engaging mental image of the organization’s future [

4]. Designing a strategy for a CC involves clarifying the positioning on strategic factors for key stakeholders (WHO and the hosting institution). Two strategic options that drive institutional sustainability are "fit" and "strategic positioning” [

3]. The "fit" involves making activities interact and reinforce one another, while "strategic positioning" involves using distinctive activities to achieve sustainability in a competitive context [

3]. The designation by WHO as a Collaborating Centre is a formal and time-limited opportunity for strategic positioning in a specific area of expertise, which is important for the designated health organization to capitalize upon.

Building a strategic plan for an organization requires defining key actions needed to achieve strategic goals [

6]. This involves moving from good strategy conceptualization to productive actions to guarantee successful strategy implementation [

6]. Successful strategic leadership involves having an organizational-level strategic thinking from the early stages of strategy design [

6]. Identifying threats that could face strategy execution, whether internal or external factors, is crucial [

6].

A CC is a particular health organization at the crossroads of WHO and the institution of affiliation at a strategic and operational level. No executive requirements (leadership or management proficiency) are made by WHO for the profile of the head of the designated entity [

1]. However, leadership skills are critical to the enduring strategic existence of a CC.

Leadership is a key role in strategy design and execution but is often subject to misconceptions. Effective leadership is not about innate vision or charisma but about acquired skills to sharpen and stretch [

7]. Leadership is about coping with fast change and adapting to it, while management is about coping with complexity, bringing order and predictability [

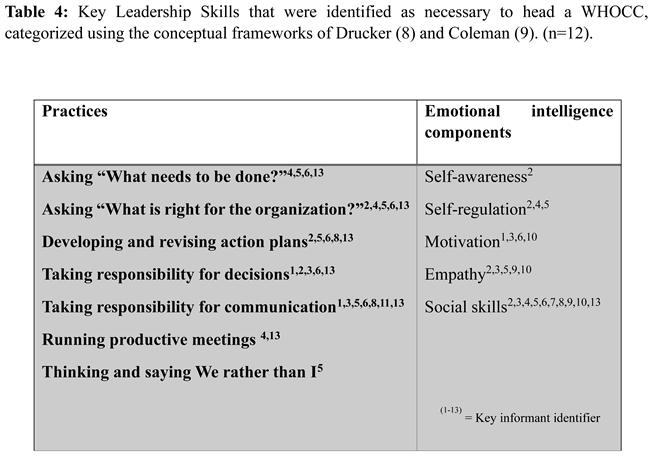

7]. Effective leaders exhibit eight main practices: asking "what needs to be done?" and "what is right for the enterprise?", developing and revising action plans, taking responsibility for decisions and communication, focusing on opportunities rather than problems, running productive meetings, and thinking and saying "we" rather than "I [

8]." Other important characteristics of effective leaders include self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills [

9].

CCs are engaged in implementing the agreed work plan in a timely manner, which requires planning specific projects and coordinating resources to achieve them within a defined timeframe by WHO. Project management is a codified process involving planning, build-up, implementation, and closeout, with clear role definition, team members’ selection, and priority setting [

10].

A CC is engaged in various activities jointly agreed upon for the four-year designation period. Funding these activities is a daily challenge for a CC. The major factors include the lack of financial support from WHO, the need to cover resources and costs of work plan achievement through the core budget or extra-budget resources of the institution of affiliation, and the limited funding sources due to WHO’s Framework of Engagement with Non-State Actors (FENSA), which controls for potential conflicts of interest resulting from financial links with the private sector [

1].

Communication is a crucial leadership challenge in organizations, both internally (inspiring, motivating, integrating differences, resolving conflicts, coordinating, and aligning people with the organization’s vision and decisions) and externally (persuading partners and stakeholders and gaining visibility) [

12]. Effective leaders must manage communication carefully, precisely, and regularly to achieve success and performance. A CC shares these communication issues with specific features regarding communication rules set by WHO, such as engaging actively in a collaborative network of CCs, communicating with them, sharing expertise, opportunities, and building synergies through a regular, effective, and efficient system of communication [

1].

2. Empirical Observation Through Field Testing of the Conceptual Framework

The main objective is to confront observable data from the field (reasoned opinions and declared needs) of currently active CCs with the conceptual framework above developed for strategic and management challenges. The approach is an exploratory naturalistic study based on one-to-one interviews with key informants having special expertise in managing Collaborating Centres as directors worldwide. The purpose is to access thoughts and feelings of participants through a phenomenological design. A flexible research design based on three stages and two different sampling strategies is used to increase the quality of the sample and transferability of findings. Centers considered were those reported as having an active status and designated for at least two years. An interview guide was developed to standardize administration to different key informants, including general background, free narrative, short open responses, dichotomous (yes/no) and free text responses. The interviews were audio recorded, and the interviewer took handwritten field notes during face-to-face and phone calls’ interviews. Regarding remote and deferred interviews conducted through emails, key informants received the interview script on a Word format document, which included written information on completion rules of the interview. Warranted anonymity of interviews was a cornerstone of the present data collection due to the sensitivity of the explored field to confidentiality and discretion. Audio recording of face-to-face and phone call interviews was done upon agreement from participants. They were transcribed verbatim by the interviewer and complemented with handwritten notes. Written answers were considered as a transcript.

Data collected were coded according to different theoretical frameworks developed in the first section of the draft. Coding consisted in "core purpose," "envisioned future," "strategic positioning," "actionable strategies," "leadership skills," "management challenges," and "recommendations for practice”. Narratives’ interpretation was based on theming according to a phenomenological standpoint to reflect the key informant’s own perspective. Themes were created as the transcripts’ analysis was progressing from the first to the last interview. Participants were assigned a key informant identifier, a number used in exponent (1-13) in the results presented.

Results

The inclusion period lasted from June 2019 to February 2020 and yielded a total of 13 interviews, of which 5 were face-to-face, 1 through phone call, and 7 through email. Interviews were conducted in three languages (French, English, and Spanish). Audio recordings lasted a total of 6 hours. Respondents were mostly male (85%), with a mean of 10 years (2 -25) of experience directing a CC. They represented CCs having 17 years of activity (2-30), and continuous labelling for 1 to 8 periods (4-32 years). Five WHO regions were covered: EUR, WPR, AMR, SEAR, and EMR. Countries represented were Australia, Canada, Chile, China, Italy, Japan, Morocco, Switzerland, and Thailand. Collaborating topics covered neurology, mental health, e-health, nutrition, food safety, primary care, addiction medicine, humanitarian, psychosocial, and infection control.

An interesting richness of data was achieved: all continents were represented, all levels of income countries were included, a wide range of experience width in a leading position of a CC was involved, gender diversity was present, diverse fields of collaboration were explored, and various host institutions were included (hospitals, universities, and research centers). The sample size for this qualitative research was sufficient because of data satisfaction [

14], meaning that the saturation point was reached after a few interviews and no new information was obtained from further interviews for the opinions and practices explored. According to Marshall et al.’s [

15] requirements for qualitative sampling, adequate data had been collected for a detailed analysis and findings could be transferable to other CCs.

All through the interviews, there emerged a strong sense of commitment, idealism, and passion of CCs executives, despite realism about the challenges and their tasks’ complexity. Many examples of innovation, solution-oriented leadership attitudes, and self-motivation capabilities arose from open discussions with them.

Directors reported spontaneously elements reflecting their core purpose for leading a CC figure1). The figure highlights the unique motivations and values that drive their leadership. Core purposes were singular to each of them and constituted their "why" for leading a CC. They all reported that this meaningful purpose helped them overcome numerous daily challenges in their mission.

Participants reported spontaneously several core values in their duty as directors of CCs (figure 2). All exhibited at least one shared core value with WHO, most aligned with 3 to 4 of the 5 WHO values, and 1 CC shared them all. The most shared core values were "professionals committed to excellence in health" and "collaborative colleagues and partners."

Free narratives allowed identification of the 13 directors envisioned future for their CC, it corresponded to Big Hairy Audacious Goals (BHAGs) and vivid descriptions were made of them. The aims are reflected in text and visual icons corresponding to their statements (figure3).

The most accurate strategic positioning for CCs was found to be the one based on benefits for public health and clinical practice at global l and country levels. Respondents reported that CCs constituted key elements in decision-making in the health sector, mostly in public health and clinic at both global and country levels. According to their experience, directors additionally reported that the usually misconceived natural attractors to work in CCs (label and career progression) do not verify in the field. Indeed, CC collaborators were reported to be usually attracted by the international recognition of a research team, by a health topic or by a pioneering scientist working in the CC rather than by the CC label. Directors advised that if career advancement was aimed to be used as an effective strategic positioning argument, structural efforts were needed at an organizational level.

The qualitative research has a main limitation represented by subjectivity bias since the researchers are from the same work ground. It is a matter of fact which is not necessarily negative because it was the condition to understand the topic at hand, its complexity, and its boundaries and to ensure confidence setting for fellow workers to engage and to share the richness of their experiences and knowledge. Another limitation is the partial blind navigation through this topic about the major stakeholder’s perspective and decision-making record, other than that available online or known by CCs’ leaders interviewed.

Expert Recommendations and Operational Solution Tracks

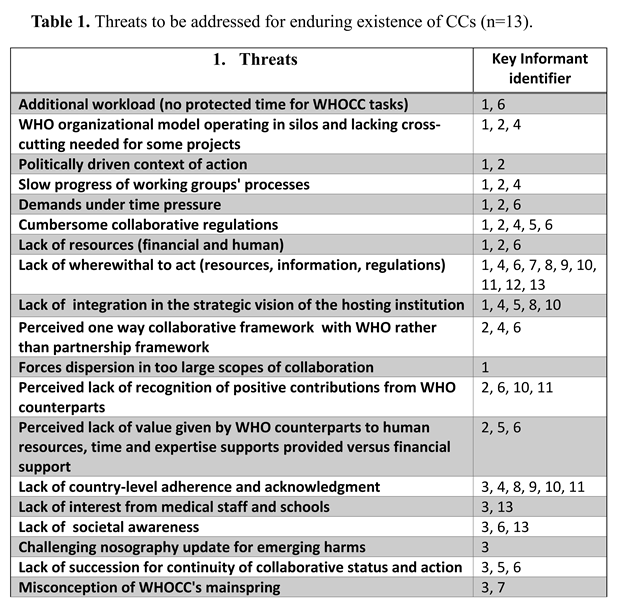

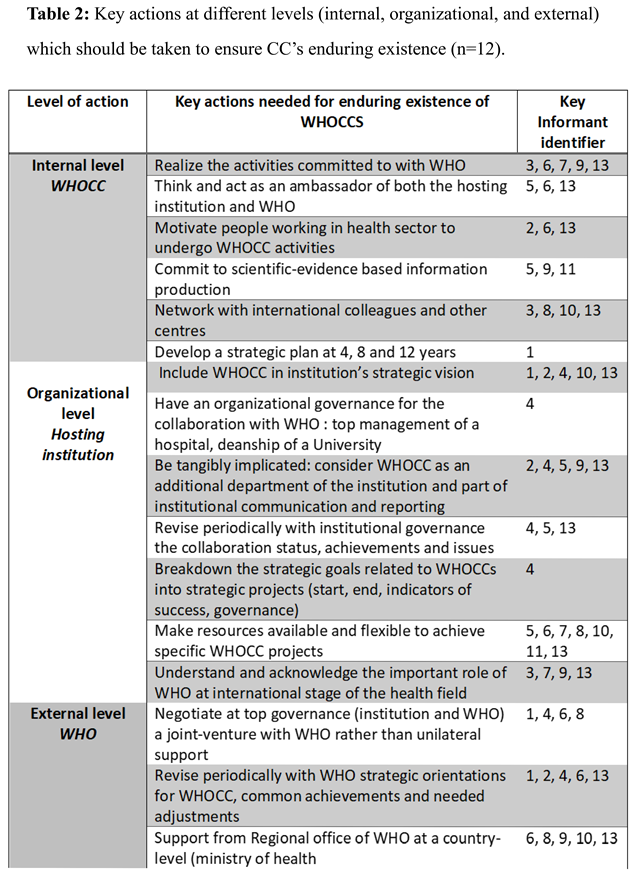

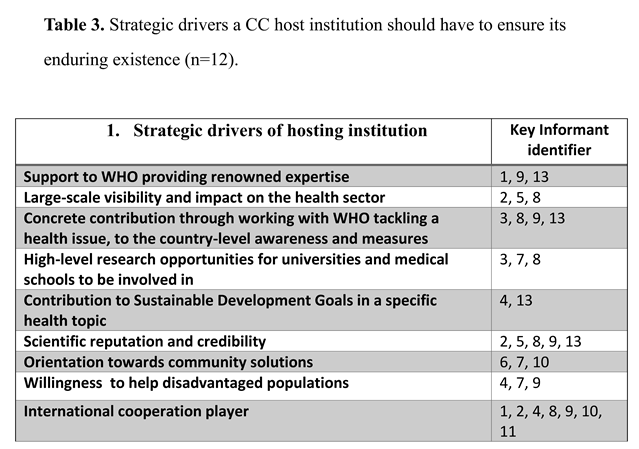

In addition to important conceptual findings for CCs management and strategic orientations and execution presented above, the present work yielded concrete practical field-based recommendations (

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4).

The threats identified by the key informants highlight the multifaceted challenges faced by CCs in their collaboration with WHO and their host institutions (

Table 1). Addressing these threats requires a comprehensive approach that includes operational, resource, collaborative, contextual, and specific operational strategies. By implementing the suggested mitigation strategies, CCs can enhance their sustainability and effectiveness in supporting global health efforts (

Table 1).

The key actions needed to ensure the enduring existence of CCs identified by the informants, are outlined in

Table 2. They highlight the multifaceted approach required to ensure the enduring existence of CCs. These actions span internal, organizational, and external levels, addressing various aspects of collaboration, resource management, strategic planning, and governance. By implementing these actions, WHOCCs can enhance their sustainability, effectiveness, and impact in supporting global health efforts. The involvement of all stakeholders, including WHO, hosting institutions, and WHOCCs themselves, is crucial for the successful implementation of these actions and the achievement of long-term goals.

The strategic drivers that host institutions should prioritize to ensure the enduring existence and effectiveness of CCs are outlined in

Table 3. These drivers span support to WHO, visibility, contribution to health issues and research, reputation and credibility, community and population focus, and international cooperation. By prioritizing these strategic drivers, host institutions can enhance the sustainability, effectiveness, and impact of CCs in supporting global health efforts. The involvement of all stakeholders, including WHO, host institutions, and CCs themselves, is crucial for the successful implementation of these strategic drivers and the achievement of long-term goals.

The leadership practices identified by the informants (

Table 4) highlight the importance of emotional intelligence in effective leadership within CCs. These practices span self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skill, each contributing to the leader’s ability to drive progress, achieve results, and build strong relationships within the organization. By prioritizing these practices, leaders can enhance their effectiveness and contribute to the sustainability and success of CCs. The involvement of all stakeholders, including WHO, host institutions, and CCs themselves, is crucial for the successful implementation of these leadership practices and the achievement of workplan goals.

The solution tracks co-constructed with expert leaders worldwide to overcome the management challenges facing a CC covered two critical issues, financial and communication challenges.

Conclusion

The sustainability of CCs requires a comprehensive approach that integrates strategic management, effective leadership, and operational solutions to address financial and communication challenges. By implementing the recommended actions and involving all stakeholders, including WHO, hosting institutions, and CCs themselves, we can enhance the sustainability, effectiveness, and impact of CCs in supporting global health efforts. This collaborative approach is essential for addressing the complex challenges faced by CCs and ensuring their continued contribution to global public health.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contribution

SA: designed the project, performed the research, analyzed data, draft and review BS: supervised the work and revised the first draft

Declarations of interest

None

References

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2025). WHO Collaborating Centres. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/about/collaboration/collaborating-centres.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2025). WHO Collaborating Centres Global databases. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/whocc/Search.aspx.

- Porter, M.E. , What is Strategy? Harvard Business Review, 1996. 74(6): p. 61-78.

- Collins, J.C. and J.I. Porras, Building your company’s vision. Harvard Business Review, 1996. 74(6): p. 43-56.

- World Health Organization. Our values, our DNA. 2020 [cited 2020 1st March ]; Available from:

https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/our-values.

- Moat, A. and A. Birnik, Developing actionable strategy. Business Strategy Review, 2008. Spring 2008: p. 28-33.

- Kotter, J.P., What leaders really do. Harvard Business Review, 2001. Best of HBR (December 2001): p. 23-34.

- Drucker, P.F. , What makes an effective executive. Harvard Business Review, 2004. 82(6): p. 58-63.

- Goleman, D. , What makes a leader? Harvard Business Review, 2004. Emotional intelligence(January ).

- Austin, R.D. and L. R., eds. L'essentiel pour manager un projet. Les clés pour un business efficace, ed.

L.r.d.l.H.B. Review. 2016, Prisma.

- Luthra, A. and R. Dahiya, Effective Leadership is all About Communicating Effectively: Connecting Leadership and Communication. International Journal of Management and Business Studies, 2015. 5(3): p. 43-48.

- Mankins, M.C. and R. Steele, Turning great strategy into great performance, in On strategy, Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation, Editor. 2011. p. 209-228.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2020). Evaluation of WHO's work with Collaborating Centres -

Evaluation Brief - May 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/evaluation-of-who-collaboratingcentres---

evaluation-brief---may-2020.

- Sutton, J. and Z. Austin, Qualitative Research: Data Collection, Analysis, and Management. Can J Hosp Pharm, 2015. 68(3): p. 226-31.

- Marshall, M.N. , Sampling for qualitative research. Fam Pract, 1996. 13(6): p. 522-5.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).