Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

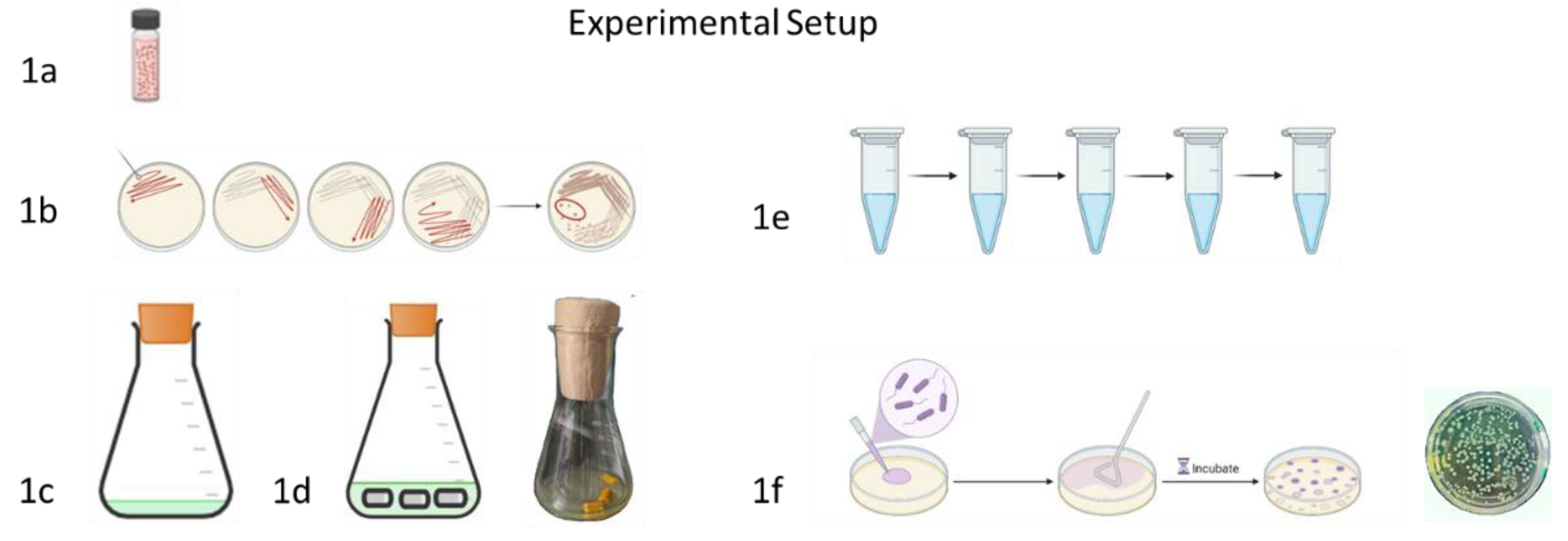

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Organisms

2.2. Growth Media and Anti-Biofilm Substances

2.3. Chemical Syntheses

2.3.1. n-Undecyl-α-d-mannopyranoside (MW = 334.35g)

2.3.2. n-Undecyl-α/β-l-fucopyranoside (MW = 318.35 g)

2.4. Bacterial Incubation

2.5. Determination of Minimal Inhibitory Concentration

2.6. Urinary Catheters and Processing

2.7. Catheter Biofilm Experiments

2.7.1. General Procedure Catheter Experiment

2.7.2. Influence of the Culture Medium

2.7.3. Curcumin, Monolaurin, Resveratrol, Each in Combination with Soluplus

2.7.4. n-Undecylglycosides

2.7.5. Terrein

2.7.6. Co-Effects of Terrein and Polyhexanide

2.8. Estimation of Colony Forming Units

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Syntheses

3.1.1. n-Undecyl-α-d-Mannopyranoside

3.1.2. n-Undecyl-α/β-l-Fucopyranoside

3.2. MIC-Values

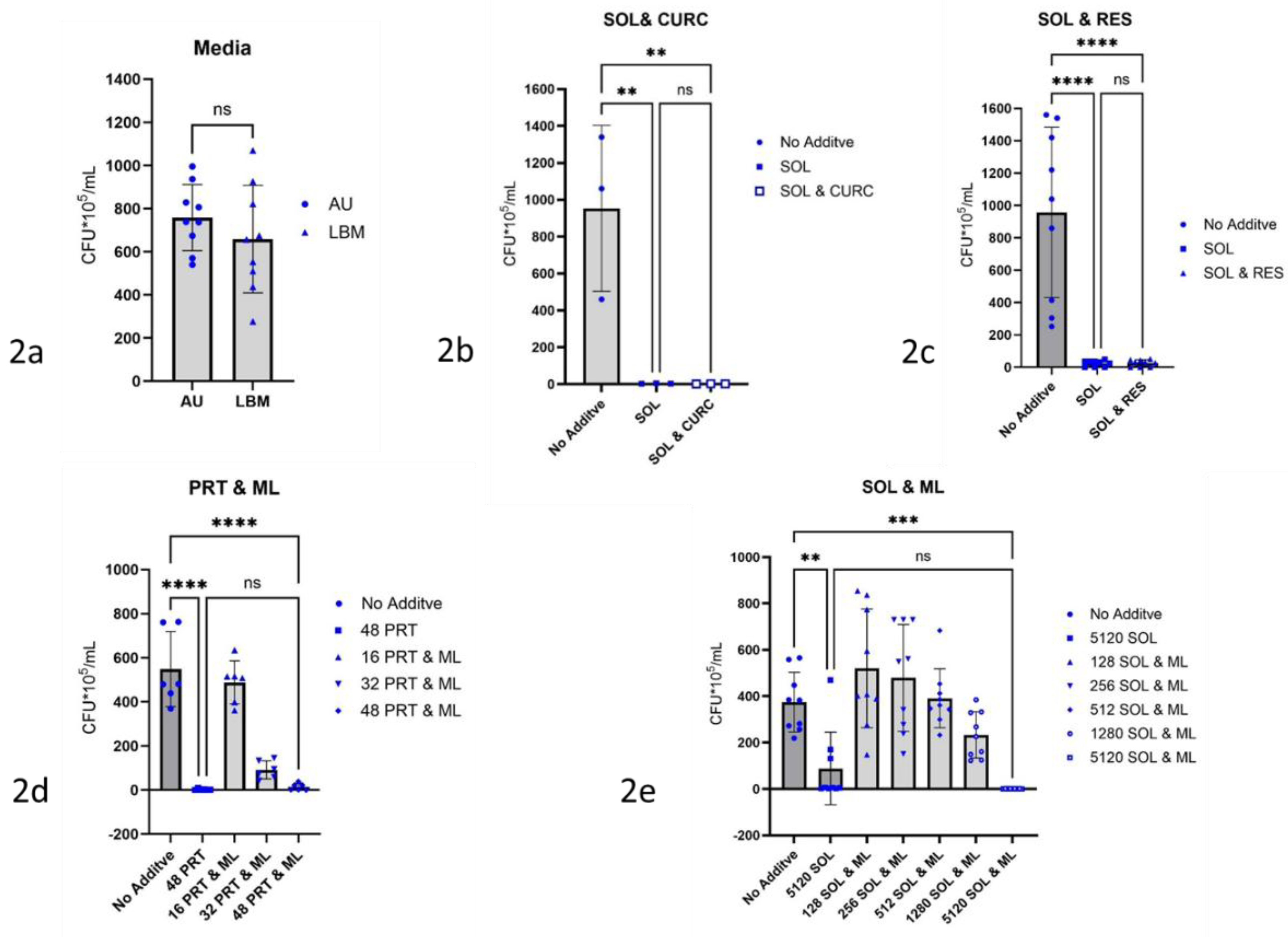

3.3. Dependence of Biofilm Formation on the Culture Medium

3.4. Growth Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Biofilms

3.4.1. Curcumin, Monolaurin, Resveratrol Each with Detergent

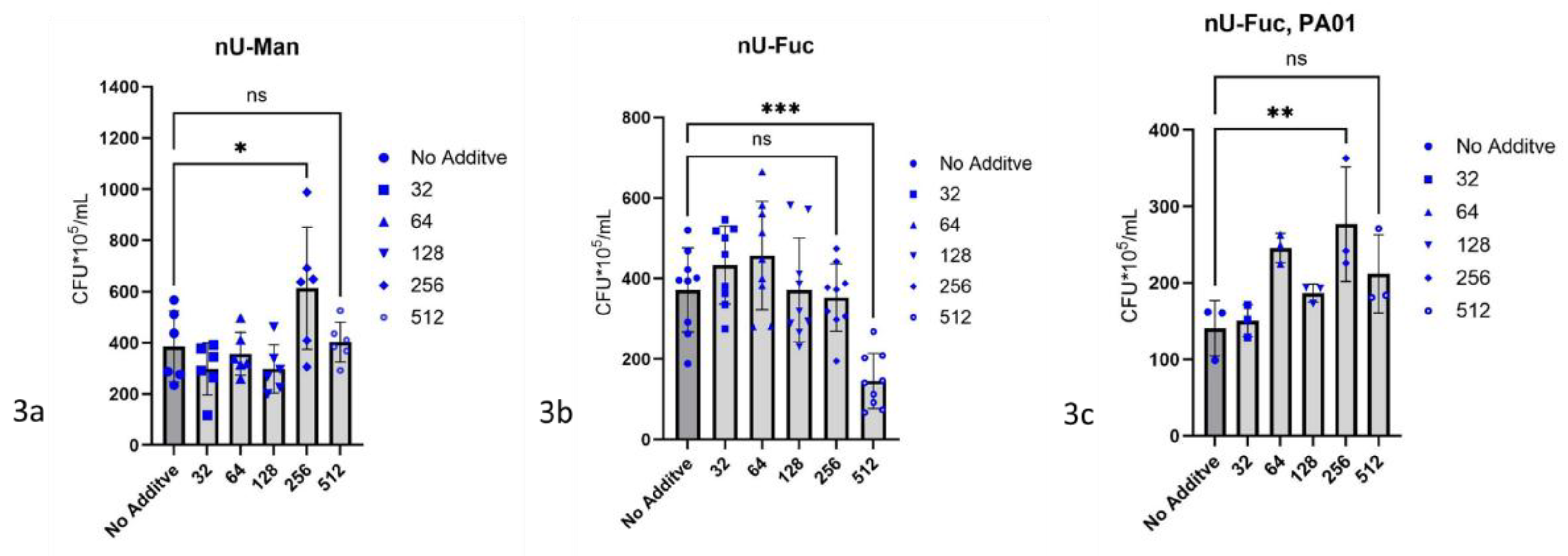

3.4.2. n-Undecyl-α-d-mannopyranoside

3.4.3. n-Undecyl-α/β-l-fucopyranoside

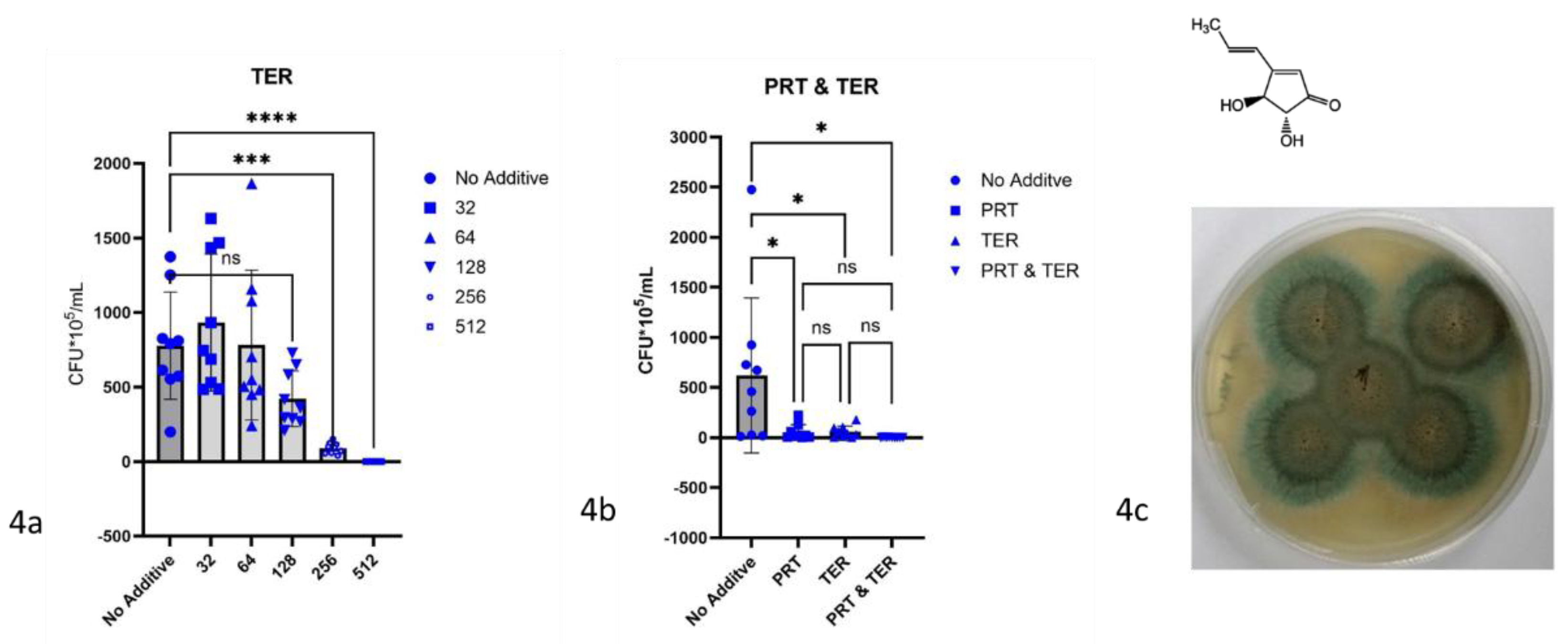

3.4.4. Terrein

3.4.6. Co-Effects of Terrein and Polyhexanide

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Xuejie; Gu, Nixuan; Huang, Teng Yi; Zhong, Feifeng; Peng, Gongyong: Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A typical biofilm forming pathogen and an emerging but underestimated pathogen in food processing. Front Microbiol. 2023 Jan 25:13:1114199. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Huiluo; Lai, Yong; Bougouffa, Salim; Xu, Zeling; Yan, Aixin: Comparative genome and transcriptome analysis reveals distinctive surface characteristics and unique physiological potentials of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853. BMC Genomics. 2017 Jun 12;18(1):459. [CrossRef]

- Singha, Priyadarshini; Locklin, Jason; Handa, Hitesh: A review of the recent advances in antimicrobial coatings for urinary catheters. Acta Biomater. 2017 Mar 1:50:20-40. [CrossRef]

- Kranz, Jennifer; Schmidt, Stefanie; Wagenlehner, Florian; Schneidewind, Laila: Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections in Adult Patients. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020 Feb 7;117(6):83-88. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Zhiling; Wang, Ziping; Li, Siheng; Yuan, Xun: Antimicrobial strategies for urinary catheters. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2019 Feb;107(2):445-467. [CrossRef]

- Rasamiravaka, Tsiry; Labtani, Quentin; Duez, Pierre; El Jaziri, Mondher: The formation of biofilms by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a review of the natural and synthetic compounds interfering with control mechanisms. Biomed Res Int. 2015:2015:759348. [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Fırat Yavuz; Darcan, Cihan; Kariptaş, Ergin: The Determination, Monitoring, Molecular Mechanisms and Formation of Biofilm in E. coli. Braz J Microbiol. 2023 Mar;54(1):259-277. [CrossRef]

- Sauer, Karin; Camper, Anne K.; Ehrlich, Garth D.; Costerton, J. William; Davies, David G.: Pseudomonas aeruginosa displays multiple phenotypes during development as a biofilm. J Bacteriol. 2002 Feb;184(4):1140-54. [CrossRef]

- Laventie, Benoît-Joseph; Sangermani, Matteo; Estermann, Fabienne; Manfredi, Pablo; Planes, Rémi; Hug, Isabelle et al.: A Surface-Induced Asymmetric Program Promotes Tissue Colonization by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cell Host Microbe. 2019 Jan 9;25(1):140-152.e6. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Luyan; Conover, Matthew; Lu, Haiping; Parsek, Matthew R.; Bayles, Kenneth; Wozniak, Daniel J.: Assembly and development of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. PLoS Pathog. 2009 Mar;5(3):e1000354. [CrossRef]

- Bagge, Niels; Hentzer, Morten; Andersen, Jens Bo; Ciofu, Oana; Givskov, Michael; Høiby, Niels: Dynamics and spatial distribution of beta-lactamase expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004 Apr;48(4):1168-74. [CrossRef]

- Bjarnsholt, Thomas: The role of bacterial biofilms in chronic infections. APMIS Suppl. 2013 May:(136):1-51. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, Lucas R.; D'Argenio, David A.; MacCoss, Michael J.; Zhang, Zhaoying; Jones, Roger A.; Miller, Samuel I.: Aminoglycoside antibiotics induce bacterial biofilm formation. Nature. 2005 Aug 25;436(7054):1171-5. [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, Maria; Isacchi, Benedetta; van Bloois, Louis; Torano, Javier Sastre; Ket, Aldo; Wu, Xiaojie et al.: Improving solubility and chemical stability of natural compounds for medicinal use by incorporation into liposomes. Int J Pharm. 2011 Sep 20;416(2):433-42. [CrossRef]

- Cox, Fionnuala; Khalib, Khairin; Conlon, Niall: PEG That Reaction: A Case Series of Allergy to Polyethylene Glycol. J Clin Pharmacol. 2021 Jun;61(6):832-835. [CrossRef]

- Hendrik Hardung, Dejan Djuric, and Shaukat Ali: Combining HME & Solubilization: Soluplus® - The Solid Solution Drug Delivery Technology 2010 Vol 10 No 3, 20-27 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279893959_Combining_HME_solubilization_SoluplusR_-_The_solid_solution.

- Ji, Suping; Lin, Xiao; Yu, Enjiang; Dian, Chengyang; Yan, Xiong; Li, Liangyao et al.: Curcumin-Loaded Mixed Micelles: Preparation, Characterization, and In Vitro Antitumor Activity. J. Nanotechnology 2018, 2018(1):9103120. [CrossRef]

- Shamma, Rehab N.; Basha, Mona: Soluplus®: A novel polymeric solubilizer for optimization of Carvedilol solid dispersions: Formulation design and effect of method of preparation. Powder Technol. 237 2013: 406–414. [CrossRef]

- Saydam, Manolya; Cheng, Woei Ping; Palmer, Nathan; Tierney, Robert; Francis, Robert; MacLellan-Gibson, Kirsty et al.: Nano-sized Soluplus® polymeric micelles enhance the induction of tetanus toxin neutralizing antibody response following transcutaneous immunization with tetanus toxoid. Vaccine. 2017 Apr.25;35(18): 2489–2495. [CrossRef]

- Noordman, Wouter H.; Janssen, Dick B.: Rhamnolipid stimulates uptake of hydrophobic compounds by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002 Sep;68(9):4502-8. [CrossRef]

- Baik, Seo; Lau, Jason; Huser, Vojtech; McDonald, Clement J.: Association between tendon ruptures and use of fluoroquinolone, and other oral antibiotics: a 10-year retrospective study of 1 million US senior Medicare beneficiaries. BMJ Open. 2020 Dec 21;10(12):e034844. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Meiyan; Li, Hongzhe; Johnson, Anastasiya; Karasawa, Takatoshi; Zhang, Yuan; Meier, William B. et al.: Inflammation up-regulates cochlear expression of TRPV1 to potentiate drug-induced hearing loss. Sci Adv. 2019 Jul 17;5(7):eaaw1836. [CrossRef]

- Boucher, Helen W.; Talbot, George H.; Bradley, John S.; Edwards, John E.; Gilbert, David; Rice, Louis B. et al.: Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Jan 1;48(1):1-12. [CrossRef]

- Sandegren, Linus: Selection of antibiotic resistance at very low antibiotic concentrations. Ups J Med Sci. 2014 May 19;119(2):103–107. [CrossRef]

- Shlaes, David M.; Sahm, Dan; Opiela, Carol; Spellberg, Brad: The FDA reboot of antibiotic development. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013 Oct;57(10):4605-7. [CrossRef]

- Loose, Maria; Pilger, Emmelie; Wagenlehner, Florian: Anti-Bacterial Effects of Essential Oils against Uropathogenic Bacteria. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020 Jun 25;9(6):358. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Derong; Xiao, Lijuan; Qin, Wen; Loy, Douglas A.; Wu, Zhijun; Chen, Hong; Zhang, Qing: Preparation, characterization and antioxidant properties of curcumin encapsulated chitosan/lignosulfonate micelles. Carbohydr Polym. 2022 Apr 1:281:119080. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Lin; Liang, Rongxin; Duan, Jingjing; Song, Songze; Pan, Yunjun; Liu, Hui et al.: Synergistic antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities of resveratrol and polymyxin B against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2022 Oct;75(10):567-575. [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, Courtney; Bertozzi, Carolyn; Georg, Gunda I.; Kiessling, Laura; Lindsley, Craig; Liotta, Dennis et al.: The Ecstasy and Agony of Assay Interference Compounds. J Med Chem. 2017 Mar 23;60(6):2165-2168. [CrossRef]

- Baell, Jonathan; Walters, Michael A.: Chemistry: Chemical con artists foil drug discovery. Nature. 2014 Sep 25;513(7519):481-3. [CrossRef]

- Ding, T., Li, T., Wang, Z., Li, J.: Curcumin liposomes interfere with quorum sensing system of Aeromonas sobria and in silico analysis. Sci Rep. 2017 Aug 17;7(1):8612. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, Susana; Borges, Anabela; Gomes, Inês B.; Sousa, Sérgio F.; Simões, Manuel: Curcumin and 10-undecenoic acid as natural quorum sensing inhibitors of LuxS/AI-2 of Bacillus subtilis and LasI/LasR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Food Res Int. 2023 Mar:165:112519. [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, Hayder; Misba, Lama; Ahmad, Shabbir; Khan, Asad U.: Curcumin induced photodynamic therapy mediated suppression of quorum sensing pathway of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: An approach to inhibit biofilm in vitro. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2020 Jun:30:101645. [CrossRef]

- Oh, D. H.; Marshall, D. L. (1993): Antimicrobial activity of ethanol, glycerol monolaurate or lactic acid against Listeria monocytogenes. Int J Food Microbiol. 1993 Dec;20(4):239-46. [CrossRef]

- Kabara, J. J.; Swieczkowski, D. M.; Conley, A. J.; Truant, J. P.: Fatty acids and derivatives as antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1972 Jul;2(1):23-8. [CrossRef]

- Sommer R, Exner TE, Titz A: A Biophysical Study with Carbohydrate Derivatives Explains the Molecular Basis of Monosaccharide Selectivity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lectin LecB. PLoS One. 2014 Nov 21;9(11):e112822. [CrossRef]

- Sommer, Roman; Wagner, Stefanie; Rox, Katharina; Varrot, Annabelle; Hauck, Dirk; Wamhoff, Eike-Christian et al.: Glycomimetic, Orally Bioavailable LecB Inhibitors Block Biofilm Formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (7): 2537–2545. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Bomin; Park, Ji-Su; Choi, Ha-Young; Yoon, Sang Sun; Kim, Won-Gon: Terrein is an inhibitor of quorum sensing and c-di-GMP in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a connection between quorum sensing and c-di-GMP. Sci Rep 8, 8617 (2018). [CrossRef]

- W Auerbach, Joseph; Weinreb, Steven M.: Synthesis of terrein, a metabolite of Aspergillus terreus. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun., 1974, 298-299. [CrossRef]

- Klunder, A.J.H.; Bos, W.; Zwanenburg, B.: An efficient stereospecific total synthesis of (±)-terrein. Tetrahedron Letters 1981 22 (45), 4557–4560. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Dan; Yang, Jianni; Li, Chen; Hui, Yang; Chen, Wenhao: Recent Advances in Isolation, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Terrein. Chem Biodivers. 2021 Dec;18(12):e2100594. [CrossRef]

- Altenbach, Hans-Josef; Holzapfel, Winfried: Synthesis of (+)-Terrein from L-Tartaric Acid. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl Vol.29, 1 Jan 1990 p. 67-68. [CrossRef]

- T Asfour, Hani Z.; Awan, Zuhier A.; Bagalagel, Alaa A.; Elfaky, Mahmoud A.; Abdelhameed, Reda F. A.; Elhady, Sameh S.: Large-Scale Production of Bioactive Terrein by Aspergillus terreus Strain S020 Isolated from the Saudi Coast of the Red Sea. Biomolecules 2019 9, 480. [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, J.; Woch, J.; Mościpan, M.; Nowakowska-Bogdan, E.: Micellar effect on the direct Fischer synthesis of alkyl glucosides. Appl Catal A: Gen 2017 539, p. 13–18. [CrossRef]

- Stickler, D. J.; Morris, N. S.; Winters, C.: Simple physical model to study formation and physiology of biofilms on urethral catheters. Methods Enzymol. 1999:310:494-50. [CrossRef]

- Loose, Maria; Naber, Kurt G.; Hu, Yanmin; Coates, Anthony; Wagenlehner, Florian: Serum bactericidal activity of colistin and azidothymidine combinations against mcr-1-positive colistin-resistant Escherichia coli. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018 Dec;52(6):783-789. [CrossRef]

- https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/QC/v_12.0_EUCAST_QC_tables_routine_and_extended_QC.pdf48.

- Jones, Steven M.; Yerly, Jerome; Hu, Yaoping; Ceri, Howard; Martinuzzi, Robert: Structure of Proteus mirabilis biofilms grown in artificial urine and standard laboratory media. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007 Mar;268(1):16-21. [CrossRef]

- Loose, Maria; Naber, Kurt G.; Purcell, Larry; Wirth, Manfred P.; Wagenlehner, Florian M. E.: Anti-Biofilm Effect of Octenidine and Polyhexanide on Uropathogenic Biofilm-Producing Bacteria. Urol Int. 2021; 105 (3-4): 278-284. [CrossRef]

- Hola, Veronika; Peroutkova, Tereza; Ruzicka, Filip: Virulence factors in Proteus bacteria from biofilm communities of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012 Jul;65(2):343-9. [CrossRef]

- Sommer, Roman; Rox, Katharina; Wagner, Stefanie; Hauck, Dirk; Henrikus, Sarah S.; Newsad, Shelby et al.: Anti-biofilm Agents against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A Structure-Activity Relationship Study of C-Glycosidic LecB Inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2019 Oct 24;62(20):9201-9216. [CrossRef]

- https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/DE/de/product/sigma/t5705?srsltid=AfmBOory9kFAwnPgePBFzgs71ECzIj_LE8GZGAo4lxziIEK9f-eytRf_.

- Kasorn A, Loison F, Kangsamaksin T, Jongrungruangchok S, Ponglikitmongkol M. Terrein inhibits migration of human breast cancer cells via inhibition of the Rho and Rac signaling pathways. Oncol Rep. 2018 Mar;39(3):1378-1386. [CrossRef]

| Substance | Abbreviation | Literature | Vendor |

| Curcumin & Soluplus | CURC & SOL | ||

| Curcumin | CURC | Abdulrahman et al. 2020 [33] | Merck Millipore # CAS 458-37-7 |

| Resveratrol & Soluplus | RES & SOL | ||

| Resveratrol | RES | Qi et al. 2022 [28] | TCI # CAS RN®: 501-36-0 |

| Soluplus | SOL | Shamma and Basha 2013 [18] |

BASF SE Ludwigshafen am Rhein Germany |

| Monolaurin | ML | Oh and Marshall 1993 [34]; Kabara et al. 1972 [35] | TCI # CAS RN®: 142-18-7 |

| Monolaurin & Soluplus | ML & SOL | ||

| Prontosan | PRT | Loose et al. 2021[50] | B. Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany |

| Terrein | TER | Kim et al. 2018 [38] | AdipoGen # CAS-No. 582-46-7 |

| Terrein & Prontosan | TER & PRT | ||

| n-Undecyl-α-D-Mannopyranoside | nU-Man | Nowicki et al. 2017 [44]; Sommer et al. 2018 [37] |

laboratory synthesis |

| n-Undecyl-α/β-L-Fucopyranoside | nU-Fuc | Nowicki et al. 2017 [44]; Sommer et al. 2018 [37] |

laboratory synthesis |

| Piperacillin & Soluplus | PIP & SOL | ||

| Piperacillin | PIP | EUCAST QC Tables [48] | Sigma-Aldrich # CAS-No. 66258-76-2 |

| Substance | MIC in AU (P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853) |

| Curcumin & Soluplus | > 512 & > 5,120 |

| Curcumin | not determined |

| Resveratrol & Soluplus | > 512 & > 5,120 |

| Resveratrol | > 512 |

| Soluplus | > 5120 |

| Monolaurin | > 512 |

| Monolaurin & Soluplus | |

| Prontosan | 32/ 32 |

| Terrein | 512 |

| Terrein & Prontosan | 128 & 32/16 |

| n-Undecyl-α-D-Mannopyranoside | not determined |

| n-Undecyl-α/β-L-Fucopyranoside | not determined |

| Piperacillin & Soluplus | 4 & 40 |

| Piperacillin | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).