Submitted:

19 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Contextual Factors

3.2. Mental Health Outcomes

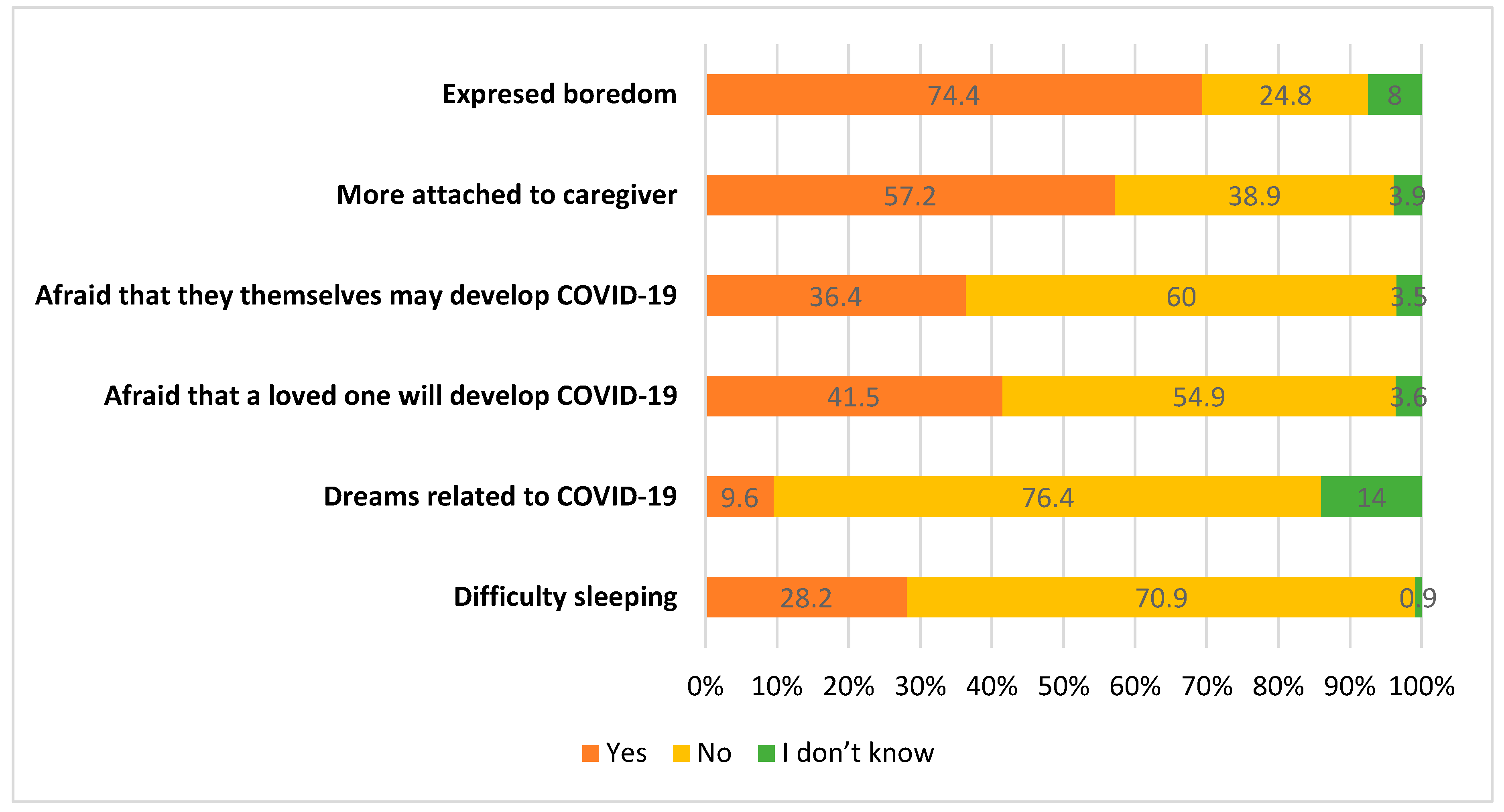

3.3. Behavioral Changes

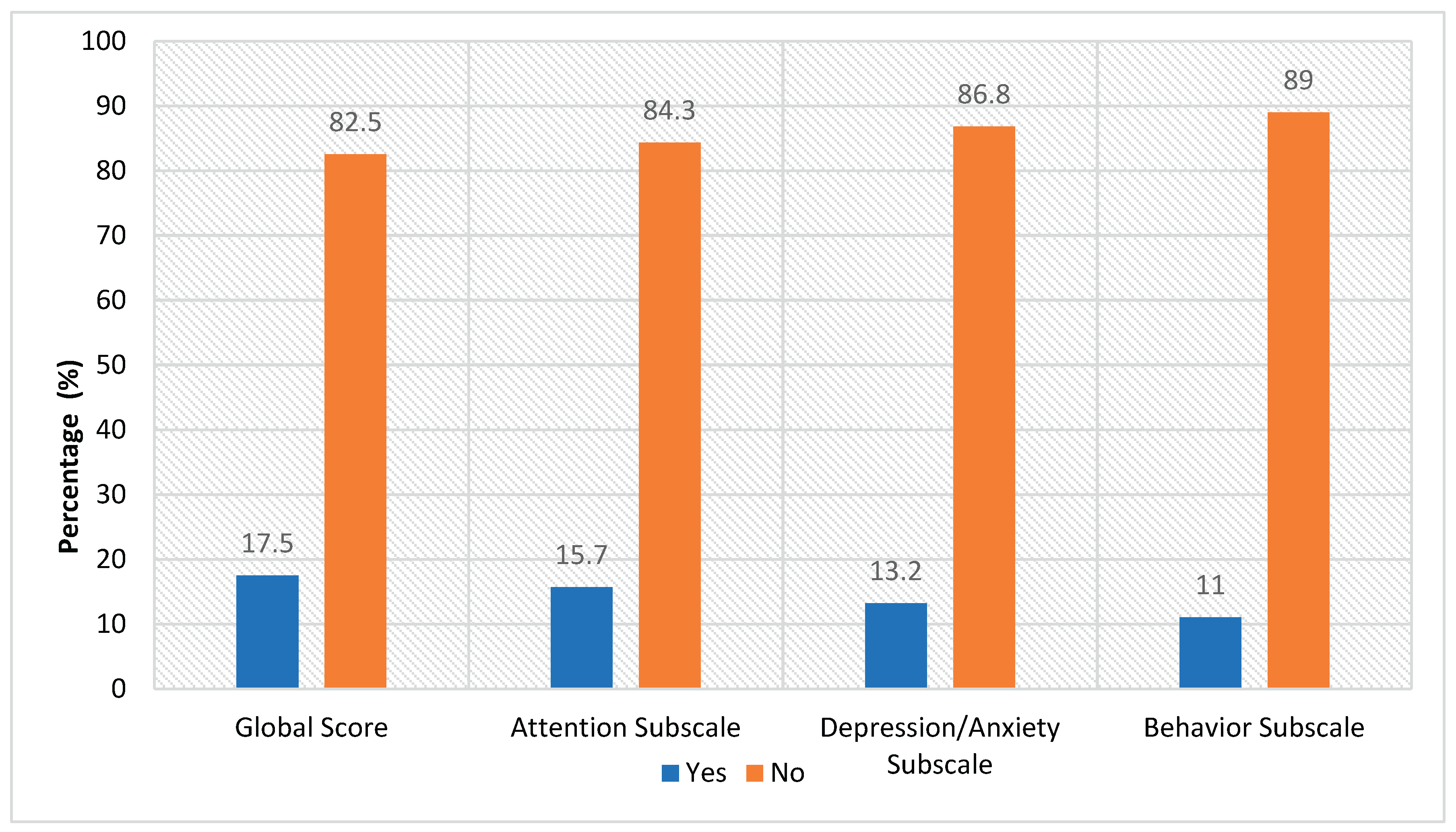

3.4. Pediatric Symptoms Checklist-35 Results

3.5. Associations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. (2020). Policy brief on COVID-19 impact on children https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/mca-documents/mca-covid/policy-brief-on-covid-impact-on- children-16-april-20.

- Wang, G. , Zhang, Y., Zhao, J., Zhang, J., & Jiang, F. (2020). Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet, 395(10228), 945-947. [CrossRef]

- Bai, R. , Wang, Z., Liang, J., Qi, J., & He, X. (2020). The effect of the COVID-19 outbreak on children’s behavior and parents’ mental health in China: A research study. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Orgilés, M. , Morales, A., Delvecchio, E., Mazzeschi, C., & Espada, J. P. (2020). Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. OSF Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S. K. , Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912-920. [CrossRef]

- Massachusetts General Hospital. (2020). Pediatric symptom checklist https://www.massgeneral.org/psychiatry/treatments-and-services/pediatric-symptom-checklist.

- TNAAP. (n.d.). Pediatric symptom checklist scoring. https://www.tnaap.org/documents/psc-35-scoring- instructions.pdf.

- Jellinek, M. S. , Murphy, J. M., Little, M., Pagano, M. E., Comer, D. M., & Kelleher, K. J. (1999). Use of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist to screen for psychosocial problems in pediatric primary care. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 153(3), 254-260. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. J. , Bao, Y., Huang, X., Shi, J., & Lu, L. (2020). Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(5), 347-349. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R. , Dubey, M. J., Chatterjee, S., & Dubey, S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on children: Special focus on the psychosocial aspect. Minerva Pediatrica, 72(3), 226-235. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X. , Xue, Q., Zhou, Y., et al. (2020). Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatrics 174(9), 898–900. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, W. Y. , Wang, L. N., Liu, J., et al. (2020). Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. The Journal of Pediatrics, 221, 264-266. [CrossRef]

- Meade, J. (2021). Mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents: A review of the current research. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 68(5), 2020341184016192020. [CrossRef]

- Pearcey, S. , Shum, A., Waite, P., Patalay, P., & Creswell, C. (2020). Changes in children and young people’s emotional and behavioral difficulties through lockdown 2020. Emerging Minds.

- Hooft, E. A. J. V. , & Hooff, M. L. M. V. (2018). The state of boredom: Frustrating or depressing? Motivation and Emotion, 42(6), 931-946. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, A. , & Eastwood, J. D. (2016). Does state boredom cause failures of attention? Examining the relations between trait boredom, state boredom, and sustained attention. Experimental Brain Research, 236(8), 2483-2492. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J. M. , Ruttle, P. L., Klein, M. H., Essex, M. J., & Benca, R. M. (2014). Associations of child insomnia, sleep movement, and their persistence with mental health symptoms in childhood and adolescence. Sleep 37(6), 901–909. [CrossRef]

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age range | 3-5 years old | 346 | 35 | |

| 6-9 years old | 278 | 28.1 | ||

| 10-13 years old | 222 | 22.5 | ||

| 14-17 years old | 142 | 14.4 | ||

| Sex | Female | 468 | 47.4 | |

| Male | 518 | 52.4 | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 2 | 0.2 | ||

| Labor status of the head of the household, prior to the state of emergency | Self Employed / Independent | 307 | 31.1 | |

| Unemployed | 35 | 3.5 | ||

| Formal employee | 614 | 62.1 | ||

| Informal employee | 32 | 3.2 | ||

| Current employment status of the head of the household | Unemployed | 95 | 9.6 | |

| Employee | 691 | 69.9 | ||

| Suspended | 202 | 20.4 | ||

| Presence of patio or terrace in the home | No | 444 | 44.9 | |

| I don’t know | 1 | 0.1 | ||

| Yes | 543 | 55 | ||

| Presence of siblings in the home | No | 340 | 34.4 | |

| Yes | 648 | 65.6 | ||

| Number of people living in the home | 5 or more people | 299 | 30.3 | |

| 4 people | 354 | 35.8 | ||

| 3 people | 265 | 26.8 | ||

| 2 people | 70 | 7.1 | ||

| Separation from mother, father, or legal guardian during the pandemic | No | 916 | 92.7 | |

| I don’t know | 1 | 0.1 | ||

| Yes | 71 | 7.2 | ||

| Close family member diagnosed with COVID-19 | No | 896 | 90.7 | |

| I don’t know | 9 | 0.9 | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 2 | 0.2 | ||

| Yes | 81 | 8.2 | ||

| Child or adolescent diagnosed with COVID-19 | No | 985 | 99.7 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 0.1 | ||

| Yes | 2 | 0.2 | ||

| Time without leaving home | Less than 1 week | 103 | 10.4 | |

| 1 week | 50 | 5.1 | ||

| 2 weeks | 33 | 3.3 | ||

| 3 weeks | 26 | 2.6 | ||

| 4 weeks | 32 | 3.2 | ||

| More than 1 month | 744 | 75.3 | ||

| Death of a close loved one | No | 969 | 98.1 | |

| I don’t know | 2 | 0.2 | ||

| Yes | 17 | 1.7 | ||

| Desire for information about COVID-19 | Talk or do enough investigation | 339 | 34.3 | |

| Talk or do a lot of investigation | 84 | 8.5 | ||

| Try not to talk or do a lot of investigation | 565 | 57.2 |

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Behavioral changes |

Excessive crying or constant irritation | 248 | 25.1 |

| Returning to behaviors that had been overcome (for example, bathroom accidents or bed-wetting) | 83 | 8.4 | |

| Excessive worry or sadness | 85 | 8.6 | |

| Unhealthy eating habits | 267 | 27.0 | |

| Unhealthy sleeping habits | 302 | 30.6 | |

| Tantrums and rebellious behavior | 436 | 44.1 | |

| Difficulty in attention and concentration | 319 | 32.3 | |

| Avoid activities you enjoyed in the past | 69 | 7.0 | |

| Unexplained headaches or body pain | 151 | 15.3 | |

| Use of drugs and / or alcohol | 1 | 0.1 | |

| None of the above | 224 | 22.7 | |

| Recreation activities | Read a book | 263 | 26.6 |

| Dance or sing | 535 | 54.1 | |

| Make crafts | 432 | 43.7 | |

| Watch TV | 765 | 77.4 | |

| Use social networks | 301 | 30.5 | |

| Listen to music | 492 | 49.8 | |

| Exercise or yoga | 261 | 26.4 | |

| Cook | 313 | 31.7 | |

| Play an instrument | 92 | 9.3 | |

| Playing video games | 413 | 41.8 | |

| Using the cell phone or tablet | 840 | 85.0 | |

| Play (alone or accompanied) | 90 | 9.1 | |

| Paint and / or draw | 20 | 2.0 | |

| Use the pool | 15 | 1.5 | |

| Others | 41 | 4.1 |

| Global score | Attention subscale | Depression/anxiety subscale | Behavior subscale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Risk (n)(%) | Risk (n)(%) | No Risk (n)(%) | Risk (n)(%) | No Risk (n)(%) | Risk (n)(%) | No Risk (n)(%) | Risk (n)(%) | ||

| Behavioral changes | Excessive crying or constant irritation | 153(61.7) | 95(38.3) | 172(69.4) | 76(30.6) | 192(77.4) | 56(22.6) | 188(75.8) | 60(24.2) |

| Returning to behaviors that had been overcome (for example, bathroom accidents or bed-wetting) |

53(63.9) |

30(36.1) |

55(66.3) |

28(33.7) |

73(88.0) |

10(12.0) |

67(80.7) |

16(19.3) |

|

| Excessive worry or sadness | 39(45.9) | 46(54.1) | 61(71.8) | 24 (28.2) | 34(40.0) | 51(60.0) | 70(82.4) | 15(17.6) | |

| Unhealthy eating habits | 194(72.7) | 73(27.3) | 210(78.7) | 57 (21.3) | 210(78.7) | 57(21.3) | 229(26.1) | 38(34.9) | |

| Unhealthy sleeping habits | 222(73.5) | 80(26.5) | 244(80.8) | 58(19.2) | 233(77.2) | 69(22.8) | 264(85.8) | 38(14.2) | |

| Tantrums and rebellious behavior | 305(70.0) | 131(30.0) | 319(73.2) | 117(26.8) | 371(85.1) | 65(14.9) | 352(80.7) | 84(19.3) | |

| Difficulty in attention and concentration | 220(69.0) | 99(31.0) | 217(68.0) | 102(32.0) | 256(80.3) | 63(19.7) | 261(81.8) | 58(18.2) | |

| Avoid activities that you enjoyed in the past | 47(68.1) | 22(31.9) | 55(79.7) | 14(20.3) | 47(68.1) | 22(31.9) | 59(85.5) | 10(14.5) | |

| Unexplained headaches or body pain | 91(60.3) | 60(39.7) | 114(75.5) | 37(24.5) | 102(67.5) | 49(32.5) | 126(83.4) | 23(16.6) | |

| Use of drugs and/or alcohol | 0(0.0) | 1(100.0) | 1(100.0) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 1(100) | 1(100.0) | 0(0.0) | |

| None of the above | 224(100) | 0(0.0) | 217(96.9) | 7(3.1) | 219(97.8) | 5(2.2) | 216(96.4) | 8(3.6) | |

| Recreational activities | Read a book | 228(86.7) | 35(13.3) | 229(87.1) | 34(12.9) | 231(87.8) | 32(12.2) | 239(90.9) | 24(9.1) |

| Dance or sing | 445(83.2) | 90(16.8) | 442(82.6) | 93(17.4) | 475(88.8) | 60(11.2) | 477(89.2) | 58(10.8) | |

| Make crafts | 370(85.6) | 62(35.8) | 340(78.7) | 92(21.3) | 390(90.3) | 42(9.7) | 391(90.5) | 41(9.5) | |

| Watch TV | 627(76.9) | 138(14.4) | 639(83.5) | 126(16.5) | 671(87.7) | 94(12.3) | 681(89.0) | 84(11.0) | |

| Use social networks | 252(83.7) | 49(16.3) | 266(88.4) | 35(11.6) | 245(81.4) | 56(18.6) | 270(89.7) | 31(10.3) | |

| Listen to music | 413(83.9) | 79(16.1) | 426(86.6) | 66(13.4) | 421(85.6) | 71(14.4) | 444(90.2) | 48(9.8) | |

| Exercise or yoga | 227(87.0) | 34(13.0) | 225(86.2) | 36(13.8) | 238(91.2) | 23(8.8) | 238(91.2) | 23(8.8) | |

| Cook | 262(83.7) | 51(16.3) | 267(85.3) | 46(14.7) | 265(84.7) | 48(15.3) | 281(89.8) | 32(10.2) | |

| Play an instrument | 73(79.3) | 19(20.7) | 71(77.2) | 21(22.8) | 79(85.9) | 13(14.1) | 78(84.8) | 14(15.2) | |

| Playing video games | 333(80.6) | 80(19.4) | 344(83.3) | 69(16.7) | 348(84.3) | 65(15.7) | 364(88.1) | 49(11.9) | |

| Using the cell phone or tablet | 691(82.3) | 149(17.7) | 710(84.5) | 130(15.5) | 731(87.0) | 109(13.0) | 744(86.6) | 96(11.4) | |

| Play (alone or accompanied) | 82(91.1) | 8(8.9) | 76(84.4) | 14(16.6) | 88(97.8) | 2(2.2) | 82(91.1) | 8(8.9) | |

| Paint and/or draw | 15(75.0) | 5(25.0) | 17(85.0) | 3(15.0) | 19(95.0) | 1(5.0) | 17(85.5) | 3(15.0) | |

| Use the pool | 11(73.3) | 4(26.7) | 10(66.7) | 5(33.3) | 13(86.7) | 2(13.3) | 12(80.0) | 3(20.0) | |

| Global score | Attention subscale | Depression/anxiety subscale | Behavior subscale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Risk (n)(%) | Risk (n)(%) | No Risk (n)(%) | Risk (n)(%) | No Risk (n)(%) | Risk (n)(%) | No Risk (n)(%) | Risk (n)(%) | ||

|

Relationship with the child or adolescent |

Legal guardian | 32(76.2) | 10(23.8) | 31(73.8) | 11(26.2) | 36(85.7) | 6(14.3) | 37(88.1) | 5(11.9) |

| Father | 41(91.1) | 4(8.9) | 42(93.3) | 3(6.7) | 43(95.6) | 2(4.4) | 42(93.3) | 3(6.7) | |

| Mother | 742(82.4) | 159(17.6) | 760(84.4) | 141(15.6) | 779(86.5) | 122(13.5) | 800(88.8) | 101(11.2) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.175 | 0.043* | 0.207 | 0.626 | |||||

| Cramer’s V | - | 0.080 | - | - | |||||

|

Age range |

3-5 years old | 282(81.5) | 64(18.5) | 278(80.3) | 68(19.7) | 333(96.2) | 13(3.8) | 302(87.3) | 44(12.7) |

| 6-9 years old | 229(82.4) | 49(17.6) | 220(79.1) | 58(20.9) | 235(84.5) | 43(15.5) | 248(89.2) | 30(10.8) | |

| 10-13 years old | 183(82.4) | 39(17.6) | 198(89.2) | 24(10.8) | 184(82.9) | 38(17.1) | 200(90.1) | 22(9.9) | |

| 14-17 years old | 121(85.2) | 21(14.8) | 137(96.5) | 5(3.5) | 106(74.6) | 36(25.4) | 129(90.8) | 13(9.2) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.810 | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.612 | |||||

| Cramer’s V | - | 0.173 | 0.224 | - | |||||

|

Labor status of the head of the household, prior to the state of emergency |

Informal employee | 25(78.1) | 7(21.9) | 30(93.8) | 2(6.3) | 26(81.3) | 6(18.8) | 27(84.4) | 5(15.6) |

| Formal employee | 514(83.7) | 100(16.3) | 517(84.2) | 97(15.8) | 539(87.8) | 75(12.2) | 560(91.2) | 54(8.8) | |

| Unemployed | 23(65.7) | 12(34.3) | 25(71.4) | 10(28.6) | 27(77.1) | 8(22.9) | 28(80.0) | 7(20.0) | |

| Self Employed / Independent | 253(82.4) | 54(17.6) | 261(85.0) | 46(15.0) | 266(86.6) | 41(13.4) | 264(86.0) | 43(14.0) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.049* | 0.083* | 0.236 | 0.024* | |||||

| Cramer’s V | 0.089 | 0.082 | - | 0.098 | |||||

|

Current employment status of the head of the household |

Suspended | 164(81.2) | 38(18.8) | 167(82.7) | 35(17.3) | 176(87.1) | 26(12.9) | 174(86.1) | 28(13.9) |

| Employee | 581(84.1) | 110(15.9) | 593(85.8) | 98(14.2) | 606(87.7) | 85(12.3) | 626(90.6) | 65(9.4) | |

| Unemployed | 70(73.7) | 25(26.3) | 73(76.8) | 22(23.2) | 76(80.0) | 19(20.0) | 79(83.2) | 16(16.8) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.038* | 0.061 | 0.114 | 0.034* | |||||

| Cramer’s V | 0.081 | - | - | 0.083 | |||||

|

Presence of patio or terrace in the home |

Yes | 467(86.0) | 76(14.0) | 474(87.3) | 69(12.7) | 474(87.3) | 68(12.7) | 490(90.2) | 53(9.8) |

| I don’t know | 1(100.0) | 0(0) | 1(100.0) | 0(0) | 1(100.0) | 0(0) | 1(100.0) | 0(0) | |

| No | 347(78.2) | 97(21.8) | 358(80.6) | 86(19.4) | 383(86.3) | 61(13.7) | 388(89.0) | 56(11.0) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.005* | 0.015* | 0.827 | 0.342 | |||||

| Cramer’s V | 0.104 | 0.092 | - | - | |||||

|

Presence of siblings in the home |

Yes | 520(80.2) | 128(19.8) | 548(84.6) | 100(15.4) | 546(84.3) | 102(15.7) | 563(86.9) | 85(13.1) |

| No | 295(86.8) | 45(13.2) | 285(83.8) | 55(16.2) | 312(91.8) | 28(8.2) | 316(92.9) | 24(7.1) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.010* | 0.760 | 0.001* | 0.004* | |||||

| Cramer’s V | 0.081 | - | 0.105 | 0.092 | |||||

|

Number of people living in the home |

5 or more people | 236(78.9) | 63(21.1) | 253(84.6) | 46(15.4) | 253(84.6) | 46(15.4) | 252(84.3) | 47(15.7) |

| 4 people | 299(84.5) | 55(15.5) | 296(83.6) | 58(16.4) | 308(87.0) | 46(13.0) | 321(90.7) | 33(9.3) | |

| 3 people | 219(82.6) | 46(17.4) | 225(84.9) | 40(15.1) | 233(87.9) | 32(12.1) | 241(90.9) | 24(9.1) | |

| 2 people | 61(87.1) | 9(12.9) | 59(84.3) | 11(15.7) | 64(91.4) | 6(8.6) | 65(92.9) | 5(7.1) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.201 | 0.974 | 0.413 | 0.020* | |||||

| Cramer’s V | - | - | - | 0.100 | |||||

|

Difficulty sleeping |

Yes | 194(69.5) | 85(30.5) | 209(74.9) | 70(25.1) | 213(76.3) | 66(23.7) | 235(84.2) | 44(15.8) |

| I don’t know | 8(88.9) | 1(11.1) | 9(100.0) | 0(0) | 7(77.8) | 2(22.2) | 8(88.9) | 1(11.1) | |

| No | 613(87.6) | 87(12.4) | 615(87.9) | 85(12.1) | 638(91.1) | 62(8.9) | 636(90.9) | 64(9.1) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.012* | |||||

| Cramer’s V | 0.214 | 0.165 | 0.198 | 0.950 | |||||

|

Dreams related to COVID-19 |

Yes | 61(64.2) | 34(35.8) | 73(76.8) | 22(23.2) | 64(67.4) | 31(32.6) | 84(88.4) | 11(11.6) |

| I don’t know | 98(71.0) | 40(29.0) | 108(78.3) | 30(21.7) | 111(80.4) | 27(19.6) | 109(79.0) | 29(21.0) | |

| No | 656(86.9) | 99(13.1) | 652(86.4) | 103(13.6) | 683(90.5) | 72(9.5) | 686(90.9) | 69(9.1) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.000* | 0.006* | 0.000* | 0.000* | |||||

| Cramer’s V | 0.213 | 0.102 | 0.214 | 0.130 | |||||

|

Afraid that a loved one will develop COVID-19 |

Yes | 319(77.8) | 91(22.2) | 337(82.2) | 73(17.8) | 326(79.5) | 84(20.5) | 366(89.3) | 44(10.7) |

| I don’t know | 28(77.8) | 8(22.2) | 30(83.3) | 6(16.7) | 29(80.6) | 7(19.4) | 30(83.3) | 6(16.7) | |

| No | 468(86.3) | 74(13.7) | 466(86.6) | 76(14.0) | 503(92.8) | 39(7.2) | 483(89.1) | 59(10.9) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.002* | 0.279 | 0.000* | 0.545 | |||||

| Cramer’s V | 0.112 | - | 0.195 | - | |||||

|

Afraid that they themselves will develop COVID-19 |

Yes | 282(78.3) | 78(21.7) | 298(82.8) | 62(17.2) | 289(80.3) | 71(19.7) | 326(90.6) | 34(9.4) |

| I don’t know | 24(68.6) | 11(31.4) | 30(85.7) | 5(14.3) | 25(71.4) | 10(28.6) | 26(74.3) | 9(25.7) | |

| No | 509(85.8) | 84(14.2) | 505(85.2) | 88(14.8) | 544(91.7) | 49(8.3) | 527(88.9) | 66(11.1) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.001* | 0.602 | 0.000* | 0.013* | |||||

| Cramer’s V | 0.117 | - | 0.184 | 0.093 | |||||

| More attached to caregiver | Yes | 437(77.3) | 128(22.7) | 450(79.6) | 115(20.4) | 483(85.5) | 82(14.5) | 493(87.3) | 72(12.7) |

| I don’t know | 32(82.1) | 7(17.9) | 31(79.5) | 8(20.5) | 34(87.2) | 5(12.8) | 33(84.6) | 6(15.4) | |

| No | 346(90.1) | 38(9.9) | 352(91.7) | 32(8.3) | 341(88.8) | 43(11.2) | 353(91.9) | 31(8.1) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.332 | 0.053 | |||||

| Cramer’s V | 0.162 | 0.161 | - | - | |||||

|

Expressed boredom |

Yes | 578(78.6) | 157(21.4) | 601(81.8) | 134(18.2) | 612(83.3) | 123(16.7) | 638(86.8) | 97(13.2) |

| I don’t know | 8(100.0) | 0(0) | 7(87.5) | 1(12.5) | 7(87.5) | 1(12.5) | 7(87.5) | 1(12.5) | |

| No | 229(93.5) | 16(6.5) | 225(91.8) | 20(8.2) | 239(97.6) | 6(2.4) | 234(95.5) | 11(4.5) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.000* | 0.001* | 0.000* | 0.001* | |||||

| Cramer’s V | 0.173 | 0.120 | 0.182 | 0.120 | |||||

| Desire for information about COVID-19 | Try not to talk or do a lot of investigation | 475(84.1) | 90(15.9) | 477(84.4) | 88(15.6) | 502(88.8) | 63(11.2) | 501(88.7) | 64(11.3) |

| Talk or do a lot of investigation | 57(67.9) | 27(32.1) | 69(82.1) | 15(17.9) | 65(77.4) | 19(22.6) | 70(83.3) | 14(16.7) | |

| Talk or do enough investigation | 283(83.5) | 56(16.5) | 287(84.7) | 52(15.3) | 291(85.8) | 48(14.2) | 308(90.9) | 31(9.1) | |

| Chi-Squared | 0.001* | 0.846 | 0.012* | 0.135 | |||||

| Cramer’s V | 0.118 | - | 0.095 | - | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).