1. Introduction

With the increasing stringency of global emission regulations and fuel economy requirements, automotive companies are accelerating their research, development, and introduction of new technologies to provide compliant solutions [

1,

2,

3]. Electrically assisted turbocharging (EAT) is one of them and an innovative technology developed to enhance the efficiency and performance of internal combustion engines (ICEs) and to reduce harmful emissions [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Traditional turbocharging systems rely on the kinetic energy of exhaust gases to compress the intake air, thereby allowing a higher amount of air-fuel mixture to enter the combustion chamber, increasing engine power [

8,

9]. However, at low engine speeds, the turbo may not generate sufficient pressure, leading to a performance issue known as turbo lag [

10]. EAT addresses this challenge by employing electric motors to support the turbo independently of exhaust gases, enabling immediate response and allowing the engine to operate efficiently across a wider range of speeds [

11,

12].

One of the key advantages of this technology is its ability to maintain high efficiency at all engine speeds. EAT improves low-end performance while also optimizing fuel economy and reducing emissions [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. As a result, they offer superior performance and promote lower fuel consumption and environmentally friendly driving in vehicles [

18,

19,

20]. This technology plays a pivotal role in helping the automotive industry meet its efficiency and sustainability goals through electric and hybrid solutions [

21,

22,

23]. EAT systems present an innovative alternative to traditional boosting methods for enhancing the efficiency of internal combustion engines and the boosting of ICEs has long been a compelling area of research and remains relevant today [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. This interest is likely to persist in the coming years due to ongoing emission regulations, trends toward engine downsizing, and the need for improved fuel efficiency [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

Katrašnik et al. [

34] indicated that the dynamic response of turbocharged diesel engines can be enhanced through electric assisting systems, which can either provide direct energy via an integrated starter–generator–booster (ISG) mounted on the engine flywheel or supply energy indirectly through an electrically assisted turbocharger. The results demonstrate that electrically assisted systems significantly improve load acceptance in turbocharged engines. Furthermore, these systems allow for reductions in production and operating costs by enabling the downsizing of electrically assisted engines while maintaining performance. An electrically assisted turbocharger facilitates a rapid increase in engine power due to its substantial boost pressure increase. To efficiently enhance the dynamics of turbocharged engines, an electric motor (EM) with a much higher angular acceleration than that of the conventional turbocharger is necessary, a requirement applicable to all types of turbochargers, including free-floating, waste-gated, and variable nozzle turbine (VNT) configurations. Panting et al. [

35] highlighted that using a direct drive motor generator to add or subtract power from the turbocharger shaft provides an additional degree of freedom for better engine-turbocharger matching. This method, known as hybrid turbocharging, can significantly enhance both engine efficiency and transient response. The study presents theoretical findings on the advantages of hybrid turbocharging over conventional systems in both steady-state and transient operations. Four different turbocharger configurations were analyzed alongside the baseline engine, demonstrating that re-matching turbocharger components improves design point cycle efficiency and enhances full throttle transient performance, while also reducing fuel consumption during steady-state operation. Tavčar et al. [

36] conducted a comprehensive analysis comparing various electrically assisted turbocharger configurations with a baseline turbocharged high-speed direct-injection (HSDI) diesel engine. The study evaluated systems including an electrically assisted turbocharger, a turbocharger with an additional electric compressor, and an electrically split turbocharger using a validated engine and vehicle model. Results across various driving conditions, such as tip-in scenarios and the New European Driving Cycle (NEDC), demonstrated that electrically assisted turbocharging improves transient engine response and drive ability. Additionally, these systems enhance steady-state torque output through energy stored in electric devices. Notably, the electrically split turbocharger significantly reduces fuel consumption in urban driving, while the turbocharger with an additional electric compressor delivers the highest low-speed torque and fastest transient response. Terdich et al. [

37] assessed the improvements in engine energy efficiency and transient response correlated to the hybridization of the air system. To achieve this, an electrically assisted turbocharger with a variable geometry turbine has been compared to a similar, not hybridized system over step changes of engine load. The variable geometry turbine has been controlled to provide different levels of initial boost, including one optimized for efficiency, and to change its flow capacity during the transient. The engine modeled is a 7-liter, 6-cylinder diesel engine with a power output of over 200 kW and a sub-10-kW turbocharger electric assistance power. To improve the accuracy of the model, the turbocharger turbine has been experimentally characterized by means of a unique testing facility available at Imperial College and the data has been extrapolated by means of a turbine meanline model. Optimization of the engine boost to minimize pumping losses has shown a reduction in brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC) by up to 4.2%. Kolmanovsky and Stefanopoulou [

38] simulated a bi-directional energy transfer system between the turbocharger shaft and energy storage on a medium-sized passenger car. The primary goal was not to maximize electric energy recovery for fuel consumption improvement; instead, the EAT system aimed to regenerate its own power during full-load accelerations to optimize transient response. Maximum power output in both motoring and generating modes was limited to 1.5 kW, with assumed efficiencies of 90% for the motor and 70% for the generator. Using optimal control techniques, they defined the best transient operating strategy, reporting a 10% improvement in takeoff performance during 0-40 km/h acceleration in first gear, without compromising smoke emissions and maintaining comparable fuel consumption to conventional turbocharged engines. Additionally, they concluded that to offset the acceleration improvement achieved, the rotor's moment of inertia would need to increase by 250%. In extending their research to parallel hybrid configurations with an electric motor on the drive shaft, Kolmanovsky and Stefanopoulou [

39] found that the hybrid vehicle required 10.3 kW to achieve the same acceleration time as the 1.5 kW EAT system, while Shahed [

40] indicated that his drive-line motor assist system needed 10 kW to match the performance of a 2 kW EAT system. Both studies noted similar fuel consumption across both system types when accounting for electric production. This power difference is attributed to the hybrid vehicle directly delivering electric torque to the crankshaft, whereas the EAT system increases air supply, enabling more fuel combustion to generate additional torque. Consequently, assisted turbocharging technology presents significant potential to deliver similar benefits—fuel efficiency and transient response—compared to hybrid systems, without the added weight and cost [

41].

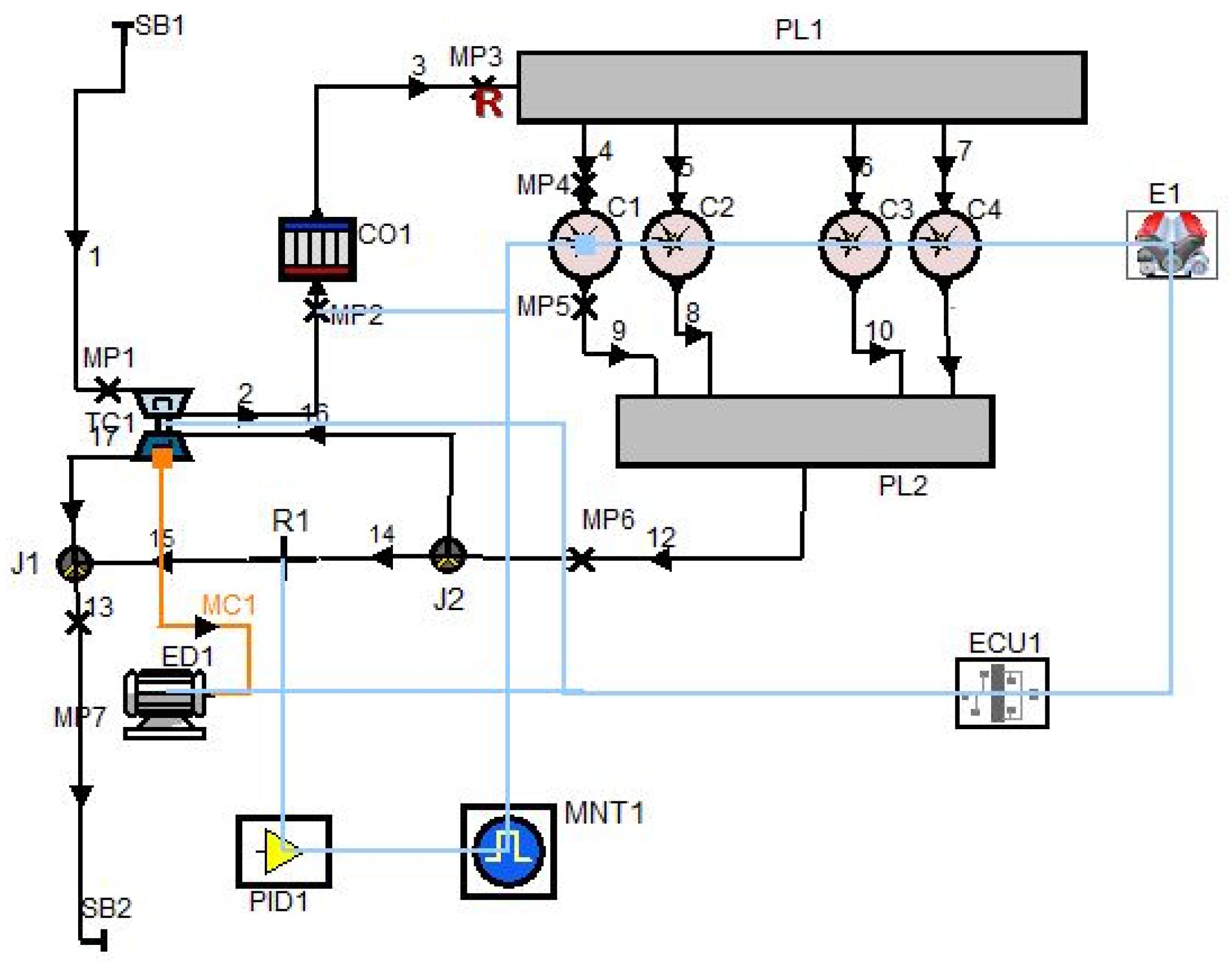

The objective of this study is to investigate the effects of electrically assisted turbocharger on diesel engine performance parameters. The experimental work of matching an electrically assisted turbocharger to an engine is rather expensive, therefore conventional turbocharged automotive diesel engine was simulated using AVL Boost and simulation results were compared with experimental results. Engine model simulation was run at three different electrical powers of 2, 2.5, and 3 kW, respectively the cause of investigate the effect of electrical power assistance on turbocharger. Boost pressure, turbocharger speed, turbine inlet temperature, turbine outlet temperature, turbine inlet pressure, electric power, electric motor mechanical work, engine torque, engine power, and BSFC values were simulated for three electric power values and interpreted. Also, the transient behavior of the electrically assisted turbocharger was simulated and commented on.

Although several studies have investigated electrically assisted turbocharging (EAT) technologies, most have focused on either theoretical aspects or limited performance cases. Few works have provided a systematic, comparative assessment of different electrical assistance levels on diesel engine performance across both steady-state and transient operating conditions. This study contributes a novel simulation-based evaluation of EAT’s impacts on engine response, particularly in mitigating turbo lag and improving low-speed torque. The research is distinguished by its inclusion of three discrete electric assist power levels (2, 2.5, and 3 kW) and evaluation under full-load transient events. Furthermore, the study leverages AVL Boost simulation with experimentally validated models, enhancing the reliability and reproducibility of findings. This work extends prior efforts by providing detailed performance metrics under dynamic conditions and establishing scalable design implications for modern diesel engines.

3. Results and Discussion

In this study an electrical device acting as a motor/generator was integrated into the AVL Boost model in order to investigate the effects of electrically assisted turbocharger on diesel engine performance parameters. The model simulation was run at three different electrical power of 2, 2.5, and 3 kW at full load conditions in order to investigate the effect of electrical power assistance on turbocharger. Boost pressure, turbocharger speed, turbine inlet temperature, turbine outlet temperature, turbine inlet pressure, electric power, electric motor mechanical work, engine torque, engine power, and BSFC values were simulated for three electric power values and compared with results of conventional turbocharged automotive diesel engine.

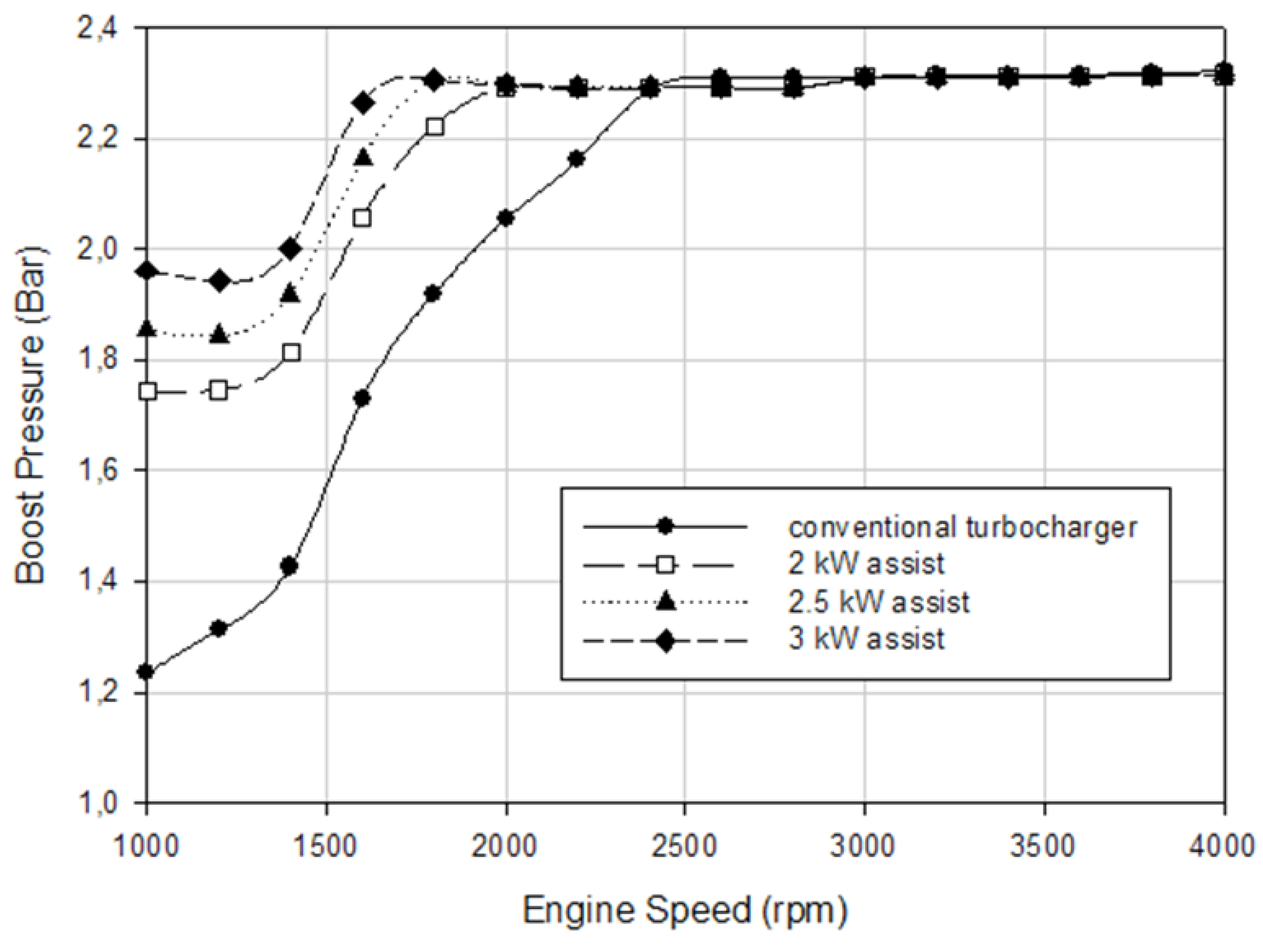

The effects of different electrical power assist on boost pressure values according to varying engine speeds at full load conditions are presented in

Figure 2. Boost pressure is limited to 2.3 bar with waste gate application. The maximum boost pressure which is 2.3 bar was obtained at 2400 rpm for the conventional turbocharged engine. When the turbocharger was assisted with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power, maximum boost pressure was achieved at 2000, 1800, and 1600 rpm, respectively. The boost pressure of a conventional turbocharged diesel engine was increased with electrical power assistance. The boost pressure was increased by 41.2%, 50.2%, and 58.9% at 1000 rpm engine speed with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively. The average increment is 22%, 27%, and 30.9% with electrical power assistance as 2, 2.5, and 3 kW, respectively for the low engine speed zone, which is between 1000-2200 rpm. Therefore, it can be concluded that electrical power assist to the turbocharger enhances boost pressure in the turbo lag region where the exhaust gases are insufficient to provide proper boost pressure.

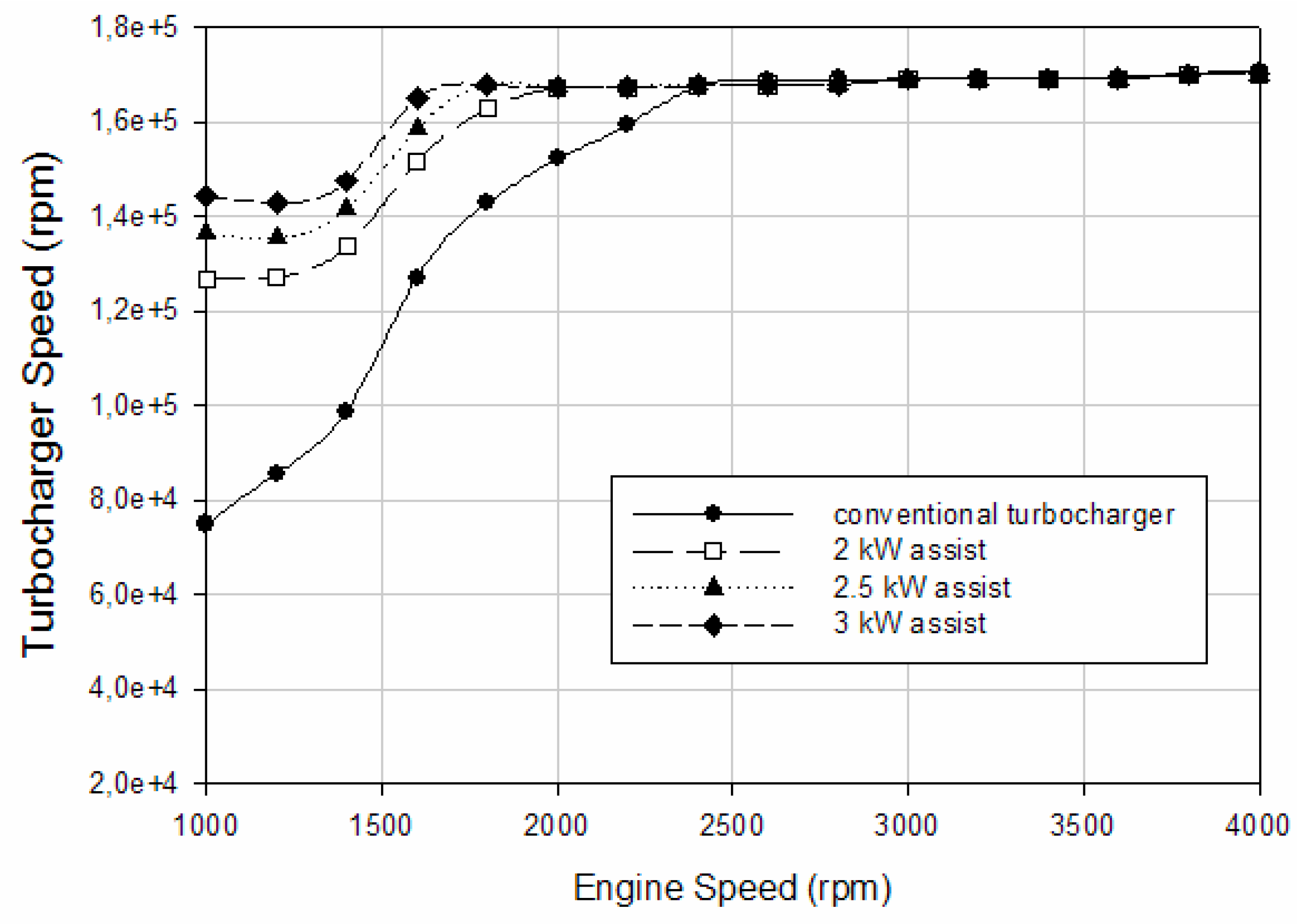

The variation of turbocharger speed according to varying engine speed values for different electrical power assistance at full load conditions is illustrated in

Figure 3. It shows a similar trend with boost pressure versus engine speed graph because boost pressure is directly proportional to the turbocharger speed. The engine speed where the maximum turbocharger speed obtained was reduced from 2400 rpm to 2000, 1800, and 1600 rpm with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively. Turbocharger speed of conventional turbocharged diesel engines was increased by 69.3%, 82%, and 92.6% at 1000 rpm, 48.6%, 58.2% and 67% at 1200 rpm, and 35%, 43.1% and 49.1% at 1400 rpm engine speed with 2-, 2.5- and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively. The average increment is 28.7%, 34.4%, and 38.7% with electrical power assistance as 2, 2.5, and 3 kW, respectively for the low engine speed zone, which is between 1000-2200 rpm.

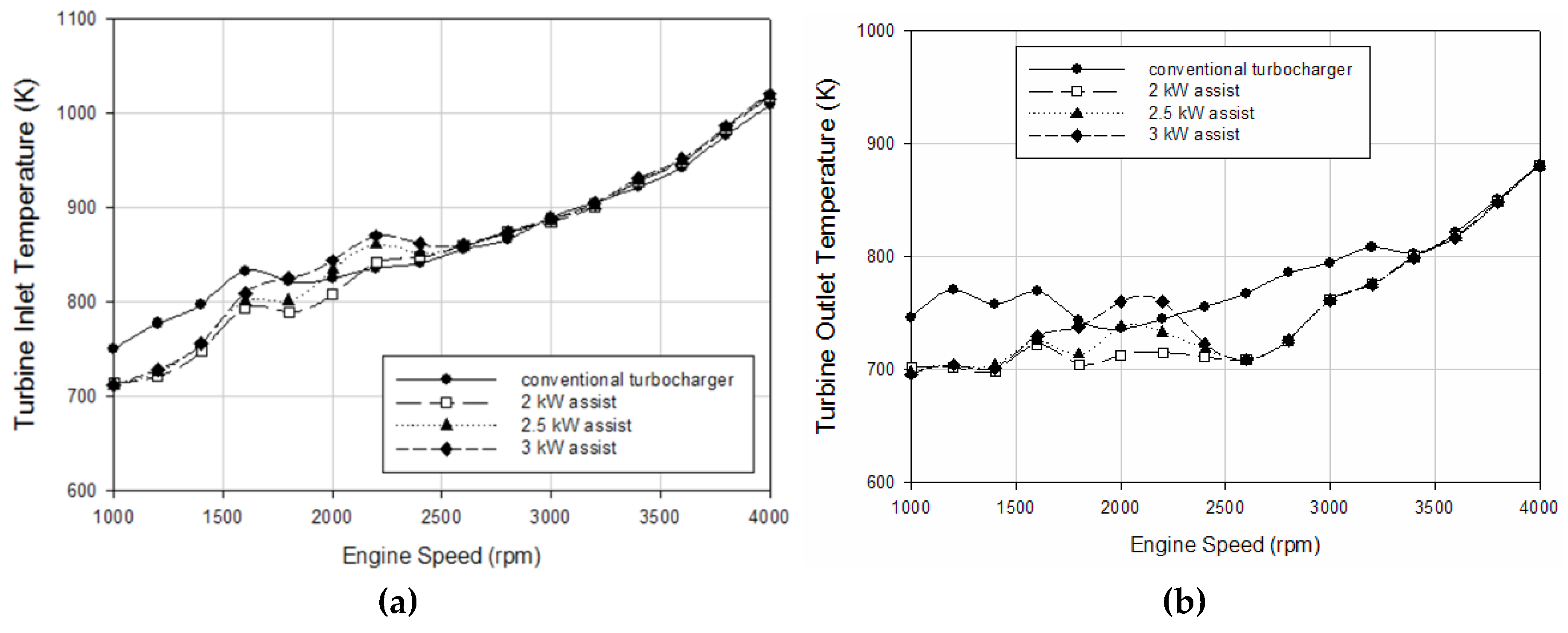

Figure 4 demonstrates the variation of turbine inlet and outlet temperature values according to varying engine speeds for different electrical power assistance at full load conditions. The turbine inlet and outlet temperature were decreased with electrical power assistance.

The average reduction for turbine inlet temperature was 4%, 2.5%, and 0.5% with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively for the low engine speed range (1000-2200 rpm). Furthermore, the average reduction for turbine outlet temperature was 6.1%, 5%, and 3.6% with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively for the low engine speed range.

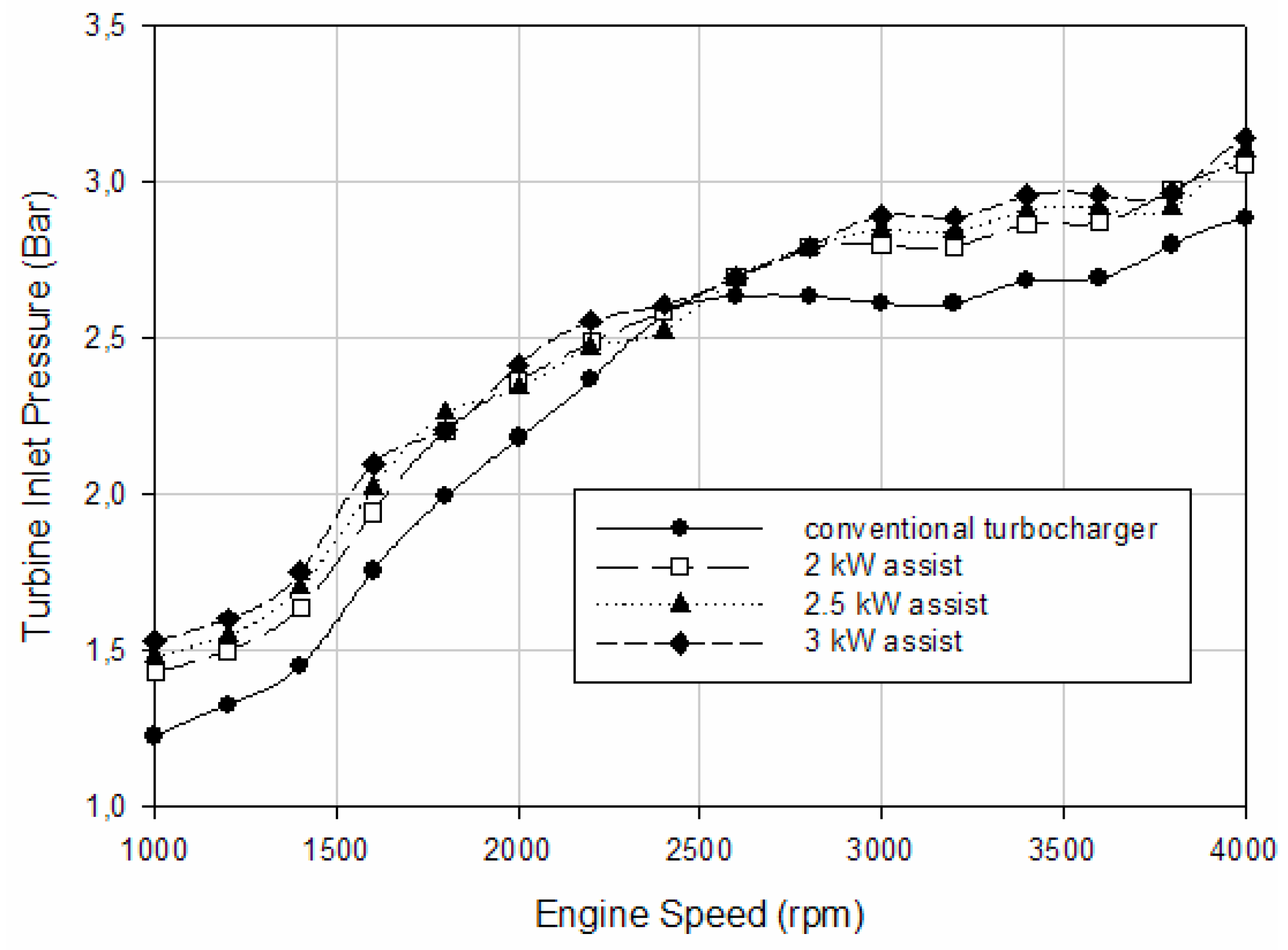

The variation of turbine inlet pressure according to varying engine speed values for different electrical power assistance at full load conditions is shown in

Figure 5. The turbine inlet pressure of a conventional turbocharged diesel engine was increased with electrical power assistance. The turbine inlet pressure was increased by 16.6%, 20.8%, and 24.8% at 1000 rpm and 13%, 16.9%, and 20.7% at 1200 rpm engine speed with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively. The average increment is 7.8%, 9.2%, and 11.3% with electrical power assistance as 2, 2.5, and 3 kW, respectively.

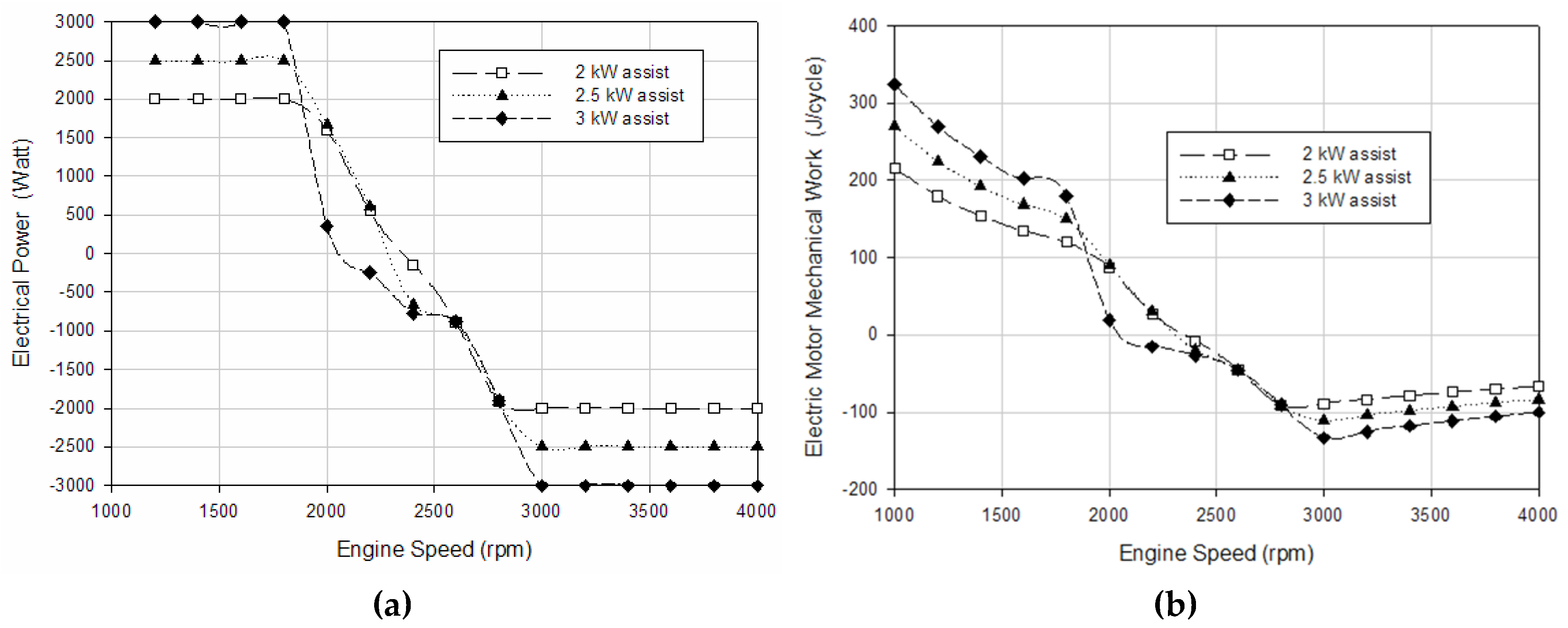

Figure 6 illustrates the variation of electrical power and electric motor mechanical work values with respect to varying engine speeds for different electrical power assistance at full load conditions. The electrical device acts as a motor and supplies electrical power until the target boost pressure is achieved and when the target boost pressure is obtained acts as a generator and produces electrical power as shown in the following figures. At low engine speeds where exhaust gas energy is insufficient to produce proper boost pressure turbocharger is electrically assisted and boost pressure is increased which improves the transient response of the turbocharge

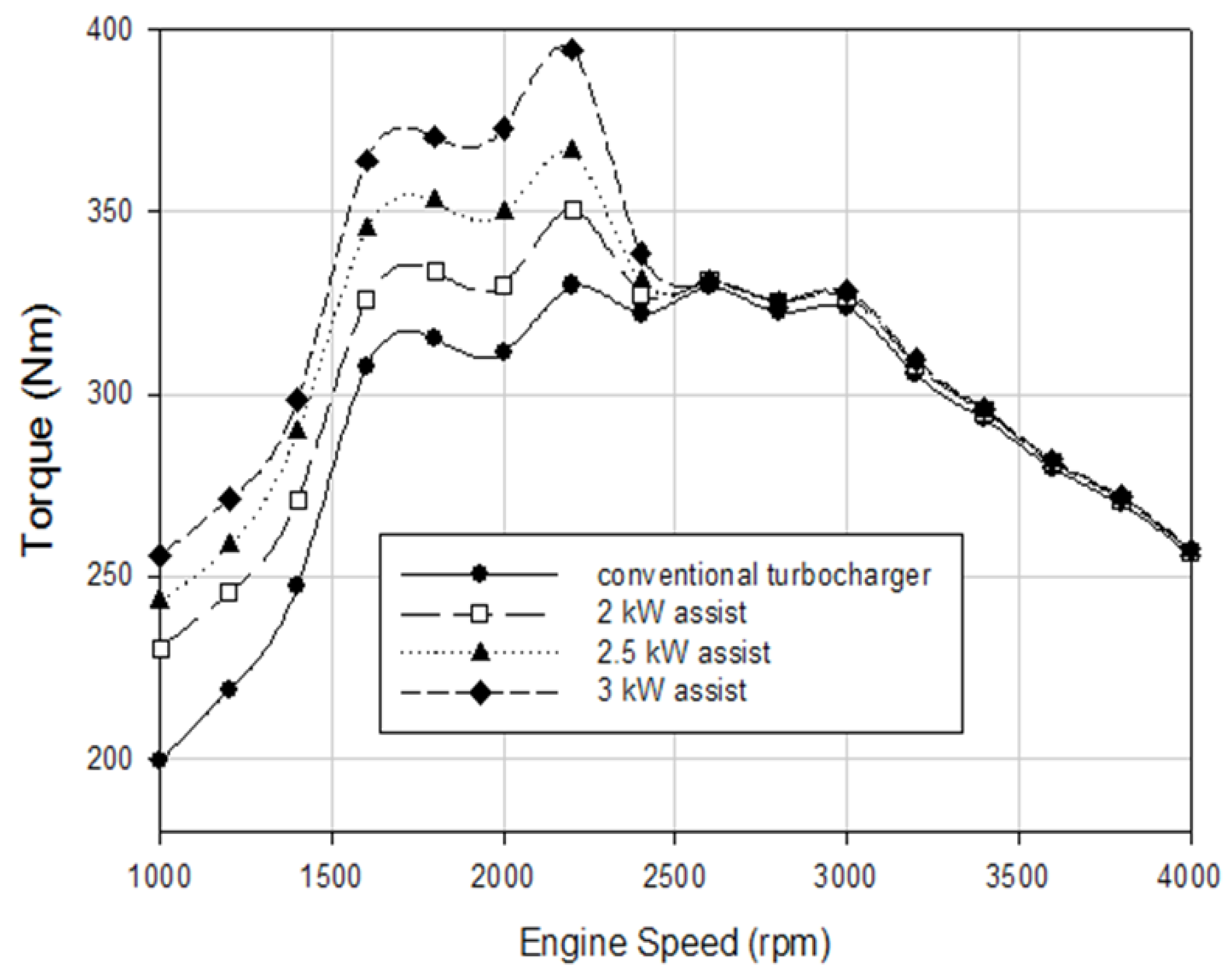

The variation of engine torque according to varying engine speed values for different electrical power assistance at full load conditions is presented in

Figure 7. Engine torque was increased with electrical power assistance where the electric device acts as a motor at a low engine speed zone. Engine torque of conventional turbocharged diesel engines was increased by 15.6%, 22%, and 28.2% at 1000 rpm, 12.1%, 18.1%, and 23.9% at 1200 rpm and 9.4%, 17% and 20.6% at 1400 rpm engine speed with 2-, 2.5- and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively. The average improvement is 8.8%, 15%, and 21.1% with electrical power assistance as 2, 2.5, and 3 kW, respectively for the low engine speed zone, which is between 1000-2200. This effect was thought to be due mainly to the higher air-fuel ratio. It can be concluded that electrical power assist to the conventional turbocharger improves low-end torque and reduces turbo lag during acceleration.

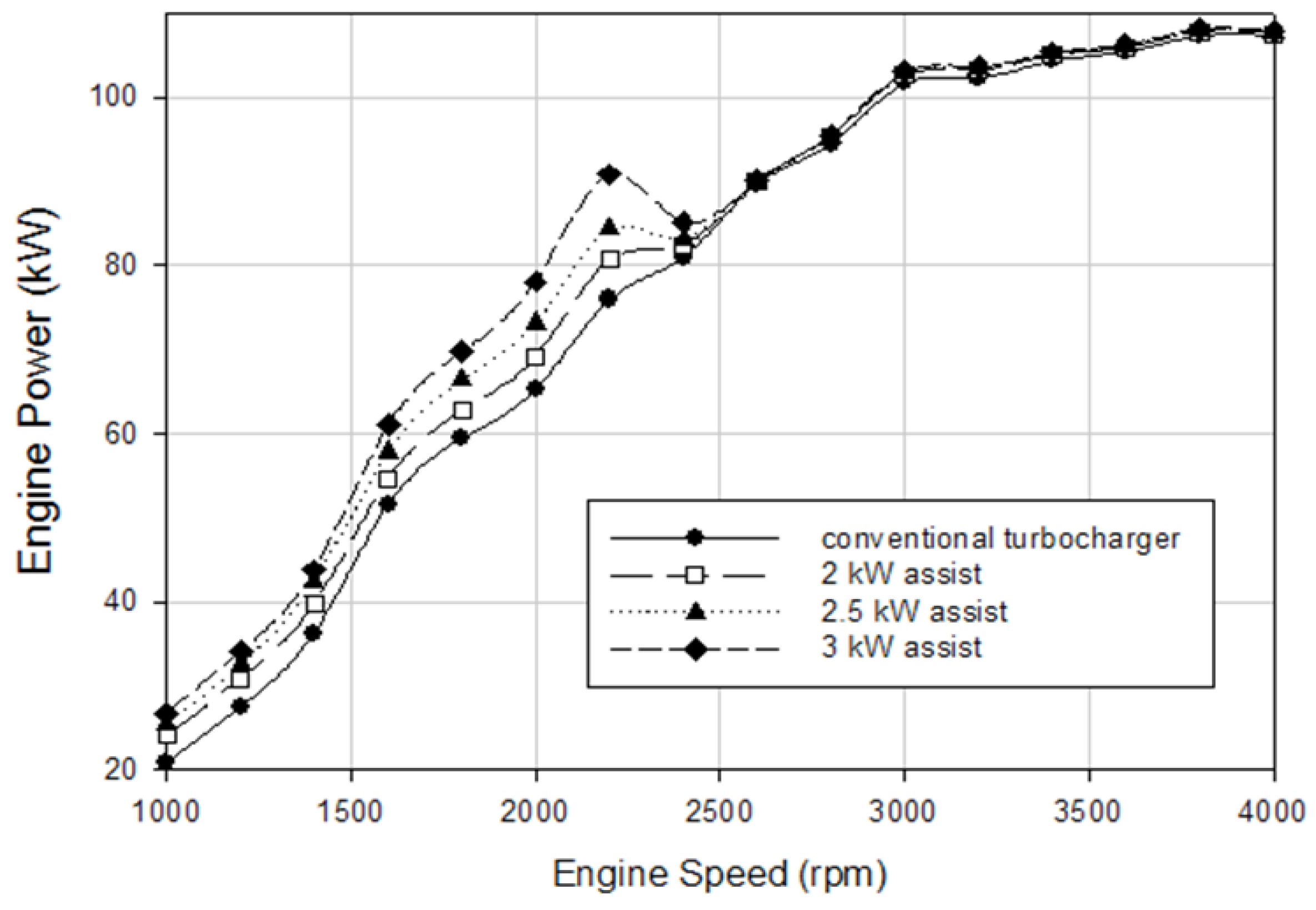

The effects of different electrical power assist on engine power values according to varying engine speeds at full load conditions are presented in

Figure 8. It demonstrates a similar trend with engine torque versus engine speed graph because engine power is directly proportional to the engine torque. Therefore, the same improvements were obtained for engine power as in engine torque.

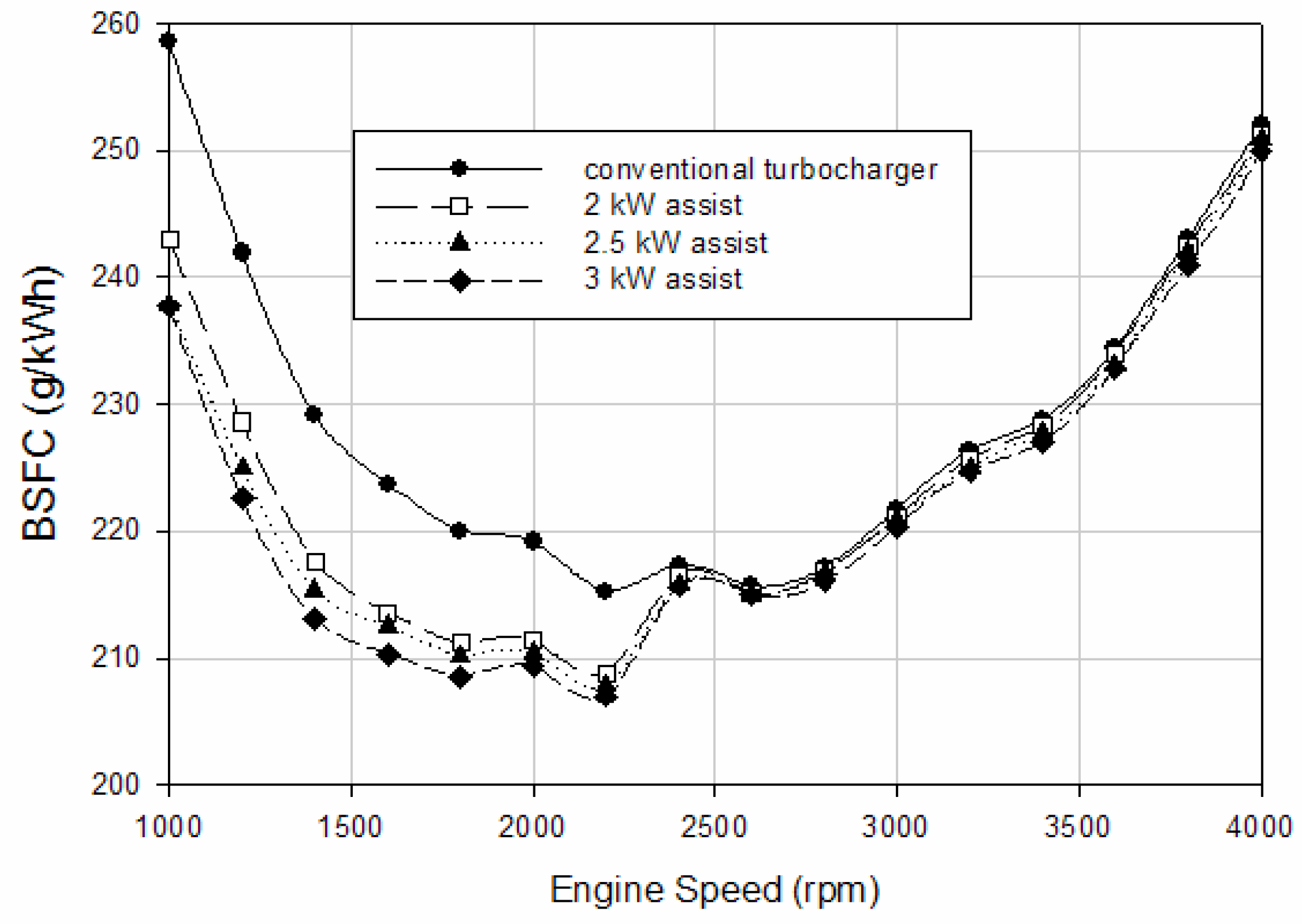

Figure 9 indicates the variation of BSFC values according to varying engine speeds for different electrical power assistance at full load conditions. BSFC was reduced with electrical power assistance where the electric device acts as a motor at a low engine speed zone. BSFC of conventional turbocharged diesel engine was improved by 6%, 8%, and 8.1% at 1000 rpm, 5.5%, 7%, and 8% at 1200 rpm, and 5%, 6%, and 7% at 1400 rpm engine speed with 2-, 2.5- and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively. The average improvement is 4.5%, 5.4%, and 6.1% with electrical power assistance as 2, 2.5, and 3 kW, respectively for the low engine speed zone. It can be stated that electrical power assist to the conventional turbocharger improves fuel efficiency during low engine speed zone.

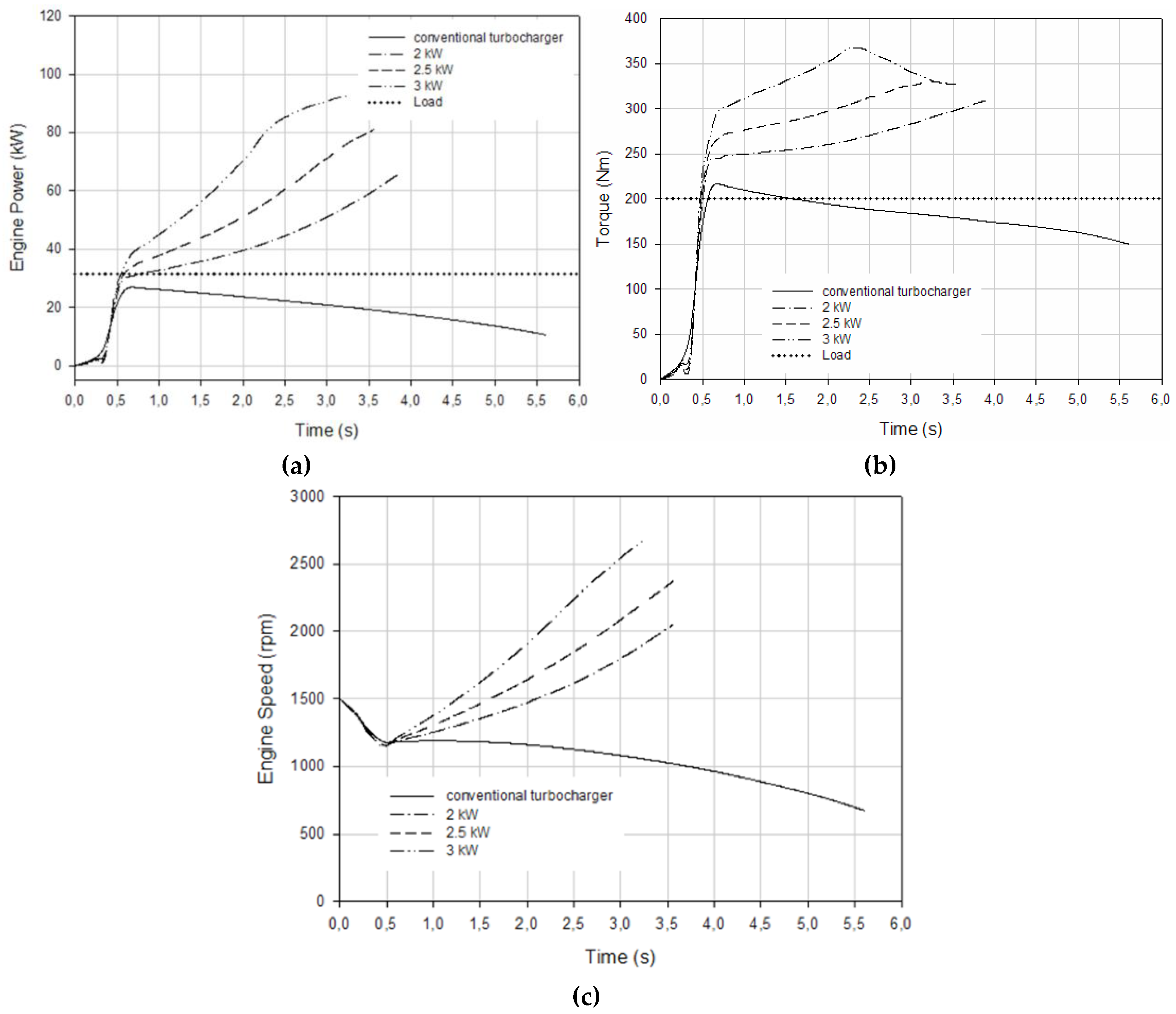

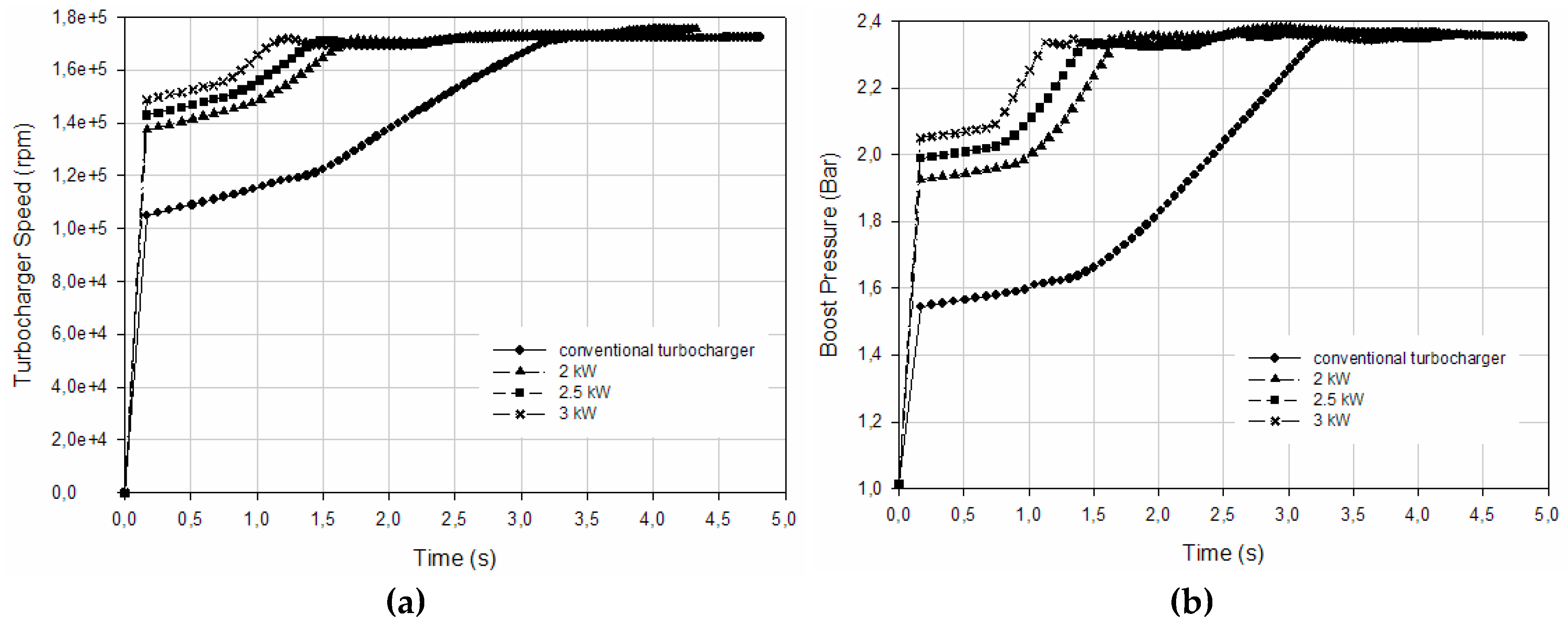

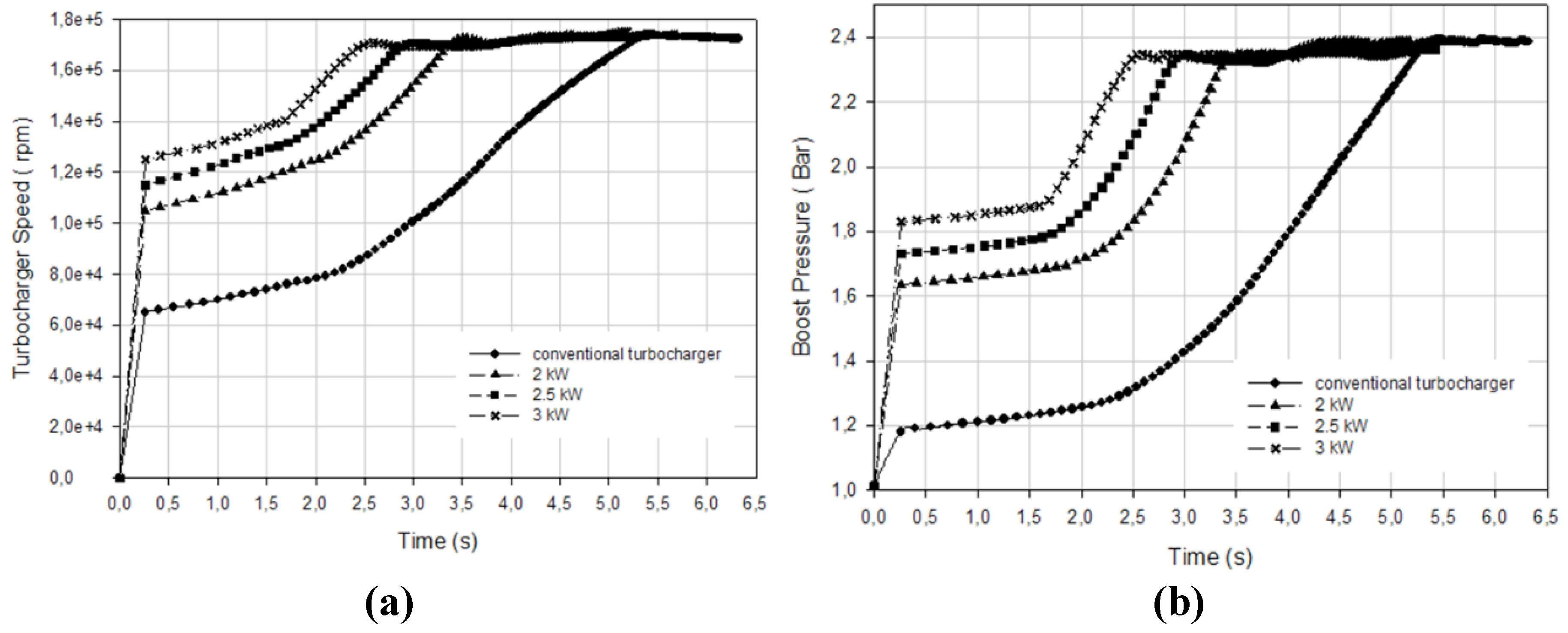

Load acceptance of the engine under transient operating conditions at a sudden load increase and different turbocharger configurations is presented in

Figure 10. The simulation introduces a 200 Nm sudden load application to the engine at 1500 rpm. Electric motors such as 2 kW, 2.5 kW, and 3 kW ensured faster boost pressure rise and therefore allowed larger quantities of the fuel to be injected into the cylinder. It is evident that the engine equipped with the electrically assisted turbocharger can accept a higher instant load. It can be stated that load acceptance of the engine was improved with electrical power assistance to the engine. Also, conventional turbocharged engine could not respond to load so engine speed decreased with respect to increase in time. Electrically assisted turbochargers could accept engine load, it took 3.75, 2.85, and 2.15 seconds for the engine to reach 2000 rpm engine speed from 1500 rpm with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively. Higher electrical power assistance resulted in a faster response to load which means a higher improvement in transient response.

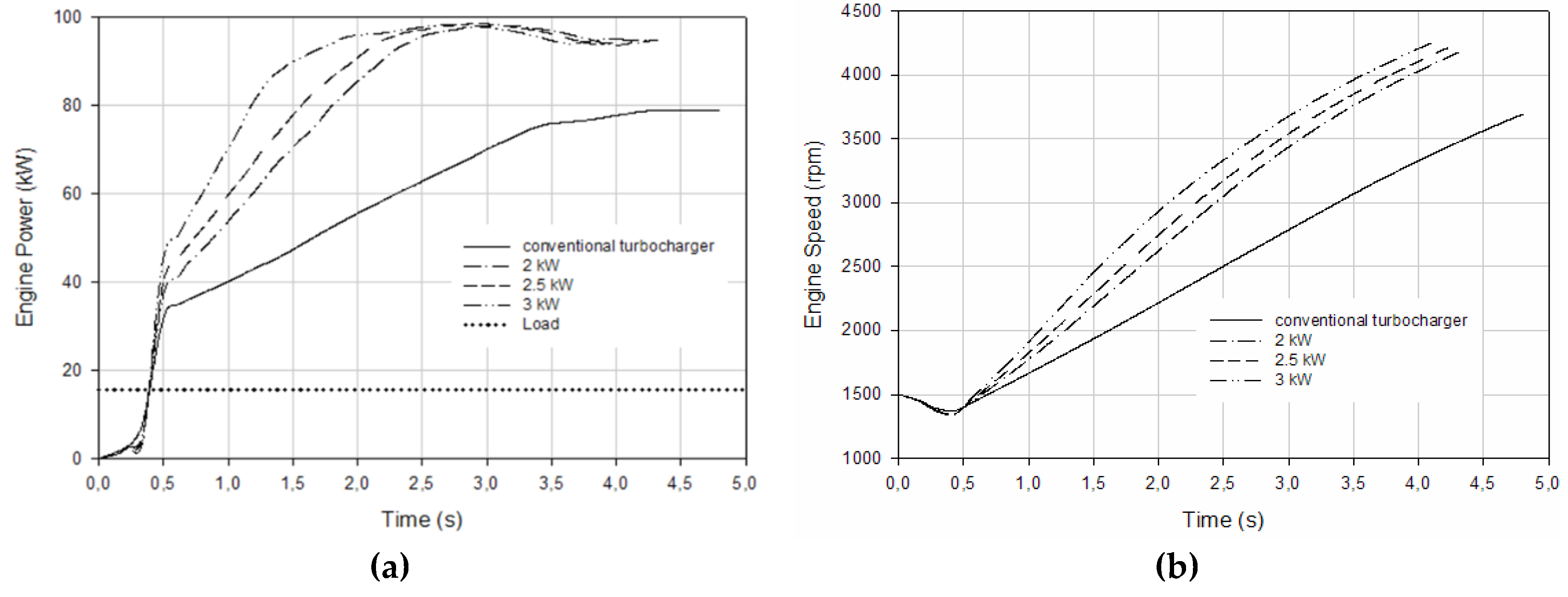

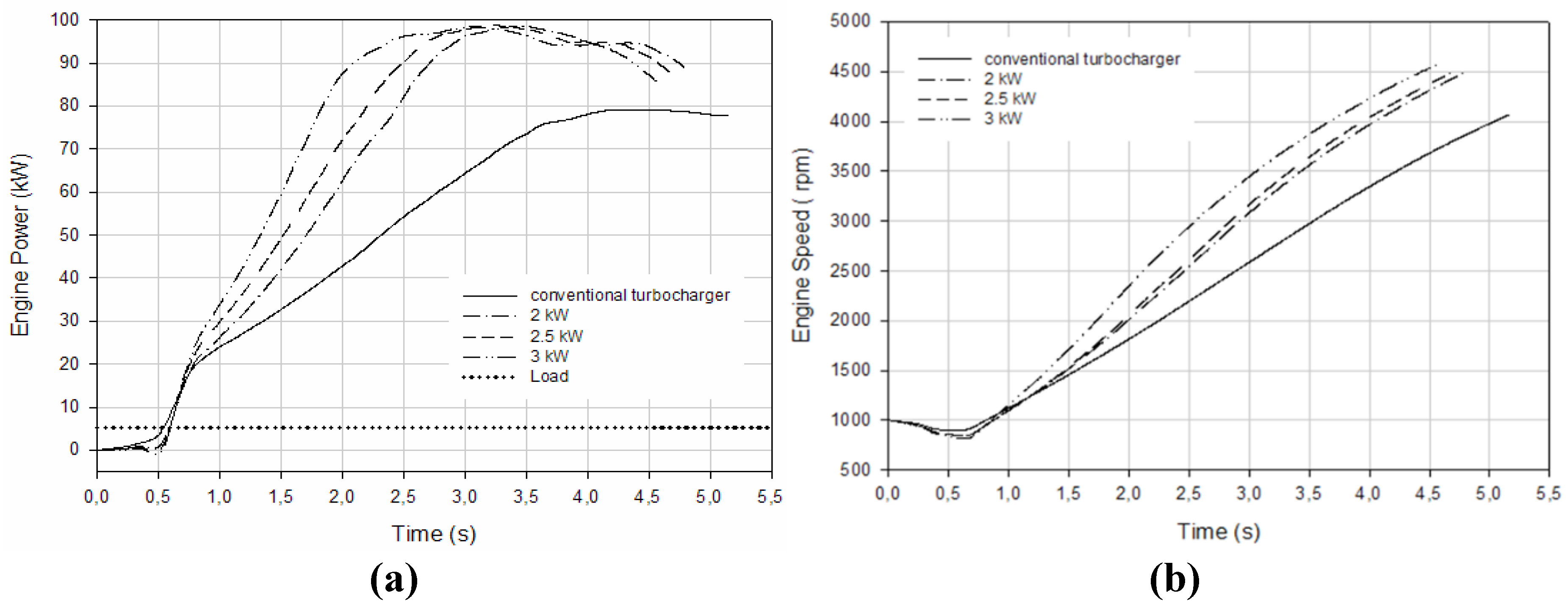

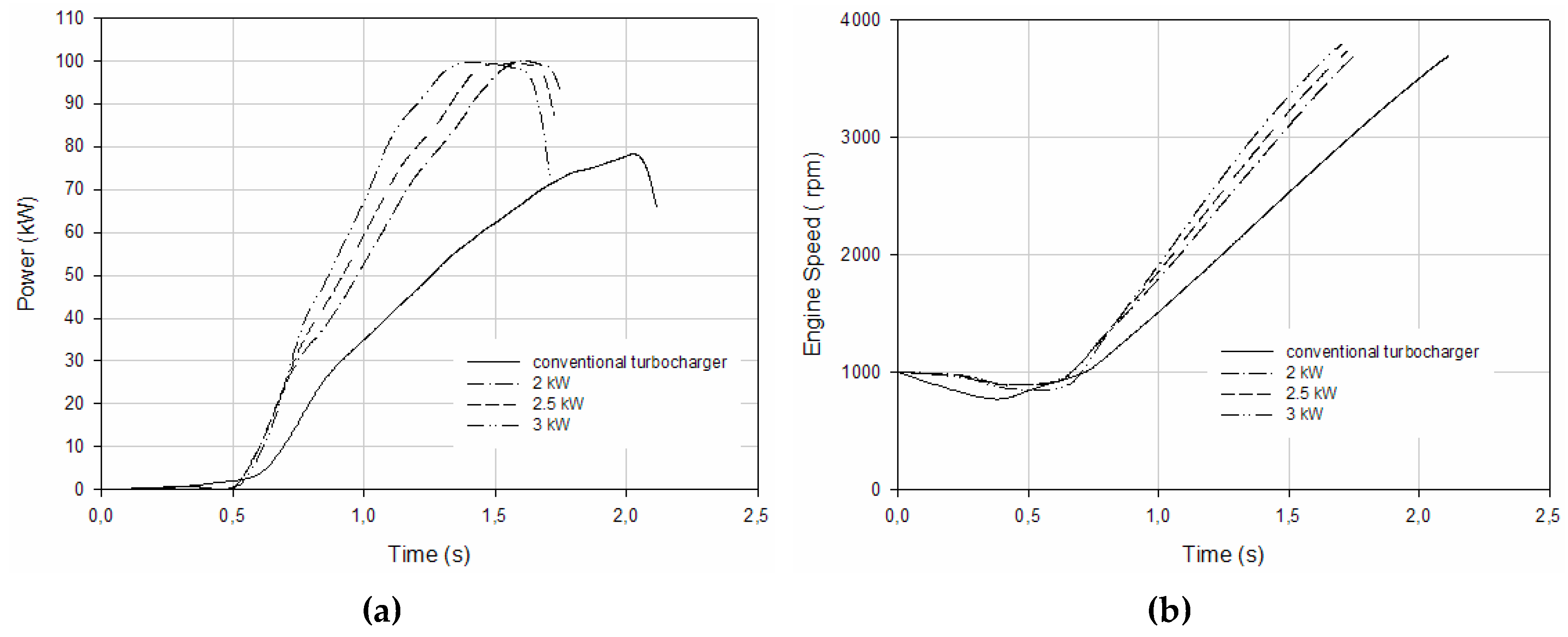

Figure 11 represents the variation of engine power and speed according to time for different electrical power assistance at under 100 Nm engine load at 1500 rpm engine speed. According to

Figure 11, it took 3 s for the conventional turbocharged engine to produce 70 kW engine power and when the electrically assisted turbochargers are used this time is reduced to 1.48, 1.27, and 1 second with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively. Simulation results revealed that engine load response time improved by 51%, 58%, and %67 with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assistance, respectively. The conventional turbocharged engine attained 3000 rpm engine speed in 3.37 s under 100 Nm load at 1500 rpm initial engine speed. This time decreased to 2.43, 2.07, and 2.07 s with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively. It can be stated that the transient response of the engine was improved by up to 40% with electrical power assistance.

Figure 12 compares the transient response of the turbocharger speed and the boost pressure under 100 Nm load at 1500 rpm engine speed for different turbocharger configurations. According to the figure, it took 3.18 s for the conventional turbocharger to reach 170000 rpm rotational speed and by the time electrically assisted turbochargers were used this time reduced to 1.66, 1.42, and 1.12 seconds with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively.

Figure 12 also shows that the time required for the turbocharger to produce 2.3 bar boost pressure which is 3.12 s for the conventional turbocharger reduced to 1.61, 1.37, and 1.07 s with 2, 2.5, and 3 kW electrically assisted turbochargers. Since boost pressure is a function of turbocharger speed similar trends were obtained. The effects of electrical power assistance are noticeable if the values during acceleration are examined: the turbocharger took 65% less time to reach 170000 rpm and the boost pressure took 66 % less time to reach 2.3 bar with the 3-kW electrical power assist.

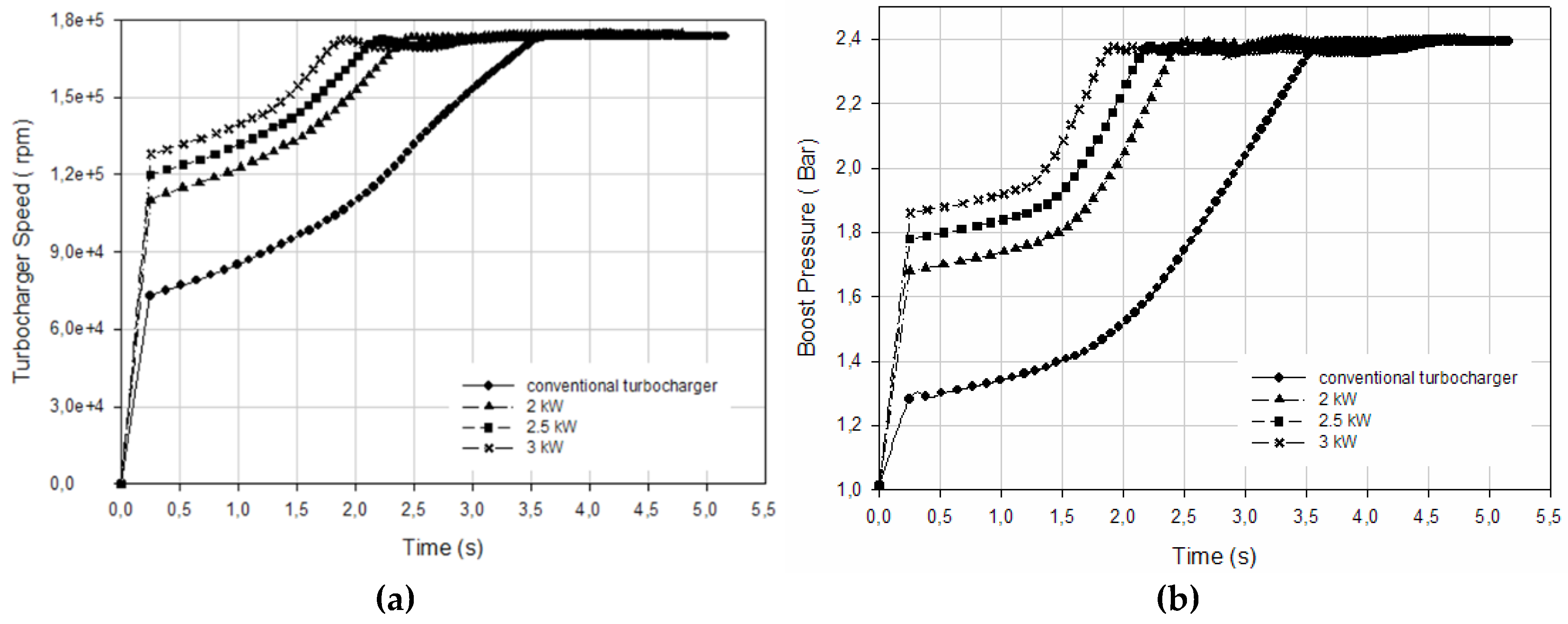

The effects of different levels of electrical power assistance on engine power output and speed over time under a 50 Nm load at 1000 rpm are illustrated in

Figure 13. The data show that a conventional turbocharged engine requires 2.68 seconds to reach 60 kW of power. In contrast, with the implementation of electrically assisted turbochargers, this time decreases to 1.94 seconds with 2 kW of electrical power assist, 1.74 seconds with 2.5 kW, and 1.50 seconds with 3 kW. The simulation results indicate that the engine load response time improves by 28%, 35%, and 44% with 2, 2.5, and 3 kW of electrical power assistance, respectively. Also, the conventional turbocharged engine achieves a speed of 2000 rpm in 2.25 seconds under a 50 Nm load at an initial speed of 1000 rpm. This time is reduced to 1.98 seconds with 2 kW of electrical power assist, 1.87 seconds with 2.5 kW, and 1.73 seconds with 3 kW. This indicates an improvement in the transient response of the engine by 12%, 17%, and 23% with the corresponding levels of electrical power assistance.

Figure 14 compares the transient response of the turbocharger speed and the boost pressure under 50 Nm load at 1000 rpm engine speed for different turbocharger configurations. According to figure, it took 3.47 s for the conventional turbocharger to reach 170000 rpm which is the maximum rotational speed, and when electrically assisted turbochargers are used this time is reduced to 2.36, 2.12, and 1.81 seconds with 2, 2.5, and 3 kW, respectively. The time required for the turbocharger to produce 2.3 bar that is peak boost pressure which is 3.43 s for conventional turbocharger reduced to 2.33, 2.08, and 1.78 s with 2, 2.5, and 3 kW electrically assisted turbochargers. Since boost pressure is a function of turbocharger speed similar trends were obtained. Simulation results indicated that turbocharger response time improved by 32%, 39%, and 48% with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assistance, respectively.

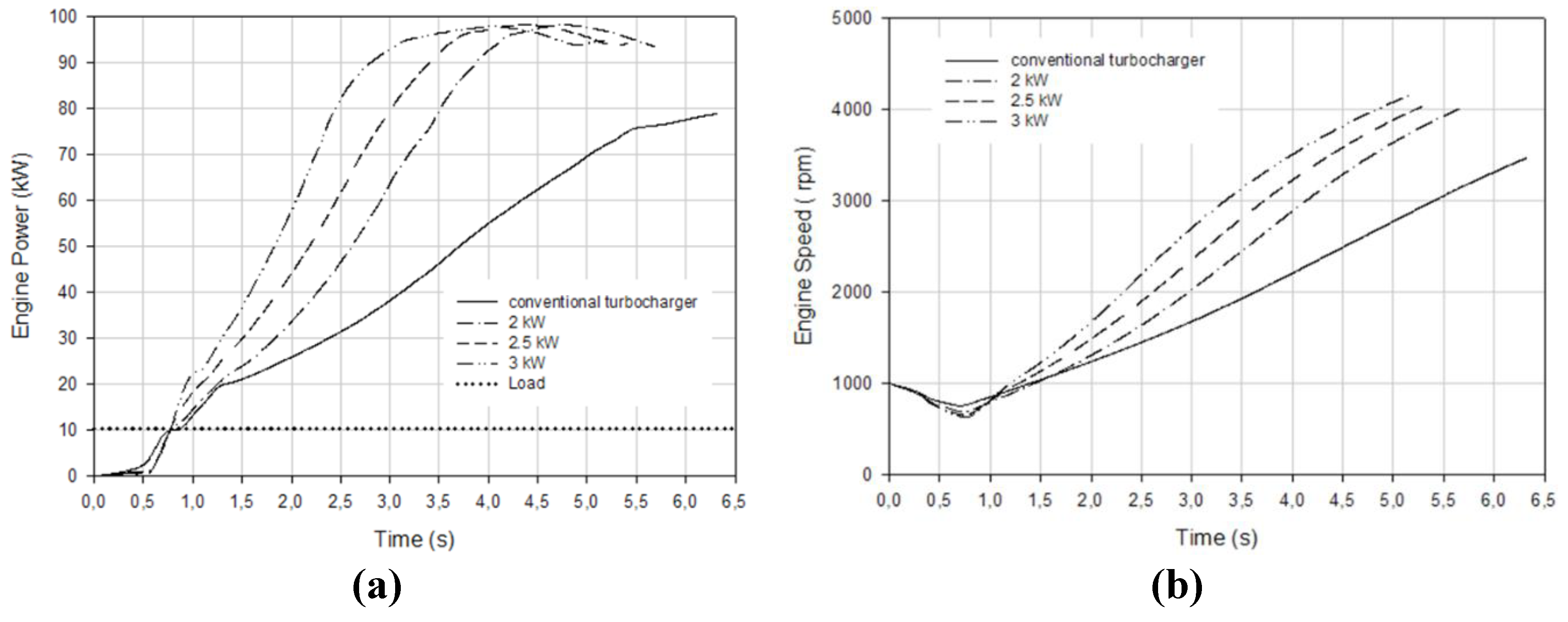

Figure 15 represents the variation of engine power and speed according to time for different electrical power assistance at under 100 Nm engine load at 1000 rpm engine speed. According to figure, it took 4.32 s for the conventional turbocharged engine to produce 60 kW engine power, and when the electrically assisted turbochargers are used this time is reduced to 2.90, 2.44, and 2.04 seconds with 2, 2.5, and 3 kW electrical power assist, respectively. Simulation results revealed that engine load response time improved by 33%, 44%, and %53 with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assistance, respectively. Also, the conventional turbocharged engine reached 2000 rpm engine speed in 3.63 s. This time decreased to 2.97, 2.61, and 2.32 s with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively. It can be stated that the transient response of the engine was improved 11%, 20%, and 36%with 2, 2.5, and 3 kW, respectively.

Figure 16 compares the transient response of the turbocharger speed and the boost pressure under 100 Nm load at 1000 rpm engine speed for different turbocharger configurations. According to figure, it took 5.19 s for the conventional turbocharger to reach 170000 rpm which is the maximum rotational speed, and when electrically assisted turbochargers are used this time is reduced to 3.37, 2.88, and 2.46 seconds with 2, 2.5, and 3 kW electrical power assist, respectively. Also, the time required for the turbocharger to produce 2.3 bar which is peak boost pressure which is 5.15 s for conventional turbocharger reduced to 3.37, 2.88, and 2.46 s with 2, 2.5, and 3 kW. Since boost pressure is a function of turbocharger speed similar trends were obtained. Simulation results indicated that turbocharger response time improved by 35%, 45%, and %53 with 2, 2.5, and 3 kW, respectively.

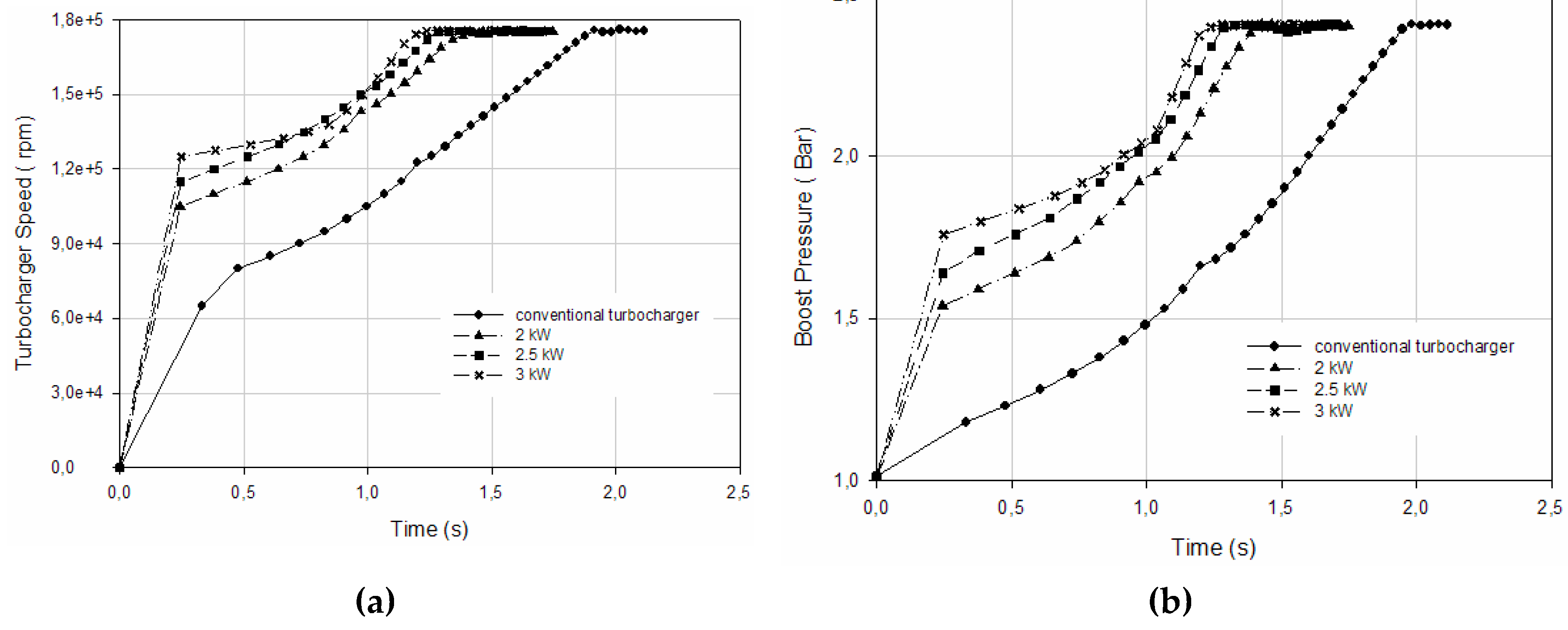

The effects of different electrical power assist on engine power and speed values according to time for vehicle acceleration from 1000 rpm initial engine speed is presented in

Figure 17. According to figure, it took 1.46 s for conventional turbocharged engine to produce 60 kW engine power and when the electrically assisted turbochargers are used this time reduced to 1.07, 1.01, and 0.95 seconds with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively. Simulation results showed that engine load response time improved 27%, 31%, and 35% with 2, 2.5, and 3 kW, respectively. Also, conventional turbocharged engine reached 2000 rpm engine speed in 1.25 s under vehicle acceleration from 1000 rpm initial engine speed. This time reduced to 1.09, 1.05, and 1.03 s with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively. It can be stated that the transient response of the engine was improved by 13%, 16%, and 18% with 2, 2.5, and 3 kW, respectively.

Figure 18 compares the transient response of the turbocharger speed and the boost pressure under vehicle acceleration from 1000 rpm initial engine speed for different turbocharger configurations. According to the figure, it took 1.84 s for the conventional turbocharger to reach 170000 rpm which is the maximum rotational speed, and when electrically assisted turbochargers are used, this time is reduced to 1.32, 1.22, and 1.14 seconds with 2-, 2.5-, and 3-kW electrical power assist, respectively. The figure also shows that the time required for the turbocharger to produce 2.3 bar which is peak boost pressure which is 1.87 s for conventional turbocharger reduced to 1.31, 1.21, and 1.15 s with 2, 2.5, and 3 kW, respectively. Since boost pressure is a function of turbocharger speed similar trends were obtained. Simulation results indicated that turbocharger response time improved by 30%, 35%, and 39% with 2, 2.5, and 3 kW, respectively.

The boost pressure increase at lower engine speeds is primarily attributed to the immediate torque delivery of the electric motor, which compensates for the traditional exhaust-energy delay in spooling up the turbocharger. This early boost activation improves the air-fuel ratio available for combustion, directly enhancing torque and reducing brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC). For instance, a 3 kW electrical assist raised boost pressure by 58.9% at 1000 rpm, translating to an approximate 28% increase in engine torque—effects that cannot be achieved via conventional turbochargers alone at such low speeds.

Turbocharger speed increases in parallel with boost pressure, confirming the direct influence of electric motor support on compressor dynamics. The engine reaches maximum turbocharger speed 800 rpm earlier with 3 kW assist, reducing delay in torque buildup and improving drivability under load. These dynamics are particularly beneficial in urban and off-road applications where frequent accelerations from low rpm are common.

Furthermore, the reduction in turbine inlet and outlet temperatures with electrical assistance highlights a thermodynamic benefit of lower exhaust backpressure and optimized combustion. This may also positively influence engine durability and emissions control.

Comparison with the works of Kolmanovsky and Stefanopoulou [

38,

39], as well as Tavčar et al. [

36], confirms the consistency of the findings but also emphasizes the expanded scope of this study, which uniquely considers power-matched assistance levels and practical load simulations. These features strengthen the applicability of EAT systems to production-level engine control strategies.