1. Introduction

In recent years, the adoption of digital technologies in physical education (PE) has accelerated significantly, with augmented reality (AR) drawing particular attention for its potential to offer immersive learning experiences [

1,

2]. Among various AR applications, AR climbing has been recognized as a technology that transforms conventional climbing activities into interactive PE experiences by integrating visual interfaces and sensor-based feedback mechanisms [

3,

4,

5]. Prior studies have reported that AR climbing may contribute positively to the physical and socio-emotional development of elementary school students [

6].

Despite the educational potential of such technologies, their effective implementation in school settings requires more than technical deployment. Scholars have emphasized that

teachers’ technology acceptance and

instructional competence are critical prerequisites for ensuring the stability and pedagogical value of digital tools in actual classrooms [

7,

8]. The indiscriminate influx of digital content into schools—often without sufficient pedagogical review—has led to unintended consequences such as budget inefficiencies, instructional disruption, and increased teacher stress [

9,

10,

11]. In this context, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) highlights that effective integration of digital tools in instruction is contingent upon teachers’ perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use (PEU), and behavioral intention (BI) [

12,

13]. These constructs reflect the extent to which teachers actively evaluate the educational legitimacy of a given technology.

However, bridging the gap between

technology acceptance and

instructional enactment necessitates a structured understanding of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK). Specifically, Technological Content Knowledge (TCK) enables teachers to align digital content with curriculum goals and subject matter, while Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK) supports the translation of that content into effective instructional strategies [

14,

15,

16]. From this perspective, an integrative TAM–TPACK approach is essential for resolving the discontinuity between acceptance and pedagogical implementation.

While prior studies have reported positive outcomes regarding learning effectiveness and motivational engagement associated with AR-based instruction [

3,

6,

17,

18,

19], few have examined how teachers conceptualize AR technologies (in terms of TAM) and how they translate those perceptions into structured pedagogical strategies (in terms of TPACK) [

20]. Although some design-based studies using virtual reality (VR) have been conducted [

21,

22], the unique affordances of AR—such as sensor-based feedback, gamification elements, and adjustable difficulty levels—remain underexplored in terms of their instructional applications.

Accordingly, this study aims to examine how elementary school teachers perceive and implement AR climbing content through an integrated lens of TAM and TPACK. Specifically, the research focuses on the following questions:

How do teachers perceive the usefulness (PU), ease of use (PEU), and behavioral intention (BI) of AR climbing content?

How are TCK and TPK reflected in the instructional implementation of AR climbing?

In what ways do TAM and TPACK interact during the instructional design process?

By connecting technology acceptance (TAM) with instructional design (TPACK), this study seeks to identify the structural elements of teacher-centered digital PE instruction, moving beyond simple technology adoption toward sustainable classroom integration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employed a qualitative case study approach to explore elementary school teachers’ instructional practices using AR climbing content in physical education (PE). The case study method is particularly suitable for in-depth analysis of phenomena situated in real-world contexts and was implemented following the procedures suggested by Creswell and Poth [

23]. Given the limited adoption of AR climbing in elementary PE, this study aimed to provide contextual insights into the instructional decisions of early adopters.

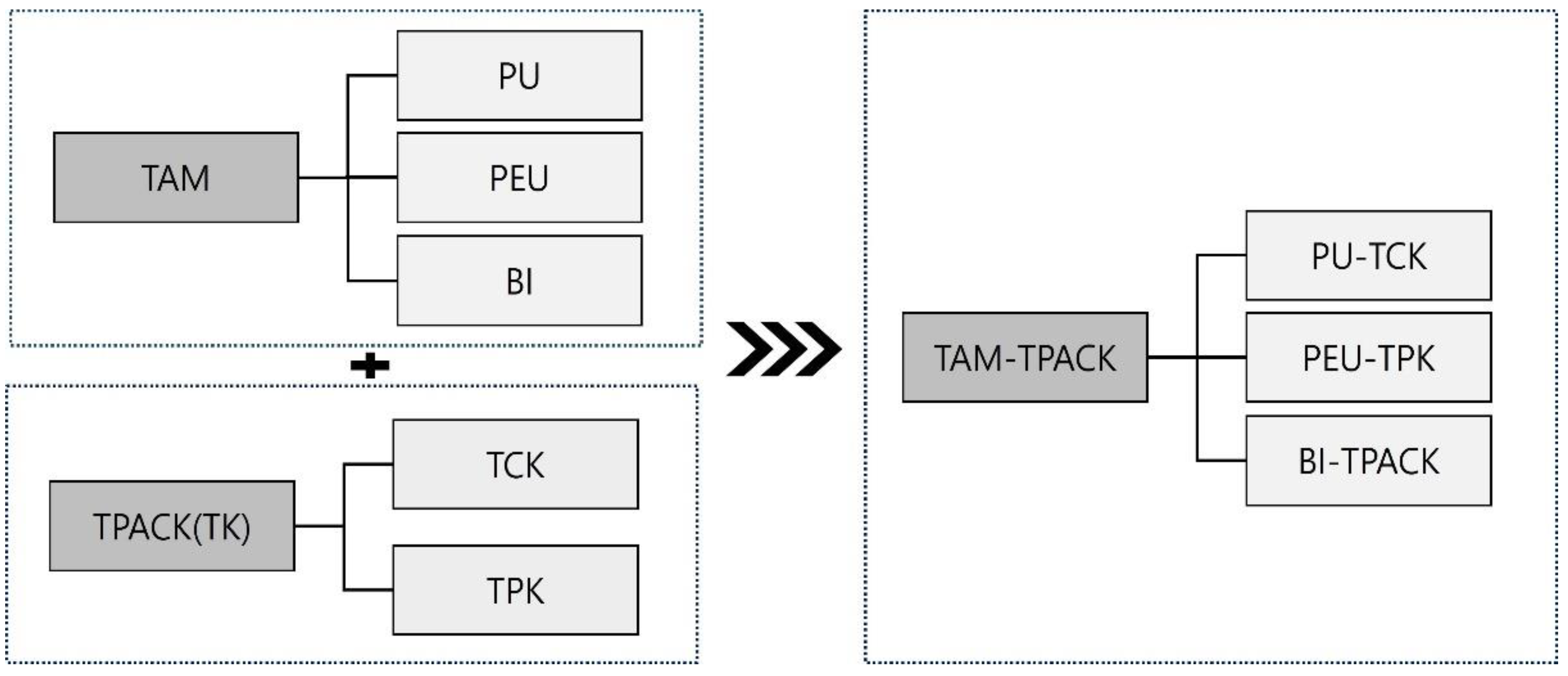

The analytical framework was based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)—including perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use (PEU), and behavioral intention (BI)—as well as two core components of the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework: Technological Content Knowledge (TCK) and Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK). As illustrated in

Figure 1, a deductive approach was adopted, using these theoretical constructs as a priori categories for consistent data collection and analysis [

24].

2.2. Participants

Three elementary school teachers who had prior experience integrating AR climbing into their PE classes participated in this study. The selection criteria were as follows:

(1) at least six months of instructional experience using AR climbing content;

(2) active involvement in the instructional design process, including setting goals, organizing content, implementing teaching strategies, and conducting assessments; and

(3) the ability to articulate their perceptions and instructional practices in detail.

All participants were fully informed of the study’s purpose and procedures and voluntarily consented to participate. Pseudonyms were used to protect their anonymity. Detailed participant profiles are presented in

Table 1.

2.3. Semi-Structured Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted remotely via telephone, email, and messenger platforms. Each participant completed two interview sessions, each lasting approximately 60 minutes. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and included in the analysis.

Interview questions were developed based on TAM (PU, PEU, BI) and TPACK (TCK, TPK) frameworks, and were organized around key components of instructional design such as objectives, content, methods, assessment, strategies, and cautions (see

Table 2).

2.4. Supplementary Survey

To enhance the external consistency of the TAM-based qualitative analysis, a supplementary survey was included. The data were derived from a user satisfaction survey conducted with 130 general visitors who experienced AR climbing at the 2024 SPOEX exhibition. The dataset was provided by the company that developed the content and was deemed theoretically relevant to the TAM framework by the researchers.

The questionnaire included five closed-ended items on a five-point Likert scale and two open-ended items. The closed items covered usefulness (physical activity, enjoyment), ease of use (sensor responsiveness, realism), and behavioral intention (continued use). The open-ended items asked about perceived strengths and weaknesses of the AR content. The items were reviewed by three experts in AR education, and content validity was established. The internal consistency of the scale was confirmed (Cronbach’s α = 0.86).

As the survey participants were general users rather than teachers, the data were not used as primary evidence but served as supplementary data to enhance the external coherence of the TAM–TPACK framework. This approach functioned as a form of triangulation to enhance the trustworthiness of the findings.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using

directed content analysis, applying the TAM–TPACK theoretical framework as a deductive coding scheme [

25]. Interview transcripts and open-ended survey responses were converted into textual units and classified according to predefined theoretical categories. Repeated meaning units were grouped into subcategories, and analysis focused on the relationships between TAM (PU, PEU, BI) and TPACK (TCK, TPK).

The analysis procedure included the development of a codebook, iterative coding, constant comparison, and memo writing. All steps were thoroughly documented to ensure procedural transparency.

2.6. Trustworthiness and Ethical Considerations

To ensure trustworthiness, the study employed triangulation, member checking, and referential adequacy strategies. First, triangulation was achieved by cross-validating findings from interviews, lesson materials, and the supplementary survey of 130 AR users, particularly regarding teachers’ TAM-related perceptions [

26,

27,

28]. Second, member checking was conducted by sharing the coded results with the teacher participants to verify whether the interpretations aligned with their intended meanings and instructional contexts [

29]. Third, referential adequacy was maintained by reserving a subset of the data for preliminary analysis and comparing it with the final interpretation to examine internal consistency [

30].

This study was exempted from ethical review by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Korea National University of Education. All participants were informed about the research purpose, procedures, and privacy policy, and voluntarily agreed to participate in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

3.1.1. Perceived Usefulness (PU)

(1) Educational Effectiveness

The participating teachers perceived AR climbing as having positive effects on students’ physical, emotional, and social development. The activity was associated with improvements in muscular strength, agility, endurance, and self-efficacy. Daniel remarked that “students developed both physical endurance and the ability to concentrate through this activity.” Grace highlighted that “team-based AR climbing enhanced flexibility and strengthened peer bonds,” while Alex emphasized the “sense of accomplishment upon completing routes, which significantly boosted students’ confidence.” The survey results supported these observations. Over 55% of respondents agreed that AR climbing provided sufficient physical activity. Open-ended responses included statements such as “It’s as fun as a game,” and “It helped me improve my stamina while playing with friends,” reinforcing both the teachers’ perceptions and the broader educational potential of the content. These findings suggest that AR climbing contributes meaningfully to multidimensional learning experiences, extending beyond the mere technological novelty of its implementation.

(2) Motivational Impact

Teachers also noted that AR climbing enhanced students’ intrinsic motivation and engagement. Grace stated that “AR-based lessons aligned with students’ preferences and elevated their energy and participation.” Alex observed that “the gamified elements increased immersion and encouraged active involvement.” The survey echoed these views: 95% of respondents found the activity “enjoyable” (52% “strongly agree,” 43% “agree”), and 84% attributed their sense of immersion to sensor responsiveness and real-time feedback. Open responses included remarks such as “It was fun like a game,” and “It was my first AR experience, and it was engaging and accessible even for beginners.” Structurally, participants appreciated elements like “the two-player competition mode,” “variation within the same course,” and “combinations of vertical and horizontal routes,” which sustained their interest. Collectively, these findings indicate that AR climbing operates not merely as physical activity, but as a gamified learning experience that fosters students’ engagement, challenge-seeking, and immersion.

3.1.2. Perceived Ease of Use (PEU)

(1) Difficulties in Implementation

Teachers reported multiple challenges in applying AR climbing in real classrooms, including equipment integration, operational complexity, and maintenance. Daniel noted, “It’s difficult to manage multiple devices simultaneously; user manuals and teacher training are necessary.” Grace emphasized the need for “pre-session guidance on system operation and content updates,” and Alex warned of “potential system errors or safety issues due to environmental factors or users’ inexperience.” Similar concerns emerged from the survey. Participants frequently cited limited variety of climbing holds, sensor misrecognition, and low input accuracy. These findings suggest that the successful application of AR content requires not only system stability, but also sufficient technological knowledge (TK) on the part of teachers.

(2) Suggested Improvements

Teachers proposed both hardware improvements and structured professional development to enhance usability. Grace recommended “head-mounted sensors to improve motion recognition,” and also suggested adjustable hold heights for safety and immersion. Alex proposed a three-step training model: “interface familiarization → motion practice → problem-solving workshop.” These suggestions underscore the link between technological knowledge (TK) and instructional feasibility, highlighting the need for TPACK-based teacher training rather than focusing solely on technical reliability to ensure sustainable use of AR in education.

3.1.3. Behavioral Intention (BI)

(1) Willingness to Continue Use

According to the survey, 76% of respondents expressed a desire to continue using AR climbing in the future. However, actual implementation was constrained by administrative decisions and budgetary limitations. All participating teachers noted that “support from school administrators is essential due to the high cost of equipment.” This suggests that technology adoption is influenced not only by individual attitudes but also by institutional factors. Alex observed that “even students without prior climbing experience could easily engage with the content due to its gamified design,” indicating that AR climbing can expand accessibility to physical activity for diverse learners. These insights call for an extension of the TAM framework to the organizational level, where sustained adoption is conditioned by both personal and structural support.

(2) Recommendations for Sustainability

Teachers emphasized three conditions for sustainable use of AR climbing: technical stability, budget support, and systematic teacher training. Grace acknowledged that “the content is highly accessible,” but also stated that “equipment costs are prohibitive for schools to afford independently.” Daniel stressed the importance of “pre-training and in-class technical support to build confidence and maintain lesson stability.” These findings suggest that sustained integration of digital technology in PE depends not only on individual acceptance but also on institutional infrastructures such as funding, maintenance, and human resources. A combined model—strengthening both teacher capacity and organizational support—is therefore required to ensure long-term viability.

3.2. Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)

3.2.1. Technological Content Knowledge (TCK)

(1) Goal Setting

Teachers demonstrated varying interpretations of learning goals when applying AR climbing, reflecting differences in their utilization of TCK. While Alex focused on the functional benefits of AR climbing—particularly its ability to stimulate physical activity—Daniel and Grace raised questions about the content’s curricular alignment and disciplinary authenticity. Alex described AR climbing as a “safe entry-level climbing activity” and emphasized its potential to improve students’ engagement and fundamental movement skills. This illustrates a function-oriented application of TCK. In contrast, Daniel argued that “AR climbing does not correspond to standard sport climbing events such as lead or speed climbing,” warning that students may perceive it merely as “a game-like wall-based activity.” Grace similarly stated that the content “lacks ecological validity,” suggesting that, much like screen golf diverges from actual golf, AR climbing functions more as a simulation than a sport. These contrasting views illustrate the tension within TCK between perceived educational utility and curricular fidelity. Effective use of AR content, therefore, demands not only creative instructional design but also critical reflection on its pedagogical alignment with subject-specific goals.

(2) Lesson Structure

Teachers emphasized the importance of transforming AR climbing from a one-off experience into a sustained learning sequence. Alex designed a ten-session unit, beginning with instruction on basic postures and grips and gradually progressing toward complex route-solving tasks. Each session followed a structured sequence: warm-up, explanation, demonstration, main activity, and cooldown. This structure exemplifies how TCK supports curricular sequencing and scaffolding, with difficulty levels and repetitive practice adapted to student readiness. It demonstrates the role of TCK in aligning technological affordances with progressive learning objectives.

(3) Grade-Level and Group Structuring

Teachers considered AR climbing most suitable for grades 3 to 5 (ages 8–11), noting that this age group balances physical capability with sustained attention. Lower grades (ages 6–8) posed challenges in classroom management, while upper grades (ages 10–12) showed decreased interest. Operational efficiency was also a key concern. Daniel recommended limiting each device to five students to minimize wait times and maintain focus. Alex similarly observed increased attention and engagement in small-group settings. Survey findings echoed this, with many users describing AR climbing as “accessible and effective for beginners.” These insights underscore that successful implementation relies less on technology itself and more on context-sensitive instructional adaptation to learner characteristics and classroom dynamics.

(4) Assessment Methods

Assessment practices in AR climbing lessons integrated quantitative metrics and qualitative observation. Alex used the PAPS (Physical Activity Promotion System) scores to measure physical fitness gains, maintaining alignment with national health standards. Grace observed peer interactions during cooperative activities and treated behaviors such as encouragement and guidance as indicators of socioemotional development. Daniel focused on resilience and self-direction, particularly students’ responses to repeated attempts and failures. These examples illustrate how AR climbing can facilitate multi-domain assessment—encompassing cognitive, physical, and affective outcomes—and how TCK strengthens the coherence between instruction and evaluation.

3.2.2. Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK)

(1) Student Engagement Strategies

Teachers did not treat AR climbing merely as a technological tool, but as a pedagogical medium whose instructional value depended on strategic use. Alex introduced pre-task route analysis and structured student teams to promote autonomy and sustained concentration. Daniel incorporated external motivators such as in-school competitions and team formats to enhance engagement beyond the classroom. These examples reveal that TPK involves not just tool functionality, but recontextualizing technology within the social and pedagogical fabric of instruction.

(2) Managing Wait Time

Limited equipment availability introduced challenges related to student downtime. Alex addressed this by incorporating cognitively engaging pre-tasks such as “route prediction activities” and providing parallel tasks to minimize inactivity. Daniel maintained engagement by organizing groups of five or fewer, improving focus and instructional density. These strategies reflect how TPK contributes to classroom flow management, attention regulation, and behavior continuity, supporting pedagogical coherence in tech-enhanced environments.

(3) Instructional Flexibility

Teachers applied AR climbing flexibly across various instructional settings. Daniel used it both in a ten-session afterschool program and as a rotating station in regular PE. Grace employed it as part of warm-up routines to enhance flexibility and mitigate monotony. Alex emphasized that “even teachers without climbing expertise could implement it easily,” positioning AR climbing as a tool for both experiential learning and career exploration. Such uses highlight the pragmatic adaptability of TPK, which enables teachers to reconfigure digital content according to curricular goals and situational constraints.

(4) Pedagogical Considerations

AR climbing lessons required careful attention to multiple instructional dynamics, including peer interaction, motor learning, focus retention, and lesson pacing. Daniel emphasized continuous feedback as a means to encourage supportive peer behavior, reinforcing the importance of social-emotional learning. Grace cautioned that game-centered instruction might overlook essential movement skills such as posture and landing technique. She stressed the need to balance engagement with systematic skill development. Concerns were also raised about excessive competitiveness undermining inclusive goals. Alex pointed out declining attention in repeated sessions and advocated for varied content and strategic time management. These insights reaffirm that the core of TPK lies in pedagogical adaptability—not in the technology itself, but in the teacher’s ability to orchestrate instructional conditions. The success of digital PE instruction thus depends on teachers’ practical expertise rather than the affordances of the tool alone.

4. Discussion

4.1. Technology Acceptance Model (TAM): Acceptance of AR Climbing in Elementary PE

4.1.1. Perceived Usefulness (PU)

Teachers consistently recognized the educational utility of AR climbing across physical, emotional, and social domains. Daniel highlighted improvements in grip strength and peer bonding, Grace emphasized flexibility and teamwork, and Alex underscored enhanced problem-solving and self-efficacy. These findings suggest that PU extends beyond technical performance to encompass social-emotional learning

(SEL) and bodily self-awareness. This aligns with Davis’s foundational TAM framework [

12] as well as recent studies linking educational technology with socioemotional development [

31,

32,

33].

Survey results corroborated these perceptions: 80% of respondents agreed that AR climbing provided sufficient physical activity, and 95% found it enjoyable. Open-ended responses such as “It felt like a game but made me sweat” and “I liked doing it with friends” reflect

intrinsic motivation—a known predictor of sustained participation in PE, as emphasized in prior research [

34,

35].

4.1.2. Perceived Ease of Use (PEU)

Despite its perceived benefits, teachers identified practical challenges in operating AR content. Daniel reported recurrent system instability, Grace highlighted challenges with unfamiliar interfaces and maintenance responsibilities, and Alex noted sensor inaccuracies affecting user immersion. These cases confirm the centrality of usability and system reliability in technology acceptance, echoing findings that PEU and self-efficacy are key determinants of digital engagement [

36,

37].

To address these issues, teachers proposed structured training and hardware refinements. Alex suggested a three-phase model (system control – biomechanical comprehension – troubleshooting practice), and Grace recommended sensor calibration improvements. These proposals mirror the aims of TPACK theory [

14], which emphasizes the transformation of technological knowledge into actionable teaching strategies. The variability of PEU across contexts further implies that ease of use is shaped not only by design, but also by teachers’ technological enactment capacity.

4.1.3. Behavioral Intention (BI)

Teachers’ intent to continue using AR content was largely shaped by institutional conditions. As noted by Park and Lee, “The decision to apply digital content is often administrative, not discretionary,” underscoring the relevance of external variables in extended TAM models [

12]. While 76% of survey respondents expressed a willingness to reuse AR climbing, teachers emphasized the need for budgetary, training, technical, and policy supports to enable meaningful implementation.

Daniel stressed the importance of intuitive interfaces and secured funding, Grace called for technical staff and formal training programs, and Lee emphasized the necessity of collaborative structures between school leadership and teachers. These insights suggest that although BI originates from personal beliefs, institutional infrastructure is essential for sustained enactment [

6,

18].

Taken together, TAM offers a robust framework for understanding both the motivational appeal and operational constraints of AR integration in PE. Teachers’ acceptance was not driven solely by perceptions of utility; rather, it emerged from a broader network of contextual enablers—including usability, training systems, and administrative environments—that support actual classroom implementation.

4.2. TPACK: Instructional Enactment of AR Climbing in Elementary PE

4.2.1. Technological Content Knowledge (TCK)

Teachers perceived AR climbing as simulating specific sub-skills such as bouldering, functioning as an accessible entry point into physical activity. Alex emphasized its role in reducing psychological barriers to participation, aiming to help students enhance their physical capacity without fear. However, Daniel raised concerns regarding its limited alignment with more advanced forms like lead or speed climbing, and Grace compared it to screen golf—suggesting that, while engaging, it lacks ecological fidelity.

These views imply that AR climbing functions as a partial metonymy of authentic sport climbing—capturing certain technical elements like route solving and grip technique, while omitting others such as spatial perception, equipment use, and risk management [

38]. Thus, TCK in physical education must include critical evaluations of representational integrity and the potential for skill transfer.

Moreover, AR climbing embeds affordances—perceptual cues that guide motor engagement. According to ecological theory, affordances structure behavior by offering actionable possibilities to the user [

39]. The content design of AR systems thus directly shapes students’ embodied responses and contributes to the quality of motor learning experiences.

4.2.2. Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK)

Teachers employed diverse strategies to integrate AR climbing into instructional routines. Alex used route previews, team-based activities, and pre-task cognitive exercises to enhance immersion. Daniel implemented school-wide competitions and encouraged autonomous route completion, while Grace utilized AR content as part of warm-up or strength-building routines.

These practices reflected the core principles of digital integration—goal alignment, instructional restructuring, and contextual flexibility. Similar reconfigurations have been observed in AR-based geography education [

40], reinforcing that teachers adapt pedagogical methods in response to new content types. This aligns with studies that call for lesson design to be reorganized around technological affordances [

41].

Particularly in physical education, where immediacy, bodily movement, and spatiality are essential, technology must function not only as a content carrier but as a design medium. In this study, TPK-based strategies—such as restructuring participation, managing instructional flow, and scaffolding peer interaction—transformed AR content into lessons that integrated assessment, motor learning, and SEL [

42].

TPACK thus served as an effective analytical lens for understanding how teachers designed and enacted AR-based PE instruction. TCK facilitated critical appraisal of content alignment and physical transferability, while TPK enabled adaptive implementation. Together, they supported a coherent framework for integrating technological affordances into high-quality instructional practice.

4.3. Instructional Feasibility of AR-Based PE via TAM–TPACK Integration

This section considers how TAM and TPACK interacted during teachers’ implementation of AR climbing in PE. The findings indicated a strong correspondence between PU and TCK, PEU and TPK, and BI and the broader TPACK structure—highlighting a mutually reinforcing architecture for digital integration.

Teachers viewed AR climbing not simply as an engaging tool, but as a resource that supports physical fitness, social bonding, and self-efficacy. These perceptions aligned with TCK-informed goal setting. Alex emphasized autonomous problem-solving, while Grace emphasized cooperation and confidence-building. This reflects prior findings that PU positively affects both students’ motivation and teachers’ instructional planning [

43,

44]. Jang et al. [

45] similarly argued that PU enhances self-efficacy and motivation in AR-based PE, positioning TCK as a facilitator of goal-oriented technology use.

PEU was linked to the practical feasibility of instruction and therefore aligned with TPK. Grace noted that although AR tools initially seemed complex, these challenges could be overcome through systematic training. This supports the notion that technological self-efficacy strengthens teachers’ capacity for digital integration [

46]. Research by MARAM also showed that enjoyment and self-efficacy mediate the relationship between PEU and BI, emphasizing the close link between teacher readiness and instructional execution [

47]. Thohir et al. [

48] added that effective integration depends not only on usability, but also on infrastructure, physical space, and institutional support.

Behavioral intention (BI) functioned not merely as a TAM outcome but as a driver of instructional transformation. Teachers shifted away from traditional competition-focused lessons to cooperative and challenge-based models. This approach aligns with Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which emphasizes autonomy, competence, and relatedness [

50], and supports findings that AR-based PE can better facilitate intrinsic motivation than conventional approaches.

Such pedagogical restructuring is consistent with Centeio et al. [

51], who noted that teachers adapted their strategies to maintain engagement during the pandemic. This underscores that TPACK capacity, rather than mere technological familiarity, is the core engine for innovation. Ertmer [

52] cautioned that entrenched beliefs can hinder adoption, while Cendra et al. [

53] argued that the strength of TPACK directly determines the quality of digital lesson design.

These insights suggest that the PU–TCK, PEU–TPK, and BI–TPACK pathways reflect not separate models but a coherent instructional system. When teachers possess the capacity to design, operate, and adapt technology within a pedagogical frame, acceptance becomes a natural outcome. This reinforces the need for TPACK-based professional development and structural support to achieve sustainable digital physical education.

5. Policy Implications for Sustainable Integration of Digital Physical Education

This study demonstrated that AR-based instruction in elementary physical education can enhance students’ participation, engagement, and diversity of movement experiences. Rather than functioning merely as a media supplement, AR can facilitate qualitative transformations in instructional structure. By integrating the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK), this study highlights the necessity of overcoming the adverse effects of indiscriminate digital adoption—such as instructional inefficiency and teacher stress—and calls for systematic policy frameworks that enhance the educational utility of emerging technologies. Accordingly, the following policy implications are proposed.

First, standardized criteria for technology acceptance in digital physical education should be established. When advanced technologies such as AR are introduced into educational settings, instructional acceptance criteria informed by TAM and TPACK frameworks should be established. These standards should extend beyond functional evaluation and operate as educational validation systems that assess the feasibility of instructional redesign, teaching effectiveness, and learner responsiveness. Such a framework should be institutionalized at the ministerial or national level as part of formal guidelines for evaluating the pedagogical appropriateness of new technologies.

Second, context-responsive instructional materials and teacher training must be provided in an integrated manner. The effective integration of digital technology is largely determined by teachers’ capacity for instructional design. Therefore, training programs should be modular and context-based, combining Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK) and Technological Content Knowledge (TCK) within a curriculum-linked structure [

14,

54]. In addition to delivering training, the system must incorporate teachers’ voices from the field and ensure connections between training completion and classroom implementation. These resources and training modules should be continuously curated, shared, and expanded through a centralized repository for collective teacher access.

Third, institutional incentives should be introduced to promote teacher participation. Technology-based lessons impose considerable implementation burdens on teachers. As TAM suggests, if teachers do not perceive the necessity of technology adoption, actual application remains unlikely. Therefore, teachers engaged in digital instruction should be offered tangible incentives such as additional teaching hours, opportunities to present exemplary practices, and small-scale research grants. These incentives should be embedded within evaluation frameworks operated by local education offices and municipalities to ensure systematic institutional support.

Fourth, school-level infrastructure and regionally grounded expansion strategies must be developed simultaneously. AR-based instruction requires physical infrastructure—spatial resources, equipment, and technical assistance—that cannot be secured by individual schools alone. Accordingly, operational systems such as shared-use spaces, safety protocols, and technical staffing must be implemented. Pilot projects for digital physical education should prioritize under-resourced areas, such as rural or small-city schools, adopting an equity-based approach to implementation. At the same time, the outcomes of these pilot programs must be systematically evaluated and scaled through national–local collaboration models that align with the national curriculum.

Taken together, sustainable digital physical education should move away from uncritical technology deployment and instead pursue an integrated approach involving standardized acceptance criteria, curriculum-based resource and training systems, teacher motivation policies, and institutional infrastructure development. This study contributes both a theoretical foundation and practical evidence for policy design aimed at institutionalizing technology-integrated PE instruction.

6. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study provides meaningful implications for the pedagogical integration of digital tools in elementary physical education by analyzing the instructional acceptance and practical application of AR climbing through the integrated framework of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK). Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged.

First, the study was limited to three teachers who had experience implementing AR in real classroom contexts. This narrow sample constrains the generalizability of the findings. Future research should include a broader range of participants representing diverse regions, school types, and teacher backgrounds to identify more universal patterns in the acceptance and implementation of digital PE instruction.

Second, student perspectives and learning outcomes were not directly examined. While this study focused on teachers' experiences, subsequent research should incorporate student interviews, classroom observations, and assessments of learning outcomes and physical activity levels to comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness and acceptability of AR-based PE instruction from multiple angles.

Third, the study did not empirically assess the causal effects of AR integration. Although this research employed a qualitative approach, future studies should adopt experimental or quasi-experimental designs to measure outcomes such as motivation, physical fitness, and activity engagement using validated tools (e.g., PAPS). Subgroup analyses by gender or ability level may also offer valuable insights.

Finally, while this study proposed conceptual linkages between TAM and TPACK components (i.e., PU–TCK, PEU–TPK, and BI–TPACK), these relationships were not empirically validated. Further research should utilize structural equation modeling (SEM) or partial least squares SEM (PLS-SEM) to examine the structural validity of the proposed integrated framework.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to practice-oriented scholarship by analyzing a real-world case of digital integration in elementary PE through a robust theoretical lens. Future research should build on these findings to establish more refined empirical evidence and theoretical models that support the sustainable digital transformation of physical education.

7. Conclusions

This study explored how augmented reality (AR) climbing content is accepted and integrated into elementary physical education (PE) classes through “teacher-centered instructional design”. By applying an integrated framework of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK), the study aimed to reveal the structural connection between teacher perceptions and instructional enactment in digital PE. While the findings are grounded in specific cases, the study empirically demonstrated that digital tools can function effectively in real instructional contexts when design and implementation are initiated from the teacher's perspective. The use of triangulation—through in-depth interviews, user surveys, and instructional materials—further enhanced the trustworthiness of the interpretations.

First, teachers’ technology acceptance emerged as a prerequisite for the realization of digitally integrated PE instruction. This process went beyond mere tool usage and involved teacher-led evaluation of the educational relevance and contextual suitability of the technology. The core TAM elements—Perceived Usefulness (PU), Perceived Ease of Use (PEU), and Behavioral Intention (BI)—mediated instructional goal setting, operational feasibility, and design intent, respectively, and influenced the overall structure of lesson planning.

Second, the post-acceptance phase involved the contextualization of technology within instruction, operationalized through the TPACK framework. Specifically, Technological Content Knowledge (TCK) supported the alignment of AR functions with curricular goals and content, while Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK) guided the transformation of these functions into effective teaching strategies. Together, these components within the TPACK framework enabled teachers to manage both the contextual alignment and practical implementation of AR content, thus ensuring its instructional feasibility.

Third, the interplay between TAM and TPACK was observed through the structural correspondences between PU–TCK, PEU–TPK, and BI–TPACK. These relationships illustrate how technology acceptance transitions into design-driven execution. This finding suggests that digital PE instruction realizes its full potential not simply through the adoption of technology, but when such adoption is embedded in teachers’ pedagogical judgments and instructional capabilities.

Taken as a whole, the TAM–TPACK framework served not only as an interpretive tool for understanding educational acceptance and implementation of digital technologies, but also as a practical prerequisite for integrating such tools into PE classes. In subject areas like physical education, where physical activity and learning contexts are tightly interwoven, teacher expertise and design competence—not the technology itself—are the determining factors in successful integration.

Therefore, to ensure the sustainability of digital PE instruction, it is essential to establish TAM–TPACK-based acceptance criteria, provide curriculum-aligned and context-sensitive instructional resources and training programs, and offer institutional supports such as teacher incentives to strengthen behavioral intention. When these conditions are organically connected, digital technologies can move beyond temporary adoption and be institutionalized as part of a sustainable instructional structure. This reflects a shift not toward technology-centered reform, but toward teacher-centered digital transformation, which lies at the core of meaningful educational innovation.

Such insights not only broaden the practical possibilities for digital physical education but also make clear that teacher-centered and user-informed approaches are crucial determinants for the success of technology-integrated instruction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-W.P. and S.-B.L.; methodology, S.-B.L. and S.-W.P.; data collection, K.-J.S.; analysis, S.-W.P. and S.-B.L.; investigation, K.-J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-W.P.; writing—review and editing, S.-B.L.; supervision, K.-J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received an exemption from ethical review by the Institutional Review Board of Korea National University of Education.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants and their legal guardians provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study. Written informed consent was also obtained for the publication of anonymized data.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions related to personal information protection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participating teachers for their time, insight, and commitment to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Schmalstieg, D., & Hollerer, T. (2016). Augmented reality: Principles and practice. Addison-Wesley Professional.

- Huang, Y. (2013). Design guidelines and prototype development of a mobile augmented reality education system based on affordance theory (Doctoral dissertation, Hanyang University, Seoul).

- Soltani, P., & Morice, A. H. P. (2020). Augmented reality tools for sports education and training. Computers & Education, 155, 103923. [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification.” In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference (pp. 9–15). [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G., Keramopoulos, E., Diamantaras, K., & Evangelidis, G. (2022). Augmented reality and gamification in education: A systematic literature review of research, applications, and empirical studies. Applied Sciences, 12(13), 6809. [CrossRef]

- Gill, A., Irwin, D., Towey, D., Zhang, Y., Li, B., Sun, L., Wang, Z., Yu, W., Zhang, R., & Zheng, Y. (2023, November). Effects of augmented reality gamification on students’ intrinsic motivation and performance. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Teaching, Assessment and Learning for Engineering (TALE) (pp. 1–8). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Esto, J. B. (2024). Technological pedagogical content knowledge self-efficacy of Filipino physical education teachers in rural communities. The International Journal of Technologies in Learning, 31(1), 91–102. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382452931.

- Juniu, S. (2011). Pedagogical uses of technology in physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 82(9), 41–49. [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Muñoz, C., Castillo, D., Vega-Muñoz, A., & Boada-Grau, J. (2020). Teacher technostress in the Chilean school system. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5280. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Batanero, J. M., Román-Graván, P., Reyes-Rebollo, M. M., & Montenegro-Rueda, M. (2021). Impact of educational technology on teacher stress and anxiety: A literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 548. [CrossRef]

- Sancho-Gil, J. M., Rivera-Vargas, P., & Miño-Puigcercós, R. (2019). Moving beyond the predictable failure of Ed-Tech initiatives. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(1), 61–75. [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [CrossRef]

- Ping, L., & Liu, K. (2020). Using the technology acceptance model to analyze K–12 students’ behavioral intention to use augmented reality in learning. Texas Education Review, 8(2), 37–51. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054.

- Koh, J. H. L., Chai, C. S., & Tsai, C. C. (2010). Facilitating pre-service teachers’ development of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK). Educational Technology & Society, 13(4), 63–73.

- Rosmawati, Y., Astuti, Y., Wulandari, I., Erianti, & Hartika, R. F. (2023). Application of the technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) learning model in the student measurement and evaluation test course in the department of sports education. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 23(20), 241–250.

- Moreno-Guerrero, A.-J., Marín-Marín, J.-A., López-Belmonte, J., & Rodríguez-García, A.-M. (2020). Augmented reality as a resource for improving learning in the physical education classroom. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3637. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M., Yu, L., Ma, X., & Xu, M. (2021). Towards an understanding of situated AR visualization for basketball free-throw training. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–13). [CrossRef]

- Vignais, N., Kulpa, R., Brault, S., Presse, D., & Bideau, B. (2015). Which technology to investigate visual perception in sport: Video vs. virtual reality. Human Movement Science, 39, 12–26. [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, N. M. (2020). Augmented reality: A systematic review of its benefits and challenges in E-learning contexts. Applied Sciences, 10(16), 5660. [CrossRef]

- Shin, S., & Kim, H. (2024). Pedagogical competence analysis based on the TPACK model: Focus on VR-based survival swimming instructors. Education Sciences, 14(5), 460. [CrossRef]

- Bores-García, D., Hortigüela-Alcalá, D., Hernández-Jorge, C., & González-Calvo, G. (2024). Educational research on the use of virtual reality combined with a practice teaching style in physical education. Education Sciences, 14(3), 291. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [CrossRef]

- Eisner, E. W. (2005). Reimagining schools: The selected works of Elliot W. Eisner. Routledge.

- Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75. [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE Publications.

- Sindiani, M., Al Shdaifat, E., & Quraan, A. (2025). Social–emotional learning in physical education classes at elementary schools. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1499240. [CrossRef]

- Casey, A., & Goodyear, V. A. (2015). Can cooperative learning achieve the four learning outcomes of physical education? A review of literature. Quest, 67(1), 56–72. [CrossRef]

- Opstoel, K., Chapelle, L., Prins, F. J., De Meester, A., Haerens, L., van Tartwijk, J., & De Martelaer, K. (2019). Personal and social development in physical education and sports: A review study. European Physical Education Review, 26(4), 797–813. [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J., Shernoff, D. J., Rowe, E., Coller, B., Asbell-Clarke, J., & Edwards, T. (2016). Challenging games help students learn: An empirical study on engagement, flow and immersion in game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 170–179.

- Brown, E., & Cairns, P. (2004). A grounded investigation of game immersion. In CHI '04 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1297–1300).

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204.

- Shyr, W.-J., Wei, B.-L., & Liang, Y.-C. (2024). Evaluating students’ acceptance intention of augmented reality in automation systems using the Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability, 16(5), 2015. [CrossRef]

- Boschman, F., McKenney, S., & Voogt, J. (2014). Exploring teachers' use of TPACK in design talk: The collaborative design of technology-rich early literacy activities. Computers & Education, 82, 250–262. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Houghton Mifflin.

- Shelton, B. E., & Hedley, N. R. (2002, September 29). Using augmented reality for teaching Earth–Sun relationships to undergraduate geography students. Paper presented at The First IEEE International Augmented Reality Toolkit Workshop, Darmstadt, Germany. [CrossRef]

- Angeli, C., & Valanides, N. (2009). Epistemological and methodological issues for the conceptualization, development, and assessment of ICT-TPCK: Advances in technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK). Computers & Education, 52(1), 154–168. [CrossRef]

- Harris, J., Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2009). Teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge and learning activity types: Curriculum-based technology integration reframed. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 41(4), 393–416.

- Jang, J., Ko, Y., Shin, W. S., & Han, I. (2021). Augmented reality and virtual reality for learning: An examination using an extended technology acceptance model. IEEE Access, 9, 6798–6809. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Muñoz, S., Castaño Calle, R., Morales Campo, P. T., & Rodríguez-Cayetano, A. (2024). A systematic review of the use and effect of virtual reality, augmented reality and mixed reality in physical education. Information, 15(9), 582. [CrossRef]

- Jang, J., Ko, Y., Shin, W. S., & Han, I. (2021). Augmented reality and virtual reality for learning: An examination using an extended technology acceptance model. IEEE Access, 9, 6798–6809. [CrossRef]

- Teo, T. (2011). Factors influencing teachers’ intention to use technology: Model development and test. Computers & Education, 57(4), 2432–2440.

- Koutromanos, G., Mikropoulos, A. T., Mavridis, D., & Christogiannis, C. (2024). The mobile augmented reality acceptance model for teachers and future teachers. Education and Information Technologies, 29, 7855–7893.

- Thohir, M. A., Ahdhianto, E., Mas’ula, S., Yanti, F. A., & Sukarelawan, M. I. (2023). The effects of TPACK and facility condition on preservice teachers’ acceptance of virtual reality in science education course. Contemporary Educational Technology, 15(2), ep407. [CrossRef]

- Bores-García, D., Hortigüela-Alcalá, D., Fernández-Rio, F. J., González-Calvo, G., & Barba-Martín, R. (2021). Research on cooperative learning in physical education: Systematic review of the last five years. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 92(1), 146–155. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [CrossRef]

- Centeio, E. E., Mercier, K., Garn, A. C., Erwin, H., Marttinen, R., & Foley, J. T. (2021). The success and struggles of physical education teachers while teaching online during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 40(4), 667–673. [CrossRef]

- Ertmer, P. A. (2005). Teacher pedagogical beliefs: The final frontier in our quest for technology integration? Educational Technology Research and Development, 53(4), 25–39. [CrossRef]

- Cendra, R., Gazali, N., & Mubarok, Z. (2024). Integration of learning technology in physical education: A Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) theoretical framework. Jendela Olahraga, 9(2), 20–31. [CrossRef]

- Newsome, J. G., & Lederman, N. G. (1999). Examining pedagogical content knowledge: The construct and its implications for science education. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).