Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterisation of Tailings from the HPAL Process

2.2. Design of Batch Bioextraction Experiments

2.3. Determination of Metal Extraction and Selectivity

3. Results

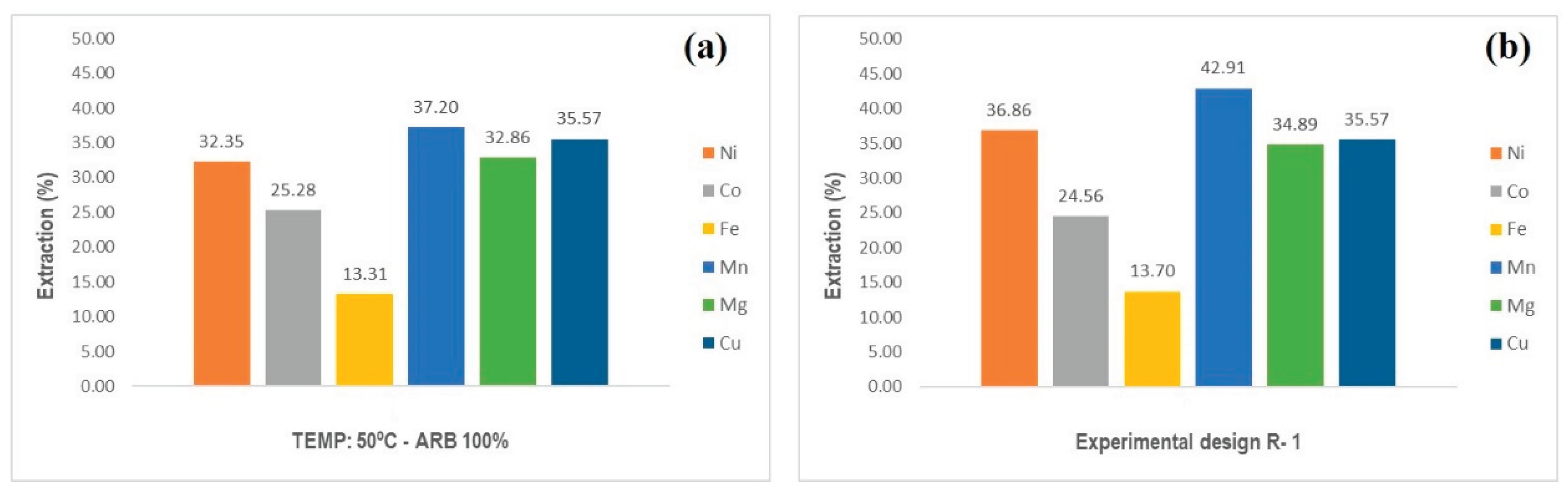

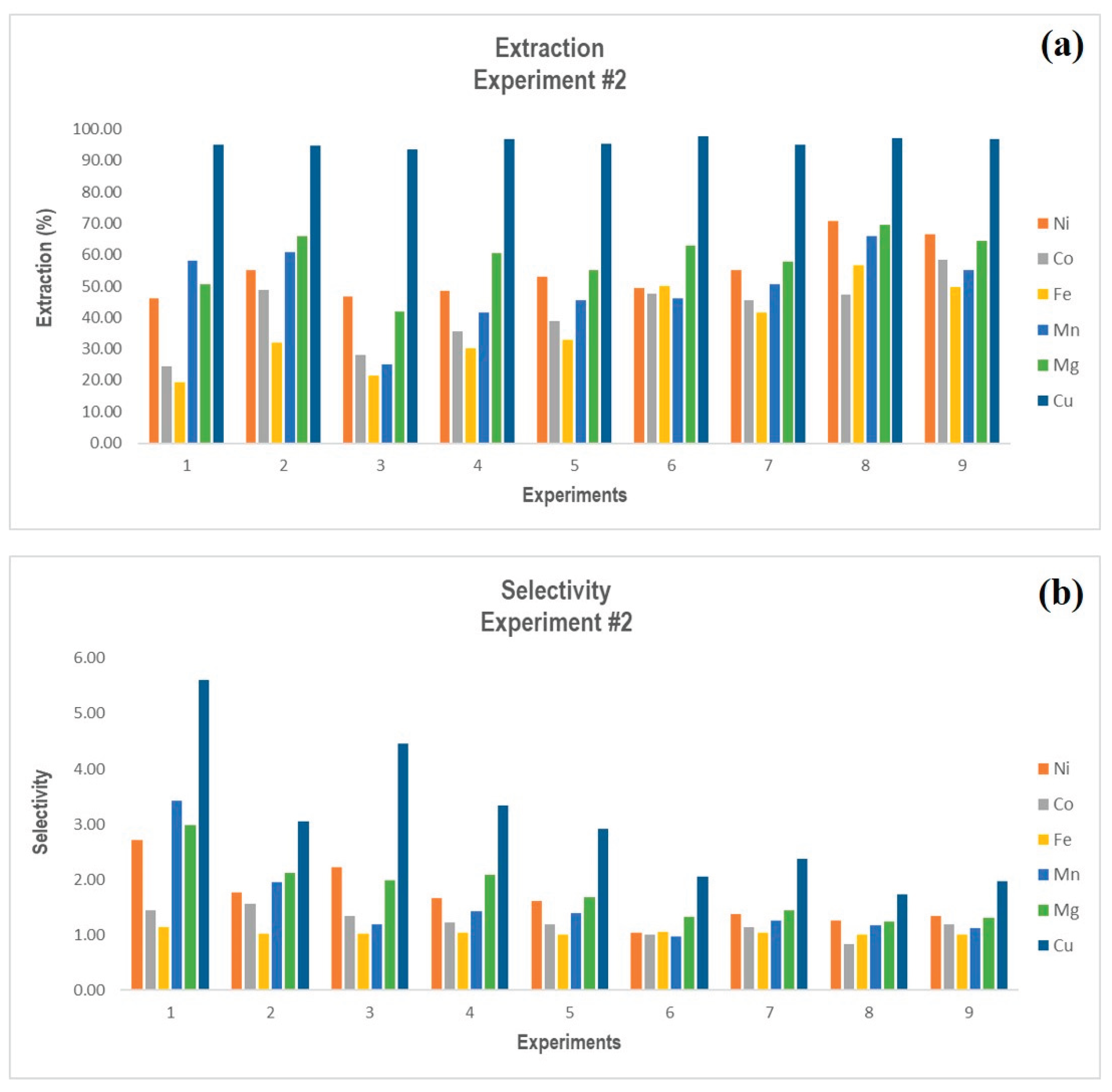

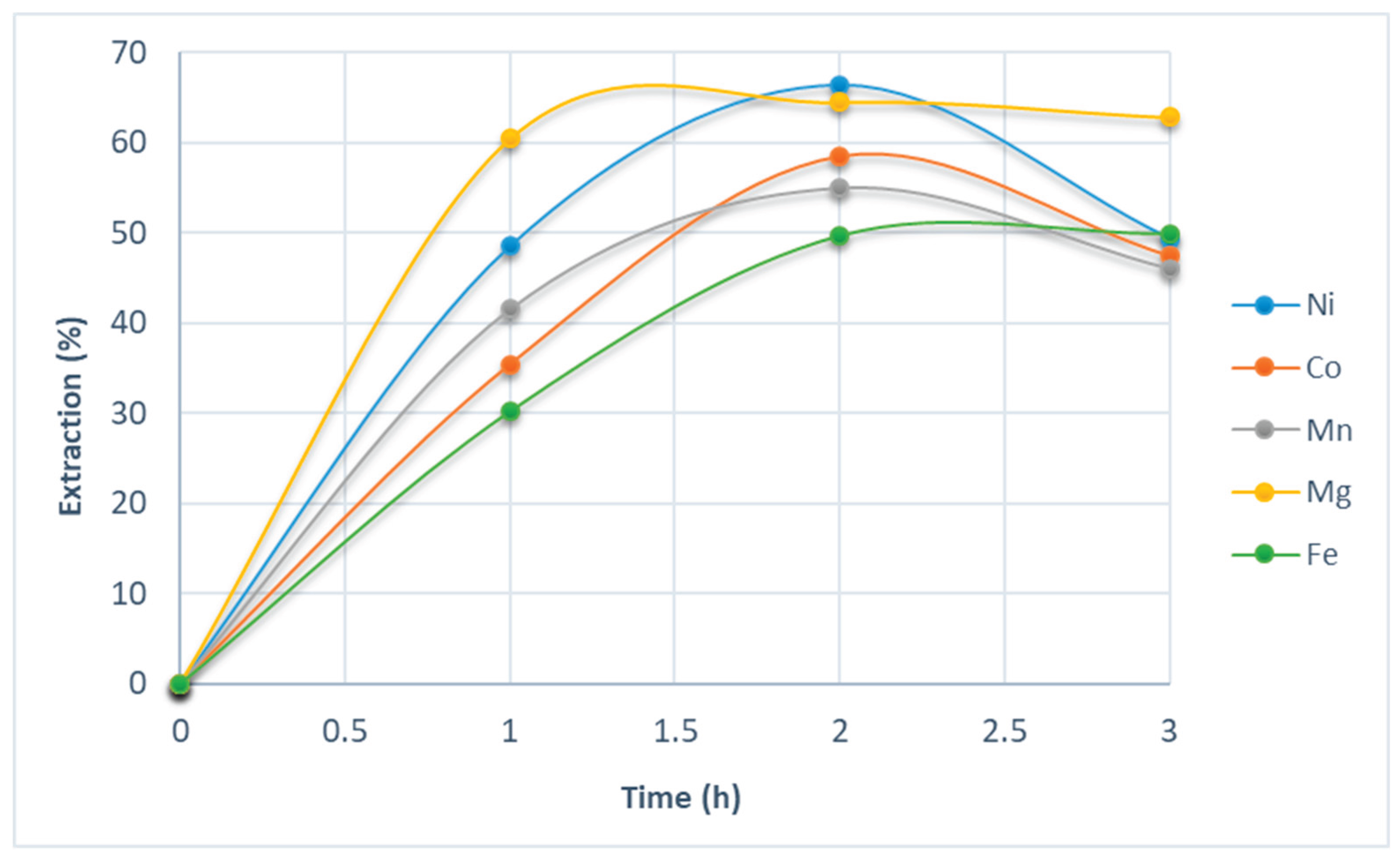

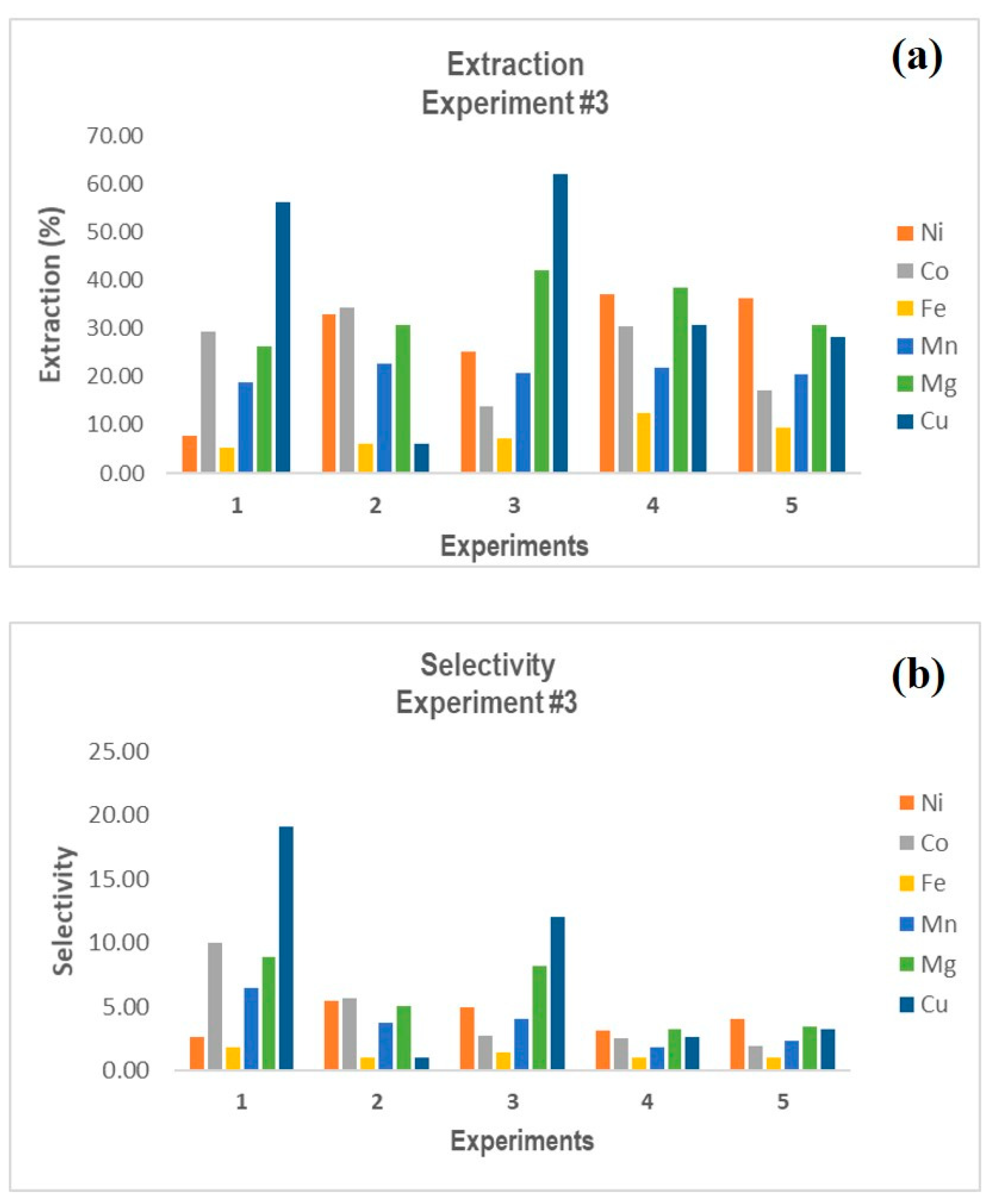

3.1. Bioextraction of Metal Species Using BRA

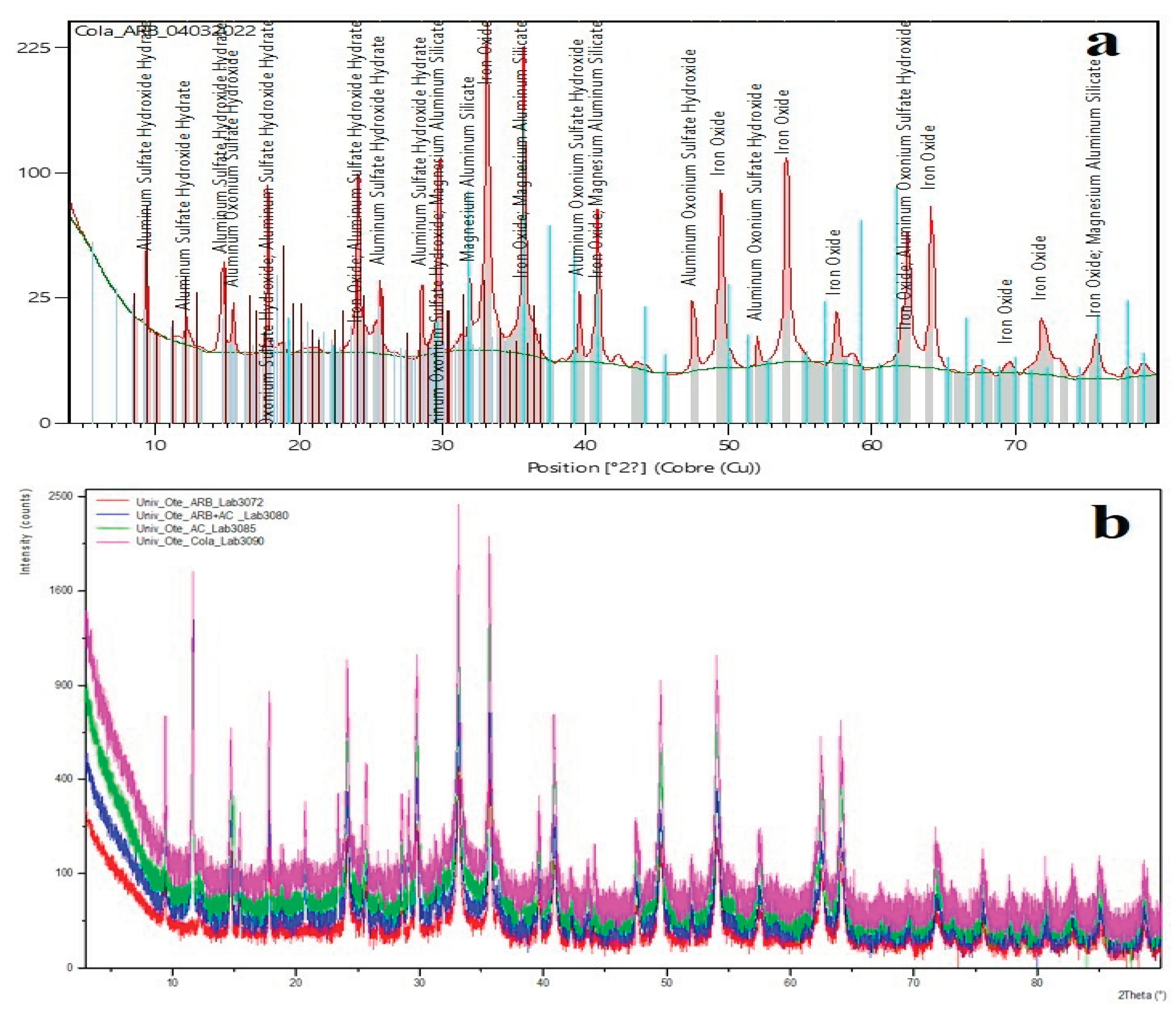

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Results of Tailings After Leaching with Various Leaching Agents

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bernadelli, C. , Plaza Cazón, J. d. C., Urbieta, M. S., & Donati, E. R. Biominería: los microorganismos en la extracción y remediación de metales. Industria & Química, 2017, 9, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Maestigues-Palanco, R. A. , Mas-Diego, S. M., & Pérez-García, L. Bioextracción de especies metálicas de colas filtradas de la industria metalúrgica con agente reductor biológico. Tecnología Química, 2003, 43, 638–659. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Sanabria, G. , Sánchez López, M. I., Ramírez Pérez, M. C., & Pons Herrera, J. A. Solubilización de níquel y cobalto presente en un escombro laterítico mediante el empleo de Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans Revista CENIC Ciencias Biológicas, 2022, 53, 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Breffe, Y. (2017). Evaluación de las principales características físico – químicas del pasivo ambiental “colas viejas” para su posible uso industrial (Publication Number 389) [Trabajo de Diploma, Universidad de Moa "Dr. Antonio Núñez Jiménez" ]. Repositorio Nínive.

- Cavinda, A. P. V. (2019). Procedimiento para la evaluación de riesgos geo-ambientales en los Pasivos Ambientales Mineros [Trabajo de diplomaPara Optar Por El TítuloDe Ingeniero Geólogo, Universidad de Moa "Dr. Antonio Núñez Jiménez"]. Repositorio Nínive.

- Akhtar, K.; Akhtar, W.; Khalid, A. Removal and recovery of uranium from aqueous solutions by Trichoderma harzianum. Water Research 2007, 41, 1366–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsezos, M. , Georgousis, Z. , Remoudaki, E. Mechanism of aluminium interference on uranium biosorption by Rhizopus arrhizus. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1997, 55, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaro Aguilar, J. L. , & Rodríguez Fernández, S. Y. (2024). Influencia de la concentración de Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans y Yarrowia lipolytica para remoción de cromo contenido en lodo residual mediante biolixiviación [Tesis de Ingeniería Química, Universidad Nacional de Trujillo]. Fondo Editorial.

- Bosecker, K. (1987). Leaching of lateritic nickel ores with heterotrophic microorganisms Fundamental and applied biohydrometallurgy. Proceedings of the sixth international symposium on biohydrometallurgy Vancouver, BC, Canada, -24, 1985. 21 August.

- Bosecker, K. Bioleaching: metal solubilization by microorganisms. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 1997, 20, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruguera-Amaran, N. , Rodríguez-Gamboa, J. , Coto-Pérez, O., Capote-Flores, N., & Bassas-Noa, P. R. Estudio de la lixiviación de la serpentinita niquelífera con ácidos orgánicos. Minería y Geología, 2018, 16, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, A. D. , Sariol, L. R., Ramos, E. D., Coto, O., Gómez, A. C., Pérez, J. A. A., & Padilla, M. (2015).

- Pacsi Achahui, M. , & Cañari Diaz, J. J. (2022). Método de biolixiviación mediante la aplicación de hongos filamentosos en diversas fuentes de contaminación: revisión sistemática [Tesis para obtener el título profesional de Ingeniero Ambiental, Universidad César Vallejo]. Repositorio Institucional Universidad César Vallejo. Revista de Investigación en Ingeniería.

- Castillo, G. , & Villafañe, C. (2003). Recuperación de Ni y Co de la laterita ferruginosa del Estado Cojedes a través de la Biolixiviación con cultivos de Aspergillus niger (Publication Number 2) [Trabajo especial de grado para optar el Titulo de Ingeniero Metalúrgico, Universidad Central de Venezuela]. Saber UCV.

- Esquivel-Figueredo, R. d. l. C. , & Mas-Diego, S. M. Síntesis biológica de nanopartículas de plata: revisión del uso potencial de la especie Trichoderma Tecnología Química 2021, 33, 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, T. P. , Kulanthaivel, S. , Kamil, D., Borah, J. L., Prabhakaran, N., & Srinivasa, N. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Trichoderma species. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology 2013, 7, 543–547. [Google Scholar]

- Diko, C. S. , Qu, Y. , Henglin, Z., Li, Z., Nahyoon, N. A., & Fan, S. J. A. J. o. C. Biosynthesis and characterization of lead selenide semiconductor nanoparticles (PbSe NPs) and its antioxidant and photocatalytic activity. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2020, 13, 8411–8423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenspiel, O. (1998). Chemical reaction engineering (Vol. Third Edition ). John wiley & sons.

- Smith, J. M. , Van Ness, H. C., Abbott, M. M., & García, C. R. (2007). Introducción a la termodinámica en ingeniería química.

- Albright, L. (2008). Albright's chemical engineering handbook (E. b. L. F. Albright, W. L. Purdue University, & U. Indiana, Eds.). CRC Press.

- Molina Matamala, L. I. (2018). Identificación y análisis de agentes lixiviantes no convencionales para la recuperación de elementos de valor desde minerales, concentrados y escorias de fundición [Informe de Memoria de Título pata optar al Título de Ingeniero Civil Metalúrgico, UNIVERSIDAD DE CONCEPCIÓN]. Repositorio UDEC.

- Medina, M. P. , Cabrera, E. M., Ortega, G. G., Borges, S. A., del Campo Lafita, A. S., & Hernández, J. F. J. T. Q. Lixiviación de colas del proceso caron con lixiviante orgánico: ácido acético y ácido piroleñoso. Tecnología Química 2008, 28, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, M. P. , Guasch, N. S., Roger, J. M., Borges, S. A., & Hernández, J. F. (2009). Lixiviación a escala de banco de las colas de la tecnología carbonato amoniacal con ácido piroleñoso de bagazo de caña. Tecnología Química, XXIX, 187-194.

- Díaz Bello, S. C. (2016). Modelamiento cinético del procesamiento de minerales lateríticos de níquel por vía pirometalúrgica (Publication Number 60) [Trabajo de grado - Doctorado, Universidad Nacional de Colmbia. Sede Medellín]. Repositorio Institucional UNAL.

- Hernández Tirado, R. (2018). Estudio pirometalúrgico del Pasivo Ambiental Colas viejas, de la empresa Comandante Pedro Sotto Alba, de Moa [Tesis presentada en opción al título del Ingeniero en Metalurgia yMateriales, Universidad de Moa "Dr. Antonio Núñez Jiménez" ]. Repositorio Nínive.

- Bruckard, W. J. , Calle, C. M., Davidson, R. H., Glenn, A. M., Jahanshahi, S., Somerville, M. A.,... Zhang, L. Smelting of bauxite residue to form a soluble sodium aluminium silicate phase to recover alumina and soda. Sage Journals 2010, 119, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortíz Bárcenas, J. , & López Gómez, F. A. (2024). Memorias de las investigaciones realizadas para el procesamiento siderúrgico de minerales de hierro cubanos. Editorial CENIC.

- Suarez Leyva, A. (2022). Obtención de un producto metalizado base hierro, a partir de colas del proceso CARON [Trabajo de Diploma en Opción al título de Ingeniero en Metalúrgia y Materiales, Universidad de Moa "Dr. Antonio Núñez Jiménez" ]. Repositorio Nínive.

- Pons Herrera, J. A. , Ramírez Pérez, M. C., & Ortiz Bárcenas, J. (2021). Uso sustentable de los pasivos ambientales minero metalúrgicos sólidos, generados por la industria del Níquel en Moa, Cuba. Revista Angolana de Geociências, 2.

- CEDINIQ. (2022a). Determinación de cobre, zinc, magnesio, níquel, cobalto, hierro y manganeso. Método de Espectrofotometría de Absorción Atómica. In. La Habana, Cuba: Miniestrio de Ciencia, Tecnología y Medio Ambiente de Cuba.

- CEDINIQ. (2022b). Determinación hierro total. Método Volumétrico. (UPL-PT-V-02). In. La Habana, Cuba: Miniestrio de Ciencia, Tecnología y Medio Ambiente de Cuba.

| Batch experimentsLeaching agents | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological reducing agent (BRA) |

Bioextraction with citric acid | ||||||||

| Experimental design R-1 (BRA) |

Experimental design R-2 (BRA +CA) |

Experimental design R-3 (Control Experiment) |

|||||||

| Exp. | T(ºC) | R(L/S) | Exp. | T(ºC) | R(L/S) | t (h) | Exp. | T(ºC) | Conct. CA (M) |

| 1 | 60 | 8 | 1 | 30 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 0,5 |

| 2 | 60 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 60 | 0,5 | |||

| 3 | 30 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 30 | 1 | |||

| 4 | 60 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 60 | 1 | |||

| 5 | 30 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 45 | 0,75 | |||

| 6 | 60 | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| 7 | 30 | 8 | 3 | ||||||

| 8 | 60 | 8 | 3 | ||||||

| 9 × 3 | 45 | 5 | 2 | ||||||

| Chemical composition of residual tailings (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni | Co | Fe | Mn | Mg | Cu |

| 0,080 | 0,011 | 43,68 | 0,079 | 0,133 | 0,014 |

| Item | A: Temp. | B:Relac. LS | C:time | AB | AC | BC | Total error | Total (corr.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of squares | Extraction | 34.694 | 14.960 | 79.50 | 3.5 | 3.67 | 66.24 | 50.74 | 253.43 |

| Selectivity | 0.5196 | 0.0291 | 1.094 | 0.1 | 0.11 | 0.062 | 0.123 | 2.060 | |

| Gl | Extraction | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 10 |

| Selectivity | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 10 | |

| Mean square | Extraction | 34.694 | 14.960 | 79.50 | 3.5 | 3.67 | 66.24 | 25.05 | |

| Selectivity | 0.5196 | 0.0291 | 1.094 | 0.1 | 0.11 | 0.062 | 0.031 | ||

| F-Ratio | Extraction | 93.01 | 40.10 | 213.1 | 9.4 | 9.84 | 177.5 | ||

| Selectivity | 16.94 | 0.95 | 35.69 | 3.9 | 3.58 | 2.03 | |||

| Probable Value | Extraction | 0.0106 | 0.0240 | 0.0047 | 0.091 | 0.088 | 0.014 | ||

| Selectivity | 0.0147 | 0.3847 | 0.003 | 0.1 | 0.13 | 0.227 | |||

| Nickel Extraction | Nickel selectivity | ||||||||

| R2 = 96.485 % R2 (adjusted for l.g.) = 94.5677percent Std. error = 0.0884915 Durbin-Watson statistic = 1.66755 (P=0.3763) Residual autocorrelation of Lag 1 = -0.202252 |

R2= 94.0451 % R2 (adjusted by l.g.) = 85.1127 % Std. error of est. = 0.175128 Durbin-Watson statistic = 1.06713 (P=0.0026) Residual autocorrelation of Lag 1 = 0.5867 |

||||||||

| Item | A: Temp. | B:Relac. LS | C:time | AB | AC | BC | Total error | Total (corr.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of squares | Extraction | 216.21 | 1.2090 | 222.9 | 71.2 | 56.44 | 31.72 | 19.59 | 619.32 |

| Selectivity | 0.0111 | 0.0276 | 0.187 | 0.003 | 0.011 | 0.021 | 0.171 | 0.4405 | |

| Gl | Extraction | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 10 |

| Selectivity | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 10 | |

| Mean square | Extraction | 216.21 | 1.2090 | 222.9 | 71.2 | 56.44 | 31.72 | 4.89 | |

| Selectivity | 0.0111 | 0.0276 | 0.187 | 0.003 | 0.011 | 0.021 | 0.085 | ||

| F-Ratio | Extraction | 44.15 | 0.25 | 45.52 | 14.5 | 11.5 | 6.48 | ||

| Selectivity | 3.14 | 7.80 | 53.07 | 0.9 | 3.14 | 6.17 | |||

| Probable Value | Extraction | 0.0027 | 0.6454 | 0.0025 | 0.019 | 0.0274 | 0.0636 | ||

| Selectivity | 0.2186 | 0.1079 | 0.0183 | 0.437 | 0.218 | 0.1310 | |||

| Cobalt Extraction | Cobalt Selectivity | ||||||||

| R2 = 96.8369 percent R2 (g.l. adjusted) = 92.09 percent Standard error of est. = 2.21303 Durbin-Watson statistic = 1.84866 (P=0.4549) Residual autocorrelation of Lag 1 = 0.00306817 |

R2 = 59.6513 percent R2 (g.l. adjusted) = 0.0 percent Std. error = 0.0595007 Durbin-Watson statistic = 0.408118 (P=0.0043) Residual autocorrelation of Lag 1 = 0.634658 |

||||||||

| Code Ref. | Compound Name | Chemical Formula | Mineral Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01-089-0596 | Iron oxide (III) | Fe2O3 | Hematite (synthetic) |

| 00-016-0409 | Aluminium oxonium hydroxyl sulphate | (H3O)Al3(SO4)2(OH)6 | Aluminium Jarosite (similar phase) |

| 00-024-0007 | Hydroxylated aluminium sulphate hydrate | Al4(SO4)(OH)10·5H2O | Basaluminite |

| 00-035-0964 | Magnesium aluminium hydroxide hydrate | Mg4Al2(OH)14·3H2O | Hydrotalcite (similar phase) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).