Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

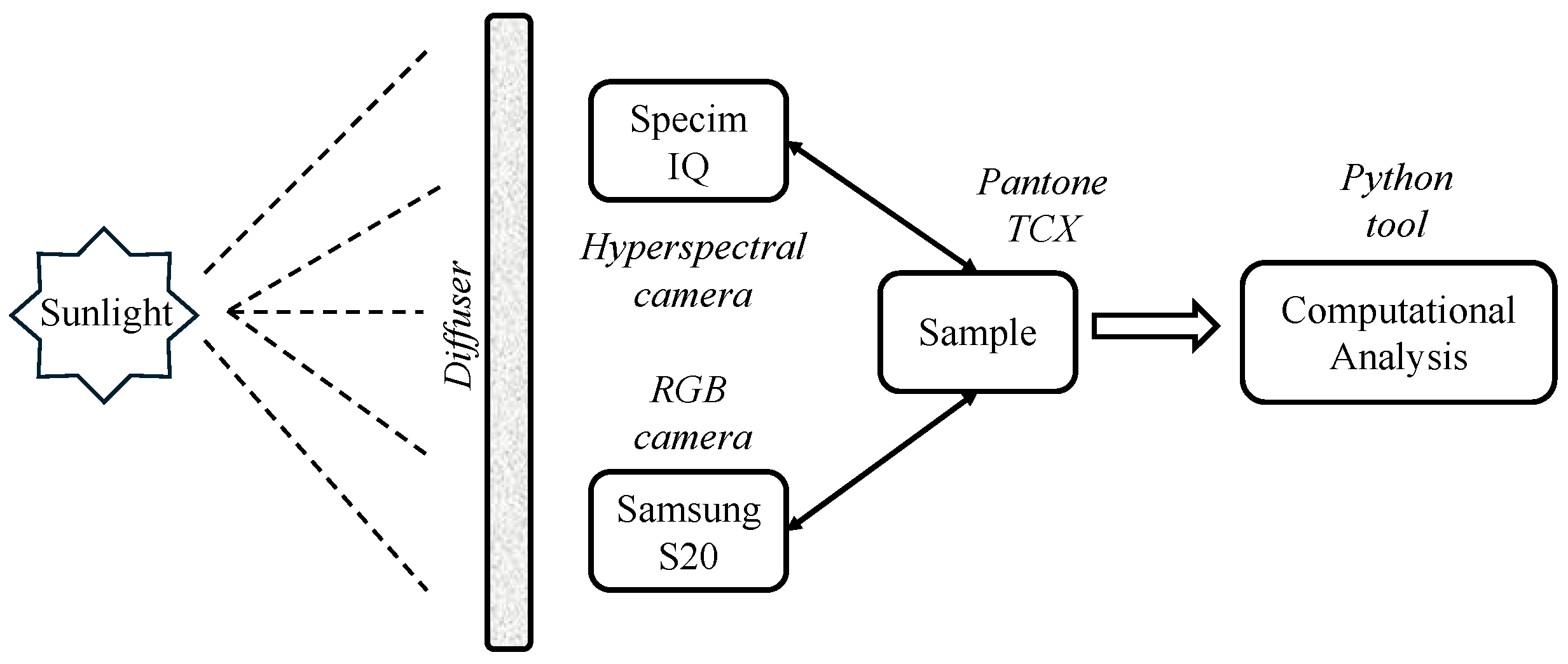

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.1.1. Hyperspectral and Digital Cameras

2.1.2. Pantone TCX Samples

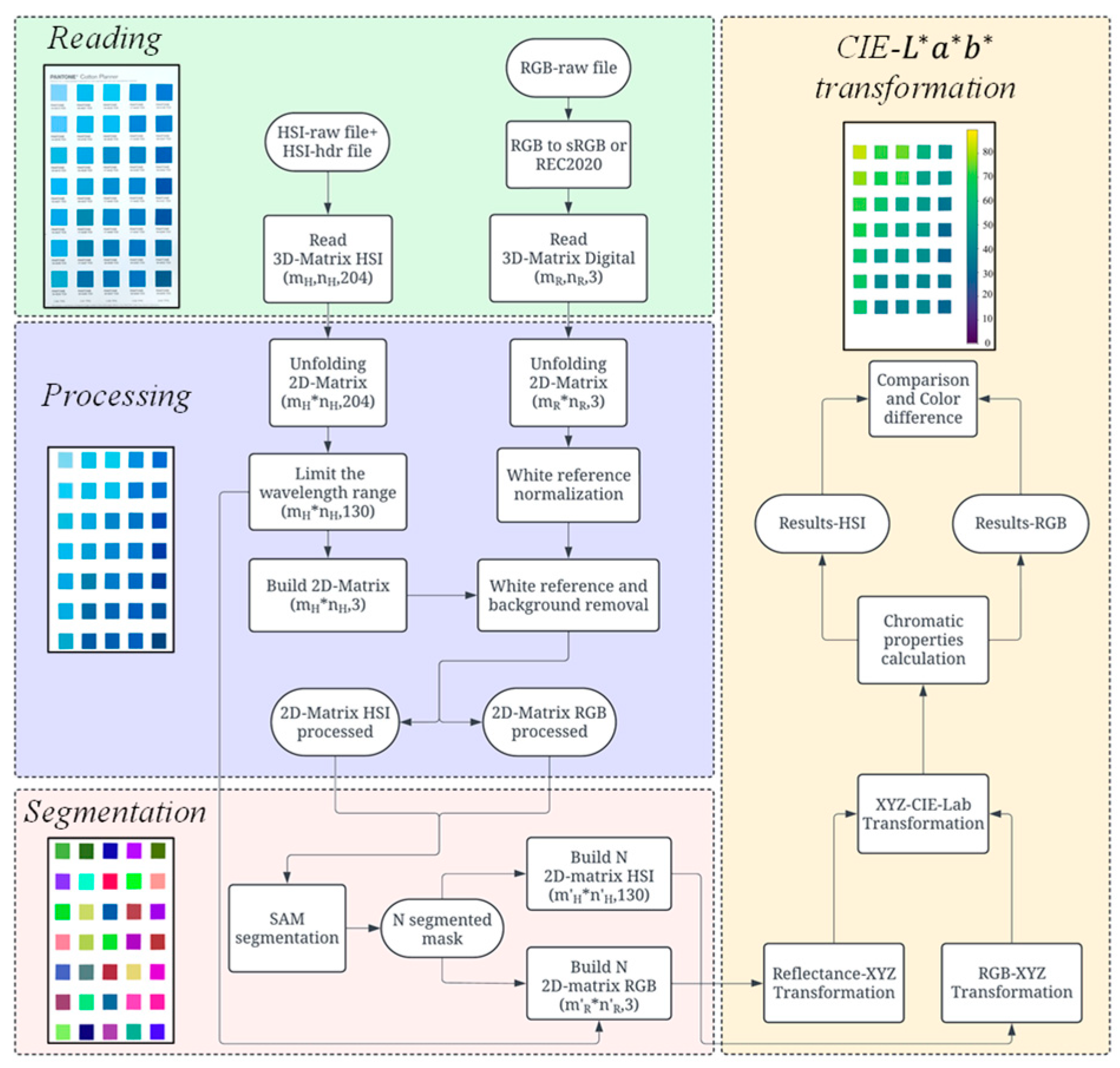

2.2. Computational Process

2.2.1. Image Reading

2.2.2. Processing

2.2.3. Segmentation

2.2.4. CIE-*** Transformation

3. Results

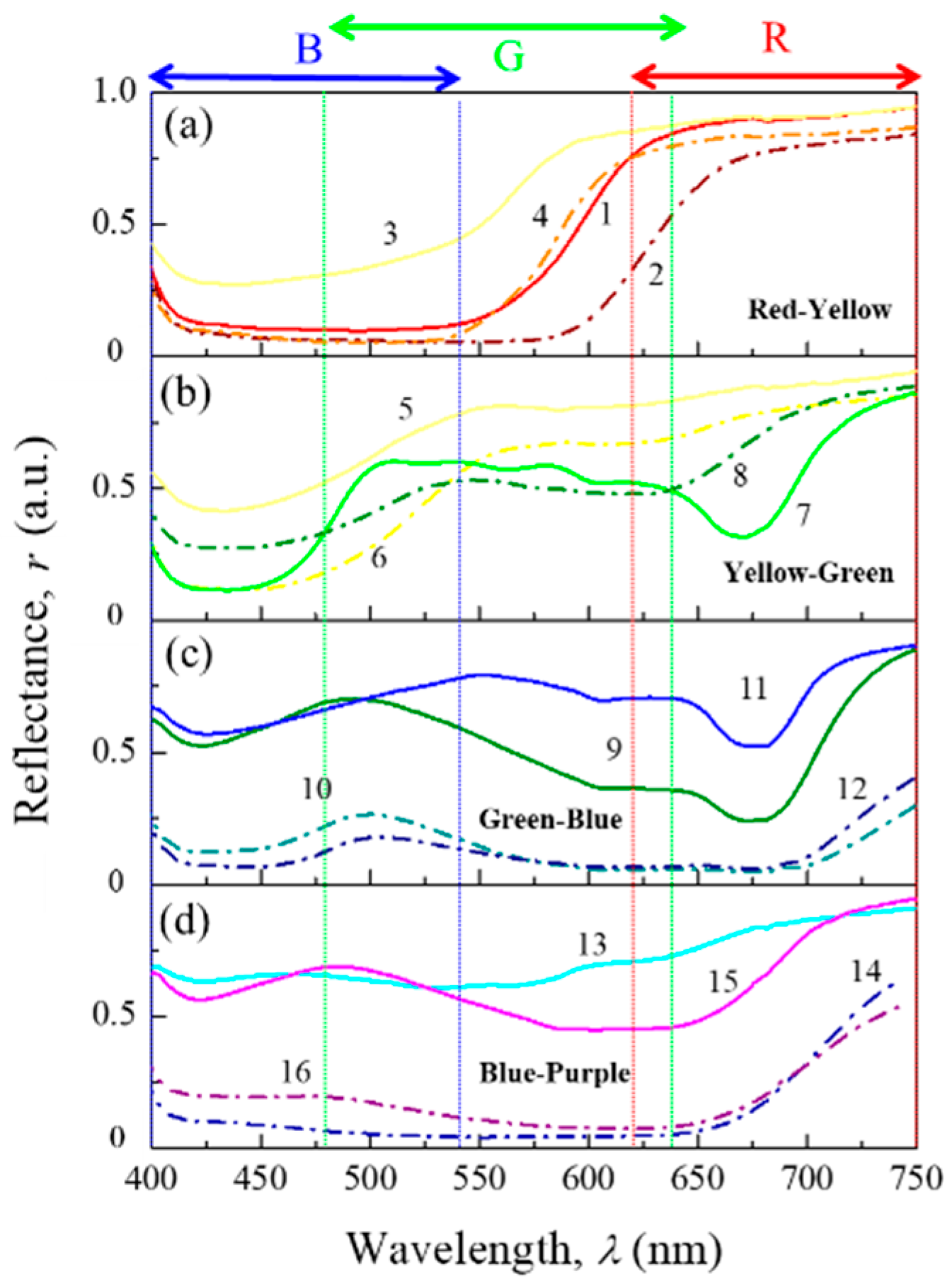

2.2. Optical Characterization

3.2. Color Properties from Hyperspectral Images (HSI)

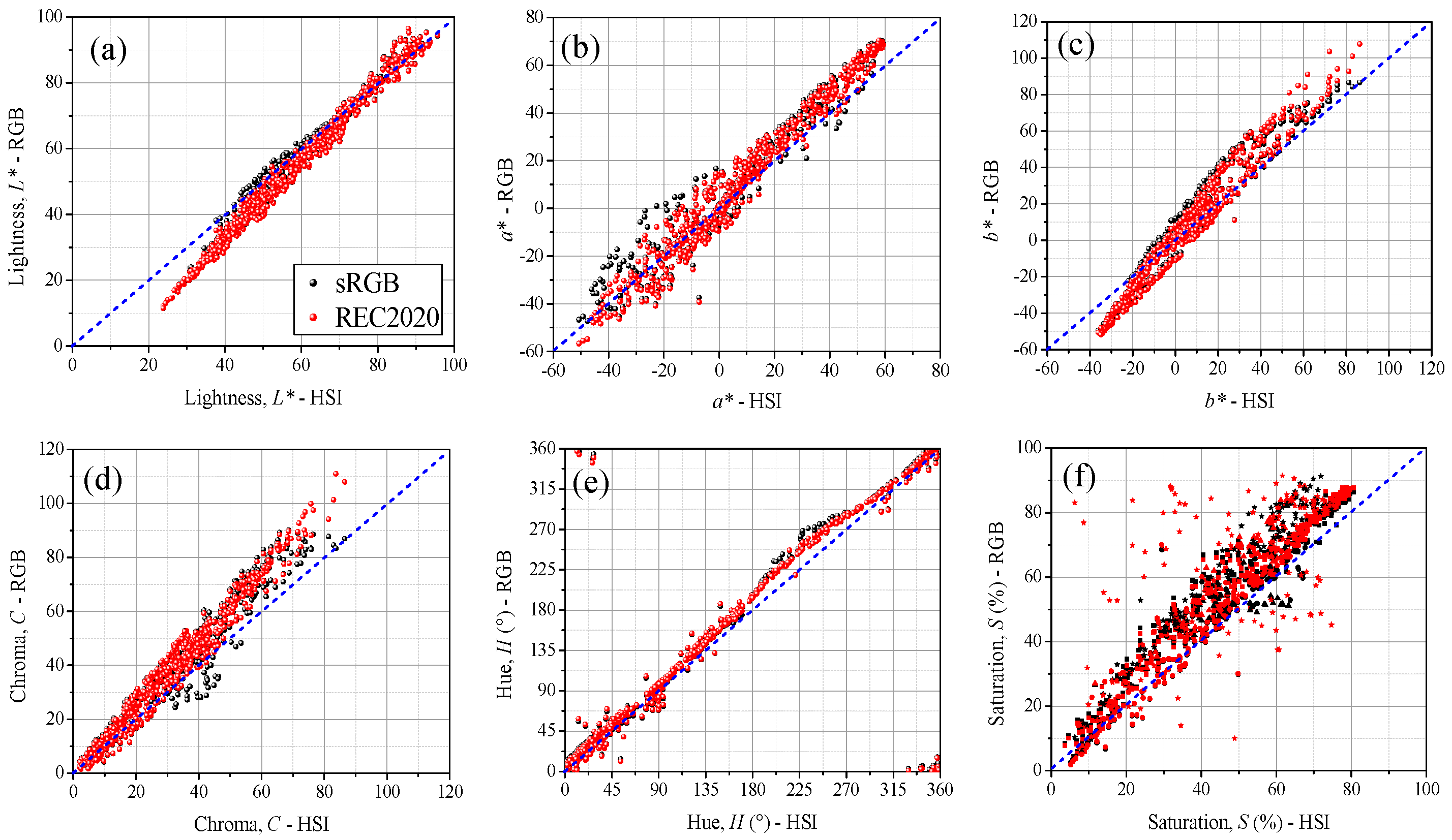

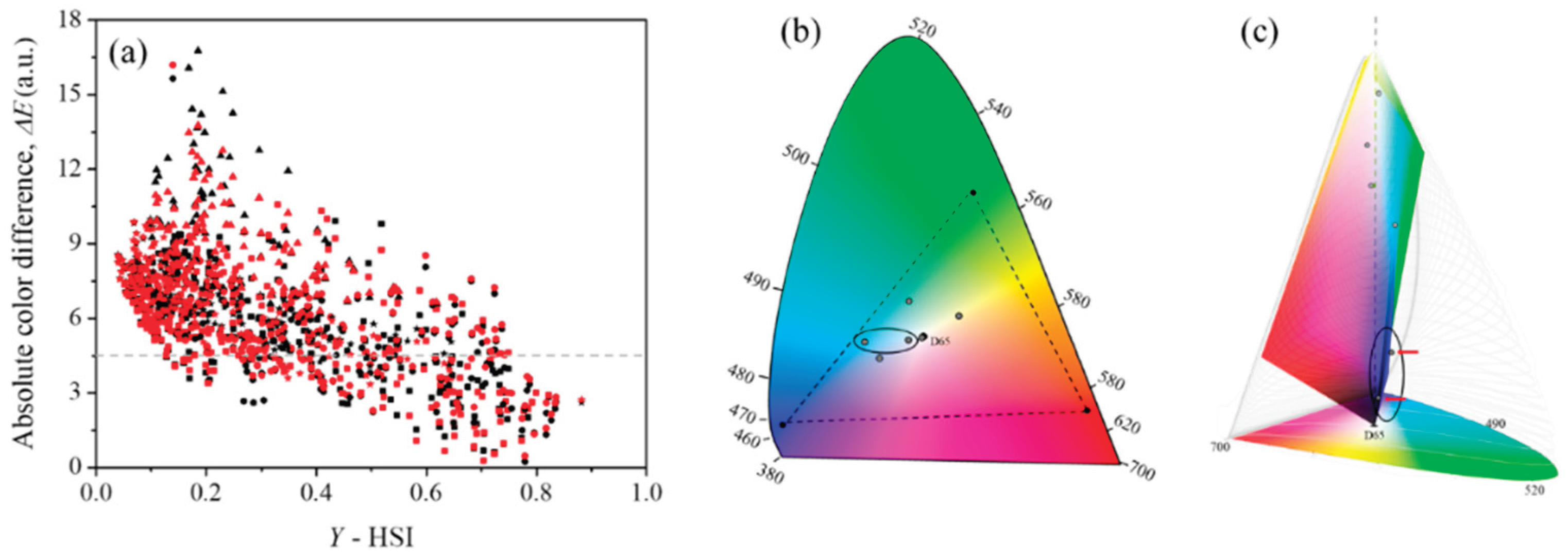

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Color Properties from HSI and RGB Images

4. Discussion

4.1. Color Differences Between HSI and RGB Images

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HSI | Hyperspectral imaging |

| Q | Quadrant |

| RPD | Ratio to performance deviation |

| CIE | Commission Internationale d'Eclairage |

| L | Lightness |

| C | Chroma |

| H | Hue |

References

- Huang, M.; Liu, H.; Cui, G.; Luo, M.R. Testing Uniform Colour Spaces and Colour-difference Formulae Using Printed Samples. Color Res Appl 2012, 37, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, E.D.; Wilber, D.C. A Comparison of Constant Stimuli and Gray-scale Methods of Color Difference Scaling. Color Res Appl 2003, 28, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernet, S.; Dinet, E.; Trémeau, A.; Colantoni, P. Experimental Protocol for Color Difference Evaluation Under Stabilized LED Light. J Imaging 2024, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.E. Scenes and Lighting. In; 2019; pp. 39–66.

- Ohta, N.; Robertson, A.R. Colorimetry: Fundamentals and Applications; 2006.

- Wu, D.; Sun, D.-W. Colour Measurements by Computer Vision for Food Quality Control – A Review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2013, 29, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.L.; Peng, P.; Yiu, K.F.C. Fabric Defect Detection Using Morphological Filters. Image Vis Comput 2009, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiffin, J.; Kuhn, H.S. Color Discrimination in Industry. Archives of Ophthalmology 1942, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugonik, B.; Golob, M.; Marhl, M.; Dugonik, A. Optimizing Digital Image Quality for Improved Skin Cancer Detection. J Imaging 2025, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalkhali, V.; Lee, H.; Nguyen, J.; Zamora-Erazo, S.; Ragin, C.; Aphale, A.; Bellacosa, A.; Monk, E.P.; Biswas, S.K. MST-AI: Skin Color Estimation in Skin Cancer Datasets. J Imaging 2025, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liming, X.; Yanchao, Z. Automated Strawberry Grading System Based on Image Processing. Comput Electron Agric 2010, 71, S32–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pulido, F.J.; Gordillo, B.; Heredia, F.J.; González-Miret, M.L. CIELAB – Spectral Image MATCHING: An App for Merging Colorimetric and Spectral Images for Grapes and Derivatives. Food Control 2021, 125, 108038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, S. A Color-Based Multispectral Imaging Approach for a Human Detection Camera. J Imaging 2025, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liming, X.; Yanchao, Z. Automated Strawberry Grading System Based on Image Processing. Comput Electron Agric 2010, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, H.I.; Dülger, L.C.; Topalbekiroǧlu, M. Development of a Machine Vision System: Real-Time Fabric Defect Detection and Classification with Neural Networks. Journal of the Textile Institute 2014, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, S.; Kao, C.-Y.; Su, S.-L.; Jeffrey Kuo, C.-F. Development of a Real-Time Machine Vision System for Functional Textile Fabric Defect Detection Using a Deep YOLOv4 Model. Textile Research Journal 2022, 92, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kaur, D.; Gupta, A.; Jaiswal, V. Application and Analysis of Hyperspectal Imaging. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing,Computing and Control; 2019; Vol. 2019-October.

- Calin, M.A.; Parasca, S.V.; Savastru, D.; Manea, D. Hyperspectral Imaging in the Medical Field: Present and Future. Appl Spectrosc Rev 2014, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-P.; Karmakar, R.; Mukundan, A.; Tsao, Y.-M.; Sung, T.-C.; Lu, C.-L.; Wang, H.-C. Spectrum Aided Vision Enhancer Enhances Mucosal Visualization by Hyperspectral Imaging in Capsule Endoscopy. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 22243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teke, M.; Deveci, H.S.; Haliloglu, O.; Gurbuz, S.Z.; Sakarya, U. A Short Survey of Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Applications in Agriculture. In Proceedings of the RAST 2013 - Proceedings of 6th International Conference on Recent Advances in Space Technologies; 2013.

- Liu, F.; Xiao, Z. Disease Spots Identification of Potato Leaves in Hyperspectral Based on Locally Adaptive 1D-CNN. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of 2020 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Applications, ICAICA 2020; 2020.

- Carroll, M.W.; Glaser, J.A.; Hellmich, R.L.; Hunt, T.E.; Sappington, T.W.; Calvin, D.; Copenhaver, K.; Fridgen, J. Use of Spectral Vegetation Indices Derived from Airborne Hyperspectral Imagery for Detection of European Corn Borer Infestation in Iowa Corn Plots. J Econ Entomol 2008, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medus, L.D.; Saban, M.; Francés-Víllora, J. V.; Bataller-Mompeán, M.; Rosado-Muñoz, A. Hyperspectral Image Classification Using CNN: Application to Industrial Food Packaging. Food Control 2021, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Khan, H.S.; Yousaf, A.; Khurshid, K.; Abbas, A. Modern Trends in Hyperspectral Image Analysis: A Review. IEEE Access 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, D.C. Toward Detecting Crop Diseases and Pest by Supervised Learning. Ingenieria y Universidad 2015, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine Learning: Trends, Perspectives, and Prospects. Science (1979) 2015, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signoroni, A.; Savardi, M.; Baronio, A.; Benini, S. Deep Learning Meets Hyperspectral Image Analysis: A Multidisciplinary Review. J Imaging 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.J.; Archibald, J.K.; Chang, Y.C.; Greco, C.R. Robust Color Space Conversion and Color Distribution Analysis Techniques for Date Maturity Evaluation. J Food Eng 2008, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Rincón, J.A.; Palencia, M.; Combatt, E.M. Separation of Optical Properties for Multicomponent Samples and Determination of Spectral Similarity Indices Based on FEDS0 Algorithm. Mater Today Commun 2022, 33, 104528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Rincón, J.A.; Palencia, M.; Combatt, E.M. Determining Relative Values of PH, CECe, and OC in Agricultural Soils Using Functional Enhanced Derivative Spectroscopy (FEDS0) Method in the Mid-Infrared Region. Infrared Phys Technol 2023, 133, 104864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishidate, I.; Kawauchi, S.; Sato, S.; Sato, M.; Aizu, Y.; Kokubo, Y. RGB Camera-Based Functional Imaging of in Vivo Biological Tissues.; 2018.

- Su, W.H. Advanced Machine Learning in Point Spectroscopy, Rgb-and Hyperspectral-Imaging for Automatic Discriminations of Crops and Weeds: A Review. Smart Cities 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Su, R.; Fu, Q.; Ren, W.; Heide, F.; Nie, Y. A Survey on Computational Spectral Reconstruction Methods from RGB to Hyperspectral Imaging. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connah, D.; Westland, S.; Thomson, M.G.A. Recovering Spectral Information Using Digital Camera Systems. Coloration Technology 2001, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eem, J.K.; Shin, H.D.; Park, S.O. Reconstruction of Surface Spectral Reflectances Using Characteristic Vectors of Munsell Colors. In Proceedings of the Final Program and Proceedings - IS and T/SID Color Imaging Conference; 1994.

- Kim, I.; Kim, M.S.; Chen, Y.R.; Kong, S.G. Detection of Skin Tumors on Chicken Carcasses Using Hyperspectral Fluorescence Imaging. Transactions of the American Society of Agricultural Engineers 2004, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.M.; Kim, M.S.; Tao, Y.; Lefcourt, A.; Chen, Y.R. Safety Inspection of Cantaloupes and Strawberries Using Multispectral Fluorescence Imaging Techniques. In Proceedings of the ASAE Annual International Meeting 2004; 2004.

- Elagamy, S.H.; Adly, L.; Abdel Hamid, M.A. Smartphone Based Colorimetric Approach for Quantitative Determination of Uric Acid Using Image J. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Fiore, A.; Reverberi, M.; Ricelli, A.; Pinzari, F.; Serranti, S.; Fabbri, A.A.; Bonifazi, G.; Fanelli, C. Early Detection of Toxigenic Fungi on Maize by Hyperspectral Imaging Analysis. Int J Food Microbiol 2010, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Wang, Z.; Ahmad, W.; Man, Z.; Duan, Y. Identification of Rice Storage Time Based on Colorimetric Sensor Array Combined Hyperspectral Imaging Technology. J Stored Prod Res 2020, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabakeris, T.; Poth, A.; Intreß, J.; Schmidt, U.; Geyer, M. Detection of Postharvest Quality Loss in Broccoli by Means of Non-Colorimetric Reflection Spectroscopy and Hyperspectral Imaging. Comput Electron Agric 2015, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Commission on Illumination Standard Colorimetry - Part 4: CIE 1976 L*a*b* Colour Space, Iso 11664-4:2008 2008.

- M. de Lasarte; M. Vilaseca; J. Pujol; M. Arjona; F. M. Martínez-Verdú; D. de Fez; V. Viqueira Development of a Perceptual Colorimeter Based on a Conventional CCD Camera with More than Three Color Channels. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 10th Congress of the International Color Association; May 2005; Vol. 1, pp. 1274–1250.

- Garrido-Novell, C.; Pérez-Marin, D.; Amigo, J.M.; Fernández-Novales, J.; Guerrero, J.E.; Garrido-Varo, A. Grading and Color Evolution of Apples Using RGB and Hyperspectral Imaging Vision Cameras. J Food Eng 2012, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Electrotechnical Commission Multimedia Systems and Equipment - Colour Measurement and Management - Part 2-1: Colour Management - Default RGB Colour Space - SRGB; 2000.

- Süsstrunk, S., B.R., & S.S. Standard RGB Color Spaces. . In Proceedings of the In Color and imaging conference (Vol. 7, pp. 127-134). ; Society of Imaging Science and Technology, 1999; pp. 127–134.

- Foster, D.H.; Amano, K. Hyperspectral Imaging in Color Vision Research: Tutorial. Journal of the Optical Society of America A 2019, 36, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behmann, J.; Acebron, K.; Emin, D.; Bennertz, S.; Matsubara, S.; Thomas, S.; Bohnenkamp, D.; Kuska, M.; Jussila, J.; Salo, H.; et al. Specim IQ: Evaluation of a New, Miniaturized Handheld Hyperspectral Camera and Its Application for Plant Phenotyping and Disease Detection. Sensors 2018, 18, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirhosseini, S.; Nasiri, A.F.; Khatami, F.; Mirzaei, A.; Aghamir, S.M.K.; Kolahdouz, M. A Digital Image Colorimetry System Based on Smart Devices for Immediate and Simultaneous Determination of Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soneira, R.M. Display Color Gamuts: NTSC to Rec.2020. Inf Disp (1975) 2016, 32, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, K.; Mery, D.; Pedreschi, F.; León, J. Color Measurement in L*a*b* Units from RGB Digital Images. Food Research International 2006, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhbanova, V.L. Research into Methods for Determining Colour Differences in the CIELAB Uniform Colour Space. Light & Engineering 2020, 53–59. [CrossRef]

- Hill, B.; Roger, Th.; Vorhagen, F.W. Comparative Analysis of the Quantization of Color Spaces on the Basis of the CIELAB Color-Difference Formula. ACM Trans Graph 1997, 16, 109–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misue, K.; Kitajima, H. Design Tool of Color Schemes on the CIELAB Space. In Proceedings of the 2016 20th International Conference Information Visualisation (IV); IEEE, July 2016; pp. 33–38.

- Gao, L.; Smith, R.T. Optical Hyperspectral Imaging in Microscopy and Spectroscopy - a Review of Data Acquisition. J Biophotonics 2015, 8, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaccheri, L.; Adinolfi, B.; Mencaglia, A.A.; Mignani, A.G. Smartphone-Enabled Colorimetry. Sensors 2023, 23, 5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, W.D. A Re-Determination of the Trichromatic Coefficients of the Spectral Colours. Transactions of the Optical Society 1929, 30, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guild, J. The Colorimetric Properties of the Spectrum. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical or Physical Character 1931, 230, 149–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrepaal, R.; Malegori, C.; Gowen, A. Tutorial: Time Series Hyperspectral Image Analysis. J Near Infrared Spectrosc 2016, 24, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernov, V.; Alander, J.; Bochko, V. Integer-Based Accurate Conversion between RGB and HSV Color Spaces. Computers & Electrical Engineering 2015, 46, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, P.; Rajini, V.; Rajkumar, R.I. Segmentation and Edge Detection of Color Images Using CIELAB Color Space and Edge Detectors. In Proceedings of the INTERACT-2010; IEEE, December 2010; pp. 393–397.

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.-Y.; et al. Segment Anything. 2023.

- Bonfatti Júnior, E.A.; Lengowski, E.C. Colorimetria Aplicada à Ciência e Tecnologia Da Madeira. Pesqui Florest Bras 2018, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autran, C.d.S.; Gonçalez, J.C. CARACTERIZAÇÃO COLORIMÉTRICA DAS MADEIRAS DE MUIRAPIRANGA (Brosimum RubescensTaub.) E DE SERINGUEIRA (Hevea Brasiliensis, Clone Tjir 16 Müll Arg.) VISANDO À UTILIZAÇÃO EM INTERIORES. Ciência Florestal 2006, 16, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, S. Reflectance Spectra Recovery from Tristimulus Values by Adaptive Estimation with Metameric Shape Correction. Journal of the Optical Society of America A 2010, 27, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, C. A Hybrid Adaptation Strategy for Reconstruction Reflectance Based on the given Tristimulus Values. Color Res Appl 2020, 45, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Qian, L.; Hu, G.; Li, X. Spectral Reflectance Recovery from Tristimulus Values under Multi-Illuminants. Journal of Spectroscopy 2019, 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Liao, N.; Li, Y.; Cheng, H. Improving Reflectance Reconstruction from Tristimulus Values by Adaptively Combining Colorimetric and Reflectance Similarities. Optical Engineering 2017, 56, 053104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Shen, X.; Liu, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhu, M. Reflectance Spectra Recovery from Tristimulus Values by Extraction of Color Feature Match. Opt Quantum Electron 2016, 48, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, J.; Kunkel, T.; Atkins, R.; Pytlarz, J.; Daly, S.; Schilling, A.; Eberhardt, B. Encoding Color Difference Signals for High Dynamic Range and Wide Gamut Imagery. Color and Imaging Conference 2015, 23, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, R.W.G.; Pointer, M.R. Measuring Colour; Wiley, 2011; ISBN 9781119975373.

- López, F.; Valiente, J.M.; Baldrich, R.; Vanrell, M. Fast Surface Grading Using Color Statistics in the CIE Lab Space. In; 2005; pp. 666–673.

- Pantone Pantone Connect. Available online: https://www.pantone.com/pantone-connect (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- MacAdam, D.L. Visual Sensitivities to Color Differences in Daylight*. J Opt Soc Am 1942, 32, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAdam, D.L. Maximum Visual Efficiency of Colored Materials. J Opt Soc Am 1935, 25, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawar, S.; Buddenbaum, H.; Hill, J.; Kozak, J. Modeling and Mapping of Soil Salinity with Reflectance Spectroscopy and Landsat Data Using Two Quantitative Methods (PLSR and MARS). Remote Sens (Basel) 2014, 6, 10813–10834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-W.; Laird, D.A.; Mausbach, M.J.; Hurburgh, C.R. Near-Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy–Principal Components Regression Analyses of Soil Properties. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2001, 65, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattner, M.; Bohn, D. Characterization of Print Quality in Terms of Colorimetric Aspects. In Printing on Polymers; Elsevier, 2016; pp. 329–345. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, A.R. Historical Development of CIE Recommended Color Difference Equations. Color Res Appl 1990, 15, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.R.; Rigg, B. BFD (l:C) Colour-difference Formula Part-1 Development of the Formula. Journal of the Society of Dyers and Colourists 1987, 103, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Fernández, F.J.; Vilaseca, M.; Perales, E.; Chorro, E.; Martínez-Verdú, F.M.; Fernández-Dorado, J.; Pujol, J. Validation of a Gonio-Hyperspectral Imaging System Based on Light-Emitting Diodes for the Spectral and Colorimetric Analysis of Automotive Coatings. Appl Opt 2017, 56, 7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravesen, J. The Metric of Colour Space. Graph Models 2015, 82, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Quadrant (N) |

* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | C | H | S | ||

|

Q1 (271) |

59.11 | 24.58 | 18.56 | 34.00 | 39.20 | 45.78 | |

| 55.72 | 16.62 | 11.85 | 27.61 | 33.93 | 46.59 | ||

| 27.02 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 1.93 | 0.22 | 3.63 | ||

| 93.15 | 59.51 | 86.45 | 86.55 | 89.85 | 80.60 | ||

| 1.35 | 2.81 | 2.02 | 2.38 | 1.92 | 2.37 | ||

|

Q2 (168) |

65.41 | -15.44 | 21.35 | 29.54 | 129.06 | 38.86 | |

| 65.88 | -13.18 | 15.39 | 26.67 | 129.85 | 38.48 | ||

| 31.07 | -50.69 | 0.31 | 3.50 | 90.14 | 5.20 | ||

| 93.73 | -0.02 | 81.20 | 81.35 | 179.39 | 68.36 | ||

| 1.96 | 1.10 | 1.45 | 1.35 | 2.06 | 2.85 | ||

|

Q3 (126) |

56.70 | -19.39 | -19.73 | 31.27 | 226.67 | 48.52 | |

| 55.03 | -18.42 | -21.61 | 32.27 | 227.20 | 50.22 | ||

| 30.60 | -46.16 | -36.13 | 3.60 | 180.04 | 11.69 | ||

| 83.73 | -0.27 | -0.03 | 46.16 | 269.52 | 67.50 | ||

| 2.72 | 0.78 | 2.81 | 1.82 | 2.23 | 2.39 | ||

|

Q4 (135) |

49.79 | 22.18 | -12.28 | 28.08 | 325.64 | 47.53 | |

| 45.34 | 19.11 | -12.38 | 29.31 | 333.50 | 52.19 | ||

| 23.79 | 0.79 | -34.89 | 2.44 | 271.74 | 6.23 | ||

| 95.72 | 56.16 | -0.10 | 56.20 | 359.23 | 76.09 | ||

| 1.96 | 2.51 | 1.86 | 2.75 | 2.20 | 2.55 | ||

| * | * | * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPD | |||||||

| Q1 | sRGB | 4.67 | 3.07 | 1.65 | 2.15 | 1.17 | 2.42 |

| REC 2020 | 4.41 | 3.32 | 1.64 | 2.13 | 0.85 | 2.50 | |

| Q2 | sRGB | 3.22 | 1.94 | 4.36 | 3.18 | 2.45 | 2.31 |

| REC 2020 | 3.23 | 1.83 | 3.57 | 2.80 | 2.31 | 2.17 | |

| Q3 | sRGB | 1.75 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.83 | 1.20 | 0.93 |

| REC 2020 | 1.60 | 1.46 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 1.41 | 0.87 | |

| Q4 | sRGB | 2.53 | 1.34 | 1.64 | 1.17 | 0.37 | 1.30 |

| REC 2020 | 2.41 | 1.44 | 1.75 | 1.20 | 0.74 | 1.28 | |

| 50 | sRGB | 0.87 | 2.56 | 1.89 | 1.66 | 2.07 | 1.43 |

| REC 2020 | 0.83 | 2.77 | 2.08 | 1.74 | 2.29 | 1.44 | |

| 50 | sRGB | 3.48 | 3.38 | 2.85 | 2.08 | 3.61 | 2.44 |

| REC 2020 | 3.28 | 3.91 | 2.57 | 1.97 | 3.14 | 2.39 | |

| Samples | sRGB | REC 2020 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 5.68 | 2.03 | 1.68 | 1.35 | 5.57 | 2.03 | 1.89 | 1.38 |

| Q2 | 5.57 | 2.51 | 2.74 | 2.94 | 5.71 | 2.42 | 2.94 | 2.90 |

| Q3 | 9.69 | 2.33 | 3.05 | 2.60 | 10.52 | 2.28 | 3.82 | 2.89 |

| Q4 | 6.80 | 1.45 | 4.17 | 3.74 | 6.74 | 1.66 | 4.67 | 3.78 |

| 50 | 7.54 | 1.73 | 4.19 | 3.31 | 7.43 | 1.59 | 4.50 | 3.40 |

| 50 | 5.72 | 2.67 | 1.71 | 1.78 | 5.68 | 2.51 | 1.97 | 1.94 |

| 75 | 3.91 | 1.77 | 1.04 | 0.87 | 4.03 | 1.86 | 1.22 | 0.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).