1. Introduction

In what we call the knowledge society, continuing education and sustainable development at the local, regional, organizational, and global levels have become veritable “vectors” for economic behavior at the individual and social group levels.

Starting with the Humboldt University model (1820) and continuing to the present day, university education and the acquisition of new knowledge have directly promoted technical and social innovation as the foundation for economic growth at the company and/or country level. In today's society, Drucker argues [

1] (pp. 264–265) that the most important investments are those made in education/knowledge, both at the individual and country level, as the most sophisticated technologies remain unproductive in the absence of skilled employees. Over the last three decades, the concept of lifelong learning (LLL) has become accepted and applied in most organizations in the world's major countries, including China, India, Brazil, and Mexico.

In this post-capitalist society, new challenges constantly arise for individuals, organizations, and countries, among which sustainable development and/or the shift toward a green economy stand out as particularly important. This shift toward sustainability has been enshrined internationally in the 17 goals agreed upon by the world's leading countries in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

2]. Some major social/political crises, such as COVID-19 (2020) and, more recently, the war in Ukraine (2022), have forced some countries to redefine their proposed objectives, but the vast majority remain committed to implementing the SDGs. The uncertain position of the US regarding its membership in the Paris Agreement poses difficulties for EU member states in other countries concerning the timetable assumed under the SDGs (the US is no longer a signatory, but continues to apply this framework for sustainable development). Finally, the recent trade war between the poles of the economic triad (US-China, US-EU) brings some additional difficulties regarding the strategies/practices that should be applied by companies to achieve the Green Economy. However, as we will show in the analysis of the 50 companies in the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) study, most innovative companies are already moving towards fulfilling commitments made under the SDGs and other UN programmes.

Fundamental to the orientation of organizations and/or countries towards sustainable development, innovation, and new knowledge is the extent to which national cultural values vs. organizational cultural values evolve through the education of new generations of employees and all LLL and training activities.

The study on the competitive advantage of Porter [

3] developed as the most authoritative and well-argued discussion of the factors that drive the competitive position of countries/industries in the global economy. However, Porter's study does not provide ample insight into the development of core competencies/capabilities by certain MNCs; furthermore, it seems that "international/global born companies" that sometimes attain successful positions in international markets [

3] diverge from Porter's criteria for competitive advantage. In the future, Drucker argues, there will be no “poor countries,” only “ignorant countries.” The same can be said of companies, institutions, and individuals [

1] (p. 261). One of the most dynamic areas of management, namely Knowledge Management, emerged in the 1960s with the publication of Polanyi's work [

4]; this topic has become essential for all innovative companies, but also for universities, journals, publishers, and other instruments for promoting knowledge at the social level. The distinction between “explicit knowledge” (that found in databases, books, manuals, etc.) and “tacit knowledge” (intuitive, non-quantifiable, informal, derived from experience, etc.) still raises many dilemmas in trying to understand how innovative companies and/or countries operate and how such entities have managed to hold top positions in various international rankings over the last two or three decades.

The basic idea of this study is to analyze informally and cross-referentially the values of culture at the level of innovative companies (based on BCG and other similar rankings) in relation to the values and evolution of national cultures in the countries where such companies are based, as well as in countries where they have various specific operations (based on LPI and other similar rankings). In this sense, we will distribute the analysis as evenly as possible in terms of identifying strategies/practices at the company and country level simultaneously, with regard to innovation and orientation towards SDGs.

With regard to the concept of “national culture” there are over 160 definitions formulated by various authors [

5], [

6] however, no consensus has been reached on the factors/dimensions that give substance to the concept of culture. On this subject, the best-known and most widely accepted international study remains that of Geert Hofstede [

5], [

6], which identified six cultural dimensions, issues that are already well known (distance from power, individualism-collectivism, etc.). In Hofstede's view, values are the core factor that determines the evolution of a national culture towards better or worse economic behavior of individuals (by values we mean the distinction between good-evil, true-false, correct-incorrect, etc.). The GLOBE project confirms the dimensions identified by Hofstede and examines in depth the relationship among national culture, organizational culture, and management practices in business organizations in order to determine the most effective type of leadership in 25 major countries of the world [

7], [

8] (pp.7-9).

A concept similar to that of national culture is that of social capital, which was established internationally by Putnam [

9] and Fukuyama [

10]. In this case, trust and high sociability are the factors that show us the core elements of social capital, so it is still about certain values that individuals and social groups refer to in order to be more successful in economic activity. Finally, authors such as Daft [

11], [

12] argue that a set of key values (good-evil, true-false, ethical-non-ethical etc.) are central elements in the culture of relatively successful business organizations that gain a competitive advantage.

In order to achieve the proposed research objective, we need to expand on the brief description of some aspects in this introductory section (we will return to this briefly in the Literature Review section). In the same vein, the Research Methodology section (point 3) and the following two sections, in which we present the working method for international rankings for companies, and countries, respectively, provide a relatively more complete picture of the dual influence of corporate values versus national values, in order to then identify the directions in which companies and countries should act for innovation and sustainable development.

2. Literature Review

The SDGs Report 2024 highlights, among other things, aspects that are directly related to some of our research areas. It starts from the premise that the new generations of employees will want to pursue a career and live in peace, with access to education and the best possible standard of living [

13]. As we will show in the results of our study, the last two decades have seen a veritable “clash of cultures” between corporate values and national values [

14]. The same document states that countries, companies, and other institutions should cooperate in science, technology, and innovation to provide future generations with relatively equal opportunities for economic growth and sustainable development [

15]. In a relatively recent work, authors Acemoglu and Robinson show that most of the world's poorer countries fail not because of geography or other similar factors, but because they fail to build political/social institutions that support prosperity for millions of people [

16] (pp. 409-447). In other words, social values such as education, orientation towards the common good, work ethic, etc. were essential for development around 1900, when Weber published his main work [

17]. According to Weber, modern capitalism was based on moderation, perseverance, education, work ethic, etc. [

18] (pp. 50-54), their promotion in the behavior of social groups was based mainly on political institutions and social norms imposed by law..

From the perspective of more recent developments in the global economy, namely after 2000, the issue of the values that individuals, organizations, and countries believe in remains just as relevant. In a well-argued study on the role of KM in “Society 5”[

19], the authors show that the integration between people, nature, economy, and technology must be based on the sustainable development of social groups and the achievement of SDG objectives. Therefore, KM has become essential in relation to sustainable development at all possible levels of analysis, namely individuals, families, organizations, and countries. With reference to the social capital described above, Fukuyama shows that each of us understands that the distinction between good and evil is only between individuals who have character and assume such a distinction in extreme situations [

10] (p.23). Certain well-known values such as trust, reciprocity, spontaneous sociability, along with social institutions created to ensure fair competition, explain to a large extent why some countries fail to achieve economic development [

10] (pp.22-31).

Some studies conducted by sociologists concerning social capital in the case of Japan, South Korea, and other Asian countries [

20] reflect precisely the fact that in the social climate of these countries, there is a type of trust that is not covered by international surveys (in fact, even according to LPI, these two countries score very well on pillars such as education, health, living conditions, personal freedom, etc.). This explanation, at least in part, of our view of social capital assessment concerning the evaluation of a country's competitive position is given by what some sociologists call systemic trust, which differs from interpersonal trust or institutional trust[

21], [

22]. By systemic trust, we mean the trust that members of a large social group put in social systems such as a country's economy, the global economy, the development of a major company, etc. Other sociologists, such as Shamir and Lapidot [

23] consider that systemic trust is also found in the functioning of smaller socio-economic entities/systems, such as medium-sized firms in the SME sector of the global economy. Systemic trust refers to the trust a social group builds in the performance and survival of any hierarchically organized and autonomously functioning social system.

To better understand the essence of knowledge acquisition processes, continuous innovation, achieving synergy in team management, and other similar aspects, it is useful to briefly explain the concept of core competence, which provides us with a broader picture of the competitive advantage described by Porter [

24] and mentioned by us earlier. The concept of core competencies proposed by Prahalad and Hamel [

25] gives us a closer picture of the realities of the global economy from the 1990s to the present. Essentially, by core competence, we understand those activities, processes, or operations that perform better or more efficiently/effectively than competitors, whether these activities relate to the overall vision, organization chart, product design etc. A related concept to core competence is that of "dynamic capabilities". According to the two authors, "collective learning" at the group/team level gives a firm's core competence to achieve better skills and knowledge than other firms in product design, manufacture, or distribution [

26]. For now, we emphasize the idea that obtaining core competence is directly conditioned by “collective learning,” which means LLL activities, education, and continuous training for innovation. In the same vein, LLL activities start at the individual level and continue at the group/team level, as well as across an organization as a whole [

27]. Through such activities, employees/members of an organization accumulate new explicit and tacit knowledge, which is essential for performing well in a particular position/job and for voluntarily directing behavior towards sustainable development [

28]. Therefore, our arguments show that the initial education of a generation of employees and the positive values imposed by social norms remain the major factors explaining the performance of hierarchically organized social groups. The previous statement remains valid when we refer to continuous innovation at the company level, the development and achievement of SDG objectives at the organizational and country levels.

At the level of MNCs or SMEs, LLL activities, the acquisition of new knowledge, and continuous innovation are combined with the use of various digital technologies and contribute directly to the orientation of organizations towards sustainable development. However, we do not know precisely how some employees in the most innovative companies manage to gradually acquire a greater volume of tacit knowledge and, in this way, become human experts in certain professions, industries, or sectors of activity. Some studies show that companies need to develop corporate cultures that support sustainable innovation, which would also mean “sustainable knowledge-sharing.”[

29], [

30], [

31]. Digitization and certain cultural/social norms imposed by the state can support the performance and orientation of companies towards SDGs [

32], [

33]. This essentially means simultaneously guiding individuals and social groups, through education, towards positive values that are connected to the common goal pursued by organizations/countries.

The tacit knowledge we referred to earlier, together with the values believed in by the members of a group/team, have become essential resources for continuous innovation in companies, but also factors that directly support sustainable development at various levels of analysis according to Ambrosini & Bowman [

34], Chen [

35], Coombs [

36], Zhi [

37], and also other authors such as Barney [

38] and Pukenis [

39], Turan [

40]. In what we call “Society 5” or “Knowledge Society,” employees must upgrade their knowledge every 5-10 years, argues Drucker [

1] (p.275). In the field of Knowledge Management (KM), we discuss tacit knowledge at both the societal and organizational/individual levels; however, we lack understanding of how organizational realities intersect with national ones, or how tacit knowledge integrates with explicit knowledge. Starting with Polanyi[

4], other authors such as Abeysekera[

4], Busch [

41], McAdam[

42], Nonaka[

43], Nonaka and Takeuchi[

44], Polanyi[

45], Shihabeldeen [

46] and Smith[

47] etc. argued that approximately 80-90% of all knowledge in society is tacit knowledge. This proportion of tacit knowledge in total human knowledge explains/justifies the major interest in understanding the acquisition, processing, sharing, and valorization of tacit knowledge, all of this together with a volume of explicit knowledge in the direction of continuous innovation and sustainable development.

At the societal level, we distinguish between three classes/categories of tacit knowledge, namely: RTK (Relational Tacit Knowledge), CTK (Collective Tacit Knowledge), and STK (Somatic Tacit Knowledge) [

48], [

49]. At the organizational level, there are four types of tacit knowledge: Organizational Routines, Know-how, Mental Models, Way of Solving [

50], [

51].

To explain the conversion/transformation from explicit knowledge to tacit knowledge, the most well-argued concept remains the opinion of Nonaka and his collaborators, who imposed the SECI (Socialization, Externalization, Combination, Internalization) model at the international level [

41]. For the application of SECI by companies, the concept of Ba suggests certain directions in which managers/companies should act in order to achieve continuous innovation in the context of sustainable development. Essentially, the Ba concept represents a dynamic context, given by a physical or virtual space, in which the members of a group/team interact permanently to achieve a certain goal; therefore, it is a shared and dynamic context in which new knowledge is created and the conversion from explicit to tacit and vice versa is achieved[

45] (pp.34-38)[

52](pp.13-29). It follows that, in order to effectively apply the Ba concept and implement the SECI model (which ensures the synergy effect of a team), the people involved must willingly accept the achievement of a goal/objective that is in line with several key values believed in by each member of the team/group.

Moreover, KM and the values that managers believe in have now become essential for continuous innovation and SDGs in the various contexts in which firms may operate, i.e., "open innovation", "clusters", "innovation networks" [

53], [

54], [

55], [

56]. Therefore, the innovative capacity and sustainable development of firms are conditioned not only by technologies but also by the fluctuation of existing values in society, by the stock of knowledge existing at a given time, and by the strategies designed by top management to apply KM [

57] as well as by other factors.

Both in social contexts and at the level of groups/organizations, the three types of tacit knowledge in society are constantly combined with the four types of tacit knowledge in organizations. The above statement applies to all individuals who are placed in a position to interact with each other and transfer their expertise to others, which requires face-to-face contact and a trust-based climate [

58](p. 151) between the transmitter and receiver. A trust-based context between transmitter and receiver requires, at the same time, some shared values, compatible relationships among members, and the belief that all others involved are motivated by a shared, positive, and socially beneficial goal [

59](pp. 99–187). Fair competition, enforced social norms, and especially those created spontaneously [

10] ( pp. 45–49) explain to a large extent (but not totally) how systemic trust is nurtured in successful MNCs and/or developed countries. Therefore, specific dilemmas, uncertainties, hopes, fears, emotions, etc., of the rational individual, which were valid a century ago, are entirely found in today's global society; such aspects are highlighted in various studies[

60] and cannot be embedded in any mathematical model that aims to capture the economic behavior of social groups.

3. Research Methodology

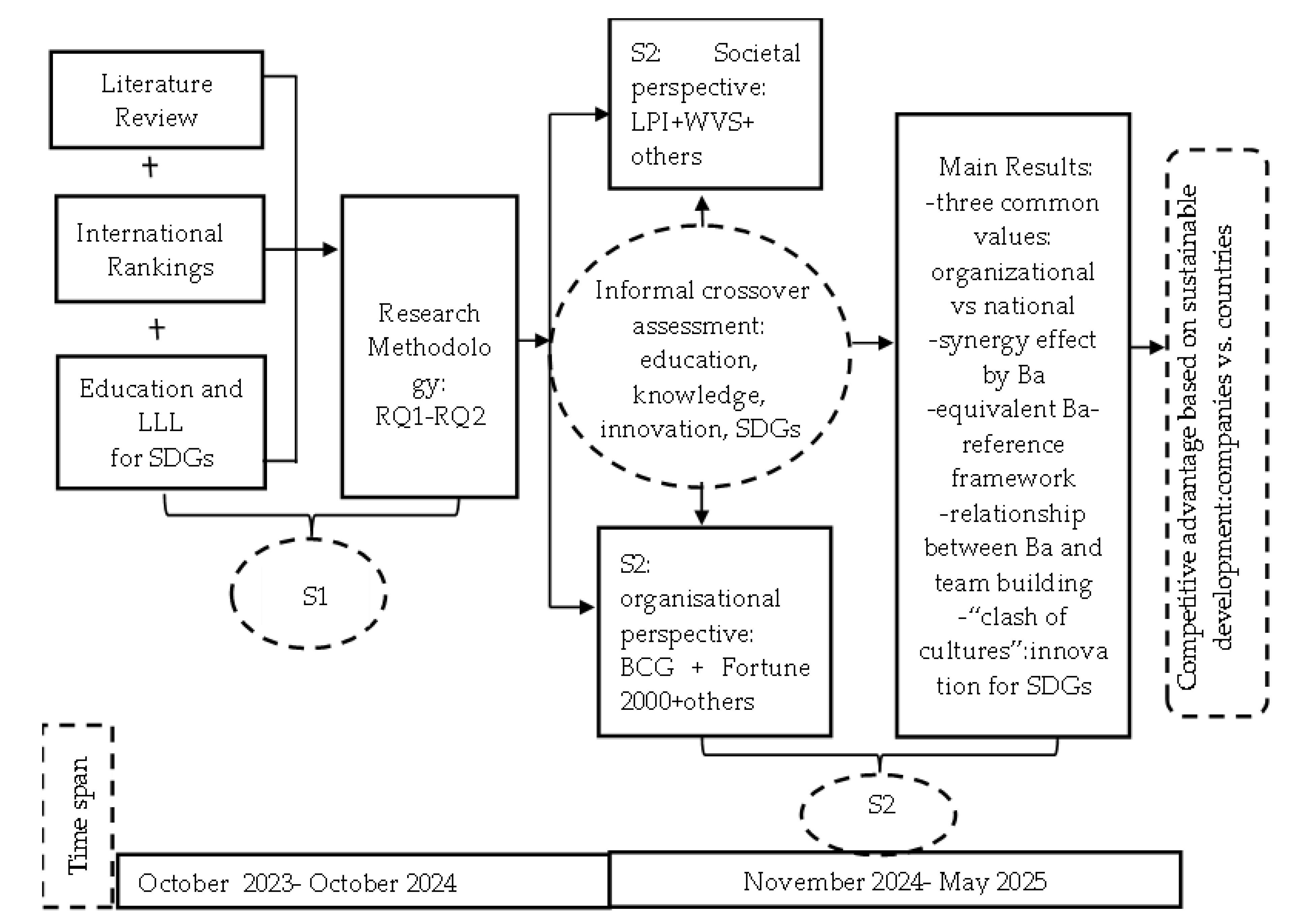

This study essentially went through two main stages:

S1: In the first stage (October 2023-October 2024), we analyzed the international literature on the proposed research topic and selected five international rankings for MNCs known for their innovative capacity and focus on sustainable development, along with five international rankings for the world's leading countries. In summary, we selected over 100 articles based on keywords from WOS, Scopus, etc., of which we used around 60 articles as references in the text and at the end; in addition, there are over 50 volumes/manuals studied by authors in the last two decades [

59], [

61]. At the same stage, we selected LPI as the main ranking that shows us a country's prosperity, along with four other rankings that show us the situation regarding education and other key indicators. The 28 countries were selected based on GDP per capita and other criteria such as the number of internationally known MNCs, focus on sustainable development, etc. At the end of this stage, we outlined the Research Methodology and two research questions, RQ1 and RQ2.

S2: In the second stage of the research (November 2024-May 2025), we conducted an informal and cross-sectional analysis between organizational and societal factors based on information other than the mentioned rankings, focusing on certain factors such as education, knowledge, innovation, and SDGs.

Based on the proposed study, we formulated the following two research questions:

RQ1: To what extent are there or are there not several key values that are simultaneously found in corporate culture vs. national culture for entities that are innovative and aim for sustainable development?

RQ2: What are the key values that most support the achievement of synergy in innovative and sustainable companies?

Based on the proposed Literature Review and Research Methodology, we have developed a flowchart of the entire study, which clearly shows the basic idea of the study, the argumentation constructed, and the results reached by the authors.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study. Source: elaborated by the authors.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study. Source: elaborated by the authors.

4. Organizational level: BCG vs. Forbes vs. MTC vs. MSC vs. FTSE

The BCG ranking shows us the 50 most innovative companies in the world and offers a rather surprising picture of the last few decades in terms of international competition, number of patents, etc. From the 50 companies in the BCG ranking, we selected the top 22 companies for which we then identified four other rankings that, together, provide a comprehensive image of the values/organizational culture and orientation of these entities towards sustainable development. As shown in

Appendix A of the study, the analysis period was 2023 vs. 2010, and alongside BCG, the other rankings show us:

- Forbes - Most Reputable Companies- Companies with the best public image and reputation;

- MTC - Most Trustworthy Companies- Firms ranked high in honesty and reliability;

- MSC - Most Sustainable Corporation- Companies excelling in environmental and social responsibility;

- FTSE- Most Sustainable Corporation- Corporations ranked for top ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) performance.

In order to gain a more comprehensive picture of these companies' vision, KM strategies, and how they proceed to remain in the BCG study each year, if possible, we have included other key indicators for each company (number of employees, turnover, market capitalization, average number of patents during the period analyzed, and values declared by each in their Annual Reports).

As shown in

Appendix A of the study, the vast majority of BCG companies declare in their Annual Reports a limited number of key values of organizational culture, among which we frequently find: “trust,” “knowledge,” “employee training,” “sustainable development,” “continuous innovation,” etc. One of the basic ideas of our study is to analyze, at least deductively, the relationships/connections that can be glimpsed between such key values at the organizational level vs. essential/core values that can be identified at the country/nation level. In other words, we aim to identify the dual influence of cultural values from the organizational to the societal level, and vice versa, in order to suggest directions for continuous innovation and sustainable development for any hierarchically organized social group.

In a previous study, we analyzed in depth the relationship between the data/information provided by BCG vs. the information provided by GCI [

62], however, we concluded that the hypothesis of applying statistical tests should be excluded, as it leads to a result that is not logically sound. In fact, authors such as Krugman argue that “a country is not a company” because we are dealing with very different socio-economic systems.[

63]. In this study, we have greatly expanded the scope of analysis on the same value relationship between organizational and national levels and included other rankings for both levels of analysis that can provide us with a more complete picture of the dual influence on the key values that underpin the economic behavior of any hierarchically organized social group. However, the analysis we propose remains informal and descriptive.

In the last column of

Appendix A, we include a brief description of the values that can be identified at the corporate level vs. national culture, relating this summary to the four dimensions of organizational culture according to Cameron and Quinn [64, pp. 38–51]. The four dimensions of organizational culture (Clan-Collaborate, Adhocracy-Create, Hierarchy-Control, Market-Compete) provide a useful analytical framework for framing the values declared in the 22 MNCs we studied (out of a total of 50 companies included in the study) in terms of organizational vs. national cultural dynamics. However, it should be noted that only the “market-compete” dimension of culture is found in most of the 22 companies we studied; in addition, each high-performing company changes its cultural dimensions considered to be priorities relatively quickly over time. This essentially means that there is a relatively pronounced dynamic with regard to organizational culture values. Subsequently, some of the Main Results we arrive at, such as subsections 6.2, 6.3, and 6.4, will be based on this comparative analysis.

The summary analysis of the 22 MNCs in

Appendix A, as well as the total of 50 in the BCG study, allows us to formulate some unified assessments/evaluations related to the basic idea of our study. Firstly, we emphasize that the vast majority of companies in the BCG study are American, with a small number from Europe, and in recent years a significant number of companies considered innovative from Japan, South Korea, and China have also been included. More recently, even the Saudi Arabian company Aramco is among the 50 companies in the BCG study. In other words, even companies from countries with autocratic political systems (China, Saudi Arabia, etc.) have met the criteria necessary to be considered innovative. Therefore, there is no conditioning, at least theoretically, between the cultural specificity of a country and/or its political system in relation to the cultural specificity of a company that may aim for continuous innovation and sustainable development. Secondly, among the 22 companies we studied, we find some companies (Apple, Tesla, Bosch, Sony, etc.) that explicitly refer to sustainability, the environment, innovation, or trust in their annual reports. Also in this sense, some companies (Apple, IBM, Ford, Intel, Samsung, etc.) have very good indicators for innovation, profit, or market capitalization and a much more modest position on “performance sustainability” and “investment sustainability.

5. Societal level: LPI vs. GKI vs. GSCI vs. WCY

At the societal level, alongside the LPI, which is considered the main ranking (it shows us the level of prosperity for almost 200 countries around the world—calculated annually), we have added the following four international rankings for all 28 countries, as shown in

Appendix B to the study:

-GKI- Global Knowledge Index- Measures countries' knowledge-based development and readiness;

-GSCI-The Global Sustainable Competitiveness Index- Ranks nations on sustainability-driven competitiveness;

-WCI- The World Competitiveness Yearbook- Assesses countries' economic competitiveness;

-WVS- World Value Survey- Surveys global beliefs, values, and cultural changes.

As far as we had the necessary information, the analysis period was also 2023, relative to 2010 (where applicable: WWS is calculated in waves, and we included information from the last two publicly available waves). In

Appendix B, we calculated the average scores for the first four rankings and included the GDP per capita value for the 28 countries selected for the study (the countries are ranked according to the average scores).

Since one of the main areas of analysis was the potential role of education in several areas of modern society's development, in

Appendix C, we have included separately and distinctly for each country, under the existing pillars in the rankings, which show us: Education, Higher education, Intellectual Capital, and trust in universities rankings (the countries are listed in alphabetical order).

A summary analysis of the information provided in

Appendix B and C as a cumulative assessment leads us to several ideas/conclusions that support our research approach. First, it can be inferred that the size of a country's population does not in any way determine its level of prosperity, GDP per capita, or orientation toward sustainable development. However, it is worth mentioning that in the case of smaller countries (Austria, Singapore, etc.), it is rarer to find a significant number of corporations in the BCG study or other international rankings on sustainable development (see

Appendix A). Secondly, it can be deduced that the average of the four rankings calculated by us correlates closely, but not entirely, with the GDP per capita achieved by the countries included in the study. However, there are numerous exceptions in both directions, with some countries (Taiwan, Austria, South Korea, etc.) recording a slightly more modest GDP per capita but holding a significant position in the four international rankings. Other countries (the US, Singapore, Japan, France, etc.) have a higher nominal GDP per capita, but rank somewhat lower in terms of the average of the four rankings. There are some current studies[

65] which identifies, based on descriptive statistics, a relationship between two of Hofstede's dimensions (individualism vs. collectivism) and the country's orientation towards “green innovation”. Other studies[

31], [

66] connect cultural values, knowledge sharing, continuous innovation, and sustainable development at the company/country level a bit better, but it's about knowledge in general (tacit and explicit). Unlike other studies, in our case we focus almost exclusively on tacit knowledge (acquisition, sharing, valorization processes, etc.) as these have become essential as an unlimited resource for innovation and sustainable development at the company/country level. With regard to other cultural dimensions identified by Hofstede and the orientation of countries towards SDGs and continuous innovation, we do not have significant studies, especially when it is considered that explicit knowledge is available to everyone in the Internet age. The GLOBE studies mentioned above[

7], [

8] provides useful information on the type of leadership that would lead to business performance and suggests some values that managers and countries should aspire to. However, this study does not highlight the underlying factors, i.e. the key values that would explain continuous innovation and sustainable development simultaneously at company and country level. Thirdly, the information in

Appendix B and C shows us that major changes occur over a decade or more in the position occupied by countries in each of the four rankings and, more importantly, shows us that trust as a value in itself fluctuates relatively quickly at the societal level (regardless of whether we are talking about interpersonal trust, institutional trust, systemic trust, etc.). Therefore, we identify that there is a dynamic of national cultures that is somewhat slower than that of organizations and that the cultural specificity of one country or another is actually determined by the dynamics of values such as education, trust, and new knowledge[

14].

Finally, other aspects that can be deduced from the cross-analysis of the information provided in

Appendix B and C vs.

Appendix A, and vice versa, are reserved by us for the next two sections of the study.

6. Main Results. Discussions

6.1. Education and Values in Knowledge Society

In what we call the Knowledge Society, education and lifelong learning (LLL) have become two essential vectors for everything that involves the acquisition of new knowledge, continuous innovation at the level of companies and countries, and sustainable development at the level of individuals, families, social groups, and countries. The knowledge society, says Drucker [

1] (pp.250-256), must have at its core the concept of the “educated person”; this society will be much more competitive than all the social systems that existed in the last century. In such a society, however, the values to which the new generations of employees relate are changing extremely rapidly, in the sense of moving towards more individualistic values (power, money, affirmation, etc.), while community values such as moderation, balance, sustainability, etc. remain secondary)[

14]. Therefore, it is necessary to identify a balance between the objectives pursued by individuals, corporations, and countries so that a balance can be achieved over time with regard to the values believed in by employees, various organizations, and political decision-makers at the country level.

In

Appendix C, we presented education as a sub-pillar of the LPI, and the data derived from this ranking shows that the position of the 28 countries we studied fluctuated significantly between 2010 and 2023. In the case of some countries (e.g. Argentina, India, Indonesia, Portugal, the Philippines, etc.), it appears that they have recorded a much more modest position in terms of education in 2023 compared to 2010; this assertion is also supported by their scores in the GKI and GSCI rankings for the education component (higher education, intellectual capital) in 2023. In the case of other countries (Denmark, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Singapore, Russia, etc.), they maintain/significantly improve their position in terms of education in 2023 vs. 2010; their position correlates only partially with the other rankings mentioned (GKI, GSCI). Finally, in the case of other countries among the 22 we studied, which had a relatively good position in 2010 and a relatively high GDP/capita (e.g., the US, Spain, Canada, Austria, etc.), they maintain their position in terms of GDP/capita, but achieve a somewhat more modest position in terms of education as a sub-pillar of the LPI in 2023.

Therefore, we arrive at an important idea for the argumentation constructed in our study, namely that the public policies applied by the world's leading countries regarding education play an essential role in several plans/directions in order to build high-performing economic behavior over time. Such public policies on education are the main factor supporting future generations of employees in accumulating explicit knowledge and, to a certain extent, tacit knowledge in order to simultaneously adapt their behavior towards creativity, innovation, and sustainable development. Subsequently, education policies in various countries can directly support the strategies applied by various organizations for what we call “organizational learning” and/or LLL, namely training and continuous qualification of employees to acquire new knowledge and understand/accept how important “sustainable innovation” has become in the context of the 17 goals targeted by the SDGs. It can be said that competitive advantage, at any level of analysis (countries and/or companies), can no longer be conceived today except in the context of the integration of each entity within the framework provided by the SDGs. Simply put, education is what shows us, first and foremost, whether and to what extent individuals and families today understand the importance of framing their behavior within the conditions set by the SDGs.

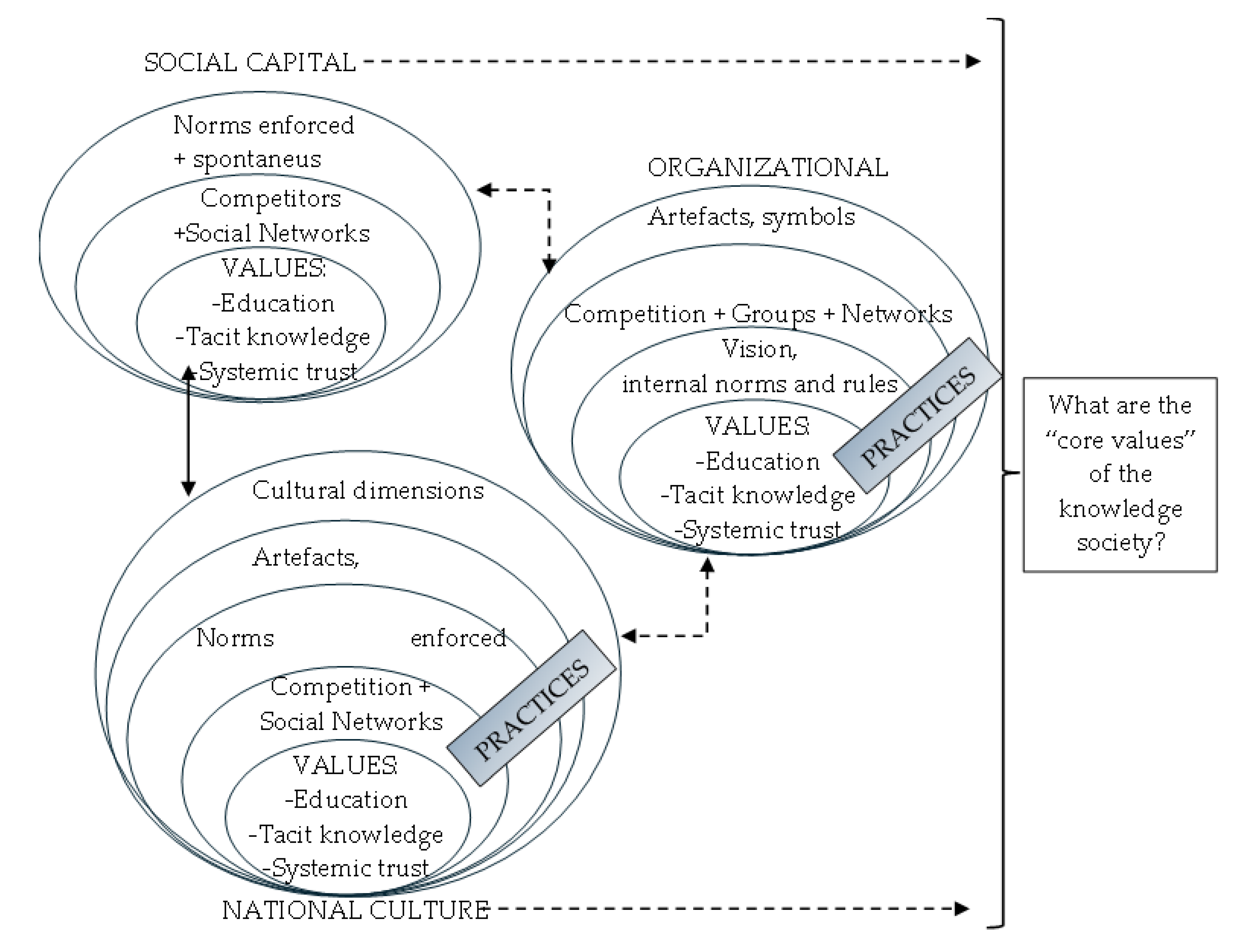

In

Figure 2, we present the equivalence that can be drawn between national culture and social capital on the one hand and organizational culture on the other hand. At the core of the national culture of a large social group are the fundamental values and Hofstede's [

5] view of other layers of the diagram. At the heart of social capital, we enclose, as a necessary equivalent, a set of two values: tacit knowledge and systemic trust. As far as the multi-layer diagram of organizational culture is concerned, it is consistent with earlier similar views on this topic found in management textbooks [

12].

The dominance of Japanese MNCs since the 1960s, followed by the emergence of several latecomers in the global economy, particularly of Chinese companies after 2000, suggests a decoupling/breakdown of national and organizational culture. What is, in fact, the reality? As we have portrayed in

Figure 2, at the heart of organizational culture are three key values (education, and informally named knowledge and trust, from which tacit knowledge and systemic trust are derived), which have become key resources for any company aiming to integrate KM into its culture. Various studies emphasize the role of trust and climate as a value that is embedded between team members for the application of KM, horizontal and vertical knowledge transfer in the organizational chart of firms focusing on continuous innovation to achieve core competencies [

53], [

67], [

68].

This is even though it is easy to deduce from various studies on the subject (according to well-known authors such as Weber [

17],Padua [

69], Fukuyama [

10] (pp. 25-27) etc., plus others who have different studies on the subject [

21] that whatever these core values are, they may shift significantly over time.

The second layer of organizational culture in

Figure 2 is related to "vision, internal norms, and rules" as an equivalent for what is meant by "enforced and spontaneous norms" in the case of "social capital". We believe there is no "recipe," although numerous studies/articles on this subject [

10] (27-33), [

70], [

71], [

72], [

73], [

74] regarding fostering a trust-based climate. According to Herreros (2004), the essence of social capital is rooted in the mutuality between two people, a relationship derived from trust; the social context based on trust becomes a resource in various social networks. At the level of firms and other organizations [

75], information and power distribution asymmetry make it challenging to build a trust-based climate.

The role of culture in modern society is usually developed from a macro-social perspective concerning the individual perspective [

7], [

76], [

77]. Religion has historically been a distinct value and/or a source of value for Western civilization [

78]; it reveals a spiritual dimension as a subset of social capital; the same spiritual dimension is given by Confucianism for the civilization of the East [

79], regarding China and other Asian countries. This is because both subsets of social capital advise the individual to accept and respect the obligation of trust-derived reciprocity [

79].

6.2. Crossover Analysis: Organizational vs. Societal

The topics we have reserved for this section of the study include a cross-analysis from the organizational to the societal level, and vice versa, with the intention of deducing/understanding the underlying factors, namely a set of key values and/or behavioral norms that are simultaneously found at both levels of analysis in the case of companies/countries considered innovative and directly engaged in achieving the SDGs. To identify such values and/or behavioral norms, we rely mainly on those already synthesized by us based on the information in

Appendix A, as well as the information accumulated in

Appendix B and C. We believe that theorists should explain in more detail the factors that lead to competitive advantages for companies and countries simultaneously, as the simple assertion of “acquisition of new knowledge” along with similar ones such as “knowledge sharing” only provide a summary picture of how the realities of innovative companies are linked to the realities of countries in the top positions in terms of GDP/capita, LPI, or other similar rankings. This is because everything we call “explicit knowledge” spreads extremely quickly in the Internet age to most countries and business organizations. As we will see, this study argues that a more profound factor explaining the acquisition of core competence by companies is leadership applied at the level of teams/groups/departments with regard to achieving synergy based on the SECI model, understanding the concept of Ba, the reference framework, etc.

Typically, as Drucker reasons, any business organization adheres to a set of values that should be congruent with the values to which the organization's members commit themselves; they need not necessarily be identical, but they must be close enough to ensure a common, intended and long-term goal [

1] (pp. 190–193). Without the shared goal that the firm and its members embrace, there is very little chance that a firm will be able to craft an organizational culture that supports top performance in the industry and/or market in which it operates [

80].

Certain social practices and norms governing the economic behavior of groups/entities can be replicated/copied by other competitors. Countless examples can be provided to substantiate our prior assertions [

81]. According to Avram si Zalabak [

82] (pp.32-38; 61-84) “organizational trust” has become the bedrock for all that individual and/or organizational excellence means in modern society. There is no clarification in the KM literature on which type of trust (interpersonal, institutional systemic, etc.) is more important in unifying the efforts of "n" members and transforming the group into an effective team.

According to Girard [

83] there are different views in the literature on the extent to which we should consider a firm to have or not to have organizational memory. In our interpretation, every firm has such a memory, which is made up of explicit knowledge (norms, rules, codes, annual reports, etc.) and specific tacit knowledge that is different in importance, impact, and relevance from what we have called organizational routines. As a related topic with KM applied by the firm, the organizational memory should include some principles/practices that have played a key role in the company's evolution, have been preserved in the collective memory, and passed on from one generation of managers to another. Theoretically, if a company has organizational memory, we must find a “memory” at the team/group level. Along with the other companies selected by us in

Appendix A, we invoke a small sequence from Toyota's history on what it means organizational memory (namely the 4 Ps on which Toyota's philosophy has been based over seven decades; the Toyota Way has become a “vector” for all executives from the 1950s to the present [

84]. It is challenging to characterize/measure the quality of tacit knowledge that a group/collectivity owns. Some authors like Erden [

85] propose a four-level model to explain the tacit knowledge quality of any social group (level 1: Group as Assemblages; level 2: Collective Action; level 3: Phronesis; level 4: Collective Improvisation). In this hypothesis analysis [

85], the evaluation of the tacit knowledge quality of a group necessarily leads the discussion toward concepts such as "collective mind", "collective body", "collective intuition", "collective improvisation," or "collective memory" (on which sociology, psychology and other disciplines do not offer unified clarifications). Authors such as Argote [

86] shows that more research is needed to understand how "embedding knowledge" is formed in organizational memory based on rules, routines, culture and structure.

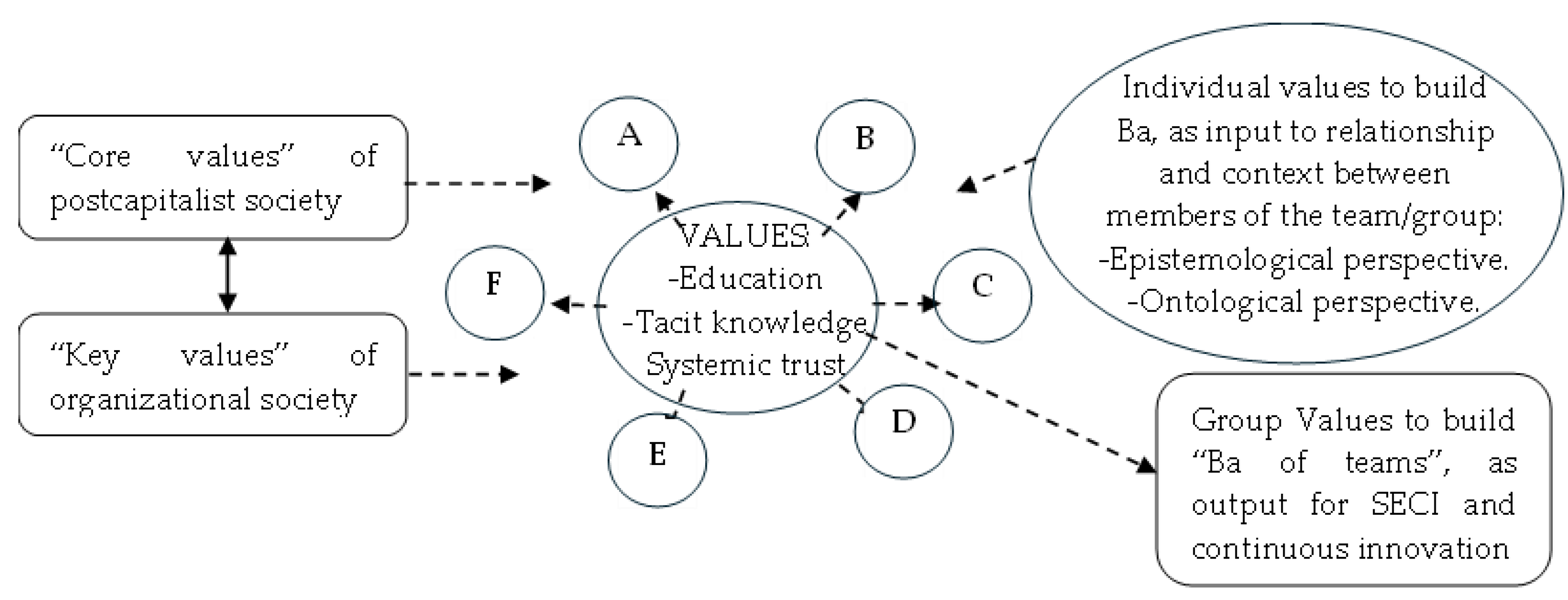

In

Figure 3, we present the appeal to values as an integrative framework, i.e., a type of catalyst for the effort of a six-member team (A, B, C, D, E, and F) in all situations where it is necessary to transform tacit to explicit and vice versa. In other words, the two values mentioned are essential to building an organizational culture that supports groups/teams, departments, and the company in all firms' innovative activities.

As shown in the figure above, specific core values at the societal level and key values within the organizational culture will exert a permanent influence on the establishment of formal groups and/or teams within a firm, on the purpose of the group, and the values around which the group/team gradually improves its performance.

Building effective KM teams for innovation and SDGs requires a common vision stated by the CEO and shared by others that supports LO [

27], clear internal rules, fair competition, minimal hierarchies Drucker [

87], and a climate that supports networking and high sociability of all employees [

10], [

88]. By what we have designated by individual values to build Ba as input for context/relationship among team members as equivalent to the application of Ba in Japanese firms (

Figure 3), we refer equally to any horizontal, vertical, and transversal relationships in the organizational chart of an MNC. By what we have designed as group values to build the “Ba of teams,” we understand an output of culture and/or common values of the entire group/team, creating a continuous innovation within the process of SECI applications. Some studies discuss the context between two people, A and B, or several members of a social group (in general); the context can be physical, virtual, mental, or any combination of the three, as Erden et al. have shown (2008).

The main element in understanding and applying Ba is the "interaction" between team members, between managers and subordinates, and across the whole organization chart; it implies a merging of physical space, virtual space (online), and mental space [

89]. The members of a management team form "the Ba of teams" (see

Figure 3), which in turn will form "the Ba of organization", the latter meaning the specifics of the organizational culture, therefore how the two or three key values that are essential for the company as a whole and each of its members are defined. The expression "mental space" characteristic for Ba automatically leads to the idea of the core values of people involved in an SECI process. In another paper, Nonaka and Takeuchi [

41] discuss not only the SECI model as a specific process for a knowledge-creating company but also the vision, goals, and values governing the effort of employees in some Japanese firms. Therefore, the relationship and context between team members (

Figure 3) and hierarchically have become much more important in applying SECI to describe each member's TK than the "stock" of TK that each employee owns.

The need for continuous employee learning is frequently addressed in the literature on KM and/or culture [

44], [

90], [

91].

The cross-assessment of organizational values/culture (

Appendix A) against the dynamics of cultural values in major countries of the world (

Appendix B and

Appendix C) leads to some valuable conclusions to suggest further novel elements regarding the acquisition of tacit knowledge by firms in continuous innovation processes and some SDGs goals achievement. We notice that trust is a corporate value in the mission statements of 5 of the 22 companies included in the study. In the case of the same companies, we find terms such as "innovation", "education", "sustainability", and "excellence", etc., through which these entities state some of their core values (most frequently derived from learning, knowledge, and sustainable development). In the case of the other 28 companies in the BCG study, as of 2023, some explicitly state "trust", "integrity", “sustainability”, “environment” and "innovation" as core values, and others state these values in terms such as "respect", "humility", etc. (examples: Amazon- learning, trust; Nvidia- learning, innovation; P&G- trust, integrity; Dell- drive, humility; Mercedes- integrity, trust; BMW- trust, openness; Xiaomi- trust, sincerity; Sony- diversity, trust; Saudi Aramco- integrity, ethics; Alibaba- trust, change; PetroChina- trust, faithful; Lenovo- trust, integrity, etc.). Some papers emphasize that not so much the declaration of corporate values is essential, but especially “managing by values” in daily activities under the individual-organizational connection[

92] (pp. 25–36).

Second, the descriptive connection between corporate vs. societal values (for the countries included in the analysis) gives only a general picture of the "value confrontation" between the two types of ethos over time; in most cases, corporate values seem to have increasingly influenced national cultures (not only in the countries of belonging but also in other countries where various MNCs have significant operations/activities). Third, it follows that each major corporation out of the 50 considered most innovative by the BCG defines/modifies/adapts over time some key values around which organizational culture and effective leadership then develop [

7], [

8]. In other words, whatever the recommendations formulated by the theorists, top management in such organizations define values that gravitate toward the relationship between education, trust, knowledge, innovation and sustainable development. In the same sense, the values stated by the MNCs in the BCG study can only, to a small extent, be put in connection with the GOBE 2004 study, namely the 5 clusters on which the 62 countries/societies are grouped [

7].

So far, we argued that values have become, in the last decades, a "catalyst" or "framework" that integrates the effort of the members of a group in the attempt to create the specific context for the use of Ba as an input/output for the successful application of the SECI model for innovation and sustainable development. However, it is difficult for managers to identify which values a group/department in the organizational chart refers to.

The argument constructed by us in the 6.1, 6.2 sections of the study gives us an affirmative answer to RQ1 in the sense that there are some "core values" derived from education, trust and knowledge that are equally important for innovative countries and/or companies aiming sustainable development.

6.3. Ba Concept vs Reference Framework

In Western management, certain concepts have been known and applied regarding the group/team reference framework, the stages of transforming a group into an effective team, the principles of selecting team members for a clearly defined objective/project, etc. This began as early as the 1950s (well before Nonaka and his colleagues published their work “Knowledge Creating Company”). In the present study, as a direct reflection of the cross-analysis between

Appendix A vs.

Appendix B and C, we will limit ourselves to summarizing only two aspects of both conceptual and pragmatic interest.

The first aspect, as mentioned above, taking into account the basic idea suggested by us in

Figure 3, refers to the correspondence that can be seen between the four stages of transforming a group into an effective team (which are well known in Western management) compared to the four types of Ba argued by Nonaka.[

41], [

45], [

52] [

93].

As is well known, the four stages involved in transforming a group from any organizational chart into an efficient/homogeneous team that achieves synergy in monthly/annual performance can be summarized as follows [

61] (pp. 343-346), [

94]:

Forming- is the stage in which the group is formed to fulfill a certain purpose/objective, its members must relate/communicate with each other, evaluate each other, understand the prevailing values of each colleague, etc.

- ✓

Storming- is the stage in which a certain competition for imposition, authority, a disagreement regarding the common future, some tensions, etc. occurs.

- ✓

Norming- is the stage in which after the group members relate directly (face to face, online, etc. as major requirements and for the application of Ba) for a certain period of time, the group members begin to manifest a minimum of solidarity, interdependence and cohesion, including trust, in each other. Therefore, this third stage of building an effective team implies that the group members relate to each other at least for a short period of time (this can be a few days or a few weeks).

- ✓

Performing- is the final stage towards which a team evolves and reaches when its members cooperate willingly with others, have mutual trust, accept the common goal and register an increasingly better performance. It can be said that starting with this stage the group obtains synergy effects and the best performance.

In connection with measuring the performance obtained at team level, psychologists have developed some evaluation tests, among which the “knowledge-skills and abilities” (KSA) test is the most famous – 1994. Such tests do not include, however, either conceptual or pragmatic trust and other values that individuals believe in in modern society.

Regarding the importance of Ba to obtain synergy effects in team management, we briefly mention the four types of Ba [

52] (pp.17-24), [

95]:

- ✓

The first type, originating Ba, shows us the place/context in which members of a group share emotions, experiences and mental models and corresponds, Nonaka argues, to the socialization stage in the SECI model in which the empathy necessary for the creation of new knowledge is established. This initial stage of the SECI model partially corresponds to the forming stage of a group in Western management.

- ✓

The second type, dialoguing Ba, assumes a peer-to-peer relationship between members and is associated by Nonaka with the externalization stage in the SECI model. This assumes dialogue and shared mental models so that part of the tacit knowledge can be described as “explicit knowledge”. This type of Ba has a partial counterpart to the storming and norming stages in Western management regarding the building of an effective team. Including Nonaka, emphasizes that the selection of members of a future team is a process that must be done carefully by the decision-maker precisely in order to associate people who have appropriate knowledge and skills, and subsequently through dialogue and collaboration they will be able to more easily reach the acceptance of norms to achieve a common goal.

- ✓

The type of Ba systematizing is the one in which group members collaborate voluntarily, reflects the combination stage of the SECI model, and has a fairly good correspondent in the “norming” stage of Western management. Both for the application of Ba, and for reaching the norming stage in shared contextual team management must be based on trust and other key values that are voluntarily accepted by all members involved at the group/team level.

- ✓

Finally, the fourth type of Ba, namely, exercising Ba, Nonaka argues is the one that facilitates the conversion from explicit to tacit, is directly connected to the internalization stage of the SECI model, this type involves a real/virtual space and a time shared by members in which each focuses their attention on learning processes and continuous exercise (which has a fairly good correspondence with LLL activities and the performing stage in Western management).

From our perspective, the essence of the Ba concept was applied by Western firms long before the 1970s (so before Japanese MNCs became direct international competitors). As we have shown, the four types of Ba (originating Ba, dialoguing Ba, systematizing Ba, and exercising Ba, each associated with one of the SECI stages) [

89] (pp. 16–32) have a partial correspondence with the four stages of transforming a group into a team in Western management (forming, conflict, cohesion and performance).The previous statement argues that the basic idea of Ba is found in Western management under the name of "reference framework". Ba is successfully applied in various Western multinationals [

96] (p.178) when teams are set up with a clearly defined and ethical purpose. By "reference framework" we mean the common and contextual purpose in which fewer employees are asked to develop specific shared values over time, i.e., a culture at the "mini group" level that supports the group's transformation into an effective management team. Another concept encountered in Western management is that of "enabling context" (similar to "design pattern") when such a context is based on "care and mutual trust", argues Krogh si Ichijo [

96] (pp.44-68). So, whether we are discussing "reference framework" or "enabling context", each concept is a reasonably loose equivalent for the concept of Ba.

The data and/or information that can be deduced based on what is shown in

Appendix A vs.

Appendix B and C do not provide sufficient clarification on another topic in the KM field, namely the way in which various types of tacit knowledge in the organization (previously mentioned by us) are mixed/combined over time with various types of tacit knowledge in society. What can be said with sufficient arguments about the dual relationship invoked is given by the fact that the manifestation of this relationship is also value/culturally dependent, since the register of values and the dynamics of culture begin in all cases with individuals/employees, then continue at the level of organizations and subsequently at the level of countries. The data in the last three columns of

Appendix B show us that the level of trust calculated under WVS over the period 2010-2022 fluctuated greatly in society, as well as towards institutions, especially in the context of the crisis generated by COVID in 2020.

More importantly, core values change relatively quickly at the individual and/or group level since organizational culture is much more dynamic than national culture [

8], [

93], [

97]. According to the 2019 paper, argues Nonaka and Takeuchi, creating a continuous dynamic of innovation in firms requires managers to start from the values and mission assumed by organizations [

93] (p.36); the same idea can be found in Drucker formulated since 1954 [

80], [

95] which means that the goal aimed by any social group has become essential for innovation and business performance.

6.4.“. The Clush of Cultures”: Corporate Culture vs. National Culture

The careful evaluation carried out by us based on the values declared by the 22 MNCs in the BCG study, including those declared through Annual Reports, as well as the synthesis made in the last column of

Appendix A (interpretation of corporate values and their relationship to the 4 organizational dimensions identified by Cameron and Quinn [

64], compared to all the accumulated information that can be deduced from

Appendix B and C regarding the countries, allows us to formulate a type of preliminary conclusion as a result of the proposed study. In order to state and argue this preliminary conclusion in the following

Table 1, we correlated and formulated some cross-interpretations between national values vs. organizational values, which means national culture vs. corporate culture, as well as the inverse relationship from MNCs to countries, the analysis showing that the achievement of some SDG objectives has actually become a frame of reference for all high-performing MNCs in the world. More precisely, we continue by stating some ideas that derive from the previous sections of the of the study, respectively:

It is worth emphasizing the idea that the level of trust in society (whatever the statement made by various BCG companies versus the values shown by WVS and the evolution synthesized by us in the last 3 columns of

Appendix B) fluctuates a lot and relatively at short intervals of time, depending on various social/political crises such as: the COVID-19 crisis, the war in Ukraine, the recent war in the Middle East, etc., which also means an implicit fluctuation in cultural values, but with a different dynamic at the individual vs. organizations vs. countries level.

Our study clearly shows that, at least for the last 2 decades, we are witnessing a clear confrontation between the values/culture of high-performing and innovative MNCs vs. values/culture of major countries in the world. All the arguments we have raised in the study show us that there is a much more pronounced dynamic of the values of culture in high-performing companies compared to the dynamics recorded at the level of companies/countries.

b. Understanding and explaining how hierarchically organized social groups currently achieve performance, continuous innovation and sustainable development must start, first of all, from understanding and explaining the processes of acquiring tacit knowledge and training human experts in companies and other organizations. So this means that all processes of acquiring, storing, sharing, etc. of tacit knowledge in business organizations are the first factor that sets in motion a possible "virtuous circle" between knowledge, innovation, sustainable development, since tacit knowledge in particular (by cumulating with explicit knowledge) has become the essential factor that explains how the companies considered to be the most innovative in the world and which opt, to varying degrees, for the achievement of obligations assumed under the SDGs obtain "core competence".

In

Table 1 below, we have invoked the 4 country rankings vs. the 4 company rankings and separated the issue of trust under WVS, the latter targeting both analysis perspectives (national and organizational simultaneously).

The synthetic picture that can be deduced from

Table 1 is that certain international rankings that classify innovative and/or the most performing companies in certain directions of action also refer to one or more objectives in the SDGs, as a general framework that should be accepted by individuals/employees, teams or departments, as well as business organizations. This deductive conclusion based on the data in

Table 1 must be directly linked to what we call “building a moral capitalism”, meaning that, under the UN, the SDG framework is strong connected with Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) adopted by companies.

The aspects invoked by us in the last two sections of the study in the sense that provide us with the necessary support to confirm RQ2 in the sense that some "key values" can be identified (we suggested education, systemic trust and tacit knowledge, but each firm is free to state its own corporate values) which explain the application of the SECI model by innovative companies and the use of TK types that are defined by the highest degree of tacitness to obtain core competencies. In other words, the RQ2 is confirmed with the mention that the need to develop in the first place some core values as a necessary condition to obtain the synergy effect at the team level/department and only then can apply successfully Ba and SECI model for sustainable innovation and core competence.

In the final part of our study, we show that the entire framework offered by the SDGs has become essential/necessary for MNCs and SMEs aiming at continuous innovation, sustainable development and the voluntary assumption of social obligations as part of CSR. Moreover, in the sense invoked, we recall that there are over 25,000 companies that have voluntarily assumed certain ethical principles for the existing competition on various markets throughout what we call post-capitalist society[

98], [

99], [

100]. In the 1980s, business ethics and CSR were more of a series of idealistic statements by investors, managers and policymakers. Drucker had been arguing since the 1980s that economic progress in the capitalist world must include the conservation of material resources to provide a chance for the unpredictable future; this economic progress would have to be based, he said, on knowledge and innovation [

101] (pp. 28-30). Instead, at the present time, the need to build a moral capitalism that balances the interests/objectives of the current generation with those of future generations in various countries of the world is becoming increasingly clear. The idea of building a moral capitalism has become today not only opportune but also necessary to prevent the effects of social crises such as the Great Recession of 2008-2010. In this sense, some organizations such as the Caux Round Table for Moral Capitalism[

102], argue that the commitment of some companies to certain obligations under CSR does not implicitly limit the performance and/or profitability of those companies.

More recently, a significant number of authors[

103], [

104] bring credible arguments regarding the need to build a moral capitalism throughout the Western world. Over two decades ago Huntington argued the idea that values/culture have become essential for modern society, respectively the foreseeable tensions between the main countries of the world will be of a cultural/civilizational nature[

77]. The same Drucker [

105] argued in the 90s, the idea that even large corporations can learn from non-profit organizations some important aspects regarding voluntary responsibility and compliance with norms/ethics/rules in everything that means competition and cooperation on various markets.

7. Conclusions

As the argumentation built in our study shows, the problem of simultaneously assessing the dynamics of value/culture in companies and major countries of the world is actually a relatively complex one. However, deepening this value relationship, based on international rankings, offers us an additional opportunity to understand how innovative MNCs that manage to enter the BCG top almost every year proceed in terms of acquiring new knowledge, obtaining patents and assuming responsibilities under SDGs. At the end of our study, several conclusions can be formulated that highlight the elements of novelty brought by us, as well as directions of action of interest for companies for applying Ba, the SECI model, for the purpose of continuous innovation and sustainable development.

First of all, it turns out that at the basis of the processes of acquisition of new knowledge and sustainable innovation in companies/countries is tacit knowledge as an unlimited resource, which means qualified employees who accept to learn continuously. This means that the recourse to various processes of acquisition/valorization of knowledge is directly dependent on key values such as education or trust that are simultaneously accepted/shared by individuals, companies and countries.

Secondly, our study leads to the conclusion that the entire issue known in Western management regarding building efficient/homogeneous teams and implicitly obtaining the synergy effect in innovation activities, must be redefined/reconceptualized. This is because it argues with sufficient clarity that companies can resort to applying the Ba concept for synergy at the team level and/or the reference framework to achieve approximately the same result in the innovation and sustainable development activity. It is deduced that innovative companies that are committed to the objectives of the SDGs must have a culture based on education, trust and knowledge as key values for the formation of human experts necessary to achieve sustainable innovations.

Finally, thirdly, our study shows with sufficient argument (

Table 1, section 6.4) that various objectives of the 17 proposed by the SDGs are actually at the "intersection" of cultural values between organizational and national. In the last two decades, the values/culture of large corporations tend to become much stronger, in terms of influence, than the national values/culture. In this direction of evolution of society in the coming decades, companies should propose to build efficient strategies for the application of KM in the hope that, benefiting from qualified and motivated employees, they will gradually obtain sustainable innovations and core competence.

In direct relation to the basic idea of the present study, namely the influence of culture on the acquisition of new knowledge (tacit and explicit) as an unlimited resource for innovation and SDGs at the company/country level, the authors foresee several research directions for the future. This is because, in the dynamics of time, it is appropriate and necessary to continuously extend/develop fundamental concepts in management, such as KM and the evolution of cultural values for sustainable innovation in SDGs.

Drucker argued several other main ideas before 1995 when Nonaka and Takeuchi published their seminal paper "Knowledge-Creating Company". One possible RQ for the future can be: "What would be the pragmatic implications of a comparative analysis between Drucker's thinking (1940-1995) vs. the thinking of Nonaka and his collaborators (1995-2025)?"

Another research direction on the topic of this study is given by the importance that can be interwoven between the concept of EI (emotional intelligence) for firms' successful application of Ba.

*On request, the authors may submit electronically the entire database on which the study is based and the Annual Reports 2023 for each company in the BCG study.