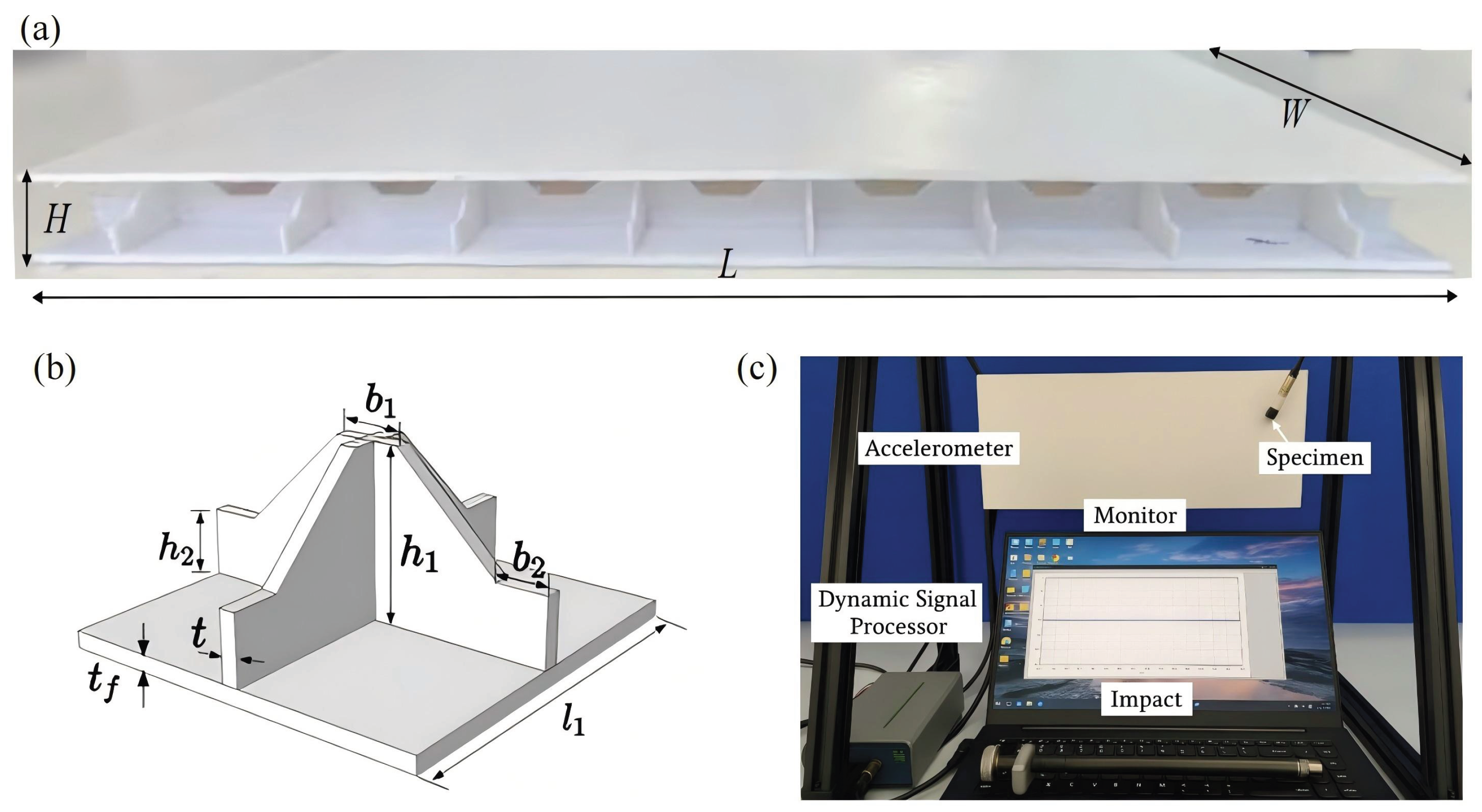

Static analysis plays a critical role in evaluating the structural integrity and load-bearing capacity of sandwich panels under various boundary and loading conditions. In this chapter, the static performance of the SP-EHC is examined using both 3D-FEM and the VAM-based 2D-EPM. The investigation covers buckling behavior under in-plane compression, out-of-plane bending with and without initial geometric imperfections, and localized stress and displacement field reconstruction.

4.2. Buckling Analysis Under In-Plane Loading

Buckling performance analysis of composite sandwich panels is of considerable engineering significance. Owing to their high strength-to-weight ratio, these structures are extensively employed in aerospace, civil engineering, and transportation, offering superior load-bearing capacity and structural stability. Buckling analysis facilitates the evaluation of instability risks under diverse loading and boundary conditions, providing a theoretical basis for structural optimization and safety evaluation.

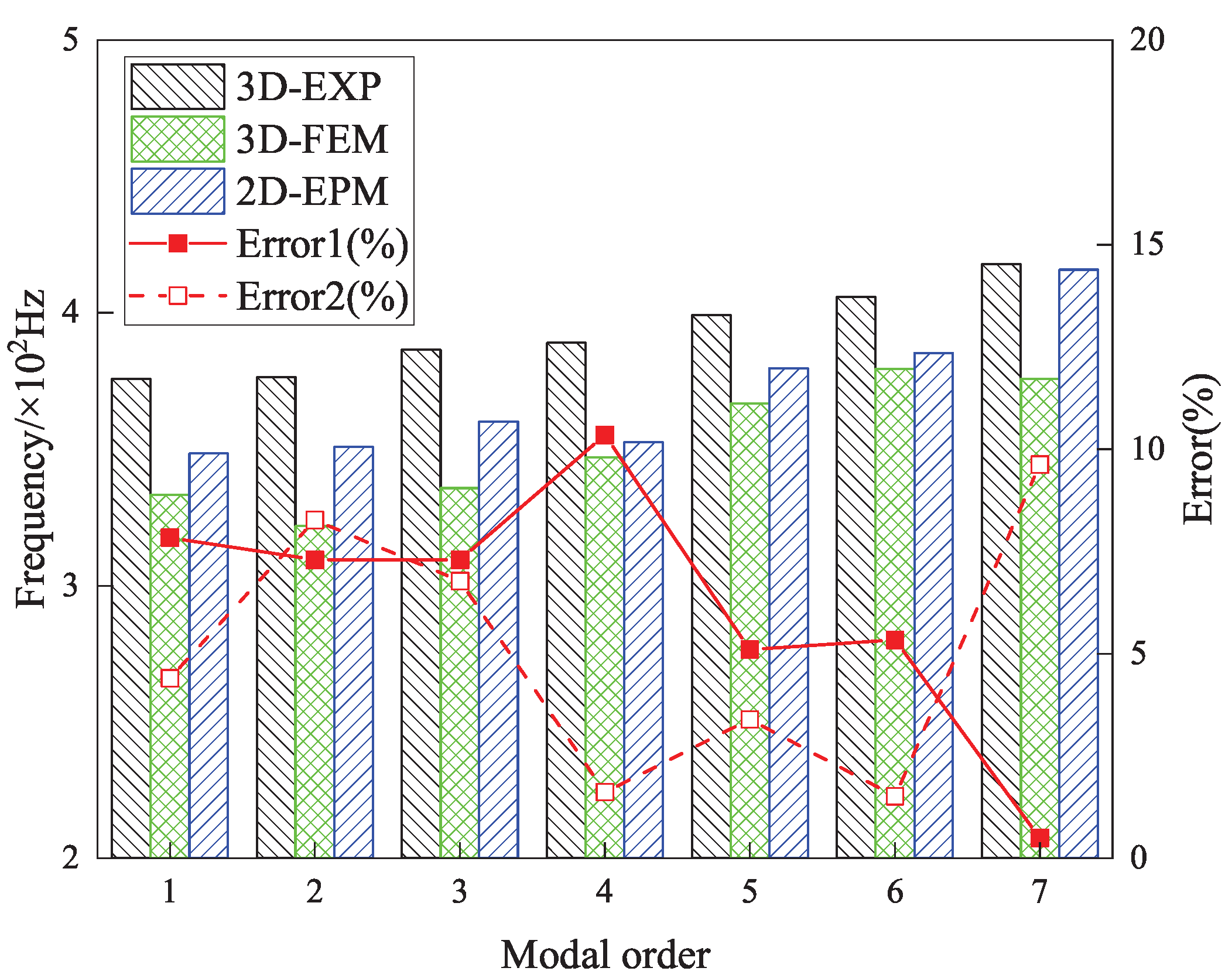

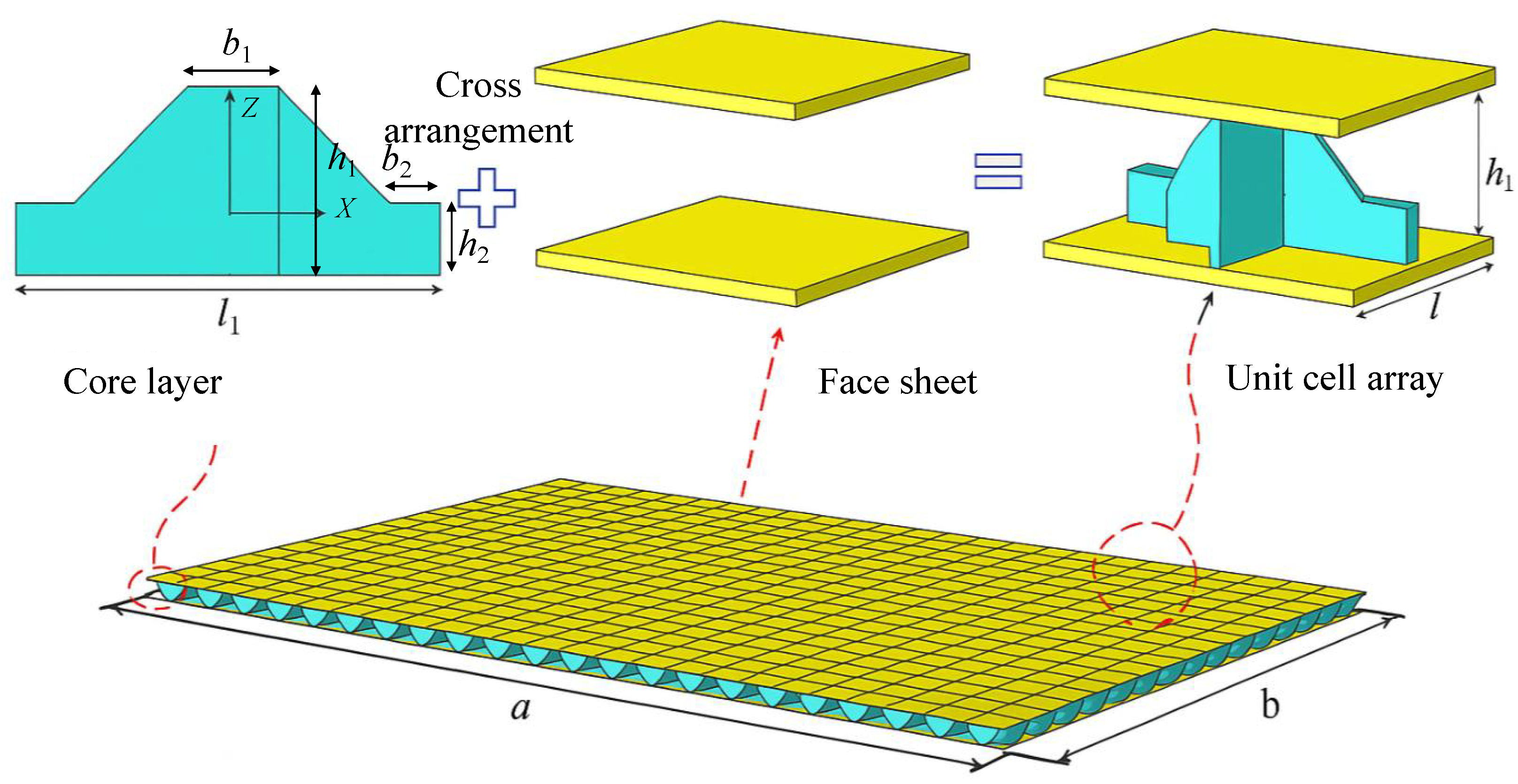

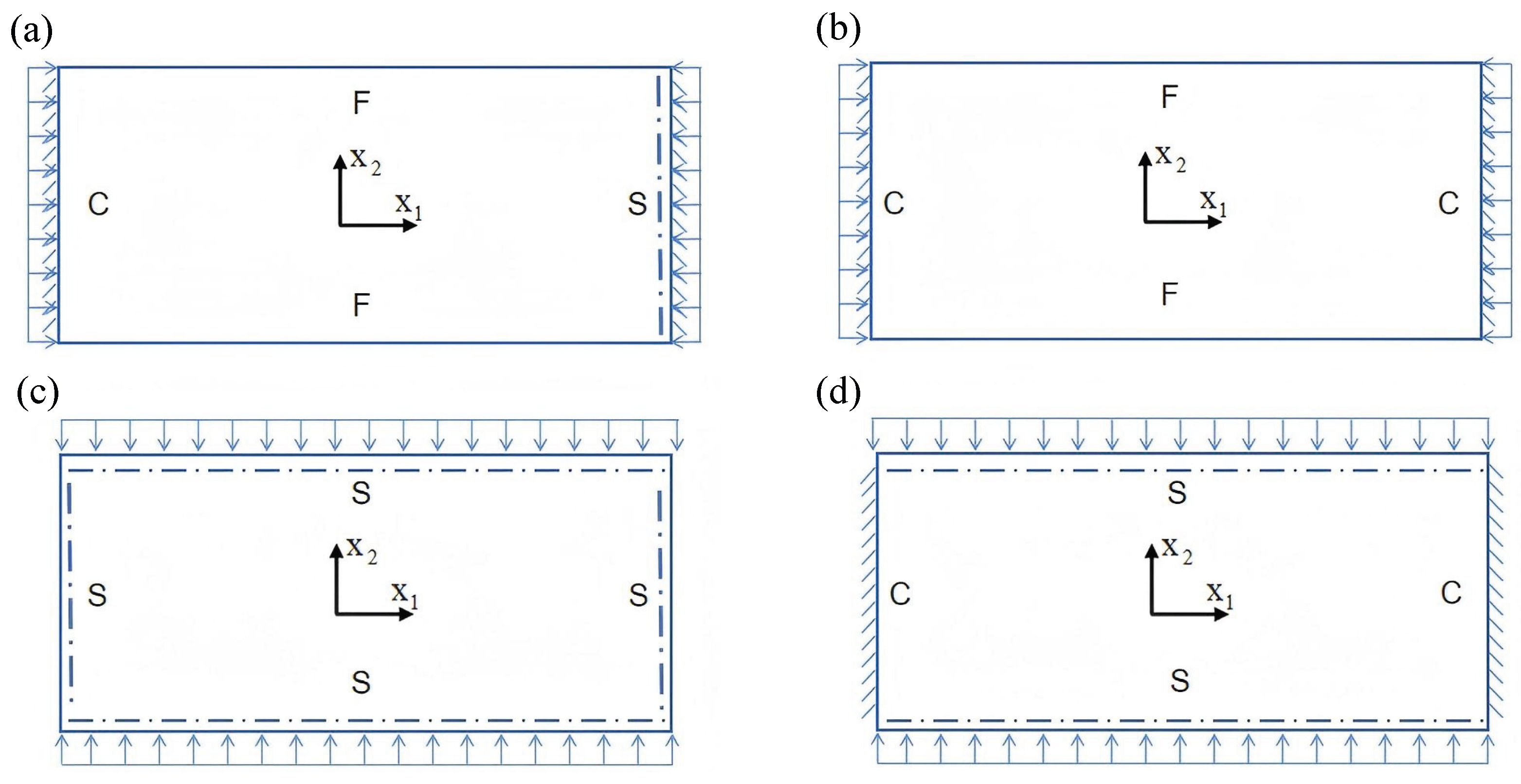

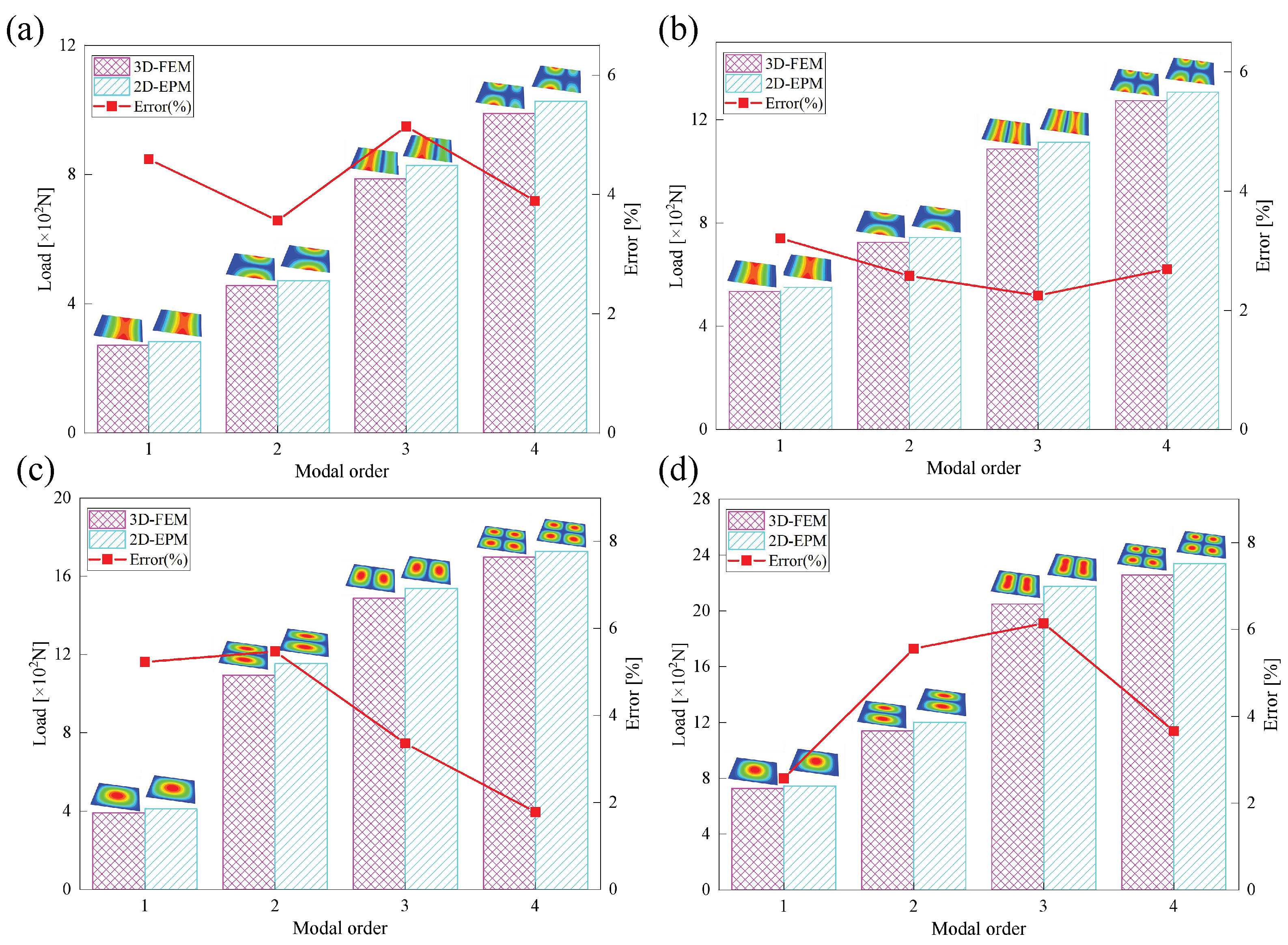

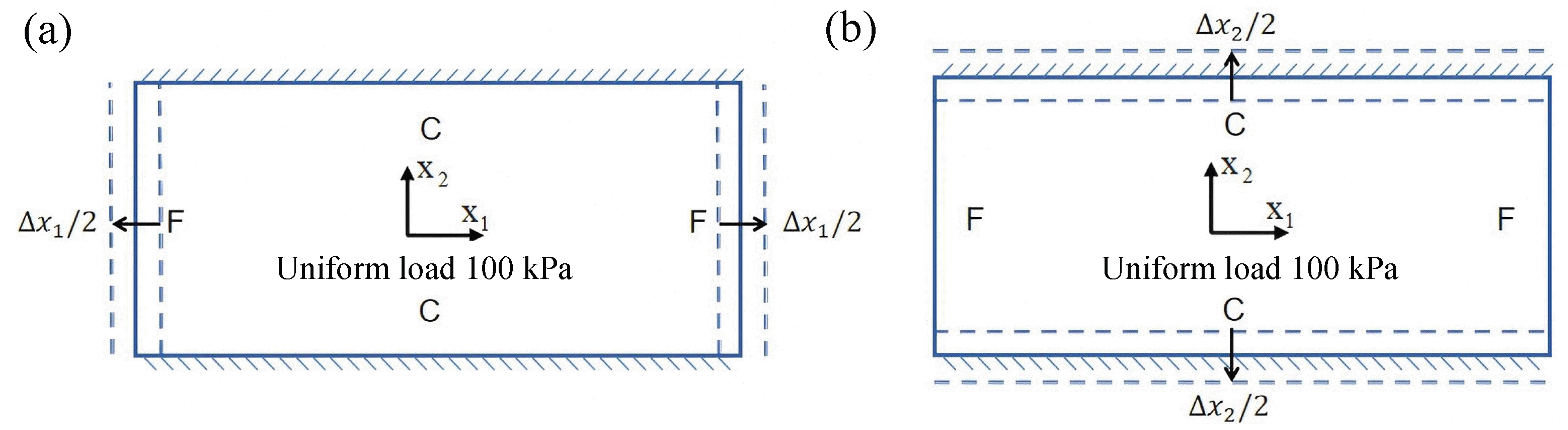

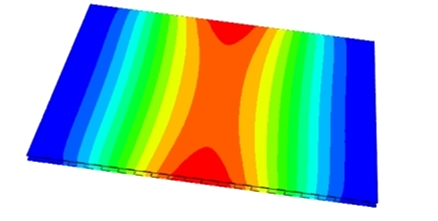

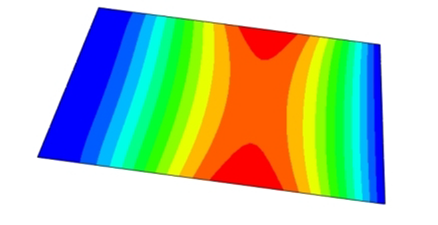

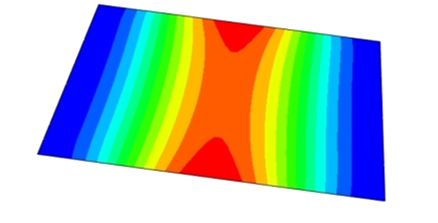

To evaluate the applicability of the 2D-EPM for buckling prediction, analyses were performed using both 3D-FEM and 2D-EPM under four representative boundary conditions, as shown in

Figure 9. In Cases 1 (CSFF) and 2 (CCFF), compressive loads were applied along the short edge, whereas in Cases 3 (SSSS) and 4 (CCSS), loading was applied along the long edge. Symmetric compression along the long edge is commonly employed to investigate the buckling behavior of sandwich panels under longitudinal loading. In practical applications, these panels often experience biaxial compression in the longitudinal direction due to self-weight, wind loads, and other external forces, potentially leading to in-plane buckling and a significant reduction in load-carrying capacity. Simulations under this loading condition enable effective evaluation of critical buckling loads, deformation characteristics, and failure modes, offering valuable insights for structural design.

Conversely, symmetric compression along the short edge examines the panel’s response to transverse loading. Scenarios such as lateral wind pressure or accidental impacts can induce local crushing or buckling near the short edges. This analysis facilitates a detailed assessment of local stiffness, compressive strength, and stability, thereby supporting safety evaluations under extreme loading conditions. A total compressive load of 1 N was applied at the boundaries in all cases; hence, the buckling eigenvalues obtained from the finite element analysis directly correspond to the critical buckling loads.

Table 3 compares the predicted first-order critical buckling loads and corresponding buckling modes of the SP-EHC under four typical boundary conditions, obtained using 2D-EPM and 3D-FEM. The results indicate that the critical buckling loads predicted by the two models show minimal discrepancies, with a maximum deviation of no more than 6%. Moreover, the buckling modes exhibit high morphological agreement, demonstrating that the 2D-EPM offers reliable accuracy and applicability for predicting the first-order buckling behavior of sandwich panels.

Detailed comparisons reveal that the critical buckling load in Case 2 is approximately twice that of Case 1, indicating that enhanced boundary constraints significantly improve structural stability. In addition, the buckling mode shapes reveal that stress concentration regions tend to shift toward the less constrained edges, indicating a higher likelihood of local instability initiating in areas with weaker restraint. A similar trend is observed between Cases 3 and 4, further underscoring the critical role of boundary conditions in influencing buckling behavior.

Notably, in the comparison between Cases 2 and 3, Case 3 exhibits a higher critical buckling load despite having weaker boundary constraints. This seemingly counterintuitive result is primarily attributed to differences in loading direction. When compression is applied along the long edge, the panel benefits from greater bending stiffness and improved buckling resistance. Additionally, the increased structural flexibility in this direction promotes stress redistribution, thereby reducing the likelihood of local buckling. In contrast, although Case 2 features stronger constraints under short-edge compression, it is more prone to stress concentrations and localized deformations, increasing its susceptibility to instability. These findings indicate that critical buckling performance is governed not only by boundary conditions but also by loading direction and structural geometry. Consequently, enhancing boundary support in conjunction with optimizing the loading path offers an effective strategy for improving the load-bearing capacity and buckling stability of sandwich panels.

Considering only the first-order buckling load may not fully capture the structural stability under realistic loading scenarios. Higher-order buckling modes often emerge at increased load levels and can significantly affect the overall instability mechanism, particularly under specific boundary or geometric conditions.

Figure 10 shows that the first four buckling mode shapes predicted by the 2D-EPM and 3D-FEM demonstrates strong consistency across various boundary conditions. The relative errors in the corresponding buckling loads remain within 10%, confirming the accuracy and effectiveness of the 2D-EPM in capturing higher-order buckling behavior.

The buckling response of the SP-EHC is highly sensitive to both boundary conditions and loading direction. The number and arrangement of clamped edges significantly influence the critical buckling load and mode shapes: increasing the number of fixed boundaries enhances the overall structural stiffness, elevates the critical load, and tends to localize failure near the constrained regions. In contrast, a higher proportion of free edges leads to more complex buckling deformations and a more dispersed failure pattern. The loading direction also plays a critical role. Under long-edge compression with free boundaries, buckling modes are more evenly distributed across the panel. In comparison, short-edge compression induces instability localized near the free edges, resulting in more intricate and concentrated deformation patterns.

4.3. Out-of-Plane Bending Analysis Without Initial Displacement

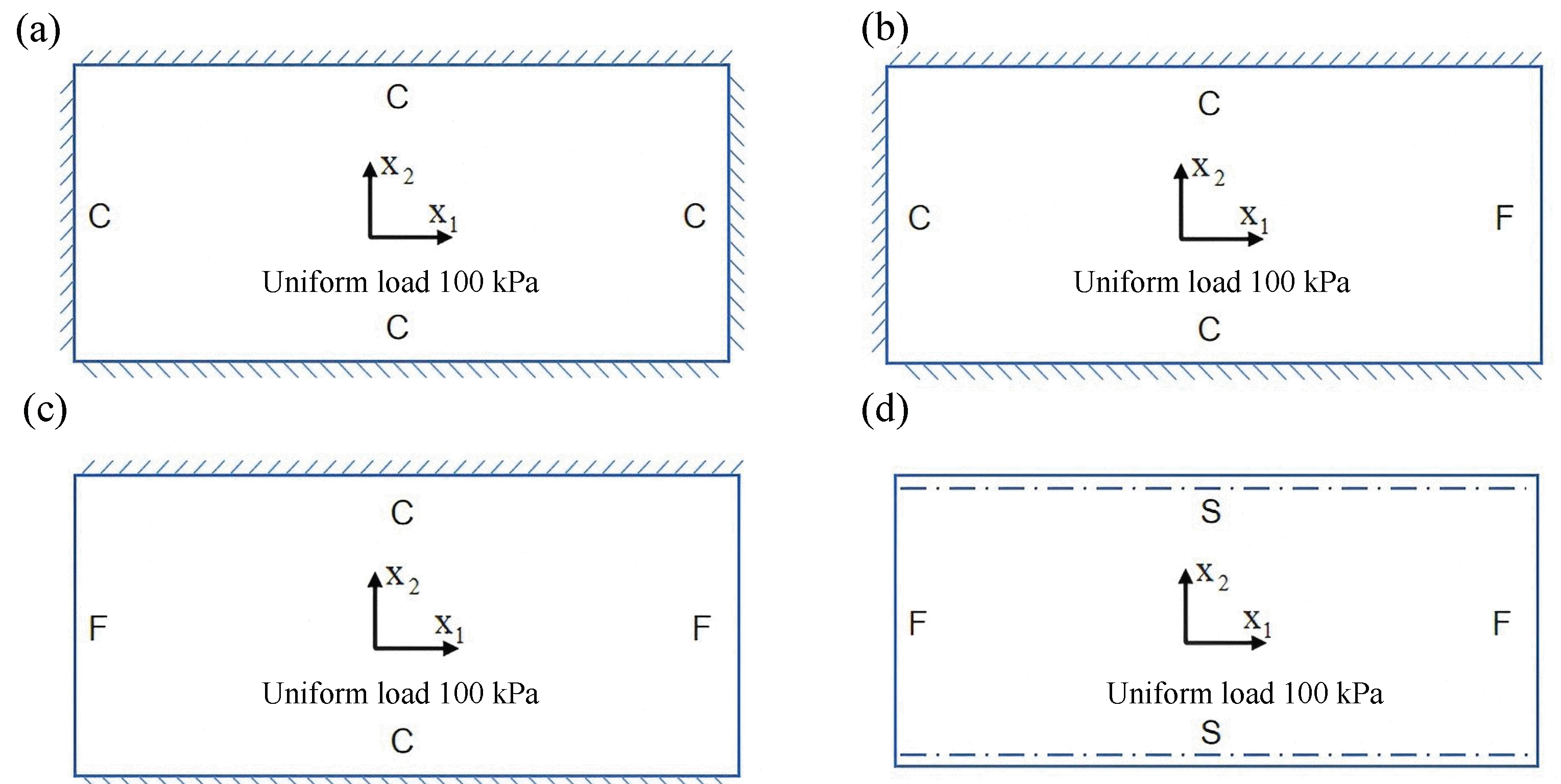

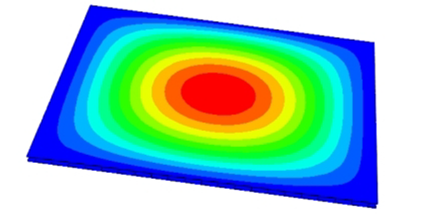

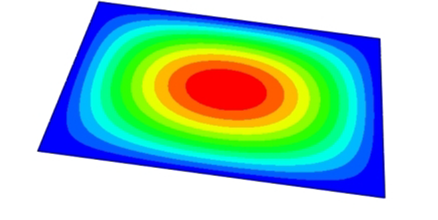

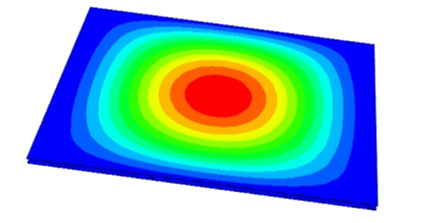

Figure 11 illustrates four typical boundary conditions used to evaluate the out-of-plane bending deformation of the SP-EHC under a uniformly distributed load. In the figure, C, S, and F represent clamped, simply supported, and free edges, respectively. Cases 5 to 8 correspond to CCCC, CCCF, CCFF, and SSFF boundary conditions, all subjected to a uniform pressure of 100 kPa with zero initial displacement. A general static analysis step was performed using the ABAQUS software to valuate the maximum displacement and overall deformation behavior of the sandwich panels.

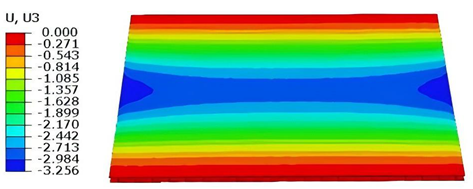

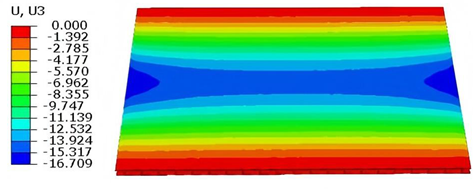

Table 4 presents the resulting displacement contours and the relative errors in maximum displacement for each case.

The analysis results reveal that maximum displacement increases progressively as boundary constraints are relaxed—from CCCC to SSFF BCs—indicating that the CCCC BCs provides the greatest out-of-plane bending stiffness, while SSFF BCs offers the least. Specifically, the maximum displacement under SSFF BCs is nearly five times greater than that under CCCC BCs. This is attributed to the lack of moment restraint in the SSFF BCs, where simply supported edges allow free rotation and bending, resulting in significantly larger deformations. Comparison of displacement contours shows strong agreement between the 3D-FEM and 2D-EPM in both deformation patterns and numerical values. The relative error in maximum displacement across all boundary conditions ranges from 2.05% to 4.15%, remaining within acceptable engineering limits. These results confirm that the 2D-EPM provides accurate and reliable predictions of the out-of-plane bending behavior of the SP-EHC under various boundary conditions.

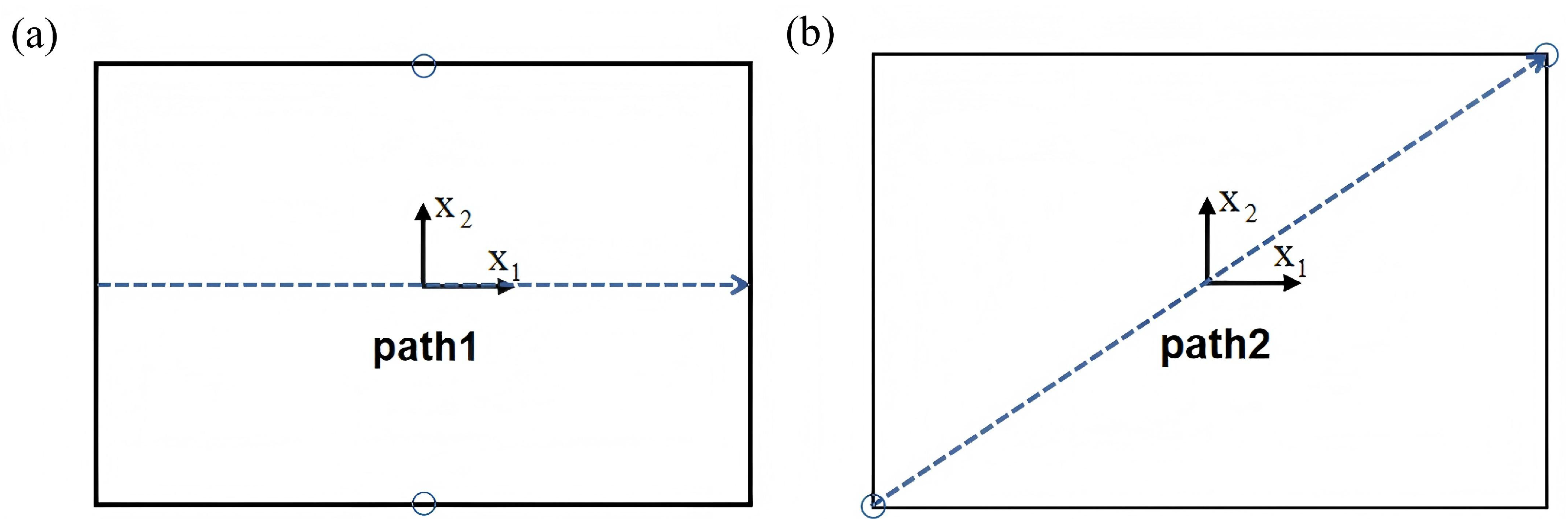

To systematically evaluate the accuracy of the 2D-EPM in predicting the out-of-plane mechanical performance of the SP-EHC, representative displacement extraction paths were designed in addition to the maximum displacement analysis. As illustrated in

Figure 12, two characteristic paths were selected for detailed evaluation. Path 1 follows the midline along the longitudinal axis of the sandwich panel, capturing deformation along the primary load-bearing direction. Path 2 extends diagonally across the panel, providing a comprehensive view of global deformation patterns under complex loading conditions.

These two paths enable systematic extraction of displacement–path distribution curves under four representative boundary conditions. This path-based analysis offers several advantages. First, comparing displacement profiles along different paths allows rigorous validation of the 2D-EPM’s ability to capture global deformation patterns, thereby reinforcing its engineering reliability. Second, the curves intuitively reveal spatial variations in deformation gradients, aiding in the detection of localized stress concentrations—critical for structural safety assessment and design refinement. Finally, the method facilitates quantitative comparison of structural responses along symmetric and asymmetric directions, enabling evaluation of the model’s capability to capture anisotropic behavior and enhancing its adaptability across diverse design requirements.

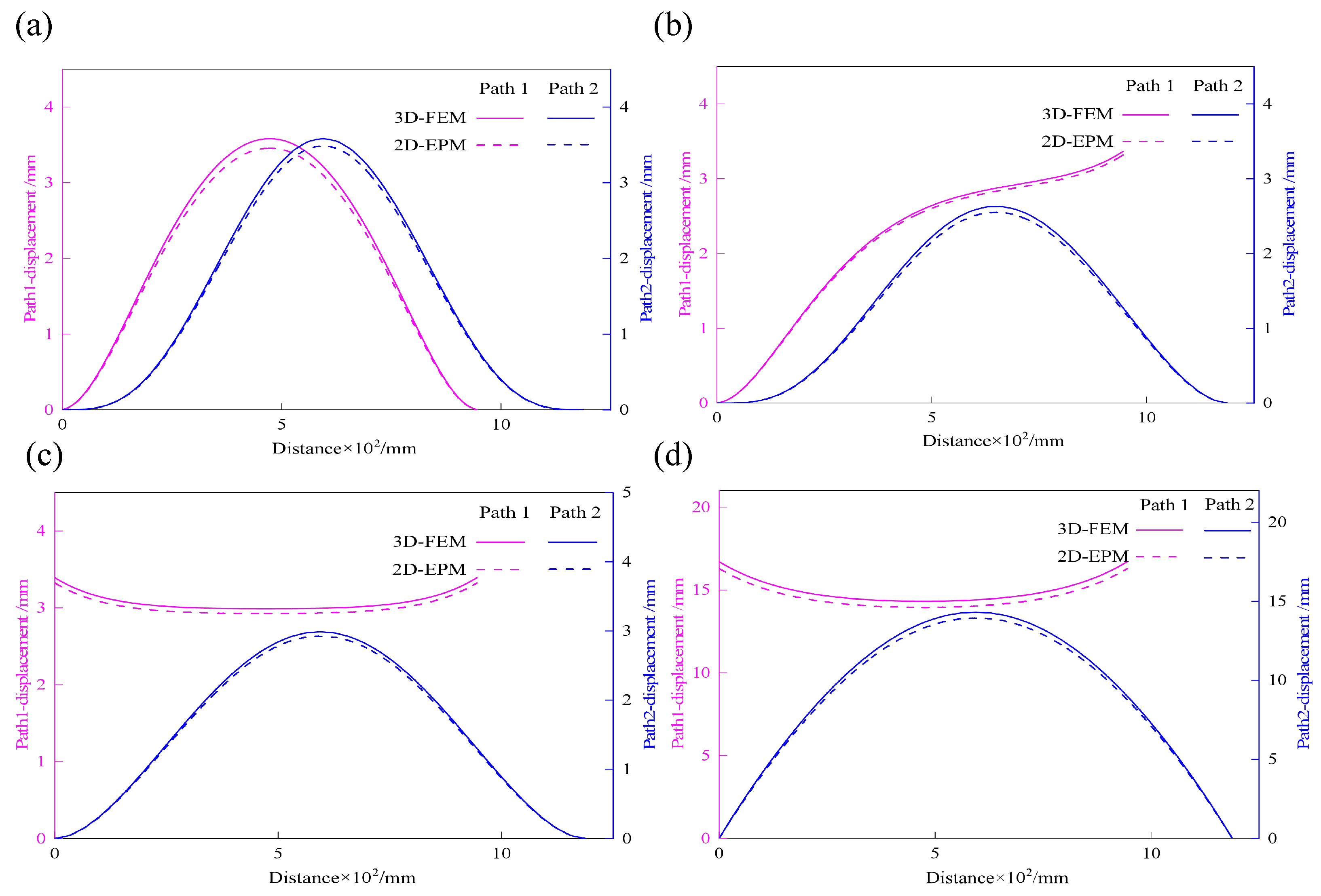

Figure 13 shows the displacement distribution curves along Path 1 and Path 2 under four representative boundary conditions, comparing results from the 3D-FEM and 2D-EPM. Analysis of the curves reveals that for Cases 5 (CCCC), 7 (CCFF), and 8 (SSFF), the displacement profiles along Path 1 exhibit pronounced symmetry in the

direction. This behavior is attributed to the centrally symmetric boundary and loading configurations, which promote a uniform deformation response. These results demonstrate that under symmetric boundary conditions, the displacement path curves effectively capture the global deformation characteristics, reinforcing the predictive accuracy of the 2D-EPM for structural behavior prediction.

In contrast, Case 6 (CCCF) exhibits clear asymmetry in the displacement distribution due to the uneven combination of clamped (C) and free (F) boundaries. The displacement curve along Path 2 shows a pronounced gradient variation, with a significantly steeper slope near the clamped edge compared to the free edge. This nonuniform deformation arises because the clamped edge fully restricts rotation, thereby limiting displacement in that region, while the free edge permits greater deformation. As a result, the displacement profile becomes asymmetric, reflecting the influence of boundary condition imbalance on structural response.

Despite the complexity of deformation patterns under asymmetric boundary conditions, the 2D-EPM accurately captures the overall trends of the displacement curves, demonstrating strong predictive capability. These results underscore the model’s robustness and adaptability in addressing complex boundary scenarios. Across all four cases, the displacement–path curves predicted by the 2D-EPM show excellent agreement with those from the 3D-FEM, with relative errors in maximum displacement remaining within acceptable engineering margins. In summary, the 2D-EPM not only reliably predicts the global out-of-plane deformation behavior of the SP-EHC but also effectively accounts for the influence of varying boundary conditions. Its consistent performance—even under complex and asymmetric configurations—establishes a solid theoretical foundation and provides valuable support for structural analysis and engineering design.

4.4. Out-of-Plane Bending Analysis with Initial Displacement

In practical engineering applications, structural components rarely conform to the idealized assumptions of perfect initial geometry. Sandwich panels, in particular, are susceptible to initial displacements or geometric imperfections introduced during manufacturing, transportation, and installation. These imperfections may arise from fabrication errors, material inhomogeneities, environmental factors such as temperature and humidity fluctuations, or external disturbances during handling and assembly. Such geometric deviations, present before the panel enters service, can significantly influence its mechanical response under out-of-plane loading. This effect is especially pronounced in thin-walled or lightweight structures, where even minor imperfections can reduce load-carrying capacity, trigger premature buckling, or induce localized instability.

To more accurately simulate real-world service conditions, this section incorporates initial geometric imperfections into the out-of-plane loading analysis of the SP-EHC under CCFF boundary conditions. These imperfections account for practical factors such as manufacturing deviations and residual stresses, which are commonly encountered in engineering applications. More importantly, the analysis captures the structure’s nonlinear response and potential stability issues under out-of-plane loading, providing valuable insights for the optimization and safety evaluation of sandwich panel designs. A systematic numerical investigation was conducted by introducing prescribed initial displacements of varying amplitudes into the model to evaluate their influence on the transverse load-bearing behavior and ultimate strength of the structure. The simulation procedure is illustrated in

Figure 14, where

and

denote the imposed initial displacement amplitudes along the

and

directions, respectively. The range of initial imperfections considered includes:

, and

.

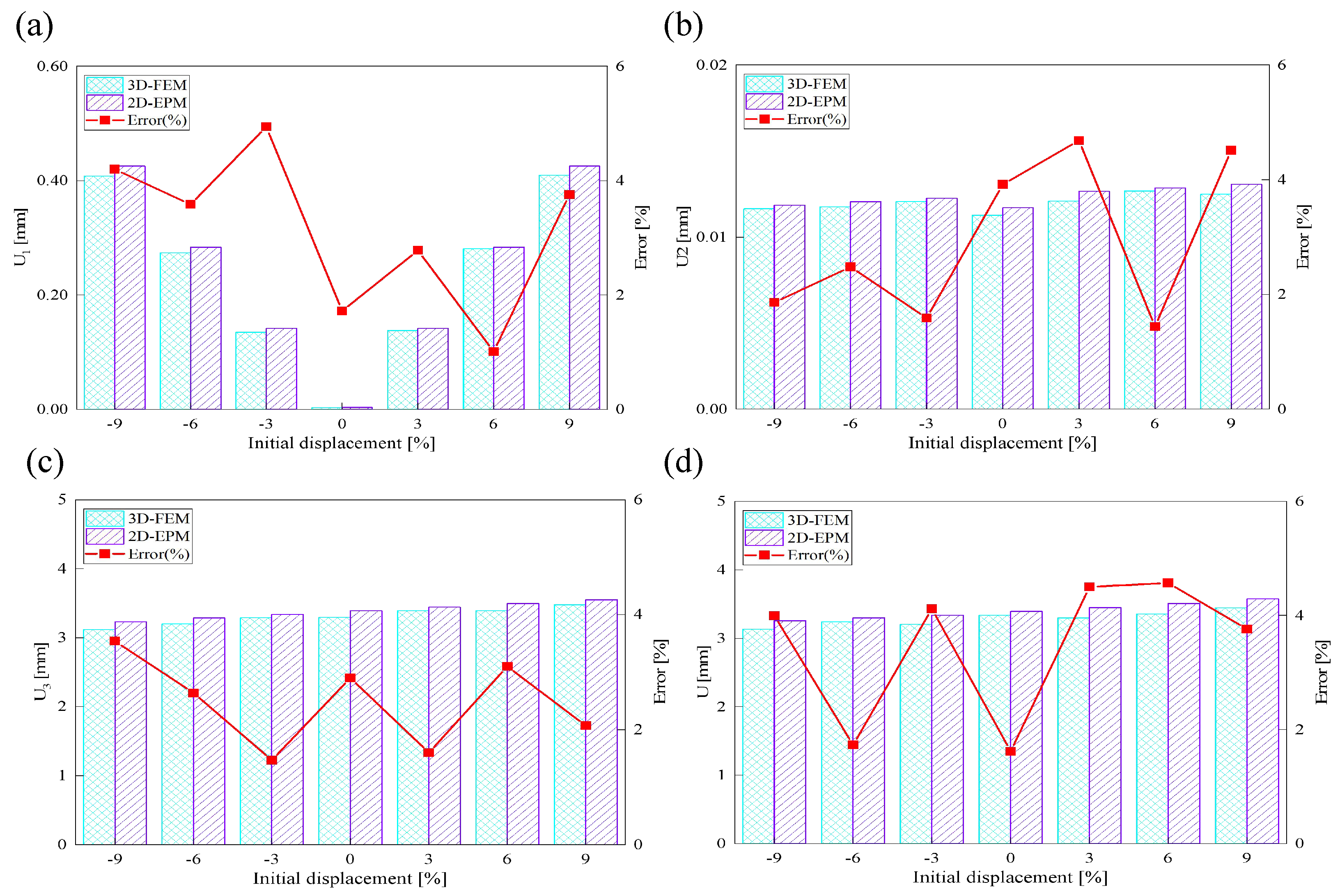

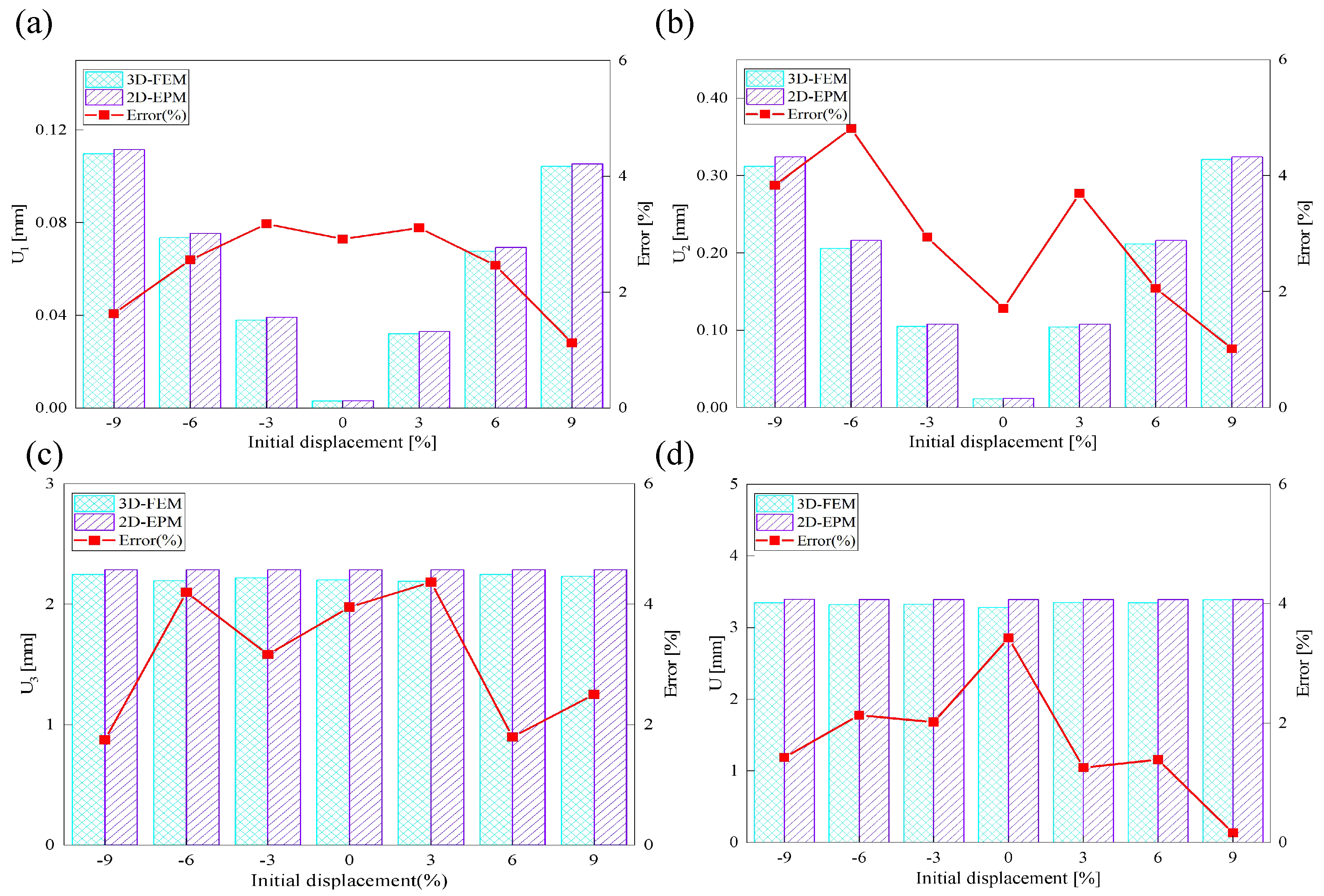

Figure 15 illustrates the influence of initial deformation along the

direction on the displacement response of the SP-EHC under CCFF boundary conditions. As the initial deformation amplitude increases from -9% to 9%, the total displacement of the SP-EHC exhibits a progressive upward trend. Among the three displacement components,

exhibits a nonlinear response: it first decreases and then increases with varying initial deformation. Notably, at zero imperfection (0%),

is nearly zero, indicating that displacement in this direction is primarily load-induced, with minimal contribution from geometric imperfections. Furthermore, introducing moderate compressive deformation in the -

direction reduces the out-of-plane displacement component

, effectively enhancing the panel’s out-of-plane stiffness.

Figure 16 illustrates the influence of initial deformation along the

direction on the displacement components in all three coordinate directions. As the initial deformation varies from -9% to 9%, the total displacement initially decreases and then increases, though the overall variation remains relatively small. For individual components,

reaches a minimum at zero imperfection and increases with greater initial deformation, indicating a clear positive correlation. A similar trend is observed for

, indicating that in-plane displacements in both directions are sensitive to initial geometric imperfections. In contrast,

remains relatively stable throughout the deformation range, implying that imperfections in the

direction have minimal impact on the out-of-plane displacement response.

In summary, the SP-EHC under CCFF boundary conditions exhibits notable sensitivity to initial geometric imperfections. Disturbances along the and directions significantly affect the in-plane displacement components ( and ), while their effects on the out-of-plane component () are direction-dependent. Specifically, compressive deformation along the axis contributes to a reduction in , whereas deformation along the axis has negligible impact. These findings offer important guidance for controlling initial imperfections and optimizing the stability design of sandwich panels.

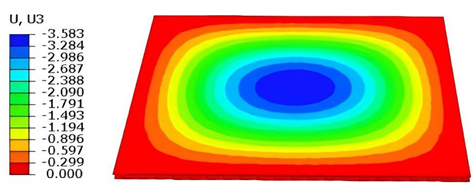

4.5. Local Field Recovery

Local field reconstruction is an effective approach for accurately evaluating localized structural performance and informing targeted design optimizations. By enabling precise adjustments to structural configurations or material distributions, this method enhances the strength and stiffness of critical regions, thereby improving overall system reliability and stability. Compared to global response analysis, local field reconstruction offers higher spatial resolution and predictive accuracy, making it particularly well-suited for capturing localized stress, strain, and displacement fields in complex structures such as SP-EHC.

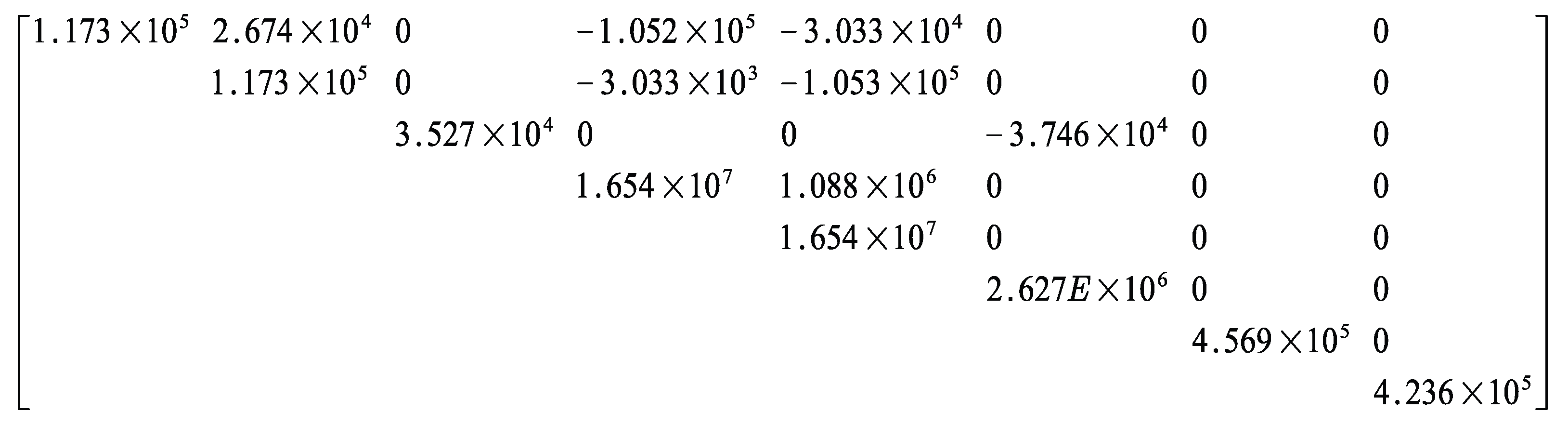

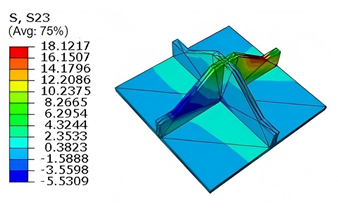

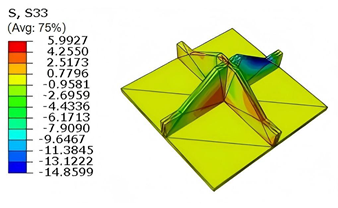

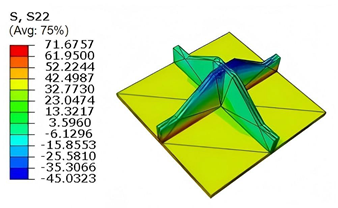

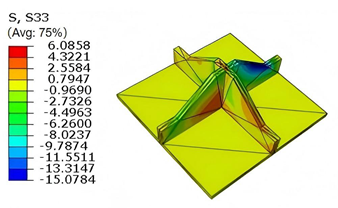

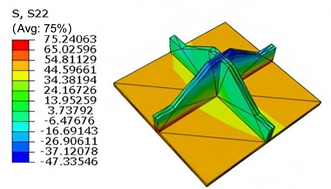

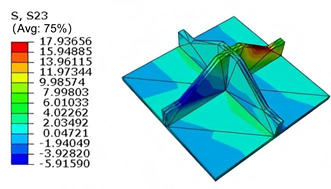

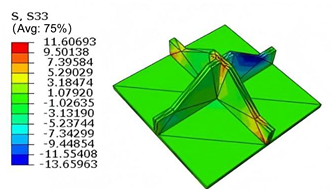

In this section, local field reconstruction is conducted for two representative cases: (1) Case 3 without initial deformation and clamped (CCCC) boundary conditions; and (2) Case 3 with 9% initial deformation along the -axis. By comparing the localized stress and displacement fields predicted by the 2D-EPM with those obtained from 3D-FEM, the accuracy and applicability of the dimensional reduction method in reconstructing local fields are systematically evaluated.

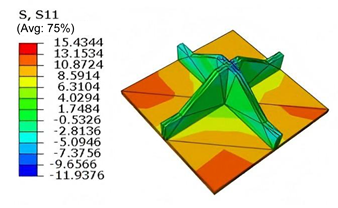

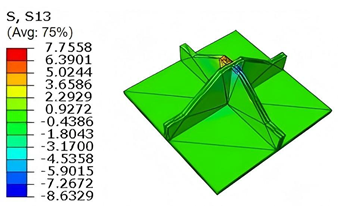

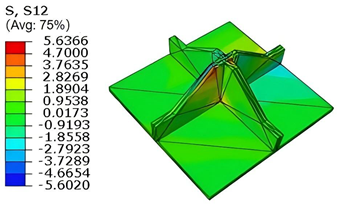

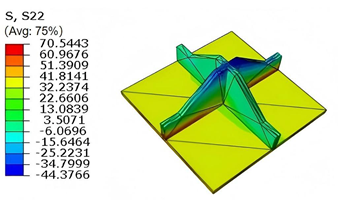

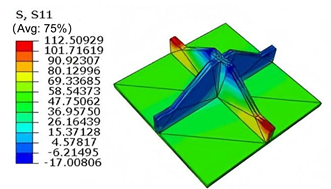

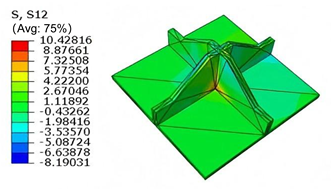

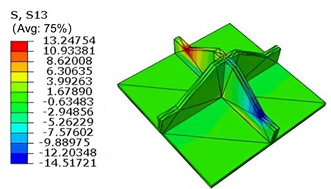

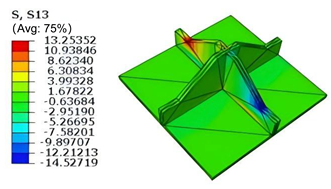

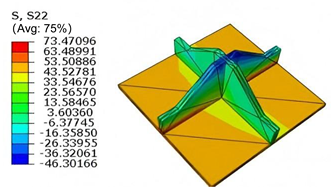

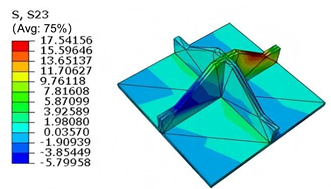

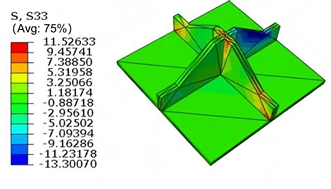

Table 5 compares the local stress field distributions within the central cell of the panel in Case 3, as predicted by 3D-FEM and 2D-EPM. The results indicate that the normal bending stresses (

and

) are primarily concentrated in the bottom face sheet and at the face sheet–core interface, with the maximum tensile stress reaching 71.676 MPa. This stress concentration is likely caused by pronounced bending deformation in the overhanging region, driven by geometric features and external loading. The coupling between face sheet bending and core shear deformation further amplifies this localized stress.

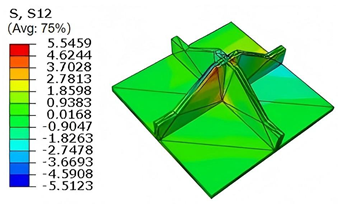

The shear stresses (, , and ) are primarily distributed along the cell walls of the core in the -direction, with a maximum value of 18.372 MPa. Due to the high stiffness and small thickness of the face sheets, they predominantly resist bending, while the core layer bears the majority of the shear load. The observed stress heterogeneity highlights the strong coupling between load transfer and internal structure within the sandwich panel. Notably, shear stresses accumulate near the center of the face–core interface. In combination with elevated shear stresses, this significantly increases the risk of interfacial delamination. Comparison of the local stress contours reveals strong agreement between the 2D-EPM and 3D-FEM predictions, with a maximum relative error of only 1.641%. This confirms the accuracy and effectiveness of the equivalent model in capturing localized stress field behavior.

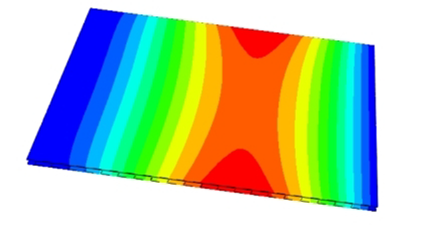

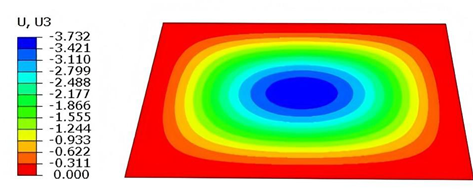

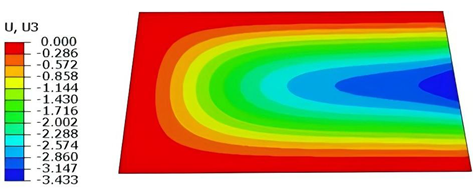

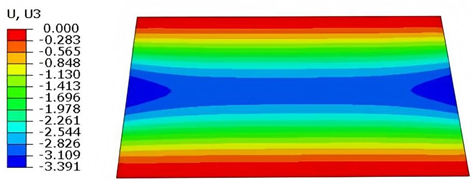

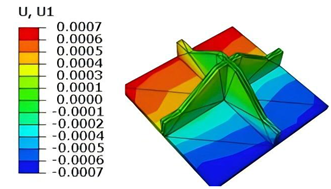

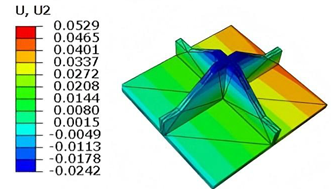

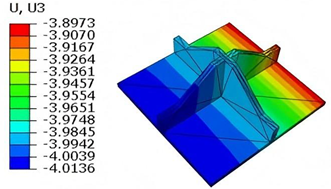

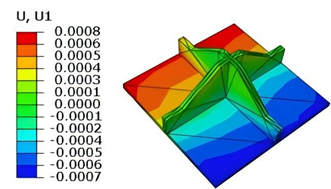

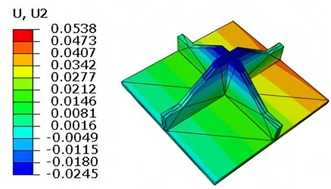

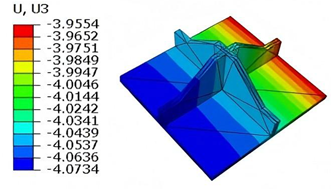

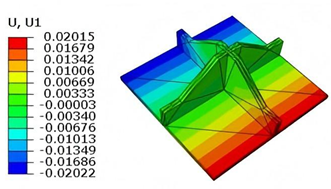

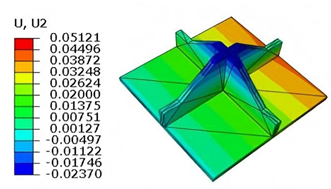

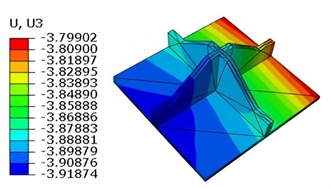

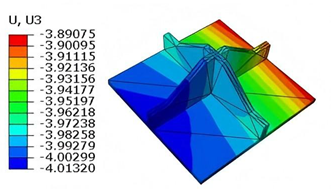

Table 6 compares the local displacement field distributions obtained from 3D-FEM and 2D-EPM. The results reveal a pronounced displacement concentration at the face–core interface, attributed to the modulus gradient between the face sheets and the core, with the core exhibiting significantly lower stiffness. Under out-of-plane loading, the displacement distribution displays clear biaxial symmetry, consistent with the geometric symmetry of the unit cell and the applied boundary conditions. Notably, the displacement along the

-direction is concentrated within the face sheet, while the displacement along the

-direction is concentrated near the face sheet-core interface. This behavior is attributed to the stiffness contrast between the constituent materials and the applied loading conditions. The high-stiffness face sheets dominate the deformation response along the

-axis, whereas the softer core material experiences greater displacement along the

-axis—particularly near the face–core interface—due to local stress concentrations induced by the mismatch in material stiffness.

The out-of-plane displacement component shows a red-shifted region in the contour map skewed toward the cell wall of unit cell. This asymmetry results from stress redistribution caused by the free boundary condition in Case 3: the lack of constraint in the -direction allows the cell wall to bear a larger portion of the lateral load. Quantitative comparison of the reconstructed displacement fields (, , ) shows that the average relative errors of the 2D-EPM with respect to the 3D-FEM reference are 2.7%, 1.7%, and 1.5%, respectively. These results confirm the accuracy and applicability of the proposed dimensional reduction approach in capturing localized bending behavior of sandwich panels.

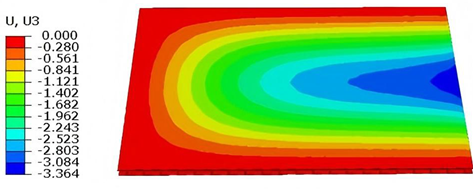

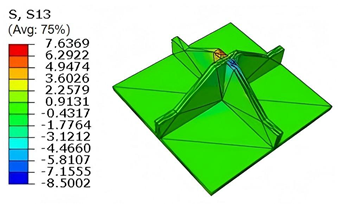

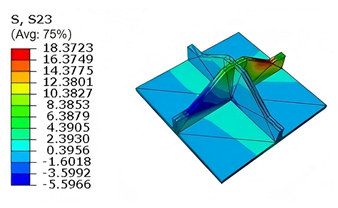

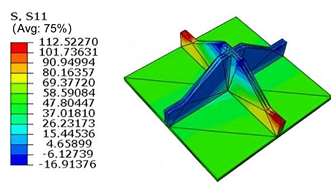

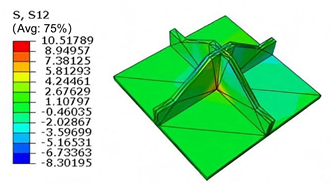

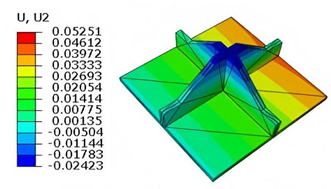

Table 7 compares the local stress fields within the central cell of the panel under the CCFF boundary condition (Case 3), with an applied initial displacement of 9%. Compared with the results in

Table 6, the normal stress

increases by nearly an order of magnitude, while

remains unchanged. This indicates that the imposed initial displacement in the

-direction significantly amplifies

, primarily due to the lack of constraint along this direction. The resulting tensile force induced by the initial imperfection leads to elevated stress concentrations.

Moreover, high tensile stress is observed along the upper outer arm in the -direction, especially at the interface with adjacent unit cells, indicating a critical region for stress transmission. The combined effects of out-of-plane loading and initial geometric imperfection leads to stress concentration in this area. Shear stresses and also increase significantly—by approximately an order of magnitude—while remains unchanged. This behavior may result from structural distortion near the boundary induced by the initial displacement, leading to a redistribution of internal forces. Under out-of-plane loading, the amplified local deformation intensifies both stress concentration and shear effects in this region.

Furthermore, the altered geometry introduces discontinuities in local boundary conditions, exacerbating shear stress gradients near the edges. Consequently, structural deformation and stress redistribution propagate inward from the boundaries, further intensifying the shear response. These findings highlight the importance of accounting for initial imperfections in structural core design. For cores susceptible to manufacturing or assembly defects, particular attention should be given to the strength and stiffness at key constraint regions—especially near interface boundaries and bonding lines—to mitigate stress concentrations and deformation amplification induced by initial displacements.

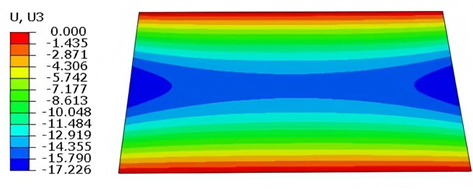

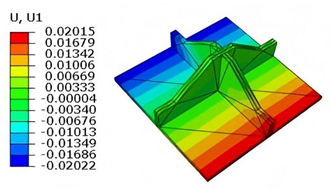

Table 8 compares the local displacement fields within the unit cell located at the same position under CCFF boundary condition (Case 3) with imposed initial displacement of 0.9%. By comparing these results with those in

Table 6 and the corresponding displacement contours, several key observations emerge:

exhibits a notable increase,

shows a slight rise, while

exhibits a slight reduction. This suggests that the influence of initial geometric imperfection exceeds that of out-of-plane loading, resulting in a decrease in

compared to the perfect, unperturbed structure.

Therefore, the impact of initial geometric imperfections must be carefully considered in the design of sandwich panels. Reinforcing or modifying regions susceptible to such defects is recommended to mitigate their adverse effects. In particular, local stiffening along directions with pronounced imperfections can help reduce displacement concentrations and enhance overall structural robustness.