Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Concrete Mix Design and Material Properties

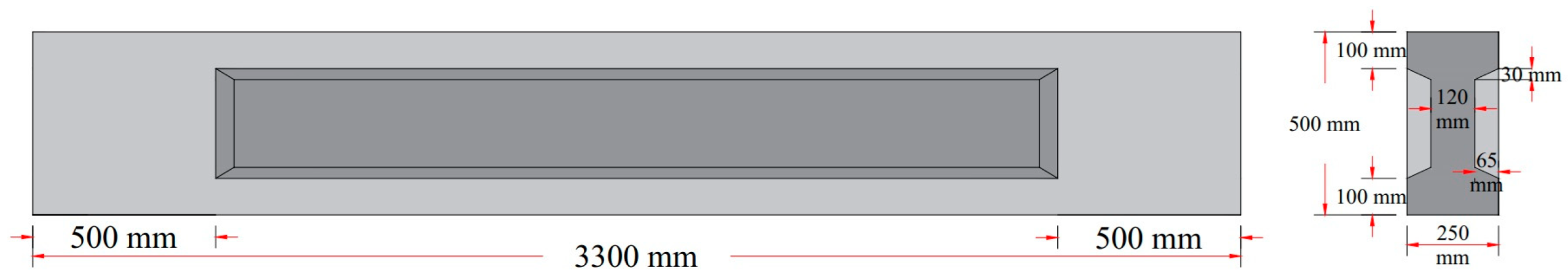

2.2. Specimen’s Shape, Size, and Dimensions

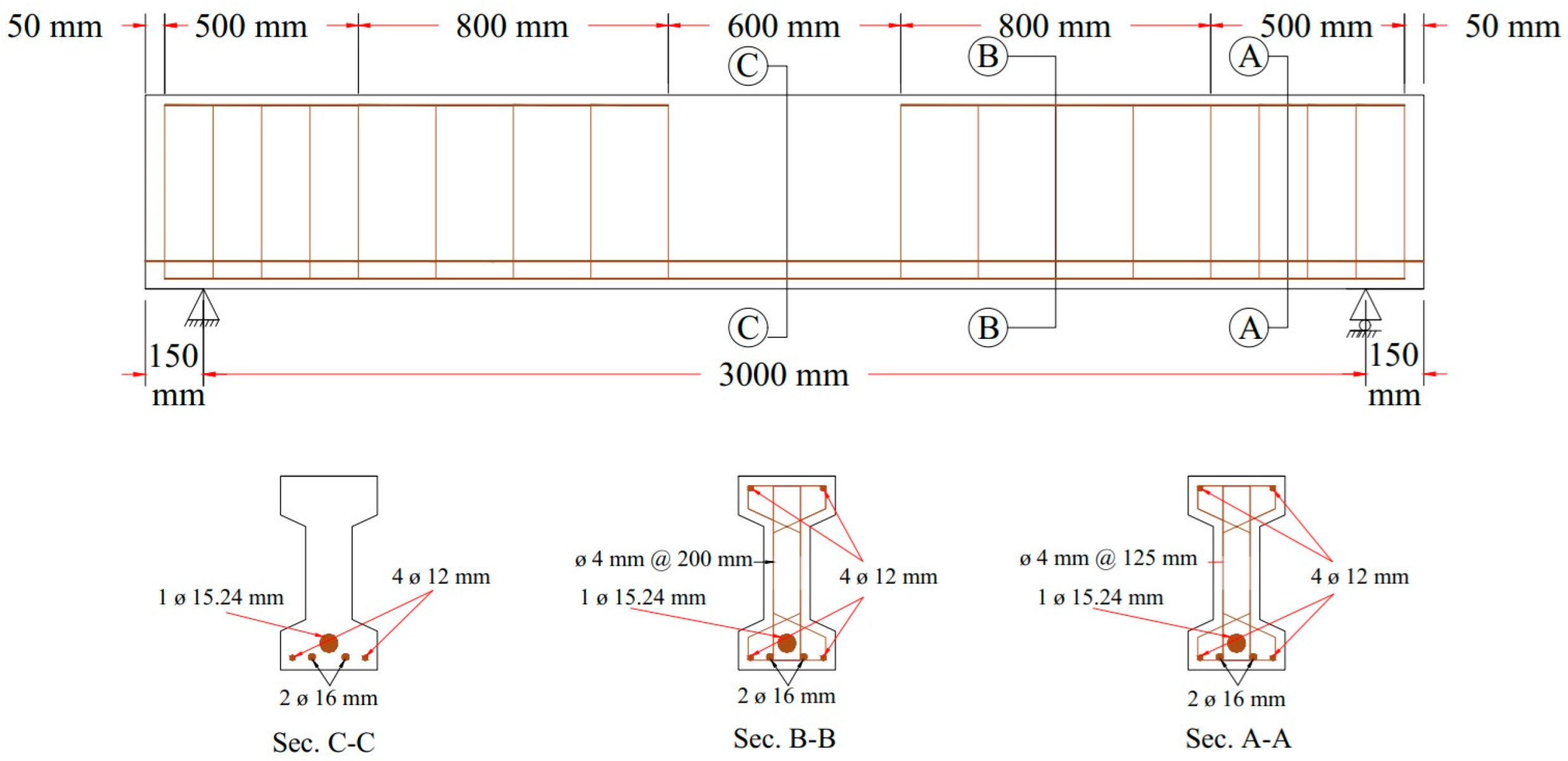

2.3. Prestressing and Reinforcement Detail

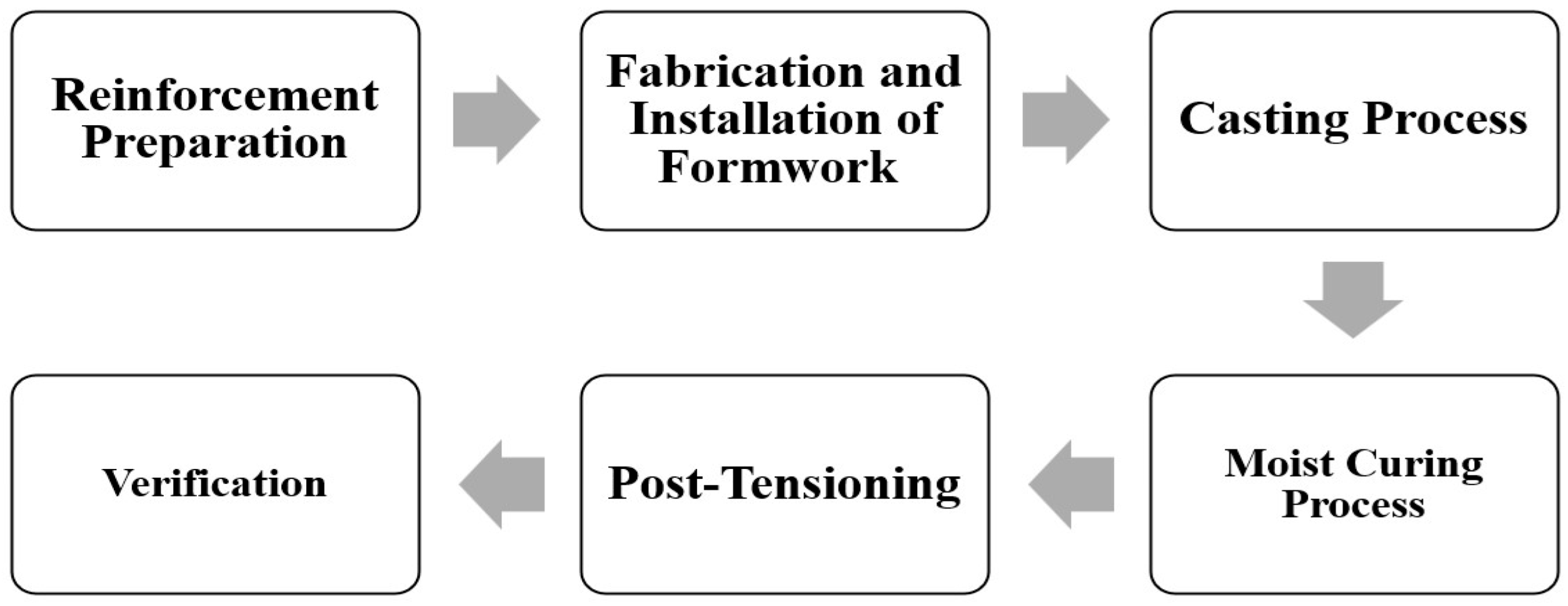

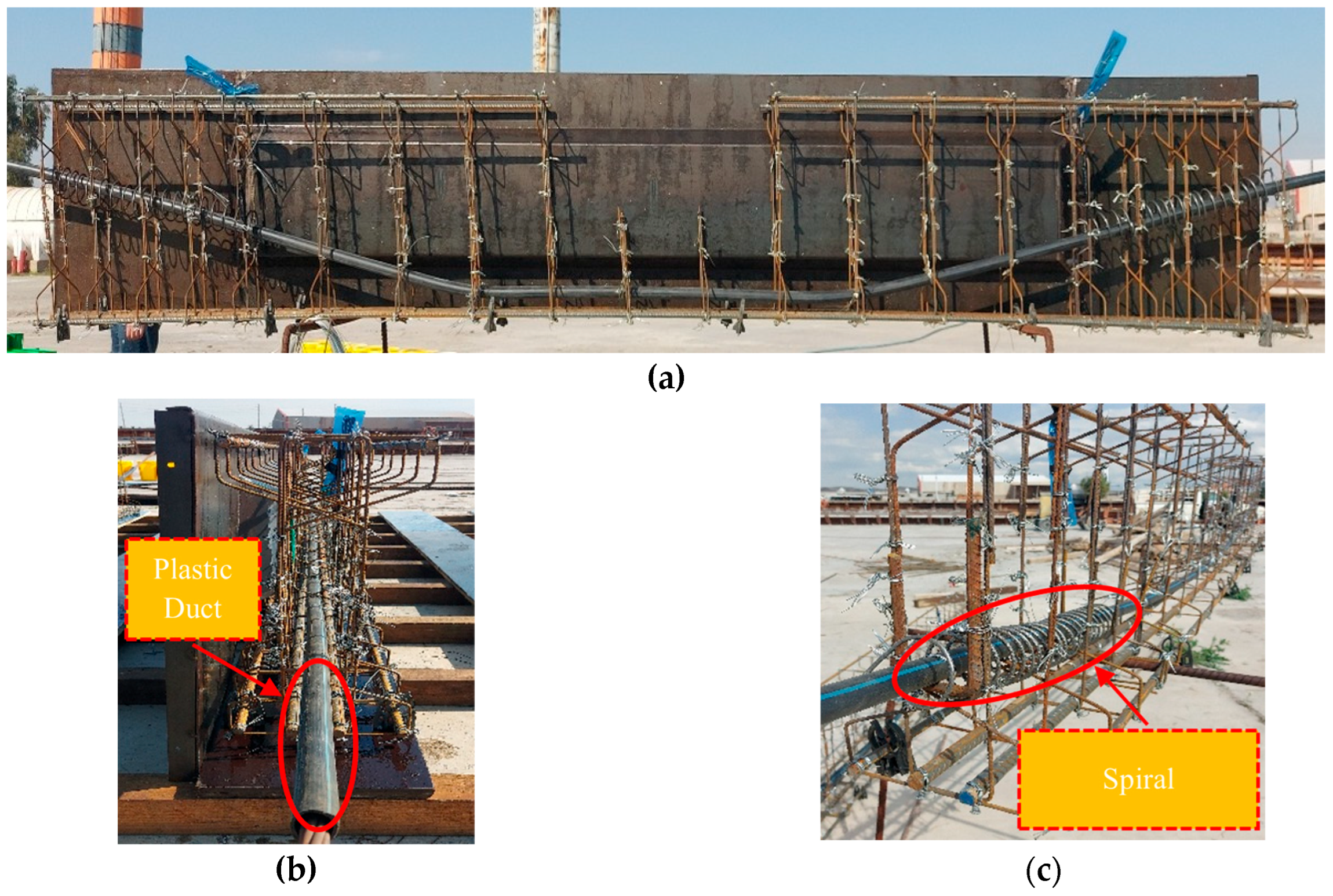

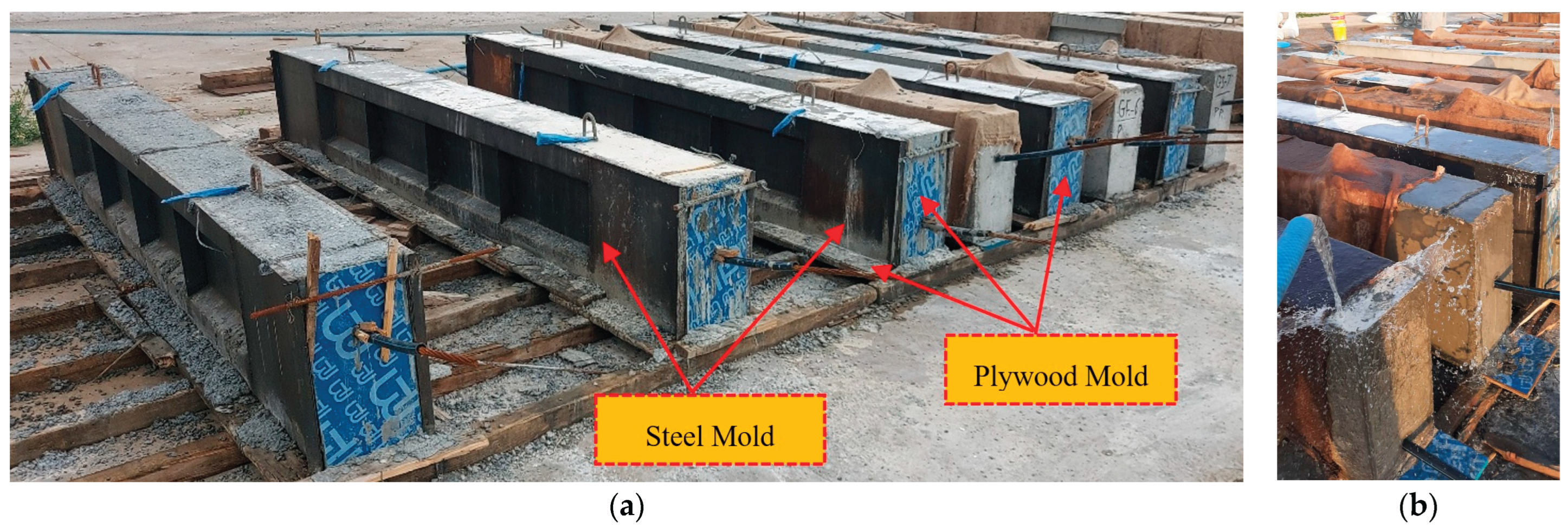

2.4. Tested Specimens Preparation

2.5. Experimental Variables

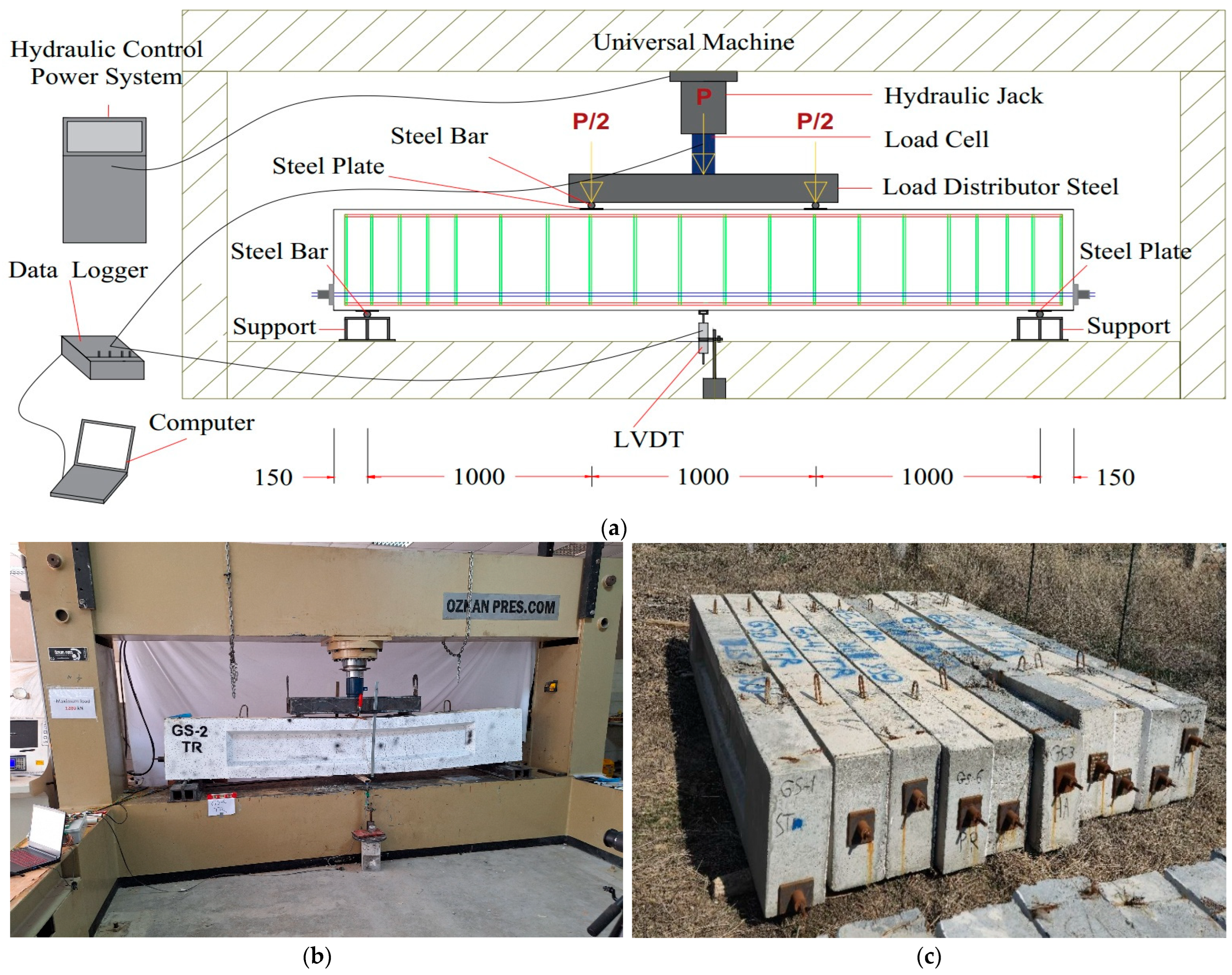

2.6. Test Setup and Instrumentation

2.7. Experimental Procedure

3. Experimental Program

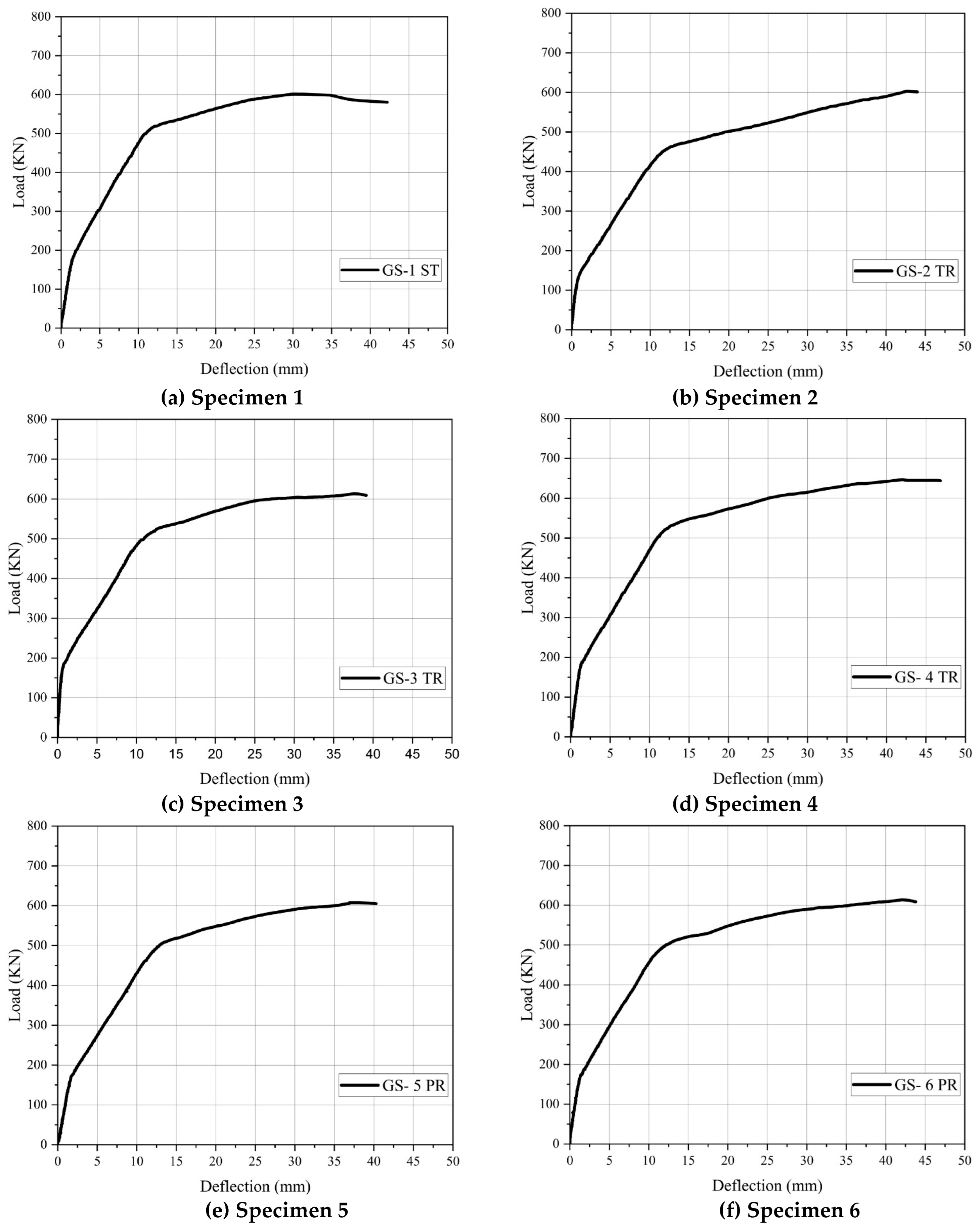

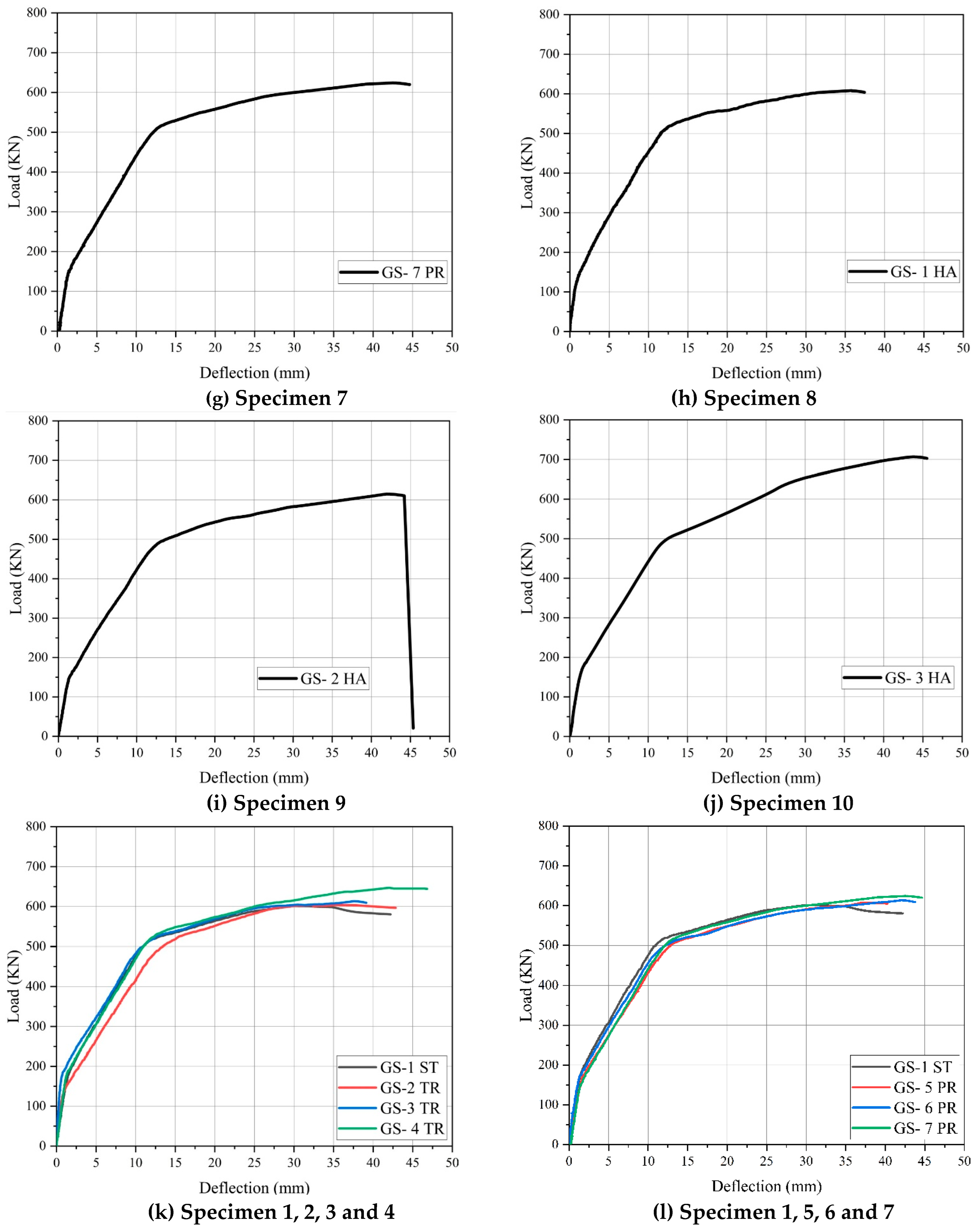

3.1. Load–Deflection Curves

3.3. Crack Patterns and Mode of Failure

4. Conclusions

- The tendon profile layout significantly influenced the failure process in unbonded prestressed concrete I-girders.

- The shear behavior of the specimens was characterized by three stages: the elastic stage, elastic-plastic stage, and the plastic (ductility) stage. All specimens experienced shear failure.

- The first visible cracks occurred at approximately 20.83% to 30.11% of the ultimate load, averaging around 26.17% for all specimens.

- Among the specimens with a trapezoidal tendon profile, the greater increase in ultimate load was observed in specimen GF-4 TR, which showed a 12.80% improvement compared to the control beam. For the specimens with a parabolic tendon profile, an increase of 6.36% in ultimate load was recorded, with specimen GF-7 PR achieving a maximum increase of 22.83 kN over the control beam. Specimens featuring a harped tendon profile also demonstrated greater increase in ultimate load, with specimen GF-3 HA showing a significant 29.36% improvement over the control beam. These results highlight the beneficial impact of tendon profile layout on the load-carrying capacity of prestressed concrete beams.

- The vertical deflection measurements of the tendon profile specimens revealed distinct variations. For the trapezoidal tendon profile, specimen GF-2 TR exhibited the smallest deflection at 35.14 mm, which was 17.13% greater than that of the GS-1 ST. Among the parabolic tendon profile specimens, GF-5 PR showed the least deflection at 37.24 mm, 22.97% higher than GS-1 ST, while for harped tendon profile, GF-1 HA recorded a lower deflection of 35.82 mm, 19.4% greater than GS-1 ST. These findings highlight the influence of tendon profile shapes on deflection behavior, offering insights into their structural performance.

- The study revealed that each tendon profile shape (trapezoidal, parabolic, harped) exhibited the highest ultimate load capacity and deflection when the eccentricity was set at ee = -80 mm, while the eccentricity of ee = +80 mm resulted in the lowest load capacity and deflection. Notably, specimen GF-1 HA, featuring the harped tendon profile, displayed the greatest ultimate load capacity, while specimen GF-2 TR, with the trapezoidal tendon profile, recorded the smallest deflection. These findings highlight the significant influence of tendon profile shape and eccentricity on the structural performance of the specimens.

- The experimental results of girders tested with optimized tendon profiles indicated that their performance was enhanced remarkably in comparison with the control beam. These girders could carry higher loads, These girders could sustain larger loads due to the more effective distribution of the prestressing forces along the girder length. The optimum tendon arrangements lead to more homogeneous distribution of stresses inside the concrete, fully utilizing a larger part of the cross-section. Such an increased stress distribution not only raises the structural effect and efficiency and improves the girder’s ductility but also prolongs the bridge structure’s service life. This study demonstrates the advantage of adopting optimized tendon profiles to enhance the performance and durability of prestressed concrete bridge girders.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Darwin, David.; Dolan, C.W.. Design of Concrete Structures; 16th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education, 2021; ISBN 9781260575118.

- Hao, H.; Bi, K.; Chen, W.; Pham, T.M.; Li, J. Towards next Generation Design of Sustainable, Durable, Multi-Hazard Resistant, Resilient, and Smart Civil Engineering Structures. Eng Struct 2023, 277, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilson, A.H. Design of Prestressed Concrete; Second Edition.; Wiley, 1987.

- Naser, A.F.; Zonglin, W. Strengthening of Jiamusi Pre-Stressed Concrete Highway Bridge by Using External Post-Tensioning Technology in China. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 2010, 5, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Naser, A.F.; Zonglin, W. Finite Element and Experimental Analysis and Evaluation of Static and Dynamic Responses of Oblique Pre-Stressed Concrete Box Girder Bridge. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology 2013, 6, 3642–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.B.M.; Rice, J.A.; Hamilton, H.R.; Consolazio, G.R. Damage Identification in Unbonded Tendons for Post-Tensioned Bridges. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Experimental Structural Engineering; August 2015; Vol. 2015-August, p. 8.

- Corven, J.; Natio, C.; Pessiki, S. Designing and Detailing Post-Tensioned Bridges to Accommodate Nondestructive Evaluation; 2018.

- Fuzier, J.-P.; Ganz, H.-R.; Matt, P. Durability Of-Tensioning Tendons; Case Postale 88, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland, 2006.

- Nusrath, F.R.; Satheesh, V.S.; Manigandan, M.; Suresh, B.S. An Overview on Tendon Layout for Prestressed Concrete Beams. IJISET-International Journal of Innovative Science, Engineering & Technology 2015, 2, 944. [Google Scholar]

- Rupf, M.; Fernández Ruiz, M.; Muttoni, A. Post-Tensioned Girders with Low Amounts of Shear Reinforcement: Shear Strength and Influence of Flanges. Eng Struct 2013, 56, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, P.; Huber, T.; Kollegger, J. Experimental and Theoretical Study on the Shear Behavior of Single- and Multi-Span T- and I-Shaped Post-Tensioned Beams. Structural Concrete 2020, 21, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.F.; Muttoni, A. Shear Strength of Thin-Webbed Post-Tensioned Beams. ACI Struct J 2008, 105, 308–317. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, S.; Ahsan, R. Design of Prestressed Concrete I-Girder Bridge Superstructure Using Optimization Algorithm. IABSE-JSCE Joint Conference on Advances in Bridge Engineering-II 2010, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Xiong, W.; Ye, J. Simplified Design Formula for the Shear Capacity of Prestressed Concrete T-Beams Strengthened by Steel Plates. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 2025, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, P.; Wien, T.U.; Huber, T.; Kollegger, J. Shear Behavior of Post-Tensioned Concrete Beams with a Low Amount of Transverse Reinforcement. In Proceedings of the fib Symposium 2016 Cape Town; Cape Town, November 1 2016.

- Hillebrand, M.; Hegger, J. Fatigue Testing of Shear Reinforcement in Prestressed Concrete T-Beams of Bridges. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisa, A.S.; Kotrasova, K.; Sabol, P.; Mihaliková, M.; Attia, M.G. Experimental and Numerical Study of Strengthening Prestressed Reinforced Concrete Beams Using Different Techniques. Buildings 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Jiang, H.; Wang, B.; Zhuge, P. Experimental Study on Shear Performance of Concrete Beams Reinforced with Externally Unbonded Prestressed CFRP Tendons. Fibers 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Lu, J.; Li, G. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of Shear Performance of 16 m Full-Scale Prestressed Hollow Core Slabs. Infrastructures (Basel) 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancy, A.; Stolarski, A.; Zychowicz, J. Experimental and Numerical Research of Post-Tensioned Concrete Beams. Materials 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.-S.; Jun, B.-K.; Shin, D.-I.; Lee, J.-Y. Shear Capacity of Post-Tensioning Pre-Stressed Concrete Beams with High Strength Stirrups. International Journal of Structural and Civil Engineering Research 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, G.A.; Eisa, A.S.; Purcz, P.; Ručinský, R.; El-Feky, M.H. Effect of External Tendon Profile on Improving Structural Performance of RC Beams. Buildings 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqub, M.A.; Czaderski, C.; Matthys, S. Shear Strengthening of Precast Prestressed Bridge I-Girders Using Shape Memory Reinforcement. Eng Struct 2024, 305, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hu, Z.; Yi, J.; Dai, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X. Shear Behavior of Corroded Post-Tensioned Prestressed Concrete Beams with Full/Insufficient Grouting. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 2020, 24, 1881–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Xue, W. Experimental Investigation on Shear Behavior of FRP Post-Tensioned Concrete Beams without Stirrups. Eng Struct 2021, 244, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Ma, Z.J.; Wang, J.; Bao, Y. Post-Cracking Shear Behaviour of Concrete Beams Strengthened with Externally Prestresssed Tendons. Structures 2020, 23, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Xiong, W.; Ye, J. Simplified Design Formula for the Shear Capacity of Prestressed Concrete T-Beams Strengthened by Steel Plates. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 2025, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.H.; Aziz, O.Q. Shear Behavior of Dry and Epoxied Joints in Precast Concrete Segmental Box Girder Bridges under Direct Shear Loading. Eng Struct 2019, 182, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.H.; Aziz, O.Q. Influence of Intensity & Eccentricity of Posttensioning Force and Concrete Strength on Shear Behavior of Epoxied Joints in Segmental Box Girder Bridges. Constr Build Mater 2019, 197, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.L.; Kwan, A.K.H. Practical Determination of Prestress Tendon Profile by Load-Balancing Method. HKIE Transactions Hong Kong Institution of Engineers 2006, 13, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagarapu, D.C.K.; Venkat, L. Genetic Algorithm Based Optimum Design of Prestressed Concrete Beam. International Journal for Computational Civil and Structural Engineering 2013, 3, 644–654. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.A.; Pathak, K.K.; Dindorkar, N. CABLE LAYOUT DESIGN OF ONE WAY PRESTRESSED SLABS USING FEM. Journal of Engineering, Science and Management Education 2010, 2, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Colajanni, P.; Recupero, A.; Spinella, N. Design Procedure for Prestressed Concrete Beams. Computers and Concrete 2014, 13, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.S.; Khurd, V.G. Effect of Prestressing Force, Cable Profile and Eccentricity on Post Tensioned Beam. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology 2017, 4, 626–632. [Google Scholar]

- Naser, A.F. Optimum Design of Vertical Steel Tendons Profile Layout of Post-Tensioning Concrete Bridges: Fem Static Analysis. ARPN Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 2018, 13, 9244–9256. [Google Scholar]

- Yakov, Z.; Amir, O. Layout Optimization of Post-Tensioned Cables in Concrete Slabs. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 2021, 63, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, U.M. Effect of Tendon Profile on Deflections in Prestressed Concrete Beams Using C Programme. International Journal of Computer Science and Engineering 2021, 8, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, G.A.; Eisa, A.S.; Purcz, P.; Ručinský, R.; El-Feky, M.H. Effect of External Tendon Profile on Improving Structural Performance of RC Beams. Buildings 2022, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, P.; Wien, T.U.; Huber, P.; Kollegger, J. Shear Strength of Post-Tensioned Concrete Girders with Minimum Shear Reinforcement. In Proceedings of the 11th CCC Congress HAINBURG 2015; 2015.

- Fakhrulddin Abdullah, A.; Burhan Al-Deen Abdul-Rahman, M.; Abbas Al-Attar, A. Investigate the Mechanical Characteristics and Microstructure Of-Geopolymer Concrete Exposure to High Temperatures. Journal of Rehabilitation in Civil Engineering v-n (year) 2025, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, H.M.; Oukaili, N. k.; Jomaa’h, M.M. EFFECT OF PRESTRESSING FORCE ON TORSION RESISTANCE OF CONCRETE BEAMS. Journal of Engineering 2007, 13, 1902–1918. [Google Scholar]

| Materials | Quantities |

|---|---|

| Cement (g) | 425 |

| Water (L) | 160 |

| Additive (L) | 4 |

| Fine Aggregate (kg) | 880 |

| Coarse Aggregate (kg) | 910 |

| W/C | 0.38 |

| Slump (mm) | 150-180 |

| Maximum Aggregate Size (mm) | 19 |

| Type | Diameter (mm) | Area (mm2) |

Yield Stress (MPa) |

Ultimate Strength (MPa) |

Maximum Elongation (%) |

Modulus of Elasticity (MPa) |

Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strand | 15.26 | 140.54 | - | 2018 | 4.28 | 196,370 | ASTM A416/A416M |

| Deformed bar | 15.66 | 194.27 | 605 | 696 | 19 | 200,000 | ASTM A615/A615M |

| Deformed bar | 11.74 | 108.28 | 595 | 673 | 20 | 200,000 | ASTM A615/A615M |

| Steel wire | 4.37 | 15 | 700 | 710 | - | 200,000 | ASTM A1068/A1068M |

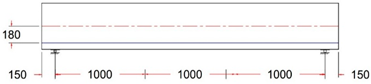

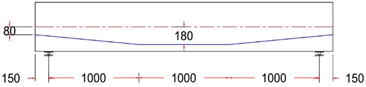

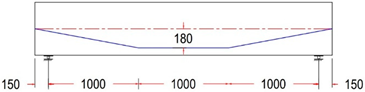

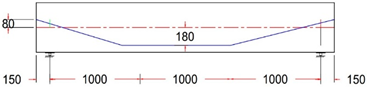

| Name of the Beam | Name of Tendon Profile | Tendon Profile Layout, Units in (mm) |

|---|---|---|

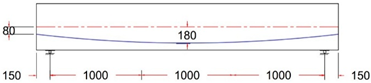

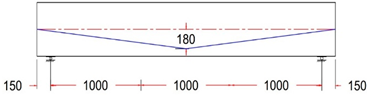

| G-1 ST Control Beam |

Straight Tendon Profile With e = 180 mm |

|

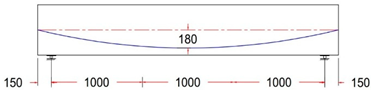

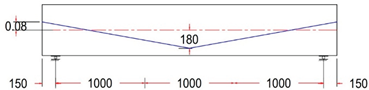

| GF-2 TR | Trapezoidal Tendon Profile With ee = +80 mm |

|

| GF-3 TR | Trapezoidal Tendon Profile With ee = 0 mm |

|

| GF-4 TR | Trapezoidal Tendon Profile With ee = −80 mm |

|

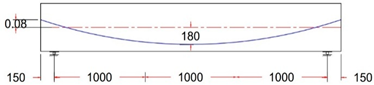

| GF-5 PR | Parabolic Tendon Profile With ee = +80 mm |

|

| GF-6 PR | Parabolic Tendon Profile With ee = 0 mm |

|

| GF-7 PR | Parabolic Tendon Profile With ee = −80 mm |

|

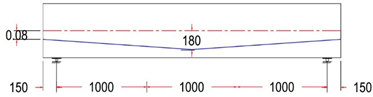

| GF-1 HA | Harped Tendon Profile With ee = +80 mm |

|

| GF-2 HA | Harped Tendon Profile With ee = 0 mm |

|

| GF-3 HA | Harped Tendon Profile With ee = −80 mm |

|

| Specimen Name | First Crack Load (kN) |

First Crack Deflection (mm) |

Ultimate Load (kN) | Ultimate Load Deflection (mm) |

Pcr/Pu % |

Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | ∆CR | Pu | ∆u | |||

| GS-1 ST | 167.17 | 1.36 | 601.17 | 30.1 | 27.81% | Shear a |

| GS-2 TR | 137.98 | 0.98 | 603.03 | 42.59 | 22.88% | Shear a |

| GS-3 TR | 184.73 | 0.79 | 613.42 | 37.59 | 30.11% | Shear a |

| GS-4 TR | 188.72 | 1.44 | 647.08 | 42 | 29.16% | Shear a |

| GS-5 PR | 178.60 | 2 | 607.43 | 37.24 | 29.40% | Shear a |

| GS-6 PR | 183.95 | 1.68 | 613.60 | 42.04 | 29.98% | Shear a |

| GS-7 PR | 151.20 | 1.43 | 624 | 42.46 | 24.23% | Shear a |

| GS-1 HA | 126.73 | 0.86 | 608.40 | 35.82 | 20.83% | Shear a |

| GS-2 HA | 145.88 | 1.30 | 615 | 41.95 | 23.72% | Shear a |

| GS-3 HA | 166.48 | 1.52 | 706.5 | 43.81 | 23.56% | Shear a |

| Compared Specimen | Increase in Ultimate Load |

Increase In Ultimate Load Deflection |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (KN) | % | (mm) | % | |

| GS-1 ST and GS-2 TR | 1.86 | 0.31% | 12.49 | 41.50% |

| GS-1 ST and GS-3 TR | 12.25 | 2.04% | 7.49 | 24.88% |

| GS-1 ST and GS-4 TR | 45.91 | 7.64% | 11.9 | 39.53% |

| GS-1 ST and GS-5 PR | 6.26 | 1.04% | 6.79 | 22.56% |

| GS-1 ST and GS-6 PR | 12.43 | 2.07% | 11.94 | 39.67% |

| GS-1 ST and GS-7 PR | 22.83 | 3.80% | 12.36 | 41.06% |

| GS-1 ST and GS-1 HA | 7.23 | 1.20% | 5.72 | 19.00% |

| GS-1 ST and GS-2 HA | 13.83 | 2.30% | 11.85 | 39.37% |

| GS-1 ST and GS-3 HA | 105.33 | 17.52% | 13.71 | 45.55% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).