Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1.

- A two-level collaborative algorithm of "position synchronization-current balancing" is studied, with the position synchronization error time <3ms.

- 2.

- Dynamic synchronization technology: A high-precision dual-channel synchronization error monitoring model is established. Combined with 40 Mbps high-speed communication and a 100 ultra-short synchronization period, real-time error capture is realized. A phase compensation dynamic adjustment mechanism is innovatively introduced to effectively eliminate the displacement cumulative error caused by the phase difference, ensuring the accuracy of system operation.

- 3.

- Adaptive load balancing strategy: The causes of load imbalance such as hardware, control delay, and external interference are deeply analyzed. An intelligent current loop balancing algorithm based on deviation coupling is designed to achieve dynamic optimization of torque commands. By integrating hydraulic pressure feedforward compensation technology, a closed-loop feedback regulation system is constructed, significantly improving the load sharing accuracy and the system’s anti-interference ability.

2. Multi-Domain Coupling Modeling of Electro-Hydrostatic Actuation System

2.1. Construction of Precision Model for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (PMSM)

2.1.1. Coordinate Transformation Considering Saturation Effect

2.1.2. Coupling Model of Iron Loss and Copper Loss

2.2. Hydraulic-Mechanical Coupling Model of EHA Actuator

2.2.1. Variable-Viscosity Hydraulic Flow Model

2.2.2. Actuator Cylinder Dynamics with Clearance Nonlinearity

3. Engineering Design Architecture of Dual-Redundancy Electro-Hydrostatic Actuation System

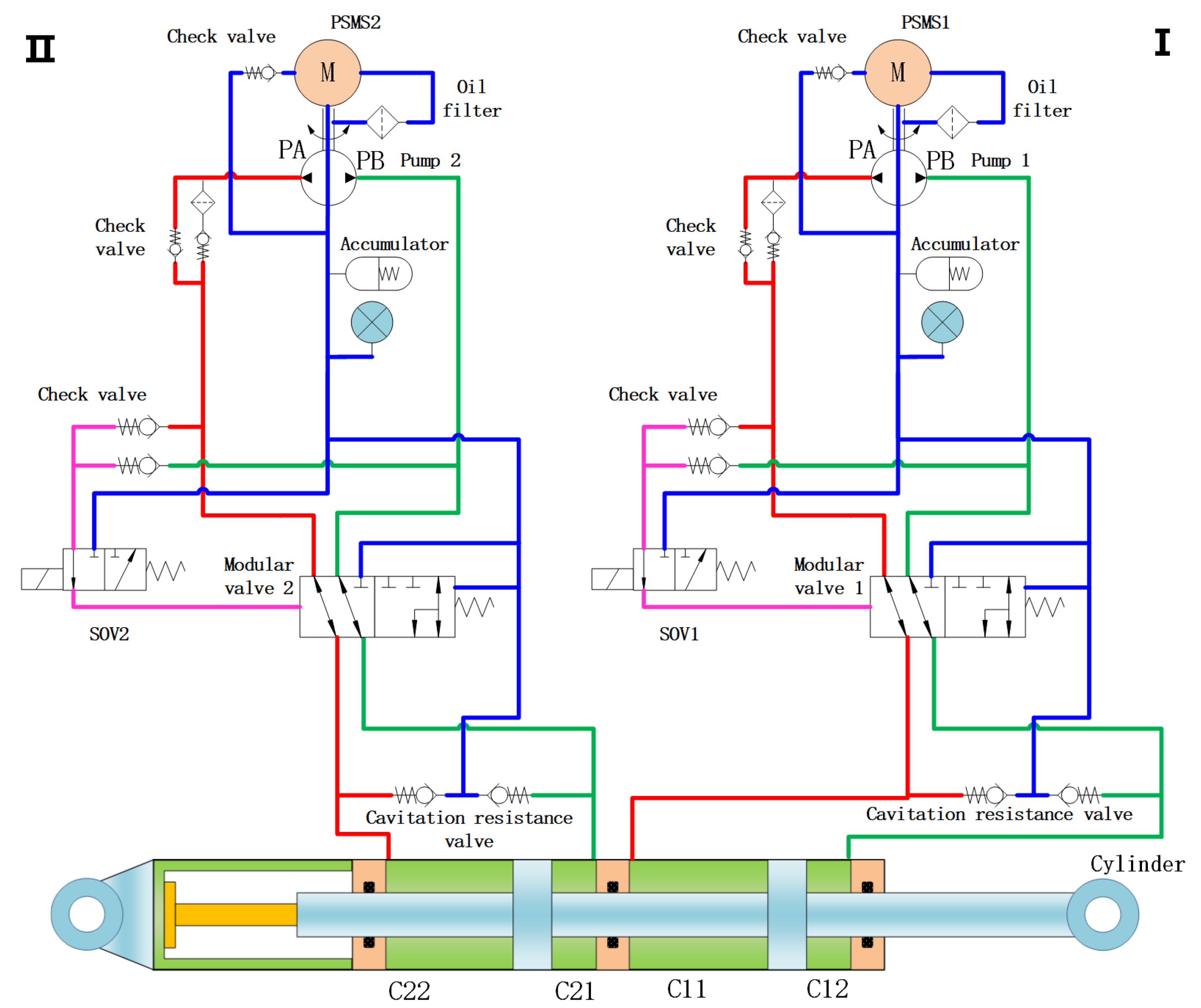

3.1. Architecture of Electro-Hydrostatic Actuator

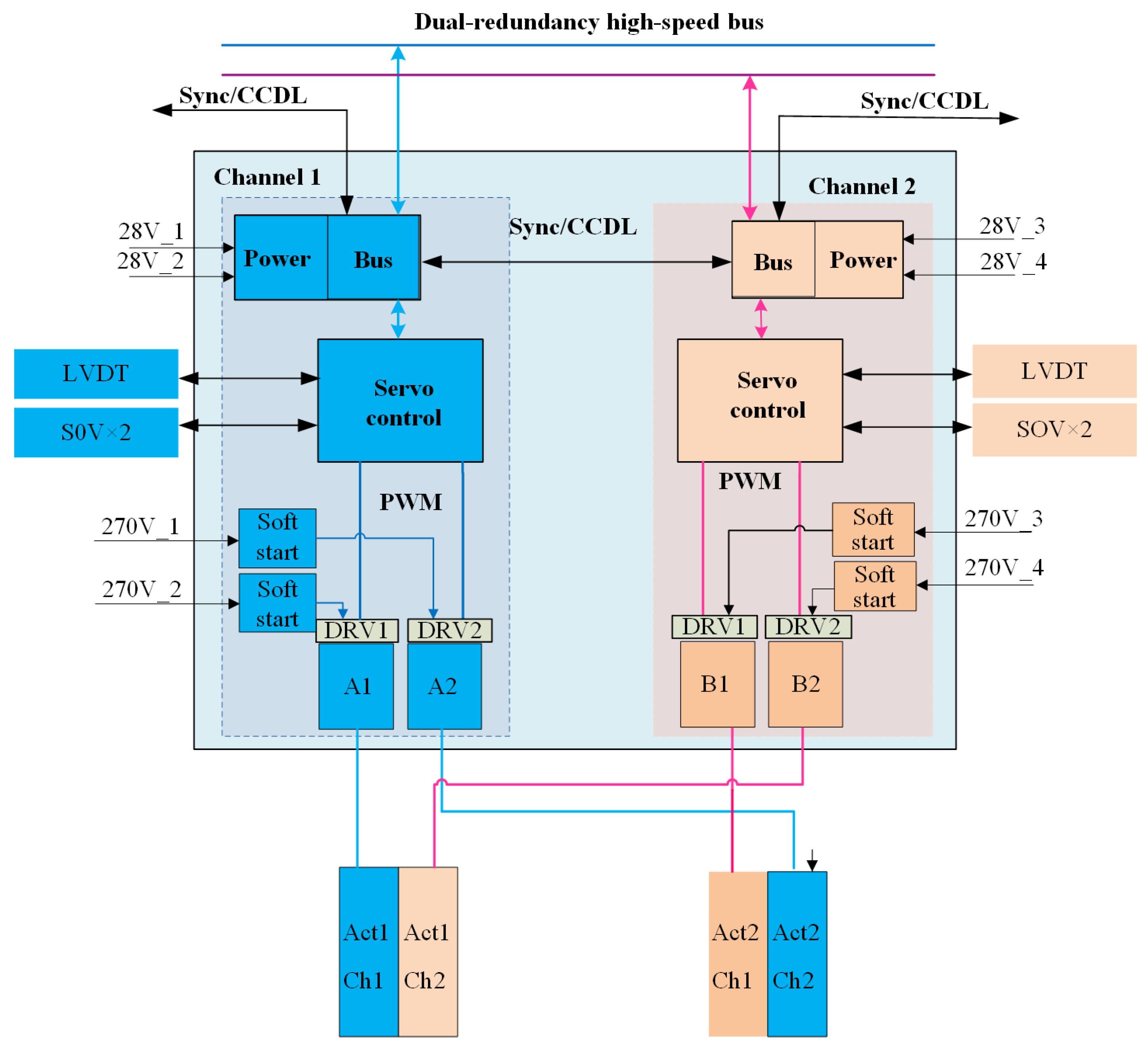

3.2. Architecture of Actuator Controller

4. Control Algorithm Design

4.1. Current Loop Vector Control and DQ-Axis Decoupling Technology

4.1.1. Vector Control and Coordinate Transformation

4.1.2. DQ-Axis Voltage Equation and Decoupling Control

4.1.3. Current Loop Control Law Design

4.1.4. Voltage Vector Synthesis Based on SVPWM

- Sector judgment: determine the sector based on the -axis voltage vector coordinates, and use the sign judgment method to control the sector judgment time within ;

- Vector action time calculation: calculate the action times of the basic voltage vectors and the zero vector action time according to the volt-second balance principle;

- Switching sequence generation: arrange the switching states according to the principle of "zero vector symmetry" to reduce switching losses, with a typical switching frequency set to 20kHz.

4.1.5. High-Speed Flux-Weakening Control Strategy

4.2. Adaptive Sliding Mode Control for Speed Loop

4.2.1. Basic Theory of Sliding Mode Control

4.2.2. Design of Adaptive Sliding Mode Controller

4.2.3. Implementation of Adaptive Mechanism

- Error-Dominated Rules:

- when is PB, increase to reduce the error quickly, and increase to improve the response speed;

- Error Change Rate-Dominated Rules:

- when is NB (the error decreases rapidly), decrease to prevent overshoot;

- Rules Near Zero Error:

- when both and are ZO, use medium gain to maintain steady-state accuracy.

| Rule Number | Condition (IF) | Conclusion (THEN) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | is NB and is NB | is NB, is NB |

| 25 | is ZO and is ZO | is ZO, is ZO |

| 49 | is PB and is PB | is PB, is PB |

4.2.4. Chattering Suppression and Stability Analysis

- Boundary layer design:

- replace the sign function with a saturation function to limit the chattering amplitude within the boundary layer ();

- Low-pass filtering:

- first-order filtering (such as cutoff frequency 500Hz) is performed on the switching control output to reduce high-frequency components;

- Adaptive adjustment:

- dynamically adjust according to the speed error to avoid chattering caused by excessive gain.

4.3. Improved Active Disturbance Rejection Control for Position Loop

4.3.1. Tracking Differentiator (TD): Command Smoothing and Differential Extraction

4.3.2. Extended State Observer (ESO): Real-Time Estimation of Total Disturbance

4.3.3. Nonlinear State Error Feedback (NLSEF): Fast Error Convergence

4.3.4. Engineering Optimization of Improved ADRC

4.4. Cooperative Control Strategy for Master-Master Working Mode

4.4.1. Dual-Channel Speed Synchronization Control

4.4.2. Dynamic Load Balancing Control

4.5. Parameter Optimization of Three-Closed-Loop Control Architecture

4.5.1. Bandwidth Allocation Principles for Control Loops

4.5.2. Current Loop Parameter Optimization

4.5.3. Speed Loop Parameter Optimization

4.5.4. ADRC Parameter Optimization for Position Loop

- Tracking differentiator(TD): (tracking speed factor), (filtering factor);

- Extended state observer(ESO):

- Nonlinear state error feedback(NLSEF): , , , .

5. Experimental Verification and Engineering Analysis

5.1. Construction of Full-Physical Experimental Platform

5.2. Verification of Control Algorithms

5.2.1. Test Setup

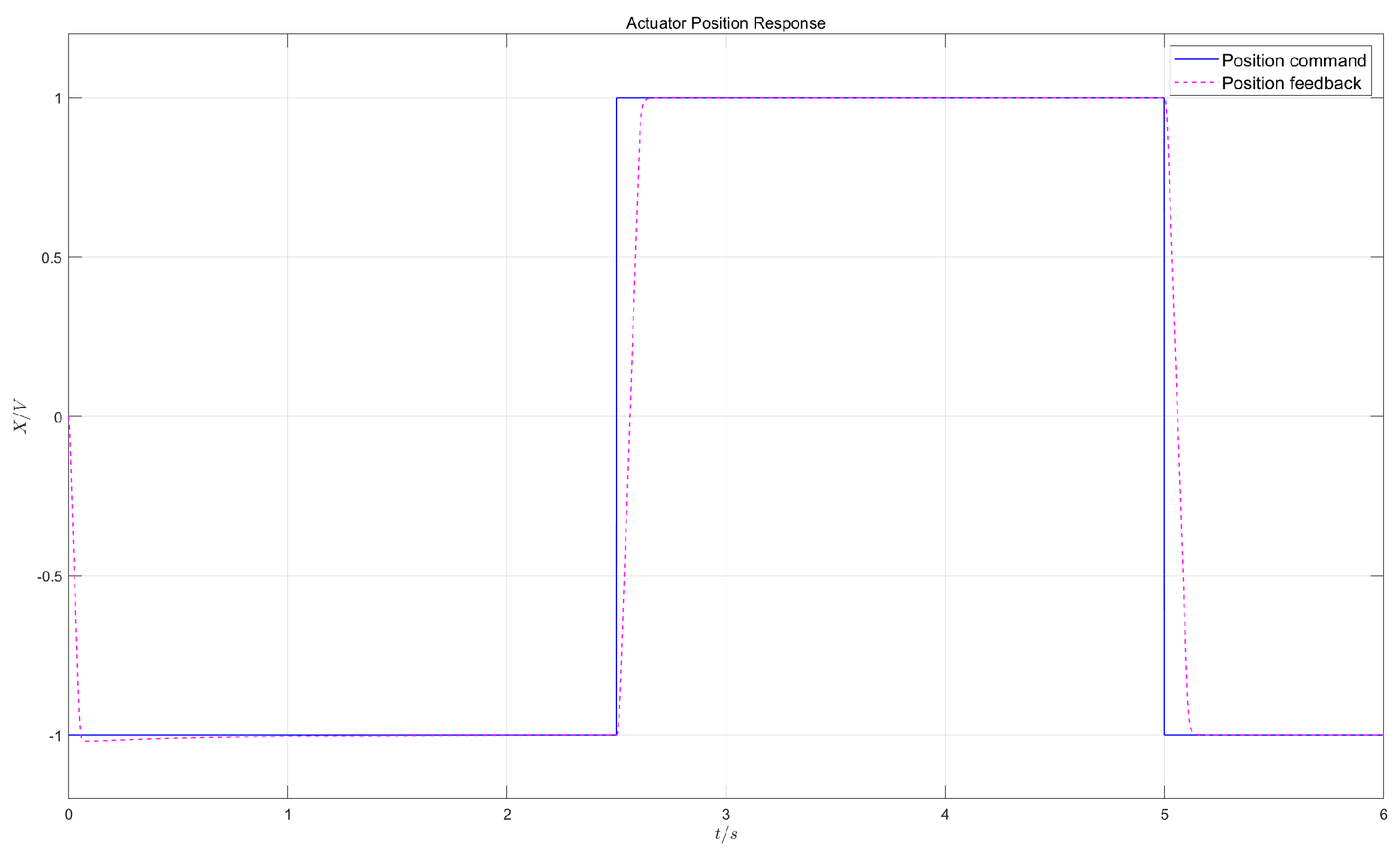

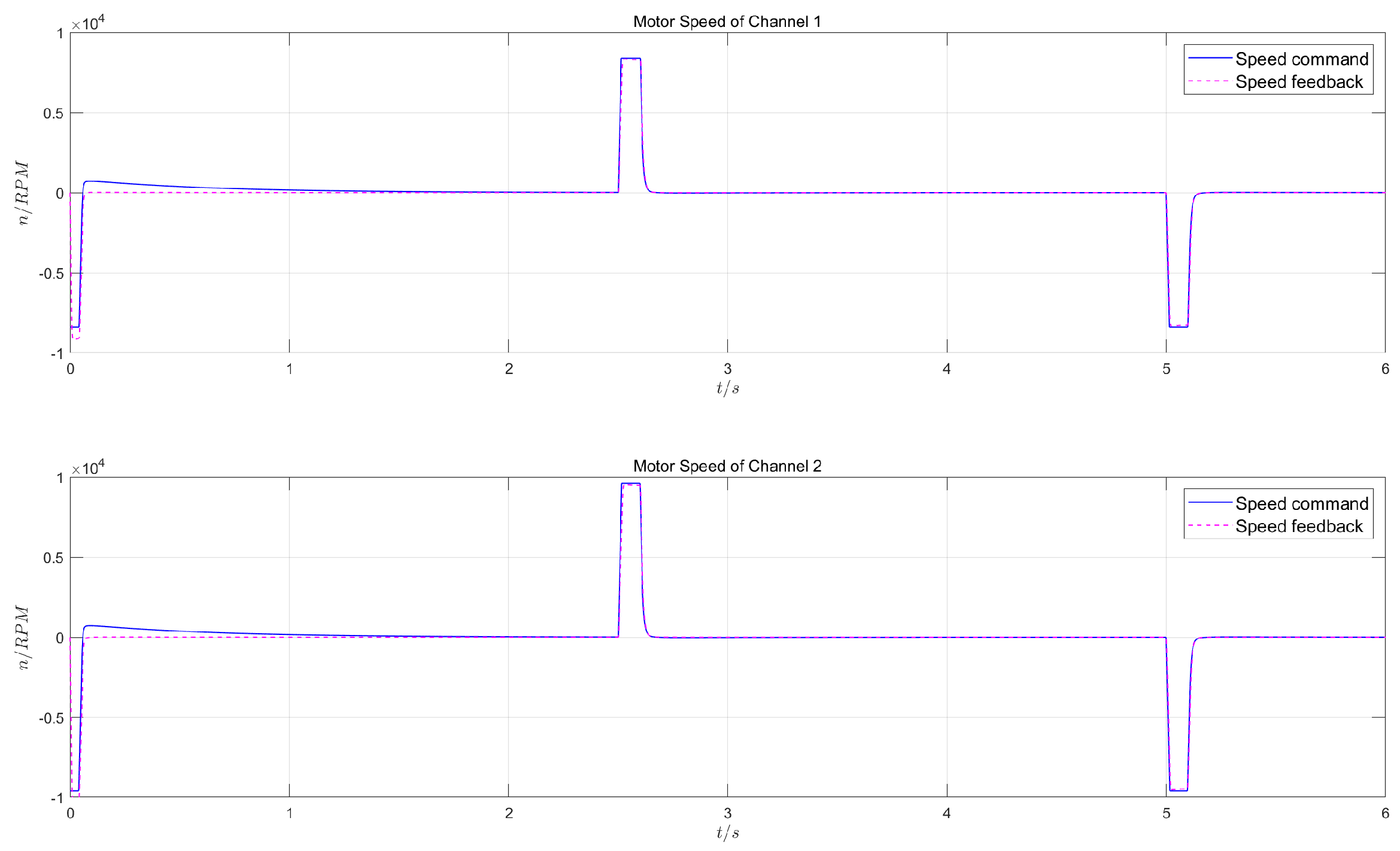

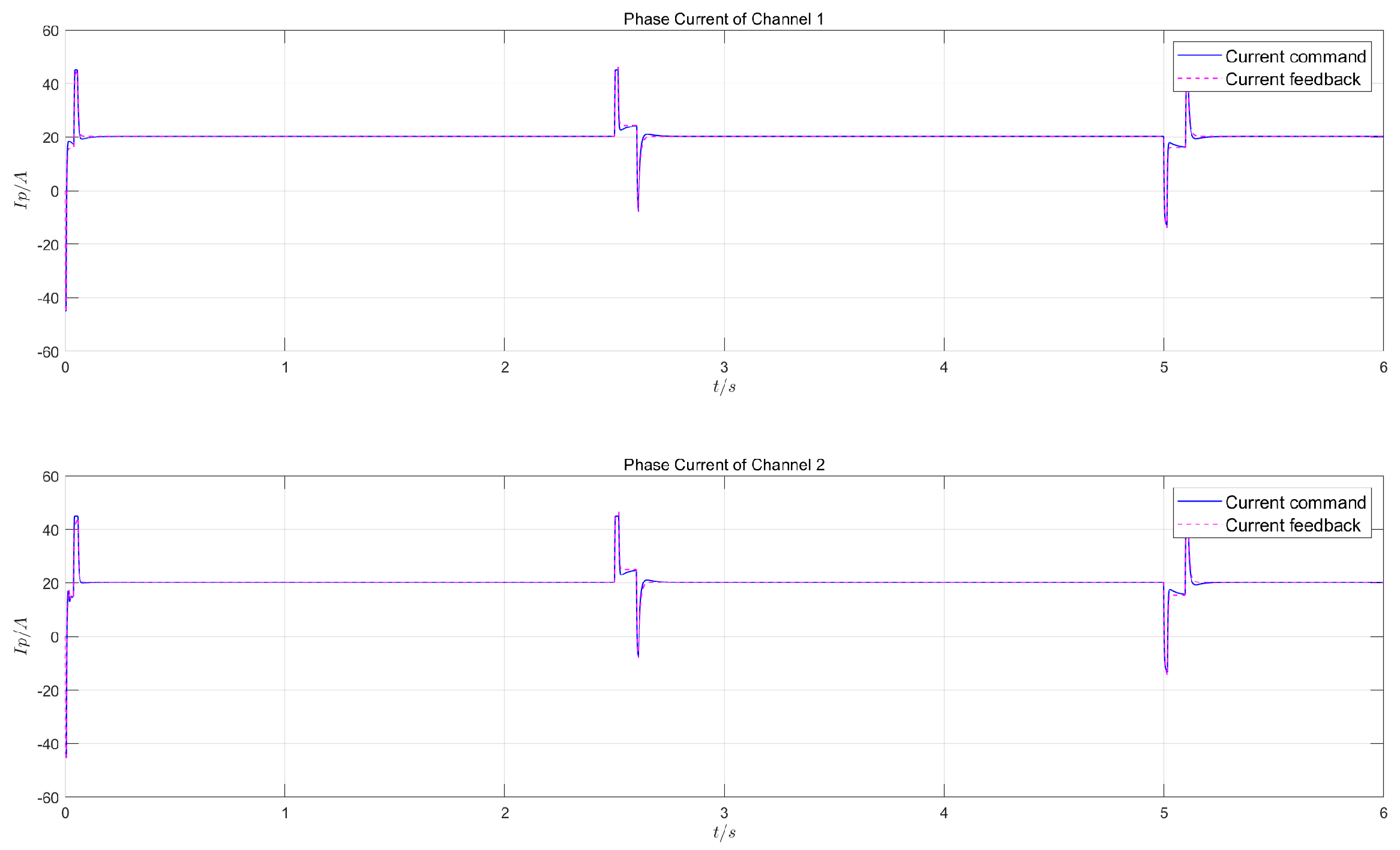

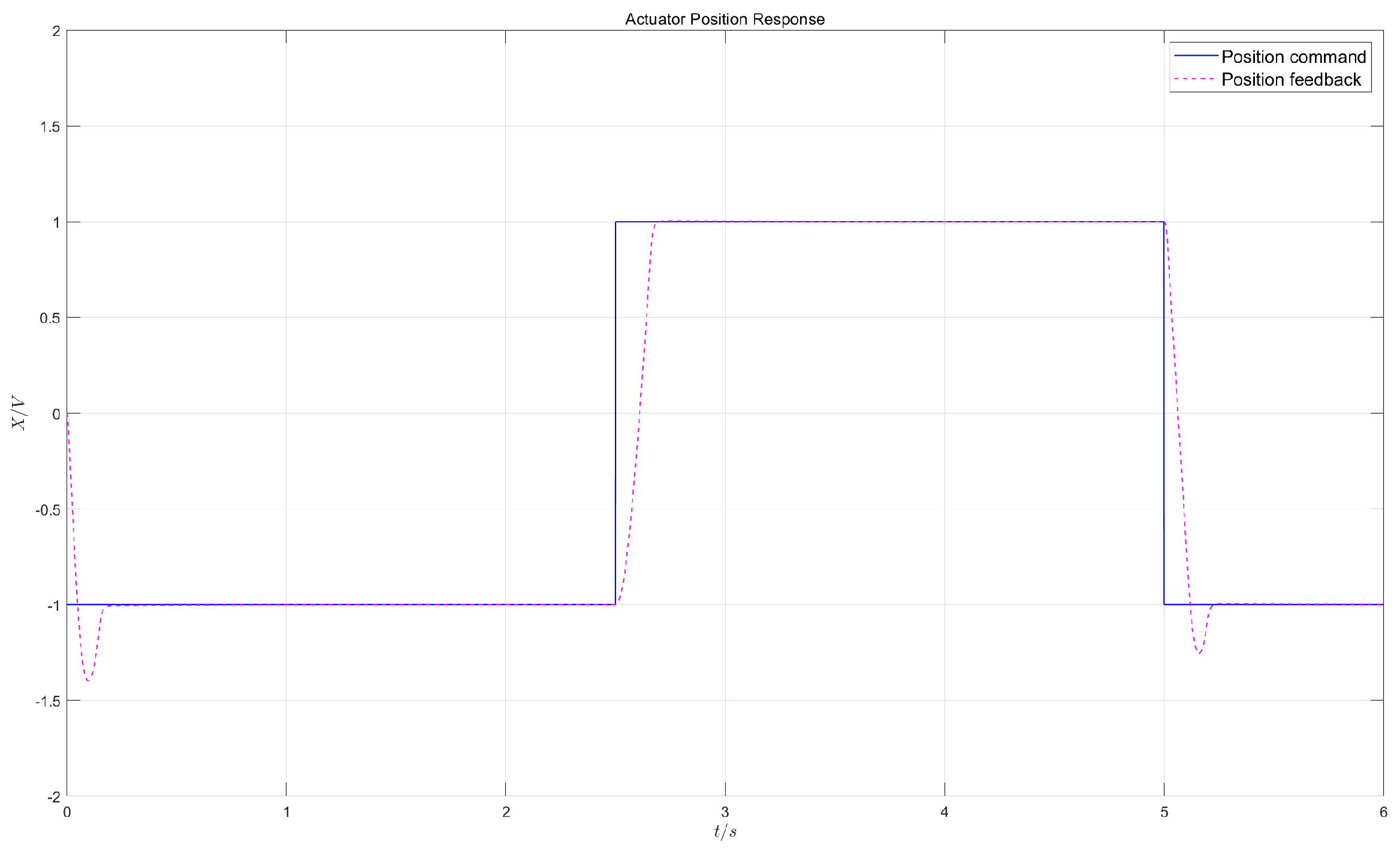

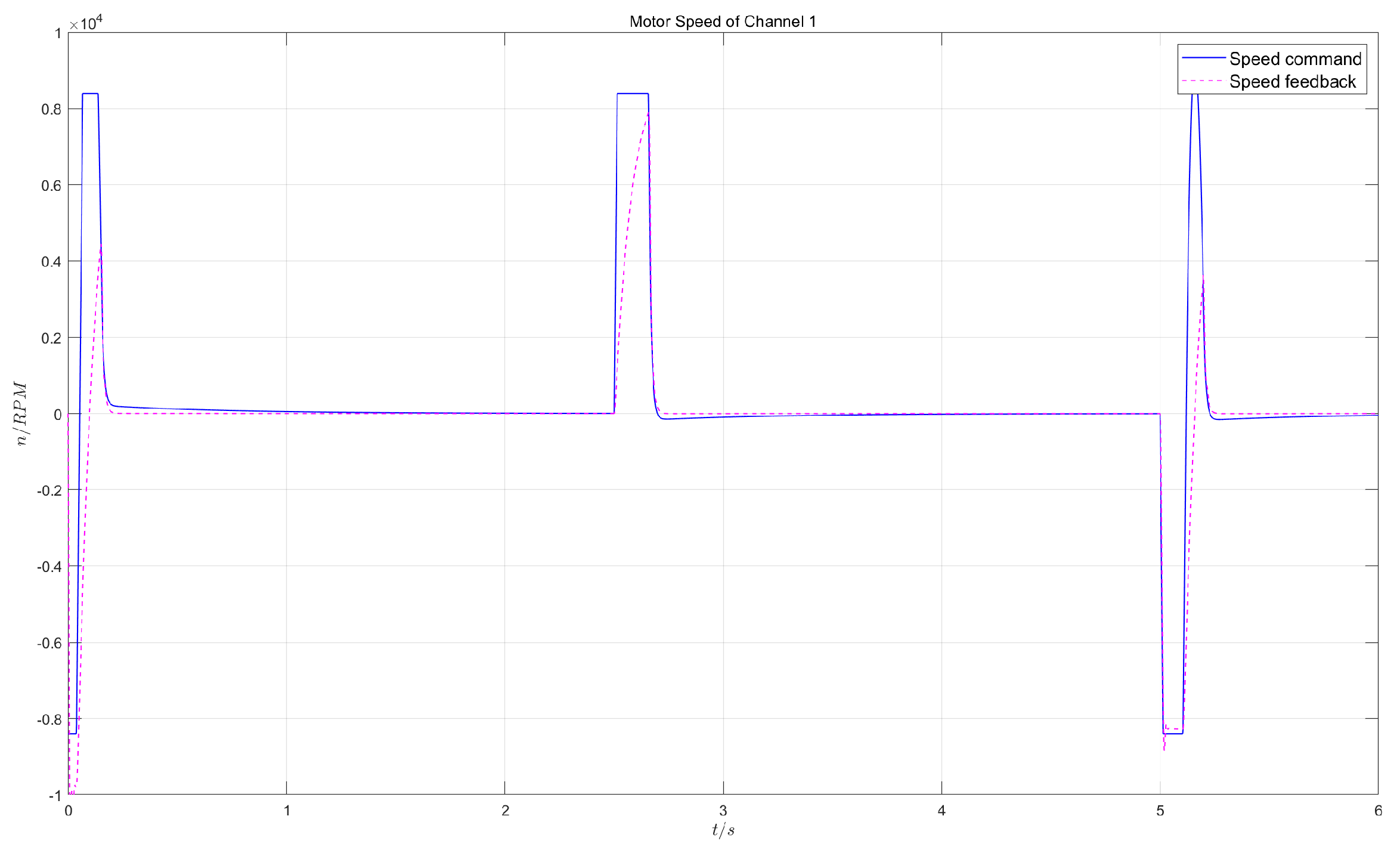

- Test 1:

- in the dual-redundancy master-master working mode, apply a constant load of 55kN and give a square wave position command of 1V/0.2Hz (1V corresponds to 7.5mm);

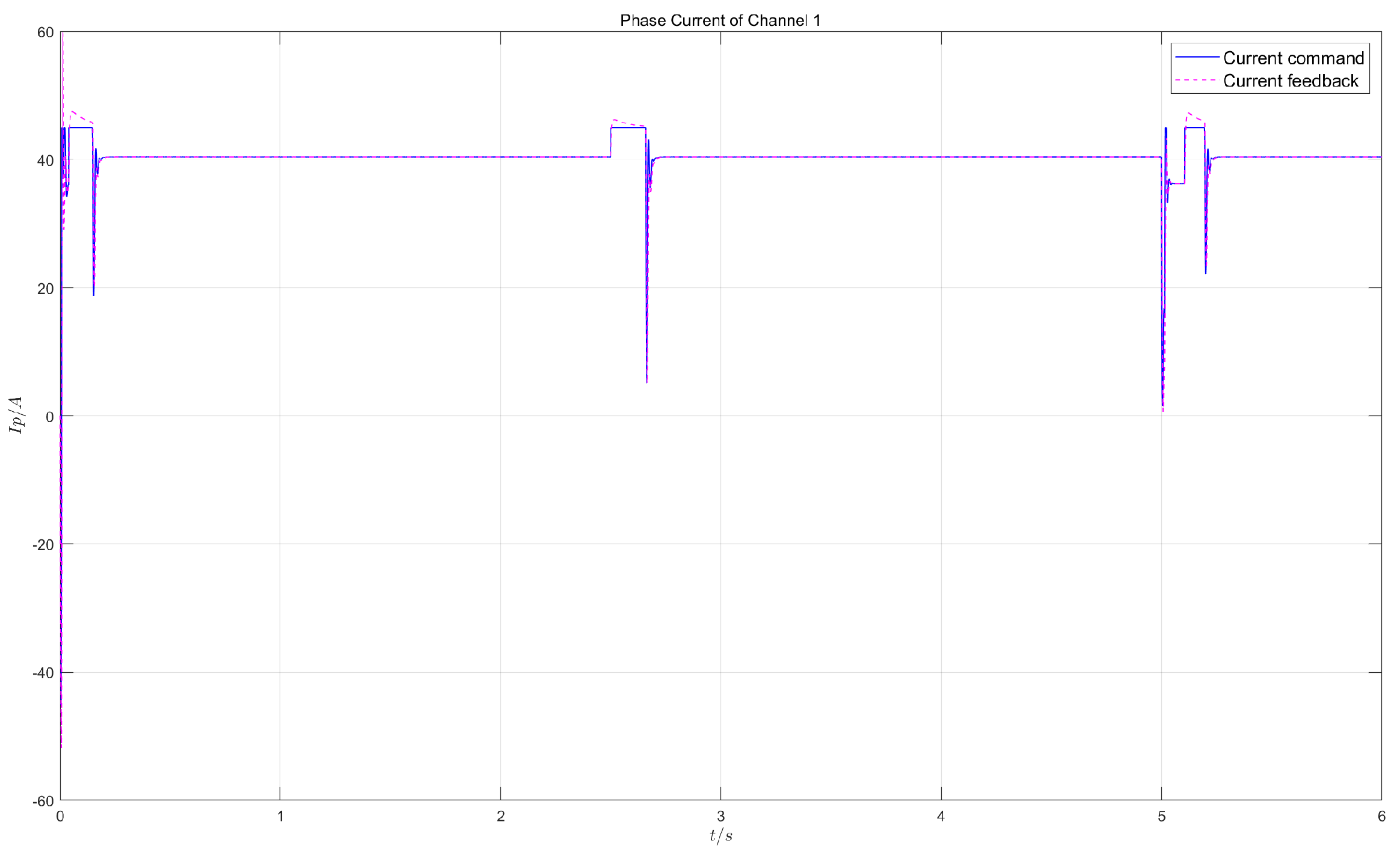

- Test 2:

- in the dual-redundancy master/standby working mode, apply a constant load of 55kN and give a square wave position command of 1V/0.2Hz (1V corresponds to 7.5mm).

5.2.2. Control Effects

5.2.3. Result Analysis

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ke, Y. , Li, Y., Cao,Y., Zhang,X. Research on model-based safety analysis of flight control system. System Engineering and Electronics 2021, 43, 3259–3265. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, X. , Luo, Y., Han, B., Qin, L., Xiao, B. Hybrid Data-Driven and Multisequence Feature Fusion Fault Diagnosis Method for Electro-Hydrostatic Actuators of Transport Airplane. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2025, 21, 3306–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J. A Review of Electric Actuation and Flight Control System for More/All Electric Aircraft. 24th International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS) 2021, 1943–1947. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, D., Bobalik, J.,Stena, D., Plag, K., Rail, K., Wal, K. F-35 Subsystems Design, Development, and Verification. Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference 2018, 365-398.

- Wiegand, C. F-35 Air Vehicle Technology Overview. Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference.

- Guan, L. , Lian, W. Review on Electro-Hydrostatic Actuation Technology of Aircraft Flight Control Actuation System. Measurement & Control Technology 2022, 41, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, M. , Yu, H., Zhao, Z., Liu, Z., Zhu, Y. Research on Control of Double-pump Electro-Hydrostatic Actuator ( EHA). Aircraft Design 2023, 43, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. , Wang, X., Wang, S., Puig, V. Switching-based adaptive fault-tolerant control for uncertain nonlinear systems against actuator and sensor faults. Journal of the Franklin Institute 2023, 360, 11462–11488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dills, P. , Dawson-Elli, A., Gruben, K., Adamczyk, P., Zinn, M. An Investigation of a Balanced Hybrid Active-Passive Actuator for Physical Human-Robot Interaction. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2021, 6, 5849–5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J. , Maré, J., Fu, Y. Modelling and simulation of flight control electromechanical actuators with special focus on model architecting, multidisciplinary effects and power flows. Chinese Journal of Aeronautics 2017, 30, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. , Yu, T., Jiao, Z., Li, Y. Research on Power Matching and Energy Optimal Control of Active Load-Sensitive Electro-Hydrostatic Actuator. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 51121–51133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, K. , Nam, D., Jin, M. Adaptive Backstepping Control of an Electrohydraulic Actuator. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2014, 19, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L. , Cui, N., He, M., Zhang, Y. Research on Electro-hydrostatic Actuator(EHA) Load Matching Method. Hydraulics Pneumatics & Seals 2022, 4, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y. , Li, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, Z., Liu, K. Observer-based robust optimal control for helicopter with uncertainties and disturbances. Asian Journal of Control 2023, 25, 3920–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, H. , Liu, W., Zhou, H. Design of servo control system based on fuzzy adaptive PI. Journal of the Hebei Academy of Sciences 2024, 41, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y. , Shi, Y., Burton, R. Modeling and Robust Discrete-Time Sliding-Mode Control Design for a Fluid Power Electrohydraulic Actuator (EHA) System. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2013, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. , Christen, A. and Begg, S., Langlois, N. Continuous–Discrete Time-Observer Design for State and Disturbance Estimation of Electro-Hydraulic Actuator Systems. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2016, 63, 4314–4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. , Zhang, Q., An, J., Liu, H., Sun, H. Cross-coupling control method of the two-axis linear motor based on second-order terminal sliding mode. J Mech Sci Technol 2022, 7, 1485–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D. , Liu, H., Su, Y. Integral robust collaborative control of hydraulic servo system based on cross-coupling. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2025, 53, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, J. , Cao, X., Zhang, Y., Li, Y. Cross-coupled fuzzy PID control combined with full decoupling compensation method for double cylinder servo control system. J Mech Sci Technol 2018, 32, 2261–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H. , Teng, Y. Force equalization control for dual-redundancy electrol-hydrostatic actuator. Journal of Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics 2017, 43, 270–276. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F. , Liu, H., Zhang, P., Ouyang, X. Xu, L., Ge, Y., Yao, Y., Yang, H. High-Precision Control Solution for Asymmetrical Electro-Hydrostatic Actuators Based on the Three-Port Pump and Disturbance Observers. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2023, 28, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H. , Gao, B., Li, J. Sliding Mode-PID Control for Aircraft Electro-Hydrostatic Actuator. Civil Aircraft Design & Research 2023, 131, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).