Submitted:

19 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Digital Twins: From Conceptual Models to Operational Systems

2.1. Digital Twins and Artificial Intelligence

2.2. Ontologies: illuminating Artificial Intelligence

2.3. Towards the Cognitive Heritage Digital Twins

3. In Pursuit of Knowledge

3.1. Retrieving and Reusing Cultural Knowledge

3.2. Natural Language Processing of Textual Documentation

- Language is inherently ambiguous at all levels: lexical, semantic, and syntactic. While humans typically overcome this obstacle through contextual knowledge, computers often struggle to correctly grasp meaning, as context is frequently unspoken or culturally assumed

- Language is heavily context-dependent

- Language is creative: people frequently invent new words and phrases, and this process is always ongoing and can be virtually infinite

- Language is often ironic and metaphorical, making it difficult for computers to detect when meaning deviates from the literal or usual one

- Humans regularly leave information out, assuming the listener will infer it; however, computers often struggle with anaphora resolution and implicit references

- Named Entity Recognition

- Semantic Enrichment

- Machine-assisted transcription

- Cross-document linking

3.3. Computer Vision and AI for Image Analysis

- Semantic image retrieval across museum collections and digitized archives using natural language queries

- Automated captioning and metadata enrichment for unlabeled or poorly documented objects

- Cross-modal linking of visual and textual materials, such as aligning illustrations with manuscript passages or inscriptions with OCR outputs

- Clustering of visual-textual artefacts to detect stylistic, thematic, or geographic patterns

3.4. Identification and Semantic Extraction of Relevant Entities and Relationships

4. From Fragments to Knowledge

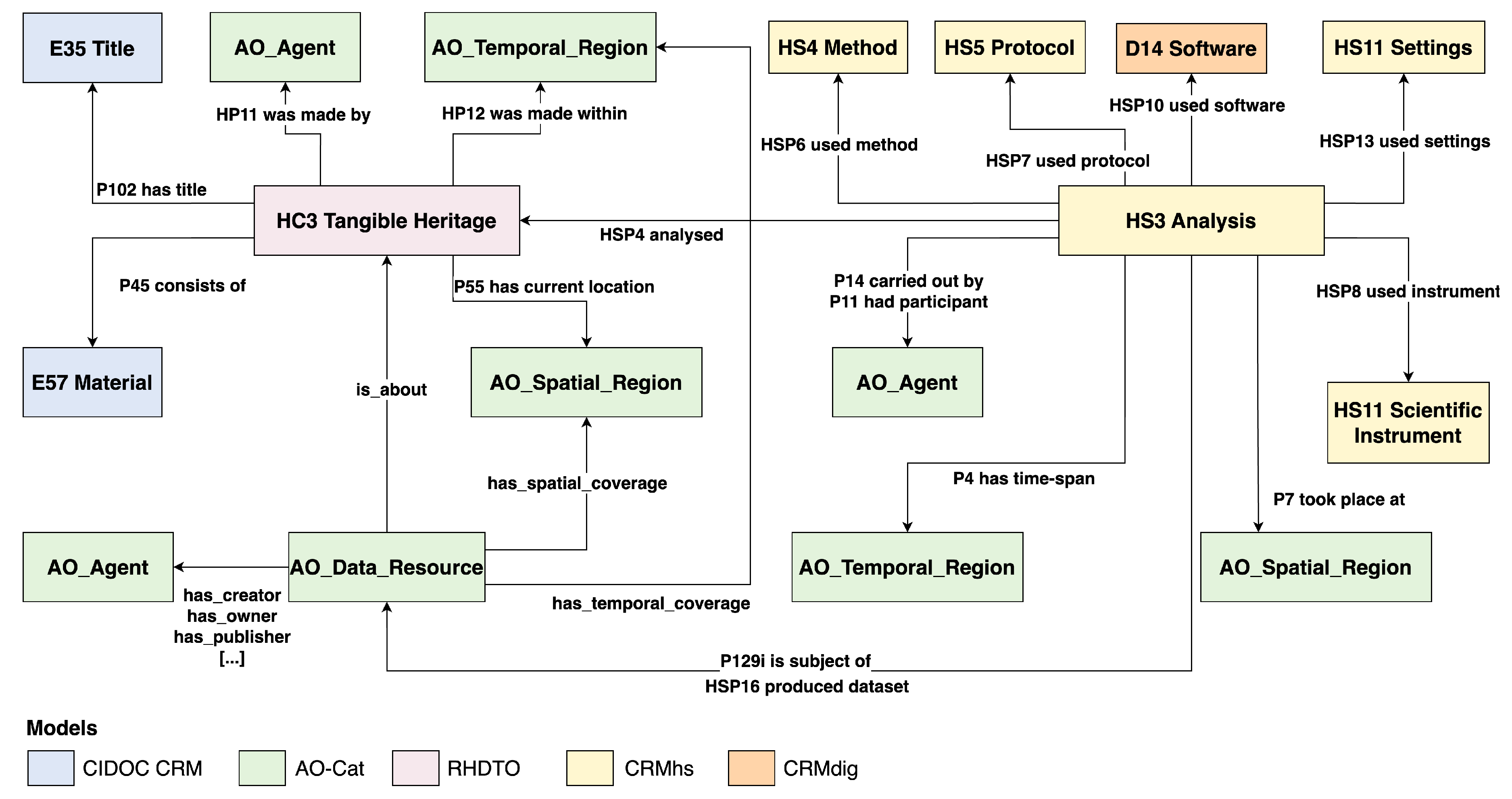

4.1. Ontological Modelling of Extracted Information

4.2. Ontologies for Building Knowledge Graphs Ecosystems

5. From Knowledge to Intelligence

5.1. Using Knowledge Graphs to Build Knowledge-Enriched AI Agents

5.2. Implementing Feedback Loops for Continuous AI Models Improvement

6. Natural Language Access and Prompt Interfaces

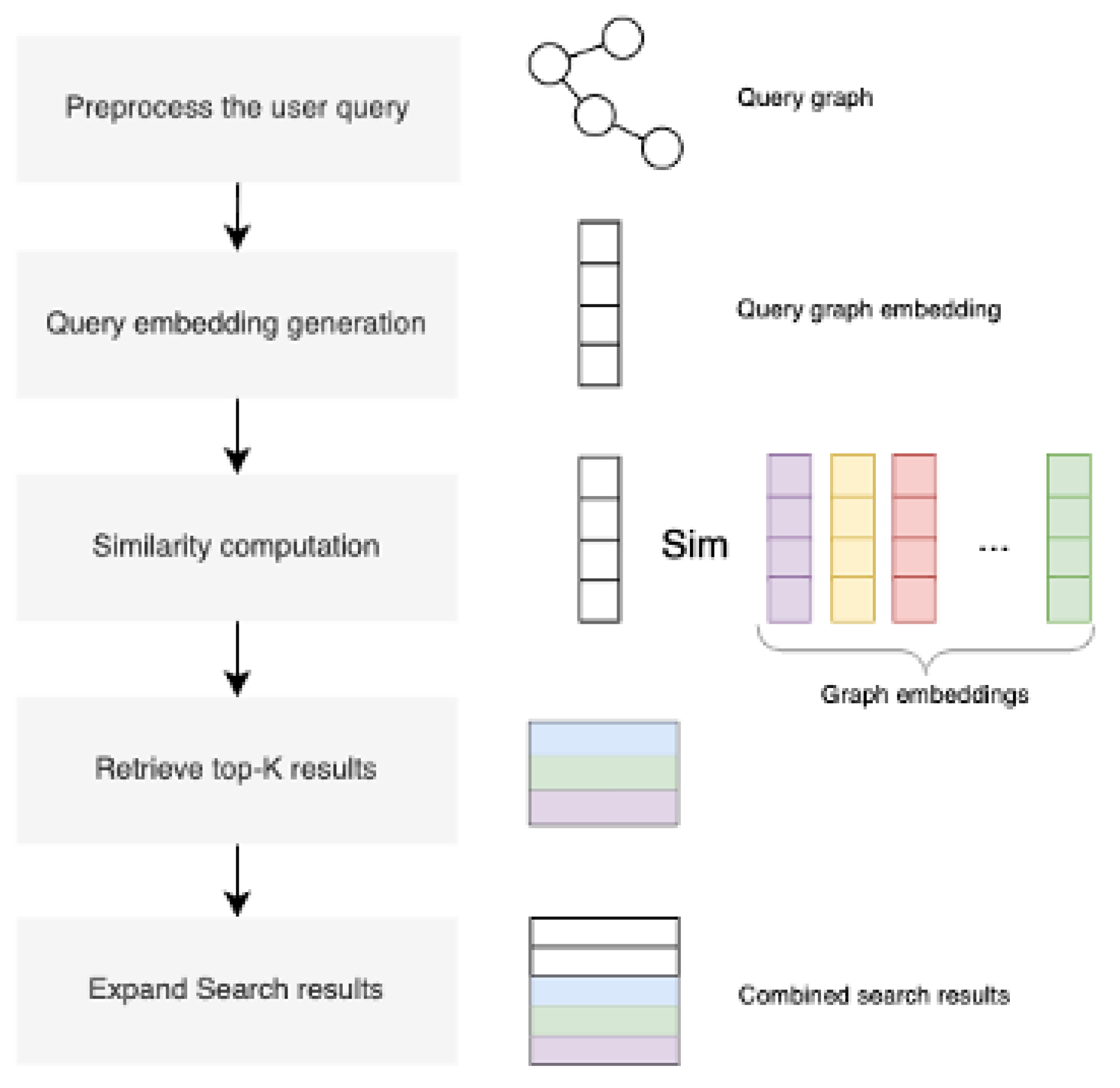

6.1. Similarity Computation in the Context of the HDT

- Pieces that belong to same object

- Different objects that were excavated at the same site but from different locations

- Different objects that were crafted in the same workshop

- Different objects made of material originating from the same place; inferred from the data of scientific analysis reports

- Different objects made by the same artist

6.2. Design and Implementation of Prompt-Based Interfaces

6.3. Presenting Complex Query Results in User-Comprehensible Formats

7. Case Study: Enriching Digital Twins with Heritage Science Data

7.1. Application of AI-Driven Semantic Pipelines

- Tokenization

- Sentence Segmentation

- Syntactic Parsing

- A validated list of ontology-relevant terms, stored in JSON format

- A collection of RDF triples, structured and domain ontology-aligned

- A mapping between each term and its original context, ensuring interpretability and traceability

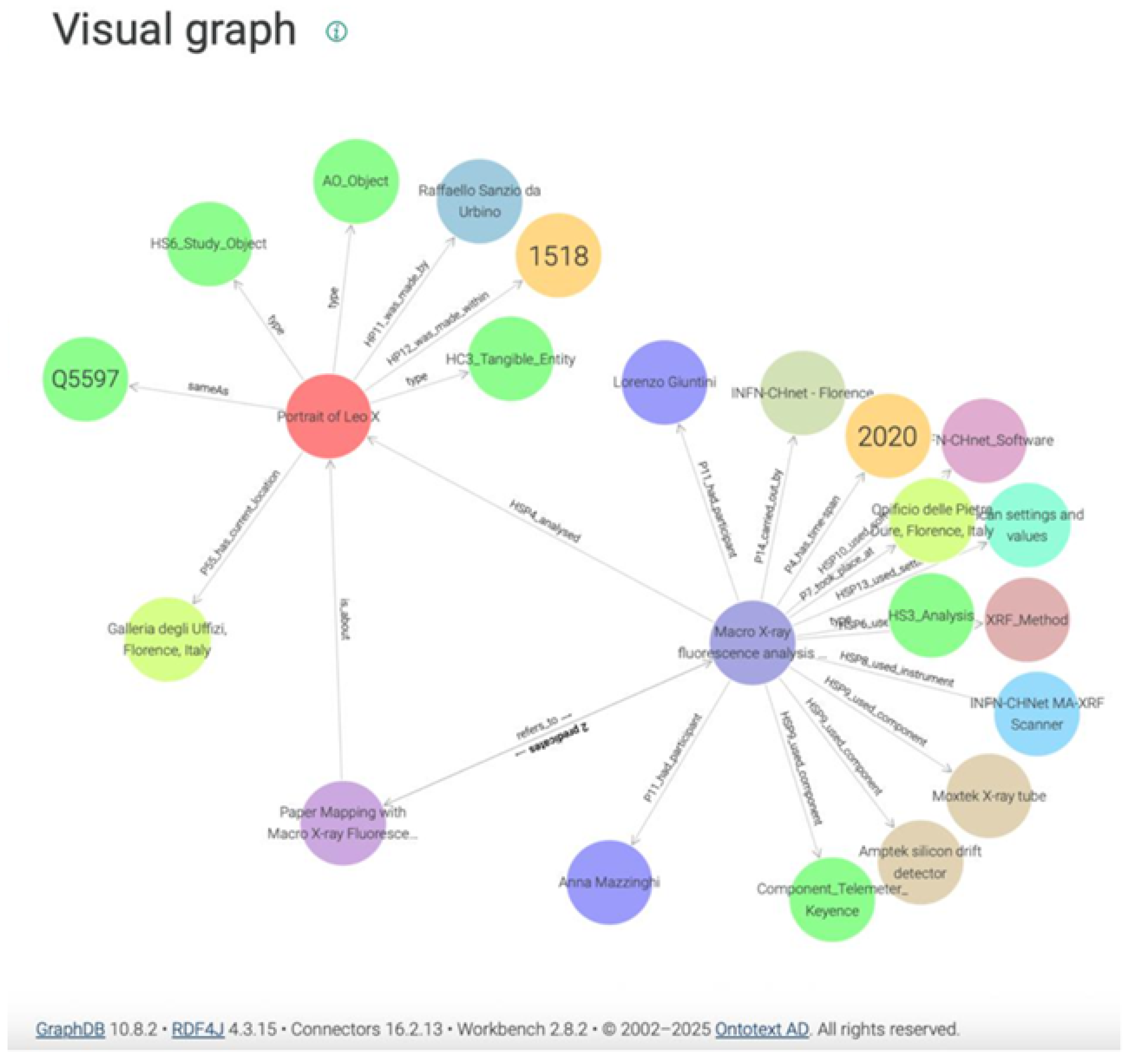

7.2. Populating and Querying the ARTEMIS Knowledge Graph

8. Discussion: Taming the Wild Beast

8.1. The Indispensable Role of Human Expertise in AI-Assisted Processes

8.2. Ethical Implications and the Pursuit of Transparent AI in Cultural Heritage

9. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, D.; Snider, C.; Nassehi, A.; Yon, J.; Hicks, B. Characterising the Digital Twin: A systematic literature review. CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology 2020, 29, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, C.; Lezoche, M.; Panetto, H.; Dassisti, M. Digital twin paradigm: A systematic literature review. Computers in Industry 2021, 130, 103469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrotter, G.; Hürzeler, C. The Digital Twin of the City of Zurich for Urban Planning. PFG – Journal of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Geoinformation Science 2020, 88, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprari, G.; Castelli, G.; Montuori, M.; Camardelli, M.; Malvezzi, R. Digital Twin for Urban Planning in the Green Deal Era: A State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. , Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems: New Findings and Approaches; Kahlen, F.J., Flumerfelt, S., Alves, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Aslam, S.; Wileman, A.; Perinpanayagam, S. Digital Twin in Aerospace Industry: A Gentle Introduction. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 9543–9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Viquez, D.; Zamora-Hernandez, M.; Fernandez-Vega, M.; Garcia-Rodriguez, J.; Azorin-Lopez, J. A Comprehensive Review of AI-Based Digital Twin Applications in Manufacturing: Integration Across Operator, Product, and Process Dimensions. Electronics 2025, 14, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, L.J.; Davies, R.J.; Hunt, D.V.L. The Application of Historic Building Information Modelling (HBIM) to Cultural Heritage: A Review. Heritage 2023, 6, 6691–6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, L.; Ruston McAleer, S.; Croket, I.; Kogut, P.; Brynskov, M.; Lefever, S. (Eds.) Decide Better: Open and Interoperable Local Digital Twins; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazoglou, M.P.; Krämer, B.J.; Raheem, M.; Elgammal, A. Medical Digital Twins for Personalized Chronic Care, 2025. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Destination Earth. Available online: https://destination-earth.eu. (accessed on day month year).

- Nikolinakos, N.T. EU Policy and Legal Framework for Artificial Intelligence, Robotics and Related Technologies - the AI Act, 1st ed ed.; Number v.53 in Law, Governance and Technology Series; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Grieves, M. Digital Twin: Manufacturing Excellence through Virtual Factory Replication 2014.

- Fuller, A.; Fan, Z.; Day, C.; Barlow, C. Digital Twin: Enabling Technologies, Challenges and Open Research. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 108952–108971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.; Greif, L.; Häußermann, T.M.; Otto, S.; Kastner, K.; El Bobbou, S.; Chardonnet, J.R.; Reichwald, J.; Fleischer, J.; Ovtcharova, J. Digital Twins, Extended Reality, and Artificial Intelligence in Manufacturing Reconfiguration: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roopa, M.S.; Venugopal, K.R. Digital Twins for Cyber-Physical Healthcare Systems: Architecture, Requirements, Systematic Analysis, and Future Prospects. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 44963–44996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalabidis, Y.; Kontos, G.; Zitianellis, D. Local Digital Twins for Cities and Regions: The Way Forward. In Decide Better: Open and Interoperable Local Digital Twins; Raes, L., Ruston McAleer, S., Croket, I., Kogut, P., Brynskov, M., Lefever, S., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025; pp. 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampère, C.; Ortmann, P.; Jedlička, K.; Lohman, W.; Janssen, S. Future Ready Local Digital Twins and the Use of Predictive Simulations: The Case of Traffic and Traffic Impact Modelling. In Decide Better: Open and Interoperable Local Digital Twins; Raes, L., Ruston McAleer, S., Croket, I., Kogut, P., Brynskov, M., Lefever, S., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025; pp. 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsalan, H.; Heesom, D.; Moore, N. From Heritage Building Information Modelling Towards an ‘Echo-Based’ Heritage Digital Twin. Heritage 2025, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niccolucci, F.; Felicetti, A. Digital Twin Sensors in Cultural Heritage Ontology Applications. Sensors 2024, 24, 3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Fuenmayor, E.; Hinchy, E.; Qiao, Y.; Murray, N.; Devine, D. Digital Twin: Origin to Future. Applied System Innovation 2021, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipnitz, M.T.; Petry, R.H.; Rodrigues, F.H.; De Souza Silva, H.R.; Correia, J.B.; Becker, K.; Wickboldt, J.A.; Carbonera, J.L.; Netto, J.C.; Abel, M. Architecting Digital Twins: From Concept to Reality. Procedia Computer Science 2025, 256, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, M.M.; Shah, S.A.; Shukla, D.; Bentafat, E.; Bakiras, S. The Role of AI, Machine Learning, and Big Data in Digital Twinning: A Systematic Literature Review, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 32030–32052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boje, C.; Guerriero, A.; Kubicki, S.; Rezgui, Y. Towards a semantic Construction Digital Twin: Directions for future research. Automation in Construction 2020, 114, 103179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, E.; Pileggi, S.F.; Groth, P.; Degeler, V. Ontologies in digital twins: A systematic literature review. Future Generation Computer Systems 2024, 153, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XMLPO: An Ontology for Explainable Machine Learning Pipeline. In Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications; IOS Press. 2024; ISSN 0922-6389. [CrossRef]

- Semantic Data-Modeling and Long-Term Interpretability of Cultural Heritage Data—Three Case Studies. Digital Cultural Heritage; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niccolucci, F.; Felicetti, A.; Hermon, S. Populating the Data Space for Cultural Heritage with Heritage Digital Twins. Data 2022, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niccolucci, F.; Markhoff, B.; Theodoridou, M.; Felicetti, A.; Hermon, S. The Heritage Digital Twin: a bicycle made for two. The integration of digital methodologies into cultural heritage research. Open Research Europe 2023, 3, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicetti, A.; Meghini, C.; Richards, J.; Theodoridou, M. The AO-Cat Ontology. Technical report, Zenodo, 2025. Version Number: 1.2. [CrossRef]

- Alammar, J.; Grootendorst, M. Hands-on large language models: language understanding and generation, first edition ed.; O’Reilly Media, Inc: Sebastopol, CA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y. A damage detection network for ancient murals via multi-scale boundary and region feature fusion. npj Heritage Science 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, C.; Posthumus, E.; Tan, M.A.; Bruns, O.; Tietz, T.; Sack, H. Multimodal Search on Iconclass using Vision-Language Pre-Trained Models, 2023. Version Number: 1. [CrossRef]

- Detecting and Deciphering Damaged Medieval Armenian Inscriptions Using YOLO and Vision Transformers. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 22–36, ISSN: 0302-9743, 1611-3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision, 2021. Version Number: 1,. [CrossRef]

- Cherti, M.; Beaumont, R.; Wightman, R.; Wortsman, M.; Ilharco, G.; Gordon, C.; Schuhmann, C.; Schmidt, L.; Jitsev, J. Reproducible Scaling Laws for Contrastive Language-Image Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada; 2023; pp. 2818–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIDOC CRM. Available online: https://cidoc-crm.org. (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- CRMsci - Scientific Observation Model. Available online: https://cidoc-crm.org/crmsci. (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- CRMdig - Model for Provenance Metadata. Available online: https://https://cidoc-crm.org/crmdig. (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Felicetti, A.; Niccolucci, F. Artificial Intelligence and Ontologies for the Management of Heritage Digital Twins Data. Data 2024, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fensel, D.; Şimşek, U.; Angele, K.; Huaman, E.; Kärle, E.; Panasiuk, O.; Toma, I.; Umbrich, J.; Wahler, A. How to Build a Knowledge Graph. In Knowledge Graphs: Methodology, Tools and Selected Use Cases; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 11–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maree, M. Quantifying Relational Exploration in Cultural Heritage Knowledge Graphs with LLMs: A Neuro-Symbolic Approach for Enhanced Knowledge Discovery. Data 2025, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, O. The Persistence of Temporality: Representation of Time in Cultural Heritage Knowledge Graphs. ISWC 2023 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Faralli, S.; Lenzi, A.; Velardi, P. A Large Interlinked Knowledge Graph of the Italian Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the LREC; 2022; pp. 6280–6289. [Google Scholar]

- Carriero, V.A.; Gangemi, A.; Mancinelli, M.L.; et al. ArCo: the Italian Cultural Heritage Knowledge Graph. arXiv, 2019; arXiv:1905.02840. [Google Scholar]

- Barzaghi, S.; Moretti, A.; Heibi, I.; Peroni, S. CHAD-KG: A Knowledge Graph for Representing Cultural Heritage Objects and Digitisation Paradata. arXiv, 2025; arXiv:2505.13276. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding, 2018. Version Number: 2. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners, 2020, Version Number: 4. [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models, 2023. Version Number: 1. [CrossRef]

- Gekhman, Z.; Yona, G.; Aharoni, R.; Eyal, M.; Feder, A.; Reichart, R.; Herzig, J. Does Fine-Tuning LLMs on New Knowledge Encourage Hallucinations?, 2024. Version Number: 3. [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Luo, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Wu, X. Unifying Large Language Models and Knowledge Graphs: A Roadmap. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2024, 36, 3580–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Suzgun, M.; Mackey, L.; Kalai, A.T. Do Language Models Know When They’re Hallucinating References?, 2023. Version Number: 3. [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; He, Y.; Ding, Z.; Hooi, B. Can Knowledge Graphs Make Large Language Models More Trustworthy? An Empirical Study Over Open-ended Question Answering, 2025. arXiv:2410.08085 [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Du, Z.; Chen, Y. Knowledge Graph Tuning: Real-time Large Language Model Personalization based on Human Feedback, 2024. arXiv:2405.19686 [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Qiao, S.; Ou, Y.; Yao, Y.; Deng, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, N. LLMs for Knowledge Graph Construction and Reasoning: Recent Capabilities and Future Opportunities, 2024. arXiv:2305.13168 [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Meronyo Pen̆uela, A.; Simperl, E. Towards Explainable Automatic Knowledge Graph Construction with Human-in-the-loop. Semantic Web Journal 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor, E.; Tong, J.; Vijayaraghavan, S.; Li, R. Expanding Knowledge Graphs with Humans in the Loop. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2212.05189. [Google Scholar]

- Meroño-Peñuela, A.; Sack, H. Move Cultural Heritage Knowledge Graphs in Everyone’s Pocket. Semantic Web Journal 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, B.; et al. Knowledge Graph-Based Intelligent Question Answering System for Ancient Chinese Costume Heritage. npj Heritage Science 2025, 13, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yu, S.; Chu, J.; Fan, H.; Du, B. Using Knowledge Graphs and Deep Learning Algorithms to Enhance Digital Cultural Heritage Management. Heritage Science 2023, 11, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Pan, S.; Cambria, E.; Marttinen, P.; Yu, P.S. A Survey on Knowledge Graphs: Representation, Acquisition, and Applications. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, e.a. Injecting Knowledge Graphs into Large Language Models. arXiv, 2025; arXiv:2505.07554 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, F.; Zhang, W. SparqLLM: Natural Language Querying of Knowledge Graphs via Retrieval-Augmented Generation. arXiv; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Cui, Z.; Wang, B.; Pan, S.; Gao, J.; Yin, B.; Gao, W. IME: Integrating Multi-curvature Shared and Specific Embedding for Temporal Knowledge Graph Completion. ArXiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Cheng, W.; Luo, D.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X. InfoGCL: Information-Aware Graph Contrastive Learning. ArXiv 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Tu, W.; Wen, Y.; Yang, X.; Dong, X.; Liu, X. Knowledge Graph Contrastive Learning Based on Relation-Symmetrical Structure. ArXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turki, T.; et al. Semantic-Based Image Retrieval: Enhancing Visual Search with Knowledge Graph Structures. Saudi Journal of Engineering and Technology 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, G.; Sansaro, G.; Vessio, G. Integrating Contextual Knowledge to Visual Features for Fine Art Classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.15028, arXiv:2105.15028 2021.

- Füßl, A.; Nissen, V. Design of Explanation User Interfaces for Interactive Machine Learning. Requirements Engineering 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzaghi, S.; Colitti, S.; Moretti, A.; Renda, G. From Metadata to Storytelling: A Framework For 3D Cultural Heritage Visualization on RDF Data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.14328, arXiv:2505.14328 2025.

- Romphf, J.; Neuman-Donihue, E.; Heyworth, G.; Zhu, Y. Resurrect3D: An Open and Customizable Platform for Visualizing and Analyzing Cultural Heritage Artifacts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.09509, arXiv:2106.09509 2021.

- ARTEMIS Applying Reactive Twins to Enhance Monument Information Systems. Available online: https://www.artemis-twin.eu. (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Castelli, L.; Felicetti, A.; Proietti, F. Heritage Science and Cultural Heritage: standards and tools for establishing cross-domain data interoperability. International Journal on Digital Libraries 2021, 22, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The AO-Cat Ontology. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/7818375. (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- ARIADNE Research Infrastructure. Available online: https://www.ariadne-research-infrastructure.eu. (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Mazzinghi, A.; Ruberto, C.; Giuntini, L.; Mandò, P.A.; Taccetti, F.; Castelli, L. Mapping with Macro X-ray Fluorescence Scanning of Raffaello’s Portrait of Leo X. Heritage 2022, 5, 3993–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishth, S.; Sanyal, S.; Nitin, V.; Talukdar, P. Composition-based Multi-Relational Graph Convolutional Networks. Proceedings of ICLR 2020, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Emonet, V.; Bolleman, J.; Duvaud, S.; de Farias, T.; Sima, A.C. LLM-based SPARQL Query Generation from Natural Language over Federated Knowledge Graphs. arXiv, 2025; arXiv:2410.06062. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, F.; Zhang, W. SparqLLM: Augmented Knowledge Graph Querying leveraging LLMs. arXiv, 2025; arXiv:2502.01298. [Google Scholar]

- Celino, I. Who is this Explanation for? Human Intelligence and Knowledge Graphs for eXplainable AI. arXiv, 2020; arXiv:2005.13275. [Google Scholar]

- Kamar, E. Directions in Hybrid Intelligence: Complementing AI Systems with Human Intelligence. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of AAAI Spring Symposium: Technical Report; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Te’eni, D.; Yahav, I.; Zagalsky, A.; Schwartz, D.G.; Silverman, G. Reciprocal Human–Machine Learning: A Theory and an Instantiation for the Case of Message Classification. Management Science 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foka, A.; Griffin, G.; Ortiz Pablo, D.; Rajkowska, P.; Badri, S. Tracing the bias loop: AI, cultural heritage and bias-mitigating in practice. AI & Society.

- Tóth, G.M.; Albrecht, R.; Pruski, C. Explainable AI, LLM, and digitized archival cultural heritage: a case study of the Grand Ducal Archive of the Medici. AI & Society, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, U.; Carman, M. Cultural Bias in Explainable AI Research: A Systematic Analysis. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M. AI Is Spreading Old Stereotypes to New Languages and Cultures. Wired 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Upmann, P. What Role Does Cultural Context Play in Defining Ethical Standards for AI? AI Global 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakaran, V.; Qadri, R.; Hutchinson, B. Cultural Incongruencies in Artificial Intelligence. ArXiv, 2022; arXiv:2211.13069. [Google Scholar]

- Inuwa-Dutse, I. FATE in AI: Towards Algorithmic Inclusivity and Accessibility. ArXiv, 2023; arXiv:2301.01590. [Google Scholar]

- Kukutai, T.; Taylor, J. Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Towards an Agenda; ANU Press, 2020.

- Tooth, J.M.; Tuptuk, N.; Watson, J.D.M. A Systematic Survey of the Gemini Principles for Digital Twin Ontologies, 2024. Version Number: 1. [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, R.D.; Sarkar, A.; Karray, M.H.; Addepalli, S.; Erkoyuncu, J.A. Knowledge transfer in Digital Twins: The methodology to develop Cognitive Digital Twins. CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology 2024, 52, 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Fragment B 40. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).