Article Objective

The aim of this article is to analyse the impact of façade structure on the harmonisation of buildings with the natural landscape. It presents various architectural approaches, materials, and technologies that enable integration of buildings with their surroundings while minimising visual and ecological footprints. The article emphasises the importance of selecting appropriate textures, colours, and façade forms in the context of landscape protection and spatial aesthetics.

Research Questions

How does the structure of a façade influence a building’s integration with the natural landscape?

Which façade materials and technologies best harmonise with the natural environment?

Can the structure and colour of a façade reduce the visual intrusion of a building on the landscape?

What design strategies support a sustainable relationship between architecture and nature?

How do local geographical and climatic conditions influence the selection of façade structure?

Research Methodology

The research process included the analysis of relevant documentation and literature, followed by field studies of residential buildings constructed at the turn of the 21st century.

Research Techniques Employed:

Source literature review

Comparative analysis of completed architectural projects

Field inspection – original photographic documentation by the authors

Based on developed selection criteria, the following buildings were chosen for case study:

Rudy: House in Rudy, designed by “Toprojekt” – Marek Wawrzyniak, Karol Wawrzyniak, Izabela Groborz-Musik (2017)

Bielsko-Biała: Shingle House, designed by “Iterurban” – Weronika Juszczyk, Łukasz Piankowski (2013)

Żywiec Beskids: Modern Barn, designed by “Architekt Kozieł” – Maciej Kozieł and Edyta Dłutko (2020)

Borówiec near Poznań: House made of natural stone, designed by “Milwicz Architekci” – Natalia Milwicz (2021)

Selection Criteria:

Objective architectural merit – Awards granted by professional bodies; publications in recognised architectural journals

Contextual integration – The façade should harmonise with the natural landscape through appropriate use of materials, colour, and texture

Use of local materials – Selection of regionally available resources (e.g., timber, stone, brick) enhances integration with surroundings and reduces the carbon footprint

Environmental impact – The façade’s structure should minimise disruption to the natural environment, e.g., through green walls, natural ventilation, or pollution-absorbing façades

Climate adaptability – Façade structure should reflect local climatic conditions such as humidity, sunlight exposure, strong winds, or snowfall

Topographical integration – The façade should emphasise or subtly respond to landforms, e.g., by using terraces, sloped walls, or organic shapes

Aesthetic and cultural value – References to traditional regional architecture help preserve local identity and embed the building within the cultural landscape

State of Research

In the academic literature on sustainable development, one notable work is

Understanding Sustainable Architecture by Terry Williamson, Antony Radford, and Helen Bennetts. This publication offers a critical analysis of the assumptions, beliefs, and objectives related to sustainable architecture. Rather than offering prescriptive “how-to” guidance, the authors develop the theoretical and philosophical foundations of sustainable design, aiming to establish it as a coherent and ethically justified practice, rather than merely a collection of technical solutions [

9].

Another significant publication is

Aesthetics of Sustainable Architecture by Sang Lee, which aims to explore and expand the debate surrounding the aesthetics of sustainable architecture. It emphasises that sustainability in architecture is not solely a matter of technology or environmental concerns but is also intrinsically linked to aesthetics, culture, and design ethics [

8]. The book is a compilation of articles and essays by renowned architects and theorists from around the world, including Kenneth Frampton, Kengo Kuma, Ralph L. Knowles, and Nezar AlSayyad. It is organised into chapters addressing various aspects of the topic.

A foundational text in this field is also Kenneth Frampton’s essay Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance, a classic work on the relationship between architecture, landscape, culture, and topography. It provides a vital framework for interpreting façades in the context of regionalism.

Also of note is Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture by Christian Norberg-Schulz, in which the author explores the perception of place and landscape, showing how the materials and structure of buildings influence our experience of the environment.

Juhani Pallasmaa’s monograph The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses presents a phenomenological approach to texture, structure, light, and the sensory perception of façades in relation to space.

Among Polish publications, a valuable contribution is Qualitative Research of the Built Environment (Polish: Badania jakościowe środowiska zbudowanego), edited by Elżbieta Niezabitowska, which collects academic articles on the quality of the built environment.

Another important source is Polish Architecture of the 20th Century, edited by Jerzy Malinowski, offering an overview of buildings from the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Likewise, Contemporary Architecture in Poland by Tomasz M. Czerwiński (published by Arkady) is a more accessible publication featuring examples and photographs of contemporary façades.

Also worth mentioning is the book Architecture and Urban Planning in Poland 1989–2014, edited by Jerzy Bogusławski and Anna Kicińska, which analyses contemporary architectural projects in the context of urban and landscape transformations. Another important work is Modern Architecture in Poland by Andrzej Basista, which examines the impact of architectural forms on space, including both urban and natural landscapes.

In the context of contemporary Polish architecture and its relationship with the cultural landscape, relevant articles can also be found in journals such as Architektura & Biznes and Architektura Murator. In international literature, significant contributions on this subject appear in journals such as Sustainability, Architectural Science Review, and Buildings.

House in Rudy, Poland

Location and Context

The house is located in the village of Rudy (Silesian Voivodeship), on a plot surrounded by forest and dispersed rural development. The site features a natural woodland landscape dominated by pine trees and low-rise residential and agricultural buildings. The building’s walls were constructed using hand-sorted waste bricks sourced from local brickyards [

10], which represents an important ecological aspect of the project—namely, the use of local materials. A variation of the Flemish bond was employed, where pairs of bricks placed vertically side by side were alternately pushed out or recessed in relation to the wall surface. This simple technique greatly enriched the façade’s play of light and shadow. By entirely removing the same brick pair, a perforated wall was created to conceal window openings that might otherwise disrupt the clarity of the façade’s structure [

11].

Photo 1, Photo 2. Photographs by Justyna Juroszek

Designers

The project was developed by the studio Toprojekt, renowned for its minimalist and contextually grounded designs in the Silesian region. The design team included:

Marek Wawrzyniak

Karol Wawrzyniak

Izabela Groborz-Musik

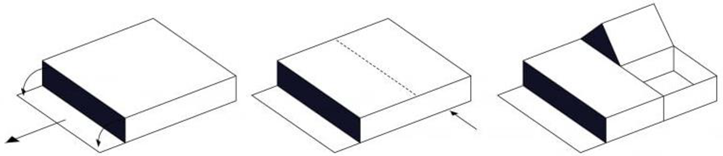

Form

The building has a compact, cuboid form with a gable roof, referencing the archetype of a traditional rural house while maintaining a contemporary simplicity and reduction of form. The architects began with a classic square volume and introduced three simple modifications. The western wall recedes towards the garden, forming a terrace accessible from the living room, dining area, and master bedroom. The southeastern quarter (facing the neighbourhood) was “hollowed out”, creating a gated entrance courtyard enclosed by brick walls. Meanwhile, the northeastern part was extended vertically to accommodate an attic-level bedroom area, capped with a gabled roof and finished with ceramic tiles. The flat roof section was covered with greenery.

Façade and Materials

The main façade material is clinker brick in a warm, reddish tone, harmonising beautifully with the natural earthy colours and the surrounding forest. The bricks are laid in a regular pattern without unnecessary ornamentation, reinforcing the building’s minimalist and modern character. The roof is clad in flat ceramic tiles in a colour matching the façade, resulting in a cohesive and harmonious appearance. Large glazed sections facing the garden open the interiors to the landscape, allowing natural light to enter and visually breaking up the building’s mass.

Impact of the Façade on the Natural Landscape

The building’s colour palette and materials were carefully selected—the use of reddish clinker brick allows the house to blend into the forested environment and relate to the tones of Silesian soil and the region’s traditional brick architecture. The structure and texture of the façade, composed of naturally finished bricks, create a calm and subdued surface that complements the surrounding trees and natural landscape elements. The architectural form is a minimalist volume with a gabled roof, referencing local tradition while underscoring a contemporary design language through the absence of decorative detail.

Theoretical Interpretation

The project aligns with the principles of

critical regionalism [

7], where architecture merges modernity with a sense of place, avoiding historicism or stylisation. The House in Rudy expresses the

genius loci [

3] through its use of local materials (brick) and archetypal form, fostering a sense of landscape identity. The brick’s structure and its sensory qualities (touch, colour, texture) foster a physical and emotional user experience [

12], integrating the building into the landscape without dominance or harsh contrast.

The House in Rudy exemplifies how façade structure and material selection can reinforce the relationship between architecture and nature. It combines minimalist form with local character, allowing the building to blend into the landscape in a calm and balanced way. This project demonstrates how contemporary architecture can enhance a place’s identity while employing a modern design language.

Shingle House in Bielsko-Biała (Poland)

Location and context

The building is located in Bielsko-Biała, on a plot in the vicinity of a forest and scattered single-family housing. The area has a strongly emphasized mountain landscape, with views of the Beskid Mountains and rich vegetation, which determines the need for sensitive integration of architecture into the surroundings. It was the terrain of the plot and the panorama of the nearby mountain range that became a direct inspiration for the location, formation of the body and the arrangement of individual functions.

Photo 3, Photo 4. Photographs by Justyna Juroszek

Designers

Iterurban Studio, composed of:

Weronika Juszczyk

Łukasz Piankowski

The architects are known for their minimalist, contextual designs that are deeply embedded in the cultural landscape of the region.

Form and layout

The building has a simple, compact form with a gable roof, evoking the archetype of a Beskid country house [

13,

14]. The body fits into the slope of the terrain, minimizing interference with the landscape.

Facade and materials

The façade of the building is entirely covered with wooden shingles [

15,

16], which also includes the roof slopes, which creates a coherent and monolithic coating. The use of shingles refers to the tradition of highlander construction in the Podbeskidzie region, but in a modern, minimalist form devoid of decorative details. Large glazing in the side facades opens the interior to the surrounding landscape, while maintaining privacy on the entrance side.

Facade and materials

The façade of the building is entirely covered with wooden shingles [

15,

16], which also includes the roof slopes, which creates a coherent and monolithic coating. The use of shingles refers to the tradition of highlander construction in the Podbeskidzie region, but in a modern, minimalist form devoid of decorative details. Large glazing in the side facades opens the interior to the surrounding landscape, while maintaining privacy on the entrance side.

Colors and texture

The natural wood of the shingle has patinated over time, changing from warm brown to shades of gray, which further harmonizes the building with the natural surroundings of the forest and mountains. [

18]

The impact of façades on the natural landscape

The use of wooden shingles on the entire surface of the building – both on the walls and on the roof – allows to achieve the effect of a "building-sculpture" [

19] harmoniously blended into the landscape, devoid of clear structural divisions. The natural colour of wood, changing with the passage of time, strengthens its organic character, inscribing the building in the rhythm of natural transformations. The minimalist, archetypal form of the body gives the building a discreet presence in the surroundings, not competing with the landscape, but complementing it.

Theoretical interpretation

The project represents critical regionalism [

7], where local material and formal traditions are reinterpreted in the spirit of contemporary minimalism. The house from Shingle emphasizes the spirit of the place through the choice of material, form and proportions [

6], becoming an integral part of the Beskid landscape. The texture of wood, its smell, variability of colours and touch create a multi-sensory experience [

12] that strengthens the relationship between the inhabitants and their surroundings.

The Shingle House in Bielsko-Biała is an excellent example of architecture in which the structure of the façade fully integrates the building with the natural landscape. Thanks to the use of traditional wooden shingle material in a modern, minimalist form, the project combines respect for local tradition with current architectural trends. This harmonious composition allows not only to subtly fit into the surroundings, but also to create a new aesthetic quality, where the simplicity of form and naturalness of the material harmonize with the rhythm of nature. The House of Shingles shows that contemporary architecture can effectively build a bridge between heritage and innovation, creating a space that is functional, beautiful and expressive.

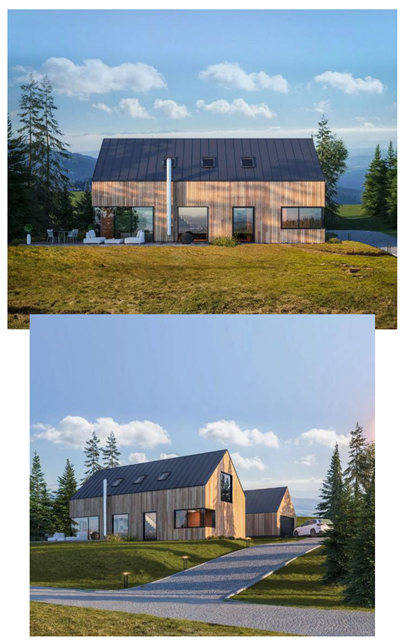

Modern Barn in Beskid Żywiecki (Poland)

Location and context

The building is located in the Beskid Żywiecki [

19], on a plot with a steep slope, with views of the mountain panorama and surrounded by traditional rural buildings and agricultural areas. The landscape is characterized by open spaces of meadows and fields, punctuated by strips of forests, with dominant archetypal forms of barns and houses with gable roofs.

Photo 5, Photo 6. Photographs by Justyna Juroszek

Designers

Architect Kozieł Studio, composed of:

Maciej Kozieł

Edyta Dłutko

The ensemble is known for its projects in the spirit of contemporary reinterpretation of traditional regional forms.

Form and layout

The building has the form of an elongated body with a simple gable roof without eaves, which refers to the traditional form of the Beskid barn, while giving it a minimalist, modern character. The body is set along the slope line, which limits interference with the natural landscape relief.

Facade and materials

The façade of the building is entirely made of vertically arranged, dark larch wood, which will patinate over time, taking on gray shades. The roof is covered with standing seam sheet metal in a dark gray color, which, combined with the façade, creates a monolithic and coherent body. Narrow, vertical windows have been placed in the side façades, while in the gable wall from the viewing side, a large glazing has been designed, which opens the living space to the panorama of the mountains.

Colors and texture

The dominant dark colours of the façade and roof blend in with the surroundings, especially in seasons with low sunlight and dense vegetation.

The impact of façades on the natural landscape

The use of natural wood in a vertical arrangement refers to traditional rural structures, giving the building slenderness and lightness. The dark colour of the wood in combination with the roof in a neutral tone does not create a contrast with the surroundings, but subtly emphasizes the natural colours of the Beskid landscape. The simple, archetypal form of the building makes it harmoniously fit into the traditional landscape of the Beskid villages, while maintaining a distinctive, modern character.

Theoretical interpretation

The project is an example of critical regionalism [

7], where the form of a traditional barn has been reinterpreted in a minimalist spirit, while maintaining local typology and proportions. The house reflects the spirit of the place through the choice of material, form and method of embedding in the terrain [

6], which builds a sense of rootedness in the landscape. The texture of wood, its variability over time and sensory properties affect the perception of the building as an integral part of the surrounding nature [

12], enhancing the experience of the place.

The modern Barn in the Beskid Żywiecki is an excellent example of architecture that consciously and balancedly combines minimalist aesthetics with traditional regional form, creating a building harmoniously inscribed in the mountain landscape. The façade structure based on natural, patinating wood not only refers to local rural architecture, but also emphasizes the relationship of the building with the surrounding nature, changing with the passage of time and seasons. The archetypal, simple shape gives the building a timeless character, and at the same time allows it to discreetly blend into the Beskid landscape, not dominating it, but complementing it. The Modern Barn is a model example of a contemporary reinterpretation of architectural tradition, in which aesthetics, functionality and respect for the cultural and natural context create a coherent and valuable whole [

20].

Natural stone house in Borowiec, Poland

Location and context

The building is located in Borowiec, near Poznań, surrounded by low-rise single-family buildings and forest areas characteristic of Wielkopolska. The plot borders a pine forest, and the natural surroundings, the colors of the soil and vegetation determine the design aesthetics.

Photo 7, Photo 8. Photographs by Justyna Juroszek

Designers

The Milwicz Architects studio, founded by Natalia Milwicz, is known for its projects characterized by a minimalist form and strong embedding in the natural context, as well as for attention to material details.

Form and layout

The building has the form of a modern, compact body with a flat roof, fragmented by height differences and recesses of individual parts of the façade. The horizontal form, stretched along the plot, opens the interiors to the forest garden.

Facade and materials

The façade of the building has been finished with natural stone in shades of gray and beige, arranged in the form of cut blocks of various heights and lengths, which creates the effect of an irregular, natural texture. Stone covers the entire surface of the façade, thanks to which the building visually merges with the space of the garden and the surrounding forest. The whole composition is complemented by large glazing, which opens the living spaces to the landscape and introduces abundant, natural light into the interiors. In addition, fragments of the façade are finished with plaster in a neutral color, which emphasizes the rhythm and balanced composition of the whole.

Colors and texture

The grey-beige shades of the stone create consistency with the colours of the soil, tree bark and forest stones, giving the building the impression of being rooted in the landscape.

The impact of façades on the natural landscape

The use of natural stone in the façade strengthens the building's relationship with the surrounding forest landscape, evoking archetypal earth and rock materials. The subdued colors harmonize with the surroundings, thanks to which the building becomes a subtle element of the space. The fragmented body and horizontal composition make the building integrate with the terrain, minimizing its visual dominance.

Theoretical interpretation

The project is in line with the ideas of critical regionalism, where local materials and natural colours are used in a minimalist, contemporary form, building a relationship between tradition and modernity [

7]. Stone as a façade material emphasizes the spirit of the place, the forest landscape and the soil of Wielkopolska [

6], introducing architecture into the rhythm and aesthetics of the surroundings. The structure and texture of the stone create a rich tactile and visual experience [

12], enhancing the multi-sensory experience of users and inscribing the building in the natural cycles of nature.

The natural stone house in Borowiec, which is an excellent example of architecture, which consciously combines a contemporary, minimalist form with materials deeply rooted in the regional landscape. The structure of the façade based on stone with natural, subdued colors makes the building harmoniously fit into the surroundings, becoming its integral part. At the same time, the stone texture evokes archetypal associations with earth and rocks, emphasizing the relationship between architecture and nature. This project shows that modern architecture can not only coexist with the landscape, but also enrich it, creating a space based on dialogue, respect and a deep understanding of the natural and cultural context. The house in Borowiec, it is proof that the simplicity of form and the authenticity of the material can together build a timeless aesthetic quality that is in harmony with the surrounding world.

Comparative conclusions

Table 1.

Comparison table of façade structures for the four analyzed buildings.

Table 1.

Comparison table of façade structures for the four analyzed buildings.

| Building Authors |

Studio |

Year |

Façade material |

Structure and texture of the façade |

Relation to the natural landscape |

| Façade material |

Toprojekt (Marek Wawrzyniak, Karol Wawrzyniak, Izabela Groborz-Musik) |

2017 |

Clinker brick in a red shade |

Regular brick bonding, natural texture, no decoration, minimalist detail |

Harmonious incorporation into the colors of the earth and forest; reference to the traditional brick buildings of the region |

| Shingle house in Bielsko-Biała |

Iterurban (Weronika Juszczyk, Łukasz Piankowski) |

2013 |

Shingle wood |

Vertical shingle laying, uniform coating on the façade and roof, natural wood texture |

The building blends in with the forest surroundings; Wood patinates, changes colors in the rhythm of nature |

| Modern Barn in the Beskid Żywiecki |

Architect Kozieł (Maciej Kozieł, Edyta Dłutko) |

2020 |

Larch wood + seam sheet |

Vertical arrangement of façade boards, smooth wood texture, dark sheet metal roof, minimalist form |

The form of an archetypal barn inscribed in a mountain landscape; Wood and dark colors blend the building into the surroundings |

| Natural stone house in Borowiec. |

Milwicz Architects (Natalia Milwicz) |

2021 |

Natural stone (grey-beige) |

Irregular stone blocks of different heights and lengths, expressive stone texture |

The stone façade reinforces the building's rootedness in the forest landscape; shades harmonize with the colors of the soil and vegetation |

An analysis of four modern buildings located in different regions of Polish shows that the structure and material of the façade play a key role in shaping the relationship between the building and the natural landscape. Despite the diversity of cultural and natural contexts, it is possible to identify both common tendencies and distinguishing features of individual projects.

Firstly, all buildings integrate with the surroundings through the use of local materials or materials referring to the archetypes of regional construction. Dom Rudy uses clinker bricks, which inscribes it in the tradition of Silesian brick buildings. On the other hand, the House of Shingles and the Modern Barn use wood, referring to the tradition of mountain and forest construction. On the other hand, the House of Natural Stone in Borowiec, on the other hand, uses raw material directly related to the forest and mineral landscape of Wielkopolska.

Secondly, all the analysed examples are dominated by minimalist architectural forms of an archetypal character. Simple blocks, often with a gable roof or cuboid shape, are devoid of excess decoration. This emphasizes the structure and quality of the material, allowing it to harmoniously fit into the landscape without unnecessary domination.

Thirdly, the texture and variability of façade materials play an important role. In wooden buildings, such as the Shingle House and the Modern Barn, as well as in the stone house in Borowiec, the natural aging and patination of the surface causes these buildings to blend more and more with the surroundings over time. Even the clinker brick of Dom Rudy, despite its stable colors, refers to the earthy colors of the local landscape.

Fourthly, the archetypal form is an important element of the dialogue between the building and the landscape. Three of the analysed objects – the Rudy House, the Shingle House and the Modern Barn – use forms referring to traditional country houses or barns, which strengthens their cultural roots. On the other hand, the Natural Stone House in Borowiec, on the other hand, is characterized by a more contemporary, horizontal form, but the building material still builds a sense of deep connection with the local soil and landscape.

Finally, the façade plays the role of a mediator in these projects, connecting architecture with the natural environment. Thanks to the conscious selection of material, colour and textural structure, these buildings implement the idea of the so-called critical regionalism, described by Kenneth Frampton, in which a modern form is embedded in the local cultural and natural context. At the same time, they are in line with the assumptions of the phenomenology of architecture, which emphasize that the structure and texture of the façade affect the perception of the place and build a deep, emotional relationship between users and the landscape, in accordance with the concepts of Norberg-Schulz and Pallasma.