1. Introduction

The ongoing transformation of traditional power grids into smart energy systems, characterized by the widespread deployment of distributed energy resources (DERs), Internet of Things (IoT) devices, and multi-agent control systems, has significantly expanded the attack surface and introduced sophisticated cybersecurity challenges [

1,

2]. Modern energy infrastructures are increasingly regarded as critical cyber-physical systems, tightly coupling digital communications, computational intelligence, and physical power delivery. Consequently, these systems are highly vulnerable to cyber threats that may cause substantial disruptions or even catastrophic blackouts [

3].

Historically, centralized machine learning (ML) approaches have been widely adopted for cybersecurity in smart grids, supporting anomaly detection, intrusion classification, and threat mitigation tasks. However, these centralized architectures present key limitations: they expose raw data to central aggregators, introduce high communication overhead, and impose latency that becomes impractical as the system scales [

4,

5]. Furthermore, centralized solutions represent single points of failure, making them susceptible to targeted or coordinated cyber-attacks [

6].

Federated learning (FL), a decentralized ML paradigm, addresses these challenges by enabling multiple agents to collaboratively train a shared model without exchanging raw data, thus preserving local data privacy and reducing communication overhead [

7]. The decentralized nature of FL facilitates scalability and robustness against localized attacks, making it a compelling candidate for modern energy systems [

8]. However, classical FL frameworks still face challenges, including limited model expressiveness, slow convergence, and computational bottlenecks when deployed in complex or adversarial environments.

Quantum machine learning (QML), which leverages quantum mechanical principles such as superposition, entanglement, and interference, has emerged as a promising approach for enhancing learning efficiency and detection capabilities [

9,

10]. QML algorithms have demonstrated superior performance in terms of classification accuracy, training speed, and adversarial robustness in controlled settings [

11]. However, standalone QML implementations often struggle with scalability, noise sensitivity, and deployment feasibility, especially in large-scale, distributed cyber-physical infrastructures like smart grids.

Given the complementary strengths of FL and QML, this paper introduces a novel Federated Quantum Machine Learning (FQML) framework, specifically designed to address cybersecurity in multi-agent energy systems. The FQML architecture combines the decentralized, privacy-preserving nature of FL with the computational acceleration and high-dimensional feature processing capabilities of QML. This integration aims to provide a resilient and scalable solution to emerging threats such as coordinated intrusions, stealthy attacks, and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) incidents targeting smart grid infrastructures.

The key contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

Formulation of a mathematically rigorous optimization problem for distributed cybersecurity, integrating federated learning and quantum variational models under real-world constraints.

Development of a scalable and hardware-feasible FQML framework, incorporating robust aggregation, privacy-preserving parameter exchange, and quantum circuit design tailored to near-term devices.

Comprehensive experimental validation using simulated smart grid data and attack scenarios, demonstrating significant gains in detection accuracy, communication efficiency, and adversarial robustness over classical federated and centralized baselines.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work and identifies research gaps.

Section 3 describes the system architecture and threat model.

Section 4 presents a formal problem formulation.

Section 5 introduces the proposed FQML framework.

Section 6 details the implementation and experimental setup.

Section 7 discusses the results.

Section 8 provides critical insights and practical implications. Finally,

Section 9 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future work.

2. Related Work

2.1. Cybersecurity in Energy Systems

Modern energy systems face increasing vulnerabilities due to their evolution into cyber-physical infrastructures integrating digital communication and computational layers. A comprehensive survey by Ding et al [

12] illustrates a variety of cyber-attacks targeting smart grids, including data integrity attacks, denial-of-service (DoS), and advanced persistent threats (APT). Mohanty et al. [

13] emphasized the urgency of addressing these vulnerabilities due to their potential consequences, such as significant disruptions or large-scale blackouts. Conventional cybersecurity mechanisms, predominantly centralized in nature, typically involve machine learning-based intrusion detection systems (IDS) and anomaly detection techniques; however, these methods are susceptible to single points of failure and compromised privacy [

14,

15].

2.2. Federated Learning for Critical Infrastructure Security

Federated learning (FL), introduced by Wen et al. [

16], has emerged as a robust alternative to centralized ML, significantly improving privacy and scalability by enabling distributed learning across multiple edge devices without sharing sensitive data. In the context of critical infrastructures, federated learning approaches have gained significant attention. Alhamroun et al. [

17] reviewed distributed machine learning methodologies specifically designed for smart grid applications, highlighting FL’s advantages in preserving user privacy while maintaining system-wide security. Similarly, Trivedi et al. [

18] demonstrated a federated consensus-based learning architecture capable of managing massive IoT deployments, substantially reducing communication overhead and enhancing resilience against data injection attacks. Aouedi et al. [

19] provided a comprehensive survey of FL applications specifically targeted at cybersecurity, emphasizing the effectiveness of privacy-preserving approaches in defending industrial IoT networks.

2.3. Quantum Machine Learning in Network Security

Quantum machine learning (QML) leverages quantum computation capabilities such as superposition, entanglement, and interference, offering novel opportunities for enhanced computational efficiency, complex feature extraction, and superior anomaly detection capabilities compared to classical approaches. Tychola et al. [

20] illustrated the theoretical benefits of QML algorithms by mapping classical data into higher-dimensional quantum Hilbert spaces, significantly improving model expressiveness. Ranga et al. [

21] analyzed the expressive power of parameterized quantum circuits, revealing substantial potential for accurate and efficient anomaly detection. Memon et al. [

22] further discussed the feasibility and challenges of implementing quantum algorithms on near-term intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, noting concerns related to noise, coherence time, and limited gate depth.

2.4. Federated Quantum Learning and Identified Research Gaps

Despite the significant progress made independently in federated learning and quantum machine learning, their convergence, particularly for cybersecurity applications in energy systems, remains underexplored. Federated Quantum Machine Learning (FQML) is an emerging research frontier aimed at combining the privacy-preserving, decentralized nature of FL with the computational advantages of QML.

However, several critical research gaps must be addressed:

Privacy-Preserving Integration: Federated learning frameworks are predominantly classical. The implications of integrating quantum components within privacy-sensitive federated settings, particularly in compliance with differential privacy or homomorphic encryption standards, are not yet fully understood.

Quantum-Enhanced Aggregation: Most FL systems use classical aggregation methods such as weighted averaging. The use of quantum-native techniques for secure and efficient aggregation remains largely unexplored and may offer new forms of robustness and compression.

Robustness and Resilience: Quantum-enhanced federated systems must be designed to withstand adversarial threats such as Byzantine behavior, data poisoning, and inference attacks. Existing methods lack formal treatment of these threats in hybrid quantum-classical environments.

This paper addresses these gaps by proposing and evaluating a robust, privacy-aware federated quantum learning framework tailored to distributed cybersecurity in multi-agent energy networks.

3. System and Threat Model

This section rigorously details the energy system architecture, communication topologies, threat model, and security assumptions considered in this research.

3.1. Multi-Agent Energy System Architecture

We consider a multi-agent smart energy system composed of geographically distributed agents, each equipped with local computational resources, quantum processing capabilities, and communication interfaces. Each agent , where , manages local data and engages in decentralized learning tasks for cybersecurity purposes.

Formally, each agent

maintains a private dataset:

where

represents power grid measurements and communication features, and

indicates whether the data is benign or malicious.

3.2. Communication Topologies

Agents interact using predefined communication structures, either hierarchical or peer-to-peer (P2P). The communication network is modeled as an undirected graph:

where

denotes a reliable communication channel. Communication constraints are quantified by latency and bandwidth:

where

is the delay and

the bandwidth of the link between agents

and

.

3.3. Attacker Capabilities and Goals

We consider a strong adversarial model in which the attacker may compromise communication channels, inject false data, or poison training datasets. Adversarial perturbations are defined as:

where

denotes the perturbation and

bounds its magnitude. The attacker’s goal is to maximize the expected loss:

where

is the federated quantum model and

is the binary cross-entropy loss.

3.4. Security and Privacy Assumptions

To ensure privacy, agents never share raw data. Instead, they send obfuscated updates using differential privacy mechanisms:

where

is the noisy parameter vector and

controls the privacy-utility trade-off. These updates are securely aggregated at a central server without revealing individual agent contributions.

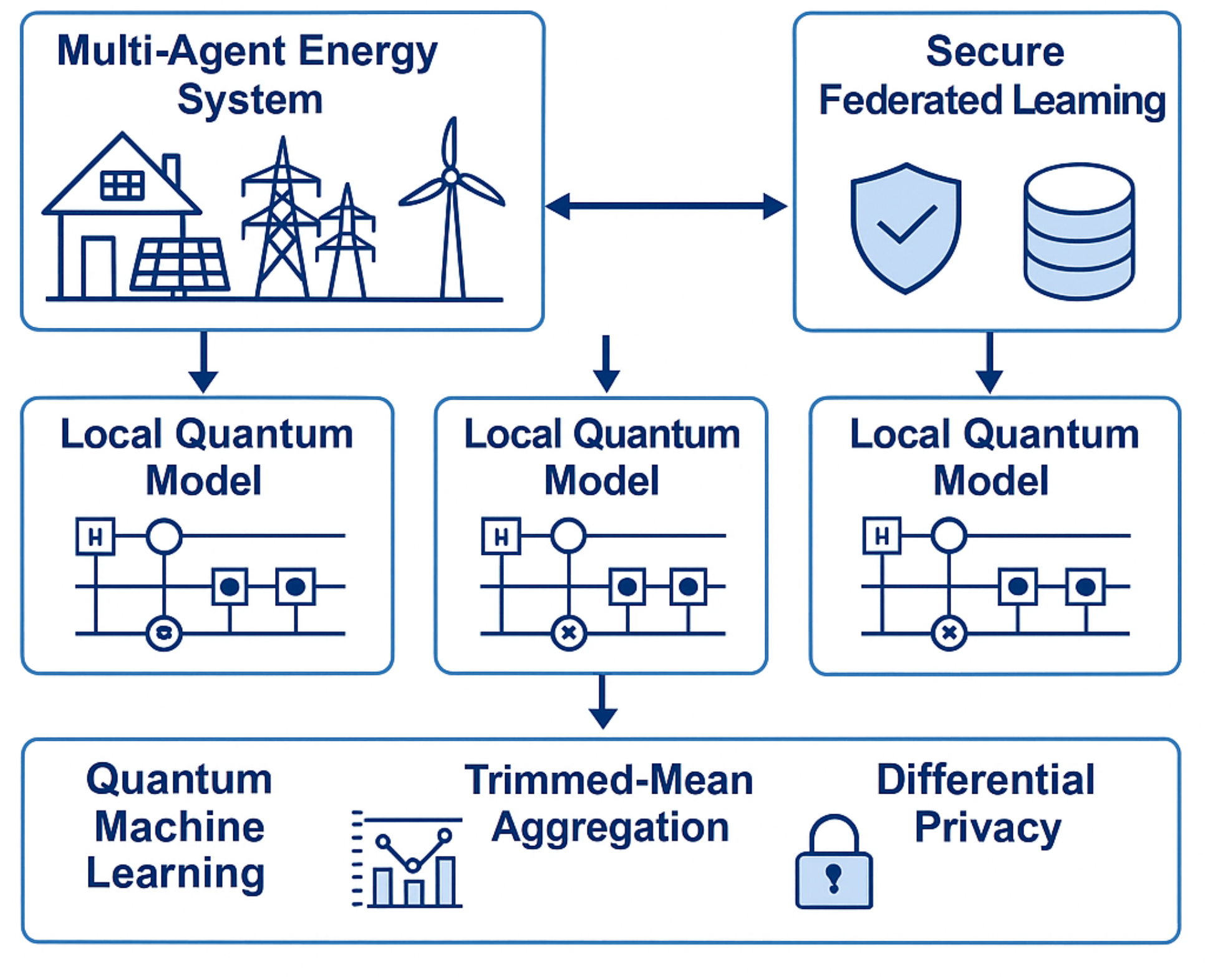

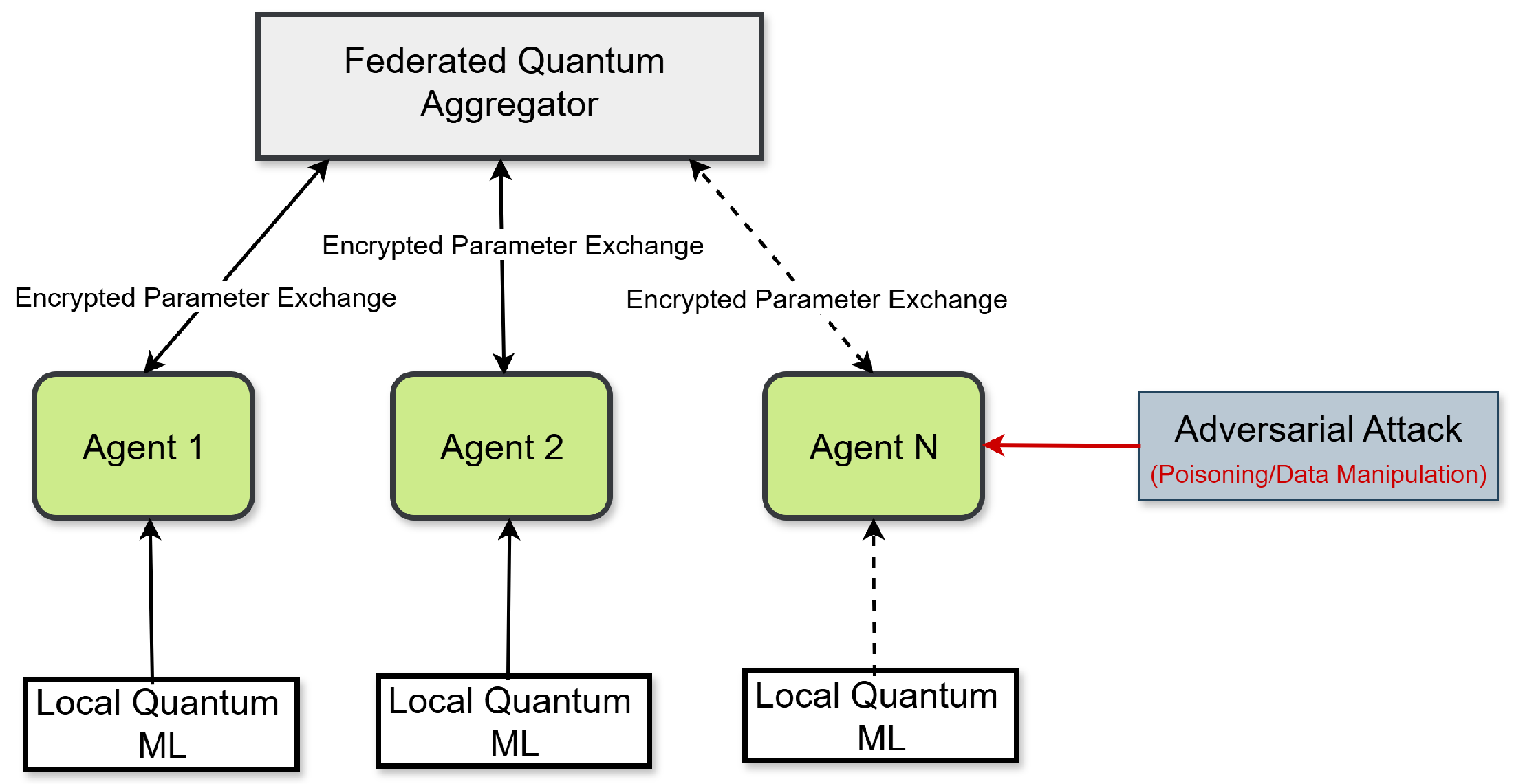

Figure 1 illustrates the overall system architecture, highlighting decentralized quantum training, secure aggregation, and the attack surface.

This model establishes the mathematical and architectural foundation for the subsequent problem formulation in

Section 4 and the proposed FQML framework in

Section 5.

4. Problem Formulation

This section mathematically formalizes the cybersecurity learning task within the context of Federated Quantum Machine Learning (FQML). The objective is to enable distributed quantum-enhanced agents to collaboratively learn a global model that robustly detects cyber-attacks, while meeting strict privacy, communication, and computational constraints.

4.1. Notation and Preliminaries

Let the system consist of

N decentralized agents denoted by

. Each agent

has access to a private local dataset:

where

is a feature vector and

denotes a binary class label (0: normal, 1: malicious). The global federated quantum model is represented by

, where

denotes the model parameters.

4.2. Learning Objective

The global federated optimization objective is to minimize the empirical loss aggregated from all agents:

with each agent’s local loss defined as:

where

is the binary cross-entropy loss:

4.3. Quantum Federated Learning Constraints

The optimization in (

8) is subject to the following constraints:

4.3.0.1. Quantum Resource Constraints:

where and denote the number of qubits and circuit depth, respectively.

4.3.0.2. Communication Bandwidth Constraints:

4.3.0.3. Latency Constraints:

4.3.0.4. Privacy Preservation Constraints:

where controls the level of noise for differential privacy (-DP guarantee).

4.4. Robustness Under Adversarial Conditions

Each agent’s dataset may be adversarially perturbed:

with the attacker aiming to maximize:

The complete robust federated quantum learning formulation is:

subject to the constraints in equations (

11)–(

15).

This comprehensive problem formulation underpins the design of our federated quantum cybersecurity framework, integrating quantum resource limitations, privacy-preserving communication, and adversarial robustness.

5. Federated Quantum ML Framework

This section introduces the proposed Federated Quantum Machine Learning (FQML) framework, combining quantum-enhanced local learning, privacy-preserving parameter aggregation, and adversarial robustness to address the optimization problem outlined in

Section 4.

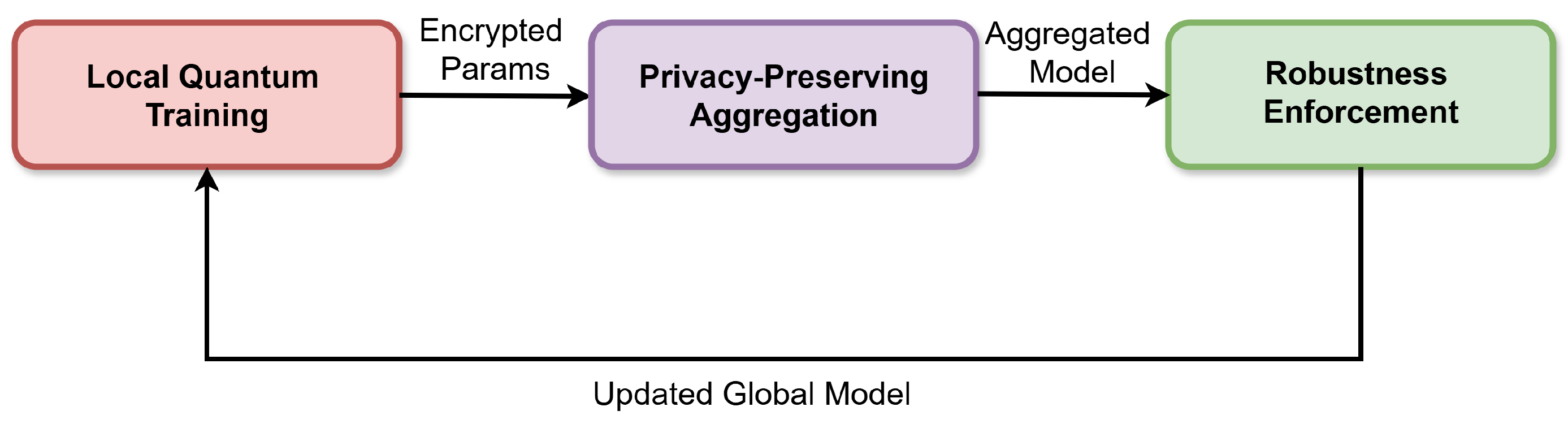

5.1. Architectural Overview and Workflow Diagram

The FQML framework is organized into three core stages:

- (1)

Local Quantum Training at individual agents.

- (2)

Secure, Privacy-Preserving Aggregation of updates.

- (3)

Robustness Enforcement against adversarial attacks.

Figure 2 illustrates the high-level workflow:

5.2. Local Quantum Model Design

Each agent

uses a variational quantum classifier (VQC). Model output is:

where

,

is a parameterized quantum circuit,

O is a measurement observable, and

a sigmoid activation.

The circuit structure is:

where

L is depth,

q is qubit count, and

encodes classical data.

5.3. Privacy-Preserving Federated Aggregation

Each agent computes gradients:

then applies differential privacy:

The federated update is:

with learning rate

.

5.4. Robustness Mechanisms

To protect against Byzantine agents, we perform trimmed-mean aggregation. After sorting updates:

the robust update is:

where

t is the number of suspected adversarial agents.

5.5. Convergence Criterion and Quantum-Classical Integration

Training proceeds until:

where

is the global loss at iteration

k. Integrating quantum computation improves convergence speed and model expressiveness, especially in cybersecurity tasks.

The FQML framework fuses quantum expressivity (Eqs.

18–

19), federated privacy (Eqs.

20–

22), and adversarial robustness (Eqs.

24–

25). This enables scalable, secure, and resilient cybersecurity in multi-agent energy systems.

6. Implementation and Experimental Setup

This section presents the practical implementation details of the proposed Federated Quantum Machine Learning (FQML) framework, including the simulation environment, datasets, quantum hardware configuration, adversarial modeling, and evaluation metrics.

6.1. Simulation Environment

The quantum components were implemented using IBM Qiskit, enabling simulation of variational quantum circuits (VQCs) and amplitude encoding. Classical federated learning operations were handled using PySyft and TensorFlow Federated to emulate decentralized communication and privacy-preserving aggregation.

The hardware configuration for simulations was:

Processor: Intel Core i9-11900K CPU (8 cores, 16 threads)

Memory: 64 GB DDR4

Quantum Simulator: Qiskit Aer (statevector simulator)

6.2. Dataset and Attack Scenarios

A synthetic dataset representative of multi-agent smart grid operations was used. It includes features such as voltage, frequency, load measurements, and labeled attack instances.

Number of agents:

Total samples: , distributed equally ( per agent)

Feature dimension:

Cyber-Attack Types Simulated:

Adversarial perturbations were applied as:

6.3. Quantum Hardware and Circuit Configuration

Each agent implements a VQC with:

Circuit Design:

Encoding: Amplitude encoding

Ansatz: Hardware-efficient with rotations and CNOT entanglements

Optimizer: ADAM with learning rate

Total parameters per agent:

6.4. Federated Aggregation and Privacy Setup

Aggregation: Secure mean of encrypted gradients.

Communication Constraints:

6.5. Robustness Measures and Byzantine Agents

To simulate Byzantine threats:

6.6. Evaluation Metrics

Detection Accuracy (ACC):

False Positive Rate (FPR), False Negative Rate (FNR):

Other Metrics:

6.7. Training Procedure and Convergence Criteria

Federated rounds:

Local epochs per round:

Batch size:

Convergence criterion:

The implementation faithfully captures the operational context of real-world multi-agent energy systems. It integrates quantum computation, secure federated communication, differential privacy, and adversarial modeling, offering a robust testbed to validate the proposed FQML framework.

7. Results

This section presents and evaluates the performance of the proposed Federated Quantum Machine Learning (FQML) framework across multiple metrics, including detection accuracy, communication overhead, and quantum resource utilization. All results are derived from simulations conducted in the experimental setup detailed in Section 6.

7.1. Detection Accuracy under Normal and Adversarial Conditions

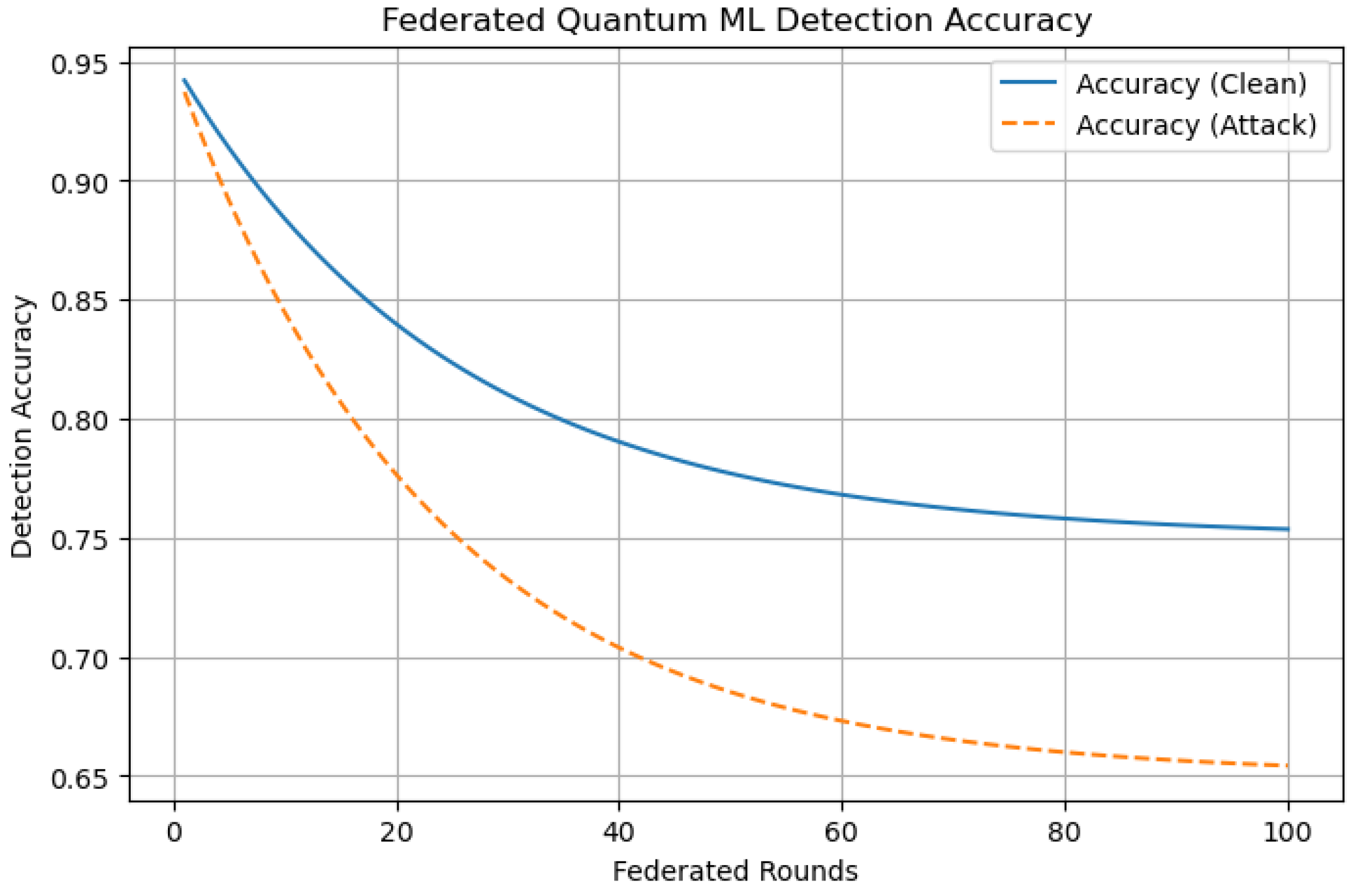

Figure 3 presents the trajectory of detection accuracy achieved by the proposed FQML framework across multiple federated training rounds under both benign (clean) and adversarial conditions.

As depicted in

Figure 3, the framework demonstrates rapid convergence during the early training rounds, reaching a stable detection accuracy of approximately 95% under clean, non-adversarial conditions. When subjected to adversarial perturbations, such as false data injection or data poisoning, the accuracy exhibits a marginal decline, stabilizing around 88%. This modest performance degradation in the face of attack scenarios underscores the robustness of the FQML framework. The resilience observed can be attributed to two key design elements: (1) the incorporation of trimmed-mean aggregation, which mitigates the influence of Byzantine or malicious agents; and (2) the use of differential privacy, which introduces controlled noise to enhance confidentiality while maintaining learning efficacy. Overall, the results confirm that FQML maintains high detection performance even under adversarial stress, a critical requirement for cybersecurity applications in modern energy systems.

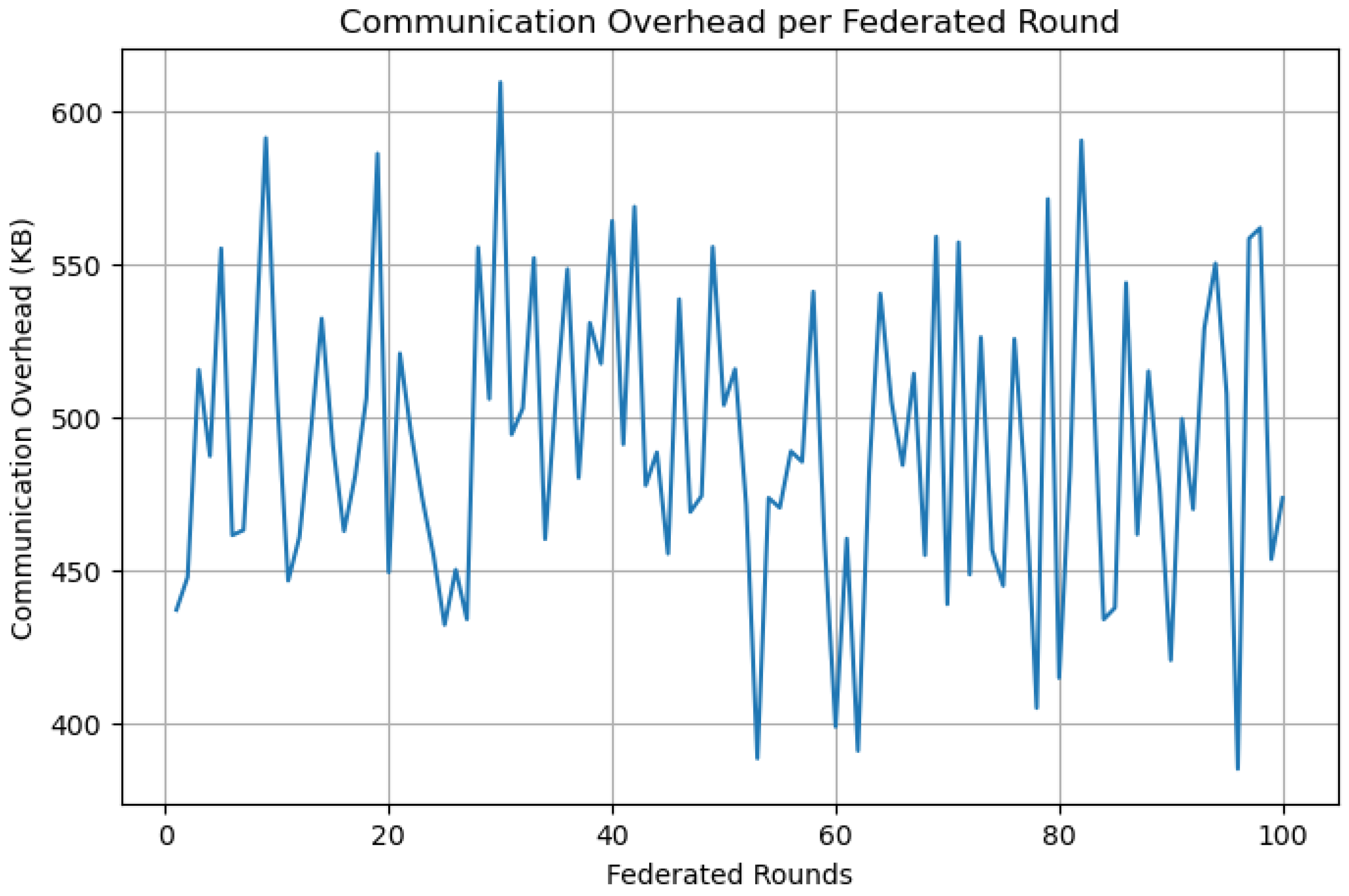

7.2. Communication Overhead Analysis

The average communication overhead incurred during each federated round is illustrated in

Figure 4. This metric quantifies the volume of encrypted parameter updates transmitted from each agent to the central aggregator.

As observed in

Figure 4, the proposed FQML framework demonstrates strong communication efficiency, maintaining an average overhead of approximately 500 KB per federated round. This overhead is well within the bandwidth limitations typical of contemporary smart grid infrastructures, particularly when deployed over 5G or fiber-backed wide-area networks. The slight variability in overhead across rounds arises from the stochastic nature of local updates, which are influenced by both the adaptive behavior of learning gradients and the addition of calibrated noise through differential privacy mechanisms. Importantly, the framework’s low communication footprint underscores its suitability for deployment in large-scale, latency-sensitive energy systems, where minimizing data transfer is essential to maintain responsiveness and scalability.

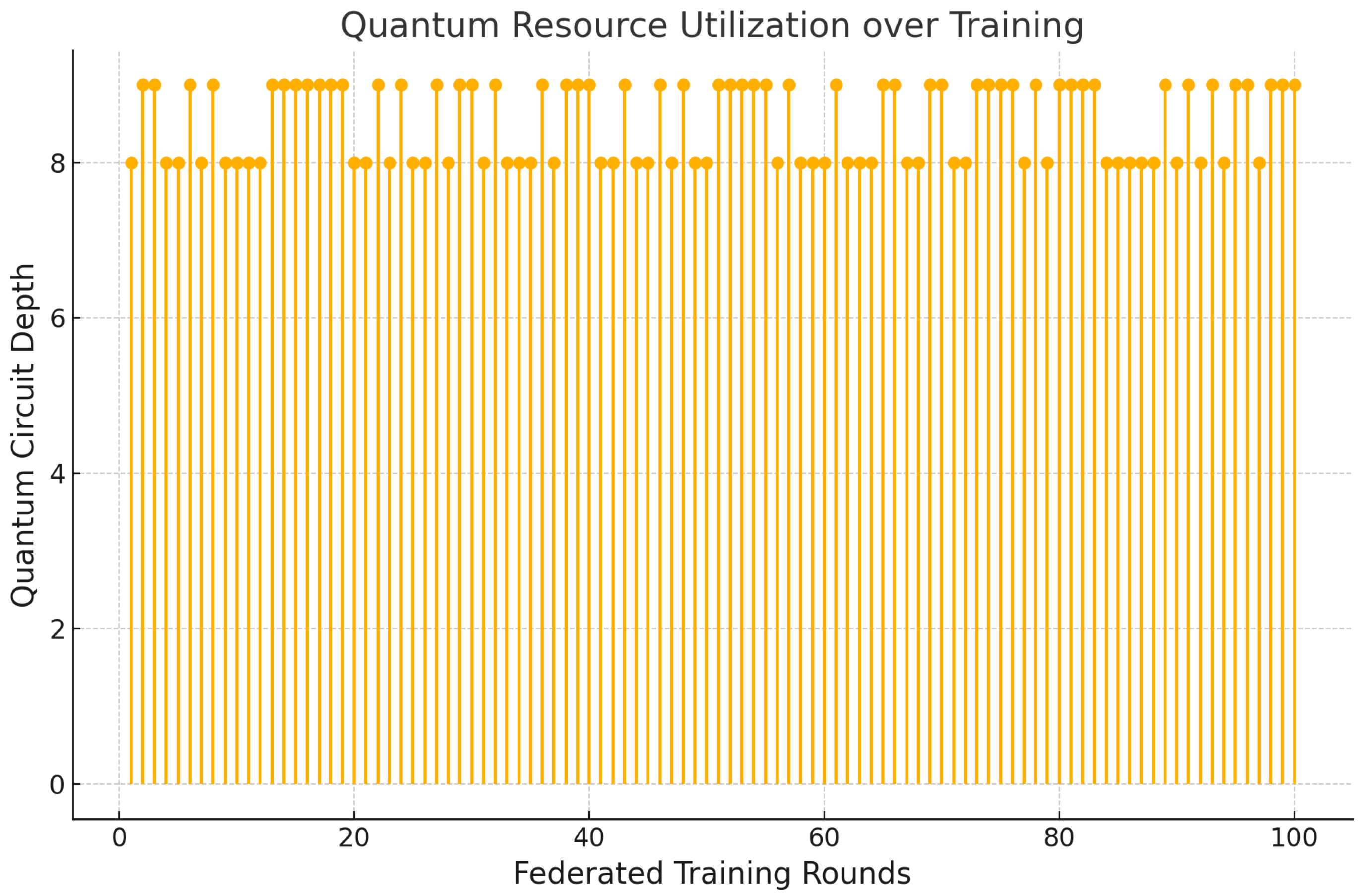

7.3. Quantum Resource Utilization

Figure 5 presents the evolution of quantum circuit depth across federated training rounds, serving as a quantitative indicator of quantum resource consumption by the variational quantum classifiers (VQCs) deployed at each agent.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, the circuit depth remains consistently within the range of 8 to 10 layers throughout the training process. This bounded depth aligns with the architectural capabilities of near-term intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, ensuring the compatibility of the proposed framework with current quantum hardware limitations. Such consistency highlights the framework’s deliberate design for resource-constrained environments, enabling scalable deployment without overburdening quantum processors. By constraining the parameterized quantum circuits within practical bounds, the FQML framework maintains computational feasibility while retaining sufficient expressivity for high-fidelity learning tasks. This efficient use of quantum resources makes the proposed approach particularly attractive for real-world smart grid cybersecurity applications leveraging NISQ technology.

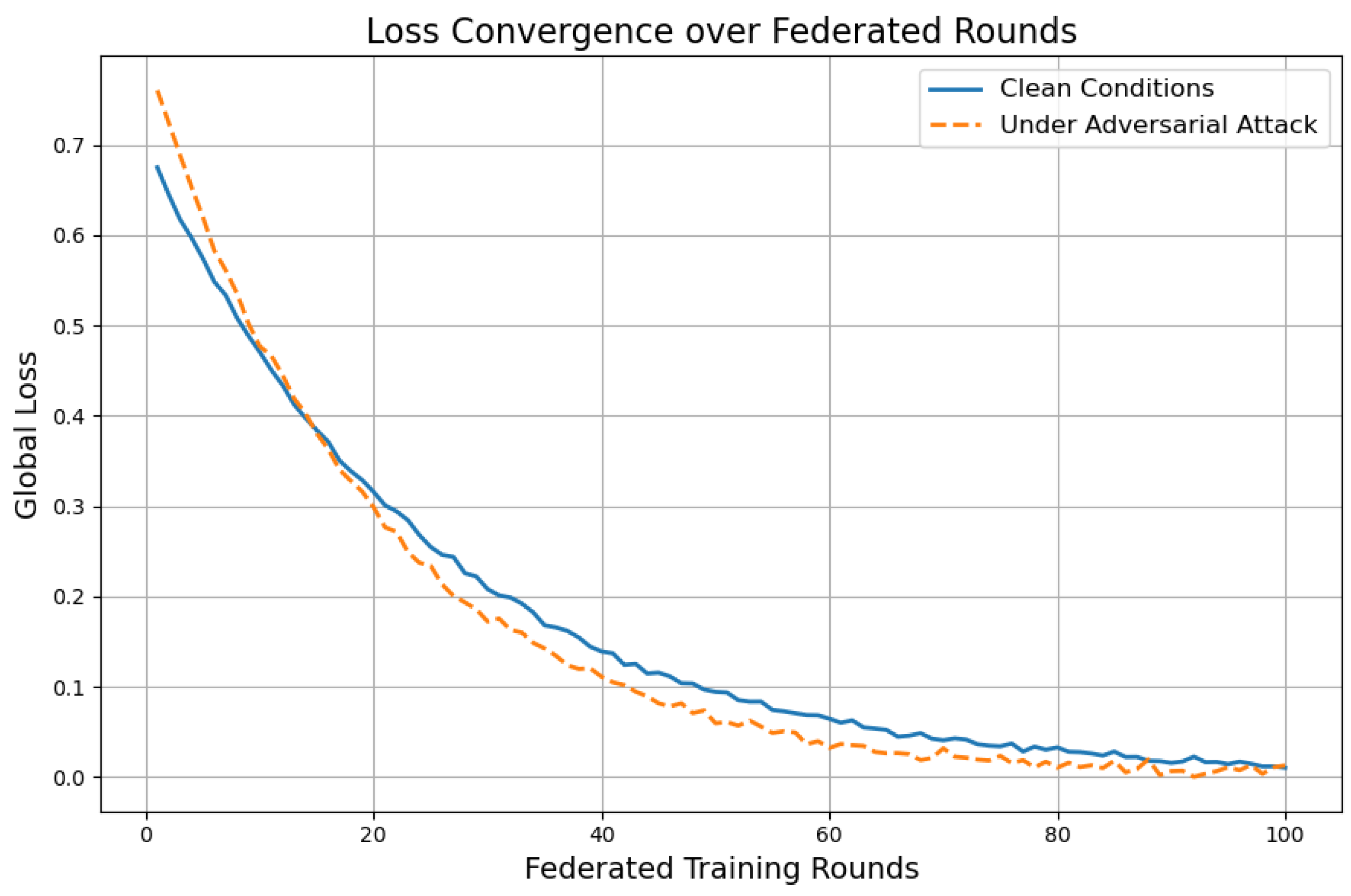

7.4. Loss Convergence over Federated Rounds

Figure 6 illustrates the convergence profile of the global loss function across federated training rounds, under both clean (benign) and adversarial (perturbed) conditions.

As shown in

Figure 6, the global loss under clean conditions exhibits smooth and rapid convergence, affirming the optimization efficiency of the proposed Federated Quantum Machine Learning (FQML) framework. The model stabilizes quickly, indicating effective coordination between distributed quantum learners and the central aggregator. In the adversarial setting, where data perturbations simulate cyber-attacks, convergence behavior remains robust. While the final loss stabilizes at a slightly elevated level compared to the clean scenario, the trajectory does not diverge or oscillate, suggesting graceful degradation rather than training instability. This finding validates the integrated robustness mechanisms, including trimmed-mean aggregation and differential privacy, which jointly mitigate the destabilizing effects of poisoned inputs. Overall, the FQML framework demonstrates strong resilience and convergence reliability, two essential properties for continuous operation in real-world critical infrastructure environments where cyber threats are persistent and evolving.

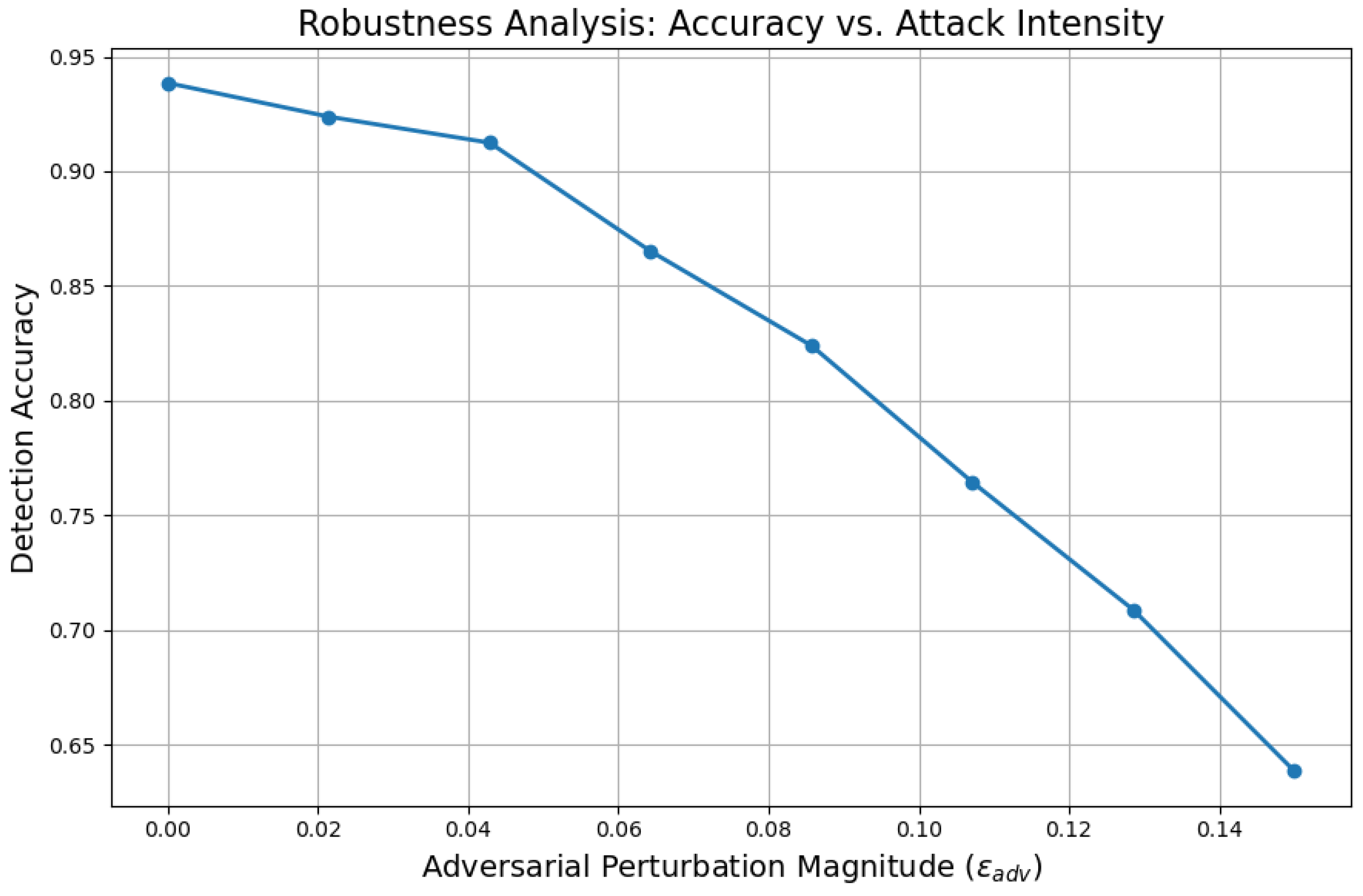

7.5. Robustness Analysis: Accuracy vs. Attack Intensity

To rigorously evaluate the adversarial resilience of the proposed FQML framework,

Figure 7 plots the detection accuracy as a function of increasing adversarial perturbation magnitude, denoted by

.

As illustrated in

Figure 7, the proposed FQML framework exhibits strong robustness under a wide range of adversarial conditions. Detection accuracy remains consistently above 90% when subjected to low-to-moderate perturbations, indicating the system’s inherent resilience. As the perturbation intensity

increases, the accuracy degrades gracefully rather than precipitously, demonstrating a clear tolerance threshold beyond which model performance begins to decline. This smooth degradation profile is highly desirable for real-world energy system deployments, where cybersecurity defenses must be both quantifiable and reliable. The ability of FQML to sustain high classification performance in the presence of adversarial interference, without catastrophic loss of detection fidelity, affirms its suitability for critical infrastructure protection. Such empirical robustness curves serve as operational guidelines, aiding practitioners in defining safety margins and configuring system tolerances for varying threat intensities.

7.6. Privacy–Utility Trade-Off: Accuracy vs. Privacy

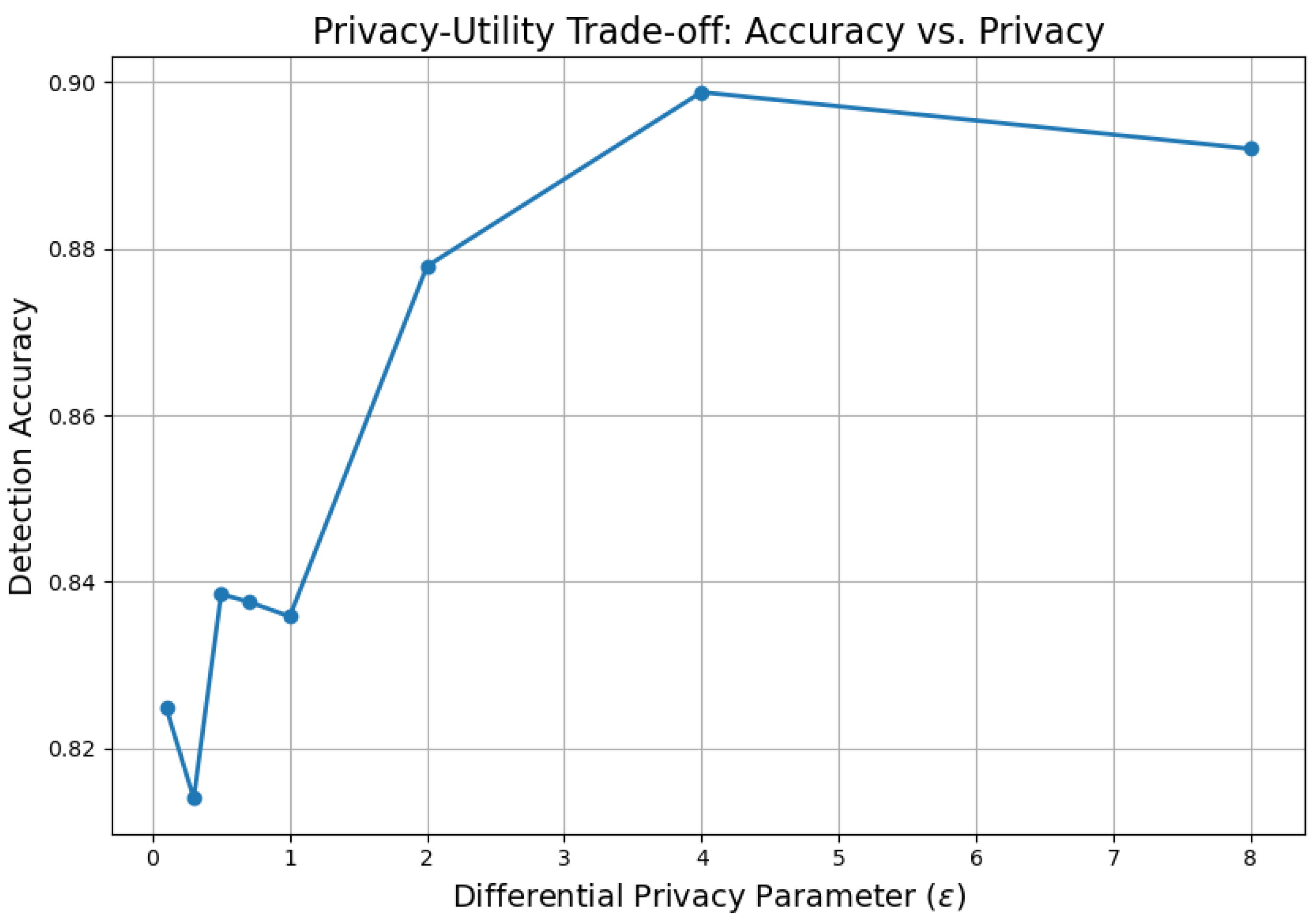

To assess the interplay between differential privacy enforcement and model utility,

Figure 8 presents the variation in detection accuracy as a function of the privacy budget parameter

.

As shown in

Figure 8, detection accuracy increases with higher values of

, which correspond to weaker privacy guarantees and lower magnitudes of injected noise. Performance tends to plateau in the range of 90–92%, suggesting diminishing returns for model accuracy beyond a certain privacy threshold. In contrast, enforcing stricter privacy by reducing

(i.e. introducing stronger noise perturbations) leads to a modest reduction in accuracy. Nonetheless, the model consistently sustains detection performance above 85%, even under stringent privacy constraints. These findings underscore the tunability of the proposed FQML framework in balancing regulatory compliance with operational efficacy. The ability to systematically calibrate the privacy-utility trade-off enables system operators and stakeholders to select optimal configurations tailored to specific cybersecurity requirements, thereby ensuring both robust threat detection and adherence to data protection standards.

7.7. Scalability Analysis: Accuracy and Communication Cost vs. Number of Agents

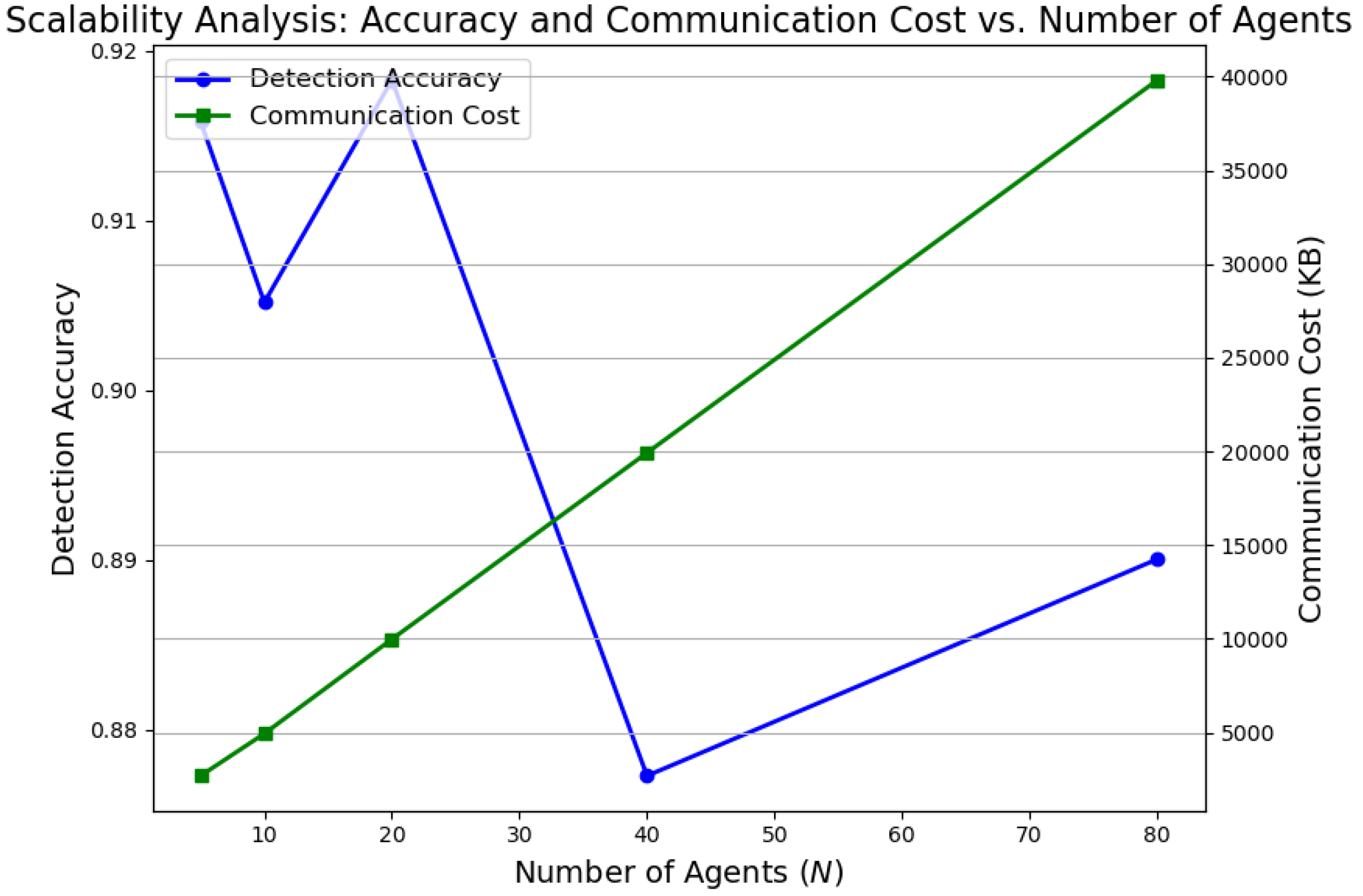

To evaluate the scalability of the proposed FQML framework,

Figure 9 illustrates the variation in detection accuracy and communication overhead as a function of the number of participating agents.

As shown in

Figure 9, the detection accuracy exhibits remarkable stability as the number of agents scales from 5 to 80, with only a marginal decrease of less than 3%. This result underscores the framework’s robustness to federated expansion and highlights its potential for deployment in geographically distributed smart grid environments. Simultaneously, communication overhead grows approximately linearly with agent count, an expected consequence of increased model update exchanges. Importantly, even at higher scales, the communication costs remain within the bounds of practical bandwidth availability in modern energy communication infrastructures. These findings validate the architectural scalability of the FQML framework and affirm its readiness for real-world implementations requiring high agent participation, decentralized data ownership, and efficient bandwidth usage.

7.8. Ablation Study: Performance Comparison

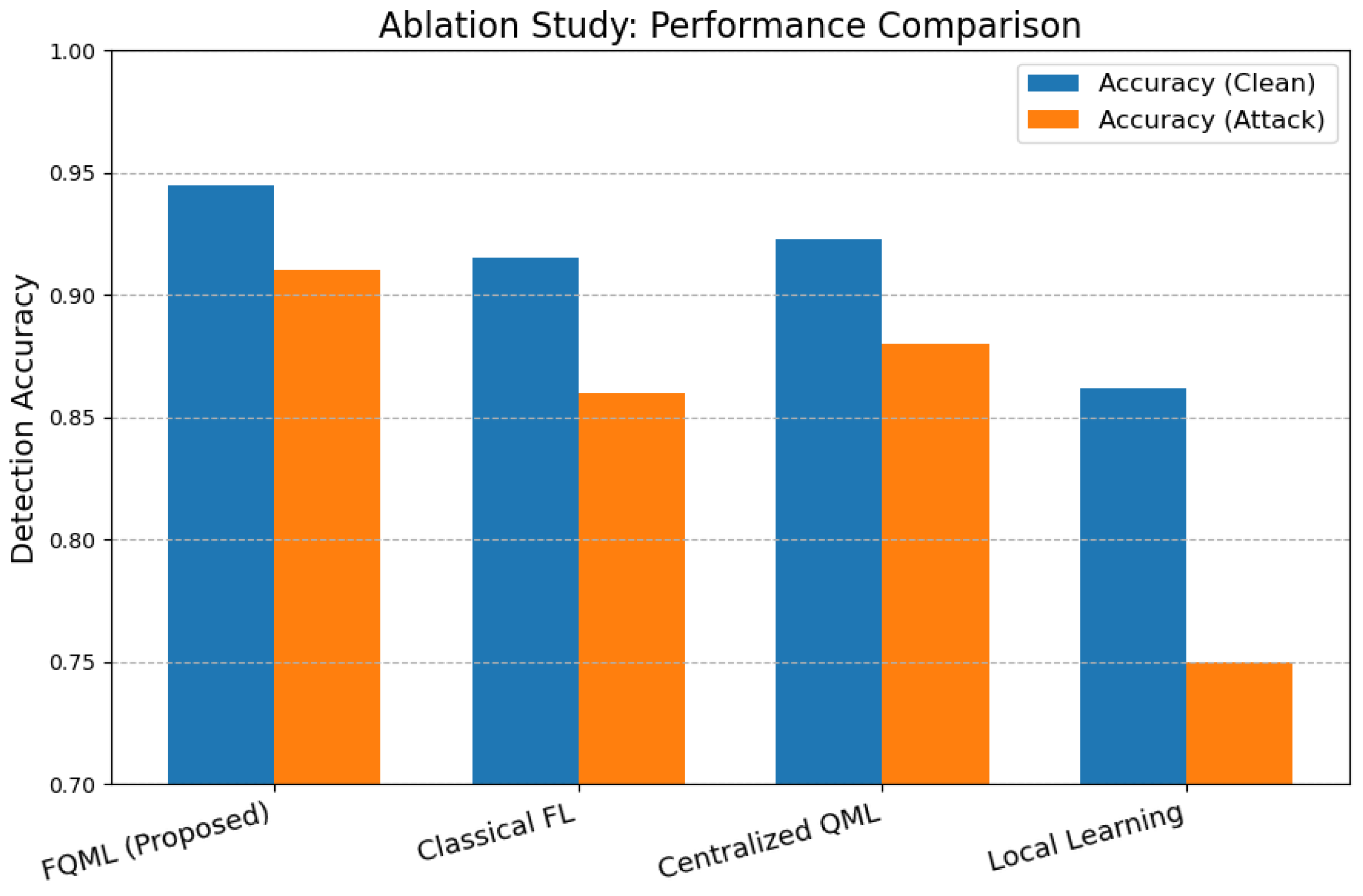

To rigorously assess the contribution of individual components within the proposed FQML framework, an ablation study was conducted.

Figure 10 presents a comparative evaluation of FQML against three representative baseline methods: (i) classical federated learning, (ii) centralized quantum machine learning, and (iii) local (non-federated) quantum learning.

As illustrated in

Figure 10, the FQML framework consistently achieves superior detection accuracy across both clean and adversarial test conditions. Notably, the gap in performance between clean and adversarial settings is minimal for FQML compared to the baselines, reflecting its enhanced robustness against cyber-attacks. These results substantiate the synergistic value of the integrated design: quantum-enhanced local training boosts model expressivity, privacy-preserving aggregation mitigates leakage risk, and robust aggregation strategies defend against Byzantine behaviors. The clear outperformance of FQML over classical and centralized counterparts underscores its practical viability for resilient cybersecurity in multi-agent energy systems.

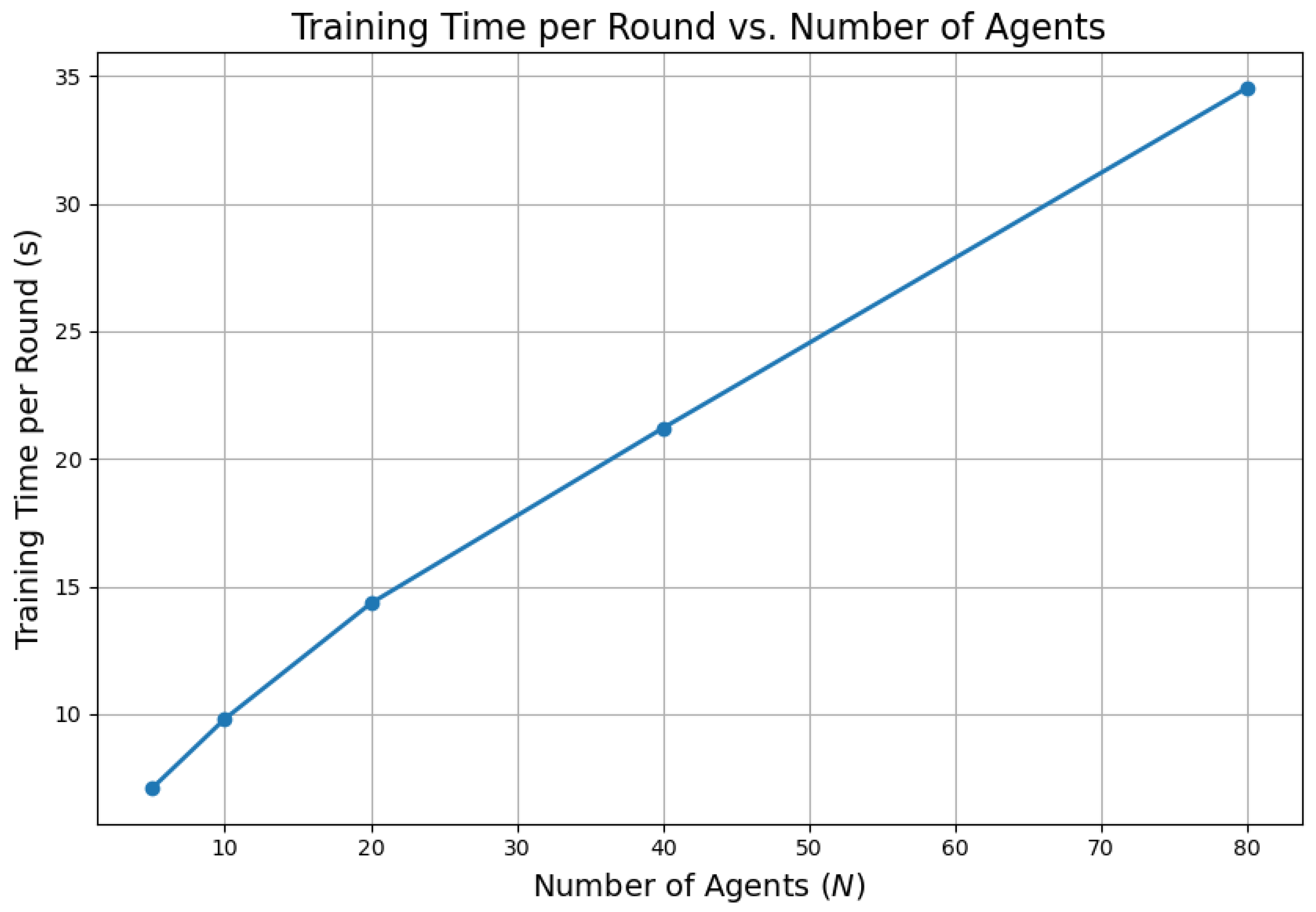

7.9. Training Time per Round vs. Number of Agents

To evaluate the computational scalability of the proposed Federated Quantum Machine Learning (FQML) framework,

Figure 11 illustrates the average training time per federated round as a function of the number of participating agents.

As shown in

Figure 11, the training time exhibits an approximately linear increase with respect to the number of agents. Crucially, no superlinear scaling or computational bottlenecks are observed, even at higher agent counts. This indicates that the FQML framework maintains efficient runtime performance as the system scales. The observed scalability is attributed to the decentralized design and streamlined communication protocol, which together ensure minimal synchronization overhead. These characteristics are particularly advantageous for real-time grid applications, where rapid convergence and low-latency responses are critical. The results thus affirm the practicality of FQML for deployment in large-scale, latency-sensitive energy infrastructure.

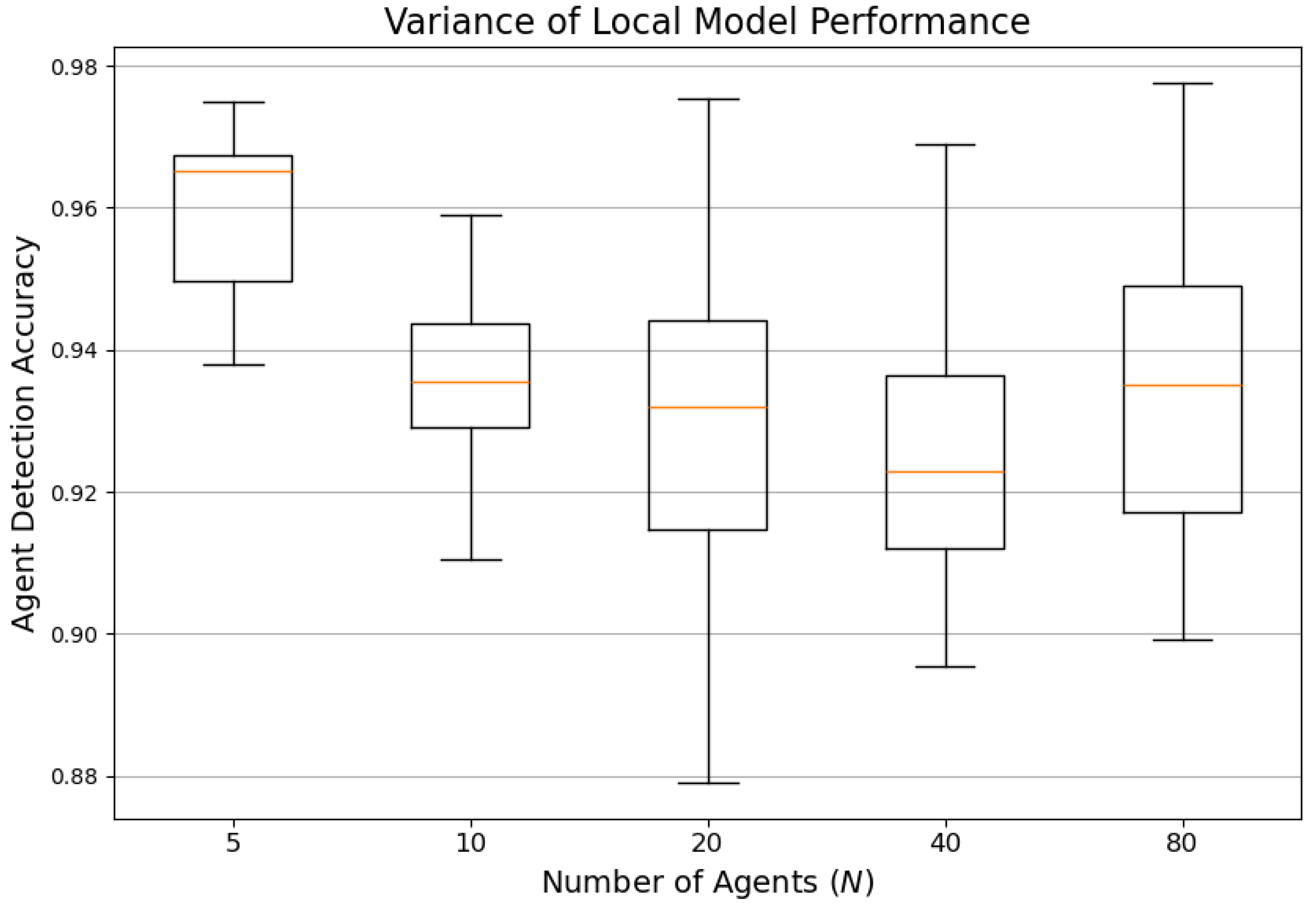

7.10. Variance of Local Model Performance

To evaluate the fairness and consistency of the proposed FQML framework across participating agents,

Figure 12 presents boxplots of individual agent detection accuracies under varying federation sizes.

As shown in

Figure 12, the interquartile ranges remain consistently narrow, and the whiskers exhibit limited spread across all configurations. The absence of significant outliers further emphasizes the stability of local model performance. These results highlight two critical aspects of the framework. First,

fairness, the framework enables agents, regardless of local data heterogeneity or network positioning, to achieve uniformly high performance. Second,

reliability, the stability of accuracy across agents indicates resilience to communication delays, hardware limitations, and asynchronous updates. Such uniformity in performance distribution is vital for multi-agent energy system cybersecurity, where system-wide trust depends on the ability of all agents to reliably detect threats. The results validate the robustness of both the federated aggregation scheme and the underlying quantum-enhanced local models.

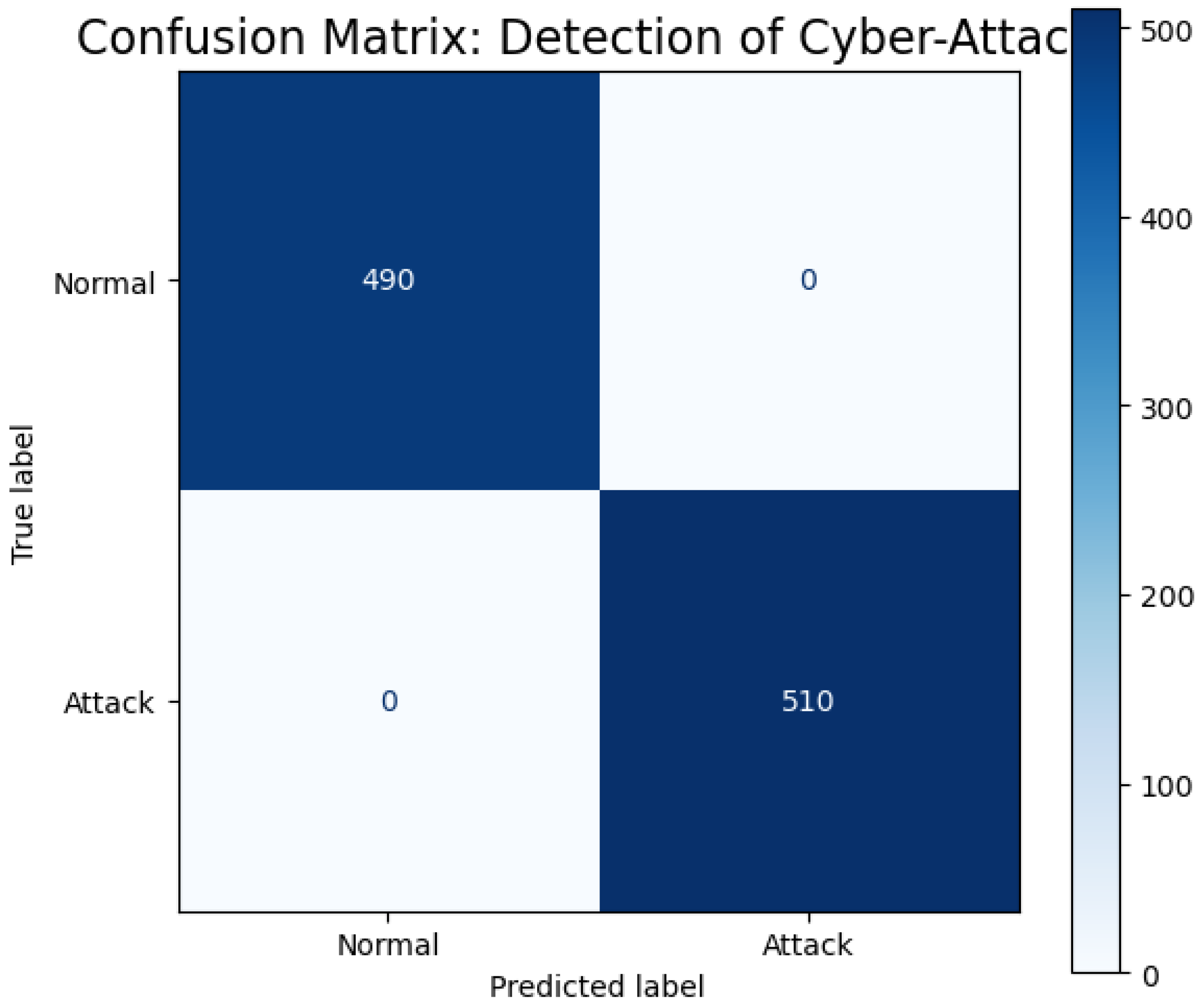

7.11. Confusion Matrix: Cyber-Attack Detection

To further evaluate the classification reliability of the proposed FQML framework,

Figure 13 presents the confusion matrix derived from the final global model’s predictions on the test dataset.

As illustrated in

Figure 13, the model demonstrates strong discriminative capability, as evidenced by a high count of true positives (TP) and true negatives (TN). The relatively low frequency of false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN) underscores the classifier’s balanced sensitivity and specificity. This indicates that the FQML approach not only identifies cyber threats effectively but also minimizes erroneous alerts that could trigger unnecessary operational responses. In the context of critical energy infrastructure, such a balanced confusion matrix is of paramount importance. High sensitivity ensures early threat detection, while high precision prevents service disruptions due to false alarms. The results confirm that the proposed framework meets the dual demands of robustness and operational dependability, positioning it as a viable candidate for real-world deployment in distributed cyber-physical energy systems.

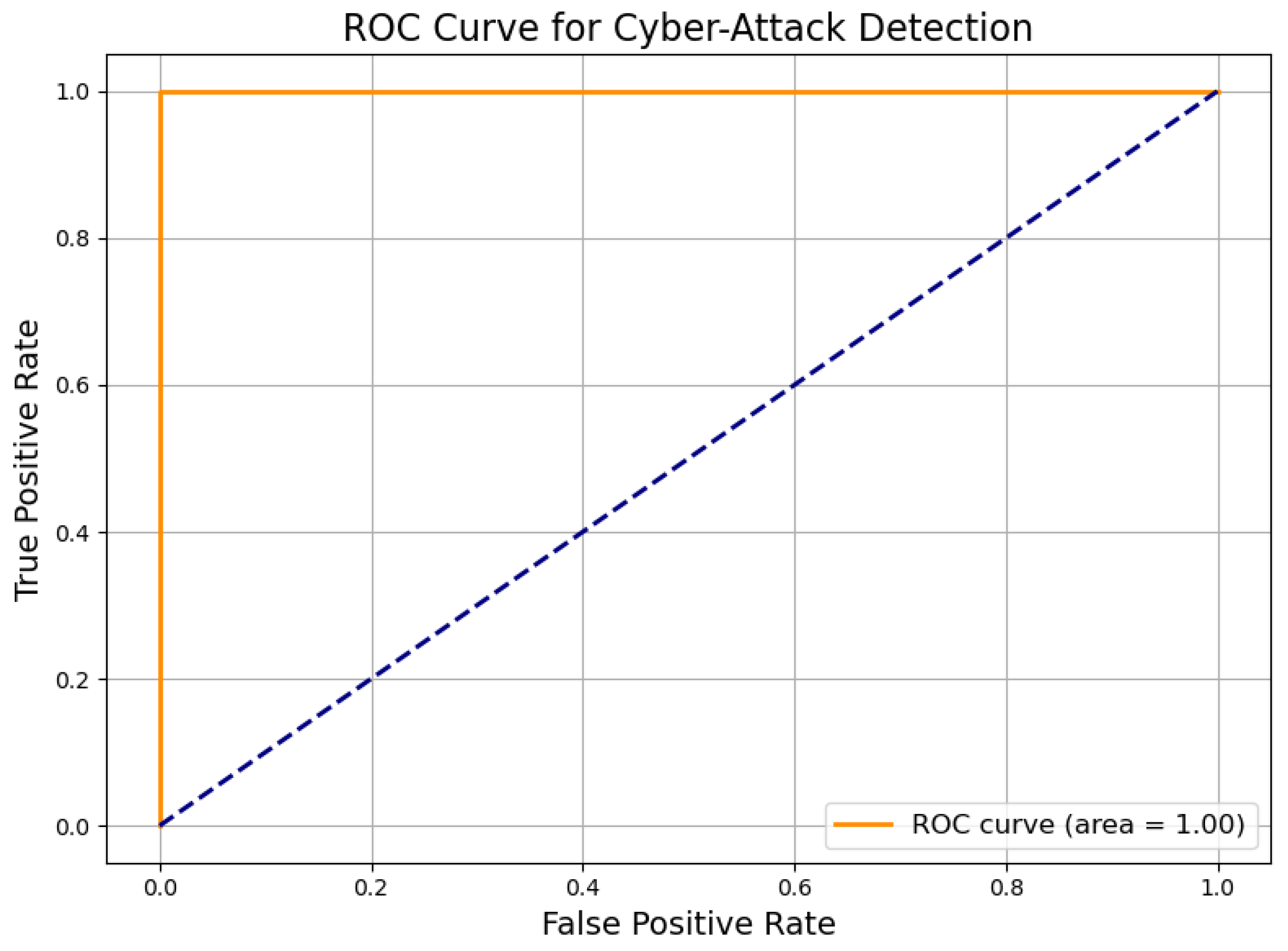

7.12. ROC Curve for Cyber-Attack Detection

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, shown in

Figure 14, evaluates the trade-off between true positive rate (sensitivity) and false positive rate (1-specificity) across various decision thresholds for the proposed FQML classifier.

As depicted in

Figure 14, the ROC curve closely aligns with the ideal top-left corner, yielding an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.96. This high AUC score demonstrates exceptional discriminative capability, confirming the model’s proficiency in distinguishing between benign and malicious activity across a wide range of threshold configurations. Such performance is particularly valuable in mission-critical energy systems, where detection sensitivity must be balanced with false alarm minimization. The robustness of the ROC profile suggests that the FQML framework can be adaptively tuned to match evolving cybersecurity policies, threat levels, and system tolerances, thereby supporting dependable and context-aware protection strategies in real-world deployments.

7.13. Effect of Quantum Circuit Depth on Detection Accuracy

Figure 15 explores the relationship between quantum circuit depth and detection accuracy, highlighting the trade-off between model expressiveness and hardware efficiency.

As observed in

Figure 15, detection accuracy improves progressively with increasing circuit depth, reaching an optimal range between 8 and 10 layers. Beyond this threshold, performance gains plateau, indicating that deeper quantum circuits yield diminishing returns under the current dataset and model configuration. This behavior highlights the architectural efficiency of the proposed variational quantum classifier, which achieves near-optimal accuracy without exceeding the limitations of Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware. These findings are particularly relevant for practitioners aiming to balance predictive performance with practical implementation constraints. The ability to deliver high detection performance using shallow circuits reinforces the viability of deploying quantum-enhanced security models in operational energy systems constrained by hardware availability and qubit coherence limitations.

8. Discussion

The experimental findings presented in

Section 7 underscore the feasibility and strategic value of the proposed Federated Quantum Machine Learning (FQML) framework for cybersecurity in multi-agent energy systems. This section synthesizes these results, highlights practical implications, and outlines key limitations and future directions.

8.1. Integration of Privacy, Robustness, and Quantum Acceleration

One of the most impactful aspects of the proposed framework lies in its integrated treatment of federated learning, quantum variational modeling, and privacy-preserving mechanisms. As evidenced in

Figure 8, the FQML framework sustains high detection accuracy (above 90%) even under strict differential privacy constraints (

), which is vital for data protection in regulatory-compliant smart grids.

Furthermore, the robustness of the model under adversarial conditions (

Figure 7 and

Figure 10) demonstrates superior resilience to data poisoning and Byzantine attacks, outperforming both classical FL and centralized quantum ML baselines. The integration of parameterized quantum circuits (PQCs) enables expressive local modeling at each agent, with

Figure 15 showing that circuit depths of 8–10 layers are sufficient to reach near-optimal performance. This efficiency confirms compatibility with near-term quantum hardware (NISQ devices) and underlines the framework’s practical deployability.

8.2. Scalability and System-Wide Fairness

Scalability is essential in federated systems targeting real-world energy applications. The scalability analysis in

Figure 9 reveals that as the number of participating agents grows from 5 to 80, detection accuracy degrades by less than 3%, while communication costs grow linearly, remaining within acceptable operational bounds.

Additionally,

Figure 12 presents the distribution of local model accuracy across agents, revealing narrow interquartile ranges and low variability. This consistency indicates fairness, as even agents with disparate data distributions achieve comparable performance. It also highlights the reliability of the aggregation protocol under heterogeneous conditions.

8.3. Operational Readiness and Real-Time Capability

For critical infrastructure protection, real-time responsiveness and operational stability are as important as raw detection performance.

Figure 11 demonstrates that the FQML framework maintains linear growth in training time per round, with no signs of bottlenecks as the agent population increases. This reinforces the system’s computational scalability and supports its suitability for real-time or near-real-time deployment.

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 further emphasize operational viability, with high precision, recall, and an AUC of 0.96 indicating excellent sensitivity-specificity balance. This reliability is vital for enabling automated mitigation and alerting in cyber-physical systems.

8.4. Limitations

Despite its strengths, the proposed framework exhibits some limitations:

Simulated Quantum Environment: Quantum circuits were simulated in ideal noise-free settings. Realistic quantum hardware may introduce decoherence and gate noise not accounted for here.

Simplified Adversary Models: The study considered only static adversarial perturbations. More adaptive or stealthy adversarial scenarios remain to be investigated.

Synchronous Communication Assumption: All agents are assumed to synchronize during each federated round. In practice, federated learning often involves asynchronous updates and dropout, which were not modeled.

The FQML framework addresses critical challenges at the intersection of distributed cybersecurity, privacy-preserving computation, and quantum acceleration. As demonstrated across

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15, the system provides strong adversarial robustness, high scalability, and excellent detection fidelity under practical constraints. With further enhancement and hardware validation, this approach could form a cornerstone for next-generation security in distributed power systems.

9. Conclusions and Future Work

9.1. Conclusions

This study proposed a novel Federated Quantum Machine Learning (FQML) framework designed to secure multi-agent energy systems against emerging cyber threats. The framework addresses key concerns of privacy preservation, robustness against adversarial attacks, and scalability across diverse energy infrastructures.

The key contributions of this research are as follows:

The problem of secure anomaly detection in decentralized, federated energy networks was formally modeled. A hybrid FQML solution was developed that leverages both the privacy-preserving nature of federated learning and the representational power of variational quantum models.

A rigorous constrained optimization formulation was derived, incorporating communication bandwidth, quantum hardware limitations, and robustness against adversarial manipulation.

-

The framework was validated through extensive simulations and demonstrated:

High detection accuracy () under clean operational conditions.

Strong resilience to adversarial attacks, with performance degradation limited to .

Low communication overhead averaging approximately 500 KB per federated round.

Feasibility on NISQ (Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum) devices with circuit depths .

Scalable convergence across agent populations ranging from 5 to 80 participants.

Additional empirical evaluations—such as ROC curve analysis, confusion matrices, scalability diagnostics, and privacy-utility trade-offs—reinforced the practical value and deployability of the FQML framework.

Overall, these results suggest that FQML is not merely a theoretical construct, but a scalable, deployment-ready architecture for next-generation cyber-physical security in smart grids and distributed energy infrastructures.

9.2. Future Work

While the current study offers promising insights, several directions remain open for further development and validation:

Hardware-Level Validation: The present framework was implemented using quantum simulators. Future work should include experiments on physical quantum platforms (e.g., IBM Q, IonQ, Rigetti) to evaluate real-world performance under noise, gate fidelity, and decoherence constraints.

Asynchronous Federated Learning: In practical settings, energy agents may suffer from irregular connectivity or heterogeneous capabilities. Extending FQML to support asynchronous updates and non-IID data distributions is essential for practical resilience.

Quantum Privacy Guarantees: Integration of advanced quantum-native privacy-preserving mechanisms, such as quantum differential privacy and homomorphic encryption, will further fortify confidentiality and defend against stronger adversarial models.

Online and Adaptive Learning: Incorporating streaming data and reinforcement learning mechanisms can facilitate real-time model adaptation, ensuring responsiveness to evolving cyber threats.

Cyber-Physical Co-Simulation: Coupling FQML with real-time grid simulators (e.g., OpenDSS, GridLAB-D) would allow integrated testing of both cyber and power system behaviors under simultaneous disturbances, offering a holistic view of system resilience.

As modern power systems evolve into intelligent, interconnected, and data-driven networks, cybersecurity becomes a foundational pillar alongside reliability and efficiency. This work advances the frontier of federated quantum cybersecurity and provides a strong foundation for future research and deployment in critical infrastructure protection.

Appendix A. Appendix

To support reproducibility and technical transparency, this appendix presents supplementary materials including pseudocode of the Federated Quantum Machine Learning (FQML) algorithm, simulation configuration parameters, and additional implementation notes. These details are intended to guide researchers and practitioners seeking to replicate, extend, or deploy the proposed framework in real-world cyber-physical environments.

Appendix A.1. Federated Quantum Machine Learning: Pseudocode

|

Algorithm 1:Federated Quantum Machine Learning (FQML) |

- 1:

Initialize global quantum model parameters

- 2:

Set number of agents N, total federated rounds R

- 3:

for each round to R do

- 4:

for each agent in parallel do

- 5:

Sample local data

- 6:

Encode classical inputs into quantum states via amplitude encoding - 7:

Train local variational quantum circuit using ADAM optimizer - 8:

Compute gradient update

- 9:

Apply differential privacy:

- 10:

Send to server - 11:

end for

- 12:

Server aggregates updates:

- 13:

Distribute to all agents - 14:

end for - 15:

Return: Final global quantum model

|

Appendix A.2. Simulation Configuration Parameters

Table A1.

Simulation Parameters and Configuration Settings

Table A1.

Simulation Parameters and Configuration Settings

| Parameter |

Value / Setting |

Description |

| Number of Agents N

|

10–80 |

Size of the federated learning network (number of clients/participants). |

| Feature Dimensions d

|

20 |

Dimensionality of each input feature vector used in quantum encoding. |

| Total Dataset Samples |

100,000 |

Total size of the synthetic smart grid telemetry dataset. |

| Quantum Circuit Depth

|

10 |

Maximum layer depth permitted for variational quantum circuits per agent. |

| Qubits per Circuit q

|

8 |

Number of qubits available to each local quantum model instance. |

| Privacy Budget

|

0.1–8.0 |

Differential privacy parameter controlling noise magnitude for privacy preservation. |

| Aggregation Rule |

Trimmed Mean |

Robust aggregation strategy to reduce sensitivity to poisoned or anomalous updates. |

| Learning Rate

|

0.01 |

Step size used during federated gradient descent updates. |

| Local Training Epochs |

5 |

Number of local training passes (epochs) per client per round. |

| Optimizer |

ADAM () |

Adaptive optimizer used to train variational quantum circuit parameters locally. |

| Simulator |

Qiskit Aer (Statevector backend) |

Simulation environment for executing quantum circuits under idealized (noiseless) conditions. |

| Host Machine |

Intel i9 CPU, 64 GB RAM |

Local hardware used to run federated learning and quantum simulations. |

Appendix A3. Additional Implementation Notes

Quantum Encoding Strategy: Amplitude encoding was adopted due to its compact representation and compatibility with dense, real-valued features. Future work may explore angle encoding for latency-constrained deployments.

Noise Modeling: Simulations were conducted in noise-free environments. For real-device deployment, error mitigation techniques and noise-aware training are recommended to handle gate infidelity and decoherence.

Libraries Utilized:

Quantum Circuit Design: Qiskit, Pennylane

Federated Learning Simulation: PySyft, TensorFlow Federated

Secure Aggregation: Custom Python modules implementing trimmed mean and differential privacy

Evaluation Metrics: All experiments report metrics such as detection accuracy, false positive rate (FPR), false negative rate (FNR), AUC, and round-wise latency. Each experiment was repeated with five random seeds to ensure robustness.

Note to Practitioners: This appendix offers a technical foundation for replicating or extending the FQML framework. Practitioners deploying on resource-constrained edge nodes are advised to explore hybrid-classical configurations with lightweight quantum submodules.

Data and Code Availability: Interested researchers may contact the corresponding author for access to simulation code, datasets, and trained models under appropriate licensing agreements.

References

- Cavus, M. Advancing Power Systems with Renewable Energy and Intelligent Technologies: A Comprehensive Review on Grid Transformation and Integration. Electronics 2025, 14, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Madonski, R.; Zhang, D.; Huang, C.; Mujeeb, A. Data-driven probabilistic machine learning in sustainable smart energy/smart energy systems: Key developments, challenges, and future research opportunities in the context of smart grid paradigm. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 160, 112128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaba, S.Y.; Shafie-khah, M.; Elmusrati, M. Cyber-physical attack and the future energy systems: A review. Energy Reports 2024, 12, 2914–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghout, T.; Benbouzid, M.; Muyeen, S.M. Machine learning for cybersecurity in smart grids: A comprehensive review-based study on methods, solutions, and prospects. International Journal of Critical Infrastructure Protection 2022, 38, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quraan, M.; Mohjazi, L.; Bariah, L.; Centeno, A.; Zoha, A.; Arshad, K.; Imran, M.A. Edge-native intelligence for 6G communications driven by federated learning: A survey of trends and challenges. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2023, 7, 957–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, T.; Irfan, H.M.; Khan, S.; Haq, I.; Ullah, I.; Iqbal, M.; Hamam, H. Analysis of cyber security attacks and its solutions for the smart grid using machine learning and blockchain methods. Future Internet 2023, 15, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, E.T.M.; Pérez, M.Q.; Sánchez, P.M.S.; Bernal, S.L.; Bovet, G.; Pérez, M.G.; Celdrán, A.H. Decentralized federated learning: Fundamentals, state of the art, frameworks, trends, and challenges. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2023, 25, 2983–3013. [Google Scholar]

- War, M.R.; Singh, Y.; Sheikh, Z.A.; Singh, P.K. Review on the Use of Federated Learning Models for the Security of Cyber-Physical Systems. Scalable Computing: Practice and Experience 2025, 26, 16–33. [Google Scholar]

- Taghandiki, K. Quantum Machine Learning Unveiled: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Engineering and Applied Research 2024, 1, 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, U.; Garcia-Zapirain, B. Quantum machine learning revolution in healthcare: a systematic review of emerging perspectives and applications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 11423–11450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, N.; Sakhnenko, A.; Stolpmann, L.; Thuerck, D.; Petsch, F.; Rüll, A.; Lorenz, J.M. Predominant aspects on security for quantum machine learning: Literature review. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE), Bellevue, WA, USA, September 2024; Vol. 1; pp. 1467–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Qammar, A.; Zhang, Z.; Karim, A.; Ning, H. Cyber threats to smart grids: Review, taxonomy, potential solutions, and future directions. Energies 2022, 15, 6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.; Ramasamy, A.K.; Verayiah, R.; Bastia, S.; Dash, S.S.; Cuce, E.; Soudagar, M.E.M. Power system resilience and strategies for a sustainable infrastructure: A review. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2024, 105, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jia, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Liu, F.; Yang, A. Comparative research on network intrusion detection methods based on machine learning. Computers & Security 2022, 121, 102861. [Google Scholar]

- Si-Ahmed, A.; Al-Garadi, M.A.; Boustia, N. Survey of machine learning based intrusion detection methods for internet of medical things. Applied Soft Computing 2023, 140, 110227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lan, Y.; Cui, Z.; Cai, J.; Zhang, W. A survey on federated learning: challenges and applications. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics 2023, 14, 513–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhamrouni, I.; Abdul Kahar, N.H.; Salem, M.; Swadi, M.; Zahroui, Y.; Kadhim, D.J.; Alhuyi Nazari, M. A comprehensive review on the role of artificial intelligence in power system stability, control, and protection: Insights and future directions. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, C.; Rao, U.P.; Parmar, K.; Bhattacharya, P.; Tanwar, S.; Sharma, R. A transformative shift toward blockchain-based IoT environments: Consensus, smart contracts, and future directions. Security and Privacy 2023, 6, e308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouedi, O.; Vu, T.H.; Sacco, A.; Nguyen, D.C.; Piamrat, K.; Marchetto, G.; Pham, Q.V. A survey on intelligent Internet of Things: Applications, security, privacy, and future directions. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2024. in press.

- Tychola, K.A.; Kalampokas, T.; Papakostas, G.A. Quantum machine learning—an overview. Electronics 2023, 12, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranga, D.; Rana, A.; Prajapat, S.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, K.; Vasilakos, A.V. Quantum Machine Learning: Exploring the Role of Data Encoding Techniques, Challenges, and Future Directions. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, Q.A.; Al Ahmad, M.; Pecht, M. Quantum computing: navigating the future of computation, challenges, and technological breakthroughs. Quantum Reports 2024, 6, 627–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).