Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Animals

2.3. Methods

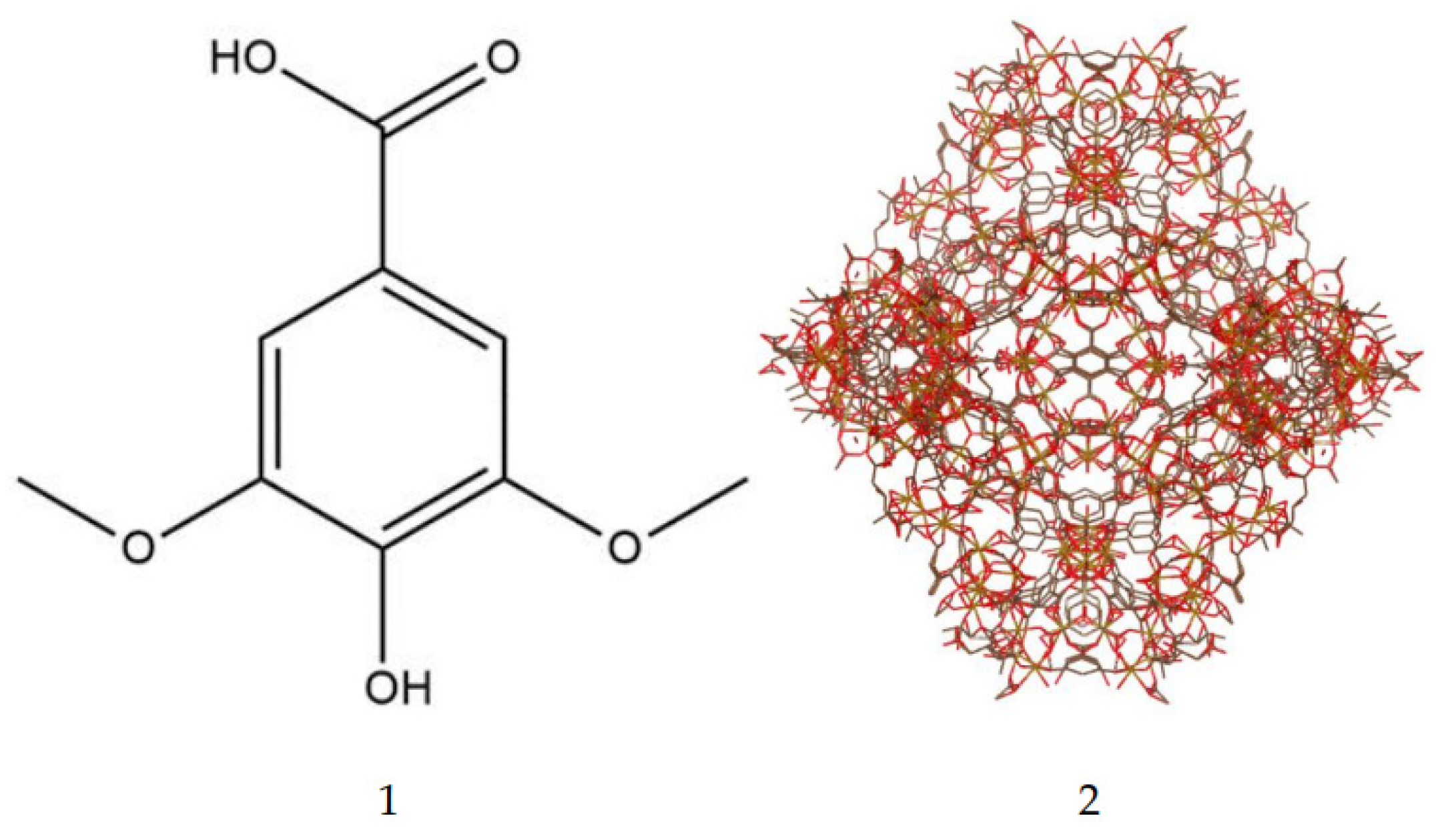

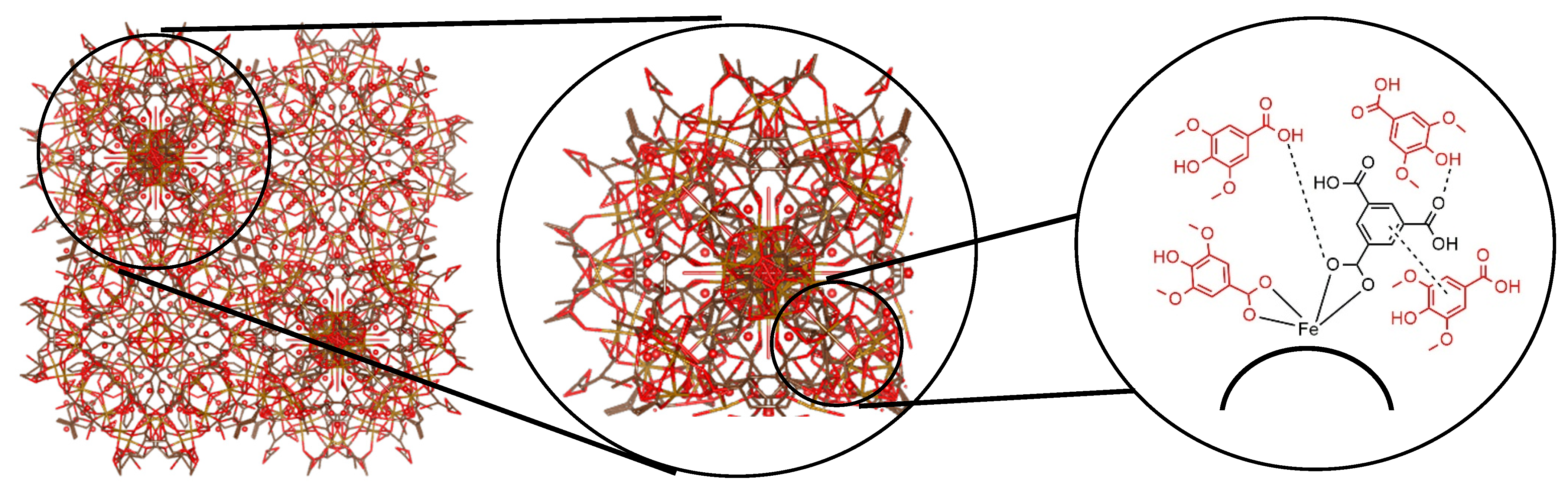

2.3.1. Synthesis of MIL-100

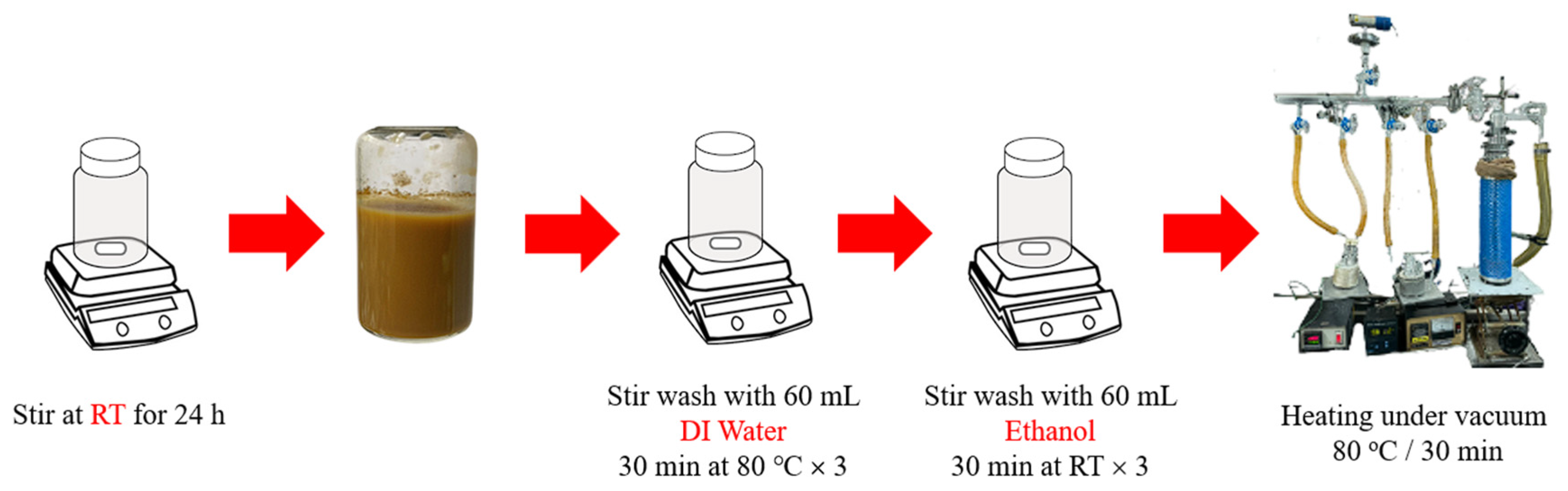

2.3.2. Syringic Acid Impregnation and Quantification

2.3.3. Characterization of SYA@MIL-100(Fe)

2.3.4. In Vitro Drug Release Study

2.3.5. Acute Oral Toxicity

2.3.6. Oral Bioavailability and Tissue Distribution

2.3.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

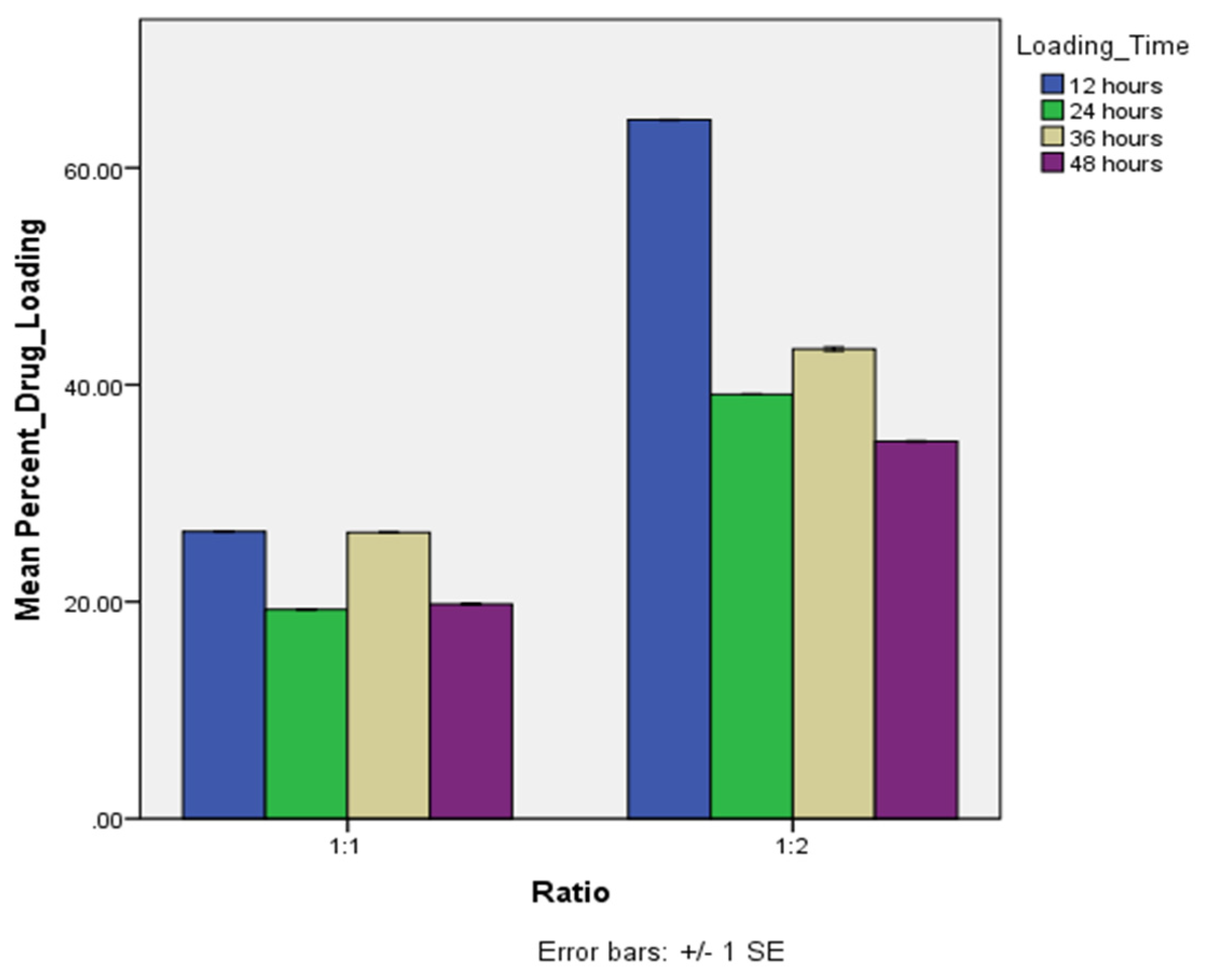

3.1. Syringic Acid Impregnation and Quantification

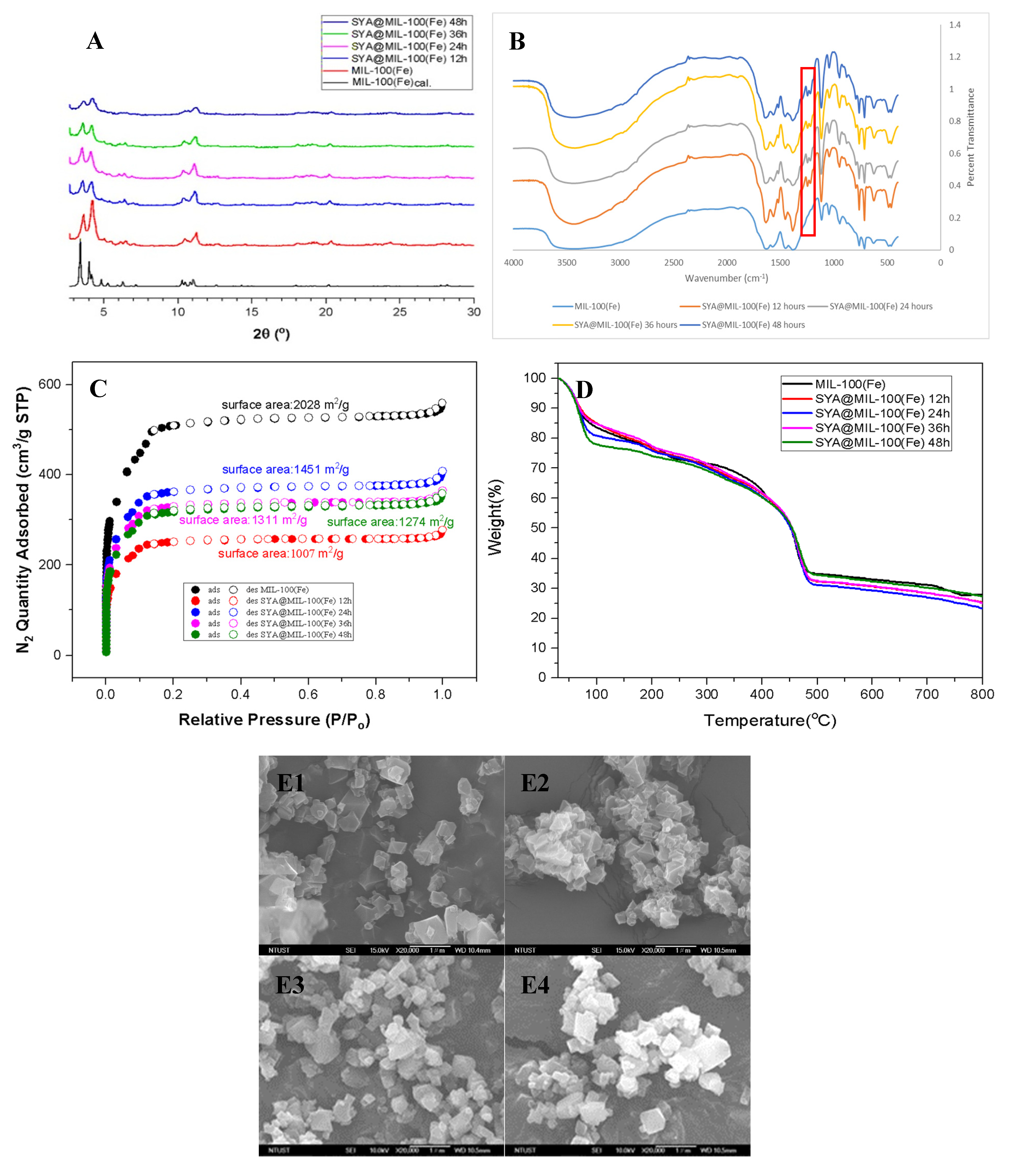

3.2. Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD)

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

3.4. Nitrogen Adsorption-Desorption

3.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis

3.6. Surface Morphology and Particle Size Analysis

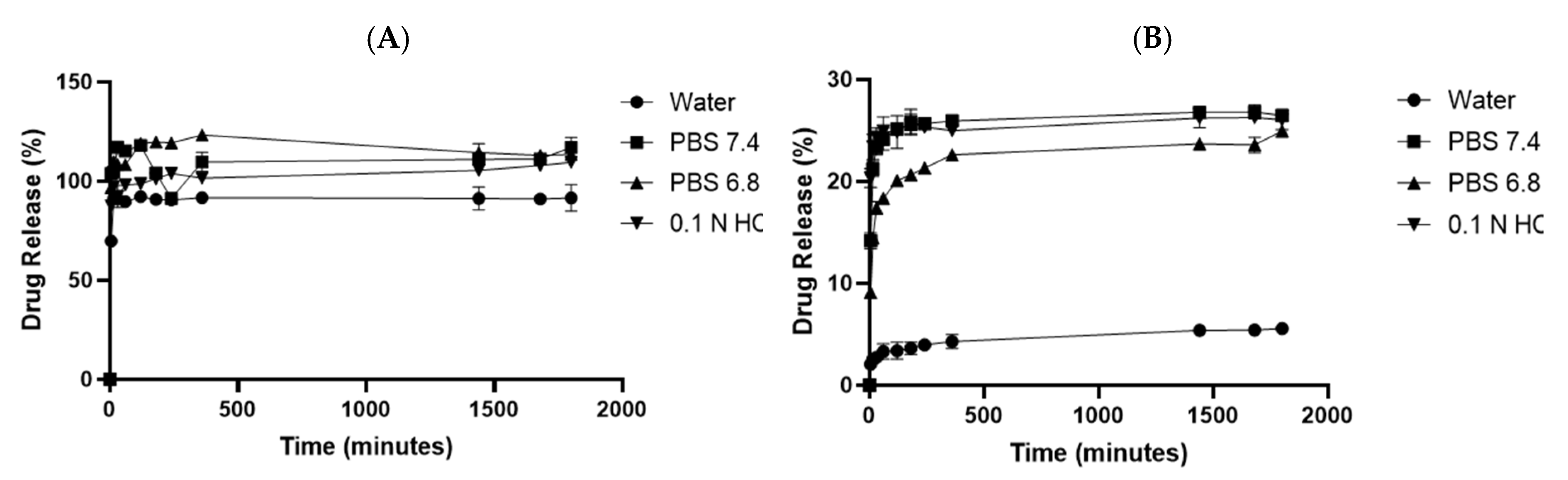

3.7. In Vitro Drug Release

3.8. Acute Oral Toxicity

3.9. Bioavailability

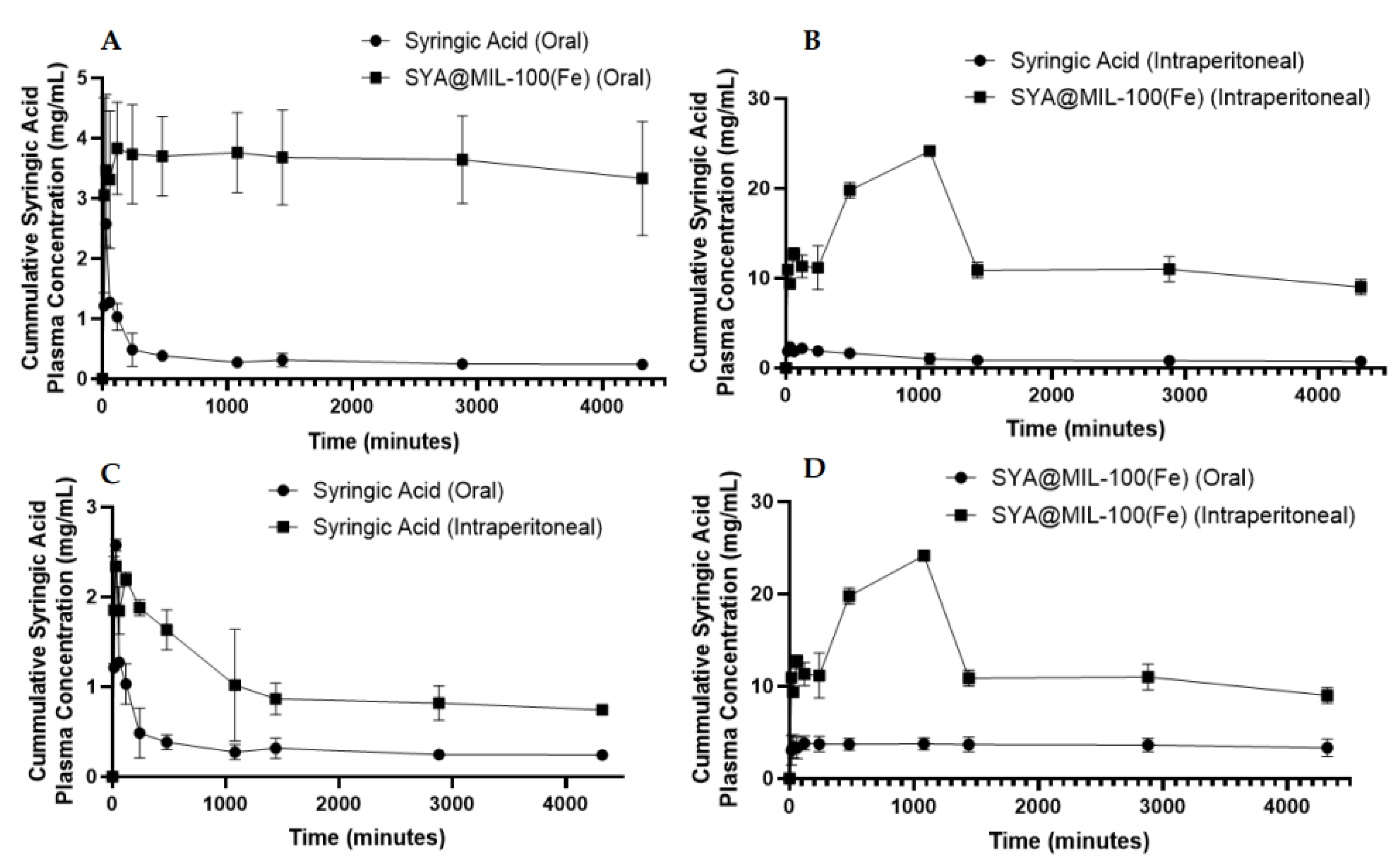

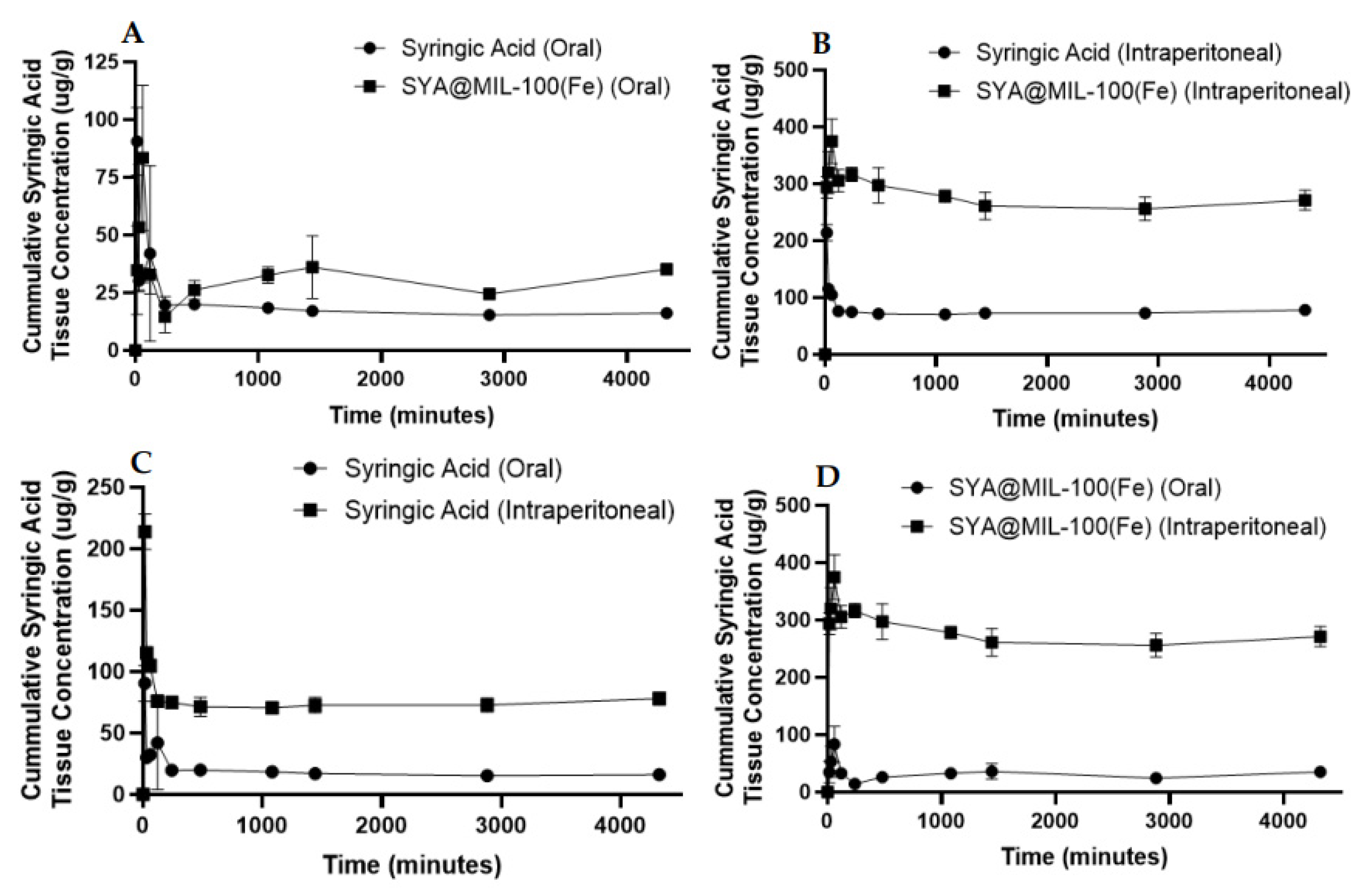

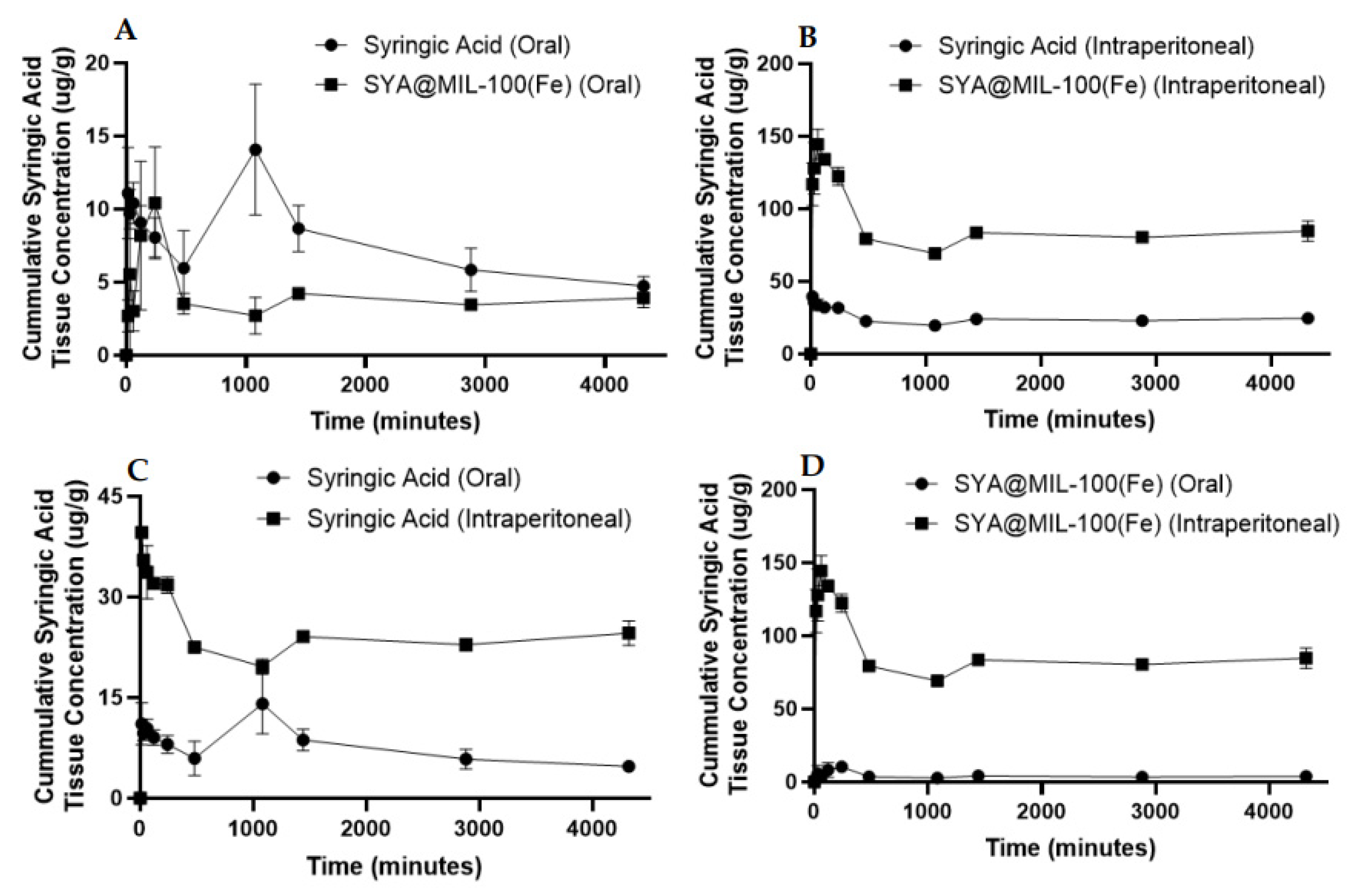

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MIL | Materials of Institut Lavoisier |

| MOF | Metal Organic Framework |

| AUC | Area under the Curve |

| Cmax | Maximum Concentration |

| Tmax | Time to reach maximum concentration |

| T1/2 | Half-life |

| SD | Sprague Dawley |

| SYA@MIL-100(Fe) | Syringic acid loaded MIL-100(Fe) |

References

- Molinari G. Natural Products in Drug Discovery: Present Status and Perspectives. In: Guzmán CA, Feuerstein GZ, editors. Pharm. Biotechnol., vol. 655, New York, NY: Springer New York; 2009, p. 13–27. [CrossRef]

- Gao S, Hu M. Bioavailability challenges associated with development of anti-cancer phenolics. Mini Rev Med Chem 2010;10:550–67. [CrossRef]

- Kumar N, Goel N. Phenolic acids: Natural versatile molecules with promising therapeutic applications. Biotechnol Rep 2019;24:e00370. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasulu C, Ramgopal M, Ramanjaneyulu G, Anuradha CM, Suresh Kumar C. Syringic acid (SA) ‒ A Review of Its Occurrence, Biosynthesis, Pharmacological and Industrial Importance. Biomed Pharmacother 2018;108:547–57. [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi T, Ono K, Murase A, Yamada M. Phenolic Compounds Prevent Alzheimer’s Pathology through Different Effects on the Amyloid-β Aggregation Pathway. Am J Pathol 2009;175:2557–65. [CrossRef]

- Estevinho L, Pereira AP, Moreira L, Dias LG, Pereira E. Antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of phenolic compounds extracts of Northeast Portugal honey. Food Chem Toxicol 2008;46:3774–9. [CrossRef]

- Chirinos R, Betalleluz-Pallardel I, Huamán A, Arbizu C, Pedreschi R, Campos D. HPLC-DAD characterisation of phenolic compounds from Andean oca (Oxalis tuberosa Mol.) tubers and their contribution to the antioxidant capacity. Food Chem 2009;113:1243–51. [CrossRef]

- Kumar N, Pruthi V. Potential applications of ferulic acid from natural sources. Biotechnol Rep 2014;4:86–93. [CrossRef]

- Pereira D, Valentão P, Pereira J, Andrade P. Phenolics: From Chemistry to Biology. Molecules 2009;14:2202–11. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Palencia LA, Mertens-Talcott S, Talcott ST. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant Properties, and Thermal Stability of a Phytochemical Enriched Oil from Açai ( Euterpe oleracea Mart.). J Agric Food Chem 2008;56:4631–6. [CrossRef]

- Pezzuto JM. Grapes and Human Health: A Perspective. J Agric Food Chem 2008;56:6777–84. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Sun C, Li W, Adu-Frimpong M, Wang Q, Yu J, et al. Preparation and Characterization of Syringic Acid–Loaded TPGS Liposome with Enhanced Oral Bioavailability and In Vivo Antioxidant Efficiency. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019;20:98. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Guo X, Lü Z, Xie W. Study on the pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of syringic acid in rabbits. Zhong Yao Cai Zhongyaocai J Chin Med Mater 2003;26:798–801.

- Kumar S, Dilbaghi N, Rani R, Bhanjana G, Umar A. Novel Approaches for Enhancement of Drug Bioavailability. Rev Adv Sci Eng 2013;2:133–54. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves C, Pereira P, Gama M. Self-Assembled Hydrogel Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery Applications. Materials 2010;3:1420–60. [CrossRef]

- Sayed E, Haj-Ahmad R, Ruparelia K, Arshad MS, Chang M-W, Ahmad Z. Porous Inorganic Drug Delivery Systems—a Review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017;18:1507–25. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Pan J, Ma Y, Qiu F, Niu X, Zhang T, et al. Three-in-one strategy for selective adsorption and effective separation of cis -diol containing luteolin from peanut shell coarse extract using PU/GO/BA-MOF composite. Chem Eng J 2016;306:655–66. [CrossRef]

- He S, Wu L, Li X, Sun H, Xiong T, Liu J, et al. Metal-organic frameworks for advanced drug delivery. Acta Pharm Sin B 2021;11:2362–95. [CrossRef]

- Abánades Lázaro I, Abánades Lázaro S, Forgan RS. Enhancing anticancer cytotoxicity through bimodal drug delivery from ultrasmall Zr MOF nanoparticles. Chem Commun 2018;54:2792–5. [CrossRef]

- Bag PP, Wang D, Chen Z, Cao R. Outstanding drug loading capacity by water stable microporous MOF: a potential drug carrier. Chem Commun 2016;52:3669–72. [CrossRef]

- Cunha D, Ben Yahia M, Hall S, Miller SR, Chevreau H, Elkaïm E, et al. Rationale of Drug Encapsulation and Release from Biocompatible Porous Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem Mater 2013;25:2767–76. [CrossRef]

- Gao H, Zhang Y, Chi B, Lin C, Tian F, Xu M, et al. Synthesis of ‘dual-key-and-lock’ drug carriers for imaging and improved drug release. Nanotechnology 2020;31:445102. [CrossRef]

- He C, Lu K, Liu D, Lin W. Nanoscale Metal–Organic Frameworks for the Co-Delivery of Cisplatin and Pooled siRNAs to Enhance Therapeutic Efficacy in Drug-Resistant Ovarian Cancer Cells. J Am Chem Soc 2014;136:5181–4. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Zhang W, Guo T, Zhang G, Qin W, Zhang L, et al. Drug nanoclusters formed in confined nano-cages of CD-MOF: dramatic enhancement of solubility and bioavailability of azilsartan. Acta Pharm Sin B 2019;9:97–106. [CrossRef]

- Horcajada P, Serre C, Maurin G, Ramsahye NA, Balas F, Vallet-Regí M, et al. Flexible Porous Metal-Organic Frameworks for a Controlled Drug Delivery. J Am Chem Soc 2008;130:6774–80. [CrossRef]

- Horcajada P, Chalati T, Serre C, Gillet B, Sebrie C, Baati T, et al. Porous metal–organic-framework nanoscale carriers as a potential platform for drug delivery and imaging. Nat Mater 2010;9:172–8. [CrossRef]

- Hu X, Wang C, Wang L, Liu Z, Wu L, Zhang G, et al. Nanoporous CD-MOF particles with uniform and inhalable size for pulmonary delivery of budesonide. Int J Pharm 2019;564:153–61. [CrossRef]

- Leng X, Dong X, Wang W, Sai N, Yang C, You L, et al. Biocompatible Fe-Based Micropore Metal-Organic Frameworks as Sustained-Release Anticancer Drug Carriers. Molecules 2018;23:2490. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Guo T, Lachmanski L, Manoli F, Menendez-Miranda M, Manet I, et al. Cyclodextrin-based metal-organic frameworks particles as efficient carriers for lansoprazole: Study of morphology and chemical composition of individual particles. Int J Pharm 2017;531:424–32. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Zhao S, Wang H, Peng Y, Tan Z, Tang B. Functional groups influence and mechanism research of UiO-66-type metal-organic frameworks for ketoprofen delivery. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2019;178:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Almaraz MT, Gref R, Agostoni V, Kreuz C, Clayette P, Serre C, et al. Towards improved HIV-microbicide activity through the co-encapsulation of NRTI drugs in biocompatible metal organic framework nanocarriers. J Mater Chem B 2017;5:8563–9. [CrossRef]

- Oh H, Li T, An J. Drug Release Properties of a Series of Adenine-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem - Eur J 2015;21:17010–5. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei M, Abbasi A, Varshochian R, Dinarvand R, Jeddi-Tehrani M. NanoMIL-100(Fe) containing docetaxel for breast cancer therapy. Artif Cells Nanomedicine Biotechnol 2018;46:1390–401. [CrossRef]

- Rojas S, Carmona FJ, Maldonado CR, Horcajada P, Hidalgo T, Serre C, et al. Nanoscaled Zinc Pyrazolate Metal–Organic Frameworks as Drug-Delivery Systems. Inorg Chem 2016;55:2650–63. [CrossRef]

- Simon MA, Anggraeni E, Soetaredjo FE, Santoso SP, Irawaty W, Thanh TC, et al. Hydrothermal Synthesize of HF-Free MIL-100(Fe) for Isoniazid-Drug Delivery. Sci Rep 2019;9:16907. [CrossRef]

- Sun C-Y, Qin C, Wang C-G, Su Z-M, Wang S, Wang X-L, et al. Chiral Nanoporous Metal-Organic Frameworks with High Porosity as Materials for Drug Delivery. Adv Mater 2011;23:5629–32. [CrossRef]

- Sun C-Y, Qin C, Wang X-L, Yang G-S, Shao K-Z, Lan Y-Q, et al. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 as efficient pH-sensitive drug delivery vehicle. Dalton Trans 2012;41:6906. [CrossRef]

- Sun K, Li L, Yu X, Liu L, Meng Q, Wang F, et al. Functionalization of mixed ligand metal-organic frameworks as the transport vehicles for drugs. J Colloid Interface Sci 2017;486:128–35. [CrossRef]

- Taherzade S, Soleimannejad J, Tarlani A. Application of Metal-Organic Framework Nano-MIL-100(Fe) for Sustainable Release of Doxycycline and Tetracycline. Nanomaterials 2017;7:215. [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Pashow KML, Della Rocca J, Xie Z, Tran S, Lin W. Postsynthetic Modifications of Iron-Carboxylate Nanoscale Metal−Organic Frameworks for Imaging and Drug Delivery. J Am Chem Soc 2009;131:14261–3. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Guo T, Wang C, He Y, Zhang X, Li G, et al. MOF Capacitates Cyclodextrin to Mega-Load Mode for High-Efficient Delivery of Valsartan. Pharm Res 2019;36:117. [CrossRef]

- Luo Y, Tan B, Liang X, Wang S, Gao X, Zhang Z, et al. Low-Temperature Rapid Synthesis and Performance of the MIL-100(Fe) Monolithic Adsorbent for Dehumidification. Ind Eng Chem Res 2020;59:7291–8. [CrossRef]

- Horcajada P, Surblé S, Serre C, Hong D-Y, Seo Y-K, Chang J-S, et al. Synthesis and catalytic properties of MIL-100(Fe), an iron( iii ) carboxylate with large pores. Chem Commun 2007:2820–2. [CrossRef]

- Singco B, Liu L-H, Chen Y-T, Shih Y-H, Huang H-Y, Lin C-H. Approaches to drug delivery: Confinement of aspirin in MIL-100(Fe) and aspirin in the de novo synthesis of metal–organic frameworks. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 2016;223:254–60. [CrossRef]

- Santos JH, Quimque MTJ, Macabeo APG, Corpuz MJ-AT, Wang Y-M, Lu T-T, et al. Enhanced Oral Bioavailability of the Pharmacologically Active Lignin Magnolol via Zr-Based Metal Organic Framework Impregnation. Pharmaceutics 2020;12:437. [CrossRef]

- Thommes M, Kaneko K, Neimark AV, Olivier JP, Rodriguez-Reinoso F, Rouquerol J, et al. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl Chem 2015;87:1051–69. [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi S, Stratz SA, Auxier JD, Hanson DE, Marsh ML, Hall HL. Characterization and thermogravimetric analysis of lanthanide hexafluoroacetylacetone chelates. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2017;311:617–26. [CrossRef]

- Chao M-Y, Zhang W-H, Lang J-P. Co2 and Co3 Mixed Cluster Secondary Building Unit Approach toward a Three-Dimensional Metal-Organic Framework with Permanent Porosity. Molecules 2018;23:755. [CrossRef]

- Bunaciu AA, Udriştioiu E gabriela, Aboul-Enein HY. X-Ray Diffraction: Instrumentation and Applications. Crit Rev Anal Chem 2015;45:289–99. [CrossRef]

- So PB, Chen H-T, Lin C-H. De novo synthesis and particle size control of iron metal organic framework for diclofenac drug delivery. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 2020;309:110495. [CrossRef]

- Danhier F, Magotteaux N, Ucakar B, Lecouturier N, Brewster M, Préat V. Novel self-assembling PEG-p-(CL-co-TMC) polymeric micelles as safe and effective delivery system for Paclitaxel. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2009;73:230–8. [CrossRef]

- Baishya H. Application of Mathematical Models in Drug Release Kinetics of Carbidopa and Levodopa ER Tablets. J Dev Drugs 2017;06. [CrossRef]

- Ding P, Shen H, Wang J, Ju J. Improved oral bioavailability of magnolol by using a binary mixed micelle system. Artif Cells Nanomedicine Biotechnol 2018;46:668–74. [CrossRef]

- Sun C, Li W, Zhang H, Adu-Frimpong M, Ma P, Zhu Y, et al. Improved Oral Bioavailability and Hypolipidemic Effect of Syringic Acid via a Self-microemulsifying Drug Delivery System. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021;22:45. [CrossRef]

- Al Haydar M, Abid HR, Sunderland B, Wang S. Metal organic frameworks as a drug delivery system for flurbiprofen. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017;11:2685–95. [CrossRef]

- Morris RE, Wheatley PS. Gas Storage in Nanoporous Materials. Angew Chem Int Ed 2008;47:4966–81. [CrossRef]

- Wittmann T, Tschense CBL, Zappe L, Koschnick C, Siegel R, Stäglich R, et al. Selective host–guest interactions in metal–organic frameworks via multiple hydrogen bond donor–acceptor recognition sites. J Mater Chem A 2019;7:10379–88. [CrossRef]

- Zhu X, Gu J, Wang Y, Li B, Li Y, Zhao W, et al. Inherent anchorages in UiO-66 nanoparticles for efficient capture of alendronate and its mediated release. Chem Commun 2014;50:8779–82. [CrossRef]

- Elharony NE, El Sayed IET, Al-Sehemi AG, Al-Ghamdi AA, Abou-Elyazed AS. Facile Synthesis of Iron-Based MOFs MIL-100(Fe) as Heterogeneous Catalyst in Kabachnick Reaction. Catalysts 2021;11:1451. [CrossRef]

- Isaeva VI, Kustov LM. The application of metal-organic frameworks in catalysis (Review). Pet Chem 2010;50:167–80. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Lachmanski L, Safi S, Sene S, Serre C, Grenèche JM, et al. New insights into the degradation mechanism of metal-organic frameworks drug carriers. Sci Rep 2017;7:13142. [CrossRef]

- Shano LB, Karthikeyan S, Kennedy LJ, Chinnathambi S, Pandian GN. MOFs for next-generation cancer therapeutics through a biophysical approach—a review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2024;12. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Zhang Z, She J, Wu D, et al. High Drug-Loading Nanomedicines for Tumor Chemo–Photo Combination Therapy: Advances and Perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2022;14:1735. [CrossRef]

- Bavnhøj CG, Knopp MM, Madsen CM, Löbmann K. The role interplay between mesoporous silica pore volume and surface area and their effect on drug loading capacity. Int J Pharm X 2019;1:100008. [CrossRef]

- Raza A, Wu W. Metal-organic frameworks in oral drug delivery. Asian J Pharm Sci 2024;19:100951. [CrossRef]

- Cui R, Zhao P, Yan Y, Bao G, Damirin A, Liu Z. Outstanding Drug-Loading/Release Capacity of Hollow Fe-Metal–Organic Framework-Based Microcapsules: A Potential Multifunctional Drug-Delivery Platform. Inorg Chem 2021;60:1664–71. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi M, Ayyoubzadeh SM, Ghorbani-Bidkorbeh F, Shahhosseini S, Dadashzadeh S, Asadian E, et al. An investigation of affecting factors on MOF characteristics for biomedical applications: A systematic review. Heliyon 2021;7:e06914. [CrossRef]

- Cretu C, Nicola R, Marinescu S-A, Picioruș E-M, Suba M, Duda-Seiman C, et al. Performance of Zr-Based Metal–Organic Framework Materials as In Vitro Systems for the Oral Delivery of Captopril and Ibuprofen. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:13887. [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Wang L, Hou J. Emerging microporous materials as novel templates for quantum dots. Microstructures 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Zheng L, Yang Y, Qian X, Fu T, Li X, et al. Metal–Organic Framework Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery in Biomedical Applications. Nano-Micro Lett 2020;12. [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Marqués M, Hidalgo T, Serre C, Horcajada P. Nanostructured metal–organic frameworks and their bio-related applications. Coord Chem Rev 2016;307:342–60. [CrossRef]

- Chobot V, Hadacek F. Iron and its complexation by phenolic cellular metabolites: From oxidative stress to chemical weapons. Plant Signal Behav 2010;5:4–8. [CrossRef]

- Singh K, Kumar A. Kinetics of complex formation of Fe(III) with syringic acid: Experimental and theoretical study. Food Chem 2018;265:96–100. [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Álvarez FG, Rojas-Mayorga CK, Mendoza-Castillo DI, Aguayo-Villarreal IA, Bonilla-Petriciolet A. Physicochemical Modeling of the Adsorption of Pharmaceuticals on MIL-100-Fe and MIL-101-Fe MOFs. Adsorpt Sci Technol 2022;2022:4482263. [CrossRef]

- Sun B, Zheng X, Zhang X, Zhang H, Jiang Y. Oxaliplatin-Loaded Mil-100(Fe) for Chemotherapy–Ferroptosis Combined Therapy for Gastric Cancer. ACS Omega 2024;9:16676–86. [CrossRef]

- Parsa F, Setoodehkhah M, Atyabi SM. Design, fabrication and characterization of a magnetite-chitosan coated iron-based metal–organic framework (Fe3O4@chitosan/MIL-100(Fe)) for efficient curcumin delivery as a magnetic nanocarrier. RSC Adv 2025;15:18518–34. [CrossRef]

- Tohidi S, Aghaie-Khafri M. Cyclophosphamide Loading and Controlled Release in MIL-100(Fe) as anAnti-breast Cancer Carrier: In vivo In vitro Study. Curr Drug Deliv 2024;21:283–94. [CrossRef]

- Le BT, La DD, Nguyen PTH. Ultrasonic-Assisted Fabrication of MIL-100(Fe) Metal–Organic Frameworks as a Carrier for the Controlled Delivery of the Chloroquine Drug. ACS Omega 2023;8:1262–70. [CrossRef]

- Lajevardi A, Hossaini Sadr M, Tavakkoli Yaraki M, Badiei A, Armaghan M. A pH-responsive and magnetic Fe3O4@silica@MIL-100(Fe)/β-CD nanocomposite as a drug nanocarrier: loading and release study of cephalexin. New J Chem 2018;42:9690–701. [CrossRef]

- Sucharitha P, Reddy R, Jahnavi I, Prakruthi H, Sruthi T, Gowd MRGB, et al. Design of Lamivudine Loaded Metal Organic Frameworks MIL 100 (Fe) by Microwave Assisted Chemistry. Indian J Pharm Educ Res 2024;58:s1083–92. [CrossRef]

- Al Haydar M, Abid HR, Sunderland B, Wang S. Multimetal organic frameworks as drug carriers: aceclofenac as a drug candidate. Drug Des Devel Ther 2018;Volume 13:23–35. [CrossRef]

- Lin Y, Yu R, Yin G, Chen Z, Lin H. Syringic acid delivered via mPEG-PLGA-PLL nanoparticles enhances peripheral nerve regeneration effect. Nanomed 2020;15:1487–99. [CrossRef]

- Shen S, Wu Y, Liu Y, Wu D. High drug-loading nanomedicines: progress, current status, and prospects. Int J Nanomedicine 2017;Volume 12:4085–109. [CrossRef]

- Rizvi SAA, Saleh AM. Applications of nanoparticle systems in drug delivery technology. Saudi Pharm J 2018;26:64–70. [CrossRef]

- Kohane DS. Microparticles and nanoparticles for drug delivery. Biotechnol Bioeng 2007;96:203–9. [CrossRef]

- Liu D, Pan H, He F, Wang X, Li J, Yang X, et al. Effect of particle size on oral absorption of carvedilol nanosuspensions: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Int J Nanomedicine 2015:6425. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J, Liao L, Zhu L, Zhang P, Guo K, Kong J, et al. Size-dependent cellular uptake efficiency, mechanism, and cytotoxicity of silica nanoparticles toward HeLa cells. Talanta 2013;107:408–15. [CrossRef]

- Linnane E, Haddad S, Melle F, Mei Z, Fairen-Jimenez D. The uptake of metal–organic frameworks: a journey into the cell. Chem Soc Rev 2022;51:6065–86. [CrossRef]

- Quijia CR, Lima C, Silva C, Alves RC, Frem R, Chorilli M. Application of MIL-100(Fe) in drug delivery and biomedicine. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2021;61:102217. [CrossRef]

- Neuer AL, Herrmann IK, Gogos A. Biochemical transformations of inorganic nanomedicines in buffers, cell cultures and organisms. Nanoscale 2023;15:18139–55. [CrossRef]

- Pirzadeh K, Ghoreyshi AA, Rohani S, Rahimnejad M. Strong Influence of Amine Grafting on MIL-101 (Cr) Metal–Organic Framework with Exceptional CO2/N2 Selectivity. Ind Eng Chem Res 2020;59:366–78. [CrossRef]

- Marson Armando RA, Abuçafy MP, Graminha AE, Silva RSD, Frem RCG. Ru-90@bio-MOF-1: A ruthenium(II) metallodrug occluded in porous Zn-based MOF as a strategy to develop anticancer agents. J Solid State Chem 2021;297:122081. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Peng Y, Xia X, Cao Z, Deng Y, Tang B. Sr/PTA Metal Organic Framework as A Drug Delivery System for Osteoarthritis Treatment. Sci Rep 2019;9:17570. [CrossRef]

- Lu L, Ma M, Gao C, Li H, Li L, Dong F, et al. Metal Organic Framework@Polysilsesequioxane Core/Shell-Structured Nanoplatform for Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2020;12:98. [CrossRef]

- Gharehdaghi Z, Naghib SM, Rahimi R, Bakhshi A, Kefayat A, Shamaeizadeh A, et al. Highly improved pH-Responsive anticancer drug delivery and T2-Weighted MRI imaging by magnetic MOF CuBTC-based nano/microcomposite. Front Mol Biosci 2023;10:1071376. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Xiong Y, Dong F. Cyclodextrin metal–organic framework@SiO2 nanocomposites for poorly soluble drug loading and release. RSC Adv 2024;14:31868–76. [CrossRef]

- Mirza AC, Panchal SS. Safety evaluation of syringic acid: subacute oral toxicity studies in Wistar rats. Heliyon 2019;5:e02129. [CrossRef]

- Chen G, Leng X, Luo J, You L, Qu C, Dong X, et al. In Vitro Toxicity Study of a Porous Iron(III) Metal‒Organic Framework. Molecules 2019;24:1211. [CrossRef]

- Tariq T, Bibi S, Ahmad Shah SS, Wattoo MA, Salem MA, El-Haroun H, et al. MIL materials: Synthesis strategies, morphology control, and biomedical application: A critical review. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2025;104:106532. [CrossRef]

- Itoh A, Isoda K, Kondoh M, Kawase M, Watari A, Kobayashi M, et al. Hepatoprotective Effect of Syringic Acid and Vanillic Acid on CCl4-Induced Liver Injury. Biol Pharm Bull 2010;33:983–7. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran V, Raja B. Protective Effects of Syringic Acid against Acetaminophen-Induced Hepatic Damage in Albino Rats. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 2010;21. [CrossRef]

- Ferah Okkay I, Okkay U, Gundogdu OL, Bayram C, Mendil AS, Ertugrul MS, et al. Syringic acid protects against thioacetamide-induced hepatic encephalopathy: Behavioral, biochemical, and molecular evidence. Neurosci Lett 2022;769:136385. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Zheng S, Li Y, Yang J, Mao X, Liu T, et al. Protective effects of syringic acid in nonalcoholic fatty liver in rats through regulation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2024;38. [CrossRef]

- Sherkhane B, Yerra VG, Sharma A, Kumar KA, Chayanika G, Kumar AV, et al. Nephroprotective potential of syringic acid in experimental diabetic nephropathy: Focus on oxidative stress and autophagy. Indian J Pharmacol 2023;55:34–42. [CrossRef]

- Zabad OM, Samra YA, Eissa LA. Syringic acid ameliorates experimental diabetic nephropathy in rats through its antiinflammatory, anti-oxidant and anti-fibrotic effects by suppressing Toll like receptor-4 pathway. Metabolism 2022;128:154966. [CrossRef]

- Mirza AC, Panchal SS, Allam AA, Othman SI, Satia M, Mandhane SN. Syringic Acid Ameliorates Cardiac, Hepatic, Renal and Neuronal Damage Induced by Chronic Hyperglycaemia in Wistar Rats: A Behavioural, Biochemical and Histological Analysis. Molecules 2022;27:6722. [CrossRef]

- Rashedinia M, Khoshnoud MJ, Fahlyan BK, Hashemi S-S, Alimohammadi M, Sabahi Z. Syringic Acid: A Potential Natural Compound for the Management of Renal Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Diabetic Rats. Curr Drug Discov Technol 2021;18:405–13. [CrossRef]

- Akram MU, Nesrullah M, Afaq S, Malik WMA, Ghafoor A, Ismail M, et al. An easy approach towards once a day sustained release dosage form using microporous Cu-MOFs as drug delivery vehicles. New J Chem 2024;48:11542–54. [CrossRef]

- Li L, Han S, Zhao S, Li X, Liu B, Liu Y. Chitosan modified metal-organic frameworks as a promising carrier for oral drug delivery. RSC Adv 2020;10:45130–8. [CrossRef]

- Kumar G, Kant A, Kumar M, Masram DT. Synthesis, characterizations and kinetic study of metal organic framework nanocomposite excipient used as extended release delivery vehicle for an antibiotic drug. Inorganica Chim Acta 2019;496:119036. [CrossRef]

- Sun C, Li W, Ma P, Li Y, Zhu Y, Zhang H, et al. Development of TPGS/F127/F68 mixed polymeric micelles: Enhanced oral bioavailability and hepatoprotection of syringic acid against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity. Food Chem Toxicol 2020;137:111126. [CrossRef]

- Coughlin JE, Pandey RK, Padmanabhan S, O’Loughlin KG, Marquis J, Green CE, et al. Metabolism, Pharmacokinetics, Tissue Distribution, and Stability Studies of the Prodrug Analog of an Anti-Hepatitis B Virus Dinucleoside Phosphorothioate. Drug Metab Dispos 2012;40:970–81. [CrossRef]

- Spizzirri UG, Aiello F, Carullo G, Facente A, Restuccia D. Nanotechnologies: An Innovative Tool to Release Natural Extracts with Antimicrobial Properties. Pharmaceutics 2021;13:230. [CrossRef]

- Lu J-L, Zeng X-S, Zhou X, Yang J-L, Ren L-L, Long X-Y, et al. Molecular Basis Underlying Hepatobiliary and Renal Excretion of Phenolic Acids of Salvia miltiorrhiza Roots (Danshen). Front Pharmacol 2022;13. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Li L, Ming G, Ma X, Liang C, Li Y, et al. Measurement of Pharmacokinetics and Tissue Distribution of Four Compounds from Nauclea officinalis in Rat Plasma and Tissues through HPLC-MS/MS. J Anal Methods Chem 2022;2022:1–18. [CrossRef]

| Test Compound | Biological Sample | Route | AUC0-72* | AUC0-∞* | Cmax** | Tmax*** | T1/2*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syringic Acid | Blood | Oral | 1,419 ± 142.15 | 1,460 ± 143.84 | 2.33 ± 0.19 | 66.78 ± 7.56‡ | 118.77 ± 30.76 |

| Intraperitoneal | 4,368.33 ± 489.25‡ | 5,400.84 ± 964.81‡ | 2.55 ± 0.04‡ | 55.97 ± 2.11 | 999.64 ± 410‡ | ||

| Liver | Oral | 32,000.33 ±3544.16‡ | 4,7401.91 ± 8,515.77‡ | 16.28 ±3.54 | 515.96 ± 4.44‡ | 2288.81 ± 812.66 | |

| Intraperitoneal | 102,784.67 ± 1510.75 | 166,522.15 ± 34,487.20 | 40.13 ± 0.56‡ | 24.70 ±0.21 | 1,852.40 ± 1,105.09 | ||

| Kidney | Oral | 77,103.33 ± 2,531.03‡ | 78,035.27 ± 2,458.81‡ | 105.36 ± 9.79 | 28.21 ± 0.33‡ | 37.56 ± 4.69‡ | |

| Intraperitoneal | 321,104.67 ± 11949.32 | 808,296.73 ± 429,472.17 | 218.21 ± 8.73‡ | 24.15 ± 0.96 | 4,805.81 ± 3271.08 | ||

| SYA@MIL-100(Fe) | Blood | Oral | 15,606 ± 1,936.03 | 131,269.97 ± 61,666.27 | 3.79 ± 0.43 | 549.02 ± 159.41 | 24,392.75 ± 10,593.37 |

| Intraperitoneal | 56,022.33 ± 2,240.13‡ | 206,758.55 ± 31,210.34‡ | 26.54 ± 0.55‡ | 1,236.64 ± 91.50‡ | 11,504.68 ± 2,306‡ | ||

| Liver | Oral | 17,309.33 ± 1,351.33‡ | 22,623.03 ± 2,085.19‡ | 11.42 ±2.30 | 385.57 ± 42.44‡ | 913.33 ± 223.58 | |

| Intraperitoneal | 363,982.67 ± 5,429.14 | 522,988.13 ± 44,624.56 | 150.25 ±6.65‡ | 111.01 ± 4.91 | 1,309.25 ± 359.93 | ||

| Kidney | Oral | 130,698 ± 7,713.74‡ | 144,112.76 ± 8494.44‡ | 89.27 ± 17.80 | 97.30 ± 9.65‡ | 265.21 ± 22.01‡ | |

| Intraperitoneal | 1,169,999.33 ± 36,457.71 | 2,971,634.10 ± 1,163,138.16 | 393.47 ± 14.44‡ | 118.08 ± 0.86 | 2,799.01 ± 1,717.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).