Introduction

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is a monogenic disorder of hemoglobin that leads to production of the abnormal hemoglobin S [

1]. As a term, SCD encompasses sickle cell anaemia (SCA) and the various heterozygous states of hemoglobin S with other hemoglobinopathies [

2]. According to literature, the prevalence of VTE in this disease is as high as 25%, with various risk factors as key contributors [

3]. Despite inherent risk of thrombosis, there are no clear guidelines for thromboprophylaxis, while use rates are concerningly low [

4].

SCD is characterized by several pathogenetic mechanisms. The trigger for the pathophysiology of the disease is polymerization of HbS, which converts red blood cells into rigid, fragile sickle cells that adhere more easily to the vascular endothelium [

5,

6,

7]. This attachment contributes to a second mechanism, the vascular occlusion which is observed in both small and large vessels [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Simultaneously, the fragility of red blood cells triggers chronic hemolysis that occurs both intravascularly and extravascularly, resulting in activation of various cell populations and the release of signaling molecules, most importantly hemoglobin [

1,

6,

7,

14,

15]. The fourth component of pathophysiology is oxidative stress, which, destabilizes the cell membrane, contributing to the acceleration of hemolysis and the activation of coagulation [

7,

16]. Finally, many disruptions of the coagulation cascade have been observed. Reduction of coagulation factors and anticoagulant molecules and resistance of fibrin to fibrinolysis have been proven. These processes in combination with the mechanism of immunothrombosis, secretion of microvesicles and the activation of platelets and neutrophils promote thrombosis [

6,

17].

Methods

Delving deeper into the interaction of SCD and thrombosis, we conducted a retrospective observational study at the Adults Thalassaemia and Sickle Cell Disease Unit of the Hippokration Hospital of Thessaloniki using data from 01/01/1999 to 31/11/2024. Objectives of the study were to measure the prevalence of thrombosis and VTE in patients with SCD and the evaluation and comparison of known risk factors.

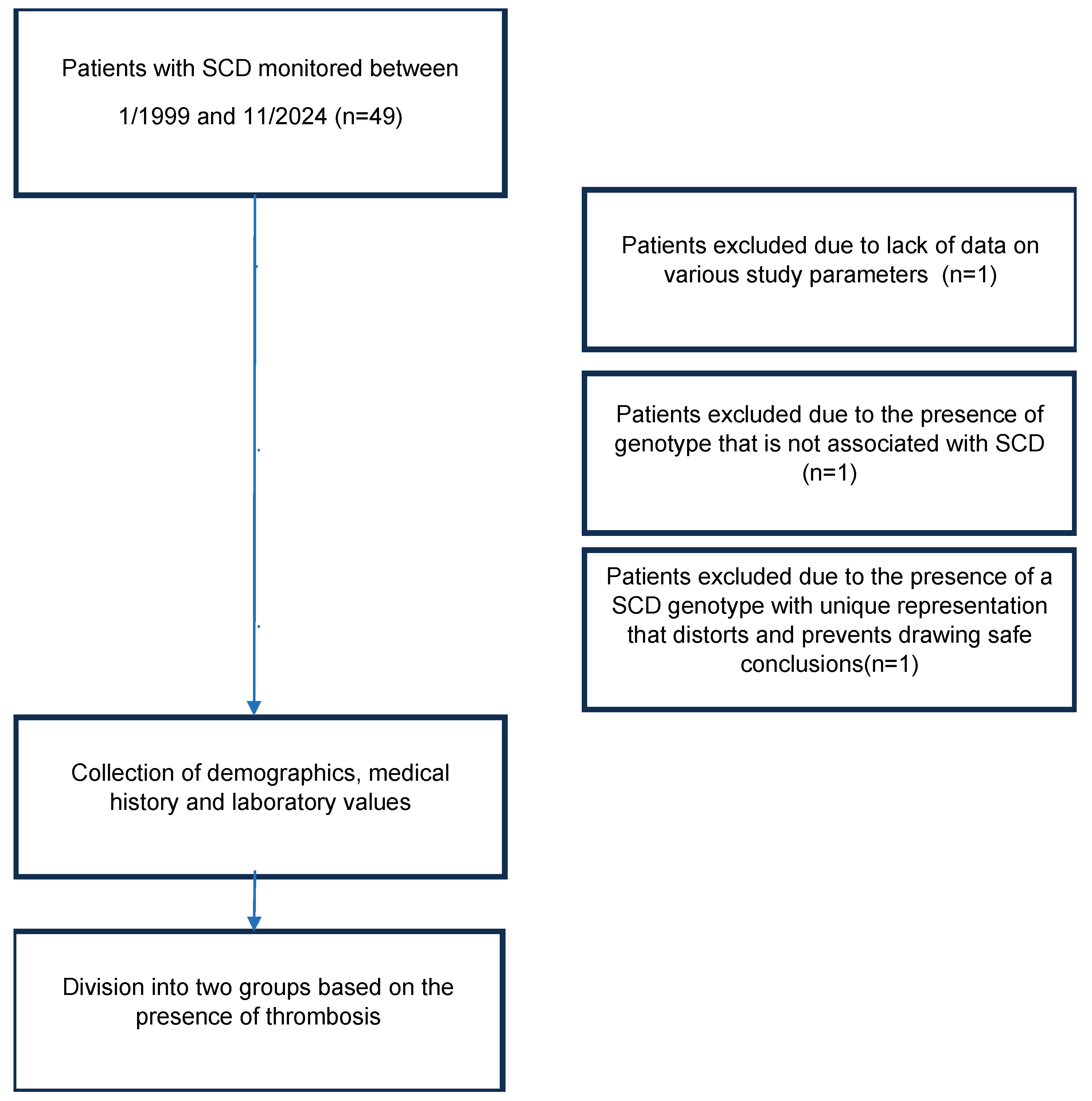

Inclusion criteria included a genotype compatible with SCD. Three patients were excluded from the study. The first patient had insufficient data regarding the various study parameters as she had only recently started monitoring at the Thalassaemia and Sickle Cell Disease Unit. In the second patient, the molecular genetic testing showed that she did not have SCD genotype. As for the third patient, she has a complex genotype of compound heterozygous sickle cell and β-thalassaemia and heterozygous mild α-thalassaemia being the only individual with that genotype. After conducting both univariate and multivariate studies, it was found that her participation in the study altered the remaining parameters and conclusions to a statistically significant degree, so it was prudent not to be included. (

Figure 1)

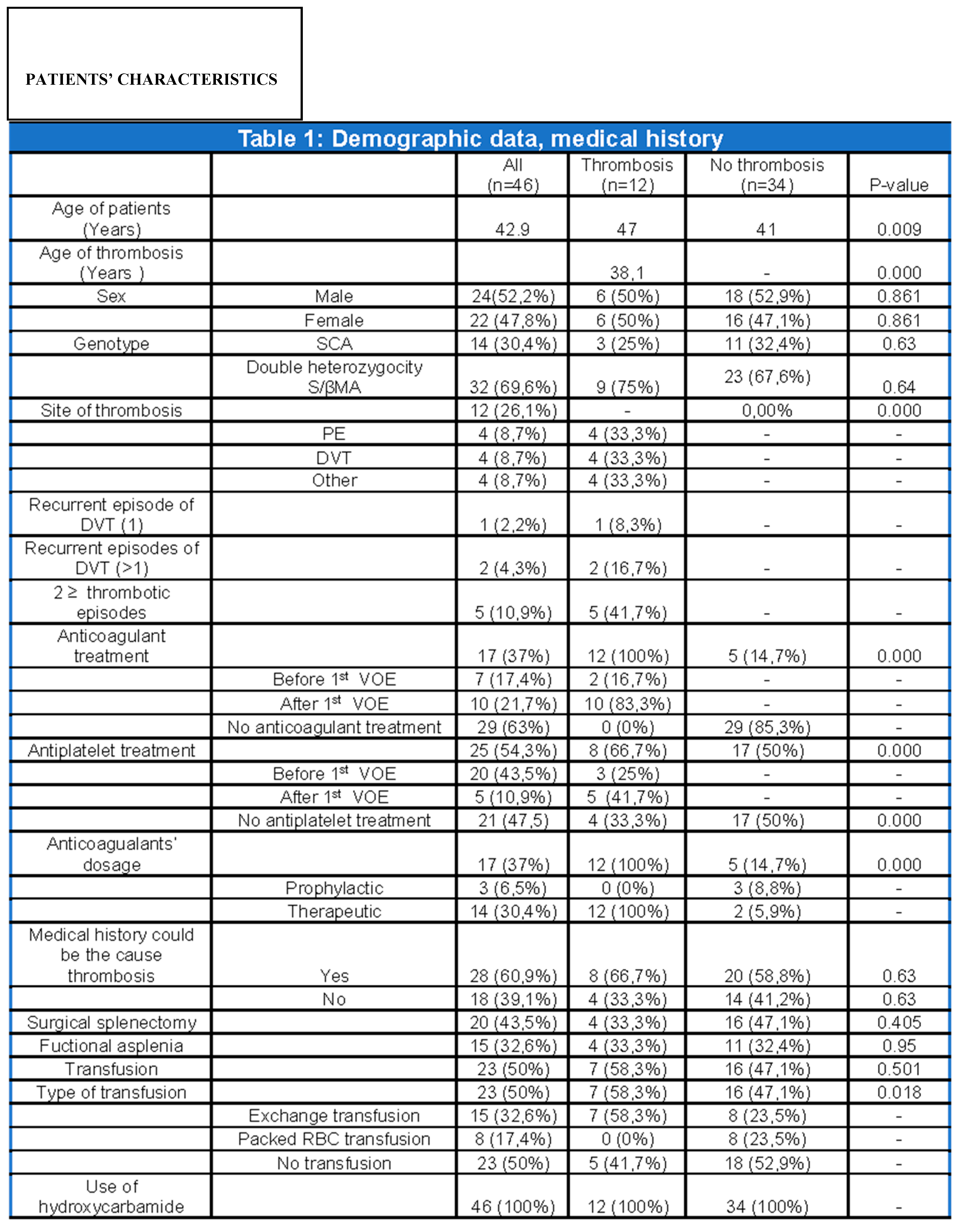

After obtaining relevant permission from the hospital’s Ethics Committee for each patient, we reviewed all medical files from the Thalassaemia and Sickle Cell Disease Unit. Information relevant to the duration and etiology of anticoagulant treatment, disease genotype, history of splenectomy or functional asplenia, the demographic characteristics and the association of these recordings and other concomitant diseases with thrombosis was analyzed. (

Table 1)

Baseline values of hemoglobin, white blood cells, platelets, HbS, HbF were also recorded before the first thrombotic episode. (

Table 2)

Data analysis

The study included quantitative and qualitative variables. Quantitative are described through mean value as well as measures of dispersion (standard deviation, minimum and maximum value), while qualitative variables are expressed in numbers and percentages of participants pertaining to all variables.

Subsequently, the normality hypothesis for quantitative variables was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. The former test is designed and widely recommended for samples smaller than 50 experimental units, while the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test is more applicable for samples over 50 experimental units. Given the fact that sample size was near 50, both normality tests were applied and indicated that for most variables, the p-values are less than 0.05, pointing to the rejection of the null hypothesis. Therefore, the variables do not follow a normal distribution and focus was shifted towards a non-parametric statistical analysis.

As a way to evaluate the differences between two or more groups, the Mann-Whitney U Test and Kruskal-Wallis Test were used, suited for groups that do not follow a normal distribution or for small statistical samples. The Crosstabulations test with Chi-Square Test were used to examine the possibility of whether two categorical (qualitative) variables are associated with each other or whether the differences observed are random or statistically significant. Finally, the linear regression test was performed, so as to investigate the relationship between a scalar variable and one or more explanatory variables (or independent variables). Throughout the study, percentages were rounded up to the first decimal place.

Results

1. Patient characteristics

Forty six patients with SCD who are monitored at the Adults Thalassaemia and Sickle Cell Disease Unit were reviewed. Thirty two (69.6%) have the S/βMA double heterozygosity while 14 (30.4%) have the SCA genotype. The sample is almost uniform across men and women, providing balance in the gender analysis, while the average age of the individuals at the time of the analysis is 42.9 years. (

Table 1)

It should be clarified that percentages and statistical tests refer to the first episode of thrombosis. The small sample size, in conjunction with an even smaller subpopulation with recurrent episodes, made it impossible to use statistical models in the population with more than one VOE as conclusions would not be objective. Moreover, in the context of anticoagulant and antiplatelet treatment, the “before thrombosis” section included patients who did not experience any thrombotic incidents

2. Frequency of Thrombotic and Venous Thromboembolic events

The prevalence of thrombosis based on the 1

st episode was 26.1% (12/46) while the prevalence of VTE was 17.4% (8/46). The median age of the 1

st thrombotic event was 38.1 years. (

Table 1)

3. Clinical factors associated with thrombosis

The univariate analysis showed that thrombosis is statistically associated with patient’s age (p=0.009), age of thrombosis (p=0.000), antiplatelet treatment (p=0.000), anticoagulant treatment (p=0.000) and its dose (p=0.000). Finally, a significant correlation emerged between the type of transfusion and thrombosis (p=0.018) (

Table 1).

4. Laboratory tests associated with thrombosis

On the contrary, none of the laboratory values studied, were found to be statistically significant in any analysis. (

Table 2)

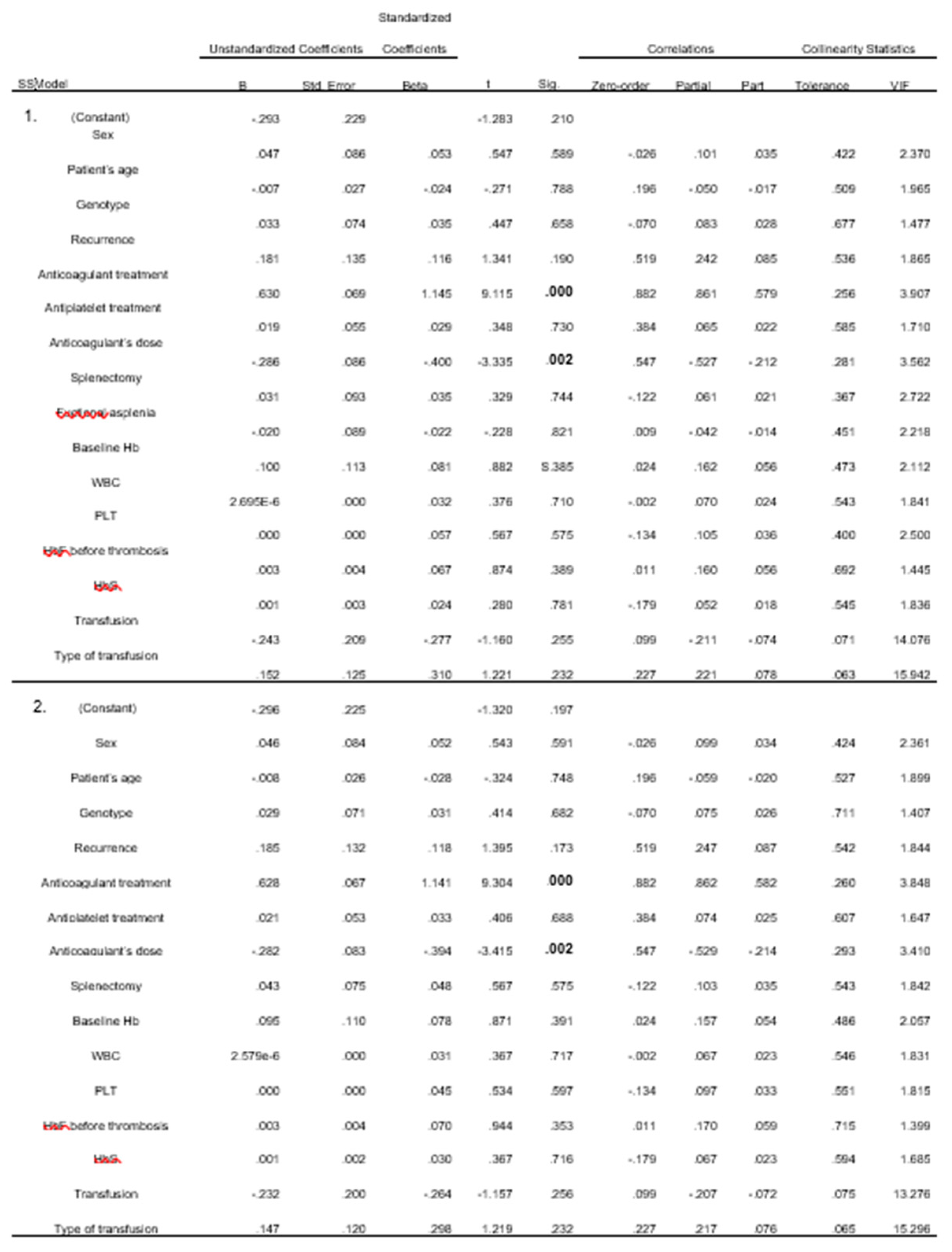

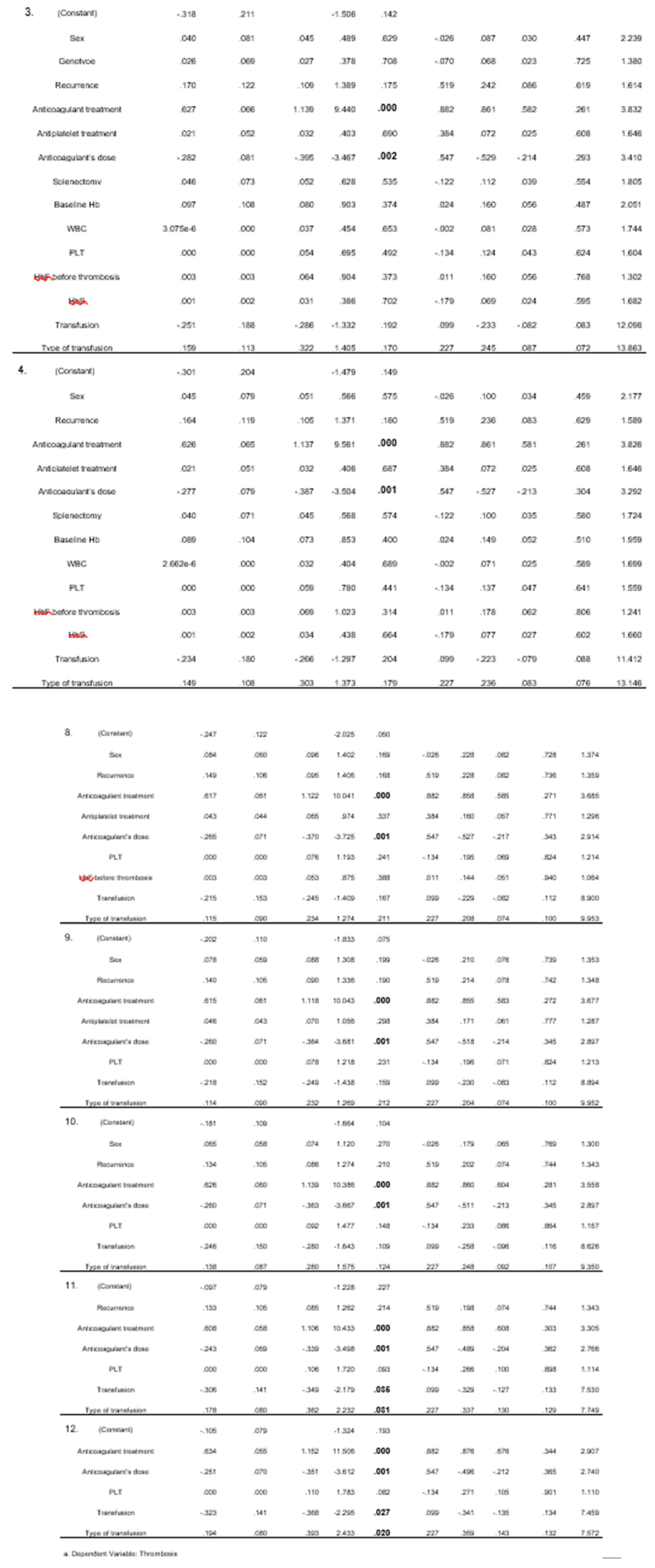

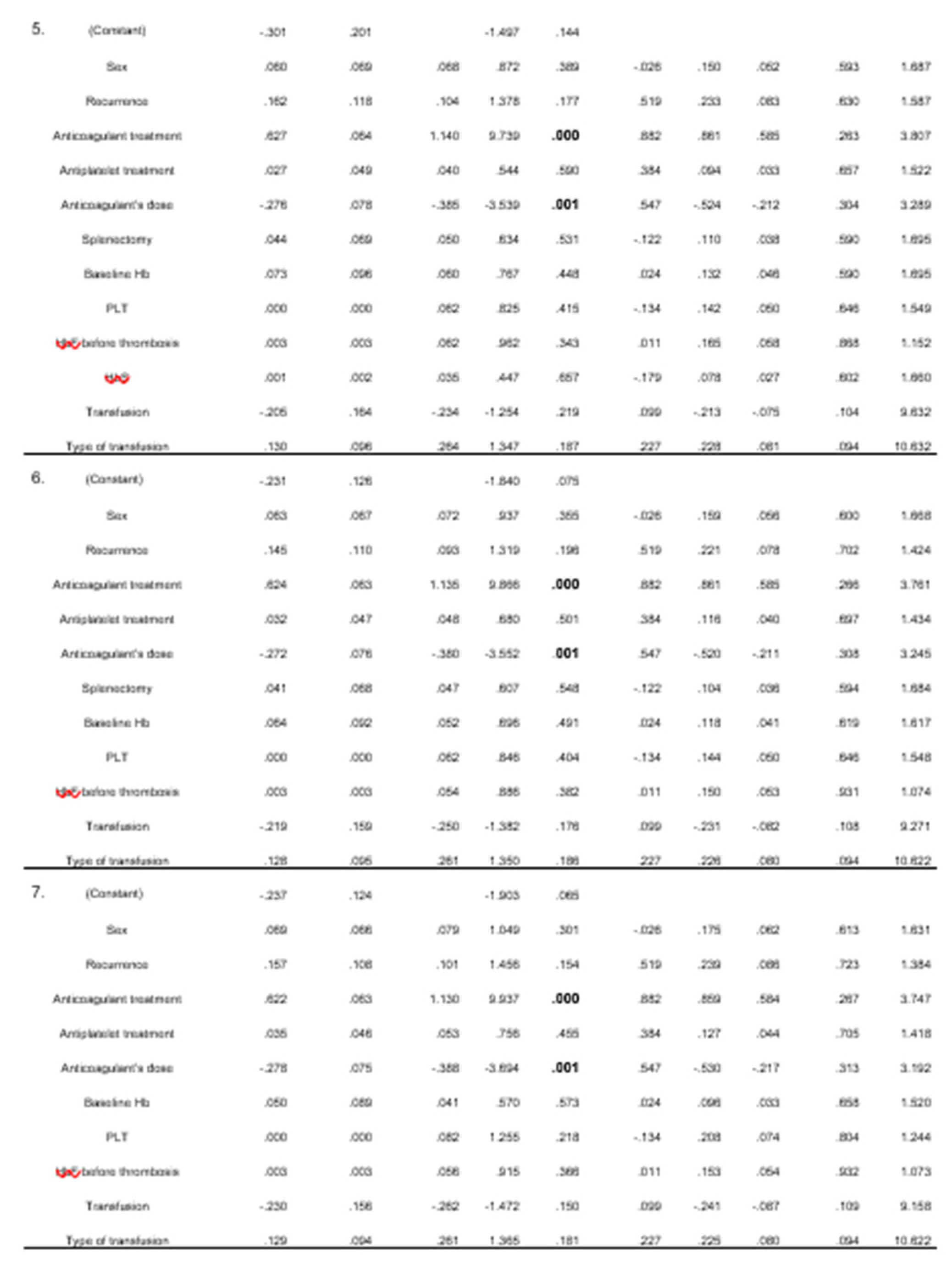

From the linear regression analysis, 12 models emerged. In all models, the administration of anticoagulants and their dose were found to be statistically significant. Blood transfusion and its type were found to be less significant, with two models indicating this correlation. (

Table 3)

5. Subpopulation with thrombotic events

Among the 12 patients with thrombosis equal representation of both sexes (6 men and 6 women) is found while the mean age of the first episode of thrombosis was 38.1 years for the first VOE. Eight of the first events were VTE. (

Table 1)

Nine patients (75%) had S/βMA heterozygosity and 3 had SCA (25%). All treated with anticoagulant treatment at a therapeutic dose. Ten (83.3%) started anticoagulants after the first episode of thrombosis while 2 (16.7%) prior (due to a history of AF and tibial artery stenosis). Among the 10 patients, 4 were on LMWH, 2 on DOACs, 2 on VKA, 2 on fondaparinux. The 2 patients with underlying diseases that received anticoagulant treatment, were on VKAs. Regarding antiplatelet treatment, 5 (41.7%) had initiated it after the thrombotic event ,3 (25%) prior, while 4 (33.3%) never received any. The antiplatelet treatment consisted of COX1 inhibitor in 4 patients and P2Y12 inhibitor in 1 patient for the 5patient subgroup. In the subgroup that initiated antiplatelet treatment after the first VOE, 2 received COX1 inhibitor and 1 P2Y12 inhibitor. In eight (66.7%), existing medical history could associate with thrombogenesis. Four (33.3%) had a history of splenectomy, 4 (33.3%) had functional asplenia confirmed by abdominal ultrasound or abdominal CT scan. In addition, 7 (58.3%) were regularly transfused with exchange transfusion. All 12 patients were receiving hydroxyurea throughout the observational period. (

Table 1)

6. Subpopulation with more than one thrombotic events

Five of 12 patients (41.7%) experienced more than one thrombotic episode. It is worth mentioning that all had one VOE in the same location as the initial one, while 4 (80%) had at least one episode elsewhere. One patient (20%) had a 2nd PE, 2 (40%) had a recurrence of DVT, 1 (20%) had two superficial thrombosis, and 2 (40%) had a second ischemic stroke.

Patient who had two episodes of PE also had two ischemic strokes. Two patients had the largest number of thrombotic events. The first one experienced 4 incidents, two episodes of PE and two ischemic strokes. The former experienced 3 episodes of DVT (therefore two recurrences) and 3 episodes of superficial thrombosis.

The subgroup with multiple thrombosis appears to have many common characteristics: a) all patients have the S/βMA double heterozygosity genotype b) they received a therapeutic dose of anticoagulant treatment after the first thrombosis episode c) the level of Hb was<11 and d) all received hydroxyurea.

This subgroup consisted of 3 women (60%) and 2 men (40%). Three (60%) received antiplatelet treatment after the first thrombotic episode while 2 (40%) did not. Two patients (40%) had undergone surgical splenectomy, 1 (20%) had functional asplenia and 2 (40%) had none of the above. Four (80%) were under exchange tranfusions programme. Four (80%) had normal platelet count while 1 (20%) had platelet number above normal. Three (60%) had an increased WBC count and 2 (20%) had normal. In this subpopulation, 4 (80%) had underlying diseases that could also explain the thrombosis. The mean baseline count for their laboratory values were: a) PLT: 308*103, b) WBC: 9,760, HbS: 47.4%, and HbF: 12%.

Regarding the timeline of the succeeding thrombotic episode, 4 had one within 5 years, while 1 had it within 20 years.

Discussion

Prevalence of VTE in the study population

The prevalence of thrombosis in our study was 26.1%, while the prevalence of VTE was 17.4%, consistent with the one described in literature (8-25%). At the same time, however, fairly high percentage compared to the 0,1-0,2% (1 in 1000) the annual incidence of VTE in the general population [

18,

19].

Keeping in mind only the first thrombotic events, there were identical rates of PE and DVT [33% (4/12) vs 33% (4/12)]. However, taking into account the 26 thrombotic episodes that the group of 12 patients experienced during the 25 years, it appears that DVT is more frequent than PE [30.8% (8/26) >23.1% (6/26)].

Characteristics and risk factors of the study population

Our study underlines that patients with SCD have a strong thrombophilic substrate. The first thrombotic episodes occur at a mean age of 38.1 years, a deviation of approximately 10 years compared to literature (mean age 29.9 years) [

20]. No difference was observed between the two sexes, but the first thrombotic episode was found predominantly in S/βMA heterozygosity (75%>25%). The corresponding deduction to 26 thrombotic episodes, reinforces the previous observation (23/26 - 88.5%> 3/26-11.5%).

Compared with large retrospective studies, it is deduced that administration of anticoagulant treatment and specifically its dose, show statistical significance both in univariate (both with p= 0.000) and in the various multivariate models (p= 0.000 and p= 0.001 respectively). This correlation however may not completely be objective as those who had thrombosis certainly received anticoagulant treatment and the majority received a therapeutic dose. What should be noted is that 7 (58.3%) received an anticoagulant dose after the first episode and did not relapse, and of the 5 who had more than one episode, 4 have concomitant diseases (2 have atrial fibrillation, 1 has arterial stenosis, 1 has incompetence of great saphenous vein, polpeteal and its perforating branches, poststenotic lesions in the entire lower limb) that could justify thrombosis (even in the first episode). Adding to this fact, the 5 patients receiving anticoagulant treatment systematically due to comorbidities did not experience any VOE.

There was a recurrence of VTE happened within a 5year window for 1 patient while 2 experienced recurrences within 10 years. This observation digresses from the literature where recurrences appear to be more frequent within a 5 year period. [

21,

22].

Although the age of the patient is deemed statistically significant, suggesting an increased rate of thrombosis as age increases, this observation is spurious. Examining only the subpopulation that experienced thrombosis (n=12) it is evident that thrombosis occurs more frequently in younger ages (20-39 years, 58.3%) and decreases progressively with age. This finding is confirmed by previous studies where the combination of thrombosis and SCD seems to have a tropism for younger ages [

23]. Also, the age-thrombosis analysis is not valid as it assumes the existence as a prerequisite.

A point of contradiction is that while the association of transfusion with thrombosis was not statistically significant, the relationship between the type of transfusion and thrombosis was (p= 0.018 (<0.05). As seen in the test group, 7/23 (30.4%) who were systematically transfused had thrombosis while 5/23 (21.7%) who were not transfused also had thrombosis. These percentages are not statistically significant as both their size and their deviation are not sufficient to reproduce statistical significance. On the contrary, when thrombosis was analyzed by type of transfusion, which includes the 23 patients who were transfused, the simultaneous presence of the following facts emerged as statistically significant: a) that exchange transfusion (15/23) has the same effect on thrombosis (7/15 who undergone exchange transfusion had thrombosis compared to 8/15 who did not), b) all patients who systematically received regular transfusions did not have thrombosis. These findings could be explained by the fact that exchange transfusion in our unit is performed manually, an issue that needs improvement in our country.

Finally, factors such as surgical splenectomy and homozygous sickle cell anemia did not show a statistically significant difference in contrast to current literature. This result may be a consequence of the insufficient sample size [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Characteristics of the subpopulation that experienced ≥ 1 thrombosis

Five (41.7%) experienced more than one episode in as early as a few months to as late as 17 years. The 1st VTE recurrence occurred within 5 years in 1 patient and within 10 years in 2, a result that is not consistent with the literature. While this sample is small enough to draw conclusions using statistical methods, it is worth noting the predominance of the S/βMA double heterozygosity genotype and the occurrence of multiple episodes at age ≤ 45 (10 out of 14 heterochronous thrombotic episodes).

Limitations

The present study is a retrospective observational study with data from the patients’ medical records. The number of patients which might be the reason for the lack of statistically significant correlations in many of the variables that have been found as such in the literature. Secondly, the absence of other genotypes of SCD seemed critical. In some cases, information collected regarding the patients’ concomitant diseases was the result of an interpretation of the therapeutic treatment they were receiving. At the same time, a few patients’ reason for administration of anticoagulant treatment was not known.

In variables such as functional asplenia, few patients had imaging tests around the occurrence of an the episode of thrombosis, so interpretations were based on the recorded clinical profile, the platelet count and the last ultrasound (regardless of dating). For the coexistence of PE and DVT that has been examined by various studies, there was no imaging test to document the positive or negative result. In 10 of 12 patients with thrombosis, there was no report on whether testing for hereditary thrombophilia was performed.

Another limitation of this study was if the date of splenectomy had preceded or followed the thrombotic episode was not known. Finally, it is not confirmed whether patients showed complete or relative compliance to their treatment.

Conclusions

There is a significant correlation between the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease and thrombosis, with VTE as the main representative. This interaction is complicated by the increased likelihood of recurrence of VTE. Recurrent VTE events as well as the first thrombotic event tend to manifest at a young age in various anatomical sites. Although the administration of anticoagulant treatment reduces the risk of recurrence of VTE and the occurrence of new thrombotic episodes, it does not eliminate it, nor does it remove the procoagulant mechanisms. Despite better understanding of the pathogenesis of the disease and the effectiveness of anticoagulant treatment, the innate complexity of the disease makes it difficult to lessen the likelihood of thrombosis which is associated with a broad spectrum of complications ranging from functional deficits to death.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration 115 of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hippokration Hospital of Thessaloniki, Greece. Protocol code 1420/9-1-2024

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACS |

Acute Chest Syndrome |

| AF |

Arial Fibrillation |

| DOAC |

Direct Oral Anticoagulant |

| DVT |

Deep Venous Thrombosis |

| Hb |

Hemoglobin |

| LMWH |

Low Molecular Weight Heparin |

| PE |

Pulmonary Embolism |

| RBC |

Red Blood Cell |

| SCA |

Sickle Cell Anaemia |

| SCD |

Sickle Cell Disease |

| VKA |

Vitamin K Antagonist |

| VOE |

Vasoocclusive Event |

| VTE |

Venous Thromboembolism |

References

- Uptodate.com. Available through subscription by typing Pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. Literature review current through: Oct 2024.

- Bender, MA. Sickle Cell Disease. GeneReviews 2003.

- Noubouossie, D. Coagulation abnormalities of sickle cell disease: Relationship with clinical outcomes and the effect of disease modifying therapies. Blood Rev 2016, 30, 245–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyadah, MS. Predisposing Factors and Incidence of Venous Thromboembolism among Hospitalized Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuker A, Altman JΚ. ASH-SAP, 8th ed., American Society of Hematology, Washington D.C., USA, 2022, pp 171-179.

- Varelas, C. Study of complement activation in adult patients with sickle cell disease. doctoral dissertation, Medical School of Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece, 2024.

- Ladis, V. HEMOGLOBOPATHIES: PATHOGENESIS-DIAGNOSIS-THERAPY, 1st ed., Beta Medical Publications, Athens, Greece, 2022, pp. 96-122.

- Stockman, JA. Occlusion of large cerebral vessels in sickle-cell anemia. N Engl J Med 1972, 287, 846–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J. Pathology of Sickle Cell Disease. Ann Intern Med 1971, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Kaul, DK. Microvascular sites and characteristics of sickle cell adhesion to vascular endothelium in shear flow conditions: pathophysiological implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989, 86, 3356–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipowsky, HH. Intravital microscopy of capillary hemodynamics in sickle cell disease. J Clin Invest 1987, 80, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, GP. Periodic microcirculatory flow in patients with sickle-cell disease. N Engl J Med 1984, 311, 1534–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embury, SH. In vivo blood flow abnormalities in the transgenic knockout sickle cell mouse. J Clin Invest 1999, 103, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rother, RP. The Clinical Sequelae of Intravascular Hemolysis and Extracellular Plasma Hemoglobin A Novel Mechanism of Human Disease. JAMA 2005, 293, 1653–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, GJ. Deconstructing sickle cell disease: Reappraisal of the role of hemolysis in the development of clinical subphenotypes. Blood Rev 2007, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, GJ. Sickle Cell Disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataga, KI. Beta-thalassaemia and sickle cell anaemia as paradigms of hypercoagulability Br J Haematol 2007, 139, 3-13.

- Ziyadah, MS. Predisposing Factors and Incidence of Venous Thromboembolism among Hospitalized Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearon, C. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Semin Vasc Med 2001, 1, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piel, FB. Sickle cell disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1561–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpato, Β. Risk factors for Venous Thromboembolism and clinical outcomes in adults with sickle cell disease. Thromb Update 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunson A. High incidence of venous thromboembolism recurrence in patients with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2019, 94, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, RP. Sickle cell disease and venous thromboembolism: what the anticoagulation expert needs to know. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2013, 35, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conran, N. Thromboinflammatory mechanisms in sickle cell disease - challenging the hemostatic balance. Haematologica 2020, 105, 2380–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, TT. Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism in Adults with Hemoglobin SC or Sβ+ thalassemia Genotypes. Thromb Res 2016, 141, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, RC. Patients with Sickle Cell Disease and Venous Thromboembolism Experience Increased Frequency of Vasoocclusive Events. Blood 2019, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shet, AS. How I diagnose and treat venous thromboembolism in sickle cell disease. Blood 2018, 132, 1761–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).